Abstract

Objective

Though misoprostol is commonly used for inpatient cervical ripening, its use in outpatient settings has been limited by safety concerns. This study was conducted to assess the association between early fetal heart tracing (FHT) and maternal tocodynamometry patterns and the incidence of adverse fetal and pregnancy outcomes after the administration of oral misoprostol for cervical ripening.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of 9908 low-risk patients at ≥37 weeks gestation who received oral misoprostol for cervical ripening prior to rupture of membranes between 01/01/2012 and 12/31/2017 at Kaiser Permanente Northern California hospitals as inpatients. We excluded patients who received a different agent for cervical ripening or had any need for additional inpatient monitoring, including hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, diabetes, or intrauterine growth restriction. Abnormal FHT, abnormal uterine activity, and adverse pregnancy or fetal-related events documented in the electronic health record in the four hours after administration of the first and second doses of misoprostol were assessed using descriptive statistics.

Results

We found that 0.9% of patients experienced tachysystole after the first dose of misoprostol (0.6% without decelerations; 0.3% with decelerations). The incidence of variable decelerations only and other FHT abnormalities (i.e. bradycardia, late or prolonged decelerations, or absent or minimal variability) in the first hour after misoprostol administration were 7.1% and 6.7% respectively, and diminished over time. The need for tocolytic use was 0.2% in the first hour and declined over time to 0.03% in the fourth hour after the first dose. Urgent cesarean delivery occurred in 0.1% of patients after receiving the first dose of misoprostol. Patients who did not experience variable, prolonged, or late decelerations in the first hour after the initial misoprostol dose were less likely to have such FHT abnormalities in the subsequent three hours compared to patients who had other FHT abnormalities (11.8% among patients with no FHT abnormalities vs. 43.7% among patients with other FHT abnormalities; p <.001). The overall trends in outcomes over time were similar after the second dose of misoprostol.

Conclusion

The risk of short-term adverse outcomes associated with misoprostol is low among relatively low-risk patients. FHT abnormalities occurred in up to 32% of patients in the first four hours of monitoring post-misoprostol. Patients with no FHT abnormalities in the first hour after receiving misoprostol had a low risk of developing adverse outcomes and FHT abnormalities on continued monitoring, while patients with any type of deceleration in the first hour were at higher risk of adverse outcomes and FHT abnormalities. Our data may inform the development of protocols for cervical ripening that allow reduced monitoring for a subset of low-risk patients, however, more research is needed to validate findings and develop clinical protocols.

Introduction

Induction of labor (IOL) is an increasingly common obstetric procedure that uses significant inpatient resources [Citation1]. In 2018, 27.1% of all births in the United States were induced, a dramatic increase from 9.5% in 1989 (the first year for which data are available) [Citation2,Citation3]. This increase reflects a rise in IOL both with and without medical indications [Citation3–5]. More inductions place a higher demand on inpatient resources and elevate the importance of strategies to maximize safety and optimize resource utilization [Citation6].

Cervical ripening, used to facilitate softening and thinning of the cervix, is the initial and often time-consuming of induction of labor [Citation7–10]. Approximately half of all patients undergoing IOL present with an unfavorable cervix [Citation11]. Oral misoprostol is a cervical ripening agent that is effective, safe, easy to use, and cost-effective [Citation12–15]. Previous studies have shown that fetal heart tracing (FHT) abnormalities can occur after misoprostol administration and increase with increasing doses of misoprostol [Citation16,Citation17]. However, previous studies have not examined the timing of these abnormalities in relation to the administration of oral misoprostol, or the effect of initial FHT on subsequent adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes such as the need for cesarean delivery, low Apgar scores, and admission of the newborn to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). This has limited the ability to create evidence-based strategies of intermittent fetal monitoring that may be preferable to patients and clinicians alike.

The ability to manage patients after misoprostol administration either in a hospital unit with step-down monitoring or in an outpatient setting could potentially reduce the length of hospitalization for low-risk patients undergoing IOL, increase the availability of resources for laboring and higher-risk patients on labor and delivery, and promote patient satisfaction [Citation18–20]. Our primary objective was to examine FHT abnormalities following the administration of the first dose, and for patients in which it was indicated, the second dose of oral misoprostol. Our secondary aim was to evaluate the incidence of later fetal and obstetric adverse events. Since high-risk patients typically require additional inpatient monitoring, this study was designed to evaluate outcomes among relatively low risk patients who may be candidates for less monitoring.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from electronic health records from 24 labor and delivery units in Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) hospitals. KPNC is an integrated healthcare delivery system currently serving approximately 4.5 million people with over 43,000 livebirth deliveries annually across the region which includes the San Francisco Bay Area, Peninsula, Central Valley, and greater Sacramento area of the State of California. This study was approved by the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute’s Institutional Review Board with a waiver of consent.

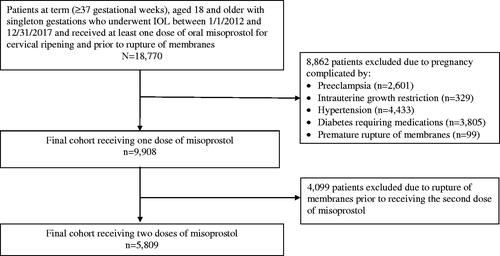

We included all term (≥37 gestational weeks) adult patients aged 18 years and older with singleton gestations who underwent IOL between 2012 and 2017 and received at least one dose of oral misoprostol for cervical ripening upon admission to the labor and delivery unit and prior to rupture of membranes (). Since the timing of mechanical ripening was not attainable from our dataset, patients who received mechanical ripening with a cervical balloon during their inpatient induction were excluded from the analysis. Patients were also excluded if they had received misoprostol or oxytocin prior to their inpatient admission for induction of labor (including outpatient misoprostol or prior admission for induction of labor with discharge home). To focus our study on the effects of misoprostol on pregnancy and FHT abnormalities, we excluded patients with underlying diseases that elevate and may therefore confound the risk of fetal distress; therefore, patients were also excluded if the pregnancy was complicated by hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (including preeclampsia, chronic or gestational hypertension, eclampsia, HELLP syndrome), intrauterine growth restriction, or diabetes requiring medications, or if the patient had a history of prior uterine incisions (i.e. myomectomy, cesarean). In addition, patients who had rupture of membranes prior to receiving their second dose were excluded from the analysis associated with the second dose.

Figure 1. Selection of final study sample from patients undergoing cervical ripening by oral misoprostol at all Kaiser Permanente Northern California Hospitals from January 1, 2012 through December 31, 2017.

The standard protocol within KPNC for patients undergoing IOL, developed based on prior evidence, is to administer 50 μg of misoprostol orally. Patients who continued to have an unripe cervix without evidence of FHT abnormalities or tachysystole after at least four hours of monitoring are given 100 μg of misoprostol [Citation14,Citation21,Citation22]. While patients could go on to receive additional doses, outcomes for this subset of patients were not included in this analysis. Continuous electronic FHT and tocometry monitoring is conducted on all patients undergoing inpatient IOL. The FHT monitoring records and labor and delivery nursing flowsheets are recorded in HealthConnect®, the EPIC-based electronic health record platform used in all KPNC hospitals.

FHT abnormalities are documented by the bedside nurse during labor using definitions provided by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development. Category II FHT findings, defined by ACOG as all FHT not categorized as Category I or III, are associated with a wide range of fetal outcomes and there is currently no standardized protocol for management or intervention. At KPNC, the algorithm by Clark et al. is used as a guide to manage Category II tracings [Citation23]. However, in our dataset, we could not use the Clark et al. categorization since variable decelerations were categorized only as “present” or “absent.” Therefore to acknowledge the wide range of management recommendations for category II, specifically that the presence of intermittent variable decelerations is not associated with acidemia, and the limitations of available information within our dataset, we classified FHT abnormalities as (1) none; (2) variable decelerations only; and (3) other significant FHT abnormalities (i.e. bradycardia, late or prolonged decelerations, or absent or minimal variability) with or without variable decelerations [Citation23–25]. Patients were included in both categories 2 and 3 if they met the criteria for both.

Our study focused on the timing of adverse events after misoprostol administration. Study outcomes assessed at specific time points from misoprostol administration included: (1) FHT abnormalities; (2) the presence of tachysystole, with or without decelerations; (3) the need for intrauterine resuscitation, including maternal position change and the administration of tocolytic agents; and (4) the development of adverse events including urgent cesarean delivery, Apgar scores below 7 at 5 min (hereafter termed “low Apgar score”), and admission of the newborn to the NICU. Since serum levels of misoprostol peak at about 30 min and rapidly decline by 120 min after oral administration, and a second dose of misoprostol was typically administered after four hours, and outcomes were measured in 60-min intervals for four hours after the administration of misoprostol [Citation26].

Patient characteristics assessed included the patient’s age, race, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), gestational age at hospital admission, cervical dilation and effacement at admission, and indication for induction. Race was categorized as non-Hispanic white, African American, Hispanic, Asian, and Other. The most recently charted BMI value within the 14 days prior to admission was utilized and was observed as both a continuous and categorical variable, with categories of <30, 30–40, and >40 kg/m2. Cervical effacement was categorized as 0–30%, 31–50%, 51–70%, or >70%. Induction indication categories included: elective (which was defined as either elective or due to history of rapid labor, intrauterine fetal demise, inadequate contractions, poor reproductive history, premature separation of the placenta, unstable lie), fetal indications (defined as intrauterine growth restriction, oligohydramnios, fetal anomalies, polyhydramnios), other maternal medical indications (defined as maternal cardiovascular, renal, or liver diseases, maternal coagulation deficiency, maternal isoimmunization, antepartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis), post-term pregnancy (defined as a gestational age of 41 weeks or more), two or more indications, or unknown.

To better understand the rare adverse events associated with misoprostol, the senior author and Maternal-Fetal Medicine physician (VM) performed a chart review of the 10 patients who underwent cesarean delivery within four hours of the first misoprostol dose. All electronic medical records from admission to delivery were reviewed including physician and nursing documentation, and FHT information was obtained from bedside nurse documentation.

Statistical analysis

Distributions of patient characteristics by FHT pattern in the first hour after the first dose of misoprostol were calculated and expressed as frequencies (%) or means (± standard deviation [SD]), as appropriate. Incidence of FHT abnormalities and outcomes of interest were assessed by time interval after the first dose of misoprostol. Fisher exact tests were used to compare outcomes that occurred in the 61–240 minutes after the initial dose of misoprostol across groups based on FHT status within 60 minutes after the initial misoprostol dose. To explore the association between FHT abnormalities and study outcomes, we stratified patients by FHT abnormalities in the first hour after the first dose of misoprostol. Patients with variable decelerations only and patients with other FHT abnormalities were compared to each other and to patients who had no FHT abnormalities. Patients who had an urgent cesarean section within the first hour following the first dose of misoprostol were not included in the analysis of the subsequent three hours. In order to control for the multiple testing, p-value adjustment was made using the Bonferroni method. Outcomes after the second dose of misoprostol were assessed in the subset of patients who received a second dose of misoprostol, and the same exclusion condition of urgent cesarean section was also applied. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) with the threshold of significance set at two-sided p < .05.

Results

A total of 9908 patients met the inclusion criteria. The baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in . The cohort had a mean age of 30.2 (± 5.5) years old, a mean BMI of 32 (± 5.8) kg/m2, and gestational age of 40.6 (± 1.2) weeks. Nearly half of the patients were non-Hispanic white (47.1%), followed by 24.1% Hispanic, 19.9% Asian, 7.0% African American, and 1.9% other race. The racial distribution in each FHT abnormality group in the first hour after the initial dose of misoprostol was similar to that of the entire cohort. However, among patients with other FHT abnormalities, the patients were more likely to be racially African American than Hispanic (12.7% vs. 20.7%, p < .001). Of the 9908 patients, 41.3% received only one dose of misoprostol, while 58.6% received additional doses. Among patients who had a documented reason for induction, the most common indication was post-term pregnancy (35.6%).

Table 1. Maternal and neonatal characteristics in patients who received inpatient misoprostol for induction of labor.

Outcomes following the first dose of misoprostol by time from the administration are presented in . Among the 9908 patients, the incidence of tachysystole without decelerations slightly increased over time but remained uncommon, occurring in 0.6% of patients within four hours after the initial misoprostol dose. Tachysystole with decelerations was less common, occurring in 0.3% of patients in the four hours after the first dose. Less than one in every five patients (18.1%) experienced variable decelerations only, and 18.6% experienced other FHT abnormalities within four hours after the first dose of misoprostol. The incidence of both categories of FHT abnormalities diminished after the first-hour post-misoprostol (variable decelerations only: decreased from 7.1% in the first hour to 3.3% in the fourth hour; other FHT abnormalities: decreased from 6.7% in hour one to 4.5% in hour four) (). Ten patients (0.1%) required an urgent cesarean delivery after misoprostol administration, of which three infants required NICU admission and one had a low Apgar score. The need for intrauterine resuscitation of oxygen administration, position change, or the administration of tocolytic agents was also low and declined after the first hour (e.g. tocolytic use declined from 0.2% in the first hour to 0.03% in the fourth hour). The prevalence and timing of maternal and neonatal outcomes in patients following a second dose of misoprostol and patients undergoing IOL are shown in and exhibited similar findings.

Table 2. Frequency and timing of maternal and neonatal events following first dose of misoprostol (N = 9908).

FHT patterns and adverse outcomes after the first hour of monitoring are shown in . FHT findings in the initial hour post-administration were associated with subsequent FHT findings and the occurrence of adverse outcomes over the following three hours. Patients who had no FHT abnormalities in the first hour after administration of misoprostol were unlikely to have any FHT abnormalities in the subsequent three hours. However, four (0.1%) patients who had no FHT abnormalities in the first hour of monitoring after the first dose of misoprostol later had an urgent cesarean delivery. Compared to patients with no FHT abnormalities and the other FHT abnormalities in the first-hour post-misoprostol, patients who had variable decelerations only were most likely to have variable decelerations only in the subsequent three hours of monitoring (34.2% vs. 9.6%, p < .001; 34.2% vs. 13.8%, p < .001, respectively). Patients who had other FHT abnormalities in the first hour were most likely to have other FHT abnormalities at some point in the next three hours.

Table 3. FHT abnormalities and adverse outcomes in the 61–240 min following the first dose of misoprostol (N = 9907Table Footnotea).

FHT patterns in the group of patients who had no FHT abnormalities in the first hour of monitoring post-administration were reviewed. Patients who had no FHT abnormalities in this first hour were significantly less likely to require intrauterine resuscitation later compared to patients who had any FHT abnormalities upon initial monitoring (4.3% vs. 7.6% for no FHT abnormalities vs. variable decelerations only, p = .001; 4.3% vs. 9.7% for none vs. other FHT abnormalities, p < .001). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the need for intrauterine resuscitation between patients who had variable decelerations only and those who had other FHT abnormalities in the first hour of monitoring (7.6% vs. 9.7%, p = .53). Patients who had other FHT abnormalities in the first hour of monitoring were more likely to have an urgent cesarean compared to patients who had no FHT abnormalities in the first-hour post-misoprostol (0.8% vs. 0.1%, p = .001). While patients who had any type of FHT abnormality in the first hour were less likely to have no FHT abnormalities in the subsequent three hours, there was no statistically significant difference between patients who had variable decelerations only and those who had other FHT abnormalities (41.5 vs. 42.6%, p > .999). The overall trends in outcomes over time remained the same after the second dose of misoprostol ().

To better understand the rare adverse events associated with misoprostol, a chart review was performed for the 10 patients who underwent cesarean delivery within four hours of the first misoprostol dose (). In seven of the cases, decelerations were observed that resolved, and a cesarean was then performed that was not classified as urgent. No tachysystole was observed in these cases. In three of the cases, tachysystole with decelerations were observed. In two of these cases, placental abruption was suspected by delivering clinicians and a cesarean was classified as urgent, meaning it took place within four hours after misoprostol administration. One of these abruption cases resulted in a low Apgar score (of 1 at one minute, 4 at 5 min) and NICU admission. Blood gasses were sent but not resulted in this case.

Discussion

Principal findings

Our study describes the incidence and timing of FHT abnormalities and the association of initial FHT pattern with subsequent adverse events after oral misoprostol. We selected a relatively low-risk IOL patient population. We found that adverse outcomes in the four hours after administration of 50 mcg of oral misoprostol may be as high as 32%, which is higher than what has previously been reported (between 0 and 13%), though prior data is mostly based on vaginal administration [Citation27]. We also found that having other FHT abnormalities such as bradycardia, late or prolonged decelerations, or absent or minimal variability were associated with an increased likelihood of requiring intrauterine resuscitation in the subsequent hours.

Approximately one in five patients experienced variable and other FHT abnormalities and most occurred in the first hour of monitoring. However, even among patients who underwent cesarean within four hours of misoprostol administration, neonatal adverse outcomes were rare, which supports other literature showing a high false-positive rate for FHT abnormalities in predicting neonatal outcomes [Citation28,Citation29].

Tachysystole was very uncommon (<1%), and abnormal FHT monitoring patterns in the first hour after administration were associated with abnormal monitoring patterns and adverse events in the subsequent three hours of monitoring. Cesarean delivery in the first four hours was also very uncommon (0.1%), however in this small group, there were three cases of tachysystole and two cases of placental abruption.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our study include a large community-based sample and electronic capture of FHTs which enabled us to characterize FHT patterns and outcomes associated with those patterns. The major limitation of this study is its retrospective design. Factors that were not recorded at the point of care were not available for analysis. For example, we were unable to examine how indication for IOL is associated with initial FHT findings and the development of adverse events because the reason for induction was not documented in structured data fields in the EHR in 50% of our sample. Additionally, because we do not know the induction indication for 50% of our sample, it is possible that our sample is not representative of low-risk but rather a more general laboring patient population. Because we were unable to account for other potential risk factors, we may be overestimating the true risk of adverse outcomes after misoprostol. Because we were unable to assess which inductions were elective, we could not estimate the risk in a known low-risk population. This study did not include information about parity however labor course does differ by parity and FHT abnormalities could also differ. We were also unable to analyze information on the duration and frequency of FHT changes, therefore we could not use standard FHT categorizations such as Clark et al. or Parer et al. [Citation23,Citation30]. Since our study focused on oral misoprostol, our findings cannot be generalized to other routes of misoprostol administration. FHT data were extracted from nursing documentation of events rather than an examination of the FHT data itself, which limited the classification of abnormalities; for example, variable decelerations were classified as either present or absent and therefore could not be classified by the criteria laid out by Clark et al. [Citation23]. Lastly, we recognize that while the dosing of misoprostol was within a well-studied range, it was relatively higher than what is used at some other institutions and thus may limit generalizability [Citation31].

Results

While previous studies have shown the association between misoprostol and adverse maternal and fetal events, to our knowledge this is the first study to examine the timing of adverse events that could help to inform the development of a monitoring protocol after misoprostol administration. This large, multi-center retrospective study provides data on the incidence of adverse outcomes after oral misoprostol and monitoring patterns associated with adverse outcomes.

Clinical Implications

These results have two important implications for the clinical use of misoprostol. It is possible that patients at the lowest risk for adverse events after the administration of oral misoprostol may be identified after one hour of fetal monitoring. Patients with no FHT abnormalities in the first hour after the first dose of misoprostol may be candidates for reduced monitoring, either in the hospital or potentially in the outpatient setting. Our data also suggests that patients with any type of deceleration in the first hour, whether a variable, late, or prolonged, are at higher risk for additional FHT abnormalities and adverse outcomes.

Research Implications

Further research is needed to validate findings and develop protocols for clinical use. Larger prospective trials about reduced monitoring during cervical ripening with oral misoprostol are needed. Future research can expand upon these findings by incorporating other risk factors to create a predictive model. We did not include the outcomes beyond the second dose of misoprostol because we focused on patients in the early phase of IOL, namely cervical ripening, who may be candidates for reduced monitoring; however, future studies may explore the outcomes among patients receiving subsequent doses of misoprostol and the implications of reduced monitoring in those respective stages of labor. Since four patients who experienced no FHT abnormalities in the first hour of monitoring went on to require urgent cesarean delivery, FHT alone is limited as a predictive variable. Thus, there is a need to consider other risk factors (e.g. age, race, ethnicity, indication for induction, and other pregnancy characteristics) in future multivariable regression analyses.

Conclusion

In conclusion, adverse events after cervical ripening with oral misoprostol are rare and FHT abnormalities in the four after post-misoprostol may be as high as 32%. It may be possible to identify a group of patients at low risk for subsequent adverse outcomes after the first hour of fetal monitoring. Our data may inform the development of protocols for labor induction with misoprostol administration that allow reduced fetal monitoring for selected groups of patients.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Morrish D, Hoskins IA. Induction of labor: review of pros, cons, and controversies. In: Childbirth. IntechOpen; 2020. DOI:10.5772/intechopen.89237

- Zhang J, Yancey MK, Henderson CE. U.S. national trends in labor induction, 1989–1998. J Reprod Med. 2002;47(2):120–124.

- Martin J, Hamilton B, Osterman M, et al. Births: final data for 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(13):1–47.

- Moore LE, Rayburn WF. Elective induction of labor. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49(3):698–704.

- Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Mean age of mothers is on the rise: United States, 2000–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2016;232:1–8.

- Grobman WA. Is it time for outpatient cervical ripening with prostaglandins? BJOG. 2015;122(1):105–105.

- Teixeira C, Lunet N, Rodrigues T, et al. The bishop score as a determinant of labour induction success: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286(3):739–753.

- Kouam L, Kamdom-Moyo J, Shasha W, et al. Induced labor: conditions for success and causes of failure. A prospective study of 162 cases. Rev Fr Gynecol Obstet. 1993;88(4):243–248.

- Keirse MJ. Prostaglandins in preinduction cervical ripening. Meta-analysis of worldwide clinical experience. J Reprod Med. 1993;38(1 Suppl):89–100.

- Pierce S, Bakker R, Myers DA, et al. Clinical insights for cervical ripening and labor induction using prostaglandins. AJP Rep. 2018;8(4):e307–e314.

- Rayburn WF. Preinduction cervical ripening: basis and methods of current practice. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57(10):683–692.

- Allen R, O’Brien BM. Uses of misoprostol in obstetrics and gynecology. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(3):159–168.

- Muzonzini G, Hofmeyr GJ. Buccal or sublingual misoprostol for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2004(4):CD004221.

- Alfirevic Z, Aflaifel N, Weeks A. Oral misoprostol for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;13(6):CD001338.

- Kipikasa JH, Adair CD, Williamson J, et al. Use of misoprostol on an outpatient basis for postdate pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88(2):108–111.

- Ramsey PS, Meyer L, Walkes BA, et al. Cardiotocographic abnormalities associated with dinoprostone and misoprostol cervical ripening. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(1):85–90.

- Stephenson ML, Powers BL, Wing DA. Fetal heart rate and cardiotocographic abnormalities with varying dose misoprostol vaginal inserts. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(2):127–131.

- Adelson PL, Wedlock GR, Wilkinson CS, et al. A cost analysis of inpatient compared with outpatient prostaglandin E2 cervical priming for induction of labour: results from the OPRA trial. Aust Health Rev. 2013;37(4):467–473.

- Stitely ML, Browning J, Fowler M, et al. Outpatient cervical ripening with intravaginal misoprostol. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 Pt 1):684–688.

- Amorosa JMH, Stone JL. Outpatient cervical ripening. Semin Perinatol. 2015;39(6):488–494.

- Shetty A, Livingstone I, Acharya S, et al. A randomised comparison of oral misoprostol and vaginal prostaglandin E2 tablets in labour induction at term. BJOG. 2004;111(5):436–440.

- Cheung PC, Yeo ELK, Wong KS, et al. Oral misoprostol for induction of labor in prelabor rupture of membranes (PROM) at term: a randomized control trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(9):1128–1133.

- Clark SL, Nageotte MP, Garite TJ, et al. Intrapartum management of category II fetal heart rate tracings: towards standardization of care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(2):89–97.

- Robinson B, Nelson L. A review of the proceedings from the 2008 NICHD workshop on standardized nomenclature for cardiotocography. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1(4):186–192.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 106: intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring: nomenclature, interpretation, and general management principles. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(1):192–202.

- Tang OS, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Ho PC. Misoprostol: pharmacokinetic profiles, effects on the uterus and side-effects. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2007;99: S160–S167.

- Leach KK, Onysko M. How common is uterine tachysystole with fetal heart rate abnormalities when inducing labor with misoprostol? Evid-Based Pract. 2013;16(9):14.

- Nelson KB, Dambrosia JM, Ting TY, et al. Uncertain value of electronic fetal monitoring in predicting cerebral palsy. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(10):613–618.

- Alfirevic Z, Gyte GM, Cuthbert A, et al. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2(2):CD006066.

- Parer JT, Ikeda T. A framework for standardized management of intrapartum fetal heart rate patterns. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(1):26.e1-6–26.e6.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins – Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 107: induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 Pt 1):386–397.

Appendix

Table A1. Frequency and timing of maternal and neonatal events following second dose of misoprostol (N = 5809).

Table A2. FHT abnormalities and adverse outcomes in the 61–240 min following the second dose of misoprostol, (N = 5806Table Footnotea).

Table A3. Chart review results of patients requiring urgent cesarean after misoprostol administration.