Abstract

Objectives

To estimate clinical effects of emergency cervical cerclage in twin pregnancies with cervical dilation ≥1.0 cm in mid-trimester of gestation and to identify risk factors after cerclage.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included 99 twin pregnancies with cervical dilation ≥1cm in the mid-trimester of gestation at three institutions, from December 2015 through December 2021. The cases were treated with emergency cervical cerclage (52 cases) or expectant management (47 cases). Compare the pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of the two groups. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to determine the independent risk factors associated with cerclage.

Results

Cerclage placement was associated with significantly longer gestation age and prolongation of the gestational latency (p < .05). In the cases, compared to expectant treatments, spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB) at <26, <28, <30, <32 weeks was significantly less frequent (p < .05). Pre-operation WBC > 11.55 × 109/L, CRP > 10.1 and cervical dilation >3.5 cm were found to be independent risk factors for delivery 28 weeks after cerclage.

Conclusions

Cervical cerclage in twin pregnancies with cervical dilation ≥1.0 cm in mid-trimester of gestation may prolong pregnancy and gestation age, and improve pregnancy and neonatal outcomes compared with expectant management. The strongest predictor of sPTB before 28 weeks after ECC were pre-operation WBC >11.55 × 109/L, CRP > 10.1 and cervical dilation >3.5 cm.

Introduction

The twin birth rate in China has steadily increased over the last decade. During 2007–2014, the twinning rate increased by 32.3% from 16.4 to 21.7 per 1000 total births [Citation1], mostly because of increasing maternal age and the associated widespread use of assisted reproductive technology [Citation2]. Twins are associated with 50% incidence of preterm birth (PTB), an increased risk for low birth weight (LBW), and a five times higher risk of neonatal death than singletons [Citation3,Citation4]. The most important risk factor for PTB in twins is short cervical length prior to 24 weeks [Citation5–7], pregnancies with cervical dilation ≥1cm in the second trimester are associated with a poor prognosis, and greater than 90% will result in PTB [Citation8,Citation9]. Although multiple interventions have been evaluated for prolonging these gestations and improving outcomes, none have shown a substantial effect [Citation10,Citation11]. Moreover, since the occurrence mechanism of spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB) is different between twin and singleton pregnancies [Citation12], preventive measures should be treated differently.

The use of cervical cerclage in twin pregnancies is not generally supported, whereas it is widely accepted in singleton pregnancies. The guidelines developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [Citation13] in 2014 and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists [Citation14] in 2017 do not recommend cervical cerclage for twin pregnancies. In 2019, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC) suggested an advantage to cerclage in a subset of these patients when the cervix was dilated to 1 cm or more [Citation8].

Cervical cerclage represents one of the best-commonly surgical interventions to prevent sPTB in obstetrics. In twins, the data on the efficacy of emergency cervical cerclage (ECC) is limited. Several new studies have shown promising results of significant prolongation of twin pregnancy with the use of ECC compared with those without cerclage [Citation15–17]. While the technique has been widely studied and evaluated, controversy remains regarding certain aspects of the therapeutic indication and complementary management tests to be performed. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to evaluate pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in twin pregnancies, in which a cervical cerclage was placed to a dilated cervix in mid-trimester of gestation and to find the factors affecting the clinical effects of emergency cerclage.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

In this retrospective cohort study of twin pregnancies, the study group comprised all women with asymptomatic cervical dilation of the internal os 1 cm or more at 18–26 weeks of gestation from December 2015 to December 2021 and who attended the Women’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Huzhou Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, and The First People’s Hospital of Fuyang Hangzhou. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each participating institution.

The decision to perform cerclage was made by patients after consultation with the attending physician. The attending physicians were senior obstetricians and their fixed team, and their recommendations were based on the clinical characteristics of each patient rather than the physician’s preferences. All the patients were informed of the potential benefits and risks of emergency cerclage and signed informed consent. Criteria for inclusion in the study were women with twin gestations who presented between 18 and 26 weeks of pregnancy with painless cervical dilation of 1–6 cm. The exclusion criteria included the following: fetuses with structural or chromosomal abnormalities, history of multifetal pregnancy reduction to twins at >14 weeks, medically indicated PTB (twin-twin transfusion syndrome, severe preeclampsia, placental abruption, preterm premature rupture of membranes [PPROM], or placenta previa), and cerclages placed for other indications (history-indicated cerclage or ultrasound-indicated cerclage). Patients who did not deliver in the study hospital or were lost to follow-up by telephone were also excluded.

Interventions

All cerclage procedures were performed under spinal anesthesia via the McDonald technique (transvaginal cerclage with two 1-0 non-absorbable sutures placed at the cervicovaginal junction, but without bladder mobilization). In cases of bulging membranes beyond the external cervical os, a Cooker catheter was introduced into the cervical canal and the balloon at the top of the catheter was filled with 10-20 ml of saline solution in order to retract the membranes prior to cerclage placement. The preoperative evaluation included assessment of vaginal bleeding or discharge, serum white blood cell (WBC) count and C-reactive protein (CRP) level, clinical chorioamnionitis, and uterine contractions. An isolated finding of vaginal discharge was evaluated for a definitive diagnosis and antibiotics were used for at least 48 h empirically according to a drug sensitivity test. Patients tested positive for chlamydia and their sexual partners were treated. Active labor was defined as the presence of regular uterine contractions 3 or more in 10 min with the cervical shortened or dilated. Clinical chorioamnionitis was defined as maternal fever of ≥38° C with one of the following conditions: maternal tachycardia (>100 beats/minute), fetal tachycardia, (>160 beats/minute), WBC >15 × 103/L, or uterine tenderness. Evidence of clinical chorioamnionitis was a contraindication for cerclage. Before cerclage placement, all the patients were observed for 12–24 h to ensure that cervical dilation was not the result of active labor, or any evident clinical signs of infection. Preoperative prophylactic antibiotics and perioperative indomethacin and nifedipine were administered and continued 48 h postoperatively.

For women managed expectantly, they were given prophylactic intravenous tocolysis (magnesium sulfate or ritodrine or atosiban) for 48 h and given oral tocolysis (nifedipine, ritodrine) at least 7 days after stabilization.

Medical data

The following variables were collected from patient medical records: maternal age, parity, pregestational body mass index (BMI), use of in vitro fertilization, chorionicity maternal major comorbidities including pregnancy-associated hypertensive disorders and gestational diabetes mellitus, manipulation of membranes during the cerclage, cervical dilation in cm, GA at the time of cervical dilation, GA at the time of cerclage, PPROM, GA at delivery, the interval from diagnosis of cervical dilation to delivery, rate of sPTB. Neonatal outcomes included birth weight, Apgar score at 5 min, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and neonatal survival at discharge.

GA was determined by evaluating the last menstrual period and crown–rump length measurement on an early ultrasound. Chorionicity was determined by early ultrasound. Cervical dilation was determined by pelvic exam between 18 and 28 weeks.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome was GA at delivery. The main secondary outcomes were as follows: maternal outcomes of pregnancy latency, rate of sPTB at <26, <28, <30, and <32 weeks; and neonatal outcomes of birthweight, 5-min Apgar score >7, and admission to the NICU.

Sample size calculation

The calculation of sample size was based on the primary outcome measure of GA at delivery was 23.46 ± 3.79 in the expectant management group then 29.35 ± 4.56 in the cerclage group19, with a power of 90%. To detect this difference at a significance level of 5%, we calculated 36 subjects with 18 subjects in each arm, plus 10% for loss of follow-up. A total sample size of 40 subjects was needed. Based on the secondary outcome measure the rate of sPTB at <32 weeks was from 97.4% in the no cerclage group to 62.1% in the cerclage group, with a power of 90%. To detect this difference at a significance level of 5%, we calculated 62 subjects with 36 subjects in each arm, plus 10% for loss of follow-up. A total sample size of 80 subjects was needed with 40 subjects in each arm.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows, version 25.0. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 indicated statistical significance. Frequencies (percentages), means (standard deviation) and median (interquartile range), are presented. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact tests. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t test (for normally distributed data) or Mann–Whitney’s U test (for non-normal distribution). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed and the area under the curve (AUC) was used to compare the predictive value for adverse pregnancy outcomes after cerclage (GA at delivery <28 weeks after cerclage). Youden index was used to screen the best cutoff value. Multivariate analysis was performed using a Logistic regression analysis model to verify the risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes after cyclization. Multivariable logistic regression, presented as adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI), was performed to identify risk factors associated with sPTB by adjusting for potential confounding factors (maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, GA at cervical dilatation, preoperative WBC, and preoperative CRP). Kaplan–Meier curves were generated for GA at delivery according to treatment differences (ECC or expectant management) using a log–rank test in order to estimate the risk of sPTB.

Results

In total, 52 twin pregnancies in the study with cervical dilation 1–6 cm at 18–26 weeks of gestation underwent cerclage. The median GA at the time of cerclage placement was 22.77 weeks and median cervical dilation at diagnosis was 2 cm. Technical success was achieved in all patients, with no immediate procedure-related complications. No iatrogenic PPROM occurred, and all patients who underwent cerclage experienced intraoperative bleeding of <100 ml.

Maternal and neonatal outcomes

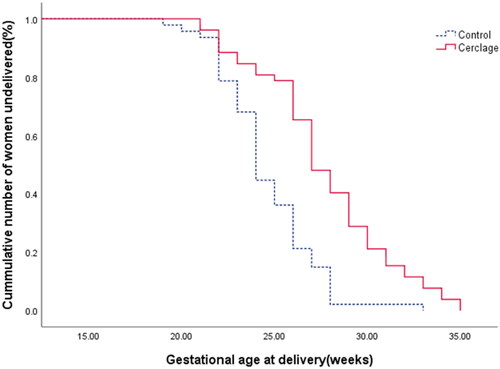

We identified 101 women with twin pregnancies and asymptomatic cervical dilation 1–6 cm by physical exam. We could not perform emergency cerclage on two women who had ruptured membranes before the surgery. 52 women underwent ECC and 47 controls managed expectantly. Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics were similar between the two groups (). Perinatal outcomes are described in . Analysis was adjusted for maternal age, pregestational BMI, GA at diagnosis of cervical dilatation, WBC and CRP value of twin pregnancies at diagnosis of cervical dilatation. Compared with the expectant management group, GA at delivery was significantly higher (27.71 ± 3.62 vs 24.62 ± 2.56 weeks, aOR: 2.477, 95%CI: 1.632–3.757, p < 0.001) and median pregnancy latency was significantly longer (25 vs 7 days, aOR:1.178, 95%CI:1.092–1.271, p < 0.001) in the ECC group. ECC was associated with significantly lower incidence of sPTB at <26 weeks (21.2% vs 63.8%, aOR:0.009, 95%CI:0.001–0.069, p < .001), <28 weeks (51.9% vs 85.1%, aOR:0.082, 95%CI:0.022–0.308, p < .001), <30 weeks (71.2% vs 97.9%, aOR:0.041, 95%CI:0.005–0.368, p = .004), and <32 weeks (84.6 vs 97.9%, aOR:0.102, 95%CI:0.011–0.915, p = .041). The Kaplan–Meier curves in shows that the cumulative percentage of patients with delayed birth was significantly higher in ECC group than in the expectant management group. The log-rank test showed a significant increase in pregnancy prolongation for the ECC group compared with that for the expectant management group (p = .001). However, the incidence of PPROM at <34 weeks and placental abruption were not significantly different. Neonatal outcomes are described in . Among the 84 neonates born alive in the cerclage group vs 24 in the expectantly.

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier curves were generated for gestational age at delivery with cervical dilation ≥1cm. Comparison of cerclage and expectant management(control) using log-rank test showed significant difference (p = 0.001).

Table 1. Maternal and pregnancy characteristics.

Table 2. Perinatal outcomes of twin pregnancies with cervical dilation ≥1cm.

Table 3. Neonatal characteristics and outcomes.

Neonatal birth weight was significantly heavier in the ECC group than in the expectant management group (1022.5 vs 655 g, aOR: 1.008, 95% CI: 1.004-1.011, p < .001). There was a significantly lower incidence of Appgar score >7 in 5 min and ultra-low birth weights in ECC group than in expectantly. (p < .001).

Maternal outcomes with GA at diagnosis between 24-26 weeks

In our study, there were 43 twin pregnancies with GA at diagnosis past 24 weeks: 20 women underwent cerclage and 23 had no cerclage. The GA at delivery in the ECC group was significantly higher (28.80 ± 2.63 vs 26.39 ± 1.47 weeks, p = .001) and median pregnancy latency was significantly longer (23 vs 8 days, p < .001) than in the expectant management group. The ECC group had a significantly lower incidence of sPTB at <26, <30 and <32 weeks (p < .05) ().

Table 4. Pregnancy outcomes with GA at diagnosis passed 24 weeks.

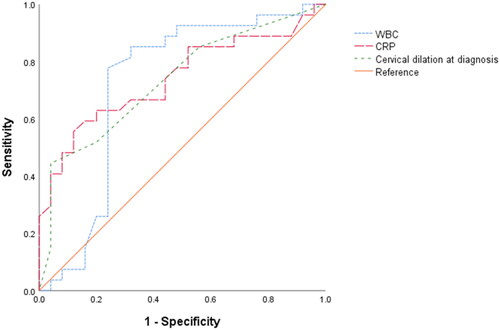

Risk factors associated with sPTB before 28 weeks after cerclage

Among 52 patients who underwent ECC, 27 (51.9%) had an sPTB before 28 weeks. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the association of risk factors for sPTB before 28 weeks (). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed and the area under the curve (AUC) was used to compare the predictive value and determine the cutoff value. And we found that preoperative WBC (AUC = 0.721, 95%CI = 0.566–0.875, p = .006), CRP (AUC = 0.741, 95%CI = 0.604-0.877, p = .003), and cervical dilatation at diagnosis (AUC = 0.734, 95%CI = 0.598-0.871, p = .004) had predictive values, and the ROC curve was shown in . Youden index was used to screen the optimal cutoff value. The optimal cutoff value was WBC: 11.55*109/L, CRP: 10.1 and cervical dilatation: 3.5 cm. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the association of risk factors for sPTB before 28 weeks (). White blood cell (WBC)>11.55*109/L and CRP >10.1 at diagnosis and cervical dilation at least 3.5 cm were independently associated with increased odds of sPTB before 28 weeks.

Figure 2. ROC curves of the predictors for delivery at <28 weeks of gestation in the emergency cervical cerclage group.

Table 5. Multivariable analysis of risk factors associated with sPTB before 28 weeks after ECC placement Risk factors OR 95% CI.

Comment

Several findings are notable from this retrospective cohort study of twin pregnancies with asymptomatic cervical dilation of the internal os 1 cm or more at 18–26 weeks of gestation. First, when cervical dilation 1–6 cm, cerclage placement is of benefit, with 33.2% reduction in sPTB before 28 weeks, significant prolongation of latency (by nearly 4 weeks), higher GA at delivery, higher birth weight, lower perinatal mortality than with expectant management, even after controlling for potential confounders. Second, WBC > 11.55 × 109/L, CRP > 10.1 before cerclage and cervical dilation >3.5 cm were the major predictors of sPTB 28 weeks after cerclage. Third, our study supports ECC in twin pregnancy can up to 26 weeks gestation.

Recently, a few retrospective cohort studies [Citation17–21] have presented favorite outcomes with ECC placement when cervical dilation ≥1 cm in twin pregnancies compared with expectant management for pregnancy prolongation of 3–7 weeks and significantly reduce the rate of PTB. However, all studies lacked an expectant management group and had very small sample sizes of twin pregnancy. In 2020 Mian Pan et al. [Citation22] conducted a retrospective cohort study and presented that ECC in twin pregnancies was associated with significantly prolong pregnancy by 5 weeks and the interval from diagnosis to delivery was increased with cerclage by a mean difference of 4.37 weeks, decreased incidence of sPTB at any given GA, and improved perinatal outcome compared with no cerclage. And at the same year, Roman et al. [Citation23] published a small randomized controlled trial (n = 17) comparing ECC versus control in twin pregnancies with cervical dilation of 1–4 cm showed favorable pregnancy outcomes that ECC can prolong pregnancy by 5.6 weeks and decrease the incidence of sPTB before 28 weeks by 50%. Our results are consistent with those studies. But in our study, pregnancy latency in two groups was less than in their studies, and in the expectant management group that was only 7 days from diagnosis to delivery interval, It can be explained from the following aspects: Firstly, the GA at diagnosis was nearly 23 weeks of gestation, and all of the previous researches were 20 weeks of gestation; secondly, in our study, cervical dilation was 1–6 cm, and about half of cases with amniotic membrane prolapse beyond external os which has extremely high risk of sPTB [Citation24–26]. Thus in the study of Abbasi’s et al. [Citation16] the GA at diagnosis in controls was 23.2 weeks and the pregnancy latency was 0.5 weeks which was similar to ours.

At present, most prior publications and guidelines on cervical cerclage suggest that the GA of cervical cerclage is up to 24 weeks of gestation. However, in clinical practice, prolongation of gestation can significantly improve neonatal prognosis and reduce perinatal mortality for women with asymptomatic cervical dilation of the internal os ≥1 cm or prolapsed membranes up to the external os at 24-26 weeks of gestation. In our study, 43 twins were diagnosed with GA between 24 and 26 weeks. According to the study, the GA at delivery and pregnancy latency in ECC group were significantly longer than those of the expectant treatment group (p < .05), and the incidence of sPTB at <28. <30. <32 weeks were significantly lower (p < .05). Our study is the first to propose that the GA of ECC in twin pregnancies can be extended to 26 weeks. And, in 2022, the Royal College of Obstetricians Gynaecologists [Citation27] suggested that ECC as a salvage measure in the case of premature cervical dilatation with exposed fetal membranes in the vagina can be considered up to 27 + 6 weeks gestation. Due to the small sample size in twin pregnancies that were past 24 weeks that cerclage placement in our research, more large sample studies are needed to confirm this conclusion.

The currently available literature lack of evidence for cervical dilation of 4 cm or more, and in 2019, SOGC [Citation8] suggested ECC may be considered in women in whom the cervix has dilated to < 4 cm without contractions, because the larger the cervical dilatation, the higher the difficulty of the operation and the higher the risk of failure. The only published study comparing cerclage in twin pregnancies with cervical dilation 4–6 cm and prolapsed membranes showed an overall positive effect on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes by prolonging pregnancy with 19 days and promoting a three-fold reduction in sPTB before 28 weeks [Citation24], which indirectly supported a potential benefit of cerclage in twin pregnancies with cervical dilation in 4 cm or more. In our study, the cervical dilation was 1-6cm and 50% of cases with amniotic membranes prolapsed beyond the external os. And our conclusions were consistent with Chanjuan Zeng’s and we believed that in the urgent situation of cervical dilation of 4 -6cm and bulging membranes, cerclage may be the only hope for prolonging gestation until fetal viability.

We further identified that White blood cell (WBC)>11.55 × 109/L and CRP >10.1 before cerclage and cervical dilation at least 3.5 cm were independently associated with increased odds of sPTB before 28 weeks. One of the key findings of our study is that cervical dilatation >3.5 cm is an independent predictor of cerclage failure, which is consistent with previous reports [Citation24,Citation25, Citation28,Citation29]. Particularly, we proposed for the first time that higher WBC and CRP before the operation were independent risk factors for predicting the possibility of cerclage failure. Therefore, early and accurate identification of those women by affirmative interventions for example prophylactic antibiotics was important to improve pregnancy outcomes. In our study, all women who received ECC also received antibiotics, indomethacin and nifedipine, this management is similar to previous studies [Citation11, Citation21, Citation30–32]. The available evidence is insufficient to recommend the use of prophylactic antibiotics, indomethacin and nifedipine, for all women with cervical cerclage. Further research is needed to evaluate the efficacy and synergy of each treatment.

Our study was careful to identify and treat, where possible, confounders for PTB. Multiple studies [Citation33–35] have reported an association between PTB and various urogenital tract infections, such as mycoplasma, chlamydia and other positive cervical culture. In our study, 21/99 participants (21.21%) exhibited colonization by mycoplasma: 13 in the ECC group and 8 in the expectant management group, and all women with mycoplasma or chlamydia were treated with azithromycin. Chanjuan Zeng et al. [Citation24] indicated that positive vaginal culture was the predictor of sPTB 28 weeks after cerclage. It is not known whether positive cervical culture is the cause of cervical dilation or its result. However, waiting for cultural results may not be a viable decision for these women, as most of them may be delivered within 1 week without intervention. Therefore, adequate preoperative vaginal disinfection is especially important for patients who underwent cerclage.

The strengths of our study are that it is a multicenter retrospective cohort study of patients with twin pregnancies treated with ECC or expectant treatment at mid-term for cervical dilation and prolapsed membranes. There is no prior dedicated multicenter retrospective cohort in this population. Despite the small sample size, we were able to show a significant benefit of ECC in twin pregnancies. Furthermore, our study is the first to suggest that cervical cerclage placement may be extended to 26 weeks of gestation. And we proposed for the first time that higher WBC and CRP before the operation were independent risk factors for predicting sPTB 28 weeks after cerclage. The retrospective nature represents a limitation of this study, but considering the ethical aspects, a prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) study would be unfeasible, especially for women with cervical dilation ≥1cm and prolapsed membrane, which indicates imminent delivery without intervention. Our retrospective cohort study will provide important data available on which to make management decisions and improve the prognosis of twin pregnancies with painless cervical dilatation in the second trimester. In future research, we will develop a scoring system for predicting the effect of cerclage placement for each high-risk woman.

Conclusions

Cerclage in twin pregnancies with cervical dilation ≥1cm and prolapsed membranes may reduce the rate of sPTB and improve perinatal and neonatal outcomes compared with expectant management even in women with cervical dilation of 4 cm or more. It is worth noting that ECC in twin pregnancies can be up to 26 weeks gestation. And before cerclage, the clinician should consider enhanced surveillance of these predictors (WBC > 11.55 × 109/L, CRP >10.1 and cervical dilation >3.5 cm) and subsequently provide active interventions to improve the outcome.

Ethical statement

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Women Hospital, 293 Zhejiang University, School of Medicine in Hangzhou (IRB-20200044-R on May 21, 294 2020) and has been carried out according to the declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Staff at Women’s Hospital, Zhejiang University for technical assistance and facility support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Deng C, Dai L, Yi L, et al. Temporal trends in the birth rates and perinatal mortality of twins: a population-based study in China. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0209962.

- Berveiller P, Rousseau A, Rousseau M, et al. Risk of preterm birth in a twin pregnancy after an early-term birth in the preceding singleton pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2020;127(5):591–598.

- Huang X, Saravelos SH, Li TC, et al. Cervical cerclage in twin pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;59:89–97.

- Roman A, Ramirez A, Fox NS. Prevention of preterm birth in twin pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2022;4(2):100551.

- El-Gharib MN, Albehoty SB. Transvaginal cervical length measurement at 22- to 26-week pregnancy in prediction of preterm births in twin pregnancies. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(6):729–732.

- Pagani G, Stagnati V, Fichera A, et al. Cervical length at mid-gestation in screening for preterm birth in twin pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(1):56–60.

- Kindinger LM, Poon LC, Cacciatore S, et al. The effect of gestational age and cervical length measurements in the prediction of spontaneous preterm birth in twin pregnancies: an individual patient level meta-analysis. BJOG. 2016;123(6):877–884.

- Brown R, Gagnon R, Delisle MF. No. 373-cervical insufficiency and cervical cerclage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41(2):233–247.

- Kaur J, Sarkar A, Rohilla M. Physical examination-indicated cerclage in twin pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(1):131–132.

- Multifetal gestations: twin, triplet, and higher-order multifetal pregnancies: ACOG practice bulletin, number 231. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e145–e162.

- Qureshey EJ, Quinones JN, Rochon M, et al. Comparison of management options for twin pregnancies with cervical shortening. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(1):39–45.

- Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, et al. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371(9606):75–84.

- ACOG practice bulletin no.142: cerclage for the management of cervical insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:372–379.

- Sperling JD, Dahlke JD, Gonzalez JM. Cerclage use: a review of 3 national guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2017;72(4):235–241.

- Han MN, O’Donnell BE, Maykin MM, et al. The impact of cerclage in twin pregnancies on preterm birth rate before 32 weeks. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32(13):2143–2151.

- Abbasi N, Barrett J, Melamed N. Outcomes following rescue cerclage in twin pregnancies(). J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31(16):2195–2201.

- Wei M, Yang Y, Jin X, et al. A comparison of pregnancy outcome of emergency modified transvaginal cervicoisthmic cerclage performed in twin and singleton pregnancies. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;303(5):1197–1205.

- Cilingir IU, Sayin C, Sutcu H, et al. Emergency cerclage in twins during mid gestation may have favorable outcomes: results of a retrospective cohort. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2018;47(9):451–453.

- Barbosa M, Bek Helmig R, Hvidman L. Twin pregnancies treated with emergency or ultrasound-indicated cerclage to prevent preterm births. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(19):3227–3232.

- Chun SH, Chun J, Lee KY, et al. Effects of emergency cerclage on the neonatal outcomes of preterm twin pregnancies compared to preterm singleton pregnancies: a neonatal focus. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0208136.

- Freegard GD, Donadono V, Impey LWM. Emergency cervical cerclage in twin and singleton pregnancies with 0-mm cervical length or prolapsed membranes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(11):2003–2008.

- Pan M, Zhang J, Zhan W, et al. Physical examination-indicated cerclage in twin pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;303(3):665–676.

- Roman A, Zork N, Haeri S, et al. Physical examination-indicated cerclage in twin pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(6):.

- Zeng C, Fu Y, Pei C, et al. Pregnancy outcomes and factors affecting the clinical effects of emergency cerclage in twin pregnancies with cervical dilation and prolapsed membranes. Intl J Gynecology & Obste. 2022;157(2):313–321.

- Pan M, Fang JN, Wang XX, et al. Predictors of cerclage failure in singleton pregnancies with a history of preterm birth and a sonographic short cervix. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;156(2):316–321.

- Miller ES, Rajan PV, Grobman WA. Outcomes after physical examination-indicated cerclage in twin gestations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(1):e41-45–46.e5.

- Shennan AH, Story L. Cervical cerclage: green-top guideline no. 75 febuary 2022: green-top guideline no. Bjog. 2022;129(7):1178–1210.

- Bigelow CA, Naqvi M, Namath AG, et al. Cervical length, cervical dilation, and gestational age at cerclage placement and the risk of preterm birth in women undergoing ultrasound or exam indicated Shirodkar cerclage. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(15):2527–2532.

- Chen R, Huang X, Li B. Pregnancy outcomes and factors affecting the clinical effects of cervical cerclage when used for different indications: a retrospective study of 326 cases. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;59(1):28–33.

- Fichera A, Prefumo F, Mazzoni G, et al. The use of ultrasound-indicated cerclage or cervical pessary in asymptomatic twin pregnancies with a short cervix at midgestation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98(4):487–493.

- Wu FT, Chen YY, Chen CP, et al. Outcomes of ultrasound-indicated cerclage in twin pregnancies with a short cervical length. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;59(4):508–513.

- Premkumar A, Sinha N, Miller ES, et al. Perioperative use of cefazolin and indomethacin for physical examination-indicated cerclages to improve gestational latency. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(6):1409–1416.

- Hitti J, Garcia P, Totten P, et al. Correlates of cervical Mycoplasma genitalium and risk of preterm birth among Peruvian women. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(2):81–85.

- Rittenschober-Böhm J, Waldhoer T, Schulz SM, et al. Vaginal ureaplasma parvum serovars and spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(6):594.e591–594.e599.

- Kataoka S, Yamada T, Chou K, et al. Association between preterm birth and vaginal colonization by mycoplasmas in early pregnancy. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(1):51–55.