ABSTRACT

This paper addresses the deepening vulnerability of both domestic and international migrant workers to contemporary slave labour and the challenges for its eradication in the Brazilian Amazonian state of Mato Grosso. Drawing upon the experiences of 40 workers ‘rescued’ from contemporary slave labour, the paper shows that the repetitive experiences of contemporary slave labour by subjects and the authoritarian turn in Brazil evokes a conceptual reinterpretation of solidarity and its operationalization. It must move away from the distinct liberal approach in the state paradigm to focus on class and agrarian based solidarity and their understanding of liberation. The paper redefines solidarity as structural and relational notion that engages with the epistemic insight of unfree workers to define the terms of their own freedom, pointing towards humanizing, and self-emancipating alternatives that challenge roots of class oppression and slave labour.

Introduction

The persistence of slave labour points out the need to consider how solidarity is defined in antislavery initiatives. In the Brazilian state, the combat of slave labour’ is framed within liberal assumptions of a malfunction in the otherwise freely negotiated employment relationship, an anomaly pinned to western and highly individualized notions of modernity, liberty and emancipation. The institutionalized form in which slave labour is investigated and ‘victims’ are rescued has earned Brazil recognition for efforts to combat slave labour. The evolution of these state-run programmes and operations; however, bely the historic struggles of working class and peasant movements; and the hierarchical structures of state rescue run counter to these popular actions against slavery that, inspired by anti-colonial liberation movements, have distinct understandings and practices of self-emancipation. While they routinely engage with and inform state apparatus, their collective strategies to confront slave labour and their emphasis on horizontal solidarity offer alternative routes beyond, and indeed in spite of, the state paradigm.

Why this matters is threefold. Firstly, the persistent reproduction and indeed repetition of slave labour by the subjects in this paper points to the inadequacy of individualized rescue ‘missions’, of the assumptions made of oppressed workers, and of the reinsertion into the labour market as an idealized form of solidarity.

Secondly, a distinct elitism in Brazil’s capital-labour relations that was discursively acknowledged by the Workers Party governments was not addressed in ways that prevented a rise in slave labour in the country. The strengthening of labour inspection and rescue operations rubbed up against the ongoing processes of neoliberal deregulation, precarization of employment and marketization of social policies.

Thirdly, state structures are now subject to a radical authoritarian turn in Brazil’s neoliberal agenda. The dismantling of statutory labour protections and labour agencies along with public provision by philanthropy and military personnel shape the expansion of slave labour among a growing vulnerable workforce, including domestic and international migrants.

This paper finds that fault lines running through the official strategies to combat slave labour and the increasing complexity of employment relationships are visible in the testimonies from internal migrants in agriculture and more recently arrived immigrants to Brazil who were recruited to construction work. Furthermore, a distinct differentiation between how the state and civil society/religious groups have engaged with internal migrants and those arriving from overseas illuminates diverging imaginaries of, and limitations to, solidarity towards combatting and ending slave labour.

To make visible practices and possibilities for combatting and transgressing the systemic organization of slave labour, the article focuses on two spaces of political mobilization; that of hierarchical, state governed politics of rescue and reincorporation of workers into the labour market; and that of horizontally constructed networks of solidarity and liberation from slave labour. It is between these two poles that the experiences of workers in Mato Grosso, Brazil’s agroindustrial powerhouse and subject of the second largest number of slave labour operations in Brazil, are considered.

With a focus on Brazilian internal migrant workers ‘rescued’ from agricultural labour and more recently arrived migrants from Haiti and Venezuela found working in slave conditions in construction, this paper seeks to address the following questions. In the first place the paper explores the distinctly philanthro-capitalist assumptions and operations of the state funded institutions combatting slave labour and asks; (i) what does the reproduction and repetition of slave labour tell us about the limits to the contemporary, individualized approach to solidarity within workers' struggles? Secondly, the study considers the contemporary conditions of slave labour through the prism of workers’ experiences. In light of persistent vertical, humanitarian and entrepreneurial forms of rescue across successive governments and radical authoritarian turn in Brazil the paper investigates: (ii) what lessons can be drawn from contemporary examples of class based solidarity to inform struggles against slave labour beyond individualized responses and into the spheres of work, family and community life?

To investigate these questions the study first revisits how western liberal conceptions of both slave labour and solidarity preclude alternative interpretations that have their basis in liberatory struggles and experiences from the Global South. By emphasizing the latter, the study seeks to shift from a consideration of workers as passive recipients of rescue and philanthropy towards an emphasis on their agency, that is, their subjective and collective knowledge as a basis for social transformation. The methods by which secondary and primary data was collected in the state of Mato Grosso is then presented. The ideological and mechanical underpinning of Brazil’s contemporary approach to combatting slave labour is then considered, with the particular historical and economic context of Mato Grosso provided. This serves as a backdrop to the testimonies from workers rescued from slave labour in agriculture and construction that precede the final appeal to a twenty-first century solidarity amidst social fragmentation, deepening vulnerability and economic crisis in Brazil. The paper concludes defining solidarity as a structural and relational notion that engages with the epistemic insight of unfree workers in tracing roots of their oppression and slave labour, pointing towards humanizing alternatives that challenge these constructions. It is a historical, political and contextualized effort that is sensitive of asymmetrical power relations, social divisions and communal aspirations of workers for social transformation.

Contemporary slave labour and modernity

Slave labour has been observed, analysed and documented across the production and circulation of commodities central to contemporary commercial and domestic life. Tea, palm oil, electronics, garments, cotton, metals, sugar and meat are just some commonly consumed goods that have been linked to slavery (Lebaron et al., Citation2018).

In this sense, the common use of the term ‘modern slavery’, however, remains problematic. This is not least because liberal modernity as a political and philosophical project was built on the back of the slave trade and colonialism in the beginning of sixteenth century (Dussel, Citation1977). Enslavement (with its different forms over time and space) involved instrumentalizing the existence, and destruction, of human bodies and entire populations with wealth returned to imperial countries for their particular construction of modernity. As Dussel (Citation1977, p. 14) states, the modernity is not characterized by, ‘I think, therefore I exist’, of Descartes, but by ‘I conquer’, ‘I enslave’, ‘I win’. The modernist project thus justified the slave trade of Africans, indigenous labour exploitation and land degradation on plantations in the West Indies, North, Central and South America, and paved the way for capitalist and patriarchal forms of domination that have played a determining role in globalized social structures since the seventeenth century (Davidson Citation2015; Berry, Citation2017; Rodney, Citation2018; Sousa Santos, Citation2018).

We do indeed need to consider the differences between colonial slavery from sixteenth to nineteenth centuries and the wide spectrum of labour relations in ‘post-emancipated’ societies in more recent times. Yet, the juridical abolition and the passage from slave labour to ‘free’ wage labour in many societies has retained social, cultural, political, juridical and economic mechanisms of coercion upon the new ‘freed’ class of workers and new forms of slave labour that were constructed or expanded in response to abolition. A set of post-abolition legal conventions and definitions have emerged in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries to address the plurality of slavery types; forced labour, debt bondage (or neo-bondage), servitude, sexual slavery, child soldiers, forced marriage, human trafficking, and these regard the right of ownership, compulsory labour, servile status, freedom to choose the job and human trafficking (Bales, Citation2005). Beyond juridico-political considerations, there is an ongoing theoretical debate on unfree labour that pivots between those insisting on a binary distinction between free labour exchange on the market and unfree labour subject to non-economic coercion (Rioux et al., Citation2020); a more classical Marxian reading that associates unfree labour with remnants of pre-capitalist society (e.g. Rao, Citation1999); and those that interpret labour as being more or less free along a spectrum of labour relations within capitalist societal structures whereby oppressive class relations are inherent to its reproduction, and indeed exacerbated by neoliberalism (Banaji, Citation2003; Breman, Citation1994; Lerche, Citation2011).

Following the latter analysis, slave labour is not marginal to our economic system, but related to the decomposition-recomposition of working class in the labour process (Brass, Citation2010). Given that under capitalism workers are ‘freed’ from the means of production but only so far as they must sell their labour for a wage to avoid hunger, many scholars following a Marxist theory of the economy and social structures would suggest that all labour is unfree (e.g. Gordon, Citation2018, p. 2). This echoes the analysis of Marcuse (Citation1973, p. 973), for whom industrialization makes a slave of all, in that the worker is reduced to, ‘mere instrument and for the reduction of man to the condition of thing’. This has some resonance in Brazil’s conceptualization of slave labour that attempts to move beyond the notion of liberty towards individual dignity. However, the complex nature of capital accumulation and multidimensional boundaries of oppression identified in this article highlights external conditions upheld by the state and broader legal system which favours the systemic reproduction of slave labour in Mato Grosso. In this sense, Lerche (Citation2011, p. 7) points to the danger of normalizing degrading work through constructing a boundary between free and unfree labour, yet argues that conditions for unfree labour ‘share characteristics with a wider set of relations, both with regard to the underlying processes which lead to their creation by capital and concerning conditions of work and pay for labour’.

Against a backdrop of increasing social inequalities, work precarity, the further erosion of welfare, and a structural squeeze in economic choices facing workers (who often knowingly take work that could be classed as unfree), the insistence that coercion to accept particularly degrading work is a result only of non-economic forces (e.g. violent threats, debt bondage) is increasingly difficult to uphold. After all, a relentless drive to cheapen and control labour follows the very logic of capital. The degree to which this is done varies along a spectrum (Lerche, Citation2011), but is constitutive of neoliberal, capital social structures that are imbued with non-economic, oppressive power differentials (Banaji, Citation2003) and comprise a complexity of labour-capital arrangements (Linden, Citation2013).

Yet here, it is argued, that distinctions are important on the basis of material structures of inequality within and across nations. While it is possible to find a range of workers dispossessed and alienated from the products of society and working under oppressive labour relations, contemporary slave labour could be said to mark an important intersection between exploited, expropriated and violated bodies, between land and labour within historical and ongoing structures of subordination (i.e. colonialism, welfare systems and politics of race). These characterize particular sets of unfreedoms that result in a material and immaterial ‘dehumanization’ and this also effects of the degree to which a worker will resist or accept subjugation. Resolving slave labour, it follows, requires a deeper interrogation of these broader social relations and the extent to which the rescue and re-insertion of workers into labour market connects to workers' aspirations of dignity and liberty. The ambition to imagine less paternal politics of ‘rescue’ towards more horizontal formation brings us to contemporary considerations of solidarity.

Solidarity

Slave labour suggests the absence, erosion of, or potential for solidarity (McGrath, Citation2013; Neergaard, Citation2015). Solidarity, however, is most often employed as a rhetorical and normative resource (Laitinen & Pessi, Citation2014), suggesting that further interrogation of its conceptual value is required (Althammer, Citation2019; Khoo, Citation2015).

Bayertz (Citation1995, p. 295), recognizes that the material realization of a particular form of solidarity in large parts of Europe- that of mutual, intra community obligations contained in the welfare state- was a result of social upheavals rather than political reasoning. That western moral and political philosophy remained largely detached from such struggles may explain the largely uncritical application of ‘solidarity’ within the literature, from individual obligations through to universal expectations of humanity (Laitinen & Pessi, Citation2014). Between these poles Scholz (Citation2015) finds a consistent, if tenuous thread in the incorporation of duties or commitments mediated between individuals and the community, while concern or empathy with those being denied these entitlements is integral (Scheler, Citation1970).

While Bayertz traced the ‘social upheavals and struggle’ from which solidarity materialized in the form of welfare, the resultant structures provide for a much more acquiescent (post war) ‘settlement’ consistent with a market-oriented political economy, in which individuals are considered as self-interested actors that come together in a mutual sense of cooperation or interdependence (Durkheim, Citation1984; Christopher, Citation2014). For Khoo (Citation2015) and Samson (Citation2019); however, the inherent and often fairly fixed social identities and their political representations result in social differentiation that constrains rather than facilitates a cooperative sense of solidarity across a broader community. The protection, or rescue of deserving ‘others’, individuals or victims may well be afforded (McGrath & Watson, Citation2018) but what, then, distinguishes the feelings and actions of solidarity from those of empathy, charity, benevolence or philanthropy towards apparently passive recipients (Freire, Citation1993; Harvey, Citation2007)? Is solidarity merely an outcome of liberal notions of justice for specific individuals?

If so, then solidarity runs into further trouble as it crosses borders. The institutionalization of solidarity between the global north and the global south, with its roots firmly in Western episteme, commonly and all too easily collapses into a ‘philanthrocapitalism’ (Chuang, Citation2015; Cole, Citation2012), and a liberal contractualism. Instead of challenging historically rooted injustice endogenous to the process of capital accumulation, the lack of knowledge, culture or capacity of non-white people are found at fault (Chuang, Citation2015; Cole, Citation2012; Roshanravan, Citation2018) and the market a reliable solution. Narratives of heroism, modernization and religious philanthropy underpin the rescue of ‘victims’ (Flaherty, Citation2017), often by authoritarian means, and remain effective in transforming slave labour into a moral or individual problem between ‘good people’ (the enslaved) and ‘evil people’ (the perpetrators) (McGrath & Watson, Citation2018).

For a liberation solidarity

Alternative readings of solidarity, however, emphasize the structural preconditions for its necessity (Lowy, Citation1988; Pickford, Citation2019), the subjective agency of the oppressed towards social change (Fanon, Citation1986; Freire, Citation1993; Mohanty, Citation2003), and emerge from geographies and histories that jar with its occidental construction (Dussel, Citation2003). Deeply racialized and gendered social divisions mark historical domination and an absence of solidarity to colonial subjects who were subject to the paradox of non-being (Fanon, Citation1986; Gordon, Citation2018). Women, migrants, and black communities were not only silenced and rendered invisible in their everyday struggles but also excluded from the right to escape from such reality (Distiller & Samuelson, Citation2005). The ‘false universalizing and masculinist assumptions’ of Eurocentricism have been challenged by those rejecting its assimilating claims and colonial legacies (Mohanty, Citation2003, p. 516), yet keen to avoid deepening societal divisions that have been a feature of contemporary capitalism (De Lissovoy, Citation2010) and instead progress a common, ethical project of solidarity (Dei, Citation2000; Maldonado-Torres, Citation2012).

Mance (Citation2011, p. 8) recognizes solidarity in the collaborative and horizontal processes of liberation: a ‘phenomena of inter subjectivity and of historical transformation of concrete relations’. In doing so Dussel’s (Citation2003) distinction between the European enlightenment principle of emancipation, (as articulated by Hegel, Weber and Haberman), and the idea and practice of liberation is evoked (Christopher, Citation2014). Philosophies of liberation linked to paradigms of solidarity for social transformation (Maldonado-Torres, Citation2012) most commonly take the subjectivity of the historically oppressed as a starting point (Dei, Citation2000; Dussel, Citation2003; Fanon, Citation1986) and emphasize the alternative or subaltern knowledge produced in and through anti-colonial or decolonial struggles (Mignolo, Citation2009; Sousa Santos, Citation2018; Maldonado-Torres, Citation2012). The oppressed are recognized as an historical subject in the construction of ethical, committed solidarity that, as Pickford (Citation2019, p. 137) notes, Karl Marx states is negated under capitalism:

Marx’s account of capitalism as an obstruction to the actualization of solidarity qua social production. (…) Under capitalist production for exchange the essential unity (solidum) of this life activity, involving both producer and consumer, is systematically destroyed, as social production disintegrates into mutually indifferent discrete acts of producing-for-oneself.

In Latin America this recognition was reflected in the emergence of Liberation Theology in the 1960s, its embrace by radical wing of the Catholic Church and subsequent writings from the subject in the 1970s (Boff, Citation1987; Gutierrez, Citation1974). The value laden and political choice to side with the oppressed in ‘solidarity with their struggle for self-liberation’ (Lowy, Citation1988) was explicitly attentive to the capitalist structures and processes of unfreedom in the present and past and the limits of solidarity under Western philosophical and politico-judicial formations (Mbembe, Citation2006). A liberatory solidarity, it is posited here, is cognizant of the contemporary structures and processes under neoliberal globalization that have deepened inequality and constrained indigenous communities and workers' collective power to define the terms of their own freedom. It points to a commitment to a solidarity that rejects certain relations, such as those with colonial and patriarchal resonance, for an expansive (Altuna-Gabilondo, Citation2013) interconnectedness (Jaramillo & Carreon, Citation2014; Maldonado-Torres, Citation2012), that acknowledges difference but identifies and reinvisions forms of collective resistance (Roshanravan, Citation2018) and a reparation of dignified social production.

For the purpose of this paper then, this class based analysis of solidarity and its relevance to the subjective experiences of internal rural migrants is contrasted with the limits to state and philanthropic approaches to slave labour amongst more recently arrived immigrants to Mato Grosso, Brazil. In the following section the experiences of these workers are placed in the context of shifting capital-labour relations at the turn of the century that have a pronounced territorial character.

Brazil in context

The relationship between land access, slave labour and economic development is rooted in Brazil’s history. Brazil is among the globe’s ten largest economies, the fifth largest country in terms of land area and one of the most biodiverse and resource-rich in the world. The economic dependence on the slavery system made Brazil the last country in the western hemisphere to constitutionally abolish legal slavery in 1888. This workforce was composed fundamentally of African workers who were enslaved for over three hundred years to work in plantations during colonialism and after Brazil's independence in 1822. In the early twentieth century, the end of legal slavery transitioned into forms of structural racism and unequal access to land, shaped by racial whitening and other state polices that equates modernization, progress and development to a commodity driven economic growth (Fernandes, Citation2008). Rapid urbanization, forced displacement of rural communities, cheap labour, high concentrations of land ownership and agricultural intensification sustained slave labour and elitist models for economic growth in the country from military import substitution strategies (1964–1985) (Martins, Citation1997), through to the neoliberal policy agenda of the 1990s. In the latter period, however, efforts to ‘modernize’ by attracting foreign investment and rebuilding certain civic rights after four decades of dictatorship did not address the roots of class inequality that peaked in 1995. Instead, the expansion of agribusiness and infrastructure projects has been a major cause of displacement and dispossession of rural communities, including indigenous people and quilombola communities.

In the 1990s, Brazil did, however, officially acknowledge the existence of slave labour in its economy and the definition of slave-like labour has been acknowledged internationally as of great commitment to antislavery (OIT, Citation2011). In article 149 of the Brazilian Criminal Code, the concept of ‘work analogous to slavery’ or slave-like labour expands conventional definitions of slave labour by recognizing that it refers not only to the absence of worker's liberty but also of his/her dignity. The creation and the strengthening of labour inspection and of national programmes for Eradication of slavery has since been one of the main pillars to implement this legislation. The expanding inequality and processes of deregulation in the neoliberal context, however, has limited the percolation of the antislavery system through the layers of society and created conditions for further social vulnerability among the working class, including the increased mobility of labour across national borders and persisting gender and racial inequalities (Figueira, Citation2004; MTE, Citation2018).

During the class conciliation experiment of the Workers Party (2003–2016), a period of impressive economic growth was linked to the commodities boom and public investments. There were notable social achievements and the rapid expansion of the construction sector, to which many newly arrived immigrants were recruited (Portes Virginio et al., Citation2022). Over 100,000 new immigrants arrived in the country during this period. These consisted of Bolivians, Senegalese, Colombians, Angolese, Syrian, but mainly Haitians and Venezuelans. This number of immigrants has since increased in each subsequent year up to 300,000 in 2019 due to the Humanitarian migration crisis from Venezuela. These workers have been granted a visa and permission to work (Cavalcanti et al., Citation2021).

Despite being important for the populist rhetoric of job creation and dynamics of consumption in the domestic market, these sectors where most of domestic and international markets were concentrated had higher turnover rates, higher incidence of violations and offered wages below the amount necessary for the social reproduction of these workers (Portes Virginio et al., Citation2022).

A long-standing economic crisis and distinct authoritarian turn by the Brazilian government that swept through changes to no less than 120 labour law articles since 2017, however, has revealed the limitations to the previous neodevelopment project. It was amongst an increasing militarization of government’s agencies, increasing labour unemployment and precarity, and emerging cases of re-enslavement among ‘rescued workers’ in agribusiness and infrastructure projects that this research was carried out in Mato Grosso, a state central to commodity expansion.

Methods

Primary data was collected on two discrete periods between March 2019 and December 2019. In the first place, 40 semi-structured interviews were conducted with 27 male and 13 female workers, both domestic and international migrant participants, who had participated in official programmes to combat slavery following rescue, that is, participants who received for three months unemployment allowance or attended training courses on workers' rights and professional qualifications. Field visits, ethnographic observation, and collective discussions in workshops and focus groups were held in emergency shelters, sites of accommodation and in the two agrarian settlement communities of Novo Mundo and Chumbo, where workers were since located. Workers were asked about their life stories, living conditions and experiences of work, family, community, and rescue as well as about the situations in which they experienced help, aid and solidarity prior to and after their identification as workers subject to slave-like labour. They were also asked about their understanding of key problems and possible ways to address their exploitation and oppression. The second stage of fieldwork focused on institutional approaches to slave labour. Interviews with Public Prosecutors and Labour Inspectors, and activists with civil society organization, Pastoral Centre for Migrants, Pastoral Land Commission (CPT) were conducted. Participants were asked about main mechanisms, strategies and challenges to combat to slave-like labour in Mato Grosso and their individual motivations to be part of this programme. Finally, secondary data was collected from official sources such as programmes to eradicate slave labour, demographic, immigration, labour market and antislavery indicators.

The study received ethical approval from The Ethics Committee of University of Strathclyde in the United Kingdom and in the Federal University of Mato Grosso in Brazil. Participants were anonymized and provided with aliases for the purpose of this paper.

Post-rescue and circuits of unfreedom

In Brazil, the notion of ‘rescue’ focuses on workers that are deprived of liberty and dignity through degrading working conditions; excessive working hours; in conditions of forced labour; or in situations whereby their freedom is restricted through debt, isolation, the confiscation of their personal documents or by maintaining manifest surveillance (Figueira, Citation2004).

The slave labour as experienced by ‘rescued workers’ interviewed for this paper; however, invites an exit from the conceptual vice grip of this liberal framework: it is not the exception that characterizes their experiences in Mato Grosso. Rather, the testimonies point to the broader structural coercion in Brazil’s neoliberal economy which perpetuate patterns of displacement, dispossession and slave labour. While interpersonal relations between employer, intermediaries and employees are not unimportant, precarious work, escalating unemployment, asymmetrical power relations, retraction of labour protections and diminishing access to the commons are producing conditions for slave labour with distinct spatial signatures.

Following (neo)liberal accounts of freedom in which the market is ascendant, workers are ‘at liberty’ to engage in productive and socially reproductive activities. On record, then, Mato Grosso would appear an ideal destination to practice this economically defined freedom. The state has experienced the highest economic growth out of all the 27 Brazilian states, accounting for an average GDP growth of 5.5%, in comparison to the national average growth rate of 2.5% since 2002 (IBGE, Citation2019). The agribusiness sector constitutes 21% of local GDP and sustains directly related services that account for a further 47% of the GDP of Mato Grosso (IBGE, Citation2019) including a fast-growing civil construction that provides a needed infrastructure for the commodity corridors in the region. This contributes to the lowest unemployment rate (9.1%) of all the central and northern states in Brazil.

On closer inspection, however, the reduction in the unemployment rate in Mato Grosso belies the 36.1% of occupied workers who are in the informal employment sector while a further 16.5% of these workers are unable to work the statutory forty working hours (IBGE, Citation2019). Furthermore, Mato Grosso is responsible for the highest rate of dismissals and new hires in the whole country, leading with an annual turnover of 67% of the workforce in comparison to the national average rate of 50% over the century (DIEESE, Citation2017).

Mato Grosso presents the third-highest number of workers rescued from slave labour in Brazil. Between 2003 and 2019, approximately 50,000 cases Footnote1were identified in these conditions in Brazil, and Mato Grosso corresponds to around 6088 of these relatively well publicized rescue operations (MPT & OIT, Citation2021). Below we consider the experiences of immigrant and internal migrant workers who are a feature of these statistics in Mato Grosso.

In the absence of the broader state reforms required for social protection, a concerted action between military forces and philanthropic organizations in border regions is shaping the employment routes of immigrants in the past decade. The geographical relocation of immigrants from northern Brazil to regions with lower unemployment rates is current state policy for humanitarian protection (Operação Acolhida, Citation2021; Portes Virginio & I-migra, Citation2022) and explains a renewed competition for jobs in Mato Grosso as explained by the nineteen year old, Javier, a refugee from Venezuela who was encountered alongside other 10 immigrants in the antislavery programme in Mato GrossoFootnote2:

If I say that I will charge just 30 reais [for a day of work] they would say [the employers] ‘no leave it, later will come someone else and they accept to work for 20 reais to do the same thing’. So I always took the job because I needed it. I had to take care of daughter, my mom and my brother.

The situation for immigrants like him, who have permission to work but a dearth of broader social rights (Portes Virginio et al., Citation2022) is further complicated by the relationship rescued workers have with faith-based organizations who are the point of contact for immigrants relocated by the state from other parts of the country. While providing often much needed, and voluntary, emergency assistance, the role of faith-based groups in responding to with slave labour cannot be easily divorced from the conflicted role of religious groups with the military dictatorship (1964–1985), when unions and social movements faced prohibition. Conventional faith groups often operated in enduring quasi-formal coordination with the state, filling gaps in statutory social protection, providing basic assistance and shelter, and often acting as labour intermediaries.Footnote3 In stark contrast to the advocacy and often militant resistance to slave labour in Brazil’s fields that is outlined later, a discernible, paternal philanthropism of assistance and alleviation extends to an incorporation of the needy into the labour market- not necessarily as distinct from personal salvation. The experience of Jaques Rouge, a Haitian worker who was rescued alongside fifteen other Haitian workers from a construction site in a job, illustrates the risk involved. He was sourced for the job via the local-faith based organization where the migrants received shelter upon their arrival in Brazil and were undertaken in relatively close proximity to the capital city, Cuiabá.

Problems soon began, as Jaques explains. Their employer resisted formalizing their employment relations for over a month and also controlled access to accommodation and payment. On evidence the faith-based intermediaries had neither the capacity nor legal means to monitor and enforce protection and these workers struggled for months before any labour inspection was completed. The rescue was initiated, Jaques understood, from a woman in the street who had met the workers asking for food as they were suffering from hunger and without access to sanitation. However, following the rescue, Jaques is the only one out of the fifteen rescued workers that remains in Mato Grosso as the others fled due to lack of local opportunity. Some six years on this experience is manifested in an occupational illness that has compromized his ability to walk and work for the foreseeable future. Although he received disability benefits for seven months following rescue, this was cancelled after a short period due to cuts in state expenditure in Brazil. He has been unemployed since and has little means to support a wife and two children. They experience hunger and he has been attempting to reverse the decision from the state in order to recover his benefits. He fears going to court against his former employer as losing the case would require him to pay R$ 11000 reais for his employer's expenses during trial, a new requirement that means a further setback for the eradication of slave-like labour in Brazil that is further explored in the next section.

Slave labour and land

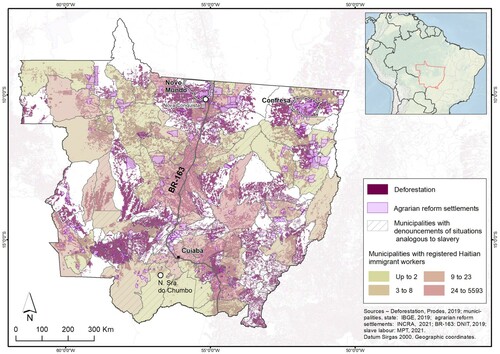

While the ongoing precarization of employment through a raft of changes to labour lawFootnote4 points towards a new deepening of slave labour, the related structures of employment are embedded in a wider colonial legacy in the country. Mato Grosso also boasts the second greatest concentration of land in Brazil, with approximately 67% of its territory being privately owned latifundium of over 3,500 hectares (IBGE, Citation2019). The effects for labour have been two fold. Firstly, a fragile system of social protection accompanied by the adoption of mechanized production of monocultures increases the competition for the remaining jobs between workers who are predominantly engaged in very precarious conditions and seasonal work. Secondly, in the view of a Superintendent for the Programme to Eradicate Slave Labour in Mato Grosso, the expanding soya, maize and sugar cane complexes force the land clearing and cattle rearing activities, often through illegal means, which are synonymous with slave labour (). Illegal logging, forest clearance and land grabbing are precursors to the expansion of agricultural lands and, as a co-ordinator of the CPT’s Campaign against slave labour can say with some authority, ‘it is impossible to have illegal logging without slave labour […] the criminal activity can only be carried out of it is invisible[…] it must use slave labour, zero infrastructure, zero trail’ (Torres & Branford, Citation2018, p. 148; italics added).

Figure 1. Map of Mato Grosso state indicating (i) the study field sites; (ii) areas of deforestation; (iii) agrarian reform settlements; (iv) municipalities with Registered Haitian workers; and (v) with official denouncements of slave labour. (Credit: Professor Mauricio Torres)

These occur in more distant lands, geographically remote from urban administrative offices including those to combat slave labour. The municipality of Confresa to the northeast of the state had the highest number of workers rescued from slave like conditions in Brazil between 2003 and 2018 (MTE Citation2018) and also prone to ‘flagrant’ illegal deforestation (Suzuki & Casteli, Citation2021). There is also direct link to the reproduction of forced displacement and dispossession of indigenous peoples and African slave-descendent, quilombola communities who are constitutionally entitled to land rights as observed in the community of Nossa Senhora Aparecida de Chumbo, in Pocone. The region accounts for the second highest number of rescued workers in the state of Mato Grosso in the last 25 years (421). These were quilombola workers from the community, as well as migrants from the northeast of Brazil. All of them were working in the sugarcane supply chain. Due to labour inspections and the fines received, the company declared bankruptcy. The legacy of the slave labour relations; however, was vividly illustrated by the indignation of Maria CandidoFootnote5, a Brazilian worker, following her rescue:

It is a steal! […] in addition to stealing your money, your health, your time, your self-love, which ends up also going together, there goes your self-love, your self-esteem, everything goes together, it's a package!

What the state offers, the state taketh away

After two decades of the rescue system, Brazil has revealed to what extent its institutional approach to slavery percolates through ongoing class inequality. This reality is most easily expressed in the reoccurrence of slave labour whereby previously rescued workers figure prominently among new cases. This includes workers that were rescued up to four times from slave-like labour between 2003 and 2017 (MTE, Citation2018). Institutional recognition of this is reflected in official programmes that have invested in preventive measures (Suzuki & Casteli, Citation2021), legal reforms and concerted actions with public and private partners such as the so-called Ação Integrada (Integrated Action) Project (2009). It was elaborated in partnership with Public Ministry of Labour, the Federal University of Mato Grosso, and Regional Labour and Employment Superintendence. It aims to offer training to rescued workers, the majority of whom are illiterate or of low educational achievement (MTE, Citation2018). Workers receive temporary accommodation and income for workers for three months while receiving training about their legal rights and professional skills for jobs that are in demand, especially for positions in the agribusiness and civil construction sectors. Between 2009 and 2015, 1,828 workers received this training in Mato Grosso, including 547 rescued workers and 1,281 considered as workers vulnerable to exploitation.

As workers, through this programme, reveal their experiences, assumptions of a lack of knowledge or skills for the job market as a route to slavery is challenged. Jackson Bacourt, a Haitian citizen was one of seven other immigrants, who joined the programme and thus received qualifications for working as bricklayers and assembler assistants in civil construction. Jackson holds a law degree and used to work as a lawyer and teacher in Haiti but his professional skills were not validated in Brazil. He has been in Brazil for one and a half years and could only find temporary jobs in the civil construction sector. The programme, for him, meant an opportunity to learn about Brazil, and for the first time in the country, to receive the minimum wage three months in a row.

While the state provides a more marketized focus to mitigate the reoccurrence of slave labour, the proliferation of flexible forms of employment and the lack of cooperation with slave labour prosecutors in the justice system (Haddad et al., Citation2020) further contributes to this outcome. Only a small percentage of cases in Brazil goes to court as the vast majority find extra-judicial resolution with the payment of Adjustment of Conduct (TAC).

While these strategies may be limited in relation to worker emancipation, they have troubled some of Brazil's largest employers, especially in agribusiness and civil construction whose scale of production made their violations particularly visible to labour inspectors. The suspension of production for guilty parties and potential sanctions that can prevent access public subsidies and the confiscation of assets9 have been met with resistance from big business who, at least with regard to slave labour, have their champion in the far-right president Bolsonaro (2019–2022). One of his first actions in office was keeping his campaign promise to extinguish the Ministry of Labour. Labour inspections have since suffered from budget cuts, a stark reduction in personnel and restrictive legislation. The reduction of the teams (from eight to four) in Brasilia to combat slave-like labour and the refusal of the president in office to open civil service exams to hire new labour inspectors exacerbates the situation. According to one regional superintendent for slave labour, approximately 1300 public agents working on the programme to combat slave labour (almost one third of the total), retired between 2019 and 2021 and were not replaced. These changes have reduced, by almost 60%, the number of rescue operations in the past three years. In a political climate hostile to pursuit of labour justice, there have been attempts to withdraw the dirty listFootnote6 of offending employers of slave labour, while inspectors have encountered armed guards at the doorways of properties preventing their free entry that is otherwise guaranteed in law.

The re-emergence of this authoritarian rule has aggravated the unresolved class issues shaping slave labour in Brazil. This is highlighted in the testimony of Eduardo, who spent five years of his employment (from the age of 12–17) in a makeshift camp in a large farm to the north of the state. He fled his job owing to mistreatment and the withholding of wages. He was forced to return due to threats of violence to he and his family received from the local intermediary that employed him. Not long after his return there was an operation that freed more than one hundred from slave work, and insisted that the other workers directly employed in the farm were properly registered. Tellingly, while those directly employed on the farm (that was subject to a fine of more than R$1 million) retained their jobs, those who were rescued were unable to find work on any farm in that region of the state, such is the power of the landowners. The workers received a modest compensation for their treatment, but believe they are on a blacklist to this day. Unable to find agricultural work, Eduardo bought a hot dog van with his compensation money that was then stolen from him, found a job in a meat processing factory where he became mentally unwell, before eventually finding a more benevolent employer who provided him with technical training. Eduardo remains in regular contact with friends still in employment in the farm, but separated by 700 km and the outcome of the legal process that distinguished between the free and unfree.

The lucid accounts of rescued workers such as Eduardo, Maria Candido and Jaques point to the institutional achievement of rescue, but also a continuum of slave labour in Mato Grosso within the broader organization and expansion of capitalism and elitist power relations that are not challenged through individual liberation or technical upskilling, nor assuaged by workers consciousness of injustice. How to connect their experiences and knowledge to more common struggles for justice and what this might mean for confronting slave labour is the focus of the final section.

Solidarities between productive and reproductive struggles

As more workers were rescued, more others [cases of slavery] appeared, the rescue in itself is not a combat against slave labour, it is just an emergency combat against the immediate.

Marcos Silva, CPT agent

In Brazil, social movements have been central to the conception and articulation of a class based-understanding of slave labour. With Peasant Leagues and non-co-opted unions driven underground during the military dictatorship in Brazil (1964–1985), the solidarity with the poor and oppressed as articulated by Latin American liberation theology wielded substantial and enduring influence. In a radical departure from incumbent charitable and patriarchal religious practice that had been co-opted by the military, and inspired by visible third world struggles, the proponents denounced the ‘structural sin of class oppression’ and focused on the liberating power of the poor, emphasizing their role as active subjects or ‘people of God’ and recognizing popular wisdom. Therefore, its methodology was guided by political love in solidarity and long-term commitment to the marginalized (Gutierrez, Citation1974; Sobrino, Citation1992).

The Pastoral Commission of Land (CPT) offers one of the most striking examples in which liberation theology is materialized on an ecumenical basis for anti-slavery struggles in Brazil. Since the 1980s, the CPT has been the main drive force of antislavery, denouncing over 165,000 cases of slave labour, and indeed its consistency was fundamental to the state acknowledging the problem in 1995, following the restoration of democracy (Leão & Ribeiro, Citation2021). From 1995 to 2020, the CPT filled around 1,600 complaints of slave labour so that two out of five formal denouncements of slave labour in Mato Grosso originated from CPT (CPT, 2019). The Labour Inspector in Cuiaba explained the fact by the very presence of the church in the remote localities of the agricultural frontier where the state has little visibility. Significantly, these denouncements are part of the broader support to rural workers for land and dignity. Land is a key source of conflict and of slave labour in Mato Grosso and gaining access to land is also the key aspiration of approximately 60% of ‘rescued workers’ (OIT, Citation2011) as the means to realize rights, family, work and community. This multidimensional struggle moves the debate beyond the confines of immediate wage-labour exploitation to instead focus on the entrenchment of economic and extraeconomic forces that constrains workers' freedom as highlighted by Francisco, a CPT leader:

It is not enough to rescue [someone] from slave labour to eradicate slavery … Slavery is a system that has very deep roots, is embedded in our social relations, in our history of exploitation and of racial discrimination; in our economic model, it is the residue or the remnant of that archaic ideology of those who are unable to see others as their equals.

Hence, these actions to illuminate slave labour cases have been central to the formation, institutionalization and relative success of the antislavery system in Brazil. Running parallel, and horizontal to the state operations, however, are sustained struggles of the CPT with rural workers whose resistance to slave labour is tied to new social constructions via land occupation and agrarian reform. It is common to hear rural workers determined to resist the wage-slave labour relations by being their own food producers (Medeiros & Garvey, Citation2021), but these ambitions are increasingly constrained by adverse public policy and the encroachment of agribusiness on common land.

In Mato Grosso’s agroindustrial belt, arguably the most technically advanced in the country, over 100,000 landless families are involved in land conflicts, with migrant workers, traditional communities, and descendants of enslaved African workers disproportionately represented. Here the case of the Nova Conquista community is emblematic. The vast majority of the 96 families of the communities had experienced human rights violations that were subject to judicial processes. Their community exists, after a hard-fought struggle and occupation, on land that had been previously and fraudulently claimed by a notorious farmer responsible for the slave-like labour of 136 people in 2003.Footnote7

The ideological and political commitment by the CPT, who continue to work closely with the community, involves recognition of their shared subjective experience and knowledge – and aspirations that are acutely opposed to engagement in salaried labour of the nature being offered by agribusiness.

Their collective articulation contrasts with the experiences of immigrant workers faced with transnational family relations (Portes Virginio et al., Citation2022), legal restrictions on migratory statusFootnote8 that have been only recently relaxed, and racialized social divisions that have limited their legal participation in collective associations and protests.

In Mato Grosso, however, a growing frustration with this reality has seeded the increasing presence of immigrants in urban occupations, agrarian reform settlements and new community association with implications for the struggle against slave labour.

Conclusion

The paper emphasized liberatory solidarity as a vital element in the struggle to eradicate slave labour in Mato Grosso, Brazil in place of incumbent liberal approaches (the latter currently being undermined under authoritarian government). The liberal model was explored in relation to monitoring, individual rescue, and technical upskilling that have existed alongside neoliberal reforms and economic growth. Through the prism of the experiences of ‘rescued’ workers, the paper links the persistence of slave labour to the historical reproduction of asymmetrical power relations, neoliberal social conditions for labour exploitation and agricultural expansion in Mato Grosso.

Despite the implementation of antislavery programmes with relative success in the past decade, the verticalisation of their operation and the liberal basis of these initiatives have limited the durability of the actions in Mato Grosso. This limited the scope of the monitoring role and its connection with the aspirations of workers for justice, while the lack of broader social protection, long-term commitment and stiffer penalties against slave labour offered employers continuous access to large pools of cheap labour through precarization of employment arrangements and labour intermediaries. Moreover, the concomitant rise of displacement and dispossession caused by the same large-scale agricultural investments showed that labour is also constrained in its reproduction and lack of freedom to begin with (Banaji, Citation2003; Fernandes, Citation2008).

While the liberal approach frames slave labour as an exception in the employment relationship and posits legal justice as an ethical outcome to remediate the issue, the prolonged history of labour subordination and recurrence of slave labour reveal an epistemic misrecognition (Fanon, Citation1986; Mohanty, Citation2003) of a multidimensional struggle of workers that remains unaddressed in Mato Grosso. In this sense, in this agroindustrial powerhouse, colonial legacies of high land concentration, commodity–centred production, precarious employment arrangements, paternalism and racial discrimination continue to provide conditions for slave labour, against which the local nature of law making and individualized rescue reflect rather than challenge prevailing class relations. The dismantling of preventative and rescue measures through budget cuts and roll back of legal protection under the alliance between an authoritarian government and large-scale agricultural powers sheds light on the need for tackling systemic causes of slave labour.

A liberatory solidarity inspired by material class based struggles dating to the 1960s offered a localized and contextualized pathway to combat slave labour: it demands more than a transition from a state of ‘expropriated to exploited’, ‘from non-free labour’ to ‘free wage labour’ if slave labour is to be eradicated. The aspirations, subjective knowledge base and collective practices of land occupations involving rural workers in opposition to slave and wage labour also depict the limits available to other workers; for example, immigrants faced by contemporary forms of saviourism and transnational patterns of social reproduction (Portes Virginio et al., Citation2022). The multitude of social forces structuring slave labour are pervasive and systemic. Solidarity cannot, therefore, be understood in a consensual, reactive or essentialist way. Solidarity must engage with the epistemic insight of unfree workers in defining the terms of their freedom and autonomy, tracing roots of class oppression and unfreedom in their particular and differentiated situations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the workers who shared their knowledge and experiences with them. They also thank editorial team and the anonymous reviewers for careful reading and insightful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Francis Portes Virginio

Francis Portes Virginio is a Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow working on his project ‘the Securitisation of Nature, Displacement and Unfree Labour in Brazil's Amazon’. He is currently based at the department of Work, Employment and Organisation in the University of Strathclyde. His research interests focus on the migration-development nexus, global commodity chains and degrading conditions of employment with a particular focus in Latin America. His current work examines the experiences of unfree labour and forced displacement in the Brazilian Amazonian region. He is co-founder of the Research Centre for the Political Economy of Labour (CPEL).

Brian Garvey

Brian Garvey is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Work, Employment and Organisation, University of Strathclyde. His current research focus relates primary commodity chains, labour organisation and rural conflicts in the northern and southern hemisphere. He is currently Principal Investigator for the ESRC project, ‘So who IS Building Sustainable Development’ with partners in Brazil and France, and co–founder of the Research Centre for the Political Economy of Labour.

Luís Henrique da Costa Leão

Luís Henrique da Costa Leão is Professor of Collective Health at Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT), researcher in the Group of Studies and Research on Environmental and Workeŕs Health (GEAST-UFMT) and Group of Research Contemporary Slave Labour (GPTEC) from Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. He was a visiting fellow at Visiting University of Padova, Italy and University of Nottingham, United Kingdom (2019).

Bianca Vasquez Pistório

Bianca Vasques Pistório is a PhD candidate at the Department of Work, Employment and Organisation at the University of Strathclyde.

Notes

1 Black workers account for 82% and women for 5% of rescued workers in Brazil, which mirrors trends in Mato Grosso. This gender imbalance is explained by the inability of rescue operations to rescue workers in jobs disproportionally occupied by women such as domestic work and sex work (Reporter Brasil, Citation2020).

2 Integrated Action Programme which will be explained in the next section.

3 Although labour intermediation should be a public policy in Brazil (ILO, Convention n° 88), the state has allowed private actors to intermediate labour without specific legislation to regulate this practice. Recent changes to outsourcing law and militarisation of immigration hotspots (Portes Virginio & Imigra, Citation2022) have further weakened this previous obligation.

4 For instance, the Laws 13.429/17, 13.467/17, 13.874/2019.

5 (Interviewee). in the community Chumbo, Poconé-MT

6 The dirty list is a registration that publicly names and shames companies that the Labour Inspection Secretariat has identified as using slave labour. The inclusion in the list also constrains access to public financing.

7 Despite the hollowing out of agrarian reform in practice under the current administration the existing constitutional article (Article 185, item II/1988) discerns that, in principle, land that is unproductive, illegally claimed, or not fulfilling its socio-environmental function, can be designated for agrarian reform by the state. Land occupations, such as that of Nova Conquista, demonstrate the need by rural workers for land and pressure the authorities to reallocate unproductive or illegally grabbed land. Successful occupations result in formalised rural settlements with approximately 6 hectares per family.

8 Brazilian Foreigner Statute (1980) – act No. 6815/80 replaced by L13445/2017

References

- Althammer, J. (2019). Solidarity: From small communities to global societies. Solidarity in Open Societies, 1(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-23641-0_2

- Altuna-Gabilondo, L. (2013). Solidarity at work: The case of Mondragon. UNRISD Think Piece.

- Bales, K. (2005). Understanding global slavery. University of California Press.

- Banaji, J. (2003). The fictions of free labour: Contract, coercion, and so-called unfreelabour. Historical Materialism, 11(3), 69–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/156920603770678319

- Bayertz, K. (1995). Solidarity. Kluwer.

- Berry, D. R. (2017). The price for their pound of flesh: The value of the enslaved, from womb to grave, in the building of a nation. Beacon Press.

- Boff, L. (1987). An introduction to liberation theology. Orbis Books.

- Brass, T. (2010). Unfree labour as primitive accumulation? Capital and Class, 35(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309816810392969

- Breman, J. (1994). Wage hunters and gatherers: Search for work in the urban and rural Economy of South gujarat. Oxford University Press.

- Cavalcanti, L., Oliveira, T., & Silva, B. R. A. (2021). Uma década de desafios para a imigração e o refúgio no Brasil. Série Migrações. Observatório das Migrações Internacionais; Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública/ Conselho Nacional de Imigração e Coordenação Geral de Imigração Laboral. OBMigra.

- Christopher, J. L. (2014). Decoloniality of a special type: Solidarity and its potential meanings in South African literature, during and after the Cold War. Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 50(4), 466–477. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17449855.2014.925705

- Chuang, J. (2015). The challenges and perils of reframing trafficking as ‘modern-day slavery’. Anti-Trafficking Review, 5, 146–149. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121559

- Cole, T. (2012). The white-savior industrial complex. The Atlantic, 21(March). https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/03/the-white-savior-industrial-complex/254843/

- Davidson, J. O. C. (2015). Modern slavery: The margins of freedom. Springer.

- De Lissovoy, N. (2010). Decolonial pedagogy and the ethics of the global. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 31(3), 279–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01596301003786886

- Dei, G. J. S. (2000). African development: The relevance and implications of ‘indigenousness’. Indigenous Knowledges in Global Contexts: Multiple Readings of our World, 1(1), 70–86.

- DIEESE. (2017). https://www.dieese.org.br/

- Distiller, N., & Samuelson, M. (2005). Denying the coloured mother": gender and race in South Africa. L'Homme, 16(2), 28–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7767/lhomme.2005.16.2.28

- Durkheim, E. (1984). The division of labour in society. Macmillan

- Dussel, E. (2003). Philosophy of liberation. Wipf and Stock Publishers.

- Dussel, E. D. (1977). Introducción a una filosofía de la liberación latinoamericana (Vol. 4). Extemporáneos.

- Fanon, F. (1986). Black skin, white masks (C. Lam Markmann, Trans.) Pluto. (Original work published 1952).

- Fernandes, F. (2008). A integração do Negro na sociedade de classes: No limiar de uma nova era. Globo livros.

- Figueira, R. (2004). Pisando fora da própria sombra: a escravidão por dívida no Brasil contemporâneo. Civilização Brasileira.

- Flaherty, J. (2017). No more heroes: Grassroots challenges to the savior mentality. Ak Press.

- Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogía de la esperanza: un reencuentro con la pedagogía del oprimido. Siglo xxi.

- Gordon, T. (2018). Capitalism, neoliberalism, and unfree labour. Critical Sociology, 45(6), 921–939. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920518763936

- Gutierrez, G. (1974). Theologie de la liberation. Lumen Vitae.

- Haddad, C. H., Miraglia, L., L, M., & Da Silva, B. F. (2020). Trabalho Escravo na Balança da Justiça. IEPEL.

- Harvey, J. (2007). Moral solidarity and empathetic understanding: The moral value and scope of the relationship. Journal of Social Philosophy, 38(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9833.2007.00364.x

- IBGE. (2019). Pesquisa Nacional Por Amostra de Domicílios. Retrieved 8 December, 2020, from https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/trabalho/17270-pnad-continua.html?=&t=o-que-e

- Jaramillo, N., & Carreon, M. (2014). Pedagogies of resistance and solidarity: Towards revolutionary and decolonial praxis. Interface: A Journal for and About Social Movements, 6(1), 392–411. http://www.interfacejournal.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Interface-6-1-Jaramillo-and-Carreon.pdf

- Khoo, S. M. (2015). Solidarity and the encapsulated and divided histories of health and human rights. Laws, 4(2), 272–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/laws4020272

- Laitinen, A., & Pessi, A. B. (2014). Solidarity: Theory and practice. Lexington Books.

- Leão, L. H. C., & Ribeiro, T. A. N. (2021). A vigilância popular do trabalho escravo contemporâneo. Physis, 31(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-73312021310125

- Lebaron, G., Howard, N., Thibos, C., & Kyritsis, P. (2018). Confronting root causes: Forced labour in global supply chains. OpenDemocracy, University of Sheffield.

- Lerche, J. (2011). The unfree labour category and unfree labour estimates: A continuum within low-end labour relations. Manchester Papers in Political Economy, Centre for the Study of Political Economy, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

- Linden, M. (2013). Trabalhadores do mundo. Ensaios para uma história global do trabalho. Ed. Unicamp.

- Lowy, M. (1988). Marxism and Liberation Theology. Notes for study and research, No. 10. International Institute/or Research and Education.

- Maldonado-Torres, N. (2012). Decoloniality at large: Towards a Trans-Americas and Global Transmodern Paradigm. Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World, 1(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5070/T413012876

- Mance, E. (2011). Solidarity Economy. http://solidarius.com.br/mance/biblioteca/solidarity_economy.pdf

- Marcuse, H. (1973). A ideologia da sociedade industrial. O homem unidimensional. Zahar.

- Martins, J. (1997). The reappearance of slavery and the reproduction of capital on the Brazilian frontier. In T. Brass, & M. van der (Eds.), Free and unfree labour: The debate continues (pp. 281–303). Peter Lang.

- Mbembe, A. (2006). Nécropolitique. Raisons Politiques, 1(1), 29–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3917/rai.021.0029

- McGrath, S. (2013). Many chains to break: The multi-dimensional concept of slave labour in Brazil. Antipode, 45(4), 1005–1028. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01024.x

- McGrath, S., & Watson, S. (2018). Anti-slavery as development: A global politics of rescue. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 93, 22–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.04.013

- Medeiros, J., & Garvey, B. (2021). Expansão do dendê e os quilombolas do Alto Acará, Pará. In D. Stefano, B. Garvey, & F. Portes Virginio (Eds.), Amazônia em fluxo: Tensões, território e trabalho (pp. 33–44). Outras Expressões.

- Mignolo, W. D. (2009). Epistemic disobedience, independent thought and decolonial freedom. Theory, Culture & Society, 26(7-8), 159–181.

- Mohanty, C. T. (2003). “Under western eyes” revisited: Feminist solidarity through anticapitalist struggles. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28(2), 499–535. Under Western Eyes”. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/342914

- MPT & OIT. (2021). Plataforma SmartLab. Brasil. www.smartlabbr.org/trabalhoescravo.

- MTE. (2018). Ministery of Labour and Employment. Public Data. Brasília. Brasil. www.mte.gov.br

- Neergaard, A. (2015). Migration, racialization, and forms of unfree labour. In C-U Schierup, R. Munck, B.Likić-Brborić, & A. Neergard (Eds.), Migration, precarity, and global governance: Challenges and opportunities for labour (139–159). Oxford University Press.

- OIT. (2011). Perfil dos principais atores envolvidos no trabalho escravo rural no brasil. Organização Internacional do Trabalho.

- Operação Acolhida. (2021). https://www.gov.br/casacivil/pt-br/acolhida.

- Pickford, H. W. (2019). Anthropological solidarity in early Marx. In Jörg Althammer, et al. (Eds.), Solidarity in open societies (pp. 133–151). Springer VS.

- Portes Virginio, F and I-migra. (2022). Informalidade e proteção dos trabalhadores imigrantes: Navegando pelo humanitarismo, securitização e dignidade. 1st ed. São Paulo. Outras Expressões. https://www.politicaleconomyoflabour.org/pt-br/Articles/livro-informalidade-e-prote231227o-dos-trabalhadores-imigrantes-navegando-pelo-humanitarismo-securitiza231227o-e-dignidade

- Portes Virginio, F., Stewart, P., & Garvey, B. (2022). Unpacking super-exploitation in the 21st century: The struggles of Haitian workers in Brazil. Work, Employment and Society. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170211060748

- Rao, J. M. (1999). Agrarian power and unfree labour. Journal of Peasant Studies, 26(2-3), 242–262. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03066159908438708

- Reporter Brazil. (2020). Slave labor and gender: Who are the female workers enslaved in Brazil? / Natália Suzuki (ed.); “Slavery, no way” staff – São Paulo, 2020.

- Rioux, S., LeBaron, G., & Verovšek, P. J. (2020). Capitalism and unfree labor: A review of Marxist perspectives on modern slavery. Review of International Political Economy, 27(3), 709–731. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1650094

- Rodney, W. (2018). How Europe underdeveloped Africa. Verso Books.

- Roshanravan, S. (2018). Self-reflection and the coalitional praxis of (dis) integration. New Political Science, 40(1), 151–164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07393148.2017.1418545

- Samson, M. (2019). Trashing solidarity: The production of power and the challenges to organizing informal reclaimers. International Labour and Working-Class History, 95, 34–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0147547919000036

- Scheler, M. (1970). The nature of sympathy. Archon Books.

- Scholz, S. J. (2015). Seeking solidarity. Philosophy Compass, 10/10(10), 725–735. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12255

- Sobrino, J. (1992). Espiritualidade da libertação. Estrutura e conteúdos. Loyola.

- Sousa Santos, B. (2018). The end of the cognitive empire: The coming of age of epistemologies of the South. Duke University Press.

- Suzuki, N., & Casteli, T. (2021). O programa escravo, nem pensar no Mato Grosso: Uma experiência de prevenção em comunidades vulneráveis ao trabalho escravo. In L. H. C. Leão, & C. R. F. Leal (Eds.), Novos Caminhos para Erradicar o Trabalho Escravo Contemporâneo (1ed, pp. 71–96). Curitiba.

- Torres, M., & Branford, S. (2018). Amazon besieged: By dams, soya, agribusiness and land-grabbing. Practical Action Publishing.