ABSTRACT

This article begins by providing a contextual account of the different ways in which contemporaries of Baudelaire and Manet subscribed to a widespread, though not universal, assumption that the two shared common artistic aims. The article then seeks to establish aesthetic parallels between Manet’s La Musique aux Tuileries (1862) and Baudelaire’s ‘Le Thyrse’ (1863). Sidestepping the vexed question of the extent to which Manet may be seen as an embodiment of Baudelaire’s peintre de la vie moderne, the analysis focuses on the heterodox function of the visual object in triggering a self-reflexive representation of an act of seeing.

The vexed question of whether Charles Baudelaire and Édouard Manet subscribed to a shared aesthetic has been much discussed and continues to prove irresistible to art historians and scholars of nineteenth-century French poetry alike. In outline at least, the biographical facts pertaining to the poet’s friendship with an artist ten years his junior have been established with some certainty. Antonin Proust – Manet’s lifelong schoolfriend and fellow pupil in Thomas Couture’s studio – claimed (Citation1897, 134) to have been present with Manet and Baudelaire when, in April 1859, the painter learned that his Buveur d’absinthe had been rejected by the Salon.Footnote1 Proust also recalled joining the two friends on regular perambulations in the Jardin des Tuileries. In the early 1860s, Baudelaire was a regular visitor to Manet’s studio and it can be assumed that each was aware of the other’s projects and that they compared their views on art and poetry, their ambitions with regard to their creative endeavours, and their views on those of their contemporaries. Had their conversations been recorded by a reliable stenographer, the document would doubtless have removed some of the mystery surrounding how far painter and poet possessed comparable aims with regard to their respective art forms. Specifically, these would likely have revealed the extent to which Manet, whether in his own estimation or that of Baudelaire, may be regarded as an embodiment of the latter’s conception of ‘le peintre de la vie moderne’, which the poet-critic chose to exemplify through the person of Constantin Guys.

Tentative affirmation of an aesthetic affinity between the two creative artists is encouraged by various convergent details that emerge, albeit tantalizingly, from consideration of their friendship. These include the choice of similar representatives of modern urban life by virtue of being outsiders, though Manet was open to a wider range of subject matter. In the 1860s, the artist drew Baudelaire on several occasions, though the resultant etchings defy accurate dating. What is beyond dispute, however, is that the subject’s costume and stance in both versions of Manet’s iconic Baudelaire en chapeau, de profil (Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art and New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art) ( and ) are identical to those that accord the poet such prominence in La Musique aux Tuileries, to the extent that both could easily be seen as preparatory sketches for the painting. Versions of a further etching, depicting a more dandyish Baudelaire, bareheaded and viewed front on (seemingly based on Nadar’s oft-reproduced photograph), are linked to Manet’s wish to be associated with the edition of Le Spleen de Paris he understood Charles Asselineau to be preparing.Footnote2 An example of both poses was included, though with questionable dates, in Asselineau’s Citation1869 biography of Baudelaire. In 1862, Manet had painted Baudelaire’s mistress Jeanne Duval in a portrait that Philippe Sollers characterizes as ‘terrible’, Jeanne’s face being described as ‘ravagé dans un grand cercueil blanc de robe’ (Sollers Citation2013, 65).Footnote3 (See Therese Dolan's discussion in this special issue of Manet's portrait and its reception.) Two years later, Baudelaire dedicated his prose poem ‘La Corde’ to Manet. There is general agreement (see Baudelaire Citation1975–Citation76; 1: 1339 and Hiddleston Citation1992, 573) that the poet’s starting point was the suicide in the painter’s studio of Alexandre, Manet’s model for L’Enfant aux cerises (1862) and the etching Le Garçon et le chien (1862). Insofar as ‘La Corde’ is presented as an oral narrative by a painter who is parenthetically described as ‘mon ami’, a description that is itself deceptively straightforward, the text raises the unanswerable question of the extent to which the reader is here listening to Manet as much as to Baudelaire.Footnote4 It was about this time that Manet produced a drawing and an etching of Edgar Allan Poe, doubtless mindful of Baudelaire’s project of collecting and expanding in book form his essays on the American writer.Footnote5 The year before the publication of ‘La Corde’, Baudelaire collaborated with Manet through the quatrain he provided to accompany Lola de Valence (both the painting and the subsequent etching). Previously, he had published, in Le Boulevard (September 14, 1862), ‘Peintres et aquafortistes’, in which he lauded Manet’s etching Le Guitariste, the original version in oils of which (Le Chanteur espagnol) he described as having caused ‘une vive sensation au Salon dernier’ (Baudelaire Citation1992, 398).Footnote6 In a letter of June 1864 to Théophile Thoré (Baudelaire, Citation1973a, 2: 386–387), Baudelaire took the critic to task for intimating, in a favourable assessment overall, that certain of Manet’s compositions might be regarded as pastiches of Velasquez and Goya. His objection might be considered disingenuous insofar as he had encouraged Manet to study these and other Spanish artists.Footnote7 Manet’s etching after Velasquez’s portrait of Philip IV of Spain, now attributed to an assistant, was made following the purchase of the painting by the Louvre in 1862, the année phare in the painter’s relations with the poet.Footnote8 At the same time, Baudelaire’s tribute to Manet’s authenticity as an artist in his letter to Thoré might be thought to pose as many questions as it provides answers: ‘M. Manet que l’on croit fou et enragé est simplement un homme très loyal, très simple, faisant tout ce qu’il peut pour être raisonnable, mais malheureusement marqué de romantisme depuis sa naissance.’ To these examples, dating mainly from the years 1862 to 1864, the year in which Baudelaire left Paris for Brussels, may be added the information that on the walls of the room in Dr Duval’s clinic in the rue du Dôme where Baudelaire died there was hung one of Manet’s works, together with a copy of Goya’s Duchess of Alba that seems also to have belonged to the painter.Footnote9

Figure 1. Édouard Manet, Baudelaire de profil en chapeau (1862 or 1867–68, Paris: Bibliothèque de l’INHA).

Figure 2. Édouard Manet, Portrait of Charles Baudelaire in Profile (1862, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Such was the interaction between Baudelaire and Manet in the early 1860s, which would have been well known in the overlapping artistic, literary and journalistic circles of the period, that it is hardly surprising that contemporaries saw them as kindred spirits. As David Carrier has observed, ‘this cliché is established early on’ (Citation1995, 397). Alfred Sensier (pseud. Jean Ravenel),Footnote10 writing in L’Époque on June 7, 1865 on the subject of the furore created by Manet’s Olympia, dubbed it ‘peinture de l’école de Baudelaire exécutée par un élève de Goya’.Footnote11 His article possesses particular interest in the present context for its unusually specific quotation of two stanzas (lines 25–32) from the later of the two poems in Les Fleurs du Mal entitled ‘Le Chat’ (‘Dans ma cervelle se promène’)Footnote12 and the Goya stanza from ‘Phares’. As T. J. Clark has observed, with reference to Sensier’s piece, ‘the link between Olympia and Baudelaire was rather rarely made’, though he refers to an article on Olympia by Louis LeroyFootnote13 in L’Universel in which a ‘passing mad invocation’ includes the exclamation ‘O chat! O chat! … O chat animé de Baudelaire’ (Citation1984, 296).Footnote14 The previous year, Leroy, in a satirical sketch in Le Charivari that Hamilton understandably derides as ‘labored’ and devoid of any lasting humour (Citation1986, 32),Footnote15 had, however, imagined the ‘distribution des récompenses’ awarded at the annual Salon, where Manet’s two paintings had not found favour with the judges.Footnote16 The occasion is interrupted by the arrival of Manet, described as follows: ‘Le jeune artiste, hissé sur un pavois porté par MM. Baudelaire, Champfleury et de Broglie père et fils, s’arrête devant le bureau’ (Leroy Citation1864d, 90).Footnote17 A ludicrously uncouth Baudelaire acts as spokesman, though on occasion with recourse solely to animal noises. After his initial (incomprehensible) intervention, the chairman attempts to silence him (‘Monsieur Baudelaire, vous n’avez pas la parole ici’). Eventually having re-established himself, it is said, as an ‘homme du monde’, Leroy’s poet delivers the following diatribe:

Ce prix semble indiquer une critique de la part de la commission des récompenses; et, si gâteux qu’en soient les membres, si pestilens, si abrutis, si crétinisés qu’ils paraissent, j’avoue que je ne me serais jamais attendu à une déjection aussi infecte. Soyez fiers, messieurs; vous venez de donner barre sur vous aux mollusques, aux zoophytes, aux produits les moins vertébrés de la flore sociale et humanitaire. Merci, brutes; brutes, merci!

Not all, however, subscribed to the view of a parenté between Baudelaire and Manet. In 1867, Zola, responding to what he perceived as a widespread readiness to see them forming an alliance in the promotion of a related conception of modernist art, declared:

[J]e profite de l’occasion pour protester contre la parenté qu’on a voulu établir entre les tableaux d’Edouard Manet et les vers de Charles Baudelaire. Je sais qu’une vive sympathie a rapproché le poète et le peintre, mais je crois pouvoir affirmer que ce dernier n’a jamais fait la sottise, commise par tant d’autres, de vouloir mettre des idées dans sa peinture. La courte analyse que je viens de donner de son talent prouve avec quelle naïveté il se place devant la nature; s’il assemble plusieurs objets ou plusieurs figures, il est seulement guidé dans son choix par le désir d’obtenir de belles taches, de belles oppositions. Il est ridicule de vouloir faire un rêveur mystique d’un artiste obéissant à un pareil tempérament. (Citation2021, 479)Footnote18

Whatever Zola’s motives for challenging the Baudelaire-Manet conjunction, he was well positioned as Manet’s recent biographer to replace Baudelaire as the painter’s champion following the poet’s death, especially after the appearance of Manet’s portrait of the novelist at the Salon of 1868. Leroy, in a further attempt at satire that appeared in Le Journal amusant on May 23 of that year duly conjoined painter and writer in the statement ‘Manet est Manet, et Zola est son prophète’ (cited by Robert Lethbridge in Zola Citation2021, 690). It is to be noted, however, that the remark is not authorial but placed in the mouth of an unnamed fictional painter (see Leroy Citation1868) and demands to be considered in situ. The theme of Leroy’s piece is contained in his title: ‘La grande trahison des maréchaux de Courbet.’ It is initially set in a private room at a brasserie where Gustave Courbet and his followers are said habitually to meet, though on this occasion the painter was not present.Footnote20 The discussion turns on whether, in the light of the artist’s most recent work, the painter’s acolytes would switch their allegiance to Manet. Summoned subsequently to his dwelling, ‘les deux mamelucks du maître’, accompanied by an equally anonymous art critic, and emboldened by Courbet’s self-congratulatory report on his visit to the Salon, launch into devastating assessments of Le Mendiant. (Courbet’s painting had been met with almost universal disapproval by the critics (Mack Citation1951, 224–225).) As they take their leave, one of them adds: ‘Nous vous supplions de renoncer à la lutte; vous n’êtes plus de force, Manet tient la corde, la victoire est à lui.’ To which, Leroy’s Courbet retorts: ‘Manet! […] Manet n’a pas de racines dans notre France artistique! Il y est entré dans les fourgons de Zola!’ It is this remark that provokes the assertion ‘Zola est son prophète’, which Courbet then caps with ‘Dites qu’il sera son Talleyrand’ (Leroy Citation1868, 4), which would appear to imply on the part of the fictional Courbet a prediction that Zola’s support for the artist was not to be relied upon. The sceptical Leroy thus both acknowledges Zola’s role and calls into question its sincerity. The same satirical perspective was responsible for a contemporary caricature of the author in Le Monde pour rire being captioned ‘L’Inventeur de M. Manet’ (see Zola Citation2021, 65). Notwithstanding the superficiality of such quips, it was inevitable that Zola’s championship of Manet should come to overshadow the role, such as it was, of Baudelaire, though the Baudelaire-Manet conjunction would not be completely eclipsed, as Huysmans’s reflections on Manet’s œuvre following the painter’s death in 1883 reveal (see note 12).

Twentieth-century academic commentators were initially content to inherit a view of Baudelaire and Manet rooted in a biographical perspective that revealed little more than friendship and valued social interaction. Thus, Enid Starkie happily concludes that ‘their friendship was the result of intimate understanding between two very similar personalities with similar aspirations’ (Citation1957, 422).Footnote21 Pierre-Georges Castex likewise restricts himself essentially to rehearsing a commonplace.Footnote22 The respective views, on the part of Manet and Baudelaire, of the other’s creative enterprise remained elusive,Footnote23 as did the means to pinpoint convincingly the trajectory of influence or cross-fertilization, or the identification of a level at which the separate critical discourses applied to poetry and painting might be transcended. The difficulty of the enterprise doubtless explains the subsequent shift to a consideration of why Baudelaire was seemingly so reticent in his praise for the work of an artist who appeared to be imbued with a similar modernist aesthetic. The motivation to probe the question has not infrequently stemmed from irritation or embarrassment that Baudelaire readily talked up the art of Guys (the M. G. of Le Peintre de la vie moderne)Footnote24 or Alphonse Legros (and not solely that artist’s etchings recalled in ‘Peintres et aquafortistes’ (Baudelaire Citation1992, 397–401)).Footnote25 Starting with Philippe Rebeyrol’s landmark essay in Les Temps modernes (Citation1949), the question has formed the dominant perspective from which to consider the artistic relationship between the two figures. A number of salient points have been made in an attempt to understand why the corpus of critical comments by Baudelaire on Manet’s art was so meagre. It is furthermore tempting to suggest that Baudelaire’s relative silence might constitute an example of his pudeur, a reluctance to praise, or even speak of, art that had been produced in the context of their discussions of work in progress. For his part, James A. Hiddleston has looked beyond the ‘reasons […] put forward to explain or to explain away Baudelaire’s failure to recognize Manet as the painter of modern life’ (Citation1992, 567). Instead, he teases out clues in the art and poetry themselves, while stressing the extent to which tangible differences might at the same time be turned on their heads and seen to possess an appeal for the author of Le Peintre de la vie moderne. Yet his analyses, for all their specific insights, necessarily remain speculativeFootnote26 insofar as they are motivated by a preconceived determination to understand, in the face of a lack of documentary evidence, why Manet’s art should have aroused in Baudelaire what Claude Pichois terms an ‘admiration mitigée’ (Baudelaire Citation1975–Citation76, 1: 1339).Footnote27

Rather than taking this supposedly lukewarm response on Baudelaire’s part as a given in need of explanation, the analysis that follows will be conducted on the basis of a belief that in the face of such deeply ambiguous evidence, the poet’s view of his friend’s art (especially his paintings) is destined to remain elusive. My more modest aim will be to examine the ways in which a particular painting by Manet and a particular prose poem by Baudelaire partake of a shared aesthetic that reveals itself at an intertextual level: La Musique aux Tuileries (1862) (London: National Gallery) (), the subject of which Castex claimed, but without adducing evidence, had been suggested by Baudelaire (Citation1969, 75–76), and ‘Le Thyrse’ (Revue nationale et étrangère, December 10, 1863), dedicated to Franz Liszt. My concern will be with the ways in which, in both the painting and the poem, the representation of visual objects highlights a self-conscious focus on an act of seeing. It will not be my intention to examine what Anna Green has described as the ‘commonplace’ suggestion that Manet’s canvas ‘exemplifies features of Baudelaire’s The Painter of Modern Life’ (Citation2007, 26).Footnote28 Neither will there be any attempt to assess specific aspects of their work in terms of influence.Footnote29

Reviewing La Musique aux Tuileries

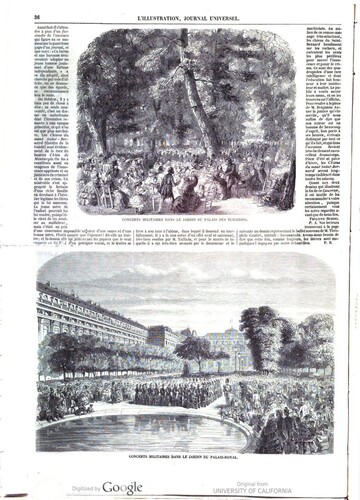

As Hiddleston has observed, La Musique aux Tuileries is a painting in which ‘objects, chairs and so on are foregrounded and take on as much importance as the figures who, in spite of their prestige […], appear as a décor on an equal footing with the objects and the trees’ (Citation1992, 569). In some ways it might indeed be said that the objects and trees acquire for the viewer even greater importance as a result of the manifestly unconventional nature of the emphasis they receive. It is on the chairs that I shall dwell, not least because I shall have occasion to return to them in connection with Baudelaire’s prose poem. At the time of Manet’s painting, the metal chairs in the Tuileries were a recent appearance (), having replaced the wooden examples visible in certain slightly earlier depictions of the park (see Sandblad Citation1954, 21, 37, 168). The latter may be seen most clearly in Adolph Menzel’s Afternoon in the Tuileries Gardens (London: National Gallery) () but also, as Werner Busch’s study of Menzel allows us to see, in a wood engraving by A. Provost entitled Concerts militaires dans le Jardin du Palais des Tuileries and reproduced in L’Illustration on July 17, 1858 (Busch Citation2017, 200) ().Footnote30 (Provost’s xylograph might be taken as the stimulus for Manet’s composition, more readily in fact than the lithograph also suggested by Busch: Eugène Guérard’s Les Tuileries (Allée des Feuillants), which formed part of his Physionomies de Paris (1856) (Busch Citation2017, 193 and 199).)Footnote31 Although Menzel’s painting (1867) postdates La Musique aux Tuileries, it was, as its original title (Sunday in the Tuileries Gardens from Memory) appears to indicate, based on a scene witnessed a number of years previously, in all likelihood during his visit to Paris in 1855, when the wooden chairs were still in place (Busch Citation2017, 192).Footnote32 It matters little whether Manet’s chairs offer an accurate representation of the design of the new metal chairs, because, as I shall argue, their function in his painting is neither mimetic nor anecdotal. Nor does the provocative emphasis they receive open up discernible levels of interpretability, save insofar as they might be seen as an (essentially neutral) representation of Second Empire ostentation on a par with the Sunday best displayed by the two seated female figures in the foreground, teasingly dressed, it would seem, in order to connote, through their identical costumes, daughter and mother, when Madame Lejosne and Madame Loubens/Madame Offenbach were unrelated. The question of the latter’s identity behind her veil seems destined to remain unresolved.Footnote33 As for Madame Lejosne, wife of a former army officer and cousin of the painter Frédéric Bazille (who would serve on occasion as agent for both Baudelaire and Manet),Footnote34 it was at her house that the poet and painter had met. Manet’s positioning of Baudelaire in profile immediately behind her may be considered a clin d’œil addressed to the persons concerned.Footnote35 Bazille, wearing a smart grey hat, is also present in Manet’s painting, again in profile, in a direct line leading upwards from Madame Loubens/Madame Offenbach. Similarly, the mischievous Manet juxtaposes unoccupied chairs on the right with others on the left that are very substantially occupied, especially by the elder of the two figured ladies, and in further contrast to the adjacent chair on which an enigmatic black shape that has often been taken for a catFootnote36 is positioned so as to reveal the chair’s decorative design. In opposition again, the ample figure of Madame Offenbach/ Loubens serves to obscure totally the legs of Madame Lejosne’s chair while exposing just the strikingly slender tips of the two rear legs of her own.Footnote37 If the chairs possess for the viewer a magnetic attraction, the prestige they acquire is essentially aesthetic. They all but lose their functional dimension. Central to this attraction is the insistent decoration in the form of arabesques, an emblem of non-referentiality, though as Cachin has indicated, ‘le groupement des chaises au premier plan introduit un motif coloré de courbes répétées, que l’on retrouve dans tout l’univers féminin du tableau’ in contrast to the multiple examples of masculine verticality (Cachin, Moffett, and Bareau Citation1983, 123) ().

Figure 6. A. Provost, Concerts militaires dans le Jardin du Palais des Tuileries (L’Illustration, journal universel, 17 July 1858).

Figure 7. Édouard Manet, A Cat Resting on All Fours, Seen from Behind (1861, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Manet’s chairs may therefore be seen to point to the way his subject is the self-reflexive nature of the composition – what Busch’s translator renders as ‘the picture character of the picture’ (Citation2017, 199) – and the medium of paint itself. With reference to Olympia, Barbara Wright attributed the scandal it provoked to ‘the painter’s use of impasto, the very materiality of the paint itself, to render what he saw’ (Citation1998, 212). It is necessary only to look at Madame Lejosne’s face to see the relevance of this remark to La Musique aux Tuileries.Footnote38 Everything is designed to direct our attention to the innovative artistry, which has no purpose beyond itself except, arguably, to advance the cause of the avant-garde.

With this single-mindedness in view, Manet imbues every element in his composition with a cultivated strangeness that disconcerts the initially conservative viewer, a strategy that might be thought destined to appeal to Baudelaire. (It was in the latter’s piece on the 1855 Exposition universelle that he threw out his, in itself enigmatic, statement ‘Le beau est toujours bizarre’ (Baudelaire Citation1992, 238).) Suzanne Singletary, in a discussion of Manet’s Le Chanteur espagnol, refers appropriately to the way (purposeful) discrepancies had ‘sabotaged the ostensibly “realist” portrayal of a Spanish “type” and rendered meaning ambiguous’ (Citation2012, 51),Footnote39 though it might be added that, paradoxically, he remained in close contact with the very subject matter of realism. Not only was he, in the service of his aesthetic goal, concerned to thwart interpretation, his consistent recourse in his work to ‘making strange’Footnote40 may be seen as a highly effective way of leading the viewer to recognize the unstable status of the images that together make up his composition. Busch suggests that Manet in La Musique aux Tuileries is ‘mimicking the way in which the gaze is caught here and there by strong visual stimuli while it merely scans and glides over other things’ (Citation2017, 193). This is a seductive, if recuperative, assessment, but it seems possible to make sense of Manet’s composition slightly differently. As Busch himself acknowledges, ‘Manet dispensed with developing a coherent sense of space’ (Citation2017, 193). For his part, Pierre Bourdieu has remarked upon an ‘absence of pictorial coherence’ but goes further in stating that ‘the work looks visually fragmented’ (Citation2017, 468), which indeed it is. While seeming, as Bourdieu says, to offer something akin to a snapshot (469), it does not convey a sense of an observed scene, an accurate record of who was present in the Tuileries on a particular Sunday afternoon, but appears as an assemblage of figures sketched or painted separately and inserted in the manner of a montage, which to a large extent it was. (Bourdieu rightly says that ‘the characters seem placed on the canvas at random’ (468).) As such, it invites association with a practice common in the French illustrated magazines of the period, that of visualizing prominent individuals in a single concrete setting as if the gathering was real rather than imaginary. Equally pertinent arguably is the way the canvas may be experienced as an amalgam of the naturalistic and the composed, in a stylized randomness. This, in turn, may be seen as part of a wider elision of a clear-cut distinction between art and nature, the natural and the artificial, dress and costume (for example the universal frac, or morning coat),Footnote41 or outdoor location and theatrical stage: the trees have something of painted scenery, while the most prominent trunks are used both as emphatic technical devices that are the opposite of a backdrop and as witty echoes of the male figures in formal dress. In this context, the visual object may be said to participate in a blurring of the distinction between animate and inanimate.

If everything in La Musique aux Tuileries is directed towards heightening the viewer’s awareness that he or she is looking at a work of art, it is, at least in part, the activity of looking or seeing that unites painter, viewer and the figures present in the painting.Footnote42 As far as the viewer is concerned, at a basic level, he or she is drawn into a scrutiny of the crowd in the not unjustifiable expectation that it might be possible to identify at least some of the individuals depicted. But at another level, the painting may be seen as an invitation to reflect on its status as a self-conscious composition. Following the initial impression that the canvas contains a superfluity of details competing, albeit to a greater or lesser extent, for our attention, this implied self-consciousness is immediately apparent from the way the two prominent ladies in the foreground, who inevitably attract our attention as we attempt to achieve a sharper focus, seem to direct their gaze simultaneously at both the viewer and the invisible painter (himself imaginable in the pose of a photographer, or, to extend Manet’s title into the realm of metaphor, that of an orchestral conductor about to call all those present to attention, thereby echoing the gaze of Madame Offenbach/Madame Loubens).Footnote43 But this self-consciousness is wittily reinforced by further details, not to say clues, vying for our consideration. Amongst these may be counted the spotlight directed at the bespectacled Jacques Offenbach.Footnote44 As for Madame Offenbach/ Madame Loubens’s veil, it may not impede her vision but it might be thought to reduce her visibility for the viewer, while, paradoxically, seeming not to do so. This invites the conclusion that Manet highlights not only seeing but also non-seeing, and not in strict accordance with ophthalmic science either. This is stage lighting. In contrast to figures who are identifiable from the sharpness of their facial characteristics – or, in the case of Baudelaire, from the view of him in profile which, in Manet’s hands, was already on the way to becoming the defining image of the poet – there are many physiognomies in La Musique aux Tuileries that, for whatever reason, defy recognition, to the extent that certain portions of this pre-Impressionist canvas display an almost unfinished quality. The young woman who seems to enjoy Offenbach’s company has her back to us. Given the implicit representation of time in this painting, in as much as the latter appears to be capturing a precise moment (while manifestly displaying characteristics that call such a naturalistic assumption into question), the viewer may sense that were the young woman to turn round, her illuminated face would reveal her identity. In this context, the chairs, which in terms of visibility represent the whole gamut of possibilities, are emblematic of the composition as a whole.

What this leads to is an increased sense of a heightened and unified experience of the materiality of Manet’s painting in its totality, a gradual awareness of a different kind of coherence from the ‘pictorial coherence’ that Bourdieu sees as absent (Citation2017, 468). It is a coherence that derives from harmonies of shape and colour, in which echoes and contrasts produce an evident impression of structure, as well as from the obvious gendering that lies at its heart.

Reconsidering Baudelaire’s ‘Le Thyrse’

In this context, it has seemed appropriate, in the consideration of Baudelaire’s ‘Le Thyrse’ that follows, to take the 1863 version that appeared in the Revue nationale (see Appendix) rather than the more familiar version of 1869.Footnote45 Although the latter presents only a single, orthographical, variant, the layout of the two versions is significantly different. We are used to reading the poem in two paragraphs of unequal length. The original version consisted of four more evenly matched paragraphs that approximate to stanzas of a verse poem. This makes for a very different reading experience. Whereas in 1869 the sentence containing the first textual apostrophe to Liszt immediately follows without a break the last of the three essentially rhetorical questions, none of which is addressed explicitly to the poem’s dedicatee, the statement ‘Le thyrse est la représentation de votre étonnante dualité, maître puissant et vénéré’ had originally begun a new paragraph. The later version instead morphs abruptly into an unexpected tribute to the composer that is loosely continued through the incorporation of the previously separate third paragraph (separated from the original second paragraph only by a casual dash). By virtue of forming part of the opening statement in each of three successive paragraphs, the three explicit apostrophes to the poem’s dedicatee in the 1863 version highlight much more purposefully (or rhetorically) Baudelaire’s concern to establish a communality between his poetry and the composer’s music.Footnote46 In short, the Figaro reader in 1863 is presented with a clear sense of an organizing structure that might be thought to make this the version closer to the self-reflexive pictorial art of Manet even if it reduces the extent to which the poem may be seen as a mise-en-abyme of the meandering to which the poet alludes.

The quintessentially visual object that Baudelaire takes as his starting point is, in his probing depiction, almost over-determined as a concretization of the aesthetic. His thyrsus is inseparably both a simple stick (‘ce n’est qu’un bâton’, etc.) and the flowers and vine branches that adorn it, in other words a poetic whole that is more than the sum of its parts. Yet it is not merely the materiality of the object that Baudelaire highlights but also the materiality of the word itself, which is never allowed to lose its curious distinctiveness, while not being intrinsically melodic or overtly sensuous. (When it appears in Richelet’s dictionary, the only example of a rhyme the compiler identifies is Agathyrse, son of Hercules.) This is in contrast to the more matter-of-fact appearance it possesses in, say, the final section of Théodore de Banville’s poem ‘Erato’ (Citation1842, 163). It is also attributable to the fact that Baudelaire’s poem demonstrably has its origin in writing, that of others but also his own. In the conclusion to his hybrid text Un mangeur d’opium of 1859, which he had described as ‘une analyse d’un livre excessivement curieux’Footnote47 (Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater), he had drawn attention to the author’s comparison, made in 1845 in the sequel to the Confessions he entitled Suspiria de Profundis,Footnote48 between the narrative structure of his earlier work and a thyrsus, though in fact De Quincey mistakenly called it a caduceus.Footnote49 In a November 1839 article in the Revue des Deux Mondes on the debut performance of the singer Pauline Garcia at the Théâtre italien, Alfred de Musset had evoked the image of the thyrsus when contesting Diderot’s view of the relationship between text and music and it is not impossible that Baudelaire was led to this article by his awareness that Musset was the A.D.M. who, aged seventeen, had published a ‘translation’ of De Quincey’s work in 1828 under the title L’Anglais, mangeur d’opium, though a copy would not easily have been traced.Footnote50 It might also be that the opera-loving De Quincey’s description of a thyrsus was itself the result of his having come across Musset’s article, notwithstanding the English writer’s confusion of thyrsus and caduceus.Footnote51

Less conjectural is to observe that Baudelaire, both in the ‘Précautions oratoires’ at the outset of Un mangeur d’opiumFootnote52 and in his ‘Conclusion’,Footnote53 not only introduces the image of ‘le thyrse’ but in the latter chapter also retains key elements of the lexis from the ‘Introductory Notice’ (De Quincey Citation1845, 269–73) to Suspiria de Profundis in which De Quincey evokes the caduceus-thyrsus: ‘vagabond’ (‘vagrant’) and ‘bâton sec’ (‘dry […] pole’); and that the second of these elements appears in ‘Le Thyrse’ alongside a further example from the Suspiria passage: ‘méandres’ (‘meandering’), together with examples of a related lexis that Baudelaire had introduced independently in his conclusion to Un mangeur d’opium: ‘folâtres’, ‘sinueuse’, ‘spirale’. In the poem, we find not only ‘fleurs sinueuses’ but also ‘sinuosité du verbe’, which unites the floral and the poetic in a way that enhances the poem’s visual dimension.Footnote54 As for De Quincey’s ‘flowers’ and ‘flowering plants’, they become ‘pampres’ and ‘fleurs’, a combination likewise carried over into the poem, albeit in reverse order.

Additionally, the poet of ‘Le Thyrse’ incorporates echoes of an expansive passage in Liszt’s Des Bohémiens et de leur musique en Hongrie (Citation1859), a copy of which the author gave Baudelaire in return for the latter’s gift of Les Paradis artificiels (1860), in which work Liszt would have been able to read Un mangeur d’opium. The passage in question (Liszt Citation1859, 229ff),Footnote55 which encourages the reader to imagine a tempo marking of presto, is a remarkable representation of the geometrical intricacies that Liszt sees as embodying the Bohemian musician’s relentless pursuit of ‘fantasy’ (Liszt Citation1859, 232). To note therefore is Baudelaire’s reference to fantaisie with regard to Liszt in ‘Le Thyrse’ (where the quality is designated as the musician’s ‘élément féminin’) and more generally, in other poems in Le Spleen de Paris, as well as elsewhere in Des Bohémiens. Liszt alludes to ‘tous les serpentements d’une fantaisie qui galope à perte de vue’ (Citation1859, 229), having previously (196) referred to the ‘caprices de la fantaisie’ and before that (99) to ‘une fantaisie capricieuse’. Baudelaire in his prose ‘Invitation au voyage’ evokes ‘la chaude et capricieuse fantaisie’ (Citation1975–Citation76, 1: 301). Similarly, in ‘Le Thyrse’ he evokes ‘des méandres capricieux’, which echo Liszt’s ‘les plus étranges méandres’ (Citation1859, 229), though composer and poet alike would have found De Quincey’s caduceus-thyrsus already ‘wreathed about with meandering ornaments’ (De Quincey Citation1845, 273) The embellishments, which Liszt represents as turning in and back on themselves and which could be summed up as an example of Baudelaire’s refusal of the straight line, are seen by the composer explicitly as ‘arabesques’; additionally, he says of these embellissements that the Bohemian musicians are ‘maîtres ès arts dans le talent de les composer’ (Liszt Citation1859, 232). (His own compositions include several arabesques.) These ‘arabesques’ are then compared to the architecture of the Alhambra.Footnote56 Liszt’s evocation of the term sends us back to Manet’s decorative chairs, while also producing an echo in ‘Le Thyrse’ in the phrase ‘ligne droite et ligne arabesque’. Baudelaire’s participation in the contemporary fascination with Bohemian culture, which he shares with Liszt, is apparent from one of the earliest poems in Les Fleurs du Mal, ‘Bohémiens en voyage’,Footnote57 but following his involvement with Liszt and Manet this fascination clearly acquired a new aesthetic dimension.Footnote58 The interweaving by Baudelaire of motifs present in Manet, De Quincey and Liszt clearly has its origin in the poet’s activity as a critic of literature, art and music. Yet rather than simply recycling a more or less explicit set of cultural allusions, this interweaving gives rise in ‘Le Thyrse’ to what might be regarded as an incipient Gesamtkunstwerk. A parallel might be seen in some small degree in the range of cultural figures identifiable in La Musique aux Tuileries but, more importantly, in the way the ‘music’ of Manet’s title functions as a formal dimension of the painting rather than as a bland identification of the social event on which his canvas is based.

In accord with such elements, Baudelaire also sees the decoration of the thyrsus as ‘un mystérieux fandango’. The fandango, which had so delighted Théophile Gautier in Vélez-Málaga but which was denied him elsewhere in Spain (Citation1845, 291), was one of the Spanish dances Fanny Elssler had popularized on the Parisian stage,Footnote59 and, as Therese Dolan has noted, its popularity was duly exploited by Offenbach.Footnote60 It obviously chimed with Manet’s profound engagement with Spanish art. Giacomo Casanova had evidently claimed that it was best performed by Bohemian dancers,Footnote61 so it was clearly at home in a prose poem deriving inspiration from a composer so closely associated with Bohemia. Liszt himself seems not to have referred in his writings to the fandango, but he did include variations on the dance in the Romancero espagnol for piano he wrote during his Iberian travels a few years after those of Gautier.

The thyrsus as visual object, then, serves, through Baudelaire’s emphasis on its inherent materiality, rather than its significance or function (which are set aside as soon as they have been mentioned), as a starting point for an illustration of the way his prose poem develops an exclusive concern with itself as an embodiment of artistic creation far removed from familiar visual experience, and demonstrating in the process the ability of poetry to emulate the effects of art and music. As with La Musique aux Tuileries, the reader is led to engage with the way the work leaves behind its concrete starting point and multiplies associations, echoes, parallels and contrasts that, for all their sharpness, in the final analysis defy interpretation. The reader’s need to sense the presence of form or aesthetic control is, to give just two examples, satisfied by the way the pampres (vine branches) lead to tuteurs de vigne and the perche à houblon to the beer-swilling Gambrinus (as his name was spelt in the first version of the poem), thereby marking a progression from Grecian Bacchus to a legendary figure associated with foggier northern climes. The poet’s concern with harmony (and counterpoint) becomes ever more apparent as we take note of the proliferation of linked images and references. No constituent is free-standing. As always in Baudelaire’s poetry, each element invites appreciation in its relation to a tightly woven textual whole. If ‘Le Thyrse’ stands out, it is perhaps by virtue of the single-minded intensity with which the poet, more or less explicitly, engages in a dialogue between poetry and its sister arts that is all the more suggestive as a result of his simultaneous retention of certain outward features of the concrete object featured in the poem’s title.

It will be clear that a consideration of La Musique aux Tuileries and ‘Le Thyrse’ in these terms provides scant enlightenment with regard to the question of Baudelaire’s estimation of Manet’s paintings before and after Olympia. Nor does it determine which of the two artistic visions is to be considered dominant in their relationship, least of all with regard to the elastic conception of the ‘peintre de la vie moderne’. What I hope to have provided is a glimpse of the extent to which there were significant aesthetic affinities between poet and painter in the years 1859–64, which, nonetheless, did not exclude on either side an expression of intense individualism. Rather than influence, the phenomenon at work should seemingly be viewed in terms of a profound and extensive example of catalysis, in which the prose poetry and essays on art and aesthetics of the one and the visual art of the other are enriched by the frequent intercourse between them. As such, the phenomenon is something that ultimately evades conceptualization and can only be hinted at. At the same time, the parallel consideration of poem and painting may be said to reinforce appreciation of the way the compositions in question were situated in a context of wider creative activity exemplified in this instance by Liszt and De Quincey, and which might also be thought to include the pervasive, if unspecified, presence of Richard Wagner.Footnote62

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael Tilby

Michael Tilby is a Fellow of Selwyn College, Cambridge. His research has been primarily concerned with the works of Honoré de Balzac, but he has published on a range of other nineteenth-century French authors as well as in the field of literature and the visual arts. He is currently completing three monographs: a revisionist study of the flâneur; a study of the interrelated assessment of Hector Berlioz and Jacques Offenbach by nineteenth-century French writers, critics and journalists; and an analysis of the responses of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Balzac’s Comédie humaine.

Notes

1 In contrast to what he claimed was the prevalent assumption, Proust insisted that the more significant influence was that of Manet on Baudelaire: the conversations the latter enjoyed with the painter in different Paris eateries ‘modifièrent sensiblement sa manière de voir et de juger’ (Proust Citation1897, 128).

2 For an authoritative discussion of these etchings, see Bareau in Cachin, Moffett, and Bareau Citation1983 (156–160).

3 The fact that the portrait remained in Manet’s studio until his death might be taken to indicate Baudelaire’s antipathy towards the canvas. Le Repos. Portrait de Berthe Morisot (1870) was perhaps an oblique means of making amends. See Dolan Citation1997 and Dolan Citation2000.

4 For a stimulating analysis of this poem, see Murphy Citation1995. See also Sarah Gubbins's discussion of ‘La Corde’ in her article in this special issue.

5 See Bareau’s presentation in Cachin, Moffett, and Bareau Citation1983 (60–63).

6 Baudelaire’s subject precluded discussion of Manet as a painter.

7 George Heard Hamilton sees this in terms of ‘paradox’ (Hamilton Citation1986; 62). But see Fried Citation1984 (532) for a sophisticated justification of Baudelaire’s line of defence. See also Pichois’s discussion of Baudelaire’s letter and the rejoinder by Thoré in L’Indépendance belge (June 25, 1864) in Baudelaire’s Correspondance (Citation1973a, 2: 866–867); and Bareau Citation2003 (211–213). For Zola’s response to the charge levelled against Manet, see Zola Citation2021 (481–482). On Manet and Velasquez, see also Guégan Citation2016 (147).

8 See Bareau’s note on this etching in Cachin, Moffett, and Bareau Citation1983 (118).

9 See Crépet Citation1887 (xcv). On the uncertainty surrounding the origin of the copy of Goya’s masterpiece, see Guinard Citation1967 (328).

10 Sensier made a specialism of writing about Millet and the Barbizon School; his study of the life and works of Millet was translated into English and published posthumously in London and New York in 1881.

11 Cited in Clark Citation1984 (296). Yet, as Beatrice Farwell has stated, ‘Baudelaire is the source of Clark’s title. While curiously little is said in the book about Baudelaire’s recommendations of modern life as a subject for art, his evocation in poetry of the evil and corruption in the spirit of modern man hovers as an unseen daemon over the book’s content’ (Farwell Citation1986, 685).

12 The musicality of the first of the lines as quoted is, however, lost as a result of ‘blonde et brune’ being replaced by ‘noire et brune’. The visual femininity of ‘fourrure’ is likewise lost when three lines later ‘caressée’ becomes ‘caressé’. In an entry in his unpublished carnet vert prompted by the showing of Olympia at the Exposition Universelle of 1889, Joris-Karl Huysmans would enthuse: ‘L’Olympia – du Goya transposé par Baudelaire – figure, seins vivants – sa vraie oeuvre – mais c’est lignée de noir – les jolies lignes! La main – cette figure étrange – couleur pas vive – un peu éteinte – roses Goya’ (quoted by Lambert Citation1964, 8, though with the apparent typographical error linée). The notebook, then in Pierre Lambert’s collection, is now MS Lambert 75 in the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal (see Duran Citation2004).

13 Leroy (1812–85) was a ‘paysagiste, pastelliste et graveur à l’eau-forte et auteur dramatique’ who had himself exhibited at the Salon between 1835 and 1861 (Bénézit Citation1960, 5: 536). He is best known for having allegedly coined the term ‘Impressionism’.

14 Bridget Alsdorf states apropos of Ravenel’s article that ‘This was not the first time that Manet and Baudelaire were publicly aligned but it was the first time the association stuck’, and maintains that ‘Ravenel’s extraordinary description is worth revisiting with an eye to its Baudelairean theme’ (Alsdorf Citation2019, 134). Her concern is to focus specifically on Manet’s ‘characterization of Olympia as akin to a fleur du mal and on the role of flower imagery in his account of Manet’s painting as a subversive, “disturbing” female nude’ (145).

15 Hamilton cites in English the relevant portion of Leroy’s sketch (in which the painter Ernest Meissonier’s name is misspelt throughout, as was not uncommon in the artist’s lifetime).

16 In the third instalment of his Salon, Leroy (Citation1864a, 71) delights in the depiction of Baudelaire in Henri Fantin-Latour’s Hommage à Delacroix: ‘J’ai vu avec bonheur figurer au premier rang M. Baudelaire. L’illustre vieillard [Baudelaire was 43], ses beaux cheveux gris rejetés en arrière et découvrant entièrement le grand front sur lequel ont germé les Fleurs du mal, semble darder un regard froid et aigu sur son voisin, M. Champfleury; celui-ci paraît mal à l’aise; on croirait qu’il se sent magnétisé et qu’il craint instinctivement la portée de ce regard. Il a l’air de se dire: ─ je parierais ma plus belle faïence contre une tragédie que Baudelaire me jettaturise au lieu de me rendre hommage./ C’est une erreur; le poète regarde plus haut et doit se répéter à lui-même ces beaux vers inspirés par une femme aimée: … ses baisers [sic]/ Chauds comme le soleil [sic], frais comme les pastèques/ Sont [sic] l’ornement des nuits et des jours glorieux’. These lines are misquoted from ‘Lesbos’, one of the ‘pièces condamnées’. (For a more convincing reading, see Stéphane Guégan: ‘Manet s’y tient debout, entre Champfleury et Baudelaire, comme si Fantin voulait nous dire que le futur peintre d’Olympia eût vocation à les réconcilier par le réalisme dont il avait renouvelé la formule’ (2016, 417).) In the eighth instalment, Leroy (Citation1864b, 79) considers Manet’s Épisode d’une course de taureaux and opines: ‘M. Manet doit être affecté d’une maladie aiguë de la rétine. On ne voit pas ainsi la nature sans une aberration du nerf optique.’ In the thirteenth (Leroy Citation1864c, 85), which features a comic dialogue between La Critique and La Peinture (‘[une] belle dame’), the latter dismisses the same painting out of hand.

17 Both were academicians. Broglie fils was Baudelaire's contemporary and married to a lady famously painted by Ingres.

18 Leduc-Adine comments with regard to this passage: ‘Le refus de la peinture à idées, de la peinture littéraire est une constante de la critique zolienne qui se veut avant tout formaliste’ (Zola Citation1991, 482).

19 Lethbridge notes that the image was given an obscene significance by ‘les contemporains malveillants’ (Zola Citation2021, 485). This was revealed to readers of the original 1866 edition of Les Épaves, in which the anonymous publisher (Auguste Poulet-Malassis) inserted a note attributing these imputations to ‘des critiques d’estaminet: ‘La muse de M. Charles Baudelaire est si généralement suspecte, qu’il s’est trouvé des critiques d’estaminet pour dénicher un sens obscène dans le bijou rose et noir’ (Baudelaire Citation1866, 110).

20 This seems to be an anachronistic allusion to the brasserie Andler in the rue Hautefeuille, the ‘Temple du réalisme’ where Courbet, Proudhon and their political allies congregated, unless it be a reference to the brasserie in the rue des Martyrs frequented by Courbet from 1863.

21 Carrier has rightly described this as ‘an overoptimistic reading of the limited evidence’ (Citation1995; 297).

22 See Castex Citation1969 (74–77), where there is no reflection on the question of whether Baudelaire’s prose poems, the composition of which largely coincided with the period of his friendship with Manet, might reflect his exposure to the latter’s art.

23 There is little documentary evidence on which to base a view of Manet’s appreciation of Baudelaire’s poetry.

24 Nonetheless, as Cachin points out, Manet possessed sixty drawings by Guys (Citation1983, 124). Asselineau highlights ‘Constantin Guys, Rethel & Edouard Manet’ as Baudelaire’s ‘prédilections artistiques’, taking over from Haussoulier, whose talent had been praised in Baudelaire’s Salon de 1845 (Asselineau Citation1869, 17).

25 Baudelaire, Manet and Legros all appear in Fantin-Latour’s Hommage à Delacroix (1864). In a letter of December 6, 1861 to the actor Philibert Rouvière (whom Manet would paint in his role as Hamlet in 1865, though the work was rejected by the Salon jury the following year), Baudelaire describes Legros as ‘un de mes amis’, adding ‘Il est l’auteur de l’Angélus dont j’ai écrit moins de bien encore que j’en pense’ (he had praised it in his Salon de 1859) (Correspondance, Citation1973a, 2: 190). In his anonymous article on Louis Martinet’s show in the Revue anecdotique (January 1–15, 1862), the poet had singled out for praise Legros’s L’Ex-voto and La Vocation de saint François. Legros had dedicated his Esquisses à l’eau-forte ‘à mon ami Baudelaire’ (see Chagniot Citation2011). See also Fairlie (Citation1972) Citation1981 (198–200).

26 For example, Hiddleston suggests that Baudelaire would have been put off by ‘the lack of drama and of social or psychological depth in La Musique aux Tuileries’ (Citation1992, 569). Hiddleston also surmises that for the poet-critic ‘the scandal of La Musique aux Tuileries lay in a sense of disproportion […] “une grande machine”, but without depth of meaning or narration’ (575). See also Hiddleston Citation1984.

27 See also Pichois and Ziegler Citation1987 (429–433).

28 On the modernity of Manet’s scene, see, however, the features singled out by David Scott (Citation2009). Amongst the objects Scott highlights (112) are the buckets and spades in the foreground, though these might also be seen as participating in the interplay of black and white as well as contrasting humorously with the little girls’ pristine white dresses.

29 Lois Boe Hyslop opines: ‘Though [Antonin] Proust maintains that it was the artist who influenced the poet – and to a certain extent he was of course right – there is much to indicate that the opposite was more true’ (1980, 47).

30 Nils Gosta Sandblad (Citation1954) includes Provost’s xylograph as his first illustration. Busch, following Sandblad, notes that it contains ‘a single cast iron chair of the type found in Manet’s painting’ (198), though the chair in question lacks the elaborate decoration of those in La Musique aux Tuileries. Hyslop (Citation1980, 50) notes that the illustration was ‘much admired’ by Baudelaire and suggests that the poet may have had it in mind when in ‘Les Veuves’ he describes ‘the lonely widow listening to the military band in the gardens’ (51).

31 The boisterous behaviour of the children in Guérard’s lithograph, together with their domination of the pictorial space, is far removed from La Musique aux Tuileries. Provost’s positioning of a young girl in the foreground seems much more likely to have held Manet’s attention. On his xylograph in relation to La Musique aux Tuileries, see the perceptive comments by Green (Citation2007, 31–32).

32 A sketch reproduced by Busch (Citation2017, 196) is dated 1867 and would seem to be a preparatory sketch for Menzel’s painting based on a less detailed entry in his sketchbook or drawn entirely from memory while profiting from his awareness of Manet’s painting.

33 Cachin, Moffett and Bareau (Citation1983, 123) traces the uncertainty surrounding her identification to the Manet scholars Adolphe Tabarant (Loubens) and Julius Meier-Graefe (Offenbach). Few images of Mme Offenbach from the period survive. Any hope that Degas’s double-portrait of Mme Lisle and Mme Loubens (Art Institute of Chicago), which has been dated to 1869–72, together with the separate charcoal and pastel studies of the two women (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), would provide a solution seems forlorn, especially since it is Mme Lisle whose seated pose is closer to that of Manet’s figure, while Mme Loubens as finally depicted bears scant facial resemblance to her namesake in the study. Nor is identification aided by the discovery that Berthe Morisot took umbrage one evening when the ‘very intelligent’ Degas deserted her ‘to pay compliments to two silly women’, as she considered Lisle and Loubens to be (Boggs Citation1962, 25). Both Loubens and Lisle formed part of Manet’s social circle.

34 Five letters to Hippolyte Lejosne are included in Pichois’s edition of Baudelaire’s correspondence. Six letters Lejosne wrote to the poet in 1865 are included in Baudelaire (Lettres, Citation1973b, 209–217). (These are presumably the letters offered at auction in Paris by Gros and Delettrez on December 1, 2009.) An unpublished letter from Baudelaire to Lejosne dated December 26, 1866 was sold by Sotheby’s Paris on October 9, 2018 (lot 46).

35 In a letter to Baudelaire of [February] 14, 1865, Manet writes: ‘Le brave commandant, qui me semble un peu cornichon [,] continue à soigner sa terrible femme, j’espère cependant pour notre ami qu’il est dupe et non pas complice de tant de comédies’ (Baudelaire, Lettres, Citation1973b, 230).

36 For discouragement from assuming that this dark shape should be seen as a cat, I am grateful to Therese Dolan, who suggests that it is more plausibly seen as a lap dog. The fact remains that the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York) possesses a small 1861 graphite sketch by Manet of a cat that might be thought to look forward to La Musique aux Tuileries and is listed in the museum catalogue as A Cat Resting on All Fours, Seen from Behind ().

37 Green has duly maintained that the blague is central to La Musique aux Tuileries, seeing it as ‘manifest in the witty contrasts of facture’ (Citation2007, 30).

38 This is not to deny that, as Green observes, the ‘extreme summariness’ of Mme Lejosne’s face forms a (characteristic) juxtaposition with the ‘spotting on the veil belonging to Mme Offenbach/ Loubens’ (Citation2007, 30).

39 Singletary plausibly attributes the ‘uneasy and idiosyncratic amalgam of realism and romanticism […] that will be a persistent thread throughout Manet’s career to his contact with […] Baudelaire’ (Citation2012, 51).

40 The Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky’s concept of ostranenie would seem applicable.

41 See Baudelaire’s take on the frac in Le Salon de 1846 (Citation1992, 154), recalled by Jaap Harskamp (Citation2001, 94–95). Harskamp notes the poet-critic’s ‘considerable delight in turning the argument about l’habit noir on its head’ (95).

42 With reference to Olympia, Clark states that ‘in order that the painted surface appear as it does […], the self-evidence of seeing […] had to be dismantled, and a circuit of signs put in its place’ (Citation1984, 139).

43 It might therefore be argued that the often remarked upon absence of a literal music performance is an irrelevance. The apparent resemblance to a photograph is stimulated by the impression that the scene has been captured at a precise moment, thereby implying an awareness of reality in perpetual flux. Any impression of a snapshot is, however, in tension with the non-naturalistic elements of the scene and the abiding sense of artifice.

44 Inspired by the fact that ‘Offenbach’s head is depicted with only one eye visible, its darkness almost completely filling the lens of his glasses’, Dolan suggests perceptively that this is an allusion to the composer’s reputation for the ‘evil eye’ (Citation2013, 200).

45 Bernstein’s detailed analysis of the 1869 ‘Le Thyrse’, for example, is less applicable to the original version (Citation1998, 182ff.).

46 On the relations between poet and musician, see Bandy Citation1938 and Bohac Citation2011. The sole extant letter from Baudelaire to Liszt dates from 1861, before the two men had met.

47 In the ‘exorde’ to the lecture on Delacroix he gave in Brussels in 1864 (Baudelaire Citation1992, 433).

48 Published in four instalments in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine.

49 For an admirable unravelling of this confusion, see Metzidakis and Clemente Citation2010. See also James Citation1995 (127). ‘De Quincy’ [sic] was one of those Baudelaire stipulated should receive a copy of the 1857 Fleurs du Mal (Baudelaire, Citation1973a, 1: 406–407).

50 Eigeldinger (Citation1975) nonetheless thinks it unlikely that Baudelaire knew Musset’s article. On Musset’s adaptation of the original, see Levin Citation1998 (56–57) and Gamble Citation2017. For a formalist analysis of ‘Le Thyrse’ from a different perspective, see Eigeldinger Citation1976.

51 In L’Anglais mangeur d’opium, Musset retains the essential information regarding De Quincey’s delight in Grassini’s performances [at the King’s Theatre] in London [in 1805] (Musset Citation1828, 107). Daniel O’Quinn (Citation2004) has identified from press reviews the elusive ‘Andromache weeping over the Tomb of Hector’ to which De Quincey refers as an interlude scene ‘composed expressly for Grassini by Zingarelli’. See also Burgh Citation1814 (3: 356) and Stanyon Citation2020 (186). The evidence for Baudelaire’s awareness of L’Anglais mangeur d’opium is strong. Jacques Crépet (Baudelaire Citation1928, 292) was the first to observe that Alexandre Brierre de Boismont reproduced four pages of Musset’s adaptation in a work of 1845 that Baudelaire came to know well: Des hallucinations. It is not clear whether at this point either Boismont, who did not name the English writer, or Baudelaire was aware of the identity of A.D.M. The pages extracted from the latter’s work survived in the otherwise much revamped third edition of Des hallucinations published in 1862, but the expanded bibliographical footnote on this occasion identified both De Quincey and Musset, and, moreover, recommended Baudelaire’s ‘Enchantements et tortures d’un mangeur d’opium’, which had been published in the pages of the Revue contemporaine in January 1860. See also Hughes Citation1939 (575) and Baudelaire 1976 (38). Starkie (Citation1957, 372) refers to a letter Poulet-Malassis wrote to Spoelberch de Lovenjoul in November 1864 in which he claimed that Baudelaire, at work on Les Paradis artificiels at the time, had come across a copy of L’Anglais mangeur d’opium for sale on the banks of the Seine, but, disdainful of the treatment De Quincey’s work had received, and failing to identify A.D.M., declined to acquire it. The letter had been published in an obscure magazine (Le Goéland) by Pichois in 1952 and was later reproduced in Pichois (Citation1967).

52 ‘De Quincey […] compare, en un endroit, sa pensée à un thyrse, simple bâton qui tire toute sa physionomie et tout son charme du feuillage compliqué qui l’enveloppe’ (Baudelaire Citation1975–Citation76, 1: 444).

53 ‘[C]ette pensée est le thyrse dont [De Quincey] a si plaisamment parlé, avec la candeur d’un vagabond qui se connaît bien’ (Baudelaire 1975–76, 1: 515). In the version that appeared in the Revue contemporaine, Baudelaire had evoked ‘la candeur d’un digressioniste’ (1401).

54 It is in the opening line of ‘Les Petites Vieilles’ (1859) that ‘sinueux’ makes its only appearance in Les Fleurs du Mal.

55 This passage receives significant attention in Bohac (Citation2011), though with different emphases. It should be noted that Liszt would substantially rework his text for the 1881 Leipzig edition.

56 As does Gautier (Citation1845, 244). The latter’s travelogue, which, suggestively in the present context, was republished in 1859, contains numerous other descriptions of arabesques. On Gautier and the arabesque (‘l’emblème de la fantaisie, de la libre imagination’), see Bohac Citation2011 (94). On Baudelaire and the arabesque, see Labarthe Citation1999 (367ff, 525), and Klein Citation1970. See, more generally, Cabanès and Saïdah Citation2003 (passim).

57 Pichois amply documents Baudelaire’s attraction to Bohemian culture in his notes to this poem (Baudelaire Citation1975–Citation76, 1: 864–865). Contemporary with his exchanges with Manet and Liszt are the references to the figure of the Bohemian in ‘La Corde’, where the artist reveals that he had partly painted the boy ‘en petit bohémien’ (Baudelaire Citation1975–Citation76, 1: 329), and in ‘Les Bons Chiens’, where the ‘bohémien’ is grouped with the ‘pauvre’ and the ‘histrion’ in what might be mistaken for a conscious allusion to Manet’s œuvre (Baudelaire Citation1975–Citation76, 1: 361). Bohac identifies an important parallel between ‘Les Vocations’, the poem positioned between ‘La Corde’ and ‘Le Thyrse’, and Liszt’s Des Bohémiens in respect of boyhood ambitions to run away to join the Romanies (2011, 90).

58 Marilyn L. Brown has identified the subject of Manet’s Le Vieux Musicien (1862) as a well-known Bohemian street musician (see Brown Citation1978). Brown also adduces a different passage from Des Bohémiens in support of her claim that Liszt’s vision of Bohemian music reveals ‘striking parallels in music for Manet’s own style in painting’ (Citation1978, 85).

59 As Gautier reminds his reader (Citation1845, 34 and 122).

60 See Dolan Citation2013 (190), citing a review by Henri Blanchard of Offenbach’s Pépito (Revue et gazette musicale, October 30; 1853).

61 See Hooker Citation2013 (36).

62 This article is an expanded version of a paper delivered at a session commemorating Barbara Wright at the 2021 Nineteenth-Century French Studies colloquium in Washington D.C. I am indebted to the panel organizer Therese Dolan for her willingness to read my paper on my behalf.

References

- Alsdorf, Bridget. 2019. “Manet’s Fleurs du Mal.” In Manet and Modern Beauty: The Artist’s Last Years, edited by Alan Scott, Emily A. Beenie, and Gloria Groom, 129–146. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

- Asselineau, Charles. 1869. Charles Baudelaire, sa vie et son œuvre, avec portraits. Paris: Lemerre.

- Bandy, W. T. 1938. “Baudelaire and Liszt.” Modern Language Notes 53 (8): 584–585. doi:10.2307/2912962.

- Banville, Théodore de. 1842. Les Cariatides. Paris: Pilout.

- Bareau, Juliet Wilson. 2003. “Manet and Spain.” In Manet/ Velasquez. The French Taste for Spanish Painting, edited by Gary Tinterow, and Geneviève Lacambre, 203–257. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Baudelaire, Charles. 1866. Les Épaves. Amsterdam [Brussels]: A l’Enseigne du coq [Poulet-Malassis].

- Baudelaire, Charles. 1928. Les Paradis artificiels. La Fanfarlo. Edited by Jacques Crépet. Paris: Conard.

- Baudelaire, Charles. 1973a. Correspondance. Edited by Claude Pichois. Paris: Gallimard. Pléiade.

- Baudelaire, Charles. 1973b. Lettres à Baudelaire. Edited by Claude Pichois. Neuchâtel: A La Baconnière.

- Baudelaire, Charles. 1975–76. Œuvres complètes. Edited by Claude Pichois. 2 vols. Paris: Gallimard, Pléiade.

- Baudelaire, Charles. 1992. Critique d’art, suivi de critique musicale. Edited by Claude Pichois and Claire Brunet. Paris: Gallimard.

- Bénézit, E[mmanuel]. 1911–23, 1960. Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs de tous les temps et de tous les pays. Paris: Gründ.

- Bernstein, Suzanne. 1998. Virtuosity of the Nineteenth Century. Performing Music and Language in Heine, Liszt and Baudelaire. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Boggs, Jean Sutherland. 1962. Portraits by Degas. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Bohac, Barbara. 2011. “Baudelaire et Liszt. Le génie de la rhapsodie.” Romantisme 151: 87–99. doi:10.3917/rom.151.0087.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2017. Manet. A Symbolic Revolution. Translated by Peter Collier and Margaret Rigaud-Drayton. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Brown, Marilyn R. 1978. “Manet’s Old Musicians: Portrait of a Gypsy and Naturalist Allegory.” Studies in the History of Art 8: 77–87.

- Burgh, A. M. 1814. Anecdotes of Music, Historical and Biographical. London: Longman.

- Busch, Werner. 2017. Adolph Menzel. The Quest for Reality. Translated by Carola Kleinstück-Shulman. Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute.

- Cabanès, Jean-Louis, and Jean-Pierre Saïdah, eds. 2003. La Fantaisie Post-Romantique. Toulouse: Presses universitaires du Mirail.

- Cachin, Françoise, Charles S. Moffett, and Juliet Wilson Bareau. 1983. Manet 1832–1883. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux.

- Carrier, David. 1995. “Baudelaire’s Philosophical Theory of Beauty.” Nineteenth-Century French Studies 27 (3–4): 382–402.

- Castex, Pierre-Georges. 1969. Baudelaire, Critique d’art. Paris: SEDES.

- Chagniot, Claire. 2011. “La Dédicace à Baudelaire des Esquisses à l’eau-forte ou le ‘moment Baudelaire’ d’Alphonse Legros, 1859–1862.” L’Année Baudelaire 15: 43–59.

- Clark, T. J. 1984. The Painting of Modern Life. Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Crépet, Eugène. 1887. “Étude biographique.” In Charles Baudelaire, Œuvres posthumes et correspondances inédites, ix–civ. Paris: Quantin.

- De Quincey, Thomas. 1845. “Suspiria de Profundis: Being a Sequel to the Confessions of an English Opium-Eater.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 353 (57): 269–285.

- Dolan, Therese. 1997. “Skirting the Issue: Manet’s Portrait of Baudelaire’s Mistress Reclining.” The Art Bulletin 79 (4): 611–629. doi:10.2307/3046278.

- Dolan, Therese. 2000. “Manet, Baudelaire and Hugo in 1862.” Word and Image 16 (2): 145–162. doi:10.1080/02666286.2000.10435679.

- Dolan, Therese. 2013. Manet, Wagner, and the Musical Culture of Their Time. London: Routledge.

- Duran, Sylvie. 2004. “Étude et projet d’édition du “Carnet vert” de Joris-Karl Huysmans (PhD diss., Université de Grenoble III). Lille: Lille-Thèses. Université de Lille III.

- Eigeldinger, Marc. 1975. “À propos de l’image du thyrse.” Revue d’histoire littéraire de la France 75 (1): 110–112.

- Eigeldinger, Marc. 1976. “‘Le Thyrse’, lecture thématique.” Études baudelairiennes 8: 172–183.

- Fairlie, Alison. (1972) 1981. “Some Aspects of Expression in Baudelaire’s Art Criticism.” In Imagination and Language. Collected Essays on Constant, Baudelaire, Nerval and Flaubert, edited by Malcolm Bowie, 176–215. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Farwell, Beatrice. 1986. “Review of T. J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life.” The Art Bulletin 68 (4): 684–687. doi:10.1080/0004/00043079.1986.10788393.

- Fried, Michael. 1984. “Painting Memories: On the Containment of the Past in Baudelaire and Manet.” Critical Inquiry 10 (3): 510–542. doi:10.1086/448260.

- Gamble, Donald M. 2017. “Serious Mistranslation. The Significance of Alfred de Musset’s Version of Thomas de Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater.” In Le Comparatisme comme approche critique, edited by Anne Tomiche, Vol. 4, 257–270. Paris: Classiques Garnier.

- Gautier, Théophile. 1845. Voyage en Espagne. Paris: Charpentier.

- Green, Anna. 2007. French Paintings of Childhood and Adolescence 1848–1886. London: Routledge.

- Guégan, Stéphane. 2016. “Edouard Manet.” In L’Œil de Baudelaire, 146–151. Paris: Musée de la Vie romantique.

- Guinard, Paul. 1967. “Baudelaire, le Musée espagnol et Goya.” Revue d’histoire littéraire de la France 67 (2): 310–328.

- Hamilton, George Heard. (1954) 1986. Manet and his Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Harskamp, Jaap. 2001. “The Artist and the Swallow-Tail Coat: Heine, Baudelaire, Manet and Modernism.” Arcadia 36 (1): 89–99. doi:10.1515/arca.2001.36.1.89.

- Hiddleston, J. A. 1984. “Baudelaire, Manet et ‘La Corde’.” Bulletin Baudelairien 19 (1): 7–11.

- Hiddleston, J. A. 1992. “Baudelaire, Manet, and Modernity.” Modern Language Review 87 (3): 567–575. doi:10.2307/3732920.

- Hooker, Lynn M. 2013. Redefining Hungarian Music from Liszt to Bartók. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hughes, Randolph. 1939. “Vers la contrée du rêve. Balzac, Gautier et Baudelaire disciples de Quincey.” Mercure de France 293: 545–593.

- Hyslop, Lois Boe. 1980. Baudelaire, Man of his Time. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- James, Tony. 1995. Dream, Creativity and Madness in Nineteenth-Century France. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Klein, Richard. 1970. “Straight Lines and Arabesques: Metaphors of Metaphor.” Yale French Studies 45: 64–86. doi:10.2307/2929554.

- Labarthe, Patrick. 1999. Baudelaire et la tradition de l’allégorie. Geneva: Droz.

- Lambert, Pierre. 1964. “Le Carnet secret de Huysmans.” Le Figaro littéraire 950 (July 2–7): 1, 8, 19.

- Leroy, Louis. 1864a. “Salon de Paris III.” Le Charivari, May 11.

- Leroy, Louis. 1864b. “Salon de Paris VIII.” Le Charivari, May 25.

- Leroy, Louis. 1864c. “Salon de Paris XIII.” Le Charivari, June 10.

- Leroy, Louis. 1864d. “Salon de Paris XV.” Le Charivari, June 15.

- Leroy, Louis. 1868. “La Grande Trahison des maréchaux de Courbet.” Le Journal amusant 3-4, May 23.

- Levin, Susan M. 1998. The Romantic Art of Confession: De Quincey, Musset, Sand, Lamb, Hogg, Frémy, Soulié, Janin. Columbia, SC: Random House.

- Liszt, Franz. 1859. Des Bohémiens et de leur musique en Hongrie. Paris: La Librairie nouvelle.

- Mack, Gerstle. 1951. Gustave Courbet. New York: Knopf.

- Metzidakis, Stamos, and Marie-Christine Clemente. 2010. “Au cœur de l’esthétique baudelairienne. Thyrse et caducée.” Romanic Review 101 (4): 741–759. doi:10.1215/26885220-101.4.741.

- Murphy, Steve. 1995. “Haunting Memories: Inquest and Exorcism in Baudelaire’s ‘La Corde’.” Dalhousie French Studies 30: 65–91.

- Musset, Alfred de. 1828. L’Anglais mangeur d’opium. Paris: Mame and Delaunay-Vallée.

- O’Quinn, Daniel. 2004. “Ravishment Twice Weekly: De Quincey’s Opera Pleasures.” Romanticism on the Net 34–35. doi:10.7202/009436ar.

- Pichois, Claude. 1967. “Autour des ‘Paradis artificiels': Baudelaire, Musset et de Quincey.” In Baudelaire. Études et témoignages, 141–144. Neuchâtel: La Baconnière.

- Pichois, Claude, and Jean Ziegler. 1987. Baudelaire. Paris: Julliard.

- Proust, Antonin. 1897. “Edouard Manet (Souvenirs).” La Revue blanche 12: 125–135.

- Rebeyrol, Philippe. 1949. “Baudelaire et Manet.” Les Temps Modernes 48: 707–725.

- Sandblad, Nils Gosta. 1954. Manet. Three Studies in Artistic Conception. Lund: Gleerup.

- Scott, David. 2009. “Generical Intersections in Nineteenth-Century French Painting and Literature: Manet’s La Musique aux Tuileries and Baudelaire’s Petits Poèmes en prose.” In Textual Intersections. Literature, History and the Arts in Nineteenth-Century Europe, edited by Rachel Langford, 107–117. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Singletary, Suzanne. 2012. “Manet and Whistler: Baudelairean Voyage.” In Perspectives on Manet, edited by Therese Dolan, 49–70. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Sollers, Philippe. [2011] 2013. L’Eclaircie. Paris: Gallimard.

- Stanyon, Miranda. 2020. “Counterfeits, Contraltos and Harmony in De Quincey’s Sublime.” In Music and the Sonorous Sublime in European Culture, 1680–1880, edited by Sarah Hibberd, and Miranda Stanyon, 177–199. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Starkie, Enid. 1957. Baudelaire. London: Faber.

- Wright, Barbara. 1998. “A Turning Point in Nineteenth-Century France.” In The Process of Art. Studies in Nineteenth-Century Literature and Art Offered to Alan Raitt, edited by Michael Freeman, Elizabeth Fallaize, Jill Forbes, Toby Garfitt, and Roger Pearson, 204–214. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Zola, Emile. 1991. Écrits sur l’art. edited by Jean-Pierre Leduc-Adine. Paris: Gallimard.

- Zola, Emile. 2021. Critique littéraire et artistique, I: Ecrits sur l’art. edited by Robert Lethbridge. Paris: Classiques Garnier.

Appendix

PETITS POËMES EN PROSE

LE THYRSE

A Franz Liszt

Qu’est-ce qu’un thyrse? Selon le sens moral et poétique, c’est un emblème sacerdotal dans la main des prêtres ou des prêtresses célébrant la divinité dont ils sont les interprètes et les serviteurs. Mais physiquement, ce n’est qu’un bâton, un pur bâton, perche à houblon, tuteur de vigne, sec, dur et droit. Autour de ce bâton, dans des méandres capricieux, se jouent et folâtrent des tiges et des fleurs, celles-ci sinueuses et fuyardes, celles-là penchées comme des cloches ou des coupes renversées. Et une gloire étonnante jaillit de cette complexité de lignes et de couleurs, tendres ou éclatantes. Ne dirait-on pas que la ligne courbe et la spirale font leur cour à la ligne droite et dansent autour dans une muette adoration? Ne dirait-on pas que toutes ces corolles délicates, tous ces calices, explosions de senteurs et de couleurs, exécutent un mystique fandango autour du bâton hiératique? Et quel est, cependant, le mortel imprudent qui osera décider si les fleurs et les pampres ont été faits pour le bâton, ou si le bâton n’est que le prétexte pour montrer la beauté des pampres et des fleurs?

Le thyrse est la représentation de votre étonnante dualité, maître puissant et vénéré, cher Bacchant de la Beauté mystérieuse et passionnée. Jamais nymphe exaspérée par l’invincible Bacchus ne secoua son thyrse sur les têtes de ses compagnes affolées avec autant d’énergie et de caprice que vous agitez votre génie sur les cœurs de vos frères.

Le bâton, c’est votre volonté, droite, ferme et inébranlable; les fleurs, c’est la promenade de votre fantaisie autour de votre volonté; c’est l’élément féminin exécutant autour du mâle ses prestigieuses pirouettes. Ligne droite et ligne arabesque, intention et expression, roideur de la volonté, sinuosités du verbe, unité du but, variété des moyens, amalgame tout-puissant et indivisible du génie, quel analyste aura le détestable courage de vous diviser et de vous séparer?

Cher Liszt, à travers les brumes, par-delà les fleuves, par-dessus les villes où les pianos chantent votre gloire, où l’imprimerie traduit votre sagesse, en quelque lieu que vous soyez, dans les splendeurs de la Ville Éternelle, ou dans les brumes des pays rêveurs que console Gambrinus, improvisant des chants de délectation ou d’ineffable douleur, ou confiant au papier vos méditations abstruses, chantre de la Volupté et de l’Angoisse éternelles, philosophe, poëte et artiste, je vous salue en l’immortalité!

(First published text of the poem as it appeared in the Revue nationale et étrangère, politique, scientifique et littéraire, December 13, 1863. See facsimile version at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6350570p/f346.image)