ABSTRACT

This paper draws on a multimodal notion of metrolingualism to discuss playful T-shirt displays of Galician and Basque language, culture and identity. They invite the audience to reflect on notions of Galicianness and Basqueness by mixing localising resources such as minority language and cultural heritage with globalised resources of fluidity, such as the English language, pop-cultural icons, and logos of transnational companies, and by strategically using play and parody. Read against observations of discursive and ideological shifts among other ethnolinguistic minorities, the paper suggests that the metrolingual play in these T-shirts is part of a more general move towards less standardised and homogeneous understandings of smaller and peripheral languages and cultures. A comparison of the sociolinguistic and political situation in Galicia and the Basque Country shows however bigger potential for cross-linguistic and metrolingual play in Galicia than in the Basque Country. The paper concludes by suggesting that increased metrolingualism in public language displays should be seen both as a sign of maturity and as a commercial appropriation and commodification of the minority culture and language. To evaluate the effect of metrolingual play on particular languages and cultures therefore require detailed examinations of local power relations and political economies of language.

1. Introduction

In Galicia and the Basque Country there is a vivid scene of T-shirt designers who rework, often with humour and a critical stance, traditional understandings of local culture, identity, language and place. They frequently depart from vernacular imagery and sayings and mix them up with globalised pop-cultural icons to create something new. Through these T-shirts, social meanings linked to specific forms of the local cultural heritage – ranging from language over food to buildings – are subjected to self-reflexive renegotiation and multimodal performance in the ‘semiotic landscape’ (Jaworski & Thurlow, Citation2010).

By analyzing these displays and their context of production, this paper aims to contribute to the discussion of a move among small and peripheral language communities towards increased reflexivity and creativity (Järlehed & Moriarty, Citation2018; Pietikäinen, Jaffe, Kelly-Holmes, & Coupland, Citation2016), and ‘valuing of play, humour and hybridity’ (Kelly-Holmes, Citation2014, p. 541). Addressing the general concerns of this special issue, the paper discusses the relationship between creativity and normativity, and the sociolinguistic, political and economic affordances of play in these T-shirts. How is the multilingual play and creativity conditioned by local sociolinguistic, political and economic processes of change? What representations of Galicianness and Basqueness are played with and how are they recontextualized? What differences can be observed between the Galician and the Basque T-shirts?

In order to answer these questions, the paper draws on a multimodal critical discourse analysis (Machin, Citation2016) of a combined data-set, comprising field notes and photos of T-shirts and T-shirt stores,Footnote1 as well as interviews with Galician and Basque designers and traders of T-shirts, both my own semi-structured research interviewsFootnote2 and journalistic interviews appearing in local newspapers from 2004 to 2017. For the latter, I searched the principal Galician and Basque newspaper’s online archives (La Voz de Galicia, Faro de Vigo, El Correo Gallego, and El Correo, Deia, Gara). The interviews, photos and field notes were made during ten visits of one to four weeks length to Galicia and the Basque Country between 2011 and 2016. Though the focus of the analysis is on the T-shirt displays, I also examine the placement of the stores in the cities and their exterior and interior design, as well as the brands’ websites and online stores. Throughout the analysis, all these multimodal ‘texts’ are contextualised, taking into account the similarities and differences between Galicia and the Basque Country in terms of their political economy of language, culture and place.

2. T-shirts as genre for playful metacultural displays

T-shirts are not just clothing, but mobile, multimodal and highly accessible communicative media used for displaying and indexing a wide range of things, people, places and values. As ‘one of the prime emblems or icons of modern life … [the T-shirt] is a sign vehicle whose functions not only express selves, but the social and political fields in which it exists’ (Cullum-Swan & Manning, Citation1994, p. 417). In the 1980s and 1990s, T-shirt prints around the world became increasingly reflexive and self-referential, communicating about other signs and often displaying metacultural and ironic puns (Cullum-Swan & Manning, Citation1994, p. 425). This self-reflective and metacultural character of T-shirts is also central to Coupland’s (Citation2012) analysis of bilingual displays on Welsh T-shirts and Kelly-Holmes’ discussion of Irish T-shirts in Pietikäinen et al. (Citation2016). Other recent sociolinguistic studies of T-shirts have paid attention to processes of dialect enregisterment (Johnstone, Citation2009) and to bodily and gendered aspects of T-shirts (Milani, Citation2014). This paper adds both empirical detail on local identity formation and theoretical discussion on ‘metrolingualism’ (Jaworski, Citation2014; Otsuji & Pennycook, Citation2010) to this emerging sociolinguistic interest in T-shirts as communicative genre and site for semiosis.

My interest here is T-shirts with playful metacultural displays. By this, I mean prints which clearly contain linguistic, graphic or visual markers of local culture and identity and which somehow give these markers a playful twist. The twist is produced by combining the markers of locality with globally touring, accessible and recognisable semiotic resources, such as the English language, logos of transnational companies, or pop cultural icons. In addition to this, the T-shirts analysed in this paper potentially contribute to sociolinguistic change (Coupland, Citation2016). Though perhaps foremost being seen as witty expressions of local culture and identity, the interviewed T-shirt-designers often expressed a self-reflexive cultural critique and aspiration for sociolinguistic change. Thus, creativity is understood more strongly as ‘the use of language to creatively manipulate social situations’ (Jones, Citation2010, p. 469).

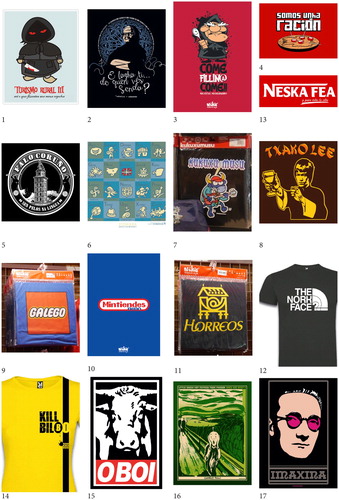

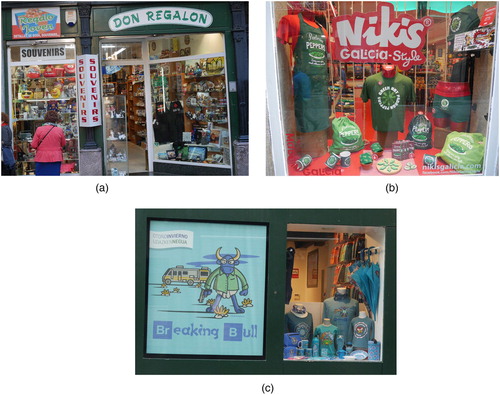

At the same time, all T-shirts are commodities put on sale in a market. The fact that the T-shirts discussed herein have come to constitute a relatively lucrative niche market within the larger tourist driven Galician and Basque souvenir-market shows that they are valued. And, as will be argued throughout the paper, the motive for this lies in their playful and creative performance of local culture, language and identity. Creativity is therefore seen as a social practice and performance that engages in both critical and commercial ways with local culture, as opposed to T-shirts displaying stereotypical elements of Basque and Galician culture and identity only for commercial reasons: e.g. national colours and maps, cultural symbols such as the Basque swastika and the Galician/Celtic triskele, and vernacular typography (Järlehed, Citation2015) deployed for worn out political slogans and cultural expressions (see ). Or, as summarised by T-shirt designer Antón Lezcano in 2004: ‘We were fed up with associating Galician identity to black [T-shirt] designs with Celtic symbols, without creativity’Footnote3 (Rodríguez, Citation2004, p. 46).

3. Metrolingualism, reflexivity, and parody

Emerging at the beginning of the 1990s in the Basque Country and a decade later in Galicia, the analysed T-shirts have thus been made for a combination of playful, ideological, and commercial motives. Like the Welsh Patagonian identity displays described by Coupland and Garrett (Citation2010, p. 21) they are ‘strongly metacultural’, i.e. they ‘actively and reflexively “perform”’ Basque and Galician culture. In their creative use and mixing of different languages, and in their (re)elaboration of social identities and ideologies, they are examples of contemporary ‘metrolingualism’ (Otsuji & Pennycook, Citation2010). However, the T-shirts are not just using linguistic resources, but also images, colour, and typography. This article therefore builds on Jaworski’s (Citation2014) extended and multimodal notion of metrolingualism. It uses metrolingualism as a conceptual tool for analysing and discussing how metacultural displays combine semiotic resources of fixity and fluidity to create and perform Galicianness and Basqueness. That is, the notion of metrolingualism is here developed building on (1) Maher’s (Citation2005, p. 83) description of ‘metroethnicity’ as people’s ‘“play” with ethnicity (not necessarily their own) for aesthetic effect’, (2) Otsuji and Pennycook’s (Citation2010) discussion of ‘fixity’ and ‘fluidity’ as a means ‘both to avoid turning hybridity into a fixed category of pluralisation, and to find ways to acknowledge that fixed categories are also mobilised as an aspect of hybridity’, and finally (3) Jaworski’s (Citation2014) extension of the concept to cover multimodal semiosis.

Whereas, Otsuji and Pennycook’s (Citation2010) notion draws on Maher’s (Citation2005) concept of metroethnicity, according to Jaworski (Citation2014, p. 139) they

distance themselves somewhat from Maher’s dominant view of metroethnicity as ‘playful’ and suggest that metrolingualism involves more ‘serious’ aspects of negotiating identity in the sense of the queering (after Nelson, Citation2009) of linguistic practices; that is, disrupting or destabilizing dominant expectations and ideologies.

The authors of the playful ethnic displays therefore need and show proof of ‘symbolic competence’: they enter the symbolic universe of Galicianness and Basqueness ‘with both full involvement and full detachment’ (Kramsch & Whiteside, Citation2008, p. 668). That is, they are both claiming belonging to the older and fix ethnic community and criticising it, at the same time that they – through their pop-cultural references – engage with a contemporary and fluid community of cool urban youth (Maher, Citation2005, see also de Witte, Citation2014). This symbolic competence can be seen as an instance of ‘the elite reflexivity needed to create and understand metalinguistic humour’ (Jaffee & Oliva, Citation2013, p. 106), i.e. metalinguistic humour and metrolingual play is reserved for a limited group of local producers and consumers of the T-shirts. To a certain degree, this also holds for their foreign consumers since they need some knowledge of local language, culture and politics in order to understand the jokes.

In order to achieve their goals, the T-shirt designers turn to parody as a central strategy. As argued by Hariman, parody is important for ‘sustaining democratic public culture’ (Hariman, Citation2008, p. 247), since it ‘puts social conventions on display for collective reflection’ (Hariman, Citation2008, p. 251). Within the context of small and peripheral languages, parody often targets ‘the normative expectations about small languages’ (Pietikäinen et al., Citation2016, p. 191). These expectations normally involve ‘the conception of language as a bounded code, having fixed associations with particular domains of use and other social functions’ (Pietikäinen et al., Citation2016). However, as discussed by Pietikäinen et al. (Citation2016, p. 192), parody and reflexivity feed into each other mutually, since transgressive humour has got potential for both change and risk: ‘Change depends on uptake – on popular engagement with new metalinguistic and metacultural framings. Parody carries the risk of being perceived as trivial and representationally “thin” on the one hand and as spiteful mockery and insult on the other’ (see de Witte, Citation2014 on similar risks with African Cool). Whatever the verdict of public opinion, parody can be seen as a sign of cultural and ethno-linguistic ‘maturity’ (Pietikäinen et al., Citation2016, p. 192): both in that the Galician and Basque languages ‘are seen to be in a “strong” enough position to be the subjects of humour’, and that ‘the orthodoxies of nationalist movements and ideologies have become objects of reflexive awareness and are now ripe for critique’. Although there are risks of trivialisation and commercialisation, over time parody and other aspects of metrolingual play have ‘potential to transform ideologies of language, not least because transgressive acts tend to promote further metalinguistic and metacultural awareness, contestation and creativity’ (Citation2016, p. 192). Finally, the analysis will show that parody here is also being developed for a local critique of global processes of commodification.

Since this study is limited to the analysis of T-shirts and designer comments, I cannot address the wider social and discursive uptake of the metrolingual play and parody that these T-shirts express. But in the next section I will show that Basque and Galician sociolinguistic change is paralleled by and arguably interacting with shifts in the landscape of humorous performances and displays of Basque and Galician culture and identity.

4. Humour, cultural identity, and sociolinguistic change in Galicia and the Basque Country

There is a clear difference between the writings on Galician and Basque humour and cultural/national identity. Whereas expressions of Basqueness and Basque nationalism generally have been described as having a serious tone (González-Allende, Citation2015; Moreno, Citation2013) and Basque identity normally has been seen as strong both by in-group and out-group members (Järlehed, Citation2008), humour has long been a central component of Galician nationalism (Izaguirre, Citation2000) and Galician identity has typically been described as weak (i.e. not claimed by the majority of the population), negative (i.e. linked to feelings of shame and stigmatisation) or double (i.e. paired with Spanish identity), both by Galicians and others (Romero, Citation2011). For instance, Subiela (Citation2013, p. 103) argues that Galicians suffer from a ‘reflexive delay’, not due to lack of analysis and self-reflection, but because of a gaze determined by ‘negative identity’ and a focus on ‘their incapacities instead of on their potentials’. Along the same lines, Formoso Gosende (Citation2013) suggests a model for overcoming the longstanding stigmatising discourse on the Galician language. She argues that the aesthetical appeal of the language needs renovation; it must adapt to new digital generations and frameworks of urban cool (Formoso Gosende, Citation2013, p. 222). Recent studies on Basque identity and language have also begun nuancing the common external image of Basques as harsh political and linguistic activists, as well as showing signs of internal cultural maturity through the increasing popularity of humorous media productions such as the TV-show Vaya Semanita, ‘making it acceptable to laugh about the complexities and challenges of national and ethnic identity formation’ (Ciriza, Citation2012, p. 181).

The shifts in the perception of Galician and Basque culture and identity resonate in the interviews I conducted with Galician and Basque T-shirt designers. While the Basque designers are more reluctant to accept their own contribution to Basque culture, the Galician designers are clearly proud of their work, which they believe makes an important contribution to Galician Culture.

Of course, Reizentolo is big words, because they have developed really good jokes, a very cool graphic design, quality products, and it is a recognized brand among people who use it throughout Spain. […] When I see their catalog and the drawings that they have, I say, ‘Damn, what a pity that I’m not Galician so that I could wear that shirt’. You could put it on equally, but if I would be Galician I would do it for sure, and this one and this one … Footnote4 (Basque T-shirt designer)

‘Importance’, a lot, I guess. No, I know it [our work] is important, because in the end it is what maintains the culture. […] The difference we see with what others do is that we mix, we play a little with the design and make a mixture based on our traditional sayings […] I did not see it so elaborated anywhere else; not that I know, I did not.Footnote5 (Galician T-shirt designer)

5. Analysis

The analysis is divided into three sections where I first deal with the discursive packaging, i.e. where are the T-shirts sold and how are they framed by declarations of their designers, in the stores and on the brand’s webpages? This is followed by an analysis of the linguistic, visual and graphic resources displayed on the T-shirts. The last section discusses the varied sociolinguistic and cultural conditions for metrolingual play in Galicia and the Basque Country.

5.1. Discursive packaging

Of the analysed T-shirt brands a few are really big with a series of physical and online stores and additional resellers around Spain (Kukuxumusu, Reizentolo, Nikis Galicia Style), while some are smaller and just have one store (Nicetrip, La Bernarda) or sell through others (Aduaneiros sem fronteiras, bbbabyboom). Even though there are internal differences among these brands (see further down), their T-shirts can be distinguished from others sold in Galician and Basque tourist stores and international web shops by the brandnames; the price and content of the T-shirts; and the design of the off- and online stores ().

Table 1. Name, location, period of existence, and URL of the studied T-shirt brands.

Most of the names express a playful stance towards Galician and Basque language and culture. For instance, Aduaneiros sem fronteiras (Customs without borders) and Kukuxumusu (The kiss of the flea), can be read as ironic self-reflections on the legitimacy and value of the brands’ playing around with Galician and Basque culture. Furthermore, most of the names are written in the minority language only (e.g. Caramuxo) or in ‘imperfect’ bilingual or mixed forms combining Basque or Galician with either Spanish or English, as in Nikis Galicia Style which mixes the globalised English word style with a deviant form of the Spanish word for T-shirts, niquis, rendered with the ‘rebel’ or ‘transgressive’ K (Screti, Citation2015). Together, these naming practices suggest a detached and playful embrace of local culture and language, and an implicit critique of linguistic purism, common among the intellectual and political elites of Galicia and the Basque Country, as illustrated by the following quote (see also Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2017, p. 5).

I can speak several languages, and in a conversation with someone who also speaks several languages, I can change from one language to another, and the communication is enriched. Sometimes I need a term in a language that another language does not give me. That is all fine, but to hybridize the language and contaminate it, that does not seem good to me, no. We need to maintain the structure. (High civil servant at the Basque Department of Education, interviewed in San Sebastián in September 2015, cursive by the author)Footnote6

We want to reflect exactly what there is, create phrases as we would say them in the street; not translate into a perfect Galician, but reflect our idiosyncrasy which is no more than that. […] If there are some Galician words on the t-shirts that are not correctly spelled, maybe it’s on purpose because we do as we are, as we would say, and not as it properly ought to be.Footnote7 (Galician T-shirt designer, interviewed in Pontevedra in March 2015)

As the Irish T-shirt brand hairybaby discussed by Pietikäinen et al. (Citation2016, pp. 176–181), the Basque and Galician T-shirts thus ‘provide consumers with symbolic materials to use imperfect [Basque and Galician] as a positive identity resource’. Through their play the various T-shirt firms are

taking part in a powerful transgression of existing norms governing who can legitimately claim to be a speaker of … [Basque and Galician], who can wear a T-shirt with … [Basque and Galician] on it (apart from tourists and fluent speakers) [cf. the Basque designer’s lament above over not being Galician] and who has input into the kind of … [Basque and Galician] that is printed and sold. (Pietikäinen et al. Citation2016)

The studied shirts are relatively expensive at 20–25 Euros whereas traditional Galician and Basque souvenir T-shirts cost 10–15 euros. They are also exclusive in the sense that they are sold in separate branded stores, with a coherent and cool design often playing with objects and tools from rural society, strongly contrasting with the traditional souvenir shop with its chaotic mix of artifacts of all kinds, sizes, and colours produced by a range of different firms (). The stores are furthermore strategically placed in central spots along the tourist trajectory of the old towns and the soundscape of the inside often features cool pop-music. Altogether, this packaging of the T-shirts clearly positions them as ‘luxury goods’ (Appadurai, Citation1986) reserved for privileged consumers.

Figure 2. Traditional souvenir store in Bilbao (top left) and branded souvenir stores in Santiago de Compostela (top right) and Pamplona (bottom). Photos by the author.

At the same time, the central feature of the displays being playful elaborations of local culture and language, the T-shirts presuppose a ‘kind of intimacy of the buyer and the linguistic context without which it would be hard to imagine the consumer value or appeal of the product’ (Jaffee & Oliva, Citation2013, p. 13). According to my informants, the consumers of these T-shirts include both international and local tourists, and local inhabitants, and one of the most important groups is made up by Galician and Basque expatriates (see also González, Citation2007). While the latter arguably purchase these T-shirts for reasons of pride and belonging, and in order to display their local culture away from ‘home’, the motives are somewhat different for international tourists. As argued by Jaffee and Oliva (Citation2013, p. 13), the purchase of these T-shirts possibly serves ‘to authenticate the “elite” tourist through the appropriation of “local language” in ways that position those tourists as “cosmopolitan internationals” who engage with local cultures and languages in superficial ways’.

Beyond the shared metrolingual character of their T-shirts the commercial potential and linguistic-cultural positioning vary among the analysed companies. While the smaller Galician ones (Aduaneiros, Caramuxo, Nicetrip) expressed a clear loyalty with Galician culture and language, and used humour as a tool to promote it, the two small Basque brands (La Bernarda and bbbabyboom) are run by Spanish-speaking Basques who stress the importance of humour and irony for their work, but rather develop personal than cultural motives for their use of Basque culture and language in their play; they use it, as it were, since it happens to be part of their everyday environment. Both websites are also monolingual in Spanish.

Among the bigger brands, the linguistic and cultural positioning of Nikis stands out with a website deploying Galician as default language and Spanish as optional, paired with a slogan in Galician that stresses the Galicianness and humour of their T-shirts: ‘Camisetas orixinais. Divertidas. Galegas. Humour do bo 100% galego’ (Original T-shirts. Funny. Galician. Humour 100% in Galician). By contrast, the other big and competing Galician firm, Reizentolo uses Spanish as default language and Galician as optional on their website. This is consistent with their stress of the commercial success and spread of their products, with them being sold in ‘hundreds of multi-brand stores all over Spain’.

5.2. Displays of fixity and fluidity

As explained above, the visual displays of the analysed T-shirts combine globally circulating, accessible and recognisable resources with resources that are socially defined as local, i.e. localised in the sense that they have become part of local cultural identity. Within the discussion of metrolingualism, this has been described as a dynamic of ‘fluidity’ and ‘fixity’: as two phenomena that are ‘symbiotically (re)constituting each other’ (Otsuji & Pennycook, Citation2010, p. 244):

What often seems to be overlooked in discussions of local, global and hybrid relations is the way in which the local may involve not only the take up of the global, or a localised form of cosmopolitanism, but also may equally be about the take up of local forms of static and monolithic identity and culture. (Otsuji & Pennycook, Citation2010, pp. 243–244)

As illustrated in , the semiotic resources of fixity and locality include elaborated and multilayered images of the cultural heritage, such as rural architecture (e.g. the Galician horreo [11]); historical buildings (e.g. the Hercules lighthouse in A Coruña [5]); popular festivals (e.g. the bull run in Pamplona [7] and the ox festival in Allariz [14]); folklore and religious/popular rites (e.g. Basque folk dance and rural sports [6], and the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela); autochthonous or iconic animals (e.g. the Galician cow, the Basque sheep, and the Pamplonese bull [7]); and foodstuff (e.g. the Galician seafood pulpo [4] and the Basque white wine txakoli [8]).Footnote8 Language is used as marker in several ways: as codes indexing the Basque and Galician nations; in orthographic and typographic choices indexing geographic and ideological positions (e.g. the Galician dialectal feature gheada [2] and vernacular letterforms [17]); in Galician and Basque place names (e.g. Monte Alto, Pagasarri); and finally also in typical local sayings, especially in Galicia where the so called retranca is central to these T-shirts [2]. Last but not least, the resources of fixity include visual and linguistic references to iconic persons and personae of local history and culture such as Rosalía de Castro, Alfonso Daniel Rodríguez Castelao [17], and the rural grandmother in Galicia [1–3], and Arturo Campión and Xalbador in the Basque Country.

Most of these resources of fixity are closely tied to territory and to rural life. In both Galicia and the Basque Country, the urban-rural divide has been present in public discourse and definitions of identity since industrialisation and urbanisation began in the mid-nineteenth century. In both cases, the minority language has also been associated with the countryside and rural life, and contemporary imaginations of Galicia still include rurality as central feature (Romero, Citation2011). However, rurality is an idealised construct, and ‘a medium for obtaining “a sense of place” or “symbolic capital”’ (Lacour & Puissant, Citation2007, p. 735). In particular the Galician T-shirt brands strategically deploy rurality to target an audience who is living in the city but maintains strong emotional and social ties to the village and the rural lifestyle of their grandparents. The Galician T-shirt brands appropriate and transform traditional values of rurality into a nostalgic but positive and humorous identity resource. This strategy reflects the emergence of what Colmeiro (Citation2009) has described as a new ‘rurban’ social reality promoted since the 1990s by the Galician bravú movement. As in Japanese metroethnicity, in this subcultural movement, ‘cultural hybridity is a constant presence [… .], affirming Galicianness while rejecting essentialist notions of identity’ (Colmeiro, Citation2009, p. 228).

The Galician T-shirts also depict older people, both in person, and indirectly by quoting the retranca that is generally understood as belonging to the older generations. However, in line with the general strategy of playful ambiguity, the representation of the older generation expresses both affection and distance. What we find in the shirts is very much cultural stereotypes: old gruff women all dressed in black caring about the (grand)children’s (too poor) diet (pictures 1–3 in ) and old men standing out in the fields leaning on a hoe. The older generation is not only visually situated in rural environments but also verbally and visually depicted as guardians of a threatened life-style. Peripheral rural geographies and lifestyles are indexed by metalinguistic markers such as the Galician dialectal features of the coastal region gheada [1] and seseo, frequently used within the bravú movement ‘for political effect as distinctive markers of origin and class identity’ (Colmeiro, Citation2009, p. 229). While the former is the

pronunciation of the voiced velar occlusive phoneme as a voiceless guttural, as in the word gato [hato] for ‘cat’ … seseo [is a] voiceless alveolar fricative pronunciation as in the word for ‘five’ [sinko], which is the opposite of the use of the voiceless interdental fricative /θ/ pronunciation in standard Galician. (Roseman, Citation1995, p. 13)

Finally, the displayed resources of fixity comprise the kind of things typically consumed by tourists with mouth (foodstuff), eyes (cultural heritage), and ears (local language and music). Hence analytically, one can argue that this local and fix dimension of the playful displays articulates a traditional nationalist discourse of ‘pride’ over authentic features of local culture, but a ‘profit’-oriented one (Duchêne & Heller, Citation2012) adapted to an understanding of the ‘tourist gaze’ as principally interested in consuming already well-known and typical expressions and products of this local culture. However, as noted by one of my reviewers, this is not new; both the Galician and Basque T-shirts can be seen as a contemporary way to embody the local experience of doing the Camino de Santiago – which has been an experience of commodification for centuries – and running in front of the bulls in Pamplona – strongly commodified since Hemingway’s writings made the San Fermines popular to international tourism.

Turning over to the second analytical component of the T-shirt-prints, what are the globally touring semiotic resources that are adapted to create the metrolingual play? Basically, the T-shirts deploy small bits of English language, pop-cultural icons taken from the three fields of art, film, and music, and logos of transnational companies (see ). Examples of the latter include Caramuxo’s congenial adaptation of the logo of the Danish toy factory Lego, with the name transformed into ‘Galego’ which is the Galician word for both a Galician person and the Galician language (in [9] reused by Nikis Galicia Style). Another of Nikis’ T-shirts [10] adapts the Nintendo logo to display the cool register of A Coruña’s urban youth, Koruño Footnote9: Mintiendes neno (Do you understand me, man?).

Examples of T-shirts drawing on pop music include Reizentolo’s Imaxina [17] where the founder of Galician nationalism Castelao is portrayed as –and compared to – pop icon John Lennon. The title of his song Imagine is translated into Galician and set with a digital type based on Castelao’s emblematic vernacular lettering, a letra Castelao (see Järlehed, Citation2015). The Reizentolo T-shirt Little Green Hot Peppers from Padrón [16] draws on globalised resources from pop music, modern art, and the English language. The name of the American funk rock band Red Hot Chili Peppers and the iconic Munch painting Skrik (The Scream) are adapted for a playful and proud display of local foodstuff, the Padrón peppers, or pementos de Padrón. As reflected in the popular Galician saying uns pican e outros non, these tasty peppers are generally mild but some exemplars are very hot, thus the visual anguish of The Scream and the Galician legend on the bottom of the print: Carallo, picou!, Shit, it stung!

Not surprisingly given its air of urban Cool and counter-culture, street art has also inspired several metrolingual T-shirt designs. For instance, Shephard Fairy’s iconic and worldwide circulating Obey Giant face is adapted both in La Bernarda’s Jaia (Basque for feast, carnival) and Nikis’ O’Boi [15]. The linguistic and graphic transformation of Obey into O’Boi, combined with the substitution of the Giant face for an ox, creates a rather complex display. The ox occupies a central role in rural Galician culture, as reflected in the yearly celebration in Allariz, near Ourense, of Festa do Boi, The Ox Feast. The pun of this T-shirt draws on the English expression ‘Oh, boy’, here shortened with the apostrophe. The O is also the definite masculine article in Galician, which opens for another reading: the ox. At still another level, finally, this way of writing the article with an apostrophe can be seen in the Galician linguistic landscape (e.g. the bar O’Largo in A Coruña which displays a curious hybrid of Galician and Spanish; the Galician article O being combined with the Spanish word for long, largo, instead of the correct Galician form longo). According to some of my informants, in the 1970s and 1980s many Galician bars and restaurants adapted this apostrophe as an expression of sympathy with Irish culture.Footnote10 Similarly, in his book Unha espia na reino de Galicia Manuel Rivas frequently draws on typical Irish names such as O’Hara and O’Brien for colloquially naming Galician personalities with the Galician structure ‘definite article + personal name’ (e.g. O’Fetén).

The five commented categories of globalised resources of fluidity, i.e. English, art, music, film and logos, are all central instances or products of the so called cultural or creative industries, that is, ‘an economic and cultural force that [supposedly] can do the work of revitalizing and transforming place and space through arts and culture’ (Banet-Weiser, Citation2011, p. 642). Indeed, creativity has during the last couple of decades emerged as a buzzword in many spheres of life and, as suggested by my inclusion of the word ‘supposedly’ in the quote, there is ground for discussing to what extent it has become a standardised commodity (much like ‘authenticity’ within tourist and linguistic revitalisation discourses), perhaps in particular within city- and place-branding (see e.g. Cronin, Citation2008; Evans, Citation2003).

Mostly, and as illustrated by the comments of some of them above, it seems that the pop-cultural icons and logos that are adapted for the Basque and Galician metrolingual displays are treated as positive resources, i.e. as something that creates additional value to the T-shirt and its wearer: both economic value – due to the direct and indirect commodity value of these icons, and cultural value – due to their ideological connotations. As already said, they are also used for creating the puns and for putting the local languages and cultures on display for reflection. In most of these cases, the globalised resources of fluidity are thus used for up-scaling the socioeconomic and cultural value of local languages and cultures.

However, there are also examples of critical and parodic uses of the resources of fluidity. The T-shirt that has given name to this paper, bbbabyboom’s Kill Bilbo [14], suggests a rather innovative and multilayered critique of global processes of commercialisation, privatisation and objectification of our cities and their inhabitants, driven by city-branding discourses and urban regeneration projects. Several semiotic resources are here borrowed from Tarantino’s film Kill Bill: the name, the typeface, the black and yellow colours, and the visual-graphic traces of spectacular violence. These are mixed with localising resources indexing the Basque city of Bilbo-Bilbao: the name, the emblematic pavement tile, and the logo of the new municipal regime: a white B on a red oval. What appears to be a reduction to the monolingual Basque form of the city-name can however be seen as a dense multilingual name. Bilbo is also the name of J.R.R. Tolkien’s hobbit and hence creates an intertextual link to his well-known fantastic world. So, how shall we read this T-shirt? As an imperative command to shoot and kill ‘Bilbo’, who or whatever that might be (the hobbit, the Basque city)? Or as a playful critic of the neoliberal branding and exploitation of the local resources, histories, and people of Bilbo-Bilbao, graphically iconized in the new city logo?

5.3. Sociolinguistic affordances and constraints on creativity

The different sociolinguistic configuration of Galicia and the Basque Country, with more extended social bilingualism in Galicia than in the Basque Country and linguistic similarity between Galician and Spanish as contrasted with strong linguistic difference between Basque and Spanish, creates a situation where (1) Galician is more accessible and viable for public displays than Basque, and (2) the range of (cross-)linguistic creativity possible is more reduced in the Basque Country than in Galicia.

The first point is reflected in that the usage of Basque in the Basque T-shirts, with the exception of some of the early Kukuxumusu shirts, generally is limited to single words, mostly as part of code-mixed Basque-Spanish or Basque-English expressions (e.g. Neska Fea, The Nork Face), but sometimes also in lone standing expressions (e.g. txotx, Jaia). By contrast, the Galician shirts often display multi-word instances of Galician. Among the Galician brands, Caramuxo stood out with a consistent use of text-based and monolingual Galician designs. Among the present day brands, both Nikis and Reizentolo include several designs which reproduce popular Galician sayings and proverbs (e.g. Marcho que teño que marchar, E logho ti … de quen ves sendo?). Over time there is however a general tendency in both Basque and Galician T-shirts towards less text and less mono-modal textual play, and increased use of English: this can best be seen in the Kukuxumusu shirts from the 1990s compared to the ones from 2000 and onwards, and in the Caramuxo shirts as opposed to the ones by Reizentolo and Nikis Galicia Style.

The linguistic creativity produced in the Basque shirts is almost always bilingual including Basque and Spanish. La Bernarda’s Neska Fea [13] for example creates a multimodal and sexist play with the Basque word for girl, neska, and the Spanish word for ugly, fea, layered with the Nescafé logo. There are also examples of linguistic play with Basque and English such as bbbabyboom’s The Nork Face [12]. As the name of one of the Basque cases, Nork has come to symbolise the difficulty to learn Basque. The word is here substituting the original English word North and combined with a transformation of the black inner curved element of the North Face logo into a question mark. The meaning of the metrolingual pun then sums up to ‘the (stupid) face you make when trying to master Basque grammar’.

At another level, some of the Galician T-shirts play with the local uptake of the English language. As told by one designer,

our design ‘LITTLE GREEN HOT PEPPERS’, was born at a time when the menus of restaurants were beginning to be translated into English, by tourists, and it was very funny for us to read terms like ‘lacón’ or ‘polbo á feira’ translated into English.Footnote11

The sociolinguistic profile of each area is furthermore having direct influence on the creative strategies developed by the different designers. Bilbao, for instance, is a city characterised by a majority of Spanish-only speakers, and a minority of bilingual speakers of Basque and Spanish, divided into a larger group of so called new speakers, i.e. people who have learnt standardised Basque in school (Ortega et al., Citation2015) and a very small group who acquired vernacular Basque at home. As illustrated by the following quote, this sociolinguistic configuration leaves room for Basque metacultural displays created so to say from Spanish, or from a Spanish-mostly perspective, thus similar to Rampton’s (Citation1995) ‘cultural crossing’ and some of the instances of metroethnicity commented by Maher (Citation2005) where youngsters play with the ethnicity of ‘others’ for aesthetic effects, while not necessarily having a personal claim to it.

I think one of the reasons that makes my head create certain jokes, is the fact precisely that I do not speak Basque […] if the Basque language would be my mother tongue and I would use it all day, perhaps I would not see the point of the pun […]. I do not know how to tell you: if you use a phrase continually, you do not realize that it resembles another. But instead, if you speak in Castilian, even if you have some idea of Euskera, somehow there are times you say, “Hey, this sounds like this other.” So I think this is how I invent the jokes or motives for the t-shirts, precisely because of not using Basque as my primary language.Footnote12

The largest and most important difference now between us and the competition we have […] with [company X] is that we, practically 100% are in Galician. We … do it in Galician only; unless when a joke has to carry something in Castilian. 99.9% is in Galician. [Company X] already has 80% in Castilian and 20% in Galician, because it has to open up to the Spanish market to sell.Footnote13 (Galician designer interviewed in March 2015)

6. Conclusion

This paper examined metrolingual play in Galician and Basque T-shirts, that is, creative visual and graphic re-elaborations of local language, culture and identity, mixed up with globalised resources of fluidity from, mainly, Anglo-Saxon pop-culture, media and commerce. The analysis showed that they are sold to both tourists and locals, in particular expatriates. While the former purchase them for authenticating their travel experience, to the latter the T-shirts serve as a means to cultivate and perform their cultural belonging. As an ethno-linguistic repertoire, the included resources of fixity index central values of rurality and tradition, and display ‘things’ to be consumed with mouth, eyes and ears. By contrast, the globalised resources of fluidity index a coolness clearly rooted in modern western and Anglo-Saxon pop-culture. Together, the displays therefore suggest a hedonistic and nostalgic appropriation of past rurality by contemporary young urban dwellers, paired with an authentication of tourists’ experiences of ‘local culture’. While the prefix –metro refers to notions of urban life, a central component of the identity work done in the Galician and Basque T-shirts is about constructing a new ‘rurban’ reality (Colmeiro, Citation2009), a mixture of globally circulating notions of urban cool and a local preoccupation with rural traditions and lifestyles.

Since the creativity and play involved in these T-shirts require (some) knowledge of and (critical) reflection on local language, culture and history, they might encourage a move towards more reflexive and mature attitudes towards small and peripheral languages and cultures. As the Welsh and Irish T-shirt designers commented by Coupland (Citation2012) and Pietikäinen et al. (Citation2016, pp. 176–181), the examined Galician and Basque designers challenge standard language ideologies by their usage of rural dialect (gheada) and urban youth registers (koruño), by daring to use ‘imperfect’ and mixed forms of Galician and Basque, and perhaps finally by daring to play with the minority language Basque from a majority position (La Bernarda, bbbabyboom). The latter point is however problematic due to ‘the imbalance in status and power between the languages’ (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2017, p. 7). The analysis correspondingly showed how the bigger brands Kukuxumusu and Reizentolo have developed towards less hybridisation and increased adaptation to standard language ideologies, arguably because of commercial expansion all over Spain and to neighbouring countries. This reduces their critical and transgressive potential and possibly also their air of rurban Cool.

Creativity can thus be described as a complex phenomenon depending on a range of communicative, socio-cultural, and economic competences. Obviously, the designer of the kind of playful metacultural displays that we are discussing needs multilingual competence or at least a developed semiotic awareness and a wide repertoire of cultural resources and references in order to create products witty and cool enough to please the critical audience (cf. Coupland & Garrett, Citation2010). Willingness to play with and challenge local sociolinguistic and cultural norms seems central, at the same time that the genre conventions of metrolingual T-shirts make this play and challenge the expected, and hence less transgressive then if it would be performed in formal genres of public displays such as street names (cf. Järlehed, Citation2017) or municipal logos. In addition, to this, as testified by both informants and the varied success of the different T-shirt brands, entrepreneurships, sales skills and business organisation are all needed to translate ideas and cashing them over time.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council (VR) under Grant 421-2013-1305. I thank Per Holmberg, Francis Hult, Adam Jaworski, Andreas Nord and Crispin Thurlow for their comments on earlier drafts of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Johan Järlehed http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0117-9458

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The photos are all taken either inside the stores with the owner’s permission, or from the street where shirts hang on the storefronts and in the windows. These photos were completed with high-resolution images kindly submitted to me from the different companies. All the images are here reproduced with permission of the authors.

2. The first two were made in A Coruña in April 2011 and in Pontevedra in March 2015, the latter two in Pamplona and Bilbao in September 2015.

3. ‘Estabamos fartos de asociar a identidade galega a deseños negros con imaxes celtas, sen creatividade.’

4. ‘Claro, Reizentolo son palabras mayores, porque tienen un desarrollo de chistes buenísimos, una gráfica muy chula, unos productos de calidad, y es una marca reconocida para la gente que lo usa por toda España. […] cuando veo su catálogo y veo los dibujos que tienen, digo: “Joder, qué faena que no sea gallego para poder ponerme esa camiseta”, te la puedes poner igualmente, pero si fuese gallego me la ponía fijo, y ésta y ésta … ’ All the translations from Spanish and Galician into English are made by the author (quoted interviews and papers).

5. ‘Importancia, pues mucha, supongo. Supongo no, tiene mucha, porque es la que mantiene la cultura al final. […] La diferencia que vemos con lo que nosotros hacemos es que nosotros mezclamos, jugamos un poco con el diseño y hacemos una mezcla en base a nuestras frases […] Yo eso, tan trabajado no lo vi; que yo conozca, no lo vi.’

6. ‘Yo tengo capacidad para hablar varias lenguas, y en una conversación con alguien que habla también varias lenguas, puedo ir cambiando de una lengua a otra, y la comunicación se enriquece. A veces necesito un término en una lengua que otra lengua no me lo da. Eso sí, pero ya hibridar la lengua y contaminarla, a mí eso no me parece, no. Tenemos que tener cuidado de mantener la estructura.’

7. ‘Queremos reflejar exactamente lo que hay, poner frases como las diríamos en la calle; no traducirlas a un gallego perfecto, sino reflejar nuestra idiosincrasia que no es más que esa. Si estamos influenciados por el castellano, nosotros no vamos a poner en las camisetas nada diferente a lo que nosotros somos. Si hay algunas palabras que no están correctamente puestas en gallego en las camisetas, a lo mejor es a propósito, porque la hacemos como nosotros somos, como nosotros lo diríamos, no como correctamente tendía que ser. Queremos reflejar lo que hay, nada más.’

8. See Järlehed and Moriarty (Citation2018) for an introduction of the notion of semiofoodscape to linguistic landscape studies and a detailed analysis of the socioeconomic and linguistic upscaling of Txakoli.

9. See more (playful) information on koruño: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ToDYQLdf40o; https://xentedacova.wordpress.com/2007/05/29/real-akademia-del-koruno/; http://inciclopedia.wikia.com/wiki/Koru%C3%B1o

10. The English/Irish apostrophe was also frequently deployed in naming practices in the linguistic landscape of Madrid in the 1990’s (Muñoz Carobles, Citation2010, p. 107), suggesting a parallel or more general orthographic borrowing based on the prestige associated with the English language.

11. ‘Nuestro diseño “LITTLE GREEN HOT PEPPERS”, nació en un momento en que las cartas de los restaurantes comenzaban a traducirse al inglés, por los turistas, y era muy gracioso para nosotros el leer términos como “lacón” o “polbo á feira” traducidos a inglés’.

12. ‘Creo que uno de los motivos que hace que de mi cabeza puedan salir ciertos chistes, es el hecho precisamente de que no hablo euskera, que sí que conozca lo que quiere decir, pero que si el euskera fuese mi lengua materna y la usase todos los días, igual no vería ese chiste como efectivo, porque igual ese juego de palabras no lo tendría. No sé cómo decirte: si es una frase que utilizas de continuo, no te das cuenta que se parece a otra. Pero, en cambio, si hablas en castellano, aunque tengas nociones de euskera, de alguna forma hay veces que dices: “Oye, esto suena parecido a esto otro”. Entonces yo creo que por ahí es como me salen un poco los chistes o los motivos para las camisetas, por el hecho precisamente de no utilizar el euskera como lengua principal.’ (T-shirt designer in Bilbao).

13. ‘La diferencia básica más grande que hay ahora entre nosotros y la competencia que tenemos, que me hablabas antes de [la empresa X], es que nosotros prácticamente el 100% es en gallego. Nosotros … lo hacemos sólo gallego; salvo que por una coña, o por una broma tenga que llevar algo en castellano. El 99,9% es en gallego. [La empresa X] ya tiene el 80% en castellano y 20% en gallego, porque tiene que abrirse al mercado español para poder vender.’

References

- Appadurai, A. (1986). Introduction: commodities and the politics of value. In A. Appadurai (Ed.), The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (pp. 3–63). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Banet-Weiser, S. (2011). Convergence on the street. Cultural Studies, 25(4–5), 641–658. doi: 10.1080/09502386.2011.600553

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2017). Minority languages and sustainable translanguaging: Threat or opportunity? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 38(10), 901–912. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2017.1284855

- Ciriza, M. d. P. (2012). Basque natives vs. Basque learners: The construction of the Basque speaker through satire. Discourse, Context & Media, 1(4), 173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2012.06.002

- Colmeiro, J. (2009). Smells like wild spirit: Galician rock Bravú, between the ‘rurban’ and the ‘glocal’. Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, 10(2), 225–240. doi: 10.1080/14636200902990729

- Coupland, N. (2012). Bilingualism on display: The framing of Welsh and English in Welsh public spaces. Language in Society, 41(1), 1–27. doi: 10.1017/S0047404511000893

- Coupland, N. (2016). Five Ms for sociolinguistic change. In N. Coupland (Ed.), Sociolinguistics: Theoretical debates (pp. 433–454). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Coupland, N., & Garrett, P. (2010). Linguistic landscapes, discursive frames and metacultural performance: The case of Welsh Patagonia. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 205, 7–36.

- Cronin, A. M. (2008). Urban space and entrepreneurial property relations: Resistance and the vernacular of outdoor advertising and graffiti. In A. M. Cronin, & K. Hetherington (Eds.), Consuming the entrepreneurial city: Image, memory, spectacle (pp. 65–84). Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Cullum-Swan, B., & Manning, P. K. (1994). What is a t-shirt? Codes, chronotypes, and everyday objects. In S. H. Riggins (Ed.), The socialness of things: Essays on the socio-semiotics of objects (pp. 415–434). Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Del Valle, J. (2000). Monoglossic policies for a heteroglossic culture: Misinterpreted multilingualism in modern Galicia. Language & Communication, 20, 105–132. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5309(99)00021-X

- de Witte, M. (2014). Heritage, Blackness and Afro-Cool: Styling Africanness in Amsterdam. African Diaspora, 7(2), 260–289. doi: 10.1163/18725465-00702002

- Duchêne, A., & Heller, M. (Eds.). (2012). Language in late capitalism: Pride and profit. New York: Routledge.

- Evans, G. (2003). Hard-Branding the cultural city-from Prado to Prada. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 27(2), 417–440. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.00455

- Formoso Gosende, V. (2013). Do estigma á estima. Propostas para un novo discurso lingüístico. Vigo: Xerais.

- Gara. (2006, December 18). «Cuanto más inteligente es una persona, más sutiliza su humor» [Interview with Rafael Castellano]. Gara. San Sebastián. Retrieved from http://gara.naiz.eus/idatzia/20061218/art193813.php

- González, S. (2007, November 13). «Imos poñer unha lonxa na páxina web para subastar á baixa unha camiseta diaria». La Voz de Galicia. Vigo. Retrieved from http://www.lavozdegalicia.es/noticia/arousa/2007/11/13/imos-poner-unha-lonxa-na-paxina-web-subastar-a-baixa-unha-camiseta-diaria/0003_6313034.htm

- González-Allende, I. (2015). The Basque big boy? Basque masculinities in Vaya semanita. Journal of Iberian and Latin American Studies, 21(1), 19–37. doi: 10.1080/14701847.2015.1078984

- Hariman, R. (2008). Political parody and public culture. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 94(3), 247–272. doi: 10.1080/00335630802210369

- Izaguirre, K. (2000). El humor de Castelao: visto por un escritor vasco. Revista de Lenguas Y Literaturas Catalana, Gallega Y Vasca, 7, 361–378.

- Jaffee, A., & Oliva, C. (2013). Linguistic creativity in corsican tourist context. In S. Pietikäinen, & H. Kelly-Holmes (Eds.), Multilingualism and the periphery (pp. 95–117). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Järlehed, J. (2008). Euskaraz. Lengua e identidad en los textos multimodales de promoción del euskara, 1970-2001. Gothenburg: Gothenburg University Press.

- Järlehed, J. (2015). Ideological framing of vernacular type choices in the Galician and Basque semiotic landscape. Social Semiotics, 25(2), 165–199. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2015.1010316

- Järlehed, J. (2017). Genre and metacultural displays: The case of street-name signs. Linguistic Landscape: An International Journal, 3(3), 286–305. doi: 10.1075/ll.17020.jar

- Järlehed, J., & Moriarty, M. (2018). Culture and class in a glass: Scaling the semiofoodscape. Language & Communication, 62(September 2018), 26–38. doi:10.1016/j.langcom.2018.05.003

- Jaworski, A. (2014). Metrolingual art: Multilingualism and heteroglossia. International Journal of Bilingualism, 18(2), 134–158. doi: 10.1177/1367006912458391

- Jaworski, A., & Thurlow, C. (Eds.). (2010). Semiotic landscapes: Language, image, space. London: Continuum.

- Johnstone, B. (2009). Pittsburghese shirts: Commodification and the enregisterment of an urban dialect. American Speech, 84(2), 157–175. doi: 10.1215/00031283-2009-013

- Jones, R. H. (2010). Creativity and discourse. World Englishes, 29(4), 467–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-971X.2010.01675.x

- Kelly-Holmes, H. (2014). Commentary: Mediatized spaces for minoritized lanuages. Challenges and opportunities. In J. Androutsopoulos (Ed.), Mediatization and sociolinguistic change (pp. 539–543). Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter.

- Kramsch, C., & Whiteside, A. (2008). Language ecology in multilingual settings. Towards a theory of symbolic competence. Applied Linguistics, 29(4), 645–671. doi: 10.1093/applin/amn022

- Lacour, C., & Puissant, S. (2007). Re-urbanity: Urbanising the rural and ruralising the urban. Environment and Planning A, 39(3), 728–747. doi: 10.1068/a37366

- Lamas, J. (2004, September 4). A retranca viaxa pola rede. La voz de Galicia. Vigo. Retrieved from http://www.lavozdegalicia.es/hemeroteca/2004/09/04/2994705.shtml

- Machin, D. (2016). The need for a social and affordance-driven multimodal critical discourse studies. Discourse & Society, 27(3), 322–334. doi: 10.1177/0957926516630903

- Maher, J. C. (2005). Metroethnicity, language, and the principle of Cool. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 175–176, 83–102.

- Martínez-Quiroga, P. (2014). “Unha espía no Reino de Galicia” de Manuel Rivas: O humor e a construción da identidade nacional galega. Revista de Filología Románica, 31(2), 209–226.

- Milani, T. M. (2014). Sexed signs: Queering the scenery. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 228, 201–225.

- Moreno, C. (2013). Can ethnic humour appreciation be influenced by political reasons? A comparative study of the Basque Country and Calalonia. The European Journal of Humour Research, 1(2), 24–42. doi: 10.7592/EJHR2013.1.2.moreno

- Muñoz Carobles, D. (2010). Breve itinerario por el paisaje lingüístico de Madrid. Ángulo Recto. Revista de estudios sobre la ciudad como espacio plural, 2(2), 103–109.

- Nelson, C. D. (2009). Sexual identities in English language education: Classroom conversations. New York: Routledge.

- O’Rourke, B., & Ramallo, F. (2013). Competing ideologies of linguistic authority amongst new speakers in contemporary Galicia. Language in Society, 42(3), 287–305. doi: 10.1017/S0047404513000249

- Ortega, A., Urla, J., Amorrortu, E., Goirigolzarri, J., & Uranga, B. (2015). Linguistic identity among new speakers of Basque. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 231, 85–105.

- Otsuji, E., & Pennycook, A. (2010). Metrolingualism: Fixity, fluidity and language in flux. International Journal of Multilingualism, 7(3), 240–254. doi: 10.1080/14790710903414331

- Pietikäinen, S., Jaffe, A., Kelly-Holmes, H., & Coupland, N. (2016). Sociolinguistics from the periphery: Small languages in new circumstances. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ramallo, F. (2014). Language policy and conflict management: A view from Galicia. In N. Alexander, & A. V. Scheliha (Eds.), Language policy and the promotion of peace. African and European case studies (pp. 93–103). Braamfontein: University of South Africa.

- Rampton, B. (1995). Crossing. Language and ethnicity among adolescents. London: Longman.

- Rivas, M. (2004). Unha espia no reino de Galicia. Vigo: Xerais.

- Rodríguez, A. (2004, July 18). Deseños con retranca. A arte gráfica inaugura una nova xeración de camisetas ‘made in Galicia’. La Opinión, A Coruña. P. 46.

- Romero, E. R. (2011). Contemporary Galician culture in a global context: Movable identities. Lanham, MD.: Lexington Books.

- Roseman, S. R. (1995). “Falamos como falamos”: linguistic revitalization and the maintenance of local vernaculars in Galicia. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 5(1), 3–32. doi: 10.1525/jlin.1995.5.1.3

- Screti, F. (2015). The ideological appropriation of the letter K in the Spanish linguistic landscape. Social Semiotics, 25(2), 200–208. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2015.1010321

- Subiela, X. (2013). Para Que Nos Serve Galiza? Construír un país entre todas e todos. Vigo: Galaxia.