Abstract

In the context of serious coronavirus epidemic, it is critical that pregnant women not be ignored potentially life-saving interventions. So, this study was designed to improve the quality of care by health providers through what they need to know about coronavirus during pregnancy and childbirth. We conducted a systematic review of electronic databases was performed for published in English, before 25 March 2020. Finally, 29 papers which had covered the topic more appropriately were included in the study. The results of the systematic review of the existing literature are presented in the following nine sections: Symptoms of the COVID-19 in pregnancy, Pregnancy management, Delivery Management, Mode of delivery, Recommendations for health care provider in delivery, Neonatal outcomes, Neonatal care, Vertical Transmission, Breastfeeding. In conclusion, improving quality of care in maternal health, as well as educating, training, and supporting healthcare providers in infection management to be prioritized. Sharing data can help to countries that to prevent maternal and neonatal morbidity associated with the COVID-19.

Keywords:

Introduction

A global public health emergency is the novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) [Citation1]. Novel coronavirus (SARS-COV-2) first recognized in Wuhan City, China, is COVID-19. Other coronavirus infections include the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV), common cold (HCoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV) [Citation2,Citation3]. Case definitions included suspected case, probable case and confirmed case [Citation1].

Studies of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 show that patients commonly develop severe pneumonia with 23–32% admitted to the intensive care unit and 17–29% of cases progressing to acute respiratory distress syndrome [Citation4,Citation5]. Among hospitalized patients, 4–15% have died [Citation4,Citation5]. The most shared symptoms are fever (43.8% of cases on admittance and 88.7% during hospitalization) and cough (67.8%) [Citation2]. Diarrhea is unusual (3.8%). On admission, ground-glass opacity is the most common radiologic outcome on computed tomography (CT) of the chest (56.4%). No radiographic or CT anomaly was found in 17.9% patients with non-severe disease and in 2.9% patients with severe disease. Lymphocytopenia was described to be present in 83.2% of patients on admission [Citation2].

The COVID-19 outbreak is rapidly increasing in number of cases, deaths and countries affected, and pregnant women need special care in relation to diagnosis, management and prevention [Citation6]. It is critical that pregnant women not be denied potentially life-saving interventions in the context of a serious infectious disease threat unless there is a compelling reason to exclude them [Citation6]. Surveillance systems for cases of COVID-19 need to include information on pregnancy status, as well as maternal and fetal outcomes. It is important to be vigilant about the spread of the disease and be able to provide rapid implementation of outbreak control and management measures once the virus reaches a community [Citation6]. So, this study was designed to improve the quality of care by health providers through what they need to know about coronavirus during pregnancy and childbirth.

Material and methods

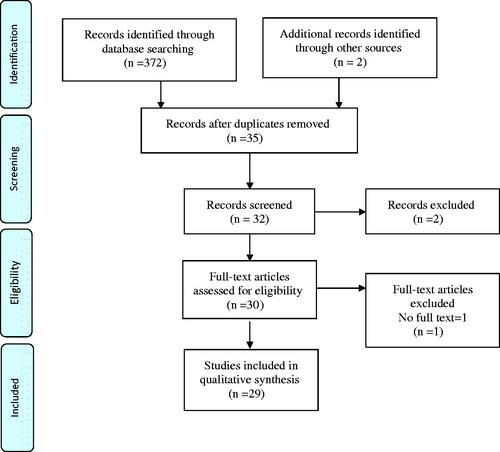

This study is a systematic review that was registered at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences – Iran in March 2020. Based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) checklist [Citation7], this study was aimed to review the body of the obtainable literature on pregnancy and childbirth with coronavirus published until 25 March 2020. For extraction of MeSH terms, keywords Considering British and American spelling, a search strategy merging the following search terms were used to ensure comprehensive coverage of studies: (“COVID-19 OR coronavirus OR 2019-nCoV “) AND (pregnancy OR childbirth OR delivery). We have searched the electronic databases including PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Seciencedirect, Clinikalkey, PsycINFO and manually tested references of the identified relevant papers. The Google Scholar databases was also reviewed to ensure that related articles were not deleted. Given the unknown and scarce information about the Corona virus, we decided to search the following databases thoroughly, using broad keywords: CDC, JAMA, Lancet, Elsevier, Oxford, Wiley, Cambridge. We limited the search to printed articles in English language. The information of studies include author, year and title of the article, summarized in . Articles were maintained when anyone of the reviewers trusted that it should be maintained. Agreement between reviewers was measured. Any conflicts between reviewers was determined by consent. After removing duplicates recognized in databases and reference lists, titles and abstracts of the texts were recorded to examine indications for meeting the inclusion criteria. For all remaining papers that were believed to be relevant, the full text was reread. All evidence from the included studies was gathered by one reviewer and checked by a second.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies in the field of coronavirus in pregnancy and childbirth.

Results

Our electronic search retrieved 375 on pregnancy and childbirth with coronavirus. After removing duplicates, reviewing titles and abstracts, 32 articles remained for full-text screening; main reason for exclusion was inconvenience with our study aim. Of the 35 titles and abstracts articles screened, three were excluded. There were 29 articles in the selection criteria. There was fit in agreement (90.40%) between reviewers on the final articles eligible for inclusion. The processes of selection for the articles are shown in . The results of the systematic review of the existing literature are presented in the following nine sections: Symptoms of the COVID-19 in pregnancy, Pregnancy management, Delivery Management, Mode of delivery, Recommendations for health care provider in delivery, Neonatal outcomes, Neonatal care, Vertical Transmission, Breastfeeding

Symptoms of the COVID-19 in pregnancy

The clinical features of these patients with COVID-19 infection during pregnancy were parallel to those of non-pregnant adults with COVID-19 infection, as earlier reported [Citation8]. But, the Liu study revealed that the clinical symptoms of pregnant women were uncharacteristic in comparison with the non-pregnant adults [Citation9]. Leukocytosis (41%) and elevated neutrophil ratio (83%) were unusually noted for the COVID-19 cases [Citation9]. The association lesions were more prevalent in the pregnant cases [Citation9]. The main symptoms of pregnant women with COVID-19 were fever and cough [Citation8]. Symptoms are mild to moderate in pregnancy [Citation10,Citation11], but 7.6% developed severe pneumonia requiring ICU care with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome in the third trimester in the Liu study [Citation10]. In the Chen study and Zhang study, none of the nine patients established severe pneumonia or died [Citation8,Citation12]. Fever and fatigue were the chief symptoms, and less common symptoms were sore throat and shortness of breath [Citation10,Citation13]. 92% of pregnant women had a clear epidemiologic history, either with other family members affected or with linkage to infected person and 23% improved after hospitalization [Citation10]. Clinical indicators symptoms in the women with COVID-19 pneumonia included fever, cough, myalgia, malaise, sore throat, diarrhea, shortness of breath, lymphopenia, increased concentrations of ALT or AST [Citation8]. COVID-19 may reduce wellbeing of both mothers and infants during pregnancy [Citation10]. Currently there is one reported case of a woman with COVID-19 who had an emergency cesarean section and finished a well recovery, required mechanical ventilation at 30 weeks’ gestation [Citation14].

The primary symptom in these mothers was fever or cough, which fetal ultrasound in the third trimester showed no clear abnormalities, and there were no significant between women who were infected by COVID-19 and who did not have the virus [Citation15]. Coronaviruses have the potential to cause severe maternal negative effects, or both [Citation16]. However, the specific symptoms were not present in pregnant women with COVID-19 pneumonia [Citation8]. Therefore, Chen recommended that Chest CT, nucleic acid tests and blood counts might have a high diagnostic, high accuracy with a low false undesirable rate [Citation8]. However, the Liu study confirmed that symptoms of pregnant women with COVID-19 pneumonia were atypical, and early detection is difficulties [Citation9].

Pregnancy management

Epidemics COVID-19 can easily occur and is highly transmissible; so, in a maternal and child health facility, the outbreak outcomes can be complex, erratic, and difficult to control [Citation15]. Thus, effective prevention and control actions improved by education should be taken during pregnancy [Citation17]. The following considerations apply to women during pregnancy:

Each recently admitted mother should receive cautious reexamination and be suitably terminated [Citation17].

Pregnant women with COVID-19 pneumonia should be taken care by a team at a tertiary care center [Citation18].

They should be categorized based on clinical evaluation, into mild (symptomatic patient with stable vital signs), severe (respiration rate ≥30/min, resting SaO2 ≤ 93%, arterial blood oxygen partial pressure (PaO2)/oxygen concentration (FiO2)≤300 mmHg) or critical (shock with organ failure, respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation or refractory hypoxemia requiring extra-corporal membrane oxygenation) [Citation19].

The situations of neonates, mothers, and their close rooming-in should be carefully evaluated [Citation15]. Favre recommended that systematic screening of any suspected COVID-19 infection during pregnancy [Citation16].

The mother should be admitted to an isolation room for care, and samples should be collected to early diagnosis and treatment, if symptoms such as fever, coughing, and poor mental status are present [Citation13,Citation15].

Chest CT scanning has high sensitivity for the diagnosis of COVID-19 [13]. In a pregnant woman with suspected COVID-19 infection, a chest CT scan may be considered as a tool for the detection of COVID-19 in epidemic zones [Citation13].

Pregnant women with COVID-19 infection should be observed with 2–4-weekly ultrasound assessment of fetal growth and amniotic fluid volume, with umbilical artery Doppler if necessary [Citation18].

Pregnant women are advised to quarantine and is recommended to: do not go to school, do not use public transport, stay at home, be in a well-ventilated room, even be separated from other family members, use a separate towel and eating utensils [Citation17].

Pregnant women should not travel to high-risk contaminated areas [Citation6].

The prenatal anxiety, depression, and stress are also considered as prevalent public health issues in pregnant women, because of the stress-related concerns of mothers about their health and the health of their babies are growing under the COVID-19 outbreak [Citation20].

Antiviral treatment has been recommended for pregnant. Antiproteases Lopinavir/Ritonavir has been the preferred drug regimen as it is known to be relatively safe in pregnancy [Citation19]. In the Liu study, pregnant women were not only treated with antiviral drugs, but also achieved good recovery [Citation13].

Delivery management

The following attentions apply to women in labor:

All mothers who have had a preterm birth should see a maternity ward immediately so that they can be cared for [Citation17].

In cases where the symptoms are mild, women can be encouraged to stay in the quarantine latent phase [Citation17].

If birth at home is planned, a discussion should begin with the woman for the probability of infected fetal [Citation8,Citation21].

In cases where labor has begun, it should be linked with a maternity ward for fetal health monitoring [Citation17].

Pregnant women with a mild clinical staging may not firstly need hospital admission and monitoring of the woman’s condition can be ensured at home [Citation1].

In the severe clinical staging, care should be taken in a negative-pressure isolation room in the ICU [Citation22] with the support of a team (midwives, obstetricians, maternal–fetal-medicine subspecialists, intensivists, infectious-disease specialists, obstetric anesthetists, neonatologists, virologists, microbiologists) [Citation6,Citation12].

A few number of healthcare providers should enter the room with essential personnel for emergency scenarios [Citation8,Citation15].

In the case of an infected mother with spontaneous preterm labor, tocolysis should not be used in an effort to delay childbirth [Citation23].

Epidural analgesia should be recommended at the early stage of labor for women with COVID-19 to minimize the need for general anesthesia, because there is a risk that the use of Entonox may increase the spread of the virus [Citation17].

For anesthesia during cesarean, single-shot spinal anesthesia is a simple and flexible technique, but comes with the risk of a failed block. So, it is better to use combined spinal and epidural anesthesia (CSEA) [Citation24].

All ventilatory circuits and anesthetic products should be discarded after surgery [Citation24].

Breathing system must contain a filter to prevent pollution with the virus (<0.05μm pore size), when Entonox is used [Citation17].

Delayed cord clamping is still recommended following delivery. The baby can be cleaned and dried as normal, when the cord is not yet clamped [Citation17].

There is inadequate data regarding increase in the risk of infection to the baby via straight contact when cord clamping is delayed [Citation25].

Mode of delivery

Mode of delivery should not be influenced by the COVID-19 if the mother’s respiratory situation needs emergency delivery. The infected mother who has spontaneous labor could be endorsed to deliver vaginally. Shortening the second stage by effective vaginal delivery via active pushing can be considered, because wearing a filtered mask may be hard for mother [Citation26]. In the Lui study, 50% of pregnant women were delivered by emergency cesarean section because of maternal morbidities such as fetal distress, premature rupture of the membrane, stillbirth and 46% preterm labor between 32 and 36 weeks [Citation10]. For mothers who become exhausted or hypoxic, an individualized decision should be made regarding shortening the length of the second stage of labor with instrumental delivery [Citation17]. Notably, uncertainty about the risk of mother-to-child transmission by vaginal delivery was another reason for carrying out cesarean sections [8]. The lack of evidence of vertical transmission infections that can occur during vaginal delivery are commendable of concern [Citation11].

Recommendations for health care provider in delivery

The subsequent recommendations apply to all hospital health care providers for management of mother with suspected or confirmed COVID-19:

Infected mother should be admitted to a negative-pressure isolation room in an ICU [Citation3,Citation27].

All hospital health care providers should have gasmask, face protective shield, goggle, surgical gloves and gown for caring a confirmed cases of COVID-19 [27]

Women should be informed to use private transportation instead of public transport and if an ambulance is required, the mother should be in quarantine for potential COVID-19 [Citation17].

Women need to be aware that a midwife to their attendance, when prior to entering the hospital, should be alerted [Citation17].

Women should be wearing an appropriate surgical face mask and it should not be removed until the woman is isolated in a suitable room [Citation17,Citation21].

Women should directly be guided to an isolation room, only essential staff should enter the room and visitors should be kept to a minimum [Citation17].

All mother rooms used will need to be washed after use as per hospital sterilization guidance [Citation17].

Healthcare providers should promptly notify infection control personnel at their units of the predicted mother who has confirmed COVID-19 [28].

Healthcare providers should ensure that mother can adhere to infection control requirements [Citation28].

Obstetric providers should obtain a detailed travel history for all patients and should definitely ask about travel in the past 14 days to common areas of COVID-19 [6].

For COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab specimen collection, all health providers should wear a powered air-purifying respirator [Citation21].

Exercise recommended to reduce anxiety, depression, and negative mood during this disease outbreak for health providers with the prolonged quarantine [Citation21].

It is obligatory for all healthcare providers that self-protection, self-care and hand hygiene is important [Citation21].

obstetric unit must be equipped to reusable, machine-washable instrument which can readily be disinfected [Citation29].

Neonatal outcomes

There are presently no evidence showing an increased risk of abortion or stillbirth in relation to COVID-19 [25]. There are case reports of preterm childbirth in women with COVID-19; however, the coronavirus infection cannot be considered the main cause iatrogenic [Citation8].

Based on the results of Zhu’s study, it is contemplated that COVID-19 in mothers may cause hypoxemia leading to increase in the risk of outcomes, such as birth asphyxia or meconium amniotic fluid [Citation11]. However, whether intrauterine fetal distress is directly related to COVID-19 infection in mothers is still unclear [Citation15]. However, the causes of premature birth were not related to COVID-19 pneumonia [Citation8]. Remarkably, based on Chen findings in nine pregnant women, there is no evidence to suggest that the development of COVID-19 pneumonia in the third trimester of pregnancy could lead to the occurrence of severe adverse outcomes in neonates and fetal infection that might be caused by intrauterine vertical transmission [Citation8]. On the other hand, Schwartz noted that coronaviruses can also result in adverse outcomes for the fetus and infant including intrauterine growth restriction, preterm delivery, admission to the ICU, spontaneous abortion and perinatal death [Citation3]. There are no data on the risk of abnormality when COVID-19 is acquired during the first or early second trimester of pregnancy [Citation23]. High fever during the first trimester of pregnancy can increase the risk of certain birth defects [Citation30]. Placental tissue pathological analysis showed that non-morphological changes related to viral infection, and no vertical transmission of mother-fetus was found [Citation31]. At this time, there is no information on long-term health effects on infants either with COVID-19 [30]. Therefore, neonatal outcomes are definitely not mentioned and need further investigation.

Neonatal care

Despite a lack of evidence to support the vertical transmission of COVID-19, isolation is still obligatory before delivery of mothers with COVID-19 and it should be carefully monitored, and timely supportive treatments should be administered [Citation15]. It is suggested that the baby should be admitted into the isolation units if there are high-risk factors such as fever in the mother, low birth weight, premature rupture of membranes, twins, premature birth or the infant is small for gestational age [Citation15]. However, given the potential harmful effects on feeding and bonding, routine protective isolation of a mother–baby should not be accepted depending on the health status of the mother and baby [Citation17].

All babies born to COVID-19 positive mothers should have suitable monitoring and early neonatal care, where required. Babies born to mothers tested positive for COVID-19 will need neonatal continuing follow-up after discharge [Citation17]. Heart rate, oxygen saturation, blood pressure, respiration, temperature, blood glucose, and gastrointestinal symptoms should always be monitored [Citation32]. The decision for the separation of mother and baby should be made on a case-by-case basis in consultation with clinicians and control specialist [Citation28].

Symptoms are not specific, especially in premature infants [Citation32]. Other findings may include apnea, tachypnea, nasal flaring, grunting, cough, lethargy, tachycardia, poor feeding, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal distension [Citation15,Citation32]. Preliminary evaluation should be based on a decrease or increase in leukocytes counts [Citation32]. Zhang’s study showed that nucleic acid tests on 10 new-born coronavirus swabs were negative [Citation12]. Three neonates were identified with bacterial pneumonia based on history symptoms, sputum culture, procalcitonin, blood routine, C-reactive protein, and imaging examination [Citation12]. All of them recovered after anti-inflammatory management and the three patients were isolated, and follow-up showed no neonatal illness or death [Citation12]. Thrombocytopenia, alkaline phosphatase, elevated levels of kinase, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and lactate dehydrogenase, are other possible findings [Citation32]. Also, radiography or ultrasound of lung is likely to show pneumonia [Citation32]. There is currently neither a vaccine nor specific antiviral drugs to combat the 2019-nCoV infection, and early intravenous injection of immunoglobulin may reduce severe morbidity and mortality [Citation15].

Vertical transmission

Two neonatal cases of COVID-19 infection have been confirmed so far, with one case confirmed at 17 days after birth and the other case confirmed at 36 h after birth and for whom the possibility of close contact history cannot be excluded [Citation6,Citation33,Citation34]. However, no trustworthy evidence is available yet to support the possibility of vertical transmission of COVID-19 infection from the mother–baby [Citation11,Citation22] and babies, whose vital signs were stable, has no fever or cough, but was experiencing shortness of breath. Chest X-rays showed signs of infection along with some anomalies in liver functions [Citation33].

A published study by Chen et al. confirmed all samples were negative for the virus in amniotic fluid, neonatal throat swabs, cord blood and breastmilk samples from infected mothers [Citation8]. Also, in a different paper by Chen et al., three placentas of infected mothers were tested and confirmed negative of the virus [Citation31].

Mother-to-child transmission of respiratory viruses mostly happens via the birth canal and during breastfeeding or close contact among health care providers, family members [Citation15]. To our knowledge, no article has reconnoitered that reporting a newly vertically transmitted case [Citation15].

Breastfeeding

It is comforting that in six cases tested, breastmilk was negative for COVID-19 [8]; however, given the small number of cases, this evidence should be inferred with caution. The main risk for infants of breastfeeding is the close contact with the mother, who is likely to share infective airborne droplets and it is essential to protect and separate the infants immediately after birth for at least 14 days [Citation34,Citation35]. The risks and benefits of breastfeeding and any potential risks of transmission of the virus through breastmilk [Citation17] should be discussed with her [Citation17]. During short-term separation, mothers who intend to breastfeed should be encouraged to express their milk and maintain milk supply [Citation36]. If possible, a dedicated breast pump should be provided. Mothers should practice hand hygiene, prior to expressing breast milk. After each pumping session, all parts that come into interaction with milk should be washed and the entire pump should be sterilized per the manufacturer’s instructions [Citation28]. If the mothers wishes to feed at the breast, she should put on a facemask and practice hand hygiene before each feeding [Citation28]. Infants whose mothers are confirmed of COVID-19 should not be fed from breast milk; but in the suspected or negative diagnosed mother, infants should be fed with breast milk [Citation32]. To support mothers and alleviate their worries due to separation from the baby, it is necessary to consider the mental state of the mothers via early bonding as well as establishment of lactation [Citation21]. Also, human breast milk banks should not use milk from mothers confirmed to be infected with COVID-19 [Citation17,Citation25] and donor milk can be used after being screened for COVID-19 considering the incubation period [Citation32].

Conclusions

Improving quality of care in pregnancy and childbirth, as well as educating, supporting and training healthcare providers in control of infection epidemic need to be prioritized. All countries involved with the virus epidemic must publish their research data and clinical recommendations as a basis for future care until guidelines evolve as more data become available and experience is gathered. Sharing data can help countries that are likely to be affected by the virus epidemic in the future to prevent maternal and neonatal complications associated with the COVID-19.

Ethical approval

Research ethics confirmation (ethics code: IR.MUMS.NURSE.REC.1399.002) for this study was received from the Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their deepest thanks to all librarians who provided them access to information and scientific resources.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO. Global surveillance for COVID-19 disease caused by human infection with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Interim guidance; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/global-surveillance-for-human-infection-with-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. New Eng J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720.

- Schwartz DA, Graham AL. Potential maternal and infant outcomes from (Wuhan) coronavirus 2019-nCoV infecting pregnant women: lessons from SARS, MERS, and other human coronavirus infections. Viruses. 2020;12(2):194.

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395(10223):507–513.

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061.

- Rasmussen SA, Smulian JC, Lednicky JA, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(5):415–426.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement (Chinese edition). J Chin Integr Med. 2009;7(9):889–896.

- Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395(10226):809–815.

- Liu H, Liu F, Li J, et al. Clinical and CT imaging features of the COVID-19 pneumonia: focus on pregnant women and children. J Infect. 2020; 80(5):e7–e13.

- Liu Y, Chen H, Tang K, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy. J Infect. 2020;pii: S0163-4453(20)30109-2. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.028

- Liu W, Wang Q, Zhang Q, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) during pregnancy: a case series. 2020. 202002.0373.v1.

- Zhang L, Jiang Y, Wei M, et al. Analysis of the pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19 in Hubei Province. Zhonghua fu Chan ke za Zhi. 2020;55(0):E009.

- Liu D, Li L, Wu X, et al. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with COVID-19 pneumonia: a preliminary analysis. Available at SSRN 3548758. 2020.

- Wang X, Zhou Z, Zhang J, et al. A case of 2019 novel coronavirus in a pregnant woman with preterm delivery. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;pii: ciaa200. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa200

- Zhu H, Wang L, Fang C, et al. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Transl Pediatr. 2020;9(1):51–60.

- Favre G, Pomar L, Musso D, et al. 2019-nCoV epidemic: what about pregnancies?. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395(10224):e40.

- (RCOG) RCoOaG. Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in pregnancy, information for healthcare professionals; 2020. Available from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/coronavirus-covid-19-virus-infection-in-pregnancy-2020-03-09.pdf.

- Favre G, Pomar L, Qi X, et al. Guidelines for pregnant women with suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;pii: S1473-3099(20)30157-2. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30157-2

- Liang H, Acharya G. Novel corona virus disease (COVID-19) in pregnancy: what clinical recommendations to follow? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(4):439–442.

- Mirzadeh M, Khedmat L. Pregnant women in the exposure to COVID-19 infection outbreak: the unseen risk factors and preventive healthcare patterns. J Maternal–Fetal Neonat Med. 2020:1–2. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1749257

- Chua MSQ, Lee JCS, Sulaiman S, et al. From the frontlines of COVID‐19 – how prepared are we as obstetricians: a commentary. BJOG. 2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16192

- Li Y, Zhao R, Zheng S, et al. Lack of vertical transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(6). DOI:https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2606.200287

- Poon LC, Yang H, Lee JCS, et al. ISUOG Interim Guidance on 2019 novel coronavirus infection during pregnancy and puerperium: information for healthcare professionals. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55(5):700–708.

- Song LXW, Ling K, et al. Anesthetic management for emergent cesarean delivery in a parturient with recent diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). A case report. Transl Perioper & Pain Med. 2020;7(3):234–237.

- Mullins E, Evans D, Viner R, et al. Coronavirus in pregnancy and delivery: rapid review and expert consensus. medRxiv. 2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.06.20032144

- Yang H, Wang C, Poon L. Novel coronavirus infection and pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55(4):435–437.

- The L. Emerging understandings of 2019-nCoV. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395(10221):311.

- CCfDCa. Interim considerations for infection prevention and control of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in inpatient obstetric healthcare settings; 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/inpatient-obstetric-healthcare-guidance.html.

- Capanna F, Haydar A, McCarey C, et al. Preparing an obstetric unit in the heart of the epidemic strike of COVID-19: quick reorganization tips. J Maternal–Fetal Neonat Med. 2020:1–7. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1749258

- CDC. Pregnant women(Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)):frequently asked questions and answers: coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and pregnancy); 3/5/2020. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/specific-groups/pregnancy-faq.html

- Chen S, Huang B, Luo DJ, et al. [Pregnant women with new coronavirus infection: a clinical characteristics and placental pathological analysis of three cases]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49(0):E005.

- Wang L, Shi Y, Xiao T, et al. Chinese expert consensus on the perinatal and neonatal management for the prevention and control of the 2019 novel coronavirus infection. Ann Translat Med. 2020;8(3):47.

- Steinbuch Y. Chinese baby tests positive for coronavirus 30 hours after birth. Available from: https://nypost.com/2020/02/05/chinese-baby-tests-positive-for-coronavirus-30-hours-after-birth/. 2020.

- Qiao J. What are the risks of COVID-19 infection in pregnant women?. Lancet. 2020;395(10226):760–762.

- Yang P, Liu P, Li D, et al. Corona virus disease 2019, a growing threat to children? J Infect. 2020;pii: S0163-4453(20)30105-5. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.024

- Mardani M, Pourkaveh B. A controversial debate: vertical transmission of COVID-19 in pregnancy. Arch Clin Infect Dis. 2020;15(1):e102286.