ABSTRACT

This research is a self-as-subject heuristic inquiry, designed to provide in-depth qualitative data on the incorporation of a spiritual dimension into an experiential counseling approach. Training in the UK exposed my emotional block to anger, once hidden in a home culture and a Chinese Christian community. I was stuck in a position where I needed the relational capacity to form a trusting therapeutic relationship for therapy to work and yet did not have that very capacity to trust any therapist. Both Emotion-focused therapy (EFT) procedures and Christian prayer healing contributed to a breakthrough on my work with the emotional block, which fascinated and motivated me to explore the integration of the two. My personal interest in searching for therapeutic change mechanisms led me to find God as an emotion friendly Person who was helping me to become such a person. This paper aims to lend perspectives to therapists who work with clients who have a personal relationship with their God, even if the therapist has a different belief system.

Cette recherche, conçue pour fournir des données qualitatives approfondies sur l’incorporation d’une dimension spirituelle dans une approche de counseling expérientiel, correspond à une investigation heuristique de soi en tant que sujet. Une formation suivie au Royaume-Uni a révélé en moi un noyau émotionnel de colère personnelle, émotion jusque-là réprimée par la culture domestique et la communauté chrétienne chinoise que j’ai connues. J’étais coincé dans la position où j’avais besoin d’une capacité relationnelle pour former une relation thérapeutique de confiance nécessaire à ce que la thérapie fonctionne, alors que je ne disposais pas de cette même capacité de faire confiance à un thérapeute. Les procédures de la Thérapie centrée sur les émotions (EFT) et la guérison par la prière chrétienne ont contribué à une percée dans mon travail avec ce noyau émotionnel, ce qui m’a fasciné et motivé pour explorer l’intégration des deux. Mon intérêt personnel pour la recherche de mécanismes de changement thérapeutique m’a amené à reconnaître Dieu comme étant une personne sensible aux émotions qui m’aidait à devenir une telle personne. Cet article vise à donner des perspectives aux thérapeutes qui travaillent avec des clients qui ont une relation personnelle avec leur Dieu, même si le thérapeute a un système de croyances différent.

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

Diese Forschung ist eine heuristische Untersuchung, wobei der Untersucher das Subjekt der Untersuchung ist. Sie zielt darauf ab, qualitative Tiefendaten zu liefern, was den Einbezug einer spirituellen Dimension in einen Experienziellen Beratungsansatz betrifft. Eine Ausbildung in Grossbritannien machte meine Ärger-Blockade sichtbar, die früher in der heimischen Kultur und in christlicher chinesischer Gemeinschaft verborgen geblieben war. Ich steckte in einer Position fest, die hiess, dass ich die Beziehungsfähigkeit benötigte, um eine vertrauensvolle therapeutische Beziehung in der Therapie aufzubauen um zu arbeiten, und gleichzeitig hatte ich genau diese Fähigkeit nicht, um irgendeiner therapeutischen Fachperson zu vertrauen. Sowohl die Emotionsfokussierte Therapie (EFT)-Vorgehensweisen als auch christliche Heilungsgebete trugen zu einem Durchbruch in meiner Arbeit an der emotionalen Blockade bei. Dies faszinierte und motivierte mich, die Integration dieser beiden Zugangsweisen zu untersuchen. Mein persönliches Forschungsinteresse an therapeutischen Veränderungsmechanismen führte mich dazu, Gott als emotionsfreundliche Person zu finden, der mir hilft, eine solche Person zu werden. Dieser Artikel zielt darauf ab, denjenigen Therapierenden Perspektiven zu geben, die mit Klienten arbeiten, die eine persönliche Beziehung mit ihrem Gott haben, auch wenn die therapierende Fachperson ein anderes Glaubenssystem hat.

RESUMEN

Esta investigación es una indagación heurística del yo como sujeto, diseñada para proporcionar datos cualitativos en profundidad sobre la incorporación de una dimensión espiritual en un enfoque de consejería experiencial. El entrenamiento en el Reino Unido expuso mi bloqueo emocional a la ira, escondida en una cultura hogareña y una comunidad cristiana china. Estaba atrapado en una posición en la que necesitaba la capacidad relacional para formar una relación terapéutica de confianza para que la terapia funcionara y, sin embargo, no tenía esa misma capacidad para confiar en ningún terapeuta. Tanto los procedimientos de la terapia centrada en las emociones (EFT) como la curación por oración cristiana contribuyeron a un gran avance en mi trabajo con el bloqueo emocional, lo que me fascinó y motivó a explorar la integración de los dos. Mi interés personal en buscar mecanismos de cambio terapéutico me llevó a encontrar a Dios como una Persona amiga de las emociones que me estaba ayudando a convertirme en esa persona. Este artículo tiene como objetivo brindar perspectivas a los terapeutas que trabajan con clientes que tienen una relación personal con su Dios, incluso si el terapeuta tiene un sistema de creencias diferente.

Esta investigação é uma reflexão heurística pessoal, destinada a providenciar dados qualitativos profundos acerca da incorporação de uma dimensão espiritual numa abordagem experiencial ao counseling. Fazer formação no Reino Unido expôs o meu bloqueio emocional à raiva outrora ocultada na minha cultura familiar e numa comunidade cristã chinesa. Eu estava preso numa posição onde precisava de capacidade relacional para formar uma relação terapêutica de confiança, para a terapia funcionar. Contudo, eu não tinha essa capacidade para confiar num terapeuta. A cura através quer da terapia focada na emoção (TFE), quer das preces cristãs, contribuiu para uma revolução no meu trabalho com o bloqueio emocional, que me fascinou e me motivou a explorar a integração de ambas. O meu interesse pessoal em procurar mecanismos de mudança terapêutica conduziu-me a encontrar em Deus uma Pessoa apreciadora de emoções e que me estava a ajudar a tornar-me esse tipo de pessoa. Este artigo destina-se a fornecer perspetivas a terapeutas que trabalham com clientes que têm uma relação pessoal com o seu Deus, ainda que o terapeuta tenha um sistema de crenças diferente do seu.

Introduction

Prayer 1

This anxiety had been torturing me often, but I do not understand it. It is so horrible and dark and urgent, and unknown. I want to understand it. I want to be healed by the Lord and I cannot hide my curiosity on how He would make it happen. That is my research. That is my life

(My prayer in my personal journal)

Studying in the UK as an ethnic Chinese, I have experienced tremendous culture shock. I felt that I was lost in vastly different ideologies, struggling to choose between listening to authorities or my own senses in multiple facets of my study life. I felt confused by the debate about ‘being or doing’, ‘relationship or technique’, ‘art or science’ in a non-directive person-centered (PCT) approach (with psychodynamic perspective) training program. I observed clients in Chinese culture drop out from therapy if they did not see themselves being helped quickly, hoping for counselors to be more directive (Zane et al., Citation2004).

As a Christian, I felt that I had lost my voice, perhaps also because I was an actual minority in the UK. I found the pain and loss in the foreign training culture overwhelming to the extent that I almost dropped out from it.

In my desperation to seek help and answers, I took various opportunities for therapy or healing during the training period.

One of them was the Emotion-focused Therapy (EFT) level 1 training in Glasgow. I was struck by the powerful effectiveness of EFT in the skills practice and embraced it instantly. EFT meets my needs as a trainee counselor in the integration of ‘being and doing’, in that the counselor works actively and collaboratively with the client.

Another opportunity came when I joined a Christian inner healing session, where a miraculous restoration of my feelings occurred. I was intrigued by the effectiveness of both EFT and Christian prayer. The first is a subset of human science about people and relationships, rigorously researched, developed and practiced (Greenberg & Goldman, Citation2019), whereas the second is about God’s participation in a person’s life, a mystical dimension in a long human history. I was hoping that putting the two elements together might lead to something phenomenal.

Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT)

Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT) is one of the Person-Centered/Experiential psychotherapy and counseling (PCET) approaches that ‘integrates active process-guiding therapeutic methods derived from Gestalt therapy and focusing within the frame of a person-centred relationship, giving emotion a central role in therapy … ’(Elliott & Greenberg, Citation2016, p. 212). EFT is well researched with evidence of highly promising therapeutic effects (Elliott et al., Citation2018).

EFT theories are based on the belief that emotions are basically adaptive in nature. In fact, the processing speed of emotion is about twice that of cognition (LeDoux, Citation1998). Emotions provide information on what’s happening in our situation and what our needs are and how we can act to meet the need. EFT therapists pay attention to clients’ emotions, use them as compasses to guide the therapeutic work, and aim to work collaboratively to help clients transform maladaptive emotions to adaptive ones (Elliott et al., Citation2004).

Spirituality and psychotherapy

There are vastly different opinions on the definition of religion and spirituality, and these two terms often overlap (Clark, Citation2012; Gubi, Citation2008; Koenig, Citation2018; Loue, Citation2017). Overall, religion is a more structural expression or practice while spirituality connects more to a personal experience.

Spirituality has a Latin root which means breath of life, and it has been expressed as ‘breath’ or life force (Gubi, Citation2008). Walker suggests ‘spirituality means liveliness, vitality, creativity, excitement, excitability, and so on’ (Walker, Citation1971, p. 41). Thorne describes spirituality as a human’s search for meaning, intimacy, and the quality of tenderness (Thorne, Citation2012, p. 119). I adopt a view of spirituality as the person’s perception of their relationship with God (Schreurs, Citation2006), This is in part due to my training as a counselor that was based on studies of human relationships; hence ‘relationship’ is my working vocabulary. I agree with Gubi (Citation2008) to a large extent that spirituality is a natural human process rather than a supernatural one. Additionally, researchers assert that human-human relationships share similar structures with human-divine relationships (Grimes, Citation2007; Schreurs, Citation2006). Therefore, I hope the relational definition of spirituality is natural and accessible for counselors who may not be familiar with it but have expertise in handling human relationships (Schreurs, Citation2006).

I confine my research to mainstream Christian spirituality throughout this writing for the sake of clarity and focus. However, the discussion and discoveries in this research may be relevant to other forms of spirituality.

Prayer as a human experience is as difficult to define as the term spirituality. Gubi (Citation2008, p. 26) lists a variety of descriptions of prayer, such as ‘being in touch with a sense of transcendent inter- (or intra-) connectedness’, or ‘an encounter and communion with God’. Hall and Hall emphasize the conversational nature of prayer: ‘Prayer can be broadly defined as any kind of communion or conversation with God, including focusing attention on God and an experiential awareness of God’ (Hall & Hall, Citation1997, p. 93). They mention two forms of prayer that could be applied in therapy, one of which is inner healing prayer.

Inner healing prayer is described as ‘a form of prayer designed to facilitate the client’s ability to process affectively painful memories through vividly recalling those memories and asking for the presence of Christ (or God) to minister in the midst of this pain’ (Garzon & Burkett, Citation2002, p. 42). It is seen as appropriate in healing memories, such as childhood traumas, that still afflict the client (Tan, Citation2011).

As multiculturalism is increasingly seen as the ‘fourth wave’ in psychology, research and therapy has progressively focused on meeting the needs of religious clients (Aten et al., Citation2012; Clark, Citation2012; Hall & Hall, Citation1997; Koenig, Citation2018; Peteet, Citation2018; Tan, Citation2011).

Hall and Hall (Citation1997, p. 86) conducted a review of literature covering a 20-year time span, concluding that the integration of Christian spirituality and counseling could potentially enhance therapeutic effectiveness as many people believe ‘there is a spiritual reality and that spiritual experiences make a difference in human behavior’. Worthington et al. (1996, as cited in Hall & Hall, Citation1997, p. 96) believe that such integration is more effective than a secular approach in dealing with highy religious clients. Attention was focused upon the ethical application of the integration of spirituality in psychotherapy, to practice with sensitivity to the client’s religious frame of reference, to receive consent from the client and to be aware of the risk of using prayer as a defense or imposing the counselor’s beliefs on the client (Gubi, Citation2008; Tan, Citation2011).

Thorne believes that if Rogers had lived longer he would have included a more ‘mystical and transcendental nature of relationship and … the implications for person-centred therapy of this dimension’ (Thorne, Citation1998, p. 37). Thorne radically raises the idea of embodying the core conditions to the extent of bringing in God himself and pointing to God (Thorne, Citation2002, p. 55). Similarly, West proposes the future of therapy as a spiritual activity (West, Citation2000).

Despite increased awareness of the need to include spirituality with counseling, the significance of spiritual-counseling integration is not fully acknowledged. For instance, only one third of the training programs provided training in spiritual and religious issues while only 23% of faculty members indicated awareness of such needs for training (Schulte et al., 2002, as cited in O’Grady et al., Citation2012).

Moreover, the majority of the existing research literature is on the integration of spirituality with CBT (Tan, Citation2011) or psychodynamic approaches (Grimes, Citation2007). Among existing research, the focus of the investigations is mostly on strategies employed rather than the process of change (Gubi, Citation2008).

EFT itself is an integrative approach which encourages continued integration; for example, Paivio and Pascual-Leone (Citation2010) propose that multi-dimensional resources be included in the treatment of trauma clients (p. 21). EFT practitioners have already improvised inviting God into their counseling rooms, sometimes as the client’s significant other, when they facilitate chair works (personal communication with some EFT counselors). However, there is little research published on those practices.

This research aims to cover the current research gap in the therapeutic process of applying EFT skills and techniques to Christian prayer.

Methodology, data collection and analysis

Prayer 2

I am not alone. Teresa of Avila (Carrera, Citation2005), who was in a less powerful position attempted to share with people her mystical experience. She was humble to consult others while trusting her own senses. I can do the same by speaking/writing them out honestly and be open to inspection, challenge and correction by myself, others and You.’

(My prayer in my personal journal)

This project is a discovery oriented and context sensitive self-as-subject research using Heuristic inquiry. Heuristic inquiry is a ‘form of self-inquiry and dialogue with others aimed at finding the underlying meanings of important human experiences’ (Moustakas, Citation1990, p. 5). Douglass and Moustakas claim ‘the heuristic scientist seeks to discover the nature and meaning of the phenomenon itself and to illuminate it from direct first-person accounts of individuals who have directly encountered the phenomenon in experience’ (ibid, p. 2). It is an experiential and dialogical research method embracing both structure and flexibility, that matches my philosophy as a practitioner and researcher, and is the EFT approach with which I chose to practice.

Practitioner self-as-subject research has an advantage of access to rich, in-depth personal data which are unlikely to be available in normal time-limited interviews, partly due to the longer time dedicated to the research. Additionally, a practitioner-researcher who develops into a higher level of congruence is more likely to produce personal and authentic data during the course of the research. More people embrace those advantages as shown in the trend where more doctorate students tap into the rich internal experience by choosing self-as-subject to generate contextual knowledge (Throne, Citation2019).

There are debates about whether research into self is self-indulgent or biased (Ellis et al., Citation2011). In heuristic inquiry, a researcher’s subjectivity is valued and trusted with a need to strive for integrity, disciplined commitment and creativity (Moustakas, Citation1990; Rennie, Citation2012; Van Manen, Citation2014; West, Citation2009). West (Citation2009) argues that personal bias is inevitable and can be utilized as informed subjectivity. Rennie (Citation2012) proposes that the researcher use reflexivity to enhance the reliability of the research. Throughout the research journey, I have been in dialogue with my internal experience, external reality, theories, and literatures. Therefore, I have been striving to record the research process, including messy hopeless moments, as honestly as possible. Meanwhile, I have been in dialogue with colleagues, friends, and God, being open to critical feedback (refer to Prayer 2).

The data collection lasted for three years and the events presented in this paper covered the first year. My personal journal, audio recordings of prayer, personal therapy reflections, and process notes of professional work are both raw data and analysis in the process. I analyzed the data by reading them repeatedly in order to illuminate and explicate recurring themes, qualities and patterns (Moustakas, Citation1990; Throne, Citation2019).

I found it impossible to bring into focus, the vast amount of data that I accumulated over the period of research. As such, I selected carefully, events from the raw data to further investigate. They are emotionally poignant episodes, that made a significant therapeutic impact that I found theoretically interesting. The events I present in this paper serve as examples or depictions in heuristic research writing.

Results

Events and analysis

Prayer 3

“The dim light that attracted my attention seems brighter. I have found some rough stones during this ‘search’. Lord, please help me in polishing them and letting them sparkle.”

(My prayer in my personal journal)

Event 1: Trouble to feel anger

In the training program, my tutor asked me ‘JM, where are you? You showed care to others, but where are your feelings?’ I was confused: ‘Why would my feelings be important? I am called to be a counselor to care for others, right?’

Other people expressed irritation, anger, or feelings of being threatened when they perceived me ‘being angry’ and yet not showing it. I was numb during the training but found myself trembling in bed at night.

Later, I failed the placement readiness!!!

The feedback given was ‘Match her (my practice partner) anger, volume up!’

What I perceived was ‘Change your personality! Be angry!’

(quote from my personal journal)

In counseling training, my inability to match my practice partner’s anger exposed my underlying fear of anger, or fear of expression of it or dissociation from such an ‘unwanted’ emotion.

Chinese culture values emotional self-control (Jim & Pistrang, Citation2007). I had experienced first-hand from others, higher expectations for women to be gentle. There is a saying in China: ‘Men are not allowed to express any feelings except anger, whereas women are to express any emotion except anger’. When I was young, I was often reprimanded and would be ashamed of myself for being bad-tempered. Subsequently, I was happy to see myself as a mature lady with good temperament who had been ‘slow’ (which I now see as suppressed) to anger. My emotional block was well hidden in my home culture. In addition to living in a culture where my feelings were discouraged, I was brought up in an education system that valued conformity, external locus of evaluation and academic success (Cheng, Citation2011). No one noticed or cared about my emotional inabilities as I was an ‘achiever’ in school.

Church teachings encouraging the suppression of ‘negative feelings’, especially seeing anger as a sinful emotion (Noffke & Hall, Citation2007; Thorne, Citation1991), and calling for denial of ‘body’, ‘flesh’ or ‘self’ (Walker, Citation1971) further contributed to my numbness to certain emotions. The following quotes from a study on Chinese Christian immigrants in the United States reflect my tendency to comply with perceived instructions from God with a denial of my internal locus of evaluation. For example, individuals or couples proclaimed: ‘[We should] practice not to be angry … ’ (Lu et al., Citation2011, p. 132) and ‘This idea cannot emerge into my mind’ (ibid, p. 136)’. It is also common to hear people saying, ‘I will seek God’s will … rather than whether I myself like it or not’ (ibid, p. 142).

The alienation from a person’s emotional self is the alienation from a true, vibrant and creative self, because emotions are an essential part of the self, ‘the primary data of existence’ and ‘an interior sense of ourselves’ (Greenberg, Citation2015, p. 41). As the person’s emotions are necessary tools for one to know the self and others dynamically, blocks to one’s emotions often result in problems in self-self and self-other relationships, such as feeling powerless, meaningless, disconnected and empty (p. 145). These were my feelings. I felt disconnected from both people and God.

People told me that Christianity was not a religion but a relationship with God (Jones, Citation2007; Walker, Citation1971) and spending time with God in devotions would foster this relationship. I was happy to attend or lead bible studies, serve church and people, but I could not sense much connection with Him in my devotions. Gradually, I gave up, blaming myself for being of little faith, and believing that God showed favoritism to others who seemed to have more meaningful and closer relationships with Him.

Part of me was wondering if I was the problem.

Event 2: The ability to feel

In an EFT training session, I was facilitated to discover an ‘emotional block’ in a ‘two-chair’ work. ‘Two-chair’ work can be applied to differentiate different internal selves, e.g. the critical self and the experiencing self, by imagining them in different chairs, subsequently having dialogues between them (Elliott et al., Citation2004). While I was in the inner critic’s chair, I felt the emotions of the experiencing self in the other chair and vice versa. I suspected that my emotions were lagging due to an ‘emotional block’.

Subsequently, in a Christian inner healing session, the prayer minister instructed me to ask Jesus to reveal a vision of the ‘emotional block’. In my vision, the ‘block’ was a cute little girl (about 3–4 years old) with an apologetic smile. She was trying in vain to restore the fence destroyed by a sudden flood (of emotion). The counselor prompted me to submit the ‘emotional block’ to Jesus. I felt attached to the little girl who had been working very hard for me, but I had the sense that she would have a better life with Jesus. I therefore prayed the prayer of submitting her to the Lord’s hand and asking the Lord to help me create a new defense.

In the following week, I was puzzled as I found myself moody over trivial things that I would not notice at all previously. It was a good problem. I was irritated by trivial things, but I was happy that my senses are coming back (quote from my personal journal).

In PCT trainings, a trainee counselor is required to develop self-awareness and relational abilities in order to connect with the client at a relational depth because a counselor uses herself as a therapeutic tool (Mearns & Cooper, Citation2005).

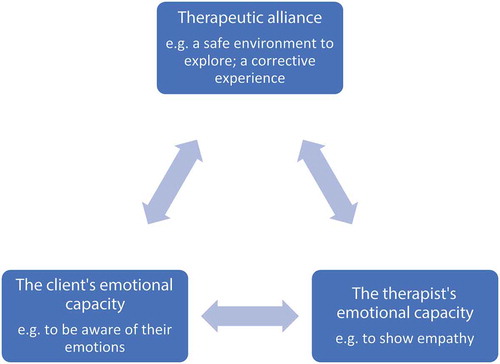

Being numb to my feelings, I was not only limited in my work with clients as a counselor, I also struggled to bond with my own therapist. As shown in , a client has to possess a certain capacity to form a therapeutic alliance for the therapy to work. The client’s emotional ability interrelates to the therapist’s ability to show empathy; the client’s abilities to receive empathy from the therapist and the building of the therapeutic alliance are both necessary conditions in therapy (Greenberg & Watson, Citation2006; Paivio & Pascual-Leone, Citation2010).

EFT researchers have been investigating how a therapist can apply process-directive strategies to raise a client’s ability to access their emotions (Elliott et al., Citation2004; Rice, Citation1992). The two-chair work in this event facilitated my awareness of the emotional block.

In answering my prayer, Jesus had probably conducted an ‘operation’ removing the ‘emotional block’, resulting in my improved emotional ability both psychologically (e.g. being less fearful or judgmental toward my feelings) and biologically (e.g. with restored senses).

Finlay depicts a person’s experience after a cochlear implant to restore her hearing, whereby the person was excited and frightened in a noisy world (Finlay, Citation2009, p. 7). So was I. I was excited as if I entered a new world with renewed senses.

Event 3: The ability to hear

One day, on a bus to my personal therapy, I attended to my stomach churning and asked the felt sense what happened. ‘I am scared,’ my feelings told me, ‘because of the uncertainty of this research.’ I told God my fears, and tears just streamed down. To hide my tears, I had to turn my face to the wall of the bus. After I stopped crying and praying, I waited and asked for God’s responses. I was impatient. Did not really expect Him to respond.

To my surprise, an image came to my mind. An adult who reached out his hands is asking his little girl to jump over a big gap. ‘Jump, don’t be scared, I am here. I will protect you and help you’. The adult looked like Jesus while I was the little girl. My tears streamed down again. This time, joyful and grateful tears.

(quote from my personal journal)

Many people do not expect God to be conversational (Willard, Citation2012). I did not either as He used to speak to me intermittently. In this event, He communicated with me in a conversational way and has been doing so consistently ever since I had this prayer, which I termed as an emotion-focused prayer.

I assume several factors contributed to His changed response style in an emotion-focused prayer. Firstly, turning my attention to my bodily senses and emotions may be one of the factors. As I discussed in Event 1, being in touch with one’s emotions is an essential condition to connect with others; here, to connect with God. Secondly, the genuine expression of my emotions, both verbally and bodily, most likely attracted God’s response according to the functions of emotions. Healthy emotions have adaptive functions; for example, sadness attracts comfort. In this event, the visual image God revealed responded to my deepest fears of uncertainties, needs for assurance, and desires for adventure. Additionally, I also have a sense that the intensity of my vulnerabilities contributed to His timely interaction.

I allowed time and space for Him to reply to my request and for me to receive His answer when I imagined His presence, a procedure similar to imaginal confrontation (IC) (Paivio & Pascual-Leone, Citation2010). Paivio & Pascual-Leone describe IC as a procedure resembling the gestalt-derived empty-chair work (EC) (Greenberg et al., Citation1993). In EC or IC, the client imagines a significant other in an empty chair (or without a chair) and speaks elicited thoughts and feelings facing this imagined person. The client is then supported to imagine being the significant other and expresses the other’s reactions to the client’s thoughts and feelings in a dialogical way when they sit in the significant other’s chair. Using the structural help of a chair and imagination, the client is often able to enter into ‘his or her own shifting perceptions of self, other, and traumatic events’ (Paivio & Pascual-Leone, Citation2010, p. 151). Similarly, in my imagination of God’s presence, my ability to sense the other’s subjectivities, in this case, God’s, was awakened. The reason that I receive His responses quicker may relate to my sharper senses after I submitted my ‘emotional block’ in Event 1. Imagine if someone had their ‘ear blocks’ removed.

Event 3 was a corrective experience with changed perspectives of self and other after I applied EFT techniques to deepen my experiencing and received an empathic response from God. I was deeply touched, not only by the empathic understanding reflected in the content of His response, but also by His warm presence and responsiveness. He is no longer distant or showing favoritism. Rather, He is reaching out to me. I am loved. I am safe.

Event 4: The ability to help my dad connect

In this event, I showed an example of how I applied emotion-focused prayer to help my father be in touch with his emotions before he was able to connect with God and me in an intimate way.

Dad was sick; terminal cancer.

My condition is still the same. I did not get better.

Are you disappointed and frustrated?

Yes.

Can you tell God how you feel? (expressing emotions including negative emotions to God)

(passionately) Lord, I have faith in you. I know you are able to heal me if you are willing.

(being deeply touched) How do you think God would respond to you if He is here? (IC)

He would answer my prayer.

What is his facial expression to you when he is answering your prayer? (IC)

He looks at me in a loving and affectionate way.

(being deeply touched) If he answers your prayer and looks at you in a loving and affectionate way, what is it like for you? (focusing on emotion)

(affectionately) I am very grateful, very grateful. (IC is very effective in arousing emotions with attachment figures for my father here. One of which is God, and the other one is me)

(deeply touched)

…

How have you been recently? (This is extraordinary, my father started to ask about me. I felt being cared for. I had a sense that I lost a large part of my dad and became basically a caregiver to him after my mum’s passing away 16 years ago.)

I have a few essays and reports to complete. It seems quite difficult.

Lord, please help my daughter. May you not lead her into difficulties so that she could complete her studies smoothly, amen.

(quote from my personal journal).

My father hardly talked after his stroke 12 years ago. Before his stroke, he did not express any emotions other than anger. I was amazed that he could express his feelings with God and pour out his heart to Him when his life was nearing the end on earth. He was able to express his affection and care to me as well. When I visited home one month before his last day, he told my sister, ‘JM is coming back. This is the happiest thing.’ He had never been as alive.

Event 5: The ability to show anger to God

Message from my siblings: Dad passed away!

I was shocked and devastated as I could not find a ticket to reach home in time for his funeral.

(angry toward father) Why did you not give me a sign earlier so that I could be with you and attend your funeral? I just called and wished you a happy Father’s Day last Sunday!

How can I be angry at my dad? He did not know when his time was.

(angry toward God) Lord, certainly you knew, you should have been able to arrange a timely trip for me!

I could envision the little girl version of myself crying, screaming inside, kicking and bumping into Him.

A soft voice within me spoke, ‘My child, do you not know that I am sovereign? This is My sovereignty.’

Instantly, my anger dissipated. As I grew in a safer relationship with God, I almost imagined that I was omnipotent. His compassionate response reminded me of His otherness. I have to accept the fact that He is God, not me.

(quote from my personal journal)

I must feel safe enough to show my anger to God. Subsequent to this anger expression to God, I had a few more angry confrontations with Him about healing and suffering; at one of the confrontations I almost renounced my faith.

Applying the experiential techniques was effective in cutting through my defenses. I realized I had swung from over-regulation to under-regulation, a common phenomenon for clients with a trauma history (Paivio & Pascual-Leone, Citation2010). It is commonly acknowledged that techniques must be applied sensitively in safe therapeutic relationships, otherwise the client might be at risk of retraumatization. However, such a safe person is not always available as a client might be triggered outside of a therapy session. Moreover, a therapist may reach their limit in holding a client, especially when they are the target of the intensive anger (Sommerbeck, Citation2015).

In this event, God was there to hold my anger. He manifested His supreme transcendence (Buber, Citation2004, p. 7) and otherness (Benjamin, Citation1990) by surviving my anger at Him and yet not yielding to me. In addition to His competence, He is available 24/7.

It was one of the most helpful therapeutic moments I identified. The non-verbal quality of His speaking soothed me rapidly. His warm presence made me feel deeply accepted and safe. In that moment, I was able to let go of the fear of losing control and not worry about my childish reaction. Greenberg says that the best way for a person to develop emotional self-regulation ability is to be co-regulated by an empathic other in a relational way through right-brain to right-brain learning, which is the same way a child learns emotional skills from a good enough parent. This principle applies to learning other emotional skills such as self-empathy (Greenberg, Citation2015., p. 24). God manifests Himself as a perfect parent and therapist for me – similar but superior to Winnicott’s (Citation1965) good enough mother.

Event 6: The ability to show anger to others

A kick

Reflecting further on my apologetic smile in the image of the little girl and the flood revealed that my father used to blame my mother or us children for his bad mood. I was influenced by the emphasis on filial piety and hierarchical relationships in the Chinese culture even as a child (Sue & Sue, Citation2016). My father was a traditional Chinese man who did not express his emotions except anger. I believed that it was our fault and tried very hard to cheer him up, sometimes by telling jokes.

Scene 1

(trying hard to find a joke, acting like a clown, laughing a little bit uneasily) Hahaha, I almost injured my eyes, hahaha.

(who had lost one eye due to an infection during the war and was taunted by peers as a teenager) Other people laughed at me, and you are laughing at me too! (His face was torn with hurt and he kicked me indignantly).

(frightened, speechless, holding her tears in with disbelief. Later, crying and speaking to herself, ‘You’ve made a mistake. How did you not see that it would cause a misunderstanding? You are not a humorous person. Don’t try it again. You will just mess up’).

I have never told a joke in front of him since then.

Scene 2

In this scene, I observed myself speaking from the different configurations of myself – the inner critic split (Elliott et al., Citation2004; Greenberg et al., Citation1993) in a conversation with my supervisor.

I told a lousy joke. I made a mistake. No wonder he was angry.

But it was not right for him to kick.

(sobbing) I have never blamed him for the kick. I thought I had deserved it. (Fairbairn believes that blaming self is less frightening than accepting an unsafe world but at a price of one’s inner security (Fairbairn, Citation1943)).

He should not kick you. You were trying to help even if it was a mistake.

(felt understood and relieved)

(softening) I was surprised that I lost my voice. I could have told him, ‘Dad, that was not my intention. I was trying to help, not to hurt.’

Of course, you had lost your voice. You were kicked and still under the shock.

(tears streaming down silently) And I was a kid. (the inner child’s voice was able to come out).

Your father was an adult, it was his responsibility to take care of you when you were a kid, not the other way around. You are good. You were a counselor even when you were a kid.

(deeply moved by Tutor L’s words, her generous affirmation was a different experience for me. I had less doubt that I am good).

Scene 3

Another kick

I experienced another kick in the program, my being compassionate to and not fearing of a client was questioned.

I lost my voice. My heart raced, I felt anger rising inside me, I could not speak, I was close to fainting. Finally, I was able to steady my breath and talk.

You can’t tell me how I feel. There is nothing wrong in being compassionate and wanting to help them. A tutor needs to make an effort to understand their students, not to impose their opinions on them.

I was surprised by my change; the little girl’s voice came back. She had grown up. A gentle Chinese lady regained her voice, being congruent and able to express her assertive anger in front of a power figure.

(quote from my personal journal)

This event shows my change in emotion awareness and expression facilitated by the EFT framework.

The faint image of the little girl and the flood that Jesus revealed in Event 2 continued to unfold and pull out hidden memories related to my ‘emotional block’, enabling an important part of therapy in this event: processing implicit emotional memories and reexperiencing the emotional episodes in the presence of a caring other. These are procedures commonly believed to contribute to long-lasting change through the change of the neuro-pathway when emotions are aroused (LeDoux, Citation1998; Paivio & Pascual-Leone, Citation2010). The emotional processing involved an inner critic work (or two-chair work) in Scene 1 and an unfinished business task in the presence of two non-EFT tutors in Scene 2. The process manifested my development in the trust of my own senses and the ability to receive empathy from others in comparison to my condition in Event 1.

According to Elliott et al. (Citation2004), primary adaptive anger is a response to violation, having an action tendency to set boundaries or protect oneself. On the contrary, secondary anger tends to push people away or hide one’s vulnerable feelings. Maladaptive primary anger often links to unfinished business with specific persons or specific events and yet becomes generalized and chronic (p. 259). Dad’s anger was maladaptive as it was attacking the wrong person, at the wrong time and was overly intense, relating to an old wound. Sometimes his anger was instrumental to gain power over my mum. At other times, it could be secondary which masked his needs for co-regulation. Likewise, my anger at God in Event 5 masked a deep sense of loss with a mixture of feelings, such as disappointment that I was not able to attend the funeral, guilt for not being there for him before and after his passing, and grief for the loss of him. It reminded me of my pattern of throwing a temper tantrum to close ones from whom I wish to receive comfort and help with affect regulation (Goldman & Greenberg, Citation2013). Expressing anger is tricky and complex, with a need to integrate ‘the wisdom of bodily feelings with social and cultural know-how’ according to Greenberg (Citation2015, p. 233). It is sad that dad was not able to coach me in healthy ways of anger expression. Not knowing how to express anger in healthy ways was one of the reasons that I blocked it.

However, the ability to express anger to others, and especially to an authority in Scene 3, showed my change. Even though I made numerous mistakes in the learning process and soon experienced more pain, anger and fear in a later stage of my personal therapy, at the same time, I experienced more love, courage and intimacy (Rogers, Citation1990, p. 419), becoming a real person and counselor who contains pain for myself and clients.

Conclusion

Prayer 4

Lord, what is my contribution in this research? I have a desire to help others.

Darling, you are the contribution, you are my most pleased work ☺

(touched, stunned, and then smiled broadly) You are the contribution. I found You! (In my imagination, I jump up and cling on his shoulder).

(My prayer in my personal journal)

I have attempted a self-as-subject heuristic inquiry, to explore how prayer incorporated with EFT techniques, impacted my personal development as a Chinese Christian counselor, helped me to overcome an emotional block, and become more emotion-friendly.

The process of my personal healing shows the effectiveness of EFT techniques in promoting emotional connection with self, others, and God. Additionally, experiential counseling techniques that provide structural support to a person’s experiencing can help a counselor grow to be process experts to better help their clients.

Meanwhile, the evocative nature of the experiential techniques imposes higher requirements on a counselor’s ability to maintain a safe therapeutic relationship. In this study my relationship with God was shown to provide a possible corrective experience and a secure base; including God in EFT therapy could potentially enhance therapeutic safety.

Moreover, the spiritual dimension may be a valuable (sometimes essential) resource for clients who have difficulty forming an alliance, by potentially aiding in regulating emotions and recalling trauma memories. It is shown that the presence of God can be natural in the emotion healing process, for example, by being a soothing object to co-regulate my overwhelming emotions (Event 5). He can be supernatural too, for example, by revealing images linked to my implicit memories and restoring my senses (Event 2, 6).

My curiosity about the mechanisms of the therapeutic impact of both EFT and prayer, led me to find God as an emotion-friendly Person, who is helping me in my journey of becoming such a person. Perhaps these two approaches are compatible because PCT is a therapy of agape love (Kahn, Citation1999) and many Christians believe God is the embodiment of such love (Lewis, Citation2010; Thorne, Citation2002).

Findings indicate that:

One’s emotion is an essential tool to know one’s self and develop intimate relationships with others (including God).

The application of experiential techniques in a safe relationship with God facilitates the client to overcome defense mechanisms to connect with their emotional being.

The spiritual dimension may be a client’s resource to enhance healing emotions.

The spiritual dimension may be a therapist’s resource especially in personal development.

The exploratory research may lend perspective to therapists who work with spiritual clients even if the therapist has a different belief system. It may also lend perspective to counseling training, and counselors’ personal development, especially for counselors who have some form of spirituality in their lives. My purpose is to ‘throw a stone to attract a jade’ (a Chinese idiom), hoping this work will potentially stimulate research interest in ethical and effective application of spirituality in PCET practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Junmei Wan

Before I came to study in Edinburgh in 2016, I worked as a school counselor, social worker, a training company director and a research scientist, while my interest shifted from the fascinating physical world to the mysterious beautiful human psych.

References

- Aten, J. D., O’Grady, K. A., & Worthington, E. L. (2012). The psychology of religion and spirituality for clinicians using research in your practice. Routledge.

- Benjamin, J. (1990). An outline of intersubjectivity: The development of recognition. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 7(SUPPL), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1037//0736-9735.7.Suppl.33

- Buber, M. (2004). I and thou. Continuum.

- Carrera, E. (2005). European humanities research centre. Teresa of Avila’s Autobiography : Authority, power and the self in mid-sixteenth-century. Legenda.

- Cheng, K. M. (2011). Pedagogy: East and west, then and now. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(5), 591–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2011.617836

- Clark, M. (2012). Understanding religion and spirituality in clinical practice. Karnac Books.

- Elliott, R., & Greenberg, L. S. (2016). Emotion-focused therapy. In C. Lago & D. Charura (Eds.), The person-centred counselling and psychotherapy handbook : Origins, developments, and current applications (pp. 212–222). Open University Press.

- Elliott, R., Bohart, A. C., Watson, J. C., & Murphy, D. (2018). Therapist empathy and client outcome: An updated meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000175

- Elliott, R., Watson, J. C., Goldman, R., & Greenberg, L. S. (2004). Learning emotion-focused therapy : The process-experiential approach to change. American Psychological Association.

- Ellis, C., Adams, T. E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 36 (4), 273–290. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/stable/23032294

- Fairbairn, W. R. D. (1943). The repression and the return of bad objects (with special reference to the ’War Neuroses’). British Journal of Medical Psychology, 19(3–4), 327–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1943.tb00328.x

- Finlay, L. (2009). Ambiguous encounters: A relational approach to phenomenological research. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 9(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/20797222.2009.11433983

- Garzon, F., & Burkett, L. (2002). Healing of memories: Models, research, future directions. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 21(1), 42–49. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ccfs_fac_pubs/37

- Goldman, R. N., & Greenberg, L. (2013). Working with identity and self-soothing in emotion-focused therapy for couples. Family Process, 52(1), 62–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12021

- Greenberg, L. S. (2015). Emotion-focused therapy: Coaching clients to work through their feelings (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association.

- Greenberg, L. S., & Goldman, R. N. (Eds.). (2019). Clinical handbook of emotion focused therapy. American Psychological Association.

- Greenberg, L. S., Rice, L. N., & Elliott, R. (1993). Facilitating emotional change : The moment-by-moment process. Guilford Press.

- Greenberg, L. S., & Watson, J. C. (2006). Emotion-focused therapy for depression. American Psychological Association.

- Grimes, C. (2007). Chapter 2. God image research. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 9(3/4), 11–32. https://doi.org/10.1300/J515v09n03

- Gubi, P. M. (2008). Prayer in counselling and psychotherapy exploring a hidden meaningful dimension. Jessica Kingsley Publisher.

- Hall, M. E. L., & Hall, T. W. (1997). Integration in the therapy room: An overview of the literature. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 25(1), 86–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164719702500109

- Jim, J., & Pistrang, N. (2007). Culture and the therapeutic relationship: Perspectives from Chinese clients. Psychotherapy Research, 17(4), 461–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300600812775

- Jones, J. W. (2007). Psychodynamic theories of the evolution of the God image. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 9(3–4), 33–55. https://doi.org/10.1300/J515v09n03

- Kahn, M. (1999). Between Therapist and Client: The New Relationship. Freeman.

- Koenig, H. G. (2018). Religion and mental health : Research and clinical applications. Academic Press.

- LeDoux, J. E. (1998). The emotional brain : The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Lewis, C. S. (2010). The four loves. HarperCollins.

- Loue, S. (2017). Handbook of religion and spirituality in social work practice and research. Springer.

- Lu, Y., Marks, L., & Baumgartner, J. (2011). “The compass of our life”: A qualitative study of marriage and faith among Chinese immigrants. Marriage and Family Review, 47(3), 125–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2011.571633

- Mearns, D., & Cooper, M. (2005). Working at relational depth in counselling and psychotherapy. Sage.

- Moustakas, C. (1990). Heuristic research: Design, methodology, and applications. Sage.

- Noffke, J. L., & Hall, T. W. (2007). Attachment psychotherapy and God image. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 9(3/4), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1300/J515v09n03

- O’Grady, K. A., Worthington, E. L., & Aten, J. D. (2012). Bridging the gap between research and practice in the psychology of religion and spirituality. In K. A. O’Grady, E. L. Worthington, & J. D. Aten (Eds.), The psychology of religion and spirituality for clinicians: using research in your practice (pp. 387–396). Routledge.

- Paivio, S. C., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2010). Emotion-focused therapy for complex trauma : An integrative approach. American Psychological Association.

- Peteet, J. (2018). A fourth wave of psychotherapies: Moving beyond recovery toward well-being. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 26(2), 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000155

- Rennie, D. L. (2012). Qualitative research as methodical hermeneutics. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029250

- Rice, L. N. (1992). From Naturalistic Observation of Psychotherapy. In S. G. Toukmanian & D. L. Rennie (Eds.), Psychotherapy process research : Paradigmatic and narrative approaches (pp. 1–21). Sage.

- Rogers, C. R. (1990). The Carl Rogers reader. (H. Kirschenbaum & V. L. Henderson, eds.). Constable.

- Schreurs, A. (2006). Spiritual relationships as an analytical instrument in psychotherapy with religious patients. Philosophy, Psychiatry & Psychology : PPP, 13(3), 185–196,260. https://doi.org/10.1353/ppp.2007.0022

- Sommerbeck, L. (2015). Therapist limits in person-centred therapy. PCCS Books.

- Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2016). Counseling the culturally diverse : Theory and practice. Wiley.

- Tan, S.-Y. (2011). Counselling and psychotherapy A Christian perspective. Baker Academic.

- Thorne, B. (1991). Person-centred counselling : Therapeutic and spiritual dimensions. Whurr.

- Thorne, B. (1998). Person-centred counselling and Christian spirituality. Whurr.

- Thorne, B. (2002). The mystical power of person-centred therapy : Hope beyond despair. Whurr.

- Thorne, B. (2012). Counselling and spiritual accompaniment: Bridging faith and person-centred therapy. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137370433

- Throne, R. (2019). Autoethnography and heuristic inquiry for doctoral-level researchers : Emerging research and opportunities. IGI Global.

- Van Manen, M. (2014). Phenomenology of practice. Left Coast Press.

- Walker, J. L. (1971). Body and soul : Gestalt therapy and religious experience. Abingdon.

- West, W. (2000). Psychotherapy and spirituality crossing the line between therapy and religion. Sage.

- West, W. (2009). Situating the researcher in qualitative psychotherapy research around spirituality. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 22(2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070903171934

- Willard, D. (2012). Hearing God: Developing a conversational relationship with God. VP Books.

- Winnicott, D. W. (1965). The maturational processes and the facilitating environment. Hogarth Press.

- Zane, N., Hall, G. C. N., Sue, S., Young, K., & Nunex, J. (2004). Research on psychotherapy with culturally diverse populations. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5th ed., pp. 767–804). Wiley.