ABSTRACT

The UK prison system offers a medical treatment pathway for people suffering from problematic sexual arousal (PSA) who have committed a sexual offence(s). The two main medications are Anti-androgens (AAs) and Selective-Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs). Currently, evidence of the effectiveness of SSRIs is not sufficiently robust for them to be licensed in the UK for that purpose. Instead, SSRIs are prescribed ‘off-label’, and physicians must adhere to additional obligations in prescribing them. Yet SSRIs have fewer side effects than AAs and may be a better treatment option for many patients. The present study examined the effectiveness of AAs and SSRIs in incarcerated individuals with PSA (n = 77); the unmedicated comparison group (n = 58) resided at the same prison which houses people convicted of a sexual offence. Both medicated groups demonstrated reduced levels of PSA 3 months post-baseline; the comparison group did not. The findings provide evidence for the effectiveness of SSRIs in reducing PSA. The authors argue a randomised control trial is required to underpin the use of SSRIs in treating PSA and (potentially) its subsequent licensing. The latter would enable wider prescription in prison and community and make a substantive contribution to the prevention of sexual abuse.

Introduction

Problematic sexual arousal (PSA) – also referred to as, e.g. sexual preoccupation (Mann et al., Citation2010), sexual compulsivity (Kalichman et al., Citation1994), nymphomania (Groneman, Citation1994), hypersexual disorder (Krueger & Kaplan, Citation2002), or sexual addiction (Carnes, Citation2001) is one of the most common motivators underpinning sexual offending and reoffending (Kingston & Bradford, Citation2013; L. E. Marshall & Marshall, Citation2001; Seto et al., Citation2023). PSA in the current study is defined as intense and frequent sexual thoughts, physiological arousal, urges, and behaviours, that are distressing and difficult to manage, and which may be paraphilic in nature. While some individuals who commit a sexual offence have similar levels of PSA compared to men who have committed nonsexual offences, or representative community samples (Blanchard, Citation1990, Carnes, Citation1994; L. E. Marshall et al., Citation2008, Citation2009) there exists a subset of individuals convicted for sexual offences who experience significantly higher levels of PSA (Ryan et al., Citation2017), positioning PSA as a noteworthy area of interest in the field of treating and preventing sexual offending.

Inability to control problematic sexual behaviours is a serious health concern reflected in the inclusion of Compulsive Sexual Behaviour Disorder (CSBD) – an impulse control disorder characterised by a persistent inability to control intense and repetitive sexual impulses or urges, resulting in recurring sexual behaviour – in the ICD-11 (2019; Balon & Briken, Citation2021; Briken, Citation2020; Kraus et al., Citation2018). Of note, paraphilic behaviour, such as a sexual offence against a child, is an exclusion criterion for CSBD. Our definition of PSA includes paraphilic behaviour. Furthermore, CSBD specifically refers to difficulties with controlling sexual urges, while our definition of PSA focuses both on the distress that an individual experiences as a consequence of enacting behaviours that are related to their PSA, together with managing the consequences of such behaviours. As such, the current definition more closely resembles ‘hypersexual disorder’, defined as ‘a repetitive and intense preoccupation with sexual fantasies, urges, and behaviors, leading to adverse consequences and clinically significant distress or impairment’ (Kafka, Citation2010, p. 379).

PSA is associated with a number of adverse outcomes for an individual’s wellbeing, including higher levels of anxiety, depression, stress, loneliness, shame and hopelessness and difficulty coping with these (Reid, Citation2007; Reid et al., Citation2014; Rooney et al., Citation2018; Walton et al., Citation2017), diagnosable mood disorders (Bancroft, Citation2008; Garcia & Thibaut, Citation2010; Reid et al., Citation2014), interpersonal problems (Sutton et al., Citation2015), eating disorders (Karila et al., Citation2014; Opitz et al., Citation2009), alcohol and substance abuse (Karila et al., Citation2014; Opitz et al., Citation2009; Rooney et al., Citation2018; Sutton et al., Citation2015) and gambling and compulsive buying (Kafka, Citation2010; Odlaug et al., Citation2013). In addition, PSA can impact upon wider aspects of an individual’s life, contributing to the breakdown of relationships (Paunović & Hallberg, Citation2014; Sutton et al., Citation2015), the loss of employment (Paunović & Hallberg, Citation2014; Sutton et al., Citation2015), financial loss (Reid et al., Citation2012; Sutton et al., Citation2015) and lower life satisfaction (Brody & Costa, Citation2009; Långström & Hanson, Citation2006). There are also a number of physical health concerns related to PSA and hyper-sexual behaviours, including genital soreness (Hallikeri et al., Citation2010), physical injury (Carnes, Citation1991), premature ejaculation (Sutton et al., Citation2015), reduced sperm quality (Zimmer & Imhoff, Citation2020). The increased frequency of unprotected sex with multiple partners can also lead to other problems such as the increased likelihood of sexually transmitted disease and unplanned parenthood (Grov et al., Citation2010; Kafka, Citation2010; Långström & Hanson, Citation2006; Parsons et al., Citation2012; Rooney et al., Citation2018; Yoon et al., Citation2016).

When left untreated, PSA can present multiple other challenges, being implicated as a significant risk factor for first-time sexual offending (Finkelhor, Citation1984; Seto, Citation2019; Ward & Beech, Citation2017), with some individuals who are unable to manage their arousal engaging in inappropriate or illegal behaviours, such as sexual harassment (Reid et al., Citation2009). For individuals convicted of a sexual offence, PSA may affect their ability to focus on and therefore progress in offending behaviour interventions (e.g. Akerman, Citation2008; W. L. Marshall, Citation2006) and has been postulated as an important factor in psychological intervention ineffectiveness (Grubin, Citation2018). Additionally, PSA, or more specifically sexual preoccupation, has been reported as a strongly present criminogenic need in people serving custodial sentences for a sexual conviction (Seto et al., Citation2023) and is recognised as a crucial risk factor for and significant predictor of sexual (as well as violent and general) recidivism (Gregório Hertz et al., Citation2022; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, Citation2004, Citation2005; Mann et al., Citation2010). Addressing PSA in treatment, together with individual factors such as personality, psychopathology, and substance misuse problems, can have far-reaching implications both in terms of reducing the likelihood of reoffending and the long-lasting impact on both psychological and physical health of victims of sexual abuse (Hamilton-Giachritsis et al., Citation2017; Ullman et al., Citation2013).

At present, the primary international risk reducing intervention approach for people with a sexual conviction is psychological, most often Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (Grubin, Citation2021; Hanson et al., Citation2002; Rocha & Valença, Citation2023; Weiss, Citation2017). In the United States (US), many CBT programmes employ the RNR model (Bonta & Andrews, Citation2007) which addresses dynamic risk factors such as substance abuse and criminal attitudes during individual or group-based therapy. Additionally, individuals with sexual convictions must participate in the Containment Model (English, Citation1998), which integrates aspects of treatment alongside supervision, risk assessment and management. Pharmacological treatment options are available in the US, usually for the treatment of individuals with both sexual convictions and diagnosed paraphilias. These vary in legal provision and implementation across states (McGrath et al., Citation2010) but typically are used substantially less than psychological interventions (Schmucker & Lösel, Citation2017). Across Canada, the primary treatment options for people who have been convicted of a sexual offence are psychological intervention, and Prenzler et al. (Citation2023) identified Canada as offering some of the most successful psychological programmes in their international evaluation of treatment programmes for people who have committed a sexual offence. Canada has a range of clinics to assess and treat people, including the Sexual Behaviours Clinic (SBC). The SBC offers specialist treatment tailored to individual needs (Murphy & Fedoroff, Citation2017) and offers both primary and secondary prevention services, using both psychological and medical treatments.

Treatment options across Europe also rely heavily on psychological interventions (Klapilová et al., Citation2019) although pharmacological treatments are increasingly used alongside these. Pharmacological treatments are almost always on a voluntary basis (Turner et al., Citation2017), other than in Poland and Macedonia, where courts can mandate medical treatment for specific sexual convictions (Koshevaliska, Citation2014; McAlinden, Citation2012). Using psychological interventions as treatment for individuals with sexual convictions is supported by empirical evidence (Barros et al., Citation2022; Schmucker & Lösel, Citation2017) but encounters challenges in the context of PSA due to its limitation in addressing PSA specifically (Marques et al., Citation2005; von Franqué et al., Citation2015).

In the UK, only one intervention (Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service’s [HMPPS] Healthy Sex Programme [HSP]) directly addresses offence-related sexual interests (such as a sexual interest in children) and teaches psychological skills for managing problematic sexual thoughts including those related to sexual preoccupation. The only treatment evaluation study provides mixed evidence as to the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing the level of risk (Freel & Wakeling, Citation2023). Importantly, the Healthy Sex Programme is restricted to those with a persistent offence-related sexual interest. Therefore, if an individual’s PSA is more general (i.e. it is not offence related), they do not meet the criteria for the intervention, and there are no other psychological interventions available to them that have been designed to address their PSA.

To address this gap in the appropriate treatment of PSA in the UK, HMPPS introduced medication as a treatment pathway to manage PSA. In 2007, they facilitated a pilot trial of this novel pathway (Medication to Manage Sexual Arousal; MMSA), which is ongoing. Currently, three types of medication are utilised within the UK prison estate: Anti-Androgens (AAs; Cyproterone Acetate [CPA]), Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonists (GnRH Agonists; Triptorelin) and Selective-Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs; Fluoxetine/Paroxetine).

Both AAs and GnRH Agonists lower testosterone, which in turn reduces hypersexuality and sexual preoccupation (J. M. Bradford & Pawlak, Citation1993; Thibaut et al., Citation2010, Citation2020). For example, CPA acts primarily as an androgen antagonist binding competitively with testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) receptors, including those in the testes. The additional gonadotropic effects of CPA prevent the compensatory increase in gonadotrophins that would otherwise arise following the testosterone reduction via the feedback loop of the hypothalamic pituitary gonadal axis. Testosterone is reduced to pre-pubescent levels in around 5 days (Brotherton, Citation1974). The anti-androgen action of CPA additionally leads to atrophy of Leydig cells in the testes but on cessation there is evidence of recovery over time (Brotherton, Citation1974; Thibaut et al., Citation2010). The most common side effect of CPA is gynecomastia (in about 20% of cases) but there is evidence that this can be prevented with a single dose of radiation (Eriksson & Eriksson, Citation1998). A rare (0.5%) but serious effect is hyperplasia or adrenal insufficiency (Heinemann et al., Citation1997). Meningioma is also a possible effect, with one paper reporting an incidence rate of 60 per 100,000 person-years as compared to seven in non-users (Gil et al., Citation2011; see also Thibaut et al., Citation2020).

SSRIs are used ‘off-label’ in the treatment of PSA in the UK and internationally (Jannini et al., Citation2022; Turner et al., Citation2017) with several theories postulated for the mechanism of effect. Serotonin has been shown to increase sexual satiety, reduce libido, and impede erection and ejaculation (Montejo et al., Citation2001; Thibaut et al., Citation2010) and so inhibits sexual activity, perhaps via the anterior lateral hypothalamus (LHA; Lorrain et al., Citation1997). Additionally, a serotonin-modulated reduction in motivation towards sexual activity has also been proposed via serotonergic inhibition of the lateral hypothalamus, leading to inhibition of dopaminergic mesolimbic motivational pathways (Lorrain et al., Citation1999). Other mechanisms of action have been theorised as reductions in compulsivity and/or impulsivity and SSRIs are reported to be especially effective in treatment of PSA in patients with obsessive-compulsive sexual behaviour (Beech & Mitchell, Citation2005; J. M. Bradford, Citation2001; Briken et al., Citation2003; Guay, Citation2009; Jordan et al., Citation2011; Turner & Briken, Citation2021). Those with PSA comorbid with affective diagnosis such as depression and anxiety have also been found to benefit most from SSRI treatment (M. P. Kafka & R. A. Prentky, Citation1992). Effects of SSRIs on PSA are seen within 2–4 weeks (Hill et al., Citation2003). Side effects of SSRIs are less severe than those of CPA and Triptorelin, with the most reported being weight gain and drowsiness (Cascade et al., Citation2009). Other common side effects include restlessness, anxiety, decreased sleep, nausea, and decreased appetite (Carvalho et al., Citation2016; Cascade et al., Citation2009; Hu et al., Citation2004). More serious but rare effects include hepatocellular damage and very rarely hyponatremia with the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (Moret et al., Citation2009).

Research (including case studies, observational studies, retrospective studies, and randomised controlled trials [RCTs]) has previously indicated that testosterone-lowering medication (AAs and GnRH Agonists) can be effective in reducing sexual urges and hypersexual behaviours in those with paraphilic and other sexual disorders (Darjee & Quinn, Citation2020; Sauter et al., Citation2020; Thibaut et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, testosterone-lowering medication has been suggested to reduce the risk of reoffending, especially when combined with psychological intervention (Kaplan & Krueger, Citation2010; Lösel & Schmucker, Citation2005), with meta-analyses finding medium effect sizes (Hall, Citation1995; Lösel & Schmucker, Citation2005). Guay (Citation2009) and Grubin (Citation2008) therefore postulated a promising role for these medications in addressing PSA with individuals convicted of a sexual offence.

More recently, Sauter et al. (Citation2020) demonstrated that while psychotherapy alone had a significant effect on reducing overall risk as measured by the Stable-2007, when taking testosterone-lowering medication (GnRH Agonists, CPA, or a combination) in addition to psychotherapy, the risk reduction was even greater. Moreover, the combination of medication and psychotherapy was shown to have a significant effect on improving sexual self-regulation when compared to psychotherapy alone.

Another study followed a sample of individuals convicted of a sexual offence for 20 years following treatment with a combination of a GnRH Agonist and CPA (Colstrup et al., Citation2020). The study indicated a sexual recidivism rate 7.7 times higher among those who stopped the medication in comparison to those who continued taking medication. Similar results have been found for the use of psychotherapy combined with Leuprolide Acetate (an anti-androgen), with sexual recidivism rates of 4.5% for a Cognitive Behavioral Therapy only group and 0% for a Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and medication group (Gallo et al., Citation2019).

In a double-blind RCT of the effects of GnRH Agonist medication (Degarelix) with a sample of Swedish men convicted of a child sex offence and diagnosed with paedophilia, medicated individuals exhibited a reduction in overall risk, paedophilic disorder and sexual preoccupation two- and ten-weeks post-medication (Landgren et al., Citation2020). This reduction was significantly larger than the reduction exhibited by the placebo group, while neither the Degarelix nor the placebo group exhibited any significant improvements in self-regulation, empathy, or self-reported risk. The short follow-up periods are, however, a limitation of this study.

Evidence to date (see Briken et al., Citation2003; Sauter et al., Citation2021; Turner & Briken, Citation2018) suggests that testosterone-lowering medication can be effective in reducing PSA as well as risk of and actual sexual reoffending, that medication is likely to be particularly helpful for individuals who exhibit deficits in sexual regulatory functions (i.e. PSA), and that a combination of psychotherapy and medication is most effective in reducing risk of sexual recidivism. However, Darjee and Quinn (Citation2020) called for caution when considering these findings due to significant methodological limitations. Two meta-analyses (Khan et al., Citation2015; Schmucker & Lösel, Citation2015) called into question the validity of these studies, noting differing samples (e.g. non-offending, adult offending, and child offending), lack of a matched control groups, the use of subjective outcome measures, short follow-up periods, studies not reporting recidivism rates and a lack of direct comparisons of different treatments. Ultimately, the considerable methodological issues of evaluation studies combined with the serious side effects of testosterone-lowering medication resulted in limited use of these medications in correctional settings (Landgren et al., Citation2020).

Meanwhile, more recent research has provided evidence for SSRIs as an alternative, albeit currently ‘off-label’ treatment to testosterone-lowering medications. Several research studies have been conducted into the use of various SSRIs (mainly Sertraline and Fluoxetine) for paraphilic behaviors and non-paraphilic PSA (Thibaut et al., Citation2020). These studies have reported promising results for the role of SSRIs in the treatment of PSA, including a less severe side effect profile and cost-effectiveness (Thibaut et al., Citation2020; see also Darjee & Quinn, Citation2020). Furthermore, as with testosterone-lowering medications, research has suggested that the use of SSRIs in combination with psychotherapy is most effective (Thibaut et al., Citation2020).

However, similar to the research into AAs and GnRH Agonists, three different meta-analyses conducted in the 2000s noted the lack of methodologically sound research, specifically referencing the small samples sizes, short follow-up periods, lack of control groups, lack of prospective studies, lack of reporting on recidivism, the use of self-report outcome measures, and the lack of RCTs (Thibaut et al., Citation2020; see also Darjee & Quinn, Citation2020). To date, the only RCT study conducted on SSRIs in treatment of PSA is a 12-week double-blind study on the use of Citalopram with a non-offending sample of homosexual and bisexual subjects with ‘sexual addiction’ (Wainberg et al., Citation2006). To the best of our knowledge, no RCTs have been conducted on SSRIs with a sample of individuals convicted of a sexual offence.

In 2018, an evaluation by Winder et al. (Citation2018) of the Medication to Manage Sexual Arousal pathway, assessed 127 patients and indicated that the SSRI medication Fluoxetine helped individuals serving a custodial sentence for a sexual offence control their extremely high levels of sexual arousal and/or preoccupation, which together fuel a drive for sexual outlets. However, this research did not include a comparison group. The current study addresses some of the limitations of previous research. It extends the findings by incorporating a non-matched comparison group of individuals serving a custodial sentence for a sexual offence who were not taking part in the medication programme, and by including an analysis of the clinical significance of pharmacological treatment on PSA in addition to statistical significance.

Research Aims and Hypotheses

This research aimed to examine the effects of medication (AAs and SSRIs) on reducing PSA in a sample of individuals serving a custodial sentence for a sexual offence, with inclusion of a non-medicated comparison group. We hypothesised that for individuals taking either AAs or SSRIs, there would be a significant reduction in PSA post-medication compared to baseline, with no significant reduction for the non-medicated comparison group. A further hypothesis postulated that there would be a clinically significant reduction in PSA, pre- and post-medication, for both types of medication but not for the comparison group.

Method

Participants

Participants were adult males living in a Category C UK therapeutic prison for people with sexual convictions, the majority of whom (79%) occupied single cells. Individuals are referred to this establishment for offending behaviour programmes, including programmes adapted for individuals with borderline IQ or low IQ. As such, there are a higher percentage of individuals at this establishment with borderline or low IQ (25%) compared to the general prison population. Of note, while no research has investigated rates of masturbation within this UK prison, research conducted in US prisons where masturbation is banned, would suggest that 90–100% of the current sample engage in masturbation (Hensley et al., Citation2001; Hughes, Citation2020; Wooden & Parker, Citation1982; Worley & Worley, Citation2021). However, this is likely to vary substantially between individuals, as this is the case for the general population (Gerressu et al., Citation2008).

The Medication to Manage Sexual Arousal (MMSA) service received 183 referrals for medication between 2010Footnote1 and March 2019. The HMPPS criteria for referral comprise evidence of one or more of the following:

Hyper-arousal (e.g. frequent sexual rumination, sexual preoccupation, difficulties in controlling sexual arousal, high levels of sexual behaviour),

intrusive sexual fantasies or urges,

subjective reports of experiencing urges that are difficult to control,

sexual sadism or other dangerous paraphilias such as necrophilia. Highly repetitive paraphilic offending such as voyeurism or exhibitionism’ (HMPPS, Citation2008, p. 3).

Of the 183 referrals 42 did not go on to receive medication (six because release was imminent, nine were clinically unsuitable, 16 refused, and 11 were under assessment at the time of analysis). Of the remaining 141 individuals, a further 56 were not included in this study (18 were already on the medication for other reasons preventing pre-medication measures, 31 did not consent to take part, two withdrew, two were released and three were on both AAs and SSRIs). Finally, eight participants were not included in the analysis because they did not complete the Sexual Compulsivity Scale three months post-baseline (two on AAs and six on SSRIs). The final experimental sample comprised 77 individuals, with eight receiving AAs (CPA) and 69 receiving SSRIs (66: Fluoxetine; 2: Paroxetine; 1: Sertraline).

The non-matched comparison group initially consisted of 94 participants who were approached to take part in the study at induction to the prison. Asking if people in prison are interested in contributing to voluntary research projects is standard procedure within this prison during their induction phase, and there is often a good uptake due to the supportive climate of the prison. There were no other criteria for participation, and the comparison group were not matched with the experimental group for age, IQ, ethnicity, or risk (comparisons for these variables can be seen in ). Thirty-six participants in the comparison group did not receive both a baseline and three-month post-baseline score for PSA, resulting in a final comparison sample of 58.

Table 1. Mean and median scores for age, IQ, RM2000 (sexual), RM2000 (violent) and SARN across experimental and comparison samples.

Medication

Two types of medication were used with the current sample: AAs (CPA) and SSRIs (Fluoxetine or, where there were contra-indications, Paroxetine or Sertraline). Decision about medication most suitable for each participant were made in line with the National Offender Management System (NOMS) guidelines (National Offender Management Service, Citation2015) and recommendations made by Grubin (Citation2018) Grubin et al. (Citation2021). SSRIs were prescribed to those with less severe problematic sexual arousal. In the most severe cases, or where the SSRIs did not appear to be working sufficiently in terms of reducing levels of PSA (either in the view of the psychiatrist or the view of the patient and psychiatrist), AAs were prescribed. Of note, no participants were prescribed the third possible medication that is offered on the prison services medical treatment pathway, GnRH Agonists.

Dosage

In the SSRI group, individuals typically commenced with oral 20 mg/day Fluoxetine, increasing to 40/60 mg/day as per the clinical judgement of the consulting psychiatrist. The typical starting dosage for AAs was oral 50 mg/day with dosage increased to 100 mg/day where the psychiatrist deemed this necessary and/or helpful. Dosages are in line with current guidelines for the treatment of paraphilic disorder (Thibaut et al., Citation2020) and the clinical judgment of the consulting psychiatrist.

Measures

As part of the wider evaluation of medication to manage PSA, data were collected on demographics, offence-related information, sentence, and type and dosage of medication. IQ was assessed by the prison as part of the standard assessment procedure for offending behaviour programmes utilising the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence-Second Edition [WAIS-II; Wechsler (Citation2011)] or, where available for the individual, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth Edition [WAIS-IV; Wechsler (Citation2008)]). Where both scores were available, the WAIS-IV score was used. Static and dynamic risk data were utilised from pre-existing assessments: static risk was recorded from Risk Matrix 2000 (RM2000; Thornton et al., Citation2003) and dynamic risk was reported from the Structured Assessment of Risk and Need (SARN; Thornton, Citation2002), and were carried out by trained psychologists as part of the standard assessment procedure within the prison. Data relating to clinical measures used by the psychiatrist to assess PSA were collated from health files, together with a psychometric measure of PSA, the Sexual Compulsivity Scale (Kalichman et al., Citation1994), administered by the research team.

Sexual compulsivity scale

The Sexual Compulsivity Scale was developed by Kalichman et al. (Citation1994) to assess insistent, intrusive, and uncontrolled sexual thoughts and behaviour. It is a 10-item scale with participants rating a series of statements using a four-point response scale ranging from one (not like me at all) to four (very much like me). Mean scores were calculated for each participant ranging between one and four. Indicative items include: ‘my sexual thoughts and behaviours are causing problems in my life’ and ‘my desires to have sex have disrupted my daily life’. In HMPPS, an individual is referred for medication to manage their problematic sexual arousal if their total score is 15 or higher, or if they score 3 or 4 on any one of the ten SCS items. A reduction in SCS indicates a reduction in problematic sexual behaviour.

A meta-analysis in 2010 reported that Cronbach’s alpha across 30 samples ranged from .59 to .92, and only one sample reported an alpha of less than .70 (Hook et al., Citation2010). Examples include, 0.83 among college students (Perry et al., Citation2007), 0.90 among a sample of homosexual men (Dodge et al., Citation2008), 0.79 for clients who were seeking treatment for hypersexuality (Reid et al., Citation2008), and 0.79 among a sample of young adults (McBride et al., Citation2008). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale with the current sample was 0.94; Cronbach’s alpha for the group with intellectual disability (IQ ≤ 70) was 0.94, 0.90 for the borderline intellectual disability group (IQ = 71–80) and 0.91 for those above borderline intellectual disability (IQ ≥ 81). The scale has also been reported as being valid and reliable for use with the current population (Winder, Lievesley, Kaul, et al., Citation2014) and is currently used as part of the MMSA pathway evaluation by both prescribing forensic psychiatrists.

Two clinical cut-off points were used: (i) the suggested problematic cut-off of >2.1 provided by previous research (Öberg et al., Citation2017) and (ii) the service cut-off of ≥1.5 when used with people who have a sexual conviction. The latter was established through the clinical judgment of the consulting psychiatrist, together with input from the research team with regards to scoring and descriptive statistics of the scale. This is interpreted within the context of findings from the on-going evaluation of individuals referred for medication to manage PSA in HMPPS (see Winder et al., Citation2018; Winder, Lievesley, Kaul, et al., Citation2014).

The Sexual Compulsivity Scale was administered by a member of the research team, ordinarily in a one-to-one meeting with participants. Thirty of the potential participants were deemed ‘high risk’ by the prison security department or key personnel, and thus the scale was administered with an additional researcher present. Due to the proportion of participants with an intellectual disability or a borderline intellectual disability, the researchers read questions aloud to all participants to standardise the procedure. Participants gave their answer verbally from a four-point, colour-coded response card.

Clinical measures of PSA

The measures reported below are routinely collected by the psychiatrist in the Medication to Manage Sexual Arousal programme being evaluated here and are the standard clinical measures used across UK prison estate and in previous research (e.g. Winder et al., Citation2018; Winder, Lievesley, Kaul, et al., Citation2014). These measures were developed based on Kafka’s (Kafka, Citation1994; Kafka & Hennen, Citation2000, Citation2003; M. P. Kafka & Prentky, Citation1992, Citation1992b) Sexual Outlet Inventory (Grubin, personal communication, March 2021).

• Hypersexual behaviour. Assessed by recording how many days in the past week participants self-reported as having masturbated to orgasm (0–7 days).

• Sexual preoccupation. Assessed by the item ‘how much time do you spend thinking about sex?’ Responses were collated on a 10-point scale (1: Low [Very little]; 10: High [All the time]). Additional items relating to this were ‘what is the strength of your sexual urges and fantasies?’ (1: Low; 10: High), ‘what is your ability to distract yourself from sexual thoughts?’ (1: Easy; 10: Difficult), the ‘maximum number of times engaged in sexual activity in any day’ (unlimited), and ‘feeling horny’ (1: Low; 10: High).

The data were collated on different occasions and within different contexts (with clinical data collated during doctor-patient consultations by the prison psychiatrist and PSA data collated by the research team). Moreover, participants were not reminded of their previous responses (collated 11–13 weeks previously), nor did the research team review data from previous instances before subsequent data collection.

Psychological interventions

Of the eight individuals in the AA group, 62.5% had previously completed Core Sex Offender Treatment Programme, 37.5% had completed cognitive programmes (e.g. Self Change Programme, Thinking Skills Programme, Enhanced Thinking Skills, Reasoning & Rehabilitation, Think First), and 25% had completed Healthy Sex Program. None had completed Extended Sex Offender Treatment Program or anger management programs (e.g. Controlling Anger and Learning to Manage it; Resolve).

Meanwhile, of the 69 individuals in the SSRI group, 59.4% had previously completed Core Sex Offender Treatment Programme, 43.5% had completed cognitive programmes, 30.4% had completed Healthy Sex Program and 10.1% had completed anger management programs, and 21.7% had completed Extended Sex Offender Treatment Program.

Finally, of the 58 individuals in the comparison group, 30.4% had previously completed Healthy Sex Programme, 20.7% had previously completed the Core Sex Offender Treatment Programme, 19.0% had completed cognitive programmes, 5.2% had completed Extended Sex Offender Treatment Programme, and 3.4% had completed anger management programmes.

It is difficult to know whether previous psychological treatment has a confounding effect. However, the participants have previously reported difficulties concentrating on psychological treatment programmes (see Lievesley et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, the evaluation by Mews et al. (Citation2017) highlighted challenges in understanding who the Core Sex Offender Treatment Programme might have worked for and could not report the mechanism by which it worked for some. For those individuals with PSA to the degree that they could not even follow the plot of a film (Winder et al., Citation2018), participating in a Core Sex Offender Treatment Programme session may not have been helpful.

Procedure

It is standard practice for people in prison to complete the Sexual Compulsivity Scale during their programmes induction at HMP Whatton. Individuals who present with scores above the service cut-off for PSA (≥1.5) are invited, with their consent, to be assessed for the MMSA treatment pathway. It is members of this programme who were then invited voluntarily to be part of the experimental group for this study, while those who had scores below the service cut-off were invited to take part in the comparison group. Additionally, individuals above the service cut off (≥1.5) but who were deemed unsuitable or refused medication were invited to take part in the comparison group.

In addition to the initial Sexual Compulsivity Scale screening at induction, individuals who perceived themselves to have problems managing sexual thoughts could self-refer to prison healthcare at any point. Individuals who were perceived by others (prison staff including wing staff and intervention facilitators) as having problems managing their sexual thoughts and behaviours were, with their consent, referred to prison healthcare. The psychiatrist met with each potential referral, and, where appropriate, pharmacological treatment was prescribed. Participants continued to meet with the psychiatrist on a regular basis, and, at each meeting, clinical measures of PSA (as listed above) were collated as part of the patient-psychiatrist consultation.

All participants completed the Sexual Compulsivity Scale pre-medication (baseline) and every three months post-medication, conducted by a member of the research team. The comparison group did not complete the clinical measures. Medical and offence-related data were collated for each participant from psychology, medical and programme files.

Ethical approval for the research was obtained from a UK University, the NHS, and the HMPPS national ethics committee. Ethical protocols (informed consent, debrief and support to participants, and withdrawal and confidentiality of data) were adhered to.

Statistical process and procedure

Data were analysed using SPSS v.25. First, differences in the demographic variables age and IQ were analysed using between-subjects 1 × 3ANOVA, with type of medication (AAs, SSRIs, or comparison group) as the between-subjects factor. Second, scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale were triangulated with the clinical measures of sexual preoccupation carried out by prescribing psychiatrist using Pearson’s correlation to bolster the use of a self-report measure as the primary outcome measure. Third, to compare the effects of medication on sexual compulsivity, a 2 × 3 mixed ANOVA was conducted, with treatment time point (pre- and post-medication) as the repeated measures factor, type of medication (AAs, SSRIs, or comparison group) as the between-subjects factors, and the mean score on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale as the dependent variable. Main effects and interactions were explored using paired t-tests. Fourth, clinical change was analysed using chi-square tests.

Results

Demographics

Demographics are reported in . Of note, demographic data were not available for all participants. One-way ANOVAs were used to compare each medication group and the comparison group for both age and IQ. There was no significant difference in age (p = .440), while differences in IQ were approaching significance IQ (p = .057). Post-hoc analysis revealed a significant difference in IQ between the AA and comparison groups (p = .021) with other comparison being non-significant (p min = .101 for SSRI compared to comparison group). The percentage of participants with an IQ ≤ 80 was 42.90% (n = 3) of the AA group, 26.00% (n = 13) of the SSRI group, and 12.50% (n = 2) of comparison group.

All the participants in the AA and SSRI groups for whom nationality and ethnicity data were available were White (n = 70) and British (n = 73). Meanwhile, of the 52 participants in the comparison group for whom nationality and ethnicity data were available, 86.20% (n = 50) were British, 1.70% (n = 1) were Afghan, 1.70% (n = 1) were Bangladeshi; 84.50% (n = 49) were White, 3.40% (n = 2) were Asian, and 1.70% (n = 1) were Black Caribbean. Furthermore, 62.5% (n = 5) of the AA group, 56.52% (n = 39) of the SSRI group, 48.28% (n = 28) of the comparison group − 59.35% of the total sample (n = 73) – did not identify as having a religion.

Risk was assessed using the Risk Matrix 2000 (RM2000; Thornton et al., Citation2003) and Structured Assessment of Risk and Needs (SARN; Thornton, Citation2002). Risk data for the full sample (n = 100) demonstrate that the mean rating on the RM2000 was 2.53 and 1.84 for sexual and violent risk respectively. This equates to a mean rating of moderate-high risk of sexual recidivism and a low-moderate risk of violent recidivism. A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of group on the Risk Matrix 2000 sexual risk (p = .001) and a non-significant effect on violent risk (p = .203). Post-hoc analysis revealed that for Risk Matrix 2000 sexual risk, the AA and SSRI group both scored significantly higher than the comparison group (p = .015 and p = .001), while the AA and SSRI group did not differ significantly (p = .714).

Risk of further harm data available via the SARN for n = 50 of the sample demonstrated that the highest scoring dynamic risk factor domain was ‘self-management general’ (Mean = 1.31, SD = 0.44) (whereby ‘general’ refers to the individual’s life generally) followed by, ‘socio-emotive functioning general’ (Mean = 1.24, SD = 0.40), ‘sexual interest offence chain’ (Mean = 1.19, SD = 0.33) (where ‘offence chain’ refers to the lead-up to the offence for which they were convicted), ‘sexual interest general’ (Mean = 1.17, SD = 0.37) and ‘socio-emotion functioning offence chain’ (Mean = 1.00, SD = 0.41). With a Mean ≥1, these domains were ‘present’ but not ‘strongly present’ within the sample. Meanwhile the lowest scores were for ‘self-management offence chain’ (Mean = 0.79, SD = 0.44), ‘distorted attitudes general’ (Mean = 0.79, SD = 0.47) and ‘distorted attitudes offence chain’ (Mean = 0.66, SD = 0.36). With a mean <1, these domains were ‘not present’ within the sample. A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of group on ‘sexual interest general’ (p = .039) only, and post-hoc analysis revealed a significant difference between the SSRI and comparison groups (p = .016) and the AA and comparison groups (p = .048) but not the SSRI and AA group (p = .608).

Of the individuals that received AAs, two reported side effects, with one individual reported feeling more tired, and one individual reported weight gain. Of the individuals that received SSRIs, 22 reported side effects, with 10 individuals reported feeling more tired, three reported headaches, two reported feeling nauseous, two experienced constipation, and two reported heartburn. The following side effects were reported by n = 1: waking up early, feeling more alert, agitation/restlessness, muscle ache, pins and needles in arm, dizziness, sweating, dry mouth, jaw clenching, acid reflux, dizziness, itchiness, and diarrhoea.

Triangulation of measures of sexual compulsivity

To bolster the use of a self-report measure as the main clinical measure of sexual compulsivity, the Sexual Compulsivity Scale was triangulated with the six clinical measures described above, by correlating scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale with scores on the six clinical measures. As can be seen in , scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale were significantly, positively correlated with: ‘number of days masturbated to orgasm’ pre-medication but not post-medication; ‘strength of sexual urges’ pre- and post-medication; ‘ability to distract from sexual thoughts’ pre- and post-medication; ‘time spent thinking about sex’ pre- and post-medication; and ‘feeling horny’ pre- and post-medication. However, scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale were not significantly correlated with ‘max times engaged in sexual activity in a day’ pre- or post-medication. As such, the clinical data and psychometric data demonstrated good triangulation.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for clinical measures and correlation with Sexual Compulsivity.

Statistical change in mean sexual compulsivity scores

Pre-medication

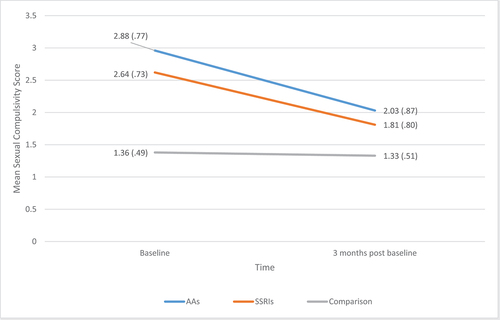

As can be seen in , pre-medication sexual compulsivity scores were not equal between groups, confirmed by one-way ANOVA showing a significant effect of treatment group F(2,134) = 69.48, p = .001. Post-hoc tests demonstrated that sexual compulsivity scores were significantly lower for the comparison group compared to either SSRI or AA group (p < .001 for both). Sexual compulsivity scores for AAs were higher than for SSRIs (as might be expected due to treatment guidelines) but did not differ significantly (p = .328).

Treatment effect

As can be seen in , mean sexual compulsivity scores reduced in both medication groups (but not the comparison group), following treatment. Median scores revealed the same pattern of effect with median sexual compulsivity score for SSRI = 2.70 & 1.50, for AA = 3.05 & 2.05 and for comparison group = 1.10 & 1.10 for pre and post measures respectively. To compare the effects of medication on sexual compulsivity, a 2 × 3 mixed ANOVA was conducted with mean scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale as the within-subjects factor (pre- and post-medication) and treatment group (AA, SSRI or comparison) as the between subjects factor. There was a significant reduction in scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale between pre- and three months post-medication F(1,132) = 48.86, p =.001, ηp2 =.270; a significant effect of type of medication F(2,132) = 39.42, p = .001, ηp2 =.374, and a significant interaction between type of medication and time point F(2,132) = 27.36, p = .000, ηp2=.293, demonstrating that the reduction in sexual compulsivity over time varied by treatment group. Three paired sample t-tests revealed a significant decrease in mean sexual compulsivity scores for the AA group, t(7) = 2.61, p = .035 and SSRI group, t(68) = 8.95, p < .001, but not the comparison group, t(57) = 0.94, p = .352 (see ).

Clinical change in mean sexual compulsivity scores

Pre-medication

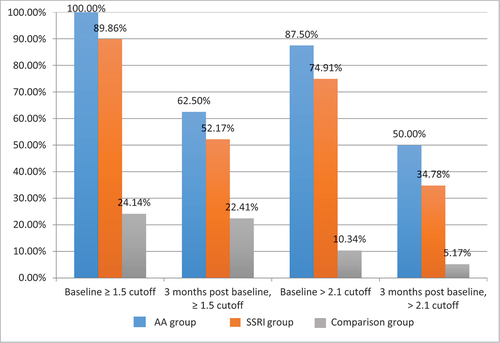

As can be seen from , pre-medication there were significantly more participants ≥ 1.5 than would be expected by chance in both the AA group (100.00%) and SSRI group (89.86%), while the opposite was true for the comparison group (24.14%), χ2 (2) = 63.06, p < .001. Likewise, there were significantly more participants above the cut off of >2.1 than would be expected by chance in both the AA group (87.50%) and SSRI group (73.91%), while the opposite was true for the comparison group (10.34%), χ2 (2) = 56.55, p < .001.

Figure 2. Frequencies of participants below and above cut offs (≥1.5 and >2.1) for sexual compulsivity pre-medication and (three months) post-medication for (i) Anti-Androgens (n = 8), (ii) Selective-Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (n = 72) and (iii) no medication (n = 58) pre-medication and three months post-medication.

Treatment effect

illustrates that following 3 months of treatment, there were still more participants ≥1.5 than would be expected by chance in the AA group (62.50%) and the SSRI group (52.17%), but not in the comparison group (22.41%), χ2 (2) = 13.42, p = .001. Meanwhile, there were significantly fewer participants >2.1 than would be expected by chance in the AA group (50%) and SSRI group (34.78%), but not the comparison group where the opposite is true (5.17%), χ2 (2) = 19.13, p < .000.

For the AA group, 37.5% of participant’s scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale fell from above to below ≥1.5 and 37.5% fell from above to below >2.1. For the SSRI group, 37.68% of participant’s scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale fell from above to below ≥1.5 and 39.13% feel from above to below >2.1. Finally, for the comparison group 1.72% of participant’s scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale fell from above to below ≥1.5 and 5.17% fell from above to below >2.1. As such, AAs were clinically effective for 37.50% of participants, while SSRIs were clinically effective for around 38.41% of participants (mean of 37.68% and 39.13%).

Discussion

The current study hypothesised that both types of pharmacological treatment (AAs and SSRIs) would significantly reduce PSA in adult males serving custodial sentences for a sexual offence, and that an unmatched, non-medicated comparison group would not show a significant reduction in PSA. Further, the authors hypothesised that both types of medication would demonstrate higher numbers of patients moving from clinically problematic to non-problematic PSA scores compared to the non-medicated group. Change was examined between pre-medication (baseline) and (3 months) post-medication, which is an appropriate time interval to allow for AAs and SSRIs to take effect (Brotherton, Citation1974; Gelenberg & Chesen, Citation2000; Parker et al., Citation2000).

The study’s findings indicated that, as hypothesised, sexual compulsivity reduced between pre-medication (baseline) and (3 months) post-medication for both medication groups but not for the non-medicated comparison group. The percentage reduction in scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale was 29.50% for AAs, 31.44% for SSRIs and 2.20% for the comparison group. Furthermore, in terms of clinical change, AAs and SSRIs were both clinically effective for around 38% of participants. This was true for both the suggested problematic cut-off of > 2.1 provided by previous research (Öberg et al., Citation2017) and the service cut-off of ≥1.5. While the AA group demonstrated a reduction in sexual compulsivity pre- and post-medication, the smaller sample size for the AA group should be recognised as a limitation of the study. However, previous literature, albeit not without methodological limitations, supports the effectiveness of AAs in reducing sexual compulsivity (Gallo et al., Citation2019; Landgren et al., Citation2020; Sauter et al., Citation2020).

Importantly, our results suggest that SSRIs may be a viable tool in reducing sexual compulsivity for individuals serving a custodial sentence for a sexual conviction. This is an important finding considering that SSRIs are currently used for this purpose ‘off label’. Despite support from expert groups, the licence has not been expanded (Burns & Hull, Citation2014), and thus, SSRIs are not part of the current UK NICE guidelines for the treatment of PSA. The current findings strengthen the case for SSRIs use being expanded for this purpose and incorporated into NICE guidelines. Previous papers reporting on the evaluation of medication to reduce sexual compulsivity aggregated data from both AAs and SSRIs. It was therefore important to consider the SSRI group as a standalone experimental group and to ascertain how they performed compared to individuals taking AAs, given that AAs have already been tested as per NICE (Citation2015) guidelines and their anti-libidinal effect demonstrated (e.g. Khan et al., Citation2015).

The current research is important, as the need for effective pharmacological treatment to reduce sexual compulsivity in people who have committed a sexual offence is critical. An impact evaluation in 2017 of the former core cognitive-behavioural psychological treatment programme for people convicted of sexual offences highlighted that the programme was not associated with changes in sexual reoffending (Mews et al., Citation2017), with the lack of effect potentially related to sexual preoccupation for some individuals. Struggling with sexual thinking is the most strongly present risk factor for sexual reoffending, with as many as 73% of (1,426) men who have been convicted of a sexual offence reported as having an obsession with sex (Hocken et al., Citation2015). Further, previous research highlighted the difficulties in focusing on psychological treatment for individuals who were struggling with sexual thoughts, behaviour and urges (e.g. Akerman, Citation2008; W. L. Marshall, Citation2006). Such individuals report a sense of inadequacy, feeling that they were ‘untreatable’ (Winder et al, in prep.). The latter notion is backed up from the consulting psychiatrist’s experience with managing referrals to this study. Dr Kaul (personal communication, 12 December 2019) asserts that, whilst he receives referrals based on certain criteria, the referrals from staff are typically for those individuals who have not responded to other treatments – the so-called ‘treatment-resistant’ group. This suggests that pharmacological treatment is predominantly sought and utilised by individuals who have struggled to complete psychological treatment, although this issue needs further consideration.

We are not arguing that SSRIs replace AAs given that the decision as to which type of medication that is offered to individuals with sexual compulsivity rests on the current guidelines (recently updated by Grubin and colleagues, see Winder et al., Citation2019 and clinical judgement). Rather, our findings provide further evidence for SSRIs as an additional treatment option. SSRIs could perhaps be prescribed as a starting point, but if these are not deemed to be reducing PSA (as assessed by the psychiatrist and considering reports from the patient in addition to any other input from, for example, psychologists), the patient may then be moved on to AAs. SSRIs have been previously suggested to be helpful in giving an individual some ‘headspace’ (Lievesley et al., Citation2014), which may be beneficial in that it can facilitate recognition and reflection on previous, harmful, behaviour to self and others. However, this may also cause greater distress (Winder, Lievesley, Elliott, et al., Citation2014). Healthcare professionals prescribing any medication to reduce PSA, in the prison or especially in the more uncontrolled environment of the community, should be mindful of this and the trauma that may ensue from this increased time and capabilities for reflection on prior actions.

In the present study, the reduction in participants’ scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale was similar for those taking SSRIs compared (29.50%) to AAs (31.44%). Furthermore, clinically significant changes were observed for a similar number of participants in each treatment group (around 38%). As such, the use of SSRIs might be preferable in terms of side effects, profile, and the cost to NHS. Also, for those prescribers who use GnRH Agonists (in preference to the AA predominantly used here), there can be an issue with testosterone flare in the initial few weeks of taking the medication, with a rebound on the cessation of medication (Huygh et al., Citation2015; Lewis et al., Citation2017; Turner & Briken, Citation2018). Use of SSRIs or AAs could prevent this issue and remove the need for additional medication to counter the testosterone flare. However, it should also be noted that SSRIs and AAs may be prescribed for differing treatment needs, with SSRIs thought by some to be best for compulsive thinking (Guay, Citation2009) and AAs more appropriate if there is a need to directly reduce testosterone (Thibaut et al., Citation2010).

Overall, due to increasing severity of side effects, we support previous suggestions that SSRIs should be used initially for individuals, while AA (and GnRH Agonists) should be considered for people presenting with more severe PSA, and in cases where SSRIs have been proven ineffective (J. M. W. Bradford, Citation2000; Briken, Citation2020; Turner & Briken, Citation2021). The prevailing consensus endorses the integration of pharmacological treatments with psychological interventions for managing problematic sexual arousal (Turner & Briken, Citation2021). This approach is intuitively appealing, yet it necessitates a deeper exploration to understand which psychological interventions are effective, why, and if the timing of the intervention is important. This inquiry could encompass considerations such as whether individuals should receive personalised therapy to address potential trauma that may emerge as PSA diminishes or if the effectiveness of standard psychological interventions is enhanced when PSA is medically controlled. Additionally, there is concern that the full benefits of medication may not be realised without concurrent psychological support (although this needs to be examined and tested). In our study, the majority of participants had engaged in one or more forms of psychological intervention prior to their involvement. Nevertheless, future studies should investigate the optimal timing of psychological therapy relative to medication administration to determine if the effectiveness of psychological interventions is heightened when medication is received beforehand, and whether or not psychological input is a necessary or useful adjunct to medical treatment.

Strengths and limitations

It is a strength of this study that there is a non-medicated comparison group from the same prison, which has not been present in previous research (see Winder et al., Citation2018; Winder, Lievesley, Kaul, et al., Citation2014). This is important because of the possibility that scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale might change simply owing to the prison environment. There is limited direct research on effects of prison on testosterone levels, for example, W. M. Thompson et al. (Citation1990) evidenced that levels of testosterone were reduced within 4 weeks of being sentenced to custody and then rose again thereafter. It is likely that for some individuals, incarceration may lead to reductions, given the known relationship between androgens and defeat or stress (Björkqvist, Citation2001; Maner et al., Citation2008). This would, however, vary depending on the individual’s experience of the prison environment. In fact, a service user research panel of people serving custodial sentences for sexual offences reported that levels of sexual arousal may be higher in prison due to lack of available outlets (WASREP, personal communication, January 2019). In any case, the relationship between testosterone level and sexual compulsivity is not at all straightforward (J. M. Bradford, Citation2001).

A primary limitation of this evaluation was the lack of matched controls especially in terms of matching for pre-medication (baseline) levels of sexual compulsivity. As such, results should be interpreted with some caution. It is possible that the low levels of PSA seen in the comparison group produced a floor effect preventing a significant reduction in PSA levels from being seen. We attempted to address this by analysing the change in scores in those participants in the comparison group who had scores above the clinical cut-off.

In terms of the matching of other variables, there was no significant difference in age or IQ between the experimental and comparison groups. The mean IQ score was lower in the experimental group, and the percentage of people with borderline intellectual disability (BID) was higher in the experimental than the comparison group. However, levels of IQ are not related to levels of PSA (Engel et al., Citation2019). There are several presumed reasons why the proportion of people with borderline or intellectual disability seek medication to manage PSA, such as that they are more honest about their inability to hide or manage their PSA, more comfortable with medication, or that it is due to the typical characteristics associated with intellectual disability such as a tendency to acquiesce (Finlay & Lyons, Citation2002; Heal & Sigelman, Citation1995; Holden & Gitlesen, Citation2004; D. Thompson & Brown, Citation1997). In the current study, there was however some inequity in terms of availability of IQ data for the groups. IQ data were not available for all participants because people serving custodial sentences only complete IQ tests if a decision about appropriate treatment programme is required (borderline and intellectually disabled individuals access-specific programmes for those with learning disabilities and challenges). As such, for those patients who did not have a WAIS-IV score, their IQ was tested using the WAIS-II. It was not possible to administer the WAIS-IV due to time constraints.

Comparison group participants had typically arrived at the prison more recently than those in medicated groups and thus were less likely to have had pre-treatment assessments completed. It is possible that at baseline, levels of masturbation were lower for the comparison group compared to the experimental group, as they were new to the prison and may have been reluctant to masturbate until they felt more comfortable in their new surroundings. This may have affected the comparison group’s scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale, which includes items about the degree to which ones’ sexual behaviours are problematic.

Furthermore, the use of self-report measures to assess PSA is a valid critique of this study. However, the Sexual Compulsivity Scale (Kalichman et al., Citation1994) used here was demonstrated to be both reliable with this sample (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94) and valid. Validity of the Sexual Compulsivity Scale is further demonstrated through convergent correlations with five of the six clinical measures of PSA, first developed by Grubin and subsequently used as markers of PSA in this and other studies (e.g. Winder et al., Citation2018; Winder, Lievesley, Kaul, et al., Citation2014). In the current study, scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale were highly correlated with: ‘number of days masturbated to orgasm’ pre-medication but not post-medication; ‘strength of sexual urges’ pre- and post-medication; ‘ability to distract from sexual thoughts’ pre- and post-medication; ‘time spent thinking about sex’ pre- and post-medication; and ‘feeling horny’ pre- and post-medication.

Other limitations are the absence of information around psychiatric illnesses, the lack of information about other medications that participants may have been prescribed, and absence of clinical measures for the comparison group. Unfortunately, the resources were not available to conduct these assessments.

We also acknowledge that this study, alike previous studies in the area, utilised a modest sample size, particularly with regard to the AA group. The majority of individuals who chose to embark upon the medical treatment pathway for PSA were prescribed SSRIs, which highlights the importance of evaluating the impact of SSRIs. However, the modest sample sizes likely increased the probability that there was insufficient power to find some significant differences between the two medicated groups. As this was an observational, non-randomised evaluation study open to interested participants with high scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale rather than a controlled trial, we recognise the need for further work in this area. Future research should include an RCT with a larger sample size to further verify and strengthen our findings. At the same time, we acknowledge that the practicalities of this are difficult given the population. In 2006, an attempt at an RCT was made by Grubin but had to be abandoned due to an inadequate sample. Nonetheless, there are currently plans to conduct such an RCT study in the future.

Likewise, we recognise that it would be useful to be able to generalise the current findings to other sites. This may be possible in the future as the medication and accompanying evaluation and research has now been extended to seven other prison sites within the UK. However, uptake is slow and so research incorporating these other sites is not yet feasible.

Conclusions

The current study provided new evidence that both SSRIs and AAs significantly reduce PSA in a sample of those who have been incarcerated for sexual offences and were experiencing high levels of PSA at baseline. Given the less severe side effects and greater patient tolerance SSRIs when compared to AAs, this could be a vital consideration for treatment. This may be particularly important in the community, where individuals may be more likely to wish for some level of healthy sexual activity that is more achievable with SSRIs than AAs. Also, it may be that community general practitioners would feel more comfortable prescribing SSRIs than AAs due to the less severe side effect profile. Many of the men on this treatment will be released into the community in the future, meaning that such considerations around compliance are important. However, the different treatment needs and starting points of individuals still need to be considered. Given the constraints of researching an evaluation and the limitations of a comparison group, the next step is to conduct a randomised controlled trial of SSRIs versus placebo. This would further evidence a role for SSRIs in treatment of PSA and inform NICE guidelines.

W. L. Marshall (Citation2006). Appraising treatment outcome with sexual offenders. Sexual offender treatment: Controversial issues, 255–273.

Author Contributions

Belinda Winder: Principal Investigator at all stages of the research, data analysis, writing introduction and original draft, collating and addressing amendments. Christine Norman: data analysis, co-writing the original draft and critically reviewing the paper. Jackie Hamilton: data collection, data analysis and co-writing the original full draft. Steven Cass: data analysis, critically reviewing the paper, editing the paper. Alex Lambert: reviewing original draft, redoing some analysis and attending to revisions. Laura Tovey: data collection and co-writing the original draft. Kerensa Hocken: clinical input and critically reviewing the paper. Emma Marshall: data collection, writing and editing the paper. Rebecca Lievesley: data collection, contributing to research design and writing of the paper. Zoe Antoniadis: reviewing the paper, editing, revising and contributing to policy information. Adarsh Kaul: clinical input, contributing to research design, data collection and critically reviewing the paper.

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to all participants who contributed their data, and to prison and healthcare staff for facilitating this research. Thanks to our colleagues Helen Swaby and Michael Underwood who contributed to this research and paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Three individuals had been referred in 2009, but this was prior to the evaluation research; the majority of referrals were between 2010 and 2018.

References

- Akerman, G. (2008). The development of a fantasy modification programme for a prison-based therapeutic community. International Journal of Therapeutic Communities, 29(2), 180–188.

- Balon, R., & Briken, P. (2021). Compulsive sexual behavior disorder: Understanding, assessment, and treatment. American Psychiatric Pub.

- Bancroft, J. (2008). Sexual behavior that is “out of control”: A theoretical conceptual approach. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 31(4), 593–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2008.06.009

- Barros, S., Oliveira, C., Araújo, E., Moreira, D., Almeida, F., & Santos, A. (2022). Community intervention programs for sex offenders: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 949899. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.949899

- Beech, A. R., & Mitchell, I. J. (2005). A neurobiological perspective on attachment problems in sexual offenders and the role of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in the treatment of such problems. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(2), 153–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.10.002

- Björkqvist, K. (2001). Social defeat as a stressor in humans. Physiology & Behavior, 73(3), 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9384(01)00490-5

- Blanchard, G. (1990). Differential diagnosis of sex offenders: Distinguishing characteristics of the sex addict. American Journal of Preventive Psychiatry and Neurology, 2(3), 45–47.

- Bonta, J., & Andrews, D. A. (2007). Risk-need-responsivity model for offender assessment and rehabilitation. Rehabilitation, 6(1), 1–22.

- Bradford, J. M. (2001). The neurobiology, neuropharmacology, and pharmacological treatment of the paraphilias and compulsive sexual behaviour. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 46(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370104600104

- Bradford, J. M. W. (2000). The treatment of sexual deviation using a pharmacological approach. Journal of Sex Research, 37(3), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490009552045

- Bradford, J. M., & Pawlak, A. (1993). Double-blind placebo crossover study of cyproterone acetate in the treatment of the paraphilias. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 22(5), 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01542555

- Briken, P. (2020). An integrated model to assess and treat compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. Nature Reviews Urology, 17(7), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-020-0343-7

- Briken, P., Hill, A., & Berner, W. (2003). Pharmacotherapy of paraphilias with long-acting agonists of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone: A systematic review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64(8), 890–897. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v64n0806

- Brody, S., & Costa, R. M. (2009). Satisfaction (sexual, life, relationship, and mental health) is associated directly with penile–vaginal intercourse, but inversely with other sexual behavior frequencies. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(7), 1947–1954. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01303.x

- Brotherton, J. (1974). Effect of oral cyproterone acetate on urinary and serum FSH and LH levels in adult males being treated for hypersexuality. Reproduction, 36(1), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1530/jrf.0.0360177

- Burns, L., & Hull, J. (2014). Unlicensed and Off-Label Medication. Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. https://www.ouh.nhs.uk/patient-guide/leaflets/files/12048Punlicensed.pdf

- Carnes, P. (1991). Don’t call it love: Recovering from sexual addiction. Bantam.

- Carnes, P. (1994). Contrary to love: Helping the sexual addict. Hazelden Publishing.

- Carnes, P. (2001). Out of the shadows: Understanding sexual addiction. Hazelden Publishing.

- Carvalho, A. F., Sharma, M. S., Brunoni, A. R., Vieta, E., & Fava, G. A. (2016). The safety, tolerability and risks associated with the use of newer generation antidepressant drugs: A critical review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 85(5), 270–288. https://doi.org/10.1159/000447034

- Cascade, E., Kalali, A. H., & Kennedy, S. H. (2009). Real-world data on SSRI antidepressant side effects. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 6(2), 16.

- Colstrup, H., Larsen, E. D., Mollerup, S., Tarp, H., Soelberg, J., & Rosthøj, S. (2020). Long-term follow-up of 60 incarcerated male sexual offenders pharmacologically castrated with a combination of GnRH agonist and cyproterone acetate. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 31(2), 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2020.1711957

- Darjee, R., & Quinn, A. (2020). Pharmacological treatment of sexual offenders. In J. Proulx, F. Cortoni, L. A. Craig, & E. J. Letourneau (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of what works with sexual offenders: Contemporary perspectives in theory, assessment, treatment, and prevention (pp. 217–245). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119439325.ch13.

- Dodge, B., Reece, M., Herbenick, D., Fisher, C., Satinsky, S., & Stupiansky, N. (2008). Relations between sexually transmitted infection diagnosis and sexual compulsivity in a community-based sample of men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 84(4), 324–327. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2007.028696

- Engel, J., Veit, M., Sinke, C., Heitland, I., Kneer, J., Hillemacher, T., Hartmann, U., & Kruger, T. H. (2019). Same same but different: A clinical characterization of men with hypersexual disorder in the sex@ brain study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(2), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8020157

- English, K. (1998). The containment approach: An aggressive strategy for the community management of adult sex offenders. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 4(1–2), 218. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8971.4.1-2.218

- Eriksson, T., & Eriksson, M. (1998). Irradiation therapy prevents gynecomastia in sex offenders treated with antiandrogens. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(8), 432–432. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v59n0806e

- Finkelhor, D. (1984). Child sexual abuse: New theory and research. The Free Press.

- Finlay, W. M., & Lyons, E. (2002). Acquiescence in interviews with people who have mental retardation. Mental Retardation, 40(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(2002)040<0014:AIIWPW>2.0.CO;2

- Freel, A., & Wakeling, H. (2023). The healthy sex programme an exploration of pre-to-post psychological test change. Ministry of Justice Analytical. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/63f4d6f28fa8f56131d0ee8e/healthy-sex-programme.pdf

- Gallo, A., Abracen, J., Looman, J., Jeglic, E., & Dickey, R. (2019). The use of leuprolide acetate in the management of high-risk sex offenders. Sexual Abuse, 31(8), 930–951. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063218791176

- Garcia, F. D., & Thibaut, F. (2010). Sexual addictions. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(5), 254–260. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2010.503823

- Gelenberg, A. J., & Chesen, C. L. (2000). How fast are antidepressants? The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(10), 712–721. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v61n1002

- Gerressu, M., Mercer, C. H., Graham, C. A., Wellings, K., & Johnson, A. M. (2008). Prevalence of masturbation and associated factors in a British national probability survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 266–278.

- Gil, M., Oliva, B., Timoner, J., Maciá, M. A., Bryant, V., & de Abajo, F. J. (2011). Risk of meningioma among users of high doses of cyproterone acetate as compared with the general population: Evidence from a population‐based cohort study. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 72(6), 965–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04031.x

- Gregório Hertz, P., Rettenberger, M., Turner, D., Briken, P., & Eher, R. (2022). Hypersexual disorder and recidivism risk in individuals convicted of sexual offenses. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 33(4), 572–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2022.2053183

- Groneman, C. (1994). Nymphomania: The historical construction of female sexuality. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 19(2), 337–367. https://doi.org/10.1086/494887

- Grov, C., Parsons, J. T., & Bimbi, D. S. (2010). Sexual compulsivity and sexual risk in gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(4), 940–949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9483-9

- Grubin, D. (2008). Medical models and interventions in sexual deviance. In D. R. Laws & W. T. O’Donohue (Eds.), Sexual Deviance (pp. 594–610). The Guildford Press.

- Grubin, D. (2018). The pharmacological treatment of sex offenders. In A. R. Beech, A. J. Carter, R. E. Mann, & P. Rotshtein (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell handbook of forensic neuroscience (pp. 703–723). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118650868.ch27.

- Grubin, D., Winder, B. & Cass, S.(2021). The use of medication in the treatment of people with sexual convictions. Nota Briefing. https://www.nota.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/NOTA-medication-paper-ready-for-publication.pdf

- Guay, D. R. (2009). Drug treatment of paraphilic and nonparaphilic sexual disorders. Clinical Therapeutics, 31(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.01.009

- Hall, G. C. N. (1995). Sexual offender recidivism revisited: A meta-analysis of recent treatment studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63(5), 802. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.63.5.802

- Hallikeri, V. R., Gouda, H. S., Aramani, S. C., Vijaykumar, A. G., & Ajaykumar, T. S. (2010). Masturbation—An overview. Journal of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, 27(2), 44–47.

- Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., Hanson, E., Whittle, H., & Beech, A. (2017). “Everyone deserves to feel happy and safe”: A mixed methods study exploring how online and offline child sexual abuse impact young people and how professionals respond to it. NSPCC Publications. https://www.nspcc.org.uk/globalassets/documents/research-reports/impact-online-offline-child-sexual-abuse.pdf.

- Hanson, R. K., Gordon, A., Harris, A. J., Marques, J. K., Murphy, W., Quinsey, V. L., & Seto, M. C. (2002). First report of the collaborative outcome data project on the effectiveness of psychological treatment for sex offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 14(2), 169–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906320201400207

- Hanson, R. K., & Morton-Bourgon, K. E. (2004). Predictors of sexual recidivism: An updated meta-analysis. (Corrections Research User Report No. 2004–02). Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada.

- Hanson, R. K., & Morton-Bourgon, K. E. (2005). The characteristics of persistent sexual offenders: A meta-analysis of recidivism studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(6), 1154–1163. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1154

- Heal, L. W., & Sigelman, C. K. (1995). Response biases in interviews of individuals with limited mental ability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 39(4), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.1995.tb00525.x

- Heinemann, L. A., Will‐Shahab, L., Van Kesteren, P., & Gooren, L. J. (1997). Safety of cyproterone acetate: Report of active surveillance. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 6(3), 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1557(199705)6:3<169:AID-PDS263>3.0.CO;2-3

- Hensley, C., Tewksbury, R., & Wright, J. (2001). Exploring the dynamics of masturbation and consensual same-sex activity within a male maximum security prison. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 10(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.3149/jms.1001.59

- Hill, A., Briken, P., Kraus, C., Strohm, K., & Berner, W. (2003). Differential pharmacological treatment of paraphilias and sex offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 47(4), 407–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X03253847

- HMPPS. (2008). Psychiatric assessment for sexual offenders: Interventions group.

- Hocken, K., Winder, B., & Lievesley, R. (2015). The use of anti-androgen and SSRI medication to treat sexual preoccupation in intellectually disabled sexual offenders: Client characteristics and response to treatment. Presentation to ATSA conference, Montreal, Canada. Association for the Treatment and Prevention of Sexual Abuse.

- Holden, B., & Gitlesen, J. P. (2004). Psychotropic medication in adults with mental retardation: Prevalence, and prescription practices. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 25(6), 509–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2004.03.004

- Hook, J. N., Hook, J. P., Davis, D. E., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Penberthy, J. K. (2010). Measuring sexual addiction and compulsivity: A critical review of instruments. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 36(3), 227–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926231003719673

- Hu, X. H., Bull, S. A., Hunkeler, E. M., Ming, E., Lee, J. Y., Fireman, B., & Markson, L. E. (2004). Incidence and duration of side effects and those rated as bothersome with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment for depression: Patient report versus physician estimate. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(7), 959–965. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v65n0712

- Hughes, S. D. (2020). Release within confinement: An alternative proposal for managing the masturbation of incarcerated men in US Prisons. Journal of Positive Sexuality, 6(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.51681/1.611

- Huygh, J., Verhaegen, A., Goethals, K., Cosyns, P., De Block, C., & Van Gaal, L. (2015). Prolonged flare-up of testosterone after administration of a gonadotrophin agonist to a sex offender: An under-recognized risk. Criminal Behaviour & Mental Health, 25(3), 226. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.1945

- Jannini, T. B., Lorenzo, G. D., Bianciardi, E., Niolu, C., Toscano, M., Ciocca, G., Jannini, E.A., & and Siracusano, A. (2022). Off-label uses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Current Neuropharmacology, 20(4), 693–712. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X19666210517150418

- Jordan, K., Fromberger, P., Stolpmann, G., & Müller, J. L. (2011). The role of testosterone in sexuality and paraphilia—A neurobiological approach. Part I: Testosterone and sexuality. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(11), 2993–3007. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02394.x

- Kafka, M. P. (1994). Sertraline pharmacotherapy for paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders; an open trial. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 6(3), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.3109/10401239409149003

- Kafka, M. P. (2010). Hypersexual disorder: A proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(2), 377–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9574-7