Abstract

Objective

To evaluate whether eliminating routine gastric residual volume (GRV) assessments would lead to quicker attainment of full feeding volumes in preterm infants.

Study design

This is a prospective randomized controlled trial of infants ≤32 weeks gestation and birthweight ≤1250 g admitted to a tertiary care NICU. Infants were randomized to assess or not assess GRV before enteral tube feedings. The primary outcome was time to attain full enteral feeding volume defined as 120 ml/kg/day. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the days to reach full enteral feeds between the two groups.

Results

80 infants were randomized, 39 to the GRV assessing and 41 to the No-GRV assessing group. A predetermined interim analysis at 50% enrollment showed no difference in primary outcome and the study was stopped as recommended by the Data Safety Monitoring Committee. There was no significant difference in median days to reach full enteral feeds between the two groups [GRV assessment: 12d (5) vs. No-GRV assessment:13d (9)]. There was no mortality in either group, one infant in each group developed necrotizing enterocolitis stage 2 or greater.

Conclusion

Eliminating the practice of gastric residual volume assessment before feeding did not result in shorter time to attain full feeding.

Introduction

Gastric residual volume (GRV) assessment is the practice of measuring the gastric contents consisting of gastric secretions and milk remaining in the stomach prior to introducing a new feed [Citation1]. The volume and characteristics of GRV combined with factors such as abdominal examinations are often considered by clinicians when considering whether to continue with the scheduled enteral feeds. Large volume GRV is believed to be a manifestation of delayed gastric emptying due to the delayed gastrointestinal maturation of a preterm infant [Citation2]. In neonatal intensive care units where residuals are routinely assessed, clinicians may choose to discard the residual, re-feed the residual, partially re-feed the residual or hold a feed. There is no standard practice amongst clinicians between institutions and often within the same institution. Hence, this practice may delay the advancement of enteral feedings. Advancement of early enteral nutrition is delayed or discontinued for >24 h in nearly 75% of all extremely preterm infants [Citation3–5]. This is despite clinical evidence showing that early establishment of enteral nutrition is associated with reductions in the severity of critical illness, and long-lasting benefits on linear growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes [Citation6]. There were several retrospective and prospective studies that evaluated the role of GRV assessments in preterm infants. Elia et al. showed a decreased time to full enteral feeding and at regaining birth weight with selective GRV monitoring compared to routine monitoring [Citation7]. Singh et al. did not find any difference in the time to reach full feeds by avoiding GRV assessment [Citation8]. Parker et al. showed elimination of GRV assessment resulted in increased delivery of enteral nutrition and better weight gain [Citation9]. The practice of GRV assessment remains a common practice in preterm infants despite recent studies [Citation10]. Due to the conflicting results of the studies cited above, we felt that there is a need to perform additional randomized trial for this important issue. The primary objective of the current study was to compare the days to attain full enteral feeds in preterm infants assigned to routine assessing versus not assessing GRV. Our secondary objective was to determine if there is a difference in adverse events including necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) when not assessing GRV.

Methods

Study design and setting

This prospective randomized controlled trial was conducted at the Level IV Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at AdventHealth for Children in Orlando, Florida (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04062851). The study was conducted between May 2019 and October 2021. The Institutional Review Board at AdventHealth, Orlando approved the study.

Population

Preterm infants born ≤32 weeks gestation and birth weight (BW) ≤1250 grams, expected to receive intermittent feeds via gastric tubes were considered eligible. Exclusion criteria included an expected death within 72 h of birth, infants’ clinical condition is deemed as unstable, major chromosomal or congenital anomalies and gastrointestinal complications such as intestinal perforation prior to enrollment.

Study procedures

After obtaining informed consent, eligible infants were randomized 1:1 using a predetermined random number sequence to either GRV or No-GRV groups. Randomization was further stratified by birth weight: ≤800 and 801–1250 g. For multiple births, all infants were randomized to the same treatment group. Infants were enrolled into the study prior to advancing feeds beyond the trophic feeding volume (10–20 ml/kg/d). GRV was not assessed in both groups during trophic feedings per our existing practice. During feeding advancement beyond the trophic feeding volumes, gastric residuals were assessed prior to each feed in the GRV group and were not routinely assessed in the No-GRV group. If there were concerns for feeding intolerance, GRV could be assessed in the No-GRV group after a clinician’s order. Clinicians were notified by the nursing staff if the gastric residual volume was greater than 50% of the prior feeding volume or if the gastric residual was bilious. There was no standard protocol in our NICU dictating what the clinicians would do with a particular quantity of gastric residual volume. The handling of gastric residual volume was at the discretion of the clinical providers. Infants in both groups had serial abdominal examinations and measurement of abdominal girths every 6 hours by the nursing staff per our unit practice. Feeding initiation and advancement of feedings was based on the standard NICU protocol. Feeds were initiated with mother’s own milk or donor human milk at 1 ml every 3 hours in infants with BW <750 g and 2 ml every 3 hours in infants with BW 750–1250 g. After maintaining trophic volumes for 5 days in infants with BW <1000 g and for 2 days with BW 1000–1250 g, feeds were advanced by the volume at initiation daily. Human milk was fortified with human milk fortifier to 22 Cal/oz at a feeding volume of 80 ml/kg/d and to 24 Cal/oz at feeding volume of 100 ml/kg/d. Infants were weaned off donor human milk at 34 weeks postmenstrual age and weight >1500 g.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the number of days to reach full enteral feeding volume (120 ml/kg/d). We chose 120 ml/kg/d as the goal feeding volume as some clinicians restrict the total fluid intake and would not advance feeds beyond this volume. Secondary outcomes included frequency of feeding interruptions, number of incomplete feeds, feeds with >50% residual in the GRV group, frequency of residual checks in the No-GRV group due to clinical concerns, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), weight velocity at 4 weeks after birth and at 36 weeks post menstrual age, parenteral nutrition days, duration of central lines and length of hospital stay. We also collected data on incidence of late-onset sepsis, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), PDA treatment, chronic lung disease, intra-ventricular hemorrhage, and retinopathy of prematurity. NEC was classified using modified Bell criteria [Citation11]. Late-onset sepsis was defined as clinical signs of sepsis with a positive blood culture after 7 days of age. Chronic lung disease was defined as an oxygen requirement at 36 weeks postmenstrual age. Intraventricular hemorrhage was defined per Papile classification [Citation12]. A pediatric ophthalmologist evaluated all infants for retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) and the highest stage of ROP and its treatment were recorded. Weight gain velocity at 4 weeks of age and at 36 weeks post-menstrual age were calculated by exponential method. The 2013 Fenton growth charts were used to obtain Z-scores.

Sample size

A total of 146 infants were required to detect a 20% difference in days to reach full enteral feedings to obtain 80% power with a type 1 error rate of 5% using a 2-sided t test. We used the historical data of duration to reach full feeding in our NICU for infants weighing <1,250 gram (16.4 ± 7.3 days) for power and sample size calculation.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using intention to treat approach. Data are presented as mean ± SD and compared using 2-sided t test when normally distributed. Median (IQR) was compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-parametric data. For categorical data, Fisher exact test was conducted. A p value of less than .05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 software

Results

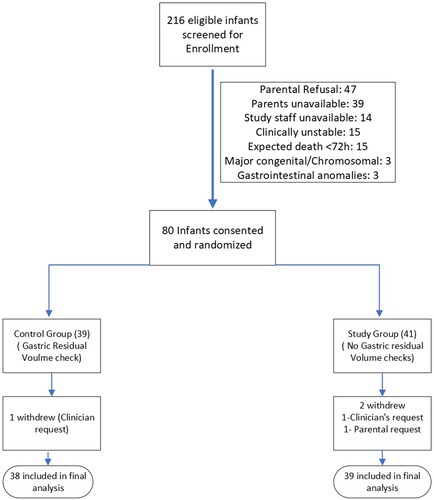

A total of 216 infants were eligible for study enrollment between May 2019 and October 2021. Of these eligible infants, 80 consented for the study and were randomized: 39 to the GRV group and 41 to the No-GRV group. Three infants were withdrawn (1 due to parental request, 2 at clinician request) (). A predetermined interim data analysis at 50% recruitment showed no difference in the primary outcome and assuming the same mean and standard deviations, no significant difference between the two groups using the Welch t-test, if we increase the sample size to the target 146 participants. The revised sample estimate based on the interim data requires a total of 354 infants to detect a 20% difference in days to reach full enteral feedings to obtain 80% power with a type 1 error rate of 5% using a 2-sided Welch t-test. On the recommendation of our Data Safety Monitoring Committee, the study was discontinued.

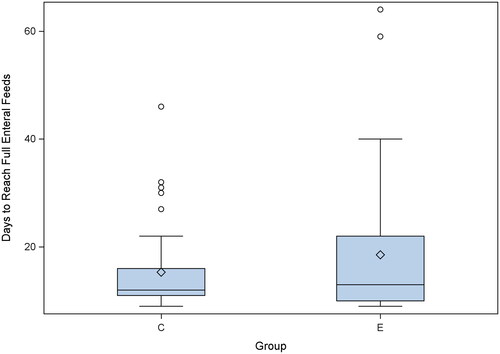

There were no differences in maternal and baseline neonatal characteristics between the two groups (). There was no significant difference between the two groups in days to reach full enteral feeding volume. illustrates the distribution of days to reach full enteral feeds in the GRV and the No-GRV groups. The GRV group attained full enteral feeds at a median of 12 days (IQR:5) and the No-GRV group at 13 days (IQR:9). Sub-group analysis on days to reach full enteral feeds based on pre-specified birth weights did not show a significant difference between the GRV and No-GRV groups [(≤800g: GRV group: 25.5 ± 2.8; No-GRV 26.7 ± 3.2) (801–1250 g: GRV group:15.9 ± 2.7; No-GRV group:11.8 ± 0.4)]. The median duration of parenteral nutrition [GRV group: 12 (5); No-GRV group: 14 (11)] and duration of central venous lines (GRV group: 12.5 (5); No-GRV group: 14 (11)) were also not statistically different between the two groups. Feeding was withheld in 15 infants (39.5%) in the GRV group and in 8 infants (20.5%) in the No-GRV group (p = .08). Infants in the GRV group had 28 feeds in which the gastric residual volume was greater than 50% of the prior feeding and subsequently received 11 incomplete feeds due to concern for gastric residual. No infant in the No-GRV group received incomplete feed.

Figure 2. Distribution of time of achieving full enteral feeding between the group that has assessment of gastric residual volume (C) compared to those whose gastric residual volume were not assessed (E).

Table 1. Demographic and baseline characteristics.

There were no differences in the secondary outcomes between the two groups (). One infant in the GRV and one in the No-GRV group developed stage- 2 NEC. There were no deaths in either group. Growth velocity at 4 weeks and at 36 weeks post-menstrual ages was not different between the 2 groups.

Table 2. Secondary outcomes and complications.

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial, we examined the differences in time to attain full enteral feeding and feeding complications in infants whose GRV were assessed prior to each feed versus those who were not. Our study did not demonstrate a difference in time to full enteral feeds, weight gain velocity or length of hospital stay between the GRV assessment and the No-GRV assessment groups. Gastric residuals are used often to guide feeding therapy because of the belief that a certain amount of GRV and/or abdominal distention reflects feeding intolerance [Citation13]. However, the relationship between GRV and an inability to tolerate gavage feedings is unclear. Relying on GRV to advance feeds in preterm infants can result in delays in the establishment of full enteral nutrition and therefore prolonged parenteral nutrition and central line usage. An arbitrary GRV of greater than 50% of the feeding volume is often used as a marker of feeding intolerance. A prospective study by Shulman et al. showed the mean GRV in preterm infants prior to full gavage feeding being achieved was 3.3 ml/kg/day and the mean number per day of GRVs greater than 50% of the previous feeding prior was 0.05 (range:0–0.75) [Citation14].

Singh et al. found that avoiding routine assessment of gastric residual volume before feeding advancement did not shorten the time to reach full feeds in preterm infants with birth weight between 1500 and 2000 g [Citation8]. Torrazza et al. found no difference in amount of feeding at 2 and 3 weeks of age, growth, days on parenteral nutrition or days to attain full enteral nutrition when GRV was not evaluated [Citation15]. Parker et al. found increased delivery of enteral nutrition as well as improved weight gain and earlier hospital discharge when gastric residual evaluation was omitted but did not find a significant difference in time to reach full enteral feeds [Citation9]. Interestingly, studies by Parker et al. and Torrazza et al. were from the same institution. They had an institutional feeding algorithm that dictated evaluation for NEC based on the gastric residual volume and the nature of gastric aspirate. Radiographs were obtained for GRV greater than 50% of the feeding volume and for bilious residuals. Our study did not have such an algorithm and it was left to the clinicians’ discretion on how to manage excessive gastric or bilious residuals in the infants in the GRV assessment group. Our usual practice was to intervene for GRV greater than 50% of feeding volume, but the approach seemed to have changed during the study period. There was a variability among clinicians’ approach and only 39% of feeds with GRV greater than 50% of the previous feed were withheld. Premature infants tend to have higher gastric residuals in the first few days of life [Citation14]. However, we did not assess gastric residual volumes in either group during the first 3–5 days of enteral feeding, a period during which checking GRV might have caused feeding interruptions. Though statistically insignificant, the incidence of moderate to large PDA and IVH was high in the study group. All these factors may have contributed to lack of difference in the primary outcome in our study.

Kaur et al. and Thomas et al. found that infants reached full feeds faster when abdominal circumference was used to assess feeding intolerance compared GRV assessment [Citation16,Citation17]. We measured abdominal circumference in both the GRV and the No-GRV groups in our study and hence cannot compare the benefits of one practice over the other.

Similar to previous studies, we found no significant difference between feeding complications in those infants who had residuals monitored vs those who did not. The practice of routine GRV monitoring is based on studies that demonstrated a relationship between elevated gastric residual volumes and the risk of NEC [Citation18,Citation19]. Two recent retrospective studies did not show an association between GRV and NEC [Citation20,Citation21]. None of the prospective studies on GRV evaluation had NEC as the primary outcome variable and hence did not have sufficient power to evaluate the effects on NEC. Our study was not powered to evaluate NEC which makes it difficult to interpret the results as well.

Strengths of this study include the prospective randomized controlled design with appropriate sample size and power calculations along with a provision of an interim analysis. The latter was responsible for discontinuing the trial when the interim analysis demonstrated a negative outcome with reference to our hypothesis. The major weakness is the variability in managing the GRV among the clinical providers, which may affect the duration of attaining full feedings, our primary outcome. On the other hand, this weakness may turn out to be a strength because it allows for the result to be more generalizable in clinical practice. We also had a lower enrollment rate (37%) in the study due to parental refusal and unavailability to obtain in-person consent. Having a provision for obtaining phone consent might have helped improve the enrollment rate. Another limitation of this study is the inability for providers to be blinded to the study group, making it difficult to avoid bias.

Conclusion

There was no significant difference in attaining full feeding in preterm infants whose gastric residual volume was assessed vs those whose gastric residual volume was not assessed before the next feeding. We speculate that the data adds to the argument that assessing gastric residuals with each feed is of questionable benefit to the premature neonate and may be eliminated in our practice without causing harm.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Deborah Ruth and Ann Pokelsek, our research nurses, for their help in patient consenting and data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mihatsch WA, von Schoenaich P, Fahnenstich H, et al. The significance of gastric residuals in the early enteral feeding advancement of extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2002;109(3):457–459.

- Riezzo G, Indrio F, Montagna O, et al. Gastric electrical activity and gastric emptying in term and preterm newborns. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2000;12(3):223–229.

- Li YF, Lin HC, Torrazza RM, et al. Gastric residual evaluation in preterm neonates: a useful monitoring technique or a hindrance? Pediatr Neonatol. 2014;55(5):335–340.

- Fanaro S. Feeding intolerance in the preterm infant. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89(Suppl 2):s13–s20.

- Lucchini R, Bizzarri B, Giampietro S, et al. Feeding intolerance in preterm infants. How to understand the warning signs. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(Suppl 1):72–74.

- Ehrenkranz RA, Dusick AM, Vohr BR, et al. Growth in the neonatal intensive care unit influences neurodevelopmental and growth outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1253–1261.

- Elia S, Ciarcia M, Miselli F, et al. Effect of selective gastric residual monitoring on enteral intake in preterm infants. Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48(1):30.

- Singh B, Rochow N, Chessell L, et al. Gastric residual volume in feeding advancement in preterm infants (GRIP study): a randomized trial. J Pediatr. 2018;200:79–83.e1.

- Parker LA, Weaver M, Murgas Torrazza RJ, et al. Effect of gastric residual evaluation on enteral intake in extremely preterm infants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(6):534–543.

- Tume LN, Woolfall K, Arch B, et al. Routine gastric residual volume measurement to guide enteral feeding in mechanically ventilated infants and children: the GASTRIC feasibility study. Health Technol Assess. 2020;24(23):1–120.

- Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg. 1978;187(1):1–7.

- Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, et al. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. 1978;92(4):529–534.

- Neu J, Zhang L. Feeding intolerance in very low-birthweight infants: what is it and what can we do about it? Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2005;94(449):93–99.

- Torrazza RM, Parker LA, Li Y, et al. The value of routine evaluation of gastric residuals in very low birth weight infants. J Perinatol. 2015;35(1):57–60.

- Shulman RJ, Ou CN, Smith EB. Evaluation of potential factors predicting attainment of full gavage feedings in preterm infants. Neonatology. 2011;99(1):38–44.

- Kaur A, Kler N, Saluja S, et al. Abdominal circumference or gastric residual volume as measure of feed intolerance in VLBW infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60(2):259–263.

- Thomas S, Nesargi S, Roshan P, et al. Gastric residual volumes versus abdominal girth measurement in assessment of feed tolerance in preterm neonates: a randomized controlled trial. Adv Neonatal Care. 2018;18(4):E13–E19.

- Cobb BA, Carlo WA, Ambalavanan N. Gastric residuals and their relationship to necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1 Pt 1):50–53.

- Bertino E, Giuliani F, Prandi G, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis: risk factor analysis and role of gastric residuals in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(4):437–442.

- Purohit G, Mehkarkar P, Athalye-Jape G, et al. Association of gastric residual volumes with necrotising enterocolitis in extremely preterm infants a case-control study. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181(1):253–260.

- Riskin A, Cohen K, Kugelman A, et al. The impact of routine evaluation of gastric residual volumes on the time to achieve full enteral feeding in preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2017;189:128–134.