Abstract

Objective

The Celebrate Safe approach is a collaboration between public health organisations and music event/venue organisers to encourage health promotion interventions in nightlife settings and at music events. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the Celebrate Safe approach with regard to its impact on use of ear plugs among visitors of music events.

Design

A pre-registered cluster-randomised controlled trial conducted at music events throughout the Netherlands (k = 15). In the experimental condition, event organisers were asked to share an online pre-event message about ear plugs, clearly indicate where visitors could buy ear plugs, and sell ear plugs at busy locations on the premises. Visitors were encouraged to wear ear plugs by means of an ‘ear check’ at the beginning of the event.

Study sample: Observations to assess whether event visitors wear ear plugs (N = 3836).

Results

A multilevel model, taking into account nesting of visitors within events, revealed that use of ear plugs at music events in the experimental condition was higher in comparison to events in the control condition (23% vs. 14%, OR = 1.9, 95%CI 1.2–3.0, p = 0.004).

Conclusions

The Celebrate Safe approach has a positive impact on use of ear plugs among visitors of music events.

Introduction

Even young adults suffer from the negative consequences of exposure to loud noise. In a study in the USA, 6% of randomly sampled young adults at a community college reported perceived hearing loss, and 14% reported prolonged tinnitus (Holmes et al. Citation2007). A study among Flemish young adults with varying levels of noise exposure revealed that temporary and chronic tinnitus occurred in 69% and 6% of the sample, respectively (Degeest et al. Citation2017). In a survey among college students in the USA, 40% experienced at least one hearing symptom, with ear pain as the most frequently reported. About 80% of these students were involved in at least one noise activity (Balanay and Kearney Citation2015).

Music events are situations in which visitors are often exposed to loud sound and that also attract a lot of young adults. Many agents are involved in reducing (consequences of) exposure to loud sound at music events. First, at the policy level, some countries have guidelines to regulate sound exposure at music events (Beach et al. Citation2020), often limiting the allowed sound pressure levels and the duration of events (Tronstad and Gelderblom Citation2016). Second, at the organisational level, organisers of music events can place speakers further away from visitors and have attractive, low-volume and clearly indicated chill-out zones (Vogel, Brug, et al. Citation2009). At the same time, representatives of music venues believe that visitors demand high-volume music and are personally responsible for their own hearing (Vogel, Van der Ploeg, et al. Citation2009). A study in the UK, for example, revealed that some young adults chose not to use ear plugs because music venues are expected to be loud (Hunter Citation2018). Finally, at the individual level, this implies that visitors also need to engage in behaviours related to ear protection, such as visiting chill-out zones, distancing themselves from speakers, and using ear plugs.

To reduce various nightlife risks, such as hearing damage, Celebrate Safe was founded in 2015. The Celebrate Safe approach is a collaboration between public health organisations and music event/venue organisers to encourage health promotion interventions in nightlife settings and at music events. The aim of this collaboration is to promote the health and safety of visitors. Collaboration with organisers of music events is deemed crucial to create support for intervention activities at the organisational level. Another important aspect of the Celebrate Safe approach is the systematic method used to develop intervention activities. When designing intervention activities aimed at behaviour change, one of the crucial steps in the development process is to select the most relevant determinants (Bartholomew Eldredge et al. Citation2016). These determinants can be seen as the buttons one needs to push to establish behaviour change. Insight into these determinants is needed to determine the content of intervention activities, which should be aligned with these determinants. Within the Celebrate Safe approach, this is established by conducting a yearly survey among visitors of music events. The results of this survey are used to develop intervention activities. The topic of the survey differs each year and is relevant to one of the ten pillars. The pillars include alcohol and drug use, respecting sexual boundaries, and hearing protection, which was the focus of the intervention activities in 2019.

Use of ear plugs is effective in reducing post-concert threshold shifts (Kraaijenga, Ramakers, and Grolman Citation2016). However, in the Netherlands, only 6% of high school students reported consistent use of ear plugs when going out (Zweet and De Regt Citation2019). A study in the USA revealed that only 8% of adults reported consistent use of hearing protection devices, such as ear plugs, to loud athletic or entertainment events. Although younger adults were a bit more likely to use them, there is still much room for improvement (Eichwald et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, not using ear plugs in combination with using alcohol and/or drugs might be positively associated with developing temporary noise-induced hearing loss at music events (Kraaijenga, Van Munster, and Van Zanten Citation2018).

Encouraging use of ear plugs at music events is relevant to promote the health and safety of visitors of these events. The main research question in this study, therefore, is to what extent the Celebrate Safe approach results in an increase in use of ear plugs among visitors of music events. Intervention activities were developed in collaboration with organisers of music events and are described in more detail below. The secondary research question is to what extent organisers of music events adhere to activities aimed at promoting ear plugs.

Methods

To answer these questions, a cluster-randomised controlled trial was conducted at music events throughout the Netherlands. In the experimental condition, event organisers were asked to engage in or give permission to conduct the intervention activities described below. In the control condition, event organisers were not asked to do so. This study was pre-registered at the Open Science framework (Crutzen and Noijen Citation2019) to increase research transparency and reduce publication bias (Munro and Prendergast Citation2019). This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee (FHML-REC/2019/019) and falls outside the scope of the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO).

Intervention activities

Intervention activities were based on the results of a previously conducted survey among visitors of music events about use of ear plugs. The results are publicly available (Peters and Noijen Citation2019). Intervention activities were discussed with organisers of music events in terms of feasibility and acceptance. The Confidence Interval-Based Estimation of Relevance (CIBER) approach was used to select the most relevant determinants based on the survey data and use them as targets when developing intervention activities (Crutzen, Peters, and Noijen Citation2017). The CIBER approach acknowledges that it is necessary to combine two types of analyses when establishing relevance: (1) assessing the univariate distribution of each determinant (to see whether there is room for improvement) and (2) assessing the extent to which determinants are associated to the behaviour of interest (Crutzen and Peters Citation2020). The key determinants that were addressed in the intervention activities described here were good fit and price-quality trade off regarding ear plugs, difficulty remembering to wear ear plugs or to recognise when music is too loud, and not always knowing where to buy ear plugs at an event.

The first intervention activity was encouraging organisers of music events to share an online pre-event message about ear plugs in their final pre-event mail and on social media as well as the event website. The pre-event message encouraged bringing ear plugs to the event, and informed visitors who did not yet own ear plugs, where they could buy them in advance. Furthermore, the message informed attendees that there are differences between types of ear plugs and that it might take some time to get used to wearing them. The rationale behind this is that results of the previously conducted survey revealed that event visitors are already convinced that ringing in the ears and hearing damage are undesirable, but that a good fit and price-quality trade off regarding ear plugs is very important (and conversely, a lack of each potentially prohibitive). This is in line with previous research indicating high awareness of the benefits of using ear plugs (Beach, Williams, and Gilliver Citation2012), but at the same time loudness and appreciation of music being associated with the intention to use them (Kraaijenga, Van Munster, and Van Zanten Citation2018). Cheaper foam ear plugs are considered less satisfactory than more expensive ear plugs, which are relatively discreet and comfortable, facilitate communication with others, create minimal music distortion and, in some cases, improve music sound quality (Beach, Williams, and Gilliver Citation2010). A default message template was provided to event organisers, but they had the liberty to tweak this message in line with the channel and tone of voice they use to communicate with their visitors (e.g. two event organisers added an animated GIF [Graphic Interchange Format] to the message). The message template was ‘Don’t forget to bring your ear plugs. Don’t have any ear plugs? Buy them here http://shop.oorcheck.nl. If you order before 5 pm, then they are sent the same day. There are different types of ear plugs and everybody has their own preferences. In the beginning, it might take some time to get used to wearing ear plugs. The ear plugs provided here all have a music filter, which assures that you hear the music well, without distortion.’

The second intervention activity was encouraging visitors of music events to wear ear plugs. This was done by means of an ‘ear check’ at the beginning of the event (i.e. the first 2 h), directly after the security check at the entrance. Visitors were reminded in person to wear their ear plugs. In case visitors did not have ear plugs with them, they were directed towards possibilities to buy ear plugs at the event. The rationale behind this is that results of the previously conducted survey revealed that event visitors have difficulty remembering to wear ear plugs or to recognise when music is too loud, especially when they have used alcohol and/or drugs. This is in line with previous research indicating simply forgetting to use them is one of the main reasons given for low use (Gilles et al. Citation2014). The ear check activity was conducted by Unity peers (who are partners within Celebrate Safe). Unity peers are volunteer peer educators, organised by a Dutch prevention organisation, trained to deliver harm reduction prevention messages to nightlife patrons and visitors of music events.

The third intervention activity was increasing visibility of opportunities to buy ear plugs at the event. Event organisers were asked to clearly indicate where visitors can buy (different types) of ear plugs (e.g. on a map provided on paper and/or in the event app) and to sell ear plugs at locations at the event where a lot of visitors come (e.g. when buying drink tickets). These examples should be seen as such; event organisers were at liberty to vary their methods based on what was possible at that event (e.g. availability of event app, ability to vary locations). The rationale behind this is that results of the previously conducted survey revealed that event visitors did not always know where to buy ear plugs at an event.

Procedure

Events that were partnering with Celebrate Safe, on which Unity peers were expected to be present, and that were held during the study period (i.e. summer 2019) were included in this study. There were no further selection criteria. These events were matched on size (categorized as small [<5000 visitors], medium [5000–25,000 visitors] or large [>25,000 visitors]), location (indoor vs. outdoor), and music style (mixed or focussed on hardcore/hardstyle or house/techno). As this is a cluster-randomised controlled trial, randomisation (1:1) took place at the level of events after matching (using randomiser.org). All event organisers were invited to participate in this study (via email) and, when assigned to the experimental condition, were asked to engage in or give permission to conduct the intervention activities. For all events assigned to the experimental condition, we kept track of the extent to which online pre-event messages encouraged bringing ear plugs to the event, and informed visitors who did not yet own ear plugs, where they could buy them in advance, and the extent to which events allow an ear check at the beginning of the event. As event organisers had to engage in or gave permission to conduct intervention activities, they were not blinded to their allocation to either the experimental or control condition. The allocation was not explicitly revealed to event visitors, but they were exposed to the intervention activities.

Observations

The primary outcome regarding the main research question was the proportion of event visitors wearing ear plugs. This outcome was assessed by means of observations. The observations were conducted after the first two hours of the event (when the majority of visitors is present at the event). Every 10th visitor entering the toilet area was observed to register whether they were wearing ear plugs until the required sample size was reached. Observing every 10th visitor prevents bias introduced by observing groups (members of which might have similarities in terms of wearing ear plugs). During the study, it appeared that a deviation from the pre-registered protocol was needed, as at smaller events, observing every 10th visitor made it difficult to obtain the required sample size within the allocated time frame. Therefore, at smaller events, every 3rd visitor entering the toilet area was observed until the required sample size was reached, but still only one person per group was observed (in case there were groups with more than three people entering the toilet area together). Visitors were observed entering the toilet area to get a more representative sample of visitors (in contrast to, for example, observing at the bar) and to make it easier to ask whether people were wearing ear plugs (in cases where this could not be observed directly; e.g. because hair was covering the ears).

Sample size

The R package clusterPower (version 0.6.111) was used to conduct a power analysis (Reich et al. Citation2012). More specifically, the function crtpwr.2prop within that package. This function can be used to compute the power of a simple cluster randomised trial with a binary outcome, or determine parameters to obtain a target power. We assumed that in the summer of 2019 there would be 20 events where Unity peers would be present and the organisers of which would agree on data being collected; decided to use an alpha of .05 and a power of .80; and assumed an intraclass correlation of .01, and a relative increase of 25% regarding the primary outcome in the experimental condition in comparison to the control condition. Based on these assumptions, the required sample size was 127 observations per event.

Analyses

A multilevel model in which visitors (level 1) are nested within events (level 2) was used to assess the impact of the intervention activities on use of ear plugs among visitors of music events. The outcome is whether the visitor wore ear plugs (no/yes). The predictor is the condition (control/experimental) to which the event the visitor was visiting was assigned. In order to maximise scrutiny, foster accurate replication, and facilitate future data syntheses (Peters, Abraham, and Crutzen Citation2012), the data and R scripts used for the analyses presented in this article are available at the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/w4hf6).

Results

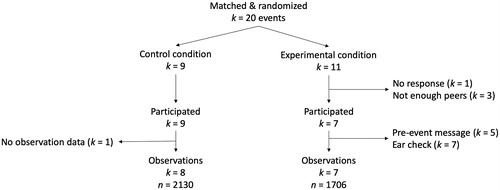

A total of 20 events met the selection criteria and were matched and randomly assigned to either the control condition or the experimental condition. Data on size, location, and music style are available at https://osf.io/sf62k/. shows the flow chart of the study.

Adherence to activities

All of the events assigned to the control condition agreed to participate. Observation data were collected at all but one of the events in the control condition. Of the events assigned to the experimental condition, 10 out of 11 agreed to participate. In the end, seven events participated. This was not due to event organisers not being willing to participate, but because there were not enough Unity peers available to conduct the intervention activities. At these seven events, the ear check was conducted. Five out of seven event organisers shared an online pre-event message about ear plugs. Observation data were collected at all events assigned to the experimental condition.

Use of ear plugs

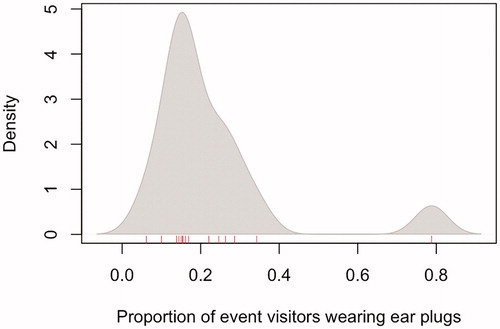

A total of 3836 observations were conducted at 15 events. shows the density plot of proportion of events visitors wearing ear plugs per event. Data from one event, assigned to the experimental condition, was deemed to be an outlier. Therefore, the multilevel model was run with and without data from this event, and the results of both analyses will be reported.

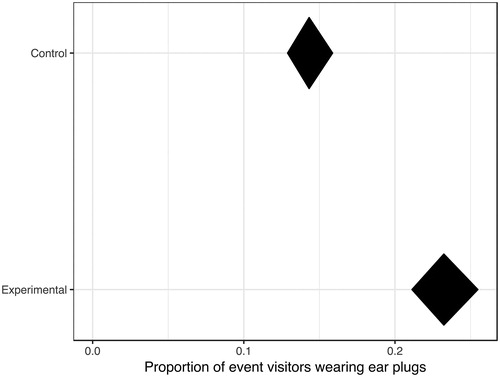

When including the outlier, the proportion of event visitors wearing ear plugs at events assigned to the control condition was 14% (95%CI 13–16%) in comparison to 32% (95%CI 30–34%) at events assigned to the experimental condition. A multilevel model, with the outlier included, revealed that use of ear plugs at music events in the experimental condition was higher in comparison to events in the control condition (OR = 2.7, 95%CI 1.2–6.0, p = 0.008). When the outlier was excluded, the proportion of event visitors wearing ear plugs at events assigned to the experimental condition was 23% (95%CI 21–25%). This is a relative increase of 62% compared to the control condition. The Number Needed to Treat (NNT) is 11.2, indicating the number of people that need to be exposed to the intervention in order to prevent an additional negative outcome (i.e. not wearing ear plugs). shows the proportion of events visitors wearing ear plugs in both conditions. A multilevel model, without the outlier, revealed that use of ear plugs at music events in the experimental condition was higher in comparison to events in the control condition (OR = 1.9, 95%CI 1.2–3.0, p = 0.004).

Discussion

The results of this study show that the Celebrate Safe approach has a positive impact on use of ear plugs among visitors of music events. Previous ear plug studies have mostly relied on self-reports to detect changes in determinants (Knobel and Lima Citation2014) and behaviour (Auchter and Le Prell Citation2014) due to intervention efforts aimed at promoting ear plugs. Observation data are likely to be more valid than self-report data, for example, because the latter is more vulnerable to social desirability bias (Cui et al. Citation2005), especially when the prevalence of the behaviour is low (Nelson Citation1996). We are convinced, therefore, that the use of observation data from a random sample of visitors is the best way to gain insight into the actual use of ear plugs at music events. Direct comparison to the numbers cited in previous studies should be done cautiously, because these were based on self-reports of consistent use of ear plugs (Eichwald et al. Citation2018; Zweet and De Regt Citation2019) instead of observed use at a single point in time. In these studies, 6% of Dutch high school students reported consistent use of ear plugs when going out (Zweet and De Regt Citation2019) and 8% of USA adults attending loud athletic or entertainment events (Eichwald et al. Citation2018). A previous study comparing self-report and observation data among workers’ use of hearing protection devices found less overlap between these types of data in variable noise environments (Griffin et al. Citation2009). To put the findings of this study into perspective, a previous study among rock and roll concert attendees using observations found 1.3% use of ear plugs and 8.2% use of ear plugs when they were provided for free (Cha et al. Citation2015).

The number of events at which observation data could be gathered was less than anticipated in the pre-registration. However, the number of observations per event surpassed the pre-registration. The confidence intervals reported above show that the proportion of events visitors wearing ear plugs could be accurately estimated, but there is room for improvement regarding the predictor in the multilevel models (Peters and Crutzen Citation2020). The relative increase compared to the control condition and NNT are deemed impactful given the limited resources needed for the intervention activities.

Three aspects need to be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, visitors were observed when entering the toilet area. While this might have resulted in a more representative sample of visitors, it could also be that some visitors have removed their ear plugs at this place because they are away from the noise. This would mean that the reported proportions of events visitors wearing ear plugs are conservative estimates. Second, this study included music events that took place across the Netherlands. It might be that at other types of events (e.g. sport or other types of entertainment) or events in other parts of the world, use of ear plugs varies as well as event organisers’ willingness to conduct intervention activities. Finally, non-optimal fidelity might have limited the possible effects of the intervention activities.

In this study, event organisers were generally willing to engage in or give permission to conduct intervention activities aimed at promoting ear plugs and also allowed observations at their events. Although no causal conclusions can be drawn based on the descriptive data regarding adherence, we think that the collaborative approach adopted by Celebrate Safe contributed to feasibility and acceptance of intervention activities by event organisers. Involving adopters and implementers of intervention activities in a participatory planning group is recommended for health promotion efforts in general (Bartholomew Eldredge et al. Citation2016). Obtaining commitment from event organisers, however, is not something that happens overnight. It takes time to build a shared understanding for initiatives such as the Celebrate Safe approach (Culmsee and Awati Citation2012). A key element of building such a shared understanding is adhering to the adage ‘nothing about us without us.’ This principle suggest that health promotion efforts should not be perceived as being imposed and, therefore, intervention activities were developed in collaboration with organisers of music events.

The current study focuses on promoting ear plugs at music events. This is just one of the focus areas within Celebrate Safe. The underlying idea of selecting the most relevant determinants based on survey data and using them as targets when developing intervention activities is applicable to all focus areas. In fact, this is applicable to developing behaviour change interventions in general (Crutzen and Peters Citation2020). The current study shows that this approach pays off in terms of increased use of ear plugs.

Conclusion

The intervention activities (i.e. sharing pre-event message, conducting an ear check at beginning of an event, and increasing visibility of opportunities to buy ear plugs at an event) had a positive impact on use of ear plugs among visitors of music events. The odds of using ear plugs at music events in the experimental condition were almost twice as high in comparison to events in the control condition. Event organisers were generally willing to engage in or give permission to conduct intervention activities aimed at promoting ear plugs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Unity coordinators, coaches and peers for their contribution to the field work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data presented in this paper are available at the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/w4hf6

Additional information

Funding

References

- Auchter, M., and C. G. Le Prell. 2014. “Hearing Loss Prevention Education Using Adopt-a-Band: Changes in Self-Reported Earplug Use in Two High School Marching Bands.” American Journal of Audiology 23 (2): 211–226. doi:10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0001.

- Balanay, J. A. G., and G. D. Kearney. 2015. “Attitudes Toward Noise, Perceived Hearing Symptoms, and Reported Use of Hearing Protection Among College Students: Influence of Youth Culture.” Noise and Health 17 (79): 394–405. doi:10.4103/1463-1741.169701.

- Bartholomew Eldredge, L. K., C. M. Markham, R. A. C. Ruiter, M. E. Fernández, G. Kok, and G. S. Parcel. 2016. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Beach, Elizabeth Francis, Robert Cowan, Johannes Mulder, and Ian O’Brien. 2020. “Regulations to Reduce Risk of Hearing Damage in Concert Venues.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 98 (5): 367–369. doi:10.2471/BLT.19.242404.

- Beach, E. F., W. Williams, and M. Gilliver. 2010. “Hearing Protection for Clubbers is Music to Their Ears.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia : Official Journal of Australian Association of Health Promotion Professionals 21 (3): 215–221. doi:10.1071/he10215.

- Beach, E. F., W. Williams, and M. Gilliver. 2012. “A Qualitative Study of Earplug Use as a Health Behavior: The Role of Noise Injury Symptoms, Self-Efficacy and an Affinity for Music.” Journal of Health Psychology 17: 237–246. doi:10.1177/1359105311412839

- Cha, J., S. R. Smukler, Y. Chung, R. House, and I. I. Bogoch. 2015. “Increase in Use of Protective Earplugs by Rock and Roll Concert Attendees When Provided for Free at Concert Venues.” International Journal of Audiology 54 (12): 984–986. doi:10.3109/14992027.2015.1080863.

- Crutzen, R., and J. Noijen. 2019. “Promoting Ear Plugs at Music Events: Evaluation of the Celebrate Safe Approach.” Open Science Framework. doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/AVMDR.

- Crutzen, R., and G.-J. Y. Peters. 2020. The Book of Behavior Change. 1st ed. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3570967.

- Crutzen, R., G.-J Y. Peters, and J. Noijen. 2017. “Using Confidence Interval-Based Estimation of Relevance to Select Social-Cognitive Determinants for Behaviour Change Interventions.” Frontiers in Public Health 5: 165. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2017.00165.

- Cui, M., F. O. Lorenz, R. D. Conger, J. N. Melby, and C. M. Bryant. 2005. “Observer, Self‐, and Partner Reports of Hostile Behaviors in Romantic Relationships.” Journal of Marriage and Family 67 (5): 1169–1181. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00208.x.

- Culmsee, P., and K. Awati. 2012. “Towards a Holding Environment: Building Shared Understanding and Commitment in Projects.” International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 5 (3): 528–548. doi:10.1108/17538371211235353.

- Degeest, S., H. Keppler, P. Corthals, and E. Clays. 2017. “Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Tinnitus after Leisure Noise Exposure in Flemish Young Adults.” International Journal of Audiology 56 (2): 121–129. doi:10.1080/14992027.2016.1236416.

- Eichwald, J., F. Scinicariello, J. L. Telfer, and Y. I. Carroll. 2018. “Use of Personal Hearing Protection Devices at Loud Athletic or Entertainment Events Among Adults - United States, 2018.” MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67 (41): 1151–1155. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6741a4.

- Gilles, A., I. Thuy, E. De Rycke, and P. Van de Heyning. 2014. “A Little Bit Less Would Be Great: Adolescents’ Opinion Towards Music Levels.” Noise & Health 16 (72): 285–291. doi:10.4103/1463-1741.140508.

- Griffin, S. G., R. Neitzel, W. E. Daniell, and N. S. Seixas. 2009. “Indicators of Hearing Protection Use: Self-Report and Researcher Observation.” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 6 (10): 639–647. doi:10.1080/15459620903139060.

- Holmes, Alice E., Stephen E. Widén, Soly Erlandsson, Courtney L. Carver, and Lori L. White. 2007. “Perceived Hearing Status and Attitudes Toward Noise in Young Adults.” American Journal of Audiology 16 (2): S182–S189. doi:10.1044/1059-0889(2007/022).

- Hunter, A. 2018. ““There Are More Important Things to Worry About”: Attitudes and Behaviours Towards Leisure Noise and Use of Hearing Protection in Young Adults”.” International Journal of Audiology 57 (6): 449–456. doi:10.1080/14992027.2018.1430383.

- Knobel, K. A. B., and M. C. P. M. Lima. 2014. “Effectiveness of the Brazilian Version of the Dangerous Decibels® Educational Program.” International Journal of Audiology 53 (sup2): S35–S42. doi:10.3109/14992027.2013.857794.

- Kraaijenga, V. J. C., G. G. J. Ramakers, and W. Grolman. 2016. “The Effect of Earplugs in Preventing Hearing Loss from Recreational Noise Exposure: A Systematic Review.” JAMA Otolaryngology- Head & Neck Surgery 142 (4): 389–394. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2015.3667.

- Kraaijenga, V. J. C., J. J. C. M. Van Munster, and G. A. Van Zanten. 2018. “Association of Behavior with Noise-Induced Hearing Loss among Attendees of an Outdoor Music Festival: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA Otolaryngology- Head & Neck Surgery 144 (6): 490–497. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2018.0272.

- Munro, K. J., and G. Prendergast. 2019. “Encouraging Pre-Registration of Research Studies.” International Journal of Audiology 58 (3): 123–124. doi:10.1080/14992027.2019.1574405.

- Nelson, D. E. 1996. “Validity of Self Reported Data on Injury Prevention Behavior: Lessons from Observational and Self Reported Surveys of Safety Belt Use in the US.” Injury Prevention : Journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention 2 (1): 67–69. doi:10.1136/ip.2.1.67.

- Peters, G.-J. Y., and R. Crutzen. 2020. “Knowing How Effective an Intervention, Treatment, or Manipulation is and Increasing Replication Rates: Accuracy in Parameter Estimation as a Partial Solution to the Replication Crisis.” Psychology & Health. doi:10.1080/08870446.2020.1757098.

- Peters, G.-J. Y., C. Abraham, and R. Crutzen. 2012. “Full Disclosure: Doing Behavioural Science Necessitates Sharing.” The European Health Psychologist 14: 77–84.

- Peters, G.-J. Y., and J. Noijen. 2019. Party Panel 17.1. https://www.partypanel.nl/resultResources/17.1/report.html.

- Reich, N. G., J. A. Myers, D. Obeng, A. M. Milstone, and T. M. Perl. 2012. “Empirical Power and Sample Size Calculations for Cluster-Randomized and Cluster-Randomized Crossover Studies.” Plos ONE 7 (4): e35564. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035564.

- Tronstad, T. V., and F. B. Gelderblom. 2016. “Sound Exposure During Outdoor Music festivals.” Noise Health 18 (83): 220–228. doi:10.4103/1463-1741.189245.

- Vogel, I., J. Brug, C. P. B. Van der Ploeg, and H. Raat. 2009. “Prevention of Adolescents’ Music-Induced Hearing Loss Due to Discotheque Attendance: A Delphi study .” Health Education Research 24 (6): 1043–1050. doi:10.1093/her/cyp031.

- Vogel, I., C. P. B. Van der Ploeg, J. Brug, and H. Raat. 2009. “Music Venues and Hearing Loss: Opportunities for and Barriers to Improving Environmental Conditions.” International Journal of Audiology 48 (8): 531–536. doi:10.1080/14992020902845907.

- Zweet, D., and L. De Regt. 2019. Gehoorschade in de jeugdgezondheidszorg. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: VeiligheidNL.