ABSTRACT

The study presented here, theoretically framed at the crossroads of sociocultural and decolonial perspectives, draws attention to the sudden proliferation of two specific neologisms in the area of language, education and identity across time and space. It particularly highlights concerns regarding the ways in which these are deployed within scholarship and in schools and teacher education currently in the nation-state of Sweden. The analysis presented in this paper throws critical light on the ways in which the emergence and proliferation of neologisms like translanguaging and nyanlända (newly-arrived) contribute towards (or confounds) issues related to communication and diversity in the educational sector. This is done by juxtaposing the trajectory and deployment of neologisms in relation to social practices across institutional spaces. Such an enterprise is important, given recent calls for flexibility against the backdrop of concerns regarding heterogeneous populations in schools in geopolitical spaces like Sweden. Here expectations regarding both inclusion and learning goals for all students are prioritised agendas. We draw upon data from ethnographical projects at the CCD research group (www.ju.se/ccd) to make our case. This includes naturally occurring interactional data and textual data, for instance, current scholarship, directives from the national bodies in charge of schools and teacher education in Sweden.

1. Introduction and aims

A decolonial, speculative project seeks to put modern, western thought to the test of non-modern, non-western realities, and to experience the transformation of our western imagination by the radical, decolonizing differences other realities, other concepts, and other truths, make (Savransky, Citation2017, p. 19).

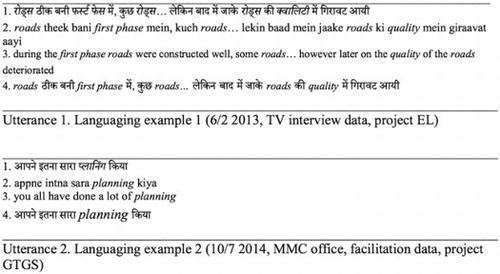

The two examples presented in Utterances 1–2 illustrate and introduce central issues focused upon in this study. First, the examples centre-stage routine deployment of more than one language-variety in mundane mass-media communication and in everyday life from global-South settings. Such routine communication constitutes dominating human behaviour across the world, but is – in large measure – not recognised in Eurocentric discourses (Hasnain, Bagga-Gupta, & Mohan, Citation2013; Sridhar, Citation1996). In both examples, a participant deploys resources from what is recognised as oral English (italicised script) and oral Hindi (non-italicised script).

A second central issue (connected to the first) relates to the very deployment of language resources: from an emic i.e. participants’ perspective, the central aim is meaning-making in the communicative enterprise: people language, rather than use bits and pieces from one or more language structures/codes (Khubchandani, Citation1997, Citation1999). Here established concepts like bi/multi-lingual/ism and other ‘boundary-marked and – marking’ newer terminology analysts use is contentious; issues regarding meaning-making take a back-seat when such concepts are deployed (Bagga-Gupta, Citation2012, Citation2014, Citation2017c). Over two decades ago, Sridhar highlighted that the,

terms bilingualism and multilingualism have been used interchangeably in the literature to refer to the knowledge or use of more than one language by an individual or a community […] Bilingualism is a worldwide phenomenon. Most nations have speakers of more than one language. Hundreds of millions of people the world over routinely make use of two or three or four languages in their daily lives. Furthermore, even so-called monolinguals also routinely switch from one language-variety – a regional dialect, the standard language, a specialised register, a formal or informal style, and so on – to another in the course of their daily interactions (Citation1996, p. 47, emphasis in original).

Building further upon theoretical-methodological allegiances, the third issue relates to the choices we analysts have access to when we represent oral talk in scholarly writing. Going beyond an inherent ‘written language bias’ embedded in such an enterprise (Linell, Citation1982), what is salient for present purposes is that we can potentially represent the oral talk, in Utterances 1–2, in the,

Devanagari script (line 1), for instance, if we aim to present/publish in a Hindi medium context,

Roman/Latin script (lines 2–3) if we aim to present/publish in an English medium context, or

Both Roman/Latin and Devanagari scripts (line 4) regardless of the language medium of the context where we aim to present/publish (and if we can ascertain that the large majority of our readership/audience has experiences of the two scripts)

Such choices seem to be shaped by the disciplinary and academic traditions the analyst is situated in, including his/her own experiences with the language-varieties that the scripts are commonly associated with. Line 3, for instance, would not make visible the routine heterogeneity of the utterances, if supportive information regarding the oral use of English (italicised) and Hindi (non-italicised) were not made salient. Furthermore, the two language-varieties-in-use can be highlighted in different ways. In addition to the italicising convention (used in all four lines), the named-language/named-script connection is made explicit in line 4: Hindi is associated with Devanagari and English with the Roman/Latin script. What such choices succeed in doing include making in/visible the routine patterned human condition (Berger & Luckmann, Citation1966) wherein more than one language-variety, register, dialect, etc. are deployed in languaging. Such choices furthermore, (re)create boundaries between named language-varieties and constitute an etic, i.e. non-participants’ (often the analysts’) perspective (Pietikäinen, Kelly-Holmes, Jaffe, & Coupland, Citation2016). While such choices of representation have also emerged as a reaction to a monolingual ethos in Eurocentric scholarship, they succeed in cementing structural boundaries; they also iron out the fluidity of languaging, not least when scholars are unfamiliar with the language-varieties-in-use. Some literature on methodological issues on data from such sites (including multisited ethnography) is emerging. However, transcription conventions that acknowledge and attempt to make visible the mundane nature of semiotics (including a variation of language-varieties and modalities) itself risks in contributing to the (re)creation of boundaries in binary terms: thus, what is French is not Italian, what is verbal is not written, what is signed is not oral, etc. (Bagga-Gupta, Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

Neologisms with prefixes ‘trans’lingualism/languaging and ‘super/hyper’diversity, popular in some academic quarters in the twenty-first century, mark such social conduct. Some scholars in Europe and Anglo-Saxon settings currently mark languaging with prefixes like ‘trans’ driven by an equity agenda related to groups and language-varieties (see section 3.1; García & Lin, Citation2016). That notwithstanding, acknowledging what is glossed as multilingualism, including numerical definitions like first, second, third language-varieties-in-use in spaces like the Indian sub-continent constitute relevant and pertinent issues for scrutiny. Such emerging interest acknowledges and highlights diversity – but no longer as something that is normal; rather it is being recognised in terms of ‘a selling argument’ for aligning the communicative practices in such spaces with newer labels that are popular in policy, scholarship and the media in the global-North.

Some of these concepts have become immensely popular in Swedish spaces. We raise analytically-based concerns regarding the uptake of these concepts in education in Sweden specifically through the analysis of two different data-sets: (i) mapping the trajectories and relationships of, and discussions regarding, key concepts related to linguistic- and identity-heterogeneity in the scholarship, in policy and in professional fields (sections 3.1), and by (ii) illustrating mundane languaging across physical-virtual sites in the global-North/South (section 3.2). Thus, section 3.1 scrutinises languaging within textual data, and section 3.2, including the opening utterances, illustrate languaging in naturally-occurring interactional-data. The emergence of two key concepts in the language sciences literature, particularly in the nation-state of Sweden – ‘translanguaging’Footnote3 (TL) and ‘nyanlända’Footnote4 (NA), including their relationships to other concepts – are mapped (section 3.1). We enquire about the role that such neologisms play within scholarship on the one hand, and in institutional K-12 education on the other hand. The following queries are of interest here:

What assumptions regarding learning and identity do the mobilisation of TL and NA rest upon in the language and educational sciences?

What is their relevance in the institutionalised education of individuals who are framed as bi/multi/pluri/translinguals?

What is the relevance of the deployment of such terminology

in the academic and professional literature?

in the analysis of social practices?

Before presenting the trajectories of these neologisms, some overarching conceptual framings and methodological reflections are addressed.

2. Conceptual issues and analytical–methodological framings

2.1. On concepts. Analytical framings

Aligning ourselves to a socioculturally framed position implies that we both acknowledge that categorisation constitutes a key dimension of all languaging and that categories deployed for pointing to specific issues or behaviours shape – making (in)visible – those issues, behaviours, identity-positions, etc. It is against such a backdrop that neologisms related to language and identity ‘heterogeneity’ become significant. They risk becoming ‘naturalised’ (Säljö, Citation2002), through ‘looping’ (Hacking, Citation1995) and contribute towards taken-for-granted ‘webs-of-understandings’ (Bagga-Gupta, Citation2012, Citation2017a). Webs-of-understandings are constituted by the linked ways in which concepts related to what gets framed as the norm vis-à-vis languaging and identity-positions reinforce one another.

A sociocultural analytical framing takes as a point of departure an on-going epistemological shift in the social sciences. Here performative verb-based framings of concepts pertaining to language and identity are part of this shift, rather than being dimensions of neologisms (Bagga-Gupta, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). They are, in the important distinction Pavlenko (Citationin press) makes, ‘academic terms’ rather than ‘academic slogans’. Thus, languaging and identity-positioningFootnote5 as verbs are related to shifts that have been noted in other scholarly domains where concepts such as matematizing, musicing, culturing, etc. have emerged since the turn of the century. Verb-based epistemologies allow for, in such a stance, transgressing the ‘isms of oppressive boundaries’ (Bagga-Gupta, Citation2017b) including the ‘ISMs of oppression in language education’ (Damian & Zotzmann, Citation2017) that have been naturalised between named language/s or language-varieties, modalities, identity-positions etc.

Boundaries between language-varieties and modalities are interesting for language researchers and they become important in peoples’ lives, particularly when it comes to political endeavours related to language and territorial rights (see examples presented in Hasnain et al., Citation2013; Moss, Citation2017). But outside arenas of a ‘politics of recognition’ (Taylor, Citation1992), including colonial language hegemonies and outside educational institutions, they do not constitute – as Utterances 1–2 highlight – concerns in the mundane meaning-making enterprises of people glossed as bi/multi/pluri/translinguals. Such a decolonial dimension points towards power differentials in scholarship where concepts from global-North spaces hegemonically (re)frame ‘normal-languaging’ in bounded terms. Decoloniality here enables a new critical reflexivity where recent turn-positions contribute towards the epistemological shift highlighted above. For instance, and particularly relevant for present purposes, a Boundary-Turn (Bagga-Gupta, Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2017a), together with a Multilingual-Turn (May, Citation2014), call attention to hegemonic stances and naturalised assumptions that collate towards specific global-North framed webs-of-understandings. In other words, concepts that refer to specific practices and/or categories not only circulate across research, policy, professional sectors and social/mass-media in ways that, themselves, contribute to the very creation of such practices and categories, but these (re)frame such practices and categories in global-South contexts as well. Concepts, in such a line of thought, do not exist independently nor do they emerge ‘by chance’. They constitute instantiations of a process of looping, i.e. the language and terminology used to ‘talk about’ a phenomenon – for instance, bi/multilingualism – contributes to the creation of that very phenomenon. In this sense, decoloniality represents a perspective rather than a spatial or temporal frame in which the geopolitical spaces of Sweden constitute arenas worthy of scrutiny.

With the above as backdrop, a socioculturally framed decolonial perspective allows us to explore TL and NA with the intent of illuminating how such neologisms are accounted for (in scholarship and policy) against the performances of languaging and identity-positionings (as illustrated in Utterances 1–2 and the ‘slices of mundane everyday life’ presented in section 3.2).

Pavlenko’s critical scrutiny of the neologism ‘superdiversity’ in a chapter in ‘Sloganizations in Language Education Discourse’ (in press),Footnote6 has analytical value for our arguments. Taking a critical reflective stance on ‘terminological innovation and academic branding’, Pavlenko focuses upon the emergence and sudden uptake (at least in some academic quarters and institutional sectors) of the neologism superdiversity, highlighting the ‘features that differentiate academic slogans from bona fide academic terms’ (in press, emphasis added). The sudden popularity of superdiversity is accounted for in the following:

In the span of five years, between 2011 and 2016, sociolinguists witnessed the appearance of two (!) books, one special journal issue, one conference and several research projects all bearing the same title Language(s) and superdiversity(ies). Other titles are not far behind, sporting permutations and collocations of superdiversity and the terms linguistic and sociolinguistics […]. This uniformity of the message is a distinguishing feature of marketing campaigns and suggests that the rise of superdiversity is a result of concerted strategic efforts, known as academic branding (Pavlenko, in press).

A final analytical issue of relevance that draws upon a socioculturally framed decolonial position is concerned with a global-North ‘monolingual bias (Bagga-Gupta, Citation2008; Gramling, Citation2016) in the language and educational sciences. Presupposing ‘a self-evidentiary meaning for the term’, Gramling, critically explores ‘a spectrum of ways public discourse diffusely invokes the term monolingualism’ (Citation2016, p. 67, emphasis in original). Significant here is that while an understanding of bilingual-behaviours builds upon the ‘interpretive flexibility’ (Sataøen, Citation2016, p. 4) accorded to the concept bilingualism, it is itself supported by the diffuseness of ‘monolingualism’.

2.2. Methodological framings. Naturalistic data

The study presented here scrutinises current scholarship across geopolitical spaces as well as directives from the national bodies in-charge of schools and teacher education in Sweden. In other words, international and Swedish publications pertaining to the fields of sociolinguistics and migration studies, teacher education journals and national authorities’ directives in the twenty-first century constitute dataset A (; sections 3.1.1, 3.1.2). Dataset B consists of materials (like those presented in Utterances 1–2 and section 3.2) from ethnographic projects we have been involved in.Footnote7 Understanding the circulation of central concepts in policy, research and professional sectors and geopolitical/virtual spaces and recent terminology shifts builds upon analysis of dataset A. Analysis of social practices (dataset B) illuminates the routine ways in which people draw upon resources from different language-modalities (written, oral), including named language-varieties like English, Hindi, Italian, and Swedish.Footnote8

Table 1. Overview of dataset A: publications related to teacher-journals, publishing houses, etc.

Our interest in how the concepts TL and NA are deployed in tandem to refer to what was previously framed in terms of bilingual education and multilingualism was sparked in part during preparations of an in-service course for study counsellors commissioned by The Swedish National Agency for Education. The two concepts were used in all policy documents related to the course, including its learning objectives. We initiated a snowball search and identified other arenas (both educational and research, see ) and documents which, on closer scrutiny, further illuminated the circulation of such central concepts in the literature and policy.

The naturalisation of bilingual-behaviours and bilingual identity-positions, as highlighted above, ‘only in a limited manner recognises that routine ways of meaning-making […] are not only rich sites for research, but that communication here needs to be attended to from multilingual points of departure’ (Bagga-Gupta, Citation2014, p. 92; see also Gal & Irvine, Citation1995; Grosjean, Citation1995; Rosén & Bagga-Gupta, Citation2013). Thus, the analysis here itself takes heterogeneous language and identity as points of departure, in that we – the analysts – have experiences with the language-varieties and modalities that we focus upon from projects we are/have been engaged in across the global-North/South, including textual and virtual spaces.

3. Nomenclature trajectories versus normal-languaging and normal-diversity

This analytical section first maps the movements and the webs-of-understandings related to the concepts TL and NA across time and space (3.1) before presenting a slice of interactional data from a virtual classroom (3.2).

3.1. Conceptual trajectories and relationships

3.1.1. Popular concepts across time and space

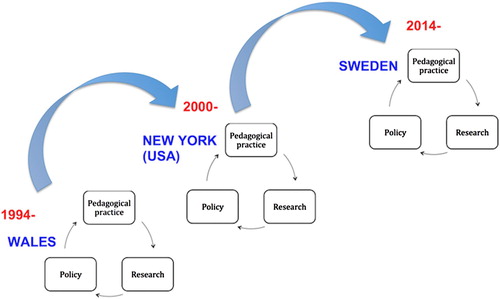

In comparison to the analytically framed concept languaging, the prefixed nomenclature TL emerges in the context of education:

The origins of the term go back to bilingual education in Wales, where the term trawsieithu Footnote9 was used to refer to the planned pedagogical use inside one lesson for receiving information in one language and for producing output in another, to make full use of the bilingual capacity of the students (Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2015, p. 55, emphasis added).

a reaction against the historic separation of two ‘monolingualisms’ (Welsh and English) with a difference in prestige […] When Welsh language revitalisation began to become successful in the final decades of the twentieth century, it opened up the possibility of the two languages being seen as mutually advantageous in a bilingual school, person, and society (642, emphasis added).

is more appropriate for children who have a reasonably good grasp of both languages, and may not be valuable in a classroom when children are in the early stages of learning and developing their second language. It is a strategy for retaining and developing bilingualism rather than for the initial teaching of the second language (644).

The patterned ways in which individuals use more than one language-variety are further recognised through other conceptually looped older concepts/neologisms like pluri/trans/metro-lingual, pluri/trans/poly/multi/hybrid-languaging, code-mixing/meshing, bi-lingual/literacy, second language in the literature. While many of these attempts recognise the patterned fluid, complex norms of languaging,Footnote13 some issues can be noted for present purposes.

First, while many proponents of TL make parallel use of the concept bilingualism in their writings, sometimes together with extensions, e.g. ‘flexible bilingualism’, the deployment of TL (re)frames bilingualism more positively. Second, TL (including other neologisms highlighted above) attempts to mark a shift from bounded understandings of codes to a fluid, complex, hybrid understanding that is (at least theoretically) related to communication and languaging broadly. Third, these neologisms emerge in places within the global-North, and are led by scholars from the global-North. While a growing body of dissertations, reports and volumes by junior scholars from the global-South (working under and together with senior scholars from the global-North) take up these neologisms, work by senior scholars from the global-South finds marginal resonance in explorations of TL (or for that matter, neologisms like ‘super/hyperdiversity’). Fourth, the prefix ‘trans’ currently seems to be experiencing a renaissance: proponents of TL (for instance, García, Li Wei, etc.) have called for ‘trans’-formative/cending powers of TL, the ‘trans’-glossic nature of ‘societal bilingualism’, the need for ‘trans’-disciplinary research into TL, etc.Footnote14 This academic branding tendency notwithstanding, it is worth noting that not all scholarship in the Anglo-Saxon and Swedish contexts – takes on-board neologisms like TL (or ‘super/hyperdiversity’).

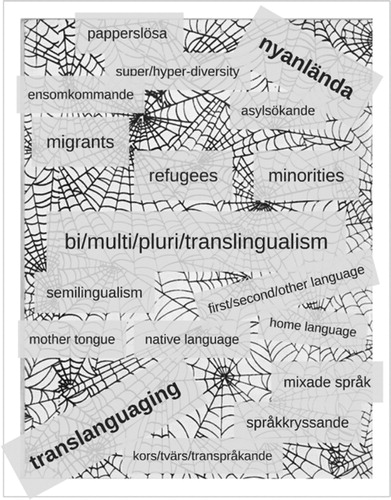

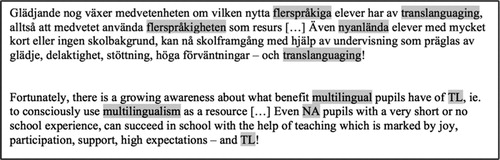

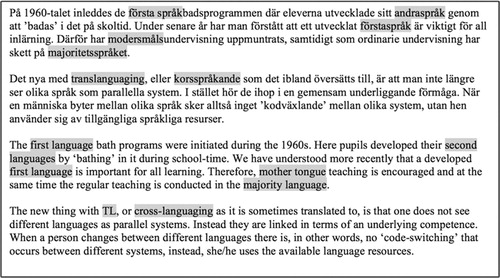

Ofelia García's participation at research activities in a couple of universities in Sweden in 2014 introduced and stimulated an interest in the concept TL in Swedish spaces. In addition to García and Li Wei's (Citation2014) book translated into Swedish (by Christian Nilsson), published in February 2018,Footnote15 a debate ensued regarding appropriate Swedish translations (SIC) of TL. This debate is, since 2016, taking place primarily in the journal LiSetten of LiSA, the National Teachers Association for Swedish as a Second Language (Riksförbundet lärare i svenska som andraspråk). The first number of LiSetten in 2017 builds on the theme ‘Translanguaging i praktiken’ (Translanguaging in practice). represents the looping of TL and NA with other terminology, presenting a member’s solicited text, published online on 12 April 2017.

Figure 1. Looping of terminology related to TL and NA (https://hjrtatskogshaga.wordpress.com/2017/04/12/translanguaing-i-praktiken/).

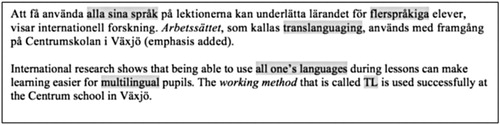

In addition to looping of nomenclature, a significant shift can be noted vis-à-vis the target group that was originally said to benefit by TL: from ‘it is appropriate for children who have a reasonably good grasp of both languages’ (Lewis et al., Citation2012, 644), to ‘even NA pupils [in Sweden …] can achieve success in [the Swedish] school with the help of […] TL’ (). Furthermore, a new ‘Nätverk för Translanguaging’ (Network for Translanguaging), established in 2015, has already organised two conferences (in 2015 and 2017), both of which have/are resulting in publications.

Debates in LiSetten (and other teacher journals like ‘Grundskoletidningen’ [(Compulsory School Journal) 6:2016] and ‘Pedagogiska magasinet’ [(The Pedagogical Magazine) 1:2016]) about appropriate Swedish translations for TL (SIC) have been heated. Translation suggestions include: ‘korspråkande’ (cross-languaging; Drewsen & Kindenberg 4:2015), ‘tvärspråkande’ and ‘språkkryssande’ (translanguaging and language-crossing; Ullholm 1:2016), ‘transspråkande’ (translanguaging; Nätverket för Translanguaging 2:2016 and 9,1:2017), and ‘flerspråkande’ (multilanguaging; Kindenberg, Lindqvist & György 1:2017).

The most recent debate article (LiSetten 1:2017) offers interesting arguments against the suggestion offered by Nätverket för Translanguaging, one of which is the association of the prefix trans with ‘transsexual’ and ‘transvestite’. The authors argue that the Swedish slang ‘transa’ (31) is ‘too distracting to be taken seriously’ by school professionals. They highlight the ‘importance of finding a word that teachers can feel comfortable with, not least since we want the concept to become the entire schools’ affair’ (emphasis added).Footnote16 Offering the term ‘flerspråkande’ (multilanguaging), they argue that in addition to its easier acceptance by school professionals,

the term currently has, in part, positive connotations. Flerspråkande/TL is a linguistic practice that multilingual people make use of in everyday life, inside and outside the classroom […] we seek a concept that is experienced by teachers as the most natural for them to use when they themselves describe the language situation in their classrooms that goes ‘beyond a boundary marking’ issue. Multilanguaging intuitively feels like the correct conceptFootnote17 (LiSetten 31, 1:2017)

Figure 2. Using all one’s languages (http://pedagogiskamagasinet.se/mixade-sprak-hjalper-eleverna-lara/).

Figure 3. Knowledge sticks (http://pedagogiskamagasinet.se/mixade-sprak-hjalper-eleverna-lara/).

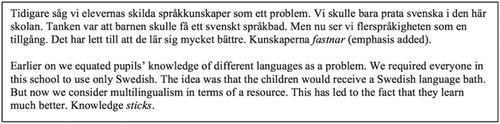

Figure 4. Discussions regarding shifts in ideologies (http://pedagogiskamagasinet.se/mixade-sprak-hjalper-eleverna-lara/).

The researcher profiled in the 2016 article discusses the shift in terms of ‘new’ ideas that TL brings along (). This shift is automatically equated with improved learning: ‘knowledge sticks’ (). Such a shift also followed the introduction of the concept in the international contexts discussed above.

TL and the Swedish concepts ‘korspråkande’ (cross-languaging), ‘tvärspråkande’ (translanguaging), ‘språkkryssande’ (language-crossing), ‘transspråkande’ (translanguaging), and ‘mixade språk’ (mixed language/s) have emerged in the school developmental arena in the areas of bi/multilingual education and Swedish language education for immigrants since 2015. These neologisms are symbiotically related and looped with other concepts like bi/multilingualism, first and second languages, majority language, including NA and the webs-of-understandings related to the latter () (grey marked concepts in , , ). Scholars who have popularised these concepts are engaged in school developmental work and have established collaborations with Swedish national educational agencies.

Here the creation of the concept ‘halvspråkighet’ (literally ‘half-lingualism’) is interesting; the concept was taken up in the international literature as ‘semilingualism’) that Swedish scholars are credited with. Originating in the mid-1970s (Hansegard, Citation1975), it enjoyed some popularity initially. Its uptake internationallyFootnote19 was however short-lived.

Unlike TL’s trajectory that can be traced from the international arena to Swedish spaces during the last few years (), the concept NA seems to emerge from within the geopolitical spaces of Sweden. It emerges during the second decade of the twenty-first century and perhaps gets established in the educational arena in sync with the latest wave of refugee migration into Sweden in 2015. We cannot identify any discussions on the appropriateness of NA as the label for young or older people who are refugees or migrants in Sweden. The concept is nevertheless part of a web-of-understandings () where other identity-positions are used symbiotically. Some of these include, ‘papperslösa barn’ (paperless/undocumented child), ‘ensamkommande barn’ (unaccompanied child), ‘asylsökande barn’ (asylum-seeking child), ‘barn som vistas i Sverige utan tillstånd’ (child who stays in Sweden without permission).Footnote20

While concepts like refugees (flykting) and immigrants (migranter, invandrare) were used for the categories that are now labelled NA, the latter is most closely related to the newness connected with the latest migration waves into Sweden. Here previous inventions of related concepts are illuminating. For instance, Shumsky (Citation2008) traces the emergence of the concept ‘immigration’, going back to Samuel Johnsons 1755 Dictionary of the English Language wherein ‘migration’ is defined as ‘an act of changing place’. Shumsky credits Noah Websters 1828 edition of An American Dictionary of the English Language for populating the concept with a new sense wherein space, time and purpose became key: migration now becomes ‘To remove into a country for the purpose of permanent residence’. NA is related to the latter sense. A neologism in the European context that is aligned with the Swedish NA, is ‘newspeakers/ism’. Vigouroux (Citation2017) highlights that it constitutes a (re)new(ed) critique of ‘nativespeakerism’:

Like most linguistic notions in currency in the literature, that of ‘new speaker’ was born out of language dynamics in the European context. The notion is intended to get rid of the ideological burden of ‘nativespeakerism’, which usually indexes ownership, legitimacy, authority, and authenticity over one’s heritage language. In fact, it has begged the question of whether fluent nonnative varieties are less, or not, legitimate. The idealized notion of ‘native speaker’ also points to the intrinsic indexical nature of language as a national or group identity marker (http://www.ces.uc.pt/coimbranewspeakers/index.php?id=14836&id_lingua=2&pag=162054/7 2017).

3.1.2. TL and NA in Sweden: books, policy and research

The sudden recent popularity of TL and NA in Swedish spaces can also be gauged from book titles and in-service courses (). Systematic searchers of the homepages of five Swedish publishers, whose titles are popular within teacher education, show that this literature starts emerging in 2017 in the case of TL and 2015 in the case of NA ().

Table 2. TL and NA books published in Sweden (searches conducted 1–6 July 2017).

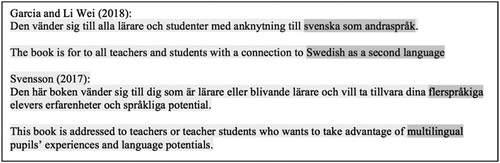

The publicity materials related to the two books with TL in their titles, published at the end of 2017 and in early 2018, target specific professionals ().

Figure 7. Publishing houses publicity materials for new volumes that centre-stage TL (https://www.nok.se/Akademisk/Titlar/Pedagogik/Lararutbildning/)

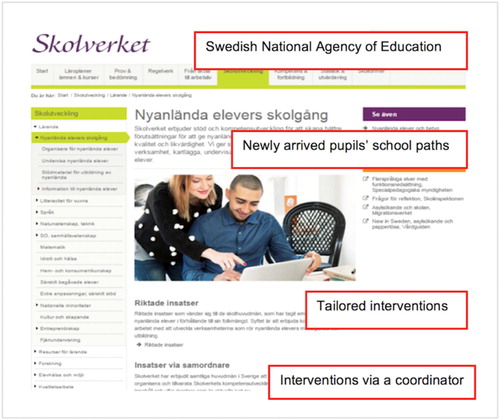

The circulation of the concept NA is prominent in the homepages of different national and regional agencies and authorities. These include the homepages of,

The Swedish National Agency for Education (Skolverket; ),

municipalities or regional bodies responsible for the support and accommodation of children and adults who are migrants and refugees,

the Swedish school inspectorate, and

the Swedish association of local authorities and regions (Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting, SKL).

The title of the homepage of The Swedish National Agency for Education, Nyanlända elevernas skolgång (NA pupils’ school pathways; ) is followed by a text and a picture that account for and illustrate the types of ‘stöd’ (support) and ‘riktade insatser’ (tailored interventions) for including immigrant/refugee pupils in school educational activities.

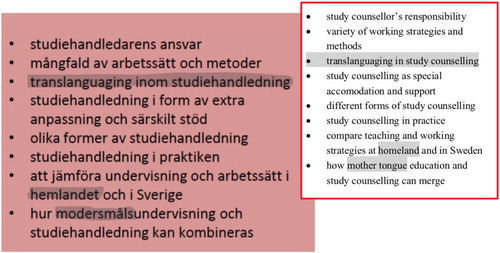

Concepts like TL and NA recently start dominating The Swedish National Agency for Education's formulations wherein looped webs-of-understandings get established. For instance, the term ‘studiehandledare’ – in an invitation for mother-tongue teachers and study counsellors for an in-service conference () – refers to a recently created professional group that has emerged with the purpose of supporting NA pupils in the curriculum subject ‘Swedish as a second language’. Such a naturalisation and looping of inter-related new and old terminology creates specific understandings. While the term ‘studiehandledare’ is broad, it includes both support for learning the ‘doing of schooling’ (Bergqvist, Citation1990), but also learning of Swedish specifically. While ‘studiehandledning’ can be translated as study supervision or scaffolding, discourses about NA and studiehandledning tend to focus this groups’ ‘mother-tongue’.

The Swedish National Agency for Education began commissioning tailored courses for teachers, study counsellors and mother-tongue teachers (delivered through university departments) from 2015 onwards. An important aim of the in-service education for teaching NA pupils was to disseminate knowledge about ‘TL inom studiehandledning’ (TL in study counselling/scaffolding; ). The term TL is framed in terms of a teacher’s professional competence for the purposes of dealing with educational practices where many language-varieties are used.

Figure 9. Mother-tongue–TL–Multilingual. The Swedish National Agency for Education in-service conference invitation, March 2017.

Figure 10. Webs-of-understandings: TL–studiehandledning home country–mother-tongue (The Swedish National Agency for Education, August 2016).

Another indicator of the recent mobilisation of these neologisms can be discerned in research applications to funding agencies. For instance, a search in the database of the Swedish Research Council identified four research projects with NA in the title approved during the period 2006–2016. The emergence of NA in this context points to the politics of academia wherein the use of such neologisms become part of the researchers’ performance of his/her alignment with current societal needs and debates through the distribution of national research grants.

The sudden and broad mobilisation of TL and NA across a large number of contexts in Swedish geopolitical spaces highlights a branding agenda that is in line with Pavlenko’s critique. While the construct TL in terms of a pedagogical practice (as postulated by García & Li Wei, Citation2014) could have merit, it is in need of academic scrutiny if it is to avoid falling into the trap that reinforces boundaries that it purports to erase. TL and NA have been warmly embraced by some Swedish pedagogical research(ers) and practitioners as glossed terms that are implicitly anchored in international literature and current school realities wherein ‘normal’-languaging challenges the longstanding monoglossic, monolingual norm of the Swedish school system. Despite previous waves of migration into the nation-state of Sweden – that has seen periodical peaks since the 1950s – it is the most recent waves in 2015 that gives rise to a ‘uniformity of the message’ through the sudden mobilisation of specific concepts; the trajectories of mobilisation of neologisms presented above are illustrative of the ‘features that differentiate academic slogans from bona fide academic terms’ (Pavlenko, in press).

Returning to the issues raised in relation to the naturalistic data presented in Utterances 1–2, the next sub-section discusses empirical data that illustrate the everyday, mundane flavour of meaning-making in settings that get framed as exceptionally diverse languaging settings. Our choice of data here builds upon the naturalised understanding that digitalisation per se contributes to a super/hyper/-diverse human condition. We illustrate and argue that analysis of such data at the micro-scale allows for upfronting the study and representation of languaging where the use of a range of semiotic resources is a sine qua non condition. This, we show, is similar to the opening languaging examples which illustrated meaning-making in analogue settings.

3.2. Languaging: further empirical examples of chaining across language-varieties/modalities

Our previous and current work contributes to scholarship on languaging through its explication of the ways in which language-varieties and modalities, including written, oral, signed and embodied resources are deployed in communication. Going beyond the empirical work we have reported previously, the present study raises issues regarding popular neologisms in the language and educational sectors, opening up for analytically framed perspectives.

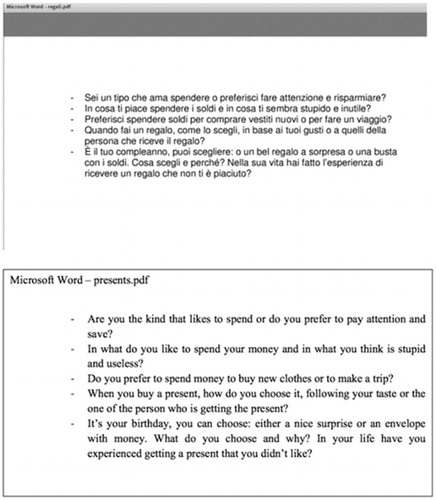

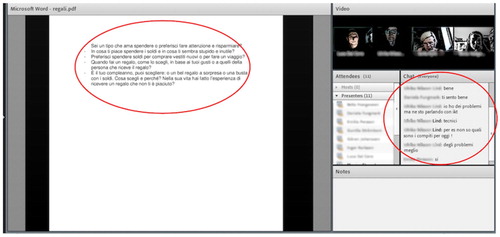

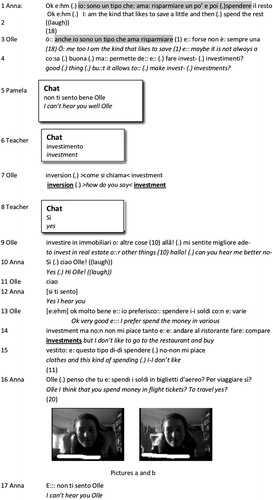

Here we focus upon a slice of interactional material where a group of university students are interacting in and through the videoconferencing platform Adobe Connect (). This transpires half-way through a one-hour long meeting where the participants have been tasked to discuss their shopping and spending habits. While the task is framed within an Italian for beginners’ university course in the nation-state of Sweden, the students and the teacher are dispersed across physical locations, both inside and outside nation-state boundaries. The circles in highlight the text on the White Board (WB) and on the chat-tool that is publicly displayed in the environment where participants interact during synchronous meetings. Anna, a student, takes the floor in line 1 ().

Figure 11. The videoconferencing platform Adobe Connect used for Italian for beginners’ course (CINLE project).

Figure 12. Representation of interaction in an online classroom synchronous meeting. Pictures a-b: Anna displaying that she cannot hear Olle.

Note: The original languaging is displayed in this excerpt. A verbatim translation is provided under each line. The different language-varieties are represented in italics (Italian) and bold underlined (English).

Anna ventriloquises the first written sentence in the text displayed on the WB (line 1, grey highlighted, see also Appendix). After 18 s of silence, Olle initiates a similar turn-at-talk, linked to Anna’s previous contribution by the adverbial ‘anche’ (also). However, the agent-mediational means symbiosis gets disrupted by (i) Olle’s limited experience with the language-variety Italian, as he explores meanings of the word item ‘investment’ (line 7 onwards), and (ii) sound issues in the virtual learning space.

The participants orient towards the disruptions by using different modalities, oral, written and gestural (through the web-cam; Picture 12 a-b). This creates multi-layered languaging where we analysts can identify repetitions, overlapping talk, long silences and multiple, simultaneous conversational floors. Such behaviours constitute normal-languaging. Anna’s gestures (Picture 12 a-b), after a 20 s long silence during Olle’s turn (with contributions from the other participants) displays that she can’t hear, as well as her uncertainty about the interactional trajectory (Sacks, Citation1984): Am I still online? Are you online? Should I take the floor etc. Anna confirms Olle’s presence in the oral mode and poses direct questions to Olle (using vocatives in lines 16–17). She thus distributes turns-at-talk and orients towards the position of an expert user of both the technology and the mediational means embedded in it.Footnote21

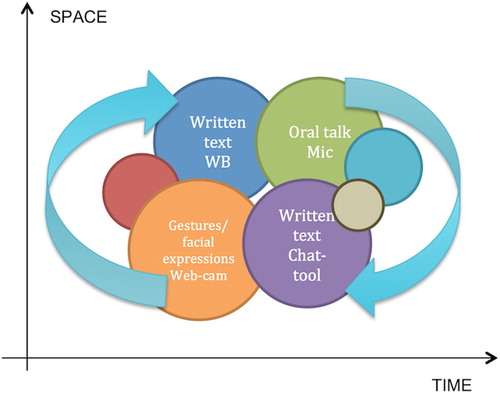

Thus, the interaction order represented in makes visible the proliferation of mediational means in and across virtual/physical spaces. Here different language-varieties, modalities and communicative affordances/spaces are upfronted (see also Utterances 1–2). This multilayered nature of languaging in online learning environments is re-represented at an overarching level in .

Figure 13. Normal-languaging repertoires in virtual learning sites. Overlapping and chaining across time and space.

The ordinariness of meaning-making in such language-focused learning settings includes chaining across modalities and language-varieties. However, complex languaging is a pre-requisite, rather than a consequence, for meaning-making. This is, we argue, a phenomenon that unravels both on a temporal axis (sequentiality) and on a spatial axis. The latter indexes the simultaneity of languaging across linguistic repertoires, including modalities; i.e. not only what/when something is said/written/shown semiotically, but also where and in relation to what this is evoked.Footnote22 This argument is important for present purposes: it highlights how the looping of notions like TL are pedagogical and prescriptive, rather than analytical and descriptive. We suggest that the latter are a pre-requisite for a better understanding of the phenomenon under scrutiny where the analytical focus is on the investigation of the interaction in situ from non-ideological positions. In such a line of thought, TL and the webs-of-understandings that it generates (and is linked to), run the risk of reifying a process that should not be seen as a purpose in itself, but rather as something that is a dimension of all languaging.

4. Communication = languaging = meaning-making

Our previous studies have focused upon data generated inside, outside and across institutional learning contexts in and across the global-North and the global-South.Footnote23 This research has contributed in specific ways to the ongoing discussions regarding bounded language-varieties and/or modalities. Our work has for instance, shown that languaging is marked by chaining, fluidity and a continuum across named language-varieties and modalities in the meaning-making enterprises that pupils and adults are engaged in across a range of social practices. Utterances 1–2 illustrate such features of communication as well as the ordinariness of the complexities that scholars in the global-North can no longer ignore. Academic branding and sloganism notwithstanding, the deployment of newer (problematic) nomenclature like TA and NA can be seen as attempts to go beyond taken for granted, essentialist, monolingual positions (see also Dovchin, Citation2017).Footnote24 This recent nomenclature can be compared with ‘academic terms’ that have emerged over time. For instance, analytical concepts like chaining and ‘linking’ have emerged from the field of bilingualism in the Deaf Studies scholarship since the 1990s (Bagga-Gupta Citation1999, Citation2002, Citation2004; Humphries & MacDougall, Citation1999; Padden, Citation1996) and have started contributing to dialogues in the mainstream bilingual scholarship (Gynne, Citation2016; Messina Dahlberg, Citation2015). Chaining explicates meaning-making and performative aspects of communication, i.e. language is something that gets done in a given context and situation in concert with a range of artifacts. As argued above, such analytically framed concepts attempt to ‘go beyond’ bounded notions of named language-varieties and modalities and are in sync with the fluid nature of languaging. This contrasts with the webs-of-understandings related to bi/multilingualism (Bagga-Gupta, Citation2012, Citation2017a) that include old and newer terminology such as migrants, newspeakerism, translanguaging, nyanlända, etc.

The study presented in this paper explicitly brings together some key common theoretical assumptions that underlie the compartmentalised scholarship in domains such as bilingual studies, SLA, foreign languages, signed communication, mother-tongue instruction etc. in the language and educational sciences. Analysis of a range of materials that constitute dataset A () highlights that concepts like nyanlända, newly-arrived and translanguaging (including the latter’s translations into Swedish), have suddenly become key pedagogical constructs in the Swedish educational landscape in terms of a discourse of ‘good’ language pedagogy for a particular pupil population. Our analysis also indicates a curious critical lack of analytical discussions regarding neologisms that target individuals or classrooms where more than one language-variety and modality are deployed. This is the case in both the international and Swedish scholarship. Despite the linguistic- and performatory-turns (that have shaped the scholarship in identity and language domains), it is paradoxical that prefixes like bi/multi/trans/super/hyper, etc. have suddenly become popular in the language sciences, including policy in the twenty-first century.

A focus upon the mobilisation and trajectories of neologisms like TL and NA illuminate institutional professional practices wherein pupils are defined in terms of age, abilities, specific background factors etc. Such processes of definitions and bracketing have significant, and not uncommonly undesirable, repercussions for the marked pupils’ education, including transitions into adulthood. Scholarship on metaphors and nomenclature ‘we live by’ (Lakoff & Johnson, Citation1980), including looping and naturalisation, highlights a circularity in the usage of concepts within academic sectors on the one hand, and professional domains of governance, schools and teacher education on the other hand.

In contrast, the chained character of on-the-ground and on-the-move repertoires of languaging that emerge from the analysis of dataset B challenges dominant discourses regarding bounded named language and identity. Our empirically pushed analysis questions the normatively framed webs-of-understandings that continue to shape the organisation of inclusion/integration and exclusion/segregation in educational settings in contemporary Sweden.

While the ‘messiness’ of communication and the intrinsic performance that includes a range of modalities and repertoires is recognised and discussed across different academic fields (sociolinguistics, linguistic anthropology and the language sciences more broadly), such complexities appear to become an issue when the focus turns towards the study of communication generally and the study of bilingual communication specifically within learning instructional practices. The issue at stake is, we argue, multifold: where should the analytical gaze be directed in such studies?; how does one avoid falling into the trap of idealising diversity and complexity as goals in themselves? and, how does one avoid returning to traditional conceptualizations of language as mental and/or abstract phenomena that reside in ‘(bilingual) peoples’ heads’? A focus on social practices, which is a cornerstone in conceptualizations of TL, entails an understanding of the use of complex semiotics as the ‘norm’ of human communication and existence. This norm, we maintain, does not benefit from prefixes like trans/super/hyper; on the contrary, such prefixes index boundaries that build upon a monolingual norm position.

In contrast, analytically framed questions need to focus on what and why we analysts need to focus upon in research when face-to-face or digitally-framed social interaction – irrespective of the mono, bi, multi, nature of the communication repertoires of the participants – is scrutinised. In other words, we analysts need to constantly be wary of the limitations and challenges embedded in research endeavours that purport to support language learning in minority groups. Such challenges centrally include the multi-layered issues highlighted above. They also include issues related to embodied dimensions of communication such as, for instance, gestures, pitch, prosody, facial expressions, and corporality such as vision, smell, touch etc. that are not, traditionally, included in the analysis (see also Ensslin, Citation2017; Finnegan, Citation2015; Linell, Citation2009).

The use of prefixes like trans/bi/multi has been important primarily from global-North perspectives. Given their monoglossic, monolingual premises, they build upon shifts in nomenclature but remain normative, failing to contribute towards analytical rigour in the study of communicative practices. The implication of this argument is that nomenclature like translanguaging, newly-arrived, etc., when related to school practices, run the risk of becoming new, empty popular concepts in the global-North, embraced across a variety of fields by both researchers and practitioners. Such shifts as well as the embracement of such terminology, we argue, constitutes a counter-productive, short-sighted project that neither describes nor analytically illuminates the activity of meaning-making marked by normal-languaging and normal-diversity as is the case across the global-South. As Savransky (Citation2017) succinctly argues,

the epistemological Eurocentrism of critical theory demands […] of us that we risk imagining an entirely different relationship between knowledge and reality (18, emphasis in original).

The plethora of research projects and publications on TL, NA in Sweden and TL and superdiversity internationally that have emerged within a short time-span constitute responses to what is being understood in global-North contexts as ‘new’ challenges for society. As the analysis presented in this study illustrates, this too constitutes looping and circularity – between research, policy and professional sectors. The connections that such circularity promotes is used to establish networks where new concepts can be ‘launched’ and used with connotations that have undergone a process of metamorphosis: in the mid-1990s, TL emerged with the ambition of according recognition to the communicative practices of individuals who were functionally bilingual inside schools in Wales; its uptake in the east-coast of the United States also had a recognising agenda; however, TL in the second decade of the twenty-first century has become a method for teaching the majority societal language to refugees and immigrants in Sweden.

The current commission of tailored courses for teachers in Sweden who have the explicit aim of promoting the distribution of knowledge and skills about Swedish constitutes only one of many examples of the growing mobilisation of terminology that attends to apparently new communicative practices that we argue is ‘mundane, normal, complex’ languaging. In other words, the study presented here specifically asks how concepts like bilingualism and translanguaging differ from what is normal-languaging, and what concepts like superdiversity, hyperdiversity, newspeakerism and newly-arrived offer in comparison to normal-diversity? What, in other words, we ask is normal-languaging and normal-diversity?

Human communication is always messy and its study always entails challenges, both from analytical and methodological perspectives. Its complexity and messiness need recognition as the norm, rather than something that needs to be fixed for others. We propose, in all its triviality and mundaneness, that there is merit in fixing our analytical gaze at the meaning-making of participants, irrespective of how many language-varieties/modalities and other resources they deploy. Such an enterprise necessitates that we analysts ourselves share those meaning-making resources, if we are to avoid contributing to Othering processes, including sloganism within scholarship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Our own fieldwork in project GTGS (www.ju.se/ccd/gtgs) in Indian so called multilingual geopolitical spaces since the 1990s, highlights a shift in that today the concept ‘bilingual/ism’ is deployed by scholars in some Indian settings; however, the use of such old and new boundary-marking/marked concepts is alien for ordinary people who use at least three to five named language-varieties in the course of their everyday lives (see Bagga-Gupta, Citation1995; see Street, Citation1984 for a parallel ethnographic example from another geopolitical space where a number of named language-varieties were deployed regularly in peoples everyday lives).

2. A number of research projects that focus on the analysis of communicative practices in which more than one named language-variety/modality are deployed are part of the Communication, Culture and Diversity (CCD) network-based research environment at Jönköping University, Sweden. These projects have been important points of departure for the deliberations that are presented in this study (see also www.ju.se/ccd; see Gynne & Bagga-Gupta, Citation2015; Holmström, Bagga-Gupta, & Jonsson, Citation2015; Messina Dahlberg & Bagga-Gupta, Citation2016).

3. Various Swedish terms have been suggested for translating this concept since 2015: korsspråkande, språkkryssande, tvärspråkande, transspråkande. See further below.

4. This Swedish concept roughly translates to ‘newly-arrived’. See further below.

5. What we have termed ‘identiting’ or the doing of identity (Bagga-Gupta, Feilberg, & Hansen, Citation2017).

6. First presented at a conference with the same name in Berlin in 2014.

7. These empirical illustrations are drawn from the following projects: (i) CINLE, Studies of everyday communication and identity processes in netbased learning environments, (ii) EL, Everyday Life Archive, (iii) GTGS, Gender Talk Gender Spaces, (iv) LPLM, Läroplan-Läromedel (Curriculum-Textual Archives). See www.ju.se/ccd

8. Wary of conceptional framings of language and communication as codes, we nevertheless refer to named language-varieties from an etic perspective in our analysis of languaging. This is not unproblematic and requires critical reflexivity in the very doing of research, not least in the processes of data-creation, representation and analysis (for further deliberations on this issue see Bagga-Gupta, Messina Dahlberg, & Gynne, Citationin press; Finnegan, Citation2015; Makoni, Citation2012; Pietikäinen et al., Citation2016).

9. We refrain from directly translating key concepts and attempt to present original languaging data when ever possible in our studies (see section 1). This makes available the richness and complexity of the data, in parallel to our translations.

10. Arfarniad o Ddulliau Dysgu ac Addysgu yng Nghyd-destun Addysg Uwchradd Ddwyieithog, [An evaluation of learning and teaching methods in the context of bilingual secondary education]. Bangor University, Bangor, UK.

11. We acknowledge Dr. Bryn Jones, Bangor University, Bangor, UK, input in tweezing out this concept (personal communication).

12. The third author in the trio Lewis, Jones and Baker.

13. While TL proponents like Lewis et al. (Citation2012) focus ‘on conceptualising translanguaging including its relation to other flexible language arrangements such as code-switching, co-languaging and translation’ (655), García and Lin (and others like Canagarajah, Citation2011), propose a clear-cut difference between TL and code-switching: TL, they maintain

refers not simply to a shift or a shuttle between two languages, but to the speakers’ construction and use of original and complex interrelated discursive practices that cannot be easily assigned to one or another traditional definition of language, but that make up the speakers’ complete language repertoire (2014, p. 22).

14. This seems to have also inspired the import of TL by some into Swedish spaces.

15. Translanguaging. Flerspråkighet som resurs i klassrummet [TL. Multilingualism as a resource in the classroom]. Publisher Natur & Kultur https://www.nok.se/Akademisk/Titlar/Pedagogik/Lararutbildning/Translanguaging1/ (1/7 2017).

16. ‘viktigt att hitta ett ord som lärare kan känna sig bekväma med, inte minst om vi vill göra det till hela skolans angelägenhet’.

17. ‘en term som numera mestadels har positiva konnotationer. Flerspråkande/translanguaging är en språklig praktik som flerspråkiga personer använder sig av i vardagen, i och utanför klassrummet […] vi söker det begrepp som det känns mest naturligt att lärare tar i sin mun när de själva ska beskriva en språkanvändningssituation i klassrummet ’bortom existerande gränsdragningar’. Flerspråkande känns intuitivt som det begreppet’.

18. ‘Translanguaging har ofta i svenska sammanhang betecknats som en undervisningsstrategi där man medvetet utnyttjar elevernas flerspråkiga resurser i klassrummet’.

19. It was popularised through the English writings of the language scholar T. Skutnabb-Kangas from Denmark in her 1981 book ‘Bilingualism or not: The education of minorities’. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

20. See also Section 3.1.2 below.

21. Such conduct is in line with research on technology-mediated communication which highlights similar affordances and hinders. This kind of orchestration of meaning-making across modalities, as well as the representational challenges that come with such kinds of transcripts has also been discussed in the literature (see Hampel, Citation2006; Helm, Citation2016; Liddicoat, Citation2011).

22. On a methodological note, the praxis of analysis and transcription has however historically privileged written, sequential transcripts. Only in more recent years, and with the advent of video recordings, has this trend shifted towards transcripts that aim to illustrate simultaneity across modalities as well (see for instance Bagga-Gupta & St-John, Citation2017; Goodwin, Citation1993; Malcom & Darren, Citation2000). Chaining, we argue, is a contribution towards this direction and body of literature.

23. See some of our studies in the reference list.

24. While this is being written the International Journal of Multilingualism has circulated a call for papers with the title: ‘the ordinariness of translinguistics’ (guest editors Sender Dovchin and Jerry Lee). Interestingly, the preference for the noun translinguistics, rather than the verb translanguaging, may be understood as an attempt to reify the phenomenon of TL that can also take away its pedagogical, normative flavour. Translinguistics refers to a research field, thus taking the discussion forward to an analytical level. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B4M4c7QGEuLoLUFFc1RMYWNsUDQ/view (27/8 2017).

References

- Bagga-Gupta, S. (1995). Human development and institutional practices: Women, child care and the mobile creches (Doctoral Dissertation). Linköping Studies in Arts and Sciences 130. Linköping University, Sweden.

- Bagga-Gupta, S. (1999). Visual language environments: exploring everyday life and literacies in Swedish deaf bilingual schools. Visual Anthropology Review, 15(2), 95–120. doi: 10.1525/var.2000.15.2.95

- Bagga-Gupta, S. (2002). Explorations in bilingual instructional interaction: A sociocultural perspective on literacy. Learning and Instruction, 12(5), 557–587. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4752(01)00032-9

- Bagga-Gupta, S. (2004). Visually oriented bilingualism. Discursive and technological resources in Swedish deaf pedagogical arenas. In M. van Herreweghe & M. Vermeerbergen (Eds.), To the lexicon and beyond. Sociolinguistics in European deaf communities, volume 10 – The sociolinguistics in deaf communities series (Ed. Ceil Lucas), 171–207. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Bagga-Gupta, S. (2008). Den enspråkiga människan och den enfaldiga skolan. Var finns de? [The monolingual human being and the homogenous/monocultural school. Where are they?]. Professors installation speech. Sweden: Örebro University.

- Bagga-Gupta, S. (2012). Challenging understandings of bilingualism in the language sciences from the lens of research that focuses social practices. In E. Hjörne, G. van der Aalsvoort, & G. de Abreu (Eds.), Learning, social interaction and diversity: Exploring school practices (pp. 85–102). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Bagga-Gupta, S. (2013). The boundary-turn: Relocating language, culture and identity through the epistemological lenses of time, space and social interactions. In I. Husnain, S. Bagga-Gupta, & S. Mohan (Eds.), Alternative voices: (Re)searching language, culture and identity (pp. 28–49). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Bagga-Gupta, S. (2014). Performing and accounting language and identity: Agency as actors-in-(inter)action-with-tools. In P. Deters, X. Gao, E. Miller, & G. Vitanova-Haralampiev (Eds.), Theorizing and analyzing agency in second language learning: Interdisciplinary approaches (pp. 113–132). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Bagga-Gupta, S. (2017a). Center-staging language and identity from earthrise positions. Contextualizing performances from open spaces. In S. Bagga-Gupta, A. L. Hansen, & J. Feilberg (Eds.), Identity revisited and reimagined. Empirical and theoretical contributions on embodied communication across time and space (pp. 65–102). Rotterdam: Springer Publishing.

- Bagga-Gupta, S. (2017b). Language and identity beyond the mainstream. Democratic and equity issues for and by whom, where, when and why. Journal of the European Second Language Association, 1(1), 102–112. doi: 10.22599/jesla.22

- Bagga-Gupta, S. (2017c). Going beyond oral-written-signed-irl-virtual divides. Theorizing Languaging from mind-as-action perspectives. Writing & Pedagogy, 9(1), 49–75. https://doi.org/10.1558/wap.27046

- Bagga-Gupta, S., Messina Dahlberg, G. & Gynne, A. (in press). Handling languaging during fieldwork, analysis and reporting in the 21st century: Aspects of ethnography as action in and across physical-virtual spaces. In Bagga-Gupta, S., Messina Dahlberg, G. & Lindberg, Y. (Eds.). Virtual Learning Sites as Languaging Spaces. Critical issues on languaging research in changing eduscapes in the 21st century. Sense Publishers.

- Bagga-Gupta, S. & St-John, O. (2017). Making complexities (in)visible: Empirically-derived contributions to the scholarly (re)presentations of social interactions. In S. Bagga-Gupta (Ed.), Marginalization processes across different settings: going beyond the mainstream (pp. 352–388). Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Bagga-Gupta, S., Feilberg, J., & Hansen, A. L. (2017). Many ways-of-being across sites. Identity as (inter)action. In S. Bagga-Gupta, A. L. Hansen, & J. Feilberg (Eds.), Identity revisited and reimagined. Empirical and theoretical contributions on embodied communication across time and space (pp. 5–24). Rotterdam: Springer Publishing.

- Baker, C. (2011). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (5th ed.). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality. A treatise in the socioligy of knowledge. New York, NY: Penguin.

- Bergqvist, K. (1990). Doing schoolwork. Task premises and joint activity in the comprehensive classroom (Doctoral dissertation). Linköping Studies in Arts and Science 55. Linköping University, Sweden.

- Canagarajah, S. (2011). Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 401–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01207.x

- Creese, A., & Blackledge, A. (2010). Translanguaging in the bilingual classroom: A pedagogy for learning and teaching? The Modern Language Journal, 94, 103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00986.x

- Damian, J. R., & Zotzmann, K. (Eds.). (2017). ISMS in language education. Oppression, intersectionality and emancipation. Language and Social Life. Boston, MA: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Dovchin, S. (2017). The ordinariness of youth linguascapes in Mongolia. International Journal of Multilingualism, 14(2), 144–159. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2016.1155592

- Ensslin, A. (2017). Future modes: How ‘new’ new media transforms communicative meaning and negotiates relationships. In C. Cotter, & D. Perrin (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language and media (pp. 309–324). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Finnegan, R. (2015). Where is language? An anthropologist’s questions on language, literature and performance. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Gal, S., & Irvine, J. (1995). The boundaries of languages and disciplines: How ideologies construct difference. Social Research, 62, 967–1001.

- García, O., & Li Wei. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- García, O., & Lin, A. M. Y. (2016). Translanguaging in bilingual education. In O. García, A. M. Y. Lin, & S. May (Eds.), Bilingual and multilingual education. Vol. 10. Encyclopedia of language and education (pp. 117–130). Rotterdam: Springer.

- García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Goodwin, C. (1993). Recording human interaction in natural settings. Pragmatics, 3(2), 181–209. doi: 10.1075/prag.3.2.05goo

- Gorter, D., & Cenoz, J. (2015). Translanguaging and linguistic landscapes. Linguistic Landscape, 1(1), 54–74. doi: 10.1075/ll.1.1-2.04gor

- Gramling, D. (2016). The invention of monolingualism. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

- Grosjean, F. (1995). A psycholinguistic approach to code-switching: The recognition of guest words by bilinguals. In L. Milroy, & P. Muysken (Eds.), One speaker, Two languages: Cross-disciplinary perspectives on code-switching (pp. 259–275). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gynne, A. (2016). Languaging and social positioning in multilingual school practices: Studies of Sweden Finnish middle school years (Doctoral dissertation). Mälardalens studies in Educational Sciences 26. Mälardalens university, Sweden.

- Gynne, A., & Bagga-Gupta, S. (2015). Languaging in the twenty-first century: Exploring varieties and modalities in literacies inside and outside learning spaces. Language and Education, 29(6), 509–526. doi: 10.1080/09500782.2015.1053812

- Hacking, I. (1995). The looping effects of human kinds. In D. Sperber, D. Premack, & A. J. Premack (Eds.), Causal cognition: A multidisciplinary debate (pp. 351–383). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Hampel, R. (2006). Rethinking task design for the digital age: A frame-work for language teaching and learning in a synchronous online environment. ReCALL, 18(1), 105–121. doi: 10.1017/S0958344006000711

- Hansegard, N. E. (1975). Bilingualism or semilingualism? Invandrare och Minoriteter, 3, 7–13.

- Hasnain, I., Bagga-Gupta, S., & Mohan, S. (Eds.). (2013). Alternative voices: (re)searching language, culture and identity. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Helm, F. (2016). Facilitated dialogue in online intercultural exchange. In T. Lewis & R. O’Dowd (Eds.), Online intercultural exchange: Policy, pedagogy, practice (vol. 4, pp. 150–172). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Holmström, I., Bagga-Gupta, S., & Jonsson, R. (2015). Communicating and hand(ling) technologies. Everyday life in educational settings where pupils with cochlear implants are mainstreamed. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 25(3), 256–284. doi: 10.1111/jola.12097

- Hornberger, N. H. (2003). Continua of biliteracy. In N. H. Hornberger (Ed.), Continua of biliteracy: An ecological framework for educational policy, research, and practice in multilingual settings (pp. 3–34). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Humphries, T., & MacDougall, F. (1999). ’Chaining’ and other links: Making connections between American sign langauge and english in two types of school setttings. Visual Anthropology Review, 15(2), 84–94.

- Jørgensen, J. N. (2008). Polylingual Languaging around and among children and adolescents. International Journal of Multilingualism, 5(3), 161–176. doi: 10.1080/14790710802387562

- Khubchandani, L. M. (1997). Revisualizing boundaries: A plurilingual ethos (Vol. 3). New Dehli: Sage Publications.

- Khubchandani, L. M. (1999). Speech as an ongoing activity: [Comparing Bhartrhari and Wittgenstein]. Indian Philosophical Quarterly, 26(1), 1–18.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lewis, G., Jones, B., & Baker, C. (2012). Translanguaging: Developing its conceptualisation and contextualisation. Educational Research and Evaluation, 18(7), 655–670. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2012.718490

- Liddicoat, A. J. (2011). Enacting participation: Hybrid modalities in online video conversation. In C. Develotte, R. Kern, & M.-N. Lamy (Eds.), Dé-crire la conversation en ligne: le face à face distanciel (pp. 51–70). Lyon: ENS Éditions.

- Linell, P. (1982). The written language bias in linguistics. Linköping: University of Linköping.

- Linell, P. (2009). Rethinking language, mind, and world dialogically. Interactional and contextual theories of human sense-making. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

- Malcom, A., & Darren, R. (2000). Innocence and nostalgia in conversation analysis: The dynamic relations of tape and transcript. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(3).

- Makoni, S. B. (2012). A critique of language, languaging and supervernacular. Muitas Vozes, 1(2), 189–199. doi: 10.5212/MuitasVozes.v.1i2.0003

- May, S. (Ed.). 2014. The multilingual turn. Implications for SLA, TESOL, and bilingual education. London and New York: Routledge.

- Messina Dahlberg, G. (2015). Languaging in virtual learning sites: Studies of online encounters in the language-focused classroom (Doctoral dissertation). Örebro Studies in Education 49. Örebro University, Sweden.

- Messina Dahlberg, G., & Bagga-Gupta, S. (2016). Mapping languaging in digital spaces: Literacy practices at borderlines. Language Learning & Technology, 20(3), 80–106.

- Moss, S. M. (2017). From political to national identity in zanzibar. Narratives on changes in social practices. In S. Bagga-Gupta, A. L. Hansen, & J. Feilberg (Eds.), Identity revisited and reimagined. Empirical and theoretical contributions on embodied communication across time and space (pp. 169–186). Rotterdam: Springer Publishing.

- Padden, C. (1996). Early bilingual lives of deaf children. In I. Parasnis (Ed.), Cultural and language diversity and the deaf experience (pp. 99–116). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Pavlenko, A. (in press). Superdiversity and why it isn’t. Reflections on terminological innovations and academic branding. In S. Breidbach, L. Küster, & B. Schmenk (Eds.), Sloganizations in language education discourse. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Pietikäinen, S., Kelly-Holmes, H., Jaffe, A., & Coupland, N. (2016). Sociolinguistics from the periphery. Small languages in new circumstances. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rosén, J., & Bagga-Gupta, S. (2013). Shifting identity positions in the development of language education for immigrants: An analysis of discourses associated with ‘Swedish for immigrants’. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 26(1), 68–88. doi: 10.1080/07908318.2013.765889

- Sacks, H. (1984). Notes on methodology. In J. Heritage, & J. Maxwell Atkinson (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 2–27). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sataøen, H. (2016). Transforming the “third mission” in Norwegian higher education institutions: A boundary object theory approach. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62, 1–16.

- Savransky, M. (2017). A decolonial imagination: Sociology, anthropology and the politics of reality. Sociology, 51(1), 11–26. doi: 10.1177/0038038516656983

- Säljö, R. (2002). My brain’s running slow today – The preference for ‘things ontologies’ in research and everyday discourse on human thinking. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 21(4–5), 389–405. doi: 10.1023/A:1019834425526

- Shumsky, N. L. (2008). Noah Webster and the invention of immigration. The New England Quarterly, 81(1), 126–135. doi: 10.1162/tneq.2008.81.1.126

- Sridhar, K. K. (1996). Societal multilingualism. In S. Lee McKay & H. Nancy (Eds.), Sociolinguistics and language teaching (pp. 47–70). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Street, S. V. (1984). Literacy in theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Taylor, C. (1992). The politics of recognition. Multiculturalism and the politics of recognition. A. Gutman. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Vigouroux, C. B. (2017). (Re)thinking newspeakerism from a sub-saharan African perspective. Keynote at The Final New Speakers Network Final Whole Action Conference. Coimbra. Retrieved from http://www.ces.uc.pt/coimbranewspeakers/index.php?id=14836&id_lingua=2&pag=16205