ABSTRACT

Both in academia and in everyday discourse, the belief in the (re)production of national ideology and related civil culture(s) within state schools has remained strong. This idea(l) has also become salient among a growing number of educational specialists, anti-colonial activists and policymakers on Sint Maarten, the Dutch or southern side of the bi-national, Caribbean island St. Martin. Drawing on fourteen months of fieldwork I show how the different elites’ imaginations of the nation were remade and unmade by the teacher and pupils in a sixth-grade classroom in a public school. Lingering colonial relations, ongoing migration and popular culture challenged a well-bounded, shared imagination of the educated Sint Maartener.

Introduction

Over the past few years, it has become bon-ton for Dutch politicians to argue for the singing of Het Wilhelmus Footnote1 (the Dutch anthem) in primary schools, the visiting of national museums with pupilsFootnote2 and the teaching of standard Dutch from an increasingly young age. These measures seem to be based upon the popular belief that pupils in public primary schools should learn a positive national belonging. Both explicitly (through singing the national anthem, learning about national symbols) and implicitly (language measures and social norms; the ‘civil culture’) the imagined nation is to be transmitted to pupils. In the Netherlands, these measures have thus far remained only a wish of a growing number of politicians. But in my fieldwork site, the Caribbean island and former Dutch colony Sint Maarten, I encountered academics, activists, and educators, who invented measures to use public schooling to shape a particular Sint Maartener belonging.

As I spent seven out of fourteen months of fieldwork with a group of sixteen sixth graders (11–13 years) and their teacher in a public primary school on the island, I learned that the processes of transmission necessary for these national imaginaries to become shared amongst pupils did not actually take place. Just like the different authors in Levinson et al. (Citation1996) have argued, the imagination and production of the ‘educated national person’ was contested by teachers (those imagined as direct transmitters) and the pupils (ideal recipients).

In this article, I will show how three movements within one classroom disrupted the elites’ belief in education as transmission and the related notion of belonging as primarily national. First I introduce teacher Jones who remade national belonging in relation to his own transnational ties, both territorial and religious. Secondly, pupils made a move similar to that of their teacher, remaking territorial belonging in relation to their parents’ (is)lands of origin. Thirdly, pupils challenged the perceived territorial order by performing belonging in ways thoroughly influenced by transnational popular culture. In this third movie, the underlying assumptions of national belonging and related essentialist discourses on identities were unmade. Pupils’ relational performances of co-existence defy an understanding of the educated Sint Maartener as someone (let alone a group of people) with lasting and predictable (national) attributes. Relating education to creolisation and ‘Relation’ (Glissant Citation2010 [1990]) sheds new light on the (im)possibility of reproducing an ideal Sint Maartener in this classroom and, arguably, beyond.

The nation and the classroom

The idea that some sort of (re)production of national ideology and civil culture(s) takes place within state schools has long been mainstream in academia and is still widely shared in popular discourse; in schools, teachers turn pupils into citizens of a certain kind (e.g. Schiffauer et al. Citation2004). American educational philosopher John Dewey (Citation2009 [1916]) has described how the relationship between education and society has taken on three distinguishable forms that emerged at different times and still exist today. Schools can be seen as the places where critical, cosmopolitan individuals (world citizens) are shaped, while, they can also be seen as places that turn young people into the specific workers that society needs (Dewey (Citation2009 [1916]), 71). During the nineteenth century, when Europe changed from an arena of empires and kingdoms to one ordered into nations and their own sovereign states, the relation between schools and society often became ‘institutional idealist’ (Dewey (Citation2009 [1916], 73–74). Dewey states that from this time onwards ‘[t]he state furnished not only the instrumentalities of education but also its goal’ (Dewey (Citation2009 [1916]), 75). Belonging to the nation was thus produced in state-financed schools (Dewey Citation2009 [1916]; Levinson and Holland Citation1996, Schiffauer et al Citation2004). The other relations still occur, but national belonging is commonly considered to be one of the goals of schooling, also in post-colonial states (Anderson Citation2003[1983]).

Yet, ethnographic work has shown that people may belong in ways unrelated and uncompromising to the idea of national belonging being primary: they belong to a Christian Kingdom, claim spatial belonging that is regional, or belong through histories and artefacts, family networks or music (e.g. Besson and Olwig Citation2005, Bonilla Citation2013, Feld Citation2012, Gilroy Citation2002, Youkhana Citation2015). Belonging thus refers to a range of practices in which people create an affective relation in and to a place (or thing), while simultaneously shaping boundaries between an imagined ‘us’ and ‘them’ (Antonsich Citation2010, Hedetoft and Hjort Citation2002, Yuval-Davis Citation2006). Geschiere (Citation2009) showed that a claim to ‘autochthony’ is also increasingly tied to the nation, providing it with an emotional claim to the soil. Despite the broad interpretation of belonging, the political order of sovereign states and citizenship often still frames a ‘we’ in nationalist terms, easily adopting related essentialist idea(l)s: i.e. ‘we’ speak, dress, eat and in general act in certain ‘national’ ways. This also always says something about those who do not act as ‘we’ do. The idea(l) of schools as sites of reproduction of the national type of belonging remains dominant as well. This may prevent us from perceiving other ways in which pupils and teachers ‘do’ belonging.

In addition to the above, ethnographic research has challenged the notion that schools are necessarily sites of reproduction. In North American anthropology, the interest in studying education was fuelled by an interest in social reproduction and cultural transmission in non-industrialised societies (Levinson and Holland Citation1996). Since the 1960s, ethnographies on education within this field increasingly highlighted the complications and contradictions between the official goals of schooling as improving the potential of all pupils and the actual practices inside the classroom. Levinson and Holland (Citation1996) argue that through the work of Pierre Bourdieu, schools became scrutinised for the reproduction, normalisation, and legitimation of unequal power relations (see also Sullivan Citation2002, Yon Citation2003). Critical traditions, including neo-Marxism, feminism, critical pedagogy, and antiracism pushed an intersectional approach to discuss the contested formations of identity, belonging and related inequality in schools, paving the way towards emancipation through education (see Freire Citation1996[1970]; Levinson and Holland Citation1996, Suarez-Orozco et al Citation2011). For scientists active in these critical traditions, schools became sites where pupils could contest norms and hierarchies. Reproduction was never fully effective nor the only active process; alternative discourses of belonging were produced too. As Levinson and Holland argue, through these contestations, new, shared senses of belonging were produced within school settings. Contestations thus produced different orders: not necessarily more equal ones, maybe, but shared, lasting orders nonetheless. And yet, amongst policymakers and educators, an agreement about the basic functioning and thus also the possibility of education as socialisation, remains.

Education legislation in the Netherlands throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s provided leeway for immigrants to be schooled in their own languages and cultural habits. However, the belief and the need to believe in cultural socialisation has strengthened. Pupils must be assimilated. Burgerschapsvorming (civic education) has been included in educational legislation in 2006.Footnote3 Schools, through their curriculum, materials, and teachers, teach newcomers (youngsters and migrants) the skills and knowledges of the nation; the ‘civil culture’ (Schiffauer et al. Citation2004). This process is often contested, diversified and incomplete (e.g. Levinson Citation1996, Skinner and Holland Citation1996), but the idea of the potential of schools as a site of social transmission where idea(l)s of the educated person are culturally (re)produced, has remained largely unchallenged (Collins Citation2009, Levinson and Holland Citation1996), and they have since spread around the globe.

Caribbean belonging

Obviously, the imagining of the nation-state and the related role of schools therein differs across the globe. Anderson (Citation2003[1983]) has shown how nationalism was imagined in a variety of waves starting in creole America, then becoming a model in Europe, which was later adopted in post-colonial states. The Caribbean region, modern before modernity and globally connected before globalisation became fashionable in Western academia, poses a challenge to the anthropological imagination of pre-contact peoples and the common ordering of the world (Trouillot Citation1992, Olwig Citation2007). The history of (forced) migration towards and within the Caribbean has allowed people in the region to develop relationships with a plethora of imagined places. The Martinican author Patrick Chamoiseau explained this phenomenon as follows:Footnote4

I would call myself an ‘independist’. But I don’t mean an independence that involves a breaking off – ‘my flag, my language, my borders’- but in the relational way. It means the opposite: ‘leave me to live all my possible interdependencies, my interdependence with the Caribbean, with the Americas, with Africa, with France and Europe etc. That’s what ‘independence’ (in inverted commas) means nowadays.

Chamoiseau and Glissant (re)imagined Martinique and the wider Caribbean archipelago (and eventually the rest of the world), as shaped by and giving shape to creolization, which they later coined as Relation (Chamoiseau Citation2018, Glissant Citation2010 [1990], Citation2008). Creolisation, a linguistic term that emphasised mixing, has been applied to movements that construct the world. These movements – unknown, unpredictable and untraceable – shape people and ‘cultural unities’ in unexpected ways. All and everything is connected and part of Relation (Glissant Citation2010 [1990]; Taking Relation seriously as a process of creolising demands an exploration of different ways of thinking about, knowing and writing the world (e.g. Harris Citation2008, James Citation1989 [1938], Lamming Citation2009, Glissant Citation2008, Citation2010 [1990], Trouillot Citation1992, Citation2002, Walcott Citation1974, Citation1998). Fieldwork must also be done differently. We cannot learn a truth about the stable, lasting world, and represent this as outside of the world and ourselves. Instead, we must learn from our encounters, in which we ourselves change and exchange. None of our assumptions can remain unchallenged. For me, this was not always an easy task. I was continuously faced with my own presuppositions, not only related to my personal history of migration, linguistic abilities, and embodied being, but also in relation to my academic self, thoroughly shaped by an enlightenment discourse of order and autonomous individuals.

St. Martin is a territory of 87 square kilometres, geographically located in the Caribbean basin. Politically, there is a Northern or French side: St-Martin, which is an overseas territory of the French Republic and part of the European Union, and a Southern Dutch Sint Maarten, which has country status within the Kingdom of the Netherlands.Footnote5 Even though the two sides are socially united, politically, financially and also educationally, they remain distinct. My fieldwork took place in schools on the Southern side and thus concern Dutch Sint Maarten. I did not only spend four days per week in two classrooms in one primary school, I also spoke with and hung out with a variety of school personnel, members of school boards, anti-colonial activists and educational policymakers. They shared a belief in the potential of education to create ‘the Sint Maartener’, i.e. a unified national identity. However, how s/he was imagined, and subsequently given shape through educational measures, differed. I loosely divide the politicians, policymakers and activists involved in two elite formations with specific imaginations.Footnote6 The people I assign to the first group were involved in the development of education between 1954 and 2010 when Sint Maarten had formed the Dutch Antilles together with Curacao, Bonaire, Saba, Sint Eustatius and Aruba (Aruba was a member until 1986 when it obtained country status).

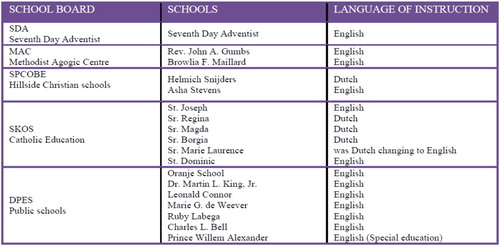

During this period the Dutch Antilles were ruled through a federal government in close collaboration with the Netherlands. This implied thorough cooperation between people with different needs, realities, and demands. The long-lasting cooperation, and need to overcome differences by alluding to what was shared, created a federal sense of belonging. It did not aim for independence or unification but pragmatically allowed for different ways of living together to exist. This federalism had strong ties with a Christian ecumenism and allowed for different religious groups to establish their own schools, also on Sint Maarten, where five Christian school communities blossomed (see ). Some of these schools hired teachers and obtained teaching materials from the Netherlands and the (former) Dutch Kingdom), while others entertained ties with the US or other Caribbean islands.

Figure 1. The school boards and their communities (by ascending size as it was during my fieldwork).

Even though the federal elite still has some influence on educational policies on the island,Footnote7 another elite formation that I will call the nationalist vanguard gained political influence in 2010. Since the middle of the twentieth century, when processes of decolonisation and independence caused unrest throughout the world, the Dutch Kingdom also underwent much-needed change. After Indonesia and Suriname fought for their independence in 1949 and 1975, respectively, Aruba left the federal construction of the Antilles in 1986 and became a separate country within the Kingdom. Referenda were held during the 1990s and 2000s in which the five remaining Dutch Antillean islands choose their island’s specific political relation to the world, the Kingdom and the Netherlands (Benoit Citation2008). On Sint Maarten, almost 70% of the people who voted in the 2000 referendum on the new status opted for becoming a country within the Kingdom, which, after extensive negotiations, eventually took place on the 10th of October 2010. On this day, commonly referred to as 10-10-10, Sint Maarten obtained country status. It was thus no longer tied to the other former Dutch Antilles and could develop its own relationship with the Netherlands.

At this critical moment, those who had the capacity to take part in governing Sint Maarten needed to take responsibility for the new country. As the new developments allowed for a new relationship with the Netherlands (and a possible focus on a united St. MartinFootnote8) a new vanguard of policymakers, politicians, and activists strove to attain power.Footnote9 They had established themselves around the House of Nehesi Publishing house, headed by the sons of Jose Husurell Lake senior, who was himself celebrated as the father of Sint Maarten journalism and one of the few oppositional politicians during the 1950s and 60s (Roitman and Veenendaal Citation2016). Inspired by North American black power movements and romantic nationalism, this vanguard imagined St. Martiners as part of a cultural and nationalist (i.e. African centrist) unity. They believed that ties to the (former) colonies and their Christian remnants should be broken. The freedom that Christian schoolboards enjoyed should be taken away. All schools would then fall under the government’s direct control and all pupils could learn the cultural ways of the locally born ‘autochthones’ of African descendent: the core St. Martiners.Footnote10

With the appointment of Dr. Arrindell, an important member of this elite, as the first minister of Education, Culture, Youth and Sports (ECYS) of the new country Sint Maarten in 2010, this second imagination of belonging gained influence. Just like the federalists who had invested heavily in education, Minister Arrindell believed that public schooling, done properly, could shape a national belonging that would pave the way towards a strong nation and real independence (outside of the Kingdom and together with the Northern part of the island). Important measures were standardising the system, teaching in English only, and revaluing ‘S’Maatin English’ (a local vernacular according to the vanguard, street lingo to many others). Both elites’ idea(l)s thus echoed the (older) educational theories which stated that education (re)produces (national) belonging (i.e. Anderson Citation2003[1983], Collins Citation2009, Levinson and Holland Citation1996, Schiffauer et al Citation2004). The reality in classrooms differed from these theories, however, as both the teacher and the sixth-grade pupils passionately taught me.Footnote11

The teacher’s remake of national belonging

The public school in which I conducted most of my research was located in a migrant neighbourhood.Footnote12 Most inhabitants had come to Sint Maarten between 1970 and 2010, a period during which the population grew rapidly because of the tourist boom.Footnote13 With the tourists and international investors came the service providers from surrounding islands to make the beds and prepare the food.Footnote14 The parents and caretakers of my pupil-respondents mostly worked several of these jobs to support the extended family. Most pupils thus had to cater to themselves in the afternoon, as there was often no money for extracurricular activities or afterschool programmes. Most had been born on Sint Maarten and spoke English well, but they mixed it with the languages of their extended family: Kreyol, Patois and other British West Indian Creoles, Papiamentu, French, Spanish, and Hindi. Pupils lived their various ‘interdependences’, to paraphrase Chamoiseau, and so did their teachers.

‘Sint Maarten can fit 5187 times in Guyana’, teacher Jones had told the pupils in his classroom. He continued venting his dislike for the island: ‘This little world Sint Maarten that is everything to you, is so small. And people from outside will come in and take your jobs and your houses.’ According to teacher Jones, these people also had the right to take those jobs, because people on Sint Maarten were spoiled, much like the pupils in his classroom. He told them,

You are all so spoiled by this welfare state you live in, that you never do good just to do good. You always need the sticker. You are given books and pencil cases and instead of walking to school a bus picks you up. You don’t even have to open your mouth anymore cause we have made food into IV [intravenous, meaning it can be injected].

Teacher Jones, a middle-aged, male teacher who grew up in Guyana, often constructed his own Guyanese belonging in contrast to a negative Sint Maartenness that he ascribed to his sixteen pupils.Footnote15

In between lessons, Jones talked about Guyana and he used examples from Guyana to teach certain subjects. For instance, to discuss trade, teacher Jones introduced an organisation close to his heart: the Caribbean Community (CARICOM). He named some of the countries that were part of this Caribbean trade organisation, starting with Guyana where the headquarters of this organisation were located. And he added, ‘With a passport from a CARICOM country, travel becomes much easier’, and ‘the Guyanese can travel easily, just like Anguillans.’ He continued explaining how Sint Maarten only had a small and meaningless role to play in CARICOM. ‘Sint Maarten is just an observing member. They cannot vote. But cricket may bring them in.’ Pupil Emanuel disagreed with teacher Jones, ‘Cricket dumb!’ he mocked, to which another, Brianna, responded, ‘You are dumb.’ In the meantime, Saphira and Jessica started singing Justin Bieber’s latest song ‘What do you mean?’Footnote16

When one pupil, David, had had enough of the lesson about CARICOM he turned to me asking, ‘Teacher, you coming Carnival?’ It was almost time for the opening of Carnival village where pupils attended shows and parades with friends and family. The most adventurous ones also visited the Jump-Ups (parades that took place during the build-up towards Carnival in which people dance behind trucks with local bands). I responded positively to David. ‘Jouvert also teacher?’ he continued eagerly. I laughed and told him that I would try to get up early to be part of this famous Jump-Up that started at four a clock in the morning. Teacher Jones had overheard our conversation and felt the need to comment. ‘I can’t quarrel’, he said, ‘it’s in your system. You can’t help it.’ While David had ignored teacher Jones’ comment, it lingered in my thoughts. Had teacher Jones proposed that David’s ‘system’, his ‘authentic core’, pushed him towards Carnival? On several occasions teacher Jones seemed to imply that pupils could not help liking Carnival and the hedonistic behaviour teacher Jones associated with it. It was behaviour that, according to him, their supposed Sint Maarten core pushed them towards.

For his own belonging, teacher Jones created an image of a Guyana that was flourishing. This was informed by his strong allegiance to the Seventh Day Adventist (SDA) church. The importance of the SDA faith showed in teacher Jones’ literal teaching of the Bible, his classroom rules and his judgement of certain events. For example, teacher Jones did not allow pupils to wear revealing clothes during dress-up day (and he would send pupils back home if he disagreed with their choices) and made them remove their ‘bling’: earrings, necklaces, and bracelets. He also refused to be present during sports day and to accompany the cycle 2 pupils (all pupils in grade 3 and up), on a trip to the cinema. These were not the type of celebrations his church approved of. He also strongly expressed his rejection of the Carnival music that was played at the school premises. After Carnival, he told me that the pupils talked about the school principal being in the Carnival parade. This was unacceptable to him because, ‘as educators we need to stay a few degrees above the rest!’Footnote17

From fieldwork experiences, I learned that many teachers, especially in public schools, were implicitly allowed to give a personal twist to the teachings they delivered, overt or covert. Much has been written about the hidden curriculum and the uncontrollable influences of teachers on the programme set by those in charge (e.g. Apple Citation1990; Cotton, Winter & Bailey Citation2013; Hosford Citation1980; Tekian Citation2009). There was little hidden about teacher Jones’ teachings, however. He openly mobilised discourses of belonging that contrasted with a positive Sint Maartenness. His Christian teachings aligned somewhat with the federal imagination of belonging, but the recent nationalist imaginary eschewed all teachings of Christianity.Footnote18 And teacher Jones was not alone. The high level of migration to and from the island had produced highly diverse pupil and teacher populations.Footnote19 Teachers from Jamaica, Haiti, Guyana, the Dominican Republic, and Trinidad (to name a few) complimented the already existing, diverse teaching corps consisting of teachers from the former Dutch Antilles (who were mostly trained in the Netherlands until the 1980s, after which they were trained at universities in the region instead), the Netherlands, Belgium (Flemish-speaking), and Surinam (where education is in Dutch). All these different teachers were trained elsewhere, in different traditions of pedagogy, and had their own discourses of belonging.Footnote20 Many of them, like Teacher Jones, drew on transnational ties to remake the discourse of national belonging.

The pupils’ remake of national belonging

One afternoon teacher Jones asked me to take over his class. Lulled into a slumber by the heat and the constant chatter of the pupils, I was a little hesitant. I had no lessons prepared. Was I willing and ready to stand in front of these pupils now? I did not have much time to think about it. The pupils were enthusiastically telling me to come up, ‘yes teacher Jodi, come on!’ and I realised I should take the opportunity. This would allow me to directly discuss (national) belonging with the pupils. I thus got up and asked the sixteen smiling faces in front of me if they remembered why I was in their classroom. They were hesitant, so I explained (again) that I was there to learn from them, and especially about the ways in which they thought and talked about the island on which we lived. I then asked them to tell me about Sint Maarten. At first, this caused some hesitation (what did I want to hear? Why should they explain things to me?), but they managed to name a few things. First ‘Soualiga’ (salt island) the original name for the island. They then told me that Sint Maarten had an airport and many restaurants and that there were statues. When I asked what type of statues, they mentioned the ‘Salt Pickers’ and the ‘Freedom Fighters’. One pupil, Saphira, did not agree with this, however, ‘The Freedom Fighters are from Haiti!’ she claimed.

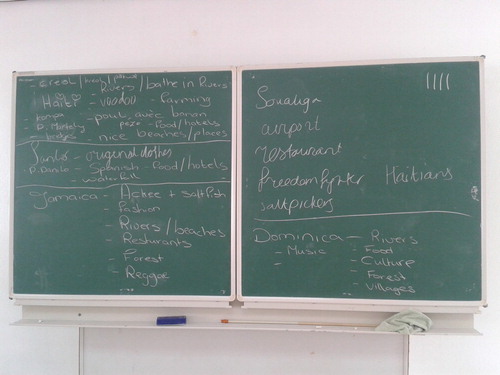

As soon as she mentioned Haiti, others started discussing other islands and came up with many things that I needed to write on the board. They talked about Haiti, Santo (the name used to refer to Dominican Republic), Jamaica and Dominica. Instead of mentioning the things one would find in a schoolbook (airport, restaurants, statues), they mentioned specific foods, clothes, beaches, and music and got into a lively discussion about what was best. Steven disagreed with everything and stated loudly that we were aliens, all aliens. I could no longer control or understand. Teacher Jones, who had been correcting homework in the back of the classroom, interfered on my behalf. As the pupils calmed down a little I asked them to write on the board what they thought was important (see ).

Questioning the ways in which pupils imagined Sint Maarten taught me (as did other moments in- and outside the classroom) that relations to other (imagined) places constituted their idea of ‘Sint Maarten’. These imaginations were based on their own and their families’ relations to other islands. These islands were places that their families talked about with pride. And even though many of them were grateful for the lives they were able to live on Sint Maarten, hardly anyone expressed explicit pride for the island, as those in charge of education, especially those who imagined an nationalist belonging to the island, would have liked them to do.

In response to my questions concerning national belonging, pupils thus remade the national by filling it with imaginations of places elsewhere, much like their teacher did. But for the pupils, these transnational ties also gained meaning in different ways. As they grew up together, as they played and fought, sang and danced, they learned to also do (national) belonging in ways that differed from the logic expressed by teacher Jones and the nationalist vanguard (which states that people from a certain nation speak, eat and dress a certain way, because of their national, individual essence). The pupils taught me that even though they could draw on transnational ties and are influenced by the (dis)likes of adults such as their parents, they also challenged its essentialist underpinnings and unmade the logic of it. I will now describe my interaction with several other pupils, to explain how such a challenge was performed.

Unmaking the logic of the nation

While we walked up the stairs after the lunchbreak Saphira told me, ‘tomorrow is Haitian day, I gonna stay home.’ I asked her what she would do then. The teacher who stood in the doorway joked, ‘Voodoo!’ to which Joel responded, ‘That’s racist!’ As we entered the classroom I asked Saphira, ‘What is Haitian day? What do you do tomorrow?’ ‘I don’t know’, she said. ‘So why you celebrate?’ I pushed further. She explained, ‘We just celebrating Haiti.’ Carlos, who heard us speak, interrupted: ‘Independence, teacher!’ he said, to which Saphira agreed. But she also expressed that to her, Haitian day was not necessarily about that. For her, it was about being Haitian for the day. She told me, ‘So tomorrow I am Haitian.’ This made me curious about the other days, so I asked, ‘And today you are a Sint Maartener?’ ‘Sure’, she responded and then added, ‘So if I act strange tomorrow you know why!’ ‘Haitians act weird?’ I asked. ‘Yes boy. You see how they fight!?’

Saphira could thus be a Sint Maartener one day and become Haitian the next. Being the one or the other was not related to a core self, but had to do with the day of the year. This differs from the ideas put forth by teacher Jones, according to whom one is Guyanese or Sint Maartener, Haitian or Jamaican. That common-sense logic was also shared in the social studies book the pupils learned from, and in the policies and practices of the people I met at the Sint Maarten department of education. This logic adheres to a nationally ordered world connected to cultural identities, language and also, as some argue, certain types of behaviours (see also Arrindell Citation2014). However, pupils do not necessarily share this apparently common-sense logic. For them, one can be Haitian one day, and become Sint Maartener the next. This belonging/identification is not related to a core identity, but to a certain type of performance that is associated with a specific stereotype; in this case, that Haitians fight. So, when one fights a lot, someone may become Haitian. And as the following vignette shows, one does not even need to have kinship ties to a place to be able to perform and become.

Daisy was sitting next to me on a bench at the playground and told me that she had learned a new word. ‘I hear it in a Jamaican movie.’ ‘Do you often watch Jamaican movies?’ I asked her. ‘Yes!’ She replied. ‘Is your family from Jamaica?’ I asked, ignorantly following a nationalist logic. ‘No, I am not Jamaican, but I do behave like one’, she said. ‘What does that mean?’ I questioned her. ‘You know!’ She answered, laughed and became silent. She didn’t tell me more as she assumed that it should have been clear to me now. I decided to ask her again though: ‘What does it mean to behave Jamaican?’ Daisy explained:

My father tell me to stop behaving like one, when I being bad. I shouldn’t behave like one cos I am not one. My parents are both from Haiti and they came to Sint Maarten to make me. That’s is why I can speak French.

Daisy clarified that one could behave in a certain way, for example, Jamaican, without having to ‘be’ one. Pupils could thus not only perform different national stereotypes next to one another, but they could perform belonging to an imagined ‘we’ that they had no ‘common sense’ kinship ties with. The logic of belonging promoted by these pupils was thus different from the national belonging expressed by their teacher, or the one promoted in their books. It is a temporary and shifting belonging based on performances of national stereotypes. As the vignettes show, these stereotypes were largely inspired by the comments of the adults in their lives, adults who had ties elsewhere. However, as Daisy explained, she was also influenced by the movies she watched. I learned quickly that songs, excerpts from videos and game characters also informed pupils’ performances that contested idea(l)s of any lasting ‘we’ based on a singular national identity.

Popular culture and Relation

The popular culture that I refer to here does not include only the cultural products that have become popular amongst the masses. I use the term also in the way Stuart Hall (Citation2006) did. Hall understood popular culture as the arena in which common sense power relations and related orders and hierarchies could be challenged (see also Storey Citation2009). Levinson and Holland (Citation1996) draw upon Hall’s work on popular culture to explain the process of the cultural production of the educated person. They claim that the classroom provides a place in which both reproductions and contestations take place. Understanding the classroom as such a site allows us to move away from the idea that pupils fail (to reproduce all kinds of lessons, including those related to the nation) because of puberty, laziness or because they are victims of bad educational systems. We then move to an understanding of the performances inside the classroom as valuable challenges to common orders taught. The different ethnographies on the cultural production of the educated person (in Levinson, Foley & Holland Citation1996), show that through contestation inside the classroom, other idea(l)s of the educated person arise. What would such an alternative educated person be in this classroom on Sint Maarten?

Teacher Jones was teaching a lesson about water refractions. He explained and drew on the board what refraction could look like. David responded ‘the water do Voodoo!’ which the teacher ignored. He continued explaining the shades of colour that emerge from water. But that tickled the imagination again. David mentioned Fifty Shades of Grey, the romantic erotic movie based on the book with the same title, which some found ‘stupid’ and others found ‘fresh’ and created a whole lot of tumult. As the teacher tried to bring the matter of science back in, the lesson spun out of control entirely. Teacher Jones talked about vision and hearing which caused a comment on ears, the ears of a dog, ticks, how to remove ticks, the love of dogs, or better, cats and so on. When teacher Jones encouraged the pupils to do their work they responded by performing the Barbadian popstar Rihanna’s song ‘work, work, work, work, work’.Footnote21 Everyday teacher Jones worked hard to return to the important topics of his lessons and his preferred setting (Guyana), striving for an order in which he taught and the pupils responded with the correct answers or sensible questions. But the pupils’ responses continually caused the lessons to spin out of the teacher’s control.

Both David and Daisy drew on knowledge of movies to contest the common order of the nation and that of human development based on sexuality. David talked about an erotic movie that is ‘not for his age’ and Daisy explained that she learned to speak and behave ‘Jamaican’ by watching movies that were made there. Other expressions that I encountered, and that challenged the classroom order were ‘My Name is Jeff’ and ‘Deez Nuts’. It took me a while to learn that these were echoes of popular ‘Vines Videos’. These videos are remakes of remakes of mixes of Hollywood, Bollywood and Nollywood movies, combined with songs and home videos shared on the internet, that have become an important way for marginalised youth to challenge existing stereotypes (Lu and Steele Citation2019). What I found interesting was that the practices of mixing, copying, and dubbing that are part of the creation of these videos are also commonly practiced in the music the pupils listened to. These songs entered the classroom when pupils spontaneously sang ‘What do you mean?’ or performed songs by the Jamaican reggae king Bob Marley, North American rapper and producer Chief Keef,Footnote22 or the Tolly Boys,Footnote23 local performers of Bouyon Footnote24 music. Pupils also played this music on their phones and sometimes, when the teacher was away and the Internet worked, on the school computer. With these transglobal performances, pupils contradicted the teacher’s norms and ethics. For example, when Emanuel sang the Tolly Boys’ most famous song, ‘Tolly [penis] she want, tolly she go and get’ while grinding against the doorpost, teacher Jones was not amused. He wanted decency. And a return to the underlying logic and order he understood.

I would like to argue that the mixing, dubbing, and repeating of sounds and practices from across the globe, which is the foundation of these songs and the Vines Videos, also infused the pupils’ becoming together within this classroom throughout the day. Pupils could perform (their parents’ or popular) national stereotypes while also at times, challenging the underlying orders. They performed racialised stereotypes, and also anti-racist commentary. They often included performances of specific sexualities, referred to Voodoo and pan-African identities, and made jokes about man-on-man sex while sharing homophobic anecdotes. To the pupils, no particular performance contradicted or excluded another but they often seemed to be grounded in contradiction.

Because none of the pupils’ performances were meant to last, they continuously un- and remade orders that did aim to do so. Not just the teacher’s, but also those of the school, the setting of a classroom with its specific power structures, the imagination of the elites in charge, and mine as a researcher. I would describe the pupils shared performance (which is not actually belonging) as grounded in opposition. However, if asked, the pupils would probably disagree with my analyses of their performances as continuously contradictory, and consciously so. My description of their belonging as contradictory would still be an aim at giving it a lasting ground. While I think that the reason the pupils’ performances challenged the lasting discourses of order was because the pupils’ ongoing creative ways of being in the world was in tune with Glissant’s Relation (Citation2010 [1990]). As ongoing creolisation, their becoming always moved and did not allow anything to remain outside, primary or unchanging.

Relation, as we have emphasized, does not act upon prime elements that are separable or reducible. If this were true, it would itself be reduced to some mechanics capable of being taken apart or reproduced. It does not precede itself in its action and presupposes no a priori. It is the boundless effort of the world: to become realized in its totality, that is, to evade rest. One does not first enter Relation, as one might enter a religion. (Glissant Citation2010 [1990], 172)

For Glissant, Relation is the always ongoing becoming of the world in all its connected imaginations, materialities and submarine intuitions. While I, like other social scientists, policy makers and educators take apart, describe, deconstruct and think outside of lived reality and outside of the ongoing flow of living, these pupils’ ongoing creative living will always defy any of the orders we make and imagine to last.

Producing national belonging through education?

The two different elite formations on Sint Maarten, much like the politicians and policymakers in the Netherlands I started this article with – as those in many places across the globe – share the dream of creating a national citizenry through primary education. Even though the specific national imaginations differ, the educational ideal of transmission remains. Nationally-inclined politicians in the Netherlands (whose number is steadily increasing), may argue that this process would be more feasible in schools in the Netherlands, not only because of lower levels of migration (especially of teachers), but also because of a more unified educational system and a clear national curriculum. However, I believe that in the Netherlands, like on Sint Maarten, the cultural production of the (national) educated person in primary schools is fraught with contradictions.

In The Cultural Production of the Educated Person: Critical Ethnographies of Schooling and Local Practices (1996) different authors show how contestations of pupils and teachers can produce other, sometimes more equal, shared understandings of the educated person. The performances that I encountered in the classroom did not, however, develop into a predictable, recognisable or shared imagination of the educated Sint Maartener. Instead, the plentitude of encounters that took place between pupils, teachers, teaching materials, songs, movies, videos, and idea(l)s in this classroom ensured continuous change.

As pupils performed their creative conviviality in considerable freedom, they demolished any construction of unity that existed as separate from ongoing Relation. In the Caribbean region, shaped by processes of migration and creolisation, this may be deemed ‘expected’. Yet as Glissant argues, the entire world is (part of) Relation. Constructions of (national) order and related imaginations of belonging remain more common in Europe. However, other imaginations of ‘we’, and other performances of conviviality are also shaping in urban areas across this continent and elsewhere (see also Gilroy Citation2004 and Guadeloupe Citation2009). Following Glissant, I propose that research with pupils in schools elsewhere will show similar performances grounded in Relation. Such research can only be successful when academics and policymakers unlearn preconceived orders and idea(l)s, so that we become able to experience the world anew. Not just once, but continuously.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Jordi Halfman http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4485-7375

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2017/08/16/les-over-wilhelmus-bij-nieuw-kabinet-a1570064 (last visited 13/09/18).

2 https://nos.nl/artikel/2195138-scholieren-verplicht-naar-rijksmuseum-en-tweede-kamer.html (last visited 13/09/18).

3 https://www.slo.nl/primair/themas/burgerschap/ (last visited on 06/12/2018).

4 From an interview conducted within the Oxford Diaspora Programme in April 2012: http://www.migration.ox.ac.uk/odp/pdfs/PatrickChamoiseauInterview_F.pdf (last visited 13/09/2018).

5 It is not part of the Netherlands or the E.U., and its dependence demands a rethinking of the meanings and interpretations of sovereignty (cf. Bonilla Citation2013).

6 These elite formations were not made explicit to me, but many people implicitly understand the differences between the nationalist independence vanguard and the federal elite.

7 I consider the new minister of Education, Culture, Youth and Sports in 2018 to be part of this elite.

8 I use the name St. Martin here, which refers to the entire island, north and south. I do so because this vanguard imagines a break with all colonial ties. The geographic and cultural unity could then become a political one as well.

9 This was possible because of the close ties between Dr. Arrindell and the political elite. Like everyone else on the island, the members of the vanguard were part of the capitalist system within which politics and business on the island were tightly interwoven.

10 Because of the intricate connection between politics and business and the enormous influence of pink-skinned families, the second in line were these locals. Only then came the people of African descend from the region.

11 Names of all my interlocutors have been altered, accept for those who were well-known because of their political positions during the time I conducted my research.

12 Because public schools were cheap and admission was straightforward, they were accessible and attended by pupils from less wealthy families.

13 The population of Sint Maarten grew from 1581 inhabitants in 1951, to 41900 in 2018, http://countrymeters.info/en/Sint_Maarten (last visited 04/05/2018). The places people left to come to Sint Maarten are, (from largest to smallest share) the Dutch Kingdom, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Guyana, the UK, the US, India, Suriname, Colombia, China and Venezuela (in Guadeloupe Citation2009, 12).

14 Until 2010 Sint Maarten’s immigration laws were dictated by the Kingdom. Recent investigations and lawsuits imply that borders are porous. People on the island, including many politicians, have dealt with border control and migration in rather pragmatic ways. Even though different local governments have promised stricter border control (something the Netherlands is also keen on implementing and monitoring) capitalist needs for cheap labour have thus far overruled the need for stricter law enforcement. See for example: http://www.sintmaartengov.org/PressReleases/Pages/Strict-Enforcement-of-the-Law-for-Visitors-and-Residents.aspx and https://smn-news.com/st-maarten-st-martin-news/22232-exclusive-director-of-immigration-under-investigation-for-smuggling-illegal-into-st-maarten.html (last visited 17/09/2018).

15 Teacher Jones had a hard time teaching these youngsters who lived in a very different reality then he did. He honestly cared for them but also wanted them to behave in ways that he understood, condoned and could, in some way, control.

16 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DK_0jXPuIr0 (last visited 26/04/2018).

17 In these words I discern traces of teacher Jones’s own upbringing and education in the British West Indies, where class hierarchies mattered.

18 In my dissertation “Where Randy?” Education, Nationalism, and Playful Imaginations of Belonging on Sint Maarten I show how Sint Maartenness is related to and contested by a variety of Christian teachings.

19 According to the report ‘The State of Education’ 2012–2014 (obtained through University of St. Martin in 2015), 69% of teachers had the Dutch nationality at that time, whereas 31% had a foreign passport.

20 The instructors at the University of St. Martin (USM) never adhered to the idea(l) of delivering teachers that instilled deep national values either. Most of their students came from elsewhere and management was critical of overtly nationalist imaginations of national belonging.

21 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HL1UzIK-flA (last visited 01/08/2018).

22 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YWyHZNBz6FE (last visited 01/08/2018).

23 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vyNK-_tamdQ (last visited 01/08/2018).

24 Bouyon implies mixing and here refers to a music style that originated in Dominica and has become popular amongst youth in the Caribbean.

References

- Anderson, B. R. O. 2003[1983]. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Antonsich, M. 2010. “Searching for Belonging – An Analytical Framework.” Geography Compass 4 (6): 644–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00317.x

- Apple, M. W. 1990. Ideology & Curriculum. New York: Routledge.

- Arrindell, R. 2014. Language, Culture, and Identity in St. Martin. Philipsburg: House of Nehesi Publishers.

- Benoît, C. 2008. “Saint Martin’s Change of Political Status: Inscribing Borders and Immigration Laws onto Geographical Space.” NWIG: New West Indian Guide/Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 82 (3/4): 211–235.

- Besson, J. F., and Olwig, K., eds. 2005. Caribbean Narratives of Belonging: Fields of Relations, Sites of Identity. London: Macmillan Caribbean.

- Bonilla, Y. 2013. “Nonsovereign Futures? French Caribbean Politics in the Wake of Disenchantment.” In Caribbean Sovereignty, Development and Democracy in an Age of Globalization, edited by L. Lewis, 208–227. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Chamoiseau, P. 2018. Migrant Brothers: A Poet’s Declaration of Human Dignity. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Collins, J. 2009. “Social Reproduction in Classrooms and Schools.” Annual Review of Anthropology 38: 33–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.37.081407.085242

- Cotton, D., J. Winter, and I. Bailey. 2013. “Researching the Hidden Curriculum: Intentional and Unintended Messages.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 37 (2): 192–203. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2012.733684

- Dewey, J. 2009 [1916]. Democracy and Education. Merchant Books: Unknown.

- Feld, S. 2012. Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra: Five Musical Years in Ghana. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Freire, P. 1996[1970]. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin.

- Geschiere, P. 2009. The Perils of Belonging: Autochthony, Citizenship, and Exclusion in Africa and Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Gilroy, P. 2002. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Verso.

- Gilroy, P. 2004. After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture? London: Routledge.

- Glissant, E. 2008. “Creolization in the Making of the Americas.” Caribbean Quarterly 54 (1/2): 81–89. doi: 10.1080/00086495.2008.11672337

- Glissant, E. 2010 [1990]. Poetics of Relation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Guadeloupe, F. 2009. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hall, S. 2006. “What is This ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?” In Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, 479–489. London: Routledge.

- Harris, W. E. 2008. “History, Fable and Myth in the Caribbean and Guianas.” Caribbean Quarterly 54 (1/2): 5–38. doi: 10.1080/00086495.2008.11672333

- Hedetoft, U., and M. Hjort, eds. 2002. The Postnational Self: Belonging and Identity (Vol. 10). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hosford, P. L. 1980. “Improving the Silent Curriculum.” Theory Into Practice 19 (1): 45–50. doi: 10.1080/00405848009542871

- James, C. L. R. 1989 [1938]. The Black Jacobins; Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. New York: Vintage.

- Lamming, G. 2009. Sovereignty of the Imagination: Conversations III. Philipsburg: House of Nehesi Publishers.

- Levinson, B. A. 1996. “Social Difference and Schooled Identity in a Mexican Secundaria.” In The Cultural Production of the Educated Person: Critical Ethnographies of Schooling and Local Practice, 211–238. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Levinson, B. A., D. E. Foley, and D. C. Holland, eds. 1996. The Cultural Production of the Educated Person. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Levinson, B. A., and D. C. Holland. 1996. “The Cultural Production of the Educated Person: An Introduction.” In The Cultural Production of the Educated Person: Critical Ethnographies of Schooling and Local Practice, 1–54. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Lu, J. H., and C. K. Steele. 2019. “‘Joy is Resistance’: Cross-Platform Resilience and (re)Invention of Black Oral Culture Online.” Information, Communication & Society 22 (6): 823–837. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2019.1575449

- Olwig, K. F. 2007. Caribbean Journeys: An Ethnography of Migration and Home in Three Family Networks. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Roitman, J. V., and W. Veenendaal. 2016. “‘We Take Care of Our Own’: The Origins of Oligarchic Politics in St. Maarten.” European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies/Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe 102: 69–88. doi: 10.18352/erlacs.10119

- Schiffauer, W., G. Baumann, R. Kastoryano, and S. Vertovec, eds. 2004. Civil Enculturation: Nation-State, Schools and Ethnic Difference in Four European Countries. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Skinner, D., and D. C. Holland. 1996. “Schools and the Cultural Production of the Educated Person in a Nepalese Hill Community.” In The Cultural Production of the Educated Person: Critical Ethnographies of Schooling and Local Practice, 273–300. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Storey, J. 2009. Cultural Theory and Popular Culture: An Introduction. Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Suárez-Orozco, M. M., T. Darbes, S. I. Dias, and M. Sutin. 2011. “Migrations and Schooling.” Annual Review of Anthropology 40 (1): 311–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-111009-115928

- Sullivan, A. 2002. “Bourdieu and Education: How Useful is Bourdieu’s Theory for Researchers?” Netherlands Journal of Social Sciences 38 (2): 144–166.

- Tekian, A. 2009. “Must the Hidden Curriculum be the ‘Black Box’ for Unspoken Truth?” Medical Education 43: 822–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03443.x

- Trouillot, M. R. 1992. “The Caribbean Region: An Open Frontier in Anthropological Theory.” Annual Review of Anthropology 21 (1): 19–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.an.21.100192.000315

- Trouillot, M. R. 2002. “North Atlantic Universals: Analytical Fictions, 1492–1945.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 101 (4): 839–858. doi: 10.1215/00382876-101-4-839

- Walcott, D. 1974. “The Caribbean: Culture or Mimicry?” Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 16 (1): 3. doi: 10.2307/174997

- Walcott, D. 1998. What the Twilight Says. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Yon, D. A. 2003. “Highlights and Overview of the History of Educational Ethnography.” Annual Review of Anthropology 32 (1): 411–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.061002.093449

- Youkhana, E. 2015. “A Conceptual Shift in Studies of Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” Social Inclusion 3 (4): 10–24. doi: 10.17645/si.v3i4.150

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2006. “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” Patterns of Prejudice 40 (3): 197–214. doi: 10.1080/00313220600769331