ABSTRACT

Politics was long overlooked in analyses of architecture. International politics still is. Yet one of the sub-fields of International Relations seemingly best equipped to address this oversight, ‘International Political Sociology’ (IPS), is at a crossroads with leading scholars bemoaning the dominance of Sociology over the political and the international. They concur on the need revive the political, but some advocate abandoning the international. Instead, I argue that IPS scholars should embrace the international and suggest a particular way to do so via Rosenberg’s concept of Multiplicity. This transforms the international from the object of analysis into an analytical and heuristic lens through which to examine the constitutive effects on, (e.g.) architecture, of (international) societal co-existence, interaction, combination, difference, and dialectical change. Using examples from the late Habsburg period to the present, I sketch an international politics of ‘Czech’ architecture and show the value of ‘the international’ in and beyond IPS.

We are used to discussing architecture in terms of its relationship to art history, or as a reflection of technological change, or as an expression of social anthropology. We know how to categorize buildings by the shapes of their windows, or the decorative detail of their column capitals. We understand them as the products of available materials and skills. What we are not so comfortable with is coming to grips with the wider political dimensions of a building, why they exist in fact, rather than how. It’s an omission that is surprising, given the closeness of the relationship between architecture and power.

I. Understanding architecture, reviving the international

Deyan Sudjic’s book, The Edifice Complex (Citation2006), makes an interesting and insightful case for engaging with the politics of architecture. As a former editor of Domus, architecture critic of The Observer, director of London’s Design Museum and author of numerous books on architecture, Sudjic was well placed to address the omission he identifies and he does so via discussion of the politics of a wide range of state, church, commercial and private architecture. Generally, however, he focuses on the domestic actions and political concerns of state actors or of non-state actors acting within particular national contexts. The international political dimensions of the buildings he discusses remain obscure, latent or somewhat haphazardly picked up, rather than systematically explored, analyzed, and interpreted.

Within the discipline of International Relations, the sub-field of ‘International Political Sociology’ (IPS) has perhaps done most to engage issues related to architecture with scholars branching out in directions including: aesthetic international relations (e.g. Bleiker, Citation2009) and visual world/global politics (e.g. Bleiker, Citation2018; Hansen, Citation2015); materialities (e.g. Aradau, Citation2013), new materialism and related explorations of Making Things International (Salter, Citation2015); as well as the ‘practice turn’ (e.g. Adler-Nissen, Citation2016) and the development of ‘International Practice Theory’ (e.g. Bueger & Gadinger, Citation2014). IPS has actively imported theories, concepts, and approaches from (e.g.) Sociology, Geography, Anthropology, Law, and Science and Technology Studies. However, like other sub-fields of IR, it has been less successful in exporting ideas or analyses to those other disciplines (Brown, Citation2013; Rosenberg, Citation2016; Waever, Citation2007).

Yet, if Sudjic or other architectural thinkers were to turn to IPS for inspiration to better understand the international politics of architecture, they would find the sub-field at a crossroads. Debbie Lisle, Editor-in-Chief of the journal International Political Sociology, has acknowledged that ‘interdisciplinarity’ has been ‘vital’ to the ‘whole endeavour’, but lamented ‘a growing assumption that IPS has become simply a “political sociology of the international”’ (Lisle, Citation2016, p. 418). Lisle warns that an interdisciplinarity which ‘leaves our intellectual foundations and knowledge claims intact’, has allowed ‘Sociology to dominate the project’ at the expense of the international and the political (Lisle, Citation2016, p. 420). Lisle calls for IPS scholars to address this imbalance, but mainly by embracing a normatively driven, transformative notion of the political, in which scholars should retain hope and keep struggling for (limited) change in the face of adversity.

Similarly, Austin (Citation2017) – who draws on Lisle – argues that critical IR (including IPS) scholars’ political impact in the world has been blunted by, inter alia, tendencies to focus on: ‘domination’ as a form of oppressive and irrecoverable politics; or by engaging in ‘apolitical’ or ‘anti-normative’ work on (e.g.) practices. Instead, he urges IPS scholars (and others) to invest their work with a ‘distinctly political taste’ and explicitly seek to make ‘critical impact in the world’ in order to change it for the better. For both Lisle and Austin, addressing the shortcomings of IPS and critical IR more widely rest on reviving the political rather than the international. Nabers and Stengel (Citation2019) are even more explicit in this regard: they urge IPS to develop a broad yet explicitly conceptualized notion of the political, but enthusiastically endorse calls by (e.g.) Bartelsen (Citation2018, p. 34) to ‘move beyond “the international”’ echoing long-standing calls to move toward the study of ‘Global Politics’ rather than ‘International Relations’ (Edkins & Zehfuss, Citation2009).

In this article, I present a different view and suggest a different way forward for IPS. I argue that ‘moving beyond’ – in practice, abandoning – ‘the international’ would be premature. As Justin Rosenberg has compellingly argued, we IR scholars have yet to explore the true potential of the international as IR’s ‘deepest ontological premise’ (Citation2016, p. 135). He argues that societal multiplicity is the fact ‘general to the social world’ that our discipline implicitly takes as its starting point, which other disciplines do not, and thus gives us a different view, which allows us to analyse and interpret social and political phenomena (such as architecture) differently than, e.g. (art) historians, architectural theorists, sociologists or anthropologists (Rosenberg, Citation2016, p. 132). Rosenberg also shows that IR (including IPS) scholars have yet to truly ‘take possession of’ this unique perspective. I argue that doing so – through multiplicity – would provide an alternative to abandoning the international or merely taking ‘established modes of enquiry from Sociology and Political Sociology and apply[ing] these “upward” to the realm of the international’, which Lisle explicitly and rightly cautions against (Citation2016, p. 420).

Lisle (Citation2016) and Austin (Citation2018) both note the difficulties of ‘zooming’ between the micro-level of (e.g.) aesthetics, materialities or practices and the macro-level of international relations, global politics or ‘the world-political’ (Austin, Citation2018). Here, (Societal) Multiplicity offers a new way forward. Multiplicity situates the international as the analytical and heuristic lens through which to look at and interpret (e.g.) aesthetics, materialities and practices, rather than the object which can be explained or interpreted by them (e.g. Hansen, Citation2015). Rosenberg argues, in effect, that IR (including IPS) scholars have been looking down the wrong end of the telescope. By turning the telescope around, we can leverage the power of (inter alia) IPS and its expanded ontologies, epistemologies, and methodologies, as well as its normative concerns, within as well as beyond IR. Multiplicity fulfils Lisle’s (Citation2016, p. 418) criterion in that it does not leave the ‘intellectual foundations’ or ‘knowledge claims’ of IR ‘intact’ – but nor does it throw the baby out with the bathwater by abandoning the international.

In this article, I explore the potential of multiplicity as a way of retaining and reviving the international in IPS and illustrate the value of doing so by showing the analytical and interpretive purchase that it provides in understanding architecture in the Czech lands. I thus also show what IPS/IR can add to extant analyses (from other disciplines) of the politics of such architecture. I do this with particular reference to the five ‘consequences’ of multiplicity identified by Rosenberg: (I) co-existence, (II) difference, (III) interaction, (IV) combination, and (V) dialectical change. First, however, the way I do so and why I do so in relation to Czech architecture merits a couple of clarifications and explanations.

Following Rosenberg’s reasoning, each of these ‘consequences’ should take place concurrently rather than merely consecutively, albeit unevenly. I illustrate each one with reference to a particular period of Czech history, which is not to suggest that the other consequences were not significant at the time. Rather this is an analytical separation to draw out the particularities of each consequence – and its value for understanding the international politics of the architectural examples sketched in each instance.Footnote1 Again following Rosenberg, multiplicity as a universal fact of the social world, is relevant to practically everything. As ‘the international’ is a highly significant form of multiplicity, we could therefore ask ‘what is the international?’ or ‘what are the international politics?’ of practically anything.

Yet, my selection of the ‘case’ of Czech architecture is not merely an arbitrary terrain on which to demonstrate multiplicity’s analytical and interpretive value. Architecture combines two key concerns of IPS – visuality and materiality – and the analysis and interpretation presented here are explicitly intended to show the value to IPS of retaining the international (as a form of multiplicity) alongside and on the same footing as the political and the sociological. The choice of Czech architecture is also deliberate, because it has been written about in depth from historical, sociological, and (more recently) political perspectives, which makes it a hard case for an IR or IPS to add something new and meaningful. This is where the systematic use of the international, conceptualized through the consequences of multiplicity comes in: it transforms what is a fleeting or latent interpretive presence in, e.g. the award-winning work of the historical sociologist Derek Sayer (Citation2000, Citation2013), into a systematic analytical and heuristic device. Thus, I claim, IR/IPS scholars can excavate, construct or connect additional layers of meaning and understanding that complement and extend existing work. If we take Sayer’s other claims about the different view of major twentieth-century phenomena that we get by looking on and from Prague, rather than (e.g.) Paris or New York, then providing a more systematic international political analysis takes on still further worth.

In the following sections, I sketch examples from Czech history – ranging from the late-Habsburg time to the present – which illustrate how Rosenberg’s five ‘consequences’ of multiplicity: (I) co-existence, (II) interaction, (III) combination, (IV) difference, and (V) dialectical change – shed new, international political light on architecture. Doing so shows the value of the international to IPS and the value that IR (through the prism of multiplicity rather than in the prison of political science) can add to our understanding of phenomena such as architecture, and thus complement analyses provided by other disciplines.

II. Co-Existence: forms of recognition

Rosenberg identifies multiplicity – the concurrent existence of multiple societies – as a fundamental condition of the social world. It follows that Czech society (like all societies) has always co-existed with other societies. However, the forms – including the political forms – in which it has done so have changed over time. One of the most significant changes to the forms of Czech societal co-existence concerns statehood, the lack of it and the quest for it in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Sayer, Citation2019). This section illustrates how the international, inter-societal politics of the struggle for the recognition of nationhood shaped key ‘Czech’ buildings, which then provided a useful backdrop to claims for statehood.

Like many nineteenth Century nationalist movements in Europe, the ‘Czech National Revival’ or National Re-birth as Derek Sayer more forcefully renders it (Sayer, Citation2000, pp. 54–81) sought recognition for a community imagined as a nation, which subsequently sought independent statehood (Anderson, Citation1991; Sayer, Citation2019). It ran a familiar gamut of linguistic invention and codification, historical re-interpretation and myth-making, political mobilization and demands for representation, educational reform, economic re-distribution, and re-structuring, as well as self-conscious cultural stridency and the institutionalization of ‘national culture’. This institutionalization also necessitated materialization in the form of buildings – theatres to (quite literally) provide the stage for performances in the national language and museums for the collection, curation – and creation – of national history and heritage ( and ).

Figure 1. Art History Museum, Vienna (1891). Manfred Werner – used under, CC BY-SA 3.0, cropped, wiki commons.

Figure 2. National |Museum, Prague (1891). Image: Jiří Lízler, Národní Muzeum, used with permission. www.nm.cz

It is no surprise, therefore, to find that the National Theatre (NT) and National Museum (NM) occupy prime spots in Prague – they are noted in practically every guidebook to the city as key sites (at the river end of the ‘National Avenue’ and the top of the Wenceslas Square, respectively) and are practically unavoidable for any tourist wandering the city centre. Given that both buildings were intended to showcase the specificity and uniqueness of Czech national culture, it is more surprising that they look so similar to comparable buildings in Vienna – the imperial capital and one cradle of the society from which Czechs were seeking to overtly distinguish themselves. This is where understanding the international politics of Czech co-existence, and its changing forms, is useful in understanding why the NT (1881; 1883) and NM (1891) look so similar to Vienna’s State Opera (1869) and twin Museums of Natural History (1889) and Art History (1891) ( and ).

Figure 3. National Theatre, Prague (1883), Image: © A.Savin, WikiCommons. Used in accordance with terms of use.

Figure 4. State Opera, Vienna (1869). Image: Carlos Delgado – used under CC-BY-SA, 3.0, wiki commons.

While clearly not identical, each of the buildings is made in a variation of the ‘neo-renaissance’ style and they bear strong familial resemblances. Given the time of their respective construction their similarities could, at a glance, be put down to the influence of passing fad or fashion – although attending to particular fashions is not without significance and attests to both sensibility (knowing what’s what) and capability (to manifest it materially). Moreover, this was a time of great eclecticism in architecture, of competing historical styles with the neo-gothic and other forms very much en vogue, certainly by the latter buildings’ completion dates (as the competition for the design of the CNM testifies).Footnote2 So why were such similar styles chosen for the NT and NM as for the buildings in Vienna, a place from which Czechs were, ostensibly, trying to distance themselves? To answer this question, we can look deeper into the history of the buildings and how the political relations between the emergent, self-consciously Czech society and Imperial Austrian society gives context to their forms.

Both the Czech ‘national’ theatre and national museum grew from the ‘land patriotism’ (Sayer, Citation2000, p. 57) of Bohemian nobles, which imagined no ‘Czech’ community and did not seek to usurp Vienna’s rule (Sayer, Citation2000, pp. 53–62). However, Sayer shows compellingly that both projects were later ‘hijacked’ by the national revivalists. This was particularly evident in the unfaithful translation of the original German ‘mission statement’ of the museum into Czech, in which it took on a quite different purpose (Sayer, Citation2000, p. 62). The theatre and especially the museum with its connections to Czech natural and human sciences, were intended to act as a ‘tangible presence of the truth’ of the existence of the Czech nation – a ‘mirror of identity’ in Sayer’s terms (Citation2000, p. 82). The materialization of the theatre and the museum is testament to the desire for a ‘Czech-ness’ set in stone (Therborn, Citation2002). However, their similarity to the buildings in Vienna makes visible the truth of Czech existence as co-existence in a particular international-political as well as inter-societal and socio-political context.

Building the NT and NM played a significant role in gaining recognition for Czechs as a socio-culturally distinct national community: ‘internally’ – self-recognition in the ‘mirror of identity’ – from Czech society and ‘externally’ from Vienna. Building the theatre and the museum in styles similar to those of the Viennese State Opera and Historical Museums should not be seen as merely the metropole setting the fashionable tone, which was then followed in the provinces. Rather, the style of the buildings reflects the choice of ‘appropriate’ architectural forms that would help gain recognition without overtly provoking the imperium but while subtly subverting it by situating ‘Czech’ traditions in the wider European, rather than Austro-Hungarian context (de Meyer, Citation2006, pp. 87–88). The recent grand re-opening of the museum (2018) explicitly presented the debate over different, competing styles that were originally proposed for the museum. The choice to echo the architectural forms of comparable buildings from Vienna was deliberate and followed in the wake of considerable controversy over the design of Viennese museums themselves. The initial plans for these museums had produced ‘unsatisfactory’ results, leading to Gottfried Semper (famed for his Dresden Opera House) being brought in to advise on the ‘proper form’ for such institutions.

This proper form was duly (and locally) chosen for the Prague museum too, thus helping gain external recognition for the museum – and the theatre – as being Czech but also signalling the existence of a national culture capable of expressing itself in such an appropriate way. Internally, the choice of the neo-renaissance style made the buildings recognizable to the wider, Czech society as buildings suitable for a national capital (Therborn, Citation2002). However, it also echoed Italian traditions which were associated with a previous flourishing of architecture in the Czech lands but not with imperial, German or Austrian domination that could be more easily associated with gothic architecture (de Meyer, Citation2006, pp. 87–88; Koerner, Citation2009, p. 128). This fits with the international, inter-societal drive for national recognition, combined with a subtle domestic politics of distinction.

Changes in this politics of societal co-existence – as Czech national claims became more strident and less concerned about provoking negative reactions in Vienna – can also be seen in the architecture and décor of major public buildings. The Prague Municipal House (1903–1912), for example extravagantly outdoes Viennese art nouveau buildings in scale and ups the nationalist ante with its paintings and murals on ‘Czech’ themes. Little was pre-ordained or long-planned in the move toward Czech statehood and no linear causality can be drawn to this from the existence of the museum and the theatre. Nonetheless, having such ‘national’ buildings that were clearly recognizable as such and served as key sites of internal and external (inter-subjective) identity (re-)production certainly did no harm to the cause. In contrast to the claims of (e.g.) Ukrainian nationalists, Czech statehood was recognized by the victorious powers of World War One, after the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire. This came, however in the form of the multi-ethnic state of Czechoslovakia, which comprised not only Czechs and Slovaks, but Germans, Jews, Rusyns, and several other ethnicities (Sayer, Citation2000, p. 168).

III. Interaction: the international in a national golden age

Moving to the next consequence of multiplicity, in this section I look at how the social politics of international interaction shaped ‘Czech’ architecture in the interwar period. While this period was famously seen as a time of crisis by observers elsewhere (Carr, Citation2016), domestically it is still widely celebrated as the Czech ‘golden age’ (see e.g. Eberle, Citation2018; Holubec, Citation2014; Koeltzsch & Konrád, Citation2016). It shone especially brightly in the art, architecture, and design of the time. In this section, I show how the cultural flourishing of the Czech national golden age may have been particular but it was entangled with international modernism and dependent upon interaction between Czech society and societies elsewhere (Hubatová-Vacková & Pravdová, Citation2018; Sayer, Citation2000, Citation2013).

That Bohemia had been the most industrialized part of the Austro-Hungarian empire helped the first Czech(oslovak) republic to thrive economically after independence; and politically, President Thomas Garrigue Masaryk and Foreign Minister Edvard Benes sought to actively embed the new state in the emerging international society (Orzoff, Citation2009). They were keen to do so in order to seize political and economic, but also socio-cultural, opportunities as well as to guard against threats both from hostile powers and the domestic dangers of a what they saw as parochial ‘superstitious bigotry’ – nationalism (Orzoff, Citation2009, p. 83). Masaryk and Benes therefore strove to present Czechoslovakia internationally as a beacon of progress and modernity as well as a bastion of democracy. By seeking to maximize international political, economic, and cultural interaction they sought to fashion a state and a society to be admired, related to and engaged with, but also to be protected by others if it were threatened. As Andrea Orzoff has shown (Citation2009) this strategy of interaction was vigorously pursued through diplomacy and the state-driven propaganda activities of the Orbis publishing house. However, as well as being a top-down, state-led effort it was also entangled in wider societal trends and official activities were complemented and sustained by a cultural, including architectural, flourishing that was reinforced by the economic boom.

This embrace of ‘the new’ and of ‘the international’ was most apparent – and publicly influential – in modernist architecture. Around Prague and across the republic, actors in Czech society both imported and made their own developments of what, famously, became known as ‘The International Style’Footnote3 (Hitchcock & Johnson, Citation1997). This was most celebratedly the case in Prague’s ‘Baba’ development (1927) and in the luxury villas for the Müller family in Prague (1929) and the Tugendhat family in Brno (1930). The multi-ethnic character of the First Republic was apparent in the commissioning of German and Austrian architects, often by German and Jewish families (as in the case of the Tugendhat villa) to build such pieces in the Czech lands. However, international style modernism and its preferred local variant – Functionalism – also soon displaced the so-called national style (a type of decorative geometrism as seen on, e.g. the Legions Bank in Prague [1921–1923]), as the dominant form of large-scale public building ().

Figure 5. Tugendhat Villa, Brno (1930). Image: David Židlicky, from media gallery tugendhat.eu, used with permission.

Key examples of international style modernism and functionalism in major buildings in Prague include the Trade Fair Palace (1928), the Pension Institute (1930), the church of St Vaclav (1929), and the Hussite Cathedral (1930) in the Vršovice and Vinohrady districts – the latter two testifying the pervasiveness, across different spheres of life, of modernism in the First Republic. As Andrew Herscher notes, the Czech architectural avant-garde cannot be seen as merely ‘a local variation on a universalising “Western modernism” but as a complication of the latter … that may render it knowable in a new way’ – i.e. it spoke back to and influenced international modernism as well as being influenced by it (Citation2004, p. 198) Outside of the capital, Zlin in South Moravia became famous as the ‘company town’ of the Baťa shoe company, one of the biggest and most internationally active of all Czechoslovak firms. Zlin even impressed Le Corbusier, then the leading architect in the world and, notoriously, no easy touch who described it as a ‘shiny phenomenon’. Corbusier also engaged in depth with leading architects and cultural figures in Prague testifying to the international esteem in which Czech modernism was held at the time (Sayer, Citation2013, pp. 144–147). Later, Kenneth Frampton, a leading architecture critic and scholar described it as ‘a modernity worthy of the name’ (Citation1993).

Interwar Modernism in Czechoslovakia was not, however, exclusively for the interests of commerce or the pleasure of the wealthy. The architectural theorist and artist Karel Teige – an interlocutor of Corbusier as well as the surrealist Andre Breton – described the Muller and Tugendhat villas as ‘the pinnacle of modern snobbery’ and instead proposed a ‘minimum dwelling’ that would harness modernism for the needs of the masses (Sayer, Citation2013, p. 149; Teige, Citation2002). Internationally influenced Socialist and Marxist interpretations of Modernism also abounded in the First Republic – in conflict, but also discussion, with more liberal and capitalist variants. These debates echoed conversations at the Bauhaus in Germany where Teige lectured and reflect the intense interaction and exchange between Czech modernists and their counterparts at that crucible of international modernism (Svobodová, Citation2017). What these various modernisms in the Czech lands shared was the drive to overcome regressive, parochial aspects of ‘national’ culture – and life – by embracing the international and pushing their own society to its core (Sayer, Citation2013, p. 204). As one notable Czech magazine, published by the influential Devetsil group, proclaimed – quoting French painter Maurice Vlaminck – ‘Stupidity is national. Intelligence is international’ (Sayer, Citation2013, p. 208).

The key protagonists of Czech modernism practised what they preached, interacting with – and influencing – leading figures and currents of international thought and practice at the time (Sayer, Citation2013). Moreover, the impressive list of world-class modernist buildings mentioned above is only a fraction of the stock of such pieces in Czechia. Interacting with, embracing and making international modernism their own, fundamentally re-shaped large swathes of the country as Czechs sought to architecturally demonstrate that they belonged at the top, progressive table of international society. Often, however, these were top-down, elite visions which were popular, although not universally, and were often hostile to perceived notions of ‘Czech-ness’ (Sayer, Citation2000, pp. 218, 221, Citation2013, pp. 177, 192–195).

Despite the international ambitions and interactive success of the Czech modernists, the national was key when the First Republic’s downfall came abruptly, via the British and French appeasement of Hitler, which made Munich the most infamous city in the history of Czech interaction with the world. However, the Republic’s vibrant interwar modernisms, including in architecture, amply demonstrate how (national) societies are materially shaped by their interaction with other national societies and with the international society. This interaction cut both ways: Czech modernists enhanced their society’s influence abroad as well their own influence at home by providing conduits for importing modernisms that they subsequently helped to shape. They also interacted internationally as, inter alia, communists, socialists, and surrealists, but ultimately, such political-cultural embedding in the international society was overwhelmed by other currents of international politics of the time, which amounted to a victory of machtpolitik and great power horse trading over ‘idealist’ interconnection through interaction. Nonetheless, interaction produced particular combinations of the local and the international, manifest in the visual-materiality of the architecture of the time. Other manifestations of combination, from later periods are discussed below.

IV. Combination: East or West, modernism’s best

Milan Kundera’s influential (Citation1984) essay about Czechoslovakia, ‘The Kidnapped West’ has much to answer for (e.g. Eberle, Citation2018). Of many problematic claims, his assertion that the communist era was ‘post-cultural’ implies that there was no cultural production, including architectural production in this period that was of high or international quality (see also Kucera, Citation2018). Lucie Ševčikova of the Arts Institute in Prague echoes this judgement and emphasizes that it was a break from the recent Czech past: ‘The communist period (1948–1989), however, severed this line of architectural continuity and architecture is still working to make up for lost ground today’ (Ševčíková, Citationn.d.). Kundera frames the East–West divide, which he sees as responsible along with communist rule for this post-cultural detachment, as near total. This supposed ‘rupture’ would make it unlikely that the influence of Western architecture could be seen in communist era Czechoslovakia, and even less likely that Czechoslovak architecture and design would have any influence in the West (Kohout, Šlapeta, & Templ, Citation2008).

However, as I show in this section, significant parts of the culture and architecture of the communist period in Czechoslovakia warrants (and has belatedly received) recognition domestically and internationally. Moreover, it is only by looking at how Czechoslovak society continued to co-exist in combination with other societies, including Western societies, as well as with its culturally significant past during the Cold War, that the particular forms of these architectures and their influence in the wider world can be understood. I first look at the concrete housing estates and ‘panel’ buildings – supposedly so emblematic of the communist regime – to show that rather than being the product of spatio-temporal isolation, they actually combined local innovations (predating communism) with international trends that were also apparent in non-communist regimes – albeit in the particular circumstances of Czechoslovak society. I then examine the significance of the 1958 ‘Expo’ in Brussels, specifically the success and lasting impact of the Czechoslovak pavilion. Both examples show how combinations of ‘here’ and ‘there’, as well as ‘now’ and ‘then’ affected the inner constitution of Czech society – and acted back on the international – demonstrating the importance of combination for architecture and giving the lie to claims of architectural inferiority due to supposed isolation.

The postwar electionFootnote4 of the Communist party to the Czechoslovak government, and the subsequent centralization of planning and construction, combined with particular local historical conditions to drastically re-shape the country’s towns and cities. Seeking to upgrade housing stock and to hasten urbanization, the Czechoslovak central construction agency embarked on a series of monumental housing schemes. The construction of these housing projects would last from the 1950s to the 1980s and take in numerous decorative styles and planning doctrines (Skrivánková, Svácha, & Lehkozivová, Citation2017). By the time of the Velvet Revolution (in a pattern that endures to the present) more than one-quarter of the population of Czechia and nearly half of Prague lived in these developments. However unfairly, the concrete estates and panel buildings thus came, for many observers (domestic and international), to materially symbolize much that was wrong with the communist era: grey (or greyish), monotonous, poorly built, unimaginative ‘Eastern’ bloc(k)s which ‘considerably impaired the image of the city’(Kohout et al., Citation2008, pp. 7–8, Kucera, Citation2018; Skrivánková et al., Citation2017, p. 9; Svacha, Citation2000; Zarecor, Citation2012).

However, as more recent research has shown, the technology which enabled this massive construction programme was not a communist imposition. The use of pre-fabricated concrete panels had been developed and used in the interwar period by the Baťa company’s engineering department in Zlin and this work continued after it was incorporated into the communist central planning agency, Stavoprojekt (Zarecor, Citation2011, pp. 23–24, 34, 89–95, 225).

There had been intensive interaction between Czech and French architects and cultural as well as commercial figures during the First Republic, and the similarities between the Czech ‘G-Building’ approach and ‘systems building’ in France (and elsewhere) were apparent in the early 1950s (Citation2011). In Czechoslovakia, however, the combination of pre-existing expertise and an authoritarian regime with the ability to implement plans on a grand scale resulted in a particularly voluminous ‘local avalanche’ of such estates, amidst the ‘universal formation’ of prefabricated systems building more generally (Trotsky, cited in Rosenberg, Citation2016) ().

Figure 6. Invalidovna Housing Estate, Prague (1964). Image, ŠJů used under CC BY-SA 3.0, Wiki Commons.

Zarecor (Citation2011) notes that the construction of prefab estates was intensified after the international success of the Czechoslovak pavilion at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958 – and in more ‘international and modernist style’ (Skrivánková et al., Citation2017). This 1958 ‘Expo’, famously symbolized by the Atomium, was the first to be held since the Second World War and was a highly symbolic event in the context of the Cold War. Coming between the Suez and Budapest crises (1956) and the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962), the Expo provided an arena for a different kind of superpower competition – to deliver better lives through science and culture. De-Stalinization in the wake of the 20th Congress offered a chance for architects in Warsaw Pact states to loosen the shackles of the ‘Socialist Realist’ style and re-engage with international modernism in style as well as substance.

The Czechoslovak pavilion specifically referenced the country’s (pre-communist) interwar functionalist architecture as well as contemporaneous international modernism. It consisted of three cube-like exhibition and performance spaces (from pre-cast concrete panels), linked by high and airy glass and steel corridors and offset by the sweeping curves of the restaurant that acted as the floating fourth corner of an irregular square. The building housed the avant-garde theatre of the Laterna Magika (Magic Lantern) and the multi-screen ‘Polyekran’, which combined performance and projection to stunning effect. As the New York Post had it: ‘[t]he Czechs alone met the challenge of the Brussels theme: What does the atomic age bring to your people?’ (Kramerová & Skálová, Citation2008, p. 23). Clearly, many sides of Czechoslovak life at the time were not on display – while propaganda certainly was – yet there was plenty for Czechs to take pride in: from future design classics to the beer better known by the German name under which it is internationally sold – Pilsner Urquell. The building and its exhibition, ‘One day in Czechoslovakia’ took home the Expo’s Grand Prix and a slew of other prizes (Kramerová & Skálová, Citation2008).

The ‘Brussels Dream’ was a vindication for Czech architects and designers, allowing them to spread their modernist wings again and show the world the quality of their work – but it had effects at home too. It also demonstrated the value of their cutting-edge modernist design for propaganda – as well as more substantial purposes – to the communist authorities. Moreover, it allowed them to directly ‘experience the free world’ including abstract art and to engage with their Western counterparts, which led Czech designers to develop the so-called Brussels style by Czech designers (Kramerová & Skálová, Citation2008). This was an updated version of interwar modernism fused with contemporaneous international ‘organic’ design (e.g. Alvar Aalto or the Eames) (Kramerová & Skálová, Citation2008, p. 49). Significantly, it was intended for mass rather than elite consumption and, overall, the Brussels effect reached far into the visual and material constitution of Czech society.

The Brussels Dream was anything but a ‘blip’. In the wake of the Expo the Institute for Macromolecular Chemistry in Prague (1960) featured the first use in the Czech lands of a ‘curtain-wall’ – perhaps the key feature of international high-modernism. The building’s designer, Karel Prager, went on to become one of the most internationally savvy and, later, celebrated architects of the communist era (see IV). In addition to the massive proliferation of Brussels-style interior design (see V), there was a boom in public buildings and housing estates in the high-modernist style (Skrivánková et al., Citation2017). This all contributed to a period that, to paraphrase Zarecor (Citation2011), could be called ‘Socialism with a Modernist Face’, which could not be explained by looking at ‘Czech’ architecture in isolation nor by considering the communist period as one of ‘post-cultural’, spatio-temporal isolation for Czech society more widely – as Kundera does (Citation1984). However, as I show below, the particularities that arose from combination also contributed to the construction of a particular international, socio-political understanding of difference ( and ).

V. Difference: slated for destruction

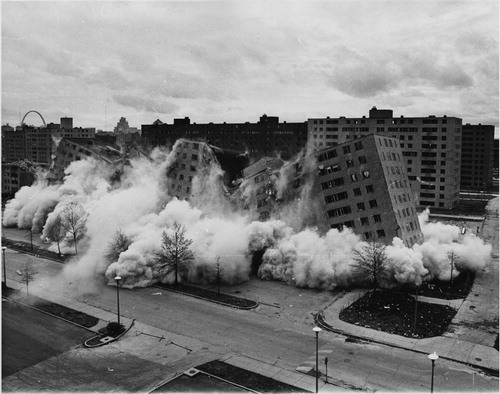

Modern Architecture died in St Louis, Missouri on July 15, 1972 at 3.32pm or thereabouts when the infamous Pruitt-Igoe [housing estate], or rather several of its slab blocks, were given the final coup de grace by dynamite. (Jencks, Citation2011, p. 1)

Figure 9. The demolition of the Pruitt Igoe housing estate, 1972. Image – US Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research – Public Domain.

Rosenberg argues that qualitative difference between societies is a necessary consequence of multiplicity stemming from geography and social development, which imply both differing distribution of resources (material and immaterial) and differing constellations of interaction and combination with other societies. He also notes that qualitative difference ‘finds expression in a concrete configuration of societies that co-exist in space and time’ (Rosenberg, Citation2016). Understanding the politics of constructing such spatio-temporal difference as well as the effects of its manifestations has long been a key concern for scholars of post-communist transitions (e.g. Stenning & Hörschelmann, Citation2008). Spatially, a lingering orientalism (well described elsewhere, e.g. Neumann, Citation1999; Wolff, Citation1994) meant that after 1989 Czech society remained generally designated as part of Eastern Europe – no matter that Prague is West of Vienna and that Austrian society is never designated as such. Temporally, the historicism that came packaged as the ‘End of History’ implied a backwardness to this East and the need for it to ‘catch-up’ with the West (Habermas, quoted in Scribner, Citation2003, p. 136). Spatial and temporal difference were thus translated into a hierarchical political relation between the societies of ‘the West’ and those of the post-communist states (Hutchings, 2008).

In Czechoslovakia the international, spatio-temporal politics of difference construed as ‘Eastern backwardness’ found its visual-material target in the architecture of the communist period. After the Velvet Revolution, these buildings were often perceived as anachronistic structures, made in a place that had failed to understand that modernism was already dead and reminders of that bad, old time. As influential architect Kucera (Citation2018, p. 3) puts it:

Due to the regime it was born into, Post-War architecture is still being stigmatized as Communist architecture without value. After 1989 it was very easy, and to some extent fashionable to condemn everything that happened in the past 40 years of communism, including architecture.

Despite their obvious differences from panel buildings, prominent communist-era public buildings realized in the ‘brutalist’ style came in for similar treatment, often in the face of objections from the Czech architectural community. Brutalism is heterogenous, emphasizing sculptural qualities, cantilevered or overhanging constructions and raw (brut, hence the name) or exposed materials. It has been a controversial strand of modernism internationally, but in the post-communist states it became particularly associated with the former communist regimes. A key example in Prague is the (now former) Czechoslovak Federal Assembly building at the head of Wenceslas square, next to the National Museum, designed by Karel Prager and symbolically situated on top of the old stock exchange. When still under construction it often appeared in the background of photos of the crushing of the Prague spring by Warsaw Pact forces in August 1968. As the seat of the federal assembly, it became a symbol of the ‘normalization’ period of ‘post-totalitarian’ governance under Gustav Husak (Havel, Citation2018).

The Federal Assembly building is, nonetheless, a world-class piece of architecture and the rival of anything from the time to be found in New York, London, Tokyo, Berlin or Paris (Horák, Citation2018; Sramkova, Citation2018).Footnote5 Along with Prager’s ‘New Stage’ of the National Theatre (1983), the Kotva (1975) department store and the Hotel Praha (1981) it testifies to the internationally attuned and high-quality architecture that flourished in the late communist era. It is odd, therefore, that the authors of a leading guide to Prague’s twentieth Century architecture emphasize that it was only in 1995, with the construction of Frank Gehry and Vlado Milunic’s ‘Dancing House’ that marked the ‘return of Prague to the International architecture scene’ (Kohout et al., Citation2008, p. 8). Or, rather, it is odd only if we exclude the wider international, inter-societal politics of the era of the ‘End of History’ ().

Figure 10. Former Czechoslovak Federal Assembly Building, Prague (1969). Image – Jirka23 – used under CC BY-SA 3.0,

What links the condemnation of the ostensibly very different panel houses and brutalist showpieces is that after 1989, they were both tarred with the brush of difference construed as backwardness compared to the West, where the demolition of many brutalist landmarks was already well under way and concrete estates were seen as sites of social ills. Rather than being a simple fact of difference, it is the international, inter-societal construction and inscription of difference that is a key political consequence of multiplicity. Hierarchies of this kind politicize international relations in ways that affect the lives of certain groups of people and societies – and the possibilities they can realize through interaction, combination, co-existence and dialectical change. In the Czech(oslovak) case, understanding how attitudes to communist-era architecture were internationally and inter-societally constructed and inscribed illustrates a broader politics of difference that had significant socio-political consequences for Czechs and Slovaks. They, along with other Central and East European were forced to play ‘catch-up’ in the 1990s and early 2000s, which had considerable geopolitical and psycho-social impact and which was also manifest in perceptions of architecture (Jansen, Citation2009; Kuus, Citation2004; For a review of literature on this topic see Stenning & Hörschelmann, Citation2008).

VI. Dialectical change: revival and revision

In this final section, I show how the last of Rosenberg’s consequences of multiplicity, dialectical change, is useful in understanding the international politics of ‘Czech’ architecture. To do so, I look at how changes in Czech relations to other societies and to the international have come hand in hand with changes in the condition, use of and attitudes toward the buildings discussed in the previous sections. Moreover, and as Rosenberg (Citation2016) notes, change is not a one way process and changes in Czech society have been and will continue to act back on other societies and the international, affecting the configuration and politics of co-existence, interaction, combination and difference ().

On 28 October 2018 the Czech National Museum re-opened after a multi-year renovation. Amidst much (literal) flag waving, the (still partial) re-opening coincided with the 100th anniversary of the declaration of Czechoslovak statehood and the 200th anniversary of the beginning of the first ‘national’ (pro patria) museum project. The restoration of both exterior and interior only accentuated the NM’s architectural similarity to comparable museums in Vienna (see above) but of greater political concern is that this re-opening – and flag waving – comes amid the biggest surge of Czech nativism since the 1940s (Sayer, Citation2018b).

This ‘nationalist revival’ became particularly apparent in relation to Europe’s migration crisis and the Czech refusal to take in refugees, participate in relocation programmes or help find common solutions to the crisis with fellow EU member states. President Milos Zeman campaigned successfully for re-election to ‘Stop immigrants […] This land is Ours!’ (Sayer, Citation2018b) and the Social Democrats (who governed from 2013 to 2017) campaigned (successfully) in 2018 local elections with slogans including ‘For a Havirov [a Czech city] without migrants’ (Simao, Citation2018). The new nativism in Czech society makes the revived museum again a potential focal point for re-interpreting and reconfiguring Czech society’s international co-existence – particularly in terms of its relations with fellow EU member states and the EU itself.

The nationalist revival also casts a shadow over some of the modernist architectural highlights for which Prague belatedly gained recognition in the post-1989 period (Kohout et al., Citation2008; Sayer, Citation2013). Since 1995, the functionalist ‘Trade Fair Palace’ (1928, discussed above) has been the main building of the National Gallery (NG). 2018 saw the launch of a semi-permanent exhibition on the art and culture of the Czechoslovak First Republic, which is the most imaginatively curated and best installed show that the NG has yet made from its permanent collection. It showcases the multiple modernisms that made interwar Czechoslovakia such a dynamic and thrilling society: a society that interacted confidently and openly with other societies.

Despite the acclaim, however, the architectural dynamism, boldness and internationalism that characterized the First Republic – and which are a ritually celebrated part of the nation’s past – are radically divorced from present Czech societal practice. Rather than being a guiding spirit for contemporary creation and international interaction, modernism has been reduced to a style – and one often presented in national rather than international terms. While some experts seek to show merit in the ‘austerity’ of Czech architecture and planning since 1989 (Svacha, Citation2004), others such as Eva Jiřičná, a leading (internationally active) Czech architect lament Prague’s conservatism and regression into an ‘Urban Skansen’ with the emphasis on preservation rather than creativity and boldness (Willoughby, Citation2016).

Reducing modernism to style is not a Czech problem alone, but it particularly jars here, especially when modernism is explicitly claimed, including by experts, as part of ‘our [Czech] cultural heritage’ (Asiedu, Citation2007). This falls flat as ‘heritage implies the [building] is significant in somehow contributing positively to the construction of your present-day identity. To claim something as heritage is to acknowledge a debt’ (Whiteley, Citation1995). This debt is international, while the current presentation of modernism as Czech heritage tends to emphasize its national aspects. This may be considered, locally, to be a necessary – and pride restoring – corrective to having been overlooked in the past by Western experts (Kohout et al., Citation2008), but the tendencies to national presentation and the ‘heritagization’ of modernism to style run counter to the very legacy they claim. Both Interwar and postwar modernisms in the Czech lands were avowedly international and style followed (political and social) spirit as much as form followed function (Zusi, Citation2004, Citation2008).

The NG curators actually comment on the problem of reducing modernism to a ‘style’ – in relation to the ‘Brussels Style’ that emanated from the Czechoslovak success at Expo 58 to make ‘a piece of Brussels for everyone’ (Kramerová & Skálová, Citation2008). In a gallery wall-text, the curators argue that this turned the Brussels Style into ‘a kind of national folklore […] leading to its atrophy’ which nicely captures the tension between the avant-garde and democratic impulses in many modernisms (Zusi, Citation2008) It may be coincidence that they do so in relation to a communist-era, mass phenomenon rather than the more elite First Republic modernisms but, regardless, it helpfully points to another aspect of relational change as a consequence of Czech multiplicity. From the early 2000s there has been an increasingly contested politics of memory in relation to the communist period – including many interventions aiming to reappraise the qualities of the architecture of the time.

A 2008 exhibition called ‘The Brussels Dream’ at the City of Prague gallery was one of the first major public celebrations of communist-era architecture and design (Kramerová & Skálová, Citation2008). This marked a break from previous blanket condemnations of the communist period in favour of exploring the more nuanced lived experiences of that time (Stenning & Hörschelmann, Citation2008). Subsequent years have seen resurgent demand for ‘Brussels Style’ interior decoration, and for the later (1970s and 1980s) home furnishings and accessories that adorned the childhoods of the generation that grew up during the ‘Normalization’ period. The founders of the Nanovo furniture salvage and restoration company, key actors in this trend, openly admit to having been inspired by the examples they found in Berlin, but are now internationally recognized themselves (Tallis, Citation2012, Citation2014).

Attitudes toward concrete panel buildings have also changed somewhat in recent times. International and local research has shown the vibrancy of social life as well as the high-quality planning and connectedness of many of the concrete estates (Skrivánková et al., Citation2017; Spacek, Citation2012; Zarecor & Špačková, Citation2012). With notable exceptions in particularly deprived areas (Sykora, Citation2010), they have avoided the social ills that afflicted similar projects in the West (Skrivánková et al., Citation2017). Much needed renovation has seen foam cladding added atop the concrete panels to improve the insulation and then painted in a variety of colours (in consultation with residents) (Zarecor, Citation2008). The renovated estates are popular (and not the cheapest) places to live, valued much more domestically than internationally.

By contrast, brutalist architecture has seen a more general, international revival and re-appraisal (e.g. Meades, Citation2014), which also became locally apparent in exhibitions at the leading Czech architecture gallery (2010), the Applied Arts gallery (2012), at the NG on Karel Prager’s work (2013–2014) and in publications such as Aliens and Herons (Karous, Citation2014) Brutal Prague (Sramkova, Citation2018) or Prague, Brutally Beautiful (Horák, Citation2018) – all of which have kicked back at previous denigrations of communist-era architecture. The renovation of key buildings such as the ‘New Stage’ of the National Theatre, and the transformation of the former Federal Assembly Building into the ‘New Building’ of the National Museum exemplify the effects of this dialectical change. Nonetheless, the demolition of the ‘TransGas’ building (2019) and the Hotel Praha (2013), among others, shows that the struggles over brutalism continue.

All of this shows how dialectical changes in Czech society’s relation to other societies and to the international (in its various consequences) have impacted on the uses, perceptions and condition of the architecture discussed in the previous sections – and how they have and can act back on the international, especially with regard to the Czech position in the EU.

VII. Conclusion: an international politics of Czech architecture

In the introduction, I noted Lisle’s (Citation2016) concerns that the project of International Political Sociology (IPS) had come to be dominated by Sociology at the expense of the international and the political. By bringing Justin Rosenberg’s framework of ‘Multiplicity’ (Citation2016) to bear on concerns of IPS – in this case visual-material culture as they intersect in architecture – I have shown one way to address the concerns of Lisle and related issues raised by Austin (Citation2017) about the political purchase of IPS. I have explicitly done so in a way that rejects the abandonment of the international advocated by some IPS and IR scholars (Bartelsen, Citation2018; Nabers & Stengel, Citation2019). I have, instead, shown the value of and potential for a revival of the international as an analytic and heuristic device in IPS and IR more widely.

Employing Multiplicity as an interpretive framework to explore architecture through the five consequences of multiplicity that Rosenberg identifies, as I have done here, requires IR scholars to explicitly employ the international as an analytical and interpretive lens, rather than seeing it as the object to be analyzed or interpreted. It requires IPS scholars to pay equal attention to – and use – the international in conjunction and on an equal footing with the political and the social. In the example that is worked through in the five sketches presented in this article, I interpret ‘Czech’ architecture through the lens of the international and the related politics of inter-societal relations. In some instances this amounted to connecting the dots within and between various extant analyses, often in different disciplines, academic and journalistic, to clearly draw out the effects of the international. In others it went deeper and wider, providing a new perspective on the construction, design, uses, and perceptions of certain buildings or patterns of construction, renovation, and demolition. Cumulatively, the analysis and interpretation, which I summarize here, show the causally consequential role of the international which, rather than being merely an extension of the domestic social space (e.g. Sayer, Citation2019), has a constitutive function for architecture as well as other socio-political phenomena.

In the first section, I showed why key Czech ‘national’ buildings – the National Theatre and National Museum – look so similar to their counterparts in Vienna, the capital of the empire from which Czechs were seeking independence. I did so by focusing on the politics of changing forms of Czech society’s co-existence with other societies, with particular regard to the quest for national recognition. Doing so highlighted that, despite being built to showcase and embody the specificity of Czech national culture, these buildings were also entangled in the hierarchical, imperial politics of the time. Thus, as well as being domestic ‘mirrors of identity’ (Sayer, Citation2000), which sought to present a capable and coherent national community, they needed to do so in a form that was also externally recognizable. Their neo-renaissance style also offered a form of subtle subversion of Austrian rule, emphasizing Italian rather than Germanic tradition, and contrasts with the more strident assertions of national identity visible in later buildings.

In the second section, I showed how international interaction was essential to the particularly prolific flourishing of modernism in the Czech lands, which has recently been celebrated as part of a distinctly national golden age. This analysis highlighted ways in which Czech manifestations of modernism, particularly functionalism, were influenced by but also influenced ‘the international style’ that has become celebrated as one of the most emblematic and important styles of architecture of this or any other period. In the Czech lands this international, cultural modernism was entwined with official government strategies of interaction with international society more generally: to take advantage of statehood’s opportunities and guard against its dangers. While it was not universally popular, internationally-influenced Modernism changed the look and materiality of significant swathes of the Czech lands. It proved insufficient, however, to overcome the nationalist realpolitik of the late 1930s that saw Czechs’ political subjectivity in international society sacrificed on the altar of appeasement.

Third, I looked at Czech Cold War architecture through the combination facet of Multiplicity. I thus refuted claims that Czech cultural production, including architecture, was doomed to inferiority by dint of its supposed isolation from the West or by the oppressive character of the domestic communist regime. While the regime was undoubtedly oppressive, neither the panel buildings that make up the huge numbers of concrete estates in the country, nor much of the showpiece public architecture are either low-quality or out of kilter with architecture elsewhere at the time. I showed that far from being spatially or temporally isolated, the architecture of the time was linked to both the Czech past and the wider contemporaneous world. The success of the Czech pavilion at Expo 58, as well as its subsequent adaptation for mass production and the adoption of ‘high-modernism’ by Czech architects, demonstrate combination with, rather than isolation from Western architecture and design and question some influential narratives of the cold war and the Eastern bloc.

Nonetheless, the particular combination of domestic circumstances (especially the oppressive, dogmatic, and domestically powerful regime) as well as changing international trends in architecture resulted in different configurations of architecture and construction in the Czech lands than those in the West. As I show in the fourth section, however, it was not the fact of this difference but the way it was constructed, inscribed and interpreted that led to underserved castigation of communist-era architecture (domestically and internationally). In the context of the ‘death’ of modernism, ‘the end of history’ and post-communist transitions, this unmerited condemnation was typical of a politics of difference construed as the relative backwardness of ‘Eastern’ Europe in comparison to the always already advanced West that heavily influenced Czech individual and collective political subjectivity in the period after the Velvet Revolution in 1989. This analysis newly connects revisionist understandings of Czech architecture with critical literatures on post-communist transition, and shows how attitudes to architecture – sometimes claimed to be ‘objective’ or merely reflecting ‘common sense’ – were actually deeply embedded in the international politics of the time.

Like many other societies (Sayer, Citation2018a), Czech society is divided as to the best ways of co-existing in multiplicity and of relating to the international (Eberle, Citation2018). How these issues are addressed, and the struggles inherent in doing so, will impact on Czech architecture in the future, as well as on the perception of architectures of the past. The last decade has seen growing domestic dissatisfaction with the post-89 international political settlement and the position of Czech society in and through its relation to other societies. Czech re-evaluations of the communist period and the salvaging of individual dignity and national pride, from previous blanket castigation, have come hand-in-hand with revived nationalism and increased questioning of the benefits of EU membership and international interaction more generally. Rejecting the inscription of difference as backwardness, Czechs may be embracing a new form of difference: difference by choice. As Czech PM Andrej Babis put it: ‘We know what European Values are and we have our own values, different values’ (Babis, Citation2018). Conservatism in architecture and socio-political nativism found visual-material form in the restored and (temporarily) flag-covered national museum, and have their counterpart in attempts to reduce modernism to a locally well-handled aesthetic style rather than an international socio-political spirit. Nonetheless, counter-currents are observable in battles over brutalism, in the politics of planning in Prague as well as in the largest demonstrations against the government since 1989.

As this piece shows, international politics has much to reveal about architecture, if the right lens is applied. Multiplicity has much to offer in bolstering the international as well as the political angles of its analysis of visual and material culture and thus provides a way of reviving, rather than abandoning, the international in IPS. Moreover, the analysis presented here shows that International Relations can add to the analyses and interpretations of other disciplines in useful ways that shed new, international light on why buildings are built or destroyed, why their architectures take the form they do, as well as how they are used and perceived. As Dejan Sudjic writes, ‘Objectively, there is no right answer to the question of where to put a window’ (Citation2006, p. 218). It is architecture that provides the rational for why windows – and other features – are put in certain places and not others and how compelling that placement is as well as what the uses and affects of a building will be. Understanding international politics is an important aspect of understanding architecture and multiplicity provides us with the tools to do so.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the Czech Government for the opportunities their grant provided and to the Institute of International Relations Prague for supporting me in using the grant to undertake a visiting fellowship at the ANCB – Aedes Metropolitan Laboratory in Berlin, which facilitated the research. I am also thankful to Miriam Mlecek, Dunya Bouchi, the ANCB director Hans-Jurgen Commerell and the ANCB team for welcoming and hosting me as a visiting fellow. I would also like to thank the editors of this special issue, Justin Rosenberg and Milja Kurki, for their support and encouragement, as well as to the participants in the Multiplicity workshop at EISA EWIS2018 in Groningen – for cultivating friendships as well as ideas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Benjamin Tallis http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3681-9689

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Benjamin Tallis

Benjamin Tallis is Senior Researcher at the Institute of International Relations in Prague, where he also edits the SCOPUS listed journal New Perspectives. He has recently been a visiting fellow at the ANCB Architecture Centre in Berlin and the IFSH in Hamburg. Tallis’ research focuses on security politics and cultural politics in Europe. His work has appeared in journals including Security Dialogue, International Politics, and International Relations. Tallis has been a board member and Executive Secretary of EISA, programme chair of EWIS 2017 and 2018 and main organizer of the EISA PEC18 Conference in Prague. He regularly provides policy advice and consultancy for governments around Europe and around the world and is a former security practitioner for the EU and OSCE, as well as the creator of the Prague Insecurity Conference. Tallis regularly appears in the European media and has written extensively on art, architecture, and design for publications including Art Review, The Modernist and Umelec. He created and curated the Common Space Gallery in Prague.

Notes

1 Rosenberg originally presents the consequences of multiplicity in the following order: co-existence, difference, combination, interaction and dialectical change. Recognising them to be concurrent rather than chronologically-ordered also allows them to be re-ordered. This facilitates the structuring of a coherent narrative with a manageable amount of historical context and detail in the space available.

2 This competition was featured in a short video in the exhibition to mark the grand re-opening of the National Museum in October 2018, coinciding with the 100th anniversary of the founding of the first Czechoslovak republic. Visited by the author in November 2018.

3 The Tugendhat Villa and the Baťa shoe store on Wenceslas Square were among the Czechoslovak buildings included in the exhibition catalogue for The International Style.

4 Uniquely in European history – see Sayer, Citation2019 or, for an in-depth account, Judt (Citation2006, p, 138).

5 As I discuss in the next section, attitudes to Brutalism have changed somewhat in the last decade but it remain a contentious style.

References

- Adler-Nissen, R. (2016). Towards a practice turn in EU studies: The everyday of European integration: Towards a practice turn in EU studies. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(1), 87–103. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12329

- Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism (Rev. and extended ed.). London, NY: Verso.

- Aradau, C. (2013). Infrastructure. In Research methods in critical security Studies: An introduction (pp. 181–185). London: Routledge.

- Asiedu, D. (2007). Brno city hall protests as valuable Tugendhat Villa Statue is sold to foreign collector. Radio Prague. Retrieved from https://www.radio.cz/en/section/curraffrs/brno-city-hall-protests-as-valuable-tugendhat-villa-statue-is-sold-to-foreign-collector

- Austin, J. (2017). Post-critical IR? Mimeo.

- Austin, J. (2018). How is the world composed? Retrieved February 16, 2018, from World Political Compositions website: http://www.worldpoliticalcompositions.com

- Babis, A. (2018). Speech at Globsec2018. Presented at the Globsec, Bratislava. Retrieved from https://www.byznysnoviny.cz/2018/05/18/babis-globsec-evropa-ma-problem-ruskem-usa-i-migraci/

- Bartelsen, J. (2018). From the international to the global? In A. Gofas, I. Hamati-Ataya, & N. Onuf (Eds.), The Sage handbook of the history, philosophy and sociology of international relations (pp. 33–45). London: SAGE.

- Bleiker, R. (2009). Aesthetics and world politics. Retrieved from http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=555449

- Bleiker, R. (Ed.). (2018). Visual global politics. London, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Brown, C. (2013). The poverty of grand theory. European Journal of International Relations, 19(3), 483–497. doi: 10.1177/1354066113494321

- Bueger, C., & Gadinger, F. (2014). International practice theory: New perspectives. Houndsmill: Palgrave Pivot.

- Carr, E. H. (2016). The twenty years’ crisis, 1919–1939. London: Macmillan/Springer Nature.

- de Meyer, D. (2006). Writing architectural history and building a Czechoslovak nation, 1887–1918. In J. Purchla, W. Tegethoff, C. Fuhrmeister, & L. Galusek (Eds.), Nation, style, modernism (pp. 75–93). Krakow: Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte and International Cultural centre.

- Eberle, J. (2018). Desire as geopolitics: Reading the glass room as central European fantasy. International Political Sociology, 12(2), 172–189. doi: 10.1093/ips/oly002

- Edkins, J., & Zehfuss, M. (Eds.). (2009). Global politics: A new introduction. London, NY: Routledge.

- Frampton, K. (1993). A modernity worthy of the name. In The art of the avant-garde in Czechoslovakia : 1918 - 1938 (pp. 213–231). Valencia: IVAM Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Centre Julio Gonzalez.

- Fukuyama, F. (1992). The end of history and the last man. London: Hamilton.

- Hanley, S. (1999). Concrete conclusions: The discreet charm of the Czech Panelak. Central European Review, 0(22), Retrieved from http://www.ce-review.org/authorarchives/hanley_archive/hanley22old.html

- Hanley, S. (2008). Modernize the Czech Republic? Childsplay. Retrieved February 20, 2019, from Dr Sean’s Diary website: https://drseansdiary.wordpress.com/2008/08/14/modernize-the-czech-republic-childsplay/

- Hansen, L. (2015). How images make world politics: International icons and the case of Abu Ghraib. Review of International Studies, 41(02), 263–288. doi: 10.1017/S0260210514000199

- Havel, V. (2018). The power of the powerless. London: Vintage Classics.

- Herscher, A. (2004). The mediation of building: Manifesto architecture in the Czech avant-garde. Oxford Art Journal, 27(2), 193–217. doi: 10.1093/oaj/27.2.193

- Hitchcock, H.-R., & Johnson, P. (1997). The international style. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Holubec, S. (2014). A ‘golden twenty years’, or a bad stepmother? Czech communist and post-communist narratives on everyday life in interwar Czechoslovakia. Acta Poloniae Historica, 110, 23. doi: 10.12775/APH.2014.110.02

- Horák, O. (2018). Praha brutálně krásná: mimořádné stavby postavené v Praze v letech 1969–1989.

- Hubatová-Vacková, L., & Pravdová, A. (2018). First Republic 1918–1938. Prague: Narodni Galerie (Czech National Gallery).

- Jansen, S. (2009). After the red passport: Towards an anthropology of the everyday geopolitics of entrapment in the EU’s ‘immediate outside’: After the red passport. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 15(4), 815–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9655.2009.01586.x

- Jencks, C. (2011). The story of post-modernism: Five decades of the ironic, iconic and critical in architecture. Chichester: Wiley.

- Judt, T. (2006). Postwar: A history of Europe since 1945. London: Penguin.

- Karous, P. (Ed.). (2014). Vetřelci a volavky: atlas výtvarného umění ve veřejném prostoru v Československu v období normalizace ; (1968 - 1989) = Aliens and herons ; A guide to fine art in the public space in the era of normalisation in Czechoslovakia ; (1968 - 1989) (Vyd. 1). Prague: Arbor Vitae [u.a.].

- Koeltzsch, I., & Konrád, O. (2016). From ‘Islands of Democracy’ to ‘Transnational Border Spaces.’ State of the art and perspectives of the historiography on the first Czechoslovak Republic since 1989. Bohemia. Zeitschrift Für Geschichte Und Kultur Der Böhmischen Länder, 56(2), 285–327.

- Koerner, J. L. (2009). Caspar David Friedrich: And the subject of landscape. London: Reaktion Books.

- Kohout, M., Šlapeta, V., & Templ, S. (2008). Prague 20th century architecture. Praha: Zlatý řez.

- Kramerová, D., & Skálová, V. (Eds.). (2008). The Brussels dream: The Czechoslovak presence at Expo 58 in Brussels and the lifestyle of the early 1960s. Prague: Galerie hlavního města Prahy.

- Kucera, P. (2018). Prologue. In Brutal Prague (p. 3). Prague: Architektura 489.

- Kundera, M. (1984). A kidnapped west or culture bows out. Granta, 11, Retrieved from https://granta.com/a-kidnapped-west-or-culture-bows-out/

- Kuus, M. (2004). Europe’s eastern expansion and the reinscription of otherness in East-central Europe. Progress in Human Geography, 28(4), 472–489. doi: 10.1191/0309132504ph498oa

- Lisle, D. (2016). Waiting for international political sociology: A field guide to living In-between. International Political Sociology, 10(4), 417–433. doi: 10.1093/ips/olw023

- Meades, J. (2014). Bunkers, Brutalism and Bloodymindedness. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b03w7b7x

- Nabers, D., & Stengel, F. A. (2019). International/global political sociology. In R. Marlin-Bennett (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of international studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.371

- Neumann, I. B. (1999). Uses of the other: “The East” in European identity formation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Orzoff, A. (2009). Battle for the castle: The myth of Czechoslovakia in Europe, 1914–1948. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Rosenberg, J. (2016). International relations in the prison of political science. International Relations, 30(2), 127–153. doi: 10.1177/0047117816644662

- Salter, M. B. (Ed.). (2015). Making things international. 1: Circuits and motion. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Sayer, D. (2000). The coasts of Bohemia: A Czech history. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Sayer, D. (2013). Prague, capital of the twentieth century: A surrealist history. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sayer, D. (2018a). Iron curtains of the mind. New Perspectives: Interdisciplinary Journal of Central & East European Politics and International Relations, 26(2), 133–136.

- Sayer, D. (2018b). Sudeten ghosts. New Perspectives: Interdisciplinary Journal of Central & East European Politics and International Relations, 26(2), 129–132. doi: 10.1177/2336825X1802602S06

- Sayer, D. (2019). Prague at the end of history. New Perspectives: Interdisciplinary Journal of Central & East European Politics and International Relations, 27(2), 149–160. doi: 10.1177/2336825X1902700211

- Schwarzbaum, L. (2015). The Monoliths of Bratislava. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/01/travel/slovakia-bratislava-tourism.html

- Scribner, C. (2003). Requiem for communism (1st MIT Press paperback ed). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Simao. (2018). Babiš odmítá migranty v Česku, členka ČSSD v Havířově. Vezmeme jich 5 tisíc, žádají Zelení. Blesk.Cz. Retrieved from https://www.blesk.cz/clanek/volby-komunalni-volby-2018/563629/babis-odmita-migranty-v-cesku-clenka-cssd-v-havirove-vezmeme-jich-5-tisic-zadaji-zeleni.html

- Skrivánková, L., Svácha, R., & Lehkozivová, I. (2017). The paneláks: Twenty-five housing estates in the Czech Republic. Prague: The Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague.

- Spacek, O. (2012). Czech housing estates: Factors of stability and future development. Czech Sociological Review, 48(5), 965–988.

- Sramkova, I. (Ed.). (2018). Brutal Prague. Prague: Architektura 489.

- Stenning, A., & Hörschelmann, K. (2008). History, geography and difference in the post-socialist world: Or, do we still need post-socialism? Antipode, 40(2), 312–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2008.00593.x

- Sudjic, D. (2006). The edifice complex: How the rich and powerful shape the world. London: Penguin books.

- Svacha, R. (2000). Rekaptiulace Sidlist [Recapitulation of the housing estates]. Stavba, VII(5), 36–41.

- Svacha, R. (2004). Czech architecture and its austerity: Fifty buildings 1989–2004 (1st ed). Praha: Prostor.

- Svobodová, M. (2017). The Bauhaus and Czechoslovakia 1919–1938: Students, concepts, contacts. Praha: Kant.

- Sykora, L. (2010). Rezidenční segregace (Residential Segregation) (No. Report for Czech Ministry of Regional Development). Prague: Charles University, Centre for Urban and Regional Research.

- Ševčíková, L. (n.d.). An introduction to Czech Architecture. Culturenet. Retrieved from http://www.culturenet.cz/en/Czech-in/architecture/an-intro-to-czech-architecture/

- Tallis, B. (2012). Indecent exposure or: The Brussels dream – The Czechoslovak Expo ‘58 Pavillion. The Modernist, 3(6).

- Tallis, B. (2014). Nanovo: From the cosy dens of another time. The Modernist, 3(11).

- Teige, K. (2002). The minimum dwelling ( E. Dluhosch, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.

- Therborn, G. (2002). Monumental Europe: The national years. On the iconography of European capital cities. Housing, Theory and Society, 19(1), 26–47. doi: 10.1080/140360902317417976

- Waever, O. (2007). Still a discipline after all these debates? In T. Dunne, M. Kurki, & S. Smith (Eds.), International relations theories: Discipline and diversity (1st ed., pp. 302–330). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Whiteley, N. (1995). Modern architecture, heritage and Englishness. Architectural History, 38, 220. doi: 10.2307/1568629

- Willoughby, I. (2016). Eva Jiřičná, Part 2: Wenceslas Sq. “Biggest Loss” in post-1989 development of Prague. Radio Prague. Retrieved from https://www.radio.cz/en/section/one-on-one/eva-jiricna-part-2-wenceslas-sq-biggest-loss-in-post-1989-development-of-prague

- Wolff, L. (1994). Inventing Eastern Europe: The map of civilization on the mind of the enlightenment. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Zarecor, K. E. (2008). The rainbow edges: The legacy of communist mass housing and the colorful future of Czech cities. Architecture Conference Proceedings and Presentations. Presented at the without a hitch: new directions in prefabricated architecture. Retrieved from https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_conf/26

- Zarecor, K. E. (2011). Manufacturing a socialist modernity: Housing in Czechoslovakia, 1945–1960. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Zarecor, K. E. (2012). Socialist neighborhoods after socialism: The past, present, and future of postwar housing in the Czech Republic. East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures, 26(3), 486–509. doi: 10.1177/0888325411428968

- Zarecor, K. E., & Špačková, E. (2012). Czech paneláks are disappearing, but the housing estates remain/České paneláky miznú, ale sídliská zostávajú. Architektura & Urbanizmus, 46(3), 288–301.

- Zusi, P. (2004). The style of the present: Karel Teige on constructivism and poetism. Representations, 88(1), 102–124. doi: 10.1525/rep.2004.88.1.102

- Zusi, P. (2008). Tendentious modernism: Karel Teige’s path to functionalism. Slavic Review, 67(4), 821–839. doi: 10.2307/27653026