ABSTRACT

Transboundary conservation is a strategy developed by international conservation organizations to safeguard biodiversity along and across borders and to enhance peace-building among nation-states and border communities. Currently, there are over 200 transboundary conservation cases worldwide, suggesting that the strategy is a significant yet under-researched area in International Relations. Based on empirical research and mapping, this article examines the relationship between transboundary conservation and international relations in the case of the Maya Forest, which refers to the tropical rainforest borderlands between Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. By analyzing transboundary conservation and its international relations, the article reveals how the strategy reinforces nature states. As a strategic complex composed of heritage sites and biosphere reserves, the Maya Forest is constructed as a shared biocultural landscape. However, national borders are simultaneously fostered by internationally adjoining protected areas to maintain the status quo. In conclusion, this strategy assists in building complex and subtle environmental international relations.

1. Introduction

The field of International Relations (IR) examines entities and interactions that form and inform the political world we live in: relations, structures, actors, spaces, and actions, and their dimensions of power at regional, global, and international levels. However, the field has frequently overlooked environmental issues, while borders—the founding unit of international relations—have often been of interest only when perturbed (Chandler et al., Citation2021; Laako, Citation2016). According to Stevis (Citation2017), although the field has increasingly included environmental issues over the past decades, particularly those regarding global governance and environmental security (e.g. Kütting, Citation2007; Susskind & Ali, Citation2015), interstate relations related to biodiversity conservation received less attention.

Yet, international conservation organizations (ICOs) have territorialized those important units—the borderlands—as protected areas. Simultaneously, they have engaged in international environmental relations, which sharpen the focus on interstate relations. In this article, we contribute to understanding these relations by addressing nature states in transboundary conservation.

Transboundary conservation is a strategy developed by ICOs, such as the IUCN (Erg et al., Citation2015; Mittermeier et al., Citation2005; Wolmer, Citation2003). It is based on identifying eco-regions that do not align with international borders but extend across them. According to Brenner and Davis (Citation2012), the strategy began in 1991 when the World Wildlife Fund, together with Flora and Fauna International, promoted cross-border collaboration between Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Rwanda in international gorilla conservation. This particular war-ridden experience highlighted the challenges of the existing environmental legislation mostly designed for peaceful times (Price, Citation2003).

To be sure, transboundary conservation has existed across the globe prior to this particular strategy. For example, the Waterton Glacier (1932) between the US and Canada is often cited as the first modern-era case (e.g. Erg et al., Citation2015; Mittermeier et al., Citation2005), although this Western history of conservation could be critically discussed (Büscher, Citation2013).

According to Mittermeier et al. (Citation2005, cover page), transboundary conservation refers to ‘an area that straddles international boundaries and is managed cooperatively for conservation purposes.’ According to these authors, the internationally adjoining protected areas (IAPAs) grew from 59 complexes in 1988–188 by 2005, including 818 protected zones in 112 countries, representing approximately 17% of the global extent of protected sites. For Erg et al. (Citation2015, p. 13), transboundary conservation implies multiple types of collaboration, running from intergovernmental and multilateral governance to mere cross-border meetings between park guards.

Currently, ICOs account for over 200 transboundary conservation cases worldwide (Erg et al., Citation2015; Mittermeier et al., Citation2005). This suggests that transboundary conservation is a potentially significant yet under-researched area in IR. This is further underlined by the two goals set by the strategy: (1) generating connectivity between protected areas along and across international borders, and (2) fostering peace-building between nation-states and border communities (e.g. Ali, Citation2007; Conca & Dabelko, Citation2002).

The latter has generated critical discussions on how nature conservation is embedded in socio-environmental conflicts, green violence, militarization, and illicit/violent activities that are also transboundary (e.g. Barquet, Citation2015; Büscher, Citation2013; Büscher, Citation2013; Duffy, Citation2006; Marijnen et al., Citation2020; Trogish, Citation2021; Ybarra, Citation2018). It has positioned conservation in the sphere of international conflict resolution, both as a source of contention and collaboration (Bankoff, Citation2012). It has also sharpened the focus on borderlands’ geopolitics.

Recent studies on political ecology and environmental history related to Global South, in particular, have discussed how conservation animates borders, sovereignty, and nation-states in different ways (e.g. Bankoff, Citation2012; Lee Büscher & Fletcher, Citation2018; King & Wilcox, Citation2008; Laako & Kauffer, Citation2021 and Citation2022; Peluso & Lund, Citation2013; Ramutsindela, Citation2014). Some scholars have also argued that it is difficult to find natural environments that would not be subject to conflict at some point in history and that current conservation policies are a recent phenomenon, to efficiently assess their effects (e.g. Dudley & Stolton, Citation2020). Ali’s (Citation2007) compilation of transboundary conservation cases worldwide suggests that transboundary conservation benefits from countries with considerably peaceful relations. The strategy could also gain from borderlands with no major human migration points or those that are sparsely populated or subject to firmly accommodated international agreements.

However, the predominant focus on the war/conflict–peace axes of transboundary conservation seems to assume that conservation practices strongly determine these. This calls for the investigation of deeper relationships between international relations and transboundary conservation, especially in the field of IR, which is the focal point of this article. What kind of global, national, and regional tendencies can help understand the role of transboundary conservation in IR? What are the cases and where are they located? To this end, this study suggests that transboundary conservation contributes to reshaping and reinforcing environmental international relations through nature states in international borderlands, beyond their perceived success or failure in peace-building. For example, it does so by augmenting their political legitimacy and fostering their borders, while engaging in shared landscape governance.

Nature States unfolds how states, as territorial bodies, have managed nature by using or overcoming it as an exploitable natural resource and as producers and owners of nature (Graf von Hardenberg et al., Citation2017). Graf von Hardenberg et al. (Citation2017) define nature states as the management of environmental affairs while emphasizing the roles of states as nature producers. This contributes both to reshaping landscapes and ecologies and expanding the role of the state. The authors stress that nature states care for nature, which also enhances their political legitimacy in the international arena. Nature states are alert to international relations in defining and reshaping the courses of action in the interplay of multiscale pressures, wherein states seek to affirm their responsibilities.

We explored the case of the Maya Forest (Selva Maya in Spanish), which embodies a strategic transboundary conservation complex between Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. Developed by ICOs and scientists in the 1990s, it aims to conserve the tropical rainforest region of Mesoamerica, recognized as an eco-region that crosses tri-nation borders (e.g. Nations, Citation2006; Primack et al., Citation1999). To date, the Maya Forest, as a transboundary conservation case, has not been subject to IR research even though a study of its rich, complex history and dynamics could directly address the pressing need to elucidate environmental international relations. Thus, this article contributes to understand the Maya Forest-concept development as a transboundary conservation case based on internationally adjoining protected areas (IAPA) and other conservation projects, which encloses often contradictory shared landscape and regional identity building, the Mayan roots of the eco-region, and border status quo.

Following the methodological section below, the article is divided into two parts, focusing on different sets of international relations. The first covers the global level at which the strategy is designed. We outline how IAPA-based strategic complexes are formed in Latin America as a part of new conservation priorities for tropical forests. In particular, the Maya Forest highlights the creation of a shared-biocultural landscape based on environmental legislation, mapping of landscapes and biodiversity, and the creation of heritage sites and biosphere reserves. The second part focuses on the regional level to examine interstate relations wherein transboundary conservation is practiced. The Maya Forest border history underlines the strengthening of borders through conservation efforts, particularly the IAPAs along the borders, which allows maintaining the status quo. Instead of TBPAs based on multilateral agreements, we found four contemporary Maya Forest projects—the Selva Maya Project, the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor (MBC), the Jungle Jaguar Corridor, and the Maya Forest Corridor—based on transboundary corridors with a focus on landscape continuity and sustainability, collaboration with communities, and transboundary park-guard meetings. Accordingly, we conclude that nature states may augment their political legitimacy and power displays with low stakes.

2. Approaching nature states in the Maya Forest case study

The recent concept of nature state originates from environmental historians (Graf von Hardenberg et al., Citation2017) with reference to Scott’s (Citation1998) work on state-building schemes. Scott (Citation1998) exposed legibility and simplification as central problems in statecraft, which can lead to a series of problematic and failure-prone interventions, not only in society, but also in terms of the natural world. The latter includes, according to Scott (Citation1998), modernist agricultural and scientific forestry schemes. In terms of forests, such schemes have led to the appropriation of nature for human use as ‘natural resources,’ such as timber or crops as new, legible forests.

Scott’s (Citation1998) work has inspired scholars to reconsider the role of the nation-state with its nature. For example, Peluso and Vandergeest (Citation2011, Citation2020), focusing on political ecology, developed the political forest concept to understand how states appropriated forests as new national territories by controlling contestation, defining forests as agricultural areas, and developing forestry legislation. Mapping was often the first step in the formation of political (i.e. nationalized) forests. ‘Environmental state’ refers to a state possessing a significant set of institutions and practices dedicated to the management of environmental interactions, including agencies, laws, and budgets (Graf von Hardenberg et al., Citation2017). Variably ‘green states’ and ‘ecological states’ have addressed state resource management, particularly from the 1960s onwards.

Graf von Hardenberg et al. (Citation2017) built on this multidisciplinary strand. However, their preference for the term nature states derives from the finding that environmentally related discourse and state building is not just a post-1960s tendency (see also Dorsey, Citation2009; Lewis, Citation2008). The authors also take a critical distance to the ‘resource curse,’ which addresses nature only in economic terms. According to their study, during the twentieth century, nature conservation fundamentally became a way for modern states to project their legitimacy. This represented an important shift in the usual display of power through technology and resource mobilization (such as dams): Nature conservation in the form of protected areas required the state to decree valuable places be set aside. Simultaneously, however, the stakes of engaging were low and ubiquitous, while the states endeavoured to produce nature according to what its experts perceived as nature’s blueprint.

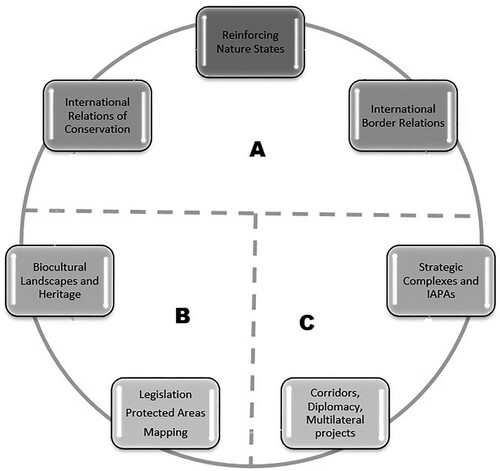

In effect, nature states also enable us to sharpen the focus on international relations related to nature conservation, which is the focus of this article. Consequently, it examines transboundary conservation from two interrelated angles: the international relations of conservation that fundamentally promote the creation of transboundary conservation complexes globally, and the interstate border relations, which form the geopolitical reality in terms of what can be actualized in the given space (see , a). These two intertwined sets of international relations include, on the one hand, the building of exterior legitimacy and multiscale collaboration, particularly focusing on shared biocultural landscapes (see , b). On the other hand, it allows diplomatic ambiguousness to maintain the border status quo (see , c).

We draw on research conducted between 2019 and 2020, studying the transboundary case of the Maya Forest, which is located in the borderlands of Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. Designed in the 1990s by scientists and ICOs, it is composed of a (planned and existing) web of protected areas, corridors, and megaprojects to protect the threatened biodiversity of fragile regions defined as humid tropical rainforests. The Maya Forest has also been frequently evoked in academic literature and tourism, although its meaning remains vague and undefined.

We traced the origins of the concept and found an empirical database of the early meetings in which the term was developed in the library of the research centre El Colegio de la Frontera Sur in Mexico (ECOSUR, 1995). These databases included original maps and brief articles consisting of definitions and mapping of the characteristics of the region by stakeholders.

We also carried out a literature review on both the Maya Forest and transboundary conservation, which allowed the analysis of developments and tendencies related to the region’s conservation and concept. Considering that one of the main actions employed by conservationists is mapping and territorial reconfigurations, not only did we examine and compare the existing maps, but also produced new ones to gain insights about developments in the Maya Forest and transboundary conservation globally. In the first case, we reproduced the Maya Forest map using the current protected areas. In the latter, we drew from the UNESCO Directory, Ramsar Wetland sites, and World Heritage Site lists (2020). This allowed us to locate the Maya Forest in an international context. They reflect political planning and decisions (Del Bosque et al., Citation2012). However, it is noteworthy that the UNESCO, Ramsar, and Heritage Site directories are constantly subject to changes and updates; thus, our mapping is based on information drawn from these sites in 2020. We also acknowledge that there is more room for critical discussion about the mapping strategy related to conservation and its international relations that can be addressed here (e.g. Harris & Hazen, Citation2006).

Additionally, we studied national- and state-level conservation laws and strategies, as well as border dynamics in the three countries. When publicly available, we also examined bilateral agreements between Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. We traced current conservation projects with active use of the Maya Forest concept to examine how the transboundary conservation case is currently evolving. These were mainly pertaining to ecological or biological corridors, and currently, there is little existing research on them. Finally, we also supported our findings with approximately 15 semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted in 2019 and early 2020 with conservation actors within the Maya Forest. The actors involved representatives of governmental conservation institutions, local offices of ICOs, and local conservationist non-governmental organizations, particularly in Mexico and Belize. Some team members have also conducted extensive transboundary research on conservation issues in Mexico and Guatemala prior to this project (e.g. Kauffer et al., Citation2019; Laako & Kauffer, Citation2021 and Citation2022).

Upon triangulating and comparing the empirical materials and mapping, we identified two sets of international relations built in transboundary conservation: 1) the global level of conservation tendencies with multiple actors that also drive national legislation tendencies, and 2) the regional level of international relations between the countries where concrete protected areas and projects evolve and interact with borders and peoples. The rest of the article is structured accordingly to understand the underpinnings of nature states in transboundary conservation.

3. International relations of conservation

3.1. Locating the strategic complexes of transboundary conservation in Latin America

In this section, we discuss the strategy of transboundary conservation, its origins, and international relations, particularly in Latin America. We map the transboundary conservation cases and introduce the concept of strategic complexes to address how transboundary conservation serves both to foster national borders status quo, and to build landscapes as shared governance.

Transboundary conservation is defined by ICOs as a strategy involving conservation practices along and across international borders. An array of terms is used to refer to these efforts, albeit limited to protected areas: transboundary protected areas (TBPAs), transfrontier conservation areas, transboundary natural resource management areas, and peace parks that emphasize a history of conflict (Erg et al., Citation2015). We underline that the original definition extends beyond protected areas although the scholarship on transboundary conservation is predominantly focused on these. The protected areas are certainly easier to map. However, as Brenner and Davis (Citation2012) note, even the mapping of cases presents some challenges because few protected areas actually cross national borders in real life. Thus, the term ‘transboundary’ is ambiguous. This ambiguity and lack of formal transboundarity (i.e. bi- and multilateral agreements) has also limited scholarship in search of rigorous categories. However, as we suggest in this article, it is precisely this ambiguity, and the building of what we call the strategic complexes of transboundary conservation based on IAPAs, that are the way of reinforcing nature states’ relations both internationally and in their borders.

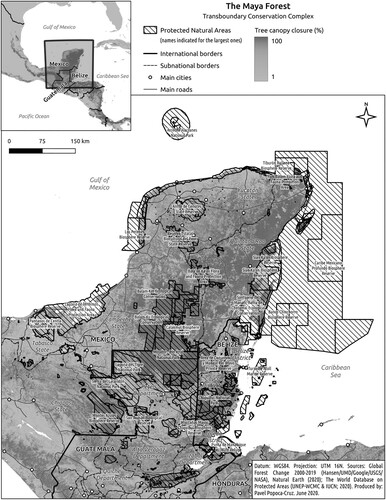

To obtain the factual transboundary conservation cases, we first identified the category of TBPAs that have a UNESCO-recognized transboundary character: These are biosphere reserves, Ramsar, and heritage sites (UNESCO 2020). These UNESCO-recognized TBPAs are transboundary in its rigorous meaning in the sense that they are based on recognized bi- and multilateral agreements between countries. below (see ) reveals that approximately 80% of these formal TBPAs are located in Europe.

Figure 1. Transboundary Conservation, Tropical Forests, and Biodiversity Hotspots. Source: Pavel Popoca-Cruz.

Next, we created the category of a strategic complex for transboundary conservation. This refers to complexes composed of protected areas along international borders. ICOs have pointed out the strategic complexes in various publications (e.g. Erg et al., Citation2015; Mittermeier et al., Citation2005) or academic publications (such as Ali, Citation2007), usually under a title that (unofficially) characterizes the eco-region. These are composed of IAPAs. As shown in below (see ), we find that their specific location is in the Global South, particularly in Latin America. These complexes now also consist of a main global conservation priority: biodiversity hotspots (Marchese, Citation2015).

As shown in , many of the strategic complexes consist of tropical forests. This indicates that many conservation efforts in Latin America, where our case study is located, are globally tied to tropical ecology. Tropical ecology emerged in the 1970s when pressure for logging increased in tropical forests, previously considered hostile places (e.g. Anderson, Citation2003; Corlett & Primack, Citation2008). There has since been an important shift from the predominant conservation model focused on the pine forests in the Northern Hemisphere (often materialized in national parks) to the priority of tropical forests in the Southern Hemisphere (often materialized in the notion of biodiversity, such as biosphere reserves), which in itself indicates the changing international relations of conservation. Both tropical ecology and transboundary conservation have been fostered by different international tools, such as the UNESCO Man and Biosphere Programme (1972), the Convention of Migratory Species (1983), and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (1963), before the Convention of Biological Diversity (1992). These tools also represented early steps in addressing plausible mechanisms for preventing and addressing wartime or conflict damage to nature (Austin & Bruch, Citation2020). According to Austin and Bruch (Citation2020, p. 178), one of the inclusion criteria in the list of World Heritage Sites is the outbreak or threat of an armed conflict, although the convention is mainly based on the objective of strengthening the appreciation and respect of the people toward their cultural and natural heritage.

According to Mittermeier et al. (Citation2005, p. 31), the concept of transboundary conservation was formally introduced in Central America in the 1974 First Central American Meeting on the Management of Natural Resources and Cultural Resources, ‘which stated that border areas with natural and cultural characteristics of interest to both countries, and which might benefit from an integrated protection strategy, should be jointly managed.’ In their view, the first actual TBPA was the creation of Los Katios National Park in Colombia, together with Darien National Park in Panama (1979–1981). They are currently identified as UNESCO natural heritage sites. However, many cases have been declared the ‘first ones’ (Erg et al., Citation2015; Mittermeier et al., Citation2005; UNESCO Directory, 2020). This is due to the difficulty of pinpointing the dates of creation that would allow the generation of historical timelines, as these could represent the endorsement of a single protected area along a border (which may be different on either side of the border), or its latest extension or change in conservation category, the first governmental declaration or identification by the ICOs, or the creation date as a TBPA or other site recognized by UNESCO.

There are currently 38 natural UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Latin America, of which only one is formally transboundary: the Talamanca-Range-La Amistad between Costa Rica and Panama, with a joint presidential declaration issued in 1979 and an implementation agreement made in 1983 (Carbonell & Torrealba, Citation2008). There are 130 UNESCO-recognized biosphere reserves in Latin America, three of which are categorized as transboundary: La Selle-Jaragua-Bahoruco-Enriquillo (2017) between the Dominican Republic and Haiti, El Trifinio Fraternidad between Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador (2011), and Noroeste Amotapes Manglares-Bosque Seco-Bosques de Paz between Peru and Ecuador (2017). In addition, there are 210 internationally recognized Ramsar-wetland sites, but none is transboundary (UNESCO, 2020). Indeed, this indicates that most of the transboundary conservation cases in Latin America are strategic complexes composed of IAPAs along international borders – not TBPAs.

The strategic complex Iguazú-Iguaçu, between Argentina and Brazil, forms one of the earliest cases in Latin America. Argentina had already set the area aside for conservation in 1909, but it was formally established in 1934. Iguazú became a World Heritage Site in 1984. On the Brazilian side, the protected zone was decreed in 1939 and listed as a World Heritage Site in 1986 (Aquino & Name, Citation2017; Freitas, Citation2017; Mittermeier et al., Citation2005). According to Freitas (Citation2017), the goal of this transboundary conservation initiative was to guarantee access to Iguazu Falls and later to protect subtropical Atlantic forests. Initially, the border region had a low population density due to a history of military conflict. Nevertheless, from the 1950s onwards and with the construction of a passing highway, new settlers relocated within the national park on the Brazilian side. This relocation led to settler land conflicts within the protected zone, which resulted in evictions in the 1970s. The military government left behind a secondary forest as part of the protected area, previously cleared by the settlers who had now moved to a new, nearby area, to be cleared from the original forest. Garfield (Citation2012) notes that the Brazilian Amazon, the world’s largest remaining rainforest, also epitomizes the tug-of-war in the North–South divide in environmental politics and acts as a contested space of often contradictory interests.

According to Mendoza et al. (Citation2017), the transboundary Patagonia region has been characterized by military violence against Indigenous communities and their eviction, followed by settler colonialism and livestock farming. Since the 1990s, the region has become part of a geopolitical green plan managed by the state, outdoor corporate industry, and civil society stakeholders to generate ‘eco-regionalism’ for conservation and (eco)tourism (Mendoza et al., Citation2017). According to Wakild (Citation2017), the Patagonian case, along the border between Chile and Argentina, included incentives for both tourism (the Argentinian side) and forestry (the Chilean side). The first IUCN Conference on Latin America (1968) took place in the Nahuel Huapí National Park in Patagonia to celebrate the historical depth of conservation in this frontier region (Wakild, Citation2017). Indeed, Wakild (Citation2017, p. 39) refers to scientists and ecologists in contributing to nature state building, not only in studying the lands and their contents, but also in influencing the state in environmental legislation. Environmental historians have noted that in Latin America, nature conservation has tended to materialize because of scientists’ efforts via states rather than environmental movements, as in North America and Europe (e.g. Miller, Citation2007).

The discussion suggests that (transboundary) conservation in Latin America is promoted by scientists via nature states, but it is simultaneously embedded in uncertainty over land rights (Freitas, Citation2017; Wakild, Citation2017). Furthermore, many protected areas emerged during dictatorships and military governments in the twentieth century. Thus, complex struggles for land, territory, and natural resources often lie at the core of conservation challenges in Latin America (e.g. Dudley & Stolton, Citation2020; Miller, Citation2007). According to Medina (Citation2020), contemporary border formation on the basis of ecological sanctuaries is at odds with the simultaneous exploitation of natural resources. The IAPA-based strategic complexes add to this border ambiguity and the status quo.

The concepts of World Heritage and Biocultural Conservation were fostered in the 1990s with biodiversity protection (Aquino & Name, Citation2017). Given the considerable amount of tropical forests now composed of IAPA-based heritage sites and biosphere reserves based on environmental collaboration suggests the building of international relations of conservation based on shared biocultural landscapes ripe not only for more integrated conservation approaches, but also (eco)tourism. During the twentieth century, landscapes were often imbued with wilderness far away from people. However, currently, the notion of biocultural landscape has become a symbol of links between communities and their heritage, materialized in the UNESCO World Heritage Sites, among others (Cocks & Dold, Citation2012). This is also illustrated in the Maya Forest case discussed in the following.

3.2. The Maya Forest: the bold vision of the shared biocultural landscape

The Maya Forest? Well, I think it originated to identify the problem and risk in the most important forest cover [in Latin America] after the Amazon. ‘Which area?’ they asked. It’s called the Maya Forest. However, it has been debated whether the transitional vegetation towards the Peninsula, and whether the rainforest or the Caribbean. It also had to do with the tourism of the Peninsula, which then expanded to Guatemala and Belize. Indeed, one of the problems that the idea of the Maya Forest created was that many states sought to get integrated into the project, but not just for the purpose of nature conservation.

Governmental representative involved in various conservation projects related to the Maya Forest, Chetumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico, December 11th, 2019

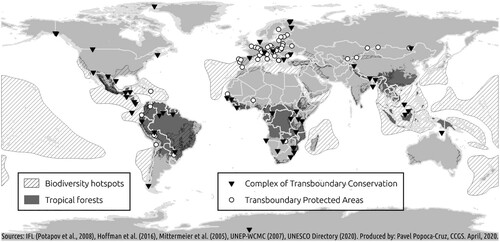

ICOs and scientists developed the concept of the Maya Forest in the 1990s. The database of the ECOSUR (1995) shows that an international workshop organized in 1995 by the US Man and Biosphere Programme (USMAB), together with the CI, ECOSUR, MAYAFOR, the Wildlife Conservation Society, the Caribbean Conservation Corporation, Paseo Pantera Consortium, NASA, and the University of Florida (among others), created the first maps of the Maya Forest to foster its existing and planned biodiversity conservation (see below). According to this plan, the Maya Forest consists of humid rainforests located in the international borderlands between Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. These include the southern Mexican states of Quintana Roo, Campeche, Tabasco, and Chiapas, the Department of Petén in Guatemala, and all of Belize. Connecting biosphere reserves were defined as the backbone of the Maya Forest: (1) the Montes Azules in Chiapas; (2) the Pantanos de Centla in Tabasco; (3) the Calakmul in Campeche; (4) the Montañas Maya and Chiquibul, connecting the borderlands between Guatemala and Belize; and (5) the Maya in Petén (see below).

Figure 2. The Original Maya Forest Definition. Source: University of Florida et al., 1995 (Scanned from original ECOSUR Databases in 2020).

The maps stressed ecological connectivity and archeological sites, which is the main reference to the ‘Maya.’ The data demonstrate that the Maya Forest is a single ecosystem and has been home to Maya-speaking people for more than 5,000 years, although it is less populated today and has a smaller percentage of people who continue to identify as Mayans (ECOSUR, 1995). Thus, ‘Maya’ refers to the classic Mayan civilization, which modified the forest over centuries as a ‘human artefact’ before becoming subject to biodiversity conservation as forest gone wild following the collapse of the Mayan civilization (Ford & Nigh, Citation2016; Miller, Citation2007; Nations, Citation2006).

The ECOSUR databases were later published by Primack et al. (Citation1999) and the Nations’ book (2006). According to these sources, the construction of the transboundary eco-region began in the 1970s and the 1980s, both as part of tropical rainforest conservation and the emerging touristic Maya Route-development, promoted by the National Geographic. These actions fundamentally included mapping the region to understand it as an eco-region. The building of the Maya Forest is thus tied to the identification of the border-crossing tropical eco-region, sustained by the biosphere reserves, and the acknowledgment of the common Mayan history, particularly for tourism purposes: The ‘Maya’ has been exploited during the past decades in various touristic (inter-)governmental megaprojects, such as Mundo Maya, Riviera Maya and Ríos Mayas. During our research, some interviewees in fact pondered that perhaps the Maya Forest referred to the current Mexican governmental tourist project Tren Maya, which consists of a train to connect both protected areas and archaeological sites in the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico.

However, conservationists currently employing the term emphasized that it had to do with a forest that belongs to the Mayans (contemporary or ancient) as owners and stakeholders. Active rewriting of the Mayan history has also taken place by scholars to show the Mayans as active and knowledgeable guardians of their forests (Ford & Nigh, Citation2016). However, it is noteworthy that currently many conservation projects in the region include mainly settler communities, both Indigenous and others (Laako & Kauffer, Citation2021 and Citation2022).

The perception of what the Maya Forest geographically includes as a shared landscape is also subject to debate. The Maya Forest, originally defined as the Mesoamerican humid tropical forests composed of the classic Mayan civilization, excludes the Mexican states of Veracruz and Oaxaca, as well as Honduras and El Salvador in Central America, despite containing similar history and geographical characteristics (ICF, 2014; MARN, 2011; Martos, Citation2010). Some authors also prefer leaving out the state of Tabasco by arguing that because it has been deforested, it should not be considered part of the Maya Forest (Arana, Citation1990; Toledo et al., Citation2009). With the federal endorsement of the Usumacinta Canyon wildlife reserve in 2008, some authors have stressed the importance of Tabasco by restoring landscapes (Pinkus, Citation2010). In our interviews, some governmental representatives indicated that the Maya Forest includes only the protected areas in Campeche and Quintana Roo, along with their direct counterparts in Guatemala and Belize, because it is the focus of their particular conservation project. Academically, the Maya Forest has referred to the Guatemalan Maya Biosphere Reserve (Ybarra, Citation2018), as well as communities and protected areas in the Yucatán Peninsula, which was not originally included in the humid rainforest based Maya Forest delimitation (Martínez, Citation2017).

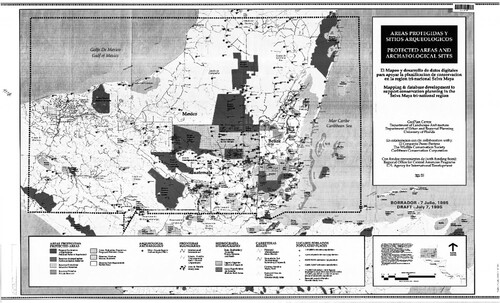

To understand how this shared forest-scape has evolved since the 1990s, we created an updated map (see below). The map excludes voluntary and/or private protected sites, which have increased considerably since 2000 in Mexico and Guatemala, although they are small in area (Kauffer et al., Citation2019). We also decided to extend the map to Yucatán given that many interviewees considered it as part of the current Maya Forest.

There are currently five protected zones located directly along the international border in Guatemala, six in Mexico, and eight in Belize. These bordering protected areas range from biosphere reserves to national parks, forest reserves, and wildlife refuges. There are no UNESCO-recognized TBPAs, only IAPAs. The exception is Belize, which seems to have declared a unilateral transboundary Ramsar-wetland site (Sarstoon Temash National Park) with Guatemala (UNESCO, 2020).

There are several UNESCO recognized protected areas near the international borders. These include six heritage sites on the Mexican side. The Sian Ka’an in Quintana Roo is defined as a natural site, and Calakmul in Campeche as cultural and natural. Guatemala has one heritage site, the national park of Tikal, defined as both cultural and natural. Belize also has one heritage site, the Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System, which is registered as a natural site. In the Maya Forest, Mexico has 10 biosphere reserves, half of which are marine. Guatemala only has the Maya biosphere reserve, but it covers almost half of Petén. Belize does not have protected areas recognized under the UNESCO category of biosphere reserves. In the international category of Ramsar-wetland sites, Mexico currently has 12 within the Maya Forest, Guatemala has 2, and Belize has 2 (UNESCO, 2020). Guatemala does have a TBPA with El Salvador and Honduras (Trifinio Fraternidad), but this is not included in the Maya Forest delimitation. The also shows the current tree canopy closure.

These specifications about the region are important in showing that the Maya Forest comprises UNESCO-based protected areas that sustain it, centred in the 1972 World Heritage Convention and the 1992 Biological Diversity Convention, both focused on the educational and informational aspects of landscapes to avoid environmental destruction.

The IAPAs are sustained by the national legal framework, which allows the creation of polygons of protected areas along the international border and builds institutional presence. Mexico, for example, backed up the model of biosphere reserves; one of the first biosphere reserves in the country was Montes Azules (1978) in Chiapas, which forms one of the building blocks of the Maya Forest. The first Environmental Law (LGEEPA) was decreed in 1988, followed by the Wildlife Conservation Law in 2000. In addition, several forestry laws and incentives have been employed, particularly since 2000, such as ecosystem payments and units for wildlife management. The governmental institutions that play an important role in the Maya Forest currently consist of the Biodiversity Commission (CONABIO, 1992), the Commission of Natural Protected Areas (CONANP, 2000), and the Forestry Commission (CONAFOR, 2001), all of which have participated in or initiated Maya-Forest-related projects.

Guatemala’s constitution dates back to 1986, when the first Environmental Law and Commission were endorsed. The Law for Protected Areas was passed in 1989, along with the Council of Protected Areas (CONAP). The Guatemalan Law for Protected Areas (1989, Article 17) states that ‘protected areas on borders will be promoted to celebrate the conventions between this country and its neighbours to achieve protective measures concordant with these countries.’ In the same year, along with the Peace Accords (1996), the Forestry Law was enacted with the creation of the Forestry Institute (INAB). Institutionally, the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources was formed in 2000, but it did not have a conservation policy until 2007. In Guatemala, protected zones are managed by various private entities such as universities, ICOs, and NGOs, although they relate to the National System of Protected Areas (SIGAP) (Laako & Kauffer, Citation2021 and Citation2022). In Belize, the constitution was endorsed in 1981, along with the Wildlife Conservation and National Park Laws. These were followed by the Coastal Management Law (2000), the Environmental Protection Law (2008), and the Conservation Action Plan (2015–2018), as well as corresponding institutions, such as the Coastal Zone Management Authority and Institute (CZMAI) and the Department of Forestry. Conservation policies in Belize are sustained by the Constitution (Belize Constitution Act, 2000; Environmental Protection Act, 2000), which integrates diverse environmental agreements. In Belize, NGOs and ICOs often manage protected areas. In 2020, Belize established the National Biodiversity Office in charge of implementing the biodiversity agenda (Press Office, Belize Government, 2020).

Predominantly composed of heritage-based IAPAs, international and regional collaboration combined equipped with national environmental legislation, the Maya Forest reinforces the nature states in their common goal of entire landscape management although, as mentioned by our interviewee in the beginning of the section, not always for nature conservation purposes only.

4. International border relations

4.1. Fostering borders, maintaining status quo in the Maya Forest

We actively collaborate with our Guatemalan counterparts, we have shared workshops. . . . We have even thought of joint patrolling in the forest reserves between Belize and Guatemala. But yes, there is the border dispute: Guatemala feels that part of the South of Belize belongs to them, but Belize is a sovereign country and does not want to lose any part of it. So we work together [with their counterparts in Guatemala], and the organization of projects is not a problem, but the governmental approvals are, because if they agreed to transboundary deals with each other, it would mean the approval of borders, which are in dispute.

Representative of a local office of an ICO in Belize, January 16th, 2020

The mentioned original ECOSUR databases (1995) refer to international borders. The maps state that ongoing attempts to slow down expanding agriculture, timber harvesting, and cattle ranching are hampered because the Maya Forest is divided among three independent nations (ECOSUR, 1995). Thus, the purpose of the Maya Forest’s construction was to enable collaboration between a range of institutions across boundaries to coordinate forest management in this region (ECOSUR, 1995).

The international borders between Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala were formed in the context of diverse conflicts involving both the establishment of territorial limits and concrete actions to achieve both the acknowledgement of national autonomy and regional integration. Overall, intergovernmental collaboration has been marked by intermittent, fragmented relations. The formation of international borders is also tied to different aspects of natural resources/elements, which are now subtly restored and reshaped by transboundary conservation efforts.

The Mexican-Guatemalan border was defined in 1882 because of timber trade ambitions. Mexico was interested in taking advantage of the valuable timber of the supposedly unoccupied rainforests. This border formation coincided with what historian De Vos (Citation1996, p. 11) calls the ‘golden era of mahogany.’ The Usumacinta River simultaneously became a 365 km fluvial border between the two countries (Laako & Kauffer, Citation2021 and Citation2022). Notwithstanding, Mexico and Guatemala had ongoing disagreements over international waters, and border negotiations were affected by the interests of timber companies, ambiguous cartographies, and diplomatic strife (Olivera, Citation2008).

The border between Mexico and Belize was defined in 1893 for the same reasons (e.g. Laako, Citation2016). At this point, Belize, created as British Honduras in 1862, still belonged to Great Britain. Historically, Belize’s forest resources played a central role in the country’s establishment, occupied first by Spaniards, but eventually conquered by British pirates and taken up by British loggers (Nations, Citation2006).

Belize became independent in 1981, but this generated a border dispute with Guatemala, defined in 1859, and, based on treaties from the Spanish colonial era, Guatemala periodically claimed sovereignty over parts of Belizean territory. Guatemalan authorities recognized Belizean independence in 1991, but tensions continued. Mexico has indicated that while it has renounced its rights to Belizean territory, it might change its stance (Oehling, Citation2015; SRE, 2018, pp. 50–55; Toussaint, Citation2009, pp. 105–128). Mexico has often sided against Guatemala in border conflicts, but Mexican authorities have been inconsistent with its southern neighbours (Toussaint, Citation2009).

Between 1981 and 2000, there were nine initiatives for border negotiations on behalf of Guatemala or Belize, but these attempts failed. According to Toussaint (Citation2009), one of the latest attempts to reconcile border differences was in 2002, carried out in the Ecological Park Belize-Guatemala-Honduras. In 2003, Guatemala announced that it did not accept the terms of the reconciliation panel. Hence, in 2007, Belize and Guatemala declared they were incapable of arriving at a consensus and concluded that they were willing to bring the disputes to the International Court of Justice (Toussaint, Citation2009). This was also the reference point of our interviewee (cited above) in Belize. Another example of the difficulty in achieving multilateral agreements between the countries would be the International Boundary and Water Commissions created bilaterally between Mexico and Guatemala, and Mexico and Belize (CILA MEX-GUAT & CILA MEX-BEL, 2016). While the ecological sanctuaries located along international borders may serve as spaces for diplomacy, border relations seem to override conservationist pressures for transboundary agreements.

Despite sharing the history of Mayan civilization and colonization, the eco-region and its six transboundary river basins (Kauffer, Citation2018), the Maya Forest has witnessed conflicts with transboundary impacts, although international wars have been avoided. The Guatemalan civil war (1960–1996) and the Chiapas Zapatista uprising (1994) both drew international attention and increased state presence, and also had a longer-term effect in enhancing the visibility of Indigenous rights. During our research, Indigenous rights as the basis for the ‘Maya Forest’ were brought up only by few conservationists.

Indeed, many contemporary conservation laws and institutions, including protected areas, have been endorsed and implemented during the civil war, which involved scorched-earth strategies, dislocated communities, refugees, and militarization in the Maya Forest (Ybarra, Citation2018). In the twenty-first century, these borderlands have seen increasing migration and tightened migration control policies and occupation by drug cartels, which again heightens the presence of the military and police. Yet, as Duffy (Citation2000) has shown, these kinds of peripheral borderlands usually lack extensive national control over the territories and are distinguished by semi-clandestine trade and smuggling corridors. Berke (Citation2018) deemed the Mexican-Guatemalan borderlands a contraband corridor, while Arriola (Citation2005) described the Ceibo-Naranjo corridor along the Guatemalan border with Mexico, where local communities deal with changing state relationships while constructing their own socio-cultural space. In this context, conservation efforts occasionally thrive and sometimes represent a nuisance for local communities, depending on the extent to which conservation projects can foster the autonomy of the communities (Laako & Kauffer, Citation2021 and Citation2022).

In 1991, Mexico and Belize signed a bilateral agreement concerning protecting and conserving natural resources in the border region. This agreement excluded Guatemala (PAOT 2020). In 1987, Mexico and Guatemala signed a convention on the protection and conservation of their border regions, including an agreement on the prevention of natural disasters. In 1997, the two parties signed an agreement to foster environmental cooperation between the Mexican Secretary and the Guatemalan Commission of Natural Resources (PAOT, 2020). However, multilateral agreements have tended to exist more on paper than in reality and have often resulted in contradictions in local contexts and/or with other policies (List et al., Citation2017).

In this context, the creation of polygons of IAPAs along international borders, together with related institutions, laws, and projects, may help with cohesion in the border relations. That is, it may make it difficult for a neighbouring country to engage in new territorial claims in the shared ‘Maya Forest’ protected by the IAPA presence. However, this should not be interpreted automatically as peace/conflict building. Rather, we suggest that transboundary conservation is intertwined with subtle, diplomatic border relations.

4.2. Contemporary Maya Forest conservation and its transboundary challenges

The Maya Forest is a macro-level strategy that seeks to connect biodiversity hotspots in the form of corridors, and it involves different actors, even international organizations … . The Maya Forest generates an approach that covers many things based on collaboration to protect biodiversity.

Representative of a local office of an ICO in Belize, January 16th, 2020

Our research identified four transboundary conservation projects in the Maya Forest: 1) the Selva Maya Project, 2) the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor (MBC), 3) the Jungle Jaguar Corridor, and 4) the Maya Forest Corridor. All these efforts relate to the Maya Forest concept. So far there has been little research on the corridors. They all involve nature states in the form of governmental participation, particularly related to IAPAs, and they also include some sort of cross-border collaboration. Many of them also include a focus that has shifted from the exclusivity of protected areas to connecting landscapes or wildlife between and beyond them, ensuring greater collaboration with the surrounding communities. According to our research results, many of them also consider that while the principal challenges to the Maya Forest conservation are transboundary (illegal logging, hunting, and wildlife trade), the possibility of collaborating in a firmly transboundary manner to address these challenges is complicated because of the lack of interstate agreements.

First, the Selva Maya Project, financed by the German agency GIZ (earlier called GTZ), has been working with the Commissions of Protected Areas in the three countries since 2000. Regionally, the project is focused on the states of Campeche and Quintana Roo and their counterparts in Petén and Belize. The project is focused on improving the positioning of the Maya Forest on multiple conservation levels by augmenting the collaborative capacities of the institutions—the nature states—involved. Additionally, various projects have been employed to monitor the situation of conservation in IAPAs. According to our interviewees, the project has detected various transboundary problems related to illegal logging and trafficking of endangered species. However, their transboundary collaboration was limited to meetings between park guides from the three countries and these meetings were often complicated by border control and migration check-points.

Second, the MBC was created in the 1990s as an intergovernmental initiative to connect the protected parts of Central American countries (e.g. Finley-Brook, Citation2007). The IUCN and the World Commission of Protected Areas (WCPA) list the MBC as part of their global transboundary conservation network. The MBC partially covers the same region as the Maya Forest, and the two projects certainly overlap but are not synonymous. Yet, they share the same governmental institutions. Our interview results indicate that the MBC in Mexico changed its definition of ‘corridor’ in the mid-2000s: Instead of focusing on creating new protected areas to connect with the old ones, the project centred on connecting landscapes through collaboration with communities for sustainable development. Although intergovernmental, the project was mainly focused on connectivity along the border within each national territory. Moreover, the MBC ended in Mexico, with the latest change in government.

Third, the transboundary Jaguar Corridor Initiative extends from Mexico to Brazil and Argentina, including Belize and Guatemala. It comprises various ICOs, government institutions, and communities (e.g. Panthera, 2020), and is not exclusively focused on protected areas. Recently, a report was published on how the cattle ranchers could better protect themselves from jaguars without the need to hunt them (De la Torre et al., Citation2021). This initiative has resulted in a promising focus on jaguars, and communities beyond protected areas do not require interstate agreements to improve conservation. This project on the Mexican-Guatemalan border directly references the Maya Forest concept by using the term in the geographical delimitation of the project.

Finally, in Belize, there was a new initiative from 2019 to create a Maya Forest Corridor, which would connect the country’s southern protected areas to those in the borderlands of Mexico and Guatemala. In fact, for our Belizean interviewees, the Maya Forest was understood as a reference to this new corridor initiative. The plan is in its early stages. However, our interviewees had long-term experience in collaboration with their counterparts in Guatemala. As cited earlier, the ongoing attempts were nevertheless hampered by governmental border disputes with Guatemala and formed an obstacle in handling conservation challenges, particularly in the Chiquibuil reserves.

These four contemporary conservation projects include shared governance related to landscape management (Dudley & Stolton, Citation2020). They also build on or relate to the concept of the Maya Forest. As the projects indicate, transboundary conservation suits nature states as long as no concrete border implications emerge. Yet, in those collaborations, nature states are reinforced and reshaped by two intertwined sets of international relations: the global conservation ones and the international border ones (see ).

5. Conclusions

In this study, we examined the relationship between transboundary conservation and international relations. We clarified two sets of international relations that reinforce nature states: the international relations of conservation composed of multiscale actors, collaboration and conservation agreements, and international border relations subject to diplomatic interstate relations, although intertwined with transboundary conservation pressures. Strategic complexes of transboundary conservation, consisting of IAPAs and particularly materialized in tropical forests in Latin America, allow international relations to be approached beyond the predominant war/peace axis. Thus, transboundary conservation is a strategy for building complex environmental international relations across the globe and the concrete practices and challenges related to these cases.

Transboundary conservation has alerted us to nature states, which are pursued within global conservation strategies materialized especially in scientific mappings of biodiversity, national environmental legislation, and the creation of internationally adjoining protected areas. In terms of international relations, these helped promote biocultural heritage to project legitimacy and eco-tourism, while the stakes of engaging have been low and often ambiguous, especially concerning transboundary agreements. This is due to the interstate relations in the borders, here, the Maya Forest between Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. We analyzed the border history and current dynamics in the context of specific conservation projects.

The Maya Forest contributes to the creation of a shared biocultural landscape, which allows governments to enhance their own plans for the region while fostering their political legitimacy and presence both in the borders and within the international arena. Simultaneously, it preserves the status quo of the borders. These aspects were illustrated in the emphasis of the IAPAs and governmental participation in the four contemporary transboundary conservation projects.

These subtle challenges related to the Maya Forest, we argue, unfold the strategy of transboundary conservation as a significant component of international relations. Similarly, we sustain that to understand the implications of transboundary conservation in IR, the focus on mere TBPAs or the existence of multilateral endorsements may be too narrow; the absence of those is also part of the building of environmental international relations.

Further, this study has stressed how transboundary conservation incites international relations is not limited to the predominant war/conflict–peace axis. Hence, we studied the Maya Forest from the perspective of nature states to expand on different subtle interstate aspects. Nature states, as evidenced in the Maya Forest, are also producers of nature, and in this activity, they reshape landscapes while expanding their institutional role. Conservation literature in Latin America has revealed multiple facets of nature states in dealing with inner conflicts of all types. However, so far less attention has been paid to how these also affect relations in international borders.

Kauffer (Citation2018) stressed that transboundary river basins challenge international borders, while being completely dependent on them; there are no transboundary river basins without borders. This also applies to transboundary conservation. By arguing for the creation of eco-regions beyond international borders while fostering peace-building, the strategy profoundly challenges borders. However, transboundary conservation does not exist without borders. This is particularly important in the context of Latin America, which indicates the predominant existence of strategic complexes. This may underline how nature states enhance their political legitimacy in international relations of conservation, while creating cohesion in their borderlands.

However, as noted by Graf von Hardenberg et al. (Citation2017), nature states are erratic and ever-changing, and this is also true in the Maya Forest and its international relations.

Acknowledgements

This research was carried between 2019 and 2020 within the Retenciones y repatriaciones programme of the Mexican Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT) in El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR). We thank both institutions for their support, and also University of Eastern Finland and the Academy of Finland. We thank the Kone Foundation that funds this Maya Forest research project. We extend our gratitude to Pavel Popoca-Cruz (CCGS) for elaborating the and in this article, Miguel Urbina (CIESAS) for fieldwork assistance, and Jemima Repo (University of Newcastle) and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful observations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hanna Laako

Hanna Laako is a senior researcher in the Department of Geographical and Historical Studies, University of Eastern Finland. She is currently conducting research on political forests—the Maya Forest—financed by the Kone Foundation (2020–2024) and the Mexican Council of Science and Technology (2019-2020). She holds a Ph.D. in Political Science and International Relations from the University of Helsinki, Finland. She has lived and worked for 10 years in Mexico. Her research interests include conservation politics, borderlands studies, international relations, and Mesoamerica. Her most recent publications include articles in Political Geography and Journal of Latin American Geography.

Esmeralda Pliego Alvarado

Esmeralda Pliego Alvarado is a postdoctoral researcher in Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (CIESAS, Mexico), and in the postdoctoral programme of the Mexican Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT). She currently researches water politics in Southern Mexico. She holds a Ph.D. in Social Science from Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Mexico. Her research interests include water management, climate change, and civil society. Her most recent publication is Alvarado, E. P., & Sánchez, G. J. G. (2019). Gobernanza y derecho al agua: Prácticas comunes y particularidades de los comités comunitarios de agua potable. Sociedad y Ambiente 20, 53-77.

Dora Ramos Muñoz

Dora Ramos Muñoz is a senior researcher at the Department of Society and Culture in El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR, Mexico). She currently researches social implications of science and information technology, disasters and social construction of risks, heritage sites, feminine workforce, oil industry, and Mesoamerica. She holds a Ph.D. in Ecology and Sustainable Development from the ECOSUR, Mexico. Her most recent publication is: Espinoza-Tenorio, A., Ehuan-Noh, R.G., Cuevas-Gómez, G.A., Narchi, N.E., Ramos, D.E., Fernández-Rivera Melo, F.J., et al. 2022. Between uncertainty and hope: Young leaders as agents of change in sustainable small-scale fisheries. Ambio 51, 1287-1301.

Beula Marquez

Beula Marquez holds a B.A degree in Biology from Universidad Autónoma de Tabasco, Mexico. She carried out research on the Maya Forest in El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR), Mexico, within the programme of Jóvenes Construyendo el Futuro, funded by the Mexican government between 2019 and 2020. Her research interests include conservation and genetic diversity.

References

Primary Sources

- CILA MEX-GUAT & CILA MEX-BEL. 2016. International Boundary and Water Commissions Mexico-Guatemala and Mexico-Belize retrieved Jan, 10, 2022, from https://www.gob.mx/sre/acciones-y-programas/cila-mex-guat-y-cila-mex-bel

- Central Belize Corridor. Conservation Action Plan 2015-2018. University of Belize Environmental Research Institute. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from http://www.eriub.org

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. (2020). Leyes y reglamentos. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from https://www.dof.gob.mx

- ECOSUR. (1995). Protected Areas and Archaeological Sites—Mapping and database development to support conservation planning in the Selva Maya tri-national region. Library, San Cristóbal de las Casas, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, México.

- Environmental Protection Act. (2000). Retrieved September 1, 2020, from http://www.belizelaw.org/web/lawadmin/PDF%20files/cap328.pdf

- Belize Department of Environment. (2000). Belize, green, clean, resilient and strong. 2014-2024 National Environmental Policy Strategy. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from https://www.greengrowthknowledge.org/national-documents/belize-2014-2024-national-environmental-policy-and-strategy-green-clean-resilient

- ICF. (2014). Mapa Forestal y Cobertura de la Tierra en la República de Honduras. 1:25000. República de Honduras: IC. Retrieved from https://sigmof.icf.gob.hn/?page_id=3871

- MARN. (2011). Catálogo Mapa Nacional de Riesgo ambiental. El Salvador: MARN-Dirección de Ecosistemas y Vida silvestre. Retrieved from http://www.marn.gob.sv/descargas/Documentos/2018/Catalogo%20de%20Mapas%20de%20Riesgo.pdf

- Panthera Organization, The Jaguar Corridor Initiative. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from https://www.panthera.org/initiative/jaguar-corridor-initiative

- PAOT. (2020). Tratados e instrumentos bilaterales. Retrieved from http://www.paot.org.mx/centro/ine-semarnat/informe02/estadisticas_2000/estadisticas_ambientales_2000/04_Dimension_Institucional/04_10_Cooperacion_internacional/RecuadroIV.10.5.pdf

- Press Office, Government of Belize (2020). “Belize establishes National Biodiversity Office on UN’s International Biodiversity Day”, Retrieved March, 23, 2022, from https://www.pressoffice.gov.bz/belize-establishes-national-biodiversity-office-on-united-nations-international-biodiversity-day/

- Ramsar, International Wetland Sites. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from https://www.ramsar.org/country-profiles Belize Transboundary Ramsar-site. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from https://www.ramsar.org/news/belize-adds-part-of-transboundary-wetland

- Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. (2018). Tratado de límites entre los Estados-unidos mexicanos y Honduras británica. Secretaría de la Cámara de Senadores del Congreso de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. ISBN-13: 978-0656630226 (reimpresión).

- Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. (2020). Tratado de Límites entre los Estados Unidos Mexicanos y la República de Guatemala. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from https://aplicaciones.sre.gob.mx/tratados/muestratratado_nva.sre?id_tratado=616&depositario=0

- Selva Maya-project (GIZ) and the Belizean Maya Forest Corridor. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from https://selvamaya.info/en/endorsement-of-the-maya-forest-biological-corridor-in-central-belize/

- University of Alicante. (2000). Belize Constitution Act Chapter 4. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from https://www.uaipit.com/uploads/legislacion/files/1380642103_Belize_constitution_Act.pdf.

- UNESCO Directory. (2020). Biosphere Reserves in Latin America and the Caribbean. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from https://en.unesco.org/biosphere/lac

- World Heritage List. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/?search=&searchSites=&search_by_country=®ion=3&search_yearinscribed=&themes=&criteria_restrication=&media=&order=country&description=&type=natural

- Trifinio Fraternidad. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/ecological-sciences/biosphere-reserves/latin-america-and-the-caribbean/el-salvadorguatemalahonduras/trifinio-fraternidad/

Literature

- Ali, S. (2007). Peace parks: Conservation and conflict resolution. MIT Press.

- Anderson, W. (2003). The natures of culture: Environment and race in the colonial tropics. In P. Greenough, & A. Lowenhaupt (Eds.), Nature in the global south: Environmental projects in South and Southeast Asia (pp. 29–46). Duke University Press.

- Aquino, G., & Name, L. (2017). Patrimonialización y gestión del territorio en la triple frontera de Brasil, Argentina y Paraguay: Continuidades y desafíos del parque iguazú. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 67(67), 167–182. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-34022017000200009

- Arana, M. (1990). Educación y gestión ambiental en la selva de Chiapas. In E. En Leff, J. Carabias, & A. Batis (Eds.), Recursos naturales, técnica y cultura. Estudios y experiencias para un desarrollo alternativo (pp. 335–356). CIIH.

- Arriola, L. (2005). Agency at the frontier and the building of territoriality in the Naranjo-Ceibo Corridor, Petén, Guatemala [PhD Dissertation]. Gainesville: University of Florida.

- Austin, J., & Bruch, C. (2020). Legal mechanisms for addressing wartime damage to tropical forests. In S. Price (Ed.), War and Tropical Forests: conservation in Areas of Armed conflict (pp. 167–199). Haworth Press.

- Bankoff, G. (2012). Making parks out of making wars: Transnational nature conservation and environmental diplomacy in the twenty-first century. In E. Bsumek, D. Kinkela, & M. Atwood (Eds.), Nation-States and Global Environment: New Approaches to International Environmental history (pp. 76–96). Oxford University Press.

- Barquet, K. (2015). “Yes to peace”? environmental peacemaking and transboundary conservation in Central America. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 63, 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.05.011

- Berke, R. (2019). Contraband corridor: Making a living at the Mexican-Guatemalan border. Stanford University Press.

- Boyer, C. (2015). Political landscapes: Forests, conservation and community in Mexico. Duke University Press.

- Brenner, J. C., & Davis, J. G. (2012). Transboundary conservation across scales: A world-regional inventory and a local case study from the United States–Mexico border. Journal of the Southwest, 54(3), 499–519. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsw.2012.0023

- Büscher, B. (2013). Transforming the frontier: Peace parks and the politics of neoliberal conservation in Southern Africa. Duke University Press.

- Büscher, B., & Fletcher, R. (2018). Under pressure: Conceptualising political ecologies of green wars. Conservation and Society, 16(2), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.4103/cs.cs_18_1

- Carbonell, F., & Torrealba, I. (2008). La conservación integral alternativa desde el Sur: Una visión diferente de la conservación. Polis (Santiago), 7, 217–242. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-65682008000200016

- Chandler, D., Müller, F., & Rothe, D. (2021). International relations in the anthropocene: New agendas, New agencies and New approaches. Palgrave McMillan.

- Cocks, M., & Dold, T. (2012). Perceptions and values of local landscapes: Implications for the conservation of biocultural diversity and intangible heritage. In B. Arts, S. van Bommel, M. Ros-Tonen, & G. Verschoor (Eds.), Forest-people interfaces: Understanding community forestry and biocultural diversity (pp. 167–180). Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- Conca, K., & Dabelko, G. (2002). Environmental peacemaking. WWC Press.

- Corlett, R., & Primack, R. (2008). Tropical rainforest conservation: A global perspective. In W. Carson, & S. Schnitzer (Eds.), Tropical Forest community ecology (pp. 442–457). Blackwell Publishing.

- De la Torre, A., Camacho, G., Arroyo-Gerala, P., Cassaigne, I., Rivero, M., Campos-Arceiz, A. (2021). A cost-effective approach to mitigate conflict between ranchers and large predators: A case study with jaguars in the Mayan forest. Biological Conservation, 256, 109066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109066

- De Vos, J. (1996). Oro Verde: La conquista de la Selva Lacandona por los madereros tabasqueños 1822–1949. FCE.

- Del Bosque, I., Fernández, C., Martín-Forero, L., & Pérez, E. (2012). Los sistemas de información geográfica y la Investigación en Ciencias Humanas y Sociales. CECEL-CSIC.

- Dorsey, K. (2009). The Dawn of Conservation Diplomacy: The U.S.-Canadian Wildlife Protection treaties in the progressive Era. University of Washington Press.

- Dudley, N., & Stolton, S. (2020). Leaving space for nature: The critical role of area-based conservation. Routledge.

- Duffy, R. (2000). Shadow players: Ecotourism development, corruption and state politics in Belize. Third World Quarterly, 21(3), 549–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/713701038

- Duffy, R. (2006). The potential and pitfalls of global environmental governance: The politics of transfrontier conservation areas in Southern Africa. Political Geography, 25(1), 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2005.08.001

- Erg, B., Groves, C., McKinney, M., Michel, T. R., Phillips, A., Schoon, M. L., Vasilijevic, M., & Zunckel, K. (2015). Transboundary Conservation: A systematic and integrated approach. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series, 23. Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

- Finley-Brook, M. (2007). Green neoliberal space: The Mesoamerican biological corridor. Journal of Latin American Geography, 6(1), 101–124. https://doi.org/10.1353/lag.2007.0000

- Ford, A., & Nigh, R. (2016). The Maya forest garden: Eight millennia of sustainable cultivation of the tropical woodlands. Routledge.

- Freitas, F. (2017). Ordering the borderland: Settlement and removal in the Iguazú national park, Brazil, 1940s-1970s. In W. Von Hardenberg, M. Kelly, C. Leal, & E. Wakild (Eds.), The nature state: Rethinking the history of conservation (pp. 158–175). Routledge.

- Garfield, S. (2012). The Brazilian Amazon and the Transnational Environment 1940-1990. In E. Bsumek, D. Kinkela, & M. Atwood (Eds.), Nation-States and Global Environment: New Approaches to International Environmental history (pp. 228–251). Oxford University Press.

- Graf von Hardenberg, W., Kelly, M., Leal, C., & Wakild, E. (2017). The nature state: Rethinking the history of conservation. Routledge.

- Harris, L., & Hazen, H. (2006). Power of maps: (counter) mapping for conservation. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 4(1), 99–130. https://doi.org/10.14288/1.0357973

- Kauffer, E. (2018). Cuencas transfronterizas: La apertura de la presa del nacionalismo metodológico. CIESAS.

- Kauffer, E., Laako, H., Pliego, E., Fuentes, J., Cervantes, M., Mesa, A., Ramos, D., Urbina, M., Díaz, M., Andrade, D. (2019). Las fronteras de la cuenca del río Usumacinta [research report]. CONACYT.

- King, B., & Wilcox, S. (2008). Peace parks and jaguar trails: Transboundary conservation in a globalizing world. GeoJournal, 71(4), 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-008-9158-4

- Kütting, G. (2007). Environment, development and the global perspective: From critical security to critical globalization. Nature and Culture, 2(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.3167/nc.2007.020104

- Laako, H. (2016). Decolonizing vision on borderlands: The Mexican southern borderlands in critical review. Globalizations, 13(2), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2015.1076986

- Laako, H., & Kauffer, E. (2021). Conservation in the frontier: Negotiating ownerships of nature at the southern Mexican border. Journal of Latin American Geography, 20(3), 40–69. https://doi.org/10.1353/lag.2021.0049

- Laako, H., & Kauffer, E. (2022). Between colonising waters and extracting forest fronts: Entangled eco-frontiers in the Usumacinta river basin. Political Geography, 96, 102566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102566

- Lehtinen, A. (2006). Postcolonialism, multitude and the politics of nature: On the changing Geographies of the European north. University Press of America.

- Lewis, K. (2008). Negotiating for Nature: Conservation Diplomacy and the Convention on Nature Protection and Wildlife Preservation in the Western Hemisphere, 1929-1976. Doctoral dissertation 427, Durham: University of New Hampshire.

- List, R., Rodríguez, P., Pelz-Serrano, K., Benítez-Malvido, J., & Lobato, J. M. (2017). La conservación en México: Exploración de logros, retos y perspectivas desde la ecología terrestre. Revista mexicana de biodiversidad, 88, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2017.10.007

- Marchese, C. (2015). Biodiversity hotspots: A shortcut for a more complicated concept. Global Ecology and Conservation, 3, 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2014.12.008

- Marijnen, E., De Vries, L., & Duffy, R. (2020). Conservation in violent environments: Introduction to a special issue on the political ecology of conservation amidst violent conflict. Political Geography, 87, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102253

- Martínez, J. (2017). Moral ecology of a forest: The nature industry and Maya post-conservation. University of Arizona Press.

- Martos, L. (2010). Definiendo lo maya. Fundación Cultural Armella Spitalier.

- Medina, L. (2020). Pouvoir, préservation, prédation. Les frontières d’Amérique latine témoins d’un continent sous tensions. L’EspacePolitique: Online Journal of Political Geography and Geopolitics, 42(3). https://doi.org/10.4000/espacepolitique.9424

- Mendoza, M., Fletcher, R., Holmes, G., Ogden, L. A., & Schaeffer, C. (2017). The Patagonian imaginary: Natural resources and global capitalism at the far end of the world. Journal of Latin American Geography, 16(2), 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1353/lag.2017.0023

- Miller, S. (2007). An environmental history of Latin America. Cambridge University Press.

- Mittermeier, R. A., Robles Gil, P., Kormos, C. F., Mittermeier, C. G., & Sandwith, T. (2005). Transboundary conservation: A new vision for protected areas, 333(782) T772t. CEMEX.

- Nations, J. (2006). The Maya tropical forest: People, parks and ancient cities. University of Texas Press.

- Oehling, A. (2015). El artículo X del tratado de Utrecht de 1713: Interpretación interesada y esquema de consecuencias jurídico-políticas para españa. Revista de Estudios Políticos, 168(168), 199–234. https://doi.org/10.18042/cepc/rep.168.07

- Olivera, M. (2008). Espacios diversos, historia en común. México, Guatemala y Belice. La construcción de una frontera. LiminaR, 6(1), 153–156. https://doi.org/10.29043/liminar.v6i1.273

- Peluso, N. L., & Vandergeest, P. (2020). Writing political forests. Antipode: A Radical Journal of Geography, 52(4), 1083–1103. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2011.560064

- Peluso, N., & Lund, C. (2013). New frontiers of land control. Routlegde.

- Peluso, N., & Vandergeest, P. (2011). Political ecologies of War and forests: Counterinsurgencies and the making of national natures. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 101(3), 587–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2011.560064

- Pinkus, M. (2010). Entre la selva y el río: Planes internacionales y políticas públicas en Tabasco. La globalización del Cañón de Usumacinta. Plaza y Valdés.

- Price, S. (2003). War and Tropical Forests: conservation in Areas of Armed conflict. Haworth Press.

- Primack, R., Bray, D., Galletti, H., & Ponciano, I. (1999). Timber, tourists and temples: Conservation and development in the Maya forest of Belize, Guatemala and Mexico. Island Press.

- Ramutsindela, M. (2014). Cartographies of nature: How nature conservation animates borders. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Scott, J. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press.

- Stevis, D. (2017). International relations and the study of global environmental politics: Past and present. In R. Denemark, & R. Marlin-Bennett (Eds.), The international Studies encyclopedia (pp.4476–4507). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Susskind, E., & Ali, S. (2015). Environmental diplomacy: Negotiating more effective global agreements. Oxford University Press.

- Toledo, T., Purata, S., & Peters, C. M. (2009). Regeneration of commercial tree species in a logged forest in the Selva Maya, Mexico. Forest Ecology and Management, 258(11), 2481–2489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2009.08.033

- Toussaint, M. (2009). Entre los vecinos y los imperios: el papel de Belice en la geopolítica regional. Tzintzun, (50), 105–128.

- Trogish, L. (2021). Geographies of fear – The everyday (geo)politics of ‘green’ violence and militarization in the intended transboundary Virunga Conservation Area. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 122, 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.03.003

- Wakild, E. (2017). Protecting Patagonia: Science, conservation and the pre-history of the nature state on a South American frontier. In W. G. von Hardenberg, M. Kelly, C. Leal, & E. Wakild (Eds.), The nature state: Rethinking the history of conservation (pp. 37–54). Routledge.

- Wolmer, W. (2003). Transboundary Protected Area Governance: Tensions and Paradoxes. Presentation at Workshop on Transboundary Protected Areas in the Governance Stream of the 5th. Durban, South Africa: World Parks Congress, 12-13 Sept. 2003.

- Ybarra, M. (2018). Green wars: Conservation and decolonization in the Maya forest. University of California Press.