Abstract

In 1940, the British Council founded its first Spanish branch by launching a new school for children as well as a rich cultural programme to counter Nazi and Fascist propaganda in Madrid. Secretly, it also supported the British Intelligence Services’ wartime effort. Based on new sources, the current article (the second in a two-part series) examines these activities in the early 1940s. It also brings to light the crucial contribution of the Council’s first representative in Spain, Walter Starkie. No other British Hispanist has played the role of cultural diplomat in Spain with such great practical significance.

What was needed in Spain was an institution which would create a sound tradition of English teaching and establish cultural relations between scientists, historians and men of letters as well as between students of the two countries, an institution which would be a genuine home of English life and thought, a centre of British Humanism.Footnote1

Supo vencer al principio de su gestión, con gran tacto, las dificultades inherentes a la mayor o menor germanofilia que entonces pudiera haber en España.Footnote2

Based on British, American and Spanish sources, the first half of this study, published in a previous Issue of the Bulletin of Spanish Studies, set out the background to the British Council’s work in Spain and the situation which Professor Walter Starkie, the British Council in Madrid’s first director, found upon his arrival in the Summer of 1940, especially with regard to Nazi German and Fascist Italian propaganda in Spain.Footnote3 That first article then turned to examine the British Institute’s work in education and the foundation of the British Council School, which remains the Council’s only school in the world to date.Footnote4

The second half of my study, which is presented here, examines the British Council’s role in intelligence gathering and cultural diplomacy in Spain during the year when Britain was alone in the war against Nazi Germany (the period from June 1940, when France was occupied, until June 1941, when the Soviet Union joined the war). The Council’s premises and its staff in Madrid played a significant role in wartime humanitarian and intelligence operations. To counter well-funded Nazi German and Fascist Italian propaganda in Spain, Starkie also masterminded a rich educational and cultural programme consisting of English language lessons, academic lectures, musical soirées, tertulias, exhibitions, play-readings, and other social events ranging from flamenco parties to film nights. At the end of his first year in Madrid, Starkie proudly declared that he and his colleagues at the British Council in Spain were ‘shock troops in the war of ideas’.Footnote5

Intelligence

The British Council’s main intelligence-related role in Spain was to support the Special Operations Executive (SOE)—a volunteer organization formed under Prime Minister Winston Churchill and tasked with sabotage and subversion behind enemy lines—in its escape operation to guide Jews, Allied soldiers and other war refugees through Spain and to safety. The SOE personnel file in the British National Archives at Kew reveals that, between 1940 and 1941, Eduardo Martínez Alonso, the British Institute doctor in Madrid, was ‘the principal agent in assisting SOE bodies out of Spain’.Footnote6

In 1984, the specialist scholar M. R. D. Foot wrote in a seminal book that ‘the story of what SOE attempted in Spain, and secured in Italy, is waiting to be written—or at any rate to be published—in English’.Footnote7 Today, monographs on the SOE in Spain comparable to those on the SOE’s secret operations in France, Norway, Greece, Italy, Slovenia and Albania, have yet to be written.Footnote8 Whereas David Messenger’s important articles on the SOE in Spain concentrate almost entirely on its role in Iberian economic warfare,Footnote9 recently, Marta García Cabrera’s research has shown that there is more to say about the SOE’s activities in Spain.Footnote10 Because the escape route established by Martínez Alonso through Spain into Portugal has not received any academic attention, the current study helps to insert both him and the British Council into the historiography of escape from war-torn Western Europe and furthers research on the SOE in Spain.

In fact, an SOE file report by Martínez Alonso explains that the passage through Spain and into Portugal of individuals coming from France had to be staged in three phases: 1) across the Pyrenees into Spain, whilst arrangements were made for them to be picked up by a diplomatic car and taken to Madrid; 2) rest in Madrid; and 3) the last phase from Madrid to the Portuguese border.Footnote11 It is in the second phase that Starkie would have participated and provided a safe house to escapees, meaning that British Council premises and staff played their part in wartime humanitarian and intelligence operations.

The existing literature has focused primarily on the first phase of the route. The flight of Jewish refugees over the Pyrenees has been studied from a French perspective predominantly by Émilienne Eychenne in the 1980s, who estimated that between 15,000 and 50,000 Jews, evaders of the French Service du Travail Obligatoire and Allied servicemen crossed the Pyrenees during the war.Footnote12 Almost three decades later, Josep Calvet grappled with the subject from a Spanish perspective in his unprecedented work on the escape route through the Pyrenees of Lérida. His research has since been turned into a broader travelling exhibition titled Perseguidos y salvados. No querían que existiéramos on the approximately 15,000 Jews who crossed the Pyrenees into Spain, which was presented at the Centro Sefarad-Israel in Madrid and the Cervantes Institutes in Warsaw, Krakow and New York in 2019.Footnote13 The Pyrenean route has also been the subject of an episode of the documentary series WWII’s Great Escapes: The Freedom Trails. Yet, the literature is comparatively scant on what happened once refugees were inside Spain.Footnote14

There has been much heated debate about whether or not, to what extent, and who within the Franco regime supported the rescue and safe passage of Jewish refugees in Spain. While the former Prime Minister of Israel, Golda Meir, and the former Secretary-General of the World Jewish Congress, Israel Singer, acknowledged the important role Franco’s Spain played in aiding Jews during the Holocaust, researchers such as Bernd Rother argue that such a claim has been wildly exaggerated by postwar Francoist propaganda.Footnote15 Rother contends that Franco did not do enough to protect Jews from death and persecution.

For his part, José Antonio Lisbona, a Spanish journalist and researcher, has identified a number of diplomats and Spanish Foreign Office officials deployed in several European cities, including Paris, Bordeaux, Nice, Milan, Berlin, Budapest, Athens, Sofia and Bucharest, who were able to save around 8,000 Jews from deportation and likely extermination. Lisbona maintains that these Spanish diplomats adopted a proactive stance on a personal level, but their actions were not the result of a policy by the Franco regime to protect Jewish refugees, despite what the regime ‘so much liked to claim after the war’.Footnote16

In her ground-breaking work Whitehall and the Jews, Louise London contends that British policy towards European Jews between 1933 and 1948 was motivated primarily by national self-interest rather than humanitarian concern. London maintains that ‘the only major response to the plight of Jews in this period resulted in the admission of (limited numbers) of women, and (unrelated) children’ (the Kindertransports), and that, as one book reviewer noted, ‘it is the illusions of these apparently humanitarian actions that feed the myths that inform present day political arguments’.Footnote17 More recently, Diana Packer has explored the British government’s fears that admitting too many Jews to Britain would result in increased anti-Semitism among its own population.Footnote18 Britain’s immigration policies did not allow for special treatment of entire ethnic or national groups based on refugee status, but rather continued to consider potential immigrants on an individual basis as laid down in the Aliens Registration Act 1914, the Aliens Restriction Act 1919 and the Aliens Order 1920.

Regardless of whether the individuals involved acted out of personal conviction, government policy or a mixture of the two, the actions of people linked to the British Council in Madrid reveal that British resources were mobilized to alleviate the plight of the Jews during the Holocaust. In a statement made in January 1943 in the House of Commons, the Deputy Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, said that

[ … ] we are at present giving our urgent consideration to the whole vast problem of rescue and relief for both Jews and non-Jews under the enemy yoke [ … ] The lines of escape pass almost entirely through war areas where our requirements are predominantly military, and which must therefore in the interests of our final victory receive precedence [ … ] but we shall do what we can.Footnote19

Several personal accounts of the Comet Line, the resistance network that helped Allied servicemen in Belgium return to Britain, mention the assistance of Michael Creswell, a British diplomat attached to the Embassy in Madrid and the department at the War Office tasked to help prisoners of war escape (MI9) to Andrée de Jongh (Dédée), the first leader of the Comet Line.Footnote20 Martínez Alonso also mentioned Creswell in his memoirs and wrote that together they

[ … ] toured the most convenient passes in the Pyrenees and arranged with divers [sic] innkeepers and even monks to hide these boys and warn us of their presence and we would arrange to have them picked up. We left money and clothes to be supplied to these escapees and waited for results. These were excellent and the scheme was one that functioned very well right through the war.Footnote21

In addition, staff members of the British Council in Madrid were directly involved with the second and third phases of the escape operation. It was vital for Britain’s continued war effort that SOE agents, wounded soldiers and Allied airmen who had been shot down over occupied Europe return to Britain. In addition, for most of the war, foreign nationals who wished to volunteer in the British Armed Forces were only allowed to do so if they resided in or had previously made their way to Britain, which meant that the escape route network through Spain proved significant for new recruits to join the war effort.Footnote22

As a participant in the second stage of the escape route, Martínez Alonso comments in his memoirs that he concerned himself with the health and fate of British subjects and other Allied officers and soldiers who ended up in the Miranda de Ebro concentration camp near Burgos, a facility originally created to hold ‘Spanish soldiers and civilians who had fled into France at the end of the Spanish Civil War’Footnote23 or ‘los prisioneros republicanos españoles’, to use the term employed by the scholar Matilde Eiroa San Francisco.Footnote24 Allied soldiers trapped in occupied France fled across the Pyrenees hoping to reach Portugal or Gibraltar and then return to their own countries, but if they were caught by Spanish police they were interned at Miranda until their identity, provenance and ultimate fate could be determined.Footnote25

Eiroa San Francisco’s calculations indicate that just two weeks after the fall of France in June 1940, there were 187 French, Belgian and Polish internees at Miranda. Numbers peaked in early 1943, when 3,770 French, Canadian, Polish and British internees were held there, despite the fact that the camp had been ‘originally planned to hold around 500 men’.Footnote26 Martínez Alonso worried that overcrowding might lead to a typhus epidemic.Footnote27 As Miranda filled up with British and other Allied soldiers, Martínez Alonso and the British Embassy’s assistant military attaché travelled there every weekend to take ‘provisions, cigarettes, and money, and also to check up on their identity’.Footnote28 Once the soldiers had been cleared, they were taken to the Embassy in Madrid, washed and de-loused, then escorted to the border and thence home. An SOE report stated that ‘there is no doubt that he [Martínez Alonso] had been genuinely involved in the arranging of the escape of British prisoners from Miranda’.Footnote29

In addition, Martínez Alonso assisted SOE agent (French section) Marcel Leccia, codenamed ‘Baudoin’, known also as Georges Labourer, across and out of Spain, although Leccia was captured when he returned to occupied territory, and was tortured and killed at Buchenwald concentration camp in 1944.Footnote30 An October 1941 report states that Leccia/Labourer was a prisoner at Miranda in barrack No. 20, which means Martínez Alonso would have assisted his escape from the camp and into Portugal.Footnote31 It seems that several French prisoners at Miranda were passed off as French Canadians by British authorities in Spain.Footnote32 In August 1941, for example, twenty-five prisoners of war of different nationalities were evacuated from Miranda under the pretence that they were Canadian (and therefore subjects of the British Empire): one man whose real surname was Aymard became known as Brown; Van de Heyden became Richardson; and Danze became Cooper.Footnote33

According to his memoirs, Martínez Alonso proposed to the ‘appropriate members of the Embassy’—he did not detail whom—‘that many of these boys need not have to go through the discomfort and dangers of the Miranda camp’. Instead, he recommended that the British ‘set up a series of stations along the main passes in the [Pyrenees] and have them picked up there. Once in our possession we would take them directly to the Embassy or across the border into Portugal or Gibraltar’.Footnote34 Therefore, although he was mostly involved in the second and third phases of the passage, Martínez Alonso also participated in the first phase of the escape plan, for he explained in an SOE report that Creswell and he had found ‘Sabas’, a Spanish collaborator, in the spring of 1941: Sabas picked up the men, fed them at his inn in the Pyrenees, and then took them down to his farm in Pamplona where they would wait for a diplomatic car from Madrid to take them on to a safe house in the Spanish capital.Footnote35

Although in his memoirs Martínez Alonso may have exaggerated his role in the plan to prevent escapees from being detained at the Miranda camp, his SOE file confirms that he set up an escape route, ‘by means of which persons who had escaped enemy-occupied Europe were passed through on their way to Allied territory’.Footnote36 ‘He has helped in many different negotiations such as frontier crossings and never let us down’, read another report.Footnote37 Martínez Alonso also recounts how he helped a young English girl who had been living in a quiet French village with a German-Jewish surrealist painter.Footnote38

Starkie and his wife hid escapees in their Madrid lodgings, as did Martínez Alonso.Footnote39 Starkie’s daughter, Alma, a teenager at the time, remembered one particularly handsome British pilot who was unwell and stayed at their flat, although ‘quite a lot [stayed] over time’, she recalled.Footnote40 Embassy, a sophisticated English-style tea room near the British and German embassies on the Paseo de la Castellana (owned by Margarita Kearney Taylor, who, like Starkie, was Irish Catholic), also provided a safe haven for Jews and Allied soldiers before they were smuggled out of Spain ().

Figure 1 Dr Martínez Alonso (far left), Walter Starkie (second left) and Ramona de Vicente, Dr Martínez Alonso’s wife (far right), at a party in Madrid (1949). Photo courtesy of Patricia Martínez de Vicente.

Starkie, Taylor and Martínez Alonso collaborated with Alan Hillgarth, an intelligence officer and the British naval attaché to Spain whom Churchill ‘had real affection for’.Footnote41 As stated in Duff Hart-Davis’ biography of Hillgarth, Martínez Alonso and Hillgarth ‘became the closest of friends, trusting each other absolutely, each seeing in the other a man prepared to take risks for a humanitarian cause’.Footnote42 In turn, Hillgarth and Hoare won London’s approval for a large-scale effort to persuade Spanish generals, through bribery, to maintain Spain’s neutrality, through the good offices of the Majorcan financier Juan March, whom Hillgarth probably had met while he was the British Consul in Majorca.Footnote43

In December 1941, Captain Hillgarth warned the British Institute School’s doctor to leave Madrid immediately because the Gestapo was determined ‘to stop your activities in the escape line’.Footnote44 Martínez Alonso and his new bride, Ramona de Vicente, asked for passports in order to spend their honeymoon in Portugal, but they did not return to Spain until after the war. Instead, they travelled to England via Lisbon. Upon their arrival in Bristol on 15 February 1942, Martínez Alonso was detained and escorted to the Royal Victoria Patriotic School (RVPS) on Wandsworth Road in London, an internment camp for aliens and an interrogation centre for refugees from continental Europe.Footnote45 A major from the War Office who was meant to pick them up had failed to receive the notification from Lisbon in time.

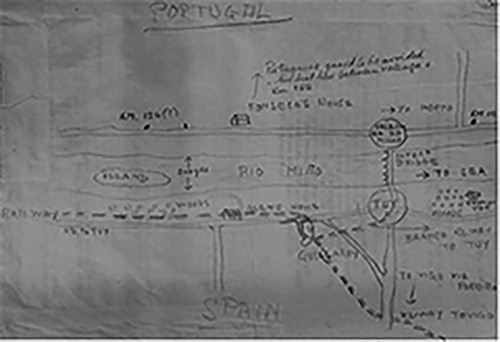

As part of his interrogation, Martínez Alonso drew a sketch of the escape route into Portugal he had established from Galicia, his native region (). He identified two safe houses near Tuy (Spain) and Valença do Minho (Portugal) as well as two secret crossings over the river Minho labelled ‘A’ and ‘T’. He pointed out that telegrams from Madrid to Ríos, a taxi driver and their agent in Vigo, to inform of the planned route would be signed ‘with any name beginning with A (e.g. Álvarez) when the Allen route or T (e.g. Talavera) when the Trimotor route is to be used’.Footnote46

Figure 2 Dr Martínez Alonso’s sketch of the escape route into Portugal from Galicia (1943). The National Archives, HS9/26/5.

Once the muddle had been cleared up, Martínez Alonso wrote from London to Pío Baroja, perhaps the foremost Spanish novelist of his generation. He explained that the last time they had seen each other had been at a concert at the British Council in Madrid, and on that occasion Baroja had asked him whether he planned to travel to America. Martínez Alonso apologized in his letter for not having been able to share with him that he had made arrangements that very day to escape to Britain.Footnote47 He then proceeded to share some details of his experience at the RVPS, where he had been in custody for three days; he had been kept separate from his wife, and both had been interrogated at length.Footnote48 He described the wartime blackouts in London, which sought to prevent crews of enemy aircraft from being able to identify their targets, and observed that ‘you see lots of women in trousers, women of all ages and in trousers of all colours’.Footnote49 Martínez Alonso’s writings also provide informative insights on a pro-British Spaniard’s experience in wartime London.

Martínez Alonso applied to work at the British Council in Britain and put down Dr Sir James Purves Stewart, whom he had probably met in Madrid when Stewart delivered the British Council’s inaugural lecture, as one of his referees.Footnote50 Instead, Martínez Alonso received and completed training as an SOE agent in Scotland. By then the Germans had mustered thirty divisions on the French side of the Pyrenees, ready to march into Spain, capture Gibraltar and cross the Strait to invade North Africa. ‘My knowledge of Spain and the Spanish people placed me in a privileged position to be dropped behind the advancing Germans and my help was needed to cut their lines’, he recalled in his memoirs.Footnote51 ‘Am very interested in Anglo-Hispano relations and a Spanish Restoration on democratic lines’, Martínez Alonso wrote in his application form to join the SOE.Footnote52

Although he did not enter into any details in his memoirs—he signed the Officials Secrets Act immediately before he travelled to Scotland for SOE training—his report card conveys an insightful picture. The instructor’s remarks in the final report mentioned that Martínez Alonso had taken a keen interest in the training and that he had gained good theoretical knowledge. However, ‘his practical work suffered due to his tendency to avoid anything strenuous’. In addition, the Commandant’s reports stated that he was ‘a rather cunning type but pleasant and quite popular. Very talkative and has a keen sense of humour. Definitely a lone worker who will probably prove an extremely useful operative’.Footnote53

Not long after, however, the Afrika Korps commanded by Erwin Rommel—nicknamed the ‘Desert Fox’—was beaten back, and the thirty divisions waiting at the Pyrenees had to be deployed to North Africa via a quicker, easier route, thus averting a Nazi invasion of Spain, which meant Martínez Alonso did not participate in an SOE operation after all. However, at Creswell’s recommendation, soon after the war Martínez Alonso was awarded the King’s Medal for Courage in the Cause of Freedom, a British award for foreign nationals who aided the Allied effort during the Second World War.Footnote54 Efforts by his daughter to have a street named after him in Madrid, however, have not yet proved successful.Footnote55

In addition to supporting the safe passage of Allied personnel through Spain, Starkie collaborated with the British Embassy’s press attaché, Thomas Burns, an acclaimed Catholic publisher in London and editor of a number of Graham Greene’s novels, in a covert propaganda role.Footnote56 Jimmy Burns’ wartime biography of his father, Papa Spy, notes that ‘in his official and covert activities, Starkie found a friend and trusted colleague in Burns. Both men mixed in similar social circles of bullfighters and artists, and looked to each other’s foreignness to rescue them on occasions from the stuffy insularity of some of their diplomatic colleagues’.Footnote57 This, it seems, included Ambassador Hoare, who did not mention Starkie once in his memoirs.

A 1946 review of Hoare’s book, Ambassador on Special Mission, chastized Hoare—by then Lord Templeton—for this omission:

Throughout the war, the underlying sympathies between Spaniards and Englishmen of all degrees were kept alive not by the British Embassy but in the genial atmosphere of the British Institute. If ever anyone had a ‘special mission’ to Spain it was that scholar Gypsy Professor Walter Starkie, the British Council representative, who forged a thousand permanent Anglo-Spanish links even in the darkest days of the war. It is perhaps typical of Sir Samuel that the vital work of the British Institute in Madrid is not once referred to in his book’.Footnote58

In his book, Jimmy Burns calls Starkie ‘a British agent’, his ‘eccentric public persona belying a background of discreet service to His Majesty’s Government as an Anglo-Irishman who strongly identified with the Allied cause’.Footnote60 But there is no available archival evidence to demonstrate that Starkie was indeed an agent in the strict sense of the word. In fact, Alma Starkie wrote a letter to the editor of El País in 1986 in which she strongly objected to an earlier article on the Anglo-American Hospital in Madrid that had called Starkie a ‘miembro del servicio de espionaje de su país’.Footnote61 Incidentally, the article also misspelt his name as ‘Starquie’.Footnote62 Although Starkie may not have been a British officer or an employee of a British intelligence agency, he certainly collaborated with Britain’s secret war effort in Spain, employed Martínez Alonso—‘the principal agent in assisting SOE bodies out of Spain’—as the British Institute School’s doctor, co-operated in the escape route network, and served as a major agent of influence in Spain.

Furthermore, there are indications that staff at the British Council in Madrid, in their effort to support British intelligence operations, explored strategic partnerships with their American allies. For instance, Theodore Pahle, a New York-born cinematographer who was transferred by Paramount Pictures from Paris to Barcelona to help rebuild the Spanish film industry after the Civil War, was appointed press attaché at the US Embassy in Madrid in early 1944.Footnote63 Starkie and Pahle had first met at the Ritz Hotel in Barcelona in 1940.Footnote64 Pahle and his family moved into a flat on the seventh floor at Monte Esquinza 30, where the Starkies also lived at the time. Pahle’s son, Theodore, now a retired US Defence Intelligence Agency career officer, writes that ‘there are plenty of indications this was a British and American intentional residential match for espionage or influence operations’.Footnote65 When Martínez Alonso returned to Spain after the war, he moved in next door at Monte Esquinza 28. Both Martínez Alonso and Pahle enrolled their children at the British Council School, which at the time was still on Calle Velázquez at the intersection with Diego de León, and Pahle notes that Martínez Alonso’s daughter Patricia ‘remains my closest and almost-family friend in my life’.Footnote66 Pahle moved back to the United States with his family in 1958. On his retirement from the British Council, Starkie also moved to the United States, where he took up several academic posts, ending with a professorship at the University of California in Los Angeles, although he eventually returned to Spain, where he died in 1976. He and his wife are buried at the British Cemetery in Madrid.

Cultural Diplomacy

Cultural diplomacy at the British Council in Madrid was enacted through its language centre and cultural programme. Although the children’s school had opened in September 1940, adult classes began only in December of that year. English language lessons took place at the British Institute in the evenings, from 17:30 to 21:00. Most students were Spanish government office workers and shop employees, for as Spanish Foreign Minister Beigbeder had put it a few months earlier, ‘in the mind of every ambitious young Spaniard was the firm intention of learning English’.Footnote67 The target audience, therefore, was Madrid’s aspirational youth.

Beigbeder was right when he said students would ‘flock’ to the British Institute:Footnote68 after just two months of teaching English, the Institute had over one hundred students. Lessons in Madrid were in such high demand that Starkie, in a January 1941 letter to Carmen Wiggin, the liaison for Spain at the British Council’s headquarters, wrote: ‘I have been having a most strenuous time here, in fact it is true to say that we are run off our feet. Our student roll is mounting by leaps and bounds’.Footnote69 English lessons were 100 pesetas per year for three lessons a week and 150 pesetas a year for six lessons a week. There were sixteen classes in the evenings and over 150 students on the waiting list by February 1941.Footnote70

Writing to Wiggin in early May 1941, Starkie was sorry to report ‘that some of the students have dropped off from the Institute. This, I am told, is mainly due to the political situation and the unrelenting German propaganda, which has been more virulent than ever since the Serbian and Greek defeat. I have even been told by some of our diplomatic students that they have been black-listed by the Germans, hence their absence from our courses this term’.Footnote71 To Starkie’s dismay, the Deutsches Wissenschaftliches Institut Madrid (German Cultural Institute in Madrid) opened on 27 May 1941.Footnote72 Nevertheless, the British Institute’s student numbers had reached 500 by the end of 1941, and Starkie compared the centre to ‘a London railway station in rush hour’.Footnote73 The Nazi counter-attack had been repelled, although Starkie recognized that he held ‘a tough fighting job’ and that Madrid was ‘no place for drones’, parasites or indolent individuals.Footnote74

Several letters from Starkie to various British Council officials followed the German Cultural Institute’s formal inauguration. Starkie addressed his first letter directly to the British Council’s Secretary-General, Arthur White. In a second letter to White, Starkie noted that the new German Cultural Institute was ‘opened with great éclat in imitation of our own’ and asked, perhaps rhetorically, why the Germans had decided to open a cultural institute ‘at such an unpropitious academic moment as the end of May, when most Institutes are beginning to close for the summer vacation? Do the Germans intend to keep their Institute open all the summer? If so what are we to do?’Footnote75 Affluent Spaniards usually went away in summer, mainly to San Sebastian in northern Spain, a spa town only forty kilometres away from Nazi German troops stationed across the French border. ‘But surely’, Starkie continued, ‘we are not merely an Institute, we are part of the united British war effort and we cannot afford to slumber for three months and allow the Germans to forge ahead’.Footnote76

To Wiggin, Starkie wrote that the German Cultural Institute’s ‘foundation the other day was the best compliment we have yet received, for I was told privately by Spaniards that it was founded in opposition to ours as well as in imitation’.Footnote77 It was clear that the British Institute’s increasing appeal to Spaniards had not gone unnoticed by Nazi Germany. A few days later, Starkie addressed a letter to Martin Blake, also at the British Council, where he again brought up the idea that the new German Institute of Culture, ‘which Spaniards consider a direct move against us’, was in fact also ‘a tribute to our success among Spaniards of all classes’.Footnote78 But ‘we can only beat German propaganda if we play a very efficient and a very active part’, he added.Footnote79 After all, the Germans had spent at least four times as much to furnish their new Institute.Footnote80 Starkie resolved to advertise widely. To his surprise, nearly all the Spanish papers offered generous space to place his advertisements.Footnote81

The head of the German Cultural Institute was also a Hispanist. Professor Theodor Heinermann, a specialist in Spanish medieval literature, particularly on Inés de Castro and Bernardo del Carpio, and editor of Calderón’s Alcalde de Zalamea and Don Quixote in German, was based at Münster University, where he had taken over the Chair in Romance Philology in 1937 from Eugene Lerch, who had been suspended by the Nazis due to his pacifism.Footnote82 Karl Vossler, a prominent Romanist and emeritus professor at the University of Munich, author of Lope de Vega und sein Zeitalter (1932) and Einführung in die spanische Dichtung des Goldenen Zeitalters (1939), was the first option for the post in Madrid, but his appointment seems to have been vetoed by the Nazi Party’s Office of Foreign Affairs due to his opposition to anti-Semitism.Footnote83 Indeed, in an obituary of Vossler published in 1946, Oxford’s King Alfonso XIII Professor of Spanish William Entwistle wrote that ‘the last years of his life can hardly have been happy. The Hitlerian régime must have been deeply distasteful to [him]’.Footnote84 For his part, Heinermann became a member of the Nazi Party and must have been thankful for his own promotion. He held the post at the German Cultural Institute in Madrid until 1944, which meant that Starkie had to battle against not one but two recognized Hispanists—Heinermann and Salvatore Battaglia, a professor of Spanish at the University of Naples and the director of the Italian Cultural Centre—in the ‘war of ideas’ in Madrid.

The Institute and the school both used the crest of the British Council, which was officially granted in July 1941. ‘Truth will triumph’ read the strapline written on a flowing ribbon held by two rampant lions positioned on either side of the shield. Appropriately for an institution that promoted the English language, the Council’s motto was in English rather than the usual Latin. The shield depicted an open book, a symbol of knowledge, alongside the English lions, one of which held a flaming torch, surely indicating that the Council’s goal was to shed the light of knowledge on the world. The crest was stamped on teaching material, report cards and books up until a point in the 1980s, which means that the Institute’s motto continued to be used throughout the war and the Cold War period.

In addition to the British Institute’s language instruction, the Council also served as a cultural centre. Membership of the Institute’s British-Spanish club was open to Spanish and British nationals, while citizens from the US and South American republics were eligible for associate membership. For 50 pesetas per annum or £1/5s, individual members gained library rights and were invited to events at the Institute. Associate members paid 100 pesetas or £2/10s. All prospective members had to be recommended by someone already known to the British Institute.Footnote85 By mid March 1941, the Institute had 120 members, including four lifetime members, and a donation of 5,000 pesetas.Footnote86 It is unclear who donated the money, but the donation was equivalent to one hundred membership fees—a significant sum indeed. In September 1940, a friend of Starkie’s, the Marquesa de Frechilla, ‘very kindly presented the Institute with about a hundred English books’.Footnote87 Thus, Starkie managed to mobilize his personal network in Madrid to support the Institute’s first steps.

The British Institute’s cultural programme reflected and channelled Starkie’s personal multidisciplinary interests in academia, research, literature, theatre and music. Starkie exercised a dual policy of attraction and criticism in the cultural diplomacy of the Institute: the programme aimed to attract Spaniards to the British Council, while the selection of activities also served to criticize the Axis powers, especially Germany.

A flamenco party held at the Institute at the end of the first academic year, complete with canaries and geraniums, top male and female singers, a guitarist and two dancers, served to convey Britain’s appreciation of traditional Spanish culture and a veiled criticism of Nazi German attitudes towards other European cultures, as evidenced by the persecution of the Roma (). ‘It was certainly one of the best flamenco parties they have had recently in Madrid’, Starkie reported to London.Footnote88 The party brought together people from a wide variety of backgrounds, including aristocrats, Carlists, former Republicans, artists and diplomats—‘a cross section of Spanish society’.Footnote89 Thanks to Starkie’s contacts, the British Institute became a hub for Spaniards to meet in.

Figure 3 Flamenco party at the British Institute in Madrid (1941 or 1943). Walter Starkie and his wife, stand at the foot of the staircase. A poster of Winston Churchill hangs on the right, next to the library signpost. Photograph reproduced courtesy of Mr John Murray.

Like the Council’s language centre, the Institute’s cultural programme started after the British Institute School’s launch in September 1940. Starkie decided it was best to wait ‘until I was quite certain we could make a good show’, for ‘the first British Institute in Spain must be a worthy symbol of British culture’.Footnote90 However, Starkie hastily organized an inaugural recital in October 1940 to take advantage of a unique opportunity: the Czech pianist Rudolf Firkušný, who had fled the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia, was passing through Madrid on his way to the United States. Starkie reported that ‘the whole musical public turned up, including the principal composers, conductors, pianists, string instrumentalists, and the musical critics of all the papers’.Footnote91 The British Council provided influential Spaniards with a once-in-a-lifetime experience to hear an eminent pianist, while at the same time calling attention to the fact that a brilliant musician had been forced to flee Europe because of Nazi persecution (Germany had annexed the Sudetenland in October 1938 and invaded the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939). Firkušný accompanied Starkie in playing Hungarian, Romanian and Greek gypsy music, which also reminded the public of the Nazi persecution of the Roma. In addition, Starkie turned the recital into a tribute to the recently deceased Spanish violinist and composer Enrique Fernández Arbós, former director of the Orquesta Sinfónica de Madrid and professor at the Royal College of Music in London.Footnote92 The soirée was conceived to attract Spaniards, praise Spain’s talent, showcase links between Britain and Spain, and offer veiled criticism of German policies and propaganda.

Following this impromptu and well-attended inauguration on 13 October 1940, the Institute hosted its first official lectures in January 1941.Footnote93 Two lectures by an acclaimed British neurologist, Sir James Purves-Stewart, whose book The Diagnosis of Nervous Diseases had broken new ground, brought in the scientific community, including the ‘principal Madrid doctors and surgeons’, the Spanish Minister of Education and several members of the nobility. ‘Ever since, I have been inundated with demands for the revised Spanish text of his lectures and I am hoping soon to have them printed’, Starkie told Wiggin. He must have felt that it was safer to launch the British Institute’s lectures with a politically neutral topic in the field of medicine. He wrote, ‘the lecturers we need from England in Spain are those who will talk as masters of their subject; in this way there is no fear of political propaganda creeping in’.Footnote94 The lectures served to attract ‘all the principal men of science and doctors in Madrid’, and Starkie made a point of personally introducing several of them to Purves-Stewart, possibly including the school’s doctor, Martínez Alonso. By featuring lecturers of a high calibre, the British Council showed respect towards its Spanish audience and promoted Britain as a scientific spearhead to counter German scientific propaganda. The Council also presented itself as the facilitator of personal contacts between top Spanish and British researchers.

Later that month, Starkie organized a musical soirée with works by British composers. The membership of the string quartet carried great symbolism, for it was made up of the British Vice-Consul, John H. Milanés, who had helped British deserters from the International Brigades (a largely Communist organization supported by the Communist International) to abandon the fighting,Footnote95 and the Spanish musicians Conrado del Campo, then director of the Orquesta Sinfónica de Madrid,Footnote96 Juan Ruiz Casaux, a renowned cellist and senior professor at the Madrid Conservatory, and Pedro Meroño, later Chair of viola at the Madrid Conservatory.Footnote97 ‘All the prominent Spanish musicians came to this concert’, reported Starkie.Footnote98 The newspaper El Alcázar commented on the ‘interesante’ soirée and labelled Starkie the ‘director inteligente’ of the British Institute.Footnote99 Again, the soirée served to attract influential Spaniards to the British Institute, to showcase Spanish talent, to display Britain’s musical tradition, to highlight cultural links between Britain and Spain and to counter German and Italian cultural promotion.Footnote100

Professor Julio Casares, Secretary of the Real Academia Española (RAE) and Starkie’s neighbour—Casares lived in a flat three streets down from the British Institute—told Starkie at the concert ‘that he personally would welcome a small festival of the works of [Henry] Purcell whom he regards as one of the greatest musicians that ever lived and the embodiment of England’.Footnote101 On passing Starkie’s report on to the British Ministry of Information, Wiggin received word back from the Ministry that ‘if a festival of British music could be arranged in Madrid, it would be of the utmost importance to our propaganda in Spain’.Footnote102 After all, Nazi propaganda often repeated an old German taunt that portrayed Britain as ‘das Land ohne Musik’ (‘the land without music’).

Starkie mentioned in a report that the RAE had invited him to present his latest book on Cardinal Cisneros and some of his other works. ‘This’, he said, ‘is very important because the Germans and Italians have tried to monopolise the attention of the academies in Spain and now is our chance to gain recognition and I shall stress the ideals of the British Council in my short speech’.Footnote103 Starkie’s speech at the RAE plenary session was introduced by Casares, who said the British Council could not have found a más simpático or more efficient person than Starkie to set up the British Institute in Madrid. ‘Starkie, who has so many old friends in Spain, can trust that each and every one of us at the RAE will be his friend and shall see to it that his mission in Spain [ … ] finds all the ease and reciprocity it deserves’.Footnote104

Starkie took the opportunity to explain his role as British Council representative in Spain. The British Council, he said, was committed to strengthening friendly ties between Spain and Britain, showcasing Britain and the Commonwealth’s contributions to the arts and sciences, and to raising a sense of unity in culture, which, of course, ‘you, as academics, always keep in mind’. Starkie also invited the audience to visit the British Institute: ‘You will feel at home’, he assured them.Footnote105 In a follow-up letter, Starkie reminded Casares that ‘it is my fondest wish that you, Sr. Asin, Eugenio d’Ors and other Academicians will visit me at the Institute’.Footnote106 Academic fellows of the RAE took up Starkie’s invitation to visit the British Institute. In fact, Starkie’s correspondence with Wiggin suggests the extent of the Institute’s appeal to many important intellectuals in Spain at the expense of German and Italian propaganda:

I was told by many of the Spanish intellectuals that they consider the British Institute the one centre in Madrid where there is ‘ambiente’ and a sense of freedom. Pío Baroja and other writers would not go to the German or Italian Embassies or Institutes. We are thus playing a very important part here in bringing various irreconcilable sections of the Spanish peoples together in harmony. Who would imagine such people as Baroja, Zuloaga, Sebastian de Miranda and Machado would meet in the same room with Pilar Primo de Rivera and other members of the Falange.Footnote107

The novelist Pío Baroja, the poet and playwright Manuel Machado, and the painter Ignacio Zuloaga proposed to ‘have a kind of weekly tertulia here in the Institute where we would be able to discuss literary and artistic matters’. Starkie thought it a very good idea, ‘for the tradition of the tertulia’, he reported, ‘has nearly died out in Spain and it would be interesting if we could restart it under our own auspices’.Footnote108 Starkie’s aim to draw RAE fellows to the British Institute worked: tertulianos came together at the British Institute in Madrid. Thus, the British Institute played host to a Spanish intellectual tradition and helped revive it. Indeed, after only two years, in 1943, Starkie reported that: ‘the Institute Tertulia is now one of the best known gatherings in Madrid. The informal parties are held every second Sunday afternoon and include the best-known writers etc. in Madrid. Often the number of persons present reaches seventy or eighty. Presiding genius is the famous Spanish novelist, Pío Baroja, who has attended ever since they started three years ago’.Footnote109 As Tom Burns would later put it, the Institute ‘was itself an embassy to the survivors of Spain’s intellectual eclipse’.Footnote110

That same year, the Spanish poet, literary critic and scholar Dámaso Alonso and Leopoldo Panero, a poet and close friend of Alonso’s, approached Starkie to interest him in the publication of an anthology of Spanish-British poetry by Ortega y Gasset’s Revista de Occidente (Alonso and Panero had been associated with the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, respectively, in the early 1930s). Starkie immediately wrote to London ‘to make a proposal to the British Council which in my opinion would be a really excellent piece of cultural propaganda’.Footnote111 Although the literary project did not come to fruition in the end due to limited funds, Alonso published six poems by Gerard Manley Hopkins in the edited volume Ensayos hispano-ingleses (1948) in honour of Walter Starkie and again in Antología de poetas ingleses modernos (1963).

Starkie also enacted his dual tactic of attraction and criticism through other scholarly lectures he organized at the British Institute. On 3 March 1941, the Institute hosted Father Henry Heras, who spoke on ‘India as Source of Inspiration and Study’, with Ambassador Hoare, former Secretary for India, acting as chair. Born in Barcelona in 1888, Heras was a Spanish Jesuit, a professor of ancient Indian history at St Xavier’s University in Bombay, and founder of both the Indian Historical Research Institute and Museum and the Bombay Historical Society. ‘Nadie más calificado que el sabio jesuita español para revelar al selecto auditorio las fuentes educativas de aquella tierra de intrigante misterio’, noted an article in the newspaper Pueblo.Footnote112 Indeed, the British Institute provided a platform for a Spanish Catholic priest to lecture, which again conveyed Britain’s tolerance for Spain’s main faith and an appreciation for the work Spanish Catholics had undertaken in the British Empire. Furthermore, a lecture by a prestigious member of the Order founded by St Ignatius of Loyola would have been of interest to Spanish attendees, while also reminding them that Nazism persecuted the Jesuits. Jesuit historian Vincent Lampomarda notes that ‘just as it is not wrong to say that there was a Nazi war against the Jews, one can also speak of a Nazi war against the Jesuits’.Footnote113 Furthermore, Mercedes Peñalba-Sotorrío has suggested that ‘through 1940 and 1941, following orders from Paul Karl Schmidt, chief of the Foreign Affairs Ministry Press Office, the [German] embassy focused on spreading the image of the greedy British Empire’.Footnote114 A Spanish Jesuit in Bombay would certainly present a different account.

Ten days later, on 13 March 1941, Starkie gave an exceptionally well-attended lecture entitled ‘Music, Magic, and Minstrelsy—Some Experiences of a Folk-Lorist’, in which he played violin melodies he had collected from his travels in Spain, Hungary, Romania and Greece. ‘We had the biggest number of people we have ever had. I was glad that many of the artists, musicians and scholars came to it’, reported Starkie.Footnote115 In an academic article published in 1935, Starkie had written that ‘in Spain the old wizened guitar players of Jerez de la Frontera and Cadiz wield the same magic powers as the fiddlers of Transylvania. In all those countries the gipsy has played for centuries the part of national minstrel, keeping alive among the people the old songs and dances’.Footnote116 Here again, Starkie showcased his appreciation of important elements of Spanish culture while at the same time pointing to a trait shared with other European peoples and to the persecution of the Roma. The lecture took place a week after the Italian attack on Greece, which was followed by the German invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece just months later. Meanwhile, Operation Lustre, the movement of British and other Allied troops (Australian, New Zealander and Polish) from Egypt to Greece started in March 1941, in response to the failed Italian invasion and the looming threat of German intervention. Starkie’s lectures on music in the British Institute’s first year were followed later in the war by similar lectures, such as ‘The English Scholar in Gipsy Literature’ and a series of six lectures on ‘England in Song and Symphony’.Footnote117

In late January 1941, soon after the British Institute’s official inauguration in Madrid, Starkie reported that the Institute had ‘been termed variously “Instituto Botanico” and “British Museum”!’ by the press in Spain.Footnote118 By 25 March 1941, however, just two months later, Starkie reported to Wiggin that ‘we are gradually winning over even the irreconcilable elements in the German-controlled press … in my opinion, we have adopted a wise and far-seeing policy in not seeking publicity but letting it come to us gradually. Once the tide turns, we stand to achieve great results’.Footnote119 Ambassador Samuel Hoare’s lecture at the Institute that month, titled ‘Between Two Wars: Some Changes in English Life’, was, in Starkie’s words, ‘our grand finale to our first term’, and with all the government departments and foreign diplomats, the entire press, and all the professions in attendance, ‘such a lecture is indeed excellent propaganda’.Footnote120 In addition, Starkie admitted to Wiggin that he had arranged it especially ‘because, in my opinion, it was absolutely necessary to make a big splash before the Ambassador’, probably also to get on Hoare’s good side.Footnote121

As soon as he got word that a new British Council chairman had been appointed in 1941 to replace Lord Lloyd, who had obtained General Franco’s informal go-ahead in 1939 to start British Council activities in Spain, Starkie wrote a letter to Sir Malcolm Robertson to describe the British Institute’s work in detail. Over the previous year, Starkie reported, the Institute had put on literary, musical, artistic and scientific events.Footnote122 Importantly, the Institute ‘gathered together a big nucleus of Spanish cultural life round us. In building up our membership I worked hard through my personal connections’ with the Spanish Academy, the Church, the Government and official groups, and the ex-Republicans. In Starkie’s opinion, ‘this all-inclusive policy has succeeded’. He made sure to stress that the British Institute had worked hard to counter Nazi German and Fascist Italian propaganda, for the Germans had twelve cultural institutions in Spain, while the Italians had seventeen. Nearly all of these cultural centres had been set up since the Spanish Civil War. But this did not deter Starkie. After all, ‘we are shock-troops in the war of ideas and any policy of vacillation or timidity would spell ruin’, he declared boldly.Footnote123

Starkie also pursued the war of ideas through visual material. In July 1941 a ‘film apparatus’ arrived; it was used to screen documentaries and as a projector during scientific lectures by renowned British scientists, including the noted London Hospital brain specialist H. W. B. Cairns, who had conducted Lawrence of Arabia’s post-mortem a few years prior.Footnote124 Evening cinema screenings were also arranged at the Institute.Footnote125 In this vein, the British Council secured a lecture tour to Madrid by Hollywood film star Leslie Howard, famous for portraying Ashley Wilkes in Gone with the Wind (1939), which received ten Oscar nominations at the 12th Academy Awards, and for Pygmalion (1938), in which he starred as Professor Higgins.

An English Jew, Howard was prized by the British government on account of his anti-Nazi propaganda and his films in support of the war effort, such as Pimpernel Smith (1941) and The First of the Few (1942), both of which Howard directed and produced himself. In Pimpernel Smith, he played the role of a Cambridge archaeology professor who successfully fools the Nazis with a fake excavation (ostensibly in search of evidence of the Aryan origins of German civilization) in order to free inmates of concentration camps and other persecuted intellectuals—a modern update of his leading role in the popular film The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934). The film plot shared some similarities with the British Council’s own intelligence support activities in Spain.

Howard lost his life while travelling back to England after his tour when his plane was shot down by the German Luftwaffe off the coast of Galicia.Footnote126 ‘In Spain there has been quite an extraordinary grief at his passing’, wrote Starkie in a letter, ‘I wish I could convey to you the deep impression he made by his extraordinary reading of the Hamlet soliloquies. I shall never forget the performance, and it acquires all the deeper significance when one realises that it was his swan song’.Footnote127 The film The First of the Few—or Spitfire, as it was titled in the United States, where it was released just days before his death—was Howard’s last. Ironically, it retells the story of how the Spitfire, the British fighter aircraft used by the Royal Airforce to repel the Luftwaffe’s attacks during the Battle of Britain, was invented. The ‘few’ in the British title of the film played on Churchill’s speech describing the heroism of British airmen during the Battle of Britain: ‘Never was so much owed by so many to so few’. In his own way, Starkie also belonged to the ‘few’ when he founded the British Council in Spain, precisely at the time when the Luftwaffe was conducting air raids over Britain.

Relying on his experience as a theatre scholar and former director of the Abbey Theatre in Ireland, Starkie also created a play-reading circle at the Institute. The first play-reading session took place on 20 November 1941 with The Playboy of the Western World, a three-act play by Irish playwright John Millington Synge first performed at the Abbey Theatre in 1907. Starkie chose it precisely because ‘we had so often produced it at the Abbey Theatre, and in order to give our members a touch of picturesque dialect work’.Footnote128 He prescribed Terence Rattigan’s comedy French Without Tears for the following week, anticipating that ‘in this way we shall lead up to some of the Shakespeare plays such as Julius Caesar and Coriolanus, I hope, which would be rather apposite at the present moment’—the title character of the latter embodying everything that a liberal democracy like Britain’s stood against. Although it proved hard to acquire enough copies of the plays for all attendees, about six months later the Institute reported that the most successful plays had been Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, Oscar Wilde’s comedies and a stage version of Pride and Prejudice. They were in need of more theatrical material and requested dramas by George Bernard Shaw and more of Wilde’s plays.Footnote129

Materials for a photographic exhibition of British schools and universities were lost at sea (along with a radiogram, educational toys and Starkie’s own clothes) due to enemy action in February 1941.Footnote130 However, plans for the Institute’s first art exhibition, which eventually took place in March 1942, continued. Starkie reported that the exhibition brought in ‘a great many new members […] not only the artists and art students but also rich people and members of the nobility who up to this time were inclined to patronize Axis institutions’.Footnote131 An Exhibition of English Books opened by the Duke of Alba followed in 1943; it served to counter directly Nazi German book exhibitions and tours that had been organized in Spain since 1937 with the support of the Spanish Ministry of Education and the German Ministry of Propaganda, as detailed by historian Isabel Bernal Martínez.Footnote132 Fittingly, Alba’s later public tribute to Starkie read: ‘Supo vencer al principio de su gestión, con gran tacto, las dificultades inherentes a la mayor o menor germanofilia que entonces pudiera haber en España’.Footnote133

The British Institute’s work in Madrid during the 1940–1941 academic year provided firm ground for the British Council’s expansion throughout the country: Barcelona in 1943, Bilbao in 1944, Valencia in 1945 and Seville in 1946. Furthermore, the United States also looked to the British Council in Madrid for inspiration. In November 1942, the US set up the Casa Americana, a cultural centre separate from the US Embassy and complete with a library and a programme of cultural lectures; it would also house the US press office in Spain, the first of its kind in continental Europe.Footnote134

Yet, it was Starkie who managed to change the status of English in the Spanish national curriculum. He reported on his interview in July 1944 with the Spanish Minister of Education, José Ibáñez Martín, to the British Council Secretary-General, Arthur White. The significance of the meeting is such that the report merits to be quoted at length:

The most important point I treated with the Minister was the whole question of English in the Bachillerato. Bachillerato is the state examination which corresponds in England to School Certificate. Up to now, the Government has rendered it impossible for Spanish students all over the country to take English by the following proviso: All those who take French in the Bachillerato must continue with German as a second language. Those who take Italian may continue with either German or English as a second language. As 95% of Spanish students, male and female, take French, they are thus debarred from taking English as a second language, and thus there are comparatively few students of English in the schools, institutes and universities throughout the country. Very few take Italian, for they consider that it is an easy language for a Spaniard and they do not need to learn it, nor is it of any value commercially.

I have had many letters from all over the country from students, urging me to try and get this law reformed and have English put on an equal basis with German and French. I put this strongly before the Minister, and he immediately said that such a matter might have needed consideration, but since I was the person who put it forward he would accept my plea provided I put it in writing as an official document. So I am doing this, and I consider that if the Minister keeps his promise (it was a definite promise) I have gained a great victory for English in Spain and have destroyed one of the main advantages of the Germans here.Footnote135

The new educational guidelines established in 1944 lay the groundwork for the Council’s Memorandum of Understanding with the Spanish Ministry of Education signed in 1987 and the February 1996 agreement to integrate an English curriculum into the Spanish state school system and to ‘offer a bilingual Spanish-British education to children who do not come from privileged backgrounds’.Footnote136 In turn, the British Council asked the British Council School for its assistance and preparatory work for the project’s implementation, which started with a comparative study between the English National Curriculum and the Ley de Ordenación General del Sistema Educativo (LOGSE) coordinated by Maisi Sopeña, a former student and Head of Spanish in Primary at the British Council School, to ensure official recognition by both educational systems. Forty-four infant and primary state schools were initially selected across Spain. The agreement was later expanded to create a larger network of state bilingual schools operated in conjunction with the British Council, which in 2020 numbered eighty-nine infant and primary schools and fifty-seven high schools.Footnote137

Conclusion

Although Camilo José Cela, a Nobel Laureate in literature, immortalized his friend Starkie in his short story El violín de don Walter (published in 1948 and again in 1974) and renowned writer Javier Marías featured Starkie—whom he described as an ‘hispanista entusiasta y andariego’ that ‘conocía a todo el mundo del ámbito diplomático y de varios más’—in his recent novel Berta Isla,Footnote138 Starkie’s efforts as founder of the British Council in Madrid have not yet received the scholarly attention they deserve.

The British Institute which Starkie masterminded in Madrid in Britain’s darkest hour included a children’s school, an English language centre and a rich cultural programme featuring British as well as Spanish performers and traditions. Today, the British Institute remains active on all three fronts, thereby demonstrating the success of Starkie’s design beyond the war period. In addition, the Institute supported Britain’s intelligence activities in Spain during the war. These two research articles have brought together, for the first time, the different endeavours of the British Council in Madrid at the start of the war: education, intelligence and cultural diplomacy.

Starkie created a bilingual and bicultural co-educational school that followed a child-centred approach, was not religious but nevertheless offered a range of religious education to students, promoted the arts, cared for children’s health and attracted Spanish parents from the aristocracy and the liberal professions. The school remains a feature of the British Council’s work that is unique to Madrid, and Starkie’s foundational principles are still applied.

Starkie, who collaborated with the British Intelligence Service, and staff members of the British Council such as the school’s doctor, Martínez Alonso, who was an SOE agent, were crucial in setting up and implementing an escape route for Jews and Allied soldiers fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe. The appraisal of the British Council’s early institutional history in Spain must therefore include this important intelligence and humanitarian work.

While the British Institute School targeted future generations of Spaniards and their parents, through its English language centre the British Council’s work in cultural diplomacy aimed at appealing to the young, aspirational middle classes among private sector employees, government officials and future Spanish diplomats who studied English in order to take the entrance examination for a career in foreign diplomacy. This diverse target audience served potentially to foster friendship between the Council and the thankful middle classes who later ‘made it’ partly thanks to their knowledge of English.

The British Council as a cultural centre targeted the established elites in government and intellectuals, be they members of the RAE, musicians, doctors or writers. Starkie engineered a dual policy of attraction and rejection, one that made the British Council appealing to Spaniards while also offering veiled criticism of Nazi policies and propaganda. His flamenco parties at the Council and presentations on gypsy music served to display the British Council’s appreciation of Spanish cultural traditions while calling attention to the Nazis’ persecution of the Roma people. The Council’s cultural programme included musical soirées, scholarly lectures, exhibitions, play-readings and a regular tertulia.

In the academic year 1940–1941, when Britain was alone at war, Starkie set up the pillars to support the Council’s continued activities in Spain. He managed to do so with no official licence from the Spanish authorities at first, with no support from an unfriendly British ambassador and with little opportunity for advertisement, and despite facing espionage and counter-propaganda from the Germans and Italians, the logistical difficulties of war in Europe, and a Spanish society still torn by the consequences of the Civil War—hardly ideal conditions. Starkie’s strategy at the British Council, along with his personability, his credentials, his deep and nuanced knowledge of Spanish language and culture, and his personal network were paramount in overcoming the host of challenges he faced.

The two articles which make up the current study have shed light on a key figure in British Hispanism, perhaps the most successful Hispanist in the field of British cultural diplomacy since the Council’s foundation almost ninety years ago. Indeed, Starkie’s work in Madrid, especially his active engagement in the war of ideas during the Second World War, should be considered a form of creative output. That the eightieth anniversary of the Battle for Britain coincides with that of the foundation of the British Council in Spain reminds us of Starkie’s enduring contribution to Britain's war effort and British–Spanish relations, as well as of the great service that the British Council provided to British interests at a particularly difficult time in Britain’s history.

In 2020, the British Council risked financial ruin, having had to shut down forty-four of its forty-seven English language institutes and 195 of its 223 test centres due to the coronavirus pandemic, and it is in talks with the UK government over long-term emergency funding. In such a precarious time, it seems more necessary than ever to recall the origins of the Council’s second-oldest establishment in the world and its only children’s school, which demonstrates how in times of financial strain and international instability cultural diplomacy and educational engagement can play a role in strengthening the forces for peace and collaboration in the world.Footnote139

The approach followed in this research could usefully be applied to Portugal, where the British Council founded its first centre in the University of Coimbra, followed by that in Lisbon, with an official inauguration at the Salão Nobre of the Academia de Ciências in November 1938 attended by the Academia’s president, the British Ambassador and the Portuguese Minister of Education. Indeed, despite a few conference papers and a commemorative book published to mark the 70th anniversary of the British Council in Portugal, more work needs to be done on the origins in Portugal of what is the British Council’s longest surviving establishment.Footnote140

Additional avenues for future research include: exploring Starkie’s role as British Council director in Spain in the postwar period and during the early part of the Cold War, when Spain was to a large extent an international pariah (it did not join the United Nations until 1955); examining the links between British and American educational policy and cultural diplomacy in the latter half of the Second World War and into the mid 1950s in Spain; and investigating the British Council’s role in Spain’s transition to democracy during the 1970s and early 1980s.Footnote141

Indeed, in 1978, following an over week-long inspection of the Council’s Spanish operations, the organization’s Deputy Director-General wrote a policy review in which he stated that the Council’s main aim should be ‘to support Spain’s present leaning to a Western democratic model, and specifically to Britain, which is regarded as a prime example’.Footnote142 A teacher at the British Council in Madrid even gave ‘English lessons to the Prime Minister’s children in answer to a request we had from Sr Suárez via the Ambassador’.Footnote143 Although the war was long over by then, the British Council’s role in the ‘war of ideas’ continued and built on Starkie’s enduring legacy in Spain.Footnote*

Notes

* This work was supported by a British Spanish Society and Santander Universities scholarship. This article is dedicated to my parents, who encouraged me to think outside the box and trust the archives, and instilled in me a thirst for knowledge.

1 Walter Starkie, ‘The British Council in Spain’, BHS, XXV:100 (1948), 270–74 (p. 270).

2 Jacobo Fitz-James Stuart, ‘Walter Starkie’, in Ensayos hispano-ingleses: homenaje a Walter Starkie, ed. José Janés (Barcelona: José Janés, 1948), 5–6 (p. 6).

3 The first part of this article, entitled ‘Education, Intelligence and Cultural Diplomacy at the British Council in Madrid, 1940–1941. Part 1: Founding a School in Troubled Times', is published in an earlier Issue of the Bulletin of Spanish Studies.

4 The British Council in Spain began life under the name ‘British Institute’. In this article, I use these names interchangeably, including when referring to the British Council School as the British Institute School.

5 Walter Starkie to Sir Malcolm Robertson, 2 July 1941, The National Archives (TNA), BW 56/3.

6 Report, ‘Eduardo Martínez Alonso’, c.Spring–Summer 1943, TNA, HS 9/26/5; ‘Para-military Report’, 16 February 1943, TNA, HS 9/26/5.

7 M. R. D. Foot, SOE: An Outline History of the Special Operations Executive, 1940–46 (London: Pimlico, 1999), 328.

8 M. R. D. Foot, SOE in France: An Account of the Work of the British Special Operations Executive in France, 1940–1944 (London: Whitehall History Publishing, 2004 [1st ed. London: H. M. Stationary Office, 1968]); Dorothy Baden-Powell, Operation Jupiter: SOE’s Secret War in Norway (London: Hale, 1982); Alan Ogden, Sons of Odysseus: SOE Heroes in Greece (London: Bene Factum, 2012); David Stafford, Mission Accomplished: SOE and Italy, 1943–1945 (London: The Bodley Head, 2011); Roderick Bailey, Target Italy: The Secret War against Mussolini, 1940–1943: The Official History of SOE Operations in Fascist Italy (London: Faber & Faber, 2014); Thomas M. Barker, Social Revolutionaries and Secret Agents: The Carinthian Slovene Partisans and Britain’s Special Operations Executive (New York: Columbia U. P., 1990); John Earle, The Price of Patriotism: SOE and MI6 in the Italian-Slovene Borderlands During World War II (Lewes: Book Guild, 2005); and Roderick Bailey, The Wildest Province: SOE in the Land of the Eagle (London: Vintage, 2009).

9 See David Messenger, ‘Against the Grain: Special Operations Executive in Spain, 1941–45’, Intelligence and National Security, 20:1 (2005), 173–90 and, by the same author, ‘Fighting for Relevance: Economic Intelligence and Special Operations Executive in Spain, 1943–1945’, Intelligence and National Security, 15:3 (2000), 33–54.

10 Marta García Cabrera, ‘Operation Warden: British Sabotage Planning in the Canary Islands during the Second World War’, Intelligence and National Security, 35:2 (2020), 252–68. Designed in 1941, Operation Warden was a British plan to sink several German and Italian vessels off Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. It was not carried out.

11 ‘Report from Doctor Alonzo’, 1 (undated), TNA, HS 9/26/5.

12 See the following works by Émilienne Eychenne: Montagnes de la peur et de l'espérance: le franchissement de la frontière espagnole pendant la Seconde guerre mondiale dans le département des Hautes-Pyrénées (Toulouse: Privat, 1980); Les Montagnards de la liberté, 1939–1945: les évasions par l'Ariège et la Haute-Garonne (Toulouse: Milan, 1984); Émilienne Eychenne, Les Fougères de la liberté, 1939–1945: le franchissement clandestin de la frontière espagnole dans les Pyrénées-Atlantiques pendant la Seconde guerre mondiale (Toulouse: Milan, 1987); and Les Pyrénées de la liberté: le franchissement clandestin des Pyrénées pendant la Seconde guerre mondiale: 1939–1945 (Paris: Éditions France-Empire, 1983).

13 Josep Calvet, Huyendo del Holocausto: judíos evadidos del nazismo a través del Pirineo de Lleida (Lérida: Editorial Milenio, 2014). On the Perseguidos y salvados exhibition in Madrid, Warsaw, Krakow and New York, respectively, see the following websites: <https://thediplomatinspain.com/2019/01/el-centro-sefarad-israel-inaugura-la-exposicion-perseguidos-y-salvados/>, <https://cultura.cervantes.es/varsovia/es/perseguidos-y-salvados.-no-quer%C3%ADan-que-existi%C3%A9ramos/126401>, <https://cultura.cervantes.es/cracovia/es/Perseguidos-y-salvados/123930> and <https://cultura.cervantes.es/nuevayork/es/Perseguidos-y-salvados/129875> (all accessed 12 January 2021).

14 Tabea Alexa Linhard, ‘Routes of the Renowned and the Nameless: Clandestine Border-crossing at the Pyrenees, 1939–1945’, in Spain, World War II, and the Holocaust: History and Representation, ed. Sara J. Brenneis & Gina Herrmann (Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press, 2020), 125–37. There is no new archival material published in the chapter.

15 Bernd Rother, Franco y el Holocausto, trad. Leticia Artiles Gracia, rev. Gonzalo Álvarez Chillida (Madrid: Marcial Pons, 2005).

16 José Antonio Lisbona, ‘Beyond Duty: The Spanish Foreign Service’s Humanitarian Response to the Holocaust’, in Spain, World War II, and the Holocaust, ed. Brenneis & Herrmann, 153–181 (p. 175).

17 Louise London, Whitehall and the Jews, 1933–1948: British Immigration Policy, Jewish Refugees and the Holocaust (Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2000); and Tom Lawson, ‘Review: Whitehall and the Jews, 1933–1948: British Immigration Policy, Jewish Refugees and the Holocaust’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 13:4 (2000), 431–432.

18 Diana Packer, ‘Britain and Rescue: Government Policy and Jewish Refugees, 1942–1943’, Doctoral dissertation (Northumbria University, 2017).

19 Note prepared by the Foreign Office regarding the Government's plans to assist the Jewish people, 19 January 1943, Churchill Archive 20/93A/69-71.

20 Sherri Greene Ottis, Silent Heroes: Downed Airmen and the French Underground (Lexington: Univ. Press of Kentucky, 2001), 124; M. R. D. Foot & James M. Langley, MI9: The British Secret Service that Fostered Escape and Evasion 1939–1945, and Its American Counterpart (London: Futura Publications, 1980), 77 & 81.

21 Eduardo Martínez Alonso, Memoirs of a Medico (Garden City: Doubleday, 1961), 198–99. This work was published in Britain as Adventures of a Doctor (London: Hale, 1962).

22 Pavel Hartmann, ‘The Allied Powers (War Service) Act’, The Modern Law Review, 6:1–2 (1942), 72–75.

23 Martínez Alonso, Memoirs of a Medico, 193.

24 Matilde Eiroa San Francisco, ‘Refugiados extranjeros en España: el campo de concentración de Miranda de Ebro’, in Los campos de concentración franquistas en el contexto europeo, ed. Ángeles Egido & Matilde Eiroa, Ayer, 57 (2005), 125–52 (p. 125). See also Concha Pallarés & José María Espinosa de los Monteros, ‘Miranda, mosaico de nacionalidades: franceses, británicos y alemanes’, in Los campos de concentración franquistas en el contexto europeo, ed. Egido & Eiroa, 153–87.

25 Martínez Alonso, Memoirs of a Medico, 193–94.

26 Martínez Alonso, Memoirs of a Medico, 193. However, Eiroa San Francisco believes that the camp was in fact built to host between 2,000 and 2,500 inmates.

27 Martínez Alonso, Memoirs of a Medico, 193.

28 Martínez Alonso, Memoirs of a Medico, 197.

29 ‘Martínez Alonso, Eduardo’, TNA, HS 9/26/5, 4.

30 AD/W to C.D., 11 February 1942, TNA, HS 9/26/5.

31 H to H/X, 23 October 1941, TNA, HS 6/968.

32 ‘Draft Telegram from British Ambassador Madrid to Minister Madrid’, 22 October 1942, TNA, HS 6/968.

33 ‘Nominal roll of “Canadian” Ps. O. W. evacuated from Miranda on the 17-8-41’, TNA, HS 6/968.

34 Martínez Alonso, Memoirs of a Medico, 198.

35 ‘Report from Doctor Alonzo [sic]’, TNA, HS 9/26/5, 4.

36 ‘Recommendation for the Award of the King’s Medal for Service’, (undated), TNA, HS 9/26/5.

37 H. M. to D/CE.5, 28 January 1942, TNA, HS 9/26/5.

38 Martínez Alonso, Memoirs of a Medico, 195.

39 Jacqueline Hurtley, Walter Starkie: An Odyssey (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2013), 259.

40 Alma Starkie speaking on a radio show by Richard Fitzpatrick & Tim Desmond, ‘Tearoom, Taylor, Saviour, Spy’, Documentary on One, RTÉ Radio 1, 9 July 2016; available online at <https://www.rte.ie/radio1/doconone/2016/0624/797910-tearoom-taylor-soldier-spy/> (accessed 13 January 2021).

41 Denis Smyth, ‘Hillgarth, Alan Hugh (1899–1978)’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2004), online edition, 28 May 2015, <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/31233> (accessed 15 February 2021).

42 Duff Hart-Davis, Man of War: The Secret Life of Captain Alan Hillgarth: Officer, Adventurer, Agent (London: Century, 2012), 216.

43 Ángel Viñas, Sobornos: de cómo Churchill y March compraron a los generales de Franco (Barcelona: Crítica, 2016).

44 ‘Sra Alonso’, TNA, HS 9/26/5, 2.

45 Artemis J. Photiadou has recently shown that the British Council supported the RVPS’s attempts in Spring 1941 to move away from looking like a detention camp and supplied works by several well-known British authors, including Brontë, Dickens, Austen, Kipling and Yeats, though most arrivals were not able to read English. See Artemis Photiadou, ‘British Interrogation Culture from War to Peace, 1939–1948’, Doctoral dissertation (London School of Economics and Political Science, 2019), 33. See also Artemis Photiadou, ‘The Detention of Non-Enemy Civilians Escaping to Britain During the Second World War’, The Historical Journal (forthcoming).

46 ‘Report from Doctor Alonzo [sic]’, TNA, HS 9/26/5, 4.

47 Eduardo Martínez Alonso to Pío Baroja, TNA, HS 9/26/5.

48 Eduardo Martínez Alonso to Pío Baroja, TNA, HS 9/26/5.

49 Eduardo Martínez Alonso to Pío Baroja, TNA, HS 9/26/5.

50 ‘Application form’, TNA, HS 9/26/5, 2.

51 Martínez Alonso, Memoirs of a Medico, 217.

52 ‘Application form’, TNA, HS 9/26/5, 3.

53 ‘Para-military report’, 16 February 1943, TNA, HS 9/26/5. 2.

54 ‘Form PR.14’, 16 November 1945, TNA, HS 9/26/5; RWL/N to AD/B, ‘Honours and Awards: Iberia’, 19 November 1945, TNA, HS 9/26/5.

55 Patricia Martínez de Vicente, interview with the author, 13 March 2016. See also Patricia Martínez de Vicente, La clave Embassy: la increíble historia de un médico español que salvó a miles de perseguidos por el nazismo (Madrid: La Esfera de los Libros, 2010).

56 TNA, KV 2/2823 and KV 2/2824. See Terry Philpot, ‘Burns, Thomas Ferrier (1906–1995)’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edition, 5 January 2012, <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/60363> (accessed 13 January 2021). In early January 1941, Starkie went on a tour of Andalucía with Burns, visiting Granada, Málaga, Algeciras, Jérez and Seville, in order to explore the possibility of extending the Council’s activities to the south of Spain. See the letter from Walter Starkie to Lord Lloyd, 15 January 1941, TNA, BW 56/3.

57 Jimmy Burns, Papa Spy: Love, Faith and Betrayal in Wartime Spain (London: Bloomsbury, 2010), 253.

58 Douglas Brown, ‘Should an Ambassador Tell?’, Reuter Feature no. 3835/D, TNA, BW 56/7, 3.

59 Thomas Burns, The Use of Memory: Publishing and Other Pursuits (London: Sheed & Ward, 1993), 103.

60 Burns, Papa Spy, 252.

61 Alma Starkie’s letter to the editor, ‘Aclaración sobre Walter Starkie’, El País, 1 March 1986, <https://elpais.com/diario/1986/03/01/opinion/510015615_850215.html> (accessed 22 February 2021).

62 ‘El hospital Anglo-Americano pasará a depender del Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia’, El País, 22 February 1986, <https://elpais.com/diario/1986/02/22/madrid/509459062_850215.html> (accessed 13 January 2021).

63 Email from Theodore Pahle to the author, 14 September 2017. See also Pablo León Aguinaga, ‘El cine norteamericano y la España franquista, 1939–1960: relaciones internacionales, comercio y propaganda’, Doctoral dissertation (Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2009); and Pablo León Aguinaga, Sospechosos habituales: el cine norteamericano, Estados Unidos y la España franquista, 1939–1960 (Madrid: CSIC, 2010).

64 Email from Theodore J. Pahle to the author, 14 September 2017.

65 Email from Theodore J. Pahle to the author, 24 September 2020.

66 Email from Theodore J. Pahle to the author, 14 September 2017.

67 Walter Starkie to Lord Lloyd, 17 September 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.

68 Walter Starkie to Lord Lloyd, 17 September 1940, TNA, BW 56/2.