ABSTRACT

Introduction

Vaccine hesitancy is described by the WHO as one of the top threats to global health. The trajectory of the current COVID-19 pandemic depends upon the vaccination of a global population; therefore, barriers to routine vaccination within marginalized groups considered vaccine hesitant are of critical importance. Consistently, vaccination levels within Roma communities across Europe rate very poorly in comparison with general population coverage, and a number of measles and hepatitis outbreaks over the past 10 years have included Roma communities. This study aims to identify barriers to Roma vaccination in general with a view to informing analysis of potential low levels of vaccination within Roma communities for COVID-19.

Areas covered

The research question explores factors and barriers affecting general vaccine (non-COVID-19 vaccine) uptake within Roma communities across Europe. This scoping review was conducted using the Arksey & O’Malley framework, complying with PRISMA-SR for Scoping Review guidelines.

Expert opinion

Using Thomson’s 5A’s Taxonomy, access was identified as the greatest barrier to vaccination within Roma communities. Access factors had the greatest number of references in this scoping review and were considered the most relevant in terms of increasing vaccination uptake. Important access themes identified are health system issues, socioeconomic conditions, and mobility.

1. Introduction

This scoping review sets out to examine the factors affecting routine (non-COVID-19) vaccine uptake within Roma communities across Europe in an effort to inform and influence current COVID-19 vaccination programs that target communities such as Roma, considered by many public health initiatives as ‘hard to reach’ and vaccine hesitant.

Roma communities have a long history of being marginalized and discriminated against across Europe, including genocide, forced sterilization, expulsion from certain countries, linguistic and cultural oppression, slavery, and persistent and endemic racism [Citation1]. Consequently, Roma communities, whilst neither homogeneous, well-defined nor distinct, remain some of the most disadvantaged populations across the EU, resulting in significantly poor health outcomes as well as difficulty accessing housing, education, employment, and representation in public life [Citation2,Citation3].

There are an estimated 10–12 million Roma living across the EUFootnote1 member states [Citation4], 80% of whom live below the poverty line [Citation5].

Antigypsism or racism directed at Roma continues unabated in the 21st century and evidence suggests that it has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. The European Union (EU) Roma Strategic Framework for Equality, Inclusion, and Participation identifies antigypsism as the prevailing majority view formed by ‘a historically rooted structural phenomenon’ [Citation4]. Matache and Bhabha refer to it as ‘a licence to unleash racism against stigmatised groups’ that has resulted in Roma communities being portrayed as impervious to public health guidance, mobile when advised not to be and living in unsanitary conditions – thereby facilitating the transmission of disease [Citation6]. In Bulgaria, planes have flown over Roma neighborhoods spraying disinfectants on the houses and streets below. In Portugal, fences have been built around Roma communities to prohibit free movement, and many Roma communities have faced lockdowns as precautionary measures, including Bulgaria, Greece, Portugal, Romania, and Slovakia, whilst no evidence existed of COVID-19 positive cases within the community at that time [Citation7]. In the European Parliament, a Bulgarian member of the European Parliament (MEP) referred to Roma communities as ‘nests of contagion’ and the Mayor of Kosice in Slovakia referred to them as ‘socially unadaptable people’ in defense of his public health arrangements to segregate Roma communities [Citation6].

Consequently, at the outset of this analysis, current evidence suggests that this widely discriminated-against group has experienced increasing hardship and become further marginalized during the COVID-19 pandemic. This could be attributed to the social determinants of health that are pervasive in Roma communities, sudden changes to their way of life introduced by a variety of COVID-19 restrictions, and, in some cases, stigmatization and isolation from individual country’s COVID-19 response efforts.

Furthermore, Roma communities are disproportionately affected by communicable diseases, such as measles, hepatitis, and tuberculosis [Citation8] and are less likely to engage with healthcare services for a variety of reasons, some of which this review will examine. Healthcare systems that are difficult for Roma to access combined with poor living conditions that Roma experience in many countries disproportionately expose Roma to increased risks from COVID-19, including infection, community transmission, hospitalization, and death [Citation3,Citation9].

Despite the fact that members of the Roma community are more likely to develop health problems than other groups in society, evidence suggests that there is a low uptake of preventative health care such as vaccination [Citation10,Citation11]. McFadden reported in her analysis of 99 studies from 32 countries on GRT (an umbrella term for Gypsy, Roma, Traveler populations) engagement with health services that the barriers to engagement include health system design, discrimination by health system personnel, culture and language, health literacy, individual traits, and socio-economic factors [Citation3]. Some of these barriers are heightened by a lack of health insurance, lack of official documentation, Roma mobility patterns, language and communication issues, as well as human rights violations in some instances [Citation12].

Interventions which aim to increase vaccine uptake are required to connect with communities that are repeatedly highlighted as being isolated from vaccination programs [Citation13]. To understand why some communities such as Roma are isolated and hard to reach, health professionals should first consider the intersectionality of public health and inadequate housing, poor sanitation, and low income and its impact on vaccination decision-making. To understand the barriers to routine vaccination rates being considerably lower in Roma communities than those of the general population, one must consider the wider context of how Roma communities live.

Due to the 2–3 million deaths prevented annually through vaccination, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified low vaccination rates as one of the top 10 global health threats in 2019 [Citation14]. The Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE), the principal advisory group to the World Health Organization (WHO) on vaccines and immunization, has defined vaccine hesitancy as a ‘delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services. Vaccine hesitancy is complex and context specific, varying across time, place and vaccines. It is influenced by factors such as complacency, convenience and confidence’ [Citation15].

Much of the evidence surrounding the determinants of Roma health highlights lower levels of health literacy within the Roma community. Consequently, as COVID-19 vaccination programs are rolled out globally, unpacking the barriers to routine immunization within the community is an urgent public health priority. In an effort to scrutinize potential barriers to the COVID-19 vaccination, this scoping review seeks to present an overview of patterns of poor vaccination uptake in general and attributable factors within Roma populations.

2. Methods

2.1. Identifying the research question

Scoping reviews are considered particularly relevant and useful for investigating a range of complex health issues such as vaccine hesitancy [Citation16]. This scoping review uses the Arksey and O’Malley framework for conducting scoping reviews [Citation17] as well as updated 2020 guidance on conducting scoping reviews [Citation18]. Applying the PCC (Population, Concept, Context) framework, recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute for Scoping Reviews, the authors wanted to examine the Roma community and the factors affecting their uptake of vaccines, within a European context. The research question examines the literature that exists on the subject of vaccine hesitancy within Roma communities, identifying common themes across the UK and Europe that highlight the root causes of low uptake of routine vaccinations within this community and any particular characteristics specifically relevant to Roma.

2.2. Identifying relevant studies

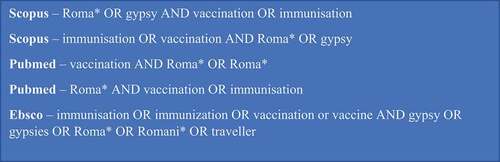

Having consulted with Librarian services in the University of Limerick and colleagues in Public Health, the following databases were searched: UL, Scopus, PubMed, and Ebsco including Academic Search Complete, APA PsychInfo, CINAHL Complete, MEDLINE (with full text), and the UK & Ireland Reference Center. The final search was completed on 17 July 2021. The following search terms were applied, using a variation of MEsH terms, title/abstract/key words, text words, or subject terms ();

2.3. Study selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established at the beginning, and articles considered appropriate to include were peer reviewed articles published in 2006 or afterward, with full text available in English, detailing studies that covered Roma communities living in Europe. The population comprises Roma children and/or adults and the study outcomes include assessing the literature that exists around Roma vaccination; assessing the literature on Roma refusing vaccination for adults/children; exploring the reasons behind low vaccination uptake; and examining strategies targeting and working with Roma populations to increase vaccination rates. All types of studies were included (qualitative, quantitative, interventional) as well as reviews of studies and editorials. 2006 was the cutoff point for articles as some countries with the largest Roma populations, joined the EU around this time.

2.4. Data charting

Relevant studies were identified in the database search and duplicate articles removed before beginning the eligibility screening using Rayyan, a web-based tool that supports the process of screening and selecting studies.

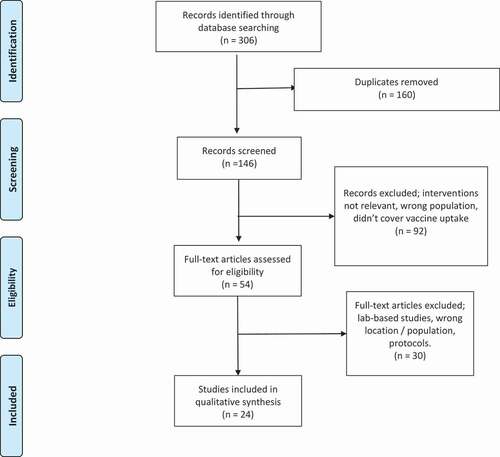

Two researchers completed the title screening followed by an abstract screening using the inclusion and exclusion criteria, identifying 54 articles covering aspects of Roma health, in particular vaccination/immunization for full text review. All 54 articles were fully reviewed, and data charting is attached as Appendix 3. Thirty articles were subsequently excluded as the studies were lab-based, in the wrong location or researched the wrong population or were protocols. Both authors discussed all articles removed and following the full article review, 24 studies were included in the final stage as they provided relevant data for the research question.

2.5. Collating results

Data extracted from each study was collated into key themes and main findings and the root cause was categorized using the 5 A’s taxonomy. In 2016, Thompson et al. categorized existing vaccination gap models, and developed the additional model referred to as the 5As – a taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake [Citation19]. This model looks at the root causes of vaccine hesitancy under five dimensions; access, affordability, awareness, acceptance, and activation and has much in common with the other models. There are approximately 10 different models for determining vaccine hesitancy including Thomson’s Taxonomy, as well as the 3Cs developed by the SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy; complacency, confidence, and convenience (MacDonald et al. 2015); an extension of the 3Cs to 4Cs (calculation being the additional C); parental attitudes to childhood vaccination and vaccine indexes measuring confidence and acceptance, and so on.

To ensure the review is as explicit as possible and provides a wide scope for understanding, the authors chose the 5 A’s model to categorize the identified and perceived barriers as set out in .

Table 1. Thomson’s 5 A’s taxonomy of the determinants of vaccine uptake.

3. Results

The full study selection process is represented in the PRISMA flow diagram, presented in .

A critical appraisal of the final 24 included articles is attached below in , and whilst not a necessary component of a scoping review [Citation17], it can be identified as a limitation of scoping reviews not to reference the quality of the included articles. The overwhelming majority of articles were found to be rigorous and credible in their examination of the stated research topic.

Table 2. Critical appraisal checklist2.

The country setting featured most is the UK (eight studies, 33%), followed by European-based studies (five studies, 21%), Greece (three studies, 12.5%), and the remaining studies are based in Serbia, Slovakia, Italy, Poland, Hungary, Albania, and Bulgaria. This review includes 11 quantitative studies, 7 qualitative studies, two systematic reviews, two descriptive analyses and two mixed-methods studies. A full set of study variables are set out in . Each study is given an ID number 1–24 and identified in the framework below via that number.

Table 3. List of included studies.

Identified themes

The 24 studies were categorized under the 5 A’s framework: access/affordability/awareness/acceptance or activation or any combination of all five. Some of the themes were separated into sub-themes, presented in the thematic framework below. For example, the access barrier ‘mobility’ was referenced in study 2, 10, 11, 13, and 16 (using the study ID number assigned in ).

The thematic framework is sent out in .

Table 4. Thematic framework.

4. Discussion

Studies that discussed access are divided into three interrelated sub-themes: health system issues, socioeconomic conditions, and mobility. Studies that referenced affordability barriers are categorized further through out-of-pocket expenses and opportunity costs. Awareness factors are categorized into vaccine knowledge and service engagement and information themes. Acceptance barriers include lack of trust in the health system/healthcare staff and reliance on informal knowledge or misinformation and activation factors referred mostly to lack of means of positive reinforcement within the Roma community. The prevalence of each identified barrier and comparable findings from each study are discussed below.

4.1. Access factors

Access factors had the greatest number of references within the studies and were considered the most relevant in terms of increasing vaccination uptake [Citation20]. Some studies discussed all three access sub-themes (health system issues, socioeconomic conditions, and mobility) and consequently access barriers are referenced 29 times across the 24 studies.

4.1.1. Health system issues

Of the three sub-themes, the barrier cited the most is health system issues, characterized by staffing issues such as unsatisfactory General Practitioner (GP) and heath care worker (HCW) communication; experience of discrimination at point of contact; lack of culturally aware or trained staff, linguistics, and translation services; data collection issues such as a lack of information systems, ethnic identifiers in data collection, and surveillance; and resource issues resulting in funding constraints and cuts to services in some instances [Citation21].

Further access barriers including communication and the resistance of some GPs to register Roma communities or visit GRT sites were highlighted by Dar in a survey that mapped primary care trusts in the UK and their engagement with GRT groups and immunization uptake [Citation22]. In her discussion of the risks posed to Roma children due to their probability of being vaccinated at 55–60% that of a non-Roma child, Duval references the lack of data on Roma health-seeking behaviors and explains that low vaccine uptake cannot simply be a result of socio-economic conditions [Citation11].

Additional access issues include poor surveillance of vaccination dosage patterns and new case detection (Hepatitis B) as identified in the Albanian study of 174 Roma where the researcher found health inequalities among Roma were consistently unexamined and unattended to [Citation23]. Bell extends this point suggesting that agreed financing and roles and responsibilities must be in place to respond appropriately to outbreaks and support vaccination uptake [Citation21]. Lack of records on Roma settlements in Greece was identified as obstacles for creating sampling frames and preventing better scientific examination of the issue [Citation8]. National estimates on specific Roma uptake of vaccination programs are vital to develop evidence-based programs and prevent the disproportionate effect of funding cuts on vulnerable populations like Roma [Citation8]. A lack of relevant Roma-specific data was highlighted in many studies across a number of countries [Citation24–26].

In Bell’s UK study on measles outbreaks, she found that in general practice, immunization target payments are issued on outcomes and not process and therefore emphasis remains on members of the general population rather than vulnerable groups that require assistance to access immunizations [Citation21]. This study also references cuts to community health services in the UK including district immunization coordinators, which have led to diminished surveillance of immunization uptake in marginalized populations.

In terms of staff training, Muscat identifies that strategies to improve vaccination uptake require different approaches depending on the community and that the involvement of sociologists, anthropologists, and health communization experts may improve healthcare workers understanding of the structural barriers Roma face and how this impacts their health-seeking behaviors [Citation27]. The third phase of the Uniting study looked at potential interventions to increase vaccination uptake including; cultural competency training for HCWs; ethnic identifiers in health records; a named frontline person in GP practices to provide respectful and supportive services; flexible and diverse booking, recall, and reminder systems; and the ring-fencing of funding for specialist HCW posts specializing in GRT health inclusion immunization [Citation26]. Cultural competency training for healthcare workers was a key intervention identified by Dyson to improve standards and relationships with GRT groups. One of the interesting findings of the mapping survey in the UK was the identification of one local authority in the UK that employs two members of the GRT community as health trainers to mediate service delivery between the local authority and the Roma community [Citation22].

Smith and Newton cite the perception by some GRT women that their health is afforded a lower priority that can lead to disengagement with the vaccine program and an aversion to using health services [Citation28]. These women also reported experiencing discrimination and exclusion regularly, resulting in them treating healthcare professionals with suspicion and relying on alternative sources of information. Another UK study that looked at measles outbreaks in the Thames Valley found that fear of hostility or discrimination from HCWs including being refused access to GP surgeries by receptionists contribute to GRT hesitancy in accessing health care [Citation25]. This study also highlighted the need for robust data collection and targeted mediations and advancements in health equity. This finding was shared by Bell, who identified GP registration and discrimination by receptionists in GP practices, as a barrier to vaccination uptake [Citation21]. In a European context, many Roma have reported regular discrimination and exclusion within healthcare settings, generating hostility and suspicion toward HCWs as well as discouraging the use of health services in general [Citation29]. In Fournet’s systematic review of 61 articles, specifically with reference to Roma, she extended the argument that the description ‘hard to reach’ must be abandoned as a descriptive term, replaced by a focus on the scientific reasons and scientific approaches required to address vaccination uptake for different Roma communities [Citation20]. Fournet found that stigmatization, discrimination, and marginalization within health services were all experienced regularly by Roma across Europe.

Translation services and their importance have been expressed in a number of studies including two in the UK. The first study met with a number of immigrant groups, all of whom had appropriate translations services, except Roma who had to rely on a Romanian translator as Romani translation services could not be sourced [Citation30]. The second study that looked at factors influencing vaccination uptake in Roma communities in three cities identified the lack of appropriate translation services as a ‘major barrier’ [Citation21]. This study also contends that suboptimal immunization is due to discrimination experienced by Roma (and Romanian immigrants) rather than hesitancy.

An improvement in health service accessibility overall was deemed essential to engagement with Roma communities in the Slovakian study that examined a measles outbreak in Kosice in 2018 [Citation24].

4.1.2. Socioeconomic conditions

Socioeconomic conditions (including sub-standard housing, lack of employment, poverty, education) are reported as significant factors in vaccination uptake across 12 countries in the EU [Citation20], highlighting an accumulation of health inequalities in different elements of the chain that leads to disease. Socioeconomic conditions are the most significant predictors of the Hepatitis A virus in Slovakia and Greece, countries with some of the highest concentration of Roma across Europe [Citation31]. Several hepatitis A (HAV) outbreaks were recorded over the last 15 years, even though vaccination coverage is considered universal, leading the authors to identify poor housing and lack of sanitation as significant in the spread of infection [Citation32]. Improving living standards of Roma was seen as a key variable in improving vaccine uptake in Greek assessments of universal immunization for HAV and also a cost-effective measure in comparison to the introduction of universal immunization for Hepatitis A, which has proven cost-prohibitive in Greece [Citation32,Citation33]. The Italian study that looked at low vaccination rates among Roma (and other minorities) identified that of the 1,310 immigrant children involved, in 25% of cases children had no access to running water, impacting personal hygiene, food preparation, and overall health due to the prevalence of skin infections and fecal-orally transmitted diseases [Citation34]. The Hungarian study found that the most likely cause of the high rates of HAV within their study cohort was as a result of unhygienic living conditions coupled in some cases, with contaminated drug paraphernalia [Citation35]. These studies identify a clear link between increased exposure to disease and poor housing and sanitation.

A core theme found in the Smith and Newton study was the incongruity between the conditions in which many Roma members live and vaccination uptake. Structural constraints such as access to housing, gender roles within the family, and suspicion of healthcare professionals impact far more on immunization behavior due to competing interests of the primary needs of the family and preventative health care [Citation28]. Improving the living conditions of Roma was considered a vital component in decreasing further HAV outbreaks in Greece [Citation33].

The relationship between better housing, electricity, sanitation, and adequate sewerage systems was associated with positive engagement with vaccination programs in one of the three Greek studies [Citation32]. Papamichail et al. found that proximity to a health center resulted in higher vaccination uptake as did delivery of the vaccination program on site by a primary care practitioner rather than having to attend a hospital [Citation8].

Examination of low vaccination coverage in a Roma settlement in Belgrade found that children that lived in settlements where waste collection provided the main source of income were more inclined to experience higher levels of social exclusion and low levels of engagement with HCWs and in terms of healthcare delivery, were considered invisible to the state [Citation36].

4.1.3. Mobility

Low vaccination uptake among Roma can be due to high spatial mobility of some members [Citation20], living far from a health center and not having transport access, as well as practical factors largely associated with transiency and moving from one local authority area to another [Citation29,Citation33]. Transport inaccessibility and the availability of one car, which in many instances is prioritized for the male going to work, were identified by Smith and Newton as a barrier. This qualitative study, informed through different focus groups in the UK, cited the design of the healthcare system as the main barrier due to its unsuitability and inaccessibility for nomadic families that travel and are asked to leave areas frequently. As a result of forced movement or a desire to remain nomadic, many Roma families do not have a permanent address, excluding them from primary care services or registering with a GP [Citation28]. Adequate staffing of healthcare services in close proximity to Roma settlements is a crucial part of public health inclusion policies [Citation8].

4.2. Affordability factors

Affordability barriers were mainly examined and/or discussed in terms of out-of-pocket expenses and opportunity costs.

4.2.1. Out-of-pocket expenses

Instances where Roma must pay to receive health care arise when they are not registered or cannot present identification [Citation27]. In Albania, whilst access to health care is considered free, citizens must pay health insurance that is seen as a barrier for many Roma [Citation23]. In Bulgaria, almost 95% of Roma children had not received full measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination throughout their childhood, even though children are entitled to a basic benefit package of medical services free of charge [Citation37]. Co-payments for medical services for adults and the requirement of a GP referral, without which a payment is necessary, are affordability factors that impact Roma considerably. In a Polish immunization campaign in 2009, participation hinged on whether participants were registered in the municipality, affecting the numbers that could take part [Citation24]. This study found that a considerable proportion of Roma are not officially registered and therefore have very limited access to health care in the country [Citation38]. In Serbia, risk factors for low-vaccination coverage include the requirement for registration and a health insurance card, identified through the country’s first Roma Health and Nutrition Survey carried out in 2009. Infants born in Serbia are administered the Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination before leaving hospital, however there is a small fee that must be paid upon discharge. This survey found that many Roma infants are not registered as having BCG as their parents leave before paying the fee, therefore the infants remain unvaccinated as far as the state is concerned [Citation36].

In a UK study that looked at parents experiences of child health services, researchers heard from Roma parents that immigrated to the UK from Romania, of situations where they had to pay upfront for their children’s medical care in Romania, in some cases having to bribe hospital staff, even in very serious situations where they felt their child could die. One woman compared her experience of the Romanian and UK health services as like the ‘differences between the earth and the sky’ [Citation30].

4.2.2. Opportunity costs

Opportunity costs refer to situations where parents may have to choose between income-generating activity and paying for health care. In some situations, Roma families have children that may have additional needs, requiring more consistent care that competes with their nomadic culture [Citation39]. In one of the two Serbian studies included, Čvorović found that ‘wanted children’ have higher odds of being fully vaccinated than unwanted children, i.e. there is better parental investment in those children. This study found that whether a child is wanted or not depends on how healthy they are at birth, how many children the family has, and the order in which the child is born; therefore, these specific individual family factors become key variables in the context of immunization status [Citation39].

Bell found that competing priorities were largely as a result of Roma living in ‘day-to-day’ mode, where different stressors arise and must be prioritized on a daily basis. One participant said that vaccination is lower down her list of priorities as she struggles to find food for her children and figure out how her family will survive on any given day [Citation40].

An Italian study recognized the relationship between inequality, socioeconomic conditions, and vaccination uptake and supports efforts by the Italian government to address the competing priorities of Roma immigrants through programs that ensure all immigrant children have a pediatrician, reduced cost baby food and baby hygiene products [Citation34].

4.3. Awareness factors

Vaccine knowledge and poor service engagement/lack of knowledge about services were the two main sub-themes identified as awareness barriers.

4.3.1. Vaccine knowledge

Roma are considered a difficult population to vaccinate due to parental beliefs [Citation33]. However, this assumption is not borne out in all of the studies included in this review. Some of the most common knowledge and information gaps include concerns about the adverse effects of the vaccine, issues with combined vaccines and potential trauma experienced by the child receiving a number of vaccines together [Citation28]. Some Roma believe that vaccines were given too young and that immune systems will mature with age, reducing the need for vaccination [Citation28,Citation29]. There is concern too from parents due to perceived frequent episodes of ill-health of their children and the advantages and disadvantages of receiving a vaccine as perceived by the child’s mother [Citation28]. Therefore, parental beliefs on vaccination can sometimes stem from concern for the child’s overall health.

Access barriers including actual and perceived isolation combined with an information gap (leaflets not accessible or translated) lead to a situation where vaccine knowledge is poor and subsequent informal routes are relied on [Citation28]. Smith and Newton heard from Roma parents that they feel much the same as non-Roma about vaccination – however, fundamental system inequalities and limitations on access produce lower vaccination uptake. This study concluded that beliefs and attitudes are not as relevant as the context in which the decisions are made and the extent to which poor living conditions and the ‘pariah status of GRT groups’ can impact this decision more than cultural beliefs [Citation28].

Maternal education was highlighted as a protective factor for vaccination in the Bulgarian study and for each year of educational attainment, the probability of medical complications for a child (which decrease substantially because of vaccination) decreased by 17% [Citation37].

The 2015 Italian study identified that 77% of parents had never attended school, consequently illiteracy rates were high, which is a widely accepted indicator of absolute poverty and the most important risk factor to consider in promoting preventative health care of which vaccination programs are a key component [Citation34].

Hepatitis A transmission in Greece has been found to be predominant among Roma communities. Mellou et al. recommend that providing appropriate information to young adults on the spread of HAV, focusing on sexual transmission and promoting safer sexual practices should form a key component of any future immunization promotion activities in Greece, which are aimed at deprived groups [Citation32].

A much broader perspective was identified in the first phase of the UK Uniting study – Needles, Jabs and Jags, which found that Roma experience many of the same barriers as other ethnic minority groups but that language and adapting to life in a new country were the primary challenges. Roma expressed positive attitudes about vaccination and were classified as ‘unquestioning acceptors’ in that they are present when the vaccination is due and the parent is positive about vaccination [Citation41,Citation42]. It is worth noting, however, that most of the Roma interviewed as part of the study appeared to have limited knowledge of the reasons for vaccination, what they protect against and the routine involved, with one Roma participant outlining that she had brought her son twice for vaccination, but she did not know what was being said or what he was being vaccinated against [Citation41]. The Uniting study also found that language and literacy barriers are clearly impacting on Roma communities proactively engaging with immunization programs, as the necessary parental information is not translated into Romani in most instances [Citation40].

The main reason given for low vaccination by Duval et al. is that the parent is unaware of the need for immunization coupled with fears around payment [Citation11]. In Fournet’s systematic review of European wide beliefs, Roma groups identified a lack of information on vaccines and a lack of information on the preventative nature of vaccination as a factor in low vaccination uptake [Citation20].

4.3.2. Engagement with and knowledge about services

The main issue in terms of engagement with healthcare settings was the need for outreach supports or mediators that work directly with Roma, targeting their specific healthcare needs. Outreach programs have been proven to be very effective in reaching underserved communities and where funded have been successful in engaging Roma communities, i.e. drop-in centers, pop-up clinics, out of hour appointments, etc. [Citation26]. In the Smith and Newton study, Roma suggested that outreach supports are now less than what they were when they were children [Citation28].

The absence of health professionals visiting and working in Roma settlements was identified as a barrier to higher levels of immunization in the UK [Citation25] as well as providing a continuity of care and appropriate disease surveillance for this community.

In Bulgaria, the abolishment of community health centers was seen to have impacted greatly on those communities that had existing health equity issues due to lack of health insurance, introduction of co-payments, and so on. The move to redirect immunization programs via GP services was considered to have impacted negatively on disadvantaged communities such as Roma [Citation37].

The highest vaccination coverage among Roma children born in Serbia is the initial vaccination given at birth – BCG and Hep B. Researchers have linked this to the fact that Roma do not have to seek out this immunization as it is given as a matter of course before mother and baby leave the hospital. Also, when programs are directly aimed at Roma, facilitate ease of access for Roma and are delivered in settlements, positive outcomes are seen. Many of these programs are delivered in tandem with humanitarian aid in an effort to engage the community to the greatest extent [Citation39].

Having a vaccination document was considered a positive variable in terms of ongoing engagement with a vaccination program in the Greek national survey on Roma children’s experience of vaccination. More than 8/10 children had their health booklet, demonstrating that vaccination was important to these families but possibly not always accessible due to socioeconomic factors [Citation8]. This Greek study also found that services provided close to where Roma live, designed to meet specific Roma needs and adequately staffed, contributed positively to enhanced vaccination uptake by the Roma community.

4.4. Acceptance factors

Lack of trust and reliance on informal advice/misinformation were the main acceptance barriers.

4.4.1. Lack of trust

In their analysis of the prevalence of measles in the Thames Valley over 4 years, researchers found that the main reason those affected did not seek medical advice from their GP, was due to a perception that the GP would not visit their settlement, would not listen to them or in some instances, did not know how to treat measles [Citation25]. In contrast, outreach workers that deliver tailored health services to Roma were considered a key component of the UK response to reaching Roma communities [Citation26].

The Dyson study put forward a recommendation for ‘vaccine advocates’ – a community champion, from within the Roma community that could promote vaccination as a positive health approach [Citation26]. The introduction of Roma health mediators in Serbia has a similar role in place to ensure better health equity for Roma communities as a result of vaccination rates continuing to remain far below the WHO targets for the Roma population in different parts of the country [Citation36].

A lack of trust in the healthcare system was largely due to past experiences with HCWs and in some instances, led to fear and distrust. The Uniting study identified that, in order to counter the mistrust that can exist in some Roma communities, HCWs must consider the context in which Roma live and how fear can impact on decisions around immunization. This can be further exasperated by language difficulties and not understanding why a child should be included in a vaccination program [Citation40].

4.4.2. Misinformation

In the UK study that surveyed Roma from three cities, beliefs that measles can be a ‘rite of passage’ or contracting measles leads to natural immunity were found to be prevalent [Citation40]. This study also found that when information leaflets on vaccination programs are not available to Roma, Roma rely on informal means of information through family and friends and social media, YouTube, and so on, which can often contribute to an internalized anti-vaccine belief. Improving the quality of information to the public and health professionals therefore needs to involve the media and social media as the internet is considered a powerful tool to deliver quality and factual health-related information [Citation27].

4.5. Activation factors

The main activation factor was the use of positive reinforcement to remind or prompt isolated communities to engage with vaccination programs.

4.5.1. Positive reinforcement

Positive reinforcement is the main theme of vaccine activation – whereby target groups of marginalized populations are reminded and prompted to attend and take part in vaccine programs. Reminders and accessible messaging are important in delivering targeted approaches to Roma communities that are socially isolated from the general community [Citation41]. The Uniting study demonstrated the need for flexible and diverse booking systems, recall facilities and reminders, and made accessible messaging one of the five key recommendations of the study [Citation26]. A flexible approach was seen as key and the issuing of appointments within 1–2 days rather 2–3 weeks was considered to lead to better success. Letter and text message were not considered very effective in reaching Roma as per the Bell study, where participants stated that they preferred face-to-face communication as a mechanism for building trust in the communities. The benefit of having a flexible approach when trying to increase vaccination uptake, i.e. if a child presents in general practice for a non-vaccination related concern and vaccination is offered, was also considered a key means of countering activation barriers [Citation40].

Messaging and the means by which public health information is highlighted were seen as an important component of any vaccination program. Fear-based advertising is not as successful as messaging that promotes the benefits of vaccination and disputes vaccination myths [Citation20]. In contrast, a campaign based on addressing why people are opposed to vaccination and their responsibility to the wider community was suggested in the Slovakian analysis [Citation24].

The use of the voluntary sector in engaging Roma communities is an under-utilized resource that could provide better immunization promotion and roll-out if used more widely across the UK [Citation22]. This was also a finding of the study in Belgrade where the sample size and response rate of Roma members was enhanced by having a Roma NGO administer the survey [Citation36].

5. Conclusion

This scoping review has provided a broad comparative overview of the factors and barriers that lead to vaccine hesitancy within European Roma communities and suggested potential measures (identified by Roma people, healthcare professionals, and NGOs working with GRT groups) that could be taken to improve these rates, some of which are referred to below.

5.1. Structural recommendations

Whilst a small but growing body of work refers to the notion of measuring and examining Roma health, one must use observed caution when analyzing this large heterogeneous and diverse population and using labels such as ‘under-served’ or ‘hard to reach’ community [Citation28,Citation43]. Whilst it may be true that Roma populations experience significant discrimination, these terms can inadvertently contribute to the ‘othering’ of Roma people and more broadly the stereotypical approach that cultural or ethnic difference is a health problem. Ignoring differences within population groups such as Roma can further exacerbate the issue of low vaccine uptake, as new generations of Roma have identified that vaccination decisions based on previous family experiences (often included as a cultural barrier) do not represent their experiences [Citation41]. This can provide an easy means of explaining a much more complex issue that recent UK-based research identifies as being more influenced by socio-economic and socio-cultural barriers such as poverty, early school leaving, inadequate housing, and exclusion, leading to a mistrust of healthcare providers [Citation26]. It is also important to show positive portrayals of Roma in our media, health campaigns, and health literature and ensure that point-of-entry contact is respectful and psychologically informed [Citation41].

It is common across the majority of UK studies in particular that investment in resources both human and capital is an important consideration for effective vaccination programs, targeting Roma communities. Roma link workers who co-produce the delivery of vaccine and other preventative health programs and are involved in planning the roll-out and capture of data have been identified by service providers and Roma members as vital in ensuring positive outcomes. Where these roles have been introduced and subsequently reduced due to funding cuts and the redeployment of resources, negative outcomes have been highlighted [Citation22] [Citation26,Citation37,Citation44].

5.2. Research recommendations

Efforts to ensure better Roma health, and in particular preventative health such as immunization programs, may benefit from using the social ecological model to design and implement supports that aim to improve vaccine uptake or an appropriate response to the outbreak of any communicable disease [Citation45]. The social ecological model identifies individual factors as well as institutional, structural, and environmental influences that contribute to a broader, more intersectional approach to vaccination uptake within Roma communities.

Further analysis is required to consider a key question: can a community that in many contexts experiences such acute poverty and deprivation engage positively in vaccination programs when their primary needs such as access to water and shelter remain unmet? There is a pressing need to further examine and address the social determinants of health for Roma in individual countries and the congruent intersection with vaccine uptake.

Intersectionality theory as framed by Crenshaw is both a valuable model and tool for examining the unmet health needs of Roma and structural barriers such as race, gender, as well as poverty, low income, and poor educational attainment [Citation46]. Looking at how these factors overlap and potentially shape responses in a way that does not validate discrimination or contribute to a power imbalance, would be a powerful approach. Interestingly, Papamichail found that gender disparity had a negative association with continued engagement with vaccination services in Greece [Citation8]. Čvorović found in her analysis of 584 children aged 0–24 months in Serbia that boys were more wanted than girls and therefore girls were less likely to receive immunization as child wantedness and immunization are inter-related [Citation39].

5.3. Policy recommendations

Where subpopulations with low immunization levels exist, as is the case in some Roma communities, these isolated communities will continue to be vulnerable to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, increasing the risk of disease in their own communities as well as the whole community as some of these diseases are highly communicable [Citation47]. There is an urgent need to develop, strengthen, and scale-up vaccine delivery platforms across the EU that are accessible and acceptable to Roma and other marginalized populations that have suboptimal vaccination uptake, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. As pointed out by Wicker and Maltezou, there is an urgent need to establish or expand existing vaccination programs to social excluded groups including the homeless, migrants, Roma, and other communities often unheard [Citation48]. These programs must be cognizant of the indirect ways in which preexisting programs exclude Roma through out-of-pocket expenses, need for registration or ID, lack of translated material in the Romani language, and the lack of appropriate literature, and so on. Many voluntary bodies that work with Roma highlight the need for culture brokers or Roma members that can be employed as co-producers of locally delivered healthcare programs and the likely success that derives from an asset-based human rights approach.

Finally, health services are asked to consider the collection of disaggregated data on the basis of ethnicity and within a human rights framework. The use of ethnic identifiers in data collection has been highlighted as a deficit in some vaccination programs included in this study and evidence on Roma health overall. As Dyson points out, however, a sensitive approach is necessary as many may have fears of prejudice if identifying as a member of the Roma community [Citation26].

6. Expert opinion

Notwithstanding the very fluid nature of Roma ethnicity, very little research exists around vaccine hesitancy within these communities, even though Roma communities are some of the hardest hit by outbreaks of communicable disease. The risk of measles within GRT communities has been reported by one study as 100 times higher than in the general population. Limited evidence exists on interventions that are aimed at improving vaccination rates among Roma populations and consequently there is a public health ‘urgency’ to develop evaluated approaches of the same. In the context of COVID-19 and perceived increases in vaccine hesitancy within migrant and ethnic minorities, and the impact of low vaccination rates within this vulnerable group, this urgency is exacerbated.

Ongoing analysis of vaccine hesitancy within underserved and marginalized communities is vital in understanding the knowledge levels, attitudes, and beliefs many of these groups have toward immunization programs, in particular the global COVID-19 vaccination program and what measures can be adopted to improve high hesitancy rates. Notwithstanding the fact that vaccine equity remains a significant factor in overall levels of coverage within disadvantaged populations, hesitancy is a considerable factor that continues to challenge efforts to eradicate diseases such as those mentioned in this review (measles, hepatitis, other childhood illness) and new and evolving disease such as SARS-CoV-2 and any new developing strains.

Coupled with the evidence that Roma experience low-quality health care in many instances stemming from their living conditions, the Roma community face ongoing challenges in health protection terms. Key areas for improvement include ongoing analysis of populations that live in circumstances well below what is considered healthy and viable for good standards of living. As is often the case, good-quality housing is the medicine for many illnesses and diseases and in the context of COVID-19 and living through a pandemic, this analogy could be extended to ‘spread of disease.’ Future research must consider the views and lived experiences of Roma communities during and after the pandemic and how necessary government restrictions have potentially altered trust in state services such as health care and more importantly for this study, preventative health care The evidence tells us that the levels of racism and discrimination experienced by Roma have increased in the last 2 years, leading to increased hardship and marginalization. To combat precarious health beliefs rooted in lived-experience as well as inherited generational experience, ongoing research is needed to analyze current health beliefs and health literacy levels within Roma communities. This scoping review suggests potential ways of mediating with ‘hard-to-reach’ Roma communities, identified by successful research studies undertaken across Europe, in the last 15 years.

However, without tackling the structural barriers to social inclusion experienced by Roma and other ethnic-minorities across Europe, approaches to tackling health beliefs and health equity are weakened and, in some cases, could be considered tokenistic. Critical analysis of health outcomes from interventions should form part of an ongoing research enquiry. The adoption of the EU Framework for National Roma Integration in 2011 required all member states to adopt national strategies for Roma integration in health, housing, education, and employment. Consequently, a number of studies were undertaken in different countries and recommendations published on required measures. Yet more than 10 years later, the evidence in terms of health promotion efforts such as vaccination as well as overall increases in anti-Roma sentiment (anti-Gypsyism) indicates that some efforts have had minimal impact.

Universal access to health care a priority of the WHO and as such access to preventative, treatment, rehabilitative, and palliative care globally. However, efforts to achieve this goal require wide-ranging examination of the considerable barriers (structural, economic, cognitive, and psychosocial) to accessing health care, when care is needed. Access barriers identified at the health system level as well as at the individual level should be prioritized to deliver accessible, responsive services to communities not often heard.

Article highlights

Roma communities across Europe remain some of the most marginalized populations very often living in substandard housing and unable to access adequate sanitation, employment, education, and health services. The COVID-19 pandemic has made life for Roma populations, many of whom are nomadic and dependent on a wide family network, harder than ever before.

This scoping review considers the factors that affect routine vaccination for Roma communities (childhood vaccinations, measles, hepatitis), in the knowledge that these factors are likely to impact on Roma uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine. Anecdotal evidence suggests increasing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy within migrant populations, and it is imperative that researchers and health system professionals understand existing barriers to vaccine uptake within this population.

The variety of studies included in this evidence synthesis present a wide scale of barriers, however access to vaccines is the most prominent. Using Thomson’s Taxonomy of Vaccine Hesitancy, access is defined as ‘the ability of individuals to be reached, or to reach, recommended vaccines.’ This review highlights that for many Roma, issues such as transport, communication difficulties, living far away from health centers, lack of ethnically identified data collection, previous experience of healthcare staff, and lack of cultural competencies among health staff contribute significantly to sub-optimal levels of routine vaccination.

Recommendations from this review suggest that in order to tackle routine vaccine hesitancy within populations such as Roma and to prepare for higher uptake of the COVID-19 vaccination program, barriers such as access (as well as affordability, awareness, acceptance, and activation) must be understood and given due regard.

This scoping review is the first part of a wider piece of qualitative research looking at improving suboptimal COVID-19 vaccination rates in Roma communities in Ireland.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the MSc in Public Health Department in the Faculty of Education and Health Sciences in the University of Limerick.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Joanna Briggs Institute 2017. EU refers to the European Union.

References

- Hajioff S, McKee M. The health of the Roma people: a review of the published literature. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54(11):864–869.

- Council of Europe. Dosta! Go beyond prejudice, meet Roma, gypsies and travellers!. 2014. Available from: https://www.coe.int/en/web/roma-and-travellers/dosta-in-the-united-kingdom

- McFadden A, Siebelt L, and Gavine A, et al. Gypsy, Roma and traveller access to and engagement with health services: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2018;28(1):74–81.

- The European Commission. A union of equality: EU Roma strategic framework for equality, inclusion and participation [ Online]. Brussels; 2020. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0620

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Second European Union minorities and discrimination survey. (EU-Midis II). Roma - selected findings. 2018.

- Matache M, and Bhabha J. Anti-Roma racism is spiraling during COVID-19 pandemic the mayor of Kosice in Slovakia. Health Hum Rights. 2020;22(1):379. [ Online]. Online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/commissioner/-/

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Coronavirus pandemic in the EU - impact on Roma and Travellers (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.). no. March 2020.

- Papamichail D, Petraki I, Arkoudis C, et al. Low vaccination coverage of Greek Roma children amid economic crisis: national survey using stratified cluster sampling. Eur J Public Health. 2017;Apr;27(2):318–324.

- European Commission. Health status of the Roma population data collection in the member states of the European Union executive summary. 2014. DOI:10.2772/31384

- Cook B, Ferris Wayne G, Valentine A, et al. Revisiting the evidence on health and health care disparities among the Roma: a systematic review 2003-2012. Ó Swiss Sch Public Health. 2013. DOI:10.1007/s00038-013-0518-6

- Duval L, Wolff F-C, and Mckee M, et al. The Roma vaccination gap: evidence from twelve countries in Central and South-East Europe. Vaccine. 2016;34(46):5524–5530.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Review of outbreaks and barriers to MMR vaccination coverage among hard-to-reach populations in Europe. no September. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); 2013.

- MacDonald NE, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4164.

- WHO. Ten threats to global health in 2019. Geneva: WHO; 2019.

- SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Report of the Sage working group on vaccine hesitancy. no. October. 2014:, p. 64. [ Online]. Available from: https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/1_Report_WORKING_GROUP_vaccine_hesitancy_final.pdf

- Oduwole EO, Pienaar ED, Mahomed H, et al. Current tools available for investigating vaccine hesitancy: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e033245.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

- Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–2126.

- Thomson A, Robinson K, and Vallée-tourangeau G. The 5As: a practical taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine. 2016;34(8):1018–1024.

- Fournet N, Mollema L, Ruijs WL, et al. Under-vaccinated groups in Europe and their beliefs, attitudes and reasons for non-vaccination; two systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2018 Jan;18(1):196.

- Bell S, Saliba V, and Evans G, et al. Responding to measles outbreaks in underserved Roma and Romanian populations in England : the critical role of community understanding and engagement. Epidemiol Infect. 2021;148(e138):1–8.

- Dar O, Gobin M, Hogarth S, et al. Mapping the Gypsy traveller community in England: what we know about their health service provision and childhood immunization uptake. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2013 Sep;35(3):404–412.

- Kureta E, Basho M, Murati E, et al. Screening for viral hepatitis b in the Roma community in Tirana, Albania. South East Eur J Public Health. 2019;12:1–8.

- Hudečková H, Stašková J, Mikas J, et al. Measles outbreak in a Roma community in the eastern region of Slovakia, May to October 2018. Zdr Varst. 2020 Oct;59(4):219–226.

- Maduma-Butshe A, McCarthy N. The burden and impact of measles among the Gypsy-Traveller communities, Thames Valley, 2006-09. J Public Health (Oxford). 2013 Mar;35(1):27–31.

- Dyson L, Bedford H, Condon L, et al. Identifying interventions with Gypsies, Roma and travellers to promote immunisation uptake: methodological approach and findings. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1574). DOI:10.1186/s12889-020-09614-4

- Muscat M. Who gets measles in Europe? J Infect Dis. 2011;204(SUPPL. 1):S353–S365.

- Smith D, Newton P. Structural barriers to measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) immunisation uptake in Gypsy, Roma and traveller communities in the United Kingdom. Crit Public Health. 2017 Apr;27(2):238–247.

- Wilder-Smith AB, Qureshi K. Resurgence of measles in Europe: a systematic review on parental attitudes and beliefs of measles vaccine. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020 Mar;10(1):46–58.

- Condon L, McClean S, McRae L. ‘Differences between the earth and the sky’: migrant parents’ experiences of child health services for pre-school children in the UK. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2020;21. DOI:10.1017/S1463423620000213.

- Mrzljak A, Bajkovec L, Vilibic-Cavlek T. Hepatotropic viruses: is Roma population at risk? World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(2):143–151.

- Mellou K, Chrysostomou A, Sideroglou T, et al. Epidemiology of hepatitis A in Greece in the last decade: management of reported cases and outbreaks and lessons learned. Epidemiol Infect. 2020Feb;148:e58.

- Papaevangelou V, Alexopoulou Z, Hadjichristodoulou C, et al. Time trends in pediatric hospitalizations for hepatitis A in Greece (1999-2013): assessment of the impact of universal infant immunization in 2008. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016 Jul;12(7):1852–1856.

- Ercoli L, Iacovone G, De Luca S, et al. Unequal access, low vaccination coverage, growth retardation rates among immigrants children in Italy exacerbated in Roma immigrants. Minerva Pediatr. 2015 Feb;67(1):11–18. [ Online]. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=24942241&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Gyarmathy VA, Ujhelyi E, Neaigus A. HIV and selected blood-borne and sexually transmitted infections in a predominantly Roma (Gypsy) neighbourhood in Budapest, Hungary: a rapid assessment. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2008;16(3):124–127.

- Stojanovski K, McWeeney G, Emiroglu N, et al. Risk factors for low vaccination coverage among Roma children in disadvantaged settlements in Belgrade, Serbia. Vaccine. 2012 Aug;30(37):5459–5463.

- Lim T-A, Marinova L, Kojouharova M, et al. Measles outbreak in Bulgaria: poor maternal educational attainment as a risk factor for medical complications. Eur J Public Health. 2013 Aug;23(4):663–669.

- Stefanoff P, Orlikova H, Rogalska J, et al. Mass immunisation campaign in a Roma settled community created an opportunity to estimate its size and measles vaccination uptake, Poland, 2009. Euro Surveill Bull Eur Sur Les Mal Transm = Eur Commun Dis Bull. 2010 Apr;15(17). DOI:10.2807/ese.15.17.19552-en

- Čvorović J. Child wantedness and low weight at birth: differential parental investment among roma. Behav Sci (Basel). 2020;10(6). DOI:10.3390/BS10060102

- Bell S, Saliba V, and Ramsay M, et al. What have we learnt from measles outbreaks in 3 English cities? A qualitative exploration of factors influencing vaccination uptake in Romanian and Roma Romanian communities. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–10.

- Jackson C, Bedford H, Cheater FM, et al. Needles, Jabs and Jags: a qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitators to child and adult immunisation uptake among gypsies, travellers and Roma. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(254). DOI:10.1186/s12889-017-4178-y

- Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, et al. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12(1). DOI:10.1186/1471-2431-12-154

- Orton L, Anderson de Cuevas R, Stojanovski K, et al. Roma populations and health inequalities: a new perspective. Int J Hum Rights Healthcare. 2019;12(5):319–327.

- Bell S, Saliba V, Evans G, et al. Responding to measles outbreaks in underserved Roma and Romanian populations in England: the critical role of community understanding and engagement. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148. doi:10.1017/S0950268820000874.

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Collins KMT, Frels RK. Foreword: using Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory to frame quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research. Int J Mult Res Approaches. 2013;7(1):2–8.

- Crenshaw K; Stanford Law Review. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence ag.Stanford Law Rev. 2016;43(6):1241–1299.

- Haverkate M, D’ancona F, and Johansen K, et al. Assessing vaccination coverage in the European Union: is it still a challenge? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;10(8):1195–1205.

- Wicker S, and Maltezou HC. Vaccine-preventable diseases in Europe: where do we stand? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13(8):979–987.