ABSTRACT

Introduction

Invasive meningococcal disease due to serogroup B (MenB) is an uncommon but life-threatening disease. The 4-component meningococcal serogroup B vaccine (4CMenB) is the only MenB vaccine with real-world evidence supporting a reduction in incidence without safety concerns.

Areas covered

We reviewed recommendations and real-world implementation of 4CMenB in National Immunization Programs (NIPs) and implications for clinical practice through a non-systematic literature search.

Expert Opinion

4CMenB is registered in 45 countries, 33 of which recommend it clinically: nine for infants, children, adolescents, and high-risk groups; 11 for infants and high-risk groups; the US for individuals aged 16−23 years and high-risk groups; two for infants; 10 for high-risk groups and/or outbreak control. Dosing schedule varies between countries. To date, nine countries include 4CMenB in their NIP: UK, Andorra, Ireland, Italy, San Marino, Lithuania, Malta, Czech Republic, and Portugal. Australia funds it for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children under 2 years, and high-risk individuals. South Australia funds for all infants and adolescents. Many factors influenced introduction into NIPs: disease burden, public awareness, cost-effectiveness, prior meningococcal vaccination programs, efficacy and safety profile. In the future, more countries might consider including 4CMenB in their NIP due to growing evidence on effectiveness and safety.

1. Background

Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) is a leading cause of invasive bacterial disease worldwide [Citation1,Citation2]. Although uncommon, it is a life-threatening illness with rapid onset that can progress to death in as little as 24 to 48 hours, even with the best medical care [Citation3]. In addition, it is associated with severe complications; up to 20% of survivors have severe life-long sequelae (e.g. deafness, seizure, limb amputations) [Citation2,Citation4–6], and 1 in 10 cases lead to death [Citation2,Citation3]. IMD is caused by Neisseria meningitidis bacterium and varies geographically and over time. Meningococcal serogroup B (MenB) is predominant in the European Union (EU) (48% of cases in 2018) and the United States (US) (37% of cases in 2018), and is the leading cause of IMD [Citation2,Citation7–9].

Vaccination is regarded as the best strategy for IMD prevention and control [Citation10]. Two vaccines against MenB are available: the 4-component meningococcal serogroup B vaccine (4CMenB; Bexsero, GSK) and the MenB-fHbp vaccine (Trumenba, Pfizer). 4CMenB is generally indicated for prevention of MenB IMD in individuals from the age of 2 months, except in the US in which the vaccine is indicated from 10 to 25 years of age. MenB-fHbp is generally indicated for individuals from 10 years of age and from 10 to 25 years of age in the US. Hence, 4CMenB is currently the only broad coverage MenB vaccine that is recommended and used in infants, the age group in which the incidence is the highest [Citation11,Citation12].

With the widespread use of the 4CMenB, there is now real-world evidence (RWE) on the effectiveness, impact, and safety of the vaccine. The body of RWE demonstrates that the vaccine effectiveness (VE) is 59.1–93.6% and the vaccine impact is 71–96% [Citation13,Citation14]; protection lasts for up to 2 to 4 years [Citation14,Citation15] and the safety profile is consistent with data from clinical trials [Citation13,Citation16]. Additionally, RWE from the United Kingdom (UK) demonstrated a 69% reduction of meningococcal serogroup W (MenW) cases, indicating the potential for 4CMenB to protect against non-MenB IMD [Citation17,Citation18]. Other observational studies have indicated the potential of the vaccine to protect against Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection [Citation19,Citation20].

The MenB-fHbp vaccine has been less widely used than 4CMenB, since most countries, other than the US, have prioritized infants for MenB vaccination. From this perspective, the age indication of MenB-fHbp, from 10 years onward, may not have been consistent with the target population [Citation21]. However, MenB-fHbp has been used along with 4CMenB to successfully control MenB outbreaks in universities in the US and reassuringly no cases occurred in vaccinated individuals [Citation22].

In this review, we focus on 4CMenB registration, recommendations, and real-world implementation in National Immunization Programs (NIPs) and, where applicable, we discuss factors that lead to the decision to introduce MenB vaccine into the NIP. This review will help to further understanding of the implications of RWE and recommendations for clinical practice.

2. Country-specific approvals and recommendations for 4CMenB

4CMenB contains three main Neisseria protein antigens (NadA, NHBA, and variant 1 of fHBP) and the outer membrane vesicle derived from a New Zealand MenB outbreak [Citation10,Citation23]. Because IMD is uncommon, it was not feasible to conduct sufficiently powered studies to demonstrate vaccine efficacy before registration, and therefore 4CMenB was licensed based on immunogenicity and safety [Citation24,Citation25]. It was first licensed in the EU in 2013 and in the US in 2015 and is currently registered in 45 countries. In most countries, 4CMenB is licensed for infants from 2 months of age as a two-dose or three-dose series plus booster, and as a two-dose series from 2 years and above. In the US, it is licensed for 10–25-year-olds as a two-dose series with a minimum interval of 1 month between doses. Information on the approved age-specific dosing schedule for each country can be accessed by clicking on the country of interest in the interactive figure (Supplemental Figure 1).

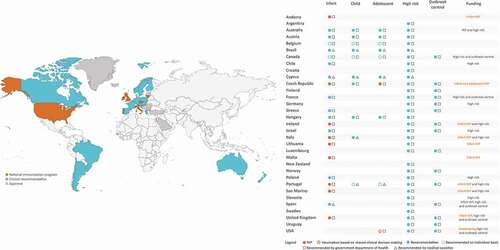

National expert bodies of 33 countries have made clinical recommendations (guidelines) for the use of 4CMenB (). In some countries, the recommendations have been issued by the government department of health, whilst in others, medical societies have issued the recommendations () [Citation26–62]. Most countries have recommendations based on age and for special populations at high risk of meningococcal disease. Risk-based recommendations generally include individuals with underlying medical conditions, close contacts of a case, travelers to high-risk countries, health care professionals, laboratory staff frequently exposed to Neisseria meningitidis, students or other young people living in close quarters or experiencing new lifestyles.

Figure 1. Targeted populations in countries with a clinical recommendation for 4CMenB vaccination.

Among the 33 countries with recommendations (), nine (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Hungary, and Portugal) recommend vaccination across a wide age range, including infants, children and adolescents, as well as high-risk groups. Eleven countries (Chile, France, Greece, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, San Marino, Spain, and UK) recommend vaccination in infants and high-risk groups (Italy additionally recommends vaccination in children). Andorra and Malta recommend vaccination in infants only. The remaining ten countries (Argentina, Croatia, Finland, Germany, Luxemburg, New Zealand, Norway, Slovenia, Sweden, Uruguay) recommend 4CMenB in high-risk groups and/or for outbreak control.

In the US, 4CMenB is recommended in adolescents 16−23 years (preferred age 16–18 years) based on shared clinical decision-making and for persons aged ≥10 years at increased risk (i.e. complement deficiency, asplenia, microbiologist); a MenB booster dose is recommended in high-risk individuals 1 year following primary series, followed by a booster dose every 2−3 years thereafter, for as long as increased risk remains [Citation62]. For persons aged ≥10 years at increased risk during an outbreak, a single booster dose at 1 year after completion of a MenB primary series and every 2−3 years thereafter is recommended [Citation62].

3. 4CMenB in National Immunization Programs

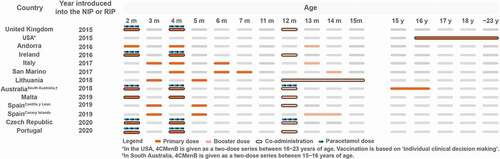

4CMenB has been introduced into the NIP in nine countries: UK, Andorra, Ireland, Italy, San Marino, Lithuania, Malta, Czech Republic and Portugal [Citation26,Citation47,Citation48,Citation50,Citation63–67]. Most recently (June 2021), the HAS (High Authority of Health) of France announced scientific recommendations for MenB vaccination, although further steps are needed for inclusion in the NIP [Citation68]. The vaccine is offered to infants in several different schedules with varying recommendations on co-administrations () [Citation69].

Figure 2. 4CMenB schedules in countries that have implemented 4CMenB in the National Immunization Program.

Uniquely in the US, MenB vaccination is recommended for individuals 16−23 years of age, preferred age 16–18 years, based on shared clinical decision-making. The vaccine is funded by private insurance or the Vaccines for Children program [Citation62].

Although 4CMenB is not offered as part of the NIP in Australia as a whole, it is funded for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children under 2 years, as well as for people of all ages with some underlying medical conditions; it is also funded in South Australia for all infants and adolescents [Citation28,Citation70].

Further details on the programs and publicly available considerations in the decision to implement a MenB program are described below and in Supplemental Figure 1; no publicly available information on considerations informing the decision-making are available for Andorra and San Marino.

3.1. United Kingdom

In September 2015, the UK became the first country to introduce 4CMenB into its NIP [Citation63]. 4CMenB is given at 2, 4 and 12 months of age and is co-administered with the hexavalent combination vaccine (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, Haemophilus influenzae b, hepatitis B [DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB]) and oral rotavirus vaccine at month 2, with the hexavalent vaccine at month 4 and with the Hib/Meningococcal serogroup C (MenC) vaccine, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) and the mumps, measles and rubella (MMR) vaccine at month 12 [Citation71]. Prophylactic paracetamol is given with the first two doses of 4CMenB to mitigate the risk of high fever; a 2.5 mL dose (120 mg/5 mL) of infant paracetamol is recommended at the time of vaccination or soon after, followed by two further doses at 4−6 hourly intervals [Citation60]. Prophylactic paracetamol is not recommended at the month 12 booster dose. In the first year of the program, catch-up vaccination was also opportunistically offered to infants aged 3 or 4 months attending their routine immunization visits [Citation17].

In 1999, the UK implemented routine MenC vaccination for all infants and an extensive catch-up campaign in response to a national outbreak of MenC disease. The program reduced the rate of MenC disease by 89−94% in age groups under 20 years during the first three years [Citation72]. In contrast, the incidence of MenB disease in infants <1 year of age was more than twice the EU/European Economic Area (EEA) average in 2014 (17.44/100,000 versus 7.56/100,000) [Citation7].

The UK’s Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunization (JCVI) initially ruled against the introduction of 4CMenB into the NIP based on an unfavorable cost-effectiveness assessment [Citation73]. This decision was widely challenged by multiple stakeholders objecting to continued deaths, disability and costs resulting from MenB disease, as well as discouragement of innovation in vaccine development [Citation74–76]. The cost-effectiveness analysis was reevaluated and several parameters were altered, including additional quality of life losses in the short term, new data on the rate of sequelae, litigation cost, quality of life losses to family members and a quality adjustment factor [Citation77,Citation78]. The analysis concluded that various scenarios could result in the vaccine being cost-effective if competitively priced [Citation78]. Following consideration of the new analysis, the JCVI recommended inclusion of 4CMenB in the infant immunization program [Citation77].

The UK 4CMenB infant program was successful, reaching a coverage of 93% for the first two doses and 88% for completion of the primary schedule and the booster dose [Citation15]. The UK program provided the first evidence of the real-world performance of 4CMenB in a national routine infant program. After 3 years, a 75% reduction in MenB disease was observed in age groups that were fully eligible for vaccination, irrespective of the vaccination status or predicted MenB strain coverage (incidence rate ratio 0.25; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.19 − 0.36) [Citation15]. An estimated 277 cases were prevented during the first 3 years of the program [Citation15]. This trend has continued into the fourth year of the program, with further reductions in MenB disease in children aged <5 years [Citation79]. In this study, VE for vaccinated versus unvaccinated children against MenB disease was not statistically significant at 59.1% (95% CI: −31.1, 87.2) after three doses [Citation15], likely due to the small number of unvaccinated cases. Interestingly, a surveillance study of MenW IMD reported a 69% reduction in cases in infants eligible for 4CMenB in the 4 years following introduction of the vaccine [Citation17] which supports in vitro studies reporting cross-reactivity of serum from 4CMenB-vaccinated individuals against MenW [Citation18,Citation80]. In a carriage study among nearly 3000 university students, a statistically significant difference was observed in recipients of 4CMenB versus control for any meningococcal strain (18.2% carriage reduction) and capsular groups BCWY (26.6% reduction), 3 months after the second vaccine dose [Citation81]. However, there was no significant difference in carriage prevalence for all serogroup B or serogroup B sequence types associated with disease [Citation81].

Several UK-based real-world studies have reported on the safety of the 4CMenB vaccine. A prospective surveillance study conducted during the first 20 months of the vaccination program identified no major safety concerns following more than three million doses administered to 1.3 million children aged 2−18 months [Citation16]. The rates of Kawasaki disease and convulsions remained consistent with background rates [Citation16]. The high coverage of the second and third doses demonstrated high parental acceptance of the vaccine [Citation16]. Another study reported that general practice consultations for fever of any cause during the year following 4CMenB introduction were 1.6-fold higher compared with the previous 2 years in infants aged 7−10 weeks and 1.5-fold higher in those aged 15−18 weeks [Citation82]. Overall, real-world studies have provided reassurance that the safety profile of 4CMenB in the UK vaccination program is consistent with that established in clinical trials.

3.2. Andorra

4CMenB was introduced into the childhood vaccination program in February 2016 and is given at 2, 4 and 13 months of age [Citation26]. It is recommended to be given alone, at least 2 weeks apart from other vaccines. If 4CMenB is given with other vaccines, prophylactic administration of paracetamol is recommended, given during or immediately after vaccination, followed by two more doses of paracetamol at an interval of 4−6 hours.

3.3. Ireland

In Ireland, MenB was introduced into the infant NIP in December 2016 and is offered at 2, 4 and 12 months [Citation64]. It is co-administered with hexavalent, PCV and oral rotavirus vaccines at month 2, with hexavalent and oral rotavirus vaccines at month 4 and with MMR at month 12. Recommendations for the administration of prophylactic paracetamol are the same as in the UK [Citation83].

Historically, Ireland had the highest rates of IMD in Europe [Citation7,Citation84]. The incidence peaked in 1999 at 11.92/100,000 (all ages) and gradually declined to 1.64/100,000 in 2014, mainly due to the success of the MenC program initiated in 2000 [Citation7]. With the reduction of MenC disease, MenB predominated and accounted for the majority of cases throughout the last 20 years [Citation84]. Interestingly, MenB rates have also spontaneously declined [Citation84]. Lifestyle changes such as the smoking ban in public places might have played a role, as well as secular trends [Citation85]. Nevertheless, in 2014, Ireland still had one of the highest rates of MenB disease, with an incidence of 26.79/100,000 in infants <1 year of age [Citation7]. A cost-effectiveness analysis of 4CMenB in 2013 that considered direct costs concluded that its introduction into the NIP had the capacity to reduce MenB disease in Ireland, albeit at a very high cost [Citation86]. Detailed surveillance and characterization of IMD isolates will be essential in discerning the impact of the MenB program in Ireland.

3.4. Italy and San Marino

4CMenB was included in the nationally funded vaccination programs in Italy and San Marino in 2017 [Citation47,Citation87]. In Italy, the schedule differs by region but is mainly offered at 3, 4, 6 and 13 months [Citation47,Citation69]. In San Marino, it is administered at 4, 6, 7 and 14 months of age [Citation65]. 4CMenB is not co-administered with other vaccines in Italy and San Marino. There are no recommendations regarding the use of prophylactic paracetamol.

In Italy during the surveillance period 2007−2012, MenB was responsible for 81% of all IMD cases in infants <1 year of age, 66% of cases in children 1−4 years and 70% in children 5−9 years [Citation87]. The incidence of IMD in Italy was highest in infants at 3.7/100,000 i.e. more than 10 times higher than the overall IMD incidence across all age groups [Citation87] with high case fatality rate of 13.2% [Citation88].

By 2015, seven Italian regions and one autonomous province (Bolzano) had included MenB in the childhood vaccination calendar and one region offered free vaccination to individuals at risk [Citation89]. The schedule varies among the regions, most starting at 2−3 months with a 3 + 1 schedule, whereas two regions and the autonomous province offer the vaccine starting from 7 months given as a 2 + 1 schedule [Citation47]. Since January 2017, 4CMenB has been provided free of charge by the Italian National Health Service across Italy [Citation47]. The national MenB program was implemented in accordance with the new National Vaccine Plan 2017−2019 which endeavored to eliminate differences between regions [Citation47].

It is likely that several other factors, including a steep increase in cases and media coverage, had an important role in the wider implementation of MenB vaccination [Citation89]. In Tuscany, IMD cases rose from 12 cases in 2013 to 43 cases in 2015 [Citation90]. In August 2016, a girl died of meningitis during World Youth Day. These events were covered by the media, increasing the public’s awareness of meningococcal disease and prevention methods [Citation91]. Recognition that the true burden of IMD might be underestimated in countries that rely only on culture for diagnosis of IMD also played a part [Citation92,Citation93], and a cost-effectiveness model accounting for such underestimation was published prior to introduction of MenB into the NIP [Citation94].

Following introduction of 4CMenB, an observational study in Tuscany and Veneto evaluated VE and overall impact from 2014 to 2018 [Citation95]. In Tuscany, the vaccine was given at 2, 4, 6 and 12−13 months of age, while in Veneto, it was given at 7, 9 and 15 months of age. In children 0−5 years of age, there were three MenB cases in unvaccinated children in Tuscany compared with one case in a vaccinated child, corresponding to VE of 93.6% (95% CI: 55.4, 99.1); in Veneto, there were five MenB cases in unvaccinated children and two cases in vaccinated children, corresponding to VE of 91.0% (95% CI: 59.9, 97.9) [Citation95]. The study reported a relative case reduction of 91% and 80% in MenB in Tuscany and Veneto, respectively, among vaccinated children [Citation95]. Considering the overall population of both vaccinated and unvaccinated children, the overall relative case reduction was 65% in Tuscany and 31% in Veneto [Citation95].

A study conducted in a single hospital in Rome evaluated adverse events occurring in 157 children presenting for 4CMenB vaccination. Infants receiving 4CMenB alongside routine primary vaccinations were given prophylactic paracetamol [Citation96]. The median age of the children was 4.5 years and 64% had chronic health conditions. Most adverse events were mild and of little clinical importance; the most frequent were injection site events, unusual crying, fever ≥37.5°C, hypotonia and hyporesponsiveness. No hospitalizations or emergency room visits were reported [Citation96].

3.5. Lithuania

4CMenB was introduced into the NIP in 2018, and is given at 3, 5 and 12−15 months [Citation48,Citation69]. It is given separately from other routine infant vaccines at months 3 and 5, but the booster dose at months 12−15 can be given with PCV and/or MMR vaccines. There are no official recommendations regarding the use of prophylactic paracetamol.

In Lithuania, the incidence of IMD and MenB has continued to rise during the last decade, in contrast to the overall decreasing trend in the EU/EEA [Citation7]. In 2017, the IMD incidence for all ages in Lithuania was the highest in the EU/EEA (2.39/100,000) [Citation7]. MenB was responsible for 49% of IMD, with the highest burden in infants <1 year of age (incidence 16.44/100,000) [Citation7].

3.6. Malta

In Malta, 4CMenB was introduced in the NIP in December 2019 and is offered at 2, 4 and 12 months [Citation50]. It is co-administered at 2 and 4 months with the hexavalent vaccine and PCV and at 12 months with PCV. There are no official recommendations concerning administration of prophylactic paracetamol.

The mean incidence of IMD in Malta was significantly higher than the mean average in the EU/EEA (1.49 versus 0.97 per 100,000) between 2000 and 2017 [Citation97]. Consistent with global epidemiology, the incidence was highest in infants (18.9/100,000), followed by young children (6.1/100,000) and adolescents (3.6/100,000) [Citation97]. Overall, MenB was the most frequent serogroup (63.5%) followed by MenC (24%), although serogroups W and Y increased in later years [Citation97].

3.7. Czech Republic

The Czech Republic announced the inclusion of 4CMenB into the NIP starting from May 2020 [Citation38–40]. 4CMenB is given to infants up to 6 months in a 2 + 1 schedule and can be administered with other vaccines. From January 2022, reimbursement has been extended to all infants up to 12 months of age and to adolescents at 14 years of age. The guidelines recommend use of prophylactic antipyretics at the time of or shortly after vaccination when 4CMenB is co-administered with multiple vaccines.

The rate of IMD has been below 1/100,000 in the Czech Republic since 2003 and has shown a decreasing trend over the last 15 years [Citation7]. MenB was the most frequent serogroup (54%), followed by MenC (35%), MenW (7%) and MenY (2%) in 2015−2017 [Citation98]. In infants <1 year of age, the incidence of MenB IMD was 3.55/100,000 in 2017, more than 10 times higher than the overall incidence across all age groups [Citation7].

3.8. Portugal

Portugal introduced 4CMenB into the NIP in October 2020 [Citation67]. 4CMenB is offered at 2, 4, and 12 months, co-administered at month 2 with the hexavalent vaccine and PCV, at month 4 with the pentavalent vaccine and PCV and at month 12 with PCV, MenC vaccine and MMR vaccine [Citation67]. Portugal has adopted the UK recommendation for use of prophylactic paracetamol.

Although the incidence of IMD has declined over the last two decades, as a result of secular trends as well as the impact of including MenC in the NIP from 2006, MenB is still an important cause of sepsis and meningitis in Portugal [Citation99]. In 2017, the rate of MenB was 0.31/100,000, accounting for approximately 65% of all IMD, and the highest burden occurred in infants <1 year of age (incidence 10.34/100,000) [Citation7].

Prior to introduction of 4CMenB in the NIP, coverage of the vaccine reached 57% by 2018, delivered entirely through private clinics [Citation14]. A matched case control study was conducted in children and adolescents during the period that 4CMenB was recommended but not reimbursed (2014−2019). In fully vaccinated individuals, VE was 79% (95% CI: 45, 92) against MenB IMD and 78% (95% CI: 47, 91) against all serogroup IMD. Among partially vaccinated individuals, corresponding VE was 82% (95% CI: 56, 92) and 77% (95% CI: 51, 89), respectively [Citation14].

3.9. United States

In the US, 4CMenB is recommended for individuals 16−23 years of age based on ‘shared clinical decision making,’ with a preference for vaccination at 16−18 years of age and for individuals at high risk from 10 years onward [Citation62]. The vaccine is given as a two-dose series with at least 1 month between doses and booster doses are recommended for those at increased risk [Citation62]. 4CMenB can be co-administered with other vaccines indicated for this age group, but at a different anatomic site, if possible.

MenB is currently the predominant serogroup in the US. During 2017−2018, MenB accounted for 37% of IMD cases, MenC for 26%, MenW for 6% and MenY for 12% across all age groups [Citation8,Citation9]. Among individuals 16−23 years of age, MenB accounted for 67% of IMD during 2017−2018 [Citation8,Citation9]. Ten university-based outbreaks caused by MenB occurred across seven states during 2013–2018, causing a total of 39 cases and two deaths [Citation22]. Implementing mass vaccination to control outbreaks required an immense mobilization of public health resources and many colleges and universities have since established recommendations for meningococcal vaccination upon entry [Citation100]. Despite the recommendation for MenB vaccination, a cross-sectional study using data from the National Immunization Survey-Teen found that coverage among individuals 17 years of age remained low: 14.5% in 2017 and 17.2% in 2018 for ≥1 dose, and 6.3% in 2017 and 8.4% in 2018 for ≥2 doses, with substantial regional variation [Citation101]. Receipt of other routine vaccinations and having Medicaid insurance increased the probability of receiving MenB vaccination [Citation101].

3.10. South Australia

Although not an NIP, the South Australia MenB program is noteworthy in that it is the only program to date that funds vaccination in both infants and adolescents [Citation70]. Infants are vaccinated at 2, 4 and 12 months and adolescents at 15−16 years (two doses, 8 weeks apart) [Citation70]. The program was initiated in infants in October 2018 and extended to adolescents in February 2019 [Citation70]. A catch up program was conducted in children <4 years of age and in adolescents and young adults up to 20 years of age [Citation70]. For infant immunization, it is recommended that 4CMenB is administered at 2 months (can be given from 6 weeks of age), 4 months and 12 months of age, alongside other routine infant vaccines in the NIP. Paracetamol is recommended with every 4CMenB dose for children aged less than 2 years at a dose according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The first dose of paracetamol is recommended within 30 minutes before vaccination or as soon as practicable thereafter, followed by two more doses 6 hours apart, even if the child does not have a fever.

The rate and proportion of MenB cases in South Australia is high, with MenB responsible for 82% of IMD cases in South Australia compared with 36% nationally in 2016 [Citation70]. Over the past decade, there have been 13 deaths from MenB in South Australia [Citation70]. Interestingly, South Australia has a higher disease rate in adolescents compared with national MenB reported cases, with almost a third of adolescent MenB cases in 2016 occurring in South Australia [Citation70]. South Australia is the first region globally to implement a MenB adolescent program. Data from this program might further support the use of 4CMenB in the adolescent population in other countries.

A cluster randomized trial conducted in South Australia evaluated the impact of 4CMenB on oropharyngeal carriage of disease-causing meningococci (groups A, B, C, W, X or Y) in adolescents 15−18 years of age [Citation102,Citation103]. Schools were randomized to receive the vaccine in 2017 (active group) or 2018 (control group) and 88% (30,522/34,489) of study participants received at least one dose of 4CMenB vaccine. The study reported no discernible effect on oropharyngeal carriage [Citation102], which is consistent with the carriage study in the UK mentioned earlier [Citation81]. A reduction of MenB disease of 71% (95% CI, 15% to 90%, p = 0.02) was observed compared with predicted based on pre-vaccine trends [Citation103]. Vaccine safety in the study was monitored via the South Australian Vaccine Safety Surveillance system. A total of 193 adverse events in 187 adolescents were reported, a reporting rate of 0.32% (95% CI: 0.28, 0.39) [Citation104]. The most common events were injection site reaction, headache, and nausea. There were nine serious adverse events, including two events of frozen shoulder and fever/malaise/raised liver enzymes considered medically significant; all serious adverse events were considered possibly related to the vaccine. Overall, the low reporting rate was reassuring, and no safety signals were identified [Citation104].

In Australia as a whole, MenB vaccination has been funded for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and for people of all ages with some underlying medical conditions since July 2020 [Citation28].

3.11. France

In June 2021, the HAS of France announced new scientific recommendations for MenB vaccination that include infants and the high-risk population [Citation105]. It aimed to promote individual protection of infants and to remove the financial barrier, which is one of the sources of unequal access to vaccination. Although further steps are needed for MenB vaccination inclusion in the NIP, it is expected to be added in the near future [Citation68,Citation105].

The recommendation was made considering the burden of disease and recognition of the severity of IMD and new data for 4CMenB (e.g. RWE, impact on MenW, 2 + 1 schedule etc.). In addition, arguments developed in the public consultation and during the stakeholder hearings were considered: 1) The lack of robust data on the long-term sequelae of IMDs and their consequences on the child’s environment; 2) The theoretical risk of an epidemic cycle upon lifting of measures to control the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (such measures having led to a reduction in the circulation of meningococci and likely to a decrease in the level of immunity of the population toward meningococci); 3) The impact of social inequalities in health on the frequency and time to management of infection; 4) The difficulties created by the availability of a vaccine that is not accessible to the most vulnerable social categories [Citation105].

4. Discussion

4CMenB is currently approved in 45 countries and 33 countries have made clinical recommendations for its use. Development of clinical recommendations is often the first step toward introducing the vaccine into routine immunization programs. Several countries with recommendations for 4CMenB have taken steps to increase access through public funding.

To date, nine countries have introduced 4CMenB into their NIP and most recently (June 2021), the HAS in France has announced a scientific recommendation to include MenB vaccination in its NIP. Many factors need to be considered when introducing a new vaccine into a national program i.e. public health priority, magnitude of disease burden, other strategies for preventing the disease, safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, its economic attributes, reliability of supply, and the capacity of the immunization program to successfully introduce the vaccine [Citation106].

Growing evidence on the real-world performance of the 4CMenB vaccine following its use in large populations provides reassurance on its effectiveness and safety profile. In addition, there is increasing literature supporting the need for comprehensive economic evaluation of disease prevention techniques like vaccination against MenB IMD. Cost-effectiveness analysis taking into account the broad disease burden of IMD (e.g. holistic and long-term impact on health care costs; incidence, severity, and sequelae; short- and long-term impact on patients’ quality of life) shows that routine infant vaccination with 4CMenB can be cost-effective [Citation94,Citation107–111].

In conclusion, it is likely that, as more data become available, the use of 4CMenB will increase, which in turn will enhance our understanding of its effectiveness, safety, and overall value.

5. Expert opinion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first paper looking to identify and map the current recommendations and immunization strategies for prevention of meningococcal B disease with the 4CMenB vaccine, with the intent of informing clinical practice. By definition, the registration of a vaccine in a given country is a major landmark, but is only the first step toward making the vaccine available and accessible to the indicated eligible population. Beyond approval, health care professionals refer to guidance on immunization practices from public health authorities and medical societies who develop recommendations for safe and appropriate use of vaccines; for example, in which eligible populations, at what age and according to which immunization schedules. Widespread use of a vaccine often depends upon whether it is adopted into publicly funded vaccination programs; vaccines that are funded by private insurances or are self-funded by families are usually less widely adopted.

Many factors are taken into consideration when governments make decisions to include, or not to include, a new vaccine as part of a publicly funded vaccination program. This manuscript reviews, where publicly available, the recommendations of each country where 4CMenB is registered. It also reviews the history and considerations taken into account in countries that have implemented a national or regional immunization program with 4CMenB to help prevent IMD due to serogroup B. It thus provides insights on how different countries evaluated the need for MenB immunization programs, including previous and current recommendations for meningococcal immunization practices, as well as how environmental factors such as media coverage might have had a role in increasing the awareness of the need for MenB vaccination, and in some cases informing the decision to include 4CMenB in publicly funded programs. The authors identified important factors influencing the decision to adopt 4CMenB, including disease incidence in the country, application of cost-effectiveness analyses that take into account the broad disease burden of IMD and its long-term impact on patients, as well as due consideration of equity challenges and the importance of removing financial barriers to help access to vaccination in the community. Understanding of the recommendations and national programs globally could provide further guidance on the use of 4CMenB and inform clinical practice and public health implementation.

The authors also reviewed the current real-world evidence generated in countries that have used 4CMenB widely. The review highlights that real-world evidence not only provides evidence on the outcomes of existing vaccination programs, but also informs governments that are considering introducing MenB vaccination into their national programs and may therefore support the decision-making process. This is especially relevant for vaccines against a disease like IMD, which is too rare to design and conduct efficacy trials prior to registration.

Currently, many countries recommend 4CMenB only in populations considered to be at high risk. Other countries have broader recommendations for the vaccine, but do not, as yet, provide public funding. This is not unexpected as new vaccines are often first prioritized for those at highest risk. In the future, the authors anticipate that the vaccine will be made available in more countries and recommendations will evolve to provide access to broader populations. Additionally, it is likely that decision-making processes for inclusion of the vaccine into publicly funded national programs will begin to routinely consider broader based cost-effectiveness analyses and give greater weight to issues of equitable access. It is expected that more countries may publicly share the discussions and considerations taken into account for decisions on recommendations and inclusion in vaccination programs. This will allow a more structured, evidence-based approach to guide new vaccine introduction and access.

Article highlights

We review current recommendations for the 4-component meningococcal serogroup B vaccine (4CMenB).

4CMenB is registered in 45 countries, 33 of which recommend it clinically; countries vary in whether they recommend for infants, children, adolescents, or high-risk groups.

Nine countries include 4CMenB in their National Immunization Program: UK, Andorra, Ireland, Italy, San Marino, Lithuania, Malta, Czech Republic, and Portugal. It is also funded in South Australia. The High Council of Health in France has recently recommended routine vaccination in infants.

Factors influencing the inclusion of 4CMenB in NIPs included: disease burden, public awareness, cost-effectiveness assessments, prior meningococcal vaccination programs, and efficacy and safety profile of the vaccine.

The growing evidence on the effectiveness and safety of 4CMenB might prompt more countries to consider including it in their NIP

Abbreviations

| 4CMenB: | = | 4-component meningococcal serogroup B |

| CI: | = | confidence interval |

| DTap: | = | diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis |

| EEA: | = | European Economic Area |

| EU: | = | European Union |

| HAS: | = | High Authority of Health |

| HepB: | = | Hepatitis B |

| Hib: | = | Haemophilus influenzae b |

| IMD: | = | invasive meningococcal disease |

| IPV: | = | Polio vaccine |

| JCVI: | = | Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunization |

| MenB: | = | meningococcal B |

| MenC: | = | meningococcal C |

| MenW: | = | meningococcal W |

| MenY: | = | meningococcal Y |

| MMR: | = | mumps, measles, rubella |

| NIP: | = | National Immunization Program |

| PCV: | = | pneumococcal conjugate vaccine |

| RIP: | = | Regional Immunization Program |

| RWE: | = | Real world evidence |

| UK: | = | United Kingdom |

| US: | = | United States |

| VE: | = | vaccine effectiveness |

Declaration of interest

WY Sohn, H Tahrat and R Bekkat-Berkani are employed by the GSK group of companies and hold chares in the GSK group of companies. P Novy was employed by the GSK group of companies and is now employed by Moderna. She also still holds shares in the GSK group of companies. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Author contributions

All authors participated in the conception and design of the review article and interpretation of the relevant literature and were involved in writing the review article or revising it for intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data and gave final approval before submission.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Trademark

Bexsero is a trademark owned by or licensed to the GSK group of companies. Trumenba is a trademark of Pfizer.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (74.7 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank the sponsor’s project staff for their support and contributions throughout manuscript development, especially Stephanie Garcia and Kinga Meszaros (Value Evidence), and Daniela Toneatto and Victoria Abbing-Karahagopian (Clinical and Epidemiology Development). The authors also thank Business & Decision Life Sciences platform (on behalf of GSK) for editorial assistance, manuscript coordination and writing support. Mary L Greenacre (An Sgriobhadair, UK, on behalf of GSK) provided medical writing services and Bruno Dumont (Business & Decision Life Sciences, on behalf of GSK) coordinated the manuscript development and editorial support. The work was presented previously at ESPID 2021.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rouphael NG, Stephens DS. Neisseria meningitidis: biology, microbiology, and epidemiology. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;799:1–20.

- World Health Organization. Fact sheet. Meningococcal meningitis. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/meningococcal-meningitis. Accessed: May 2020.

- Thompson MJ, Ninis N, Perera R, et al. Clinical recognition of meningococcal disease in children and adolescents. Lancet. 2006;367(9508):397–403.

- Viner RM, Booy R, Johnson H, et al. Outcomes of invasive meningococcal serogroup B disease in children and adolescents (MOSAIC): a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(9):774–783.

- Wang B, Santoreneos R, Giles L, et al., Case fatality rates of invasive meningococcal disease by serogroup and age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2019;37(21): 2768–2782.

- Dastouri F, Hosseini AM, Haworth E, et al., Complications of serogroup B meningococcal disease in survivors: a review. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2014;14(3): 205–212.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases. Available from: https://atlas.ecdc.europa.eu/public/index.aspx?Dataset=27&HealthTopic=36. Accessed: Apr 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Enhanced meningococcal disease surveillance report, 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/downloads/NCIRD-EMS-Report-2017.pdf. Accessed: Nov 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Enhanced meningococcal disease surveillance report, 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/downloads/NCIRD-EMS-Report-2018.pdf. Accessed: May 2020.

- Pizza M, Bekkat-Berkani R, Rappuoli R. Vaccines against meningococcal diseases. Microorganisms. 2020;8(10):1521.

- European Medicines Agency. Bexsero. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/bexsero. Accessed: Jun 2021.

- Harrison LH, Pelton SI, Wilder-Smith A, et al. The Global Meningococcal Initiative: recommendations for reducing the global burden of meningococcal disease. Vaccine. 2011;29(18):3363–3371.

- Martinón-Torres F, Banzhoff A, Azzari C, et al. Recent advances in meningococcal B disease prevention: real-world evidence from 4CMenB vaccination. J Infect. 2021;83(1):17–26.

- Rodrigues FMP, Marlow R, Simões MJ, et al. Association of use of a meningococcus group B vaccine with group B invasive meningococcal disease among children in Portugal. Jama. 2020;324(21):2187–2194.

- Ladhani SN, Andrews N, Parikh SR, et al. Vaccination of infants with meningococcal group B vaccine (4CMenB) in England. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(4):309–317.

- Bryan P, Seabroke S, Wong J, et al. Safety of multicomponent meningococcal group B vaccine (4CMenB) in routine infant immunisation in the UK: a prospective surveillance study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(6):395–403.

- Ladhani SN, Campbell H, Andrews N, et al. First real world evidence of meningococcal group B vaccine, 4CMenB, protection against meningococcal group W disease; prospective enhanced national surveillance, England. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(7):e1661–e1668.

- Biolchi A, De Angelis G, Moschioni M, et al. Multicomponent meningococcal serogroup B vaccination elicits cross-reactive immunity in infants against genetically diverse serogroup C, W and Y invasive disease isolates. Vaccine. 2020;38(47):7542–7550.

- Abara WE, Jerse AE, Hariri S, et al. Planning for a gonococcal vaccine: a narrative review of vaccine development and public health implications. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48(7):453–457.

- Longtin J, Dion R, Simard M, et al. Possible impact of wide-scale vaccination against serogroup B Neisseria meningitidis on gonorrhea incidence rates in one region of Quebec, Canada. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:S734–S735.

- Patton ME, Stephens D, Moore K, et al. Updated recommendations for use of MenB-FHbp serogroup B meningococcal vaccine - Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(19):509–513.

- Soeters HM, McNamara LA, Blain AE, et al. University-based outbreaks of meningococcal disease caused by serogroup B, United States, 2013-2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(3):434–440.

- O’Ryan M, Stoddard J, Toneatto D, et al., A multi-component meningococcal serogroup B vaccine (4CMenB): the clinical development program. Drugs. 2014;74(1): 15–30.

- Rappuoli R, Pizza M, Masignani V, et al. Meningococcal B vaccine (4CMenB): the journey from research to real world experience. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17(12):1111–1121.

- Borrow R, Taha MK, Giuliani MM, et al., Methods to evaluate serogroup B meningococcal vaccines: from predictions to real-world evidence. J Infect. 2020;81(6): 862–872.

- Govern d’Andorra. Ministeri de Salut. Nota informativa. Recomanacions sobre l’administració de la vacunacióenfront del meningococ B (Bexsero). February 2016. Available from: https://www.salut.ad/images/stories/Salut/pdfs/temes_salut/Recomanacions_Vacuna_Bexero.pdf. Accessed: May 2020.

- Ministry of Health Argentina. Argentina’s meningococcal vaccination strategy guidelines. Available from: https://bancos.salud.gob.ar/recurso/huespedes-especiales-estrategia-de-vacunacion-contra-meningococo-de-argentina Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Australian Government Department of Health. National Immunisation Program. Meningococcal vaccination schedule from 2020 Jul 1. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/06/national-immunisation-program-meningococcal-vaccination-schedule-from-1-july-2020-clinical-advice-for-vaccination-providers.pdf. Accessed: Oct 2020.

- Government of South Australia. Meningococcal B immunisation program. Available from: https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/conditions/immunisation/immunisation+programs/meningococcal+b+immunisation+program Accessed: 2021 Dec 8.

- Federal Ministry of Health Austria. Impfplan Osterreich. Available from: https://www.sozialministerium.at/Themen/Gesundheit/Impfen/Impfplan-%C3%96sterreich.html Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Superior Council of Health Belgium. CSS-9485, revision 2019. Available from: https://www.health.belgium.be/sites/default/files/uploads/fields/fpshealth_theme_file/shc_9485_meningococcal_vaccination_2019_1.pdf Accessed: 2021 Dec 8.

- Brazilian Society of Pediatrics. Calendário de Vacinação da SBP 2020. Available from: https://www.sbp.com.br/fileadmin/user_upload/22268g-DocCient-Calendario_Vacinacao_2020.pdf. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Public Health Canada. Meningococcal vaccine. Canadian immunization guide. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-13-meningococcal-vaccine.html Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. NACI statement 2014. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/aspc-phac/HP40-104-2014-eng.pdf. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Ministry of Health Chile. Recomendaciones para la vacunación de pacientes con necesidades especiales por patologías o situaciones de riesgo. Available from: https://vacunas.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Recomendaciones-para-la-vacunación-de-pacientes-con-necesidades-especiales.pdf. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Ministry of Health Croatia. National Immunization programme. Available from: https://zdravlje.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/2020%20Programi%20i%20projekti/Izmjene%20i%20dopuna%20Provedbenog%20programa%20cijepljenja%20II%20u%202020.pdf Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Cyprus Paediatrics Society. Recommendations. Available from: http://www.child.org.cy/vaccination-2017/. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Czech National Institute of Public Health. Očkování proti meningokokovým onemocněním. Available from: http://www.szu.cz/ockovani-proti-meningokokovym-onemocnenim. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Czech Vaccinology Society. News: payment for vaccination of children against meningococci from 1.5.2020. Available from: https://www.vakcinace.eu/novinky. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Czech Vaccinology Society. Recommendations of the Czech Vaccinology Society of the J. E. Purkyně Czech Medical Association for Vaccination against Invasive Meningococcal Disease Available from: http://www.szu.cz/uploads/IMO/2020_Recommendation_vaccination_IMD.pdf Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. Meningococcus B vaccine. Available from: https://thl.fi/en/web/infectious-diseases-and-vaccinations/vaccines-a-to-z/meningococcal-vaccines/meningococcus-b-vaccine. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Haut Conseil de la Santé Publique. HCSPA Bexsero recommendations. Available from: http://www.hcsp.fr/Explore.cgi/Telecharger?NomFichier=hcspa20131025_vaccmeningocoqueBBexsero.pdf. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Greek Paediatric Society. EIA recommendations for vaccines. Available from: http://e-child.gr/update-education/education-recommendations-for-vaccinations/. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Robert Koch Institute. Recommendations of the standing committee on vaccination (STIKO) at the Robert Koch Institute – 2017/2018. Available from: https://www.rki.de/EN/Content/infections/Vaccination/recommandations/34_2017_engl.pdf?__blob=publicationFile Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- National Immunisation Office Republic of Ireland. Current schedule. Available from: https://www.hse.ie/eng/health/immunisation/pubinfo/currentschedule.html. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Israel. IDAC 2019. Available from: https://www.health.gov.il/Services/Committee/IDAC/Documents/CSV_02012019.pdf. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Ministero della Salute Italy. Piano Nazionale prevenzione vaccinale 2017-2019. Available from: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2571_allegato.pdf. Accessed: May 2020.

- Ministry of Health Republic of Lithuania. Dėl lietuvos respublikos sveikatos apsaugos ministro. 2015 m. BIRŽELIO 12 d. įsakymo nr. V-757 „DĖL Lietuvos respublikos vaikų profilaktinių skiepijimų kalendoriaus patvirtinimo“ pakeitimo. Available from: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/f4a925d0f50f11e79a1bc86190c2f01a?positionInSearchResults=0&searchModelUUID=1561434a-b283-4be2-87f5-4f556ad37c32. Accessed: May 2020.

- Higher Council of Infectious Diseases Luxembourg. La vaccination contre le meningocoque groupe B. Available from: http://sante.public.lu/fr/espace-professionnel/recommandations/conseil-maladies-infectieuses/meningite/2018-avis-vaccination-meningocoque-groupe-b.pdf. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Ministry for Health Malta. National immunisation schedule 2020. Available from: https://deputyprimeminister.gov.mt/en/phc/pchyhi/Pages/National-Immunisation-Schedule.aspx. Accessed: Apr 2021.

- The Immunisation Advisory Centre New Zealand. Bexsero. Available from:http://www.immune.org.nz/vaccines/available-vaccines/bexsero Accessed: Nov 2020.

- Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Meningococcal disease vaccine. Available from: https://www.fhi.no/en/op/vaccination-guidance/vaccines-offered-in-norway/meningococcal-disease/. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Ministry of Health Poland. Programu Szczepień Ochronnych na rok 2019. Available from: https://gis.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/akt.pdf. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Sociedade de Infeciologia Pediatrica e Sociedade Portuguesa de Pediatrica. Recomendações sobre vacinas extra programa nacional de vacinação. Available from: https://www.spp.pt/UserFiles/file/Seccao_Infecciologia/recomendacoes%20vacinas_sip_final_28set_2.pdf. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Gabinete do Secretário de Estado da Saúde. Despacho n.° 12434/2019. Available from: https://dre.pt/dre/LinkFicheiroAntigo?conteudoId=127608823. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Istituto per la Sicurezza Sociale San Marino. Vaccinazioni raccomandate. Available from: http://www.iss.sm/on-line/home/vaccini-e-vaccinazioni/vaccinazioni-raccomandate.html. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- National Institute za Javno Zdravje Slovenia. Available from: https://www.nijz.si/sl/publikacije/cepljenje-otrok-knjizica-za-starse. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Moreno-Pérez D, Álvarez García FJ, Álvarez Aldeán J, et al. Immunisation schedule of the Spanish association of paediatrics: 2019 recommendations. An Pediatr (Engl Ed). 2019;90(1):56.e51–56.e59.

- Swedish Public Health Agency. Recommendations on preventive measures against invasive meningococcal infection. Available from: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/941f1dd281b24e75b6e6d46d490b4d1d/rekommendationer-om-forebyggande-atgarder-mot-invasiv-meningokockinfektion.pdf. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Public Health England. Immunisation against infectious disease. Meningococcal: the green book, chapter 22. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/meningococcal-the-green-book-chapter-22. Accessed: Dec 2021.

- Uruguayan Society of Pediatrics. Inform tecnico - enfermedad meningococcia en Uruguay 2017. Available from: https://www.sup.org.uy/2017/12/21/informe-tecnico-enfermedad-meningococcia-en-uruguay-2017/. Accessed 2021 Dec 8.

- Mbaeyi S, Bozio C, Duffy J. Meningococcal vaccination: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1–41.

- Parikh SR, Andrews NJ, Beebeejaun K, et al. Effectiveness and impact of a reduced infant schedule of 4CMenB vaccine against group B meningococcal disease in England: a national observational cohort study. Lancet. 2016;388(10061):2775–2782.

- National Immunisation Office Republic of Ireland. Primary childhood immunisation schedule. Available from: https://www.hse.ie/eng/health/immunisation/pubinfo/pcischedule/immschedule/. Accessed: May 2020.

- Istituto per la Sicurezza Sociale San Marino. Delibera n.38 del 21/03/18 Modifica calendario vaccinale per le vaccinazioni obbligatorie e raccomandate. Available from: http://www.iss.sm/on-line/home/vaccini-e-vaccinazioni/vaccinazioni-obbligatorie-a-san-marino/riferimenti-legislativi.html. Accessed: Apr 2021.

- Ceska Vakcinologicka Spolecnost CLS JEP. Available from: https://www.vakcinace.eu/. Accessed: Jul 2020.

- Gabinete do Secretário de Estado da Saúde. Aprova o novo esquema vacinal do Programa Nacional de Vacinação (PNV), revo-gando, com exceção do seu n. 6, o Despacho n.° 10441/2016, de 9 de agosto. Available from: https://dre.pt/application/conteudo/127608823. Accessed: Aug 2020.

- Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS). Stratégie de vaccination pour la prévention des infections invasives à méningocoques: le sérogroupe B et la place de BEXSERO®. Available from: https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/p_3066921/fr/strategie-de-vaccination-pour-la-prevention-des-infections-invasives-a-meningocoques-le-serogroupe-b-et-la-place-de-bexsero. Accessed 2021 Nov 27.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. ECDC Vaccine Scheduler. Available from: https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/Scheduler/ByDisease?SelectedDiseaseId=48&SelectedCountryIdByDisease=−1. Accessed: Aug 2020.

- Marshall HS, Lally N, Flood L, et al. First statewide meningococcal B vaccine program in infants, children and adolescents: evidence for implementation in South Australia. Med J Aust. 2020;212(2):89–93.

- Public Health England. The routine immunisation schedule. From June 2020. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-complete-routine-immunisation-schedule. Accessed: Apr 2021.

- Campbell H, Borrow R, Salisbury D, et al. Meningococcal C conjugate vaccine: the experience in England and Wales. Vaccine. 2009;27 Suppl 2:B20–29.

- Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation. JCVI interim position statement on use of Bexsero meningococcal B vaccine in the UK. July 2013. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/224896/JCVI_interim_statement_on_meningococcal_B_vaccination_for_web.pdf. Accessed: May 2020.

- Moxon R, Snape MD. The price of prevention: what now for immunisation against meningococcus B? Lancet. 2013;382(9890):369–370.

- Blewitt J. Immunisation against meningococcus B. Lancet. 2013;382(9895):857–858.

- Head C. Immunisation against meningococcus B. Lancet. 2013;382(9896):935.

- Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation. JCVI position statement on use of Bexsero meningococcal B vaccine in the UK. March 2014. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/294245/JCVI_Statement_on_MenB.pdf. Accessed: May 2020.

- Christensen H, Trotter CL, Hickman M, et al. Re-evaluating cost effectiveness of universal meningitis vaccination (Bexsero) in England: modelling study. Bmj. 2014;349:g5725.

- Isitt C, Cosgrove CA, Ramsay ME, et al. Success of 4CMenB in preventing meningococcal disease: evidence from real-world experience. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105(8):784–790.

- Ladhani SN, Giuliani MM, Biolchi A, et al. Effectiveness of meningococcal B vaccine against endemic hypervirulent Neisseria meningitidis W strain, England. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(2):309–311.

- Read RC, Baxter D, Chadwick DR, et al. Effect of a quadrivalent meningococcal ACWY glycoconjugate or a serogroup B meningococcal vaccine on meningococcal carriage: an observer-blind, phase 3 randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9960):2123–2131.

- Harcourt S, Morbey RA, Bates C, et al. Estimating primary care attendance rates for fever in infants after meningococcal B vaccination in England using national syndromic surveillance data. Vaccine. 2018;36(4):565–571.

- National Immunisation Office Republic of Ireland. Immunisation. Meningococcal B. Available from: https://www.hse.ie/eng/health/immunisation/hcpinfo/othervaccines/meningococcalb/#Paracetamol%20after%20MenB%20vaccine. Accessed: Apr 2021.

- Bennett D, O’Lorcain P, Morgan S, et al. Epidemiology of two decades of invasive meningococcal disease in the Republic of Ireland: an analysis of national surveillance data on laboratory-confirmed cases from 1996 to 2016. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147:e142.

- Kabir Z, Manning PJ, Holohan J, et al. Active smoking and second-hand-smoke exposure at home among Irish children, 1995-2007. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(1):42–45.

- National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics. Economic evaluation of a universal meningitis B vaccination programme in Ireland. Available from: http://www.ncpe.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Meningitis-B-vaccine-Feb-2014.pdf. Accessed: Nov 2020.

- Rota M, Bella A, D’Angelo F, et al. Vaccinazione anti-meningococco B: dati ed evidenze disponibili per l’introduzione in nuovi nati e adolescenti. Roma: istituto Superiore di Sanità; 2015. (Rapporti ISTISAN 15/12). Available from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwi3juDajNX0AhVDZMAKHTBLA34QFnoECAIQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.scienzainrete.it%2Ffiles%2F15_12.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1E2zXD1bsfZKm46V6TRztG. Accessed: Aug 2020.

- Azzari C, Canessa C, Lippi F, et al. Distribution of invasive meningococcal B disease in Italian pediatric population: implications for vaccination timing. Vaccine. 2014;32(10):1187–1191.

- Gasparini R, Amicizia D, Lai PL, et al. Meningococcal B vaccination strategies and their practical application in Italy. J Prev Med Hyg. 2015;56(3):E133–139.

- Stefanelli P, Miglietta A, Pezzotti P, et al. Increased incidence of invasive meningococcal disease of serogroup C / clonal complex 11, Tuscany, Italy, 2015 to 2016. Euro Surveill. 2016;21(12). https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.12.30176.

- Covolo L, Croce E, Moneda M, et al. Meningococcal disease in Italy: public concern, media coverage and policy change. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1061.

- Azzari C, Nieddu F, Moriondo M, et al. Underestimation of invasive meningococcal disease in Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(3):469–475.

- Alfonsi V, D’Ancona F, Giambi C, et al. Current immunization policies for pneumococcal, meningococcal C, varicella and rotavirus vaccinations in Italy. Health Policy. 2011;103(2–3):176–183.

- Gasparini R, Landa P, Amicizia D, et al. Vaccinating Italian infants with a new multicomponent vaccine (Bexsero®) against meningococcal B disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(8):2148–2161.

- Azzari C, Moriondo M, Nieddu F, et al. Effectiveness and impact of the 4CMenB vaccine against group B meningococcal disease in two Italian regions using different vaccination schedules: a five-year retrospective observational study (2014-2018). Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8(3):469.

- Nicolosi L, Rizzo C, Gattinara GC, et al. Safety and tolerability of meningococcus B vaccine in patients with chronical medical conditions (CMC). Ital J Pediatr. 2019;45(1):133.

- Pace D, Gauci C, Barbara C. The epidemiology of invasive meningococcal disease and the utility of vaccination in Malta. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;39(10):1885–1897.

- Krizova P, and Honskus M. Genomic surveillance of invasive meningococcal disease in the Czech Republic, 2015-2017. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219477.

- Repositório Científico do Instituto Nacional de Saúde. Epidemiology of invasive meningococcal disease in Portugal in the last decade – 2007-2016. Available from: http://repositorio.insa.pt/handle/10400.18/5176. Accessed: Aug 2020.

- Capitano B, Dillon K, LeDuc A, et al. Experience implementing a university-based mass immunization program in response to a meningococcal B outbreak. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(3):717–724.

- La EM, Garbinsky D, Hunter S, et al. Meningococcal B vaccination coverage among older adolescents in the United States. Vaccine. 2021;39(19):2660–2667.

- Marshall HS, McMillan M, Koehler AP, et al. Meningococcal B vaccine and meningococcal carriage in adolescents in Australia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(4):318–327.

- McMillan M, Wang B, Koehler AP, et al. Impact of meningococcal B vaccine on invasive meningococcal disease in adolescents. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(1):e233–237.

- Marshall HS, Koehler AP, Wang B, et al. Safety of meningococcal B vaccine (4CMenB) in adolescents in Australia. Vaccine. 2020;38(37):5914–5922.

- Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS). La HAS recommande la vaccination des nourrissons contre le méningocoque B. Les pros de la petit enfance. Available from: https://lesprosdelapetiteenfance.fr/la-has-recommande-la-vaccination-des-nourrissons-contre-le-meningocoque-b. Accessed 2021 Nov 27.

- World Health Organization. Principles and considerations for adding a vaccine to a national immunization programme. 2014. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/111548/9789241506892_eng.pdf;jsessionid=75F9B7C9D6282EC802B908056D1EEE98?sequence=1. Accessed: Jul 2020.

- Christensen H, Al-Janabi H, Levy P, et al. Economic evaluation of meningococcal vaccines: considerations for the future. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(2):297–309.

- Stawasz A, Huang L, Kirby P, et al. Health technology assessment for vaccines against rare, severe infections: properly accounting for serogroup B meningococcal vaccination’s full social and economic benefits. Front Public Health. 2020;8:261.

- Beck E, Klint J, Neine M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of 4CMenB infant vaccination in England: a comprehensive valuation considering the broad impact of serogroup B invasive meningococcal disease. Value Health. 2021;24(1):91–104.

- Sevilla J, Tortorice D, Kantor D, et al. PIN43 Lifecycle-model-based economic evaluation of infant meningitis B vaccination in the UK. Value Health. 2019;22(Supplement 3):S647.

- Mauskopf J, Masaquel C, Huang L. Evaluating vaccination programs that prevent diseases with catastrophic health outcomes: how can we capture the value of risk reduction? Value Health. 2021;24(1):86–90.