ABSTRACT

This research is interested in the history of three tourist towns along the coast of Manche Deauville, Dieppe, and Le Touquet-Paris-Plage, which are amongst the stations closest to the capital and the historic cradle of sport, England. The thesis states that sport is an indispensable part of the ‘Habiter’ bathing from the Second Empire to the Second World War. The latter participates in an essential way in the appropriation of the seaside. Urban development, the construction of equipment, the dynamism of practices and the evolution of sports shows are analyzed using the scientific literature and various archival documents to illustrate the importance of sport in the definition of the Habiter des villégiateurs.

RÉSUMÉ

Cette recherche s’intéresse à l’histoire de trois villes touristiques alignées sur la côte de la Manche Deauville, Dieppe et le Touquet-Paris-Plage et qui sont parmi les stations les plus proches de la capitale et du berceau historique du sport l’Angleterre. La thèse formule que le sport constitue un élément indispensable de l’« Habiter » balnéaire du Second Empire à la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Celui-ci participe de façon essentielle à l’appropriation du bord de mer. Les aménagements urbains, la construction des équipements, le dynamisme des pratiques et l’évolution des spectacles sportifs analysés à partir de la littérature scientifique et de divers documents d’archives montrent l’importance du sport dans la définition de l’Habiter des villégiateurs.

Introduction

Seaside resorts appear on the French coastline during the nineteenth century (Boyer, Citation2005; Corbin, Citation1995; Pic, Citation2009; Viard, Pottier, & Urbain, Citation2002). Based on the English model, they are the product of collaboration between local stakeholders and ‘cultural entrepreneurs of a change of scenery’ (Andrieux & Harismendy, Citation2011). In a social and cultural context, favourable to the desire for the shore (Corbin, Citation1988), these initiatives are the successive results of aspirations related to the medicalization of the sea, the rapid increase in bathing establishments and the development of leisure activities and sports. Like spa towns, resorts, dedicated to high-society leisure, meet the needs and expectations of the ‘leisure class’ (Veblen, Citation1899/1970). To make their project viable, the stakeholders in tourism (politicians, business men) invest in, equip, bring life to and promote their territory through leisure activities and sports, all actions that can be defined as a seaside transformation process (Penel, Pécout, & Machemehl, Citation2016). From this voluntarist approach, which appears as a constant in the history of seaside resorts, stems major mutations on a spatial level (creating recreational areas) and on a social and cultural level (inhabiting and living in recreational areas). From ‘isolated territory’, seaside areas become urbanized and modernized, and through sports become recreational (Pécout & Birot, Citation2008).

Therefore, the question of inhabiting them as a ‘way of making use of space’ can be asked (Lazzarotti, Citation2006; Stock, Citation2007). How do you create this seaside area where leisure activities constitute a style of living? Who are the designers of these sports entertainment towns? For what uses and according to which investments of space? We hypothesize that recreational sports constitute a vital and even indispensable element of seaside ‘Living’. It participates in an essential way to this specific form of appropriation of the seafront. The invented logics of practice and uses of space crystallize in a seaside model, which lasts, evolves and spreads (Duhamel, Citation2015). The sports offer, in terms of practices, events and facilities, is an integral part of the economic project for seaside resorts. It integrates the daily life of its inhabitants and participates in the creation of an imagined life that iconographical sources reflect: travel advertisements, post cards, drawings and paintings. In this respect, the invented recreational sport structures space (construction of facilities) and shapes seaside life by imposing ways of doing and ways of practising for temporary residents. A distinction is made here between the beach spirit defined by being with your own kind, where you see and look at each other, and that of tourists who, through their itinerary are looking for the opposite, getting away from the familiar and discovering something else (Marec, Daviet, Garnier, Laspougeas, & Quellien, Citation2015, p. 495).

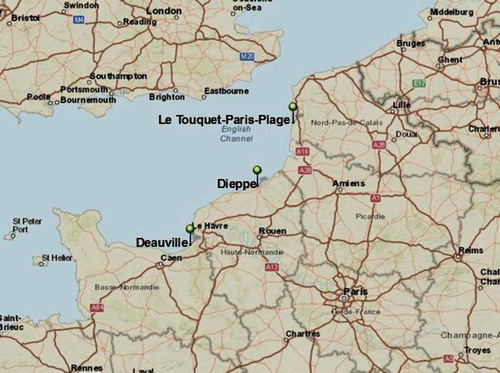

We will base our analysis on three towns: Dieppe, Deauville and Le Touquet. We take into consideration the period from the Second Empire to the 1930s, that is to say, from the appearance of the first stations (Dieppe) to the beginning of the popularization of seaside tourism. Asking yourself questions about the birth of seaside resorts enables you to envisage a style of living practised by tourists, based on breaking away from the everyday, that is a matter of social and cultural construction of places for which the meaning is in keeping with particular conditions.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Dieppe, pioneer in seaside resorts in France, is transformed into host venue for wealthy holidaymakers, and it is soon followed by Deauville and Le Touquet, built at the beginning of the 1860s. Basing their economic development model on tourism, these last two villages are structurally transformed. In addition to the technical transformations (electric connection, public lighting, drinking water, etc.), structuring facilities are also built (station, port, hotels, airport) and many infrastructures dedicated to leisure are installed: casinos, racecourses, golf course, tennis courts, etc. From this predominance of investments in ‘recreational sports’ a reputation for sports, a true tourist identity markerFootnote1 (Rieucau & Lageiste, Citation2006) is born, but a way of using these places, giving them meaning and using space also appears. Through these chronological mileposts, the notion of sports living can be learned and analysed in relation to the practices of the ‘leisure class’ before the rise of mass tourism and mass sports that generate new forms of living (Stock, Citation2015).

Our methodological approach is based, first of all, on the literature comprised of monographs and reference studies on the seaside resort phenomenon since the nineteenth century. It consists of showing the role of sports amenities in the urbanization of seaside areas. Next, the analysis is based on a corpus of various types of archives taken from the bottom of local archives: Calvados and Seine-Maritime departmental archives, local archives (Deauville, Le Touquet). Our first source is the local and seaside press. Reading it provides an understanding of the reality of recreational sports because it unfolds the resort’s sports calendar, relates the major events, the places of practice as well as the new facilities that are available. This first source is completed by reading the municipal decisions that enable us to understand the role of the local stakeholders as well as their choice in the logics of development. Finally, it seemed pertinent to study iconographical sources such as travel advertisements and post cards which, as the first communication tools of these resorts, reflect the issues of images on which their reputation is built. In fact, all these sources make it possible to identify how seaside resorts, based on recreational sports, reflect the ways of practising and participating in sports events that in the end, define modes of living.

Creating seaside resorts

Originally, Dieppe is a small town with economic activities based on the tobacco and maritime industries. It is not until the construction of its bathing establishment in 1822 by Count de Brancas, sub-prefect of Dieppe that the town becomes a place of high-society holidays and turns to tourism. To launch the resort, he manages to convince Duchess de Berry (Bertho-Lavenir, Citation1999), mother-in-law of the King of France, Charles X to come. Presented as ‘patron saint’ of the town, she spends holidays there regularly between 1824 and 1829 (Desert, Citation1983) bringing along her entourage of Parisian upper class. By investing in the beach and the sea, Dieppe is transformed into a resort for the classy world and the aristocracy. This is why there are incessant efforts to develop a loyal clientele, notably the clientele from nearby England (Pakenham, Citation1971). As we will see, this is done through investments in the creation of recreational facilities (theatre, casino, racecourse) because as of the 1880s the trend of baths increases, generating competitionFootnote2 with the other ‘ultra-chic holidays’ which Deauville and Le Touquet-Paris-Plage make their speciality.

However, the example of these last two places differs from Dieppe because their creation is the work of important figures who ‘fabricate’ a seaside resort intended exclusively for leisure and sports, ex nihilo. Although Deauville is chronologically ahead of Le Touquet in terms of its creation, the process itself is similar. Parisian investors first purchase unexploited land, most often dunes and warrens,Footnote3 then sell them by lot for the building of villas and hotels (Cueile, Citation2004). In Deauville, the group of investors is comprised of Joseph Ollife, a physician at the English embassy and main shareholder in the Trouville casino (Deauville’s neighbouring town), Armand Donon, a bank director and the Duc de Morny, deputy and half-brother of Emperor Napoleon III (Barjot, Anceau, & Stoskopf, Citation2010). In December 1859, Donon and Olliffe offer to buy 240 ha of seafront property and a spring for 800,000 francs (approximately 2.4 million euros in 2014). The seaside newspaper La Plage of 29 July 1860 is already enthused over this gigantic project:

A new town will be built on the vast stretch of land located on the other side of La Touques (…) This includes a casino of imposing proportions. There are also plans for grand streets and boulevards and to complete it all, a racecourse with a 1,800-m track, a church and a town hall. This is what will be built very soon on the Marais land.Footnote4

In Le Touquet, the solicitor Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Daloz buys 1600 ha of warrens in 1819 for farming and agriculture (Chauvet, Beal, & Holuigue, Citation1982; Saudemont, Citation2011). Nevertheless, it is not until the 1870s and with the help of a man, Hippolyte de Villemessant, a friend of Daloz and founder of Figaro magazine, that the project for the creation of a seaside resort called Paris-Plage comes about.Footnote5 After that, the arrival of two English investors, John Whitley and Allen Stoneham, speed up the rise of Paris-Plage which becomes, as was the case for Dieppe, a ‘meeting place’ between London and Paris ().

Figure 1. Geographic location of Deauville, Dieppe and Le Touquet-Paris-Plage.

Source: Pécout, Machemehl, Penel (Esri, HERE, DeLorme, NGA, USGS).

Once the land is bought, it must be commercialized. In order to do this, the investors establish commercial businesses and turn to their networks of rich property-owning families, bankers and stockbrokers. The local press also intervenes by calling on speculators and financiers:

If you are looking for a good solid deal, with no chance of losing your capital, let us tell you about a special affair […]. Between Pont-l’Evêque, Trouville and the old Deauville, there is a flat area, 16 kilometres long, 4 kilometres wide and perfectly located between two hills […] It is an exceptional location; to make it prosperous, all that is needed is intelligence, which can do everything, and the capital, which is the power without which nothing can be done.Footnote6

So, in Deauville, between 1860 and 1864, about forty villas, a bathing establishment, a casino, a racecourse and a big hotel are built. Deauville and Le Touquet would be born from this process of coastline domestication.

Therefore, this spatial structuring is based on urban and leisure facilities that then generate ways of inhabiting and living in this new seaside area. And let us not forget that there is a native seafront population (fishermen, artisans, labourers). Dieppe, for example, continues its original industrial activities, which therefore results in the presence of two distinct worlds rubbing shoulders but whose ways of inhabiting the same place are completely different. For one group, it is about working to survive, while for the other it is about having fun and being entertained. The truth is that this leisure class of the aristocracy and the upper class plan their advent to the seaside resort around the entertainment and the practice of sports. Although this way of life based on leisure is already practised by the high-society population in Paris or London, the novelty lies in the investment in a seaside environment that provides a complete change of scenery to practice one’s leisure activities. Therefore, playing golf on the high cliffs of Dieppe or tennis along the seaside is a rare experience. That is why, the local stakeholders get involved in town planning strategies aimed at making resorts the most welcoming, the closest possible, the most modern, the most original, the most extensive sports offer, the most luxurious, etc. Therefore, being a seaside resort involves continuous transformations in terms of amenities, and therefore generates ways of living in seaside areas, since there would be a change from high-class tourism to mass tourism.

Making seaside resorts accessible

The conditions of accessibility are at the heart of the process of developing seaside resorts as it is the guarantor of the arrival of tourists.Footnote7 In the beginning, the journey is part of the adventure and the tourist experience (seeing, smelling, hearing), but speed and comfort then become priorities (Gagnon, Citation2007). Although there are roads, they are hardly used by the first tourists because travelling is mainly by horse-drawn carriages. It is not until the beginning of the twentieth century that the first motor cars are seen in resorts. This is not without causing some worries as the local press notes:

The car, that’s the enemy! That is the war cry that resounds on our roads, in our countryside, our streets and almost everywhere. Because you can’t take a step without running the risk of being crushed by this infernal machine.Footnote8

In Dieppe, the improvement in the security of the cross-Channel connection increases the frequency of boats and contributes to the development and establishment of the English community. Nevertheless, it is the railway and the railway station that influence the rise of seaside tourism (). The connection between Paris and Dieppe is established as of 1848 (3 h from Paris). The Etaples-Le Touquet stationFootnote9 is built in 1851. In 1900, it takes 3 h to get to the Paris station. As for the Deauville station, it was inaugurated on 1 July 1863. The system puts Paris 5 h from the Normandy coast. The technological advances and improvement in the railway connections progressively reduce the timeFootnote10 and the cost of the journey, which increases the influx and social diversity of tourists. As of the 1930s, these resorts, by virtue of their international reputation, thanks notably to private financiers, invest in the construction of an airport: in 1931 for Deauville, 1934 for Dieppe and 1936 for Le Touquet. The pace of opening up to the World and mobility accelerate.

Table 1. The main sports and leisure infrastructures of three seaside resorts.

The seafront: a spatial and functional unit

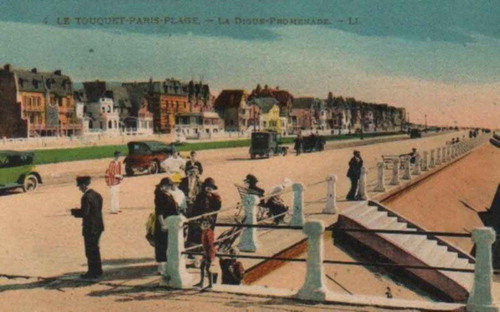

Seaside resorts are built and developed on the seafront because tourists must feel the change of scenery at all times. The seafront, the true heart of the resort, is comprised of a variety of places dedicated to the hotel industry, the restaurant industry, shops (general stores, luxury shopsFootnote11) and to leisure activities: dyke-promenade,Footnote12 tennis courts, baths, casino and racecourse. Therefore, this complex forms a spatial and functional unit, the economic life source of the resort, accommodating the largest concentration of tourists () .

But this division, and sometimes privatization of spaces to the benefit of the most fortunate would eventually pose problems. In Dieppe, the spaces connected to the town’s tourist functions are less distinct from the other urban functions. Conflicts of uses occur due to the close proximity of the English garrison to factories. In addition, access to the beach is a matter of competition between the areas for receiving Parisian high society and working-class establishments. Finally, traditional fishing practices, the presence of children or even beggars near to the casino is also perceived as a problem (Poullet, Citation2006). The truth is that despite the presence of natives, the fashionable elite like to get together every summer for several weeks. Therefore, this implies that the three resorts must adapt to meet the distinctive requirements of this clientele.

Making the seaside resort a sports area

One of the vital requirements for local stakeholders is to offer a variety of sources of entertainment for wealthy tourists who come to live for a maximum of three months per year (from July to September) because soon, sea baths are no longer enough. This elite wants new, extravagant, original things. In other words, they want to fully invest their holiday into taking advantage of the many leisure activities available. Sports activities meet this expectation. A symbol of high-society seaside life, the practice of sports concerns high-class sportsFootnote13 such as tennis, horse riding, golf, yachting or driving motor cars. Moreover, the practice of all sports is symbolic of this high-society culture. Consequently, the economic and political stakeholders invest in the building of sports facilities that are always more magnificent from one to the other, to offer what is best to their distinctive clientele as well as to differentiate themselves from the strong seaside resort competition. It is no longer only about creating a seaside resort; it has to be different, distinguished from the others to make it the reference.

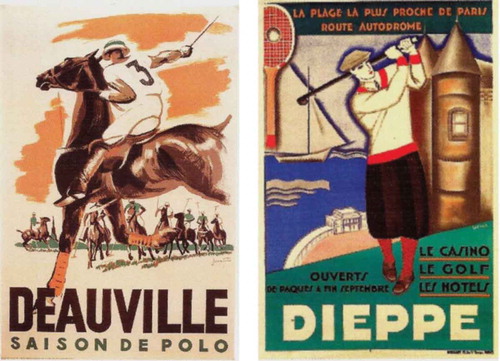

With regard to this, the study of post cards and travel advertisements indicates the predominance of sports in the representation of resorts. Travel advertisements, as a mass media, play a predominant role in the creation of an idealized imagined seaside resort. In this respect, by creating a territory magnified by these geographic (landscapes, panorama), tourist (casino, hotel) and sports assets, they stir the desire in tourists. The advertisements for Le Touquet, for example, highlight the sports facilities present (45-hole golf course, 30 tennis courts, a running field, the most beautiful swimming pool in Europe), besides its mineral heritage, Dieppe promotes its golf course on the cliffs while Deauville valourizes its horse riding and equestrian activities ().

Living and experiencing seaside areas through sports

The seaside resort, a space dedicated to leisure and tourism, involves ways of living, that is to say, ways of becoming involved in the space (Stock, Citation2015). Actually, once these places are developed, tourists besiege them, frequent them, experience them and inhabit them. But, as we mentioned earlier, ways of living change according to social and cultural evolutions in the uses of beaches. So, this seaside area is experienced in a different way by the leisure class from the working-classes which would progressively take over these resorts starting in the 30s–40s. The practice of swimming illustrates these ways of being with the sea (Terret, Citation1988). From an extremely codified practice at the end of the nineteenth century (dress codes, male/female separation, decorum), there is a change in the 30s to men and women swimming together, and where the female body progressively strips down. This means that the ways of living, and more specifically, of investing in the beach, change with the mentalities.

High-society sporting sociability

In our time, you live in the resort as a high-society tourist who is a temporary resident and whose raison d’être is leisure and entertainment. By this seasonal presence, you show that you are a ‘Socialite’, you appear in public, are seen and practice ostentatiousness. In this logic of seaside sociability, sports activities demonstrate the way of experiencing the seaside area. In fact, the practice of sports is part of the aristocratic and upper class world, highly influenced by the English gentry where the most important part of the activity is not in the performance or the competition, but in a sporting sociability based on common values: fair-play, courtesy, elegance, loyalty, etc. To this is added the fact that this form of sports practice is carried out in high-standing facilities and in natural environments that also generate emotions and new experiences.

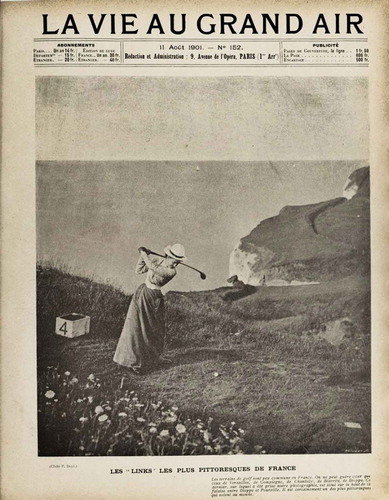

The most symbolic sports of these modes of practice are golf and lawn tennis. Created in 1897, prompted by English and Scottish golfers, the Dieppe golf course meets the demands of holidaymakers. Proof of this is in the quote from a letter sent by the English consul, Lee-Jortin to the sub-prefect, the mayor and the regional councillor, Charles Delarue a few years before:

Five or six years ago, I spent a holiday in Dieppe and as I am a golfer, I was very bored as a result of the absence of this activity for the English and Scottish. I had to spend my holiday taking walks on the beach during the day and looking for possible entertainment strolling at nights to the Casino … If the local authorities would like to make the charming Dieppe seaside resort a permanent source of attraction for the English, they should use all possible means to promote the establishment of a golf course, where my friends of the leisure society would go to play the old royal game, even if it is only between two boat rides Saturdays and Sundays.

Thanks to the architect Willie Park Jr, permanent attaché of the Saint Andrews Golf Course, the Dieppe golf course is created and provides players with an exceptional panorama. As a result, from the top of the cliffs (120 m), golfers can contemplate and admire the play of light from sky and sea, feel the wind and smell the iodine. The one in Deauville is built two years later in 1899 prompted by the Prince of Poix and the Count of Kergorlay. As the local press writes: ‘this golf course is an added attraction for the representatives of the Parisian high society as well as for strangers who come to Deauville in summer’.Footnote14 The one in Le Touquet, called ‘la forêt’ (the forest) is inaugurated in 1904 by the English Prime Minister. The golf club therefore becomes a place of living and activities that are symbolic of high-society life, where people go to have lunch, meet, appear in public and be seen ().

The other fashionable sport is lawn tennisFootnote15 (Peter & Tétart, Citation2003). It replaces real tennis and becomes popular as an open-air sport played on grass or on sand, thanks to the kit marketed by Major Wingfield that includes rackets and all that is required to install a net, posts and to mark out a court in the form of an hourglass (Clastres & Dietschy, Citation2009). To satisfy the players present, Deauville, prompted by Eugène Cornuché, director of the Trouville casino, builds a large tennis complex in 1912 in front of the casino along the beach (). With its 22 courts including a central one, the Sporting-club welcomes the most important of Paris society and organizes many international matches. All these sports amenities lead the newspaper, Les Echos de Deauville to comment:

There is only one place in the world developed specially to satisfy all sports, and that is Deauville: races, polo, clay pigeon shooting, croquet, real tennis, etc. Everything is played and on all types of fields.Footnote16

The same applies to Le Touquet, because to shine in terms of sports, thanks to the action of the industrialist John Withley, the resort hires Pierre de Coubertin, the most famous sportsman, as director of the resort (1903–1905). The Olympic Games reformer, who sees the opportunity to create his ideal City (Bermond, Citation2008), then undertakes many sports constructions. July 1904 is witness to the inauguration of the sports field for example, a multi-sports complex dedicated to racing, cycling and lawn tennis. Other spectacular investments follow, such as the creation in 1931 of a filtered seawater swimming pool, 66 m long with 4 diving boards and 500 cubicles that can accommodate up to 2000 people. As we can see, living as a tourist in these resorts involves practising sports since everything is made for this very practice. This taste for sport and its values then becomes a habitus (Bourdieu, Citation2000) within this seaside aristocracy, enabling people to meet each other.

On the other hand, while these three resorts equip themselves with sports infrastructure for their tourists, more limited local installations are also added (Rollan, Citation2004) for the local population. Because, in parallel with the seasonal offer for high-society tourists, there is a will to facilitate and develop sports activities for residents, especially starting in the 1930s based on popular activities or those that were becoming popularFootnote17 such as football, athletics, gymnastics and cycling. In 1933, Deauville for example, would build a stadium with a football field, a cinder track and a cycle track, enabling the organization of local competitions all year round. In Dieppe, the logic is the same. A local sports dynamism adds to and is mixed with the installations planned specifically for the holiday-making clientele. Earlier, in this quite particular context, the Dieppe Badminton club is created in the motor car garage of the Danish cycling champion Gaston Meyer.Footnote18 This same place accommodates roller skating and boxing. The popularization of sports in these resorts affects the ways of living since two sporting worlds meet: that of high-society tourists and the local population, more able to open up socially. To preserve the distinctive value of certain practices, tourists would give up some of them (velocipede riding, football) to invest in the most distinctive ones (golf, polo, sailing, motor car racing).

The abundance of events

Living in the resort is also having the possibility to participate in sports events. In fact, playing alone is not enough and this is why these resorts organize a summer sports calendar comprised of different competitions and above all, major events. As this combines new technological products and sensationalism, it operates as a vector to promote the resort.

The issues of image to which the economic stakes are related, therefore lead politicians, the investors and festival organizers to include more and more sports activities and events in their summer calendar. As a result of this necessity for events and promotions, the motor car, which is in its early stages at the beginning of the twentieth century, becomes a wonderful means for resorts to present something sensational to its seasonal population. Due to their spectacular nature, these events are very successful with a public that expects strong sensations, and at the same time are responsible for the reputation of the resorts. Dieppe coordinates the first motor car race in 1897. After that, in collaboration with the Automobile Club de France, it organizes the French Grand Prix four times between 1907 and 1912. In Deauville, the first race is organized in 1901, the mile run, which unites fifty runners and close to 9000 spectators. In August 1902, the town renews the initiative (the flying kilometre record), with 120 competitors, before 10,000 spectators. Finally, the crowning achievement of this motorcar event is the organization on 19 July 1936 of the only Grand PrixFootnote19 before 30,000 spectators.

Speed is on the roads, but it is also on the water with races in motorboats called racers and cruisers, between Paris and the sea. Organized from 1903 to 1939, they are part of the same promotional logic. Finally, this speed, which is synonymous with technical progress, is expressed by the organization of meetings. In August 1913 for example, it is the Paris–Deauville hydro aeroplane race that attracts the seaside crowd on the beach. For one week, thousands of spectators watch the top aviators confront each other in tests of endurance and speed, the occasion for true sporting feats. With the creation of the airport in 1931, the resort organizes international air meetings. These sports events ensure the tourist promotion of Deauville. The organization of international boxing and fencing galas, international regattas and polo competitions are some of the reasons for holidaying in the resort.

There are also many sports shows at Touquet Paris-plage. They benefit from the support of the Cercle International Du Touquet (Le Touquet International Circle) created by the Grand Duke Michael of Russia, Pierre de Coubertin, the Prince of Lucinge-Faucigny, the Duke of Morny and Allen Stoneham. Thanks to the Cercle, as of the 1910s, international tennis tournaments attract top players such as Suzanne Lenglen who wins the tournament in 1913 when she is only 14 years old. Dieppe with its regattas, motor car races and equestrian sports is not to be outdone. Under the effect of relative democratization, the valleys of Puys in the north-east and of Pourville-sur-mer in the south-west become seaside resorts. A little way away from the town, activities offered by major luxury hotels and casinos make it possible to preserve the distinctive character of the holiday.

Conclusion

The remarkable stories of Deauville, Dieppe and Le Touquet-Paris-Plage show that, through the conjunction of places and individuals, in the nineteenth century a way of living in these seaside resorts comes about, in which sports play an essential role. Seaside resorts are not a simple functional place, but actually a place where social relations are formed, in part thanks to sports.

In the definition of these three places, sports amenities played a predominant role in the urban structuring and development of these tourist territories. In addition, they enabled sports appropriation of spaces and contributed to the imagination required to live in these places, so that temporary residents become a part of a system of metabolic exchanges that are functional, emotional and symbolic among the places, people and things (Besse, Citation2013).

Places left vacant by the maritime industry and commerce in Dieppe, like the deserted inhospitable warrens in Le Touquet and Deauville, contributed to the rise of seaside cities. While there are multiple reasons for holidays (health, leisure), sports integrate this temporary way of life as a practice or a show. Promoted by companies, with or without a commercial objective, they are an integral part of a life of luxury before the support of the authorities would enable their democratization. In this respect, sports that develop in the resorts echo the sports dynamism of major towns and the summer mobility of the urban elite.

Sports participate in the development of a ‘milieu’ (Lyotard, Citation2000) in that they significantly influence the way of being. Building specialized facilities and developing sports event programs contribute to forging the recreational value of resorts. Sports are therefore a source of attraction because they make it possible to experience emotions through the practice and the show. They are a part of the resort experiences for the upper-class which fabricates this place, its codes and social norms. The flexibility of sports also provides a balance between the desire for recreation and moral dictates. In fact, Jean Corneloup (Citation2015) explains that a part of the social uses of the beach is in keeping with the difference in relation to certain cultural and moral principles that valourize uprightness, the values of work and progress. In the same way that the health virtues of baths were able to serve as justification, the strong presence of sports, free, competitive and virile constitutes means to justify emerging hedonistic practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Deauville declares itself ‘The Queen of Sports’ and Touquet ‘Sports Paradise’.

2. ‘The danger that we warn of now is the result of competition for our beaches from the Côte d’Argent, Brittany, and most of all, foreign beaches. The battle has begun, and it is even fiercer since the interests at stake are considerable. It is up to us to be the winners’. Trouville-Deauville, 25 July 1907.

3. This is a sandy place where rabbits live and where there are protected.

4. La Plage, 29 July 1860.

5. On 28 March 1912, the commune is officially named ‘Le Touquet Paris-Plage’.

6. Guide-Directory in Trouville-Deauville and the surrounding areas, 1866.

7. For 1907, Gabriel Désert was able to determine that 60,000 ‘strangers’ were in Trouville and 20,000 in Deauville.

8. L’Echo Des Plages, 25 July 1901.

9. But as it was located 3 km from Le Touquet, the rest of the journey was by electric tram as of 1900.

10. In 1890, the Paris–Deauville commute is 4 h and decreases to 2 h in 1936.

11. As an example, it is in Deauville that Coco Chanel opens her first shop during the summer of 1913 and establishes her fashion symbolized by the Flapper.

12. In Deauville, this promenade is completed in 1864. It is 1800 m long and 20 m wide and is one of the rare roads to have public lighting. At first called La Terrasse, it is renamed Les Planches in 1924.

13. According to the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française (French Academy Dictionary) of 1878, the word means horse racing, polo, fishing, hunting, fencing, golf, boating, baths.

14. L’Echo Des Plages, 30 July 1900. There are 600 active members in 1912.

15. Lawn tennis emerged in England and the first rules were enacted by Major Wingfield (1874). They were unclear and incomplete. Nevertheless, counting the score was the same as for real Tennis played outdoors (Longue Paume): 15–30–45–Game). In case of an equal score at 45, 2 consecutive points then had to be won to win the game (Advantage–Game). The match is won in 6 games (one set) with a lead of two games. The service is played from a zone in the shape of a diamond traced out in the middle of one side of the court. The ball had to bounce in a rectangle marked out at the end of the other side. The number of players could be from 2 to 8. Major Wingfield also decided that the ball had to be either hit in mid-air or after bouncing. The court was asymmetrical and obliged the teams to change sides to serve. It measured 18.29 m long and 6.40 m wide at the net and 9.20 m on the bottom line. The net was 1.42 m high.

16. Les Echos de Deauville, 20 August 1912.

17. As an example, in 1897, a multi-sports club, the Sports Association of Trouville-Deauville (ASTD) was created.

18. La vigie de Dieppe: 1 November 1907, 1 January 1908, 11 February 1908, 1 December 1908 and 21 December 1909.

19. During the race, two drivers would die after a multiple crash. A short film by English television can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4sNA1wDK03I.

References

- Andrieux, J.-Y., & Harismendy, P. (2011). Initiateurs et entrepreneurs culturels du tourisme (1850-1950). Rennes: PUR.

- Barjot, D., Anceau, E., & Stoskopf, N. (2010). Morny et l’invention de Deauville. Paris: A. Colin.

- Bermond, D. (2008). Pierre de Coubertin. Paris: Perrin.

- Bertho-Lavenir, C. (1999). La roue et le stylo. Comment nous sommes devenus touristes. Paris: Odile Jacob.

- Besse, J.-M. (2013). Habiter. Un monde à mon image. Paris: Flammarion, FR.

- Bourdieu, P. (2000). Esquisse d’une théorie de la pratique. Paris: Le Seuil.

- Boyer, M. (2005). Histoire générale du tourisme du XVIe au XXIe siècle. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Chauvet, J., Beal, C., & Holuigue, F. (1982). Le Touquet Paris-Plage à l’aube de son nouveau siècle 1882-1982. Béthune: Editions Flandres-Artois Côte d’Opale.

- Clastres, P., & Dietschy, P. (2009). Paume et tennis en France (XVe-XXe siècle). Paris: Nouveau Monde Editions.

- Corbin, A. (1988). Le territoire du vide, l’Occident et le désir de rivage, 1750-1840. Paris: Aubier.

- Corbin, A. (1995). L’avènement des loisirs (1850-1960). Paris: Aubier.

- Corneloup, J. (2015). Du bain de mer… aux bains de mer, analyse d’une transition culturelle. In P. Duhamel, M. Talandier, & B. Toulier (Eds.), Le Balnéaire, de la Manche au Monde (pp. 189–206). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Cueile, S. (2004). Les stratégies des investisseurs: Des bords de ville aux bords de mer. In Situ [En Ligne], 4. doi:10.4000/insitu.1756

- Desert, G. (1983). La vie quotidienne sur les plages normandes du Second Empire aux années folles. Paris: Hachette.

- Duhamel, P. (2015). Introduction générale: La permanence d’un désir: Une chronique sur le temps long. In P. Duhamel, M. Talandier, & B. Toulier (Eds.), Le Balnéaire, de la Manche au Monde (pp. 17–24). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Gagnon, S. (2007). Attractivité touristique et sens géo-anthropologique des territoires. Téoros. Revue De Recherche En Tourisme, 26(2), 5–10.

- Lazzarotti, O. (2006). Habiter. La condition géographique. Paris: Belin.

- Lyotard, J.-F. (2000). Misère de la philosophie. Paris: Galilée.

- Marec, Y., Daviet, J.-P., Garnier, B., Laspougeas, J., & Quellien, J. (2015). La Normandie du XIXème siècle. Entre tradition et modernité. Rennes: Editions ouest France.

- Pakenham, S. (1971). Quand Dieppe était anglais: 1814-19141. Dieppe: Les Informations dieppoises.

- Pécout, C., & Birot, L. (2008). La culture sportive mondaine à la Belle Epoque: Facteur du développement des stations balnéaire du Calvados. Annales De Normandie, 1(2), 135–147. doi:10.3406/annor.2008.6198

- Penel, G., Pécout, C., & Machemehl, C. (2016). Sports facilities as a strategic tool for structuring seaside resorts: The examples of Deauville, Dieppe and Le Touquet Paris-Plage. Society and Leisure /Société Et Loisir, 39(2), 46–60. doi:10.1080/07053436.2016.1151222.

- Peter, J.-M., & Tétart, P. (2003). L’influence du tourisme Balnéaire dans la diffusion du tennis en France. Le cas de la France de 1875 à 1914. Staps, 61(2), 74–91. doi:10.3917/sta.061.0073

- Pic, R. (2009). L’Europe des bains de mer. Paris: Éditions Nicolas Chaudin.

- Poullet, G. (2006). Au vrai chic balnéaire. Petits échos des plages normandes de 1806 à 1929. Condé-sur-Noireau: Editions Corlet.

- Rieucau, J., & Lageiste, J. (2006). L’empreinte du tourisme: Contribution à l’identité du fait touristique. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Rollan, F. (2004). Les réseaux d’équipements sportifs dans les stations balnéaires: L’exemple du tennis. In Situ [En Ligne], 4. doi:10.4000/insitu.1846

- Saudemont, P. (2011). Les 100 ans du touquet-paris-plage : 1912-2012. Neuilly-sur-Seine: M. Lafon.

- Stock, M. (2015). Habiter les stations balnéaires. Mobilités et pratiques des lieux à travers l’exemple de Brighton & Hove. In P. Duhamel, M. Talandier, & B. Toulier (Eds.), Le Balnéaire, de la Manche au Monde (pp. 323–338). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Stock, M. (2007). Théorie de l’habiter. Questionnements. In T. Paquot, M. Lussault, & C. Younès (Eds.), Habiter, le propre de l’humain (pp. 103–125). Paris: La Découverte.

- Terret, T. (1988). Bains de mer du nord et natation au XIXe, pratiques hygiéniques et loisirs de classe. Sport/Histoire, Revue Internationale Des Sports Et Des Jeux, 2, 9–22.

- Veblen, T. (1899/1970). Théorie de la classe de loisir (1er éd. ed.). Paris: Gallimard.

- Viard, J., Pottier, J.-F., & Urbain, J.-D. (2002). La France des temps libre et des vacances. Paris: Editions de l’Aube.