ABSTRACT

In the decisive responses to protest movements in Ethiopia and Cameroon between 2015 and 2018, state control and repression were facilitated by colonial-corporate digital infrastructures and neo-imperial techno-political configurations. In both cases, resistance was met with pervasive state-initiated and corporate-sanctioned internet shutdowns and disruptions. I situate these techno-political practices within the longue durée of coloniality to argue that the state suspension of internet connectivity is a form of infrastructural harm; an intentional violence made socially and structurally possible by the colonial configurations of infrastructure. My analysis draws from five years of digital ethnography and ethnographic fieldwork, including 13 months in Jimma, Ethiopia and nine months in Yaoundé, Cameroon. I mobilize a decolonial praxis that unmasks practices of authoritarian control within global racial coloniality, and seeks to foster cross-fertilizations of struggle and resistance praxis.

Introduction

The problem was that [First Lady] Chantal Biya was receiving too many disturbing prank calls on her phone. Now we all register our SIM cards. Plus, it will discourage phone theft if everyone’s phone is registered to their national ID card.

These words were spoken by my friend, Emmanuel, one afternoon in October 2011, as we queued in the artificially cold, white-tiled office space of Orange, the French telecommunications company, at a busy intersection in Yaoundé. We were there to enrol my phone’s Subscriber Identity Module (SIM) card, as required by Cameroon’s recently-passed SIM card registration legislation. All existing and future subscribers of pre-paid telephone SIM cards (issued by private companies) must register their personal information prior to the activation of their device, a process known as ‘whitelisting’. According to Emmanuel and others, the law – which established a national database containing the details of every mobile user in Cameroon – was a fairly innocuous reaction to the supposed telephone harassment of the First Lady by unknown mischief-makers. (As some of my Cameroonian friends observed, even if this banal drama were true, it hardly justified a response at this scale). Government spokespersons claimed that the law would deter Cameroon’s problem with phone thefts, although these persisted. What the new SIM registration law did achieve was to strengthen the groundwork for a surveillance infrastructure that would further entrench post-colonial security operations in the country.

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, a wave of digital surveillance legislation was rolled out across countries on the African continent. The above episode illustrates the connection between post-9/11 security regimes and complex place-based political geographies in which moral logics are used to validate intensified state surveillance techniques and, ultimately, to seek to ‘extract compliance’ from subjects (Galava, Citation2019, p. 261). It also displays the collusion of non-state actors and corporations in the adoption and enforcement of these logics of control, even when these infrastructural interruptions do not serve an immediate profit agenda. Like Cameroon, Ethiopia implemented mandatory SIM registration to facilitate domestic communications surveillance and monitoring. The Ethiopian government also maintained information-sharing arrangements with the United States military, and a partnership with the Chinese telecommunications giant, Huawei, which provided a sizeable modular data centre in Addis Ababa for the state-owned Ethio Telecom.Footnote1 Contemporary power struggles are increasingly reflective of material crises within authoritarian and racial capitalism – and these power contestations frequently play out and are ‘anchored in infrastructure’ (Cowen, Citation2017, n.p.), including digital infrastructure.

My research focuses on the convergence of transregional histories of repression, security, and resistance as they manifest in the colonial configurations of infrastructure. To that end, I examine how two significant contemporary resistance movements were confronted with the most pervasive state-initiated Internet blackouts on the African continent at the time: the 2016, 2017, and 2018 wave of Internet disruptions in Ethiopia and the 2017/2018 Internet blackouts in Cameroon. The latter lasted from 17 January 2017 to 20 April 2017 and again from 1 October 2017 to 28 February 2018, for a total of 240 days. In this article, I bring together scholarship on the colonial logics of infrastructure (including work on digital and data colonialism) with the imperatives offered by decolonial political geography to understand how authoritarian formulations of power instrumentalize digital spaces (a phenomenon sometimes referred to as ‘digital authoritarianism’; Ayalew, Citation2022Footnote2). Sustained internet shutdowns in recent years (including in Chad, India, Togo, Mali, Myanmar) have been described as forms of ‘digital siege’ in which the state and the political-economic elite seek to ‘wear down public dissent under the guise of pacifying volatile situations’ (Rydzak, Citation2018, p. 13). State-initiated shutdowns are often carried out pre-emptively against armed groups (Gohdes, Citation2015); used as forms of low-intensity ‘repression technology’ in zones of civil conflict (Gohdes, Citation2018); or deployed in anticipation of electoral unrest, real, or contrived (Freyburg & Garbe, Citation2018).

Media and state narratives have been tightly controlled by both governments, through the targeted intimidation and management of journalists and academics, and massive state public relations campaigns, typically outsourced to Western firms (on Biya’s PR docket in Cameroon, see Ndongmo, Citation2021; on the Ethiopian PR-driven journalism model, see Mohammed, Citation2021). In this context, social media and digital platforms afford a collective cosmos for overt and covert provocations and resistance by activists and artists in Cameroon (Anyefru, Citation2008), Ethiopia, and their diasporas; what Téwodros Workneh (Citation2021) calls ‘outrage communication’. The careful occupation of the digital commons throughout both street-based movements was a strategic form of non-violent dissent in the face of chronic violence and criminalization of street protests (Tufekci, Citation2017). Within a colonial social context of fear, anxiety, and uncertainty about physical protests, these digital spaces are important resources.Footnote3

When confronting the Ambazonia and Qeerroo/Qarree resistance movements, the governments of Cameroon and Ethiopia respectively imposed large-scale network shutdowns, as well as focused website blocking and throttling (or slowing down of specific websites). They conducted online surveillance of activists and their families, mobilizing a patchwork of fluctuating colonial practices from disappearing, beating, and killing activists, to surveillance and intimidation, to arrest and prosecution, to dismissing dissenters as terrorists and ‘cyber-terrorists’, and more. The (planned) incapacitation of the Internet compounded patterns of infrastructurally-driven repression that are rooted in colonial practice.

I examine the larger political context for digital infrastructural harm, including a proliferation of anti-terrorism legislation and digital tools of control and domination in the wake of the ‘Arab Spring’ and North African uprisings, and the longer, slower configurations of corporate extraction that often enable repressive practices. Technology provided by corporate actors such as Orange or MTN, for example in Cameroon, facilitated the state’s authority and control over telecommunications, and hence its capacity for digital repression and surveillance. My analysis of the practices of infrastructural harm reveals transitory frictions between authoritarian (state) and corporate (telecommunications) imperatives within global coloniality. In both cases, the immediate ambitions of the authoritarian state to respond to political protest took precedent over short-term corporate profit. This finding is suggestive of both the usefulness and the predominance of authoritarian state formulations within global racial coloniality.

The decolonial turn in political geography ‘deconstructs the idea of a ‘post’ colonial’ (Jazeel, Citation2017; Naylor et al., Citation2018, p. 199) and is grounded in the ambition to unmask the practices, logics, and forms of coloniality (Radcliffe & Radhuber, Citation2020), while fostering pluriversal and trans-epistemic dialogues of/for subversion, disobedience, and liberation (Daley & Murrey, Citation2022). Working within this active aspiration, I mobilize a decolonial and transregional critique of infrastructural harm and its intersection with other forms of acute and cyclical colonial repression – including more normalized forms of infrastructural violence (as I discuss below) – within the longue durée of coloniality in Cameroon and Ethiopia.

A decolonial lens allows us to critique some of the shared technologies and practices of coloniality/modernity while ‘build[ing] understandings’ of struggle that ‘cross geopolitical locations and colonial differences’ (Mignolo & Walsh, Citation2018, p. 1). I am interested in understanding the effects of Internet suspension on activists and communities of struggle, and the inventiveness with which people resist and circumvent the repressive logics of such forms of digital infrastructural harm (and attendant forms of systemic violence). Political activists mobilized strategies that subvert state efforts to block the Internet. Indeed, for the activists, I spoke with and many who I followed online, the internet blackouts were never characterized as ‘successful’. These instances of digital infrastructural harm in Cameroon and Ethiopia re-emphasize that colonial logics are never fully triumphant. People make do; they endure, dissent, and resist.

The article proceeds as follows: I outline the importance of decolonial praxis to studies of digital repression and geographies of struggle and resistance. Next, I situate my research within this framework to uncover the tangled colonial roots of infrastructures (including digital infrastructures), their potential for repressive deployment by post-colonial governments, and how they are subverted and/or (re)imagined by their ‘targets’. I articulate working distinctions between infrastructural harm and infrastructural violence in state and corporate practices, thus contributing to the burgeoning scholarship on digital politics and infrastructures outside of Euro-American contexts. I argue that the planned and targeted suspension of Internet connectivity is an intentional form of harm (to infrastructure and the people who depend upon it) that is made socially and structurally possible by its colonial configurations and within a global capitalist system condoning post-colonial authoritarian states. I weave together activist narratives in Cameroon and Ethiopia, establishing shared experiences of digital infrastructural harm, and demonstrating that activists overcome such forms of harm.

Decolonial praxis for researching resistance and infrastructural harm

I use transregional, multi-scalar decolonial praxis to examine and connect place-based and digital resistances against colonially-derived technologies of repression and infrastructural harm. An important body of scholarship looks at concrete practices of research against and beyond coloniality, including an awareness of research-as-extraction (Smith, Citation2012), or what has been termed elsewhere the ‘piratic method’ (Tilley, Citation2017) and, in Cameroon, ‘the language of the mouth’ to differentiate inactive/Western knowledge from meaningfully active/embodied knowledges (Murrey, Citation2017). A decolonial imperative is to liberate and celebrate knowledges beyond the colonial matrix of power, while remaining alert to the permanently shifting forms, manoeuvres, and characteristics of colonial regimes of order (Daley & Murrey, Citation2022). As such, decolonial scholarship centres the needs and dynamic experiences of everyday people while exposing the perpetually shifting misappropriations, actions, and practices of elites.

Determined to engage in the (im)possibilities of decolonial research (Icaza, Citation2022), I applied diverse, transdisciplinary approaches to the study of repression, infrastructural harm, and resistance struggles in transregional settings. Decoloniality is a complex, process-based, embodied praxis (Zaragocin & Caretta, Citation2021; Icaza, Citation2022); it is also iterative, and each conversation and encounter offered fresh dynamics for me to (re)consider and challenged my academic frameworks anew.Footnote4 Through embodied and decolonial ethnographic presence, I sought to stay attuned to both the urgencies of the lives of my activist friends and the ever-resonant legacies of ethnography as a colonial science (Uddin, Citation2011) within the ‘colonial university’ (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2021; Murrey & Tesfahun, Citation2019). My research was conducted over a five-year period between 2015 and 2020, during which I focused on politics and power in conflict between the state and activists on- and off-line. I engaged in face-to-face conversations and digital exchanges with 31 political activists and digital advocates in Cameroon and Ethiopia. I lived and stayed in Yaoundé, Cameroon for nine months over four different trips in 2017, 2018, and 2019, and Jimma, Ethiopia from August 2015 to August 2016.

Through this research, I also engaged in digital ethnography, the relatively newer study of digital places, cultures, and communities, which involves active, extended, and systematic exchanges with and participation within those communities (Postill & Pink, Citation2012; Bonilla & Rosa, Citation2015). Digital ethnography has highlighted the unique social worlds of digital communities, and is especially valuable for connecting with these communities in circumstances that include intense state repression, conflict (Gohdes, Citation2018), and COVID-19 lockdowns. Rather than engaging with the digital as a discrete community or dislocated space (see also Mutsvairo & Wright, Citation2019, p. 281), I conducted a multi-sited ethnographic practice that remains conscious of the ways in which digital communities transect, intersect, and contradict each other within wider political practices. Drawing upon a technique that dahah boyd (Citation2008, p. 145) refers to as ‘articulated participation’, I engaged in re-posting, re-tweeting, un/liking, commenting, and sharing to make my presence explicit within digital communities. I watched hundreds of hours of Facebook Live streaming of protest events, occupations, and marches and followed their subsequent commentaries. I scrolled through Twitter posts, ‘liking’ and archiving those with key hashtags or moments in struggle; and engaged in one-on-one and group WhatsApp communications with activists. I witnessed, interacted with, and archived thousands of tweets, posts, messages, and emails. My intent was not to code data points, but rather to reflect on the tapestry of activist experiences, rumours, and perspectives on state hegemony that were shared on- and offline.

This digital sourcing was inevitably partial, structured by and through state and corporate censorship and algorithmic tracking (this was only partially mitigated by using the non-tracking browser DuckDuckGo). It was also shaped by my own subjectivity within the information-heavy space of social media, where I spent more time following up on and tracing the provenance of stories, people, and posts I found personally intriguing. Finally, my digital research reflected my familiarity with particular platforms, and my linguistic aptitudes. My work in Cameroon is multilingual, as I read and speak French, English, and Camfranglais (a vernacular spoken widely by Cameroonians in informal settings), and can read Pidgin. My work in Ethiopia was more linguistically constrained, since I relied on language software to read posts in Amharic, and translations to understand posts in Afaan Oromo/Oromiffa.

Given that the global colonial matrix of power confines and configures ‘the analogue-digital dimensions of life’ (Matute & González, Citation2021) beyond the boundaries of the nation state, a transnational approach can powerfully reveal shared authoritarian practices and mechanisms of repression. Drawing on postcolonial and decolonial critiques of digital geographies and emerging polymedia praxis, I engaged in what Postill and Pink (Citation2012) refer to as ‘media switching’ to maintain dynamic digital social relationships across time and space, while remaining conscious of how digital spaces compound rather than diffuse existing social inequalities and colonial power logics. Such critiques offer insights into other possible worlds (Icaza, Citation2022), including the political stakes of infrastructure, and potential solutions to contemporary socio-economic problems that go beyond those supported by national and corporate elites within the global matrix of power.

Much like ethnography itself, digital ethnography is susceptible to colonial research logics, including the terra nullius thinking associated with conquest. Bruce Mutsvairo and Kate Wright (Citation2019, p. 279), for example, critique the new ‘kind of ‘scramble for Africa’’ in digital studies of African societies (see also Schoon et al., Citation2020). Docot (Citation2021, p. 690) calls for rigorous ‘self-criticism’ in the face of researcher access to high-tech capacity and new digital tools that can ‘dangerously reproduce colonialist’s adventurism and obsessions with charting the unknown and rendering the Other readable and exploitable’.

Research within communities of struggle is time-intensive and deliberately slow. Relational and decolonial research demands considerable emotional and imaginative work (Bringel & Dominguez, Citation2015) to bring together divergent communities in struggle and ‘ecologies of knowledge’ (de Sousa Santos, Citation2006), while remaining alert to the pitfalls of Western scholarship merely conducted under the guise of ‘decolonisation’ or decoloniality (Curley et al., Citation2022; Esson et al., Citation2017; Noxolo, Citation2017; Tuck & Yang, Citation2012). Decolonial geographies refuse the wilful blindness of whiteness (Faria & Mollett, Citation2014) and establish a loci of enunciation from the body and with the people in the communities where we work (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2021) – that is, not only an attention to the location of knowing but also the political and power consequences and accountabilities of our knowledges (Curley et al., Citation2022). A decolonial political geography of infrastructural harm seeks to work within knowledges that assist in empowering people in pursuing decolonial presents and futures.

Situating digital infrastructural harm within authoritarianism, within global coloniality

While formal and juridical colonization ended in Cameroon in 1960 and Ethiopia was never officially colonized,Footnote5 each country remains entangled within global coloniality and disadvantaged by racial capitalism. A primary focus of my research is the wide range of infrastructural harms, violence, and repressions that are practiced together – in harmony and in ambiguity – by authoritarian states and within global racial capitalism. Within this interplay, internet and telecommunications structures have become inseparable from histories and practices of contemporary state violence. These synergies create new capacities for arbitrary displays of state authority, the circulation of propaganda, and anti-activist measures, including the presentation of police and military killings and maiming(s) as digital spectacles, to ‘heighten fear and suppress dissent’ (Docot, Citation2021, p. 690). Recent work on popular resistance and social movements has mapped a relative decline in the immediate ‘success’ of nonviolent protests in the past decade (Chenoweth, Citation2020), particularly in the context of ‘authoritarian adaptation’ (Deshayes et al., Citation2022), during which digital tools and infrastructures have been controlled and deployed by governments. This phenomenon has engendered critical work on ‘digital authoritarianism’ in which ‘states … co-opt technological advances to enable online and offline repressive measures’ (Shaheed & Greenacre, Citation2021, p. 8). Digital infrastructures provide states flexible techniques to undermine, threaten and sabotage resistance movements (Docot, Citation2021; Shires, Citation2021). Such authoritarian trends have likely been amplified in the wake of COVID-19 (Aidi, Citation2021; Shaheed & Greenacre, Citation2021), in tandem with an intensification of infrastructure-led, developmentalist ideology in postcolonial societies (Akhter et al., Citation2022). Authoritarian governance increasingly materializes through ‘infrastructural modalities of power’ (von Schnitzler, Citation2016, p. 12). These modalities of power include the spectacularized deployment of mega infrastructural projects as celebratory extensions of state modernity, even as such possibility is ‘immediately undone by its devastating materiality’: the considerable disquiet, despair, and ruination of mega infrastructure projects (Lesutis Citation2022, p. 2). As Cowen (Citation2017, n.p.) explains, ‘The story of infrastructure is … one of disconnection, containment, and dispossession’.

The coloniality of infrastructure

The multifaceted colonial histories of infrastructure (Mbembe & Roitman, Citation1995; van der Straeten & Hasenöhrl, Citation2016) and their rejection or adoption by settler colonial and post-colonial governments have been well documented (Curley, Citation2021; Enns & Bersaglio, Citation2020). This includes work on the material and epistemic coloniality of infrastructure (Davies, Citation2021), the racializing colonial logics used to promote large-scale infrastructure projects in African countries (Murrey & Jackson, Citation2020), and the ways in which digital infrastructures embed and reflect coloniality (Kwet, Citation2019), ‘data colonialism’ (Couldry & Mejias, Citation2019) and ‘#techno-colonialism’ (Matute & González, Citation2021). Colonial projects have relied on infrastructures which, in Curley’s terms (Citation2021:, p. 400) ‘are both the physical and political structure of colonialism. Without infrastructure, colonialism is made difficult, if not impossible’. Infrastructures in the colonies facilitated large-scale labour and resource extraction while maintaining colonial biopolitical and territorial domination (von Schnitzler, Citation2016). Their implementation was capricious, ‘arriv[ing] in some places while [being] denied in others’ (Curley, Citation2021, p. 388). For Curley (Citation2021, p. 388), the unevenness of this dispersal of material and technology fostered colonial difference and ‘establish[ed] the conditions for future dispossession, displacement, and marginalization’. Infrastructures were ‘often primarily designed to prevent the emergence of a (counter)public [and they] often followed a security or military logic’ (italics added, von Schnitzler, Citation2016, p. 15).

Colonial administrators enacted policies aimed at the targeted destruction of vital functioning infrastructure for the purposes of population control and containment. The French, when forced to depart Guinea in 1958 in the wake of anti-colonial protest, destroyed schools, bridges, tractors, and books; two years later, departing French colonists forced 14 other African governments – Cameroon included – to pay reparations in exchange for post-colonial sovereignty and unharmed infrastructure at independence (Pigeaud & Samba Sylla Citation2021 ). The neo-imperial counterinsurgency military strategies of the early twenty-first Century, led by the United States, demonstrated a preference for ‘precision weaponry’ capable of isolating destruction to contained zones and infrastructures in a process known as ‘duress bombing’. Jasbir K. Puar (Citation2017) tracks the intensification of this colonial practice through the Israeli state’s deliberate maiming of bodies and infrastructures in occupied Palestine as a productive violence.

Many of these same logics remain embedded within post-colonial infrastructures that facilitate extraction, dispossession, and absolute state authority. Colonial logics of repression are revealed in how infrastructure is managed and policed in authoritarian post-colonial societies. The coloniality of Internet infrastructure is reflected through its design structure, including the imperative to facilitate resource (data) extraction and to foster biopolitical and territorial domination (Couldry & Mejias, Citation2019). This coloniality is further reflected through the uneven-ness of spatial distribution (Curley, Citation2021) and Internet access (Schoon et al., Citation2020), as well as the security and military logics that would prevent dissent and effect surveillance (Kwet, Citation2019; Ayalew, Citation2022). Infrastructures are not ‘neutral conduits’, but rather ‘political actions … embedded within technical forms’ (von Schnitzler, Citation2016, pp. 9–10). A decolonial political geographical framework enables us to analyse infrastructural harm as it relates to bureaucratic and digital violence(s), while exposing its inadequacies, failings, and subversions.

Infrastructural violence and infrastructural harm

Infrastructural violence refers to the destruction and transformation of place, landscape, and intraspecies lives for the purposes of infrastructural ‘development’ and modernization. This includes routinized acts of planning, building, dismembering, or abandoning water, energy, transport, and food systems infrastructures, and the uneven allocation and/or denial of infrastructures because of colonial difference (e.g. Curley, Citation2021). Rodgers and O’Neill (Citation2012, p. 404) argue that infrastructure is more than a

material embodiment of violence (structural or otherwise), but often [is] its instrumental medium, insofar as the material organisation and form of a landscape not only reflect but also reinforce social orders, thereby becoming a contributing factor to reoccurring forms of harm.

Infrastructural violence results from systemic failures of political will, social priority, and infrastructural materiality, each of which is shaped by the histories of coloniality and racial capitalist violence.

The infrastructural harm at stake here is different from the two categorizations of infrastructural violence offered by Rodgers and O’Neill (Citation2012), in which they distinguish between ‘actively’ and purposefully violent infrastructures, and ‘passively’ violent infrastructures, which cause damage through their processes, limitations, absences, and failures (see also Datta & Ahmed, Citation2020). The violence I refer to here is the intentional sabotage of otherwise functioning infrastructure by the state, which I understand to be a double violence: first, in the material harms caused by the deprivation of usage and second, in the denial that violence has occurred. Such brazen denial (by the state) is galling and dehumanizing, and results in psychological and communal harm.

I trace non-linear convergences between struggle and repression in Cameroon and Ethiopia in order to strengthen our understanding of the multiple dynamics of digital infrastructural harm. A transregional decolonial praxis allows us to deliberate upon the shifting parameters of colonialized power in Africa and in the university (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2021), as this work necessarily unravels and demystifies Eurocentric notions of securitization (Sabaratnam, Citation2017; Daley, Citation2018), and post-colonial patterns of exclusion and repression (e.g. Amar, Citation2013). This perspective also fosters a circular, relational, and plural South-South (or Pan-African) framework through which we might imagine political struggle otherwise (Icaza, Citation2022) and through which ‘claims for the protection’ of decolonial infrastructural systems might be made (Cowen, Citation2017, n.p.), while remaining attentive to a rich plurality of epistemes and experiences (Daley & Murrey, Citation2022).

The Qeerroo/Qarree resistance struggle, Ethiopia, 2015–2019

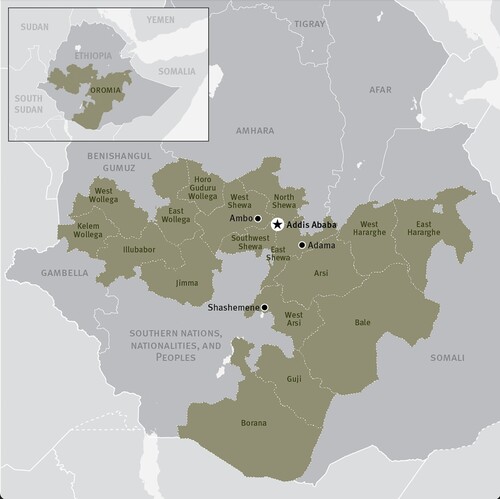

Shared grievances across the Oromia Region (see ) gained momentum in 2015, in part in response to the planned administrative expansion of Addis Ababa, which would integrate 1.1 million hectares of land then being administered, under Ethiopia’s federalized system of governance, by the Oromia National Regional State (ONRS). For Oromo youth protestors (known as Qeerroo/Qarree), the now defunct Addis Ababa Master Plan was a ‘Master Killer’ (Wayessa, Citation2019) that would bring 40–100 km of ONRS land under the governance of Addis Ababa. As a result, millions of Oromo farmers would be evicted and the governing and schooling language would shift from Afaan Oromo/Oromiffa to Amharic, a politically inflammatory change given a historical context of linguistic marginalization. (In 1941, Haile Selassie banned the Oromo language in governing procedures and schools, and this ban remained in place until 1991). In February 2016, Open Democracy reported that the Master Plan:

… possessed all the deficiencies of large development operations in Ethiopia: opacity and confusion, with documents of uncertain status released in dribs and drabs, thus a lack of clarity even about the respective roles of Addis Ababa municipality and the Oromia authorities in the area concerned; a centralising, top-down approach, with no consultation of the people. (See also Cochrane & Mandefro, Citation2019)

Community figureheads convened meetings with Bajaj taxi drivers to demand that they stop providing transport to protestors. Assemblies were held with government officials and Ethiopian teaching staff, warning of the dire consequences of participating in riots or holding events that might be seen as sympathetic to the movement (see Murrey & Tesfahun, Citation2019). With life on campus enveloped by acute political tension and daily violence, JU faculty spoke privately about the necessity to protect themselves through ‘self-censorship’ (multiple conversations from author fieldnotes, Jimma, December. 2015–July 2016). Student dissent continued, however; days after the Department of Law and Governance erected a large, illuminated fibreglass sign with the university and departmental logo and titles in English and Amharic rather than Oromiffa, students expressed their outrage by busting it open with rocks and stones.

Violent clashes occurred between protesters and security forces on Jimma’s Agricultural Campus. In January 2016, a bomb was thrown at JU’s Keto Technology Campus (activists claimed the bomb was a false flag, intended to malign the movement; author fieldnotes). The military again intervened, killing two students and injuring several others. The state dismissed protestors’ accounts of killing and injury, calling the youth ‘terrorists’ and claiming elite and outside forces were manipulating them. Reports on the number of arrests were disputed, with claims of conspiracy on both sides. The JU main campus remained occupied by military personnel for the rest of the academic year.

In both the Oromia Region and Anglophone Cameroon, the protests of 2015/2016 exemplified long histories of state violence in response to nonviolent direct action and political resistance. In 2014, for example, an estimated 500 protestors were killed by security forces in Oromia (Amnesty International 2014). According to one protestor, ‘the language of Ethiopian prisons is Oromiffa’ (interview with activist, March 2016). Social media campaigns gained popularity, including #OromoPoliticalPrisoners, #FreeAllOromo, #Oromo and #Qeerroo (see and ), and ultimately helped to propel the appointment of Abiy Ahmed as Prime Minister in 2018 (following the resignation of Hailemariam Desalegn; Forsén & Tronvoll, Citation2021). Ahmed’s appointment temporarily calmed tensions and activated a shared sense of expectation and optimism for Ethiopian youth and Qeerroo/Qarree activists – but one that was unfortunately short-lived (interview with activist H.B. in Addis Ababa, September 2019).

The Anglophone resistance struggle, Cameroon, 2016–2019

In October 2016, in the towns of Bamenda, Buea, Limbe, and others in the Anglophone/English-speaking regions of Southwest and Northwest Cameroon, a trade union of teachers and lawyers (the Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium) staged peaceful protests demanding salary increases and a discontinuation of the requirement that education and legal processes in the predominantly English-speaking region be conducted in French (see ).Footnote7 United by ‘the deep perception that they have been purposely marginalized over the years’Footnote8 (Pommerolle & Heungoup, Citation2017, p. 528), they were soon joined en masse by students, Bendskiners (motorbike taxi drivers), transport workers, and others in a long-established form of Cameroonian protest: massive boycotts that effectively turn entire cities into ghost towns, or les villes mortes. This style of protest – ghost-towning – has been prevalent in Cameroon since the early 1990s (Amin, Citation2013).

When the ruling party, Paul Biya’s RDPC/CPDM (Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement), announced it would hold a ‘peace parade’ in Bamenda on 8 December 2016 – a blatant attempt to stifle and appropriate the months-long series of protests – people responded by blocking roadways and heckling RDPC supporters. As with previous, predominantly peaceful demonstrations, the government retaliated with extreme force.Footnote9 This time, they used tear gas, water cannons, bully clubs, and live ammunition against protestors. Several dozen were arrested, and movement leaders were disappeared, including the digital activist Jean-Claude Agbortem. Biya’s forces killed five people, two of whom were shot in the back. No charges were brought for these deaths (Walla, Citation2017).

Subsequent protests grew in size, and people were outraged about arbitrary detainments, beatings, and both targeted and indiscriminate killings of protestors and bystanders. On 13 January 2017, soldiers opened fire on a crowd of peaceful protestors, injuring three. Ongoing negotiations were halted, and protestors demanded that the government free all political prisoners. In retaliation, the government suspended the Internet for the five million people living in the two English-speaking regions for three consecutive months, or 93 days, from January to April 2017. The stoppage did not cease the deluge of video footage of state violence from circulating online.

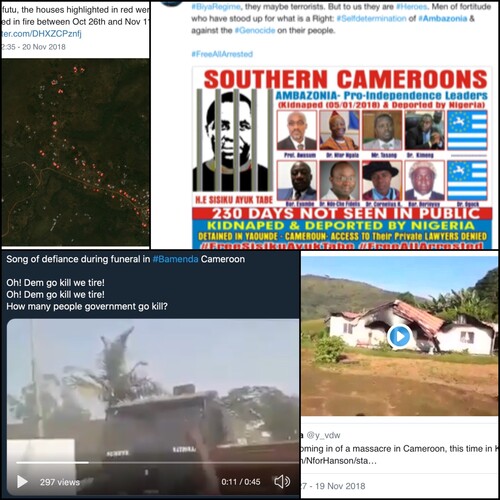

Indeed, security personnel filmed their own heavily armed patrols and circulated the videos on Facebook and Twitter, deliberately showcasing grim-faced and heavily armed troops shooting indiscriminately into buildings from the rears of 4 × 4s, in broad daylight. Calculated to demonstrate the state’s might, these videos instilled fear and rage, triggering avalanches of outrage-laden commentary online. Instances of serious violence by security forces were captured on video by onlookers and circulated widely via YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter under #AnglophoneStruggle, #Ambazonia, #FreeAllArrested, #JusticeInCameroon, #CameroonGenocide, and more. Security forces are shown intimidating, disrobing, whipping, beating, and hosing groups of people with high-volume water cannons (see and ). Anglophone Cameroonians took to Twitter to proclaim ‘the occupier shall have no peace in our territory’, and ‘rise up and resist #France and the colonial army of #Cameroon in our land’ (tweet from 24 August 2018), condemning the synergy between the majority-francophone ruling party and French neo-colonial corporate and state interests.

Figure 5. Social media ecologies of #Anglophone uprising and #Ambazonia conflict, 2016–2018. (Posts on Facebook and Twitter. Collage by author).

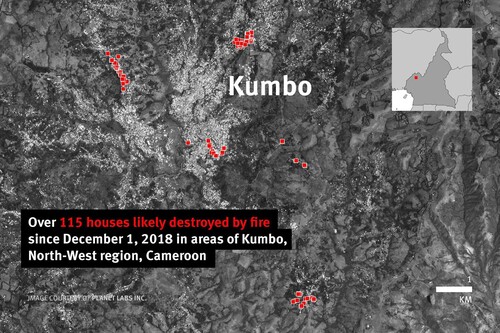

Figure 6. Over 115 houses likely destroyed by security forces since 1 December 2018 in Kumbo, Northwest Region, Cameroon. (Source: Planet Labs Inc. and Human Rights Watch, 2019). https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/03/28/cameroon-new-attacks-civilians-troops-separatists.

In addition to curtailing communications within and between regions of Cameroon, the government’s suspension of the Internet was likely an attempt to block communications between activists and the Cameroonian Diaspora, and to stifle the proliferation of publications critical of President Paul Biya, the RDPC, and Biya’s entourage (interviews with activists, Yaoundé, 2018). Any public gathering that was not orientated toward ‘praising the president [was] suppressed by security forces under the pretext of breach of public order, attempt to break the peace of the land, terrorism, unlawful gathering, or threat to state security’ (italics original, Tapuka, Citation2017, p. 111). The state’s repressive and violent tactics – including pervasive digital infrastructural harm – in response to popular and nonviolent mobilizations in Southwest and Northwest Cameroon, triggered the movement’s violent transformation (Orock, Citation2021). What began in 2016 as a popular, nonviolent movement for expanded judicial and educational rights and federalism, morphed into a splintered and violent separatist insurgency for an independent country of Ambazonia. The resulting Ambazonian conflict has caused the displacement of 768,000 people (Konings & Nyamnjoh, Citation2019; Human Rights Watch, Citation2020) and the killing of an estimated 4000–12,000 people (Annan et al., Citation2021, p. 698).

Digital authoritarianism and infrastructural harm in Cameroon and Ethiopia

The struggles in both countries show significant gradations of twenty-first century infrastructural harm, where infrastructural violence and other forms of state repression, including acute physical violence, intersect. State disruptions of Internet and social media infrastructure have been part of a sweeping set of tactical efforts used more widely to stifle or pre-empt popular struggle in post-colonial societies. They include the monopolization of violent action (including routine but acute moments of street violence, arrests, harassment, and disappearances, and the use of state violence as spectacle to magnify public fear), ideological ploys to depoliticize unpopular policies or divide and ‘manage’ dissenters (again, dating back to the colonial era), as well as the systematic deployment of subversive counterinsurgency protocols on entire sections of society.

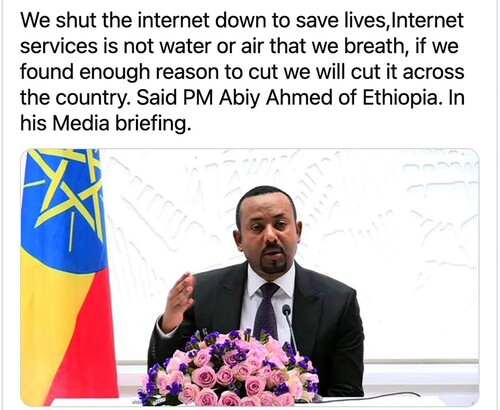

Infrastructures that advance justice and wellbeing take second place (or lower) to corporate infrastructure, in a post-colonial extension of long-standing colonialist patterns. A tweet from one digital activist, @tshilumba_lub (21 August 2018),Footnote10 demanded recognition of the vital role of internet infrastructure within contemporary social and political life, critiquing state restrictions on the Internet as similar to an attack on water or electricity:

Ce qu’ils ne comprennent pas c’est qu’Internet est devenu aussi important que l’eau et l’électricité #KeepItOn #4jeux [What they do not understand is that the Internet has become as important as water and electricity #KeepItOn #4jeux]

Figure 7. Twitter commentary on Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s pronouncement that the Internet is not an essential human need, like air or water.

In the two Anglophone regions of Cameroon, during the height of the nonviolent movement, the internet was either completely shut off or intentionally slowed, ‘with messaging and social media apps blocked for a [combined] total of 214 days’ (Dahir, Citation2018, n.p.). The 93-day shutdown in the Anglophone regions between 17 January and 20 April is estimated to have resulted in the loss of ‘about $38,853,122USD’ (Odunowo, Citation2018, n.p.). The 136-day shutdown from October 2017 to 1 March 2018 was estimated to cost the country $56,817,469USD (Odunowo, Citation2018, n.p.). In Cameroon, CAMTEL has a monopoly on the nation’s fibre optic cable. Although there are a number of private telecommunications companies – MTN, Orange, Nexttel, and various smaller providers – CAMTEL provides connectivity for each, thus controlling connection and speed. During the second shutdown, in a recorded telephone call with a Cameroonian activist, MTN Group Chief Chris Maroleng (Citation2017) confirmed that the government pressured the company to cut the data line:

… we received an instruction from the government, as part of our licence conditions … saying that we must suspend all internet connectivity into the region … This was not a decision of MTN … some have suggested that this was a punishment of MTN … because we have been requested to provide further information to the government [presumably user information for political activists], which we did not because we can only do things that are within, you know, our licence provision. We are suffering as much as other people … .

During the #Qeerroo uprisings of 2014–2018, the Ethiopian government – which owns and controls the country’s only telecommunications internet provider, Ethio TelecomFootnote11 – routinely suspended access to certain websites nation-wide, and all internet in select regions in March–August 2017 and October–December 2017. These internet blackouts were particularly acute during the rolling, government-imposed ‘states of emergency’ (including the one lifted on 2 June 2018), when the use of social media was prohibited, freedom of press seized, internet blocked, and diplomatic travel out of Addis Ababa suspended. The penalty for breaching these rules was three to five years’ imprisonment. The advocacy alliance, Keep It On, decried the Ethiopian state’s regular suspension of the internet. In an open letter to Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in 2018, they estimated that shutdowns in the country ‘cost $32,544USD daily in direct economic costs’ (Odunowo, Citation2018, n.p.). In Ethiopia, one 36-day shutdown in 2016 ‘cost the country about $125,990,676USD’; a seven-day shutdown in 2017 ‘cost the country $6,124,547USD’; and a six-day shutdown in 2018 ‘cost the country a total of $195,000USD in direct economic income’ (Odunowo, Citation2018, n.p.), through the loss of business and disrupted economic and political transactions. The government also engaged in network throttling and blocking of certain websites through Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) technology,Footnote12 then strategically unblocking some websites to demonstrate supposed goodwill and progressive change (author interview with digital activist, Berhan Taye, 12 September 2018; see also Karanja et al., Citation2016). The Ethiopian state has an advanced technical capacity for digital monitoring and filtering. Wilson et al. (Citation2021) explain.

Ethiopia’s government maintains a staggeringly high capacity for monitoring and controlling the internet … [their] capacity for filtering the internet … outperforms nearly every sub-Saharan African country, and ranks high with the rest of the world, having adequate capacity to block access to most specific sites if it wants to. ()

Figure 8. Tweet of Ethiopian digital activists, including Zone9 Bloggers, speaking at the Forum on Internet Freedom, 2018.

Historically embedded practices of state violence have expanded into digital spaces, through Internet blocking; digital population surveillance; infiltrations of collectives; the introduction of new taxes on social media; policies and programmes aimed at censoring social media users, and more (CIPESA, Citation2017; Citizen Lab, Citation2015; Shaheed & Greenacre, Citation2021). These tactics reaffirm long-standing patterns of suppression of political movements critical of the state and elite capture. The Cameroonian political humourist and vlogger, Piment Noir, explained the political atmosphere of dissent in the country this way:

Like [Thomas] SankaraFootnote14 said, when you are on the hilltop during a race, pedalling on your bicycle, you cannot stop. If you go right, you will crash into other cyclists and if you go left you will fall off the cliff … like a cyclist, an activist can only keep going. At a certain point, someone who wants to change direction is a ‘noka’ [i.e. traitor in Cameroonian Pidgin]. Wet is wet. I am already in it … . I can only keep going. Every [television] channel has refused to allow me to speak, they are afraid. I find myself in a situation where I must go on alone. (Conversation, Yaaoundé, December 2019)

manipulated a series of images taken out of Cameroon, which he subsequently mounted in a scenario to overwhelm the defence forces. This activist and others are customary in these orchestrated manipulations for cyber-criminal purposes.

Digital infrastructural harm within the coloniality of infrastructure

The state’s planned stoppages extend beyond the digital realm, as part of a context of intermittent yet semi-permanent infrastructural harm, and more indirect infrastructural violence. During the height of the Qeerroo/Qarree protests, deliberate stoppages occurred alongside electricity and water outages both in and outside of Jimma. Electricity blackouts and brownouts occurred consistently nearly every Friday and lasted through the weekend from approximately December 2015 to May 2016, hence further limiting internet access (author fieldnotes, Jimma, 2015–2016). The anthropologist Daniel Mains (Citation2012, p. 3) explains, ‘These scheduled power outages are especially odd given that the Gibe River, which flows near Jimma, was recently dammed’ (constituting one of Ethiopia’s largest sources of hydropower). People speculated that these power outages also reflected the prioritization of public agribusiness contracts and the exporting of electricity to neighbouring countries for state profit (conversation with activists, Jimma, 2016). While immense infrastructural projects like hydroelectric dams are often touted as progress/modernization in ways used to legitimize and reinforce the power of the state (Mbembe & Roitman, Citation1995; Akhter et al., Citation2022), they frequently produce significant harms (Davies, Citation2021) including through displacement, ecocide, impoverishment, exacerbation of national indebtedness, inflation (Mains, Citation2012), and more. The routine proportion of electrical brown- and blackouts is similarly elevated in Cameroon (Chingwete et al., Citation2019). An analysis of infrastructural harm brings our attention to the compounded-ness of injustices within one community, so that the disruption of the internet occurs alongside disruptions (or absences) other vital infrastructures, including electricity and water.

Internet costs in Cameroon and Ethiopia have historically been some of the highest in the world,Footnote15 a phenomenon that has been characterized as the ‘digital divide’, since information and communication technologies frequently reinforce or exacerbate existing socio-economic inequalities (Mutsvairo & Wright, Citation2019, p. 280).Footnote16 In Ethiopia, internet usage in 2020 was estimated to be around 5.5% of the population (Wilson et al., Citation2021). Internet costs in Cameroon have been among the highest in Africa – a considerable obstacle to access: ‘Prices in 2015 were so high that for unlimited internet access with relatively comfortable speed users had to pay around $55 per month, an exorbitant amount considering that the country’s monthly GDP per capita was only $109.11’ (Steckman & Andrews, Citation2017, pp. 33–34). It is estimated that 80% of Cameroon’s population has been structurally excluded from the internet (Tamokwé & Jazet Citation2016, p. 36), a form of infrastructural harm that overlaps with the infrastructural violence of planned and targeted blackouts, together limiting the ability of Cameroonian political commentators and activists to reach local audiences through digital platforms.

As one Cameroonian digital activist told me, he estimated that 80–90% of his Facebook and YouTube viewers are outside of Cameroon, in places like Paris, Washington DC, and Montreal, even though his target audience is Cameroonians inside the country (interview with political activist, Yaoundé, March 2019). Orange Cameroun rolled out an unlimited data monthly package, which was subsequently cancelled by the state-owned telecommunications company, CAMTEL (interview with Orange technician, Yaoundé, March 2019). Widespread infrastructural harm within Cameroon and Ethiopia means that social media and digital tools are more accessible for activists in the diaspora. Diaspora and transnational activists frequently mobilize and organize on behalf of domestic political issues, protesting at key sites like High Commissions and Embassies abroad.

Activists workaround and evade internet shutdowns

The arbitrary and targeted suspension of functioning infrastructures generates substantial practical and material burdens for people living within these regions to conduct their day-to-day lives and labour. While pervasive, colonial practices are simultaneously disordered and sometimes incoherent, creating fissures and flash points in which activists and people express dissent, struggle for liberation, and eschew the oppressions of the state. People have demonstrated considerable resilience to forms of digital infrastructural harm.

During Cameroon’s 2017 and 2018 internet blackouts, students, movement organizers, and businesspeople were sometimes able to connect to the internet through the use of VPN (Virtual Private Network) software and by setting up ‘internet sanctuaries’ at key border towns. Telecommunications companies in Cameroon only provide VPN software to large business clients, not to private citizens (interview with Marketing and Sales Representative, Orange Cameroon, Yaoundé, March 2019). During a conversation with Renée, an activist who was living in the Anglophone town of Buea during the second shutdown, I was told that university students side-stepped the shutdown by buying VPNs from ‘military personnel’, who had been provided them by the state to bypass the blockage themselves while they occupied the region (interview with activist, Yaoundé, April 2019). The rumour was that some residents and students evaded the internet lockdown by negotiating directly with soldiers; this rumour could only be rendered believable given public suspicion that security forces were enriching themselves during the occupation (see also Lekunze & Page, Citation2022). Digital activists in Cameroon spoke about the importance of downloading free VPN software before any further regional internet shutdown (author fieldnotes, Yaoundé, 2018).

For the activists in Cameroon and Ethiopia who I spoke with and followed online, the intentional use of internet blackouts in attempt to stifle protests was never characterized as ‘successful’. For many of the activists who I spoke with, the Cameroonian government’s sustained internet blackout resulted in heightened international awareness of the conflict and the state’s role in perpetrating violence in the Anglophone region. The blackout triggered a substantial campaign, #BringBackOurInternet, that was picked up by major corporate and state international medias, including Al Jazeera, BBC, Russia Today, CNN, France 24, and more. International attention was counterproductive for Paul Biya’s 38-year autocracy, which has persisted in part by deliberately functioning below the radar. Biya scrupulously avoids media attention (he has never met a political opponent for a public debate in his entire career and does not grant interviews), and his government has a history of ‘discreet and bloody’ crackdowns (National Human Rights Observer of Cameroon, Citation2008).

In Ethiopia, as the blogger and activist Befekadu Hailu disclosed, stories and information shared online are later diffused within communities and activist circles by word of mouth (interview, Yaoundé, September 2018). Meaning that activists and people expanded the reach of internet and social media messages beyond what is visible through social media analysis. In both countries, activists spoke about their adoption of encrypted messaging apps and their strategic use of comic metaphors and memes in online correspondence. Digital activists spoke about the potentials for alternative digital infrastructures in Ethiopia, including the need for ‘community networks … [because] when you decentralize the system enough, then you do not need to worry about one direct-on government shutting down the whole thing’ (interview with Taye, 2018). In Cameroon, one activist told me,

… there was a lot before the internet and revolutions happened before the internet, too … the basic issue is what do people see and what do people want? And, and, if they have something that is urgent and they want to reach their target … they will find a way for it to happen … I do not spend my time thinking about the state’s [objectives because] they are ugly and foolish anyway … [ultimately] the internet block had no effect because we still did what [we] wanted to do. (Interview P. Nganang, New York, September 2018)

Ultimately, political resistance and dissent in Ethiopia and Cameroon continued during and after the internet blackouts. Indeed,

what is even more concerning … is that the government does not notice that shutting down the Internet has not made a difference … the default assumption for a lot of people who have not lived through an internet shutdown is that people sit down, like, you know, just wait[ing] for the internet to come back. That’s not what people are doing … People are organizing in very, very different ways to carry out this work, you know, they’re going back to the basic stuff. (Interview with Taye, 2018)

There are several possible explanations for this confusion between hegemonic interest and digital infrastructural harm. The first is that the blackouts in Cameroon and Ethiopia reveal some of the illogic of authoritarian domination. In the wake of the successful revolutions in North Africa bolstered by social media, an internet blackout may have appeared like a neatly arranged solution to restrict transnational solidary and constrain the real-time sharing of stories of state violence and domination between activists. In this way, they demonstrate the unthinking logic of colonial violence: moments in which government officials make misguided calculations that emphasize the power of the technology and undermine the power of the people. The government in Cameroon enforced corporate-state systems to align – even against the stated wishes of corporate telecommunications firms – through implicit pressure to withdraw contracts (and ultimately threaten their long-term viability in the Cameroonian market). The telecom operated in Ethiopia is state-owned and may have easily capitulated to the caprices of the security state in implementing rolling internet blackouts.

The second explanation for the ambiguities in digital infrastructural harm is that internet blackouts are part of a bigger tool-kit of authoritarian disorderly repression and violence which operates through an extreme capaciousness. To understand the implications of this second interpretation, we need a longer temporal vision and wider scalar analysis. We know, for example, that authoritarian tactics are many and multiple, from persuasion, distraction, discrediting, deception, to policing, militarization, and violence, to covert and overt mechanisms of infrastructural harm (from website throttling, to acute road checkpointing). If the ambition of an authoritarian governance regime is the absolute maintenance of power, domination of the people is the foremost priority. Global/transnational legitimacy may be temporarily sacrificed in the maintenance of national domination. They were a demonstration of the ongoing power of the state to determine the parameters of wellbeing and non-being for everyday people. Infrastructural harm is a menacing reminder of the state’s capacity to effect violence, infrastructural and otherwise. And here the capitalist and colonial logics recombine: it is through pervasive violence that coloniality persists in Cameroon and Ethiopia, and thus paves the way for the continued plunder and extractivism of racial capitalism. We see that those objections from the Orange employee become superficial corporate chatter; suspending the internet connection in the Anglophone regions of Cameroon was a temporary sacrifice made in an authoritarian context to secure continued market share (thus serving long-term corporate extractive interests). Capitalist logics derive from the extractive imperative to cull, create, and steal value (goods, people, earth) everywhere, all the time. While both have frequently operated simultaneously within racial capitalism, colonial and capitalist logics are not mutually exclusive, nor do they continuously work in tandem (just as there are frictions between and amongst capitalist logics).

While infrastructural harm may be detrimental to the immediate interests of private and corporate actors, norms can be suspended and exceptions made within a global racial capitalist system that continues to condone (and strengthen) authoritarian states and governance styles. The continuance of authoritarian configurations of power is essential in the maintenance of global coloniality. Colonial logics are founded on domination, repression, elimination.

Conclusion

The rise of state-initiated internet blackouts in the last half-decade signals a hegemonic apprehension of its potential to facilitate dissent and amplify anti-state critique. This fear has been evident in commentaries on the rising significance of social media in assisting the organization and diffusion of social justice projects (Tufekci, Citation2017; Khondker, Citation2011), particularly following the Arab Spring. These forms of authoritarian tactics of repression have been compounded with other forms of infrastructural harm and state violence.

Colonial logics persist within authoritarian structures of power and extend to digital infrastructures. Birhane (Citation2020, p. 400) writes, ‘Common to both traditional and algorithmic colonialism is the desire to dominate, monitor, and influence social, political, and cultural discourse through the control of core communication and infrastructure mediums’. Digital spaces are disrupted and constrained, sometimes through sustained processes of targeted infrastructural harm which, as I have shown, cannot be separated out from concurrent forms of state violence, including assassinations, disappearances, arrests, harassment, and surveillance of activists and citizens.

The lens of infrastructural harm exposes the simultaneity of targeted infrastructural destruction with other forms of injustice and postcolonial violence, including the lack of political will to invest in infrastructures that support wellbeing/dignity, meaning, and life itself. The creation, safeguarding, and delivery of infrastructures are critical to contemporary socio-political wellbeing. Place-based struggles and popular resistance can fuel demands for justice and infrastructural equality, while contesting the power dynamics of corporate and hegemonic infrastructural technologies. Such resistance personifies critical scholarship on data colonialism (Couldry & Mejias, Citation2019), data and design justice movements, and aspiring decolonial infrastructures.

Decolonial transregional praxis weaves together place-based and digital dissent, and to illuminate the relationship between different communities of struggle. A decolonial perspective helps us to understand how infrastructural harm is being resisted and the emergence of creatives and collectives beyond its scope. Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Citation2012, p. 70) writes, ‘A decolonial turn predicated on making visible the global imperial designs that work to keep Africa in a subordinate position is the beginning of thinking of another world of equality’. It is essential to understand distinct forms of repression if we are to open up conversations around the complex interlinking of shared repressive technologies across fixed borders (often themselves colonial). In the spirit of AbdouMaliq Simone’s (Citation2021) ‘people as infrastructure’, there is a need for further scholarship on the infrastructures of repair, fugitivity, and autonomy (Cowen, Citation2017) – particularly as these infrastructures remain ‘profoundly criminalized’ (Cowen, Citation2017). This article has sought to open (rather than foreclose) a longer deliberation on these topics, and connect with more expansive Pan-African and decolonial conversations on the urgencies of political struggle and the need for emancipatory relations between states, corporations, and people.

Acknowledgements

I thank first and foremost the activists and young people in Cameroon and Ethiopia who spoke, joke, argued, and laughed with me over the last five years. I am grateful to Yannis Kallianos, Dimitris Dalakoglou and especially Alexander Dunlap for putting together this Special Issue and for patiently supporting my work. In the course of writing this article, I benefited from the insights from excellent reviewers, conversations with my students, and many colleagues along the way. All errors remain my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amber Murrey

Amber Murrey is an Associate Professor of Political Geography at the University of Oxford’s School of Geography and the Environment. She is a decolonial political geographer working in the interdisciplinary fields of political ecology, the geopolitics of knowledge in the South, and resistance studies. She has previously held academic appointments at Jimma University in Ethiopia, the American University in Cairo, and Clark University in the US. Amber is the editor of ‘A certain amount of madness’: The life, politics and legacies of Thomas Sankara (Pluto, 2018) and co-author (with Patricia O. Daley) of Decolonizing development studies: Learning disobedience (2023).

Notes

1 Huawei’s expertise in state surveillance is well-known. In addition, the Chinese government regularly hosts knowledge-sharing workshops on censorship and surveillance in African countries (Abdhi Latif Dahir, Citation2018).

2 Elsewhere, policies have been proposed or passed that require the registration and regulation of online social media content. For example in Tanzania and Benin where ‘fees to operate’ risk depressing usage through prohibitive costs. The Egyptian government passed an amendment to the media and press law No. 92 that deems social media users and bloggers with more than 5000 followers to be press outlets and, therefore, subject to the countries’ laws and restrictions on journalists.

3 At the same time, social media has regularly been useful for elite and state actors to circulate hegemonic narratives that would ostracise activists as unpatriotic enemies of the state, terrorists, and/or foreign pawns (author fieldnotes, Yaoundé, 2018, 2019). In both the Oromo and Anglophone uprisings, state representatives regularly diminished the effect of video leaks and visual evidence of state terror by dismissing them outright as fakes, or by appropriating them as an accurate record of the legitimate use of force against protestors deemed dangerous security risks. Both these responses invoked dehumanizing rhetoric against people mobilizing for expanded rights, political change, and social justice.

4 I sought to respond to the need to articulate concrete avenues through which decolonizing praxis might be achieved (Smith, Citation1999; Zaragocin & Caretta, Citation2021; Icaza, Citation2022), and to attend to and respect the labour and time of people in the communities where I worked (Decolonialidad Europa, Citation2013). This meant that I met some activists only once while with others I sustained longer-term collaborations and friendships beyond the remit of this work. Interviews and conversations were conducted in French (often Camfranglais) and English.

5 Ethiopia was never formally colonized by a European power. However, its modern state configurations have been profoundly shaped by the colonial pressures of racial global capitalist accumulation (Kebede Hailu, Citation2021), particularly US-led neo-imperialism (Cochrane & Mandefro, Citation2019).

6 For a comprehensive analysis of the movement, see Forsén & Tronvoll (Citation2021).

7 Following WWI, Kamerun was taken from the Germans and was divided into two territorial units, one by the French and one administered by the British. These colonial linguistic divisions have been strategically exacerbated by Paul Biya’s government for decades (Nyamnjoh).

8 For example, Ndian Division in the Southwest Region does not have a single kilometre of tarred road. For more on the ‘purposeful neglect’ in the region, see Tapuka (Citation2017).

9 In February 2008, state forces killed 139 people during four days of protest (National Human Rights Observer, Citation2008).

10 Quoted with permission of @tshilumba_lub.

11 The Ethiopian government is currently partially privatizing Ethio Telecom and creating a new telecommunications regulator.

12 DPI is a digital technology that facilitates the blocking or throttling of specific websites and applications; this form of internet censorship is quieter (and less likely to be picked up in the media) than internet shutdowns (see Shires, Citation2021).

13 Militarization during the War on Terror reflects colonial continuities throughout the post-colonial era, in particular the militarism of the continent during the Cold War era.

14 Thomas Sankara was the late Pan-African Marxist president of the West African country of Burkina Faso, who is celebrated by activists for his pro-people policies that centred Black lives and Black political will in years of his leadership, from 1983 to 1987 (see Murrey, Citation2017).

15 There is evidence that this may be changing in the last two years. With 100 XAF (approximately $0.19) in 2022, people in Cameroon can purchase phone internet data allowing them to surf on Facebook and message through WhatsApp for an hour or more.

16 The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Digital Economy Report 2021 estimates that 20% of people in what are colonially referred to as ‘least developed countries’ (LDCs) use the Internet, meaning 80% have severely limited access.

References

- Aidi, H. (2021). COVID-19 and digital repression in Africa. Rabat, Maroc: Policy Center for the New South.

- Akhter, M., Akhtar, A. S., & Karrar, H. H. (2022). The spatial politics of infrastructure-led development: Notes from an Asian postcolony. Antipode, 0(0), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12832.

- Al-Bulushi, S. (2021). Race, space, and ‘terror. Notes from East Africa. Security Dialogue, 52(1S), 115–123.

- Amar, P. (2013). The security archipelago: Human-security states, sexuality politics, and the end of neoliberalism. Duke University Press.

- Amin, J. A. (2013). Cameroonian youths and the protest of February 2008. Cahiers d’études Africaines, 3(211), 677–697. https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.17459

- Annan, N., Beseng, M., Crawford, G., & Kewir, J. K. (2021). Civil society, peacebuilding from below and shrinking civic space: The case of Cameroon’s ‘Anglophone’ conflict. Conflict, Security & Development, 21(6), 697–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2021.1997454

- Anyefru, E. (2008). Cyber-nationalism: The imagined Anglophone Cameroon Community in cyberspace. African Identities, 6(3), 253–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725840802223572

- Ayalew, Y. E. (2022). From Digital Authoritarianism to Platforms’ Leviathan Power: Freedom of expression in the digital age under siege in Africa. Mizan Law Review, 15(2), 455–492. http://doi.org/10.4314/mlr.v15i2.5

- Birhane, A. (2020). Algorithmic colonization of Africa. Scripted, 17(2), 389–409. https://doi.org/10.2966/scrip.170220.389

- Biron, C. L. (2012). Death of Ethiopian leader Meles brings ‘opportunity for peace’. Inter Press Service. http://www.ipsnews.net/2012/08/death-of-ethiopian-leader-meles-brings-opportunity-for-peace/

- Bonilla, Y., & Rosa, J. (2015). #Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. American Ethnologist, 42(1), 4–17. http://doi.org/10.1111/amet.2015.42.issue-1

- boyd, D. (2008). None of this is real: Identity and participation in friendster. In J. Karaganis (Ed.), Structures of participation in digital culture. New York: Social Science Research Council.

- Bringel, B., & Dominguez, J. M. (2015). Social theory, extroversion and autonomy: Dilemmas of contemporary (semi)peripheral sociology. Méthod(e)s African Review of Social Sciences Methodology, 2(1-2), 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/23754745.2017.1354546

- Campbell, H. G. (2020). The quagmire of US Militarism in Africa. Africa Development / Afrique et Développement, 45(1), 73–116.

- Chenoweth, E. (2020). The future of nonviolent resistance. Journal of Democracy, 31(3), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2020.0046

- Chingwete, A., Felton, J., & Logan, C. (2019). Prerequisite for progress: Accessible, reliable power still in short supply across Africa. Africa Portal Roundup Newsletter, Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 334. https://www.africaportal.org/publications/prerequisite-progress-accessible-reliable-power-still-short-supply-across-africa/

- CIPESA. (2017). The growing trend of African governments’ requests for user information and content removal from internet and telecom companies. CIPESA Policy Brief, July 2017. https://cipesa.org/?wpfb_dl=248

- Cochrane, L., & Mandefro, H. (2019). Discussing the 2018/19 Changes in Ethiopia: Hone Mandefro. NokokoPod, 2, 1–24.

- Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. A. (2019). Making data colonialism liveable: How might data’s social order be regulated? Internet Policy review: Journal on Internet Regulation, 8(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.2.1411.

- Cowen, D. (2017). Infrastructures of empire and resistance. Verso blog. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3067-infrastructures-of-empire-and-resistance.

- Curley, A. (2021). Infrastructures as colonial beachheads: The Central Arizona Project and the taking of Navajo resources. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 39(3), 387–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775821991537

- Curley, A., Gupta, P., Lookabaugh, L., Neubert, C., & Smith, S. (2022). Decolonisation is a political project: Overcoming impasses between Indigenous sovereignty and abolition. Antipode, 54(4), 1043–1062.

- Dahir, A. L. (2018). Cameroon is being sued for blocking the internet in its Anglophone regions. Quartz Africa Weekly. https://qz.com/africa/1192401/access-now-and-internet-sans-frontieres-sue-cameroon-for-shutting-down-the-internet

- Daley, P. (2018). Toward South-South peace-building. In Fiddian- Qasmiyeh E. & Daley P. (Eds.), Routledge handbook of South-South relations. London: Routledge.

- Daley, P., & Murrey, A. (2022). Defiant scholarship: Dismantling coloniality in contemporary African geographies. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 43, 159–176.

- Datta, A., & Ahmed, N. (2020). Mapping Gendered Infrastructures: Critical Reflections on Violence Against Women in India. Architectural Design, 90(4), 104–111. http://doi.org/10.1002/ad.v90.4

- Davies, A. (2021). The coloniality of infrastructure: Engineering, landscape and modernity in Recife. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 0(0), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/02637758211018706

- Decolonialidad Europa. (2013). Charter of decolonial research ethics. http://decolonialityeurope.wixsite.com/decoloniality/charter-ofdecolonial-research-(Links to an external site)

- Deshayes, C., et al. (2022). Authoritarian adaptation and innovative contestation in Sudan, 2009-2019. In Bach (Ed.), Routledge Handbook of the Horn of Africa. Routledge.

- Docot, D. (2021). Multimodal extractivism. American Anthropologist, 123(3), 689–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13626

- Enns, C., & Bersaglio, B. (2020). On the coloniality of ‘new’ mega-infrastructure projects in East Africa. Antipode, 52(1), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12582

- Esson, J., Noxolo, P., Baxter, R., Daley, P., & Byron, M. (2017). The 2017 RGS-IBG chair's theme: decolonising geographical knowledges, or reproducing coloniality?. Area, 49(3), 384–388.

- Faria, C., & Mollett, S. (2014). Critical feminist reflexivity and the politics of whiteness in the ‘field’. Gender, Place & Culture, 23(1), 79–93. http://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2014.958065

- Forsén, T., & Tronvoll, K. (2021). Protest and political change in Ethiopia: The initial success of the Oromo Youth Movement. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 30(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.53228/njas.v30i4.827

- Freyburg, T., & Garbe, L. (2018). Authoritarian practices in the digital age| Blocking the bottleneck: Internet shutdowns and ownership at election times in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Communication, 12, 3896–3916.

- Galava, D. (2019). From whispers to the assemblage: Surveillance in post-independence East Africa. In M. Dwyer & T. Molony (Eds.), Social media and politics in African democracy, censorship and security (pp. 260–278). London: Zed Books.

- Gohdes, A. (2018). Studying the Internet and Violent conflict. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 35(1), 89–106.

- Gohdes, A. R. (2015). Pulling the plug: Network disruptions and violence in civil conflict. Journal of Peace Research, 52(3), 352–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343314551398

- Hailu, Yerasework Kebede. (2021). Did Ethiopia Survive Coloniality: Eurocentric colonial interpretations of Ethiopian history; Struggle against territorial colonialism; The three unique historical aspects of Ethiopia; Challenges of modernization; Did Ethiopia Avoid Colonialism. Journal of Decolonising Disciplines, 2(2). http://doi.org/10.35293/2664-3405/2019/v1n1

- Human Rights Watch. (2020). Cameroon - Events of 2019. World Report. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/countrychapters/cameroon.

- Icaza, R. (2022). Tanteando en la obscuridad: Decolonial feminist horizons. Inaugural lecture by Professor Rosalba Icaza, 23 June 2022. International Institute of Social Studies.

- Jazeel, T. (2017). Mainstreaming geography's decolonial imperative. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 42(3), 334–337.

- Karanja, M., Xynou, M., & Filastò, A. (2016). How the Ethiopia protests were stifled by a coordinated internet shutdown. Quartz Africa. http://qz.com/757824/how-the-ethiopia-protests-were-stifled-by-a-coordinated-internet-shutdown/

- Khondker, H. H. (2011). Role of the new media in the Arab Spring. Globalizations, 8(5), 675–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2011.621287

- Konings, P., & Nyamnjoh, F. B. (2019). Anglophone secessionist movements in Cameroon. In L. de Vries, P. Englebert, & M. Schomerus (Eds.), Palgrave series in African borderland studies (pp. 59–90). Palgrave MacMillian.

- Kwet, M. (2019). Digital colonialism: US empire and the new imperialism in the Global South. Race and Class, 60(4), 3–26.

- Lab, C. (2015). Hacking team reloaded? US-based Ethiopian journalists again targeted with spyware. https://citizenlab.org/2015/03/hacking-team-reloaded-us-based-ethiopian-journalists-targeted-spyware/.

- Lekunze, M., & Page, B. (2022). Security in Cameroon: a growing risk of persistent insurgency. Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue canadienne des études africaines, 1–18. http://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2022.2120507

- Lesutis, G. (2022). Disquieting ambivalence of mega-infrastructures: Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway as spectacle and ruination. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 40(5), 941–960. http://doi.org/10.1177/02637758221125475

- Mains, D. (2012). BLACKOUTS and PROGRESS: Privatization, infrastructure, and a developmentalist state in Jimma. Ethiopia. Cultural Anthropology, 27(1), 3–27.

- Matute, I. D., & González, R. C. (2021). The machinery of #techno-colonialism crafting ‘democracy’: A glimpse into digital sub-netizenship in Mexico. Democratization. http://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1947248.

- Mbembe, A., & Roitman, J. (1995). Figures of the subject in times of crisis. Public Culture, 7, 323–352.

- Mignolo, W., & Walsh, C. E. (2018). On decoloniality: Concepts, analytics, praxis. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Mohammed, J. (2021). PR-driven journalism model: The case of Ethiopia. African Journalism Studies, 42(1), 108–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2021.1888138

- MTN Group Chief Chris Maroleng. (2017). SoundCloud recording. https://soundcloud.com/ameroon/1248776918531895a

- Murrey, A. (2017). A post/decolonial geography beyond ‘the language of the mouth’. In M. Woons & S. Weier (Eds.), Borders, borderthinking, borderland: Developing a critical epistemology of global politics (pp. 79–99). E-International Relations Publishing.

- Murrey, A., & Jackson, N. (2020). A decolonial critique of the racialized ‘localwashing’ of extraction in Central Africa. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 110(3), 917–940. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2019.1638752

- Murrey, A., & Tesfahun, A. (2019). Conversations from Jimma, Ethiopia on the geographies and politics of knowledge. Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 40(2), 27–45.

- Mutsvairo, B., & Wright, K. (2019). Postscript: Research trajectories in African digital spheres. In M. Dwyer & T. Molony (Eds.), Social media and politics in Africa: Democracy, censorship and security (pp. 279–288). London: Zed Books.

- National Human Rights Observer of Cameroon. (2008). A discreet and bloody crackdown.

- Naylor, L., Daigle, M., Zaragocin, S., Marietta Ramírez, M., & Gilmartin, M. (2018). Interventions: Bringing the decolonial to political geography. Political Geography, 66, 199–209.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. (2012). Coloniality of power in development studies and the impact of global imperial designs on Africa. ARAS, 33(2), 48–73.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2021). Internationalisation of higher education for pluriversity: a decolonial reflection. Journal of the British Academy, 9(s1), 77–98.

- Ndongmo, K. (2021). Cameroon digital rights landscape report. In Digital Rights in Closing Civic Space: Lessons from Ten African Countries (pp. 229–250). Institute of Development Studies.

- Noxolo, P. (2017). Decolonial theory in a time of the re-colonisation of UK research. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 42(4), 342–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12202

- Odunowo, O. (2018). The economic impact of recent internet shutdowns in Africa. TechCabal.