Abstract

Objective

Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for placenta accreta spectrum is used to control maternal hemorrhage during cesarean hysterectomy. This study aimed to assess the efficacy of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for placenta accreta spectrum by examines the change in the quantitative blood loss after applying resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included patients with placenta accreta spectrum who required cesarean hysterectomy (n = 37) between 2003 and 2022 at a tertiary care center. Patients were divided into two groups (with resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta, n = 13; without resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta, n = 24). The quantitative blood loss was compared between the groups. Generalized linear mixed models were used to examine changes in quantitative blood loss during cesarean hysterectomy after resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta was applied. The operating surgeon was set as the random effect.

Results

Operation time did not differ significantly between the groups (p = .09). The quantitative blood loss was significantly higher in patients who did not undergo resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (2160 g) than in patients who did (1110 g; p < .01). Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta significantly decreased the quantitative blood loss during cesarean hysterectomy (partial regression coefficient, 2312; 95% confidence interval, 49–4577; p < .05).

Conclusion

Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta decreased the quantitative blood loss during cesarean hysterectomy in patients with placenta accreta spectrum without significantly increasing the operation time. This suggests that resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta is effective in patients with placenta accreta spectrum.

Introduction

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) is a notable obstetric complication that can cause life-threatening bleeding. It is associated with maternal morbidity with a mortality rate as high as 7% [Citation1,Citation2]. A history of placenta accreta is a risk factor for subsequent placenta accreta, and as the cesarean birth rate has increased, the incidence of PAS has increased 10-fold over the past 50 years in the United States [Citation3].

For women with PAS, cesarean hysterectomy is considered the principal and preferred method for delivery. In developed countries, PAS is the most common reason for cesarean hysterectomy [Citation4]. In Japan, PAS is diagnosed in approximately 1 in 5000 deliveries [Citation5]. Peripartum hysterectomy is technically challenging, as massive blood transfusion may be required due to intraoperative hemorrhage, especially in patients with PAS. To minimize intraoperative hemorrhage, new treatment options have been reported, including the ligation of the internal iliac artery or uterine artery and placement of a balloon catheter in the iliac artery [Citation6]. Despite these adjuvant strategies, massive bleeding due to PAS still occurs and is difficult to overcome [Citation7].

The accumulation of experience in managing patients with gynecological conditions, various minimum invasive techniques such as uterine artery embolization have been developed to preserve fertility in patients who desire it [Citation8].

In 2005, Shih et al. reported that intraoperative bleeding in patients with PAS is reduced with the use of a common iliac artery balloon occlusion (CIABO) for temporary occlusion of blood flow during cesarean hysterectomy [Citation9]. Therefore, the prophylactic use of CIABO has been used in patients with PAS undergoing surgery for placenta previa at our institution since 2011. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA), another minimally invasive resuscitative method, was initially intended for the surgical treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms [Citation10] and was subsequently applied to traumatic hemorrhagic shock and the field of obstetrics [Citation11]. Therefore Prophylactic placement of REBOA has grown to be part of the surgical plans to control intraoperative hemorrhage in cases of abnormal placentation [Citation12]

As the targeted balloon placement area of REBOA is more available than that of CIABO in pregnant patients, prophylactic REBOA has been used to control intraoperative blood loss at our institution since 2014. During the course of cesarean hysterectomy using REBOA, the balloon is inflated or deflated at the discretion of the obstetrician.

Though several studies have reported the use of REBOA for temporary aortic occlusion in obstetric patients with massive hemorrhage, the efficacy of prophylactic REBOA for cesarean hysterectomy due to PAS remains unclear. Therefore, this study investigated the effect of the prophylactic use of REBOA in patients with PAS undergoing cesarean hysterectomy.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included patients with PAS who delivered via cesarean section and underwent cesarean hysterectomy at (hospital name withheld) between 1 January 2003 and 31 March 2022. Because the final degree of abnormal placentation confirm pathologically after the cesarean hysterectomy, the study includes patients who have consented to hysterectomy without prior procedure for placenta removal. Patients were divided based on the use of REBOA (with REBOA, n = 13; without REBOA, n = 24). The study was approved by and conformed to the regulations of the ethics committee of Fukushima Medical University, which is regulated by local policy and national law and is in compliance with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

PAS was diagnosed in patients with a history of cesarean section based on prenatal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings. Prenatal ultrasound findings suggestive of PAS included loss of the retroplacental hypoechoic clear zone, loss of the bladder wall-uterine interface, presence of placental lacunae, and hypervascularity of the interface between the uterine serosa and bladder wall shown on color Doppler imaging [Citation13]. Prenatal MRI findings suggestive of PAS included focal thinning or absence of the myometrium at the site of placental implantation, a nodular interface between the placenta and uterus, a mass effect of the placenta on the uterus causing an outer bulge, heterogeneous signal intensity within the placenta, dark intraplacental bands shown on T2-weighted images, and the loss of the tissue plane between the placenta and bladder wall [Citation14,Citation15]. The diagnosis of PAS was pathologically confirmed. Placenta accreta was pathologically diagnosed when chorionic villi were implanted directly on the surface of the myometrium without intervening decidua, whereas placenta increta was pathologically diagnosed when chorionic villi were identified within the myometrium. Lastly, placenta percreta was pathologically diagnosed when villous tissue was observed adjacent to adipocytes or in extrauterine structures such as the bladder [Citation16].

Data regarding maternal and obstetric outcomes were retrieved from the patients’ medical records including maternal age at delivery, number of previous cesarean sections, gestational age at delivery, and pathological findings in the placenta. Obstetric outcomes included birth weight and the pH of the umbilical arteries of the newborns. The operative time and quantitative blood loss were also retrieved; quantitative blood loss was measured as the contents of the suction canister in the operating room and the weight of the surgical pads [Citation17].

After general anesthesia, intubation, and ureteral catheter placement, a 7-Fr sheath was placed via the right femoral artery under the guidance of a surface ultrasound. An occlusion balloon catheter (Tokai Medical Products, Inc., Kasugai, Japan) was then placed above the celiac artery under X-ray guidance. Fluoroscopy was used to confirm the correct deployment of the REBOA into zone 1 of the aorta. The exploratory balloon was then filled with 10 ml of saline water immediately before the cesarean section [Citation18]. The occlusion of distal aortic flow was confirmed by a temporal decrease in oxygen saturation at the left great toe, and REBOA placement was then performed by an emergency physician or an obstetrician who are extensive experience in intervention radiology [Citation19,Citation20]. When necessary, ureteral catheters were used to avoid urinary tract injuries during cesarean hysterectomy [Citation21].

Seven trained obstetricians performed the cesarean sections and hysterectomy procedures. The abdominal incision was initiated at the symphysis pubis and extended vertically around the umbilicus for further extension. After the location of the placental margin was confirmed using intraoperative ultrasonography, a transverse incision was made in the uterine fundus to prevent intraoperative placental injury during the delivery of the infant [Citation22]. Soon after delivery, a single-layer uterine suture was placed. The round ligament was cut, and the broad ligament was exposed. The proper ligament of the ovary and the fallopian tube was also cut. As the vessels along the ovarian ligament are engorged in pregnant patients, especially in those with PAS, the M cross double ligation method was used for the ovarian ligament [Citation23]. The anterior and posterior lobes of the broad ligament were cut; the ureter was identified using the ureteral catheter. Then, the bladder was separated from the uterus. Finally, the parametrium and paracervix were cut and the balloon was inflated for a maximum of 15 min as massive hemorrhage is most likely to occur when the parametrium and paracervix are cut. After resection of the uterus, the vaginal canal was closed, and a drain was inserted to Douglas pouch to confirm the presence of postoperative bleeding. The REBOA and ureteral catheter were removed within the operating room, while the drain remained until at least postoperative day 1.

The maternal characteristics and obstetric outcomes were summarized in each patient group. The Mann-Whitney U test and chi-squared test (Fisher’s exact test) were used to compare the continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) were used to examine the changes in the quantitative blood loss after the use of REBOA. In the GLMM analysis, the operating surgeon was set as the random effect, and the use of the ureteral catheter and REBOA were set as the fixed effects. The partial regression coefficient (B) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the quantitative blood loss were then calculated using GLMM analysis. SPSS version 26 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set at p < .05.

Results

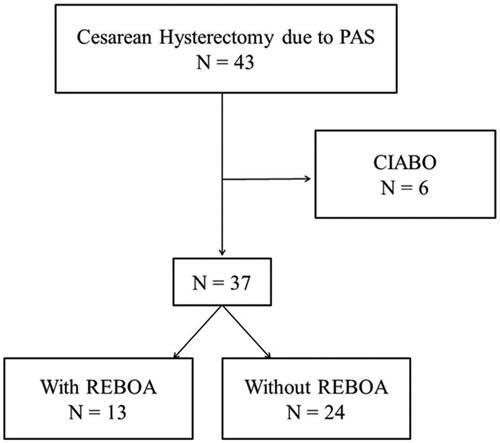

A total of 43 patients with PAS required cesarean hysterectomy at our institution between 2003 and 2022. However, six patients were excluded as they had undergone CIABO. The final analysis included 37 patients (with REBOA, n = 13; without REBOA, n = 24) ().

Figure 1. Study flowchart. A total of 37 cesarean hysterectomies were part of the study, including 13 with REBOA and 24 without. Abbreviations: PAS: placenta accreta spectrum; REBOA: resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta; CIABO: common iliac artery balloon occlusion.

There were no significant differences in median maternal age (p = .39), gestational age at delivery (p = .09), number of previous cesarean sections (p = .31), or pathological severity of PAS (p = .21) between the patient groups (). Ureteral catheters were used more frequently in patients who underwent REBOA (92.3% vs 53.4%, p < .05). The median birth weight (p = .12), umbilical artery pH (p = .10), and operation time (p = .863) did not significantly differ between the groups. However, the quantitative blood loss was significantly lower in patients who underwent REBOA (1110 g) than in those who did not (2160 g) (p < .05).

Table 1. Obstetric outcomes.

The use of REBOA resulted in significantly less quantitative blood loss (partial regression coefficient, 2312; 95% CI, 49–4577; p < .05; ). No balloon catheter-related complications, including thromboembolic disease, hematoma, or artery rupture occurred in patients who underwent REBOA.

Table 2. Generalized linear mixed model analysis of the association between REBOA and quantitative blood loss during cesarean hysterectomy.

Discussion

Few studies have validated the efficacy of REBOA in reducing intraoperative blood loss during cesarean hysterectomy in patients with PAS. In this study, patients who underwent REBOA were more likely to undergo ureteral catheter insertion. The quantitative blood loss was significantly lower when REBOA was used, with no effects on the operation time.

Cesarean hysterectomy for PAS is challenging compared to other cesarean operations due to the potential risk of massive blood loss and injuries to other organs, including the urinary tract [Citation17,Citation24]. Therefore, the outcomes of cesarean hysterectomy are dependent on the surgical experience of the obstetrician. The results of the GLMM analysis conducted in this study suggest that REBOA reduces quantitative blood loss regardless of the attending surgeon. In this study, the use of REBOA lowered the quantitative blood loss during cesarean hysterectomy by approximately 2312 g (95% CI: 49–4577 g).

The use of REBOA has recently increased, especially in the field of trauma surgery, and the procedure is considered a safe and effective intervention for the management of abdominal and pelvic hemorrhage [Citation25]. Moreover, REBOA has been reported to have been used for postpartum hemorrhage, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, tumor surgery, traumatic hemorrhage, and ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms [Citation26], and has been reported to prevent postpartum hemorrhage. Planned cesarean sections with prophylactic REBOA result in less overall blood loss [Citation27], fewer transfusions, and more favorable hemorrhage-related maternal outcomes [Citation12, Citation28, Citation29]. However, the clinical efficacy of REBOA in patients with PAS undergoing cesarean hysterectomy remains unclear.

A previous study reported successful hemorrhage control, which was quantitative at 3000 g of blood loss, with the prophylactic use of REBOA in patients with placenta previa [Citation30]. Additionally, another previous study reported that REBOA was effective for the emergent management of uncontrolled postpartum hemorrhage after cesarean hysterectomy in patients with PAS [Citation7]. Patients with extensive PAS who underwent REBOA had a significantly lower quantitative blood loss than those who underwent CIABO in yet another previous study, although the patients who underwent REBOA did not undergo cesarean hysterectomy [Citation31]. Among patients with PAS undergoing cesarean delivery for the first time, the use of REBOA has been shown to reduce the rate of patients requiring more than four units of packed red blood cells (PRBC) [Citation32]. These results suggest that the use of REBOA during cesarean hysterectomy significantly decreases massive postpartum hemorrhage; furthermore, these findings are consistent with the results of the current study as four units of PRBC are equal to 2000 g of blood [Citation33].

One alternative option for balloon occlusion catheter placement during cesarean hysterectomy is the use of common iliac artery balloon occlusion (CIABO) [Citation9]. Unlike REBOA, which places the balloon in the descending aorta, CIABO places the balloon at both common iliac arteries, allowing for more selective occlusion of blood flow [Citation9]. While CIABO has been shown to be effective in reducing intraoperative blood loss [Citation34,Citation35], our institution ultimately chose to use REBOA due to concerns over collateral circulation and the possibility of vessel injury associated with CIABO. Collateral circulation connecting the internal and external iliac arteries could potentially maintain blood flow to the uterus even if the internal iliac artery is occluded [Citation36], making it difficult to control bleeding through internal iliac artery occlusion alone. Additionally, CIABO requires two punctures from both external iliac arteries [Citation37], increasing the risk of vessel injury compared to REBOA, which typically only requires puncturing one side of the external iliac artery.

The optimal position of the balloon in REBOA requires further research. Zone I of the aorta extends from the origin of the left subclavian artery to the celiac artery and is a potential zone of occlusion; zone II extends from the celiac artery to the lowest renal artery and is a no-occlusion zone; and zone III extends from the lowest renal artery to the aortic bifurcation [Citation38]. Although no complications associated with REBOA were observed in this study, REBOA increases proximal blood pressure and may induce distal ischemia of the visceral organs and lower extremities, resulting in an inflammatory response that may be life-threatening or limb-threatening. Therefore, the benefits and risks of REBOA must be considered for each patient. In this study, the balloon was deployed to zone 1 as the obstetricians did not have significant experience with REBOA. However, zone 3 should instead be used to reduce complications of REBOA inflation.

Although evidence for the safety and efficacy of prophylactic REBOA use have been established, a recent publication examining evidence-based guidelines for managing PAS has raised doubts about the effectiveness and potential complications associated with prophylactic REBOA placement [Citation12,Citation29,Citation39–41]. One study suggested that emergent REBOA placement may be linked to vascular complications, which could be due to smaller vessel lumens and distorted vascular anatomy caused by the gravid uterus in female patients [Citation42]. However, this concern should be applicable to both prophylactic and emergent placements. Because of its potential complication, we decided not to use REBOA for the cases with HDP [Citation18]. With the increasing rate of cesarean section, it is likely that the incidence of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) cases requiring cesarean hysterectomy will continue to rise. This highlights the need to accumulate cases where resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) is used, and further studies are required to investigate the appropriate candidates for REBOA use in the future.

The primary strength of the current study is that the data were derived from a single tertiary care fetal medicine unit at which all patients were managed by obstetricians with equivalent training for obstetric emergencies [Citation18,Citation20]. As a result, the indications for REBOA, zone of balloon deployment, and timing of REBOA inflation and deflation were consistent, and the obstetricians were aware of the time during the cesarean hysterectomy at which massive hemorrhage was most likely to occur.

However, this study had few limitations. First, more favorable outcomes have been reported in patients with placenta accreta in a multicenter study in which a multidisciplinary approach was used [Citation4], suggesting that cesarean hysterectomy is technically challenging, and maternal morbidity could be influenced by the operating surgeon. To overcome this limitation, the operating surgeon was set as a random effect in the GLMM analysis in this study to minimize the influence of the operating surgeon. Second, although the degree of placental invasion of the myometrium was confirmed histologically in all patients, the population of this study was small. Therefore, a study that includes more patients will allow for a subgroup analysis regarding the effect of REBOA on cesarean hysterectomy in patients with different severities of PAS. Third, the majority of accreta centers that use REBOA inflate in ZONE3, the finding of the advantages of replacing REBOA ZONE1 may not be generalized. Finally, this study analyzed retrospectively and not assigned at random. Therefore selection bias due to conduct on preexisting data rather than selecting patients randomly could occurred and there may be confounding variables that affect the results.

Conclusions

Our study showed that REBOA is an effective technique to prevent intraoperative blood loss during cesarean hysterectomy in patients with PAS. The use of REBOA in cases of cesarean hysterectomy is still a relatively new technique, and its effectiveness and safety are still being studied. A multidisciplinary team, the potential benefits and risks need to be carefully considered on a case-by-case basis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, H.K., upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006;367(9516):1066–1074. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68397-9.

- Kayem G, Davy C, Goffinet F, et al. Conservative versus extirpative management in cases of placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(3):531–536. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000136086.78099.0f.

- Miller DA, Chollet JA, Goodwin TM. Clinical risk factors for placenta previa-placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(1):210–214. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70463-0.

- Eller AG, Bennett MA, Sharshiner M, et al. Maternal morbidity in cases of placenta accreta managed by a multidisciplinary care team compared with standard obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 Pt 1):331–337. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182051db2.

- Kyozuka H, Yamaguchi A, Suzuki D, et al. Risk factors for placenta accreta spectrum: findings from the Japan environment and children’s study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):447. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2608-9.

- Eller AG, Porter TF, Soisson P, et al. Optimal management strategies for placenta accreta. BJOG. 2009;116(5):648–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02037.x.

- Ji SM, Cho C, Choi G, et al. Successful management of uncontrolled postpartum hemorrhage due to morbidly adherent placenta with resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta during emergency cesarean section - a case report. Anesth Pain Med. 2020;15(3):314–318. doi: 10.17085/apm.19051.

- Russ M, Hees KA, Kemmer M, et al. Preoperative uterine artery embolization in women undergoing uterus-preserving myomectomy for extensive fibroid disease: a retrospective analysis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2022;87(1):38–45. doi: 10.1159/000521914.

- Shih JC, Liu KL, Shyu MK. Temporary balloon occlusion of the common iliac artery: new approach to bleeding control during cesarean hysterectomy for placenta percreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(5):1756–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.033.

- Edwards WS, Salter PP Jr, Carnaggio VA. Intraluminal aortic occlusion as a possible mechanism for controlling massive intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Surg Forum. 1953;4:496–499.

- Gupta BK, Khaneja SC, Flores L, et al. The role of intra-aortic balloon occlusion in penetrating abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1989;29(6):861–865. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198906000-00026.

- Manzano-Nunez R, Escobar-Vidarte MF, Naranjo MP, et al. Expanding the field of acute care surgery: a systematic review of the use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in cases of morbidly adherent placenta. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018;44(4):519–526. doi: 10.1007/s00068-017-0840-4.

- Comstock CH, Love JJ Jr, Bronsteen RA, et al. Sonographic detection of placenta accreta in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(4):1135–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.024.

- Comstock CH. Antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta: a review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26(1):89–96. doi: 10.1002/uog.1926.

- Lax A, Prince MR, Mennitt KW, et al. The value of specific MRI features in the evaluation of suspected placental invasion. Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.10.007.

- Bartels HC, Postle JD, Downey P, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum: a review of pathology, molecular biology, and biomarkers. Dis Markers. 2018;2018:1507674. doi: 10.1155/2018/1507674.

- Suzuki N, Kyozuka H, Fukuda T, et al. Late-diagnosed cesarean scar pregnancy resulting in unexpected placenta accreta spectrum necessitating hysterectomy. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2020;66(3):156–159. doi: 10.5387/fms.2020-14.

- Kyozuka H, Sugeno M, Murata T, et al. Introduction and utility of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for cases with a potential high risk of postpartum hemorrhage: a single tertiary care center experience of two cases. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2022;68(2):117–122. doi: 10.5387/fms.2022-01.

- Soeda S, Hiraiwa T, Takata M, et al. Unique learning system for uterine artery embolization for symptomatic myoma and adenomyosis for Obstetrician-Gynecologists in cooperation with interventional radiologists: evaluation of UAE from the point of view of gynecologists who perform UAE. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(1):84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.08.008.

- Soeda S, Kyozuka H, Kato A, et al. Establishing a treatment algorithm for puerperal genital hematoma based on the clinical findings. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2019;249(2):135–142. doi: 10.1620/tjem.249.135.

- Norris BL, Everaerts W, Posma E, et al. The urologist’s role in multidisciplinary management of placenta percreta. BJU Int. 2016;117(6):961–965. doi: 10.1111/bju.13332.

- Kotsuji F, Nishijima K, Kurokawa T, et al. Transverse uterine fundal incision for placenta praevia with accreta, involving the entire anterior uterine wall: a case series. BJOG. 2013;120(9):1144–1149. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12252.

- Matsubara S, Kuwata T, Usui R, et al. Important surgical measures and techniques at cesarean hysterectomy for placenta previa accreta. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92(4):372–377. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12074.

- Takeda S, Takeda J, Murayama Y. Placenta previa accreta spectrum: cesarean hysterectomy. Surg J. 2021;7(Suppl 1):S28–S37. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1721492.

- Biffl WL, Fox CJ, Moore EE. The role of REBOA in the control of exsanguinating torso hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(5):1054–1058. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000609.

- Morrison JJ, Galgon RE, Jansen JO, et al. A systematic review of the use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in the management of hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80(2):324–334. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000913.

- Ordoñez CA, Manzano-Nunez R, Parra MW, et al. Prophylactic use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in women with abnormal placentation: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and case series. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84(5):809–818. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001821.

- Cui S, Zhi Y, Cheng G, et al. Retrospective analysis of placenta previa with abnormal placentation with and without prophylactic use of abdominal aorta balloon occlusion. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;137(3):265–270. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12132.

- Wu Q, Liu Z, Zhao X, et al. Outcome of pregnancies after balloon occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta during caesarean in 230 patients with placenta praevia accreta. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2016;39(11):1573–1579. doi: 10.1007/s00270-016-1418-y.

- Russo RM, Girda E, Kennedy V, et al. Two lives, one REBOA: hemorrhage control for urgent cesarean hysterectomy in a Jehovah’s witness with placenta percreta. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(3):551–553. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001602.

- Riazanova OV, Reva VA, Fox KA, et al. Open versus endovascular REBOA control of blood loss during cesarean delivery in the placenta accreta spectrum: a single-center retrospective case control study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;258:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.12.022.

- Ioffe YJM, Burruss S, Yao R, et al. When the balloon goes up, blood transfusion goes down: a pilot study of REBOA in placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2021;6(1):e000750. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2021-000750.

- Franchini M, Capuzzo E, Turdo R, et al. Quality of transfusion products in blood banking. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2014;40(2):227–231. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365840.

- Chou MM, Kung HF, Hwang JI, et al. Temporary prophylactic intravascular balloon occlusion of the common iliac arteries before cesarean hysterectomy for controlling operative blood loss in abnormal placentation. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54(5):493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2014.03.013.

- Minas V, Gul N, Shaw E, et al. Prophylactic balloon occlusion of the common iliac arteries for the management of suspected placenta accreta/percreta: conclusions from a short case series. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(2):461–465. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3436-9.

- Chait A, Moltz A, Nelson JH Jr. The collateral arterial circulation in the pelvis. An angiographic study. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1968;102(2):392–400. doi: 10.2214/ajr.102.2.392.

- Ono Y, Murayama Y, Era S, et al. Study of the utility and problems of common iliac artery balloon occlusion for placenta previa with accreta. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2018;44(3):456–462. doi: 10.1111/jog.13550.

- Stannard A, Eliason JL, Rasmussen TE. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) as an adjunct for hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2011;71(6):1869–1872. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31823fe90c.

- Wei X, Zhang J, Chu Q, et al. Prophylactic abdominalaorta balloon occlusion during caesarean section: a retrospective case series. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2016;27:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2015.12.001.

- Manzano-Nunez R, Escobar-Vidarte MF, Orlas CP, et al. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta deployed by acute care surgeons in patients with morbidly adherent placenta: a feasible solution for two lives in peril. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:44. doi: 10.1186/s13017-018-0205-2.

- Collins SL, Alemdar B, van Beekhuizen HJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of abnormally invasive placenta: recommendations from the international society for abnormally invasive placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(6):511–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.054.

- Whittington JR, Pagan ME, Nevil BD, et al. Risk of vascular complications in prophylactic compared to emergent resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in the management of placenta accreta spectrum. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(16):3049–3052.