Abstract

The British Council opened its first office in Madrid in 1940. It included an English language institute, a cultural centre and a children’s school. Based on new sources, this research (published as two separate articles in consecutive issues) examines the Council’s three-pronged work in wartime Spain: education, intelligence support activities and cultural diplomacy. It illuminates the crucial contribution made by Walter Starkie, the Hispanist who founded the Council’s Spanish branch. This article discusses the circumstances leading to the Council’s establishment in Madrid, and the opening of the British Institute School, the Council’s only school in the world to date.

The most successful man the British Council has ever had in its

service was Walter Starkie […] in Madrid […] He did a wonderful job.Footnote1

Surprisingly, scholarly research has not yet properly examined the British Council’s foundation in Spain nor the institutional history of the British Council School in Madrid,Footnote3 even eight decades after its foundation. Limited awareness of the institution’s history constitutes a significant knowledge gap not only for the research community, but also in the public sector, where it may have policy implications for the future. Exceptionally well-informed and talented senior British diplomats have served in Spain and even chaired the school board without knowing that Starkie, an Irish Hispanist, musician and travel writer, had founded the British Council in Spain and the school.Footnote4

In order to counter the strongly institutionalized and well-funded Nazi German and Fascist Italian propaganda in Spain, Starkie masterminded an educational and cultural programme for the British Council in Madrid that reflected and profited from his unique range of multidisciplinary academic and research interests and vast personal network and experience in Spain. Starkie exercised a highly successful dual policy of attracting the attention of the Spanish population while curbing German and Italian influence in Spain, thus supporting Britain’s war effort and furthering British foreign policy aims.

This research, published in two parts due to its length, innovatively brings together all three aspects of the British Institute’s activities during the Second World War: education, intelligence and cultural diplomacy.Footnote5 Indeed, while the Institute conducted education through the school and cultural diplomacy via the cultural centre and the language institute, it also supported British secret intelligence operations in furtherance of the war effort. All three dimensions have been addressed separately in the scholarly literature, with varying degrees of academic rigour, but never together.

For instance, Jean-François Berdah’s work, entitled ‘La Propagande culturelle britannique en Espagne pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale: ambition et action du British Council (1939–1946)’, states that the British Council in Madrid was established in November 1940, although Starkie had travelled to Spain in July of that year and the school, which is not mentioned explicitly in Berdah’s paper, had opened in September.Footnote6 The British Institute School’s doctor, Eduardo Martínez Alonso, who was also an agent for the British Intelligence Services, is the subject of a work of historical fiction written by his daughter, Patricia Martínez de Vicente,Footnote7 yet his covert work is not mentioned in Edward Corse’s important book, A Battle for Neutral Europe: British Cultural Propaganda during the Second World War. In fact, Corse’s monograph dedicates only two pages to the British Council School, although this is considerably more than Ali Fisher’s official historical report to mark the British Council’s seventy-fifth anniversary, which does not mention the school at all.Footnote8 Similarly, works by scholars like David Messenger on British intelligence in Spain do not mention cultural diplomacy.Footnote9 Yet the origins of the British Council in Spain are rooted in all three aspects of its wartime operation.

Only a few months after Starkie’s death, scholar J. L. Brooks noted in his obituary of Starkie, published in the Bulletin of Hispanic Studies (on whose editorial committee the latter had sat), that he had found ‘his true métier during the war when he was appointed Director of the British Institute of Madrid’, a ‘delicate semi-diplomatic post’.Footnote10 Yet, literary scholar Jacqueline Hurtley’s amply researched biography of Starkie focuses on the experiences that inspired his literary, artistic and scholarly endeavours, rather than his role as head of the British Council; consequently, it does not question or explore the reasons and aims of the British Council’s establishment in Madrid. Fourteen years of Starkie’s life as the Council’s chief representative in Spain are covered in a single chapter of thirty-five pages, whereas the previous chapter devotes almost one hundred pages to just one decade. The British Council School is accorded only one full sentence: ‘Another early project was the setting up of an infant school, where classes began in the month of September 1940’.Footnote11 Moreover, it is unclear whether other references in the chapter to the number of ‘students’ at the Institute are to children enrolled in the school or learners of English at evening language lessons.

The limited awareness of Starkie’s work in Madrid among the present-day Hispanist community is further demonstrated in Ann Frost’s 2019 report entitled The Emergence and Growth of Hispanic Studies in British and Irish Universities. Written for the Association of Hispanists of Great Britain and Ireland, the report states that ‘Starkie left Dublin for Madrid in 1947’, that is, seven years later than Starkie actually arrived in Madrid to set up the British Council’s branch there.Footnote12

The current study is based on primary sources consulted in British, American and Spanish archives, including the National Archives at Kew (hereafter referred to as TNA), Oxford’s Bodleian Library, the research library of the University of California at Los Angeles, the Duke of Alba’s Liria Palace in Madrid and the Real Academia Española (RAE), as well as on new oral material and testimonials. The first half, covered in the present article, sets out the necessary background to the British Council’s work and Starkie’s profile prior to his arrival in Madrid, and describes the situation he found upon his arrival, especially with regard to Nazi German and Fascist Italian propaganda in Spain. It then turns to examine the British Institute’s work in education and the foundation of the British Council School in Madrid. The second half, which will be published in a consecutive Issue of this journal, will examine the Institute’s participation in intelligence activities and cultural diplomacy in the year when Britain was alone at war (from June 1940, when France was occupied, until June 1941, when Germany launched Operation Barbarossa and the USSR joined the war).

At a time when the sustainability of the British Council’s many activities is at risk, and plans for an expansion of its school network to East Asia, Central Europe and Latin America had, none the less, been discussed prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, it seems all the more relevant to understand the many trials and tribulations Starkie faced in post-Civil War Spain when setting up the Council’s branch and its first school there.Footnote13 The article also gives Starkie the credit he deserves as the mastermind behind the British Council in Spain. Indeed, no other British Hispanist undertook cultural diplomacy in Spain of such great practical significance, yet received so little recognition for it.

Arrivals

Britain was somewhat slow in setting up a government-funded institution to promote the English language and British culture overseas. While the French had already founded the Alliance Française in 1883 and the Italians had launched the Società Dante Alighieri in 1889, it was the threat of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy’s active cultural diplomacy in the Middle East and in South America that brought the British Committee for Relations with Other Countries into existence in November 1934.Footnote14 Two years later, the Committee dropped its long name in favour of ‘British Council’. Lord Tyrrell, who had retired as British ambassador to France in 1934, became the Council’s first chairman.

The British Council opened its first overseas office in Cairo in 1938.Footnote15 Enabled by a budget increase of over 250 percent from 1935 to 1938, new offices in Coimbra, Lisbon, Warsaw and Bucharest soon followed. Within a few months of Nazi Germany’s attack on Poland, and Britain and France’s declaration of war on Germany in September 1939, the British Council was incorporated via a Royal Charter. With the outbreak of war, offices in continental Europe were shut down, with the exception of those in Portugal.

When the new British ambassador to Spain, Samuel Hoare, arrived in Madrid in early June 1940, Spain was still far removed from the war front. A week into Hoare’s term, Fascist Italy joined the war and Paris fell to the Nazis. By the end of the month, units of the German army had reached the Pyrenees. ‘It was now more than ever essential to keep Spain out of the German camp’, Hoare wrote in his memoirs.Footnote16 Portugal, North Africa, Gibraltar and the Mediterranean were at strategic risk, and ‘Spain held the key to all British enterprises in the Mediterranean’, Winston Churchill observed.Footnote17 It was not only military strategy that was at stake, for ‘Spain’s reaction to the war could well determine, too, the ultimate accessibility of the vast economic resources of the Mediterranean and African regions, to which it could open or bar the way’.Footnote18 In Churchill’s own words, ‘Spain had much to give and even more to take away’.Footnote19

In a letter dated 7 June 1940 to Duff Cooper, Minister of Information, Hoare noted how he had ‘never seen so complete a control of the means of communication, press, propaganda, aviation, etc., as the Germans have here’.Footnote20 Scholars have shown that Nazi German and Fascist Italian propaganda was widespread in Spain, including a monthly budget of 200,000 pesetas to pay for advertisements promoting German economic and cultural achievements, pro-Nazi editorials in Spanish newspapers, bribes to Spanish writers and journalists, the publication and distribution of pro-Nazi information bulletins and magazines, news features written by German Embassy staff in Madrid yet published in the Spanish press as independent international reports, and the operations of major Axis news agencies like the Deutsches Nachrichtenbüro, the Transocean News Service and the Agenzia Stefani.Footnote21

In terms of intelligence gathering, Spain was a spy hub, especially Madrid and Tangiers, an international zone annexed to the Spanish Protectorate of Morocco in November 1940. The German diplomatic presence in Spain was the Reich’s largest anywhere, with forty-two consulates in total. The Gestapo and the Spanish political police had entered secret agreements for mutual assistance.Footnote22 Hoare later recalled that he ‘was embarked upon the most difficult task of my whole career’, namely, to keep Spain out of the war—no small feat even for a man who had served as a cabinet minister for fourteen years, including two years as Home Secretary, a brief stint as Foreign Secretary in 1935 and Secretary of State for Air in the 1920s.Footnote23

The British Council’s first representative in Spain arrived soon after Hoare, in July 1940. Negotiations with the Spanish government to open a British Council office in Madrid had begun in October 1939, a month after Britain’s declaration of war on Nazi Germany and six months after the Nationalists’ march on Madrid and the end of the Spanish Civil War. Lord Lloyd, chairman of the British Council since July 1937 and former Governor of Bombay and High Commissioner for Egypt, travelled to Madrid to meet with General Francisco Franco at the Royal Palace on 23 October 1939. Theirs was a ‘friendly’ meeting.Footnote24 According to Lloyd’s Spanish Diary, Franco ‘would unreservedly welcome the establishment of British Council activities in Spain in as full a measure as we cared to develop them’.Footnote25 Lloyd added that ‘it was his [Franco’s] confidence in British educational methods and standards which caused him to welcome the inception of the Council’s work in new Spain’. As Louise Atherton has noted, Lloyd also attempted to induce Franco to sponsor a neutral, Western-aligned Balkan bloc.Footnote26

In a leading article entitled ‘Reconstruction in Spain’ published in early February 1940, The Times observed that there was ‘wide scope for British cultural work there’.Footnote27 Lloyd immediately sent a letter to the editor to inform readers of his October 1939 visit to Spain. The proposal to open a British Institute in Madrid, he wrote, ‘was warmly received by the Caudillo’.Footnote28 At that time, when no major hostilities had taken place between Allied and German troops in the months of the so-called Phoney War, the British Council was in the process of finding suitable premises and a representative who would ‘attend our efforts to renew the fruitful cultural relations which existed between Britain and Spain prior to the outbreak of the civil war’.Footnote29 After all, the British Council’s original aim, set out in this extract from its 1940–1941 Annual Report, was the following:

The Council’s aim is to create in a country overseas a basis of friendly knowledge and understanding of the people of this country, of their philosophy and way of life, which will lead to a sympathetic appreciation of British foreign policy, whatever for the moment that policy may be and from whatever political conviction it may spring. While in times of danger this friendly knowledge and understanding becomes vital to the successful prosecution of war (that is the Council’s place in the war effort), in times of peace it is not less valuable.Footnote30

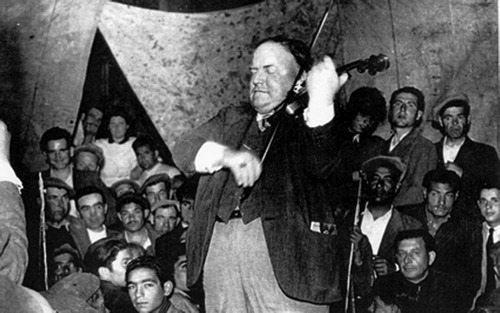

Figure 1 Walter Starkie plays the violin in a Gypsy tent.

Photo reproduced courtesy of Mr John Murray.

Starkie was the first Professor of Spanish at Trinity College Dublin and specialized in contemporary Spanish theatre, particularly the works of Nobel Prize winner Jacinto Benavente.Footnote34 Starkie was born in 1894 in County Dublin to an Irish Catholic family with a long tradition of service to the British Crown. His father was the last Resident Commissioner of Education in Ireland under the Union. Starkie first visited Spain while on honeymoon in 1921; for two months, he and his Italian-Argentinian wife, Italia Augusta, toured the country by third-class train.Footnote35 Starkie returned to Spain often and the Duke of Alba recalled a time when at his wife’s invitation, Starkie ‘presentóse a almorzar un día en casa, con un indumento que, con decir que era gitano, queda descrito’.Footnote36 Indeed, Starkie travelled extensively and was well known back home for his popular travel books, namely, Raggle-Taggle: Adventures with a Fiddle in Hungary and Romania and its sequels, Spanish Raggle-Taggle: Adventures with a Fiddle in North Spain and Don Gypsy: Adventures with a Fiddle in Barbary, Andalusia and La Mancha.Footnote37 He became a director of the Abbey Theatre in 1927 at the invitation of the Irish poet W. B. Yeats.Footnote38

In 1930, Starkie became the first graduate in Spanish from Trinity to be elected to the Royal Irish Academy (followed eight decades later by James Whiston, who wrote Starkie’s biographical entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography).Footnote39 Starkie was a trained violinist, won a gold medal at the Dublin music festival of 1913 and remained a music enthusiast throughout his life.Footnote40 Indeed, in The British Council: The First Fifty Years, the British Council’s official history, Frances Donaldson notes that Starkie ‘had earned fame by wandering through Europe in search of gypsies and their music, earning his bread as he went playing the violin’.Footnote41

Starkie seemed a good fit for the job in Madrid. He was ‘a short, fat man with a strong Irish brogue, but he spoke perfect Spanish and had considerable charm’.Footnote42 Spain’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Colonel Juan Luis Beigbeder, would add yet another reason; in a letter to Lloyd, Starkie recounted what Beigbeder had told him: ‘the Spanish Government particularly welcome my appointment as Director because during Spain’s hour of need I had from the start taken sides with the forces of law and order and had visited the Front to see for myself’.Footnote43 In fact, in the epilogue to his biography of Cardinal Cisneros (dated Christmas 1937, when Starkie was witnessing the siege of Madrid by Franco’s Nationalists), he wrote: ‘To-day in this trench I look back on the troubled years preceding the present civil war. I see a bitter contest between new ideas and catchwords imported from foreign countries in antagonism with eternal Spain […] To-day Spain is fighting the traditional crusade for Latin Christianity against the onslaught of materialism’.Footnote44 Hurtley adds that Starkie’s work with the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and the British War Office in Italy at the end of the First World War contributed to him getting the British Council position in Spain. In Italy—another Southern European and predominantly Catholic country like Spain—Starkie had taught English to foreigners, organized lectures and played his violin for hospital patients, among other wartime educational and cultural activities.Footnote45

References from high places also contributed to Starkie landing the job. To his sister, Enid, who was a lecturer in French at the University of Oxford and Fellow at Somerville College, Starkie quoted his offer letter:

Lord Lloyd […] was fortunate enough to obtain the valuable assistance of the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster in the selection of candidates and it is on the advice of his Eminence that Lord Lloyd makes his approach to you. Cardinal Hinsley considers that you are particularly well qualified for the post and I may say that His Eminence’s views are fully confirmed by information reaching Lord Lloyd from other quarters.Footnote46

One of the ‘other quarters’ Lloyd’s offer letter referred to was probably the Duke of Alba, Spain’s ambassador to Britain, whom Starkie had known since at least 1928.Footnote49 In a collection of essays in honour of Starkie published in 1948, Alba admitted that he was enormously pleased when Lloyd, ‘my excellent friend’, told him he ‘intended to appoint Starkie the British Institute’s first director in Spain’. Alba states he was sure of Starkie’s success because he possessed many qualities that were exceedingly hard to find: ‘Catholic, Irish educated in England, humanist, musician, epicurean, a profound Spain connoisseur, competent Flamenco aficionado, good with people, energetic. My friend has got it all’.Footnote50 In his letter to Enid, Starkie noted that ‘the whole success of the scheme’, would depend ‘on the personality of the first Director’. The British Council, he told her, wanted someone ‘who will need to be both firm and tactful as well as [have] good Spanish and above all he must be able to get on well with all classes of Spaniards’.Footnote51

Prior to his interview with Lloyd, Starkie wrote to Alba to say he had accepted the British Council’s offer ‘on patriotic grounds […] for nothing would give me greater satisfaction than to be able to establish closer relations between Spain and Great Britain’, and to ask for Alba’s advice.Footnote52 In the 1920s, the Duke had founded the Comité Hispano-Inglés, a society committed to improving cultural relations between Britain and Spain and closely linked with the Residencia de Estudiantes, a cultural centre that provided accommodation for students in Madrid.Footnote53 For his efforts he had been awarded an honorary degree by the University of Oxford in 1935, a fact that has not yet garnered any scholarly attention.Footnote54 Alba would later write, ‘I, who have tried hard throughout my entire life to strengthen the ties between England and Spain, think few have contributed to this more than Starkie’.Footnote55

Starkie met with Lloyd on 6 May 1940. By the end of the month (c.25 May), Starkie had accepted the appointment. Confirmation from Spain, however, did not come.Footnote56 In a letter to the Chancellor of the University of Glasgow, Daniel Stevenson, who had inaugurated the Stevenson Chair of Spanish at Glasgow in 1924, Lloyd noted how efforts to set up the British Institute in Madrid were ‘encountering a good many obstacles, generally the result of hostile German propaganda’.Footnote57 In 1940, Nazi propaganda blurred with Nazi cultural diplomacy in Spain, ranging from new or re-founded German-Spanish cultural associations to exhibitions and German book fairs.Footnote58

On 21 May, just ten days after he became prime minister, Churchill received a memorandum from Roger Makins, head of the Western Department at the Foreign Office, which detailed Britain’s goals vis-à-vis Spain: ‘to keep Spain neutral, to support and strengthen the elements in Spain desiring to maintain neutrality, to counter and reduce German and Italian influence and to obtain greater facilities for our own propaganda’.Footnote59 Starkie’s work as founder of the British Council in Spain fell under the rubric of Britain’s war effort and foreign policy aims in Spain as detailed by Makins and as laid out in the British Council’s aims.

In his In Sara’s Tents, a book published in 1953 on the gypsy pilgrimage to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer in southern France, Starkie admitted that he had promised Lloyd in his job interview that he would ‘impose upon myself a self-denying ordinance. I promise I will put the Raggle-Taggle Gypsies to sleep for the duration. Not a line shall I write until the war is over’.Footnote60 It is true that Starkie produced little by way of literary output while on his stint in Madrid, which partly explains why Hurtley, herself a literary scholar, preferred to focus on the life experiences that inspired Starkie’s literary works rather than on his role as British Council representative in Spain. Starkie none the less was responsible for vast amounts of cultural and creative output as founder of the British Council in Spain: he launched a school from scratch and developed a programme at the Institute that contributed to Britain’s war propaganda, countered German and Italian influence and supported and strengthened the elements in Spain who desired to maintain neutrality, as Makins’s memorandum to Churchill had set out.

A British Island in Madrid

On his arrival in Madrid, Starkie began personally to search for an adequate venue for the Council’s new office. This was no easy task as many large houses were in need of repair. Moreover, Madrid’s most important thoroughfare, the Paseo de la Castellana (then Avenida del Generalísimo), was decidedly German turf. The German Embassy was at number 4, about 200 metres north of Plaza de Colón (today, this address is occupied by a concrete office building). The German Evangelical (Lutheran) Church, Deutschsprachige Evangelische Gemeinde Madrid, built at number 6 in 1909 in a neo-Byzantine Romanesque style, still stands and is the only structural remnant of the German neighbourhood.Footnote61 The German conglomerate Sociedad Financiera Industrial (SOFINDUS), which, according to specialist scholar Francisco Javier Juárez Camacho practically monopolized economic relations between Spain and Germany during the Second World War and was also involved in intelligence operations, had its headquarters at number 1—now the headquarters of Crédit Agricole—next to the Palacio de Villamejor, which had served as seat of the presidency of the Council of Ministers until the start of the Civil War. The German consulate was at number 18—now Deutsche Bank’s main office in Madrid—while the Embassy’s press department, led by the Austrian-German Nazi Josef Hans Lazar, was at number 43.

Another German artery in Madrid was the Eduardo Dato/Juan Bravo axis in the Chamberí district. Nazi Party headquarters were housed at number 17 Eduardo Dato, while the German Embassy’s cultural department was at number 8 Juan Bravo. The German School, founded in 1896 and moved to 15 Fortuny in 1911, where it remained until the end of the war, was led by Max Johs, who had earlier worked in the Colegio Oficial Alemán de las Palmas de Gran Canaria. The custom-made palacete was designed by the architect Luis Landecho, co-designer of the Ritz Hotel and the Ateneo in Madrid, and now houses the Spanish headquarters of the Goethe Institut.

Starkie eventually agreed to rent Count San Esteban de Cañongo’s palacete at 17 Méndez Núñez, outbidding the Germans. The small palace was next to the Prado Museum and only three streets down from the Royal Spanish Academy, of which Starkie had been a corresponding member since 1925. Starkie lamented that the neighbourhood was rather residential, but ‘from a cultural point of view’, he wrote, ‘this situation could not be bettered’.Footnote62 Starkie probably had his target audience in mind when he signed the rental contract. Indeed, thanks precisely to its close proximity to the RAE and the Prado, the Institute’s location captured the essence of the ‘eternal Spain’ and facilitated a more fluid relationship with members of the RAE.Footnote63 It also physically distanced the Institute from the German areas in the city and perhaps helped convey an appearance of neutrality. In addition, the palacete was next to the Retiro Park, where students could take their exercise and spend their playtime, thereby supporting a policy of care to the schoolchildren that madrileños could witness themselves. As one student enrolled in 1940 recalled: ‘Los recreos eran casi siempre en el Retiro, en el Paseo de las Estatuas que estaba justo al lado del colegio. Nos llevaban ordenadamente en fila … y allí podíamos salir corriendo a jugar’.Footnote64 This was another reminder of the freedom that a British school offered.

While Starkie was persona gratissima in many circles in Madrid, his first letter to his sister Enid from Madrid reveals just how hard his first few weeks in Spain were, more so than he had expected. ‘For in addition to the extremely difficult political position’, a rumour was spread in Madrid that ‘I was an Irish Mason’.Footnote65 ‘These intrigues’, he found, ‘were started by an Irish priest here’—a reminder that an Irishman working at the British Council could raise suspicion and criticism. Yet, a passage Starkie read in The Times on 19 June, just a day after he had signed his contract with the British Council, struck him as ‘the most precious omen in the world’ and provided him reassurance as an Irishman at work for the British Crown at a time when Ireland remained neutral in the Second World War: ‘In these searching days […] one Irishman wishes to elect himself as an Englishman for the duration; in our vernacular, he wishes to God he could be of some use’.Footnote66

It is no surprise that the Irish priest’s slur would have caused Starkie much unease, for Freemasonry had been officially outlawed in Spain in March of that year.Footnote67 Indeed, Freemasonry had been associated with a significant number of well-known left-wing and republican politicians of the Second Spanish Republic, including by some accounts over one hundred parliamentarians—around one-fifth of the total number—and two prime ministers of the Second Spanish Republic, Manuel Azaña and Alejandro Lerroux.Footnote68 Franco’s blame rhetoric and policy suppression of Freemasonry lasted until his last public speech as Spain’s head of state in September 1975, when he blamed all acts of dissidence on Masonic left-wing plotters, amounting to ‘una conspiración masónica izquierdista’.Footnote69 In other words, the Irish priest’s accusation, if taken seriously, could have caused Starkie a great deal of trouble, and further indicates the difficult relationship at the time between Irish loyalists, like Starkie, and Irish republicans (the Irish priest seemed, to Starkie, to be one of them). Ireland’s past and present tensions were therefore possibly played out in Madrid and could have jeopardized Britain’s cultural and educational war effort in Spain.

In June, Spain’s Interior Ministry published a decree banning propaganda by belligerents. This included ‘premises in which, under name of reading-rooms, libraries and the like, propaganda is done for belligerent countries by oral or written means, by supplying books, notes, pamphlets, broadsheets, documents etc.’Footnote70 Writing to Alba to ask him for the reference letters he had promised, Starkie remarked, ‘I do hope they will send me soon the official confirmation so that I may go out and get to work’.Footnote71 Lloyd contacted Alba for help, which Alba agreed to give privately.Footnote72 In late June, however, official confirmation of Starkie’s appointment was still pending.

Lloyd decided that Franco’s verbal approval, which he had secured in October 1939, was sufficient, and pursued what French historian Berdah has called a policy of fait accompli: ‘this is what the French did’, Lloyd told Ambassador Hoare.Footnote73 ‘I am in favour’, he continued, ‘of beginning activities directly without waiting for any formal permission, or discussing conditions any further’.Footnote74 Christopher Howard and three other teachers (Mr Milburn, Mr Taylor and Miss Jackson) arrived after Starkie.Footnote75 George Reavey, the new institute’s Secretary-Registrar, had moved to Madrid in early 1940 to prepare the ground for the British Council’s first office in Spain. The entire staff of the British Institute was Catholic (at least on paper) as per the Spanish government’s instructions.Footnote76

Education

From the start, Starkie’s mind was set on founding a children’s school in Madrid. There was, however, no precedent for a school operated by the British Council. In fact, the Embassy in Madrid was initially under the impression that the British Council was looking for a house ‘suitable for what might be termed a club’.Footnote77 Admittedly, in 1940, the British Council, itself a relatively new organization, had not fully worked out a comprehensive list of its own activities. Nevertheless, ‘my first intention’, Starkie wrote, ‘was to create an Infant School because, as many Spanish friends informed me, it was one of the best means of attracting the “simpatía” [liking] of Spanish parents’.Footnote78 The British Council agreed to support Starkie’s initiative as long as the school remained ‘entirely under British Council control’.Footnote79

In contrast, the decision to open the Italian School of Madrid (Scuola Italiana di Madrid) in May 1940 as part of Fascist Italy’s ideological propaganda policy, and swiftly recognized by the Spanish government a month later, came from the Italian Ministry for Foreign Relations itself after its decision, a year earlier, to establish the Instituto Italiano de Cultura under Ettore de Zuani, an experienced cultural diplomat who had established the Centro de Estudios Italianos in Argentina in 1937.Footnote80 For its part, the Italian school was headed by Salvatore Battaglia, a professor of Spanish at the University of Naples and specialist on El Cid.Footnote81 As such, Madrid was primed for a war of ideas between Hispanists from both sides of the ideological divide.

‘All the other institutes are housed in splendid palaces which have been bought by their respective Governments’, Starkie remarked somewhat jealously.Footnote82 Indeed, the Italian school and the Italian cultural centre were located, respectively, in the palacete of Santa Coloma, an aristocratic white stucco villa completed in 1914—now the Italian consulate—and acquired by Italy in 1940,Footnote83 and the Palacio de Abrantes, a seventeenth-century building opposite the Council of State on Calle Mayor which had housed the Italian Embassy before it moved to the award-winning Palacio de Amboage on Calle Juan Bravo soon after the end of the Spanish Civil War, where it is still located.Footnote84 Therefore, Starkie’s British Institute had to contend with not one but two Fascist Italian institutions housed in large and iconic residences in Madrid.

Starkie may have taken a leaf out of Italy’s cultural and educational diplomacy book when he decided to open a school and house it in a historic palacete. However, unlike the Italians, Starkie had comparatively few resources at his disposal and limited official assistance in Madrid. He initially operated without a licence, which also meant that there was little administrative security, so advertisements were necessarily kept to a minimum.

The British Institute School opened on 18 September 1940.Footnote85 Starkie had been in Madrid just under three months. The school started off with twenty-five pupils aged four to ten, but numbers had risen to forty by the end of the first term. Five weeks into the first term, ‘the school for children’, Reavey told Carmen Wiggin at the British Council in London, was ‘proving to be a great success […] more are enrolling every day—and this without any advertising. If we did advertise we would be swamped’.Footnote86

For his part, Ambassador Hoare did ‘not want to risk an incident with the German-inspired people and so does not consider it wise to open the Institute officially’.Footnote87 The Embassy, it seems, preferred to keep things low-key. In fact, Lloyd was aware that ‘the Embassy, far from assisting him [Starkie] and the Institute staff in their work, is actually putting obstacles in their way […] Sam Hoare takes no interest at all and gives no support’.Footnote88 On 13 November 1940, Lord Lloyd wrote to Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, asking him for petrol on behalf of the British Council in Madrid. He argued that ‘it is essential to have, for the British Council, 100 litres of petrol per week in order to enable the British Council’s omnibus to take the Institute’s children to school’. He explained that Ambassador Hoare had so far refused to allow Starkie to take petrol from the Embassy’s quota, despite the fact that German propagandists and officials derived their petrol from the German Embassy quota, and that ‘British Secretaries and Attachés use the British Embassy’s quota of petrol freely for their own touring and weekend purposes, whilst our British Institute, engaged on a vital piece of national work, is left without’.Footnote89

Lloyd explained to Halifax that ‘every other Embassy, especially the Germans and Italians, treat their cultural propaganda organisations as the very spear-head of their work, as indeed cultural propaganda can be if properly understood and assisted, but faced with the difficulties inherent to the Spanish situation, no progress can be made without solid and steady support of the Embassy’.Footnote90 Lloyd followed his request with another letter, this time to the Permanent Foreign Secretary Alec Cadogan, in which he further explained that he had ‘written to your Secretary of State begging him to get the Embassy to give the Council greater support than it has done in general’, while he gratefully acknowledged that ‘99% of your Missions give us the most splendid support in all that we try to do’.Footnote91 To Lloyd, Hoare seemed to stand out for the wrong reasons in the otherwise supportive British Diplomatic Service.

Indeed, to confirm that the relationship between Starkie and Hoare was fractious, a year later, in November 1941, Ambassador Hoare wrote a letter to the Foreign Office in which he remarked that ‘[o]rganisation is from all accounts very bad’ and requested a ‘good inspector’ to be sent immediately to report upon the state of affairs at the British Institute.Footnote92 He added that ‘Mrs Starkie seems to make trouble everywhere’. The Council eventually sent Ifor Evans, its Director of Education, to Madrid, but the Starkies continued in their positions thereafter.

John Steegman, an assistant keeper at the National Portrait Gallery in London, who travelled to Madrid in 1942 to lecture on art at the British Council, commented that the relationship between the Embassy and the Council ‘is largely a question of an undoubted personal antipathy between Sir Samuel Hoare and Professor Starkie’.Footnote93 Although there were indeed moments of mutual support and collaboration—after his own lecture at the Institute in March 1941, Starkie reported that ‘the Ambassador has told members of the Embassy how enthusiastic he is about the work done by our Institute’Footnote94—Corse considers that ‘any positive moments were short-lived and differences between Hoare and Starkie kept on cropping up throughout the war’.Footnote95

Aside from the difficulty in obtaining petrol for the school bus, the Institute also experienced other problems, including the procurement of books and other material.Footnote96 Even English teachers engaged by the British Council could not enter the country due to visa and flight delays. Starkie brought up these issues with the British Council chairman when he returned to London in November 1940. As a way around these obstacles, Lloyd nominated Starkie cultural attaché at the British Embassy in Madrid, which eased matters somewhat, although Starkie would continually complain that his position was still unclear: he had diplomatic status in the eyes of the Spanish but not the British.

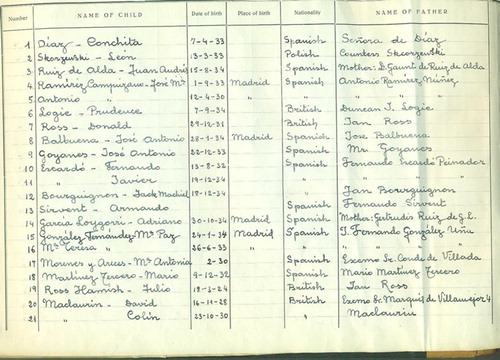

According to Starkie’s first end-of-term report in 1940, at the start of the school year ‘there was an even number of English, American and Spanish [students] but recently Spaniards have become the big majority’ ().Footnote97 Spaniards who sent their children to the school included aristocrats, aspirational parents, liberal intellectuals and professionals, but also workers with links to the British Embassy, such as the ambassador’s driver’s son. There was also a Polish boy, Countess Skorzewski’s son Leon—a reminder that Polish citizens everywhere felt a close connection to Britain because of its intervention in the war in support of Poland.

Figure 2 British Institute School register 1940–1941.

Photo courtesy of the British Council in Spain.

As an example of the type of Spanish aristocrat who attended the British Institute School, Enrique Fernández de Córdoba y Calleja, who had left Madrid during the Spanish Civil War with his mother and siblings as a months-old baby with the help of the British consul in Madrid, was enrolled in the British Institute School on the family’s return to Spain. He remembered that his aunt once removed, Carmen Wiggin, marquesa de Muros, (her maiden name was Fernández-Vallín y Parrella, and her son Charles would serve as British ambassador to Spain between 1974 and 1977), who worked first at the British Council in London and then in Madrid in 1942 as secretary organizer, would sometimes come to his classroom ‘a darme un beso, lo que me hacía sentir importante’.Footnote98 The Count of Villada and the Marquis of Villamejor were among the first to register their children in the school.

Manuel Gutiérrez Cantó, the son of a surgeon and a professor of Medicine at the University of Madrid, and, according to his son, ‘un intelectual relacionado con personas de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza’, was also enrolled in the school in 1940 at the age of five.Footnote99 He remembered another child, Manuel Balsón, the son of a diplomat. Balsón himself recalls that the school was attended by many ‘children from the pro-Anglo aristocracy in Madrid, from well known-established merchants […] also of high middle class [S]panish families, who like my father realized the importance of the English Language despite the war’.Footnote100 They epitomized the Spanish liberal intellectuals and professionals who would send their children to the school in that first year and later continued their association with it. In fact, a 2015 report by the British Council acknowledged that the school was able ‘to target social groups of current and former (and no doubt future) government Ministers and their children, as well as senior leaders and decision-makers across the full spectrum of Spain’s educated and professional elite’.Footnote101 Gutiérrez Cantó’s children and grandchildren also studied at the school.

The school welcomed both girls and boys in a co-educational learning environment (). Testimonies from children enrolled in the school in 1940 confirm that it was a mixed-sex school, a special feature that made it stand out in Madrid.Footnote102 Indeed, on 1 May 1939 the Ministry of National Education had abolished co-education in school groups in Madrid; this ban was later confirmed in the Ley de Educación of 1945 ‘por razones de orden moral y de eficacia pedagógica’.Footnote103 Co-education in Spain was officially banned until the Ley General de Educación of 1970, although a small number of schools, such as the Colegio Estudio, which was founded by women who had previously taught at the Institución Libre de Enseñanza, did not comply with the ban in practice.Footnote104

Figure 3 Female students at the British Institute School.

Photo courtesy of the British Council in Spain.

In England and Wales, only one-third of all grammar schools (state-funded schools with selective intake) and forty percent of all maintained schools (state-funded schools overseen by local authorities) were co-educational in 1947, which suggests that numbers were possibly even lower in 1940. Independent (private) schools in Britain have traditionally been single-sex, and only in the 1990s did their numbers halve, with some of the most well-known schools in the country continuing to offer single-sex education.Footnote105 Judged by both British and Spanish standards of the time, the British Institute School was thus an anomaly due to its co-educational nature. Efforts to limit costs and his own educational philosophy might explain why Starkie decided against single-sex education.

Starkie had the opportunity to launch a new school. As the son of a scholar and educator, he could implement some of the policies his father had wished to introduce in Ireland, such as the amalgamation of girls’ and boys’ education—policies that had been successfully opposed by the Catholic authorities of the time.Footnote106 Starkie’s Italian father-in-law, Alberto Porchietti, had also founded a school in Buenos Aires; some sources say he set up several schools, including the Colegio Internacional Olivos, where a young General Juan Perón studied, so Starkie’s wife, Italia Augusta, may have been particularly sympathetic towards her husband’s educational project.Footnote107

Starkie reported that the school followed the Montessori and Froebel teaching methods. The Froebel method, a learning theory developed by a German educator in the eighteenth century, emphasized play and developed the concept of the Kindergarten that sought to combine work, family and childcare. The child-centred Montessori method promoted activities designed to support the child’s natural development. Starkie may have been acquainted with this method from his stay in Italy in the late 1920s. In 1933, however, the Nazis closed all Montessori schools in Germany and burned her books. A year later, Montessori schools in Italy were closed as well.

Starkie clearly had no reservations about the nationalities of the educational reformers who inspired his school curriculum. Rather, his pedagogical choice reflected the British Institute’s child-centred approach to education and the idea that it should offer the best possible learning environment for Spanish children. Using a method that had been banned in both Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy was also a statement of intent.

Students learnt English, Spanish and French, as well as folk dancing and singing.Footnote108 Schoolchildren enrolled in 1940 vividly remember plays performed in front of parents, including Humpty Dumpty, which set a precedent for later years, when pupils staged Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass.Footnote109 They also recall singing English, Irish and Scottish traditional songs and British Christmas carols with Thomas Slater on the piano, who was also the art teacher and tasked students with copying natural objects, plaster moulds and still lives (he would later teach music and Physical Education).Footnote110 Slater, a trained musical composer, shared Starkie’s love for the violin. The arts played an important role in both the British Institute School and the cultural activities organized for adults at the British Council. Less than a month into the school’s first term, Starkie had succeeded in obtaining coloured prints of several well-known paintings from London, including portraits of the Duke of Wellington by Goya, Admiral Nelson by Lemuel F. Abbot and Walter Raleigh by Federico Zuccaro, and Alfred Munnings’s Gypsies.Footnote111

Drought, Second World War shortages and the impact of the Spanish Civil War caused near-famine conditions in Spain in 1940, so the school provided pupils with a glass of milk and a banana at breaktime each day.Footnote112 ‘I am doing my best to work good relations through the Auxilio Social and other organizations’, wrote Starkie to the British Council Secretary-General before the start of the school year.Footnote113 The British Institute’s commitment to student health and well-being appealed to the social purpose of the Falange’s Auxilio Social, an important welfare organization in the Franco regime.Footnote114 ‘The more we can do to interest ourselves in youth problems, formation of character, child welfare, the better […] for it is imperative to show the Spaniards that England has always been right in the forefront of such work’, Starkie observed.Footnote115 While the school’s nutrition plan may have originated from a duty of care to its children, it also served to convey a positive image of Britain at large: the British Council took care of Spanish schoolchildren. Food aid therefore became a vehicle for cultural diplomacy in Spain.

In late October 1941, Starkie wrote to Wiggin: ‘The School is having a most gratifying success and […] is one of our most effective pieces of propaganda in Spain’.Footnote116 Indeed, in another letter sent a week later, Starkie reported that the extended all-day school timetable had been completely vindicated, ‘for this term we have attracted children from the German school, and in the case of some children who left us to [go] to the German school every one of them has returned to us’.Footnote117 A year later, in December 1942, Starkie observed that the British Council in Madrid continued to draw away many students from the German Institute and children from the German school, and that the British Institute was ‘in continual cut-throat rivalry’ with the Italian and the German institutes.Footnote118

By then, the British Institute School had reached a maximum capacity of 130 children ‘owing to the lack of space’, which had required the Starkies to move out of the Institute’s premises into a nearby flat on Calle del Prado earlier that year and eventually made it necessary to transfer the Institute and the school to Senén House on Calle Almagro 5 in 1944 (now the Escuela de Postgrado Universidad Camilo José Cela).Footnote119 The British Institute School later relocated to premises on Calle Velázquez at the intersection with Diego de León and eventually, in the 1950s, to a palacete at Calle Martínez Campos 31, where the British Council’s Spanish headquarters are now located.

The school was bilingual and bicultural; in other words, it not only taught in both languages but also functioned in both cultures. Starkie purposely celebrated the school’s first Christmas with both a Spanish nativity scene and a British Christmas tree, and school’s houses were founded and named after the patron saints of the different nations of the United Kingdom: St Andrew, St Patrick, St George and, later, St David. At the school Christmas party, the most talented children received book prizes. ‘This party caused a great stir in Madrid’, wrote Starkie in a letter to Lloyd, ‘and the Institute gained in popularity for there is no better way of reaching Spanish men and women than by making much of their children. It is interesting to note that Spanish parents firmly believe that English child education is the best and it is for this reason that our school has a waiting list’.Footnote120 There were, however, no reports about the party in the local press. Although the school only started to advertise itself as an educational institution offering a bicultural education in the mid 2010s, possibly due to the proliferation of state bilingual schools in the Madrid region,Footnote121 its biculturalism unmistakably dates back to Starkie’s efforts in 1940.

The British Institute offered Catholic religion classes as well as lessons in the Anglican faith, and Catholic festivities and sacraments were celebrated. Having been tutored by the school’s chaplain, between ten and twelve children took their first communion on 31 May 1941. ‘The children will all be dressed in white with veils and there will be angels and monaguillos. Afterwards we are giving a little breakfast to the children and their parents and each child will be given a rosary’, reported Starkie.Footnote122 One child who enrolled in 1940 remembers that his first communion ‘fue una ceremonia muy bonita’, even though the sacrament had taken place in the school hall surrounded by moose-head hunting trophies on the walls, which were not quite to his mother’s taste.Footnote123 The school’s offer of Catholic religious education served a double purpose: to ensure that Spaniards could not criticize Protestant Britain’s efforts in Spain, and to suggest that Britain respected Spain’s Catholic traditions and protected Christianity, whereas Nazi Germany did not.Footnote124

Starkie chose to hire British-trained staff with strong links to Spain. He secured the services of Mrs Fernández-Victorio, an Englishwoman and graduate of Leeds University who was married to a Spanish official. Her assistant, Mrs Ruiz de Alda, also an Englishwoman, was the widow of a Spanish air pilot. In addition, the surgeon and physician, Eduardo Martínez Alonso, a Liverpool University graduate, ran check-ups and saw to the children’s health. ‘He keeps a record of each child, weighs them, points out defects in bodily development, and every week gives lessons in hygiene, breathings etc.’, reported Starkie.Footnote125 The staff at the school was made up of British, Irish and Spanish teachers, setting a precedent for a trend that still holds today. In addition, several native English teachers were married to Spaniards, meaning that bicultural family models were present in the school from the very beginning.

To mark the British Council’s 50th anniversary in Spain, the then director of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando and former director of the Prado Museum, Federico Sopeña, wrote in ABC newspaper: ‘Durante estos cincuenta años el Instituto Británico ha cumplido maravillosamente una pluralidad de funciones. Destaca entre ellas el Colegio Inglés’.Footnote126 He praised Starkie as a ‘figura inolvidable’, ‘personaje nobilísimo y pintoresco’ with a ‘personalidad arrolladora’ and a talent for forging ‘amistades entrañables’. His niece, Maisi Sopeña, herself an alumna, current teacher and Head of Spanish in Primary at the British Council School for over a decade, notes of her own student experience in the 1960s: ‘Éramos realmente anglófilos; nos encantaba todo lo británico’.Footnote127 Her uncle ended his piece on the British Council’s 50th anniversary with a flourish: ‘Bajo el patrocinio del nombre de Starkie todos nos regocijamos en estas Bodas de Oro que agrupan nombres dedicados de lleno al diálogo hispano-inglés’. Thus, Starkie’s educational legacy endured well beyond his tenure as director, and it is felt even today, eighty years after the British Institute’s foundation.

Conclusion

While the German Luftwaffe was conducting air raids on London and other sites in Britain, Walter Starkie, the British Council’s first representative in Spain, founded a children’s school in Madrid. To counter widespread Nazi German and Fascist Italian propaganda and attract local goodwill, Starkie decided to start Council operations by opening a school, even though there was no precedent in the British Council’s operations for such an institution, and the Spanish authorities had not yet granted their official permission. The son of an educator and himself a university professor, Starkie considered the opening of a school a most effective piece of British propaganda in Spain.

Starkie created a bilingual, bicultural, co-educational school that followed a child-centred approach, cared for children’s health, promoted the arts, was not religious yet offered a range of Christian religious education to students in Madrid—a rarity at the time. The model attracted Spanish parents from the aristocracy as well as the aspirational and liberal professions. The school started off with just twenty-five pupils, but numbers had risen to forty by the end of the first term. By December 1942, the British Institute School had reached a maximum capacity of 130 children. More than 10,000 students—Spanish as well as from other nationalities—have passed through its classrooms since then. The school, which remains a unique feature of the Council’s branch in Madrid, continues to follow Starkie’s foundational principles three generations on.

Intelligence support activities and cultural diplomacy complemented the educational pillar of the British Council’s work in Madrid and will be examined in the second part of this research forthcoming in the Bulletin of Spanish Studies. Indeed, the identity and cultural contributions of the British Council in Spain are rooted in all three aspects of its wartime activities. An exceptional Hispanist, Starkie played the role of cultural diplomat in Spain with great practical significance.Footnote*

Notes

1 R. A. Phillips (former Controller of Finance at the British Council), quoted in Frances Lonsdale Donaldson, The British Council: The First Fifty Years (London: Jonathan Cape, 1984), 87–88.

2 Walter Starkie, In Sara’s Tents (London: John Murray, 1954), 8.

3 The British Council in Spain began life under the name of the ‘British Institute’. In this article, I use these names interchangeably, including when referring to the British Council School as the British Institute School.

4 Author’s conversations with several former British ambassadors to Spain, including the first (and last) female ambassador to Madrid, Dame Denise Holt.

5 This article is published in two separate parts in consecutive issues of the Bulletin of Spanish Studies. The second part is entitled ‘Education, Intelligence and Cultural Diplomacy at the British Council in Madrid, 1940–1941. Part 2: Shock Troops in the War of Ideas’.

6 Jean-François Berdah, ‘La Propagande culturelle britannique en Espagne pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale: ambition et action du British Council (1939–1946)’, Guerres Mondiales et Conflits Contemporains, 189 (1998), 95–107. Berdah published an earlier version of his paper in Spanish: Jean-François Berdah, ‘La propaganda cultural británica en España durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial a través de la acción del “British Council”: un aspecto de las relaciones hispano-británicas, 1939–1946’, in El régimen de Franco, 1936–1975: política y relaciones exteriores, ed. Javier Tusell Gómez (Madrid: UNED, 1993), 273–86.

7 Patricia Martínez de Vicente, La clave Embassy: la increíble historia de un médico español que salvó a miles de perseguidos por el nazismo (Madrid: La Esfera de los Libros, 2010).

8 Edward Corse, A Battle for Neutral Europe: British Cultural Propaganda during the Second World War (Huntingdon: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012), 93–95; Ali Fisher, A Story of Engagement: The British Council 1934–2009 (London: British Council, 2009). For more on British cultural propaganda in neutral European countries and Spain in particular, see Gloria García González, ‘Pawns in a Chess Game. The BBC Spanish Service during the Second World War’, in Revisiting Transnational Broadcasting: The BBC’s Foreign-language Services during the Second World War, ed. Nelson Ribeiro & Stephanie Seul, Media History, 21:4 (2015), 412–25; Christopher Bannister, ‘Diverging Neutrality in Iberia: The British Ministry of Information in Spain and Portugal during the Second World War’, in Allied Communication to the Public during the Second World War: National and Transnational Networks, ed. Simon Eliot & Marc Wiggam (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020), 167–84; and Robert Cole, Britain and the War of Words in Neutral Europe, 1939–45: The Art of the Possible (London: MacMillan Press, 1990).

9 On British intelligence operations in Spain, see David Messenger, ‘Against the Grain: Special Operations Executive in Spain, 1941–45’, in Special Operations Executive: New Approaches and Perspectives, ed. Neville Wylie, Intelligence and National Security, 20:1 (2005), 173–90; David Messenger, ‘Fighting for Relevance: Economic Intelligence and Special Operations Executive in Spain, 1943–1945’, Intelligence and National Security, 15:3 (2000), 33–54; Denis Smyth, ‘Screening “Torch”: Allied Counter-intelligence and the Spanish Threat to the Secrecy of the Allied Invasion of French North Africa in November, 1942’, Intelligence and National Security, 4:2 (1989), 335–56; Kenneth Benton, ‘The ISOS Years: Madrid 1941–3’, Journal of Contemporary History, 30:3 (1995), 359–410; Javier Rodríguez González, ‘Los servicios secretos en el Norte de España durante la II Guerra Mundial: el Abwehr alemán y el SOE inglés’, in Guerra de silencios: redes de inteligencia en España durante la II Guerra Mundial, ed. Emilio Grandío Seoane, Revista Universitaria de Historia Militar, 4:8 (2015), 75–100; and Michael Alpert, ‘Operaciones secretas inglesas en España durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial’, Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. Serie V, Historia Contemporánea, 15 (2002), 455–72.

10 J. L. Brooks, ‘Walter Fitzwilliam Starkie (1894–1976)’, BHS, LIV:4 (1977), 327–28 (p. 327); Dorothy Sherman Severin & Ann L. Mackenzie, ‘Bulletin of Hispanic Studies’, Romanische Forschungen, 100:1–3 (1988), 31–40 (p. 32).

11 Jacqueline Hurtley, Walter Starkie: An Odyssey (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2013), 259.

12 Ann Frost, The Emergence and Growth of Hispanic Studies in British and Irish Universities (Association of Hispanists of Great Britain and Ireland, 2019), 32; available online at <http://community.dur.ac.uk/hispanists/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/2019-Ann-Frost-report.pdf> (accessed 15 August 2020).

13 ‘Statement on British Council Schools Overseas’ (2012), <https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/british-council-schools-overseas-statement-march2015.pdf> (accessed 5 August 2020).

14 Donaldson, The British Council, 4–5.

15 Arthur J. S. White, The British Council: The First 25 Years, 1934–1959 (London: British Council, 1965), 21.

16 Samuel Hoare, Ambassador on Special Mission (London: Collins, 1946), 28.

17 Winston Churchill, The Second World War, 2 vols (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1948), II, Their Finest Hour, 519.

18 Denis Smyth, Diplomacy and Strategy of Survival: British Policy and Franco’s Spain, 1940–1941 (Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 1986), 10.

19 Churchill, The Second World War, II, 518.

20 Hoare, Ambassador on Special Mission, 32.

21 On Nazi propaganda in Spain, see Ingrid Shulze Schneider, ‘La propaganda alemana en España, 1942–1944’, Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. Serie V, Historia Contemporánea, 7 (1994), 371–86, and her ‘Éxitos y fracasos de la propaganda alemana en España (1939–1944)’, Mélanges de la Casa de Velázquez, 31:3 (1995), 197–217; Mercedes Peñalba-Sotorrío, ‘Beyond the War: Nazi Propaganda Aims in Spain during the Second World War’, Journal of Contemporary History, 54:4 (2019), 902–26 and, by the same author, ‘Tainted Visions of War: Antisemitic German Propaganda in Spain’, in Spain, World War II, and the Holocaust: History and Representation, ed. Sara J. Brenneis & Gina Herrmann (Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press, 2020), 389–402, and her ‘German Propaganda in Francoist Spain: Diplomatic Information Bulletins as a Primary Tool of Nazi Propaganda’, Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies, 37:1 (2012), 47–63. See also Antonio César Moreno Cantano, ‘Los servicios de Prensa extranjera en el primer franquismo’, Doctoral dissertation (Univ. de Alcalá de Henares, 2008); and Antonio César Moreno Cantano & Mercedes Peñalba-Sotorrío, ‘Tinta franquista al servicio de Hitler: la editorial Blass y la propaganda alemana (1939–1945)’, Revista Internacional de Historia de la Comunicación, 12 (2019), 344–69.

22 Andrew Szanajda & David A. Messenger, ‘The German Secret State Police in Spain: Extending the Reach of National Socialism’, The International History Review, 40:2 (2018), 397–415.

23 Hoare, Ambassador on Special Mission, 26. On Spain’s neutrality, see Enrique Moradiellos García, ‘Franco en la Segunda Guerra Mundial: entre la tentación beligerante y el oportunismo pragmático’, Temas para el Debate, 186 (2010), 26–28; see also Enrique Moradiellos García, Franco frente a Churchill: España y Gran Bretaña en la Segunda Guerra Mundial (1939–1945) (Barcelona: Península, 2007); and Miguel Fernández Longoria, ‘La diplomacia británica y el primer franquismo: las relaciones internacionales hispano-británicas durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial’, Doctoral dissertation (UNED, 2007).

24 Lord Lloyd’s reports of visits to Turkey and Spain, with briefing notes from the Foreign Office for a visit to the Balkans, 23 October 1939, TNA, BW 82/13, 11.

25 Lord Lloyd’s report of his visit to Spain, 23 October 1939, TNA, BW 82/13, 7. Lloyd adds, ‘it was [Franco’s] confidence in British educational methods and standards which caused him to welcome the inception of the Council’s work in new Spain’. / ‘He said that he respected and admired the British cultural standards more than those of any other country … ’ / ‘He felt sure that he could implicitly rely upon our careful choice of teachers for Spain’ (11).

26 Louise Atherton, ‘Lord Lloyd at the British Council and the Balkan Front, 1937–1940’, International History Review, 16:1 (1994), 25–48 (p. 26).

27 Anon., ‘Reconstruction in Spain’, The Times, 6 February 1940, p. 9.

28 Lord Lloyd, ‘Relations with Spain’, The Times, 8 February 1940, p. 9.

29 Lord Lloyd, ‘Relations with Spain’, 9.

30 ‘Our history’, British Council, n.p.; available at <https://www.britishcouncil.org/about-us/history> (accessed 3 August 2020).

31 Charles Petrie, The History of Spain (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1934).

32 Hurtley, Walter Starkie, 257. On Hodgson’s appointment, see Lord Lloyd’s letter to the Duke of Alba, 14 February 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.

33 Hurtley, Walter Starkie, 97.

34 Walter Starkie, Jacinto Benavente (London: Humphrey Milford, 1924); Walter Starkie, ‘Benavente: The Winner of the Nobel Prize’, The Contemporary Review, 123 (1923), 93–100.

35 Hurtley, Walter Starkie, 254; Domingo Tomás Navarro, ‘Walter Starkie, director del Instituto Británico, escritor, conferenciante y violinista. Vino por primera vez a España en viaje de boda y la recorrió en vagones de tercera clase’, Biografía Andariegas, 29 (1954), found in Starkie’s file at RAE, Walter Starkie 60:21.

36 Jacobo Fitz-James Stuart, ‘Walter Starkie’, in Ensayos hispano-ingleses: homenaje a Walter Starkie, ed. José Janés (Barcelona: José Janés, 1948), 5–6 (p. 5).

37 Walter Starkie, Raggle-Taggle: Adventures with a Fiddle in Hungary and Romania (London: John Murray, 1933); Walter Starkie, Spanish Raggle-Taggle: Adventures with a Fiddle in North Spain (London: John Murray, 1934); and Walter Starkie, Don Gypsy: Adventures with a Fiddle in Barbary, Andalusia and La Mancha (London: John Murray, 1936).

38 James Whiston, ‘Starkie, Walter Fitzwilliam (1894–1976)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2011), <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/75075> (accessed 5 February 2021); Walter Starkie & A. Norman Jeffries, Homage to Yeats, 1865–1965. Papers Read at a Clark Library Seminar, October 16, 1965 (Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 1966).

39 Ann L. Mackenzie & Ciaran Cosgrove, ‘ “The Lyf so Short, the Craft so Long to Lerne”: James Francis Whiston (1945–2017)’, in ‘The Lyf so Short, the Craft so Long to Lerne’. Studies in Modern Hispanic Literature, History and Culture in Memory of James Whiston, ed. C. Alex Longhurst, Ann L. Mackenzie & Ceri Byrne, BSS, XCV:9–10 (2018), 17–41 (p. 22).

40 Whiston, ‘Starkie, Walter Fitzwilliam (1894–1976)’.

41 Donaldson, The British Council, 87.

42 Donaldson, The British Council, 87.

43 Walter Starkie to Lord Lloyd, 17 September 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.

44 Walter Starkie, Grand Inquisitor: Being an Account of Cardinal Ximenez de Cisneros and His Time (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1940), 451–52. Starkie’s views on the Spanish Civil War were not very different from those held by other Britons of his time. For a revisionist interpretation of British non-intervention in the Spanish Civil War, see Scott Ramsay, ‘Ensuring Benevolent Neutrality: The British Government's Appeasement of General Franco during the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939’, The International History Review, 41:3 (2019), 604–23; and also his ‘Ideological Foundations of British Non-intervention in the Spanish Civil War: Foreign Office Perceptions of Political Polarisation in Spain, 1931–1936’, Diplomacy & Statecraft, 31:1 (2020), 44–64. For the mainstream narrative, see Maria Thomas, ‘The Front Line of Albion’s Perfidy. Inputs into the Making of Policy towards Spain: The Racism and Snobbery of Norman King’, International Journal of Iberian Studies, 20:7 (2007), 105–27; Ángel Viñas, La soledad de la Republica: el abandono de las democracias y el viraje hacia la Unión Soviética (Barcelona: Crítica, 2006); and Enrique Moradiellos, La perfidia de Albión: el gobierno británico y la Guerra Civil española (Madrid: Siglo XXI, 1996).

45 Hurtley, Walter Starkie, 78–79 & 254.

46 Walter Starkie to Enid Starkie, 30 April 1940, Enid Starkie Papers (ESP), Bodleian Library, Box 4, File 2. On Enid, see her autobiography, Enid Starkie, A Lady's Child (London: Faber & Faber, 1941); a biography by Joanna Richardson, Enid Starkie (London: John Murray, 1973); and Peter France, ‘Starkie, Enid Mary (1897–1970)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2004), <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/40857> (accessed 5 February 2021). For her work on Arthur Rimbaud in Abyssinia, Enid Starkie was awarded the first doctorate conferred by the Faculty of Modern Languages at the University of Oxford. In 1946 she became the first holder of the Statutory Readership in French. She was a long-time fellow of Somerville College, Oxford, wrote biographies of Charles Baudelaire, André Gide and Gustave Flaubert, and in 1958 she was made an Officer of the Légion d’honneur.

47 Frederick Hale, ‘Fighting over the Fight in Spain: The Pro-Franco Campaign of Bishop Peter Amigo of Southwark’, The Catholic Historical Review, 91:3 (2005), 462–83 (p. 481).

48 Starkie, In Sara’s Tents, 7.

49 Fitz-James Stuart, ‘Walter Starkie’, 5–6.

50 Fitz-James Stuart, ‘Walter Starkie’, 5–6.

51 Walter Starkie to Enid Starkie, 30 April 1940, ESP, Bodleian Library, Box 4, File 2.

52 Walter Starkie to the Duke of Alba, 2 May 1940, Archivos Fundación Casa de Alba (AFCA), Fondo Don Jacobo.

53 Álvaro Ribagorda, ‘El Comité Hispano-Inglés y la Sociedad de Cursos y Conferencias de la Residencia de Estudiantes (1923–1936)’, Cuadernos de Historia Contemporánea, 30 (2008), 273–91.

54 ‘Encaenia oration for the Duke of Alba’, Oxford University Gazette, LXV:2103 (27 June 1935), 747.

55 Fitz-James Stuart, ‘Walter Starkie’, 6.

56 Hurtley, Walter Starkie, 257–58; Starkie, In Sara’s Tents, 7.

57 Lord Lloyd to Daniel Stevenson, 30 April 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.

58 Isabel Bernal Martínez, ‘Libros, bibliotecas y propaganda nazi en el primer franquismo: las Exposiciones del Libro Alemán’, Hispania Nova. Revista de Historia Contemporánea, 7 (2007); see also her ‘La Buchpropaganda nazi en el primer franquismo a través de la política de donaciones bibliográficas (1938–1939)’, in Género y modernidad en España: de la Ilustración al liberalismo, ed. Mónica Bolufer & Mónica Burguera, Ayer, 78 (2010), 195–232; Marició Janué i Miret, ‘Relaciones culturales en el “Nuevo orden”: la Alemania nazi y la España de Franco’, Hispania (Madrid), 75:251 (2015), 805–32 and, by the same author, ‘La cultura como instrumento de la influencia alemana en España: la Sociedad Germano-Española de Berlín (1930–1945)’, in España y Alemania: historia de las relaciones culturales en el siglo XX, ed. Marició Janué i Miret, Ayer, 69 (2008), 21–45, and ‘A Touch of Nazi Sophistication: The Promotion of Spanish Culture in Wartime Germany’, in Spain, World War II, and the Holocaust, ed. Brenneis & Herrmann, 403–19.

59 Richard Wigg, Churchill and Spain: The Survival of the Franco Regime (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2008), 9.

60 Starkie, In Sara’s Tents, 9.

61 Francisco Javier Juárez Camacho, ‘El espionaje Alemán en España a través del consorcio empresarial SOFINDUS’, in La voce del silencio: intelligence, spionaggio e conflitto nel XX secolo, ed. Alessandro Salvador & Antonio César Moreno Cantano, Diacronie, 28:4 (2016), n.p.; available online at <https://journals.openedition.org/diacronie/4795> (accessed 11 January 2021). For more on the German economic presence in Spain, see Christian Leitz, Economic Relations Between Nazi Germany and Franco’s Spain: 1936–1945 (Oxford/New York: Oxford U. P., 1996); Christian Leitz, ‘Nazi Germany’s Struggle for Spanish Wolfram during the Second World War’, European History Quarterly, 25:1 (1995), 71–92; Carlos Collado Seidel, España, refugio nazi (Madrid: Temas de Hoy, 2005); and Leonard Caruana & Hugh Rockoff, ‘A Wolfram in Sheep’s Clothing: Economic Warfare in Spain, 1940–1944’, The Journal of Economic History, 63:1 (2003), 100–26.

62 Walter Starkie, ‘Minute for Mr Tunnard-Moore’, 3 December 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.

63 Walter Starkie to Arthur White, 18 August 1942, TNA, BW 56/5.

64 Manuel Gutiérrez Cantó, ‘Somos el Británico’, in Yo fui al Británico: 75 años de historias y recuerdos (Madrid: J de J Editores, 2016), 15–18 (p. 16). See also Nicolás Urgoiti Soriano, ‘We Were at School Together’, in Yo fui al Británico, 18–23 (p. 19).

65 Walter Starkie to Enid Starkie, 7 September 1940, ESP, Bodleian Library, Box 4, File 2.

66 Starkie, In Sara’s Tents, 7.

67 See ‘Ley de 1 de marzo de 1940 sobre represión de la masonería y del comunismo’, Boletín Oficial del Estado, 1 March 1940, 62, 1537–39; available online at <https://www.boe.es/datos/pdfs/BOE/1940/062/A01537-01539.pdf> (accessed 3 August 2020).

68 José Ignacio Cruz Orozco, ‘Los diputados masones en las Cortes de la II República (1931–1936)’, in Masonería, política y sociedad. III Symposium Internacional de Historia de la Masonería Española, Córdoba, 15–20 de junio de 1987, ed. José Antonio Ferrer Benimeli, 2 vols (Zaragoza: Centro de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Española, 1989), I, 123–88; Cayetano Núñez Rivero, ‘La masonería y la Segunda República Española (1931–1939)’, Estudios de Deusto, 65:1 (2017), 243–70.

69 ‘Último discurso de Francisco Franco (septiembre de 1975)’, YouTube video, TodoHistoriaContemporanea TodoHistoria Channel, 3 June 2013, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c7EB3-6dYvU> (accessed 3 August 2020).

70 Corse, A Battle for Neutral Europe, 136.

71 Walter Starkie to the Duke of Alba, 6 June 1940, AFCA, Fondo Don Jacobo.

72 Corse, A Battle for Neutral Europe, 136.

73 Berdah, ‘La propagande culturelle britannique’, 99.

74 Lord Lloyd to Ambassador Hoare, 10 June 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.

75 Hurtley, Walter Starkie, 260.

76 Walter Starkie to Arthur White, 2 December 1941, TNA, BW 56/11.

77 The British Council to the British Embassy in Madrid, 20 February 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.

78 Starkie, ‘Report on the British Institute in Madrid’, 3 December 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.

79 Lord Lloyd to Walter Starkie, 31 August 1940, TNA, BW 56/8.

80 Nicola Florio, ‘El Liceo italiano de Madrid’, in Influencias italianas en la educación española e iberoamericana, ed. José María Hernández Díaz (Salamanca: Fahren House, 2014), 67–76; Laura Fotia, ‘Los intercambios culturales y académicos entre Italia y Argentina en el periodo de entreguerras: el rol de universidades e institutos culturales en la Argentina’, Iberoamericana, 19:71 (2019), 197–219, (p. 213).

81 Rubén Domínguez Méndez, ‘Los primeros pasos del Instituto Italiano de Cultura en España (1934–1943)’, Cuadernos de Filología Italiana, 20 (2013), 277–90 (p. 285); Roberta Ascarelli, ‘BATTAGLIA, Salvatore’, Dizionario biografico degli italiani, 110 vols (Roma: Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana, 1960–), XXXIV, Primo supplemento A–C (1988). It is significant that neither Battaglia’s institutional profile nor his biographical entry in the Dizionario biografico degli italiani mentions his time in Madrid, perhaps to conceal a renowned academic’s support of Fascist Italy’s propaganda efforts.

82 Walter Starkie to Martin Blake, 18 November 1943, TNA, BW 56/5.

83 Anón., ‘El Palacio de Santa Coloma’, Cancelleria Consolare Madrid, <https://consmadrid.esteri.it/consolato_madrid/es/il_consolato/la_sede/lasede.html#:~:text=El%20inmueble%20que%20acoge%20la,construy%C3%B3%20entre%201911%20y%201914> (accessed 3 August 2020).

84 Anón., ‘Premios concedidos por el Ayuntamiento de esta Corte a las casas mejor construidas en 1918’, La Construcción Moderna, XVII:24, (1919), 277–79; available online at <http://hemerotecadigital.bne.es/issue.vm?id=0001970674&search=&lang=es> (accessed 11 January 2021).

85 Anon., ‘British Institute in Madrid’, The Times, 3 September 1940, p. 6; Anon., ‘British Institute in Madrid’, The Times, 26 September 1940, p. 3.

86 George Reavey to Carmen Wiggin, 28 October 1940, TNA, BW 56/8.

87 Walter Starkie to Carmen Wiggin, 28 July 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.

88 Lord Lloyd to Lord Halifax, 19 November 1940, TNA, BW 56/11.

89 Lord Lloyd to Lord Halifax, 13 November 1940, TNA, BW 56/11.

90 Lord Lloyd to Lord Halifax, 19 November 1940, TNA, BW 56/11.

91 Lord Lloyd to Alec Cadogan, 21 November 1940, TNA, BW 56/11.

92 Samuel Hoare to the Foreign Office, 12 November 1941, TNA, BW 56/11.

93 John Steegman, ‘Visit to Spain and Portugal: Final Report’, 3 March 1943, TNA, BW 56/10.

94 Walter Starkie to Carmen Wiggin, 25 March 1941, TNA, BW 56/3.

95 Corse, A Battle for Neutral Europe, 83.

96 Lord Lloyd to Lord Halifax, 13 November 1940, TNA, BW 56/11.

97 Starkie, ‘Minute for Mr Tunnard-Moore’, 3 December 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.

98 Enrique Fernández de Córdoba y Calleja, ‘Recuerdos de un antiquísimo alumno del Instituto Británico’, in Yo fui al Británico 13–15 (p. 14).

99 Gutiérrez Cantó, ‘Somos el Británico’, 15.

100 Email from Manuel Balsón to Edward Corse, 27 May 2008, quoted in Corse, A Battle for Neutral Europe, 160.

101 British Council, ‘Statement on British Council Schools Overseas’, March 2015.

102 Fernández de Córdoba y Calleja, ‘Recuerdos de un antiquísimo alumno del Instituto Británico’, 14; Gutiérrez Cantó, ‘Somos el Británico’, 17; Urgoiti Soriano, ‘We Were at School Together’, 21; and Montserrat de la Mata Vila, ‘Recuerdos del British (The Way We Were)’, also in Yo fui al Británico: 75 años de historias y recuerdos, 24–28 (p. 25).

103 ‘Ley de 17 de julio de 1945 sobre Educación Primaria’, Boletín Oficial del Estado, 18 July 1945, 199, 385–416; available online at <https://www.boe.es/datos/pdfs/BOE/1945/199/A00385-00416.pdf> (accessed 11 January 2021).

104 ‘Orden de 1 de mayo de 1939 suprimiendo la coeducación en los grupos escolares de Madrid y creando para los mismos plazas de Directoras y Directores’, Boletín Oficial del Estado, 1 May 1939, 126, 2472; available online at <https://bibliotecavirtual.defensa.gob.es/BVMDefensa/i18n/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.cmd?path=16905> (accessed 5 February 2021).

105 Laura Carter, ‘Counting Co-education’, 28 May 2018, <https://sesc.hist.cam.ac.uk/2018/05/29/counting-co-education/> (accessed 11 January 2021); Graeme Paton, ‘Number of Single-Sex Private Schools “Halved in 20 Years” ’, The Telegraph, 24 April 2014, <https://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/educationnews/10783633/Number-of-single-sex-private-schools-halved-in-20-years.html> (accessed 19 February 2021).

106 Donald H. Akenson, Education and Enmity: The Control of Schooling in Northern Ireland, 1920–1950 (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1973), 13.

107 Dionisio Petriella & Sara Sosa Miatello, ‘Alberto Porchietti’, in Diccionario biográfico italo-argentino (Buenos Aires: Asociación Dante Alighieri, 1976), 1016, <https://web.archive.org/web/20141222102808/http:/dante.edu.ar:80/web/dic/diccionario.pdf> (accessed 24 February 2021); Felipe Pigna, ‘La infancia de Perón’, adapted from Los mitos de la historia argentina 4 (Buenos Aires: Planeta, 2008), 11–16, <https://www.elhistoriador.com.ar/la-infancia-de-peron/> (accessed 15 August 2020).

108 Starkie, ‘Minute for Mr Tunnard-Moore’, 3 December 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.

109 Urgoiti Soriano, ‘We Were at School Together’, 19.

110 Slater joined the British Institute School in October 1941, where he remained until 1988. See Mercedes Puyol, ‘Thomas Slater, músico ferrolano, profesor ilustrísimo y miembro del Imperio Británico’, FerrolAnálisis. Revista de Pensamiento y Cultura, 25 (2010), 31–41 (p. 37).

111 Cable to George Reavey, 15 October 1940, TNA, BW 56/2. Munnings painted several canvasses with gypsy scenes, including Gypsy Life (1913) and (1920), and A Gypsy Encampment (1906). It is unclear which one the cable refers to.

112 Patricia Martínez de Vicente, interview with the author, 13 March 2016.

113 Walter Starkie to Arthur White, 27 August 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.

114 Ángela Cenarro, ‘El Auxilio Social de Falange (1936–1940): entre la guerra total y el “Nuevo Estado” franquista’, in Spain’s ‘Agonía republicana’ and Its Aftermath: Memories and Studies of the History, Culture and Literature of the Spanish Civil War, ed. Susana Bayó Belenguer, BSS, XCI:1–2 (2014), 43–59.

115 Walter Starkie to Arthur White, 27 August 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.

116 Walter Starkie to Carmen Wiggin, 28 October 1941, TNA, BW 56/3.

117 Walter Starkie to Carmen Wiggin, 4 November 1941, TNA, BW 56/3.

118 Walter Starkie to Braden, 18 December 1942, TNA, BW 56/4.

119 Walter Starkie to Braden, 18 December 1942, TNA, BW 56/4; Hurtley, Walter Starkie, 26.

120 Walter Starkie to Lord Lloyd, 15 January 1941, TNA, BW 56/3.