ABSTRACT

In 2019, Digital Curation Lab Director Toni Sant and the artist Enrique Tabone started collaborating on a research project exploring the visualization of specific data sets through Wikidata for artistic practice. An art installation called Naked Data was developed from this collaboration and exhibited at the Stanley Picker Gallery in Kingson, London, during the DRHA 2022 conference. Through data analysis, employing Wikidata tools, this creative work employs a data set depicting prehistoric female figurines held by Heritage Malta. The artistic research aims to develop a creative workflow model for processing essential information about art collections, museum policies, and ways to engage with cultural heritage through data. This article outlines the key elements involved in this practice-based research work and shares the artistic process involving the visualizing of the scientific data with special attention to the aesthetic qualities afforded by this technological engagement.

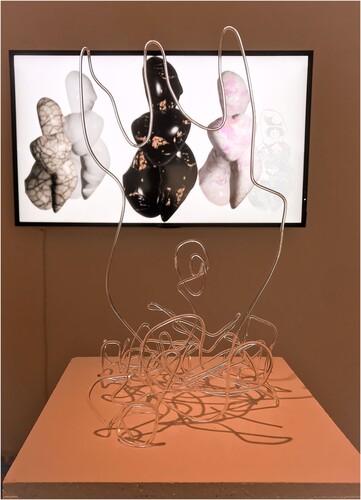

An art installation entitled Naked Data was exhibited at the Stanley Picker Gallery in Kingston, London, during the DRHA 2022 Conference. The installation consisted of a plexiglass structure made by Enrique Tabone from two 1-meter-long transparent rods, bent into shapes derived from images shown on a video projected behind the sculpture. The video art is based on data visualizations from an ongoing research project conducted collaboratively within the University of Salford’s Digital Curation Lab at MediaCityUK. The project revolves around a data set gathered from Heritage Malta’s extensive collection of neolithic female figurines and fragments, found at the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta and the Ġgantija Temple Museum in Xagħra, Gozo ().

Figure 1. Naked Data art installation as exhibited at the Stanley Picker Gallery, September 2022. Photo by Enrique Tabone.

This was our first attempt to present the type of creative extrapolation that the selected data set is able to afford. Over the subsequent months, this work continued to be developed for an exhibition called Prestorjha, presented at Spazju Kreattiv, Malta’s National Centre for Creativity in Valletta, in March 2023. Naked Data stems from two other projects on which we collaborated earlier. The first was the 2020 edition of the Art + Feminism exhibition curated by Toni Sant at Spazju Kreattiv, which featured works by six artists, including Enrique Tabone. The exhibition is one in a series produced in support of the international initiative Art + Feminism, which primarily aims to address the gender gap on Wikipedia regarding articles about art and artists from around the world.Footnote1 Tabone’s work in the 2020 Art + Feminism exhibition was her first exploration of the theme that is central to Naked Data: reimaging the female figure in Malta’s prehistoric art from a feminist perspective.

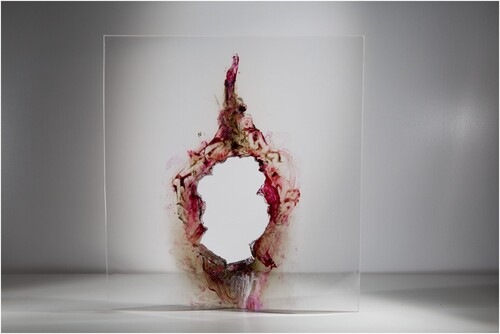

The first series of works created by Tabone in 2020 under the title Pre-Herstory consisted of three plexiglass structures and two video art pieces. These plexiglass works can be divided into two categories. The first category contains works that were developed directly in relation to iconic objects held by Heritage Malta. In the work called Ġismna (Maltese for ‘our body’), the artist works with light and shadows through a structure inspired by the legs on a series of Heritage Malta figurines, to evoke the pervasive double spiral symbols prevalent in the original period on which the works are based (). Another work, called Ġismi (Maltese for ‘my body’) is a life-size transparent plexiglass torso made up of thirty strips – twenty-eight strips, held between two additional strips – modelled on the artist’s own body during the course of one menstrual cycle. This work was developed in response to figurines in Heritage Malta’s collection that can be seen to represent objects potentially intended for prehistoric sexual and pregnancy education.

Figure 2. Ġisimna with double spiral shadow, as exhiibited at Spazju Kreattiv, March 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

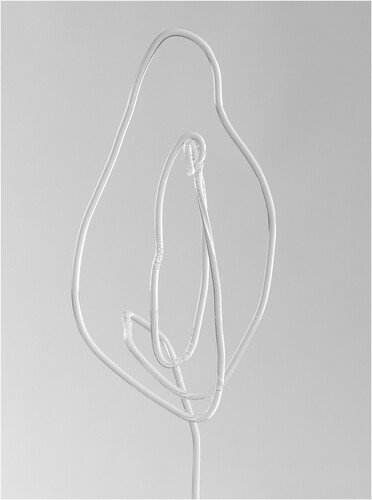

The other category is the artist’s explorations on vulvic symbols. This is a theme that has already appeared in her exhibited outputs earlier, most notably in Om, a striking art object last exhibited at the 2019 Ostrale Contemporary Art Biennale in Dresden, where it was acquired by a private collector (). The vulvic symbol presented during the 2020 exhibition is entitled Fjur and was admittedly created by the artist to initiate a deeper exploration of vulvic symbols within her own body of work. This object is made from one 1-meter transparent plexiglass rod, shaped by the artist in a deliberately fragile vulvic symbol. The delicate nature of the piece is emphasised through the use of shadow and light, which is frequently a key component of Tabone’s sculptural works ().

Figure 3. Om, acquired by a private collector from the Ostrale 2019 Contemporary Art Biennale. Photo by Jean Marc Zerafa.

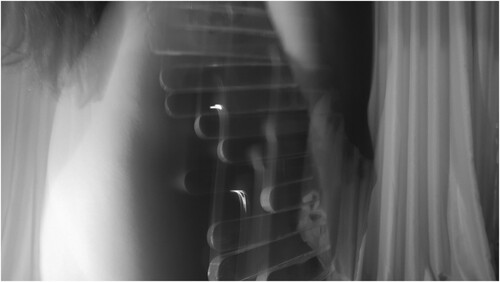

The first of the two video works from the Pre-Herstory series is called Not Venus. It contains luministic black and white photos from an intimate performance that the artist staged for her camera while wearing her plexiglass structure Ġismi over her naked body (). The title of this video performance is a feminist negation of the title assigned to one of the most visible objects in Heritage Malta’s collection. The Maltese prehistoric female figurine has been named by male archaeologists in a way that aligns it with an art historical linage, particularly following Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (c.1458), attributing ideal female beauty to the ancient Roman mythological goddess of love, associated with beauty, desire, sex and fertility. Malta’s is evidently not the only collection of prehistoric female figurines to attract the Venus moniker; the so-called Venus of Willendorf found in Austria in 1908 is likely a better-known example of this. About thirty other such prehistoric ‘Venus’ figurines have been found and named around the world, some of which have also been the subject of analysis from interdisciplinary feminist perspectives.Footnote2

This essential context is embodied in Tabone’s study – through a line drawing which may be seen as a full-body, albeit headless, self-portrait – on the so-called Venus of Haġar Qim, presented in her other video work in this series ().Footnote3 Pre-Herstory (Citation2020, video) is a feminist manifesto that exposes the way historical interpretations of the female figure in Malta’s prehistoric art, often highlight misogynist readings describing the objects as ‘gross’, ‘obese’, ‘fat’ and other such derogatory terms not conventionally associated with female beauty.Footnote4 The artist goes one step further in this video work when she aligns herself to a feminist proposal that imagines these female figurines to be the handmade works of women rather than objects created by men (McCoid and McDermott Citation1996).

Figure 6. Venus of Ħaġar Qim as exhibited at Malta’s National Museum of Archaeology. Photo by Enrique Tabone available on Wikimedia Commons, CC-by-SA.

A small number of Maltese modern and contemporary artists have used neolithic symbols or similar motifs in their works. In most cases, these are either landscape paintings featuring the Megalithic temples or, more commonly, works representing prehistoric deity narratives, established by the early twentieth century archaeologists of Malta and Gozo, which in most cases regurgitate Marija Gimbutas’ theories on the mother-goddess of what she calls ‘old Europe’ (Citation1974). No artist has previously looked at the female body in prehistoric objects outside the construct of mother-goddess myths. Art developed from the prehistoric images and objects discovered in Malta is mainly about idealized beauty or figurative paintings reproducing the remains of prehistoric sites.

The Covid-19 pandemic delayed further development of Tabone’s Pre-Herstory series. However, by 2021 she had embarked on an analysis of the gender gap at the University of Salford’s Art Collection, as part of her postgraduate studies in Digital Curation. This sparked an interest in data art and the possibilities it holds for the expansion of her previous works on prehistoric female figurines in Malta. In turn, this led to the process of collecting data about Heritage Malta’s entire collection of female figurines, described later on in this article.

The aim of this research project is to collect, analyse, and store data about prehistoric female figurines in Malta so that it can be visualised in graphic representations. This visualization is both scientific and artistic in its approach: scientific in the way it handles facts and figures associated with them and artistic in its ability to engage in visual storytelling to enables diverse audiences to understand things they may overlook when presented to them in a terms with which they may not be as familiar.

To get a fuller picture of the overarching objective of this practice-based art research project, it is essential to explore more closely five key concepts on which it is built. These are prehistoric female figurines in Malta, open knowledge through Wikidata, data visualization, data art, and a feminist perspective. The close interplay between these five elements, is carefully curated to ensure that whatever is produced as an outcome of this research project is original, in the sense that it relates to insights that have so far not been engaged systematically.

Prehistoric female figurines in Malta

A significant number of prehistoric figurines, largely depicting humans and animals, were discovered and collected in the central Mediterranean island nation of Malta throughout the twentieth century. This followed the earlier identification of specific sites across the Maltese islands as prehistoric remains. The figurines were carved and modelled in local materials, mainly soft globigerina limestone, small pieces of gypsum and stalagmite, baked clay-terracotta, bone, and shell. Their size ranges from miniature and small to large scale. These objects are now held by Heritage Malta, which is the national agency responsible for guarding most of the country’s tangible heritage and presenting it to the public. Specifically, the project presented through this article is concerned with two collections of female prehistoric figurines and fragments held at the National Museum of Archaeology and the Ġgantija Temple Museum.

The style of Maltese anthropomorphic figurines has a particular form that is very distinct when compared with others from the Neolithic Mediterranean. Two particular forms stand out in Malta and Gozo. These are large figures, mostly seated, either naked breasted or fully naked pregnant figures. Nicholas Vella observes that some of the larger stone figures in this collection look like they had removable heads, possibly interchangeable and for various possible ritual uses. (Vella Citation2007, 63)

Human beings tend to want to categorise items to organize things, objects, and ideas around them. Sometimes, this results in attempts to simplify our understanding of the world. A lack of categorisation can lead to greater levels of ambiguity in the interpretation of specific things, whether physical objects or abstract ideas. This seems to be the case for Heritage Malta’s collection of prehistoric figurines, which have historically been overlooked unless simply categorised as statues representing ancient, predominantly obscure or unidentified, deities. The gender of the ‘deity’ is often also ambiguous.

The main themes arising from prehistoric female figurines that are relevant to this art research project revolve around the artistic possibilities afforded by the historical interpretations of these objects. These interpretations are also embedded in the way these archaeological objects have been categorised, or not, by Heritage Malta. In the process, we emphasize a significant shift in attention from ‘prehistoric deities’ to representations of the female body.

In our exploration we have found that research and interpretation on Maltese prehistoric female figurines and fragments has not been updated to these findings. While we have encountered some anecdotal evidence of updating among local heritage professionals, the published research and museum displays have not yet caught up with the revised archaeological interpretations that aim to decolonize gender.

We are drawn to this collection of prehistoric female figurines through a desire to see the collection from a different perspective. By this we mean to explore aspects of the collection that for one reason or another have so far not been evident in the ways that the objects are currently displayed in the museums, in printed publications, or online.

Open knowledge through Wikidata

Open knowledge relates to data or information that ‘is free to access, use, modify, and share … subject, at most, to measures that preserve provenance and openness.’Footnote5 Over the past two decades this concept has been greatly popularised, primarily due to the success of Wikipedia and other open access projects associated directly with it. Wikimedia, the organisation behind Wikipedia and other open knowledge projects such as Wikidata, Wikimedia Commons, and Wiktionary, is just one of several advocates of open access to knowledge. Other proponents are likely also involved with the Open Knowledge Foundation, established in 2004 to promote open ideas.Footnote6

We believe that open knowledge online platforms, particularly those operated by Wikimedia, provide an excellent solution to issues that frequently arise on the sustainability and longevity of digital media projects, especially in the cultural heritage sector. Guided by the FAIR data principles, we find that Wikimedia’s platforms enable us to focus on developing projects such as the one described in this article, safe in the knowledge that the data will be findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable (Wilkinson et al, Citation2016). This is why Wikidata is the preferable choice as a data repository on which to build our project.

Wikidata is a collaboratively edited multilingual knowledge graph, operated through common source open data under a CC-zero license. In simple terms, Wikidata is an open database. Just like other Wikimedia projects, such as Wikipedia, anyone can add and edit data on it freely. It is designed to accommodate queries based on triples, such as how many prehistoric figurines in Malta are made of limestone or any other triple statement containing a subject, predicate, and object. These queries are run through SPARQL, which is a query language for databases in the Resource Description Framework (RDF) format.Footnote7

When a knowledge machine learns, this learning goes into latent space. Data is simply stored statically until it is queried. The stored data awaits our input, requesting to do something with it. The data about prehistoric figurines and fragments in Malta shared on Wikidata can be queried in ways that enable new insights into these collections. As more data becomes available through Wikidata – through references parsed from academic publications and exhibition catalogues – new insights into the ways objects relate to each other may also be discovered. In this way, for example, the collection in Gozo may be better cross-referenced with the one in Malta. Another example is the way knowledge gaps within a collection, including cataloguing errors, can be identified, enabling curators and collection managers to act on them as needed. One such gap in the prehistoric figurines involves the coordinate for the megalithic temples and other sites where the objects were found. Such data would enable a visual map from which to analyse possible patterns in terms of specific properties within the geographic area where the objects were found.

The power of Wikidata is particularly evident in its ability to connect items in the database together through properties that go beyond a specific concern such as a collection of artefacts within a museum. For instance, if an object in the museum inspires a poem, gets featured in a television documentary, or is used as part of a corporate logo, all these aspects can be linked together and queried through this data set. As everything is connected, links to external databases are also possible, especially with Persistent Unique Identifiers for each object in the collection. Through these connections, differences between different data sets can be investigated, while maintaining the potential to combine data sets and sources with existing knowledge stored in Wikidata. Thus, open data creates new possible understandings of the data sources. Such connections are more easily identified through data visualization.

Data visualization

Structured data, available through platforms such as Wikidata, is useful is various ways. However, it is not always easy to extract useful knowledge from the data beyond the obvious, unless it is processed through data visualization tools. About fifty visualization tools have been developed for Wikidata.Footnote8 These data visualization tools are largely used to generate charts (e.g. radar charts, bubble charts, timelines, etc.), trees (e.g. clusters, radial trees, etc.), and maps. Most of them were built for specific projects, such as openArtBrowser, designed to show artworks by the same artist, movement, or motif,Footnote9 or the Histropedia timeline generator, which uses data from Wikipedia and Wikidata to generate timelines from various historical perspectives.Footnote10

According to David McCandless, ‘one of the potentials of [data] visualization is to bring the data down to earth.’Footnote11 What we take this to mean is that visualizing data can help to provide a better understanding of the data set. Such as seeing the ways data items connect to each other via specific properties or how missing data on that same property within a data set can show a gap in knowledge about the subject being visualized. This makes for a realistic insight into the possibility of discovering new information by connecting data. In other words, what the data is unable to communicate directly is also important and useful when attempting to understand data sets more holistically.

Data visualization enables us to look into a collection rather than at a collection. This data science point of view, where the aim is to discover relationships between items within the data set while stitching them together through shared properties. Data humanist Lupi (Citation2017) claims that design serves the data, in the sense that it’s the design you see first in any data visualization. With careful graphic design choices, the viewer should want to know more. As we see it, this level of interpretation leads from data visualization into data art.

Data art

A description of data art that works well in this context is data driven art where the creator relies on the usage of a data set. The artist must respect what the data shows and/or says while becoming an agent for messages embedded in the data itself. As an agent of the data, the artist attempts to convey emotions to the viewer, even if they potentially move far away from what is originally expressed, factually, by the data. As artist Laurie Frick proposes, in data art you ‘take your data back and turn it into something meaningful’ (Citation2015). In this way, data art is not bound within the purview of artists but also of data scientists, data journalist, data visualizers, data analysts, and information illustrators among others. Data art is not strictly a genre of art but rather a range of methods by which data is presented to diverse audiences. We should also add that while most data art is also digital art, in some cases data art may extend into non-digital objects, such as the sculptures and musical scores created by Nathalie Miebach from weather data sets.Footnote12

Artistic practice in data art relies on a data set to convey emotions through specific readings of information held within the data. In this way, data art is not the mere visualization of the data so that it may be better understood but work that aims to elicit some sort of specific reaction from its audience. This applies regardless of whether the artist proposes aesthetic appreciation or an ethical position that involves some interplay with the data itself, if not a combination of both approaches. Either way, data visualization is a first step towards the creation of data art. Data art is data visualized or otherwise aesthetically represented to give a specific experience, or set of experiences, to its audiences. As outputs derived from data may be complex, it is the data artist’s job to turn the visualizations, sounds, or whatever other form the outputs may take, into a work of art that can potentially convey specific emotions or messages to its audiences. This is where the artists technique become a crucial aspect for the best conceptual representation of the data they’re working with and what they ultimately want to do with it. The material form selected by the artist is secondary to all this, and so data art can be presented in any material or form, digital or analogue, from print to sound, and sculpture or immersive environments that employ extended reality technology.

Another significant point to make about data art, especially as we see it relevant to our research project, relates to artistic expression. Data art, as we describe it here, must be developed from data or at least somehow refer to data, even if the starting point is artistic practice. Data art, in this context, cannot rely solely on artistic expression. A work of art in this manner may provide an opportunity for its audiences to appreciate data on which it is based, even if not necessarily at first glance.

Feminist perspectives

Proposing a feminist perspective can be problematic. We aim to simplify the feminist perspectives involved in this project while problematizing the very fact that a feminist perspective is required. This is so because for centuries the female point of view has been too frequently relegated to an inferior position, or mere afterthought, in a broad range of circumstances.

In this project, which deals with prehistoric female figurines, we look at Heritage Malta’s collection of prehistoric female figurines to address potential knowledge gaps rather than to create gendered separation within the collection. While projects in open knowledge ecologies, such as those operated by Wikimedia, are most often focussed on addressing the gender gap, we seek to analyse visual descriptive data to ensure that this provides opportunities for open interpretations, including for feminist points of view that have frequently been disregarded, overlooked, or completely excluded.

In recent years, a palpable shift has taken place in the art world’s general narrative and the ways museum collections are being developed. This is clearly what drives the publication of factual data by the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington D.C. to highlight gender inequity in the art world.Footnote13 This recent shift is also reflected in books that aim to re-write histories of art. For example, Katy Hessel’s book The Story of Art Without Men focuses on women artists who have often been overlooked or outrightly dismissed. In the process she provides a revised history of art from a female perspective. One which is also prominently available at major art museum bookshops in the United Kingdom, where this book was published in 2022. In an equitable society, gender data can be a powerful way to bring previously forgotten or untold stories to life, adding meaning to raise awareness about different perspectives on things that have been presented in one way for a very long time.

Nevertheless, feminist thought is not only about gender. In considering gender data we can also acknowledge the intersectionality that comes along with it, as data-driven decision making continues to shape our day-to-day realities. In 2020 a network of women involved in data science coalesced around the idea of data feminism. Their aim is to lead a cultural movement to promote equitable and gender-sensitive data systems for more inclusive decision making.Footnote14 In their work with the Data Feminism Network, Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein point out that ‘intersectional feminists have keyed us into how race, class, sexuality, ability, age, religion, geography, and more are factors that together influence each person’s experience and opportunities in the world’ (Citation2020, 14). The growing work of data feminism is therefore to uncover and renounce existing inequalities around the world through data science. This perspective guides work on the project described in this article, especially in terms of identifying gaps in the collection, and data about it, which may lead to misinformation or incomplete approaches to the interpretation of objects displayed in a museum.

Adopting practice-based research design for artistic work

With a clearer understanding of the five elements that inform this research project, we can proceed to outline our research design and methodology. In essence, this addresses questions about what we are aiming to show and how are we going to produce whatever is being shown at the end of the research project. The Naked Data installation we presented during DRHA 2022 is an example of the sort of output that is possible through this research project.

Aside from the subject of applying a feminist perspective in reimagining prehistoric female figurine we are guided by another essential question: should the data drive the visualization? Engaging with this question implies that we are mindful that data art, or any other artistic manifestation that arises out of this project, should somehow remain legible as an interpretation of the data set on which it is based.

Developing the data set: acquisition, adoption, and application

Heritage Malta’s collection of prehistoric female figurines is located at two museums: the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta and the Ġgantija Temple Park in Gozo. All the female prehistoric figurines that the organisation has are on public display and no objects are held in storage away from the permanent museum exhibition halls. The Valletta museum has twenty nine artefacts with this category, while another nine are kept in Gozo. The organisation has not published a catalogue of these objects, or a list of any sort, for public viewing. Details about these objects are held in a paper-based ledger in the senior curator’s office at the Valletta museum. There is no digital database, central or otherwise, where the data about these objects is held. The same is true for most other objects held within Heritage Malta’s collection, even if an in-house digitisation unit was established in 2021 to address the need for such approaches across all of Heritage Malta’s collections, which contain thousands of objects.Footnote15

Getting to the initial data entry stage on the female figurine collection posed its own challenges. As neither the collection nor individual objects within it already existed on Wikidata, a clean slate approach was necessary. In this way, the data gathered would be both quantitative (sizes, dates, etc.) and qualitative (given names, interpretations, etc.). Not all data properties and values are equally appropriate for visualization. Careful selection, sometimes even through trial and error, is required to ensure that required outcomes are somehow part of what is involved in the query process, without eliminating the chance of accidental discoveries. One way to ensure this is to ensure that the data is formatted consistently so that properties and values are congruent across a target data set. In some ways, this can also be perceived as data curation or curation through data.

After the initial data entry stage, Tabone started applying the data property of the material from which the objects are made by manually visualising this through Adobe Illustrator, the popular vector graphics editor used widely by visual designers. The data started showing itself in ways that are not obvious in simple textual lists. These basic visual representations of the data provided an opportunity for the data to be imagined from a creative, if not artistic, point of view, and have been included in the video art work exhibited at Stanley Picker Gallery. In Naked Data, the artist looks at the prehistoric figurines collection held by Heritage Malta and imagines that these objects have stories to tell. In this way, storytelling is seen as a possible approach to the ways the data about these individual objects and this collection as an ensemble can be visualised through artistic interpretation. Furthermore, unlike an archaeologist, an artist can take the liberty of imagining a scenario where these stories are told by women for other females to relate to one another and themselves. This in itself is part of the feminist perspective that the artist has adopted for the creative aspect of this project.

Visiting the National Museum of Archaeology in Malta in 2022 we realised how overlooked the statues, figurines and fragments we are interested in are, except for the so-called Sleeping Lady, which is placed in a small dimly lit room to be seen by itself. The Sleeping Lady was originally discovered in 1905 in the central chamber at the Ħal Saflieni Prehistoric Hypogeum, which is one of only three UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Malta. This small statute shows a woman dressed only in a long pleated skirt lying on a bed, sleeping peacefully on her right side.Footnote16 While a small number of pieces are presented in a prominent glass case in the same room as several other simular objects, the rest of the collection is presented on shelves next to each other, inside an unevenly lit glass cabinet. Unless you deliberately position yourself to take a closer look at them, they can very easily be missed during a casual visit to the museum.

Tabone worked closely with the previously unpublished data available on this specific collection at Heritage Malta. This included inventory numbers and descriptors. Although it is tempting to elaborate on alternative items or the multilingual features of the platform, in acquiring the data into the Wikidata platform, the focus was visual representations of the female body, with special attention to the choice for material from which these figurines and fragments are made. Commentary or personal interpretation are kept apart from this process of basic data capture. These can come later. They are outside the scope of the initial data capture exercise, which is mostly a transfer from the analog documents held to date by Heritage Malta. What is acquired at this stage are properties relating to self-evident representations of the female body through biological characteristics. In some cases, the figurines have previously been conventionally described as ‘fat’ or having ‘non-realistic proportions’. However, it is useful to point out that when a woman looks at her own pregnant body, she doesn’t necessarily see herself as fat or that she has uneven proportions. More recent data recorded by Heritage Malta replaces such terminology with terms like ‘corpulent.’ In this way, however, the data is also sex-disaggregated, and remains sex-disaggregated until gender justice has been achieved in the manner advocated by data feminists. This can be reflected on Wikidata, even if the platform affords new properties that are not presently held in the official records.

To better understand the formal qualities of some of these objects, Tabone chose to model some of them in clay. This was not an attempt to create replicas of the objects in the museum but rather to acquire experiential knowledge of the body forms through the physical materiality of clay. In terms of the data set, this is captured in the item property ‘depicts’, which has basic values such as body parts or physical characteristics.Footnote17 Maltese archaeologist Isabelle Vella Gregory points out that, ‘prehistoric women chose to embody in clay significant events in their lives: giving birth and possibly miscarriage. These representations also shed light on another aspect of women’s lives – the transmission of knowledge and the creation of a community feeling among women as they spoke about and shared their experiences of their lived bodies’ (Citation2005, 106). In ths way, clay is used as an early knowledge sharing medium. It is also useful to remember that the Ishango Bone, which was discovered in 1960 in the Congo, is thought to be one of the earliest pieces of evidence of prehistoric data storage. It is believed that palaeolithic tribes may have used it to keep track of trading activities and supplies. While prehistoric societies are presumed to lack written texts, recording data to share knowledge is evidently a human concern that predates written histories as passed down through the centuries.

Narrowing our attention on the physical appearance of the objects, we have also chosen to move away from the conventional ideas that have attributed terms like ‘goddess’ and interpretations of a possible matriarchal society. The physical properties cannot always be interpreted with certainty. One such element involves the red ochre pigment visible on some of figurines. How useful is it to consider this as representing menstrual blood or childbirth? Our answer is: not at all. In this data set, this information is therefore recorded as a physical characteristic rather than a property that has a potentially symbolic meaning.

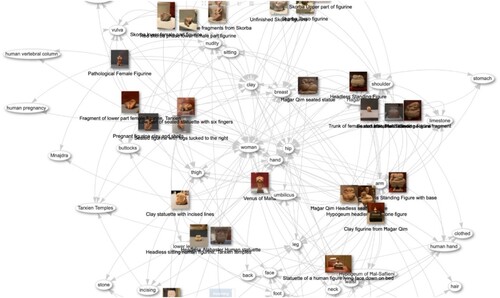

In adopting this data set for artistic application, Tabone also photographed each figurine and fragment separately. These images have all been uploaded to Wikimedia Commons and linked directly into the properties for the individual objects on Wikidata ().Footnote18 This is partly possible because the ancient objects themselves are not protected by copyright, as would be the case with more recent items held by the museum. Non-flash photography is allowed in the musuems but official photos of the museums’ collections are largely only available under copyright and therefore not widely accessible. The photographs on Wikimedia Commons, as now displayed in Wikidata, provided an instant visual aid even when simply browsing through the data set before the application of Wikidata queries and visualization tools. It is in this empirical way that feminine body forms were identified as an essential property for objects to be included in the final data set adopted for application in the Naked Data art installation.

Figure 7. Wikidata query on Heritage Malta’s prehistoric female figurines visualized as a relational knowledge graph.

Analysing visualised data has helped us see patterns that have resulted from sorting, grouping, and filtering the data set. Particularly on an open data platform like Wikidata, data sets can be altered and adapted for different visualizations. Wikidata contains data visualisation tools within it.Footnote19 These produce graphs, timelines, and other charts and diagrams. Third party tools, such as the commercial software Tableau, allow the importation of data exported from Wikidata to be visualised in 3D graphs and other data visualisation permutations. Essentialising the information in the data set, Tabone chose to use Adobe Illustrator to create visual representations of the data set as this allowed her to use her established skill set to develop a short instance of stop motion animation, imagining a new figurine arising from the data about the types of materials used for the creation of the original objects in Heritage Malta’s collection. While our primary concern in the context of this project would be artistic, this is also applicable in developing enhanced approaches to collection cataloguing. It also demonstrates the possibilities embedded in looking at a data set holistically, rather than a collection organised by title or the period in which the object was created or acquired.

The Naked Data installation created in 2022 has been shaped by the work Tabone conducted on Wikidata. The graphs generated in the process of visualising the data set gave the artist a sense of its representation that can be seen in the lower part of the plexiglass object. Similarly, the video art has been produced from the starting point afforded through the data set as visualised in a relational graph. The art is not a scientific representation of the data in the way conventional data visualisations tend to be. The data set provides an opportunity for the creation of art from a source that would otherwise not be available for an artist to explore creatively.

Conclusions

Why use data art to interpret a data set that can be visualized through conventional data visualization methods? This question enables us to evaluate Naked Data not as an isolated art installation but potentially as a model for the application of data sets in the making of new art objects. We have engaged with this data set through a creative process to learn new things about a collection of museum objects that would probably not have been possible by simply observing, replicating, or interpreting them in isolation. Data visualisation is a very useful starting point for the creation of data art. Still, data art is produced through broad range of approaches to using specific data sets as raw material for creative expression.

One of our objectives is to instigate new research opportunities not only on this data set but also on other data sets through the method we have developed. We firmly believe that there are countless other opportunities to be explored, even within the same museum or other related museums operated by the same umbrella organization. Ultimately, the way of working with Wikidata is to connect collections together through links that are either not obvious or ones that are not necessarily easy to process without the magnitude of data aggregation that is provided through this open knowledge database that can be read by both humans and machines.

With the data readily available to a broader audience, people can discover things that remain hidden in museums, often even in reserve collections where only specialists can gain access through special permissions. Opening up knowledge about cultural heritage collections can enable new audiences to look for things that are not necessarily the ones presented prominently by institutional curators. Naked data can be dressed in new ways, which in some cases may be closer in interpretation to the original contexts in which they existed. It may also deliberately fuel flights of fantasy beyond ordinary imagination.

In drawing such a conclusion, we are indebted to Nancy Duarte, who states that,

As you explore data, you’ll begin to formulate thoughts about what it’s telling you. A point of view will emerge from the deep thinking. Sometimes, what you’ve uncovered will be blatantly self-evident to everyone and based 100 percent on the data. Sometimes, you will have to use a pinch of intuition and make some assumptions. Once you’ve taken a clear stance on what you’ve found, you’re ready to construct a data point of view (49).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Toni Sant

Toni Sant is the Director of Digital Curation Lab at MediaCityUK and Associate Professor in the School of Arts, Media, and Creative Technology at the University of Salford. Between 2014 and 2020 he was the Artistic Director of Spazju Kreattiv, Malta's national centre for creativity. He has written widely about digital curation and media archaeology, starting with his book Franklin Furnace & the Spirit of the Avant Garde: A History of the Future (Intellect, 2011). Other recent books include Documenting Performance: The Context and Processes of Digital Curation and Archiving (Bloomsbury, 2017), The Spazju Kreattiv Art Collection (Fondazzjoni Kreattività, 2020), and Enrique Tabone: Catalogue Raisonné (Kite Group, 2023). In 2021 he was awarded the National Book Prize of Malta for literary non-fiction for a book of Facebook posts called Jien-Noti-Jien (Klabb Kotba Maltin, 2020), which he co-authored with EU Literature Prize winner Immanuel Mifsud during the first Covid pandemic lockdown. He is also an Associate Editor of the International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media.

Enrique Tabone

Enrique Tabone is a UK-based multidisciplinary artist and designer, whose works have been exhibited in the UK, Malta, Germany, China, Turkey, and Italy. She also produces collections of wearable art through the QUEstijl brand, of which she is the founder. Both lines of creative work are the subject of Toni Sant's book Enrique Tabone: Catalogue Raisonné (Kite Group, 2023). She has recently completed a postgraduate research degree in Digital Curation at the University of Salford, where she works as a data scientist with the Digital Curation Lab at MediaCityUK and teaches contemporary art practices. Red Leaf (2013), a metal seating sculpture she was commissioned to create, is permanently installed at the Verdala Sculpture Garden in Buskett, the official summer residence of the President of Malta. Her large-scale work Naħla (2017) was included in the third edition of VIVA – the Valletta International Visual Arts festival at Spazju Kreattiv; parts of this work now form part of Fondazzjoni Kreattività’s permanent collection, which is a substantial part of the modern and contemporary section of the National Art Collection of Malta. Her art can be viewed at http://www.enriquetabone.com

Notes

1 For more on Art+Feminism see https://artandfeminism.org accessed 22 October 2022

2 See, for example, Soffer, Olga, James M. Adovasio, and David C. Hyland. “The ‘Venus’ Figurines: Textiles, Basketry, Gender, and Status in the Upper Paleolithic.” Current Anthropology 41.4 (2000): 511–537, and Dixson, Alan F., and Barnaby J. Dixson. “Venus Figurines of the European Paleolithic: Symbols of Fertility or Attractiveness?” Journal of Anthropology 2011 (2011).

3 See also the Wikidata item at https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q113407294

4 See for example: Trump, David H. Malta: Prehistory and Temples. Malta: Midsea Books, 2002. Esp. pages 88, 95 and 103. Another recent example engagins with such rhetoric can be found in Johnson RJ, et al. “Upper Paleolithic Figurines Showing Women with Obesity may Represent Survival Symbols of Climatic Change”. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021 Jan; 29(1):11–15.

5 From the Open Knowledge Foundation’s Open Definition 2.1 available at https://opendefinition.org/od/2.1/en/ accessed on 22 October 2022.

6 See https://okfn.org accessed 22 October 2022.

7 Wikidata has been available at http://www.wikidata.org since 2012.

8 For a current list of visualization tools on Wikidata see https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Wikidata:Tools/Visualize_data accessed 22 October 2022.

9 See https://openartbrowser.org accessed on 22 October 2022.

10 See http://histropedia.com/timeline/ accessed 22 October 2022

11 Cited in Abigail Edge’s “Data visualisation tips from Information is Beautiful” available at https://www.journalism.co.uk/news/data-visualisation-tips-from-information-is-beautiful/s2/a565043/ accessed on 23 October 2022.

12 See this artist’s website at https://www.nathaliemiebach.com accessed 23 October 2022.

13 The NMWA’s factual datat is available at https://nmwa.org/support/advocacy/get-facts/ accessed on 23 October 2023.

14 See the Data Feminism Network website available at https://www.datafeminismnetwork.org accessed 23 October 2022.

15 Heritage Malta’s Digitisation Unit was officially launched in June 2021 with a major project on the collections of Malta’s National Maritime Museum. See https://newsbook.com.mt/en/heritage-malta-set-up-new-unit-to-digitise-heritage-assets/ access 30 April 2023.

16 See also the Wikidata item at https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q1809373

17 See the Wikidata property details at https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Property:P180

18 You can interact with the data visualisation generated through Wikidata SPARQL Query: https://w.wiki/6Cvb

19 See https://query.wikidata.org

References

- D’Ignazio, Catherine, and Lauren F. Klein. 2020. Data Feminism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Frick, Laurie. 2015. “Personal data beginning to feel less sinister” available at https://www.lauriefrick.com/blog/data_less_sinister accessed 22 October 2022.

- Gimbutas, Marija. 1974. The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe, 7000 to 3500 BC: Myths, Legends and Cult Images. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Lupi, Giorgia. 2017. “Data Humanism: The Revolutionary Future of Data Visualization”. Print Magazine, 30 January 2017. Available at https://www.printmag.com/article/data-humanism-future-of-data-visualization/ accessed 22 October 2022.

- McCoid, Catherine, and LeRoy. McDermott. 1996. “Toward Decolonizing Gender: Female Vision in the Upper Paleolithic” American Anthropologist 98. doi:10.1525/aa.1996.98.2.02a00080.

- Vella, N. 2007. “From Cabiri to Goddess.” In Cult in Context, edited by D. Borrowclough, and C. Malone, 61–77. Oxford: Oxbow Books).

- Vella Gregory, Isabelle. 2005. The Human Form in Neolithic Malta. Malta: Midsea Books.

- Wilkinson, M., M. Dumontier, I. Aalbersberg, et al. 2016. “The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship.” Scientific Data 3: 160018. doi:10.1038/sdata.2016.18.