Abstract

Purpose

Severe hypercalcemia resulting from hyperparathyroidism may result in adverse perinatal outcomes. The objective of this study was to evaluate maternal and neonatal outcomes among pregnant women with hyperparathyroidism using a population database.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project-Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 1999–2015. ICD-9 codes were used to identify women diagnosed with hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy. Perinatal outcomes between pregnant women with and without hyperparathyroidism were compared. Multivariate logistic regression, controlling for age, race, income, insurance type, hospital location, and comorbidities, evaluated the effect of hyperparathyroidism on perinatal outcomes.

Results

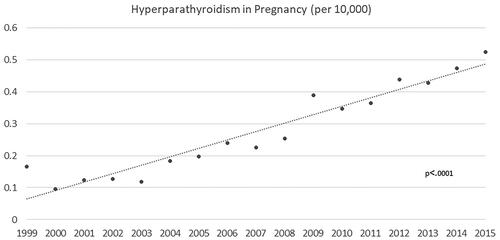

Of 13,792,544 deliveries included over the study period, 368 were to women with hyperparathyroidism. The overall incidence of hyperparathyroidism was 2.7/100,000 births, increasing from 1.6 to 5.2/100,000 births over the study period (p < 0.0001). Women with hyperparathyroidism were older and had more comorbidities, such as obesity, and pre-gestational hypertension and diabetes. Relative to the comparison group, women with hyperparathyroidism were more likely to deliver preterm, OR 1.69 (95% CI 1.24–2.29), to develop preeclampsia, 3.14 (2.30–4.28), and to deliver by cesarean, 1.69 (1.36–2.09). Infants born to mothers with hyperparathyroidism were more likely to be growth restricted, 1.83 (1.08–3.07), and to be diagnosed with a congenital anomaly, 4.21 (2.09–8.48).

Conclusion

Hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy is associated with a significant increase in adverse perinatal outcomes, including preeclampsia, preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, and congenital anomalies. As such, pregnancies among women with hyperparathyroidism should be considered high-risk, and specialized care is recommended in order to minimize maternal and neonatal morbidity.

Introduction

Hyperparathyroidism is among the most common endocrine disorders in the general population, following diabetes and thyroid disorders [Citation1,Citation2]. Hyperparathyroidism among women of childbearing age is rare, with a reported prevalence of 0.05% [Citation3]. Nevertheless, hyperparathyroidism is the most common cause of hypercalcemia during pregnancy, and it is considered a preventable cause of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality [Citation4].

In the majority of cases, hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy is due to primary hyperparathyroidism, with parathyroid adenomas discovered in over 85% of reported cases [Citation3]. The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of elevated serum ionized calcium with elevated or inappropriately normal parathyroid hormone levels [Citation4]. However, the diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy is challenging, as associated symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and fatigue may be dismissed or attributed to other more common pregnancy ailments [Citation3]. Indeed, the diagnosis may be missed in up to 80% of cases [Citation4].

While the majority of prior studies investigating hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy have focused on the medical complications associated with hyperparathyroidism, including nephrolithiasis, pancreatitis, peptic ulcer disease, and mood disorders [Citation4,Citation5], a number of studies have demonstrated an association between hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy and adverse perinatal outcomes [Citation5–8]. However, most of these studies are limited by their small sample size and provide conflicting results. Indeed, while older studies report adverse pregnancy outcomes in up to 80% of cases [Citation5,Citation7], recent studies provide more reassuring statistics, suggesting that perinatal complications may be preventable thanks to advancements in prenatal care of women with such high-risk medical conditions [Citation6,Citation8].

The objective of this study was to evaluate maternal and neonatal outcomes among pregnant women with hyperparathyroidism using a population database, in order to further current understanding of this disorder and its implications during pregnancy.

Materials and methods

Data Source

For this retrospective cohort study, data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project-Nationwide Inpatient Sample (HCUP-NIS) from 1999 to 2015 was used. The HCUP-NIS is a large, publicly available database in the United States, which contains data from more than 7 million hospital admissions yearly, and is designed to capture a representative sample of all hospital discharges [Citation9]. The NIS comprises clinical information extracted from hospital discharge summaries, including patient demographic characteristics, hospital characteristics, expected payment source, and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis, and procedure codes [Citation9].

Study Population

ICD-9 codes were used to identify deliveries among women with hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy. Women with hyperparathyroidism were defined as those with any of the following ICD-9 codes: 25201, 25202, 25203, 25204, 25205, 25206, 25207, 25208, 25209. Pregnant women without any of these codes made up the comparison group.

Statistical Analyses

The overall incidence and annual incidence of hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy over the study period were calculated. A Chi-square goodness of fit test was used to assess the trend over the study period.

Maternal characteristics, including age, race, income, insurance type, hospital location, and comorbidities, such as preexisting diabetes, preexisting hypertension, and obesity, were described for both pregnant women with hyperparathyroidism and pregnant women without hyperparathyroidism. Perinatal outcomes of interest included preeclampsia, eclampsia, placental abruption, venous thromboembolism (VTE), myocardial infarction (MI), post-partum hemorrhage (PPH), transfusion, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), maternal death, cesarean delivery, preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction (FGR), congenital anomalies, and intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD). Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed, controlling for age, race, income, insurance type, hospital location, and comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, and obesity), to evaluate the effect of hyperparathyroidism on perinatal outcomes through estimation of adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Differences between groups were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using the statistical software package SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Of the 13,792,544 deliveries included over the study period, 368 were to women with hyperparathyroidism. The overall incidence of hyperparathyroidism was 2.7 per 100,000 births. As shown in , the prevalence of hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy increased over the study period, from 1.6 per 100,000 births in 1999 to 5.2 per 100,000 births in 2015 (p < 0.0001).

Maternal demographic characteristics among pregnant women with hyperparathyroidism are presented in . Women with hyperparathyroidism were older and had more comorbidities, such as obesity, and pre-gestational hypertension and diabetes. Obstetrical outcomes among women with hyperparathyroidism are presented in . Compared to women without hyperparathyroidism, women with hyperparathyroidism were more likely to deliver preterm, develop preeclampsia, and deliver by cesarean. As shown in , infants born to mothers with hyperparathyroidism were more likely to be growth restricted, and more likely to be diagnosed with a congenital anomaly.

Table 1. Baseline Clinical Characteristics of Pregnant Women with and without Hyperparathyroidism, HCUP-NIS 1999-2015.

Table 2. Obstetrical Outcomes among Women with Hyperparathyroidism.

Table 3. Neonatal Outcomes among Births to Women with Hyperparathyroidism.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy is a rare condition, complicating approximately 3 per 100,000 pregnancies. Hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes, such as preterm delivery, preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, and congenital anomalies.

Our study found that the incidence of hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy is lower than that reported in women of reproductive age (0.0027% vs. 0.05%) [Citation3]. However, it is important to consider the challenges involved in diagnosing this condition during pregnancy specifically, as many women may be asymptomatic, or have symptoms that resemble other more common pregnancy disorders, such as nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, or hyperemesis gravidarum. Furthermore, ionized calcium levels are not routinely measured or included in prenatal bloodwork [Citation3,Citation5]. Therefore, the incidence of hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy may be grossly underestimated, and cases captured by databases such as the NIS may represent mainly the more severe presentations of this disorder, or cases diagnosed only after complications, such as preeclampsia, already developed.

Approximately 15% of women with hyperparathyroidism in our study were diagnosed with preeclampsia, compared with 4% of women without hyperparathyroidism. Previous studies have demonstrated an association between hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and hyperparathyroidism in up to 25–30% of cases [Citation4,Citation10]. It has been suggested that commonalities in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia and primary hyperparathyroidism, including endothelial damage, cardiovascular disorders, and insulin resistance, may explain the association between these conditions [Citation4,Citation6,Citation10].

The risk of preterm delivery among pregnancies complicated by hyperparathyroidism is reported at 13% [Citation4], which is concordant with our results. The increased rate of preterm delivery may be explained by the association of hyperparathyroidism with maternal conditions, which may require preterm delivery, mainly preeclampsia [Citation11], or increase the risk of preterm labor, such as nephrolithiasis [Citation12] and acute pancreatitis[Citation13].

Our study also found an increased rate of cesarean delivery among women with hyperparathyroidism (50% vs. 30%), which is consistent with previous reports [Citation14]. In a large retrospective cohort study by Abood et al., a two-fold increase in the rate of cesarean delivery was found among women with hyperparathyroidism, which was attributed to a lower gestational age at delivery [Citation14]. While maternal hyperparathyroidism does not in itself represent an indication for cesarean delivery, the increased rate of cesarean delivery among patients with hyperparathyroidism may be explained by the increased risk of uncontrolled hypertension, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction, which may necessitate early and/or emergent delivery. Indeed, these conditions are often described in case reports of hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy necessitating cesarean delivery [Citation3,Citation10,Citation15]. In cases where surgical management is indicated to control maternal hyperparathyroidism, concurrent parathyroidectomy at the time of cesarean delivery in the third trimester is described as a safe option [Citation16].

Finally, we found an increased risk of fetal growth restriction and congenital anomalies among pregnancies complicated by hyperparathyroidism. To our knowledge, an association between maternal hyperparathyroidism and congenital anomalies has not previously been described. However, neonatal complications, including neonatal hypocalcemia, fetal growth restriction, and low birthweight have been described among infants born to mothers with hyperparathyroidism [Citation7,Citation10,Citation17]. Fetal growth restriction may be due to premature calcification of the placenta in the context of maternal hyperparathyroidism, bringing forth the recommendation of serial ultrasounds throughout pregnancy in women with known hyperparathyroidism [Citation18]. However, as previously stated, hyperparathyroidism is associated with an increased risk of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Preeclampsia is well-recognized as one of the most common causes of fetal growth restriction and low birthweight, due to decreased uteroplacental blood flow [Citation11]. Therefore, the association of hyperparathyroidism with fetal growth restriction and low birthweight may also be secondary to the well-established pathophysiology of preeclampsia on fetal growth.

Increased awareness of the signs and symptoms of hyperparathyroidism, as well as the associated perinatal risks, is essential. Indeed, due to the sometimes-insidious presentation of this condition, diagnosis may be difficult. Furthermore, many physicians may not be familiar with this rare condition, which may also contribute to underdiagnosis. Early diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy and appropriate treatment may help prevent associated maternal and neonatal complications, providing support for the incorporation of a high index of suspicion and ionized calcium measurements in clinical guidelines.

Our findings suggest the need for specialized follow-up of pregnancies complicated by hyperparathyroidism. In line with previous recommendations, we recommend close follow-up for fetal growth restriction with serial ultrasounds during pregnancy [Citation18]. Furthermore, interdisciplinary collaboration and consultation with neonatology is recommended. Suppression of fetal parathyroid hormone secondary to maternal hyperparathyroidism may result in neonatal hypocalcemia, which is present in up to 50% of cases and is directly related to maternal calcium levels [Citation7]. Neonatal hypocalcemia usually appears within the first two weeks of life and is well managed medically with vitamin D and calcium supplementation [Citation4,Citation5]. However, in rare cases, it can lead to seizures and tetany [Citation17].

Creation of a patient registry for pregnancies complicated by hyperparathyroidism would allow for the identification of a larger number of cases and collection of more detailed information regarding each case, including presenting symptoms, gestational age at diagnosis, and maternal calcium levels. Correlation of maternal and neonatal outcomes with maternal calcium levels would provide a greater understanding of the association between disease severity and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Such information would be invaluable in guiding patient counseling and instituting formal recommendations for obstetrical care.

This population-based study included over 13 million deliveries in the United States and identified 368 deliveries among women with hyperparathyroidism. This large sample enabled us to detect significant differences in outcomes between pregnancies complicated by hyperparathyroidism and a comparison group, where they existed. Most published studies are either small in size or focus on the medical complications associated with hyperparathyroidism, rather than obstetrical and neonatal outcomes. Therefore, our study has contributed to the knowledge base on pregnancy outcomes among women with hyperparathyroidism.

Our study findings are limited by the retrospective nature of the study, as well as the possibility of misclassification of ICD-9 diagnostic codes. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, we were unable to define the severity of hyperparathyroidism among our cases, as this information is unavailable within the NIS database.

Our findings indicate that hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy is rare, but associated with a significant increase in adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes, including preterm delivery, preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, and congenital anomalies. As such, we recommend increased surveillance for pregnancies complicated by hyperparathyroidism, including growth ultrasounds, and specialized interdisciplinary care involving maternal-fetal medicine, endocrinology, and neonatology, in order to minimize maternal and neonatal morbidity.

Ethical approval

This study utilized publicly available data. Therefore, institutional research board approval was not required as per the 2018 Tri-Council Policy Statement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hirsch D, Kopel V, Nadler V, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(5):2115–2122.

- Khan AA, Hanley DA, Rizzoli R, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism: review and recommendations on evaluation, diagnosis, and management. A Canadian and international consensus. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(1):1–19.

- Davis C, Nippita T. Hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(2):e232653.

- Dochez V, Ducarme G. Primary hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(2):259–263.

- Sullivan SA. Parathyroid Diseases. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62(2):347–358.

- Cassir G, Sermer C, Malinowski AK. Impact of perinatal primary hyperparathyroidism on maternal and fetal and neonatal outcomes: retrospective case series. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2020;42(6):750–756.

- Diaz-Soto G, Linglart A, Sénat MV, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy. Endocrine. 2013;44(3):591–597.

- Gehlert J, Morton A. Hypercalcaemia during pregnancy: review of maternal and fetal complications, investigations, and management. Obstet Med. 2019;12(4):175–179.

- HCUP Databases. Health Cost and utilization project (HCUP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Updated September 21, 2021. accessed 22 November 2021. Available from: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp.

- Rigg J, Gilbertson E, Barrett HL, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy: maternofetal outcomes at a quaternary referral obstetric hospital, 2000 through 2015. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(3):721–729.

- Backes CH, Markham K, Moorehead P, et al. Maternal preeclampsia and neonatal outcomes. J Pregnancy. 2011;2011:214365.

- Drescher M, Blackwell RH, Patel PM, et al. Antepartum nephrolithiasis and the risk of preterm delivery. Urolithiasis. 2019;47(5):441–448.

- Hacker FM, Whalen PS, Lee VR, et al. Maternal and fetal outcomes of pancreatitis in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):568.e1-5–568.e5.

- Abood A, Vestergaard P. Pregnancy outcomes in women with primary hyperparathyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;171(1):69–76.

- Gokkaya N, Gungor A, Bilen A, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy: a case series and literature review. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32(10):783–786.

- Trebb C, Wallace S, Ishak F, et al. Concurrent parathyroidectomy and caesarean section in the third trimester. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36(6):502–505.

- Norman J, Politz D, Politz L. Hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy and the effect of rising calcium on pregnancy loss: a call for earlier intervention. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2009;71(1):104–109.

- Graham EM, Freedman LJ, Forouzan I. Intrauterine growth retardation in a woman with primary hyperparathyroidism. A Case Report. J Reprod Med. 1998;43(5):451–454.