Abstract

Exhibition display has a considerable impact on the public’s understanding of and respect for textiles. This article revisits 13 exhibitions held between 2005 and 2018, many of which I have previously written about in exhibition reviews, that offer innovative and thoughtful installation solutions. The examples I have selected for discussion include both textile design and textile art – genres that share a common material but pose specific exhibition challenges. Rather than focus on curation, this article attends to the seemingly pedestrian decisions of exhibition installation. Examples are organized into three groups: bolts of cloth considers the display of lengths and samples predominantly of printed textiles; the bed and the wall focuses on pieced textiles displayed on these two distinct surfaces; the final group of examples gathers together works where integrated installation solutions are solved, and often even named, as aspects of the artwork. My intention in gathering together these admittedly eclectic examples is to inspire greater consideration of the impact display decisions have on the public’s appreciation and respect for textiles.

Textiles exhibited within the context of the art gallery are perhaps most notorious for their misbehavior. Twisting and drifting away from the clean straight lines of contemporary interiors, textiles often read as floppy. Historically, the overriding premise that guides the visitor’s experience within the white cube of an art gallery is a desire to designate the space as “elevated” beyond the “distractions” of the everyday. But art galleries are particularly ill-suited to conveying some of most powerful values of cloth. Touch is not usually allowed and handling samples often look and feel like dingy hankies by the end of an exhibition. In this context the domestic and functional associations of cloth find some of their most acute discomfort.

The art gallery and museum, while unquestionably conventional settings, are inescapably influential places where the public meet and appreciate textiles. This article seeks to address some physical realities of textile exhibition strategies in the gallery and museum by means of examples. The earliest version of these ideas was presented at the Textile Thinking Symposium held in conjunction with the Hangzhou Triennial of Fiber Art, China in September of 2016 and with textile students at the Royal College of Art, London in November of the same year.

Over the past decades the textile has claimed space within the theoretical discourse of relational esthetics – reminding audiences that the relationship between cloth and community has long been robust, albeit not always diverse. Thomas McEvilley (Citation1986), writing a new introduction to Brian O’Doherty’s Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, opens the book by acknowledging, “It has been the special genius of our century to investigate things in relation to their context, to come to see the context as formative on the thing, and, finally, to see the context as a thing itself” (McEvilley Citation1986, 7). An increasing emphasis on the potential for the textile to communicate in spaces outside the gallery has emerged: yarn bombing local parks and other, often fixed, objects within our civic spaces. Some (but far from all) of these textile incursions are useful and deserve to continue at the pace with which they have grown in recent years.

But in this article I want to refer to examples of exhibitions that have taken place within the conventions of the art gallery, drawn from two arguably different genres with a shared material source: textile design and textile art. Textile design poses particular exhibition challenges, as the textile – often in the hands of another designer – will go on to find its final form. Textile art arguably should not face this problem, as the final work comprises the artist’s process. That said, it is remarkable how often installation solutions for textile art involve strands of monofilament we pretend are invisible, despite glistening conspiratorially in directed spotlights, tugging and tearing at the edges of heavier textiles. While thoughtful installation solutions for textiles do exist, they are few and far between.

The examples I have selected for discussion here are exhibitions I have had the opportunity to see in person. There are, of course, countless others. Many of the exhibitions I have selected for discussion did not enjoy a large viewing audience. I defend this approach with a warning that what we do not experience in person represents only a sliver of the exhibition experience. To write without having stood within the gallery space presents a danger I cannot risk. Rather than claim to be more comprehensive than is honest, I will claim instead the crucial importance of first-hand experience of viewing the exhibition. While these examples are unquestionably the product of my personal opinion alone, they represent a fraction of the exhibitions I have reviewed (10% to be exact). I offer in defense of reliance on personal opinion my experience of the numerous exhibitions from which I have sifted and selected the following examples. My objective is to gather, and in most cases commend, this inspiration. It is long overdue that we think with greater intention about the powerful impact display decisions have on the public’s understanding and respect for textiles.

But first, two memories. In the winter of 2006 I traveled to Belgium to review the exhibition Dream Shop: Yohji Yamamoto at Mode Museum in Antwerp (March 7 – August 13, 2006) (Hemmings Citation2006). The unusual premise of this exhibition was that visitors were allowed to try on a selection of the garments on display – an invitation to experience and be in rather than peer at the clothing. But I was alone and the sky was trying to snow. I selected a coat, comforted in the knowledge that I would not need to shed a single layer of warm clothing before trying on an extra one. I found a gallery attendant, pointed to my choice, and, as she stood behind me holding the garment, I dutifully stiffened one arm, the cuffs of my sweater tugged tightly into the palms of my cold hands. It was only when I found no sleeve for my arm to enter that I learnt the coat was a cape – not only a cape, but a cape with a place to hook my hands tightly tucked under my chin to draw the garment close around me. This lesson has haunted me – how many photographs have I misread?

Two years earlier, in 2004, I made the long journey to western Australia for a textile conference called “The Space Between.” To coincide with the conference was the retrospective exhibition Spheres and Kuma Guna: Maria Blaisse held at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (March 31 – May 9, 2004) (Hemmings Citation2005a). The exhibition invited viewers to handle the objects on display. I recall, in particular, shapes made from knitted fabric and rubber inspired by the inner tube of a bicycle tire the Dutch artist had initially needed to fashion into a fireman’s hat at short notice for a child’s party. I “interacted” with some trepidation, only to realize I had become a performer for an audience of one: the equally nervous museum guard. (Nervous museum guards are a relatively common occurrence. When visiting the Art Institute of Chicago to review Fashioning the Object: Bless, Boudicca, and Sandra Backlund (April 14 – September 13, 2012) (Hemmings Citation2012) I was told that I could not take notes. At the Royal Museum of Ontario in Toronto (June 2 – October 8, 2018) I watched a museum guard tell a visitor to stop interacting with the architect Philip Beesley’s interactive installation (Hemmings Citation2019). Reviewing Blaisse’s exhibition, I observed, “I do not think that I am the only person to concede that I have long lost a part of myself that Blaisse has kept alive. It is the ability to explore concepts and materials without intellectualizing and explaining: the ability to allow time for play” (Hemmings Citation2005a, 50).

I recount these two experiences to help explain my interest in textile exhibition strategies. Over the past two decades the genre of the exhibition review has remained a constant personal interest. It is a research “outcome” that does not count in the machine of academic bibliometrics – a “nul point” entry in our ever more pressured academic environments of knowledge production. Practically, it is an unwise genre for an academic to even claim as a professional commitment. I’ve ignored these facts because I enjoy writing exhibition reviews. I see the importance that the exhibition, and the critical discourse that exhibition reviews can contribute, as a crucial contribution to the health of textile scholarship. Alexandra Palmer (Citation2008), exhibition reviews editor of the journal Fashion Theory, acknowledges, “At times curators have described their exhibition installations, methods and intentions […] Though this is a valid contribution to the field, these do not serve as reviews because they do not record the visitor experience” (Palmer Citation2008, 122). It is precisely this reflection from my perspective as the visitor with first-hand experience of the physical exhibition – admittedly a visitor tasked with writing a review – but not a curator or museum administrator, that I draw on here.

Bolts of Cloth

Unlike fashion curation (which has its own questions about dealing with an absent body), exhibitions of textile design face the challenge of presenting material that exists as a bolt of cloth. Later another designer will turn the cloth into a recognizable product, but until then bolts of cloth often present display conundrums. Our inability to trust that the textile alone is enough to exhibit often results in distracting decisions that try to do something with the cloth.

The exhibition Form through Colour: Josef Albers, Anni Albers and Gary Hume held in the East Wing Galleries of Somerset House, London (June 5 – August 31, 2014) (Hemmings Citation2014) did both. Printed textiles designed by Anni Albers were suspended from the ceiling to hang at varied heights above the floor in a small room where there was just enough space to feel invited to move between the textiles (). The relatively small size of the room forced viewers to experience the subtle patterns of each design from multiple perspectives, while the textiles towards the back of the space were visible to a viewer who made the effort to move through the space. But Form through Colour did not quite hold its nerve in this way throughout. Elsewhere some of the same fabrics were sewn into pillows and displayed tumbling from a fireplace surround (). Beyond the oddity of stuffing textiles up a chimney was the sense that cloth alone could not be trusted to be quite enough.

Figure 1 Installation view of Form through Colour: Josef Albers, Anni Albers and Gary Hume, East Wing Galleries, Somerset House, London (June 5 – August 31, 2014). Image courtesy of Christopher Farr.

Figure 2 Installation view of Form through Colour: Josef Albers, Anni Albers and Gary Hume, East Wing Galleries, Somerset House, London (June 5 – August 31, 2014). Image courtesy of Christopher Farr.

Curated by Lesley Millar, 2121: Reiko Sudo & NUNO at the University of the Creative Arts (June 17 – July 23, 2005) (Hemmings Citation2005b) in Surrey, England exhibited fabrics by the Japanese company NUNO. The exhibition used long lengths of cloth suspended as cylindrical columns (), which solved the question of how to display yardage and invited the viewer into a dynamic relationship with the cloth’s surface. But a quibble with this approach is that the form of the column is perhaps one of the least likely shapes that the cloth will be used in – towering and curved are unlikely applications to have been in the minds of the designers when they created the cloth. The 2121 installation conjured an immersive, theatrical atmosphere but also ran the risk of “dressing up” the cloth through its particular installation.

Figure 3 Installation view of 2121: Reiko Sudo & NUNO, University of the Creative Arts, Farnham, England (June 17 – July 23, 2005). Image courtesy of Lesley Millar.

A decade after 2121 was exhibited in England, Melbourne, Do You NUNO? was held at the Australian Tapestry Workshop (October 6 – November 6, 2015) in conjunction with NUNO Director Reiko Sudo’s Hancock Fellowship. The exhibition showed a large number of small textile samples by piecing together numerous squares roughly organized by color (). Several large pieced cloths were suspended in oval shapes (white in the outer group, black and darker-colored samples in a smaller inner curve) that allowed the viewer to see both sides of the samples. The oval shapes also encouraged active viewing of the textile by requiring the audience to keep moving and shifting their perspective in relation to the work. While the solution lacked the drama of 2121, it efficiently presented a large number of samples and trusted the textile sample to be enough to hold viewers’ attention.

Figure 4 Installation view of Melbourne, Do You NUNO? by Reiko Sudo at the Australian Tapestry Workshop, Melbourne (October 6 – November 6, 2015). Image courtesy of the Australian Tapestry Workshop. Photo credit: John Goldings AM.

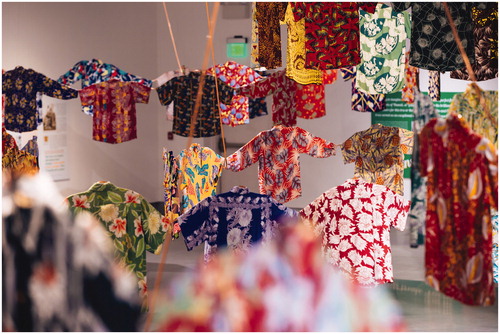

An exhibition of colorful printed Hawaiian shirts called Flurabuna, part of the Fiber exhibitions at the KANEKO Center in Omaha, Nebraska (February 6 – April 25, 2015) (Hemmings Citation2016b), suspended shirts on a curved metal hanging system to create different viewing heights (). In contrast to the previous examples, Flurabuna faced the particular challenge of exhibiting printed textiles already cut and sewn into shirts. Garments are intended for the body. With the body absent the focus may shift, for example, to surfaces containing patterns – or they may just look downright odd. Here the unusual display drew the viewer’s attention to the cloth, rather than the absent body. While this installation also relied on a certain element of theater, which encouraged the shirts to be seen as a cacophony of color and pattern, the installation functioned usefully in what was otherwise a cavernous exhibition space and, unlike Albers’ unfortunate chimney pillows, did not fundamentally distort the objects on display.

Figure 5 Installation view of Flurabuna, KANEKO Center, Omaha, Nebraska (February 6 – April 25, 2015). Image courtesy of the KANEKO Center.

The preceding examples illustrate various ways in which textile design has been creatively exhibited. The final example I shall discuss in this section is the Norwegian artist Toril Johannessen’s Unlearning Optical Illusions project. The project involved four iterations exhibited between 2014 and 2018. In early installations the printed cloth, which Johannessen created to look like wax resist fabric, was displayed as large, framed photographic images. For the Migrations exhibition I curated (2015–17), lengths of cloth were laid on a table and visitors invited to wrap the cloth around themselves. This strategy was spectacularly unsuccessful for a number of reasons. The main one was the confusion created by inviting visitors to touch one element of the exhibition while requesting they did not touch other elements.

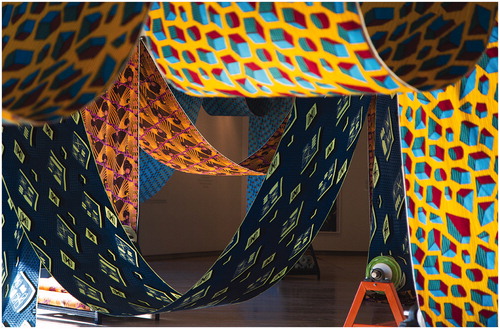

Johannessen’s emphasis on the textile as an object and bolt of cloth was part of her artistic strategy. Unlearning Optical Illusions focused on the routes so-called Dutch wax textiles traveled between the Netherlands, west Africa and present-day Indonesia. This identity allowed Johannessen the freedom to see the bolt of cloth not as a practical inconvenience of textile design, but as an object carrying meaning that she wanted to communicate rather than conceal. In later iterations of Optical Illusions Johannessen worked with a textile printing company in Ghana on a small production run of printed cloth and began to exhibit the cloth as bolts partially unwound in the gallery. The crucial difference in Johannessen’s display compared with the previous exhibitions I have mentioned is the use of full bolts of cloth as a display strategy at the Kabuso Centre in Norway in (October 8 – December 11, 2016) (Hemmings Citation2016a) and ARoS Aarhus Art Gallery in Denmark (June 17 – September 3, 2017). At the Kabuso Centre the lengths of printed cloth draped from floor to ceiling to create a dynamic solution that trusted the beauty of the textile alone to hold the viewers’ attention. ( and )

Figure 6 Installation view of Toril Johannessen: Unlearning Optical Illusions, Kabuso Centre, Norway (October 8 – December 11, 2016)

Johannessen’s later installations of Unlearning Optical Illusions introduced the textile as a dynamic element in the gallery setting. While the 2121 exhibition curved lengths of NUNO fabric into space-efficient but somewhat unlikely columns, Johannessen’s draping of long lengths of cloth allowed the material to billow in the exhibition space and occupy the full volume of the gallery (which at the Kabuso Centre had an unusual split-height ceiling). Touch was not invited, but a slight breeze caused by the opening and closing of the gallery door at the Kabuso Centre sent ripples across the entire installation. (In fact, the length nearest the door looked more fatigued near the exhibition’s closing date – the result of either surreptitious touch or the slight but constant movement.) Reflecting on the Migrations exhibition, which included some of the textiles from the Unlearning Optical Illusions project, the curator and academic Christine Checinska (Citation2016) observed,

I think that there is an accessibility when we work with textiles in a curatorial setting so that people can come in and recognize themselves or begin to recognize their own stories because we are working with cloth. And I think that for me is the power of textiles in these settings. Coming into the Migrations show, one of the first things I noticed – yes, I noticed all the fabulous color – but I also noticed immediately the way that the cloth was moving. There was a slight breeze and I noticed the way the cloth moved, and felt it was almost like a person moving there.

The examples I have discussed in this section share an ability to disrupt the public’s passive relationship with viewing and instead demand active participation in the viewing of the textile. Rather than complicate the exhibition with strategies that distract from the actual textile, many of these installation strategies trusted that the textile alone is enough to draw viewers’ attention to the material, color, and pattern.

The Bed and the Wall

Useful decisions about textile exhibition installation foreground the material qualities of the textile. This means that the qualities of the cloth are not suppressed in the art gallery in deference to tired historical conventions that, for example, frame work under glass so that it conveniently aligns with the dominant architecture of the exhibition space. But this is not to say that the textile has to be floppy to be honest. American artist Anna Von Mertens used the low proportions of beds to display her quilts in Black, White, Shades of Gray: Anna Von Mertens at the Lizabeth Oliveria Gallery, Los Angeles (January 29 – February 26, 2005) (Hemmings Citation2005c). Here Von Mertens did little to deny the associations we make between quilts and the bed. While the platforms she used take on the proportions of the bed, they did not convey associations of comfort ( and ). Underneath these quilts are hard, uninviting surfaces.

Figure 9 Installation view of Black, White, Shades of Gray: Anna Von Mertens, Lizabeth Oliveria Gallery, Los Angeles (January 29 – February 26, 2005). Photo credit Joshua White.

Figure 10 Installation view of Anni Albers (1899–1994) exhibition at the Tate Modern, London (October 11, 2018 – January 27, 2019). Photo credit: ©Tate, London 2018.

Von Mertens stitches and hand dyes her work, investing considerable time and labor in the production of each quilt. Her work has the potential to function in the conventional sense that the quality of the construction, dimensions of the work, and materials she works with can withstand use. But Von Mertens consistently situates her work in gallery contexts. “It is very much the plane that the work lies in that I am investigating as well as the context of the bed […] The horizontal plane surfaces such a different relationship with the viewer: being able to look across something, and able to walk around the work in the space of the everyday” (Von Mertens Citation2018).

Von Mertens’ platforms are distinct from display decisions that literally evoke the domestic, such as the low bed platform included in the Anni Albers exhibition held at the Tate Modern in London (October 11, 2018 – January 27, 2019). Whereas Von Mertens used entirely flat surfaces, The Albers’ display included the suggestion of a pillow or raised place for the sleeper’s head (). “She made bedspreads and textile partitions that were expressly thought of as diversifying a very small space into separate uses for sleep and study, in which beds doubled up as divans to sit on” (Fer Citation2018, 40). This cue is important in the context of an exhibition that usefully brought together textile art and textile design – here making clear the functional design intentions of the bedding design Albers was commissioned to produce for the bedrooms of the Harvard Graduate Center in 1950.

Von Mertens’ installation strategy is in distinct contrast to the group exhibition Losing the Compass (October 8, 2015 – January 9, 2016) curated by Scott Cameron Weaver and Mathieu Paris and shown at the White Cube Mason’s Yard in London. The exhibition “focused on the rich symbolism of textiles and their political, social and aesthetic significance through both art and craft practice” (White Cube Citation2018). Work by Alighiero e Boetti, Mona Hatoum, Sergej Jensen, Mike Kelley, William Morris, Sterling Ruby, Rudolf Stingel, Dan Vō, and Franz West and quilts made by Amish communities and quilters from Gee’s Bend in Alabama were all part of the group show.

Losing the Compass took two acutely distinct approaches to textile installation. Work by the named artists was displayed flat on the gallery walls according to the typical conventions of the gallery setting; quilts made by the Amish communities and Gee’s Bend quilters were displayed so that the composition of the quilts was either disrupted by folding over a series of platform-like steps () or, across the room, concealed by hanging from pegs in the gallery wall (). Was the display intention to make clear the quilt was not trying too hard to claim itself as art? The gesture (much like Anni Albers’ pillows tumbling from the fireplace of Somerset House) suggests that the textile alone is not enough in the literal White Cube.

Figure 11 Losing the Compass, White Cube Mason’s Yard, London (October 8, 2015 – January 9, 2016). Photo courtesy of White Cube (Stuart Burford).

Figure 12 Losing the Compass, White Cube Mason’s Yard, London (October 8, 2015 – January 9, 2016). Photo courtesy of White Cube (Stuart Burford).

Reviewing the exhibition, Janet Tyson (Citation2016) astutely writes,

The numerous quilts shown in the same exhibition are treated very differently. Three hang on the wall from single fastening points, which causes them to drape in pleasingly sculptural folds. This makes for dramatic contrast to the crisp, flat rectilinearity of the two Boettis, but it is also anathema to textiles, bringing all weight to bear on that single point. The rest of the quilts are laid, overlapping, on stepped risers that span one side of the long, narrow room. This arrangement is less stressful to the objects, but it trivializes them by giving them the appearance of goods in a bazaar, rather than artworks in an elite gallery – a diminution starkly emphasized in relation to display of the Boetti works. (https://hyperallergic.com)

Nearly two decades ago, Sarat Maharaj (Citation2001) articulated the complex place the quilt inhabits:

Half-on-wall, half-on-floor, it stands/lies/hangs before us: everyday object and artwork in one go. Domestic commodity, which is at the same time the conceptual device. The quilt stands/lies/hangs before us as a speculative object without transcending the fact that it is a plain, mundane thing. Not entirely either and yet both, and “undecidable”. Sarat Maharaj (Citation2001, 8)

While Maharaj claims the undecidable as a positive quality, Losing the Compass took this description literally to heart. The approach undeniably disrupted our expectations of where and how we see the textile, but felt like a denial of the material qualities of the quilts included in the exhibition.

I raise this critique with reservations, as I too have hung “anonymous” textiles in a well-intentioned flourish against the gallery wall. Ironically, the east African khanga cloth I bought in 2014 and 2016 in Tanzania and included in the Migrations exhibition was displayed at the Huddersfield Gallery of Art () in a manner similar to Scott Cameron Weaver and Mathieu Paris’ strategy in the White Cube. My defense, if I am allowed one, is that hanging relatively light printed cotton in this way is quite different from the thick quilts that Tyson (Citation2016) observes as “bringing all weight to bear on that single point” (https://hyperallergic.com). The khanga cloth happens also to be the textile Christine Checinska (Citation2016) is standing next to when she refers to the evocative value of the movement of cloth in the gallery setting. I too could be accused of treating the anonymous textile differently to the named artist’s works by hanging the lengths of cloth informally and anonymously, if it were not for Johannessen’s textiles which were not displayed as anonymous work but were strewn (with her blessing) across a nearby table. Even more crucial to acknowledge may be the physical difference: light cotton does not tug if draped on a peg in the same way as the weight of a large quilt.

Figure 13 Installation view (detail) of East African khanga cloth in Migrations, Huddersfield Gallery of Art, England (October 22, 2016 – January 21, 2017).

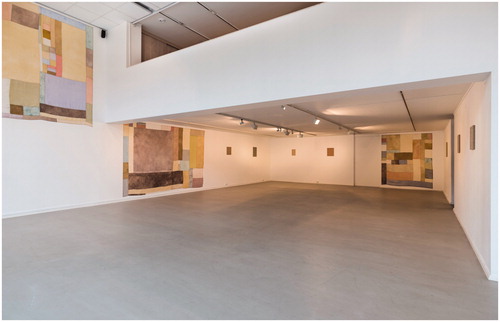

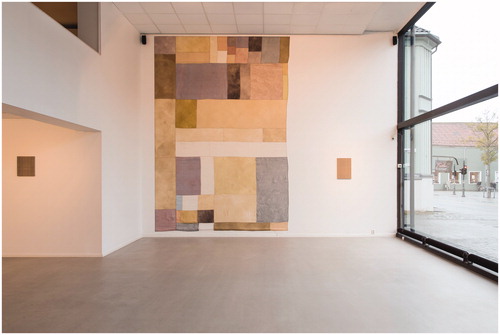

Imposed floppiness, as seen in Losing the Compass, can often look and feel artificial in the gallery setting. Icelandic artist Hildur Bjarnadóttir’s exhibition Cohabitation: Hildur Bjarnadóttir at the Trøndelag Senter for Samtidskunst, Trondheim, Norway (October 26 – November 19, 2017) (Hemmings Citation2018) took yet another approach. Prior to the Cohabitation exhibition, Bjarnadóttir used pieced, dyed silk in the exhibition Contemplated Randomness at Hverfisgallerí, a small gallery space in Reykjavík, Iceland (December 3, 2016 – January 14, 2017). Entire walls of the space were filled from edge to edge with pieced cloth made to measure for the gallery dimensions. In the larger exhibition space available in Trondheim, Bjarnadóttir expanded the dimensions of the work and continued to press the sheer textiles firm against the flat gallery walls, but no longer filled the entire gallery ( and ). Bjarnadóttir explains her “desire to ‘stabilize the silk’ by pressing it into the wall,” but the sheer silk she uses “has things other than straight lines in mind. The two remaining edges of each work reveal the tension and pull on the bias of the cloth that drifts away from a perfect geometry” (Hemmings 2018).

Figure 14 Installation view of Cohabitation: Hildur Bjarnadóttir, Trøndelag Senter for Samtidskunst, Trondheim, Norway (October 26 – November 19, 2017). Photographer: Susann Jamtøy.

Figure 15 Installation view of Cohabitation: Hildur Bjarnadóttir, Trøndelag Senter for Samtidskunst, Trondheim, Norway (October 26 - November 19, 2017). Photographer: Susann Jamtøy.

Bjarnadóttir admits that her MFA education at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York in the late 1990s established painting as her primary and continued reference point. Additional works in the Cohabitation exhibition included small handwoven pieces made from a mixture of natural dyes and acrylic coloring, hung conventionally at eye level with ample white wall space surrounding each. Reflecting on the sheer panels, I wrote in my review, “Placing the textile tightly against the wall is not necessarily a denial of the material (the wobbly edges help remind us of that) but it is a gesture which emphasizes [optical] composition over [physical] object. There remains a certain irony to seeing only one side of work that has been made with three-fold seams to ensure that there is no designated front or back. But holding the textile tight against the gallery walls ensures that the opaque palette of each is visible and relatively constant” (Hemmings 2018). This final example presents a curious tension between meeting the convention of rectilinear installation and, ironically, allowing the textile and, in this case the stretch of the bias, to confound these expectations.

Quilts can carry particular domestic connotations. In the examples I have discussed in this section, these associations are not denied by Anna Von Mertens’ low platforms, but nor are they in any way confused with home furnishings. Anni Albers’ bedding design is usefully confirmed to be functional design (within an exhibition that also includes a large amount of Albers’ textile art) in the Tate exhibition. In contrast, Loosing the Compass also sought to bring together “art and craft” but imposed two entirely different installation strategies, presumably to limit any potential “contamination” between the two. The final example of this section, Hildur Bjarnadóttir’s pieced panels, navigates the art and craft divide entirely differently: the cloth is pressed close to the gallery wall but still allowed the last word. The bias stretch of the material agrees to conform only partially to the architecture of the space. The installation exists on the textile’s terms.

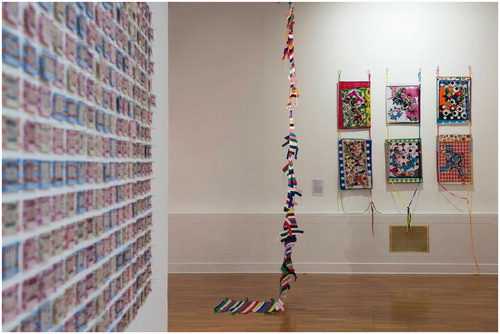

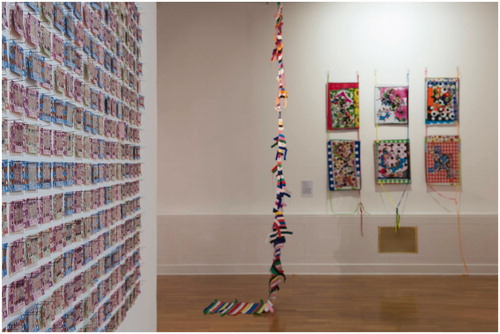

Integrated Installation Solutions

The curator Lucy Day et al. (Citation2018) of Day + Gluckman reflects,

when curating shows involving textiles, or any “floppy”, flexible, sculptural work it is always interesting to see whether artists have worked the “display” element into the work itself. On occasion we are left to work it out ourselves, which gives a lot of (too much?) creative license. There is though something inherently prosaic about going for a very conventional two-dimensional hang, and that’s as much bound up with a perpetuated confusion over textiles’ “place” in the art world I’m sure! Lucy Day et al. (Citation2018, 313)

Questions around installation solutions and who is best positioned to resolve these decisions are central to the examples discussed throughout this article. While a gallery installation team is, in an ideal situation, expert in their knowledge of the space they are working in, they do not necessarily have textile-specific knowledge. Ironically, this challenge has become more common as textiles have found themselves increasingly welcomed into exhibition spaces that work with a range of media, rather than material-specific craft galleries. Artists aware of the many and various challenges of textile installation have resorted to their own installation solutions planned and integrated into their artworks. Some include the means for installation as part of the work, the gallery being instructed to use only the method and materials provided.

For example, the London-based French artist Françoise Dupré includes the hooks she has sourced for hanging her work in the materials list for the artworks, which makes their use in installation not optional for the gallery (Dupré Citation2015) (). British artist Claire Barber’s painstaking installation of You Are the Journey (An Embroidered Intervention) (2015) for the Migrations exhibition at the Huddersfield Gallery of Art, England (October 22, 2016 – January 21, 2017) similarly lists the long pins used to install the needle-woven ferry tickets as one of the materials in the artwork ().

Figure 16 Installation view with background in focus of Migrations, Huddersfield Gallery of Art, England (October 22, 2016 - January 21, 2017). Left: Claire Barber You Are the Journey (An Embroidered Intervention) (2015), used ferry tickets, reclaimed yarn, pins, and needle weaving over used ferry tickets (detail); middle: Françoise Dupré, Stripes, started in 2009 in Mostar, Bosnia-Herzegovina with straps of bags used in OUVRAGE project - 2011 woven webbing, straps from carrier bags and thread, bamboo cane, and hooks; right: Françoise Dupré, Arabesques, Stars with Dragon (2014), wall hanging installation, stitched woven and printed polythene, polyester/cotton bias, thread, quilting pins, acrylic knitted flat braids, and six stainless steel screw rings.

The British artist Lucy Brown suspends and interweaves elements of second-hand clothing in on-site installations. This approach has posed challenges for installation when Brown is not present, for example once an artwork is held in a public collection. When the secrets we keep from ourselves … (2012–15) was acquired by Nottingham’s Textile Art Collection in 2016, Brown composed a 218-page document of installation instructions. The instructions refer to all the installation elements included in the artwork (dressmaking pins, safety pins, light gray and dark gray steel tacks, metal arches, small white and black pegs, metal peg hook) (Brown Citation2016). Brown spent two years working on the installation guidelines, reflecting, “It is a difficult but interesting challenge for me to relate how I install my artwork as the performative installation [which] is very much part of the works’ process and language […] I had to mentally, emotionally and physically detach myself from the work in order to translate the installation process” (Brown Citation2018).

Figure 17 Installation view with foreground in focus of Migrations, Huddersfield Gallery of Art, England (October 22, 2016 - January 21, 2017). Left: Claire Barber You Are the Journey (An Embroidered Intervention) (2015), used ferry tickets, reclaimed yarn, pins, and needle weaving over used ferry tickets (detail); middle: Françoise Dupré, Stripes, started in 2009 in Mostar, Bosnia-Herzegovina with straps of bags used in OUVRAGE project - 2011 woven webbing, straps from carrier bags and thread, bamboo cane, and hooks; right: Françoise Dupré, Arabesques, Stars with Dragon (2014), wall hanging installation, stitched woven and printed polythene, polyester/cotton bias, thread, quilting pins, acrylic knitted flat braids, and six stainless steel screw rings.

The solution Swedish artist Emelie Röndahl built for her large tapestry Rana Plaza – the Collapse (April 24, 2013) involves suspending the weaving from a purpose-built scaffolding (). Admittedly, concessions to the expectations of gallery gravitas are still made: the metal is painted an unobtrusive gray and the textile, while long enough to touch the floor, rests on a clean floor plinth. But the presence of scaffolding contributes to our reading of a work that is about textile labor and the collapse of the textile factory in Bangladesh described as “the deadliest unintended structural failure in modern times” (The Guardian Citation2018), which tragically killed ten times more factory workers than the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in New York City a century earlier (Sherlock Citation2007, 8). Röndahl solves the challenge of installing a heavy tapestry, prone to floppiness, with a literal scaffold that contributes to the work’s meaning.

Figure 18 Installation view of Emelie Röndahl, Rana Plaza – the Collapse (April 24, 2013) (2015–16) in the Referensverk (Reference Works) exhibition at Handarbetets Vänner, Stockholm (April 6 – May 14, 2016).

Estonian designers Kärt Ojavee and Johanna Ulfsak collaborated with the artist Neeme Külm to solve the installation challenges of their large (heavy) handwoven textile in their Save As exhibition at the Temnikova & Kasela gallery in Talinn, Estonia (August 31 – October 27, 2018). Ojavee and Ulfsak wove with materials more familiar to mass production (PVC, glass fiber, optical fiber, and carbon fiber), accepting that variations in the cloth’s surface are an inevitable – even invited – aspect of their production method. While many of the materials Ojavee and Ulfsak chose are not at all friendly to touch, they are optically dynamic. The woven surface was sensitive even to small changes in light such as the viewer’s body movements in the long, narrow gallery space. The installation used techniques borrowed from tent assembly to hold the bar from which the work hangs through tension (rather than suspension) against the gallery walls (). While the woven textile is attached and suspended in a familiar manner, the tension holding the full structure means that access to both sides of the work is encouraged without the viewer needing to duck around a frame or “legs” in a gallery space that has the length to provide viewing distance, but little spare width.

Figure 19 Installation view of Kärt Ojavee and Johanna Ulfsak, Save As exhibition at the Temnikova & Kasela, Talinn, Estonia (August 31 – October 27, 2018). Handwoven PVC, glass fiber, optical fiber, and carbon fiber.

The final example in this section is the exhibition Still: Jessica Ogden shown in a vacant retail shop on Church Street, London (May 26 – June 23, 2017) (Hemmings Citation2017). The exhibition was curated by Carol Tulloch with exhibition design by Judith Clark, who trained as an architect and has worked on key fashion exhibitions, such as Spectres: when fashion turns back, cited for their design innovation (February 24 – May 8, 2005) (Hemmings Citation2005d). Jessica Ogden is arguably a textile lovers’ fashion designer and Still included clothing Ogden designed alongside fabric from her personal collection. Stitch and quilting are apparent throughout. Samples were carefully pinned and stitched onto horizontal upholstered trestle tables in a gesture that continues Ogden’s own logic of the central importance of stitch in her work, while elegantly solving the need to display part of the exhibition in a basement room beyond the gallery invigilators’ line of sight. The display solution allowed most of the textiles exhibited to escape entrapment behind glass without compromising their security in an exhibition run on a modest budget. The only objects held under glass are potentially pocketable exhibition invitations and small sewn jewelry (). Crucially, the use of stitch to display and secure Ogden’s exhibition shares Emelie Röndahl’s approach of finding display solutions that also contribute to the work’s meaning.

Figure 20 Installation view of Jessica Ogden: Still, Church Street, London (May 26 – June 23, 2017).

This article has reconsidered 13 textile exhibitions that have taken place in museums and galleries in Australia, England, Estonia, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United States over the past decade and a half. I have prioritized the importance of my first-hand experience of the exhibition in this research. My objective in writing this article is to note a variety of inspiring examples where sensitive, elegant, and effective exhibition installation techniques can be seen. In some cases, the techniques used to install the work contribute to the overall meaning of the works on display. In other cases, the exhibition techniques at least do not distract from the viewers’ experience.

I have considered exhibitions of textile art and textile design. While textile art is often made with the gallery setting in mind at the outset, techniques for the installation of textiles and the anxiety aroused in some contexts by the inherent floppiness of cloth create challenging installation demands. Textile design arguably presents yet another type of challenge in the fact that the end product of the textile design process is often yardage of fabric that, in the hands often of another designer, will later become an object of fashion or interiors. Here too an anxiety about the textile as an object to appreciate alone can pose a challenge. My objective in collecting and reflecting on these diverse examples is to inspire greater care and creativity in the exhibition decisions that contribute so significantly to the public’s appreciation and respect for textiles.

There is of course an irony in this endeavor, as the format of the published article re-flattens the embodied physical experience of the exhibition space back into the two-dimensional record of the photograph and text description. But navigating such ironies is another motivation of this article. I continue to see the textile exhibition as an important component of textile scholarship. Exhibition reviews, ideally, contribute to the health of textile discourse and, on many occasions, preserve the enormous amount of work behind transitory exhibitions that may not be accompanied by catalogs or other printed material. While the exhibition review is not a genre that enjoys academic recognition, there remains much knowledge that needs to be shared about the installation of textiles in gallery and museum spaces. If these challenges can be overcome, innovative installation techniques may become a more familiar sight in textile exhibitions around the world.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jessica Hemmings

Jessica Hemmings is Professor of Crafts and Vice-Prefekt of Research at the Academy of Design and Crafts (HDK), University of Gothenburg, Sweden. She is editor of In the Loop: Knitting Now (Black Dog: 2010), The Textile Reader (Bloomsbury: 2012) and Cultural Threads: transnational textiles today (Bloomsbury: 2015), author of Warp & Weft (Bloomsbury: 2012) and curator of the travelling exhibition Migrations (America, Ireland, Australia, England 2015–17). Research interests include contemporary craft and postcolonial literature.[email protected]

References

- Brown, L. 2016. The secrets we keep from ourselves. Unpublished installation manual.

- Brown, L. 2018. email correspondence with the author, December 19, 2018.

- Checinska, C. 2016. Accessed October 21, 2018. https://vimeo.com/242571907.

- Day, L., E. Gluckman, and F. Robins. 2018. “Unpicking the Narrative: Difficult Women, Difficult Work.” Textile 16 (3):311–319. doi:10.1080/14759756.2018.1432150.

- Dupré, F. 2015. email correspondence with the author, November 3, 2015.

- Fer, B. 2018. “Close to the Stuff the World Is Made of: Weaving as a Modern Project” Anni Albers, edited by Ann Coxon, Briony Fer and Maria Muller-Schareck, 20–43. London, UK: Tate Publishing.

- The Guardian. 2018. “Reliving the Rana Plaza factory collapse: a history of cities in 50 buildings, day 22” Accessed December 13, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/apr/23/rana-plaza-factory-collapse-history-cities-50-buildings.

- Hemmings, J. 2005a. “Playtime: Maria Blaisse” Selvedge Magazine, September/October issue 7: 48–51.

- Hemmings, J. 2005b. “2121: Reiko Sudo & NUNO” I.D. Magazine, November 19.

- Hemmings, J. 2005c. “Black, White and Shades of Grey”, Embroidery Magazine, July/August: 51.

- Hemmings, J. 2005d. “Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back” Selvedge Magazine, January/February. issue 4.

- Hemmings, J. 2006. “Yohji Yamamoto: Juste Des Vetements” Selvedge Magazine, pp. 88.

- Hemmings, J. 2012. “Fashioning the Object: Bless, Boudicca, and Sandra Backlund” Selvedge Magazine, issue 48: 91.

- Hemmings, J. 2014. “Form through Colour: Josef Albers, Anni Albers and Gary” The Surface Design Journal, Fall: 60–61.

- Hemmings, J. 2016a. Accessed November 30, 2018. http://www.norwegiancrafts.no/articles/unlearning-optical-illusions.

- Hemmings, J. 2016b. “Fiber” Textile, 14 (3), 404–407. doi:10.1080/14759756.2016.1167320.

- Hemmings, J. 2017. “Jessica Ogden: Still” Accessed November 30, 2018. https://garlandmag.com/article/jessica-ogden-still/

- Hemmings, J. 2018. “Material Color”, Norwegian Crafts, Accessed October 10 2018. http://www.norwegiancrafts.no/articles/material-color

- Hemmings, J. 2019. “Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion” Fashion Theory, doi:10.1080/1362704X.2018.1560931.

- Maharaj, S. 2001. “Textile Art – Who Are You?” In Reinventing Textiles: Gender & Identity Telos, 7–10. Winchester, England.

- McEvilley, T. 1986. “Introduction” inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, 7–12, Santa Monica & San Francisco, CA: The Lapis Press.

- Palmer, A. 2008. “Reviewing Fashion Exhibitions.” Fashion Theory 12 (1):121–126.

- Sherlock, M. P. 2007. “Piecework: home, Factory, Studio, Exhibit.” In The Object of Labor: Art, Cloth and Cultural Production, edited by Joan Livingstone and John Ploof, 1–30. Chicago, IL: School of the Art Institute of Chicago Press and The MIT Press.

- Tyson, J. 2016. “An Exhibition Ponders (and Perpetuates) the Hierarchy Between ‘Art’ and ‘Craft’ Accessed November 30, 2018. https://hyperallergic.com/264894/an-exhibition-ponders-and-perpetuates-the-hierarchy-between-art-and-craft/

- Von Mertens, A. 2018. email correspondence with the author, December 16, 2018.

- White Cube 2018. Accessed November 30 2018. https://whitecube.com/exhibitions/exhibition/losing_the_compass_masons_yard_2015.