ABSTRACT

In this paper, I develop the idea of cosmopolitan stances – one ‘intellectual’ and the other ‘aesthetic’ – to examine conceptions of cosmopolitanism within a range of university strategies. Recent research into cosmopolitanism has adopted a Bourdieusian lens, understanding it as cultural capital, which acts as a locus of stratification in the global system. By examining the strategies in 11 London-based universities, this paper sought to identify which cosmopolitan stances are mobilised. Following a thematic analysis this paper argues that those stances privileged by the global middle class are often implicit and generated incidentally as a function of other initiatives such as inclusivity and diversity, global citizenship, placement opportunities and graduate attributes/outcomes.

Introduction

In a globalised world where students are free to pursue study overseas there has been rapid growth in competition between the global middle class (GMC) for educational experiences that confer social and cultural capital (Bourdieu Citation1990, Citation1999) and secure access to elite employment opportunities. In the contemporary era of globalisation, cosmopolitanism has been recognised as a form of cultural capital and a social practice that can be reproduced through international student mobility (ISM) and is valued in elite careers (Igarashi and Saito Citation2014; Nicolopoulou et al. Citation2016; Piwoni Citation2020). Cosmopolitanism is in its broadest sense conceptualised in this paper as an openness to the foreign and others (Beck Citation2006).

This paper was inspired by the 2012 commentary on the future of elite research in education by the sociologist Stephen Ball. He noted that education was ‘not good at remembering elites’ and instead tended to focus its gaze on social disadvantage. In the same commentary Ball outlines how the geographies of elites have changed, they now cluster in global cities, their nature now defined by disidentification with the national and an embrace of ‘transnational practices’ (Ball Citation2016, 71). Entry into the elite is no longer based on skills, but rather the ability to sell one’s self, the notion of ‘fit’ and the accumulation of social and cultural capital (Bourdieu Citation1990, Citation1999) which are essential components to gaining positional advantage (Brown et al. Citation2016; Friedman and Laurison Citation2019). In this paper, I follow Bailey (Citation2001) and Vertovec (Citation2002) definitions of ‘elites’, sometimes termed ‘capital class’ (Thrift Citation2005) or ‘Transnational Elites’ (Beaverstock Citation2005), conceiving them as those actors most regularly situated within global cities who are hyper mobile, highly paid and embedded in transnational networks. The term elite was chosen instead of ‘highly skilled’ in order to not pass judgement on what count as a skill. In addition, the term was chosen to align with literature in the field of economic geography and sociology.

Recent research into cosmopolitanism and education has unpacked how the GMC have developed strategies to accumulate cosmopolitan capital through their choice of international schools, choice of curriculum (e.g. International Baccalaureate [IB] programmes) and choice to engage in ISM as part of their university education (Wright, Ma, and Auld Citation2021; Maxwell and Yemini Citation2019; Yemini and Maxwell Citation2018; Yemini, Tibbitts, and Goren Citation2018). This research project has sought to build on this work by exploring the role of university education in the reproduction of cosmopolitanism for the GMC. In particular, the research aims to build on the analogous contributions of Su and Wood (Citation2017a, Citation2017b) which sketched out how academic leadership and institutions can ‘nurture’ cosmopolitanism through social learning, critical reflection and pedagogic approaches.

Located at the intersection of economic geographies, international student mobilities and the larger body of sociology of education, this investigation sought to understand how cosmopolitanism is conceptualised within university strategies. In doing so it hopes to better understand how cosmopolitan capital and social practices are both produced and reproduced. The theoretical approach was guided by Bernstein’s (Citation2000) concept of the ‘pedagogic device’. The pedagogic device is explained by Bernstein as a collective set of rules or procedures through which knowledge is converted into pedagogic discourse which in turn shapes the conditions for, and types of, curricula and teaching experiences and outcomes. The concept coloured in what Bernstein perceived to be the opaqueness of educational transmission, where the putative inputs and outputs were known but the underpinning socialisation had become trivialised and lacked investigation. Although a relatively new approach for the field of economic geography, Bernstein’s work has been adopted by similar research projects in the sociology of education aimed at identifying the complexities and contestations in shaping university curricula and pedagogy.

I begin this paper by exploring the differing conceptions of cosmopolitanism and propose two broad stances ‘Intellectual’ and ‘Aesthetic’ which I apply to my analysis. Next, cosmopolitanism is operationalised through Bourdieu’s theories of capital and habitus by reviewing relevant literature on the GMC and transnational elite. Then, by adopting a Bernsteinian paradigm I analyse university strategies to uncover the cosmopolitanism stances that are privileged and inform the institutional conditions, educational vision and approaches to pedagogy.

Conceptions of cosmopolitanism

Cosmopolitanism is a concept with a chequered history over recent decades, with occasional resurgences to address new areas of social inquiry. The term itself has a long history being traced back to Cynics of the fourth-century BC (Appiah Citation2007, xii, cited in Su and Wood Citation2017a) who defined ‘cosmopolitanism’ as a ‘citizen of the cosmos’, a conception to which Nussbuam (Citation1994) referred to as ‘the person whose allegiance is to the world-wide community of human being’. Over its long history the term and its meanings has been subject to constant revision especially in the face of the recent decades of globalisation. Broadly the accepted definition of cosmopolitanism now rests on notions of openness to foreign and other(s) cultures (Beck Citation2006; Beck and Sznaider Citation2006; Delanty Citation2006; Szerszynski and Urry Citation2006).

Within political philosophy a recent paper by De Wilde et al. (Citation2019, 15) argues that supernational cosmopolitanism is in a struggle for power with liberal nationalism and communitarianism, driven by new opportunities and threats that have arisen from globalisation. It could be argued that this conflict burst into the mainstream in recent years, memorably articulated in the speech delivery by then Prime Minster Theresa May in 2016.

Today, too many people in positions of power behave as though they have more in common with international elites than with the people down the road, the people they employ, the people they pass on the street … but if you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere. You don’t understand what citizenship means.

Such sentiments are not just found in the UK, but also across the Atlantic. During a White House daily press briefing in 2017 Stephen Miller accused a CNN reporter of ‘cosmopolitan bias’ when discussing the future of US immigration policy (Bloomberg Citation2017). These political moments illustrate the larger tensions between globalisation and new forms of supernational governance, alongside more tangible national questions of what it means to be a citizen. Indeed, theories of cosmopolitanism are not just limited to the political domain, with Maxwell et al. (Citation2020) recently proposing the idea of ‘cosmopolitan nationalism’ in the British Journal of Sociology of Education to better explore the contested ground of the national and international in education.

The cosmopolitanism of transnational capitalism that is most often tied to elites concerns itself with globalisation and visibility of multiculturalism within global cities. This cosmopolitanism celebrates the vibrancy of other cultures and the feeling of familiarity with strangeness, prizing the ability to act in foreign spaces (Beaverstock Citation2005, Citation2018; Vertovec Citation2002; Thrift Citation2005; Sassen Citation2016). The cosmopolitans themselves embodying not only an openness to foreign and other cultures but also the competencies and practices to partake in cosmopolitan life. Importantly this conception should not be conflated with those individuals of what can be called ‘ordinary’, ‘banal’ or ‘consumerist’ cosmopolitanism discussed elsewhere, that primarily concern themselves with the consumption of global brands, tourism and multicultural food (Beck Citation2001; Calhoun Citation2002; Su and Wood Citation2017a; Szerszynski and Urry Citation2006).

In education conceptions of cosmopolitanism are often synonymous with virtuous and moral ideas, global learning and Kantian inspired goals of global citizenship (Davies and Graham Citation2009). Over recent years this conception of cosmopolitanism has found form in Global Citizenship Education (GCE) which has been added to curriculums across a number of countries see Pak and Lee (Citation2018) for South Korea, O'Connor and Faas (Citation2012) for England, France and Ireland, Rapoport (Citation2010) for the US and Schweisfurth (Citation2006) for Canada. Some forms of GCE and related cosmopolitanism draw from ideas of global-mindedness, global consciousness and world citizenship, aiming to towards each citizen learning to become a ‘cosmopolitan citizen’ where political authority is disconnected from the nation state and is diffused ‘above’ and ‘below’ (Oxley and Morris Citation2013). Another highly visible form is the IB which is finding a home in public schools in the national education systems of the US, Korea and Japan (Maxwell et al. Citation2020). In universities, ideas of ‘new cosmopolitanism’ or ‘critical cosmopolitanism’ have developed, challenging conventional conceptions which they consider to be driven by global capitalism and Euro-American elitist ideologies (Werbner Citation2020). Such conceptions place themselves in opposition to what they term the Western, neo-liberal, neo-mercantilist, position on education and the promotion of internationalist, or liberal-aesthetic goals. Instead, they aim to promote a critical competence and active citizenship that cares fundamentally about a universality, morality and political engagement (Baildon and Alviar-Martin Citation2020; Stornaiuolo and Philip Citation2021).

Mobilising cosmopolitanism

In a globalised world where until recently (Covid-19) students were free to pursue ISM there has been rapid growth in the competition for academic qualifications and educational experiences that could not have been gained at a home university. Academic qualification(s) have long since been recognised as one of the key forms of social-cultural capital, referred to as the ‘competition for academic recognition’ (Bourdieu Citation1999; Hall and Appleyard Citation2009; Hall Citation2017; Waters Citation2018). In this competition, education signals not just an individual’s worth, but also intangibles such as embodied skills, knowledge, capabilities and attitudes to employers.

From a Bourdieusian perspective, cosmopolitanism can be conceived of both as an institutionalised form of ‘cultural capital’ (e.g. academic qualification) and as an embodied state of one’s ‘habitus’ shaping social practice (e.g. embodied skills, knowledge, capabilities). The habitus reflects the social position of an individual, and it is shaped the social condition of the field ‘reflecting perceptions, appreciations and practices’ (Bourdieu Citation1990, 53). The habitus is neither fixed nor entirely fluid; rather it evolves as individuals move through social spaces, adapting to understand and embody new practices (Maton Citation2012).

It is reflected in individuals’ values, speech, dress, conduct, and manners that shape their everyday life. Habitus enables individuals to display the right behaviour and practices (e.g., at job interviews) without a conscious attempt to do so, thus ‘acting intentionally without intention’. (Joy, Game, and Toshniwal Citation2020, 2545)

Recent studies have uncovered how the cosmopolitan capital and social practices gained from higher education, are helpful in securing jobs in globalised industries (Igarashi and Saito Citation2014; Nicolopoulou et al. Citation2016; Ye and Kelly Citation2011). Notably, work by Waters (Citation2009), Kim (Citation2011, Citation2012) and Hao and Welch (Citation2012) have demonstrated the profits that qualifications attained abroad can afford individuals in the specific labour markets such as Hong Kong, Beijing and South Korea. The value of cosmopolitanism is set by the demand from transnational employers and global firms based within the regions who seek employees who can navigate global markets. The mobilisation and profitability of a particular kind of cosmopolitanism thus becomes intertwined with the agency of the expatriate worker, the transnational professional and the diversity of the global city without whom the need for cosmopolitanism would hold little value or applicability as a social practice (Yeoh and Huang Citation2011).

Here it is important that we discuss and understand how theories of globalisation and world city networks can set the returns of cosmopolitanism for an individual. Over the past several decades a theory of globalisation has been constructed which attempts to understand how global and national economies interact with one another, a central piece of this body of work has been the theory of a new social form, ‘the network society’ (Castells Citation2000). This theory reasons that globalisation can be understood not just through the flow of money but also through the flow of information and people, through newly constructed transnational networks, ‘pipelines’, that link nations together (Bathelt, Malmberg, and Maskell Citation2004).

Negotiating these ‘pipelines’ are elite employees, conceptualised as ‘flows’, bring not just tacit skills, but also cosmopolitan networks, cultural practices and social relations, (Beaverstock Citation2002, 525). These professionals are often educated overseas and have key social relationships with ‘Western educated/experienced … work colleagues, clients and competitors’ (Beaverstock Citation2002, 537; Meyer Citation2015) and are fluent in multiple languages and assert experience of multiple cultures (Hannerz Citation1996). Research by Beaverstock (Citation2005, Citation2018) suggests that these transnational elites are prized for their confidence and competency to act in foreign environments, alongside their ability to effective social network, meet new people and share ideas in order to generate formal meetings and business opportunities.

These individuals not only embody an air of cosmopolitanism, but also, in the course of their ‘life-world’, reproduce practices of cosmopolitanism through time and space, which helps to foster a ‘cosmopolitan’ sense of place, (Smith Citation1999; Waters Citation2007). Thus, in the most diverse and connected labour markets of global cities () an individual’s lack of cosmopolitanism can become a barrier, a new form of exclusion coded into the labour market.

Table 1. Major world cities by percentage foreign born (Migration Policy Institute Citation2016; Office for National Statistics Citation2018; World Bank Citation2019; Shanghai Basic Fact Citation2020; Dubai Statistics Center Citation2019; Tokyo Metropolitan Government Citation2015; Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2016; Statistics Canada Citation2016; US Census Citation2019).

By reviewing how cosmopolitanism is mobilised by elite actors we can see a tension between conceptions of cosmopolitanism. Those concerning themselves with high minded intellectual ideas of global worldliness and critical reflection, and those concerned with competencies and practices. This tension is something that was highlighted in Kim’s (Citation2011) paper on global cultural capital which looked at why Korean students studied abroad in the USA.

Their (Korean student) cosmopolitanism is aimed not toward equal partnership and common global good, but toward opportunities of becoming global elites. (120)

It is in view of the above that this research project aimed to address three research question: which conceptions of cosmopolitanism are embedded into university strategies?, what cosmopolitan conceptions, if any, are privileged above others? and what is the potential value of those conceptions to the GMC who aspire to elite careers?

Materials and methods

University strategy documents were chosen as the primary sources of data. University strategy documents provide rich sources of information as they act as public and internal messages of intent. They set out a university’s priorities, challenges, vision and to inform policy over a longer period of time. From a Bernsteinian (Citation2000) perspective the strategies function as a ‘pedagogic device’ regulating pedagogic discourse and providing a structural undergird to guide other university policies, degree programmes and modules of study. The methodological approach implemented was inspired by similar research projects into the sociology of education which analysed curricula, see Ashwin, Abbass, and McLean (Citation2012), McLean, Abbas, and Ashwin (Citation2013) and Lim and Apple (Citation2018).

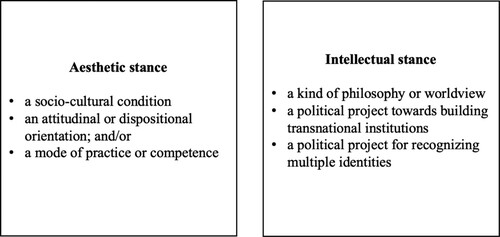

In order to illuminate different conceptions of cosmopolitanism within the university strategies I employed the six main conceptions of cosmopolitanism developed by Vertovec and Cohen, (Citation2002, 9); (a) socio-cultural condition; (b) a kind of philosophy or worldview; (c) a political project towards building transnational institutions; (d) a political project for recognising multiple identities; (e) an attitudinal or dispositional orientation and (f) a mode of practice or competence. These were then represented as two broad stances – that of ‘Intellectual’ and ‘Aesthetic’ (Esthetic) recognised in Hannerz (Citation1990, 39, Citation1996, 178) and Urry (Citation1995) ().

Figure 1. Author. Adapted from Vertovec and Cohen (Citation2002, 9) and (Hannerz Citation1996, 178).

The ‘Intellectual’ stance concerns itself with the conceptions of a philosophy or worldview, a political project towards building transnational institutions and recognising multiple identities. It grounds itself in notions of global or world citizenship and the aspirations of transnational political structures (Beck Citation1998). The ‘Aesthetic’ stance roots itself in Hannerz’ (Citation1990, 239) definition, as ‘a state of readiness, a personal ability to make one’s way into other cultures, through listening, looking, intuiting and reflecting’. ‘Aesthetic’ cosmopolitanism thus concerns itself with the liberal goals of education and the ‘privileged mobile elite’ (cited in Birk Citation2011, 8). Hannerz reasons that forms of ‘genuine cosmopolitanism’ can be both a competence and an ideology, both aesthetic and intellectual; ‘in other words, cosmopolitanism has two faces. Putting things perhaps a little too simply, one is more cultural, the other more political’ (Hannerz Citation2006, 9).

To investigate which stance of cosmopolitanism (intellectual or aesthetic) is embedded within strategy documents a thematic analysis was undertaken using NVivo. The two stances of cosmopolitanism, were coded as parent Nodes with different conceptions adopting child-nodes coded to Vertovec’s (Citation2002) six conceptions of cosmopolitanism: theses nodes were then used to interrogate each policy document with passages and sentences being coded to the relevant themes.

Setting

London in the United Kingdom was chosen as the site of the study due to its perceived ability to ‘confer … the mantle of a cosmopolitan identity’ (Tindal et al. Citation2015, 97). London was also selected due to the importance of international students to its economy, its positionality as a global city and the developing theme of ‘cosmopolitan nationalism’ (Maxwell et al. Citation2020) that through Global Britain has found its way into higher education.

As of 2019, London was home to 38 higher education institutions ranging from the federal University of London with an enrolment of some 120,000 students to the London Business School with much smaller enrolments focused on postgraduates studying MBAs (). As an ‘education city’, also termed ‘education hubs’ (Knight Citation2018), London also hosts to a range of foreign institutions such as New York University and the University of Notre Dame which are used to support study abroad exchanges.

Figure 2. Map of Major Universities in London. (Map data ©2020 Google.) (1. London School of Economics and Political Science; 2. University College London; 3. King's College London; 4. University of Westminster; 5. Goldsmiths, University of London; 6. University of Greenwich; 7. Imperial College London; 8. University of London; 9. Queen Mary University of London; 10. London South Bank University; 11. SOAS University of London; 12. University of West London; 13. City, University of London; 14. University of East London; 15. University of Roehampton London; 16. Kingston University; 17. London Business School. 18. Birkbeck, University of London; 19. London Metropolitan University; 20. Middlesex University London; 21. Royal Holloway; 22. St George's University of London; 23. St Mary's University Twickenham London; 24. University of the Arts London; 25 Brunel University London.)

The UK was the second largest recipent of international students in 2019 () and has one of the densest concentrations of overseas students of any OECD higher education system at 20% of the student cohort in 2018–2019 vs. an average of around 6% in other countries (OECD Citation2019). The UK, for its part, derives some £7bn in fees from these international students that it uses to cross-subsidise other subjects and research efforts (Johnson, Lynch, and Gillespie Citation2020). The total economic value of these students to the wider economy is valued at some £22.6 billion in 2015/2016, £5.1bn is generated by EU students and the remaining £17.5bn is generated by non-EU students. A typical EU-domiciled student is valued at approximately £87,000, and a non-EU student standing at approximately £102,000 (HEPI Citation2018). How the UK handles the Covid-19 pandemic and Brexit are of central importance to the future of the UK as an educational destination and for the wider economy. Indeed, the UK government has already taken steps to support the sector by allowing EU students to retain preferential access beyond the UK’s departure from the bloc (Gov.UK Citation2020). Universities themselves even took the unprecedented step of chartering flights to bring in international students in response to Covid-19 restrictions (BBC Citation2020).

Table 2. International students by country of destination and origin (Project Atlas, Institute of International Education Citation2020).

The language of Global Britain has found its way into the UK higher education since its exit from the European Union. The quasi-cosmopolitan-nationalist idea of a Global Britain, ‘open, outward looking and confident on the world stage’ has been touted as a post-European image for the UK, despite remaining somewhat ill-defined since its inception. The motif has been used repeatedly to brand a broad range of policies, from the UK retaking its seat at the World Trade organisation, the return to an ‘East of Suez’ military presence, the idea of a D10 of democracies as a replacement for the G7 and now higher education (Boussebaa Citation2020; FCO Citation2019; The Times Citation2020; Kenny and Pearce Citation2019). The editor of Times Higher Education penned an article in 2016 on how UK universities are among the ‘leading flag-bearers for Global Britain’. Similar language was also employed by the Vice-chancellor of the University of Reading who declared that his institution was ‘proud to fly the flag for UK higher education overseas – taking the best of our home institutions to the world’ and a June 2020 report titled ‘Universities open to the world. How to put the bounce back in Global Britain’, which was co-authored by Jo Johnson, former UK government minister (Bell Citation2017). The most recent report from the Department for Education titled International Education Strategy: global potential, global growth published in March 2019 echoed several cosmopolitan-nationalist tenants under the umbrella of Global Britain.

We know domestic and international students value the international classroom experience they get in UK institutions, the diversity of their cohorts and the global networks available to them after graduation. We also value this diversity and will look to ensure that the UK always has students coming from around the globe and recruitment follows sustainable patterns. We will continue to provide and will promote a competitive, welcoming offer for international students by seeking opportunities, both in the UK and overseas, to promote study in the UK and the UK’s strong enthusiasm to host international students. (Gov.UK Citation2019)

Situating stances of cosmopolitanism in London institutions

The research was undertaken between February 2020 and March 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic with its associated travel restrictions. A total of 11 strategy documents were collected and analysed drawn from London-based institutions (). Strategies were downloaded from publicly accessible sites, in most cases the university’s website themselves. Data were collected from a total of N = 7 universities, a majority (N = 4) are considered to be prestigious or selective institutions forming part of the Russell group of 24 research-based institutions; 1 college of a federal university system and 2 new university ‘post-1992’. All 7 universities were placed within the top 100 universities in the UK (The Complete University Guide Citation2020), with 3 placing within the top 100 universities worldwide (QS Citation2020). Additional data on the composition of London-based universities were collected from the Higher Education Statistics Authority (HESA Citation2020).

Table 3. Types of strategy documents collected and analysed.

Each strategy followed a similar structure, with each providing an introduction and foreword before setting out the institution’s priorities and objectives in varying levels of detail relating to the strategies’ focus, e.g. education, teaching and learning, institution and employment. The detail provided within each strategy varied significantly, with the theme of the strategy and priorities each institution set out. In total 10 strategies were collected and analysed, divided into three strategies, Educational, Teaching and Learning and Other – which mostly comprised of employment strategies.

In the education strategies of the two Russell group universities specific mention is made of how they leverage their location within London to support students into global careers and to develop networking opportunities. University 1’s strategy in particular made reference to London as a ‘living classroom’ which provided for formal and informal learning opportunities that can enable students to develop those skills needed for future careers. For example:

The formal and informal learning opportunities that our London and international partnerships provide enable our students to develop skills and networks that will support them in their future careers. (University 3, Education Strategy 2017)

We recognise that our students make the decision to study at … with one eye on their future careers. Our London location and our reputation as a world-class university, together with the huge network of industry and business partners we have, puts us in an ideal position to respond to overwhelming feedback from students that they expect their time at university to prepare them thoroughly for the world of work. (University 2, Education Strategy 2015)

Discussion of the universities’ positionality within and the utility of English speaking was limited to academic writing programmes and offers of support, with no mention of English as the cosmopolitan language or its utility for employment.

We will have expanded our academic writing programmes (and, where appropriate, our support for students with English as an additional language) so that all students, at any phase of their education, receive personalised support with this core skill. (University 2, Education Strategy 2015)

In Hong Kong, exposure to and knowledge of English alone was assumed by many companies to certify an individual for a position, with many overseas graduates receiving job offers even before graduation from Euro-American countries (Waters Citation2007). Other research by Kim (Citation2011) on Korean students studying in the USA discussed how in order to personify cosmopolitanism, one must be ‘armed with English communication’ (109). Early work by McDowell (Citation1997, 131) into culture of work in finance stressed that the ability to speak English provided for the right kind of ‘fit’ in globalised industries, becoming as necessary as wearing a business suit. Ye and Kelly (Citation2011) suggested how the ability to speak English must be complimented by an understanding of the appropriate cadences, accents and colloquialisms. Evidence suggests that it is not simply the ability to speak English that is valued within elite employment, but also the cultural understanding of the language and knowledge of vocabulary. Tannen (Citation1994) unpicked how metaphors and idioms such as ‘the balls in your court, stick to your guns, a level playing field and a curve ball’, play an important role within the everyday working vocabulary, proposing that knowledge of such vocabulary helps the individual achieve their position. This demonstrates how overseas education can not only act as symbolic capital signalling English language ability, but also how the nuances of the English language are formed in the habitus as a social practice (Bourdieu and Loïc Citation2013). Overseas educational experiences act to contextualise the language within the authentic culture and social environments of English-speaking universities.

A key cosmopolitan narrative within the strategies was the role the university plays on the global stage in supporting and delivering change. There is a real sense that each university wants to undertake social good at a global level and to address the global challenges of the twenty-first century such a climate change, cultural understanding, human well-being, global health (women’s health and mental health in particular) and justice and equality. This objective was usually made clear in the first few pages of the strategies’ introduction or foreword.

We will make the world a better place through enquiry-driven, disciplinary research that not only is high-quality and high-impact but increasingly enables multi and interdisciplinary collaborations which can be readily turned into insights and new solutions for the many and diverse challenges faced around the country and across the globe. (University 3, Education Strategy 2017)

We will foster a culture that understands and embodies the values of diversity and inclusivity, ensuring this is reflected in campus life, in the curriculum, and in the application of knowledge to real-life problems in a global context. (University 5, Teaching and Learning Strategy 2017)

This conception of cosmopolitanism places itself firmly within the intellectual stance with its roots within the philosophy or worldview which acknowledges one’s obligations to communities both local and global (Nussbaum Citation1994). In these statements, the strategies make clear the extent of their commitment to and feeling of responsibility to the other and their willingness to act politically as a transnational actor. These findings echo Wright, Ma, and Auld (Citation2021) recent work which reported how international schools’ curriculums covered global issues such as climate change and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Inclusivity and diversity

Alongside this, the strategies’ also make clear another key theme that holds cosmopolitan intent, that of inclusivity and diversity.

An increasing global inter-connectedness also means that our students must be able to understand diversity of ideas, languages, people and cultures to be successful. (University 3, Education Strategy 2017)

Igarashi and Saito (Citation2014) suggested that the social arenas of universities in countries such as the UK and USA, require extensive interactions with people of multiple nationalities and thus provide a forum for cosmopolitanism to manifest (). Indeed, in recent years London has seen a huge growth as a destination for international students with numbers reaching 125,035 in the year 2018/2019 (HESA Citation2019). University 3 has a higher percentage of fulltime international undergraduates than UK-born students, with other institutions following closely behind.

Table 4. Top 10 London institutions by non-UK enrolment (HESA Citation2019).

The inclusion of a diverse array of perspectives, cultures and practices is something which permeates western contemporary higher education. Education that values exposure to and the borrowing of other cultural practices can foster genuine changes in attitudes and practice. This aligns strongly with aesthetic stance of cosmopolitanism; that of ‘an attitudinal or dispositional orientation’ and ‘a mode of practice or competence’. Additionally, one strategy defined the aim of exposing their students to multicultural, international teams in order to cultivate a global and interdisciplinary fluency. Indeed, the very nature of contemporary Euro-American societies ‘highly tolerant, open, accepting of gay-marriage, antiracist and multicultural in environment encourages a confidence in transnational connections’ (Vertovec Citation2009, 16). In this sense, London’s university environments mirror those of transnational firms, requiring extensive interactions with people of multiple nationalities and acting as a proxy for the kinds of cosmopolitanism encountered while working in a global city. From a Bourdieusian perspective, the university environment allows individuals to learn the ‘rules of the game’ thus cultivating dispositions into embodied social practices (Maton Citation2012, 56).

Graduate aims - Work effectively in multi-cultural, international teams and across disciplinary boundaries. (University 7, Teaching and Learning Strategy, Accessed June 2020)

Our students are diverse in their cultural backgrounds, nationalities and orientations; … can make its learning and teaching environment even more inclusive for students. We can ensure that different cultural backgrounds and perspectives are an integral part of our learning and teaching environment and that students are part of an academic community that treats its members with respect and creates equal opportunities for everyone to succeed, regardless of gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, cultural background or disability. Our students will be even better prepared for the global job market by learning to work in diverse groups and applying their knowledge across cultures and with a respect for different values and human experiences. (University 7, Teaching and Learning Strategy, Accessed June 2020)

The recognition and celebrating of different identities noted in the above excerpts is one of the key tenants of critical cosmopolitanism, which actively seeks out alternatives to western conceptions by embracing alternatives histories of thought and practice. The aim is to move the debate away from global centres of power and better represent the lived experiences of diverse peoples (Pollack et al. Citation2000). Chinese returnees in one study remarked how overseas education had not only developed their communication skills but had also fostered a more in-depth understanding of cultures which supported them in obtaining employment in Beijing (Hao and Welch Citation2012). Indeed, Heusinkvelt (Citation1997, 489) pointed out that perhaps ‘the greatest shock may not be in the encounter with a different culture but in the recognition of how our own culture has shaped us and what we do’.

Global citizenship

From calls for global citizenship or world citizenship to contemporary ideas of ‘flexible citizenship’ Ong (Citation1999) and ‘new argonauts’ Saxenian (Citation2007), cosmopolitan ideals have long been concerned with gaining a new identity. University 1 follows a growing number of universities (Birk Citation2011) in offering a programme of active global citizenship connected to its mission statements and its concerns with global political issues. However, despite the intellectual signalling under the ‘Grand Challenges’ theme the details make clear that its Global citizenship programme is rooted in neo-liberal and aesthetic conceptions. Specifically, the utility of foreign languages.

Grand Challenges themes of global health and justice and equality and foster the development of skills for global citizenship, such as campaigning and social entrepreneurship. (University 1, Global Citizenship Programme 2016)

… all UK students should either enter with, or have developed by graduation, a basic level of modern foreign language competence … we will ensure that our students are well-prepared for future career success in a global economy and for a lifetime of intellectual and personal development through further academic study, research and life learning courses. (University 1, Global Citizenship Programme 2016)

Cosmopolitanism

Only one strategy made explicit reference to cosmopolitanism. The extract emphasises aesthetic cosmopolitanism as a ‘attitude’ nurtured within the university and cultivated by its diverse staff and location within the global city of London. The extract also makes note of how cosmopolitan attitudes are not geographically bound but instead flow out from London through the global connections and assignments those at the university must undertake.

Situated in central London, one of the world’s most dynamic and connected cities, University 3 is at the heart of national and global networks while actively engaging with the communities in which it is based. As an international centre for academic excellence, we are part of the global conversation with policy and lawmakers, cultural influencers, business and entrepreneurs, medical professionals and religious leaders. This London advantage brings together people and resources across many spheres, enabling locally-led and internationally informed research that can impact across London, the country and the world. University 3 is inextricably linked to London. This means that the people who make up our university are cosmopolitan and diverse: something of London is reflected in them, and that attitude radiates beyond London to the benefit of a national and global society. (University 3, Education Strategy 2017)

A single reference to Brexit was also to be found within the strategies examined. This is surprising given the likely impact leaving the European Union will hold for all most all universities from students’ numbers to research grant funding. The reference made by University 3 briefly acknowledges that change is forthcoming and will influence both past and future students. Across all of the strategies mention of Global Britain was absent, something which is perhaps not surprising given the ongoing lack of clarity surrounding the idea and the need for it to be clearly articulated in policy or a set of principles. This will however be something to watch for in future iterations of education strategies.

In summary, the analysis presented here has uncovered stances of cosmopolitanism expressed in selected university strategies and provides tentative suggestions of the conflicted conceptions of cosmopolitanism at play within universities. Most strategies espouse intellectual cosmopolitanism while simultaneously outlining numerous aesthetic practices. To the extent that each stance was integrated into some form, it is important to highlight the intellectual ideas were most numerous. The education strategies of those universities with the highest concertation of international students, University 1 and University 3 were notably more attuned to aesthetic conceptions of cosmopolitanism that have a relationship with global capitalism. Most notably for the premise of this study, only two strategy documents made explicit reference to supporting their students to compete in a global environment and acknowledge the utility of their student diversity.

Discussion

In this paper, I have identified two stances – intellectual and aesthetic to examine which conceptions of cosmopolitanism are embedded into university strategies. By focusing on the aspirations of GMC my analysis highlights tensions between the stances of cosmopolitanism privileged in higher education and those which are helpful in securing elite employment. These tensions raise important questions for those universities who rely financially on ISM, and for the GMC who undertake cosmopolitan positioning. They also ask larger questions about the purpose of contemporary higher education in the era of ISM. Is it preparing students to add societal value, supporting them to achieve individual prosperity, driving economic development or signalling employability?

The decision to analyse publicly available university strategies was two-fold. Firstly, it placed the researcher in the shoes of the teaching staff who apply these strategies. Secondly, it enabled an examination of intent; the strategy documents provide a public window into university practice. Analysing strategies from multiple institutions allowed the particular cosmopolitanism stances to be revealed and provided an opportunity to identify and examine the different approaches used. From this case study four findings can be drawn. First, across all strategies, the intellectual stance of cosmopolitanism was most dominant invoking notions of social justice and tackling global challenges such as ‘climate change, women’s health, mental health’. Second, the aesthetic stance was strongest in those universities with the highest number of international students, with reference to developing global skills and networks, and through initiatives such as a global citizenship programme, placement opportunities and graduate attributes/outcomes. Perhaps surprisingly given its relationship with critical cosmopolitanism, the discourses around inclusivity and diversity had some of the strongest alignment with aesthetic stance. This again hints at the internal tensions of cosmopolitism. Third, a clear divide between Russell Group and Post-1992 universities was found. The Post-1992 ‘new universities’ espousing far less cosmopolitan intent across both stances. This is possibly due to the lower number of international students enrolled. However, it should be noted that fewer strategies from Post-1992 were examined, so this remains an open question. Fourthly, in most strategies, the positionality of London as a global city was elevated above that of the UK. This finding aligns with ideas found in global cities literature such as ‘education cities’ or ‘education hubs’ Knight (Citation2018), it also strengthens recent interventions in economic geography which seek to interpret the workings of the world economy through cities and not necessarily nation states.

By developing the intellectual and aesthetic stance to analyse conceptions of cosmopolitanism these finding offer a more in-depth understanding of what form of cosmopolitanism is reproduced in higher education. Importantly, these findings also call for research into cosmopolitanism in action, in order to open the ‘black box’ of how specific stances of cosmopolitanism are reproduced through pedagogic discourse and educational experiences. In the case of UK higher education which relies heavily on ISM and is facing the twin challenges of Covid-19 and Brexit, it is also important to recognise the economic dimension to cosmopolitanism. That is, can UK higher education make use of its structural cosmopolitan advantages (e.g. London, multi-culturalism, transnational business) to attract the GMC and overcome recent challenges to ISM? Here, the novel idea of ‘cosmopolitan nationalism’ developed by Maxwell et al. (Citation2020) raises interesting questions for future research on the cosmopolitan orientation of UK higher education system in the context of Global Britain.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for Prof. Sarah Hall’s personal support and professional advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Appiah, K. A. 2007. Cosmopolitanism. Ethics in a World of Strangers.

- Ashwin, P., A. Abbass, and M. McLean. 2012. “The Pedagogic Device: Sociology, Knowledge Practices and Teaching-Learning Processes.” In Tribes and Territories in the 21st-Century, 118–130. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016. Census QuickStats. Greater Sydney. Accessed February 8 2021. https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/1GSYD?opendocument.

- Baildon, M., and T. Alviar-Martin. 2020. “Taming Cosmopolitanism: the Limits of National and Neoliberal Civic Education in two Global Cities.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 40 (1): 98–111. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2020.1725428.

- Bailey, A. J. 2001. “Turning Transnational: Notes on the Theorisation of International Migration.” International Journal of Population Geography 7 (6): 413–428.

- Ball, S. J. 2016. “The Future of Elite Research in Education Commentary.” In Elite Education: International Perspectives, edited by C. Maxwell, and P. Aggleton, 69–74. New York: Routledge.

- Bathelt, H., A. Malmberg, and P. Maskell. 2004. “Clusters and Knowledge: Local Buzz, Global Pipelines and the Process of Knowledge Creation.” Progress in Human Geography 28 (1): 31–56. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132504ph469oa.

- BBC. 2020. Coronavirus: Queen's University Charters Plane for Chinese Students. Accessed January 8 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-53335074.

- Beaverstock, J. V. 2002. “Transnational Elites in Global Cities: British Expatriates in Singapore’s Financial District.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 33 (4): 525–538. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(02)00036-2.

- Beaverstock, J. V. 2005. “Transnational Managerial Elites in the City: British Highly-skilled Intercompany Transferees in New York City's Financial District.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 245–268. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183042000339918.

- Beaverstock, J. V. 2018. “New Insights in Reproducing Transnational Corporate Elites: The Labour Market Intermediation of Executive Search in the Pursuit of Global Talent in Singapore.” Global Networks 18: 500–522. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12196.

- Beck, U. 1998. Cosmopolitan Manifesto. New Statesman. March 20, 1999. Accessed January 12 2021. https://www.newstatesman.com/node/150373.

- Beck, U. 2001. “Interview with Ulrich Beck.” Journal of Consumer Culture 1 (2): 261–277. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/146954050100100209.

- Beck, U. 2006. The Cosmopolitan Vision. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

- Beck, U., and N. Sznaider. 2006. “Unpacking Cosmopolitanism for the Social Sciences: A Research Agenda.” British Journal of Sociology 57: 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01250.x.

- Bell, D. 2017. This is the Decade for UK Universities to be Bold, Brave and Ambitious. Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office Blog. Accessed August 12 2020. https://blogs.fcdo.gov.uk/fcoeditorial/2017/01/19/sir-david-bell-fcos-global-britain-campaign-publish-on-thursday/.

- Bernstein, B. 2000. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity. Rowman and Littlefield.

- Birk, T. A. 2011. Becoming Cosmopolitan: Toward a Critical Cosmopolitan Pedagogy. Unpublished PhD thesis. The Ohio State University.

- Bloomberg. 2017. What's the Matter With a ‘Cosmopolitan Bias'?. Accessed January 10 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-08-02/what-is-cosmopolitan-bias-anyway.

- Bourdieu, P. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1999. The State Nobility: Elite Schools in the Field of Power. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P., and W. Loïc. 2013. “Symbolic Capital and Social Classes.” Journal of Classical Sociology 13 (2): 292–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468795X12468736.

- Boussebaa, M. 2020. “In the Shadow of Empire: Global Britain and the UK Business School.” Organization 27 (3): 483–493. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508419855700.

- Brown, P., S. Power, G. Tholen, and A. Allouch. 2016. “Credentials, Talent and Cultural Capital: A Comparative Study of Educational Elites in England and France.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 37 (2): 191–211. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2014.920247.

- Calhoun, C. J. 2002. “The Class Consciousness of Frequent Travellers: Toward a Critique of Actually Existing Cosmopolitanism.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 101 (4): 869–897. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-101-4-869.

- Castells, M. 2000. The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell.

- The Complete University Guide. 2020. University League Tables 2020. Accessed December 10 2020. https://www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk/league-tables/rankings.

- Davies, I., and P. Graham. 2009. “Global Citizenship Education: Challenges and Possibilities.” In The Handbook of Practice and Research in Study Abroad: Higher Education and the Quest for Global Citizenship, edited by L. Ross, 61–77. New York: Routledge.

- Delanty, G. 2006. “The Cosmopolitan Imagination: Critical Cosmopolitanism and Social Theory.” The British Journal of Sociology 57 (1): 25–47. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2006.00092.x.

- De Wilde, P., R. Koopmans, W. Merkel, and M. Zürn. 2019. The Struggle Over Borders: Cosmopolitanism and Communitarianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dubai Statistics Center. 2019. Number of Population Estimated by Nationality- Emirate of Dubai. Accessed January 10 2021. https://www.dsc.gov.ae/Report/DSC_SYB_2019_01%20_%2003.pdf.

- FCO (Foreign and Commonwealth Office). 2019. Global Britain: delivering on our international ambition. Accessed January 10 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/global-britain-delivering-on-our-international-ambition.

- Friedman, S., and D. Laurison. 2019. The Class Ceiling: Why it Pays to be Privileged. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Gov.UK. 2019. International Education Strategy: Global Potential, Global Growth. Policy paper. Accessed July 18 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/international-education-strategy-global-potential-global-growth.

- Gov.UK. 2020. EU Student Funding Continued for 2020/21. Accessed January 10 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/eu-student-funding-continued-for-202021.

- Hall, S. 2017. “(Post)Graduate Education Markets and the Formation of Mobile Transnational Economic Elites.” In Knowledge and Networks, edited by G. Johannes, L. Emmanuel, and H. Ingmar, 103-116. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45023-0_6

- Hall, S., and L. Appleyard. 2009. “'City of London, City of Learning'? Placing Business Education Within the Geographies of Finance.” Journal of Economic Geography 9 (5): 597–617. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbp026.

- Hannerz, U. 1990. “Cosmopolitans and Locals in World Culture.” Theory, Culture and Society 7 (2–3): 237–251. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/026327690007002014.

- Hannerz, U. 1996. Transnational Connections Culture, People, Places. London: Routledge.

- Hannerz, U. 2006. Two Faces of Cosmopolitanism: Culture and Politics. Barcelona: Fundació CIDOB.

- Hao, J., and A. Welch. 2012. “A Tale of Sea Turtles: Job-Seeking Experiences of hai gui (High-Skilled Returnees) in China.” Higher Education Policy 25 (2): 243–260. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315881607.

- HEPI. 2018. The Costs and Benefits of International Students by Parliamentary Constituency. Accessed December 10 2020. https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Economic-benefits-of-international-students-by-constituency-Final-11-01-2018.pdf.

- HESA (Higher Education Statistics Authority). 2019. Where Do the Students Come From?. Accessed January 18 2021. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/where-from.

- HESA (Higher Education Statistics Authority). 2020. Higher Education Student Data – Open Data Release. Accessed November 16 2020. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/05-02-2020/he-student-data.

- Heusinkvelt, P. 1997. Pathways to Culture: Readings in Teaching Culture in the Foreign Language Class. Yarmouth: Maine Intercultural Press.

- Igarashi, Hiroki, and Hiro Saito. 2014. “Cosmopolitanism as Cultural Capital: Exploring the Intersection of Globalization, Education and Stratification.” Cultural Sociology 8 (3): 222–239. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975514523935.

- Johnson, J., B. Lynch, and T. Gillespie. 2020. Universities Open to the World, How to Put the Bounce Back in Global Britain. The Policy Institute, Kings College London; Harvard Kennedy School. Accessed November 3 2020. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute/assets/universities-open-to-the-world.pdf.

- Joy, S., Game Annilee M., and Ishita G. Toshniwal. 2020. Applying Bourdieu’s Capital-Field-Habitus Framework to Migrant Careers: Taking Stock and Adding a Transnational Perspective. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31, no. 20: 2541-2564. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1454490

- Kenny, M., and N. Pearce. 2019. “Brexit and the ‘Anglosphere'.” Political Insight 10 (2): 7–9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/2041905819854308.

- Kim, J. 2011. “Aspiration for Global Cultural Capital in the Stratified Realm of Global Higher Education: Why Do Korean Students Go to US Graduate Schools?” British Journal of Sociology of Education 32 (1): 109–126. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2011.527725.

- Kim, J. 2012. “The Birth of Academic Subalterns: How Do Foreign Students Embody the Global Hegemony of American Universities?” Journal of Studies in International Education 16 (5): 455–476. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315311407510.

- Knight, J. 2018. “International Education Hubs.” In Geographies of the University, edited by P. Meusburger, M. Heffernan, and L. Suarsana, 637–655. Cham: Springer.

- Lim, L., and Michael W. Apple. 2018. “The Politics of Curriculum Reforms in Asia: Inter-Referencing Discourses of Power, Culture and Knowledge.” Curriculum Inquiry 48 (2): 139–148. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2018.1448532.

- Maton, K. 2012. “Habitus.” In Pierre Bourdieu: Key Concepts, Grenfell. 2nd ed., edited by J. Michael, 48–64. Durm: Acumen Publishing Limited.

- Maxwell, C., and M. Yemini. 2019. “Modalities of Cosmopolitanism and Mobility: Parental Education Strategies of Global, Immigrant and Local Middle-Class Israelis.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 40 (5): 616–632. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2019.1570613.

- Maxwell, C., M. Yemini, L. Engel, and M. Lee. 2020. “Cosmopolitan Nationalism in the Cases of South Korea.” Israel and the U.S. British Journal of Sociology of Education 41 (6): 845–858. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2020.1755223.

- McDowell, L. 1997. Capital Culture: Gender at Work in the City of London. Oxford: Blackwell.

- McLean, M., A. Abbas, and P. Ashwin. 2013. “A Bernsteinian View of Learning and Teaching Undergraduate Sociology-Based Social Science.” Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences 5 (2): 32–44. DOI: https://doi.org/10.11120/elss.2013.00009.

- Meyer, D. R. 2015. “The World Cities of Hong Kong and Singapore: Network Hubs of Global Finance.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 56 (3-4): 198–231. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715215608230.

- Migration Policy Institute. 2016. U.S. Immigrant Population by Metropolitan Area. Accessed January 18 2021. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/us-immigrant-population-metropolitan-area?width=1000&height=850&iframe=true.

- Nicolopoulou, K., Nada K. Kakabadse, K. P. Nikolopoulos, J. M. Alcaraz, and K. Sakellariou. 2016. “Cosmopolitanism and Transnational Elite Entrepreneurial Practices: Manifesting the Cosmopolitan Disposition in a Cosmopolitan City.” Society and Business Review 11 (3): 257–275. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/SBR-01-2016-0001.

- Nussbaum, M. 1994. Patriotism and Cosmopolitanism. Boston Review. Accessed November 8, 2020. http://bostonreview.net/martha-nussbaum-patriotism-and-cosmopolitanism.

- O'Connor, L., and D. Faas. 2012. “The Impact of Migration on National Identity in a Globalized World: A Comparison of Civic Education Curricula in England, France and Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 31 (1): 51–66. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2011.579479.

- OECD. 2019. Education at A Glance, UK Country Note. Accessed November 8 2020. https://www.oecdilibrary.org/docserver/aa0f48a8en.pdf?expires=1590620731&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=62B07AC811E935B2FBB9C500641DB753.

- OFS (Office for National Statistics). 2018. Population of the UK by Country of Birth and Nationality: July 2018 to June 2019. Accessed January 18 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/bulletins/ukpopulationbycountryofbirthandnationality/july2018tojune2019.

- Ong, A. 1999. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Oxley, L., and P. Morris. 2013. “Global Citizenship: A Typology for Distinguishing Its Multiple Conceptions.” British Journal of Educational Studies 61 (3): 301–325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2013.798393.

- Pak, S.-Y., and M. Lee. 2018. “Hit the Ground Running’: Delineating the Problems and Potentials in State-led Global Citizenship Education (GCE) Through Teacher Practices in South Korea.” British Journal of Educational Studies 66 (4): 515–535. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2018.1533101.

- Piwoni, E. 2020. “Exploring Disjuncture: Elite Students’ Use of Cosmopolitanism.” Identities 27 (2): 173–190. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2018.1441691.

- Pollack, S., H. K. Bhabha, C. A. Breckinridge, and D. Chakrabart. 2000. “Cosmopolitanisms.” Public Culture 12 (3): 577–589. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-12-3-577.

- Project Atlas, Institute of International Education. 2020. Global Mobility Trends. 2019 Release. Accessed January 8 2021. https://www.iie.org/en/Research-and-Insights/Project-Atlas/Explore-Data/Infographics/2019-Project-Atlas-Infographics.

- QS Top Universities. 2020. World University Rankings. Accessed December 18 2020. https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2020.

- Rapoport, A. 2010. “We Cannot Teach What We Don’t Know: Indiana Teachers Talk About Global Citizenship Education.” Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 5 (3): 179–190. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197910382256.

- Sassen, S. 2016. “The Global City: Enabling Economic Intermediation and Bearing Its Costs.” City & Community 15 (2): 97–108. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12175.

- Saxenian, A. 2007. The New Argonauts: Regional Advantage in a Global Economy. Harvard University Press.

- Schweisfurth, M. 2006. “Education for Global Citizenship: Teacher Agency and Curricular Structure in Ontario Schools.” Educational Review 58 (1): 41–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910500352648.

- Shanghai Basic Facts. 2020. Social Livelihood. Accessed December 28 2020. http://en.shio.gov.cn/img/2020-ShanghaiBasicFacts.pdf.

- Smith, P. M. 1999. “Transnationalism and the City.” In The Urban Movement, edited by R. Beauregard, and S. Body-Gendrot, 119–139. London: Sage.

- Statistics Canada. 2016. Census 2016 Number and Distribution (in percentage) of the Immigrant Population and Recent Immigrants in Census Subdivisions, Toronto, 2016. Accessed September 24 2020. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-cma-eng.cfm?LANG=Eng&GK=CMA&GC=535&TOPIC=7.

- Stornaiuolo, A., and T. N. Philip. 2021. Cosmopolitanism and Education. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Accessed June 11 2021. https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10. 1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-252.

- Su, F., and M. Wood. 2017a. “Towards an ‘Ordinary’ Cosmopolitanism in Everyday Academic Practice in Higher Education.” Journal of Educational Administration and History 49 (1): 22–36. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2017.1252734.

- Su, F., and M. Wood. 2017b. Cosmopolitan Perspectives on Academic Leadership in Higher Education. London: Bloomsbury.

- Szerszynski, B., and J. Urry. 2006. “Visuality, Mobility and the Cosmopolitan: Inhabiting the World from Afar.” British Journal of Sociology 57 (1): 113–131. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2006.00096.x.

- Tannen, D. 1994. Gender and Discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thrift, N. 2005. Knowing Capitalism. Theory, Culture and Society. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- The Times. 2020. Downing Street Plans New 5G Club of Democracies. Accessed January 10 2021. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/downing-street-plans-new-5g-club-of-democracies-bfnd5wj57.

- Tindal, S., H. Packwood, A. Findlay, S. Leahy, and D. McCollum. 2015. “In What Sense ‘Distinctive’? The Search for Distinction Amongst Cross-Border Student Migrants in the UK.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 64: 90–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.06.001.

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government. 2015. Population Summary. Accessed February 18 2021. https://www.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/ENGLISH/ABOUT/HISTORY/history03.html.

- Urry, J. 1995. Consuming Places. London: Psychology Press.

- US Census. 2019. QuickFacts New York city, New York. Accessed 23 July 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/newyorkcitynewyork

- Vertovec, S. 2002. Transnational Networks and Skilled Labour Migration. Transnational Communities, Working Paper 02–02. Oxford: University of Oxford.

- Vertovec, S. 2009. Transnationalism. Oxon: Routledge.

- Vertovec, S., and R. Cohen. 2002. Conceiving Cosmopolitanism: Theory, Context and Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Waters, L. J. 2007. “Roundabout Routes and Sanctuary Schools: The Role of Situated Educational Practices and Habitus in the Creation of Transnational Professionals.” Global Networks 7 (4): 477–497. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2007.00180.x.

- Waters, L. J. 2009. “In Pursuit of Scarcity: Transnational Students, ‘Employability’, and the MBA.” Environment and Planning 41 (8): 1865–1883. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1068/a40319.

- Waters, L. J. 2018. “International Education is Political! Exploring the Politics of International Student Mobilities.” Journal of International Students 8 (3), DOI: https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v8i3.66.

- Werbner, P. 2020. Anthropology and the New Cosmopolitanism: Rooted, Feminist and Vernacular Perspectives. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

- World Bank. 2019. Population, Total – Singapore. Accessed January 22 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=SG.

- Wright, Ewan, Ying Ma, and Euan Auld. 2021. “Experiments in Being Global: The Cosmopolitan Nationalism of International Schooling in China.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2021.1882293.

- Ye, J., and F. P. Kelly. 2011. “Cosmopolitanism at Work: Labour Market Exclusion in Singapore's Financial Sector.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (5): 691–707. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2011.559713.

- Yemini, Miri, and Claire Maxwell. 2018. “De-coupling or Remaining Closely Coupled to ‘Home’: Educational Strategies Around Identity-Making and Advantage of Israeli Global Middle-Class Families in London.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 39 (7): 1030–1044. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2018.1454299.

- Yemini, M., F. Tibbitts, and H. Goren. 2018. “Trends and Caveats: Review of Literature on Global Citizenship Education in Teacher Training.” Teaching and Teacher Education 77: doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.09.014.

- Yeoh, B. S. A., and S. Huang. 2011. “Introduction: Fluidity and Friction in Talent Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (5): 681–690. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2011.559710.