ABSTRACT

The starting point for this research is an eTandem initiative between learners of Mandarin Chinese and German. The participants mainly learnt the dominant variety of their target languages (German Standard German, Mainland Chinese Standard Mandarin), however, their tandem partners are speakers of a non-dominant variety (Austrian Standard German, Taiwanese Standard Mandarin). Due to this pairing, some speakers felt prompted to position themselves in relation to the discussed varieties. The empirical study analyses the discursive construction of language variation of one eTandem dyad that elaborated on this topic at length. For this purpose, we adopted a critical discourse analysis approach and focused on three aspects (nomination, predication, perspectivisation). The results reveal that language variation in the Chinese context, especially the concept of Fāngyán, was difficult to grasp and explain, while the discussion on German was more clear-cut. Standard language was conceptualised as a tool for inclusion, whereas non-standard varieties were conceived as excluding but also as a means to create community belonging. Based on our results we conclude that diversity in varieties in tandem learning has the potential to offer valuable opportunities not only to learn about target language variation, but also to increase language awareness regarding one’s expert language.

1. Introduction

Most foreign languages are learnt in a formal, institutional setting (European Commission, Citation2012) and are taught in their dominant standard variety (Auswärtiges Amt, Citation2020, pp. 11–18; Kaltenegger, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; see Section 2.1). However, the following article focuses on conversations that take place in a non-formal language learning scenario called eTandem. eTandem is the digital, web-based equivalent of the better-known tandem learning (Brammerts, Citation2006; Cziko, Citation2004) which ‘involves two individuals learning each other’s languages while mutually supporting each other’ (El-Hariri, Citation2016, p. 49). Both individuals alternate between the roles of learner and expert speaker (Appel, Citation1999, p. 5).

The current eTandem project involved Mandarin and German as target languages. In foreign language education, both languages are usually taught in their dominant standard varieties (Mainland Chinese Standard Mandarin and German Standard German). In our case, the Mandarin learner and German expert is from Austria, the German learner and Mandarin expert from Taiwan. This means that both tandem partners are speakers of a non-dominant standard variety (Taiwanese Standard Mandarin and Austrian Standard German) and therefore each expert speaks a different standard variety than the one the learners had been exposed to. These circumstances led to a thorough discussion of standard varieties, the relationship between standard and dialect as well as the Chinese notion of Fāngyán within the eTandem conversations, which provides us with insights into how speakers of non-dominant varieties and learners of dominant varieties perceive ChineseFootnote1 and German variation.

2. Language variation in Chinese and German

2.1. Theoretical background

Two major pillars in the discussion on language variation are the notions non-standard and standard (for a detailed discussion of this conceptual pair, see Van Rooy, Citation2020). One cannot exist without the other as ‘dialects cannot be labeled ‘non-standard’ unless a standard variety is first recognized as definitive and central’ (Milroy, Citation2001, p. 534). In contrast to non-standard varieties for which variation is perceived as natural, standard varieties require the ‘suppression of optional variability in language’ (Milroy & Milroy, Citation1985, p. 8) to become a tool for communication ‘with the minimum of misunderstanding and the maximum of efficiency’ (Milroy & Milroy, Citation1985, p. 23).

This leads to the fallacy that there can only be one standard variety per language. Yet, variation does not necessarily create new, independent languages, instead language variation may also cause the emergence of multiple standard varieties within a language (Kloss, Citation1967, pp. 66–67). Languages with several standard varieties are called pluricentric languages (Kloss, Citation1967, Citation1978; Stewart, Citation1968), as their varieties commonly develop because of their usage in different self-governing entities, e.g. nation states (Dollinger, Citation2019, pp. 7–8). These self-governing entities act as centres for their respective varieties by exerting influence on them through language policy, this way ‘grammatical, lexical, phonological, graphemic, prosodic, and pragmatic’ (Clyne, Citation2004, p. 297) differences between standard varieties develop over time. Regarding lexical variation for instance, each variety may have a specific word (variant) for a particular meaning (variable). These standard varieties, contrary to common belief, are not static but are in constant flux as ‘standardization [itself] is an ongoing process’ (Pedersen, Citation2005, p. 174; see also Dollinger, Citation2019, pp. 10–12).

Clyne (Citation2004, p. 297) states that pluricentric varieties are ‘usually asymmetrical’ and therefore differentiates between D(ominant) and O(ther) varieties – the latter was later renamed non-dominant as an unambiguous antonym (Muhr, Citation2016, p. 25) –, providing a list of ten characteristics in how far these varieties differ from each other. These include, amongst others, the assumption by speakers of dominant varieties that non-dominant varieties are ‘deviant, non-standard, exotic, cute and somewhat archaic’ (Clyne, Citation2004, p. 297) or that the self-governing entity of the dominant variety has ‘better resources to export their variety in language teaching programs’ (Clyne, Citation2004). It must be noted that not all characteristics apply to all pluricentric languages, however, commonalities can be found.

2.2. Language variation in Chinese

Chinese belongs to the Sino-Tibetan language family, in which it constitutes its own language group. Other language groups split into various branches that are each comprised of multiple languages. In contrast, Chinese is not broken up any further and is thus located on the same level as, for instance, Germanic within the Indo-European language family. It is for this reason that the denotation Chinese acts as an umbrella term that encompasses more varieties than other language names, e.g. German (see Section 2.3).

Yet, the notion of Fāngyán (方言) provides a tool to distinguish between Chinese varieties. As the direct translation of local speech misled many to believe Fāngyán are non-standard varieties (see, e.g. Mair, Citation1991, p. 4), this contribution uses the Mandarin term to refer to these varieties (for a detailed discussion on this choice, see Kaltenegger, Citation2020b, pp. 2–5). There is no clear consensus on the definition of and differentiation between Fāngyán (Kurpaska, Citation2010, pp. 25–62), yet the most common division identifies seven major Fāngyán groups (Kurpaska, Citation2010, p. 58): the only Northern Fāngyán Mandarin (官話, Guānhuà) as well as the six Southern Fāngyán Gan (贛, Gàn), Hakka (客家, Kèjiā), Min/Hokkien (閩, Mǐn), Wu (吳, Wú), Xiang (湘, Xiāng) and Yue/Cantonese (粵, Yuè). The differences between these Fāngyán ‘amount, very roughly, to 20% in grammar, 40% in vocabulary, and 80% in pronunciation’ (DeFrancis, Citation1984, p. 63; based on Xu 1982), hence they are mutually unintelligible. Some argue that the ‘more or less common script’ (Clyne, Citation2004, p. 29; see also, e.g. Bradley, Citation1992, p. 305) unifies the different Fāngyán. Yet, Mandarin has exerted great influence on the Chinese script for over a millennium, causing the script system to be better adjusted to Mandarin than other Fāngyán.

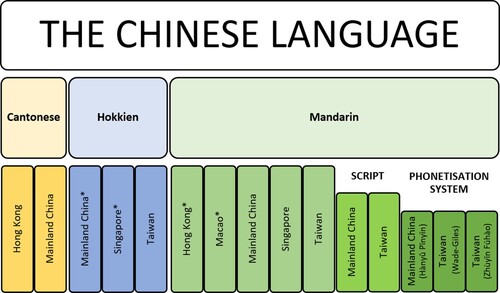

For the application of pluricentricity to Chinese (see ), Kaltenegger (Citation2020b) used each Fāngyán as a point of departure. ThreeFootnote2 of the above-mentioned Fāngyán are used in multiple self-governing entities. In the case of Cantonese, the standard variety of Hong Kong is more dominant than that of Mainland China (Bauer, Citation2018; Groves, Citation2010). As for Hokkien, there could exist up to three different standard varieties, yet only the Taiwanese variety is in the process of being officially standardised (MOE, Citation2012, Citation2013). Mandarin is the most diverse and dominant Fāngyán. All in all, there could be up to five different standard varieties of Mandarin, the most established ones being Mainland Chinese Mandarin and Taiwanese Mandarin. The script and phonetisation systems used in these two centres differ as well – the simplified script and Hànyŭ Pīnyīn (漢語拼音) is commonly used in Mainland China, the traditional script alongside with Wade-Giles and Zhùyīn Fúhào (注音符號) in Taiwan.

2.3. Language variation in German

German belongs to the Indo-European language family and forms the WestGermanic branch together with, e.g. English and Dutch of the Germanic group. Between the thirteenth and sixteenth century, many European languages went through a natural process of dialect mixture (Thomason & Kaufman, Citation1988, pp. 209–210) and by means of nation-building various independent languages came into existence. It is for these reasons that German is neither as heterogenous as Chinese, nor its classification as contested. Nevertheless, German is described as the probably most diverse language in Europe (Barbour & Stevenson, Citation1998, p. 2).

A peculiarity of German pluricentricity is that it occurs in a continuous speech area (Dollinger, Citation2019, pp. 12–14). Yet, the geographic areas that nowadays make up Austria or Germany, respectively, underwent very different socio-political and cultural developments, which led to independent standard varieties (Clyne, Citation1995, p. 31).

German is a recognised pluricentric language with three full centres – Germany, Austria and Switzerland (see Ammon, Citation1995). Among the three, German Standard German is the most dominant standard variety due to the size, political and economic power of its centre. A manifestation of this dominance is what Clyne (Citation1995, p. 31) calls the ‘linguistic cringe’ – an attitude of speakers of a non-dominant variety, in which they perceive the dominant variety as more correct than their own. This could be found for speakers of both the Austrian (de Cillia & Ransmayr, Citation2019, pp. 145–153) and Swiss standard varieties (Scharloth, Citation2005). This also mirrors a characteristic by Clyne (see Section 2.1), which states that speakers of dominant varieties (such as German Standard German) dismiss non-dominant standard varieties (e.g. Austrian Standard German) as non-standard.

2.4. Perception of language variation of Mandarin and German

The following study revolves around the discursive constructions of two speakers who take up a dual role – each of them is both an expert in their language and a learner of the other person’s expert language. For this reason, the perception of language variation is crucial from both the expert speaker’s and learner’s perspective. Since the participants in our study are speakers from Austria and Taiwan, we mainly present studies that focus on these geographical regions.

One important general finding is that speakers often struggle to conceptualise language variation, as they lack the terminology for its description. This is the case in a large-scale study by de Cillia and Ransmayr (Citation2019) in which the participating pupils showed difficulties conceptualising Austrian language variation. Cai and Ebsworth (Citation2017, p. 518) report on similar challenges: In their study on the perception of international and US-American Chinese bilingual graduate students and Mandarin language teachers regarding Fāngyán, they conclude that their ‘interviewees thought that it is complex to define or explain the concept of fāngyán’.

In terms of the perception of Austrian German, de Cillia and Ransmayr (Citation2019, p. 127) mention that Austrian pupils associated the term with family, closeness, tradition and culture, and were inclined to think of non-standard varieties instead of a standard variety of German. This can also be observed in the Chinese context, as Southern Fāngyán are commonly called ‘home languages’ (Tien, Citation2016, p. 43) and are perceived as dialectal (see Section 2.2).

Regarding the perception of dialects, de Cillia and Ransmayr (Citation2019) show that from the perspective of dialect speakers, knowing/speaking a dialect is described as an important way of creating a sense of community identity (de Cillia & Ransmayr, Citation2019, pp. 128–129), from the non-speakers’ view it is seen as excluding (de Cillia & Ransmayr, Citation2019, p. 214). In contrast, standard language is perceived as including.

To our knowledge, there is only one study (Fink, Citation2016) to date that addresses language variation in a tandem or eTandem context from a learner’s perspective. In preparation of a French/Spanish/German eTandem exchange with learners from Colombia and Austria, the Austrian participants were asked about their opinion on learning a non-dominant variety of their target language. The results reveal that the learners were generally interested in different (standard) varieties of French and Spanish. However, the learners repeatedly expressed their doubts about being exposed to different varieties. From their point of view, mixing varieties could be confusing, they would rather focus on one variety – the dominant variety taught at school – until proficient. The preference for learning the dominant variety of Spanish and French was ascribed to its wide intelligibility.

3. Empirical study

As shown in the literature review (see Section 2.4), speakers often struggle to conceptualise language variation and find adequate terminology. These difficulties are particularly consequential in a tandem learning context, since expert speakers usually do not have the metalinguistic knowledge of trained language teachers, but still serve as an important linguistic resource for their partners (Brammerts, Citation2006, p. 4). Our study is therefore dedicated to investigating the discursive constructions of language variation in a Chinese–German eTandem setting and comprises the following three research questions:

(RQ1) How do the participants address the language variation of Chinese and German in their eTandem conversations?

(RQ2) What attributes do they employ?

(RQ3) How do they position themselves in relation to the discussed varieties?

At the time of the project, ML was enrolled as a college student and had only completed the first semester of a Mandarin elective course, he had never been to a Chinese-speaking region before. GL, a Master degree student of a German studies programme, already had years of learning experience and spent a year abroad in Germany. Hence, their target language level differed greatly and led to German becoming the dominant lingua franca for ML and GL.

3.1. Methodology

The following study adapts the discourse-historical approach (DHA) that was developed in the late 1980s by Ruth Wodak for the analysis of the discursive construction of anti-Semitic stereotypes in (semi-)public discourses in the context of the Austrian presidential campaign of Kurt Waldheim (Wodak et al., Citation1990). Besides the historical dimensions of discourse, DHA is also concerned with aspects of politics/policy/polity (such as nation-building), language policy and multilingualism as well as identity construction, e.g. linguistic identity, both of which are crucial in the discussion of the discursive construction of language variation.

For the following study, we look at three discourse-analytical categories: nomination, predication, and perspectivisation. The first category, nomination, is defined as the ‘discursive construction of social actors, objects, phenomena, events, processes and actions’ (Reisigl, Citation2017, p. 52; emphasis in original) and serves to answer RQ1. Predication, the second category, is the ‘discursive characterization of social actors, objects, phenomena, events processes and actions (e.g. positively or negatively)’ (Reisigl, Citation2017, p. 52; emphasis in original) and provides an answer to RQ2. Lastly, perspectivisation addresses the speaker’s or writer’s stance, e.g. involvement/distance (Reisigl, Citation2017, p. 52) and offers insights for RQ3.

Regarding the study’s data, GL and ML recorded five eTandem conversations, which resulted in 5 hours and 24 minutes of video data. For the following study, only the parts relevant to the research questions (altogether 45 minutes) were selected and subsequently transcribed with GAT2’s (Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem 2) basic transcript convention (Basistranskript) (Selting et al., Citation2009). Data annotation was undertaken with MAXQDA. First, a code book was created based on the literature (see Section 2). As a second step, the data set was coded individually by the authors. Differently coded sections were discussed until a mutual understanding was found. Further analyses were carried out in Excel.

3.2. Results

During their eTandem sessions, GL and ML addressed a multitude of varieties to learn more about their own target language or help their partner gain a better understanding of theirs. In this eTandem dyad, GL is the German learner and Mandarin expert, whereas ML is the Mandarin learner and German expert. Both speakers took up strong positions repeatedly for the languages they are experts in and often encouraged their partners to share more regarding their expert language by cross-linguistic comparisons and follow-up questions.

GL and ML elaborated on all three pluricentric Southern Fāngyán (Cantonese, Hakka, and Hokkien), standard as well as non-standard varieties of the Northern Fāngyán Mandarin (mainly Taiwanese Standard Mandarin, Mainland Chinese Standard Mandarin, and the non-standard variety spoken in Northeastern Mainland China) and the German linguistic context (primarily Austrian Standard German and the non-standard varieties of Vienna and Tyrol). The following presentation and discussion of results provide insights into how the speakers addressed these varieties, what attributes they employed and how they positioned themselves in relation to these varieties.

3.2.1. The Southern Fāngyán Cantonese, Hakka, and Hokkien

The discussion of Cantonese, Hakka, and Hokkien develops from a conversation about a particular German non-standard variety, the Viennese dialect, and its differences to standard German (more on German in Sec. 3.2.3), ML shifts the conversation to the Chinese context with a counter question (see Transcript 1).

GL’s repetition with a slightly rising intonation may be interpreted as a clarification request (01/03Footnote6). Together with the following long pause, it shows uncertainty from his side (01/04). ML follows up with explicitly stating the topic (dialects; 01/05) and what he is particularly interested in (degree of intelligibility for a standard Mandarin speaker; 01/07). Later it becomes apparent what caused the confusion on GL’s side: ML refers in his counter question to China, GL, however, does not appear to feel addressed. He decides to give two separate answers, a short one regarding the Chinese situation, in which he takes up a neutral position, and a more elaborate one concerning the Taiwanese situation, in which he communicates a strong feeling of belonging through the repeated usage of the personal pronouns wir (we; e.g. 02/05) and unser (our).

In GL’s depiction of the Taiwanese situation, Hokkien plays a central role. In our data, Hokkien is predominantly referred to as taiwanesisch (Taiwanese; n = 20; e.g. 02/01), its alternative label in German taiwanisch (n = 2) or its Mandarin name Táiyŭ (台語; n = 3). Interestingly, GL calls Hokkien both a Dialekt (dialect; n = 1) and a Sprache (language; n = 1). He emphasises that, even though some young people do not speak Taiwanese, he can (02/09–10).

In his presentation of Hokkien, partially incited by ML, GL focuses on three aspects: (1) Hokkien’s prevalence and significance in Taiwan, (2) its differences in pronunciation compared to Mandarin, and (3) its script.

First, according to GL, Hokkien is spoken by most Taiwanese (02/01), while it is more widely spoken in Southern Taiwan (02/03) than Northern Taiwan. This topic is further developed by GL as he explains that wir (we; =Southern Taiwanese; 02/05) sometimes make fun of Northern Taiwanese not being able to speak Hokkien. This shows that not being able to speak Hokkien as a Taiwanese person is seen as a flaw, something to make fun of. In addition, GL describes Hokkien as the language of the older generation (02/07), not so much of the younger generation (02/09).

Second, regarding the differences between Hokkien and Mandarin, GL describes Hokkien as a ganz andere sprache (completely different language) with an entirely different pronunciation due to its past influence from Japanese (Transcript 3).

Third, Hokkien is characterised by GL as a non-literate language since it lacks an own official script system and further explains that the characters used for writing Mandarin are borrowed to write Hokkien (Transcript 4). GL generally presents writing in Taiwanese as complicated.

Hakka is mostly referred to by its common German/English name Hakka (n = 10, e.g. 05/03) or its Mandarin equivalent Kèjiāhuà (客家話; n = 3). Similar to his presentation of Hokkien, GL labels Hakka as both a Dialekt (dialect; n = 2) and a Sprache (language; n = 1). It is noteworthy that GL tells his partner that Hakka is not just spoken in Taiwan but also in Mainland China.

In contrast to Hokkien, GL does not present Hakka as a significant part of being Taiwanese. For him personally, Hakka is attributed to the older generation due to his grandparents. In this context, GL narrates a common phenomenon of his childhood that his grandparents code-switched to Hakka, a variety he does not understand and therefore had an excluding effect on him, when they were dissatisfied with his behaviour (05/01–07). He states that he does not understand any Hakka now (05/08–09).

In comparison to Hokkien and Hakka, which were brought up by GL, Cantonese was initially mentioned by ML. The speakers referred to it mostly by Kantonesisch (Cantonese; n = 5). Unaware of the correct terminology in German, GL creatively introduced his own coinage Kantonisch (‘Cantonian’; n = 2). This word resembles Taiwanisch, the alternative label for Taiwanese besides Taiwanesisch – yet Kantonisch is not commonly used in German.

Out of the three Southern Fāngyán, GL portrayed Cantonese as the most distant Fāngyán since his contact with Cantonese is limited to occasional encounters with Cantonese speakers (06/01) or hearing it on TV (06/07). In his elaborations on the degree of mutual intelligibility between Cantonese and other Fāngyán, GL’s position is rather fluid. At first, he remarks that he does not understand any Cantonese (06/03) but immediately softens the strong statement by referring to his Cantonese exposure on TV and his ability to grasp a few words (06/05–07), only to finally conclude with yet another amplified statement of him only understanding little Cantonese (06/11).

3.2.2. The Northern Fāngyán Mandarin

In comparison to the discussion of the Southern Fāngyán, Mandarin was addressed repeatedly throughout the recordings, since Mandarin is the target language of ML. The speakers mostly referred to Mandarin as Chinesisch (Chinese; n = 28). By contrast, Mandarin (n=5) was used considerably less. ML was the first to introduce the term Mandarin (wie heißt diese dies/also ma/man sagt ja mandaRIN-;‘how is this called/well yo/you say mandaRIN-‘), which GL adopts later on in the conversation, however, the data shows that he is more accustomed to using Chinese than Mandarin (und (.) chinesisch, (.) also mandarin diese chinesisch,; ‘and (.) chinese, (.) well mandarin this chinese’,). ML also uses the term Hochchinesisch (High Chinese; 07/03) and conceptualises Hochchinesisch and Dialekt (dialect) as a contrastive pair to refer to standard and non-standard respectively. Moreover, GL and ML refer to non-standard Mandarin as umgangssprachlich (colloquial; 07/06).

Non-standard Mandarin is associated with regional variation/differences in pronunciation (e.g. dialects of Northeastern Mainland China; 08/01). GL describes the Mandarin dialect of Northeastern Mainland China as totally different in terms of pronunciation (08/04) and difficult to understand for him as a native speaker of the Taiwanese standard variety of Mandarin (08/07–08). He therefore assumes that dialectal Mandarin must be even more challenging to understand for ML (08/09).

The assertion of GL is corroborated during a sequence, in which ML narrates an anecdote about his actual experience with non-standard Mandarin. ML describes non-standard variation as ‘unintelligible’, ‘so hard [to understand]’ and therefore excluding (wo (.) wo ting bu dong weil’s (.) weil’s so schwer war; ‘I (.) I don’t understand [N. B.: said in Mandarin] because (.) because it was so difficult;’).

Standard Mandarin is – on the other hand – perceived as including by ML. From ML’s point of view, Mandarin is understood by everybody in China, while other Fāngyán (labelled as dialects by ML), such as Cantonese, are not (Transcript 9).

Regarding standard varieties of Mandarin, ML and GL addressed Taiwanese Standard Mandarin and Mainland Chinese Standard Mandarin. The discussions arise ad hoc from situations, in which it becomes apparent that ML’s target language is influenced by Mainland Chinese Standard Mandarin, while GL is an expert of Taiwanese Standard Mandarin. The two standard varieties are constructed as two distinct entities by GL, which are clearly distinguishable from each other. Their differences are discussed in terms of (1) vocabulary, (2) script system and (3) phonetisation system.

First, during the discussion of ML’s plans to study abroad in Mainland China, GL addresses the difference between Mandarin in Mainland China and Mandarin in Taiwan in terms of word choice/phrasing on a general level. From his perspective, spoken Mandarin in Mainland China and Taiwan is different but mutually intelligible and therefore unproblematic (Transcript 10).

Occasionally, GL provides a variant of Taiwanese Standard Mandarin when discussing vocabulary that ML has learnt in his Mandarin class. For example, during a sequence, in which ML and GL negotiate the word ‘xīngqí/qī’ (星期), GL introduces the variant ‘lǐbài‘ (礼拜). He describes it as colloquial language even though it is standard (Taiwanese) Mandarin (man sagt auch (.) also (.) denke (-) wie bei umgangssprache (.) li3bai4YI1; ‘you can also say (.) well (.) I think (-) like in colloquial language (.) li3bai4 YI1’).

Second, differences between the script system used in Mainland China and Taiwan are addressed during the negotiation of the character ‘礼/禮’. ML is only familiar with ‘礼’ that GL refers to as simplification chinesisch (,simplification‘ Chinese, i.e. simplified Chinese; 11/01), whereupon GL introduces the traditional (11/03) variant 禮 in the chat window. He further elaborates that the traditional variant is sehr kompliziert (very complex) (11/04), which ML agrees with (11/05). To legitimise the usage of such complex characters, GL immediately follows up with an argument that justifies this difficult way of writing: from his perspective, this is the originale Chinesisch (original Chinese; 11/06), which is not used in Mainland China anymore (11/08). The sequence concludes with an agreement of GL and ML that the prevalence of the simplified character system used in Mainland China is unfortunate and associated with a sense of loss (11/09–10).

Third, the discussion on phonetisation systems of Mandarin arises from the negotiation of the word bìxū (必須), which ML tried to write down in Hànyŭ Pīnyīn. He complains about his difficulties with Hànyŭ Pīnyīn. GL states he does not feel proficient in Hànyŭ Pīnyīn either (12/01) due to the different phonetisation systems used in Taiwan, China and Hong Kong (12/04–05). He distinguishes between Hànyŭ Pīnyīn, the official phonetisation system in Mainland China (12/06–07) and the Taiwanese phonetisation system (Zhùyīn Fúhào), for which he does not have a name (12/09). GL describes Zhùyīn Fúhào as a different form of transliteration that differs visually from the Latin alphabet (12/10).

3.2.3. German

Regarding the German linguistic context, it was primarily Austrian Standard German and the non-standard varieties of Vienna and Tyrol that were addressed during the eTandem sessions. Similar to the situation of Mandarin, the terms Hochdeutsch (High German; e.g. 13/02) and Dialekt (dialect; e.g. 13/12) are used to refer to standard and non-standard German. Standard German is regarded by GL as the official language that is found in German textbooks (13/01). According to ML, ‘textbook German’ differs from how many people actually speak (13/05), namely im Dialekt (dialectally; 13/07). He specifies that nowadays, non-standard German is rather spoken by the older generation (13/09–11), while the younger generation refrains from doing so (13/11–12).

Again, similarly to the Mandarin situation, non-standard German is associated with regional variation in pronunciation. ML describes the pronunciation differences of standard and non-standard German based on the word ‘gelb’ (yellow), which is, according to ML, incorrectly pronounced as ‘göb’ (IPA: gœb) in the Viennese dialect (Transcript 14).

To further elaborate on non-standard German, ML narrates an anecdote about his Chinese landlady, who speaks some German but no dialect, and a Viennese plumber, who only spoke in dialect to her. The landlady had trouble understanding what the plumber said and called ML for help. ML states that for him (as a ‘native speaker’ of German from Eastern Austria/Vienna) Viennese is intelligible (Transcript 15).

However, for ‘non-native speakers’ of German, such as the landlady, it is essential that interlocutors speak ‘beautifully’ (=Standard German; 16/02) in order for her to be able to understand.

ML also empathically imagines to be in the landlady’s position and understands the challenges she has to face when confronted with German non-standard (Transcript 17).

Even though ML states that, for him, Viennese is intelligible, other dialects, such as Tyrolean, might not be (Transcript 18).

The pluricentric variation of German is only sporadically addressed. These few instances are limited to the discussion of word choice (Trancript 19).

3.2.4. Summary and discussion

To answer RQ1 (How do the participants address the language variation of Chinese and German in their eTandem conversations?) we focused on the nomination strategies used by GL and ML. The two Southern Fāngyán Hakka and Hokkien were referred to as Hakka and Taiwanesisch/Taiwanisch (Taiwanese/Taiwanian) in German, and as Kèjiāhuà and Táiyŭ in Mandarin. GL’s use of the term Táiyŭ (Tai[wanese] language) as well as his statement regarding people in a region of Mainland China also speaking Taiwanese indicates that, for GL, there is a clear link between Taiwan and Hokkien, with Taiwan being the most dominant pluricentric centre among multiple centres of this Fāngyán. Cantonese was referred to as Kantonesisch/Kantonisch (Cantonese/Cantonian). A noticeable discrepancy between Hokkien and Hakka, on the one hand, and Cantonese, on the other, is that the speakers did not mention any Mandarin term for Cantonese, nor did they speak of any other speech area of Cantonese besides Hong Kong, leading to a monocentric depiction of Cantonese.

The analysis of nomination strategies for Mandarin showed that GL mostly referred to Mandarin with Chinesisch (Chinese), while ML preferred to use Mandarin for his target language. Overall, the term Chinese was used almost six times as much compared to Mandarin.

Since Chinese is more complex regarding language names, the nomination strategies applied to German, for both standard and non-standard varieties, were rather straightforward and not as heterogenous as their Chinese counterparts. In terms of pluricentric variation of standard German and standard Mandarin, GL and ML discussed variation between Austria and Germany as well as Mainland China and Taiwan, however, the concept of pluricentricity was not mentioned explicitly.

RQ2 (What attributes do they employ?) addresses the predication strategies used by GL and ML. The Southern Fāngyán were described as dialects, which is not particularly surprising, since this is the common term in academic literature (e.g. Mair, Citation1991) as well as everyday language. It is, however, noteworthy that Hokkien and Hakka were also referred to as languages by GL when comparing them to Mandarin on a structural/linguistic level. GL views Hokkien as an integral part of being Taiwanese. Not being able to speak Hokkien as a Taiwanese person is a flaw to him that can be made fun of, indicating that knowing Hokkien has positive connotations. Hokkien is, however, also described as a deficient language with a need to borrow characters (from Mandarin), as it lacks an own script system. One association that Hokkien and Hakka share is with the older generation. For GL, Hakka is attributed to the older generation due to his grandparents. Compared to Hokkien, Hakka is not mentioned as a significant part of being Taiwanese. In comparison to Hokkien and Hakka, which were brought up by GL and previously unknown to ML, Cantonese was initially mentioned by ML. This suggests that Cantonese is the only other Fāngyán besides Mandarin that ML is familiar with. Out of the three Southern Fāngyán, GL portrays Cantonese as the most distant Fāngyán, since his contact with it is limited to hearing it on TV or occasional encounters with Cantonese speakers.

For the description of Taiwanese Standard Mandarin terminology with both positive and negative connotations were used. GL refers to a Taiwanese Mandarin variant as colloquial, suggesting that Taiwanese Mandarin is potentially not seen as an independent standard variety. This devaluation reflects what Clyne (Citation1995, p. 31) calls the ‘linguistic cringe’ (see Section 2.4). As opposed to this, the script system used in Taiwan was referred to in a positive manner with terminology such as traditional and original. Predication strategies with both positive and negative connotations were used for describing Mainland Chinese Mandarin as it was referred to as the official language and the script system as simplified/simplification. The notion simplified/simplification may not be automatically seen as pejorative, since simplified characters is the common term for the script system used in Mainland China, however, in this case, the course of the conversation showed that simplified clearly receives a negative connotation, and thereby traditional and original receive a positive connotation.

In the description of the German language situation (standard vs. non-standard), clear dichotomies could be found. One contrastive pair that was particularly evaluative referred to Standard German pronunciation as beautiful and to the pronunciation of non-Standard German as incorrect.

RQ3 (How do they position themselves in relation to the discussed varieties?) is dedicated to the perspectivisation strategies applied to the various varieties addressed in the eTandem conversations. GL and ML take up strong positions repeatedly for the languages they are experts in, i.e. GL for Chinese and ML for German. Southern Fāngyán are generally presented as exclusive to certain groups of speakers. GL discusses his difficulties with understanding Cantonese at length and refers to Hakka and Hokkien as languages, suggesting a clear demarcation between the four. For GL, Hokkien is the most important Fāngyán. He shows pride in speaking Hokkien and connects Hokkien strongly with Taiwan. In his elaborations on the degree of intelligibility of Cantonese and other Fāngyán, EK’s position is rather fluid. Regarding Hakka, this ambiguity is not present.

As opposed to the Southern Fāngyán, Standard Mandarin is presented as inclusive – a finding that is in line with de Cillia and Ransmayr’s (Citation2019) study on Austrian German. Both the Mandarin Standard in general as well as Taiwanese Standard Mandarin in particular are presented as inclusive by GL, whereas certain aspects of Mainland Chinese Mandarin (e.g. the phonetisation system Hànyŭ Pīnyīn and the pronunciation of Northeastern non-standard Mandarin) are predominantly perceived as excluding. Yet, GL emphasises that even the varieties he struggles with all belong to the same Fāngyán, namely Mandarin. By doing so, GL demonstrates that he differentiates very clearly between the standard and non-standard varieties of Mandarin on the one hand, and other Fāngyán such as Hakka on the other. This is in line with the theory section in that it shows that Chinese is an umbrella term that overgeneralises the heterogeneity of varieties it encompasses (see Section 2.2).

Most statements by ML with perspectivisation strategies address German non-standard varieties. This tendency to focus only on Austria’s non-standard varieties instead of its standard variety could also be found in the study conducted by de Cillia and Ransmayr (Citation2019) amongst pupils in Austria. ML does mention instances in which the Austrian dialect gave him access to certain persons/groups (e.g. the plumber), yet his focus lies on situations that excluded persons because of their lacking skills in non-standard German. This expressed empathy with learners of their language can be found in both speakers. ML relives a situation from the viewpoint of his landlady, emphasising that it must be impossible for her to know that the dialectal version of Rohr is Rehrl. In contrast, GL puts himself directly in ML’s position after explaining that he sometimes struggles to understand people from Northeast China. GL assumes that it must be even harder for ML to grasp as a non-native speaker.

It is noteworthy that the characterisation of Southern Fāngyán and non-standard German shared one similarity: Both are perceived as excluding because they are not spoken by the majority and are very specific to certain communities. These results correspond with de Cillia and Ransmayr’s (Citation2019) findings on the role and perception of dialects vs. standard language.

4. Pedagogical implications

As mentioned at the beginning of the discussion, the context of our data is a tandem situation, in which learners come together to practice their target language. As suggested by Fink (Citation2016) and shown in our own tandem observations, learners are open to getting to know different (standard) varieties of their target language. We believe that diversity in varieties in the context of language learning in general and tandem learning in particular poses an opportunity rather than an obstacle. Due to the participants’ dual role in a language tandem – acting as a language learner and language expert simultaneously – they are prompted to reflect on both tandem languages. This means that a language tandem does not only offer potential opportunities to learn about target language variation but may also increase speakers’ language awareness regarding their own expert language. With that said, Dollinger’s (Citation2019, p. 113) statement concerning pluricentricity in formal teaching situations is also applicable to the (e)Tandem context, as these learning experiences need to ‘be conceived from an identity-confirming, intercultural communication and peace-promoting vantage point of mutual respect and not […] from a brute nationalist angle’.

In order for these potential prospects to become actual learning opportunities, it is, however, necessary that participants receive adequate pedagogical support. Depending on the formality of the tandem situation, different pedagogical strategies are possible. Formally integrated and non-formal tandems could receive a coaching for raising awareness and conversation tasks that prompt critical discussions on language variation. Creating a complementary variant dictionary could serve as a strategy to support/foster long-term memory. Tandem programmes and applications that connect learners but do not offer further pedagogical guidance, could go beyond the commonly used categories of ‘target language’ and ‘offered language’ and let the participants provide more in-depth, variety-specific information about themselves.

5. Limitations and future perspectives

Our empirical study is a case study that focuses on the subjective perspective of two individuals. Our data corpus is limited, however, it consists of non-elicited, authentic data, since conversation topics during the tandem sessions were not promoted by the researchers but have been initiated by the participants themselves. For this reason, socially desirable answers, which are particularly relevant when discussing politically sensitive issues, could be avoided. This is of particular interest as Chinese (standard) language variation is severely underresearched. Future studies ought to extend the pluricentricity debate to the Chinese context, compile detailed descriptions of Chinese standard varieties and analyse how they are perceived by various groups of speakers.

Acknowledgments

We thank the students for participating in this study as well as the anonymous reviewers and Lydia Hwa-Che Medill Catedral for their thoughtful comments on previous versions of the text.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this contribution, we use the umbrella term Chinese only when addressing the entirety of Chinese, i.e. Mandarin as well as all other Fāngyán.

2 Hakka is excluded in the discussion on Chinese pluricentricity since its speech area is highly scattered, which hinders the development of different standard varieties. Other Southern Fāngyán are not discussed in this context, as they are predominantly used in a single self-governing entity, namely Mainland China.

3 The more established term for this area of research is Chinese as a foreign language (CFL). However, as Chinese is an overly broad term that does not only include Mandarin but also Southern Fāngyán such as Cantonese and CFL merely revolves around the learning of Mandarin, we plead for addressing the research object in a more precise manner, namely Mandarin as a foreign language.

4 We confirm all the subjects have provided appropriate informed consent.

5 The English translations of the transcripts try to mirror the German originals as closely as possible, including standard/non-standard variation and any mistakes.

6 The number prior to the slash refers to the transcript, the number after the slash to a particular line in this transcript, e.g. 01/03 indicates Transcript 1, line 3.

References

- European Commission. (2012). Spezial Eurobarometer 385. Die europäischen Bürger und ihre Sprachen. http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/archives/ebs/ebs_386_de.pdf

- MOE [Ministry of Education]. (2012). User Manual for Romanizing the Minnan Language. Retrieved February 1, 2020, from https://bit.ly/2ucjASR

- MOE [Ministry of Education]. (2013). Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan. Retrieved February 1, 2020, from https://bit.ly/2OmNdYv

- Auswärtiges Amt. (2020). Deutsch als Fremdsprache weltweit. Datenerhebung 2020. Berlin: Auswärtiges Amt. Retrieved October 8, 2020, from https://www.goethe.de/resources/files/pdf204/bro_deutsch-als-fremdsprache-weltweit.-datenerhebung-2020

- Ammon, U. (1995). Die deutsche Sprache in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz: Das Problem der nationalen Varietäten. De Gruyter.

- Appel, M. C. (1999). Tandem language learning by E-Mail: Some basic principles and a case study. CLCS Occasional Paper, No. 54. Dublin: Trinity College.

- Barbour, S., & Stevenson, P. (1998). Variation im Deutschen: soziolinguistische Perspektiven. Walter de Gruyter.

- Bauer, R. S. (2018). Cantonese as written language in Hong Kong. Global Chinese, 4(1), 103–142. https://doi.org/10.1515/glochi-2018-0006

- Bradley, D. (1992). Chinese as a pluricentric language. In M. Clyne (Ed.), Pluricentric languages. Differing norms in different nations (pp. 305–323). Mouton de Gruyter.

- Brammerts, H. (2006). Tandemberatung. In: Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachen-unterricht, 11/2.

- Cai, C., & Ebsworth, M. E. (2018). Chinese Language varieties: Pre- and in-service teachers’ voices. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 39(6), 511–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2017.1397160

- Clyne, M. (1995). The German language in a changing Europe.. Cambridge University Press.

- Clyne, M. (2004). Pluricentric Language / Plurizentrische Sprache. In U. Ammon (Ed.), Sociolinguistics: An international handbook of the science of language and society (2nd ed., pp. 296–300). Mouton de Gruyter.

- Cziko, G. A. (2004). Electronic tandem language learning (eTandem): A third approach to second language learning for the 21st century. CALICO, 22(1), 25–39.

- de Cillia, R., & Ransmayr, J. (2019). Österreichisches Deutsch Macht Schule. Böhlau Verlag.

- DeFrancis, J. (1984). The Chinese language. Fact and fantasy. University of Hawaii Press.

- Dollinger, S. (2019). The pluricentricity debate: On Austrian German and other Germanic standard varieties. Routledge.

- El-Hariri, Y. (2016). Learner perspectives on task design for oral-visual eTandem language learning. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 10(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2016.1138578

- Fink, I. E. (2016). Plurizentrik im E-Tandem. In J. Renner, I. E. Fink, & M.-L. Volgger (Eds.), E-Tandems im schulischen fremdsprachenunterricht (pp. 105–127). Löcker Verlag.

- Groves, J. M. (2010). Language or dialect, topolect or regiolect? A comparative study of language attitudes towards the status of Cantonese in Hong Kong. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 31(6), 531–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2010.509507

- Kaltenegger, S. (2020a). Standard language variation in Chinese—some insights from both theory and practice. Critical Multilingualism Studies, 8(1), 51–79.

- Kaltenegger, S. (2020b). Modelling Chinese as a pluricentric language. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2020.1810256

- Kloss, H. (1967). Abstand languages’ and, ausbau languages’. Anthropological Linguistics, 9(7), 29–41.

- Kloss, H. (1978). Die Entwicklung neuer germanischer Kultursprachen seit 1800. (2nd ed.). Düsseldorf: Schwann.

- Kurpaska, M. (2010). Chinese language(s): A look through the prism of The great Dictionary of modern Chinese dialects. De Gruyter Mouton.

- Mair, V. H. (1991). What Is a Chinese “dialect/topolect”? reflections on some Key sino-English terms. Sino-Platonic Papers, 29, 1–31.

- Milroy, J. (2001). Language ideologies and the consequences of standardization. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 5(4), 530–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9481.00163

- Milroy, J., & Milroy, L. (1985). Authority in language. Investigating language prescription and standardization. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Muhr, R. (2016). The state of the art of research on pluricentric languages: Where we were and where we are now. In R. Muhr (Ed.), Pluricentric languages and Non-dominant varieties worldwide. Part I: Pluricentric languages across continents. Features and usage (pp. 13–38). Peter Lang.

- Pedersen, I. L. (2005). Processes of standardisation in scandinavia. In P. Auer (Ed.), Dialect change: Convergence and divergence in European languages (pp. 171–195). Cambridge University Press.

- Reisigl, M. (2017). The discourse-historical approach. In J. Flowerdew, & J. E. Richardson (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of critical discourse studies (pp. 44–59). Routledge.

- Renner, J. (2019). Sprachenlernen in Chinesisch – Deutsch eTandems. Eine konversationsanalytische Untersuchung des Lernprozesses hinsichtlich Chinesisch als Zielsprache. Wien: dissertation thesis.

- Scharloth, J. (2005). Zwischen Fremdsprache und nationaler Varietät. Untersuchungen zum Plurizentrizitätsbewusstsein der Deutschschweizer. In R. Muhr (Ed.), Standardvariationen und Sprachideologien in verschiedenen Sprachkulturen der Welt / standard variations and language ideologies in different language cultures around the world (pp. 21–44). Lang.

- Selting, M., Auer, P., Barth-Weingarten, D., Bergmann, J., Bergmann, P., Birkner, K., Couper-Kuhlen, E., Deppermann, A., Gilles, P., Günthner, S., Hartung, M., Kern, F., Mertzlufft, C., Meyer, C., Morek, M., Oberzaucher, F., Peters, J., Quasthoff, U., Schütte, W., … Uhmann, S. (2009). Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem 2 (GAT 2). Gesprächsforschung – Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion, 10, 353–402.

- Stewart, W. A. (1968). A sociolinguistic typology for describing national multilingualism. In J. A. Fishman (Ed.), Readings in the sociology of language (pp. 531–545). Mouton.

- Thomason, S., & Kaufman, T. (1988). Language contact, creolization and genetic linguistics. University of California Press.

- Tien, A. (2016). Perspectives on „Chinese“ pluricentricity in China, greater China and beyond. In R. Muhr (Ed.), Pluricentric languages and non-dominant varieties worldwide: Part I: Pluricentric languages across continents: Features and usage (pp. 41–60). Peter Lang.

- Van Rooy, R. (2020). Language or dialect? The history of a conceptual pair. Oxford University Press.

- Wodak, R., Nowak, P., Pelikan, J., Gruber, H., de Cillia, R., & Mitten, R. (1990). Wir sind alle unschuldige Täter – Diskurshistorische Studien zum Nachkriegsantisemitismus. Suhrkamp.