ABSTRACT

This study offers a grounded theory of ‘new ways of working’ (NWW), an organizational design concept of Dutch origin with a global relevance. NWW concern business solutions for flexible workspaces enabled by digital network technologies. Theoretically, NWW are analysed with reference to Lefebvre’s theory on the ‘production of space’ and are defined along three dimensions: the spatiotemporal ‘flexibilization’ of work practices, the ‘virtualization’ of the technologically pre-defined organization, and the ‘interfacialization’ of meaning making in the lifeworld of workers. Empirically, NWW are explored in a case study of an insurance company which in 2007 radically implemented NWW. The case study consists of a longitudinal – before and after implementation – research based on ethnographic fieldwork, conducted in 2007 and 2010. The article contributes with a conceptual framework for the analysis and management of NWW, and highlights contradictions and ambiguities in the implementation and appropriation of this innovative organizational design.

1. Introduction

Spatiotemporal designs and practices of organizing have changed drastically together with the rise of networked digital information and communication technologies (ICT). These organizational changes have increasingly been implemented with the help of specialized consultancy agencies, which offer pre-defined so-called best business practices for new material-virtual organizational arrangements. This study conceptualizes this category of new work practices as new ways of working (NWW), with reference to innovative organizational designs and to Henri Lefebvre’s seminal work, The Production of Space (Lefebvre [Citation1974] 1991). Empirically, this study explores NWW with an ethnographic case study dealing with the Dutch subsidiary of a multinational insurance broker which in 2007 radically implemented NWW. This change was guided by a Dutch consultancy agency, Veldhoen & Company (V&C), which pioneered NWW in the Netherlands (Veldhoen Citation2005). The changes included the introduction of new work practices regarding open, flexible, virtual, and paperless offices, which contrasted with the conventional fixed and cellular office spaces of the company. The case study explores the backgrounds, the material settings, the technologies, the professional work ideologies, and the user practices which characterize NWW.

An early and inspiring design of NWW was developed in the mid-1990s by Erik Veldhoen’s business consultancy firm, in the case of the notorious Interpolis building (1996) in the Netherlands (Derix Citation2003; Veldhoen Citation2005). Following this and other examples, in the first decade of the twenty-first century in the Netherlands NWW became a popular business trend (Gorgievski et al. Citation2010; Blok et al. Citation2012; Brunia, de Been, and van der Voordt Citation2016). Many consultancy agencies offer a range of material-virtual design solutions, under the heading of NWW or comparable business vignettes such as ‘activity-based working’ (Hoendervanger et al. Citation2016) or ‘distributed work’ (Harrison, Wheeler, and Whitehead Citation2004). In consultancy terms, NWW are often summarized as bricks, bytes, and behaviour changes, indicating the integrated management of spatiotemporal, technological, and organizational cultural changes (Harrison, Wheeler, and Whitehead Citation2004; Veldhoen Citation2005; Bijl Citation2007; Baane, Houtkamp, and Knotter Citation2011). What is particularly novel about these changes is not so much the technological aspects but the new phase of organizational design in which technological and architectural dimensions are being integrated, commodified, and presented in a systematic way, thus furthering new kinds of social workspaces. These innovative designs are believed to improve organizational efficiency and effectiveness and to align better with the requirements of the information age (Castells Citation2001).

NWW can be regarded as part and parcel of the wider trend of workspace differentiation and flexibilization (Felstead, Jewson, and Walters Citation2005). This transformation encompasses the flexible use of home workspaces in terms of teleworking (Cooper and Kurland Citation2002; Peters and Heusinkveld Citation2010; Sewell and Taskin Citation2015) and the flexibilization of office spaces in terms of hot-desking or nomadic working (Chen and Nath Citation2005; Bosch-Sijtsema, Ruhomäki, and Vartiainen Citation2010; Hirst Citation2011), as well as mobile working en route between all of these workspaces (Brown and O'Hara Citation2003; Hislop and Axtell Citation2009; Kingma Citation2016). More generally, this study is inspired by a renewed interest in the material dimension of organizations (Kornberger and Clegg Citation2004; Dale and Burrell Citation2008; Leonardi and Barley Citation2008; Hancock and Spicer Citation2011; Wasserman and Frenkel Citation2011; Orlikowski and Scott Citation2008). While in this literature, space and technology are usually treated separately, the study of NWW requires the combined analysis and study of the interaction between space and technology. With this requirement in mind, this study examines the relationship between space, technology, and organizing, and seeks to contribute to the literature on flexible working with a phenomenology of NWW. In this respect, it is directed towards the development of a conceptual framework based on Lefebvre’s approach. The great advantage of this approach is that it makes it possible, as argued by for instance Watkins (Citation2005) and Taylor and Spicer (Citation2007), to combine the often separately studied physical, power, and experiential dimensions of organizational space. In short, this article contributes to the literature on flexible working (1) empirically with a case study of NWW as a novel organizational design, (2) theoretically with an analysis of the frictions between the three Lefebvrian perspectives and how they are dealt with by managers and knowledge workers, and (3) an understanding of how space and technology are organizationally brought together and constitute a new meaningful ensemble typical of contemporary work cultures.

Firstly, the sensitizing concepts regarding NWW and the theoretical background are outlined. Subsequently, the case study and methodology are introduced. In the second part, I move to the design of a new office space and NWW, as conceived by the consultants and managers. After that, I analyse the changes in work practices and the creative and critical appropriation of NWW by the employees. Finally, the dynamic and processual character of the Lefebvrian production of NWW is discussed.

2. New ways of working

As a new workspace and organizational design concept, NWW were initiated in the Netherlands around 1994. NWW were pioneered by Erik Veldhoen and his consultancy firm but were not the result of a momentary and complete design by one person or one agency (Derix Citation2003; Veldhoen Citation2005). Rather, this business concept should be regarded as the outcome of a gradual process, developed over a decade. NWW turned into a business movement with a core of enthusiastic architects, business consultants, and ICT developers, who all believed in this promising material innovation in relation to the ICT revolution of the 1990s (Castells Citation1996). Furthermore, although initially developed together with the Interpolis insurance company, many imitations and variants of NWW were later developed.

Although the V&C and Interpolis case should be regarded as an original and leading example, there were other initiatives. Some of these only vaguely resembled the V&C approach but others compared strikingly to this, such as the office designs by Duffy and the British design agency DEGW (Duffy Citation1997, Citation2000; Dale and Burrell Citation2008; Wainwright Citation2010). Moreover, historically, NWW are by no means new. Designs of mobile offices, paperless offices, videoconferencing, and flexible workplaces all originate from the end of the 1960s and the early 1970s (van Meel Citation2011). Before the 1990s, however, these designs were merely experimental and not developed on a significant scale.

But in the first decade of the twenty-first century in the Netherlands, NWW were widely established as a major business trend, and described in business guides and textbooks (Veldhoen Citation2005; Bijl Citation2007; Baane, Houtkamp, and Knotter Citation2011). In itself, the representation of NWW in textbooks can be regarded as part of what Lefebvre called the ‘abstract space of capitalism’ – i.e. an instrumental space in which ‘the world of commodities is deployed, along with all that it entails: accumulation and growth, calculation, planning, programming’ (Lefebvre [Citation1974] 1991, 307) (see also Dale and Burrell Citation2008, 13 ff). This abstract space offers a coherent and impressive but often deceptively transparent insight in production spaces. In the textbooks, NWW are often advocated as contributing to an array of business benefits – networking within and between organizations, cost- and space-savings, productivity, quality, creativity, collaboration, communication, empowerment, transparency, trust, and equivalence – culminating in overall employee and customer satisfaction. Indeed, NWW are sometimes presented as a cure-all for contemporary organizational problems. In contrast with these (over)optimistic expectations, there is hardly any scientific proof of the actual business benefits (Blok et al. Citation2012). This article seeks to further a critical understanding of what NWW actually are about in organizational practice.

What NWW have in common is a totalizing approach – here understood in the Lefebvrian sense of unified perspectives – in which roughly three dimensions are simultaneously integrated: the spatial, the technological, and the cultural. For example, in the early phases of NWW, Veldhoen argued that this development was not merely about new work processes, new facilities, or the adoption of new technologies (Derix Citation2003, 14–17; Veldhoen Citation2005):

The challenge of the future is in connecting the physical, virtual and mental space, and in the way we do that. The virtual and physical environment have to be tuned toward each other. And you need a mental environment, a mindset to be able to work there adequately: what are the agreements, the codes, how do we assess each other based on performances? These three worlds should not be understood separately, they are unified. (Veldhoen cited in Derix Citation2003, 49; my translation)

V&C’s ideas were developed in a gradual process of interactive, incremental, and agile organizational change. Three phases can be discerned (Derix Citation2003): developing the Interpolis plans (IP phase, 1994–1996), actualizing the Interpolis office concept (IOC phase, 1996–2001), and elaborating the new work practices into the Interpolis way of working (IWW phase, 2001–2003). In the IOC phase, three favourable conditions came together. Interpolis not only wanted to create new buildings, and not only could this quest for new buildings be combined with the ICT revolution, but both these developments were connected with a revolutionary change in the market philosophy of the insurance company. This change in philosophy also concerned a reversal of logics, from a control-based approach to services to a process and trust-based approach (Derix Citation2003, 28, 54, 58) (cf. ).

Table 1. Shift in organizational logics typical of NWW Ideology (derived from Derix Citation2003; Veldhoen Citation2005).

Most significantly, this meant that the insurance company would start from the premise that customers are trustworthy (unless proven otherwise). Interpolis no longer required proof from its clients in advance, and paid their damage claims in quick and lean procedures, only checking on a sample of the claims after the payments. This trust and responsibility of clients perfectly matched with the trust and responsibility given to employees in NWW (Veldhoen Citation2005, 71). The responsibilities of employees not only concerned decisions about where and when to work, or how to decide about client claims, but also involved rewards systems based on output (instead of presence), a shift in organizational focus from hierarchical positions to tasks and project roles, and coaching (instead of controlling) leadership roles.

In the IWW phase, the elaborations included a redesign of intermediary office spaces, starting with the redefinition of the restaurant from a place where you would incidentally eat and drink into a multifunctional space where you could also meet and do various work activities. Intermediary spaces would no longer be conceived as mono-functional (transport) spaces, but were turned into informal lounge areas, shared spaces, facilitating (tele)work activities. This design included the clustering of activities and the use of open staircases for the vertical integration of work areas. The thinking about intermediary spaces ultimately evolved into the metaphor of the company building as a city, with a central role for plazas (Derix Citation2003, 43, 48; Veldhoen Citation2005, 184–185). The plaza became a transition zone between the various work floors on the one hand and working somewhere outside the company building on the other hand. This idea connects with Fleming and Spicer’s (Citation2004) discussion of the blurring of inside-outside boundaries, in which private activities are drawn inside the workspaces and organizational norms are encouraged outside work.

This radically flexible alternative to fixed workspaces was enabled by the decoupling of information processes from spatial designs (Derix Citation2003, 39; Veldhoen Citation2005, 50–52) (cf. ). The flow of paper no longer guided spatial design. Instead, the design was guided by the extent to which specific work activities require particular combinations of individual (or collaborative) and physical (or virtual) work (Veldhoen Citation2005, 151–154). Ultimately, NWW are characterized by an activity-based work order, integrating and clustering various types of activity, including, in V&C terminology, individual cockpits, team tables, lounge areas, silence areas, comfort rooms, meeting rooms, and various sorts of open workplace (Veldhoen Citation2005, 77). provides an example (the so-called ear-chairs) of a new creative workplace design at the Interpolis building.

In all cases, V&C and Interpolis devoted special attention to the human scale of the work environments, which were split up into transparent, small-scale compartments and ‘club houses,’ comfortably equipped but with creative designs, to generate a sense of belonging and identification ().

In fact, in the V&C philosophy, art, and an artistic approach to work practices are understood as integral to satisfaction, self-realization, and pleasure in work (Veldhoen Citation2005, 4–5). By extension, Veldhoen (Citation2005, 215–224) argued that NWW contained the emancipatory moments of a social movement.

This way V&C promotes the idea of ‘smart working’ in a ‘smart building’, and seeks to further cultural change by means of spatial design (Veldhoen Citation2005). This philosophy matches with the idea of ‘generative buildings,’ where ‘function follows form,’ and which are designed to encourage workers to be ‘creative and passionate’ (Kornberger and Clegg Citation2004). Generative buildings are characterized by ‘chaotic, ambiguous, and incomplete space’. Because in NWW spatial design is connected to organizational change objectives, the managers and consultants in the Interpolis case were aware of the need to convince employees and to involve them in the change process. Along the way they definitely encountered scepticism and resistance, which are often marginalized as an aspect of change, which ‘inevitably always generates insecurity and anxiety’ (Derix Citation2003, 49). To deal with the insecurities, the plans were developed in interaction with user groups, discussed in work conferences, and enthusiastically communicated with illustrations and mock-ups.

The ideas about NWW as represented by Derix (Citation2003) and Veldhoen (Citation2005) constitute a coherent business theory for how NWW can be organized. In the case of Veldhoen (Citation2005), these ideas are even linked to scientific theories, notably the work of Castells (Citation1996) about the information age, Mitchell (Citation2000) about smart buildings, and Senge et al. (Citation1999) about learning organizations. Such eclectic connections make a clear case for the scientific relevance of NWW. However, what is needed in order to systematically study the complexity of the interrelations between spatiotemporal, technological, and social change processes is a ‘unitary theory’ which understands space both as a social product and as producing social relations (Lefebvre [Citation1974] 1991, 11–12). Lefebvre’s The Production of Space ([Citation1974] 1991) offers such a sophisticated theorization of space, a connection also suggested by others (Wainwright Citation2010; Wapshott and Mallett Citation2012; Uolamo and Ropo Citation2015; Kingma Citation2016). Lefebvre’s theory arguably makes it possible to combine the three organizational ‘pillars’ of NWW as indicated by Veldhoen – namely the physical, the virtual, and the mental – at least, if we see these pillars not as particular spaces, aspects or influences, which stand apart from and interact with each other, but as three perspectives on the same material reality. In fact, Lefebvre explicitly rejected the prevalent, but in his view false, distinction between the ‘mental’ and the ‘spatial’ (Lefebvre [Citation1974] 1991, 6).

Lefebvre’s theory of space revolves around three spatial perspectives which address the interrelationships between the epistemologically distinct ways in which actors relate to space. In other words, the perspectives represent three ways of knowing or experiencing the same material reality. Lefebvre distinguishes analytically between the ‘perceived’, the ‘conceived’, and the ‘lived’ space. The taken-for-granted nature of spatial environments is addressed in the spatial practices of the ‘perceived space’, which we routinely reproduce during the course of everyday life (Lefebvre [Citation1974] 1991, 33; Watkins Citation2005). This perspective on space is gained through experience, ‘which is understood as practical perception and common sense’ (Shields Citation1999, 163). This perspective can be related to Veldhoen’s physical pillar which he associates with ‘social interactions’ (Veldhoen Citation2005, 175–191). From this perspective, one may argue that in NWW, flexibility has become a new standard for spatiotemporal interaction (Wainwright Citation2010, 216).

Lefebvre’s conceptions further address power relations by comparing the confrontations between the explicitly designed spatial regimes of the conceived space with the actual user practices of the perceived space on the one hand and the subjective, alternative meanings of the lived space on the other hand (Kingma Citation2008; Peltonen Citation2011; Wasserman and Frenkel Citation2011). This emphasis is relevant in the context of NWW, because the explicit organizational designs for NWW are usually provided by organizations, while it is at the same time crucial to include the user experiences.

Lefebvre’s ‘conceived space’ can be related to Veldhoen’s virtual pillar, which he associates with the ‘management of information’ (Veldhoen Citation2005, 163–174). From this perspective, one may argue that virtuality represents the coded space of NWW, as professed in the official accounts on work practices and ICT by various professionals, such as architects, engineers, software developers, consultants, and managers, who explicitly compose a dominant outline of the organization which is imposed on (knowledge) workers. The connections between these professional accounts and modes of production are important. In NWW, virtualization refers to the tendency to predefine organizational order by the algorithms of digital systems which connect workers and business units and inform and supervise them (Sotto Citation1997; Shields Citation2003; Boersma and Kingma Citation2005). As discussed by Sotto (Citation1997, 37), an ICT system can be seen as ‘a specific mode of representing the world that affects whatever it absorbs’. Workers have to deal, in one way or another, with the feedback loops generated by information systems. According to Lefebvre ([Citation1982] 2003, 65), ‘logic which becomes part of practice’, for instance in business strategies or in software, ‘provides and ensures homogeneity in knowledge and practice’ … ‘but it never [totally] succeeds in this’. The ideal virtual order represented by ICT systems has to be adapted to specific organizational contexts, and has to be made effective – but can also be undermined – by users who connect to the system with technological interfaces.

Lefebvre’s ‘lived space’ can be related to Veldhoen’s mental pillar, which he associates with the ‘creation of culture’ (Veldhoen Citation2005, 191–207). From this perspective, one may argue that the use of interfaces refers to the creative side of NWW, where the informal but reflexively constituted meanings of work practices are increasingly experienced through the use of technological interfaces, such as smartphones and laptops, and their associated images and symbols. The use of interfaces may reveal how work practices are tied to what Lefebvre calls ‘social imaginaries’, in which the imagination seeks ‘to change and appropriate’ space (Lefebvre [Citation1974] 1991, 39). This may, for instance, be relevant for the construction of organizational identities. The recoded versions of spaces and artefacts, and critiques and alternatives to the dominant virtual order, are important aspects of this (Wasserman and Frenkel Citation2011; Wapshott and Mallett Citation2012). In NWW, interfacialization refers to the tendency for organizational life to be mediated by the use of interfaces between workplaces on the one hand and digital infrastructures on the other hand. Workers have to make sense of their equipment, of their work and of each other, in view of this mediating role.

As major interpreters (Shields Citation1999; Elden Citation2004; Goonewardena et al. Citation2008) of Lefebvre’s work have stressed, the perspectives of Lefebvre’s triad always operate together, presuppose one another, and influence each other in continuous processes of spatial production. Lefebvre’s objective was to understand and analyse the dynamic processes of everyday spatial production rather than the representation of spatial formations (Beyes and Steyaert Citation2012). In processes of change the lived space can also be understood as mediating (reaffirming, fulfilling, modifying, and challenging) between everyday work practices and professional organizational designs (Zhang Citation2006).

From such a Lefebvrian approach, NWW can thus be redefined in terms of organizational practices which result from interactions between the flexibilization of work routines (perceived space), the virtualization of pre-defined technological organizational orders (conceived space), and the interfacialization of the lifeworld of workers (lived space). This way, we may understand Veldhoen’s practical classification of NWW as resulting from interactions between the contradictory dimensions of Lefebvre’s spatial triad. Through an empirical case study, we sought to learn what constitutes NWW in an actual organizational context.

3. The case study and methods

Beware

The case study at Beware (a pseudonym) concerned a longitudinal study of the relocation and simultaneous introduction of NWW in a Dutch subsidiary of an international insurance broker. The case study constitutes an ‘extreme’ as well as a ‘paradigmatic’ case (Flyvbjerg Citation2006, 230–233). It is an extreme case because it was the management’s intention to become as flexible, virtual, and paperless as possible. The case is paradigmatic, because Beware adopted in 2007 the innovative V&C business concept for NWW, as discussed in the theoretical section.

The move and NWW came at a time when the company was recovering from drastic events. At the end of the 1990s, the established Dutch insurance broker was taken over by a publicly listed, big multinational B2B insurance broker and consultancy firm which, in 2005, operated in over 100 countries (Annual report Beware 2006). The take-over was shortly followed, in 2004, by a dramatic organizational crisis. The Dutch branch was seriously affected and downsized, from 580 to about 360 employees. For the Dutch management and employees the straightforward American business style, and especially the layoffs, was a shocking experience. Many employees expected life-time employment, were committed to a respectable brand, a protestant spirit, and a paternalistic leadership. Furthermore, the market for insurance brokers would become more dependent on client fees rather than on the commissions which had been the primary source of revenue. Management sought to develop a new business strategy that would better fit the new market conditions. This pressing situation also motivated the management to embrace NWW.

Methods

The case study consisted of two research phases. The first phase lasted about six months and started in early 2007, before the relocation. The second phase started in early 2010 and also took about six months. The overall research strategy involved ethnographic fieldwork by Master’s students (see acknowledgements). This fieldwork relied on a variety of sources, including participation, observation, (in)formal interviewing, and documents. The ethnographic approach means, as argued by Neyland (Citation2008), that we sought to understand NWW based on the views and experiences of the people involved. In the first research phase, the focus was on the implementation of NWW and on the initial responses and sense-making by the employees. In the second phase, the change was more or less consolidated and the focus shifted to the appropriation and everyday spatialization of NWW by the employees.

Participant-observation proved valuable for the monitoring of the introduction of NWW and identifying key informants. Observations and pictures were important for capturing the way employees actually used the workspaces. Participation was in the first phase facilitated by the role of one of the students as a part-time employee, and included the attendance of meetings of various project groups, meetings with consultants, and some training sessions. Documents provided formal knowledge about the designs, work processes, and organizational context, and proved valuable for validating statements of interviewees.

Interviews were a key for generating accounts of the backgrounds, motives, experiences, and personal opinions of employees. The fieldwork included numerous informal and 25 formal interviews: 14 interviews in the first and 11 interviews in the second phase (). The formal interviews each took about 60–90 minutes and were recorded and transcribed. Regarding the employees we targeted, we followed the principle of maximum variation sampling (Ritchie and Lewis Citation2003). Interviews were guided by a semi-structured topic guide. The interviewees are addressed with pseudonyms and the author translated the quotes ().

Table 2. Interviews with Beware workers.

Data analysis was based upon the principles of ‘grounded theory’ (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998; Bernard Citation2002, 463 ff; Suddaby Citation2006). These principles include the methods of constant comparison and theoretical sampling, which implies that the research evolved through an iterative process in which the researchers selected informants and developed conceptual categories, filling them with data until a certain level of saturation of the categories was reached – i.e. until the insights became increasingly repetitive. In this way, data collection and analysis were a simultaneous process.

Grounded theory is first and foremost directed at making statements about how actors interpret and construct reality. Grounded theory does not imply that one can do without literature and substantive theory (Suddaby Citation2006). The research was clearly guided by the theoretical notions outlined in the previous section. The following analysis focusses on how each Lefebvrian perspective relates to the other perspectives and contributes to the production of NWW at Beware.

4. NWW at Beware: the conceived space

This section discusses the spatial logic of NWW at Beware, as conceived by the consultants and managers. This kind of account is typical of Lefebvre’s conceived space. In Lefebvre’s theory, representations of space are constructed out of symbols, codifications, and abstract concepts, as used by spatial professionals such as designers, IT- specialists, and mangers (Lefebvre [Citation1974] 1991, 33, 38–39). The conceived space refers to the knowledge of and discourses on workspaces, which are related to the instrumental use of these spaces. This draws our attention to how, in the planning and design processes, knowledge and power are related to material constructions (Taylor and Spicer Citation2007, 335). Since organizations, as argued by Meyer and Bromley (Citation2013), involve rationalized decision-making about organizational identities and instrumental means-ends relationships, Lefebvre’s conceived space is of special significance for organization processes. In the case of NWW, the professional discourses explicitly promoted the virtualization of business information in order to enable a space- and time-independent mode of working. As will be demonstrated in this section, the conceived space of NWW contributes in two ways to the virtualization of work practices.

Firstly, the managers, consultants, and programmers inscribe desirable behaviour in the virtual system and spatial arrangements. Technological artefacts, workspaces, and work facilities are associated with ‘scripts’ (Akrich Citation1992; Suchman Citation2007), informing users about what actions should be undertaken, when, where, and how; such scripts might be understood as embodied ‘user manuals’. The more or less explicit rules regarding for instance the clean-desk policy, team work, and information sharing could be called upon if and when an employee did not move within the margins of the conceived space. In fact, in V&C’s approach of NWW employees are expected to confront each other with respect to apparent rule-breaking behaviour.

Secondly, the conceived space sets constraints on the use of the work environment, by facilitating and privileging work practices that are supposed to be in line with virtualized working and discouraging or hindering practices which are not. Beware’s management therefore expected, aided by instructions and training sessions, that the larger part of employees would more or less tacitly understand and comply with the suggested virtual framework and the range of workplace options. The analysis of the conceived space addresses the pre-defined spatio-technological order, and focuses on the discourses, and designs regarding Beware’s virtualized workplace environment. Because the design of the conceived space heavily draws upon the abstract space of NWW, as manifest in the textbooks and reports, the analysis of the conceived space is somewhat clinical compared to the perceived and lived spaces. In their accounts and legitimations, the consultants and managers frequently referred to the abstract logics of NWW as expressed in official documents such as Veldhoen’s book (Veldhoen Citation2005) (cf. ).

Management objectives

An employee survey conducted in 2006 to prepare the changes revealed that in the Dutch subsidiary, employees strongly identified with their departments instead of with the company as a whole. Furthermore, communication between the departments was virtually non-existent. In 2006, the change in business strategy was launched. This involved the transformation of Beware from a traditional insurance broker into a business consultancy agency specializing in risk management. Knowledge sharing was regarded key for this change. These intended changes pushed the need for virtualization and a place- and time-independent way of working.

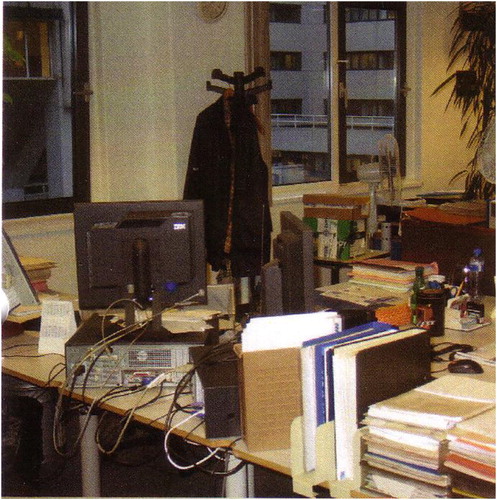

Additionally, for the Dutch subsidiary, there was a need for a relocation because the old office building had become too large in view of the downsizing. The old office building was further characterized by an old-fashioned cell structure with highly personalized offices and reliance on paper and filing cabinets ().

Figure 3. ‘Paperfull, dedicated office’ at Beware before the move, 2006. By courtesy of Karin Bosman.

The move to the new building was seized as an opportunity to radically change Beware’s physical workspaces and organizational culture. Initially, some employees were, in talks among each other, openly suspicious about the intended changes. They feared that virtualization might increase management control over employees as well as intensify the work load. It might also motivate further layoffs. Soon after the initiation of the changes, however, such openly suspicious stories waned.

The consultants

In 2006, the Beware management commissioned V&C to develop a proposition for an interior office design that reflected transparency, client orientation, output measurement, cooperation, and communication beyond team or department boundaries (V&C Project Proposal, 2007).

At Beware, as in each V&C case, the change process started with an analysis of the actual occupancy rate and use of office space, the (inter)actions that define the primary work processes, and the digital technologies required to achieve a space- and time-independent way of working. User groups were involved in developing the new office designs. In V&C’s view, an ambitious redesign of the physical and virtual environment remained meaningless if the mental work environment would not align with it (Veldhoen Citation2005, 81).

In each business case, V&C sought to make information independent of place and time, the ‘Archimedian point’ of the organizational philosophy (Veldhoen Citation2005, 51). V&C redesigned work processes on the basis of ‘just in time’ and ‘just in place’ management, meaning a shift in orientation from bringing information to getting information, where and when it was needed. From this reversal in the logic of information flows, a new experience of space and time originated. Although not dismissed altogether, V&C broke with paper as the basic carrier of information. In all these respects, the design objectives for NWW at Beware were directly modelled after V&C’s prototypical but much larger Interpolis building, as discussed in the theoretical section.

Virtualization

The V&C consultants split the change steps into their understanding of the physical, the virtual and mental aspects of the work environment. For each aspect, a project group was organized.

The first objective was to create a paperless office, where all files would be digitalized. Scanning and digitalizing all existing files and emptying the filing cabinets were the responsibility of the virtual project group, dominated by ICT employees. This group had to manage the ICT infrastructure built up with the AS/400 Silver Lake IBM server, scanning machines, some multi-purpose printers, mobile and smart phones, laptops, the company’s closed-circuit intranet, Microsoft Office for chat, email, word-processing, spread sheet and presentation functions, and a content management system, the central data base which made it possible for multiple users to upload and retrieve client information in real time. Regarding this virtualization, it became crucial for employees to be careful, thoughtful, and responsible while creating, altering, and filing information (Veldhoen Citation2005, 53–54, 169).

The second part of the design entailed a flexible and open office plan. The workspace of the new office totalled 4000 square metres, which meant a reduction of over 50% compared to the old building; after two years the occupancy rate of the new office space averaged a decent 75%. A design was drawn up by the architects that consisted of two floors, connected by a central staircase, with hardly any internal walls. Walls were made of glass to further transparency (). There were no dedicated offices any more, not even for senior management.

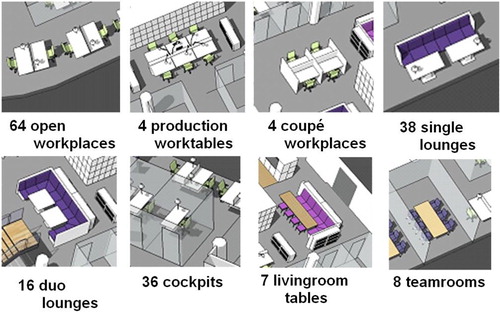

The ground plan was organized in eight so-called ‘orientation zones,’ based on specific client-groups and market niches. Each of these orientation zones was differentiated and facilitated by a workplace mix of eight types of workplace, including open workplaces (64), production worktables (4), duo worktables (4), single lounges (38), duo lounges (16), cockpits (36), living room tables (7), and team rooms (8). In addition, there were conference rooms (2) with removable walls (). Employees had to choose between these options and pick an appropriate workplace for the activity at hand, ideally changing their workplace with each change of activity. The logic of choice for this workplace mix roughly follows the time one would like to spend on a work spot, the level of virtual or physical interaction required, and the level of individual or collective work involved (Duffy Citation1997; Veldhoen Citation2005).

The third part of the design concerned the training of employees to deal with the new conditions for virtual and flexible working. Since employees would no longer be judged on their actual presence in the office, the monitoring of performance became dependent on a procedure of output measurement based on balanced scorecards, a management technique also instrumental for aligning organizational strategy and structure (Kaplan and Norton Citation2006). The V&C consultants regarded the mental changes as the most difficult part, because it involved significant changes in the routines, responsibilities, and attitudes of employees.

The mental project group was dominated by HR employees, and was responsible for communication, commitment and formulating the office rules and performance instruments. We identified about a dozen basic rules of conduct regarding the clean-desk policy, flexible working, activity-based working, working at home, digitalization, paperless working, output measurement, mobile phones, conference calls, information sharing, and cooperation. The consultants regarded deviating from these working rules as resistance to NWW. In their accounts of ‘resistance’, the consultants echoed the typical forms listed by Veldhoen:

1) arguing that there are too few workplaces available, as a reason for refusing to clean a workplace when leaving; 2) coming to the office early in order to obtain a […] particular workplace; 3) not using and updating the e-agenda; 4) claiming the same work spot every day; 5) dragging a lot of stuff to a workplace; 6) long starting and closing hours; 7) searching for explanations and solutions outside one’s own scope of behaviour. (Citation2005, 201)

As may become evident from this account, this conceived space does not stand apart from but anticipates and incorporates projections of the perceived and lived spaces. In fact, the designers and managers actively sought to influence these perspectives to some extent through involving users, through trainings and through (dis-)qualifying certain responses.

It should be clear that the conceived space over all contributes to NWW with a (re)scripting and (re)facilitating of the organization. However, NWW did not completely end the conventional, physical, and sedentary ways of working. The implementation rather started a transitional phase characterized by a hybrid way of working in which digital and physical modes of working interacted. This hybrid feature of NWW was developed in a differentiated network of organizational actors who gradually enrolled in this change process, notably the Beware managers, the V&C consultants, and the project groups. They all translated or ‘concretized’ the abstract ideas of V&C into the Beware context and sought to align work practices with it. In these processes, the various actors related their understanding of NWW to their specific organizational practice – i.e. their position, activities, and identity within the company. The resultant, a specific organizational form can thus be understood as a ‘concrete abstraction’, or a mode of production. The prescriptions and constraints facilitating the hybrid work settings enabled various combinations and levels of virtual and individual (or physical and collective) activities (Duffy Citation1997; Veldhoen Citation2005). Consequently, NWW are not a one-dimensional phenomenon, but rather constitute a plural and differentiated range of NWW, of which some are more physically and others more virtually defined. Also, while some organizations adopting NWW will aim at facilitating individualized work, others will perhaps be more inclined to focus on stimulating interaction and collaboration (Kingma Citation2016). Indeed, as suggested by Boell, Cecez-Kecmanovic, and Campbell (Citation2016), the nature of work should be regarded as an important mediator for the actual use and organizational significance of for instance telework options. But whatever the specific outcome, the causes are in the code of the virtual order which is designed to open up and stretch workspaces, be it not in a complete or definitive way.

5. Perceived space: implications of NWW

This section discusses the spatial routines of NWW practised by the users of Beware’s office space. This addresses Lefebvre’s perceived space and concerns the spatial practices ‘typical of each social formation’ (Lefebvre [Citation1974] 1991, 33, 38). These practices involve particular levels of ‘competence’ and ‘performance’. In exploring the routine user practices – both by observing them and by discussing the patterns in the interviews – it was seen that the changes contributed in two ways to the flexibilization of work practices.

Firstly, the introduction of NWW involved a dissociation from the conventional Beware practices regarding office-based, nine-to-five, department, and leader-focussed work routines. NWW were thus experienced as something different. Secondly, NWW involved an association with digital working, mediated by a centralized database and reliant on self-management techniques with balanced scorecards. Without a fixed workplace, the employees actually found a way (their way) in the new workspace. To a significant extent, although not smoothly and completely, the virtual work practices were gradually adopted together with the new workspaces. The analysis of the perceived space addresses the ordinary, but not unimportant, aspects of spatiotemporal practices, and particularly focuses on (the disruption of) routines, impulsive reflexes, and (un)intended consequences of NWW. Revealing the meaning of ordinary and trivial aspects of everyday (work)life constitutes an integral part of Lefebvre’s approach (Shields Citation1999, 69–71).

The accounts in the first research phase in 2007 covered the primary responses and therefore mainly addressed the perceived space rather than the lived space, which assumes a more experienced understanding of NWW.

Positive and negative responses

The initial responses of the employees can be roughly divided into two categories, being positive and negative appreciations of NWW. In addition, some employees clearly had mixed feelings. Positive responses were most prominent among employees who were already used to a flexible way of working. This group included relatively young employees who mostly were hired after the 2003 wave of layoffs. This typical positive response is from a damage-claim-dealer (employed since 2004):

I think it’s great that the company is actually doing this. The organisation will get a better image, and we will be world leaders compared to other company offices. And it is, of course, great that we will be able to decide more by ourselves how we would like to work. (Rene, May 2007)

However, contrary to our expectations – given the magnitude of the changes – we did not encounter employees with a great unwillingness to adopt NWW. Employees with such attitudes were either not present or they had already left the company. In fact, Beware’s management estimated that over 50 employees (one in eight) actually left the company for reasons related to the relocation and introduction of NWW. This substantial number indicates that NWW certainly did not appeal to all employees.

The impact of the move

The first impacts of the move and NWW were immediately visible and tangible. The digitalization and cleaning of desks had strict deadlines. This success was heralded in a memo: ‘Our company – Empty closets, clean desks … Thanks a lot for your effort in the cleaning trajectory, the first step towards the digital age!’ Even among employees with initial scepticism, such as accountant Sybil (employed since 1992), some optimism emerged:

Well, I was rather sceptical, but I always have an expectant attitude. At the moment, I live nearby, but for the new office I will have to go to work by train; also the company wasn’t performing well, and then we started spending so much money on a new office, why? But, in fact, after the guided tour, we look at this other company [Interpolis] with a comparable office space, I have to say: It looks really nice and tight; we are rather outdated here, of course! So, I will give it a chance … . (Sybil, July 2007)

In the first weeks after the move some serious challenges emerged regarding a range of NWW aspects. Some employees clearly found it difficult to work without a personal desk, without paper files, or they found it hard to trust and use the digital database. The open office plan meant that most employees experienced an increase in noise, interruptions, and distractions, which is a more generally reported and obvious side effect of open-plan offices (Bosch-Sijtsema, Ruhomäki, and Vartiainen Citation2010; Baldry and Barnes Citation2012; Uolamo and Ropo Citation2015).

Flexibilization

The cockpits – shielded work spots for individual work () – are intended for concentrated work. Some workers hardly used the cockpit because they preferred to do concentrated work at home. Cockpits were also popular for making (conference) calls. Team rooms were used for meetings with colleagues, clients, and visitors. And N-joy, the cafeteria, served as a central meeting place, in line with the key role assigned to the restaurant in V&C’s conception, as described in the theoretical section.

Activity-based working implies that workers carefully and repeatedly (re)select their workplace dependent on the activity at hand. However, the choice of workplaces was clearly not only related to the activity but was equally a matter of taste and personal preference. Some interviewees had outspoken preferences for the comfortable single or dual ‘lounge spots’. Others preferred the cockpit or the ‘coupé’ () because they wanted to minimize distractions. In the everyday work practices, employees did not switch often between the eight types of work spot and mainly made use of only one or two different places.

Flexibility also involved working at home. Most employees worked from home at least one day a week. After the move, none of the interviewees worked on a nine to five basis anymore. Next to working flexibly within the office and between the office and the home, they also worked flexibly with regard to the hours in the day (i.e. some also worked from home in the evening or at night), the number of hours a day (i.e. more or fewer than eight hours a day), and the days themselves (i.e. some also worked at weekends).

The tuning of work activities to the various workspaces was enabled by the stark separation between the content of the work and the shape of the workspace. This separation was affected by the use of digital technologies, which largely contain the actual work activities. These technologies to a considerable extent ‘decorporealize’ the new work practices (Brown and O'Hara Citation2003, 1583–1585), which are mediated by electronic connections rather than physical presence. This virtual work may involve emailing and chatting, telephoning, videoconferencing, (making) appointments, (arranging) meetings, (re)searching (on the internet), searching for prospects, administrative tasks, using and updating the central database, data analysis, preparing presentations, and writing documents.

Coercion

The implementation of NWW at Beware was actually a top-down process. Management insisted that the employees really had no alternative. An HRM manager explained that:

… employees who after several months still can’t find their way in the new office perhaps do not match with the company as we would like to see it, and they should perhaps better leave and work somewhere else. (Fieldnote, February 2010)

As stressed by Lefebvre, the three experiential realms of spatial production are ‘never neither simple nor stable’, and only ‘constitute a coherent whole’ under ‘favourable conditions’ (Lefebvre [Citation1974] 1991, 40). The coercion to make NWW actually cohere was experienced in several ways. Some employees seriously felt the loss of the old familiar building, felt estranged, and could hardly get used to the bright and transparent workspace. Furthermore, next to problems caused by the attachment to paper files, some had difficulty with the lack of opportunity to settle on a personalized workplace. Some also felt social insecurity related to hot-desking, because of a decreased predictability of physical closeness of colleagues, as well as the permanent visibility to all. Some expressed the feeling that they were ‘constantly being watched’. Lefebvre’s approach directs attention to such power effects of the conceived space.

So far, this account shows that the changes had a significant and intimate impact on the perceived space of knowledge workers. NWW do not refer to well-defined and recognized work practices the employees are all familiar with. This makes the introduction of NWW of special significance to its users, who together with NWW bring space and technology within their ‘awareness context’ (Glaser and Strauss Citation1964). In the perceived space users of NWW had to dissociate from – unlearn – material work practices and to associate with – learn – virtualized modes of working, which imply a flexible use of workspaces. NWW imply an extension of the ‘workscapes’ (Felstead, Jewson, and Walters Citation2005) of the users with multiple workplaces within and outside the office (telework). NWW not only depend on activities and personal preferences, but also on normative control over workspaces. As we have seen in this case, age and work experience, for instance, count as significant conditions for understanding the primary responses – the discomfort or appreciation – to flexible work spaces. The homogenising force of the designs may open the workspaces and empower the workers, or estrange them and provoke rejections and evasive reactions.

6. Lived space: the appropriation of NWW

While the perceived space in Lefebvre’s theory refers to the way spatialization is experienced in the largely self-evident routines of everyday life, the lived space refers to the way spatialization is experienced in the creative and often critical moments in which we consciously reflect upon space in our spatial imaginations. The lived space of the case study revealed new ‘representational spaces’, as Lefebvre ([Citation1974] 1991, 33, 39) refers to it, regarding spatial reflexivity, flexibility, paper, technology, the open-plan office, homeworking, and corporate culture. The appropriation of these work practices contributed to the predominance of technological interfaces, in two ways.

Firstly, controversies over NWW were largely interpreted as imperfections and exceptions to the ideals of NWW, in which virtual working is distinguished from and prioritized over conventional work modes. Such controversies signalled an increase in spatiotemporal reflexivity regarding space and technology. Secondly, conventional work practices continued to play a part in Beware’s NWW, but only with toned down and reduced standards. For instance, status differences based on position instead of expertise, the use of paper instead of electronics, or spatial settlement instead of mobility continued to be of relevance, but were largely interpreted as being of reduced significance. These reductions paradoxically indicate that NWW cannot do without physical work, which tends to be redefined, disguised, and subordinated to virtual work. Instead of the standard way of working, physical work merely became an option. The lived space thus reveals the meaningful way of working, which may contrast with the conceived space but may also overcome contradictions between conventional routines and the ideals of NWW. Although Lefebvre’s lived space is often associated with struggle and resistance (see for example, Zhang, Hancock, and Spicer Citation2008; Wasserman and Frenkel Citation2011), I would like to stress here that the creative appropriation of new designs in the lived space involves a broader range of equally significant but moderate re-interpretations and modifications. The lived space can also be in harmony with, and a fulfilment of, the conceived space.

Increased reflexivity

The flexibilization of work practices involved a reliance on self-management and an increase in spatial awareness and spatial reflexivity. To some extent, workspace became a constant practical concern, comparable to the mobile workers studied by Brown and O’Hara (Citation2003). Employees were expected to repeatedly change workplaces together with a change in activity, and were expected to hold each other accountable for complying with the NWW rules (although they were mostly reluctant to do so). The clean-desk policy involved one of these rules – i.e. desks should be clean when they are unoccupied or left unattended for more than two hours. Overall, the employees regarded the breaching of rules like this as a matter of sloppiness or inattentiveness.

However, there also were a number of more serious deviations from the NWW rules. In the new Beware office, one client-product team largely ignored the hot-desking policy. This team territorialized its office space, left papers on cabinets after work, and even decorated the wall with posters. Samuel, already employed since 1981 and member of the works council, was one of several employees who were annoyed about this:

There are some teams, and they occupied their own corner. They are really sitting apart, on their own, and that is where you notice that ‘clean-desk’ does not work; it really is not ‘clean’ there. And I think that you should not accept that. But then again, I am not management. (Samuel, May 2010)

The hierarchical differentiation between the first and the second floor of the office space implied a deviation from the NWW ideal of equivalence, as Craig, a sales person (employed since 1998) pointed out:

Yes that [status difference between the first and second floor] is really there’ (… ..) ‘It happens that I hear people talk about the first floor, including people that are always located on the first floor, [talking] about the ‘shop floor’. (…) the people on the second decide on everything, and that does reflect a kind of hierarchy between the floors. (Craig, May 2010)

Another (temporal) anomaly concerned homeworking. Most employees actually worked at home one or two days per week but some turned this option into a right and claimed a fixed day for homeworking, thus effectively making themselves on this day unavailable for office-based activities such as meetings. Paradoxically, this reduced flexibility resulted from the option to work at home.

Extended interfaces

NWW derive meaning from the creative construction of what could be called ‘extended interfaces’ (the meaningful combination of material and virtual elements). In a narrow sense, technological devices such as laptops and smartphones may be characterized as the immediate technological interfaces between the office space and the virtual environment. However, in a broader sense the interface is only effectively constituted by a physical platform in combination with these devices, and it is only in these combinatory acts that the virtual environment is actualized. These acts of combination, by a physical actor, can be referred to in terms of the creation of an extended interface (Kingma Citation2016). This points to the crucial role of the ‘spatial body’ (Lefebvre [Citation1974] 1991, 170, 195) in the everyday (re)production of NWW, because ‘the genesis of a far-away order can be accounted for only on the basis of the order that is nearest to us–namely, the order of the body’ (Lefebvre [Citation1974] 1991, 405).

Frequent concerns regarding Beware’s NWW, as expressed by the interviewees, were practical concerns which affected the extended interface – in particular, annoyances such as talking too loudly on the phone, interruptions by colleagues, ICT breakdowns, and rule breaking regarding the clean-desk policy. Although perhaps minor details, such issues, immediately noticed by the bodily senses, could seriously hinder the work flow and work experience.

Clearly, the new work practices could not solely rely on digital devices. Despite the quest for a paperless office at Beware, in the new office the total volume of paper consumed hardly dropped. Common motives for printing confirm Sellen and Harper’s (Citation2002) analysis of the significance of paper for work practices, included focussed reading, transporting information, filing, marking, and memorizing. However, the relevance of paper for information storage was largely taken over by the digital system. As a consequence of NWW paper was often only used momentarily for certain activities, one of Sellen and Harper’s (Citation2002, 122, 209, 212) major findings. In this respect, the paperless office of Beware could be redefined as an office that kept less paper.

With digital storing, access to the digital archiving system became crucial. This sometimes caused problems with the findability of information, for instance according to this insurance broker (employed since 1998):

… I do really miss the paper file of a client that you could grab out of the cabinet, where you naturally had all the information [in one cabinet and one file]. Now [client information] is spread over so many systems that it’s difficult to get an overview of all the information quickly … . (Donald, May 2010)

Furthermore, technological devices at Beware were not only valued for instrumental reasons. For instance, the standard mobile phone that got issued was a Nokia phone, but employees higher up in the hierarchy were issued Blackberry phones. However, some employees bought a Blackberry phone themselves, to raise the impression of being a high-status employee. Technological interfaces may thus replace traditional status markers such as pens and suitcases.

Continuous virtual presence

The significance of extended interfaces follows from the redefinition of the physical work floor into a platform facilitating a virtual presence. Employees frequently mentioned that they had to deal with an (over)abundance of communication options and the risk of information overload.

Typical of NWW at Beware was the use of conference calls with colleagues who were working at other locations. These conference calls required a specific discipline, related to keeping appointments and taking turns to speak. Conference calls established temporary group connections. Regarding temporal coordination, however, the reliance on mobile phones sometimes created a false sense of availability. Carrying a mobile phone does not mean that one is always able to answer phone calls. This practice reflects a paradox between the closeness and distance associated with the mobile phone, which ‘configures a user who is always available, but not present’ (Arnold Citation2003, 245). Employees adopted various strategies for answering mobile phones. While in the office, some always put their phone on the table and repeatedly checked it. Others kept their phone in their pocket, only answering after it repeatedly rang and asking their interlocutor(s) for permission to take the call. For many, the smartphone became an ambiguous device that reinforced the norm of a permanent presence in the virtual workspace.

Related to this was the expectation that employees should regularly check their email, including at evenings, weekends, and on holidays. The standard at Beware regarding emails was that one should answer quickly and timely. Irma (May 2010) for instance confirmed that she ‘always answers [email] swiftly’, but immediately added that she also had a mixed answering strategy. Sometimes she postponed dealing with emails because they might disrupt her work. Interestingly, some of the interviewees mentioned that the (over)abundance of email was partly related to a need to make decisions traceable, real, and irrefutable, and that these emails thus represented a need for shared responsibility. This ‘confirmation by email’ could turn co-workers into accomplices in a decision. An almost immediate response to email appeared to be the rule rather than the exception at Beware, a finding consistent with more extensive research on the use of smartphones (Mazmanian, Orlikowski, and Yates Citation2013). This behaviour becomes understandable in view of the need for virtual presence in the context of NWW.

Monitoring the productivity of employees became a serious management concern, as one of the managers explained: ‘ … on the one hand it is trust, but on the other hand you simply have to check on people and their work. So, how do I know whether you, in case you are working at home today, generate enough output?’ (Oliver, May 2010). For the managers, employees became increasingly virtualized. The inverse of this was, of course, that for employees, the managers became equally virtualized. Therefore, the focus on output generated feelings of insecurity for employees with regard to the use of balanced scorecards, as indicated by this IT worker (employed since 1996):

Well, it generates insecurity [filling out the balanced scorecard in hindsight]. And then you can really badly get the feeling like: ‘well, my manager likes me so I will have a good evaluation.’ (…) if you fill it in afterwards [which is frequent practice], you can fill it in any way you like … . (Ferdinand, May 2010)

Reduced social cohesion

With reference to the strong social cohesion of the past, some older employees characterized the renewed organization as more individualized, detached, and financially driven. A senior manager (employed since 1993) commented:

[the corporate culture] is detached, clinical. We are an American company now, the emphasis is on numbers. Personally, I miss the warmth in the organization; ‘to feel a sense of community’ the ‘we Beware feeling’ that is not present any more. At our department it is sort of okay, but it is very individualistic, and that is not good. That is deadly for an organization … Yes! That is something we really have to work on. (Percy, May 2010)

This analysis of the lived space shows that NWW require a creative appropriation of spaces and technologies by the knowledge workers, who negotiate over exceptions to the ideals and reduce (but not discard) conventional practices. Crucial to the constitution of NWW is the construction of extended interfaces. The workers creatively combine material elements from the perceived space with virtual elements from the conceived space in order to effectively work online. In the critical and creative moments of putting the two together, employees set new standards in which they make distinctions between offline and online work, and where and with whom to perform the various work activities (at the office, at home, or on the move). In this way, NWW enable continuity of work relations across a range of workplaces and enable the almost permanent presence of users in the virtual work environment. This evokes a new and critical spatial awareness and practical reflexivity regarding time and space. By addressing, in the lived space, exceptions to appropriate behaviour and reducing conventional work routines, users explore and define the symbolical order of NWW. In this respect, Lefebvre’s dialectic reveals a paradoxical relationship between NWW and work relations. While the spatialization of work in NWW enables the continuity of work, this environment at the same time may reduce commitment to, and the social cohesion of, the organization.

7. Conclusion

This article explored the constitution of new organizational designs for spatiotemporal flexible work practices, advocated under the heading of NWW. NWW rely on electronic networks to maintain work relationships. However, one could also reason the other way round – namely, that the emergence of digital network infrastructures enables the flexibilization of work practices (Castells Citation1996). This implies that flexible workspaces and technologies constitute one another in a dialectical way, and that NWW should be understood as the outcome of a historical interaction process between these two realms. However, this interaction can hardly be understood without the mediating role of cultural changes in the lived space of (knowledge) workers.

The organizational design of NWW – in Lefebvre’s terms the ‘abstract space’ – was in this article grounded on the ideas and innovative projects of V&C (Derix Citation2003; Veldhoen Citation2005). This business concept was theoretically defined and analysed with reference to Lefebvre’s spatial triad regarding the perceived, conceived, and lived space. These spatial perspectives always operate together, although the relative importance is context-dependent and may vary over time (Shields Citation1999, 167). This also means that actual coherence is an empirical rather than a theoretical issue. In this respect, the V&C understanding of NWW as well as the case study at Beware overexpose the successful and unproblematic, coherent side of NWW. This, of course, can be attributed to the selection of successful business cases and the absence in the fieldwork of those who seriously objected to NWW at Beware and for this reason left the company. It is the instrumental integration of three organizational dimensions – spatial, technological, cultural – in NWW designs which make this case particularly interesting. It shows how the spatial and the technological are organizationally wrought together and constitute a new meaningful ensemble which may be regarded typical of contemporary work practices.

My analysis was directed at specifying the disparate contributions of, and the interactions between, Lefebvre’s spatial triad as summarized in the analytical framework of . This table starts on the left with Lefebvre’s three ways of knowing space. These epistemological perspectives are specified in three dimensions for defining NWW, which concern the spatiotemporal flexibilization of work practices, the virtualization of the technologically pre-defined organization, and interfacialization as the active connection between spatial practice and the virtual environment. Interfacialization is an appropriate term here because, as we have seen, the lived space of NWW is dominated by the use of technological interfaces by means of which users actively give meaning to NWW – following their particularistic understandings of the conceived and the perceived space. From left to right in , we gradually move to the concrete account of NWW, as derived from the case study.

Table 3. The Lefebvrian conceptualization of NWW.

NWW as conceived by V&C were in this article understood as contributing to a new kind of abstract organizational space. Lefebvre ([Citation1974] 1991, 49–53) associates abstract space with ‘positive’ knowledge, capital accumulation, and the dominance of the conceived over social space. This dominance is the core of his critical approach. The emergence of the abstract space of NWW in the 1990s from a historical perspective involved continuity as well as change. There seem to be overall historical continuities in the workspace rationale of NWW, which aims at increased efficiency and productivity in the deployment of workspace, similar to the previous modern workspace and office innovations such as open-plan offices (Duffy Citation1997; Fleming and Spicer Citation2004). There also seems to be continuity in the tendency towards an increasing empowerment of workers. NWW tend to make knowledge workers responsible for their work processes and productivity. In this sense, NWW reflect a paradox in which freedom and flexibility for employees are accompanied by new demands for (self-)management and (self-)discipline. It could therefore be argued, in line with Hancock and Spicer (Citation2011, 92), that NWW contribute to the fostering of ‘new model workers’ who negotiate ‘the flexible and collaborative forms of group work demanded by the new economy’. NWW favour and rely on such workers who repetitively, and in close harmony, have to bring space and technology together in their everyday work practices.

Acknowledgements

The fieldwork for this research was largely carried out by two MA-students Organization Sciences at VU-Amsterdam, Karin Bosman (first phase in 2007), and Naomi van Dam (second phase in 2010). Previous versions of this paper were presented at EGOS in Barcelona in July 2009, and the Organization Studies Workshop at Rhodes in June 2012. Many thanks to Karin, Naomi, the participants to the workshops, and to the anonymous reviewers of C&O.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Akrich, M. 1992. “The De-scription of Technical Objects.” In Shaping Technology/Building Society, edited by W. E. Bijker and T. Pinch, 205–224. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Arnold, M. 2003. “On the Phenomenology of Technology: The “Janus-faces” of Mobile Phones.” Information and Organization 13: 231–256. doi: 10.1016/S1471-7727(03)00013-7

- Baane, Ruurd, Patrick Houtkamp, and Marcel Knotter. 2011. Het nieuwe werken ontrafeld. Over Bricks, Bytes & Behavior. Assen: Van Gorcum.

- Baldry, Chris, and Alison Barnes. 2012. “The Open-plan Academy: Space, Control and the Undermining of Professional Identity.” Work, Employment and Society 26 (2): 228–245. doi: 10.1177/0950017011432917

- Bernard, H. R. 2002. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. New York: AltaMira.

- Beyes, Timon, and Chris Steyaert. 2012. “Spacing Organization: Non-representational Theory and Performing Organizational Space.” Organization 19 (1): 45–61. doi: 10.1177/1350508411401946

- Bijl, Dik. 2007. Het nieuwe werken. Op weg naar een productieve kenniseconomie. Den Haag: ICT-bibliotheek.

- Blok, Merle M., Liesbeth Groenesteijn, Roos Schelvis, and Peter Vink. 2012. “New Ways of Working: Does Flexibility in Time and Location of Work Change Work Behavior and Affect Business Outcomes?” Work 41: 2605–2610.

- Boell, Sebastian K., Dubravka Cecez-Kecmanovic, and John Campbell. 2016. “Telework Paradoxes and Practices: The Importance of the Nature of Work.” New Technology, Work and Employment 31 (2): 114–131. doi: 10.1111/ntwe.12063

- Boersma, Kees, and Sytze Kingma. 2005. “From Means to Ends: The Transformation of ERP in a Manufacturing Company.” The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 14 (2): 197–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jsis.2005.04.003

- Bosch-Sijtsema, Petra M., Virpi Ruhomäki, and Matti Vartiainen. 2010. “Multi-location Knowledge Workers in the Office: Navigation, Disturbances and Effectiveness.” New Technology, Work and Employment 25 (3): 183–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-005X.2010.00247.x

- Brown, Barry, and Kenton O'Hara. 2003. “Place as a Practical Concern of Mobile Workers.” Environment and Planning A 35: 1565–1587. doi: 10.1068/a34231

- Brunia, S., I. de Been, and T. J. M. van der Voordt. 2016. “Accommodating New Ways of Working: Lessons from Best Practices and Worst Cases.” Journal of Corporate Real Estate 18 (1): 30–47. doi: 10.1108/JCRE-10-2015-0028

- Castells, Manuel. 1996. The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Vol. 1. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd. Original edition. Reprint, 2000.

- Castells, M. 2001. The Internet Galaxy. Reflexions on the Internet, Business and Society. New York: Oxford Univeristy Press.

- Chen, Leida, and Ravi Nath. 2005. “Nomadic Culture: Cultural Support for Working Anytime, Anywhere.” Information Systems Management 22 (4): 56–64. doi: 10.1201/1078.10580530/45520.22.4.20050901/90030.6

- Cooper, Cecily D., and Nancy B. Kurland. 2002. “Telecommuting, Professional Isolation, and Employee Development in Public and Private Organizations.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 23 (4): 511–532. doi: 10.1002/job.145

- Dale, Karen, and Gibson Burrell. 2008. The Spaces of Organisation & the Organisation of Space. Power, Identity & Materiality at Work. New York: Palgrave.

- de Leede, J., and J. Kraijenbrink. 2014. “The Mediating Role of Trust and Social Cohesion in the Effects of New Ways of Working: A Dutch Case Study.” Human Resource Management, Social Innovation and Technology 14: 3–20. doi: 10.1108/S1877-636120140000014006

- Derix, Govert. 2003. Interpolis. Een revolutie in twee bedrijven [Interpolis. A Revolution in Two Companies]. Tilburg: Interpolis, Veldhoen+Company.

- Duffy, F. 1997. The New Office. London: Conran Octopus Limited.

- Duffy, F. 2000. “Design and Facilities Management in a Time of Change.” Facilities 18 (10/11/12): 371–375. doi: 10.1108/02632770010349592

- Elden, Stuart. 2004. Understanding Henri Lefebvre - Theory and the Possible. London: Continuum.

- Felstead, A, N. Jewson, and S. Walters. 2005. Changing Places of Work. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Fleming, Peter, and Andre Spicer. 2004. “‘You Can Checkout Anytime, But You Can Never Leave’: Spatial Boundaries in a High Commitment Organization.” Human Relations 57 (1): 75–94. doi: 10.1177/0018726704042715

- Flyvbjerg, Bent. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings about Case-study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–245. doi: 10.1177/1077800405284363

- Glaser, B. G, and A. L. Strauss. 1964. “Awareness Contexts and Social Interaction.” American Sociological Review 29: 669–679. doi: 10.2307/2091417

- Goonewardena, Kanishka, Stefan Kipfer, Richard Milgrom, and Christian Schmid. 2008. Space, Difference, Everyday Life. Reading Henri Lefebvre. New York: Routledge.

- Gorgievski, Marjan J., T. J. M. van der Voordt, Sanne G. A. van Herpen, and Sophie van Akkeren. 2010. “After the Fire. New Ways of Working in an Academic Setting.” Facilities 28 (3/4): 206–224. doi: 10.1108/02632771011023159

- Hancock, P. H., and Andre Spicer. 2011. “Academic Architecture and the Constitution of the New Model Worker.” Culture and Organization 17 (2): 91–105. doi: 10.1080/14759551.2011.544885

- Harrison, Andrew, Paul Wheeler, and Carolyn Whitehead. 2004. The Distributed Workplace. London: Spon Press.

- Hirst, Alison. 2011. “Settlers, Vagrants and Mutual Indifference: Unintended Consequences of Hot-Desking.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 24 (6): 767–788. doi: 10.1108/09534811111175742

- Hislop, Donald, and Caroline Axtell. 2009. “To Infinity and Beyond?: Workspace and the Multi-location Worker.” New Technology, Work and Employment 24 (1): 60–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-005X.2008.00218.x

- Hoendervanger, J. G., I. de Been, W. N. van Yperen, M. P. Mobach, and C. J. Albers. 2016. “Flexibility in Use. Switching Behaviour and Satisfaction in Activity-Based Work Environments.” Journal of Corporate Real Estate 18 (1): 48–62. doi: 10.1108/JCRE-10-2015-0033

- Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. 2006. “How to Implement a New Strategy Without Disrupting Your Organization.” Harvard Business Review 84, March: 100–109.

- Kingma, Sytze F. 2008. “Dutch Casino Space or the Spatial Organization of Entertainment.” Culture and Organization 14 (1): 31–48. doi: 10.1080/14759550701863324

- Kingma, Sytze F. 2016. “The Constitution of ‘Third Workspaces’ in Between the Home and the Corporate Office.” New Technology, Work and Employment 31 (2): 176–193. doi: 10.1111/ntwe.12068

- Kornberger, Martin, and Stuwart Clegg. 2004. “Bringing Space Back in: Organizing the Generative Building.” Organization Studies 25 (7): 1095–1114. doi: 10.1177/0170840604046312

- Lefebvre, H. (1974) 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lefebvre, H. (1982) 2003. “Twelve Theses on Logic and Dialectic.” In Henri Lefebvre. Key Writings, edited by Stuart Elden, Elizabeth Lebas, and Eleonore Kofman, 63–68. London: Bloomsbury.

- Leonardi, Paul M., and Stephen R. Barley. 2008. “Materiality and Change: Challenges to Building Better Theory about Technology and Organizing.” Information and Organization 18: 159–176. doi: 10.1016/j.infoandorg.2008.03.001

- Mazmanian, M., W. J. Orlikowski, and J. Yates. 2013. “The Autonomy Paradox: The Implications of Mobile Email Devices for Knowledge Professionals.” Organisation Science 24 (5): 1337–1357. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1120.0806

- Meyer, J. W., and P. Bromley. 2013. “The Worldwide Expansion of ‘Organization’.” Sociological Theory 31 (4): 366–389. doi: 10.1177/0735275113513264

- Mitchell, W. J. 2000. E-topia. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Neyland, Daniel. 2008. Organizational Ethnography. London: Sage.

- Orlikowski, W. J. 2000. “Using Technology and Constituting Structures: A Practice Lens for Studying Technology in Organizations.” Organization Science 11 (4): 404–428. doi: 10.1287/orsc.11.4.404.14600

- Orlikowski, Wanda J., and Susan V. Scott. 2008. “Sociomateriality: Challenging the Separation of Technology, Work and Organization.” The Academy of Management Annals 2 (1): 433–474. doi: 10.1080/19416520802211644

- Peltonen, Tuomo. 2011. “Multiple Architectures and the Production of Organizational Space in a Finnish University.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 24 (6): 806–821. doi: 10.1108/09534811111175760

- Peters, Pascale, and Stefan Heusinkveld. 2010. “Institutional Explanations for Managers’ Attitudes Towards Telehomeworking.” Human Relations 63 (1): 107–135. doi: 10.1177/0018726709336025

- Ritchie, J., and J. Lewis. 2003. Qualitative Research Practice. A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Sellen, A., and R. Harper. 2002. The Myth of the Paperless Office. Cambridge: MIT press.

- Senge, P., A. Kleiner, C. Roberts, R. Ross, G. Roth, and B. Smith. 1999. The Dance of Change: The Challenges of Sustaining Momentum in Learning Organizations. New York: Doubleday/Currency.