ABSTRACT

Certain kinds of death that have been touristified and packaged as commodities have been referred to as 'dark tourism'. It is here where tragic memories are retailed as kitsch mementos in a society of the spectacle. Whilst death has long been an article of trade, commodification within dark tourism, including kitschification and semiotic appropriation of icons, and its interrelationship with placemaking has been overlooked in the literature. The purpose of our paper, therefore, is to outline the spectacle of atrocity and, in so doing, explore commercialisation of the dead within visitor economies. Drawing upon notions of commodification, placemaking, kitschification and semiotics, we construct an original conceptual model in order to lay a scholarly route map for future empirical research. To provide specific contextualisation, we offer a mini-case study from the 2017 terrorist attack at the Ariana Grande concert and its subsequent ‘tragic placemaking’ of Manchester, UK. Ultimately, we lay down theoretical foundations upon which future dark tourism commodification and placemaking studies can be located, augmented, and empirically explored.

… no one is actually dead until the ripples they cause in the world die away. (Terry Pratchett, Citation1991)

Introduction

Death has long been an article of ritual and trade. We live in a dominion of the Other dead. Even in a COVID-19 world, at the time of writing, the coronavirus pandemic that enveloped the globe, death appears as a fearful statistic in politicians’ daily addresses and media schematics. Indeed, COVID-19 has brought the Grim Reaper into closer view for many. Even so, the obscurity of (Western-secular) dying means that death is often planned for, insured against, purchased, and experienced through a modern death, dying and disposal industry (Walter, Citation2020). Of course, while the professionalisation of death and dying describes processes that deal with ‘ordinary death’ (see Walter, Citation2020) – that is, mortality of the masses – the ‘significant Other dead’ ushers a new kind of ‘spectacular death’ mentality (after Jacobsen, Citation2016). In other words, the significant Other dead might be described as those who perish in brutal, accidental, or calamitous circumstances, and who continue to affect the living. These types of deaths have become commodities of consumption and for mercantile memorialisation (Stone, Citation2012a).

Therefore, we often consume death of the Other that has perturbed our collective consciousness, either through the media or heritage. In turn, certain kinds of death, such as those which occur in tragic, untimely, violent, or disastrous situations, or en-mass or out of the ordinary, are made spectacular (Jacobsen, Citation2016; Stone, Citation2018). Ultimately, these deaths take on significance for the living and become a spectacle for consumption, remembrance, and experience within visitor economies. Arguably, therefore, our significant Other dead have become a ‘spectacle’ in a symbolised society (Debord, Citation1967/Citation1994; Jacobsen, Citation2016; Stone, Citation2020). Consequently, semiotic and often contested interpretation of significant deaths is represented within global visitor economies. This includes visiting spaces of death and places associated with difficult heritage, otherwise referred to as ‘dark tourism’ (Lennon and Foley, Citation2000; Stone, Citation2006).

Importantly, however, the spectacularization of death within dark tourism has also ushered in death as part of a broader entrepreneurial exercise, where the spectacular dead are ‘packaged’ as commodities and their tragic passing retailed in a mercantile world (Bird, Westcott, & Thiesen, Citation2018; Grebenar, Citation2018; McKenzie, Citation2018). For instance, the tragic dead and their demise are often commercialised through kitsch and standardised tourist mementoes. These include but are not limited to, fridge magnets on sale at Auschwitz-Birkenau showing Nazi death camps, snow globes traded in New York depicting 9/11 at Ground Zero, or replicate toy grenades retailed at the Killing Fields in Cambodia (Sharpley, Citation2009; Sturken, Citation2007). This commercialisation of death, specifically within dark tourism, is a defining feature of ‘spectacular death’ where the Other dead are revived, reinvented, and commodified within the experience economy (Jacobsen, Citation2016; Stone, Citation2017). In so doing, dark tourism helps (re)frame significant deaths as well as places where tragic or notable death has occurred. These places may be defined as contemporary ‘deathscapes’ and, as a result, touristification is making the lines between commemoration and commercialism increasingly blurred (Stone, Citation2020). Moreover, this touristification of deathscapes raises profound notions of placemaking (Relph, Citation1976; Tuan, Citation1977): that is, the idea of adding specific value and connotation to a space in order for it to become a meaningful place. It is within these deathscapes, such as at Ground Zero in New York, the genocide sites of Rwanda, or at Auschwitz-Birkenau, that the dead are remembered (or forgotten) by heritage production and experienced through tourist consumption.

The purpose of our paper, therefore, is to critically examine commodification of death through dark tourism. In particular, we aim to provide an original conceptual blueprint of the commercialisation of significant Other death. Specifically, our paper addresses an issue that that has been overlooked in the literature thus far: namely, how the spectacle of significant death is appropriated and commodified in the ‘making’ of tragic places. Drawing upon broader ideas of commodification, placemaking, kitschification and semiotics, we construct a scholarly route map and sketch a conceptual model. Our goal is to illustrate theoretical foundations where future research avenues in dark tourism scholarship can be located, augmented and, ultimately, empirically examined. To provide some contextualisation to our framework, rather than a full case study approach, we use empirical insights from the atrocity of the 2017 terrorist attack on the Ariana Grande concert and its subsequent ‘tragic placemaking’ of Manchester, UK. Firstly, however, we turn to the process of commodification within dark tourism as bedrock for subsequent discussions.

Commodification, placemaking and dark tourism

Commodification of place and people are an inherent part of the modern tourism industry. As such, touristic encounters are viewed through a commercialised lens, whereby visitors often purchase a touchstone of their tourist experience in the form of cultural mementos (Morgan & Pritchard, Citation2005). However, commodification in tourism is not a straightforward commercial production/consumption binary process. It is a complex, disputed and sometimes byzantine market-place web of adding ‘worth’ to ‘things’ and ‘stuff’ that, in turn, are valued in terms of cost, benefits, opportunities, and experiences. Indeed, Walsh and Giulianotti (Citation2007) note the ‘commodification critique’ – a philosophical approach to the nature of commodified entities including, but not limited to, tourism. Some commentators argue that commodification is regrettable (Elkington, Citation2015) or even inherently bad (Boorstin, Citation1987). While beyond the scope of our paper, much of the commodification critique of tourism focusses on dilution of culture and loss of authenticity, as well as socio-cultural and environmental consequences that stem from the mass mobility of people (Urry, Citation2005). Yet, despite the (temporary) economic rupture of visitor economies caused by COVID-19, few would have predicted how the commodification of travel would evolve into the social, cultural, and economic phenomenon that is contemporary tourism today. Indeed, tourism has become a barometer of individual and national wealth – and, consequently, experiencing tourism is an accepted, expected, and even sought-after form of consumption.

However, hedonic tourism aside, dark tourism raises emotive and provocative issues, not least those that focus on commercial aspects of death, tragedy, and remembrance. Therefore, dark tourism is different from other forms of tourism in that money within the commodification process introduces potential exploitation and ethical dilemmas of (re)presenting the dead (Lennon & Teare, Citation2017; McKenzie, Citation2018; Seaton, Citation2009). In many cases, monetary transactions are at the core of most dark tourism commerce, whether at the world-renowned Body Worlds exhibitions (Bouchard, Citation2010), the so-called dark fun factories of the Dungeon visitor attractions (Stone, Citation2009), or via street-vendors around Ground Zero (Sather-Wagstaff, Citation2011). Even visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum means the site has become entrenched into a broader visitor economy. Indeed, the place that continues to haunt contemporary imaginations relies on tourism infrastructure to maintain (and sell) the memory of the Holocaust dead (Cole, Citation2000).

To that end, the role of money is somewhat paradoxical within dark tourism. On the one hand, monetary exchange denotes exclusivity or power while, on the other hand, it could be perceived as degrading sacred authority that dark tourism sites may possess (Toussaint & Decrop, Citation2013). However, Seaton (Citation2009) considered monetary exchange within dark tourism, including how to implement it sensitively by making voluntary donations rather than charging tickets or fees. Funding issues aside, Grebenar (Citation2018) and Willard, Lade, and Frost (Citation2013) suggest commodified aspects of the tourist experience within dark tourism may even enhance visitor encounters, by offering familiarity and succour in the form of standardised gift shops, hospitality provision, and tour guiding. In turn, some ethical issues associated with commercialising difficult heritage or commodifying the dead are somewhat rendered (Cave & Buda, Citation2018).

Yet, much of the debate focuses on custodianship of dark tourism, and the manner in which neo-liberal marketisation can negatively modify a deathscape through commercial tainting. Seaton (Citation2009) argues that dark tourism is auratic and polysemic and, consequently, commodification can dilute dark tourism by stripping away perceived sacredness or cultural dignity of the dead. Indeed, the process and extent of commodification might be a specific threat to dark tourism sites because commercialism may impair the aura and Otherness of a particular deathscape. In short, dark tourism is inherently prone to commercial exploitation in a post-truth world, as the dead cannot provide sale receipts. Furthermore, polysemy inherent within dark tourism experiences indicates multiple meanings are evident at a single visitor site (Seaton, Citation2009). In other words, a single dark tourism site can invoke many different meanings for many different people. As such, commercialisation of difficult heritage may adulterate or attenuate polysemic meanings, and diminish the auratic nature of the visitor experience.

Importantly however, issues of commodification and tourism in general have been bound up with broader notions of destination ‘placemaking’ (Dupre, Citation2019; Lew, Citation2017). Despite semantics over the terminology, placemaking is how space through the attachment of sacred/secular/spiritual meaning becomes a place (Lew, Citation2017). Placemaking is essentially concerned with how a space is designated with some form of semiotic value and, thus, becomes significant or associated with some form of personal or collective meaning (Cresswell, Citation2015). Until recently, placemaking has been chiefly the concern of the built or natural environment discourse (for instance, Dupre, Citation2019). However, a body of literature is now emerging exploring how tourists perceive and generate a sense of place (Jarratt, Phelan, Wain, & Dale, Citation2018). Much of placemaking within tourism relies on the co-construction of meaning between individual tourist experiences and collective official (re)presentations (Lew, Citation2017). At the heart of this is how commodification and its perceptions are either diluting, altering, or enhancing the overall visitor encounter. Whilst tourism placemaking is receiving increasing scholarly scrutiny, a number of studies have also began to explore placemaking within dark tourism – for example, Wang, Chen, and Xu (Citation2019), Rofe (Citation2013), and White and Frew (Citation2013). Interestingly, Spokes, Denham, and Lehmann (Citation2018) examine dark tourism, memorialisation and ‘deviant spaces’ through the philosophical lens of Henri Lefebvre. Using a scaled approach, they articulate a framework of ‘lived’, ‘perceived’, and ‘conceived’ aspects of dark sites. Similar to Seaton’s (Citation2009) notion of polysemy and multiple meanings within dark tourism, Spokes et al. (Citation2018) unpack the heteroglossic nature of deviant spaces and memorialisation within dark tourism places. It is here that coexistence of meanings makes a single dark tourism site and, in so doing, allows potential representation of multiple voices. Similarly, Wilford (Citation2015) examines the reframing of urban space and cultural identity in post-traumatic places. Wilford (Citation2015) argues the cultural ‘rebooting’ of a place is where terror spectacles are transformed into a utopic state for spectacular tourism consumption (also see Phipps, Citation1999).

Notably, however, placemaking at some dark tourism sites, particularly in the immediate aftermath of a fatality event, suggests meaning making can be far more spontaneous and organic than, say at official and commercialised memorial sites (Lew, Citation2017; Stone, Citation2006). For example, varying narratives of community commemoration at Rwandan genocide sites, or ‘unofficial’ memorial merchandise sold by hawkers near Ground Zero, illustrate social reactions to grief and representations of trauma can be equal to or more powerful than authoritative or ‘official’ responses (Sturken, Citation2007). This extemporaneous ‘bottom-up’ approach to placemaking allows for polysemic interpretations becoming apparent at particular sites, before or during the commodification process (Lew, Citation2017). Moreover, such an approach can also potentially define a ‘dark place’ by developing meaningful and reciprocated relationships between tourists and hosts (Wang et al., Citation2019).

That said, however, reciprocity is not always an outcome, as some tourist experiences are divorced from any sense of place felt by resident populations (Cresswell, Citation2015). For example, so-called grief tourists who visited Soham in Cambridgeshire, UK, in the immediate aftermath of the murders of 10-year-old Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman in 2002, met with resistance from local community leaders (O’Neill, Citation2002). Similarly, tourists to 25 Cromwell Street in Gloucester, UK, during 1995/1996, the site of serial killings by Fred and Rosemary West, drew condemnation from local residents for a perceived lack of respect for the place (Holt & Wilkins, Citation2015). While the trauma of these two particular sites has now largely been obliterated from the physical landscape (after Foote, Citation2003), how the significant Other Dead are ‘sold’ to and, indeed, remembered by tourists will directly affect the sense of ‘tragic places’ (Grebenar, Citation2018; Seaton, Citation2009). With political dissonance inherent within memorial messages, tensions between official and unofficial discourses at dark tourism sites lend tragedy to be a commodified item and, ultimately, for subsequent placemaking to occur (Cochrane, Citation2015; Isaac, Citation2015; Krisjanous, Citation2016; Lennon & Foley, Citation2017). This is particularly so with regard to the commercial and often kitsch design of cultural mementos or destination emblems and, subsequently the semiology of a dark tourism place. We now turn to these issues.

Dark tourism products and kitschification

Much of dark tourism placemaking through commodification opens itself up to mercantile retail and, specifically, kitschification (Sharpley and Stone, Citation2009). In other words, commodifying dark tourism through kitsch is the design and selling of mass-produced branded products, souvenirs, or trinkets associated with tragedy, which may be in poor artistic taste because of excessive garishness or sentimentality. Indeed, dark tourism is littered with kitsch items for sale that purports to offer touchstones of tragic memory (Sharpley, Citation2009; Sturken, Citation2007). Of course, kitsch is often appreciated in an ironic or knowing way: yet any kitsch inherent in commodifying dark tourism has the potential to strip the auratic nature of a site. That said, Boniface (Citation1995) argues it is imperative to encourage visitors by conveying value, which is often difficult without ‘symptoms’ of commodification, such as entrance fees, overt marketing, or kitsch products and materials (Frew, Citation2013; Willard et al., Citation2013).

While kitsch is a relatively common term, its exact meaning is somewhat more ambiguous. It can mean objects or designs which embody concepts such as commercialism or sentimental excess (Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009), easily understood or simplified messages (Lugg, Citation1999), issues of ‘sweetness, schmaltz and comfort’ (Emmer, Citation2014, p. 26), notions of superficiality (Potts, Citation2012; Sturken, Citation2007), or dubious artistic taste (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Citation1998; Ward, Citation1991). However, rather than being seen as meaningless sentimental tat, kitsch may be viewed through a commercial prism of cultural influence (Emmer, Citation2014). Although kitsch objects for retail, such as mass-produced tourist souvenirs, mementos, and gifts, demonstrate complex notions; in reality, they do not neatly embody such messages. Potts (Citation2012) argues that it is a distanced and uncritical message and one that can manipulate ‘emotional significance’ in order to sell a particular image, ideal, or place (Lugg, Citation1999, p. 3) – or even promote government policy (Lugg, Citation1999; Sturken, Citation2007). Within the visitor economy, kitsch retailing maintains a status quo, or nostalgically communicates how life ‘should be’ – or perhaps would be, if not for the complications of real life (Lugg, Citation1999). Indeed, Sharpley and Stone (Citation2009) note that ‘nostalgic kitsch’ reinforces a selective recall in which inconvenient or unpleasant aspects of life are erased or romanticised. Conversely, those aspects of life that haunt the collective consciousness, such as 9/11 and its subsequent touristification at Ground Zero, might instil a kind of ‘melancholic kitsch’ in tourist souvenirs that (re)present and sustain a sense of existential loss (Stone, Citation2012b) – but renders the subject void of political meaning (Sharpley, Citation2009; Sturken, Citation2007)

Thus, the context in which kitsch appears can engender a specific reaction and, as such, retailing kitsch products may be seen as an attempt to ‘make’ a tourist experience. However, the true extent of its pervasion is unclear because taste and judgment, a key but subjective barometer in the consumption of dark tourism define kitsch (Sturken, Citation2007). As Ward (Citation1991, p. 6) notes, humans have an understanding of taste based upon an ‘amalgam of influences from different times and different places’. Similarly, Urry (Citation2005) argues the ‘post-tourist gaze’ means visitors to a site interpret various semiotic cues and locate them within their own understanding, which is itself based on previous semiotic cues. As noted earlier, dark tourism is polysemic and subject to different provocative meanings and emotive influences. This may explain, in part at least, why kitschification within dark tourism is such a divisive issue. Indeed, Potts (Citation2012, p. 238) vociferates against the ‘bankrupt destiny’ of kitsch, suggesting that it offers nothing to, and clouds our understanding of, real issues within the dark tourism experience (also Emmer, Citation2014). Similarly, Westbrook (Citation2002, p. 426) argues kitsch is inherently ‘self-delusional’ and those who buy into sentimentality without a sense of irony are (being) misguided. Ultimately, the commodification of kitsch for mass consumption can purvey an uncritical, if not romanticised past (Lugg, Citation1999). Crucially however, within dark tourism, consumers must be able to discern that it is a simplified version of a tragic past (Grebenar, Citation2018). Otherwise, as Sharpley and Stone (Citation2009) argue, commodified kitsch products can render complex death events meaningless, provoke a sense of trivialisation, and manipulate (mis)understandings of contested heritage.

Despite these potential pitfalls, the process of ‘kitschification’ has been noted within the realm of dark tourism (Frew, Citation2018; Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009). Specifically, kitsch and the commodification of atrocities has been observed at a range of visitor sites, including but not limited to, Ground Zero (Brown, Citation2013; Potts, Citation2012; Sturken, Citation2007), the Imperial War Museum and the International Slavery Museum (both UK, Brown, Citation2013), and even at sites of Holocaust memorialisation (Podoshen, Citation2017; Brown, Citation2013; Kertész, Citation2001). However, kitschification remains disputed and the selling of kitsch products at a given site do not necessarily mean that it has been ‘kitschified’ (Potts, Citation2012, p. 247). Even so, within the specific context of dark tourism at Ground Zero, Potts (Citation2012, p. 233) laments there is a ‘conspicuous commodity culture’, in which visitors are actively encouraged to consume kitsch branded items ranging from snow globes – to soft toys – to gaudy trinkets – all bearing the date and location of the 9/11 atrocities. However, Sturken (Citation2007, p. 38) argues kitschification at Ground Zero engenders a sense of ‘comfort consumerism’. In other words, kitsch tourist souvenirs retailed at dark tourism sites are simply due to neo-liberal market forces, in that consumers expect to see these standardised and familiar products and, consequently, seek a level of comfort in the neutralisation of the emotive event. In essence, producing and consuming kitsch is akin to retailing tragic memories and, subsequently, making tragic places accessible for the mind. Lugg (Citation1999) even suggests that the absence of kitsch items may upset or confuse tourists, leaving them with a lack of means to deal with the trauma at the site (also Yoshida, Bui, & Lee, Citation2016). Therefore, this notion of sentimentality in dark tourism increasingly relies on commodifying kitsch to represent an atrocity that, in turn, can be produced and consumed. Moreover, kitschification of tragedy through dark tourism can also engender a destination iconography that can become part of the cultural fabric of a place (for example, Marques & Borba, Citation2017).

Importantly, Potts (Citation2012) and Sturken (Citation2007) argue kitsch products and its inherent sentimentality within dark tourism may be rendering ethical issues as much as it raises moral dilemmas and, subsequently, making tragedy through commodification more accessible. Thus, kitschification makes tragic places identifiable. Indeed, the presence of kitsch at Ground Zero and its associated 9/11 memorials, for example, ensures the site is ‘charged with meaning’ Sturken (Citation2007, p. 168). Even as the reconstruction of the commemorative space was underway, including the official 9/11 ‘Reflecting Absence’ memorial, dark tourism placemaking at Ground Zero mediates the terrorist atrocity to the rest of the world (Lisle, Citation2004). In particular, dark tourism at Ground Zero negotiates American national wounding with sentiment, patriotism, and kitsch commodification (Stone, Citation2012b).

However, while kitsch might be perceived as ‘morally reprehensible’ within dark tourism (Brown, Citation2013, p. 243), Westbrook’s (Citation2002) assertion is that kitsch fills a void previously occupied by overtly political feelings or activity. In the example of Ground Zero, rather than railing against, say, US-led aggression or impotent US foreign policy, or even terrorism, kitsch allows tourists to (re)affirm their innocence by transferring complex issues into simple entities (Sturken, Citation2007). This ‘selling of comfort’ acts as a superficial symbol of an individual’s engagement with the subject matter (Sturken, Citation2007, p. 37). Arguably, therefore, it allows one to engage in both conspicuous consumption and, because of the invested meaning of the kitsch product, conspicuous compassion in times of national trauma (Grebenar, Citation2018; West, Citation2004).

Kitsch and its semiotic tourist value in perpetuating an iconography of tragic places is also recognised by White (Citation2013) in her examination of crime and dark tourism in Australia. She notes costume and performativity are integral for Melbourne tours, particularly those that relate to criminality in the city in which tour guides dress and perform in prisoner-style jumpsuits. Such visual links and playful attitudes might be seen as adding value to heritage experiences, thus imbuing semiotic meaning to a destination through kitsch representation. In this case, costume being used as kitsch theatrical prop in dark tourism performances (Taheri & Jafari, Citation2012; Willis, Citation2014). Of course, kitsch products that relate to death at dark tourism sites may have deeper ‘discovery’ elements attached to them and, arguably, without them visitors may leave the site having not fully grasped its significance (Grebenar, Citation2018). In this respect, kitschification of dark tourism may potentially allow enhanced engagement with the tragic issues on show.

To that end, Yoshida et al. (Citation2016) suggest entertainment and education are not opposite but in fact part of a simultaneous cycle within any given site experience. Whilst Brown’s (Citation1996) ‘genuine fakes’ pander to tourists’ expectations of kitsch, MacCannell (Citation1976) argues that tourists can accept these staged rituals as essentially fake, but enjoyable nonetheless in a kind of post-tourism (after Urry, Citation2005). Hence, while retailing kitsch items may appear to be tasteless or shallow or even unethical, its inherent commodification of tragedy often forms part of the tourist experience and perception of places where atrocity has occurred. As such, a simplified, even juvenile representation of atrocity may be the most acceptable way for tourists to engage with, and affirm association of, a place that has experienced tragedy (Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009). It is to this engagement of kitsch dark tourism on a societal level and, subsequently, how its commodification may be appropriated in mass responses to tragedy that our paper now turns.

Kitsch, tragic memories and semiotic appropriation

Destinations depend upon specific images, icons, or particular architecture that emblemises an attachment to a place. Most obvious among these are physical landmarks or constructions that act as destination signifiers (e.g. Eiffel Tower and Paris): but they may also be images that represent specific cultural dimensions of a place and people. For example, the apple that has come to symbolise the ‘Big Apple’ of New York is a simple, if not kitsch icon, that has been appropriated to suggest empire and economic wealth, urban dynamism, as well as political liberalism. First used in 1920s horseracing articles to describe New York, the ‘Big Apple’ entered mainstream New York semiology in the 1970s when it was utilised in marketing campaigns to entice tourists to the city. Since then, New York is often referred to as the ‘Big Apple’ and, in so doing, infers deeper socio-cultural and political discourses (Jackson, Citation2010). Indeed, the ‘apple’ of the city has been bastardised so much across multiple tourist gifts and trinkets that visitors may purchase the symbol rather than buy the functional value of a product. It is here that appropriation of kitsch iconography has potential to influence broader political discourse if mobilised on a greater scale (Sturken, Citation2007). Indeed, such iconography may shape public sentiment if mobilised in an appropriate way and, consequently, become ‘political communiques’ and act as symbols of power (Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009; Yoshida et al., Citation2016). These symbols of a space not only represent a place, but also the very semiotics can be appropriated en-masse and, as result, arbitrate ‘dominant discourses’ (Siriyuvasak, Citation1991).

Of course, death of the tragic Other is mediated through dark tourism and, as such, can be (re)presented as heroic, heart-breaking, pathetic, deserved, or some other ascribed value (Coombs, Citation2014; Stone, Citation2017). Indeed, Wales (Citation2008) suggests the mediator in such traumascapes has a profound effect on how the representation appears. Thus, the mediator in dark tourism is often mass-produced kitsch commodities and the appropriation of kitsch iconography. For example, the ubiquitous snow-globe trinket on sale at Ground Zero is a kitsch touristic staple; but in times of national trauma can mediate varying scenes of spirit, valour, or even patriotism (Sturken, Citation2007). This simple intercession can lead to a domination of the kitsch commodity within complex notions of national mourning (Potts, Citation2012). Indeed, as noted earlier, the unassuming and commodified message through kitsch keepsakes neatly encapsulates a given sentiment. This simplicity potentially allows tragedy to be understood more easily and replaces nuanced ideological standings with trivialised or distorted emotion (Potts, Citation2012) – that, in turn can lead to a ‘cultural conditioning of society’ (Stone, Citation2016, p. 24). Of course, whether this is essentially positive, negative, or benign remains subjective and open to polysemic interpretation.

Nevertheless, despite the potential of commodified kitsch dominating and rendering more complex issues, it may be the case that dark tourism kitschification is less intentional. Indeed, Brown (Citation2013) states that kitsch items may be on sale merely due to their popularity at other sites, and therefore its presence is simply consumer-driven. Lugg (Citation1999, p. 4) even suggests that kitsch is something of a sop to placate tourists, and a lack of kitsch predictability can provoke ‘irate reactions’. In other words, appropriation of kitsch as a mediator in dark tourism often keeps the status quo as a way of maintaining taste (Light, Citation2017; Stone, Citation2016). Though Ward (Citation1991) argues discernment of taste is based upon prior experiences, kitsch can be used to perpetuate myths and provide simplified nostalgic or melancholic representations (Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009). Importantly, however, in terms of making a ‘tragic place’, dark tourism consumerism and its inherent kitsch commodities negotiate tragedy and traumascapes for mass consumption. The mass appropriation of kitsch iconography in times of atrocity may appear easy and attractive to mediate collective grief. For example, during recent terrorist attacks in France, the French flag was appropriated by social media platforms using translucent photographic filters to offer temporary but kitsch social media profile pictures that, in turn, intended to promote national unity and collective spirit (Feeney, Citation2015). However, such appropriation may also render any atrocity to its most rudimentary level; consequently, ignoring complex issues of origin and root cause of tragedies. Therefore, the issue remains of how destinations that have suffered atrocity cannot only harness the semiotic power of kitsch within dark tourism, but also how kitsch is appropriated and commodified by a mass-mediated response to such tragedy. It is to this point that we now turn as way of summary and context. Specifically, a city emblem of Manchester in the UK – the Manchester Bee – has been appropriated from history in times of tragedy and, subsequently, commercially embedded within dark tourism kitschification. It is here that contextual insights rather than a full empirical examination provide for future research avenues, whereby placemaking collides with tourism and kitschification – thus potentially transforming the iconography of a (tragic) destination.

Making tragic places: the Manchester worker bee

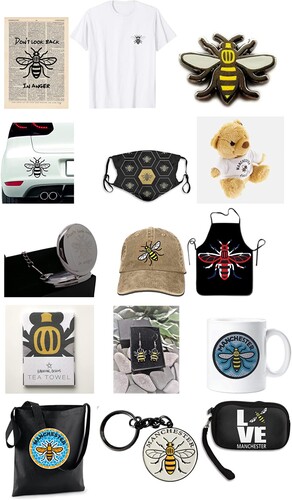

In May 2017, after an Ariana Grande concert at the Manchester Arena (UK), an Islamist terrorist denoted a suicide bomb murdering 22 people and injuring over 800 others (BBC, Citation2018). More than half the victims were children, with the youngest being an eight-year-old girl. Misogynistic targeting of a predominantly young female audience and the killing of such youth led to a rupture of emotional responses to the atrocity (Ben-Ezra, Hamama-Raz, & Mahat-Shamir, Citation2017). During the immediate aftermath of the attack, and in the following years, a previously obscure icon of the city symbolically captured collective grief: the Manchester Bee ().

Indeed, the simple bee symbol now appears throughout Manchester – including on flowerpots, traffic bollards, signs posts, tile artwork, and street murals. The worker bee symbol was first adopted during the Industrial Revolution depicting hardworking Mancunians and the city as a ‘buzzing hive’ of manufacturing. In 1842, the bee was incorporated on the city’s coat of arms to highlight Manchester’s international links and status. However, until the 2017 attack, the bee symbol largely faded from much of the city’s landmarks and cultural awareness. Now, the bee has been revitalised and reinvented as an internationally recognised symbol of solidarity and remembrance in the face of atrocity (Cooper, Citation2018).

The symbolic insect has been trademarked by Manchester City Council and, subsequently, made free-to-use on condition of a charitable donation (Manchester City Council, Citation2018). As a result, numerous representations, artwork, trinkets, merchandise, and memorials depicting the ‘Manchester Bee’ have proliferated since 2017 (for example, and ). This is both in direct reference to the attack, but also non-referentially through the opportune invoking of Manchester as a cultural location. The Manchester Bee is not only a rejuvenated symbol of the city once again, but it also has become a galvanised icon of death and tragedy. Indeed, its naïveté and, arguably, kitsch artistic design lends itself to multi-product commercial branding, where sentimentality is manufactured and loss is rendered.

Figure 2. Memorial plaque in Royton Park, Greater Manchester. Sometimes, the bee symbol will appear with the song title by the Manchester rock band Oasis. ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger’. Source: Author.

Figure 3. Appropriation of the Manchester Bee icon since the 2017 terrorist attack. From Top and Left to Right: ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger’ Dictionary Art Print with Vintage Manchester Bee Quote/Manchester Bee T-shirt/Manchester Emanuel Badge/Manchester Vinyl Car Sticker/Manchester Bee Face Mask/Manchester Bee Teddy Bear/Manchester Bee Pocket Watch/Manchester Bee Unisex Cowboy Cap/Manchester Bee Chef apron/Manchester Bee tea towel/Manchester Bee earrings/Manchester Bee mug/Manchester Bee tote bag/Manchester Bee keyring/Love Manchester Bee Zipper handbag. Source: Amazon, 2020.

The Manchester Bee as an appropriated symbolic response to the 2017 attack was quickly adopted as the de facto symbol of remembrance and solidarity (Cooper, Citation2018). However, its subsequent commercial activity in the form of branded gifts and souvenirs is noteworthy for two reasons. Firstly, the bee is not overtly political or melancholic in nature; it allows the individual to assume symbolism of solidary without inviting critique. Secondly, the bee icon through its purchase and proliferation allows individuals to claim membership of a grieving community in a manner concomitant with the semiotics of a consumerist society. Arguably, therefore, kitschification of the Manchester Bee serves the dual function of both cityscape symbol as well as a new icon of atrocity, remembrance, and solidarity. In so doing, the contemporary placemaking of Manchester means the 2017 attack is subsumed into the cultural fabric of the city and its visitor economy. It is here where dark tourism provides for a spectacle of death through a restored iconography of Manchester (Sternberg, Citation1997; Stone, Citation2020).

This renewed iconography of Manchester – that is, an abundant kitsch icon of place and people – is now rooted in terrorism and tragedy. Yet, it is important to note that as a place, Manchester is known for many things, including its rich industrial heritage, vibrant music scene, and cultural endeavours. While the Manchester Bee re-emerged as a mass-mediated icon because of the 2017 attack, it also transcends that atrocity and has polysemic meanings. In other words, the authentication of the Manchester Bee and its versatile use has led to its mass commodification and subsequent visibility. Consequently, its ubiquitous and apparently seamless (re)appearance as Manchester’s de facto icon demonstrates not only how kitsch can be used to ‘make’ a place, but also how kitsch can be used to distil multiple discourses into one simplified representation (Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009).

This singular representation of a tragic event has many meanings, which the Manchester Bee perpetuates. The shared grief of the attack, the collective memory of difficult heritage, the aura and spectacle of death in remembrance, and its commercialisation and retail, are all now channelled through a simple kitsch icon. Thus, the Manchester Bee ‘makes’ Manchester into something new – a fresh iteration burdened by the deaths of 22 people, but nonetheless united by history, hope, and endurance. Of course, questions remain over how the Manchester Bee as a placemaking symbol and consumed through dark tourism can fulfil twin intentions of both grief and hope. The icon has been appropriated from a proud industrial heritage, retailed through commercialism, and experienced through dark tourism. It is now a city emblem rooted in atrocity, an icon reborn and recast to symbolise Manchester as not only a place of tragedy, but also one of remembrance and solidary.

Conclusion

The aim of our paper was to examine dark tourism and the commercialisation of tragedy, and subsequent impact on destination iconography. We drew upon notions of commodification, placemaking, kitschification, and semiotics. In summary, when an atrocity or disaster occurs that disrupts and upsets our collective psyche, victims become the significant Other dead and, in turn become memorial foci. Consequently, our notable dead have become ‘spectacles’ to retail, to remember, and to experience within a new spectacular death mentality. Hence, deathscapes of our prominent dead are created and recreated by dark tourism. Indeed, dark tourism displays our difficult heritage and showcases places of pain and shame. It is here where commemoration of the dead and commercialisation of tragic memory are juxtaposed within visitor economies that trade our haunting past. Yet, in a consumerist mercantile world, demarcations between commemorating the tragic dead and commercialising their passing are increasingly distorted and nebulous. Moreover, the provocative nature of dark tourism means that sites are auratic, and often possess a politically contested if not an emotionally charged aura. In turn, visitor experiences may be polysemic where different meanings are co-constructed from dark tourism interpretations. Even so, despite the auratic and polysemy nature of dark tourism, representations of tragedy often invent or appropriate an icon to consume, which, in turn, renders atrocity into grief, hope, solidarity, and tribute.

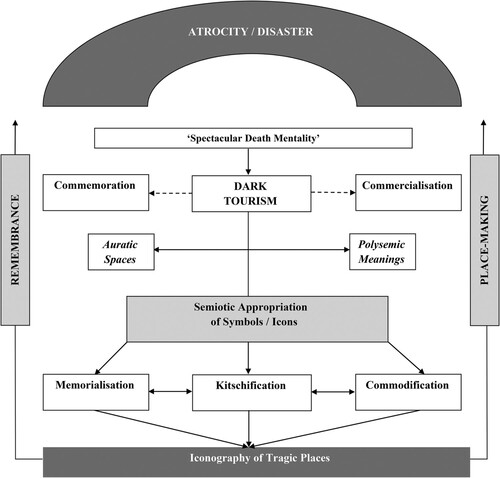

The semiotic appropriation of symbols or icons provides a touchstone of memory to tragedy. It is here where memory management and tourism collide, and memorialisation and commodification conflate. At the heart of this is the process of kitschification, with all its naivety and sentimentality, and the mass production and consumption of signs and branded products of tragedy. Consequently, an iconography of tragic places emerges, which trades on specific semiotics and renders atrocity and disaster to its most rudimental. Yet, within this conceptual cauldron, and briefly contextualised by our Manchester Bee mini-case study, dual aspects of remembrance and placemaking are occurring. Importantly, it is here where the original atrocity or disaster remains at the forefront of collective memory. illustrates this by way of providing a conceptual model of dark tourism and making tragic places. In so doing, the summative conceptual model provides a theoretical sketch of the fundamental interrelationships of dark tourism in consumer society.

In essence, sketches and links placemaking concepts in post-traumatic places. When an atrocity or disaster occurs as represented by the arch in the model, the resultant traumascape envelopes both place and community. Within a period, and sometimes a very short period, the spectacular death mentality that is now part of our cosmopolitan age invokes dark tourism. Consequently, the dual aspects of commemoration and commercialisation come into play, as the dead become significant in our collective consciousness. As the dead become memorialised, auratic spaces of atrocity take on polysemic meanings where visitors experience dark tourism representations of the death event. These representations are then often manifested in semiotic appropriation of specific symbols, pictures or icons and, subsequently, turned into commercial souvenirs. For instance, the Manchester Bee reclaimed from history as highlighted earlier, appropriating the Twin Towers as Ground Zero keepsakes, or the slogan ‘Je suis Charlie’ (I am Charlie) as a brand to demonstrate freedom after the terrorist attack in France on 7 January 2015. As a result, notions of memorialisation, kitschification, and commodification collide, creating an iconography of tragic places. As further illustrates, from here, both remembrance and placemaking occur – and ‘making tragic places’ through dark tourism is played out within visitor economies.

Of course, whilst the model in may offer a conceptual route map for the future interrogation of placemaking and dark tourism, it is not without its limitations and omissions. Indeed, issues of dissonance, religiosity, and the role of popular culture, social media, or even post-tourism are worthy of scrutiny in dark tourism placemaking. That said, however, the emergent conceptual model provides a blueprint in which to reconnoitre future studies in dark tourism, its impact on placemaking, and commodification of significant deaths. In turn, the ripples of the dead (Pratchett, Citation1991) will continue to undulate in a dark tourism industry that not only symbolically remembers our dead, but also commercialises their tragic demise.

Dedication

Our paper is dedicated to the memories of the 22 souls who were murdered by the terrorist atrocity in Manchester, UK, 2017.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (12.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Philip R. Stone

Philip R. Stone is Executive Director of the Institute of Dark Tourism Research at UCLan and has published extensively in the area of “dark tourism” and “difficult heritage”.

Alex Grebenar

Alex Grebenar is a Lecturer in Events and Tourism Management at UCLan with research interests in dark tourism, heritage, and music events.

References

- BBC News. (2018). Manchester arena attack: Bomb ‘injured more than 800’. BBC News Online. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-manchester-44129386 [Accessed: 8 June 2020]

- Ben-Ezra, M., Hamama-Raz, Y., & Mahat-Shamir, M. (2017). Psychological reactions to the 2017 Manchester arena bombing: A population based study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 95, 235–237.

- Bird, G., Westcott, M., & Thiesen, N. (2018). Marketing dark heritage: Building brands, myth-making and social marketing. In P. R. Stone, R. Hartmann, T. Seaton, R. Sharpley, & L. White (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of dark tourism studies (pp. 645–665). London: Palgrave Macmillian.

- Boniface, P. (1995). Managing quality cultural tourism. London: Routledge.

- Boorstin, D. J. (1987). The image, 25th anniversary edition. New York: Vintage Books.

- Bouchard, G. (2010). Bodyworlds and theatricality: Seeing death, live. Performance Research, 15(1), 58–65.

- Brown, D. (1996). Genuine fakes. In T. Selwyn (Ed.), The tourist image: Myths and myth making in tourism (pp. 33–48). Chichester: Wiley.

- Brown, J. (2013). Dark tourism shops: Selling ‘dark’ and ‘difficult’ products. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 7(3), 272–280.

- Cave, J., & Buda, D. (2018). Souvenirs in dark tourism: Emotions and symbols. In P. R. Stone, R. Hartmann, T. Seaton, R. Sharpley, & L. White (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of dark tourism studies (pp. 707–726). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cochrane, F. (2015). The paradox of conflict tourism: The commodification of war or conflict transformation in practice? The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 22(1), 51–69.

- Cole, T. (2000). Selling the holocaust: From Auschwitz to Schindler – How history is bought, packaged and sold. London: Routledge.

- Coombs, S. (2014). Death wears a T-shirt – listening to young people talk about death. Mortality, 19(3), 284–302.

- Cooper, M. (2018). ‘Why is a worker bee the symbol of Manchester?’ Manchester Evening News. Retrieved from https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/manchester-bee-symbol-meaning-tattoo-11793163 [Accessed: 8 June 2020]

- Cresswell, T. (2015). Place: An introduction. London: Wiley Blackwell.

- Debord, G. (1967/1994). The society of the spectacle. New York: Zone Books.

- Dupre, K. (2019). Trends and gaps in place-making in the context of urban development and tourism: 25 years of literature review. Journal of Place Management and Development, 12(1), 102–120.

- Elkington, S. (2015). Disturbance and complexity in urban spaces: The everyday aesthetics of leisure. In S. Gammon & S. Elkington (Eds.), Landscapes of leisure: Space, place and identities (pp. 24–40). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Emmer, C. E. (2014). Traditional kitsch and the Janus-head of comfort. In J. Stępień (Ed.), Redefining kitsch and camp in literature and culture (pp. 23–40). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Feeney, N. (2015). Facebook’s new photo filter lets you show solidarity with Paris. TIME. Retrieved from https://time.com/4113171/paris-attacks-facebook-filter-french-flag-profile-picture/ [Accessed 30 May 2020].

- Foote, K. E. (2003). Shadowed ground: America’s Landscape of violence and tragedy, (revised edition). Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Frew, E. (2013). Dark tourism in the top end: Commemorating the bombing of Darwin. In L. White & E. Frew (Eds.), Dark Tourism and Place Identity: Managing and interpreting dark places (pp. 248–263). London: Routledge.

- Frew, E. (2018). Exhibiting death and disaster: Museological perspectives. In P. R. Stone, R. Hartmann, T. Seaton, R. Sharpley, & L. White (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Dark Tourism studies (pp. 693–706). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grebenar, A. (2018). The commodification of dark tourism: Conceptualising the visitor experience (Unpublished Doctoral thesis). University of Central Lancashire, Preston, UK.

- Holt, A., & Wilkins, C. (2015). ‘In Some Eyes it’s Still Oooh, Gloucester, Yeah Fred West’: Spatial stigma and the impact of a high-profile crime on community identity. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25(1), 82–94.

- Isaac, R. K. (2015). Every utopia turns into dystopia. Tourism Management, 51, 329–330.

- Jackson, K. T. (2010). The encyclopedia of New York (2nd ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Jacobsen, M. H. (2016). ‘Spectacular death’ – proposing a new fifth phase to Philippe Ariès’s admirable history of death’. Humanities, 5(19), 1–20.

- Jarratt, D., Phelan, C., Wain, J., & Dale, S. (2018). Developing a sense of place toolkit: Identifying destination uniqueness. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 0(0), 1–14.

- Kertész, I. (2001). Who owns Auschwitz? Yale Journal of Criticism, 14(1), 267–272.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. (1998). Destination culture: Tourism, museums, and heritage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Krisjanous, J. (2016). An exploratory multimodal discourse analysis of dark tourism websites: Communicating issues around contested sites. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(4), 341–350.

- Lennon, J. J. (2017). Conclusion: Dark tourism in a digital post-truth society. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 9(2), 240–244.

- Lennon, J. J., & Foley, M. (2000). Dark tourism: The attraction of death and disaster. London: Continuum.

- Lennon, J. J., & Teare, R. (2017). Dark tourism – visitation, understanding and education; a reconciliation of theory and practice? Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 9(2), 245–248.

- Lew, A. A. (2017). Tourism planning and place making: Place-making or placemaking? Tourism Geographies, 19(3), 448–466.

- Light, D. (2017). Progress in dark tourism and thanatourism research: An uneasy relationship with heritage tourism. Tourism Management, 61, 275–301.

- Lisle, D. (2004). Gazing at Ground Zero: Tourism. Voyeurism and Spectacle. Journal for Cultural Research, 8(1), 3–21.

- Lugg, C. A. (1999). Kitsch: From education to public policy. New York: Falmer Press.

- MacCannell, D. (1976). The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. New York: Schocken Books.

- Manchester City Council. (2018). The council makes the iconic Manchester Bee symbol available to use. Manchester City Council News. Retrieved from https://secure.manchester.gov.uk/news/article/7935/the_council_makes_the_iconic_manchester_bee_symbol_available_to_use [Accessed: 19 June 2020].

- Marques, L., & Borba, C. (2017). Co-creating the city: Digital technology and creative tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 24, 86–93.

- McKenzie, B. (2018). ‘Death as a commodity’: The retailing of dark tourism. In P. R. Stone, R. Hartmann, T. Seaton, R. Sharpley, & L. White (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of dark tourism studies (pp. 667–691). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Morgan, N., & Pritchard, A. (2005). On souvenirs and metonymy. Tourist Studies, 5(1), 29–53.

- O’Neill, S. (2002). Soham pleads with day trippers to stay away. The Telegraph. Retrieved from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1405391/Soham-pleads-with-trippers-to-stay-away.html [Accessed: 19 June 2020].

- Phipps, P. (1999). Tourists, terrorists, death and value. In R. Kaur & J. Hutnyk (Eds.), Travel worlds: Journeys in contemporary cultural politics (pp. 74–93). London: Zed Books.

- Podoshen, J. S. (2017). Trajectories in Holocaust tourism. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 12(4), 347–364.

- Potts, T. J. (2012). Dark tourism’ and the ‘kitschification’ of 9/11. Tourist Studies, 12(3), 232–249.

- Prachett, T. (1991). Reaper man. London: Orion Publishing Group.

- Relph, E. (1976). Place and placelessness. London: Pion Limited.

- Rofe, M. W. (2013). Considering the limits of rural place making opportunities: Rural dystopias and dark tourism. Landscape Research, 38(2), 262–272.

- Sather-Wagstaff, J. (2011). Heritage that hurts: Tourists in the memoryscapes of September 11. New York: Routledge.

- Seaton, T. (2009). Purposeful otherness: Approaches to the Management of thanatourism. In R. Sharpley & P. R. Stone (Eds.), The darker side of travel: The theory and practice of dark tourism (pp. 75–108). Bristol: Channel View Publications.

- Sharpley, R. (2009). Shedding Light on dark tourism: An introduction. In R. Sharpley & P. R. Stone (Eds.), The darker side of travel: The theory and practice of dark tourism (pp. 3–22). Bristol: Channel View Publications.

- Sharpley, R., & Stone, P. R. (2009). (Re)presenting the macabre: Interpretation, kitschification and authenticity’. In R. Sharpley & P. R. Stone (Eds.), The darker side of travel: The theory and practice of dark tourism (pp. 109–128). Bristol: Channel View Publications.

- Siriyuvasak, U. (1991). Cultural mediation and the limits to 'Ideological domination': The mass media and Ideological representation in Thailand. SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 6(1), 45–70.

- Spokes, M., Denham, J., & Lehmann, B. (2018). Death, memorialisation and deviant spaces. London: Emerald Publishing.

- Sternberg, E. (1997). The iconography of the tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(4), 951–969.

- Stone, P. R. (2006). A dark tourism spectrum: Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibitions. TOURISM: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 54(2), 145–160.

- Stone, P. R. (2009). ‘'It's a bloody guide': Fun, fear and a lighter side of dark tourism at the Dungeon visitor attractions, UK’. In R. Sharpley & P. R. Stone (Eds.), The darker side of travel: The theory and practice of dark tourism (pp. 167–185). Bristol: Channel View Publications.

- Stone, P. R. (2012a). Dark tourism and significant other death: Towards a model of mortality mediation. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(3), 1565–1587.

- Stone, P. R. (2012b). Dark tourism as ‘mortality capital’: The case of Ground Zero and the significant other dead. In R. Sharpley & P. R. Stone (Eds.), Contemporary tourist experience: concepts and consequences (pp. 71–94). London: Routledge.

- Stone, P. R. (2016). Enlightening the ‘dark’ in dark tourism, association of heritage interpretation. AHI Journal, 22(2), 22–24.

- Stone, P. R. (2017). Dark tourism in an age of ‘spectacular death’: Towards a new era of showcasing death in the early 21st century. Current Issues in Dark Tourism Research, 1, 1. Retrieved from www.dark-tourism.org.uk [Accessed: 19 June 2020].

- Stone, P. R. (2018). Dark tourism in an Age of ‘spectacular death’. In P. R. Stone, R. Hartmann, T. Seaton, R. Sharpley, & L. White (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of dark tourism studies (pp. 189–210). London: Palgrave Macmillian.

- Stone, P. R. (2020). Dark tourism and ‘spectacular death’. Towards a conceptual framework. Annals of Tourism Research, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102826 [Accessed: 19 Jun 2020]

- Sturken, M. (2007). Tourists of history: Memory, kitsch, and consumerism from Oklahoma city to Ground Zero. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Taheri, B., & Jafari, A. (2012). Museums as playful venues in the leisure society. In R. Sharpley & P. R. Stone (Eds.), Contemporary Tourist Experience: concepts and consequences (pp. 201–215). London: Routledge.

- Toussaint, S., & Decrop, A. (2013). The Père-Lachaise cemetery: Between dark tourism and heterotopic consumption. In L. White & E. Frew (Eds.), Dark tourism and place identity: Managing and interpreting dark places (pp. 13–27). London: Routledge.

- Tuan, Y. F. (1977). Space and place: The perspective of experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Urry, J. (2005). The ‘consuming’ of place. In A. Jaworski & A. Pritchard (Eds.), Discourse, communication and tourism (pp. 19–27). Bristol: Channel View Publications.

- Wales, A. (2008). Landscapes of memory: Media representations of slavery and abolition. International Journal of the Humanities, 6(8), 1–7.

- Walsh, A., & Giulianotti, R. (2007). Ethics, money and sport: This sporting mammon. London: Routledge.

- Walter, T. (2020). Death in the modern world. London: Sage.

- Wang, W., Chen, S., & Xu, H. (2019). Resident attitudes towards dark tourism, a perspective of place-based identity motives. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(13), 1601–1616.

- Ward, P. (1991). Kitsch in sync: A consumer's guide to bad taste. London: Plexus Publishing.

- West, P. (2004). Conspicuous compassion: Why sometimes it really is cruel to be kind. London: Civitas.

- Westbrook, J. (2002). Cultivating kitsch: Cultural bovéism. The Journal of Contemporary French Studies, 6(2), 424–435.

- White, L. (2013). Marvellous, murderous and macabre Melbourne: Taking a walk on the dark side. In L. White & E. Frew (Eds.), Dark tourism and place identity: Managing and interpreting dark places (pp. 217–235). London: Routledge.

- White, L., & Frew, E. (2013). Dark tourism and place identity: Managing and interpreting dark places. London: Routledge.

- Wilford, A. (2015). Celebrity ‘Tourists’ and the terrible spectacle of re-territorializing trauma in Chechnya’s post-urbacide city. American Society of Theatre Research, November 5–8, Portland, Oregon. http://eprints.chi.ac.uk/id/eprint/2047/ [Accessed 16 July 2021].

- Willard, P., Lade, C., & Frost, W. (2013). Darkness beyond memory: Battlefield at Culloden and Little Bighorn. In L. White & E. Frew (Eds.), Dark tourism and place identity: Managing and interpreting dark places (pp. 264–2275). London: Routledge.

- Willis, E. (2014). Theatricality, dark tourism and ethical spectatorship: Absent others. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Yoshida, K., Bui, H. T., & Lee, T. J. (2016). Does tourism illuminate the darkness of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5, 333–340.