ABSTRACT

Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol retains a profound presence in Transatlantic seasonal celebrations and the popular image of the festive period. While the book’s reception in the United Kingdom has been well studied, its early progress through nineteenth-century American popular culture has received much less attention and existing accounts of its rise to popularity are contradictory. This article, therefore, is an attempt to trace the ways that American readers and audiences responded to this defining Transatlantic text in the decades between its first publication and Dickens’s death in 1870. After exploring its immediate reception in the wake of its first publication in America, I examine the changing status of A Christmas Carol in relation to both Dickens’s American reading tour of 1867–8 and the aftermath of his death – finding the book, throughout those decades, to be a crucial arbiter of both the popular idea of Christmas and the reputation of Dickens and his work more broadly.

In America, A Christmas Carol was dead: to begin with. At least, that’s one version of its first Transatlantic reception. The story goes like this: in 1842, Dickens had travelled to America. Feted as a literary hero throughout his sojourn in the New World, America’s adulation swiftly turned sour as Dickens began publishing books about his experiences in the United States. In both American Notes (1842) and Martin Chuzzlewit (serialised 1842–1844), Dickens painted a portrait of America that was less than flattering; both texts were received as a profound betrayal for the kindnesses that he had been shown during his visit. Arriving in the middle of this bad-tempered feud, A Christmas Carol, first published in London on 19 December 1843, got lost in the rancour. As Paul Davis has briefly summarised, ‘the Carol’s American reception was chilled by resentment’. According to Davis, it wasn’t until well into the twentieth century that Dickens’s Christmas vision was ‘as popular in America as it was in Britain’ (Citation1990b, 150). Penne Restad echoes the idea that, at least at first, ‘Americans were less enthusiastic’ about this seasonal offering (Citation1995, 136). But were they? Because contrarily, Walter E. Smith has recently declared, in his bibliographical history of American editions of the book: ‘The publication by the Harper Brothers of A Christmas Carol on 24 January 1844’—the first American edition—‘was sensational, and restored Dickens’s prominence […] several impressions of it appeared in the year. Other publishers rapidly produced copies’ (Citation2019, xv). Bah, Humbug-ish rejection or Scrooge-like redemption: how should we understand this pivotal moment in Transatlantic literary and popular culture?

It may be surprising that this is a difficult question to answer, and that a detailed account of A Christmas Carol’s early reception in America is lacking, given the uniquely prominent position that this Victorian book occupies in the American imagination. In Juliet John’s terms, A Christmas Carol ‘has been the most adapted, widely disseminated and commercially successful of all Dickens’s works’ (Citation2011, 79). More than that, as Davis notes, it has been ‘adapted, revised, condensed, retold, re-originated, and modernized more than any other work of English literature’ until it has become a ‘culture-text’, composed of its many iterations, that almost lives a life apart from its textual origins. This process remains a ‘continuing creative process in the Anglo-American imagination’—arguably, with the emphasis on American (Citation1990b, 110–11). If anything, Dickens’s book retains a greater hold on the American seasonal imagination than it does in the country of its creation: each year, new American adaptations and reworkings of A Christmas Carol are added to the pile and released to the world; each year, thousands of Americans flock to Dickens fairs to experience what the organisers of San Francisco’s leading immersive seasonal experience describe as ‘an evening in Victorian London’ where ‘it is always Christmas Eve’ and revellers can party with Mr. Fezziwig before experiencing ‘the illustrious author himself’ reading from A Christmas Carol (Citationdickensfair.com). Arguably, it is the single most significant Transatlantic text. In popular culture terms, Dickens’s festive London now exists primarily as an invented and imagined space that is neither British nor American but a hyperreal hybrid of both.

Yet how did this extraordinary significance develop, and how did the first generations of Americans to encounter this text incorporate A Christmas Carol into their own sense of the season? The foundational scholarly histories of Christmas in America by Penne Restad (Citation1995), Stephen Nissenbaum (Citation1997) and Karal Ann Marling (Citation2000) all reference Dickens and his ongoing significance for the development of seasonal celebrations in the United States, but none gives a detailed account of the book’s initial arrival across the Atlantic, and the incremental, sometimes equivocal waves of interest and enthusiasm that eventually assured its apparent seasonal immortality. Dickens’s broader reception in and travels through America have been the subject of a number of studies, most notably W. Glyde Wilkins’s pioneering Charles Dickens in America (Citation1911), Jerome Meckier’s Innocent Abroad: Charles Dickens’s American Engagements (Citation1990), and Robert McParland’s Charles Dickens’s American Audience (Citation2010). Similarly, A Christmas Carol itself has earned a number of compelling book-length studies, particularly Paul Davis’s The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge (Citation1990a) and Fred Guida’s A Christmas Carol and its Adaptations (Citation2000). But in the former group, A Christmas Carol receives only passing attention, and in the latter, the text’s early reception in nineteenth-century America is also peripheral. Philip Collins useful survey of ‘The Reception and Status of the Carol’ (Citation1993) also has little to say about the book’s impact in America.

In this article, therefore, I trace the early life of A Christmas Carol in America, following its progress in the American imagination through three defining waves. First, I examine the immediate responses to both the novel and its adaptations in the year after its first publication in America, finding early enthusiasm tempered by ill-feeling towards Dickens himself. Second, I explore the prominence of A Christmas Carol in Charles Dickens’s reading tour of 1867 and 1868, a moment which reshaped America’s relationship to the text in ways both emotional and physical. Finally, I trace the ways in which Dickens’s death in 1870 nuanced and heightened the meaning of A Christmas Carol for American readers in the festive period immediately following his demise, even as others were starting to question whether Dickens’s seasonal text still had a place in American celebrations or in an American literary culture increasingly shaped by realism. What emerges, then, is a portrait of a book, which serves as a crucial mediator: between Dickens and his American audience, between those audiences and a growing idea of Christmas in American life, and between the shifting literary cultures on both sides of the Atlantic. I hope that this approach also speaks to David Bordelon’s recent articulation of the ‘gaps in scholarship’ which surround our understanding of the American circulation of work by popular British writers like Dickens in this period and reveals some hidden aspects of the ‘strong imprint of Dickens’ that can found in nineteenth-century American culture – in particular, the strong imprint of A Christmas Carol that is still powerfully in evidence today (Citation2020, 100).

‘This is Capital, (Although from Dickens, Whom We Love Not!)’

In December 1843, just as A Christmas Carol was finding its first enthusiastic British audience, the pioneering American children’s magazine Merry’s Museum gave its young readers a primer on the traditions of the season which began with some striking claims:

This famous holiday takes place on the 25th of December. It is little observed, at the present day, in comparison of what it was in former times. Even in England, it is now chiefly celebrated by family parties and services in the churches, these being decorated with evergreens. In this country, it is little noticed, except by persons belonging either to the Catholic or Episcopal church. (Citation1843, 168)

Whatever exaggerations may lurk in this brief account, Merry’s Museum was right that in 1843 Christmas was far from being a universal American holiday; it was only erratically celebrated, with much regional variation. But times were changing: as Stephen Nissenbaum has elucidated, this was precisely the moment that ‘a new kind of holiday celebration, domestic and child-centred’ was emerging in American life (Citation1997, 99). Contrary to Merry’s Museum’s dismissal of the very idea of an American Christmas, the magazine Brother Jonathan had printed, as early as 1842, a vigorous celebration of the day: ‘To-morrow will be Christmas, jolly, rosy Christmas […] All hail Christmas! say we’. But, Brother Jonathan noted, its delights were not evenly distributed: ‘We should remember, while enjoying the festivities of the day, that to the poor, Christmas brings but few pleasures, unless some thoughtful neighbor for one day in the year spreads their humble board for them’ (Citation1842, 949–95). A Christmas Carol—with its combined message of festive cheer and seasonal charity—therefore arrived at an auspicious moment in the development of American Christmas culture. The first American edition of the book wasn’t published by Harpers until 24 January 1844, and was thus unable to benefit from the immediate seasonal timeliness of the British edition’s arrival in bookshops just before Christmas. Nonetheless, it was soon available from a number of publishers as well as being serialised and excerpted in a variety of periodicals (Smith Citation2019, 28–48). But in this time of seasonal change, and at a moment when Dickens himself had wounded national pride, what kind of reception did this little book receive? .

Figure 1. An advertisement for Harpers’ first American edition of A Christmas Carol published in the New-York Daily Tribune on January 24 1844 (3).

Lydia Maria Child, in one of the letters from New York that she wrote for the National Anti-Slavery Standard, gave perhaps the earliest account of the book’s arrival in America. In a column dated 26 January 1844, just two days after Harpers released their edition, she noted its apparently muted appearance:

The newspapers announce it merely as ‘a ghost story’, and scarcely utter a word in its praise. If it had been published before the author wounded our national vanity so deeply, it would have met quite a different reception; for in fact it is a most genial production, one of the sunniest bubbles that ever floated on the stream of light literature.

Before long, more reviews started to appear and to a remarkable degree early American assessments of A Christmas Carol were unanimously positive. While some resentments surrounding American Notes were clearly felt, admiration, however grudging, flowed towards Dickens’s new festive book. As early as 26 January 1844, just two days after Harpers had released the first American edition, the Alexandria Gazette reprinted a long, laudatory review from the London Spectator, which recommended the book as ‘a most appropriate Christmas offering, and one which if properly made use of, may yet, we hope, lead to some more valuable result to the season of merry-making than mere amusement’ (Citation1844c, 2). American reviews of the Harpers edition soon followed. Magazine for the Million was initially a little reserved in its praise: ‘This is a short story […] worthy of the unaffected friendship and affection with which Mr. Dickens was received on his visit to the United States […] which he has so unworthily repaid of late’. Still, for all that, the reviewer had to confess that ‘the Christmas Carol is a glorious good story, and will produce laughter and tears, alternately, from those who are susceptible of emotions of humor and pathos’ (Citation1844, 18). In its brief review, the Southern Literary Messenger noted approvingly, ‘This is worthy of the better days of Boz […] There is many a Scrooge in the world, who might see his picture here, and be better by imitating the reformation of the hero of the tale’ (Citation1844a, 188). In March 1844, The Knickerbocker addressed the awkward circumstances of A Christmas Carol’s American arrival head-on, and with good humour. Dickens was allowed to ‘indulge in ridicule against alleged American peculiarities, or broad caricatures of our actual vanities’ in every alternate work that he published, the reviewer began, as long as ‘he would now and then present us with an intellectual creation so touching and beautiful as the one before us’. Immediately, they judged A Christmas Carol to be ‘the most striking, the most picturesque, the most truthful, of all the limnings which have proceeded from its author’s pen’. Its final verdict was no less decisive, and certainly evinced no trace of remaining animus against the author: ‘We have in conclusion but three words to say to every reader of the Knickerbocker who may peruse our notice of this production: READ THE WORK’ (Citation1844d, 276–81). Contained within that exhortation was a sense, apparent across the book’s first reception in America, that this was a text with a social purpose that could do good in the world. Only the Eclectic Magazine took some issue with the ethics of the text, finding its logic ‘feudal’, and dependent on ‘munificent patrons’: ‘The processes whereby poor men are to be enabled to earn good wages, wherewith to buy turkeys for themselves, does not enter into the account; indeed, it would quite spoil the denouement’ (Citation1844e, 482). One other grumble came from woman of letters Sarah Preston Hale, who wrote to her son Edward Everett Hale (quoted in Zboray and Zboray Citation2006) to complain about the inferior production quality of the Harpers edition: ‘you who have not seen the nice English edition may like it, but it is enough to make any body sick who has seen the other as some folks have’. But even she concluded, ‘the story is pretty, print it up as you will’ (226–27).

As in Britain, A Christmas Carol entered into American culture in other ways as well. American theatrical adaptations swiftly made their way onto the stage. For Christmas 1844, for example, it appeared in at least two rival versions in New York, at the Chatham and the Park Theatres. On Boxing Day, 1844, the New York Herald noted that the pit of the Chatham had been crammed with ‘three hundred news boys […] in an animated contest with the police officers’. Such distractions rather overshadowed the performance of A Christmas Carol, which ‘may have been well or ill played—for certainly nobody was the wiser of it’ (Citation1844f, 2). But the Anglo-American was warm in its praise: ‘It is the very best thing of the kind that has appeared this long time, and will undoubtedly have a tremendous run’ (Citation1844b, 237–38). The adaptation appearing at the Park was more widely celebrated, and lasted longer in the memory. William Henry Chippendale—a London-born actor who performed at the Park from 1836 until his return to England in 1853—played Scrooge in British playwright Edward Sterling’s version of the text to much acclaim, and revived the role repeatedly (New York Times, January 6, Citation1888, 5; Ireland Citation1867, 2:434). In his classic account of Plays and Players from Citation1875, Laurence Hutton remembered well the powerful—and, indeed, defining—effect of seeing Chippendale in the role: ‘Notwithstanding the number of years that have elapsed […] we still vividly remember Scrooge on that stage, and can never think of Dickens’s Scrooge other than as Mr. Chippendale represented him to us’. According to Hutton, this adaptation was the ‘only representation of the “Christmas Carol” on the stage, in which the entire ghost business has been enacted’, which may well account for its lingering power for the viewer: ‘Marley’s Ghost was as real to us as if we had seen it with Scrooge’s own eyes […] we saw Marley’s face in the knocker as plainly as Scrooge saw it, and it had almost the same effect upon us’ (Citation1875, 72–73).

Taking stock in January 1845, the Broadway Journal succinctly summed up the situation:

We said a good many severe things, even malicious, about Dickens, as soon as he left us; but we seized on his Christmas Carol with as hearty a good will as old Scrooge poked his timid clerk in the ribs the morning after Christmas (Citation1845b, 2).

‘I Do Not See How ‘The Christmas Carol’ Can Be Read and Acted Better’

That Dickens was established as a key component of literary Christmases by the time of the Civil War is clear. In the Atlantic in 1862, Rebecca Harding Davis would refer to him as ‘the priest of the genial day’ in a description of a Christmas dinner (Citation1862, 293). By this point, A Christmas Carol had been followed by Dickens’s other Christmas books and numerous Christmas editions of Household Words, all of which had made sure of his fixed position in the seasonal imagination on both sides of the Atlantic. But the particular and peculiar presence of A Christmas Carol in the heart of an American Christmas was about regain a renewed prominence. A tantalising glimpse of Christmases yet to come was published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in August 1861, when Henry Neill reported on a reading of the book that Dickens had recently given in London. In the middle of summer, as the Civil War warmed up back home, Neill transported Harper’s readers to St James’s Hall, Piccadilly where they could vicariously experience a Dickensian Christmas. Neill was hardly stinting in his praise for Dickens: ‘the greatest actor I had seen in England […] an artist who realized for the first time positively my highest conceptions of the art’. The affective power of the reading also led him to an extraordinary tribute to ‘that little Christmas story’ which ‘had already spoken for itself to hundreds of thousands of the old and young, and had left the impression of its characters upon all hearts capable of receiving an impression at all’. There was, Neill asserted, no need to rehearse the plot of the Carol for Harper’s readers, since it apparently occupied such a deep, genetic place in the life of a contemporary American Christmas: ‘is it not written among the bright holly-berries of every Christmas tree, and deep down amidst the uttermost plums of every Christmas pudding?’ At the end of the reading, Neill was left feeling quite ‘spooney’—a sensation he apparently shared with Lord John Russell, British Foreign Secretary and sometime Prime Minister, who Neill witnessed ‘doing something […] with his handkerchief when the death of Tiny Tim was suggested’ (Citation1861, 365–368).

Americans did not have to wait long to experience this extraordinary performance for themselves: in December 1867, there was one hot ticket in town. A quarter of a century after his first visit to the United States, Dickens was back—and this time, he was reading to the American public. At first, the American press had been a little wary of this new encounter. Memories of the aftermath of Dickens’s previous time across the Atlantic still lingered. ‘It is understood that Mr. Dickens will again come to the United States’, Harper’s Weekly announced in September 1867, before warning: ‘Of course the enthusiasm of his first reception will not be repeated. The extravagant and grotesque excesses into which a truly loyal and beautiful feeling was betrayed by its own ardor will be succeeded by the temperate and sober admiration of long experience’ (Citation1867b, 562). In his diary, lawyer George Templeton Strong also grumbled that ‘Mr. Dickens never uttered one word of sympathy with us or our national cause’, and declared flatly, ‘I am in no fever to hear him’. Still, in the same diary entry, Strong did confess to one element of curiosity: ‘I should like to hear him read the Christmas Carol: Scrooge, and Marley’s Ghost, and Bob Cratchit’ (Citation1952, 173).

American reluctance didn’t last long after Dickens’s arrival in Boston on November 19, and excitement for his readings swiftly built. Early in December, Harper’s Weekly published an early illustration of ‘Charles Dickens as he Appears When Reading’, as well as a breathless short item describing the excitement that his presence in America had already generated: ‘The desire to hear his reading is manifested among all classes; and nearly ten thousand tickets were sold for the short course of readings in Boston’ (Citation1867d, 782). By the end of the month, interest in this growing cultural sensation had abated little. This time, Harper’s provided an illustration of the extraordinary queue of people that had gathered when the release of more tickets for Dickens’s readings in New York had been announced: ‘Although the sale was announced to begin at nine A.M., on December 11, the throng of purchasers began to assemble at ten o’clock on the night before, and at least 150 persons waited in the line or queue all night’ (Citation1867h, 829). Enthusiasm for his performances remained high until Dickens returned to England in April 1868, having performed dozens of readings from Portland, Maine to Buffalo, New York to Washington D.C.—and many points in between.

Figure 2. ‘Charles Dickens as he appears when reading’, Harper’s Weekly (December 7th Citation1867c, 777).

Figure 3. ‘Buying Tickets for the Dickens Readings at Steinway Hall’, Harper’s Weekly (December 28th Citation1867a, 829).

A Christmas Carol was at the heart of Dickens’s extraordinary popularity during his triumphant return to America. In many ways this is unsurprising since it had been a major part of his repertoire after he began giving public readings in 1853. In December that year, he had selected the book, in its entirety, for his first charitable performance in front of a paying audience at Birmingham Town Hall because of previous private successes where, according to Dickens, its reading had ‘a great effect on the hearers’ (Fitzsimons Citation1970, 18). By the time that Dickens returned to America in 1867, he was no longer performing the Carol unabridged but had trimmed the text so that it could form part of a programme with another reading—usually, an extract from The Pickwick Papers. As Amanda Adams notes, Dickens’s reading version of the text ‘represents his most theatrical adaptation of a work’, reducing the role of the narrator in ways which ‘push the reading toward dramatic theatre’ (Citation2011, 230). Raymund Fitzsimons has calculated, ‘Of the nine Readings that comprised the American repertoire, the Carol and the Pickwick Trial’—generally performed together—‘held pride of place’ (Citation1970, 124). It is also clear that the wintery timing of Dickens’s appearances undoubtedly helped to amplify the significance of these dramatic Carol readings. A performance in Boston on Christmas Eve was particularly ‘emotional’, to borrow Fitzsimons’ term, given extra resonance because of its timing. Dickens certainly felt so. On Boxing Day, ‘depressed and miserable’ because of a ‘frightful cold’, Dickens paid particular tribute to this audience in a letter to his eldest daughter Mary: ‘the Bostonians had been quite astounding in their demonstrations. I never saw anything like them on Christmas Eve’ (Storey Citation[1999] 2016). Annie Fields was in the audience that night, and heartily agreed: ‘Ah! How beautiful it was! How everybody felt it! How that whole house rose and cheered!’ (quoted in Curry Citation1988, 12). Even after the end of the festive period, the Carol remained central to Dickens’s reading programme, and responses hardly dimmed. ‘They took it so tremendously last night that I was stopped every five minutes’, Dickens wrote to his sister-in-law Georgina Hogarth after a performance in Boston on February 27th, ‘One poor young girl in mourning burst into a passion of grief about Tiny Tim, and was taken out’ (Storey Citation[2002] 2016). The New York Times reported a less dramatic, but no less heartfelt, expression of audience enthusiasm: ‘“I could hear him read the Christmas Carol every night”, said an enthusiastic lady on quitting Steinway Hall last evening’ (Citation1867g, 4).

A Christmas Carol was central, too, to the discussions and reviews of Dickens’s readings that swiftly appeared in the popular press, keeping the book at the forefront of the imaginations of Americans in the run up to Christmas and beyond, instructing them how to respond to the text. The New York Herald gave significant column space to a review of Dickens’s first performance at Steinway Hall, and focussed at length on his interpretation of A Christmas Carol:

In the outset his voice appeared a little weak and husky, but after a few lines had been recited and with the emphatic announcement that ‘Old Marley was as dead as a door nail’, and that ‘Scrooge knew he was dead’, the reader began to warm up to his work and the house began to realize the face that the first comedian of the present generation was before them, acting the various characters of one of the prettiest of the domestic dramas of Dickens, just as Dickens himself would wish it done.

The resulting reading was ‘a beautiful play’. According to the reviewer, the audience particularly responded to Dickens’s interpretation of Scrooge, Fezziwig’s Christmas party, and the Cratchits: ‘there were repeated expressions of satisfaction with the happy family of poor Cratchit over their Christmas dinner […] and most heartily over the joyous conclusion of the story, with the […] crowning glory of Tiny Tim’ (Citation1867e, 5). The New York Times warmly agreed, similarly praising the same moments of humour and pathos, and paying tribute to the ‘remarkable and peculiar power’ of Dickens’s incarnation of these characters: ‘Old Scrooge seemed present: every muscle of his face, and every tone of his harsh and domineering voice revealed his character’. The sentiment was no less effective: when it came to Tiny Tim, ‘it was impossible to listen without emotion, and, for very many present, quite impossible to listen without tears’ (Citation1867f, 5). In this iteration of the Carol, informed by Dickens’s presentation of the text, it was the domestic, sentimental and humorous aspects of the story that dominated its reception. Evidently, this helped to cut through what remained of the antagonism that some American audiences still felt towards Dickens. In Philadelphia, the New-York Tribune reported, Dickens was initially ‘received coldly’; stepping onto the stage, Dickens ‘must have felt as if he had stumbled into a bath of ice-cold water’. But A Christmas Carol was simply irresistible: ‘Philadelphia held out as long as she could. The first smile came when Bob Cratchit warmed himself with a candle, but before Scrooge had got through with the first ghost the laughter was universal and uproarious. The Christmas dinner of the Cratchits was a tremendous success’.Footnote1 It was, simply, a ‘triumph’ (Citation1868c, 1).

Undoubtedly the loudest and most effusive reviews of both Dickens’s readings and the renewed significance of A Christmas Carol came from the pen of the pioneering journalist and lecturer Kate Field. Having started working for the New-York Tribune as a theatre reviewer in 1866, she was chosen to cover Dickens’s reading tour in 1867. Her reviews were, as Gary Scharnhorst has put it, ‘celebratory’ (Citation2004a, 161). Field’s account of Dickens’s opening night in Boston, published on the front page of the New-York Tribune on December 3rd, set the tone. It was gushing about Dickens’s performance, giving particularly warm attention to his inaugural American performance of A Christmas Carol (even if, in its enthusiasm, some of the characters’ names were spelled incorrectly):

The most effective reading we ever listened to—it was the most beautifully simple, straightforward, hearty piece of painting from life. Dear Bob Cratchite [sic] made twenty-five hundred friends before he had spoken two words, and if everybody had obeyed the impulse of his heart, and sent him a Christmas goose, he would have been suffocated in a twinkling, under a mountain of poultry. As for the delightful Fizziwigs [sic], not the coldest heart in the audience, but warmed to them at once. Probably never was a ball so thoroughly enjoyed as the one given by these worthy people to their apprentices. The greatest hit of the evening was the point where the dance executed by Mr. and Mrs. Fizziwigs to Miss Fizziwig was described […] This was too much for Boston, and I thought the roof would go off. Next to this, the most effective point, was Tiny Tim, whose plaintive treble, with Bob Cratchite’s way of speaking of him, brought out so many pocket handkerchiefs that it looked as if a snow-storm had somehow got into the hall without tickets. (Field Citation1867a)

Her review of Dickens’s first performance in New York was no less demonstrative about either the man or his festive writings, ranking A Christmas Carol alongside its performance partner Pickwick as the texts in which the ‘key-note of his all writings […] Humanity and humor’ were best represented. She took a moment, too, to effusively praise Carol and its role as the essential Christmas text:

The geniality of the Christmas season has never been so entirely uttered as it is in this little work. The great fires roar in its pages, and bright eyes sparkle, and merry bells ring, and sunlight and starlight and joy wrap it round about it in a delicious atmosphere of honest, ardent goodness. (Field Citation1867b, 4)

Even during her review of Dickens’s second reading in New York, in which he performed extracts from David Copperfield and Pickwick, she took time to praise the previous evening’s interpretations of Bob Cratchit and Scrooge (Field Citation1867c, 4). When Dickens read from Dombey and Son two nights later, Carol was still in her thoughts, and in her favour: ‘our own feeling is that “Bob Cratchit” is a sweeter and healthier piece of pathos […] Bob Cratchit makes the darkness light about us as we hear it read’ (Field Citation1867d, 4). Field distilled these ephemeral reactions into more permanent shape after the conclusion of Dickens’s reading tour with a collection of essays dedicated to each of the texts that Dickens’s performed. The motivation of Pen Photographs of Charles Dickens’s Readings (1868), Field claimed, was ‘the hope of clinching the recollection of Mr. Dickens’s Readings in the minds of many; and, more particularly, of giving to those who have not had the good fortune to hear them, some faint outline of a rare pleasure, the like of which will ne’er come to us again’. Her account of Dickens’s performance of A Christmas Carol opened the book and gave readers a moment-by-moment account of the experience, thus making her reportage a condensed version of the story. Her conclusion was typically fulsome, echoing Thackeray’s famous judgement: ‘There never was a more beautiful sermon than this of “The Christmas Carol”’ (Field Citation1868a, 9).

When Dickens finally set sail for home in April 1868, Harper’s Weekly, which had looked forward to the visit with some trepidation, now wished him bon voyage with a eulogistic poem by F. J. Parmenter in which A Christmas Carol and the poet’s love for ‘him who rings the Christmas Bells with such a glorious peal’ once again took pride of place (25 April Citation1868, 260). The New-York Tribune—presumably, Kate Field—also waved Dickens off fulsomely: his readings had been ‘necessary to disperse every cloud and every doubt, and to place his name undimmed in the silver sunshine of American admiration’. That he had succeeded was largely thanks to A Christmas Carol. He had ended his tour with one final ‘delicious reading’ of the book. Field remained staunch in its praise: ‘What we said at the outset, indeed, remains true at the close – that the key-note of his genius is sounded in the “Christmas Carol” […] the fine lesson of humanity that was once more enforced by its honored teacher’ (New-York Tribune, April 21 Citation1868b, 4).

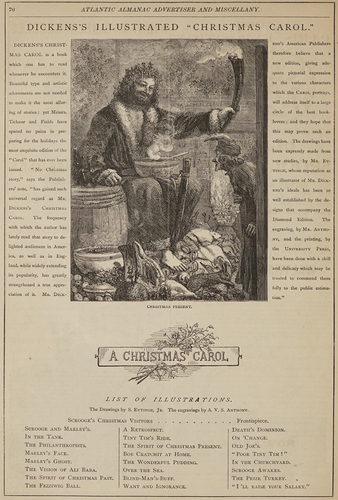

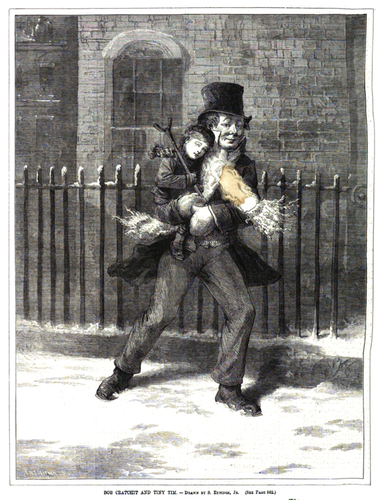

It wasn’t only the prominence of Dickens’s performances and their continued discussion in the popular press that gave A Christmas Carol a renewed American significance throughout the festive season of 1867 and beyond. His visit also spawned a number of publications which vigorously promoted the book as a defining seasonal text. Earlier in 1867, James T. Fields had successfully negotiated with Dickens to make Ticknor and Fields his official American publisher. Now, the firm attempted to capitalise on this arrangement in relation to Dickens’s readings, saturating the market with Christmas volumes (see Moss Citation1981). First, they released A Christmas Carol (bundled together with other Christmas stories and Sketches by Boz) as part of their Diamond Edition of Dickens’s work. These editions featured images by the popular artist Sol Eytinge Jr., who included two illustrations for A Christmas Carol depicting Scrooge and Marley, and Tiny Tim and Bob Cratchit. Then, to accompany Dickens’s readings, Ticknor and Fields also published—with Dickens’s explicit blessing—a souvenir edition of The Readings of Mr. Charles Dickens, as Condensed by Himself. Eytinge’s image of Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim was reused to sit at the beginning of Dickens’s compressed version of A Christmas Carol, and thus served as a frontispiece for the volume as a whole (Citation1868) .

Figure 4. Sol Eytinge’s image of Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim, taken from The Readings of Mr. Charles Dickens, as Condensed by Himself (Citation1868).

In many ways, these texts were both preludes for what came next. Perhaps most significantly of all, Ticknor and Fields prepared a new edition of A Christmas Carol for the 1868 holiday season—also the book’s twenty-fifth anniversary—lushly illustrated throughout by Eytinge with wholly original images. This was evidently a crucial moment for the enshrining of this text at the heart of an American Christmas. An elaborate advertisement shaped reader responses even before the book’s publication, making the link to Dickens’s recent readings explicit:

Dickens’s Christmas Carol is a book which one has to read whenever he encounters it […] The frequency with which the author has lately read that story to delighted audiences in America, as well as in England, while widely extending its popularity, had greatly strengthened a true appreciation of it (Atlantic Almanac, Citation1869, 70).

Figure 5. Advertisement for Ticknor and Fields’ 1868 illustrated edition of A Christmas Carol (Atlantic Almanac, Citation1869, 70).

Figure 6. ‘Scrooge’s Christmas Visitations’: Sol Eytinge Jr. imagines Scrooge meeting all three spirits at once (Dickens Citation1869, frontispiece).

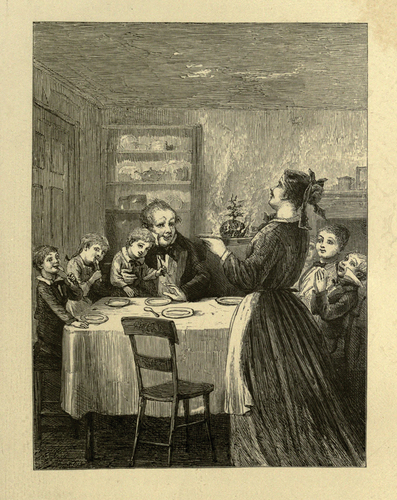

Figure 7. ‘The Wonderful Pudding’: Sol Eytinge Jr. gives visual life to the Cratchit family (Dickens Citation1869, 68).

This landmark moment in America’s relationship to A Christmas Carol—one both clearly rooted in the text but mediated by other factors—was recognised in the press. A reviewer for the Atlantic gave the book, both text and edition, a glowing appraisal. It began with a potent reassertion of the importance of the book: ‘There is not, in all literature, a book more thoroughly saturated with the spirit of its subject than Dickens’s “Christmas Carol”, and there is no book about Christmas that can be counted its peer’. The reviewer also gave a remarkably personal summary of the book’s seasonal appeal that might still hold true for readers today:

As you turn its magical pages, you hear the midnight moaning of the winter wind, the soft rustle of the falling snow, the rattle of the hail on naked branch and window-pane, and the far-off tumult of tempest-smitten seas; but also there comes a vision of snug and cosey rooms, close-curtained from night and storm, wherein the lights burn brightly, and the sound of merry music mingles with the sound of merrier laughter, and all is warmth and kindness and happy content.

Turning to Eytinge’s illustrations, the reviewer was equally quick to praise ‘its beautiful pages’: ‘They show the heartiest possible sympathy with the spirit of the “Christmas Carol”, and a comprehensive and acute perception as well of its scenic ideals as of its character portraits’. In particular, the review praised Eytinge’s visual innovations: his ability to ‘intuitively’ render characters ‘from a mere hint in the story’. In short, the reviewer concluded, with a tacit nationalist implication, Eytinge was ‘the best of the illustrators of Dickens’, as ‘this beautiful Christmas book’ made clear (Atlantic Monthly, December Citation1868a, 763–64). At least according to nineteenth-century man of letters William Winter—who knew both men—Dickens himself apparently agreed, and declared Eytinge ‘to have made the best illustrations for his novels’ (Citation1914, 66). So having rediscovered its seasonal delights during Dickens’s emotional tour a year earlier, America now had its own Christmas Carol. John Greenleaf Whittier certainly thought so, expressing his delight in the edition in a letter to Annie Fields on 17 December 1868: ‘What a charming book it is, outwardly and inwardly! What a benefactor of his race the author is!’ (Pickard Citation1975, 186).

If A Christmas Carol hadn’t fully conquered America in 1843, it certainly had now. In a meditation on Christmas published in the ‘Editor’s Easy Chair’ column in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in the 1868 holiday season, George William Curtis was clear about the renewed significance of both the man and the book for the ongoing meaning of the season in America: ‘A year ago at this time Charles Dickens was trolling his “Christmas Carol” through the country. As we think of it, and of him […] who can help believing with Thackeray that the genius of Dickens has stimulated an immense kindliness of feeling at this happy time? It is the most beautiful and the most precious of all the holidays, and he revived its intrinsic beauty in our minds’ (Citation1869, 419). Yet for all that A Christmas Carol had become an essential part of the American festive season, the years to come would only deepen that connection—while also pushing A Christmas Carol into the centre of some pressing literary debates.

‘The Genius of Christmas is Gone’

If Dickens’s reading tour and its immediate echoes had a profound, if not primary, influence of the place of A Christmas Carol in the seasonal American imagination, his death in June 1870 further cemented that association. Coming so soon after his 1867 tour had rekindled America’s affection for both the author and his Christmas creation, it is perhaps unsurprising that the festive seasons that followed his death would be characterised by his loss. After Dickens’s death, Kate Field swiftly took to the lecture stage to repurpose her time covering his readings—what she described as ‘twenty-five of the most delightful and most instructive evenings of my life’—into ‘An Evening with Dickens’s, a talk that she would give from 1870 until her death in 1896. As Gary Scharnhorst has summarised, throughout the lecture ‘she popularized a hagiographical view of Dickens’ (Citation2004b, 71). She maintained her vocal support for A Christmas Carol, too: ‘Who has done more to make Christmas glorious than any other man?’ she asked her audiences (Scharnhorst Citation2004b, 83).

It was during the Christmas period that followed Dickens’s death that the American tributes truly flooded in. In December 1870, Every Saturday reflected,

The coming of Christmas must bring to many a home in England and this country tender thoughts of Charles Dickens, and recollections of all the wise and beautiful things he wrote touching the season […] Perhaps none of the series of genial Christmas books will be turned to more generally than ‘A Christmas Carol’,—the loveliest and most human sermon ever preached on Christmas (Citation1870a, 862).

Figure 8. Sol Eytinge draws Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim for Every Saturday (December 31 Citation1870, 865).

Yet just as these sometimes heartfelt, sometimes mawkish tributes reached a crescendo, voices of dissent started to emerge. There was a hint of this in Constance Fenimore Woolson’s laudatory short story ‘A Merry Christmas’, published in Harper’s in January 1872. Lamenting the death of Dickens, her characters raise a glass ‘to the genius of Christmas’ and the ‘pure essence’ of the season found in his most famous festive creation—whatever ‘critics might pipe their feeble strain’ (Woolson Citation1872, 233). Increasingly, those critics sounded less feeble. As early as January 1872, taking stock of the Christmas editions of the magazines that year, the Nation was clear that Dickens’s death had already changed the mood of the season and the literary culture surrounding it:

We note that the Scrooge and Marley, Tiny Tim and Bob Cratchit, variety of Christmas makes rather less of a figure […] than it has made in some years. Perhaps the authority and example of its inventor, with his effusiveness of sentiment, were needed to keep in countenance the kind-hearted writers whose milk of human kindness it must have been a somewhat discouraging business to set out in such quantities before the uneffusive American.

Perhaps, then, the recent vogue for A Christmas Carol was just a passing fad inspired by the proximity of its creator, and an intrinsically un-American one at that? To prove their point, they highlighted the ‘cold, cynical’ Christmas story that Frank R. Stockton had just published in Scribner’s (January 4, Citation1872, 13–14).

Indeed, Stockton’s story, ‘Stephen Skarridge’s Christmas’, was clearly a full-blown parody of the Dickens’s style of Christmas story, and of A Christmas Carol specifically. The story opens in a freezing cottage on Christmas Eve; the poverty stricken family of Arthur Tyrrell have little to celebrate, apart from the prospect of a meagre mackerel for their Christmas dinner. Even that pleasure is snatched from them by Stephen Skarridge, ‘the landlord of so many houses in that town’ who travels ‘from house to house, and threatened with expulsion all who did not pay their rents that night’. When the Tyrrells are unable to pay him, Skarridge takes their lowly Christmas mackerel as an interest payment on the overdue rent. But then, as a weary subtitle puts it, ‘What Always Happens’ does indeed happen. The miserly Skarridge is visited by a series of spectral advisers – the mackerel comes to life, and is joined by a cabbage, a fairy, and a giant. Thanks to their perfunctory efforts, his farcical redemption is soon complete, as ‘What Must Occur’ in a story of this kind occurs without fail (Citation1872, 279–87). As The Nation concluded, this was a piece of ‘not wholly unnecessary satire upon the magazine writer’s habitual exaggeration of the sentiment proper to Christmas times’ (January 4, Citation1872, 14). That sense of exhaustion with the template that Dickens had established was compounded by an associated feeling that the literary landscape was swiftly changing, and Dickens was being left behind. Reviewing an American edition of John Forster’s biography of Dickens in, The Galaxy marvelled ‘how far away we are from the Dickens period in literature’. Though it was ‘only a generation since Boz made his appearance’ and ‘hardly yesterday that he was reading his own books to crowded audiences in England and America’, tastes had swiftly moved on to the likes of ‘Turgenef and George Eliot’ who seemed ‘a hundred years’ removed from Dickens. And yet, they concluded wistfully, ‘it is impossible not to wish that we might return to those childish days again, in which […] Scrooge, and all the rest of the company, bad and good, sad and merry, old and young, were our intimate companions. They were very real, whether reality was that of caricature or of high art’ (Citation1873, 569–70).

Figure 9. Stephen Skarridge’s parodic spectral visitors, from Frank R. Stockton’s ‘Stephen Skarridge’s Christmas’ (Scribner’s Monthly, January Citation1872, 281).

Even then, the cultural dividing lines that were growing up around a text like A Christmas Carol were never crystal clear. Mark Twain exemplifies the ambiguities. Twain had gone to see Dickens speak at Steinway Hall on New Year’s Eve 1867—an auspicious evening in his life, because he attended the event with his wife-to-be Olivia Langdon and her family. Still, in his review of the reading for the Alta California, he was quick to tear down the statues that others had erected: ‘Somehow this puissant god seemed to be only a man, after all. How the great do tumble from their high pedestals when we see them in common human flesh’. Twain didn’t witness a reading from A Christmas Carol. But what he saw of David Copperfield certainly didn’t impress him: ‘Mr Dickens’s reading is rather monotonous, as a general thing; his voice is husky; his pathos is only the beautiful pathos of his language—there is no heart, no feeling in it—it is glittering frostwork’. In summary, Twain was ‘a great deal disappointed. The Herald and Tribune critics must have been carried away by their imaginations when they wrote their extravagant praises of it’ (Daily Alta California, Citation1868b, 2). Perhaps he would have been more charmed by Scrooge and company – but perhaps not. Late in life, Twain was equally adamant about his distaste for seasonal literary fare: ‘I hate Xmas stories’, he wrote to a friend (quoted in Wallace Citation1913, 134). In the immediate aftermath of Dickens’s death, Twain also scorned the rise of Dickens hagiography, writing a satirical account of ‘The Approaching Epidemic’ for The Galaxy in September 1870 (with an undoubted swipe at Kate Field, amongst others): ‘One calamity to which the death of Mr. Dickens dooms this country has not awakened the concern to which its gravity entitles it. We refer to the fact that the nation is to be lectured to death and read to death all next winter, by Tom, Dick, and Harry, with poor lamented Dickens for a pretext’ (September Citation1870, 430–31). Yet, Twain was clearly not wholly immune to the charms of A Christmas Carol, and as Howard Baetzhold has noted, however much Twain protested, ‘Dickens continued to occupy an important place in the reading of the whole Clemens family’ (Citation1987, 215). In the winter of 1870, in private at least, Twain seems to have been as susceptible to the renewed enthusiasm for A Christmas Carol as anyone. In December that year, with no apparent irony, he signed off a letter to his friend and correspondent Mary Fairbanks: ‘“God bless us, every one”’ (Fischer, Frank and Salamo Citation[1995] 2007). That same season, he presented the illustrated Sol Eytinge edition of A Christmas Carol to his sister-in-law Susan Crane and her husband Theodore, inscribed in purple ink: ‘Merry Christmas to/Our Sister/signed – Both/Buffalo, 1870’ (Gribben Citation2022, 194).

‘A Hundred Years Hence’

In the years to come, A Christmas Carol inevitably ‘waxed and waned’ in its significance in America. As Davis notes, ‘Some times are more Dickensian in their celebration of Christmas than others’ (Citation1990b, 114). But its essential position in American life was secure almost from its arrival in January 1844. In the late nineteenth century, it had to face an all-out attack from the literary establishment: William Dean Howells made his distaste for Dickens’s Christmas writings a particular plank in his campaign for the promotion of literary realism. By 1887, he was ready to consign the kinds of Christmas literature that Dickens had inspired to ‘the final rag-bag of oblivion’. Looking back over Dickens’s own Christmas work, Howells found it hard to locate the ‘preternatural virtue’ that they once had: ‘The pathos appears false and strained; the humor largely horse-play; the character theatrical; the joviality pumped; the psychology commonplace; the sociology alone funny’. Indeed, according to Howells, Dickens’s ‘creation of holiday literature as we have known it for the last half-century’ was the literary legacy in which his ‘erring force’ could be most felt (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, January Citation1887, 321–25).

Yet, for all that Howells condemned it, A Christmas Carol was safe from oblivion’s rag-bag and remains so to this day. Try as he might, A Christmas Carol was lodged securely in the seasonal affections of Americans. And it is, perhaps, also possible to locate an immediate and powerful literary legacy for this perennial text in the landscape of nineteenth century American literature—within the field of children’s literature. Louisa May Alcott grew up, in Madeleine Stern’s words, with an ‘addiction’ to the works of Dickens, an ‘enthrallment’ that must count as her most significant early literary influence (Stern Citation1987, xvii, xx, xxii). With her sisters, she staged adaptations of his work; as a Civil War nurse, she read to her patients from his novels. So familiar was Alcott with Dickens’s Christmas writings that in December 1863, to raise funds for the Sanitary Commission, she adapted and acted in a number of Scenes from Dickens including extracts from his Christmas books, plus an original prologue: ‘Old Yule & Young Christmas’ (Myerson and Shealy Citation1987, 84–85). When she travelled to London in 1867, after pursuing the echoes of his books around the city, she saw Dickens read at St. James’s Hall—at which moment her ‘idol […] fell with a crash’. In print, she couldn’t mask her disappointment in ‘the red-faced man, with false teeth, and the voice of a worn-out actor’ (Myerson and Shealy Citation1987, 115). Upon his death, Alcott wrote to her family bluntly: ‘dont care a pin’ (Myerson and Shealy Citation1987, 148). Yet her profound immersion in his work is evident, and the timing of her most famous creation and its deep connection to Christmas seems significant. For it was less than a year after Dickens departed America in April 1868, at the precise moment that A Christmas Carol had just been thoroughly revived within American culture, that Jo March first grumbled from the hearth-rug: ‘“Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents”’ (Alcott Citation1868, 7). Just as references to Dickens saturate Little Women, so A Christmas Carol must be assumed as a significant influence on the book’s festive opening, with its emphasis on selflessness and charity. Beth, too, has more than a few of Tiny Tim’s qualities. Perhaps it is little coincidence that Little Women is one of the only nineteenth century books that can stand alongside A Christmas Carol in terms of its longevity and continued renewal in popular culture.

One final, telling example, though perhaps less remembered now, came from the pen of Kate Douglass Wiggin, best known for her children’s classic Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1903). As a child growing up in Maine, Dickens was Wiggin’s ‘hero’: ‘It seems to me that no child nowadays has time to love an author as the children and young people of that generation loved Dickens’ (Citation1912, 6–7). Indeed, Dickens had imbued her world with his creations: ‘Not only had my idol provided me with human friends, to love and laugh and weep over, but he had wrought his genius into things; so that, waking or sleeping, every bunch of holly or mistletoe, every plum pudding was alive; every crutch breathed of Tiny Tim’ (Citation1912, 13). Her ‘poignant anguish’ in 1868 was severe, then, when her mother took her on a trip to Portland to attend one of Dickens’s readings with a cousin—and left little Kate at home for the evening (Citation1912, 10). On the railroad journey home, however, Wiggin had a surprise: Dickens was travelling in the car next to hers. Sneaking into the carriage, she waited until Dickens’s traveling partner and American publisher James Osgood left for the smoking car, and then seized her chance of “snuggling up to Genius” (Citation1912, 22). In the cosy conversation that followed, Wiggin quizzed Dickens whether he cried when he read his stories out loud: ‘We all do in our family. And we never read about Tiny Tim […] on Saturday night, or our eyes are too swollen to go to Sunday school’ (Citation1912, 29). Exactly two decades later, in 1888, Wiggin inspired similar tears when she published The Birds’ Christmas Carol, her first bestseller whose title alone contains a direct and unmissable allusion to Dickens. Its story—in which frail, nine-year-old Carol Bird, born on Christmas Day and not long for this world, attempts to host ‘a grand Christmas dinner’ for the poverty-stricken Ruggles family who live next door—clearly owed a direct debt to Dickens too (Citation1888, 27). As late as 1948, this short novella was still being described as ‘[p]robably the most famous American Christmas tale’ (Roanoke Rapids Daily Chronicle December 24, Citation1948, 24).

Taking stock of Dickens’s reputation in July 1870, pondering whether he would still be read ‘a hundred years hence’, Appletons’ made a remarkable summary judgement that would turn out to be highly prescient. Inevitably, they judged, ‘Literary ideas will greatly change in the future’, and the coming generations would be ‘absorbed in the productions of their own time’. Many of Dickens’s books were likely to fare badly as new ‘distinctive tastes and perceptions’ came to dominate: Pickwick would seem ‘too farcical’, Nicholas Nickleby ‘too romantic’, and most of his other books simply ‘too voluminous’ for future readers with shorter attention spans. Thackeray, in comparison, was doomed by the fact that his ‘brief tales do not adequately represent him’. But Dickens’s reputation was secure, thanks to one particular aspect of his long career:

[A]mong Dickens’s works, there is one series that will probably far outlive the rest of his compositions. We refer to his Christmas books. These brief tales epitomize all the author’s great characteristics—his delicious humor, his unapproachable pathos, his rare fancy, his eccentric conceits. The busiest reader can find the brief time required to peruse these compends of Dickens’s genius, and thus rapidly obtain a full taste of the author’s quality […] Dickens fortunately has, in ‘A Christmas Carol’ […] given us the very essence of his admirable genius.

Of course, Appletons’ concluded, this was merely ‘speculation rather than a prediction’ (July 16, Citation1870, 86). But they could hardly have been more correct. Every year, without fail, while most of Dickens’s books remain unread and unknown, Scrooge, Bob Cratchit, Tiny Tim and all the seasonal spirits return to haunt us again—sometimes in print, sometimes on stage, sometimes on screen, sometimes as Muppets. The roots of the privileged and apparently unshakeable position that A Christmas Carol occupies in the seasonal American psyche, however, lay in the first convulsive, emotional waves of its nineteenth century reception.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thomas Ruys Smith

Thomas Ruys Smith is Professor of American Literature and Culture at the University of East Anglia. He is the author and editor of a number of books including Christmas Past: An Anthology of Seasonal Stories from Nineteenth-Century America (Louisiana State University Press, 2021) and The Last Gift: The Christmas Stories of Mary E. Wilkins Freeman (Louisiana State University Press, 2023).

Notes

1. Though Gary Scharnhorst doesn’t attribute this review to Kate Field, as the paper’s correspondent for Dickens readings it seems likely that she was the author. See Scharnhorst 2004a.

References

- ‘A Christmas Carol in Prose.’ 1844. Magazine for the Million, February 17.

- ‘A Christmas Carol in Prose.’ March 1844a. Southern Literary Messenger.

- ‘A Christmas Carol: Reviews and Literary Notices.’ December 1868. Atlantic Monthly.

- Adams, A. 2011. “Performing Ownership: Dickens, Twain, and Copyright on the Transatlantic Stage.” American Literary Realism 43 (3): 223–241. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerlitereal.43.3.0223.

- Alcott, L. M. 1868. Little Women. Boston: Roberts Brothers.

- Allingham, P. V. 2015. “Changes in Visual Interpretations of A Christmas Carol, 1843-1915: From Realization to Impressionism.” Dickens Studies Annual 46 (1): 71–121. https://doi.org/10.7756/dsa.046.004/71-121.

- Ann Marling, K. 2000. Merry Christmas! Celebrating America’s Greatest Holiday. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Baetzhold, H. G. 1987. “Mark Twain and Dickens: Why the Denial?” Dickens Studies Annual 16:189–219.

- Baker, G. M. January 1871. “Original Dialogue: A Christmas Carol.” Our Boys and Girls.

- Bordelon, D. 2020. “Transatlantic Dickens; Or, Travels Through Nineteenth-Century Book History in America.” Book History 23 (1): 99–129. https://doi.org/10.1353/bh.2020.0003.

- Buddington, Z. B. January 1871. The Voice of Christmas Past. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine.

- ‘Buying Tickets for the Dickens Readings at Steinway Hall.’ 1867a. Harper’s Weekly, December 28.

- ‘Charles Dickens.’ 1867b. Harper’s Weekly, September 7.

- ‘Charles Dickens as He Appears When Reading.’ 1867c. Harper’s Weekly, December 7.

- ‘Charles Dickens Reading.’ 1867d. Harper’s Weekly, December 7.

- Child, L. M. 1846. Letters from New York, Second Series. New York: C. S. Francis & Co. https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.332314.39088005572318.

- ‘Christmas.’ December 1843. Merry’s Museum.

- ‘Christmas Pictures.’ 1870a. Every Saturday, December 31.

- Collins, P. 1993. “The Reception and Status of the Carol.” The Dickensian 89 (431): 170–176.

- Curry, G. 1988. “Charles Dickens and Annie Fields.” Huntington Library Quarterly 51 (1): 1–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/3817302.

- Curtis, G. W. 1869. Editor’s Easy Chair. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February.

- Davis, P. 1990a. The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

- Davis, P. 1990b. “Retelling a Christmas Carol: Text and Culture-Text.” The American Scholar 59 (1): 109–115.

- Davis, R. H. March 1862. “A Story of To-Day.” The Atlantic Monthly, 283–298.

- ‘Death of an Old Actor.’ 1888. The New York Times, January 6.

- ‘Dickens.’ 1867e. The New York Herald, December 10.

- Dickens, C. 1868. “Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim.” In The Readings of Mr. Charles Dickens, as Condensed by Himself. Boston: Ticknor and Fields.

- Dickens, C. 1869. A Christmas Carol in Prose. Boston: Ticknor and Fields.

- ‘Dickens’s Illustrated “Christmas Carol.”’ 1869. The Atlantic Almanac 1869. Boston: James R. Osgood & Co.

- Eytinge, S. 1870. “Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim.” Every Saturday, 865, December 31.

- F.D.H. 1844. Glimpses from a City-Window. The Monthly Religious Magazine, October.

- Field, K. 1867a. Charles Dickens. New-York Tribune, December 3.

- Field, K. 1867b. Charles Dickens: His First Reading in New York. New-York Daily Tribune, December 10.

- Field, K. 1867c. Charles Dickens: His Second Reading. New-York Daily Tribune, December 11.

- Field, K. 1867d. Charles Dickens’s Fourth Reading. New-York Daily Tribune, December 14.

- Field, K. 1868a. Pen Photographs of Charles Dickens’s Readings. Boston: Loring.

- Field, K. 1868b. Mr Dickens’s Farewell Reading. New-York Tribune, April 21.

- Fitzsimons, R. 1970. The Charles Dickens Show: An Account of His Public Readings, 1858-1870. London: Geoffrey Bles.

- ‘From the London Spectator.’ 1844c. Alexandria Gazette and Virginia Advertiser, January 26.

- Goldsbury, J. 1844. The American Common-School Reader and Speaker. Boston: Tappan, Whittemore and Mason.

- Gribben, A. 2022. Mark Twain’s Literary Resources, Vol. Two: A Reconstruction of His Library and Reading. Montgomery, Alabama: New South Books.

- Guida, F. 2000. A Christmas Carol and Its Adaptations. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company.

- Howells, W. D. 1887. ‘Editor’s Study.’ Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, January.

- Hutton, L. 1875. Plays and Players. New York: Hurd and Houghton.

- Ireland, J. N. 1867. Records of the New York Stage, from 1750 to 1860. Vol. 2. New York: T. H. Morrell.

- John, J. 2011. “The Heritage Industry.” In Charles Dickens in Context, edited by S. Ledger and H. Furneaux, 74–80. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511975493.012.

- ‘Literary Notices: A Christmas Carol, in Prose.’ 1844d. The Knickerbocker, March.

- ‘Mark Twain in Washington.’ 1868b. Daily Alta California, February 5.

- McParland, R. 2010. Charles Dickens’s American Audience. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

- Meckier, J. 1990. Innocent Abroad: Charles Dickens’s American Engagements. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky.

- Moss, S. P. 1981. “Charles Dickens and Frederick Chapman’s Agreement with Ticknor and Fields.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 75 (1): 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1086/pbsa.75.1.24302810.

- ‘Mr. Dickens in Philadelphia.’ 1868c. New-York Tribune, January 14.

- ‘Mr. Dickens’s First Reading.’ 1867f. New York Times, December 10.

- ‘Mr. Dickens’s Second Course of Readings.’ 1867g. New York Times, December 17.

- Myerson, J., and D. Shealy, eds. 1987. The Selected Letters of Louisa May Alcott. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Neill, H. 1861. ‘A Reading by Charles Dickens.’ Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, August.

- ‘New Spirit of the Age.’ 1844e. The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science and Art, August.

- Nissenbaum, S. 1997. The Battle for Christmas. New York: Vintage Books.

- ‘Our Weekly Gossip.’ 1842. Brother Jonathan, December 24.

- Parmenter, F. J. 1868. ‘Farewell to Dickens.’ Harper’s Weekly, April 25.

- Pickard John, B., ed. 1975. The Letters of John Greenleaf Whittier, 1861–1892. Vol. 3. Cambridge, Massachussetts: Harvard University Press.

- ‘Reading Yuletide Stories Adds to Family Christmas.’ 1948. Roanoke Rapids Daily Chronicle, December 24.

- Restad, P. L. 1995. Christmas in America: A History. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ‘Reviews: Mind Among the Spindles. January 4 1845b.’ The Broadway Journal.

- Samuel and Olivia Clemens to Mary Mason Fairbanks, Dec 17 1870, Buffalo, N.Y. (UCCL 00551). [1995] 2007. In Mark Twain’s Letters, 1870–1871. Edited by Victor Fischer, Michael B. Frank, and Lin Salamo. Mark Twain Project Online. Berkeley: University of California Press. Accessed September 29 2022. http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/view?docId=letters/UCCL00551.xml;style=letter;brand=mtp.

- ‘Sale of the Dickens Tickets.’ 1867h. Harper’s Weekly, December 28.

- Scharnhorst, G. 2004a. “Kate Field and the New York Tribune.” American Periodicals 14 (2): 158–178. https://doi.org/10.1353/amp.2004.0035.

- Scharnhorst, G. 2004b. “Kate Field’s “An Evening with Charles Dickens”: A Reconstructed Lecture.” Dickens Quarterly 21 (2): 71–89.

- Smith, W. E. 2019. Charles Dickens: A Bibliography of His First American Editions, the Christmas Books and Selected Secondary Works. New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press.

- Stern, M. B. 1987. “Introduction.” In The Selected Letters of Louisa May Alcott, edited by J. Myerson and D. Shealy, 17–42. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Stockton, F. R. 1872. ‘Stephen Skarridge’s Christmas.’ Scribner’s Monthly, January.

- Storey, G., [1999] 2016. The British Academy/The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens M. House, G. Storey and K. M. Tillotson, edited by Vol. 11. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Oxford Scholarly Editions Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780198122951.book.1.

- Storey, G. [2002] 2016. The British Academy/The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens M. House, G. Storey and K. M. Tillotson, edited by Vol. 12. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Oxford Scholarly Editions Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780199245963.book.1.

- Strong, G. T. 1952. The Diary of George Templeton Strong: Post-War Years, 1865-1875, Edited by Allan Nevins and Milton Halsey Thomas. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- ‘Table-Talk.’ 1870c. Appletons’ Journal, July 16.

- ‘Table-Talk.’ 1870d. Appletons’ Journal, December 31.

- ‘The Drama.’ December 28 1844. The Anglo American.

- ‘The Literature of Christmas.’ December 1870. Godey’s Lady’s Book.

- ‘The Life of Charles Dickens.’ April 1873. The Galaxy.

- ‘The Magazines for January.’ January 4 1872. The Nation.

- ‘The Miser at Christmas.’ December 27 1845. Richmond Daily Whig.

- ‘The Theatres on Christmas Evening.’ 1844f. The New York Herald, December 26.

- The Great Dickens Christmas Fair and Holiday Party. Accessed January 16, 2023. https://dickensfair.com/.

- Twain, M. 1870. ‘The Approaching Epidemic.’ The Galaxy, September.

- Wallace, E. 1913. Mark Twain and the Happy Island. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co.

- Wiggin, K. D. 1888. The Birds’ Christmas Carol. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Wiggin, K. D. 1912. A Child’s Journey with Dickens. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Wilkins, W. G. 1911. Dickens in America. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Winter, W. 1914. Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard and Company.

- Woolson, C. F. 1870. ‘Charles Dickens. Christmas, 1870.’ Harper’s Bazar, December 31.

- Woolson, C. F. 1872. ‘A Merry Christmas.’ Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, January.

- Zboray, R. J., and M. S. Zboray. 2006. Everyday Ideas: Socioliterary Experience Among Antebellum New Englanders. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press.