Foreword

Almost two years ago, Bruce Gill (Biodiversity’s Editor-in-Chief) and I received an intriguing email from a Dr. Chet Trivedy. Chet was inquiring whether we might be interested in publishing a themed issue dedicated to ‘One Health and Conservation’. I must confess, at first, I wasn’t entirely sure what One Health meant – although if I had had to hazard a guess, I would have assumed it related to the interdependence between human and biological life. I had never heard the term before, so naturally I was interested to find out more. After a lively, fascinating call with Chet, I was hooked on the idea and we proceeded with pulling content together. Having spent the past year reading and editing the submissions, I believe this themed issue of Biodiversity reveals the tip of the iceberg for the importance of a One Health approach to conservation. My thanks go to Chet for his continual dedication to this field of work, and to all those who are bringing the One Health agenda to the public and scientific community.

Vanessa Reid

Biodiversity’s Managing Editor

The Rubik’s Cube and One Health

The Rubik’s Cube is a three-dimensional puzzle invented by the Hungarian scientist Ernő Rubik, which was all the rage in the 1980s (Adams Citation2009). The objective was to navigate a cube with six faces, where each face comprised nine smaller blocks – each bearing a specific colour – and was to be completed by aligning all the faces of the cube in terms of their respective coloured blocks. The blocks could be moved in different planes, but often solving the puzzle for one face resulted in the disruption of the pattern on another face. This meant that the user had to focus on what was happening on all six faces of the cube at the same time, whilst simultaneously attempting to manoeuvre the cube in different planes.

The One Health approach can be seen as such a puzzle, where each face of the cube represents a distinct area or discipline that often has a crucial impact on the overall health and well-being of a natural system. Now, imagine each of these disciplines, some of them with competing interests, working independently to solve the puzzle with their attention focussed on a single aspect of the cube … and you may begin to get a better understanding of the complexities surrounding the challenges facing One Health. Before I share my interpretation of the key disciplines involved in One Heath, their impact on the conservation of wildlife and the challenges facing conservation, and then discuss potential strategies to solve the elusive One Health puzzle, I’d like to take a moment to share how I came to One Health and how it underpins everything I do today as a researcher and health practitioner who is actively involved with conservation work in India.

I was first introduced to the concept of One Health four years ago, when I started working with the Wildlife Conservation Trust (Mumbai) and spent a lot of time with forest guards (wildlife rangers) in tiger reserves in central India. It soon became evident that issues such as malaria, trauma and injuries, cardiovascular disease and psychological health were important health issues in this demographic. At the time I had heard of the concept of One Health but felt that its narrow focus on the spread of zoonotic diseases meant that some of the other health issues which we had observed were technically outside the scope of the One Health definition. It then dawned on me that One Health is about much more than the transmission of zoonotic diseases, and that a number of other factors play an important role in the complex relationship between human health, animal health and the environment. It is the quest to bring these issues to the forefront of the One Health debate that has been the inspiration for this special issue, thereby providing a more inclusive and holistic approach to safeguarding our health as well that of our environment and its biodiversity.

What is One Health?

The term ‘One Health’ has been broadly defined as a multidisciplinary approach to securing the health of humans, animals and the environment. The origin of the term can be traced to the nineteenth-century German physician, anthropologist and ‘father of modern pathology’ Rudolf Virchow. He proposed the interdependent relationship between human and animal health. It is important to appreciate that the concept of One Health is not new, and has long been central to the worldviews of many indigenous cultures, such as the North American Indians, the aboriginal peoples of Australia and even aspects of Ayurvedic medicine have placed great emphasis on nature and health. However, the modern concept gained popularity in 2004, following a conference hosted by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) (Cook, Karesh, and Osofsky Citation2004). Since then, the discipline of One Health has largely focussed around the surveillance and transmission of zoonoses between livestock, wildlife and humans, by those practicing veterinary medicine or physicians specializing in infectious diseases or public health (WHO Citation2017; CDC Citation2018). Many organizations have tried to define One Health, with each choosing a slightly different perspective on what One Health is. This brings us back to our Rubik’s Cube analogy of One Health, where each face of the cube represents a unique discipline that is often working independently of other disciplines. By bringing together a diverse, multidisciplinary group of stakeholders, there are greater chances of averting future pandemics, mass extinctions, irreversible impact of climate change and loss of our natural environment. However, to do this we have to look deeper into some key issues that underpin the concept of One Health and accept that the health of humans, animals and the environment is not only complex but also driven by social science, economics and politics. We must also look outside the health-related specialties when discussing the concept of One Health. In my own professional experience, I have noticed that these areas of the One Health approach have been largely overlooked, making One Health solutions harder to achieve.

The six faces of the One Health puzzle

Animal health

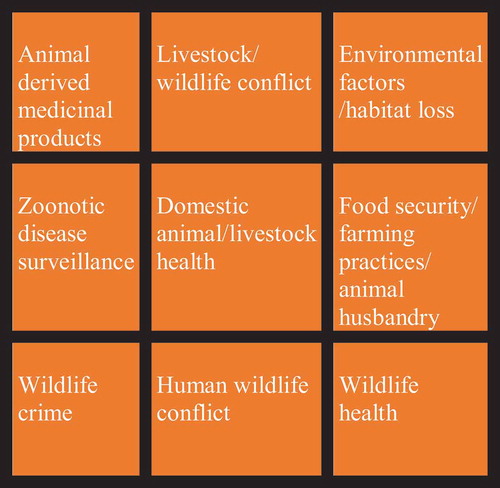

Animal health is a central component of One Health, with traditional One Health initiatives being focussed on gleaning a better understanding whilst attempting to mitigate the transmission of zoonotic diseases between animals (specifically vertebrates) and humans. Factors such as the presence and release of pathogens from the reservoir of infection through excretion of a virus, or from the slaughter of infected animals, and the survival of the pathogen in infected meat or infection of a vector will lead to infections in humans, resulting in human-to-human spread. In the case of COVID-19, some theories propose that the virus may have originated in animal hosts, such as bats or pangolins, and disseminated through wet markets in Wuhan. The jury is still out, however, and there is still a degree of uncertainty regarding the origin of COVID-19 (Mallapaty Citation2020). It is also important to clarify that within the context of animal health, One Health should not just be about zoonoses. Issues such as the global consumption of meat and the dairy industry may have a significant impact on the environment through the emission of greenhouse gasses, thereby impacting environmental health as well promoting deforestation to create space for grazing and farming (Rust et al. Citation2020). This may also contribute to human–wildlife conflict, where livestock can graze in protected conservation areas, allowing the spread of diseases such as foot and mouth disease (FMD) from cattle to other wild ungulates (Weaver et al. Citation2013). It is therefore imperative that we look at the broader role of animal health in the One Health context and consider wider issues such as the access to and affordability of veterinary care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). I believe we also need to understand how the consumption of animal products (meat/dairy/poultry/fish), either through extensive farming or through the bushmeat trade, in some contexts has the potential to have a major One Health impact on both human and environmental health, due to a host of possible underlying reasons (highlighted in ).

Human health

As humans are the domineering species on the planet, human health must be seen as the flagstone or centre piece for any One Health approach. Studies have shown that over 75% of new, emerging human infections are zoonotic in origin, spread from other vertebrate animals to humans (Bidaisee and Macpherson Citation2014). We have already witnessed a number of viral infections spreading from animals to humans, such as HIV, Ebola, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), H5N1 (avian flu), H1N1 (swine flu), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and more recently COVID-19 (Plowright et al. Citation2017). What these infections have in common is that the virus spilled over from an animal vector to human, through either close contact with infected livestock or the consumption of contaminated meat/bushmeat (Cantlay, Ingram, and Meredith Citation2017). Although the impacts of zoonotic diseases have been the central interest of One Health, other areas may be worthy of mention or inclusion as part of the One Health concept, as they may in themselves – despite having been overlooked by One Health forums – also contribute to the burden of outbreaks such as the current pandemic.

Food security can be defined as ‘having sustainable and affordable access to nutritious food’ and is a central theme in One Health. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1.9 billion people across the world are obese, whereas 462 million people are underweight (WHO Citation2020), suggesting that nutrition and related disorders are either due to malnutrition or illnesses arising from overnutrition, such as obesity. Cardiovascular diseases, which are linked to dietary intake, may also be classed as legitimate parts of the One Health ideology. There is also a case for other medical conditions, such as psychological health, trauma and injuries and maternal health, playing important and yet poorly understood roles in One Health, particularly at the human–wildlife interface in LMIC settings. In addition to a lack of access to affordable healthcare in these areas, there may be a reliance on traditional remedies, many of which involve the use of animal products, such as rhino horns and tiger products. This of course facilitates illegal wildlife crime and trafficking of wild animals, which further increases the risk of spillover of any viruses from animals such as bats or pangolins, as has been proposed for SARS-CoV-2 as a potential origin for COVID-19 (Mallapaty Citation2020) ().

The conservation of wildlife and ecosystems

There is some evidence that COVID-19 may have originated in wet markets in the Wuhan Province of China, through viral spillover from either a bat or a pangolin. In fact, significant amounts of animal products such as rhino horns, tiger bone glues, bear bile and pangolin scales often end up trafficked to these illegal markets, where they are sold for use in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), even though there is little evidence for their efficacy (Guynup Citation2017; Bale Citation2019; Fobar Citation2020). However, the WHO’s inclusion of a chapter on TCM in the International Classification of Disease (ICD-11) may be viewed by some as legitimizing TCM, thereby fueling the illegal wildlife trade and risking further outbreaks due to the spillover of viruses between wildlife and humans (Nature News Citation2019; WHO Citation2019). Given this high demand, and the alleged medical benefits of these endangered animal products, there is a compelling argument for putting the illegal wildlife trade at the heart of the One Health puzzle.

The term ‘poaching’ is widely used to describe those accused of heinous crimes against defenseless creatures, whilst we use the term ‘trophy hunter’ to describe those who can afford to hunt for sport. However, the origin of the term ‘poaching’ refers to land rights and illegal hunting without permission of the landowner. Ironically, some of the illegal activity conservation groups now deem as poaching is often carried out by indigenous tribes and people who once sustainably lived and hunted in the same areas – often their sacred, ancestral lands – from which they were evicted for conservation purposes. These evictions were carried out by the same people who had previously hunted many of the species they are now seeking to protect, to the point of extinction. I do not support this, but I believe that we need to look deeper at the socio-economic, historical and cultural issues that underlie some of the concerns around illegal wildlife crime. Issues such as poverty and social and cultural expectations, coupled with the loss of livelihoods of indigenous communities, may leave some with no option but to engage in illegal activities such as hunting for bushmeat (Duffy et al. Citation2015). Hunting and the consumption of bushmeat in itself provides another risk factor for zoonotic disease transmission. It is also a sad truth that many people living around protected areas will not be able to afford to pay for the luxury of a package safari on their own doorstep, yet we are encouraging them to conserve their wildlife, to motivate greater stewardship of the environment and wildlife, as well as reducing the risk of zoonotic spillover.

It is essential that we support these communities so they will have access to sustainable livelihood options, education and training as well the ability to appreciate and profit from their environment. I believe this will help empower them to adopt more conservation-focussed activities, where they can have greater control over how local wildlife is managed and ultimately make the conservation of wildlife more sustainable. Initiatives such as homestays have been used with success in Ladakh for snow leopard conservation (Balasubramanian Citation2018); however, it is important that local communities are not just seen as commodities for tourists but given a greater role in developing practical and sustainable relationships between humans and wildlife. A more controversial approach suggested by some conservationists is to use legalized trophy hunting to generate an income, which can then be used to support local communities. Having heard the arguments from those who support this intervention, I remain unconvinced that trophy hunting is either an ethical solution for wildlife management or a sustainable solution for the local communities involved.

The several years I’ve spent working with wildlife rangers in tiger reserves, mainly in Central India, have given me an insight into the One Health complexities facing those on the front lines of wildlife conservation. These forest guards are tasked with preventing poaching and other wildlife crimes, and their physical and psychological health is central to the success of conservation policies in India. Failure to acknowledge their role and the challenges they face in the field, as well as wildlife and forest guards all around the world, is likely to have significant negative impacts on One Health strategies ().

Social determinants of One Health

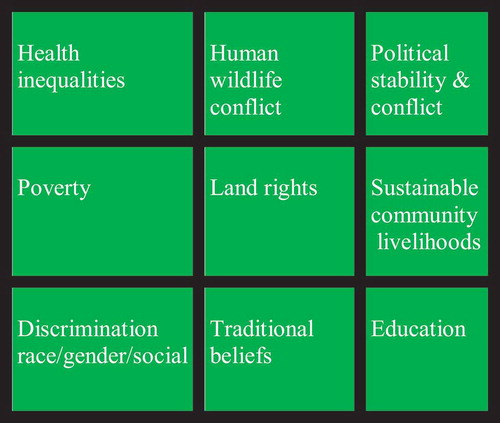

This area may be the most underrated aspect of One Health, as it overlooks critical issues such as poverty, human rights and even historical issues around racial discrimination. This includes the colonial legacy around conservation policies that often focus on protecting wildlife at the expense of local indigenous communities in LMICs. These inequalities, including loss of land rights and dependency on traditional livelihoods, may have a significant impact on the One Health model. Empowering local communities to engage in sustainable pro-conservation activities that provide tangible returns, such as an income, food and water security, housing, education and access to health, may increase the One Health stewardship in these communities.

Another factor is the devastating impact of political instability and conflict on One Health. An example of this can be seen in the conflicts of the Rwanda Genocide, which resulted in a massive cost to human lives, displacement of populations and a significant threat to primate conservation (Rosen Citation2014). This is just one example of how political instability can have far-reaching One Health consequences.

It is imperative that urgent steps are taken to address these social inequalities and that we ultimately restore social injustice to make a positive impact on One Health outcomes ().

Economic considerations

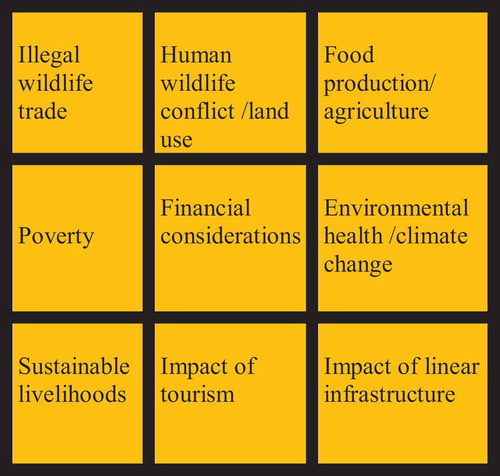

Economic considerations are a powerful driver for the displacement of natural ecosystems and landscapes from land that can be used for agriculture, farming and food production. The exponentially increasing food production needed to feed almost eight billion people has had an undeniable myriad of direct and indirect disastrous effects on the environment, such as the destruction of forests for agriculture and the commercialization of protected areas for logging and mining (Nunez, Citation2019). This increased need for productivity and infrastructure has also resulted in the significant expansion of road and rail networks in what were formerly conservation areas. This results in the loss of natural habitats, many of which were already threatened, as well as driving the endless urbanization of rural areas. Combined, these factors increase human–wildlife conflict, which in turn affects animal health through contact with humans as well as livestock, which then pass zoonotic infections to wild animals. We have only to consider the trade in ivory or rhino horn and the multimillion-dollar industry behind it to appreciate the crucial links between wildlife crime, finances and the economic drivers for One Health. It is an unfair situation, and an even more unfair truth, that – more than likely – the poacher responsible for killing an elephant, rhino or a tiger is a member of the indigenous community who may get only a fraction of the final retail price for risking their lives to obtain a highly valued product, which is then sold by middlemen to wealthy buyers. Although wildlife crime is unpalatable and, in an ultimate sense, wreaks havoc on our planet’s already threatened and near-extinct species, it is essential to examine and scrutinize the factors that have driven many of these individuals and communities to turn to poaching in the first place; and, in this process, to develop constructive interventions – relevant to the specific cultural, religious and socio-economic context in question – that offer alternative livelihoods. These must include benefits from protecting wildlife and from engaging local communities with tourism through initiatives such as eco-tourism and home stays – examples where communities can benefit directly from tourism. At the same time, we have to look at what is driving end users to pay so much for these products, so that interventions can be developed to reduce the demand. There is a tendency to militarize the war against poaching and to kill would-be ‘poachers’. Although this may address the short-term problem, it can create several additional burdens, such as the loss of the family breadwinner, and push families further into poverty. We need to adopt a prevention strategy by looking at steps to reduce the demand for products, through education, cultural change or making wildlife more profitable for the local communities () (Hübschle, Citation2018). This is no doubt a complex problem for conservation where there is a fragile balance between the need to protect wildlife whilst meeting the needs of the local communities. Some of these issues within the context of the African landscape are discussed in more depth in a report published by the Global Initiative against Translational Organized Crime.

Environmental health

There can be no doubt that human beings have had a major impact on the health of the natural world, and there is sound, and – I would argue – indisputable evidence that further demonstrates the detrimental impact of climate change on the planet. Even the Gaia hypothesis proposed by the chemist James Lovelock, that draws on a crucial synergy between living organisms and their inorganic environment through ‘geophysiology’ (Levine Citation1993), resonates strongly with my concept of One Health. Examples such as accumulated human-produced microplastics in our oceans finding their way back into the human chain are stark reminders of the impact of environmental as well as human health – and it has been estimated that by 2050 there will be more plastic than fish in the sea (Karbalaei et al. Citation2018; Conservation International Citation2020). Ironically, during the global lockdown of industries during the COVID-19 pandemic, global pollution levels dropped significantly due to the reduction in industrial activity and reduced use of road networks (Hernandez Citation2020). However, these effects are likely to be transient as the lockdown eases, and as an upsurge in industrial activity has already begun. The steady drive for modernization around protected areas not only disturbs crucial wildlife corridors that are essential to maintain the genetic diversity of many species but also increases the opportunity for human–wildlife conflict, with loss of human lives as well as retaliatory actions against wildlife. The list of environmental impacts of One Health could be the subject of a whole issue itself; there are too many examples to mention here. One of the biggest challenges of environmental health is safeguarding the environment whilst meeting the needs of rural LMIC populations who, like those living in countries of the Global North, also expect to have access to luxuries and amenities such as electricity, running water and the internet: things that are afforded to those living in affluent areas. To me, it screams of double standards, if not outright hypocrisy, for countries who have already traded their forests and wildlife in the name of progress to deny others – who live in these natural places – the same privileges ().

Call for action

Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic have been eye-opening for me on a personal level, and have deeply affected my research around One Health; it is a vital issue that not only needs to be urgently addressed, but also is more complex than just addressing human, animal and environmental health issues.

One of the greatest challenges One Health faces is around identity and ownership. This has also been reflected in the scope of the research in this issue, in that it is primarily from the Central Indian landscape. This may appear to be editorial bias, but the reality is far from that. Despite numerous attempts to reach out to conservation researchers as well as veterinary and human healthcare professionals from other countries to submit their work for this special issue, there were few submissions related to this call which was specific to One Health and conservation.

In my opinion, many conservation researchers do not identify their work with the One Health concept because they either do not work in the health sector or do not have an interest in zoonotic diseases. I have even experienced a touch of imposter syndrome writing this, as I don’t have formal training in conservation or specialize in zoonotic diseases. However, I have spent a considerable amount of time in the field, with first-hand experience of the health challenges facing wildlife and humans alike in conservation areas, and I have developed a number of initiatives to support conservation using a One Health approach. I believe that by restricting One Health research to human health or animal health or zoonoses, there is a risk that vital and much-needed work around the other, lesser known disciplines of One Health will continue to be overlooked. The aim of this themed issue is to raise awareness around the broader concepts of One Health and encourage engagement from a wider range of researchers who may traditionally not see themselves as ‘One Health practitioners’. Coming back to the Rubik’s cube puzzle, like all challenges there are solutions to be found here. Working collaboratively and paying attention to the different facets of the One Health puzzle, we may not only mitigate against future pandemics but also secure the future of our natural environment and its rich biodiversity.

***

I would like to conclude the Editor’s Corner by offering the readers my own definition of One Health.

One Health can be defined as a model that hosts the deep and complex inter relationships between the health of humans, animals and the natural environment. One Health is dependent upon a number of key drivers such as socio-political factors, economic considerations, conservation of our biodiversity, environmental health, veterinary and human healthcare systems. The interdependence between these factors is central to maintaining our bio-security and sustainable co-existence on earth. One of the greatest challenges for One Health is the acceptance of the fact that One Health is not just about zoonotic diseases or our health but has strands which are entwined within the very fabric of our society and it is this that will shape the nature of our future existence on this planet.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chet Trivedy

Dr Chet Trivedy, BDS FDS RCS (Eng) MBBS PhD FRCEM FRGS, is an emergency physician and an academic based in the UK. He founded the Tulsi Foundation in 2015: a voluntary organization that focusses on the delivery of healthcare to forest guards (rangers). He has been working with the Wildlife Conservation Trust (Mumbai), India, to develop practical and sustainable One Health solutions in tiger reserves in the central Indian landscape. He has also worked with the Borneo Nature Foundation and is committed to placing health at the heart of conservation work. He is also a children’s book author and has written a book about conservation and health for young children.

References

- Adams, W. L. 2009. “The Rubik’s Cube: A Puzzling Success.” The Rubik’s Cube: A Puzzling Success - TIME. https://web.archive.org/web/20090201200141/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1874509,00.html

- Balasubramanian, S. 2018. “Snow Leopard Conservation Brings Socioeconomic Benefits to Rumbak Village.” Village Square. https://www.villagesquare.in/2018/02/16/snow-leopard-conservation-brings-socioeconomic-benefits-rumbak-village/

- Bale, R. 2019. “Pangolin Scale Medicines No Longer Covered by Chinese Insurance.” National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/animals/2019/08/pangolin-scale-medicines-no-longer-covered-chinese-insurance

- Bidaisee, S., and C. N. L. Macpherson. 2014. “Zoonoses and One Health: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Parasitology Research 2014: 1–8. doi:10.1155/2014/874345.

- Cantlay, J. C., D. J. Ingram, and A. L. Meredith. 2017. “A Review of Zoonotic Infection Risks Associated with the Wild Meat Trade in Malaysia.” EcoHealth 14 (2): 361–388. doi:10.1007/s10393-017-1229-x.

- CDC. 2018. “One Health Basics.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/index.html

- Conservation International. 2020. “Ocean Pollution: 11 Facts You Need to Know.” Ocean Pollution - 11 Facts You Need to Know. Accessed 2 July. https://www.conservation.org/stories/ocean-pollution-11-facts-you-need-to-know

- Cook, R. A., W. B. Karesh, and S. A. Osofsky. 2004. “29th September 2004, the Rockefeller University, Caspary Auditorium.” In 29 September 2004 Symposium. New York, USA: Wildlife Conservation Society. Accessed 1 July. http://www.oneworldonehealth.org/sept2004/owoh_sept04.html

- Duffy, R., F. A. V. St John, B. Büscher, and D. Brockington. 2015. “Toward a New Understanding of the Links between Poverty and Illegal Wildlife Hunting.” Conservation Biology 30 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1111/cobi.12622.

- Fobar, R. 2020. “China Promotes Bear Bile as Coronavirus Treatment, Alarming Wildlife Advocates.” National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/2020/03/chinese-government-promotes-bear-bile-as-coronavirus-covid19-treatment/

- Guynup, S. 2017. “Tigers in Traditional Chinese Medicine: A Universal Apothecary.” National Geographic Society Newsroom. https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2014/04/29/tigers-in-traditional-chinese-medicine-a-universal-apothecary/

- Hernandez, M. 2020. “This Is the Effect Coronavirus Has Had on Air Pollution All across the World.” World Economic Forum. Accessed 2 July. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-covid19-air-pollution-enviroment-nature-lockdown

- Hübschle, A. 2018. “Ending Wildlife Trafficking”. Global Initiative. https://globalinitiative.net/ending-wildlife-trafficking/

- Karbalaei, S., P. Hanachi, T. R. Walker, and M. Cole. 2018. “Occurrence, Sources, Human Health Impacts and Mitigation of Microplastic Pollution.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 25 (36): 36046–36063. doi:10.1007/s11356-018-3508-7.

- Levine, L. 1993. “GAIA: Goddess and Idea.” Biosystems 31 (2–3): 85–92. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(93)90035-b.

- Mallapaty, S. 2020. “Animal Source of the Coronavirus Continues to Elude Scientists.” Nature News. Nature Publishing Group. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01449-8

- Nature News. 2019. “The World Health Organization’s Decision about Traditional Chinese Medicine Could Backfire.” Nature News. Nature Publishing Group. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01726-1

- Nunez, C. 2019. “Deforestation and Its Effect on the Planet.” Deforestation Facts and Information. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/global-warming/deforestation/

- Plowright, R. K., C. R. Parrish, H. Mccallum, P. J. Hudson, A. I. Ko, A. L. Graham, and J. O. Lloyd-Smith. 2017. “Pathways to Zoonotic Spillover.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 15 (8): 502–510. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2017.45.

- Rosen, J. W. 2014. “The Battle for Africa’s Oldest National Park.” The Battle for Virunga, Africa’s Oldest National Park. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/special-features/2014/06/140606-gorillas-congo-virunga-national-park/

- Rust, N. A., L. Ridding, C. Ward, B. Clark, L. Kehoe, M. Dora, M. J. Whittingham, et al. 2020. “How to Transition to Reduced-Meat Diets that Benefit People and the Planet.” Science of the Total Environment 718: 137208. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137208.

- Weaver, G. V., J. Domenech, A. R. Thiermann, and W. B. Karesh. 2013. “‘Foot And Mouth Disease: A Look From The Wild Side.” Journal of Wildlife Diseases 49 (4): 759–785. doi:10.7589/2012-11-276.

- WHO. 2017. “One Health.” World Health Organization. Accessed 2 July. https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/one-health

- WHO. 2019. “International Classification of Diseases −11.” World Health Organization. https://icd.who.int/en

- WHO. 2020. “Fact Sheets - Malnutrition.” World Health Organization. Accessed 2 July. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition