ABSTRACT

This study describes the current state of qualitative psychology and gives an overview of the philosophical paradigms used in English language qualitative psychology studies from the post-socialist countries of Central Eastern Europe. For political and historical reasons, academic life of this area is unique, providing a special field for investigation. This study explored the following research questions: Which philosophical paradigms are used in qualitative psychology? What kind of methods are applied? What kind of fields in psychology are examined? Thirty-five articles were analysed from five countries. Articles were examined through their paradigmatic considerations, using a dichotomous qualitative quasi-testing to distinguish positivist/postpositivist from interpretive/constructivist paradigms. We examined the methodology and content of various articles and analysed the keywords to explore common themes of interest. A dominant constructivist philosophical approach was present. Pure positivist articles were found to be quite rare, but mixed paradigms seemed to be frequent. Most of the methodologies were not specified. In terms of interest, the most commonly examined field was found to be social psychology. In the postsocialist era, mixed paradigms were conspicuous since culture and tradition might have had a significant effect on ontology, epistemology, and knowledge of the researcher.

Introduction

Rationale

The aim of this study was to assess the status of qualitative psychology in the academic life of Central-Eastern Europe. The common political and historical background of these countries made the evaluation of academic life in Central-Eastern European different from the one of the “Western World”1 (Tímár Citation2004; Stenning & Hörschelmann Citation2008), thereby providing a special field for investigation. This study aims for a comprehensive understanding of the modern trends of qualitative psychology in Central-Eastern Europe. We examined five countries of the area with the most similar socio-cultural background among Central-Eastern European countries. They gained their scientific foundation under the successful educational system of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy (Buklijas & Lafferton Citation2007) and later under the influence of the Soviet Union.

Our particular focus was on the presence and state of psychological qualitative research in the scientific life of five Central-Eastern European postsocialist countries (Hungary, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Poland, and Romania). Our aim was to analyse the current articles, which were written after the countries had joined the European Union (Hungary, Poland, Czeck Republic, and Slovakia in 2004; Romania in 2007), since the Europeanization might have had effects on the scientific trends. We focused on the paradigmatic considerations under which studies are completed. As we had not yet found any regional surveys on this field, we aimed to provide support for such research in psychology.

Psychology in Central-Eastern Europe

After World War II, during communist and socialist periods, the selected countries were under the influence of the Soviet Union. The Communist regime was efficient in maintaining control over the collective memory and social discourse (Gille Citation2010). Academic life became a target of the ideological clearings and the “bolshevization” of science, which meant the subordination and prohibition of “Western” psychology (Szokolszky Citation2016; Kovai 2016). This led to the prohibition of psychoanalysis, the Gestalt approach in psychology (Wertz Citation2014). Instead of following Western science, a so-called “pavlovization” took place based on the theories of the famous Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov. This led to the medicalization of psychology, which actually saved it from becoming the part of the ideological movement. Other less clinical medical fields of psychology were prohibited. In the 1960s, the political regime weakened and psychology became “tolerated” (Szokolszky Citation2016). In 1967, the Transnational Committee established the first conference in Vienna where Eastern and Western social scientists could meet. However, the discussion of philosophical and ideological considerations was excluded from the meetings (Moscovici & Marková Citation2006). In 1968, the crisis in Prague and later the student revolution at many Western European and American universities challenged the cooperation of the two “worlds.” Socialist countries were excluded from the ballooning internationalization of Western psychology (Danziger Citation2006).

The change of regime in 1989 caused a political and economic shift in Central-Eastern Europe. It resulted in a complex situation in the context of the contracting world economy. Because of the rapid change of ideologies, politics, economics, and society, this area became a special laboratory for social (Schwarts, Bardi & Bianchi 2000), economic, and political investigations (Stanilov Citation2007). However, politicians of the fallen regime managed to transform their political influence into economic values, enabling them to keep their influence and power in the new system. Ex-communist professionals were kept in politics because there was no one to replace them (Bunce & Csanádi 2015). The singularity is caused by the peculiarities of the fallen regime, with politics having effects on family norms and individual preferences (Robila & Krishnakumar Citation2004) as well as values and priorities (Schwarts, Bardi & Bianchi 2000), leading to a long-standing change that affected forthcoming generations (Alesina & Fuchs-Schündeln Citation2007). This influence had a deep-rooted effect on the concept of trust and honesty (Rose-Ackerman Citation2001), thus establishing a political-geographical-social postsocialist condition (Gille Citation2010). As psychology science and practice were considered suspicious in the eyes of the regime, psychology had a different history, traditions, and evaluation than its “Western” counterpart.

Qualitative research trends

Qualitative research has received much more attention in the past 25 years (Rennie, Watson & Monteiro Citation2000). Numerous studies have been implemented to monitor trends in qualitative methods (e.g., Sexton Citation1996; Ponterotto Citation2010; O’Neill Citation2002). These studies claimed to detect an increasing presence of qualitative psychology research, especially in the fields of counseling (Berríos & Lucca Citation2006) and health psychology (Davidsen Citation2013), albeit the increasing qualitative interest is present in most psychological fields (Stainton-Rogers & Willig 2017).

Qualitative psychological studies are based on different philosophical approaches of reality and epistemology (Guba & Lincoln Citation1994, Citation1982). This results in diverse methodological choices and even multiple variations of a single method. In other words, there are no “standard methods.” Different methods and approaches might lead to several interpretations and diverse knowledge (Gale Citation1993). For this reason, Morrow (Citation2005) emphasizes the importance of self-reflexivity and indicates the necessity of the researchers’ ability to explain the used paradigms clearly, in addition to making the research transparent (Morrow & Smith Citation2000).

Transparency means the clear explanation of the study’s purpose (Morrow Citation2005; Guba & Lincoln Citation1994), goals, methods, and procedures (Elliott, Fischer & Rennie Citation1999). These are embedded in the researcher’s perspective and basic belief system (Gehart, Ratliff & Lyle Citation2001). These beliefs might be presented in a philosophical frame alias paradigmatic knowledge (Morrow Citation2005; Guba & Lincoln Citation1994; Gehart, Ratliff & Lyle Citation2001; Ponterotto Citation2005). In some qualitative studies, transparency might be missing, leading to the distortion of the results (Ponterotto Citation2010). Therefore, paradigms are established to gain some standards to help make qualitative research easy to evaluate (Guba & Lincoln Citation1989).

Qualitative psychology in Europe

Marecek et al. (Citation1997) state that qualitative research blossomed in Europe as European psychologists became more familiar with philosophies that supported new methodologies (Wertz Citation2014). However, qualitative research is still considered to be secondary in psychological research in Europe (Symon & Cassel 2016). The author’s representation of Europe seems to be based on Western European countries, such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and France. Other parts of Europe, such as Central-Eastern Europe, received little attention. Steps were made to improve the usage of qualitative methods; for example, the Centre for Qualitative Psychology was founded in 1999 in Tubingen, Germany, and held an annual meeting in Europe and in Israel. Some articles (Angermüller Citation2005; Konecki Citation2005; Bruni & Gobo Citation2005) were written (mainly on sociology) on comparing European and American qualitative research, but they focused only on Western European countries. Wretz (Citation2014) considered qualitative psychology as causing the reblossoming of humanistic psychology, which had deep roots in Europe.

According to previous findings, common topics of qualitative research in the “Western World”1 are social issues, gender, ethnicity (Marchel & Owens Citation2007), and sexual identity (Peel, Clarke & Drescher Citation2007). Common fields include education, cultural psychology (Swartz & Rohleder Citation2017), counseling (Marchel & Owens Citation2007), and drug abuse (Olsen et al. Citation2015). However, qualitative studies seem to appear in every field of psychology (Stainton-Rogers & Willig 2017).

Paradigm shift, blurring paradigms

Leading researchers categorize qualitative studies into four main philosophical paradigms: positivism, postpositivism, critical theory, and constructivism (Guba & Lincoln Citation1994; Lincoln, Lynham & Guba Citation2011; Patton Citation2002; Rossman & Rallis Citation2003; Gehart, Ratliff & Lyle Citation2001), supplemented with their combinations (Ponterotto, Park-Taylor & Chen Citation2017). The characteristics of the four paradigms, according to Guba and Lincoln (1984), are 1) The positivist paradigm is mainly used in hard science; it is focused on the examination of one objective reality, uses deductive, manipulative, and mainly quantitative methods. 2) Postpositivism states there is one “real” reality, but it is imperfectly understood. It is objectivist and the methodology concentrates on hypothesis falsification. 3) Critical theory states virtual reality is influenced and shaped by social, cultural, political, economic, ethnic, and gender evaluations, so subjective interpretations can be examined. 4) Constructionism claims reality is constructed due to local, individual and specific influences and contexts, and thus parallel realities might exist. It focuses on subjective interpretations.

Ponterotto (Citation2005) claims simultaneous usage of different paradigms might occur in one study. He primarily examined international journals (mainly North American) and found that positivism continued to be the primary concept in psychological research, although the prevalence of constructionist views had been increasing since 1995. Between 2013 and 2015, an increase was detected in the number of constructivist/interpretivist studies (Ponterotto, Park-Taylor & Chen Citation2017).

Having considered the theoretical background and fields of qualitative research, we reached three explorative research questions:

Which philosophical paradigms are used dominantly in psychological research in Central-Eastern Europe?

Which methods are frequently used and under what considerations?

Which fields of psychology are usually examined with qualitative approaches?

Methods

Data collection

The selection criteria of the articles were that one of the authors had to belong to one of the universities of the above-mentioned countries (e.g., Krahé et al. 2015). First-authorship was not obligatory. Studies available on scientific databases were not categorized by the universities, countries, or nationalities of the authors. This led us to three data collection methods:

We searched the EBSCO host, ResearchGate, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. We searched by country name or author nationality and used some of the keywords used by Rennie, Watson and Monteiro (Citation2002). These were “qualitative” “qualitative psychology” “qualitative analysis,” “qualitative research,” “phenomenology,” “discursive psychology,” “content analysis,” and “case study.” Thirty-nine articles were found this way.

On SCImago Journal, we searched for English-language psychological journals of the above-mentioned countries publishing qualitative articles of national authors: the Slovakian Studia Psychologica, the Polish Psychological Bulletin, the Romanian Journal of Applied Psychology, the Czech Cyberpsychology, and the Hungarian European Journal of Mental Health. As most of the journals were operating on an international-level, it was difficult to find articles for our goals. In some cases we found psychology journals such as Ceskoslovaka psycholigie, but we could not reach whole texts of English language articles. Twenty-five national qualitative articles were found that met the inclusion criteria.

We collected the e-mail addresses of all psychology institutions, associations, and universities in the target geographic area based on the list of psychology-resources.org. We sent 46 e-mails asking for information about qualitative education, research, and publications. We received 16 answers with 18 articles and 8 lists of publications.

The study included 82 English language articles in total from which we analyzed 35, the most current 7 by each country. The earliest article was published in 2005 and the most recent one in 2018. The smallest number of articles (seven) was found in the group of Romanian qualitative researchers. To have a balanced sample, the seven most recent articles from each country were analyzed.

Data analysis

This study is not a meta-analysis since it is not collecting and reanalysing the relevant empirical literature. Neither could our research be called a systematic review because we did not want to collect evidence to answer a research question. Our research focused on the manifest content of texts: their philosophical considerations. That is why we created the phrase “paradigm analysis,” similarly to Chandler’s paradigmatic analysis in linguistics (1994).

Deductive content analysis — first research question

A theory-driven deductive content analysis was carried out (Elo & Kyngäs Citation2008; Hsieh & Shannon Citation2005). Due to clarity and simplicity issues, the categories of our content analysis were based on a two-paradigm system introduced by Petty, Thomson and Stew (2012, p. 269). In this system, the two main paradigms are positivism/postpositivism and interpretivism/constructivism. We added the category of modes of representation and type of research phenomenon from Harré's (Citation2004) distinction between the philosophical perspectives of natural science and human science. The deductive content analysis was based on our criteria system with opposing aspects. The coding system is presented in .

Table 1. Deductive paradigm analysis of the examined articles.

The coding process was the following: The first author read the articles and took notes on the description and usage of the qualitative approach. Then the second and third authors tested the categorization. Discrepancies were discussed and a consensus was reached. We classified the articles into the following five categories: 1) interpretivist/constructivist, 2) positivist/postpositivist (mixed methods, quantifying qualitative approach), 3) mixed paradigms with postpositivist dominance, 4) mixed paradigms with constructionist dominance, and 5) cannot be clearly identified.

We classified the articles by the detachment between the first and second broad categories first. Then according to the complexity of previously used paradigms, we created the third, fourth, and fifth dimensions. We divided the articles into the most suitable categories, with the sensibility to the dominantly used paradigms (third and fourth categories). Those which used elements and considerations simultaneously from both paradigms more than two times or were problematic to be categorized were put into the fifth “cannot be clearly identified” category. On some occasions, it was difficult to categorize an article because little information was given about the data analysis (e.g., Adamczyk Citation2016). In these instances, we used the context to form conclusions as they seemed to use a kind of content analysis, but research questions were hypotheses. There was no reflection on whether the research used inductive or deductive coding systems. In such cases, we put a question mark in the categorization table. This way we found more than three problematic categories, so we put the questionable article into the fifth category (cannot be classified).

Analysis of methods — second research question

Cited methodologies and references were collected from the articles following the research method of Marchel and Owens (Citation2007). We put them into inductive categories according to which method was stated to be used in the study. depicts some examples from the reviewed articles which led us to the conclusion of categorizations.

Table 2. Examples for the usage of our deductive paradigm analysis table.

Content analysis — third research question

The third focus of our study was to explore the topics of the examined articles. We collected the keywords of the articles or used the words of the title. A simple form of content analysis (Neuendorf Citation2016; Elo & Kyngäs Citation2008) had been carried out on the collected words to order them in higher categories according to their scientific fields within psychology. This way we included subcategories. When all the keywords were put into subcategories, we systematized them and divided them into supra categories.

Results

Our first step was to analyze the underlying paradigmatic considerations, focusing on the frequencies of the different aspects. depicts the density of our previously defined subcategories in the articles and differentiates the positivist/postpositivist and the interpretive/constructivist aspects used.

Table 3. Frequencies of the different paradigmatic aspects used in the articles.

Our findings show that 80% of the articles shared the concept of multiple realities, which is the basis of the interpretivist/constructionalist view. Strong constructivist dominance appeared in the aspects of the researchers’ activity (71%), participants’ activity (85,71%), undefined and noncontrolled variables (65,61%), and discursive representation (74,29%).

According to our results, generalization was the most commonly used postpositivist aspect, which suggests that even the authors of these qualitative researchers try to generalize their results. Interestingly, the category where both considerations reached relatively high frequency was the method of coding. Deductive 4 (11,43%) and inductive 19 (54,29%) coding systems seemed to be used. In 11 articles both theory-driven and data-driven research appeared to be used simultaneously. In some cases interviews and the coding process followed some theories, or inductive coding was completed with the coding system of a handbook (Ghorghe & Liao 2012). In such cases, research questions coming from a theoretical standpoint might have an effect on the coding process and the results. The barrier between theory influenced coding process and the inductive coding was ambiguous.

Among Czech and Polish articles we found interpretive/constructive paradigmatic considerations (five Czech and three Polish articles), while “cannot be identified” articles were the most common among the Romanian (four), Slovakian and Hungarian articles examined (three, three). All in one presence of the used paradigms are depicted in .

Table 4. Number of used paradigms of the articles by country (n=35).

Table 5. Frequencies of the paradigms used (n=35)

Most of the articles could not be clearly classified into the first four clusters because of the lack of description provided or the opposing paradigmatic aspects they used simultaneously. Constructivist dominance appeared among the studies analyzed (11). However, clearly positivist articles were found to be rare (two). Mixed paradigms seemed to be frequent (10).

Twelve articles were put in the fifth category because they used simultaneously the postpositivist and the interpretive considerations or not enough information was given for the categorization. The interpretivist/constructivist paradigm seemed to be used in almost one-third of the articles examined, and two used a dominantly interpretivist paradigm. Postpositivist was the least frequently used. We found two pure postpositivist articles and two dominantly postpositivist ones.

Our second research goal was to analyze the frequency of the different methods used in the articles. shows the distribution of the methods.

Twenty-two percent of the article's accurate methodology was unspecified. These articles did not name or cite their applied methods. The second most popular choices were content analysis, thematic analysis, and methods, which were said to be based on grounded theory.

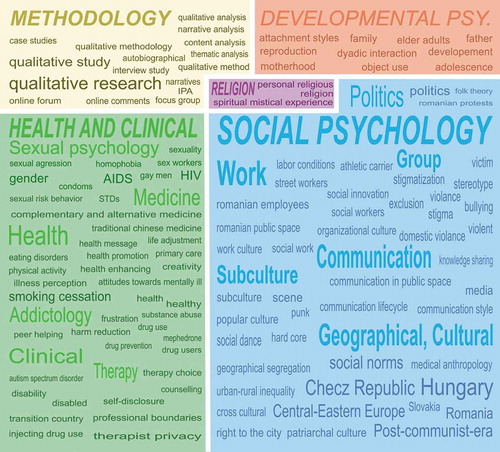

Our third goal was to detect the fields of qualitative research in Central-Eastern Europe. The categorization of the keywords of the articles is depicted in .

Five categories emerged in the analysis of the keywords. The titles are written in capital italics, and subtitles are written in bold with a capital initial letter.

The keywords are presented in simple letters, and the sizes of them represent their frequencies. represents the prevalence of each of the five categories. They were social psychology (42,95%), health and clinical psychology (31,54%), methodology (16,1%), developmental psychology (7,38%) and religion (2,01%).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess qualitative psychology in Central-Eastern Europe. We analysed the paradigms, the methods, and the fields of 35 qualitative research articles of five countries: the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia. Our findings show constructivist/interpretivist considerations seem to be dominant among the analyzed qualitative articles. In our study, postpositivist elements, such as generalization and deductive coding, also occurred. We found a substantial presence of paradigmatic eclecticism and confusion with the simultaneous usage of both constructivist/interpretivist and postpositivist considerations. According to the methodological analysis of the 35 articles, unspecified methods are used most frequently. Moreover, methodological descriptions were laconic and not detailed.

The content analysis of the keywords presented that the most commonly examined field is social psychology, which is in line with previous studies (Stainton-Rogers & Willig Citation2017). In the brief literature of qualitative research paradigms, counseling journals are analyzed by Ponterotto et al. (Citation2017) and Gehart et al. (Citation2001) because qualitative studies are the most used in the field of psychological counsellng. Our study found counseling was mentioned only once.

The seeming paradigmatic inconsistency might be rooted in the sociological and ethnographical traditions where a study is considered to be qualitative when it uses interviews or focus groups (Demuth Citation2015). As sociology and ethnography have a longer tradition in the examined countries, this might cause a mixture of considerations and less strict methodology and epistemology than mainstream qualitative psychology. In psychology the reliability and transparency of qualitative studies have become vital and rigorous. However, qualitative psychology is still looking for its own identity and formula in the global psychological discourse, which might result in ambiguity (Gürtler & Huber Citation2006). Knoblauch et al. (Citation2005) state that research questions in which qualitative methods are used might be influenced by political, economic, social, and cultural backgrounds of the researcher.

We suggest paradigms might be used in a mixed way unless the researcher uses them consistently and transparently by the description of the epistemological foundation, the methodological choices, and the process of analysis.

Reflections and limitations

Our aim was not to conduct a critical study but rather to explore the circumstances of postsocialist qualitative approaches and suggest some possible explanations for their state. Our study used postpositivist and interpretive/constructivist paradigmatic considerations at the same time in almost every coding aspect. As our study was based on our presupposition of the existence of paradigms, both deductive and inductive categories, theory and data-driven categorizations were used. Multiple realities and the objective existence of philosophical paradigms occurred at the same time. This study is neither a postpositivist nor an interpretivist/constructivist study, but rather is a mixture of them. Self-reflectively, we would put our study in the “cannot be categorized” category. But our examining process appeared to be a suitable one, providing a frame for the examination of paradigms. As a result, we could concentrate on the exact aspect of the paradigm considerations, and decisions were easier to make as they were dichotomous questions. However, we must state our method is reductionist and further refinements are needed, such as observing the interconnections of the categories and introducing the theoretical considerations of our method in a theoretical article.

Finding suitable articles proved to be difficult. We suppose that due to searching issues and because we could only analyze English language articles, our study could reach only a small part of the qualitative studies published in this area. Thus, we could present only a small section of it. As sampling turned out to be difficult and time-consuming, a small number of qualitative research papers were found. This is why we did not have the option of selecting articles based on their quality or using other criteria. Because of the small number of articles we had access to, which included studies carried out by a multinational research team where at least one author was Central-Eastern European were analyzed. We considered them to be connected to the research trends in this geographic area. However, it might lead to imprecision. The small amount of English language qualitative psychology research might be because of the language sensitivity of qualitative research, or the lack of proper language skills as well.

The 16 answers received from the Central-Eastern European universities were not enough to make generalizations or valid statements for the whole area. Information about the situation of qualitative psychology at universities was rarely available in English.

As we used deductive coding categorization, we focused on the hypothetical paradigms and fields of the studies in which the exact logic of the articles was not presented or discussed.

Without many previous studies on this topic, we had to create most of our research tools, such as our paradigm-analysis coding system, which requires further discussions, reviews, applications and refinement.

Suggestions for further research

The examination of qualitative paradigms and qualitative psychology in a geographic area is an unexamined field of the psychological discourse. We believe that because of its cultural and scientific background, it might be an important pathway for further studies as precious knowledge could be gained on the intercultural interpretations of epistemology, methodology, and ontology in a newly growing and progressing theoretical approach in psychological qualitative research. We consider it to be vital for qualitative research to create such reflections, mappings, and reviews to detect the quality of studies and also to examine the paradigms used and work on the paradigm theory as well.

Conclusions

The examination of how it is possible to manage plural epistemologies, methodologies, and ontologies simultaneously might also be needed in the theory of qualitative psychology. The American trend of qualitative psychology suggests making qualitative research more transparent and adopting higher standards in the description of qualitative methods (Bluhm et al. Citation2011). However, Symon et al. (Citation2018) draw criticism about whether the standardization of quality in qualitative research would be inappropriate and lead to the marginalization of alternative methods.

All in all, the rise of qualitative research was a paradigm shift; an answer to the positivist psychology's expanded anomalies. Perhaps the true nature of the qualitative approach is that it does not require a rigorously defined identity and formula or systematically structured frames.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the following universities and colleagues for their answer to our e-mailed questions about the state of qualitative education, research, and publications: Sara Bigazzi (University of Pecs, Hungary, Institute of Psychology); Ágnes Szokolszky (University of Szeged, Hungary, Institute of Psychology); Ágnes Hőgye-Nagy (University of Debrecen, Hungary, Hungary, Institute of Psychology); Anett Szabó-Bartha (Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church, Hungary); Szabolcs Gergő Harsányi (Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church, Hungary); Barbara Lasticova (Slovak Academy of Sciences, Slovakia), Martina Žákova (University of Tvrna, Slovakia), Michal Miovsky (Charles University of Prague, Czech Republic), Mgr. Ema Hresanova (University of West Bohemia, Czech Republic), Rado Masaryk (Comenius University, Faculty of Social and Economic Sciences, Slovakia), Agnieszka Sowinska (Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, Poland), Tomáš Řiháček (Masaryk University, Institute of Psychology, Czech Republic), Bogdan Nemes (Universitatea de Medicina si Farmacie, Romania) and Gábor Horváth for the tables and charts.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Asztrik Kovács

Asztrik Kovács is a psychologist and a Ph.D. student at Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest. He is also a member of Qualitative Psychology Research Group. His field of research is qualitative and interculutural psychology. He has a special interest in translation dilemmas in qualitative psychological publications. He also makes autoethnography based performances.

Dániel Kiss

Dániel Kiss, is a Ph.D. student in psychology at Eötvös Loránd University (Budapest, Hungary). He got his MA and BA at the same institution. He is a client-centered counselling psychologist. His research focuses on the qualitative assessment in changes of time perspectives in recovery from addiction narratives. Qualitative thematic –and narrative analysis are his research interest. He is a poet in his free time.

Szilvia Kassai

Szilvia Kassai is Ph.D. candidate in Doctoral School of Psychology at Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest. Her main research topic is examining drug users’ experiences with qualitative methods, which determined her research inquiry during the PhD years. She assessed experiences of novel psychoactive substance users by using Interpretative phenomenological analysis. She is also working as a desk officer for drug issues at the Hungarian Ministry of Human Capacities, and she is also involved in projects about examining and monitoring drug problem and related interventions.

Eszter Pados

Eszter Pados is a Ph.D. student in Psychology at the Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE, Budapest, Hungary). Her research focuses on participatory action researches and art-based action researches. She received her BA as a Special Need Educator and Therapist, and Master’s degree from Criminology. She works in a Detention Center and with marginalised groups in different fields.

Zsuzsa Kaló

Zsuzsa Kaló, is an assistant professor at the Institute of Psychology of ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary. She is psychologist and has a Ph.D in linguistics. Her field of research is qualitative drug research methods, interdisciplinary solutions in data collection and analysis. Her primary interest is focused on studying female addiction and trauma narratives among Hungarian girls and women. She has conducted studies on the topic at the Institute of Psychology at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and at ELTE Eötvös Loránd University.

József Rácz

Dr. József Rácz, MD, Ph.D. is a professor at the Department of Counselling Psychology, Institute of Psychology, Eötvös University (Budapest, Hungary) and at the Department of Addictology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Semmelweis University (Budapest, Hungary). His research interests are the addictions and applying qualitative research methods in psychology. These projects are carried out under the scope of the Qualitative Psychology Research Group at Eötvös University. He has studied people who inject drugs and the use of new psychoactive substances. He has got his clinical experience at Blue Point Drug Counselling Centre.

References

- Alesina, A & Fuchs-Schündeln, N 2007, ‘Goodbye Lenin (or not?): the effect of communism on people's preferences’, American Economic Review, vol. 97, no. 4, pp. 1507–28.

- Angermüller, J 2005, ‘“Qualitative” methods of social research in France: reconstructing the actor, deconstructing the subject’, Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, vol. 6, no. 3, viewed 06 May 2019, http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/8

- Berríos, R & Lucca, N 2006, ‘Qualitative methodology in counseling research: recent contributions and challenges for a new century’, Journal of Counseling & Development, vol. 84, no. 2, pp. 174–86.

- Bluhm, DJ, Harman, W, Lee, TW & Mitchell, TR 2011, ‘Qualitative research in management: a decade of progress’, Journal of Management Studies, vol. 48, pp. 1866–91.

- Bruni, A & Gobo, G 2005, ‘Qualitative research in Italy’, Forum: Qualitative Social Research, vol. 6, no. 3, http://www. qualitative-research. net/fqs-texte/3-05/05-3-41-e. htm

- Buklijas, T & Lafferton, E 2007, ‘Science, medicine and nationalism in the Habsburg Empire from the 1840s to 1918’, Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 679–86.

- Bunce, V & Csanadi, M 1993, ‘Uncertainty in the transition: post-communism in Hungary’, East European Politics and Societies, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 240–75.

- Chandler, D 2006, ‘ Semiotics for beginners’, viewed 11 June 2018, https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/34512504/Semiotics_for_Beginners.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1541519057&Signature=qpJ23Wsx8mMQW7RthrMKdZw3PuM%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DSemiotics_for_Beginners_by_Daniel_Chandl.pdf

- Danziger, K 2006, ‘Universalism and indigenization in the history of modern psychology’, in Adrian C Brock (ed.), Internationalizaing the history of psychology, New York University Press, New York, pp. 208–26.

- Davidsen, AS 2013, ‘Phenomenological approaches in psychology and health sciences’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 318–39.

- Demuth, C 2015, ‘New directions in qualitative research in psychology’, Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 125–33.

- Elliott, R, Fischer, CT & Rennie, DL 1999, ‘Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields’, British Journal of Clinical Psychology, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 215–29.

- Elo, S & Kyngäs, H 2008, ‘The qualitative content analysis process’, Journal of Advanced Nursing, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 107–15.

- Gale, J 1993, ‘A field guide to qualitative inquiry and its clinical relevance’, Contemporary Family Therapy, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 73–91.

- Gehart, DR, Ratliff, DA & Lyle, R 2001, ‘Qualitative research in family therapy: a substantive and methodological review’, Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 261–74.

- Gille, Z 2010, ‘Is there a global postsocialist condition?’, Global Society, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 9–30.

- Guba, EG & Lincoln, YS 1982, ‘Epistemological and methodological bases of naturalistic inquiry’, Educational Technology Research and Development, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 233–52.

- Guba, EG & Lincoln, YS 1989, Fourth generation evaluation, Sage, London.

- Guba, EG & Lincoln, YS 1994, ‘Competing paradigms in qualitative research’, in NK Denzin & YS Lincoln (eds.), Handbook of qualitative research, Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage, pp. 105–17.

- Gürtler, L & Huber, GL 2006, ‘The ambiguous use of language in the paradigms of QUAN and QUAL’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 313–28.

- Harré, R 2004, ‘Staking our claim for qualitative psychology as a science’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 3–14.

- Hsieh, HF & Shannon, SE 2005, ‘Three approaches to qualitative content analysis’, Qualitative Health Research, vol. 15, no. 9, pp. 1277–88.

- Knoblauch, H, Flick, U & Maeder, C 2005, ‘Qualitative methods in Europe: the variety of social research’, Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, vol. 6, no. 3.

- Konecki, KT 2005, ‘Polish qualitative sociology: the general features and development’, Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, vol. 6, no. 3.

- Lincoln, YS, Lynham, SA & Guba, EG 2011, ‘Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences revisited’, in NK Denzin & YS Lincoln (eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research, 4, Sage, London, pp. 97–128.

- Marchel, C & Owens, S 2007, ‘Qualitative research in psychology: could William James get a job?’, History of Psychology, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 301–24.

- Marecek, J, Fine, M & Kidder, L 1997, ‘Working between worlds: qualitative methods and social psychology’, Journal of Social Issues, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 631–44.

- Morrow, SL 2005, ‘Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology’, Journal of Counseling Psychology, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 250–60.

- Morrow, SL & Smith, ML 2000, ‘Qualitative research for counseling psychology’, in SD Brown & RW Lent (eds.), Handbook of counseling psychology, Wiley, New York, pp. 199–230.

- Moscovici, S & Marková, I 2006, The making of modern social psychology: the hidden story of how an international social science was created, Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Neuendorf, KA 2016, The content analysis guidebook, Sage, London.

- O’Neill, P 2002, ‘Tectonic change: the qualitative paradigm in psychology’, Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 190–4.

- Olsen, A, Higgs, P & Maher, L 2015, ‘A review of qualitative research in Drug and Alcohol Review’, Drug and Alcohol Review, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 475–6.

- Patton, MQ 2002, ‘Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: a personal, experiential perspective’, Qualitative Social Work, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 261–83.

- Peel, E, Clarke, V & Drescher, J 2007, ‘Introduction to LGB perspectives in psychological and psychotherapeutic theory, research and practice in the UK’, Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy, vol. 11, no. 1–2, pp. 1–6.

- Petty, NJ, Thomson, OP & Stew, G 2012, ‘Ready for a paradigm shift? Part 1: introducing the philosophy of qualitative research’, Manual Therapy, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 267–74.

- Ponterotto, JG 2005, ‘Qualitative research in counseling psychology: a primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science’, Journal of Counseling Psychology, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 126–36.

- Ponterotto, JG 2010, ‘Qualitative research in multicultural psychology: philosophical underpinnings, popular approaches, and ethical considerations’, Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 581–9.

- Ponterotto, JG, Park-Taylor, J & Chen, EC 2017, ‘Qualitative research in counselling and psychotherapy: history, methods, ethics, and impact’, in C Willig & SW Rogers (eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research, Sage, London, pp. 298–522.

- Psychology Resources Around the World, viewed 16 August 2018, http://psychology-resources.org/explore-psychology/association-organisation-information/country-information/

- Rennie, DL, Watson, KD & Monteiro, AM 2002, ‘The rise of qualitative research in psychology’, Canadian Psychology, vol. 43, no. 3, vol. 179–89.

- Rennie, DL, Watson, KD & Monteiro, A 2000, ‘Qualitative research in Canadian psychology’, Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, vol. 1, no. 2.

- Robila, M & Krishnakumar, A 2004, ‘The role of children in Eastern European families’, Children & Society, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 30–41.

- Rose-Ackerman, S 2001, ‘Trust and honesty in post-socialist societies’, Kyklos, vol. 54, no. 2–3, pp. 415–43.

- Rossman, GB & Rallis, SF 2003, ‘Qualitative research as learning’, in GB Rossman & SF Rallis (eds.), Learning in the field: an introduction to qualitative research, Sage, London, pp. 1–30.

- Sexton, TL 1996, ‘The relevance of counseling outcome research: current trends and practical implications’, Journal of Counseling & Development, vol. 74, no. 6, pp. 590–600.

- Stanilov, K 2007, ‘Taking stock of post-socialist urban development: a recapitulation’, in K Stanilov (ed.), The post-socialist city: urban form and space transformations in central and eastern Europe after socialism, Springer, Berlin, pp. 3–17.

- Stenning, A & Hörschelmann, K 2008, ‘History, geography, and difference in the post-socialist world: or, do we still need post-socialism?’, Antipode, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 312–35.

- Swartz, L & Rohleder, P 2017, ‘Cultural psychology’, in C Willig & SW Rogers (eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research, Sage, London, pp. 563–74.

- Symon, G, Cassell, C, & Johnson, P 2018, ‘Evaluative practices in qualitative management research: a critical review’, International Journal of Management Reviews, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 134–54.

- Szokolszky, Á 2016, ‘Hungarian psychology in context. Reclaiming the past’, Hungarian Studies, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 17–55.

- Tímár, J 2004, ‘“More than Anglo-American, it is Western”: hegemony in geography from a Hungarian perspective’, Geoforum, vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 533–8.

- Wertz, FJ 2014, ‘Qualitative inquiry in the history of psychology’, Qualitative Psychology, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 4–16.

Analyzed articles

- Adamczyk, M 2016, ‘Attachment styles and adolescent's psychosocial functioning-case studies’, Psychoterapia, vol. 3, no. 178, pp. 89–102.

- Bianchi, G & Fúsková, J 2015, ‘Representations of sexuality in the Slovak media-the case of politics and violence’, Annual of Language & Politics & Politics of Identity, vol. 9, pp. 43–70.

- Boczkowska, MM & Zięba, M 2016, ‘Preliminary study of religious, spiritual and mystical experiences. Thematic analysis of Poles adult’s narratives’, Current Issues in Personality Psychology, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 167–76.

- Buczkowski, K, Marcinowicz, L, Czachowski, S, Piszczek, E & Sowinska, A 2013, ‘“What kind of general practitioner do I need for smoking cessation?” Results from a qualitative study in Poland’, BMC Family Practice, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 159, doi:10.1186/1471-2296-14-159

- Buzea, C 2015, ‘Romanian employees’ folk theory on work: a qualitative study’, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 187, pp. 196–200.

- Chmielecki, M 2013, ‘Knowledge sharing among faculties–qualitative research findings from Polish universities’, Contemporary Management Quarterly/Wspólczesne Zarzadzanie, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 93–102.

- Chrz, V, Cermák, I & Chrzová, D 2009, ‘Between the worlds of the disabled and the healthy: a narrative analysis of autobiographical conversations’, in D Robinson, P Fischer, T Yeadon-Lee, SJ Robinson & P Woodcock (eds.), Narrative, memory and identities, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, pp. 11–19.

- Cirtita-Buzoianu, C & Daba-Buzoianu, C 2013, ‘Inquiring public space in Romania: a communication analysis of the 2012 protests’, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 81, pp. 229–34.

- Císař, O & Koubek, M 2012, ‘Include ‘em all?: Culture, politics and a local hardcore/punk scene in the Czech Republic’, Poetics, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 1–21.

- Fabula, S & Timár, J 2017, ‘Violations of the right to the city for women with disabilities in peripheral rural communities in Hungary’, Cities, vol. 76, pp. 52–7.

- Gheorghe, IR & Liao, MN 2012, ‘Investigating Romanian healthcare consumer behaviour in online communities: qualitative research on negative eWOM’, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 62, pp. 268–74.

- Halama, P & Halamová, J 2005, ‘Process of religious conversion in the Catholic Charismatic movement: a qualitative analysis’, Archive for the Psychology of Religion, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 69–92.

- Kadlcik, J & Flemr, L 2008, ‘Athletic career termination model in the Czech Republic: a qualitative exploration’, International Review for the Sociology of Sport, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 251–69.

- Kékes Szabó, M & Szokolszky, Á 2013, ‘Dyadic interactions and the development of object use in typical development and autism spectrum disorder’, Practice and Theory in Systems of Education, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 365–88.

- Kelmendi, K 2015, ‘Domestic violence against women in Kosovo: a qualitative study of women’s experiences’, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 680–702.

- Krahé, B, de Haas, S, Vanwensenbeeck, I, Bianchi, G, Chliaoutakis, J, Fuertes, A, de Matos, M. G, Hadjigeorgiou, E, Hellemans, S, Kouta, Ch, Meijinchens, D, Murauskiene, L, Papasakaki, M, Ramiro, L, Reis, M, Symons, K, Tomaszewska, P, Vicario-Molina, I, Zygadlo, A 2016, ‘Interpreting survey questions about sexual aggression in cross-cultural research: A qualitative study with young adults from nine European countries’, Sexuality & Culture, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 1–23.

- Kwaśniewska, JM & Lebuda, I 2017, ‘Balancing between roles and duties—the creativity of mothers’, Creativity. Theories–Research-Applications, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 137–58.

- Levicka, K, Zakova, M & Stryckova, D 2015, ‘Identity of street workers working with drug users and sex workers in Slovakia’, Revista Românească pentru Educaţie Multidimensională, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 19–23.

- Masaryk, R & Hatoková, M 2017, ‘Qualitative inquiry into reasons why vaccination messages fail’, Journal of Health Psychology, vol. 22, no. 14, pp. 1880–8.

- Miovský, M 2007, ‘Changing patterns of drug use in the Czech Republic during the post-communist era: a qualitative study’, Journal of Drug Issues, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 73–102.

- Panaitescu, C, Moffat, MA, Williams, S, Pinnock, H, Boros, M, Oana, CS, Alexiu S, Tsiligianni, I 2014, ‘Barriers to the provision of smoking cessation assistance: a qualitative study among Romanian family physicians’, NPJ Primary Care Respiratory Medicine, vol. 24, doi:10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.22

- Pavlova, B, Uher, R & Papezova, H 2008, ‘It would not have happened to me at home: qualitative exploration of sojourns abroad and eating disorders in young Czech women’, European Eating Disorders Review, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 207–14.

- Pietkiewicz, I & Skowrońska-Włoch, K 2017, ‘Attitudes to professional boundaries among therapists with and without substance abuse history’, Polish Psychological Bulletin, vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 411–22.

- Popper, M, Bianchi, G & Lukšík, I 2015, ‘Challenges to the social norms on reproduction: “irreplaceable mother” and affirmative fatherhood’, Human Affairs, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 288–301.

- Racz, J & Lacko, Z 2008, ‘Peer helpers in Hungary: a qualitative analysis’, International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 1–14.

- Rácz, J, Csák, R & Lisznyai, S 2015, ‘Transition from “old” injected drugs to mephedrone in an urban micro segregate in Budapest, Hungary: a qualitative analysis’, Journal of Substance Use, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 178–86.

- Roberson, Jr., DN & Pelclova, J 2014, ‘Social dancing and older adults: playground for physical activity’, Ageing International, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 124–43.

- Sorina-Diana, M, Dorel, PM & Nicoleta-Dorina, R 2013, ‘Marketing performance in Romanian small and medium-sized enterprises—a qualitative study’, Annals of the University of Oradea, Economic Science Series, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 664–71.

- Surugiu, R 2013, ‘Labor conditions of young journalists in Romania: a qualitative research’, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 81, pp. 157–61.

- Takacs, J, Amirkhanian, YA, Kelly, AJ, Kirsanova, VA, Khoursine, RA & Mocsonaki, L 2006, ‘“Condoms are reliable but I am not”: a qualitative analysis of AIDS-related beliefs and attitudes of young heterosexual adults in Budapest, Hungary and St. Petersburg, Russia’, Central European Journal of Public Health, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 59–66.

- Takács, J, Kelly, JA, PTóth, T, Mocsonaki, L & Amirkhanian, YA 2013, ‘Effects of stigmatization on gay men living with HIV/AIDS in a central-eastern European context: a qualitative analysis from Hungary’, Sexuality Research and Social Policy, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 24–34.

- Trif, V 2013, ‘Cognitive representation of academic assessment in Romania. A qualitative analysis’, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 78, pp. 81–5.

- Wójcik, M & Kozak, B 2015, ‘Bullying and exclusion from dominant peer group in Polish middle schools’, Polish Psychological Bulletin, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 2–14.

- Zörgő, S, Purebl, G & Zana, Á 2018, ‘A qualitative study of culturally embedded factors in complementary and alternative medicine use’, BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 25, doi:10.1186/s12906-018-2093-0

- Žuchová, S 2006, ‘Attitudes of medical students towards people suffering from mental illness—comparison of quantitative and qualitative experimental methods’, Studia Psychologica, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 349–60.