Abstract

Objective

Individuals who deliver preterm are disproportionately affected by severe maternal morbidity. Limited data suggest that indicator-specific maternal morbidity varies by gestational age at delivery. We sought to evaluate the relationship between gestational age at delivery and the incidence of severe maternal morbidity and indicator-specific severe maternal morbidity.

Methods

We used a hospital administrative delivery database to identify all singleton deliveries between 16 and 42 weeks gestation from 2002 to 2018. We defined severe maternal morbidity as the presence of any International Classification of Disease diagnosis or procedure codes outlined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, intensive care unit admission, and/or prolonged postpartum hospital length of stay. Indicator-specific severe maternal morbidity was based on the diagnosis and procedure codes and was characterized across gestational age epochs. We categorized gestational age into three epochs to capture extremely preterm birth (less than 28 weeks gestation), preterm birth (28-36 weeks gestation) and term birth (37 weeks gestation and above). Multivariable binomial regression was used to assess the association between categories of gestational age at delivery and severe maternal morbidity adjusting for confounders including age, race, body mass index (BMI), insurance status, and preexisting hypertension or diabetes.

Results

Severe maternal morbidity occurred in 2.5% of all deliveries. The unadjusted incidence of severe maternal morbidity by gestational age epoch was 12% at less than 28 weeks gestation, 8.4% at 28 to 36 weeks of gestation, and 1.7% at greater than or equal to 37 weeks gestation. After controlling for potential confounders the predicted probability of severe maternal morbidity was 16% (95% CI 14,17%) at 24 weeks compared to 2.2% (95% CI 2.1,2.3%) at 38 weeks. Sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, mechanical ventilation, and shock were the most common diagnostic codes in deliveries less than 28 weeks gestation. Heart failure and cardiac arrhythmias were more common in patients with severe maternal morbidity delivering at term.

Conclusion

A high proportion of severe maternal morbidity occurred in preterm patients, with the highest rates occurring at less than 28 weeks gestation. Individuals with severe maternal morbidity who deliver preterm had distinct indicators of morbidity compared to those who deliver at term.

Introduction

Severe maternal morbidity is any unexpected pregnancy outcome resulting in short or long-term maternal complications and it is frequently used as a proxy for maternal mortality [Citation1,Citation2]. Severe maternal morbidity is also an important indicator of maternal health on its own [Citation3–5]. Rates of severe maternal morbidity continue to rise and affect approximately 2% of all deliveries in the United States [Citation1,Citation6–8]. Furthermore, 40% of people who experience severe maternal morbidity deliver before 37 weeks of gestation [Citation9,Citation10].

Despite a robust association between preterm delivery and severe maternal morbidity, there are data on the incidence of severe maternal morbidity along the continuum of gestational age. Additionally, information on indicator-specific severe maternal morbidity between preterm and term deliveries is limited [Citation9–11]. One prior large population-based study of live birth in California (2007–2012) identified hemorrhage and cardiac conditions as the leading causes of severe maternal morbidity in both preterm and term deliveries. Interestingly, during the delivery hospitalization, acute respiratory distress syndrome, eclampsia, acute renal failure, and sepsis were more common with preterm severe maternal morbidity compared to term severe maternal morbidity. This study, however, evaluated all preterm severe maternal morbidity together and it is likely that both the incidence of severe maternal morbidity varies by gestational age and that the causes/indicators of maternal morbidity may vary by extremely preterm versus later preterm birth. Additionally, in the California study, multiple gestations accounted for a third of the pregnancies that had severe maternal morbidity preterm. Given that severe maternal morbidity may differ between multiple gestations and singletons (e.g. twins more likely to have hemorrhage and hypertensive complications), these results may not apply to singleton pregnancies.

The current literature leaves gaps in our understanding of the magnitude of risk and the indicators of preterm severe maternal morbidity compared to term morbidity. Given this, we sought to determine the incidence of severe maternal morbidity across gestational age and describe indicator-specific etiologies of severe maternal morbidity among singleton pregnancies born extremely preterm, late preterm and at term.

Materials and methods

Study population

We identified all singleton deliveries from 16 to 42 weeks gestation from 2002 to 2018 at our institution (n = 153,867) using a hospital delivery database. We excluded cases where severe maternal morbidity diagnostic codes or gestational age at delivery data were missing (n = 1143, 0.7%). The database contains detailed delivery data regarding maternal, fetal, and neonatal outcomes from admitting services, electronic medical record diagnosis and procedure codes, medical record abstraction, electronic birth record, and laboratory data. Database administrators clean and validate data against medical records. The Human Resource Protection Office approved this study (STUDY19030089).

Severe maternal morbidity

Severe maternal morbidity was defined by the presence of at least one of the following: any of the 21 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) International Classification of Disease (ICD) diagnosis or procedure code, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, or prolonged postpartum hospital length of stay (>3 standard deviations from the mean for a mode of delivery). This multi-level definition of severe maternal morbidity performed well against a gold standard case definition from chart review [Citation1,Citation4,Citation12]. Indicator-specific severe maternal morbidity was determined by evaluating frequencies of individual ICD diagnostic or procedure codes for different gestational age categories. We were unable to assess the indicator of severe anesthesia complication due to changes in this variable coding over the course of the study time period.

Analysis

We divided gestational age into three categories: less than 28 weeks gestation, 28–36 weeks gestation, and 37 weeks gestation or greater. Gestational age at our institution is determined according to criteria defined by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [Citation13]. To estimate the independent association between gestational age as a continuous variable and severe maternal morbidity, we used a multivariable binomial regression. Given the CDC criteria for severe maternal morbidity include a procedure code for blood transfusion and blood transfusion alone has a low sensitivity for true severe maternal morbidity we also considered non-transfusion-related severe maternal morbidity. We used theory-based causal diagrams to identify confounders that we included in the model. Confounders included age, race, insurance status, marital status, parity, and preexisting hypertension or diabetes. After modelling, we estimated predicted probabilities of severe maternal morbidity along the continuum of gestational age with marginal standardization.

Results

Severe maternal morbidity occurred in 2.5% of all singleton deliveries (n = 152,724). A total of 1.8% of the cohort (n = 2719) experienced a non-transfusion-related severe maternal morbidity. People with severe maternal morbidity were more likely to be unmarried, identify as non-Hispanic Black, have public insurance, have preexisting conditions, and pregnancy-induced hypertension. Deliveries with severe maternal morbidity were more often a cesarean birth ().

Table 1. Maternal characteristics in deliveries with and without severe maternal morbidity stratified by gestational age.

The incidence of severe maternal morbidity varied markedly by gestational age. Severe maternal morbidity complicated 12% of deliveries less than 28 weeks (n = 256), 8.4% of deliveries from 28 to 36 weeks (n = 1239), and 1.7% of deliveries at term (n = 2247). Average maternal age and parity were similar across gestational age categories. Patients who delivered at less than 28 weeks with severe maternal morbidity were more likely to identify as non-Hispanic Black and have public insurance compared with individuals with severe maternal morbidity who delivered later in gestation. Preexisting diabetes occurred most frequently in pregnancies delivered at 28–36 weeks (11%). Notably, preexisting hypertension occurred in 20% of all preterm pregnancies with severe maternal morbidity compared with 7% of deliveries that occurred term with severe maternal morbidity.

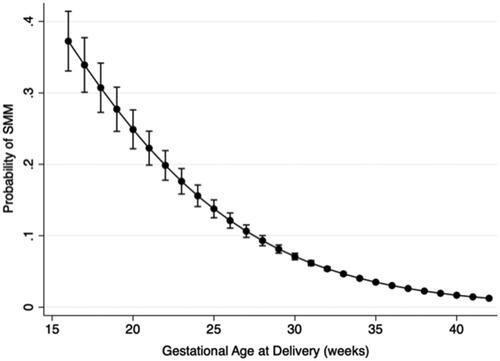

After adjustment for age, parity, race, insurance status, and preexisting conditions, as gestational age increased the predicted probability of severe maternal morbidity decreased in a non-linear manner (). For example, the predicted probability of severe maternal morbidity at 24 weeks was 16% (95% CI 14,17%) compared to 5.4% (95% CI 5.1, 5.7%) at 32 weeks gestation and 2.2% (95% CI 2.1, 2.3%) at 38 weeks gestation, While the absolute probability of non-transfusion related severe maternal morbidity was lower at each gestational age week, the relationship with gestational age was the same (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1. Predicted probability of severe maternal morbidity by gestational age in an adjusted model. Gestational age is represented as a continuous variable. Confounders adjusted for include age, race, insurance status, marital status, parity, and preexisting hypertension or diabetes.

To further characterize preterm and term severe maternal morbidity, we evaluated indicator-specific severe maternal morbidity overall and across gestational age epochs. The most common severe maternal morbidity indicators overall were blood transfusion, sepsis, acute renal failure, peripartum hysterectomy, heart failure, and cardiac arrhythmia. Blood transfusion was the most common severe maternal morbidity indicator across all gestational age epochs and occurred in 34%, 28%, and 41% of deliveries less than 28 weeks, between 28 to 36 weeks, and term, respectively (). The average length of hospital stay for severe maternal morbidity was similar among gestational age categories. Admission to the intensive care unit, however, was twice as common in people with preterm deliveries less than 28 weeks (61%) compared with deliveries complicated by severe maternal morbidity at term (33%).

Table 2. Indicator-specific severe maternal morbidity stratified by gestational age epoch.

We observed unique patterns of non-transfusion-related indicator-specific severe maternal morbidity across gestational age epochs. Sepsis, acute renal failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, shock, and mechanical ventilation were the most common severe maternal morbidity diagnostic codes for patients delivering less than 28 weeks. Sepsis occurred in 14% of deliveries at less than 28 weeks while it was relatively uncommon in deliveries that occurred after 28 weeks gestation (2–3%). Rates of pulmonary edema were higher in all preterm deliveries less than 36 weeks of gestation compared to deliveries at term ().

Acute renal failure, hysterectomy, and heart failure were the leading diagnostic codes in patients with severe maternal morbidity delivering from 28 to 36 weeks gestation. Eclampsia also occurred most frequently in women within this gestational age epoch. Hysterectomy was highest among deliveries between 28 and 36 weeks. Heart failure, cardiac arrhythmia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation were the most common severe maternal morbidity diagnostic codes in deliveries occurring at greater than 37 weeks ().

Discussion

Our findings confirm that individuals who experience severe maternal morbidity disproportionately deliver preterm. After excluding blood transfusion, the most common indicators of severe maternal morbidity varied by gestational age. People who delivered extremely preterm were more likely to have severe maternal morbidity caused by sepsis, shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and acute renal failure compared with the term severe maternal morbidity. Cardiac complications—including heart failure and arrythmias were most common at term.

Our findings are largely consistent with the limited published literature. First, we observed that approximately 40% of severe maternal morbidity events occurred in women who delivered at less than 37 weeks of gestation. This is congruent with prior studies and highlights a vulnerable patient population who experience the dual burden of severe maternal disease and a preterm neonate [Citation9,Citation10]. Most notably, roughly one in ten birthing individuals who deliver less than 28 weeks experience severe maternal morbidity. Thus, women with the highest risk of neonatal complications secondary to prematurity also have the highest risk of severe maternal complications. Second, the risk for severe maternal morbidity has been strongly associated with underlying medical comorbidities as was in our study [Citation14–20].

Additionally, with regard to indicators of severe maternal morbidity, the existing literature is limited. Consistent with one other large study by Lyndon et al. we found that transfusion was the leading indicator of severe maternal morbidity across all gestational age categories. Importantly, transfusion of any blood product is a limited surrogate of true haemorrhage-associated morbidity and thus we were interested to look at causes beyond this indicator [Citation1,Citation19]. When we exclude transfusion, we observed a unique pattern of causes of severe maternal morbidity among individuals who delivered at different gestational age epochs. Our findings are generally consistent with Lyndon et al. who looked more broadly at all preterm deliveries, rather than differentiating between early and late preterm deliveries. Sepsis, shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and mechanical ventilation were more common in patients delivering less than 28 weeks gestation. Patients delivering at less than 28 weeks of gestation often have high rates of membrane rupture or stillbirth and these complications are associated with sepsis and shock indicators [Citation21]. Prior work also identifies that pregnancy-associated hypertensive disease is a major contributor to preterm severe maternal morbidity [Citation10]. In our study, rates of eclampsia, acute renal failure and pulmonary edema are common from 28–36 weeks which may be related to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Differentiating between early and late preterm deliveries highlights that these populations differ in both incidence of severe maternal morbidity and cause-specific indicators. We demonstrate highest rates of severe maternal morbidity among the extremely premature deliveries with pathology distinct from later preterm deliveries.

Lastly, our study reaffirms findings by Lyndon et al. that heart failure other combined cardiac indicators, and disseminated intravascular coagulation are the most common severe maternal morbidity indicators seen in term deliveries.

Our data highlight that while clinicians are primed to view deliveries at less than 28 weeks as a high risk for poor neonatal outcomes, we should also view these deliveries as a high risk for poor maternal outcomes. This has important implications for care delivery and suggests that clinicians should anticipate the early involvement of Maternal Fetal Medicine specialists and potential intensivists. Additionally, a large proportion of severe maternal morbidity is considered preventable, with many hospitals focusing on the management of hypertensive disease and hemorrhage [Citation22–24]. Our data highlight that much of the morbidity at early gestational ages are driven by sepsis and infectious etiologies. Thus, ensuring that hospitals have sepsis protocols for early recognition and treatment of sepsis is critical.

The dual burden of both severe maternal morbidity and preterm delivery has unique implications for both maternal and neonatal health and is an important area of ongoing investigation [Citation25]. Severe maternal morbidity is often described as a risk factor for preterm birth. This framing, however, hides a more complex relationship between these two entities. Severe maternal morbidity can lead to an indicated preterm birth or severe maternal morbidity can be the result of a complicated preterm delivery. For example, severe maternal morbidity such as renal failure may be secondary to a hypertensive disease of pregnancy and thus preterm delivery is indicated as part of the treatment for the maternal condition. Spontaneous preterm labor, however, can also be caused by or complicated by severe maternal morbidity, as in cases of abruption leading to disseminated intravascular coagulation or premature rupture of membranes leading to sepsis. Ideally, future work could disentangle this relationship using more granular data sources so we can understand how best to care for the mother-infant dyad. This is critical to inform intrapartum care approaches (i.e. decisions about mode of delivery), intervention development, and postpartum care pathways that reflect the nuanced reality of the relationship between severe maternal morbidity and preterm birth.

Our study has several strengths. We used a well-established definition of severe maternal morbidity to identify a large cohort of pregnancies complicated by maternal morbidity [Citation1]. The cohort was sufficiently large to evaluate differences in preterm and term patient populations. Furthermore, the database is regularly checked for validity against patient charts.

We also recognize several important limitations to our work. There is no uniform gold standard definition for severe maternal morbidity. Using ICD diagnostic and procedure codes, ICU admission, and postpartum length of stays as a screening method for severe maternal morbidity has a positive predictive value and negative predictive value of 48% and 99%, respectively when compared to the 2016 ACOG and SMFM Obstetric Care Consensus on severe maternal morbidity definitions [Citation2,Citation26]. Thus, we likely missed cases of morbidity that screened negative and this could bias our results. Importantly, blood transfusion was the most common ICD diagnostic code seen within our dataset and is an imperfect measure of hemorrhage-related morbidity. This dataset only includes the delivery hospitalizations and thus does not describe cases of severe maternal morbidity that occur in the postpartum time period. Our data is also limited to a single institution and thus may not be generalizable. Finally, we were unable to differentiate reliably between spontaneous and indicated preterm deliveries which is a critical area for future investigation.

Conclusions

The dual burden of both severe maternal morbidity and preterm delivery has unique implications for both maternal and neonatal health. People who delivered at less than 28 weeks gestation were at the highest risk for severe maternal morbidity and had distinct indicators associated with their morbidity compared to individuals with morbidity later in gestation. Thus, this group of patients may benefit from additional support and care pathways to optimize maternal outcomes.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (55.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Severe Maternal Morbidity in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed 2020April 1, Avaailable from: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/severematernalmorbidity.html. 2020.

- Obstetric Care Consensus No. 5: severe maternal morbidity: screening and review. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):e54-60.

- Geller SE, Rosenberg D, Cox S, et al. A scoring system identified near-miss maternal morbidity during pregnancy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(7):716–720.

- Main EK, Abreo A, McNulty J, et al. Measuring severe maternal morbidity: validation of potential measures. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(5):643.e1–643.e10.

- Creanga AA. Maternal mortality in the United States: a review of contemporary data and their limitations. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61(2):296–306.

- Geller SE, Rosenberg D, Cox SM, et al. The continuum of maternal morbidity and mortality: factors associated with severity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(3):939–944.

- Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1029–1036.

- Kuklina EV, Meikle SF, Jamieson DJ, et al. Severe obstetric morbidity in the United States: 1998-2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 1):293–299.

- Grobman WA, Bailit JL, Rice MM, et al. Frequency of and factors associated with severe maternal morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(4):804–810.

- Kilpatrick SJ, Abreo A, Gould J, et al. Confirmed severe maternal morbidity is associated with high rate of preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(2):233.e1-7–233.e7.

- Reddy UM, Rice MM, Grobman WA, et al. Serious maternal complications after early preterm delivery (24–33 weeks’ gestation). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):538.e1-9–538.e9.

- Kilpatrick SJ, Prentice P, Jones RL, et al. Reducing maternal deaths through state maternal mortality review. J Womens Health. 2012;21(9):905–909.

- Committee opinion no 700: methods for estimating the due date. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(5):e150–e154.

- Fingar KR, Hambrick MM, Heslin KC, et al. Trends and disparities in delivery hospitalizations involving severe maternal morbidity, 2006–2015. Healthcare Cost and utilization Project Statistical Brief. 2018;243. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30371995.

- Parekh N, Jarlenski M, Kelley D. Prenatal and postpartum care disparities in a large medicaid program. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(3):429–437.

- Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2011–2013. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):366–373.

- Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006–2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):5–12.

- Mujahid MS, Kan P, Leonard SA, et al. Birth hospital and racial and ethnic differences in severe maternal morbidity in the state of California. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(2):219.e1–219.e15.

- Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Kuklina EV, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity: a multistate analysis, 2008–2010. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(5):435.e1-435–e8.

- Wang E, Glazer KB, Howell EA, et al. Social determinants of Pregnancy-Related mortality and morbidity in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(4):896–915.

- Lewkowitz AK, Rosenbloom JI, López JD, et al. Association between stillbirth at 23 weeks of gestation or greater and severe maternal morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(5):964–973.

- Lawton B, MacDonald EJ, Brown SA, et al. Preventability of severe acute maternal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(6):557.e1-6–557.e6.

- Geller SE, Adams MG, Kominiarek MA, et al. Reliability of a preventability model in maternal death and morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(1):57.e1-6–57.e6.

- Ozimek JA, Eddins RM, Greene N, et al. Opportunities for improvement in care among women with severe maternal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):509.e1-509–e6.

- Lyndon A, Baer RJ, Gay CL, et al. A population-based study to identify the prevalence and correlates of the dual burden of severe maternal morbidity and preterm birth in California. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2021;34(8):1198–1206.

- Himes KP, Bodnar LM. Validation of criteria to identify severe maternal morbidity. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2020;34(4):408–415.