Abstract

Objective

Epidural analgesia has been widely used as a form of pain relief during labor and its safety has been gradually recognized. However, few studies of the effect of epidural analgesia on the pelvic floor are known. Thus, we aim to analyze the effect of epidural analgesia on labor progress and women’s pelvic floor muscle from the perspective of electromyography systematically. In addition, obstetric risk factors for dysfunction of pelvic floor muscle after vaginal delivery were also evaluated.

Methods

Childbirth data of 124 primiparas who gave first birth vaginally in our hospital and their pelvic floor function assessment results at postpartum 7 weeks were retrospectively collected. Pelvic floor muscle electromyogram screenings were performed by a biofeedback electro-stimulant therapy instrument.

Results

There was no significant difference in the percentage of episiotomy, forceps, artificial rupturing membrane, and the application of oxytocin, except perineal laceration. Woman who implemented epidural analgesia experienced a longer stage of labor. Statistically, there was no significant difference in the total score and pelvic floor muscle strength. The risk factors for the value of the pre-rest phase include the age of pregnant women, the fetal weight, and the length of the second stage while the value of the post-rest phase was only associated with the fetal weight and the length of the second stage. In addition, the value of type I muscles was associated with the gravida and fetal weight while the value of type II muscles was only associated with forceps. The sustained contraction was correlated with the gravida and the total scores had a significant correlation with forceps.

Conclusion

Epidural analgesia during labor is approved to be a safe and effective procedure to relieve pain with very low side effects on the mode of labor and pelvic floor muscle. The assessment of pelvic floor muscle before pregnancy is beneficial in guiding the better protection of pelvic floor muscle function. According to the evaluation results, the doctors can control the associated risk factors as much as possible to reduce the injury of pregnancy and parturition to the pelvic floor.

Introduction

Pain during childbirth is reported to be the most painful experience in a woman’s lifetime. Painful labor has several adverse effects on the health of both mother and baby [Citation1]. As is known to all, epidural analgesia is widely used as a form of pain relief during labor and it’s also the gold standard analgesic technique for uterine contraction pain relief [Citation2]. However, there are concerns about how epidural analgesia affects the labor progress. Particularly, the impacts of epidural analgesia on women’s pelvic floor muscle (PFM) still need to be further investigated.

Due to the variation in medical dosage, contraindications, and patient preference, the association between epidural analgesia and vaginal delivery is uncertain [Citation3]. Several retrospective studies have demonstrated that women with epidural analgesia had significantly longer second stage of labor, higher cesarean section, and instrumental vaginal delivery [Citation1, Citation4–6]. However, no significant differences have been highlighted in other studies [Citation7–9]. In addition, another controversy was the initiation time of epidural placement. Some randomized trials revealed that early initiation of epidural analgesia was not associated with an increased rate of cesarean section. On the contrary, it resulted in a shorter duration of labor [Citation10,Citation11]. However, a systematic review found that early or late initiation of epidural analgesia for labor had similar effects on all measured outcomes [Citation12]. Further potentially adverse effects of epidural analgesia on women’s pelvic functions have not been evaluated.

The levator ani muscle is the most important supporting structure for the pelvic floor and it is the most important part of pelvic floor muscles. According to the tissue typing, the levator ani muscle belongs to the skeletal muscle that has sustained basal tension and is able to contract spontaneously. The muscle fibers of the levator ani muscle are divided into two types: type I fibers (slow muscle fibers) and type II fibers (fast muscle fibers). The former is related to the support and maintenance of posture function in the resting state and the latter is primarily involved in maintaining support functions in the dynamic state, with the proportions of the two types being 70% and 30%, respectively [Citation13]. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of epidural analgesia on labor progress and women’s PFM from the perspective of electromyography systematically. In addition, obstetric risk factors for dysfunction of PFM after vaginal delivery were also evaluated. We speculate that epidural analgesia in labor will prolong the whole stages of labor, not only the first and second stages of labor but also the third stage of labor. Due to the prolonged labor process, vaginal delivery may aggravate the damage to the pelvic floor muscles.

Materials and methods

This was a single-center retrospective observational study including 124 primiparas who attended Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital for term labor (at least 37 completed weeks of gestation) between July 2020 and October 2020. All women who gave first birth vaginally during this period and underwent pelvic floor function assessment at postpartum 7 weeks were included. The inclusion criteria included a head presentation, singleton pregnancy, and natural labor. All participants had no internal or surgical complications and there was no special medication history. The exclusion criteria were as follows: chronic cough, pelvic organ prolapse, multiple pregnancies, history of urinary incontinence, and breech delivery.

Epidural analgesia was administrated by anesthetists according to the wishes of women with cervical dilatation of more than 1.5 cm. The patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) was used with a pump, and patients can control the dosing of analgesics by pressing a button. The analgesia was administered continuously with a standard, low-dose, local anesthetic solution (ropivacaine 0.1%, 2–3 ml/hour) by the pump. If the woman still feels pain, she can press the button to increase the dose (5–8ml/hour, lock-out 30 min). The epidural insertion was performed at the same standard process and drug formulation at the L3–4 intervertebral space. Every woman with PCEA will receive assessments of pain (numeric rating scale, NRS) and motor block (Bromage score) during delivery. At postpartum 6–8 weeks, pelvic floor muscle electromyogram screenings were performed on all the enrolled women by a biofeedback electro stimulant therapy instrument (Madlander, Nanjing, China). The strength of the slow muscle (type I) fibers and the fast muscle (type II) fibers were evaluated, with the former recorded by a contraction of 10s while the later recorded by the mean value of five fast contractions. In addition, the value of pre-rest and post-rest phase (static pelvic floor muscles’ tension before/after the muscle contractions) was also detected. A total score was generated based on the pelvic muscles’ contraction and relaxation, and the perfect score is 100.

All the detailed and clinical maternal information including delivery mode, and demographic data such as age, gestational characteristics, and previous medical and obstetrical history were documented and analyzed. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital (NO.2020QT371). Informed consent were obtained from all the participants.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0. Continuous variables were compared with Student’s t-test while proportions of categorical variables were analyzed by χ2 test. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to assess the high-risk factors for women’s pelvic floor muscles. A p value <.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Clinical characteristics

A total of 124 primiparas were enrolled in this research, with 67 participants with PCEA painless labor and 57 without any analgesia. There was no significant difference between these two groups in the general clinical information, such as age, gestational week, gravida, weight increase, and body mass index (BMI) increase during pregnancy and fetal weight (p > .05, ).

Table 1. The clinical general information of the primiparas with and without analgesia.

Obstetrical characteristics

Of 124 patients recruited, the number of patients undergoing episiotomy in the epidural analgesia group and the non-analgesia group was 67 and 57, respectively. There was no significant difference in the percentage of patients undergoing episiotomy. However, in terms of the perineal laceration, the percentage in the epidural analgesia group was significantly lower than that in the control group (p = .001, ). There was no significant difference in other obstetrical characteristics, such as the percentage of forceps, artificial rupturing membrane, and the use of oxytocin between the two groups (p > .05, ).

Table 2. The effect of epidural analgesia on the route of delivery.

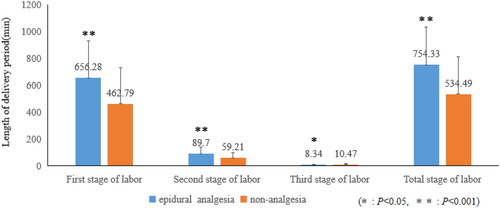

Length of the delivery period

The average total length of labor was 754.33 ± 278.99(mean ± SD) minutes in patients of the epidural analgesia group versus 534.49 ± 276.6 min in patients of the non-analgesia group (p < .001, Figure1). In addition, the length of the first stage of labor, the second stage of labor and the third stage of labor in patients of epidural analgesia group were significantly longer than those in the non-analgesia group ().

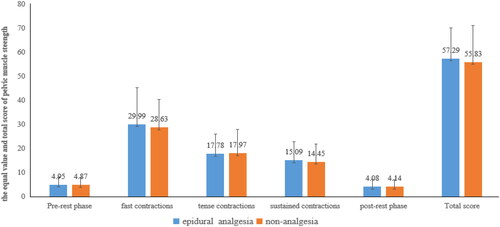

Pelvic floor muscle strength test

Both non-analgesia labor and painless labor damaged the pelvic floor function, and there was no significant difference between the two groups in the PFM strength, neither the type I fibers nor the type II fibers (). The total score in both two groups had no significant difference (p > .05). Epidural analgesia would prolong the labor period, but it didn’t exacerbate the damage of vaginal delivery to pelvic floor functions.

Figure 1. The effect of epidural analgesics on the length of delivery period. Note: The length of the first stage of labor, the second stage of labor, the third stage of labor and total stage of labor in patients of epidural analgesia group were significantly longer than those in the non-analgesia group.

Risk factors for pelvic floor muscle strength

In total, gestational week, epidural analgesia, episiotomy, length of the first stage, and length of the total stage were not significantly associated with PFM. However, as shown in , the age of pregnant women, the fetal weight, and the length of the second stage were significantly related to the value of the pre-rest phase while the value of the post-rest phase was only correlated with the fetal weight and the length of the second stage. In addition, the value of type I muscles was significantly associated with the gravida and fetal weight, while the value of type II muscles was only significantly correlated with forceps at univariate analysis. The sustained contractions and total scores of PFMs were associated with the gravida and forceps, respectively.

Table 3. Association between obstetric risk factors and PFM.

Discussion

The levator ani muscle is the most important supporting structure for the pelvic floor. It has been reported that the change in the proportion of the two fibers was the main manifestation of damage to the pelvic floor muscle’s support structure [Citation14]. The increase in the number of type I fibers and the decrease of type II fibers are not conducive to the rapid contraction of muscle fibers when abdominal pressure suddenly increases [Citation15]. Epidural analgesia is widely used as a form of pain relief in labor. However, studies of the effect of epidural analgesia on the PFM are few. In our research, we find that women with epidural analgesia experience longer stages of labor, not only the first and second stages of labor but also the third stage of labor. Epidural analgesia exerted very minor side effects on the mode of labor. Women with epidural analgesia have the same risk of episiotomy as the control group while the risk of perineal laceration is lower. Though epidural analgesia prolongs the labor period, it doesn’t exacerbate the damage of vaginal delivery to pelvic floor functions. Epidural analgesia, episiotomy, length of the first stage, and length of the total stage were not significantly associated with PFM.

Surface electromyography(sEMG) is a technique that records and analyzes spontaneous or artificially induced electrical activity of the nerve-muscle unit or nerve conductivity. Studies have confirmed that EMG can be used to measure PFM in the same as digital palpation [Citation16–18]. Ruan et al. found higher scores in the pre-and post-rest phases at postpartum 6–8 weeks in primiparas with PCEA than in those without analgesia, but no significant difference between the two groups in the type I or type II fibers [Citation19]. They suggested that epidural anesthesia could protect PFM. However, the number of participants included in their study was too few. Only 27 patients with painless labor and 36 without any analgesia were evaluated. In our present study, 124 primiparas were enrolled and our findings showed no significant difference in the PFM strength between the epidural anesthesia group and the non-analgesia group. The total scores in the two groups were not significantly different. Our finding is consistent with previous studies which showed that epidural analgesia didn’t affect PFMs in the early postpartum period [Citation20–22].

Epidural analgesia may affect the course, duration, and outcome of labor. Women with epidural analgesia are reported to experience more oxytocin administration, higher cesarean section, and instrumental vaginal delivery rates [Citation1,Citation23]. Moreover, the duration of labor in women with epidural analgesia could be prolonged. Besides this, other studies found that initiation of epidural analgesia in early labor was associated with a shorter duration of the first stage of labor and didn’t result in increased cesarean deliveries and instrumental vaginal deliveries [Citation10,Citation11]. Our study showed women with PCEA had statistically significantly longer first, second and total stages of labor. These data agreed with the result from Anim-Somuah et al. [Citation23], who assessed the effectiveness and safety of epidural analgesia in labor by meta-analysis. In conclusion, epidural analgesia in labor is a safe procedure to remove pain, with a very low side effect on the mode of labor.

In the pre/post-rest phase, the PFMs are relaxed. Increased myoelectricity value of the pre/post-rest phase can result in PFM ischemia. The prolonged pushing by the women during delivery is responsible for the muscle’s high intention, which is consistent with our findings. The age of women is a main factor for the high myoelectricity value of the pre-rest phase. It can be explained by the gradual loss of collagen with age, which leads to a decline in muscle compliance. Other research have displayed that high maternal age increased the risk of pelvic organ prolapse [Citation24,Citation25]. According to the results of a recent meta-analysis that identified risk factors for pelvic floor disorders, instrumental vaginal delivery was associated with urinary incontinence [Citation26]. Our research finds that instrumental vaginal delivery mainly damaged women’s type II muscles, which are associated with urination, defecation, and the pleasure of sex. Recently, a retrospective observational study displayed that birthweight was an independent risk factor for postpartum voiding dysfunction [Citation27]. It can be explained by our results that the fetal weight mainly affects the value of type I muscles and the pre/post-rest phase. In addition, previous animal models have demonstrated that elastin fibers played an important role in pelvic floor mechanics [Citation28]. The elastin fibers and smooth muscle cell contents of the rectum and bladder were decreased in both parous and pregnant sheep and the strength of vaginal tissues decreased during pregnancy [Citation28,Citation29]. These results agreed with our findings. Gravida is a main influence factor for type I muscles and total scores of PFMs.

Up to now, this is the first paper to use electromyography to evaluate the related obstetric risk factors affecting the pelvic floor muscles. Our research confirmed that epidural analgesia in labor was a safe procedure with very minor side effects on the mode of labor and PFM. This research can contribute to the understanding of pelvic floor muscles’ structure and its influencing factors. Based on the present study, the assessment of PFM is beneficial in guiding the better protection of PFM function during pregnancy. We suggest that the assessment of pelvic floor muscles should be performed before pregnancy and base on which the doctors can master exactly the basic condition of her PFM. Then, during the pregnancy and delivery periods, the obstetricians can control the associated risk factors as much as possible to reduce the injury of pregnancy and parturition to the pelvic floor.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital (NO. 2020QT371).

Acknowledgments

None.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cambic CR, Wong CA. Labour analgesia and obstetric outcomes. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105(Suppl 1):i50–i60.

- Gizzo S, Di Gangi S, Saccardi C, et al. Epidural analgesia during labor: impact on delivery outcome, neonatal well-being, and early breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(4):262–268.

- Serati M, Salvatore S, Khullar V, et al. Prospective study to assess risk factors for pelvic floor dysfunction after delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(3):313–318.

- Morton SC, Williams MS, Keeler EB, et al. Effect of epidural analgesia for labor on the cesarean delivery rate. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(6):1045–1052.

- Magann EF, Doherty DA, Briery CM, et al. Obstetric characteristics for a prolonged third stage of labor and risk for postpartum hemorrhage. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2008;65(3):201–205.

- Zaki MN, Hibbard JU, Kominiarek MA. Contemporary labor patterns and maternal age. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1018–1024.

- Orbach-Zinger S, Aviram A, Ioscovich A, et al. Anesthetic considerations in pregnant women at advanced maternal age. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(1):59–62.

- Gerli S, Favilli A, Acanfora MM, et al. Effect of epidural analgesia on labor and delivery: a retrospective study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(3):458–460.

- Shmueli A, Salman L, Orbach-Zinger S, et al. The impact of epidural analgesia on the duration of the second stage of labor. Birth. 2018;45(4):377–384.

- Wong CA, Scavone BM, Peaceman AM, et al. The risk of cesarean delivery with neuraxial analgesia given early versus late in labor. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(7):655–665.

- Ohel G, Gonen R, Vaida S, et al. Early versus late initiation of epidural analgesia in labor: does it increase the risk of cesarean section? A randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(3):600–605.

- Sng BL, Leong WL, Zeng Y, et al. Early versus late initiation of epidural analgesia for labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;10:CD007238.

- Gosling JA, Dixon JS, Critchley HO, et al. A comparative study of the human external sphincter and periurethral levator ani muscles. Br J Urol. 1981;53(1):35–41.

- DeLancey JO, Morgan DM, Fenner DE, et al. Comparison of levator ani muscle defects and function in women with and without pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):295–302.

- Kearney R, Sawhney R, Delancey JO. Levator ani muscle anatomy evaluated by origin-insertion pairs. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(1):168–173.

- Botelho S, Pereira LC, Marques J, et al. Is there correlation between electromyography and digital palpation as means of measuring pelvic floor muscle contractility in nulliparous, pregnant, and postpartum women? Neurourol Urodyn. 2013;32(5):420–423.

- Krhut J, Zachoval R, Rosier PFWM, et al. ICS educational module: electromyography in the assessment and therapy of lower urinary tract dysfunction in adults. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;9999:1–6.

- Oleksy L, Wojciechowska M, Mika A, et al. Normative values for glazer protocol in the evaluation of pelvic floor muscle bioelectrical activity. Medicine . 2020;99(5):5 (e19060.

- Ruan LJ, Xu XW, Wu HE, et al. Painless labor with patient-controlled epidural analgesia protects against short-term pelvic floor dysfunction: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(5):3326–3331.

- Tetzschner T, Sorensen M, Jonsson L, et al. Delivery and pudendal nerve function. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76(4):324–331.

- Viktrup L, Lose G. Epidural anesthesia during labor and stress incontinence after delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82(6):984–986.

- Sartore A, Pregazzi R, Bortoli P, et al. Effects of epidural analgesia during labor on pelvic floor function after vaginal delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(2):143–146.

- Anim-Somuah M, Smyth RMD, Cyna AM, et al. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD000331.

- Urbankova I, Grohregin K, Hanacek J, et al. The effect of the first vaginal birth on pelvic floor anatomy and dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30(10):1689–1696.

- Omih EE, Lindow S. Impact of maternal age on delivery outcomes following spontaneous labour at term. J Perinat Med. 2016;44(7):773–777.

- Hage-Fransen MAH, Wiezer M, Otto A, et al. Pregnancy and obstetric related risk factors for urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse later in life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(3):373–382.

- Perú Biurrun G, Gonzalez-Díaz E, Fernández Fernández C, et al. Post partum urinary retention and related risk factors. Urology. 2020;143:97–102.

- Rynkevic R, Martins P, Andre A, et al. The effect of consecutive pregnancies on the ovine pelvic soft tissues: link between biomechanical and histological components. Ann Anat. 2019;222:166–172.

- Alperin M, Feola A, Duerr R, et al. Pregnancy- and delivery-induced biomechanical changes in rat vagina persist postpartum. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(9):1169–1174.