Abstract

The present study examined associations between psychopathic traits and deviant sexual interests across gender in a large community sample (N = 429, 24% men). Correlation analyses supported the positive link between psychopathic traits and deviant sexual interests. Regression analyses indicated that the unique variance in the antisocial facet of psychopathy predicted all six deviant sexual interests. The interpersonal facet predicted voyeuristic and exhibitionistic interests, whereas the affective facet predicted pedophilic interests. Moderation analyses revealed that gender moderated most of the relations between the antisocial facet of psychopathy and deviant sexual interests, such that those positive associations were stronger among women. On the contrary, the associations between the interpersonal facet and voyeuristic interests, as well as between the lifestyle facet and sadistic interests, were stronger among men. Findings appear to suggest that deviant sexual interests represent a domain in which the manifestation of psychopathic traits may differ across gender. These findings emphasize the relevance of psychopathic traits for the understanding and risk assessment of sexual deviance, while suggesting the need for gender-sensitive considerations.

Understanding sexual deviance has historically been a difficult endeavor, partly due to controversies in the very definition of sexual deviance (Bartels & Gannon, Citation2011; Laws & O’Donohue, Citation2008). These definitional issues have likely hampered the study of the etiology and correlates of sexual deviance, which is crucial to understand sexual deviance and to refine prevention and intervention programs (Watts, Nagel, Latzman, & Lilienfeld, Citation2017b). Overall, a common criterion for sexual deviance concerns the unusual nature of the source of arousal, either in terms of anomalous activity (e.g., voyeurism) or in terms of anomalous targets (e.g., pedophilia) (Feierman & Feierman, Citation2000; Leitenberg & Henning, Citation1995; Williams, Cooper, Howell, Yuille, & Paulhus, Citation2009). Specifically, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association (APA), Citation2013) lists eight forms of paraphilia, including sexual sadism, frotteurism, voyeurism, exhibitionism, and pedophilic disorders. Although we can assume that everyone experiences sexual interests, experiencing sexual interests in any of these domains can be used as an index of deviant sexual interests, which have been linked to increased likelihood to act upon these interests (Williams et al., Citation2009). Specifically, deviant sexual interest is defined for the purpose of the current study as the mental activity of thinking about (e.g., for curiosity, excitement, or attraction) or considering to engage in deviant sexual behavior.Footnote1 Previous research has shown that there are individual differences in the extent to which people express deviant sexual interests (Ahlers et al., Citation2011; Gee, Devilly, & Ward, Citation2004; Williams et al., Citation2009).

While sexual offenders generally report more deviant sexual interests than non-offenders (Buschman et al., Citation2010; Curnoe & Langevin, Citation2002; Gee et al., Citation2004; Leitenberg & Henning, Citation1995; Woodworth et al., Citation2013), deviant sexual interests are also frequent in community samples (Ahlers et al., Citation2011; Leitenberg & Henning, Citation1995; Williams et al., Citation2009; Wurtele, Simons, & Moreno, Citation2014). A recent study in male community participants revealed that 62.4% of the participants reported to experience sexual arousal in response to paraphilia-related sexual fantasies (Ahlers et al., Citation2011). Specifically, the rate of rape fantasies in non-offender samples can be as high as 31% (Leitenberg & Henning, Citation1995). A recent study found that up to 91% of male undergraduate students expressed sexual interest about various paraphilic activities and deviant sexual behavior, with higher prevalence reported for voyeurism, frotteurism, rape, and sadism (Williams et al., Citation2009).

As in the case of deviant sexual behavior, understanding the correlate of deviant sexual interests may provide important insights into their possible causes (Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, Citation2005; Watts et al., Citation2017b; but see Joyal, Cossette, & Lapierre, Citation2015, for a more csautious view). Recent studies on the nature and correlates of deviant sexual fantasies and interests have proposed that personality traits and disorders may represent one such avenue of research (Bartels & Gannon, Citation2011; Watts et al., Citation2017b). Very few studies have investigated associations between personality traits and deviant sexual interests (Curnoe & Langevin, Citation2002; Skovran, Huss, & Scalora, Citation2010; Watts et al., Citation2017b; Williams et al., Citation2009), yet they provided some initial evidence that psychopathic personality may be an important correlate of deviant sexual interests (for a review, see Bartels & Gannon, Citation2011).

Psychopathy is a personality disorder characterized by a pervasive pattern of interpersonal, affective, and behavioral dysfunctions (Hare & Neumann, Citation2006; Patrick, Fowles, & Krueger, Citation2009; Sellbom, Cooke, & Hart, Citation2015). In one of the most influential conceptualizations of psychopathy, interpersonal features are defined by grandiosity and manipulation, affective features include callousness and a lack of empathy, and behavioral traits are typically divided into an erratic and impulsive lifestyle and proneness to early and versatile antisocial tendencies (Hare & Neumann, Citation2006). There is compelling evidence that these four facets of psychopathy (interpersonal, affective, lifestyle, and antisocial) show differential associations with external correlates, although they can be subsumed in a higher-order psychopathy factor (at least as measured with the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised [PCL-R; Hare, Citation2003] and its derivatives; for a review, see Neumann & Hare (Citation2008).Footnote2

Many studies on psychopathy have been conducted among detainees and forensic psychiatric patients, due to the relatively higher prevalence of psychopathic traits in such populations (Hare, Citation2003). Although the prevalence of clinically significant levels of psychopathy in the general population is relatively small, there is substantial evidence that psychopathy is best conceptualized as a dimensional construct and that individual differences in psychopathic traits are also present in the general population (Edens, Marcus, Lilienfeld, & Poythress, Citation2006; Guay, Ruscio, Knight, & Hare, Citation2007; Neumann & Hare, Citation2008), with a strikingly consistent nomological network across different populations (Colins, Fanti, Salekin, & Andershed, Citation2017; Mullins-Nelson, Salekin, & Leistico, Citation2006; Sellbom, Citation2011). Studying psychopathy in the general population can have some important advantages. First, also in the general population, individual differences in psychopathic traits are related with a host of negative consequences, stressing the relevance of studying psychopathy also at subclinical levels (Colins et al., Citation2017). In addition, studies based in the general population can more easily allow the recruitment of larger samples, and the inclusion of more female participants, who are typically underrepresented in forensic and prison settings (Klein Tuente, de Vogel, & Stam, Citation2014). This seems particularly important because prior studies have been somewhat inconsistent about the similarities and differences in the nomological network surrounding psychopathy across gender (e.g., Sellbom, Donnelly, Rock, Phillips, & Ben-Porath, Citation2017), including the associations with deviant sexual interests (Watts et al., Citation2017b).

In general, the associations between psychopathic traits and a variety of externalizing behavior (e.g., aggression, substance abuse, and impulsivity) seem quite similar for men and women (Borroni, Somma, Andershed, Maffei, & Fossati, Citation2014; de Vogel & Lancel, Citation2016; Marion & Sellbom, Citation2011; Phillips, Sellbom, Ben-Porath, & Patrick, Citation2014; Sellbom et al., Citation2017; Warren & Burnette, Citation2013). However, prior studies have also highlighted meaningful gender differences in the associations between psychopathy and specific forms of aggression, with women being more likely to use relational (or social) aggression, and men being more prone to use physical aggression (Colins et al., Citation2017; Strand & Belfrage, Citation2005). Further, a study with nonclinical participants has shown that psychopathy in men exhibits stronger associations with antisocial behavior, aggression, and risk taking behavior, compared to women, who in turn manifest stronger relations between psychopathy and lack of empathy (Marion & Sellbom, Citation2011). At a facet-level, Miller, Watts, and Jones (Citation2011) found that the antisocial-lifestyle traits of psychopathy were more strongly related to impulsivity among men than women. Finally, across two studies, the affective-interpersonal traits of psychopathy were more strongly related to self-directed violence and intimate partner violence among women compared to men (Mager, Bresin, & Verona, Citation2014; Verona, Sprague, & Javdani, Citation2012).

In the realm of externalizing behavior, psychopathy is also associated with deviant sexual behavior (Krstic et al., Citation2018; Mokros, Osterheider, Hucker, & Nitschke, Citation2011; Muñoz, Khan, & Cordwell, Citation2011; Williams et al., Citation2009; Woodworth et al., Citation2013), although the association between psychopathy and deviant sexuality has been relatively understudied so far and also has produced mixed findings (Garofalo, Bogaerts, & Denissen, Citation2018). Nevertheless, theories of sexual offending often highlight the role of psychopathic traits in the manifestation of deviant sexual interests and behavior and the assessment of psychopathy is recommended when dealing with sexual deviance as an integral part of treatment planning (Laws & O’Donohue, Citation2008; Stinson, Sales, & Becker, Citation2008). Descriptively, a review of causes and correlates of sexual offending has identified some traits that make up the psychopathic syndrome as conceptually linked to the development and behavioral manifestation of deviant sexuality, namely: impulsivity, anger proneness, callousness, and lack of empathy (Stinson et al., Citation2008). Further, psychopathic behavior is often characterized by a craving for excitement that is not curtailed by social norms or a moral conscience (Purcell & Arrigo, Citation2006).

The theoretical foundations for a functional link between psychopathy and sexual deviance (and by extension, deviant sexual interests) date back to the early 1990s (for a review, see Purcell & Arrigo, Citation2006). Meloy (Citation1992) and Stone (Citation1998) were instrumental in this context, being among the first to suggest that sexual deviance could be explained by the lack of attachment or affective bonding with other human beings that characterize psychopathy. Specifically, Meloy (Citation1992) described three routes linking psychopathy with sexual deviance. One such route would involve the tendency to devaluate potential victims due to inability or unwillingness to empathize. A second route would involve the combination of angry and aggressive tendencies related to psychopathy with the individual’s detachment from the inner experience of others, which could make interpersonal cruelty likely. Third, and perhaps most relevant to the specific topic of sexual deviance, the attachment deficits and interpersonal detachment typical of psychopathy would increase the likelihood that potential victims are treated as mere (sexual) objects in private rituals, such as deviant sexual fantasies or cognitions. Of note, the relevance of attachment deficits is reflected in contemporary conceptualizations of psychopathy (e.g., in the Comprehensive Assessment of Psychopathic Personality; Cooke, Hart, Logan, & Michie, Citation2012), and their role in connecting psychopathy and sexual deviance has received some empirical support (Schimmenti, Passanisi, & Caretti, Citation2014a; Schimmenti et al., Citation2014b).

Additionally, Knight and Guay (Citation2006) have summarized other compelling explanations for an association between psychopathy and sexual deviance across three different—yet not mutually exclusive—routes, which involve both behavioral features and the central affective-interpersonal traits of psychopathy. First, they argued that the disinhibitory tendencies included in most conceptualizations of psychopathy (and specifically its behavioral components) may contribute to maintaining appetitive drive and deviant sexual behavior in circumstances where victim noncompliance should normally inhibit such behaviors and drives. Second, to the extent that empathy is central in the so-called violence inhibition system, the hypo-responsivity to distress cues in others that characterizes psychopathy (and specifically its affective-interpersonal components) may compromise the functioning of this natural inhibition system in the presence of noncompliant victims (Blair, Citation1995). Third, borrowing from evolutionary theories of psychopathy (e.g., Mealey, Citation1995), Knight and Guay (Citation2006) have argued for an evolutionary-based speculation on the covariation between psychopathy and sexual interests. Specifically, they highlighted the similarities between the short-term, cheating strategies that typify psychopathy and the short-term relationship, high-mating effort, and low parental investment strategy proposed to explain some forms of sexual deviance (e.g., rape).

Early accounts have posited that psychopathy may not be related with the tendency to derive pleasure from a variety of experiences—including sexual behavior—as part of a general poverty for affective reactions that supposedly lies at the core of psychopathy (Cleckley, Citation1976). From this point of view, deviant sexual behavior of individuals with psychopathy may be understood as a senseless act of cruelty or thrill seeking. However, more recent theories have proposed the alternative possibility that individuals with high levels of psychopathic traits may still derive genuine pleasure from activities that include the experience of manipulating, overpowering, and dominating others (Meloy, Citation1988). In addition to the theoretical links between psychopathy and sexual deviance reviewed above, from this perspective psychopathy could be related not only to an increased tendency to engage in deviant sexual behaviors, but also to an increased tendency to fantasize about and manifest interest in such behaviors, which in turn may increase the risk of acting on these fantasies and interests to derive pleasure.

Against this theoretical background, empirical research on psychopathy and sexual deviance is still in need of further expansion. There is some evidence linking psychopathic traits with sexually coercive tactics and behaviors in sex offenders (Olver & Wong, Citation2006; Porter et al., Citation2000), college students (Kosson, Kelly, & White, Citation1997; Muñoz et al., Citation2011), and community participants (Camilleri & Quinsey, Citation2009; Jones & Olderbak, Citation2014). Yet, prior studies on psychopathy and sexual deviance have been somewhat limited in two ways. First, they mostly relied on male samples, and little is known about whether gender moderates the associations between psychopathy and sexual deviance. In describing similarities and differences in the manifestation of psychopathic traits in men and women, Kreis and Cooke (Citation2012) proposed that “psychopathic women may use their sexuality more to manipulate and exploit others” (p. 269), although they cautioned that sexually predatory and exploitative behavior may not be typical of psychopathy in women. There is some preliminary evidence that gender differences may exist in the associations between psychopathic traits and sexual deviance. In a recent study, the association between psychopathic traits and the tendency to exploit an intoxicated partner was stronger among males compared to females, whereas the relation between interpersonal-affective psychopathic traits and physical coercion was stronger among females compared to males (Muñoz et al., Citation2011).

A second limitation of prior studies is that they mostly focused on deviant sexual behavior, largely overlooking possible underlying factors. Thus, it remains uncertain whether deviant sexual behavior represents a purely behavioral feature (e.g., stemming from problems with impulse control), or whether individuals with psychopathic traits manifest deviant sexual interests that are likely to predate deviant sexual behavior (Knight & Guay, Citation2006). Expanding current knowledge on the associations between psychopathic traits and deviant sexual interests across gender seems therefore urgently needed, in order to deepen our understanding of potential targets for prevention and intervention programs to reduce the risk of sexual deviance. A focus on (deviant) sexual interests might be especially favorable at subclinical levels of psychopathy, because individuals from the general population might be less likely to engage in actual deviant sexual behavior (Baughman, Jonason, Veselka, & Vernon, Citation2014; Williams et al., Citation2009). Further, as compared to overt deviant sexual behavior, sexual interests may be less constrained by social, cultural, or gender norms (Visser, DeBow, Pozzebon, Bogaert, & Book, Citation2015).

Of note, some prior studies have reported significant associations between higher levels of psychopathy and greater sexual interests for uncommitted, impersonal, and sadomasochistic or otherwise deviant elements (Baughman et al., Citation2014; Skovran et al., Citation2010; Visser et al., Citation2015; Watts et al., Citation2017b; Williams et al., Citation2009). Skovran et al. (Citation2010) found that sex offenders who met the diagnostic criteria for psychopathy (i.e., PCL-R scores ≥25) reported greater levels and a greater variety of deviant sexual fantasies compared to non-psychopathic sex offenders. In two studies with undergraduate samples, self-reported psychopathic traits moderated the relation between deviant fantasies and corresponding behavior, such that deviant sexual fantasies were more strongly associated with deviant sexual behavior only among participants with high levels of psychopathic traits (Visser et al., Citation2015; Williams et al., Citation2009). As such, psychopathy seems to be an important individual difference variable to take into account when studying deviant sexual interests, because it can help identifying those individuals that are at higher risk to engage in deviant sexual behavior (Bartels & Gannon, Citation2011; Knight & Guay, Citation2006; Visser et al., Citation2015). While providing important information on this matter, previous studies on this topic were limited by a reliance on undergraduate male samples, and by a focus on psychopathy total scores (e.g., Skovran et al., Citation2010; Williams et al., Citation2009). Thus, it is unclear whether deviant sexual fantasies show differential associations with each of the four psychopathy facets, as well as whether findings on the relation between psychopathy and deviant sexual interests are consistent across gender and can be found in a more diverse community sample.

A study that analyzed men and women separately at a facet-level, revealed that the zero-order associations between psychopathy and sexual fantasies were relatively stronger among women compared to men, and were rather wide-spread across psychopathy facets (Visser et al., Citation2015). Similarly, among college students, the callous, antagonistic, and coldhearted features of psychopathy were associated with rape myth acceptance, with stronger effect among women (Watts, Bowes, Latzman, & Lilienfeld, Citation2017a). However, another study found that psychopathic traits related to meanness and disinhibition (akin to the interpersonal-affective, and behavioral features of psychopathy, respectively) were positively related to a wide range of paraphilic interests (i.e., exhibitionism, fetishism, sexual sadism, transvestitism, and voyeurism) among undergraduates, with a consistent pattern across gender (Watts et al., Citation2017b).

In an attempt to advance research in this area, we examined associations between psychopathy facets and deviant sexual interests in a community sample, as well as the possible moderating effect of gender in these relations. As such, we extended current knowledge by simultaneously focusing on a more diverse sample and on a facet-level investigation of psychopathic traits in line with Hare’s conceptualization of psychopathy. Specifically, in line with previous studies (e.g., Watts et al., Citation2017b; Williams et al., Citation2009), we focused on the following deviant sexual interests: sadistic, rape, frotteuristic, voyeuristic, exhibitionistic and pedophilic. Although the present study was mostly exploratory, due to the paucity of prior studies and the inconsistency of findings on the moderating effect of gender in the association between psychopathy and externalizing behavior, some tentative hypotheses could be derived from prior studies. First, psychopathic traits were expected to correlate positively with deviant sexual interests. More specifically, when controlling for the shared variance among psychopathy facets, it was expected that the association between psychopathy and deviant sexual interests would be mostly driven by the behavioral features of psychopathy (Visser et al., Citation2015), though other studies using non-PCL-R-based measures have reported a unique predicting relation of the affective psychopathic traits on deviant sexual interest (e.g., Watts et al., Citation2017b, Citation2017a). Further, based on some prior findings (e.g., Visser et al., Citation2015; Watts et al., Citation2017a), we speculated that relations between psychopathy and sexual interests would be stronger for women, compared with men, although some studies did not find support for this possibility (e.g., Watts et al., Citation2017b).

Method

Procedures

The final sample was recruited in Belgium and the Netherlands as part of separate data collections. Participants were recruited by bachelor’s and master’s levels students for their thesis projects following a quota sampling procedure among their acquaintances. This strategy is similar to stratified sampling, because the students were asked to take age, gender and level of education into account in their recruitment procedures as much as possible (that is, balancing across gender and recruiting potential participants that were not too homogeneous in terms of age, education, and occupation). In this way, it was attempted to create a final sample that was close to a representation of the Dutch and Belgian populations (although, as can be seen in the description below, our sample was relatively highly educated and mostly consisted of women). In total, over 20 bachelor’s or master’s students contributed to the data collection in order to broaden the pool of potential participants from the general population.

Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Prior to participating in the research, participants were briefed about the study aims and received an information letter, and provided written informed consent to take part in the study. Participants filled-out the survey either on paper and pencil questionnaires or on an electronic form. To ensure anonymity, paper questionnaires were returned in closed envelopes, and on both paper and electronic surveys, participants’ names were replaced with an alphanumeric identification code. They were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time, having their responses removed from the database by providing the unique identification code they received on the information letter to the research team. The local Ethics Review Boards (ERB) formally approved all procedures.

Although the sample was recruited in two different countries (Belgium and the Netherlands) as part of separate data collections, we combined them in one bigger sample for several reasons. First, the groups did not differ substantially in any demographic or variable of interest. Second, they were administered identical versions of the questionnaires, because of the common language. Third, relying on a bigger sample allowed us to broaden the range of sample characteristics and increase statistical power—therefore the replicability of findings.

Participants

This research involved a community sample of 429 participants, with 102 male (24%) and 327 female (76%) participants. Participants were either living in the Flemish region of Belgium (N = 253) or in The Netherlands (N = 156; N = 10 missing data on this variable). Participants’ country of birth was similarly distributed, with 282 Belgian participants and 147 Dutch participants. The average age was 29.35 years (SD = 12.87, range = 18–75). Educational levels were distributed as follows: 4 participants (roughly 1%) completed lower education (i.e., elementary school), 14 participants (3%) lower secondary education (i.e., middle school), 162 participants (38%) higher secondary education (i.e., high school) and 249 (58%) participants completed higher education (i.e., community college or university).

Although the general demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender) do not align to the general Dutch and Belgian populations, being mostly young female participants, this convenience sample seems to resemble more closely a community sample than a student sample, given that participants’ source of income varied as follows: study loan, N = 48 (11%); parental support, N = 126 (29%); job, N = 216 (50%); pension, N = 5 (2%); other, or did not declare, N = 34 (8%).

Measures

Psychopathy

To measure psychopathy, the Dutch version of the Self-Report Psychopathy (SRP) scale (Paulhus, Neumann, & Hare, Citation2016) was used.Footnote3 The SRP is a widely used psychopathy self-report scale which is derived from the PCL-R (Hare, Citation2003), and assesses four psychopathy facets: interpersonal, affective, lifestyle and antisocial. The 64 items of the SRP ask participants to what extent they agree with each statement on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). Each of the four subscales contains 16 items. Subscale scores are computed averaging scores on the individual items comprising each scale, with higher scores indicating greater levels of psychopathic traits in each domain. The SRP has been validated for use in offender and non-offender populations (Paulhus et al., Citation2016; Mahmut, Menictas, Stevenson, & Homewood, Citation2011; Williams, Nathanson, & Paulhus, Citation2003). In this study, we used the Dutch/Flemish version of the SRP, which has recently been validated in a community sample demonstrating adequate psychometric properties and evidence of construct validity (Gordts, Uzieblo, Neumann, Van den Bussche, & Rossi, Citation2017). In the present study, internal consistency values were .83, .66, .76 and .63 for the interpersonal, affective, lifestyle, and antisocial facet, respectively. Based on George and Mallery’s (Citation2003) guidelines, the coefficient for the interpersonal facet can be considered good and the coefficient for the lifestyle facet acceptable. The coefficients for the affective and antisocial facets were questionable. The relatively lower internal consistency levels of the affective and antisocial facets are in line with prior studies in community samples (e.g., Mahmut et al., Citation2011; Gordts et al., Citation2017).

Deviant sexual interests

An adapted version of the Multidimensional Assessment of Sex and Aggression (MASA; Knight, Prentky, & Cerce, Citation1994) was used to measure deviant sexual interests. Regarding the psychometric properties of the MASA, Knight (Citation2004) found adequate to high test-retest reliabilities and internal consistencies. Further studies have supported the construct validity of the MASA scales to measure deviant sexual interests (or fantasies; Williams et al., Citation2009). The measure used in the present study was based on the adaptation used in Williams et al.’s (Citation2009) study to measure deviant sexual fantasies and behaviors. First of all, the measure was translated into Dutch keeping the equivalence with the original meaning of the items as the guiding principle for the translation procedure (Denissen, Geenen, Van Aken, Gosling, & Potter, Citation2008). A standard back-translation procedure was followed by two independent translators fluent in English whose native language was Dutch. A native English speaker checked the consistency of the original and translated versions and any instance of uncertainty was resolved in consultation between the three parts, as well as with one of the authors of the Williams et al.’s (Citation2009) study. Due to ethical considerations (i.e., the ERB required to limit the number of items because of the nature of the questions, some of which were deemed too intrusive), a short version of the MASA was used in the present study, including 15 items to measure interest in six deviant sexual activities, namely: sadism, frotteurism, voyeurism, pedophilia, exhibitionism, and rape. Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often), indicating the extent to which participants indulged in deviant sexual interests. The current study found internal consistency alpha estimates of .79, .68, .79, .98, and .72 for sadism (5 items), frotteurism (2 items), voyeurism (3 items), pedophilia (2 items), and exhibitionism (2 items), respectively.Footnote4 Based on the guidelines described by George and Mallery (Citation2003), the coefficients for sadism, voyeurism, and exhibitionism can be considered acceptable, and the coefficient for pedophilic interests excellent. The coefficient for the frotteurism scale fell just below the range of acceptable internal consistency and should be considered questionable. Of note, due to the ethical constraints mentioned earlier, rape interests were measured with a single item (i.e., “I have thought about forcing intercourse”), which made it impossible to calculate the internal consistency. A complete list of the items is reported in .

Table 1. Items of the adapted version of the Multidimensional Assessment of Sex and Aggression used in the present study to assess deviant sexual interests.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were calculated for all study variables. In order to examine gender differences in the four psychopathy facets and the six deviant sexual interests, two multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) were computed. Furthermore, hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed to examine the associations between psychopathy facets and each sexual interest category, as well as the interaction between gender and psychopathy facets. Gender (dummy-coded) and the four psychopathy facets (mean-centered to increase interpretability) were entered in the first step of each regression model, whereas the four interaction terms were entered in step 2, predicting one deviant sexual interest at a time. Simple slope analyses were used to further probe significant interaction effects. IBM SPSS 22.0 was used to conduct the statistical analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics and group differences for the key study variables across gender are reported in . Men scored significantly higher on the SRP total and scale scores than women, except for the antisocial facet, which did not differ significantly across gender. Conversely, women scored higher than men on levels of sadistic, pedophilic, exhibitionistic and rape interests. Correlation analysis results are displayed in . Overall, positive associations emerged among psychopathic traits and deviant sexual interests. A visual inspection of the correlation matrix revealed that the density of significant associations seemed greater in the female sub-sample.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations (SD), and gender differences for all study variables (N = 429).

Table 3. Pearson product-moment correlations among study variables in the male (N = 102; above the diagonal); and female (N = 327; below the diagonal) subsamples.

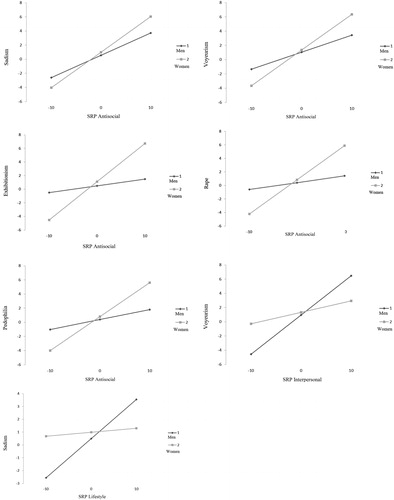

The results of the hierarchical multiple regression analyses are presented in . Regression models predicting all six sexual interest categories were significant. Controlling for gender, the antisocial facet of the SRP showed a unique and independent positive contribution to sadistic, frotteuristic, and rape interests. A significant positive relation was found for both the interpersonal and antisocial facets on voyeuristic and exhibitionistic interests. Next, both the affective and the antisocial facet of psychopathy were positively related to pedophilic interests. As shown in , nine significant interaction effects occurred. First, a negative interaction between gender and the antisocial facet was found in the models predicting sadistic, voyeuristic, pedophilic, exhibitionistic, and rape interests. Second, a positive interaction between gender and the lifestyle facet was found in the models predicting sadistic, pedophilic, and rape sexual interests. Finally, a significant positive interaction occurred between gender and the interpersonal facet in predicting voyeuristic sexual interests.

Table 4. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses examining the associations between gender, psychopathy facets, their interactions, and deviant sexual interests (N = 429).

Simple slope analyses were performed to further probe the significant interaction effects. The moderation results involving the criminal tendencies scale of the SRP, revealed the following interaction effects. First, the relation between the antisocial facet and sadistic sexual interest was significantly stronger among women (B = .50, p < .001) compared to men (B = .32, p < .05). Second, the relation between the antisocial facet and voyeuristic sexual interests was significant among women (B = .50, p < .001), but nonsignificant—and significantly weaker—among men (B = .24, p > .20). Likewise, the association between the antisocial facet and pedophilic sexual interests was significant among women (B = .48, p < .001), but nonsignificant—and significantly weaker—among men (B = .14, p > .20). Similarly, the relation between the antisocial facet and exhibitionistic sexual interests was significant among women (B = .56, p < .001), but nonsignificant—and significantly weaker—among men (B = .10, p > .50). In addition, also the relation between the antisocial facet and rape sexual interests was significant among women (B = .51, p < .001), but nonsignificant—and significantly weaker—among men (B = .10, p > .40).

A different pattern of interaction effects concerned the erratic lifestyle and the interpersonal manipulation scales of the SRP. First, the association between the interpersonal facet of the SRP and voyeuristic sexual interest was significant among men (B = .55, p < .001), but nonsignificant—and significantly weaker—among women (B = .16, p > .10). Next, the relation between the lifestyle facet and sadistic sexual interest was significant among men (B = .30, p < .05), but nonsignificant—and significantly weaker—among women (B = .03, p > .60). Finally, the relation between the lifestyle facet and both pedophilic and rape sexual interest was significantly stronger among men (B = .03, p > .80; and B = .11, p > .30, respectively) compared to women (B = −.07, p > .20; and B = −.03, p > .60, respectively), although they were all nonsignificant. A graphical depiction of simple slopes analyses for the significant interaction effects is presented in and in the supplemental materials.Footnote5

Discussion

This study examined the associations between psychopathic traits and deviant sexual interests with an emphasis on possible gender differences in these associations. We found evidence of significant associations between psychopathic traits and a variety of deviant sexual interests. After accounting for the overlap among psychopathy facets, these associations were predominantly driven by the unique variance in the antisocial facet of psychopathy. Examination of interaction effects by gender showed that—in most cases—associations between the antisocial facet of psychopathy and deviant sexual interests were significantly stronger among women. In general, these findings corroborate the hypothesized link between psychopathic traits and deviant sexual interests. Furthermore, our results appear to highlight an important distinction across gender, suggesting that psychopathic traits may be related to deviant sexual interests especially in women, providing new insights into the manifestation of psychopathy in women.

First, our results replicated the well-established gender differences on psychopathic traits (Cale & Lilienfeld, Citation2002), although we did not find significant gender differences on the antisocial facet, which might be explained by the low base rate of the antisocial facet in community samples. Further, the present study replicated earlier findings indicating that individual differences in deviant sexual interests can be reliably measured in community samples (e.g., Crépault & Couture, Citation1980; Gee et al., Citation2004; Hunt, Citation1974). Of note, Hsu et al. (Citation1994) argued that men fantasize more than women in general, although specific gender differences in deviant sexual interests were not extensively studied before, as most studies only included men. However, some studies reported similar levels of sexual interests in both men and women (e.g., Chivers, Roy, Grimbos, Cantor, & Seto, Citation2014; Moyano, Byers, & Sierra, Citation2016). The present study, on the contrary, appears to suggest that women report to experience deviant sexual interests more often, and especially about sadistic, pedophilic, exhibitionistic, and rape-like contents. If replicated, these partly unexpected results would warrant further investigation on the mechanisms explaining gender differences in the endorsement of these deviant sexual interests. For instance, studies that emphasize culture and sexual socialization across gender could greatly advance existing knowledge.

Extending recent findings obtained in undergraduate samples (Visser et al., Citation2015; Watts et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Williams et al., Citation2009), the current study provides evidence that self-reported psychopathic traits may be related to deviant sexual interests. Inspection of bivariate correlation coefficients already suggested that such association seemed to have relatively stronger effect sizes among women, compared to men. In light of the conceptual background presented above, several speculations could be made regarding possible mechanisms underlying the links between psychopathic traits and deviant sexual interests. Higher levels of psychopathic traits may be related to increased deviant sexual interests because of the attachment deficits and interpersonal detachment that characterize psychopathy (e.g., Meloy, Citation1992), because of a lack of empathy and the hypothesized deficits in the violence inhibition system (e.g., Blair, Citation1995), or due to evolutionary-based tendencies toward high-mating effort and low parental investment (e.g., Mealey, Citation1995). Future studies seem needed to test these different theoretical explanations provided. Interestingly, these different possible explanations offered in the literature are not mutually exclusive, and these mechanisms may well be operating in combination or following distinct etiological routes (Knight & Guay, Citation2006; Meloy, Citation1992), although empirical research is silent in this respect.

Regression analyses revealed that psychopathy facets significantly explained non-trivial portions of variance in all deviant sexual interests considered, accounting for roughly 7–17% of variance. In line with previous findings (Visser et al., Citation2015), investigation of the independent contribution of the unique variance in the four psychopathy facets showed that the antisocial facet significantly predicted scores on the six deviant sexual categories examined. Indeed, the antisocial facet was the only significant predictor of sadistic, frotteuristic, and rape sexual interests, and also predicted pedophilic interests. Of note, these three types of sexual interests were the only ones involving thoughts about an act that would require physical contact with the hypothetical victim. Therefore, it makes theoretical sense that these were related with the facet of psychopathy that resembles the overt behavioral features of the psychopathic personality construct (Woodworth et al., Citation2013). The antisocial facet of psychopathy also predicted pedophilic, voyeuristic, and exhibitionistic interests, indicating that the antisocial tendencies that characterize psychopathy may also extend to deviant sexual interests that do not necessarily involve physical contact with others. In summary, far from being a mere reflection of overt criminal behavior, the antisocial facet of psychopathy seemed related to interest in deviant sexuality that involves both a deviant activity and a deviant target, with stronger relationships with those deviant sexual interests that are both deviant and aggressive in nature (i.e., sadistic, pedophilic, and rape interests).

In light of the uniform pattern of bivariate associations between psychopathic traits across SRP facets and deviant sexual interests, regression analysis results should not be interpreted as evidence that only the antisocial facet of psychopathy is related to deviant sexual interests (Lynam, Hoyle, & Newman, Citation2006). Rather, the fact that none of the SRP facets had clear patterns of unique zero-order correlations with deviant sexual interests, appears consistent with theoretical assumptions that deviant sexuality related to psychopathy may be due to a combination of attachment deficits, lack of empathy, deficits in the violence inhibition system, angry tendencies, and disinhibition (Blair, Citation1995; Knight & Guay, Citation2006; Meloy, Citation1992; Stinson et al., Citation2008), that underlie both central affective-interpersonal and the more overt behavioral components of psychopathy.Footnote6 Nevertheless, above and beyond the relation between the shared variance among psychopathy facets and deviant sexual interests, especially the unique variance in the antisocial facet of psychopathy showed widespread predictive links with deviant sexual interests.Footnote7 Yet, some unique associations also occurred between the interpersonal and affective traits of psychopathy, and deviant sexual interests.

The interpersonal facet of psychopathy predicted voyeuristic and exhibitionistic interests, suggesting that these interests may not only be related to antisocial tendencies, but also to aspects such as grandiosity and interpersonal manipulation. It is indeed plausible to speculate that voyeuristic and exhibitionistic interests may be an example of the grandiosity and dominance that is related to psychopathy (Klipfel & Kosson, Citation2018; Lang, Langevin, Checkley, & Pugh, Citation1987), as well as a reflection of the general dissocial attitudes and a tendency to disregard interpersonal boundaries of psychopathic individuals (Meloy, Citation1988). Finally, pedophilic interest was associated with the affective facet of psychopathy, possibly indicating that this specific form of deviant sexual interest may not only be related to antisocial tendencies, but also to more pronounced disturbances in emotional functioning, involving callousness and a lack of empathy. Taken together, these findings involving central interpersonal and affective traits of psychopathy appear consistent with the possibility that profound attachment deficits and interpersonal detachment, and the corresponding tendency to see others as mere (sexual) objects, may explain links between psychopathic traits and deviant sexuality (Meloy, Citation1992).

It should be noted that prior studies that have adopted different operationalizations of psychopathy, as well as different assessment methods of deviant sexual interests, have reported a different pattern of associations between psychopathy facets and deviant sexual interests. For instance, Watts et al. (Citation2017a) found that the affective psychopathic traits had a unique contribution on rape myth acceptance. Another study found that controlling for the shared variance between the meanness and disinhibition psychopathy factors reduced the magnitude of associations between both factors and paraphilic interests, without a clear pattern of unique association between either factor and paraphilic interests (Watts et al., Citation2017b). Future studies incorporating multiple operationalizations of psychopathy seem needed to elucidate whether discrepancies across studies are attributable to different assessment methods or to different conceptualization of the constructs.

Overall, the present study extends prior findings that have mostly been focused on the more violent declensions of sexual deviance. Consistent with other recent studies (Visser et al., Citation2015; Watts et al., Citation2017b), we showed that psychopathic traits are related to broad range of sexual interests, in keeping with earlier research showing that offenders with psychopathic traits exhibited a more diverse profile of deviant sexual behavior compared to non-psychopathic offenders (Porter et al., Citation2000). Further, the present study provided novel findings on gender differences in the association between psychopathic traits and deviant sexual interests. Taken together, the main pattern appeared to show that associations between the antisocial facet of psychopathy and deviant sexual interests were significantly stronger among women, compared to men. First, only in women, pedophilic, exhibitionistic, and rape sexual interests were related to the antisocial facet of psychopathy. This may suggest that these deviant sexual interests particularly characterize the nomological network of psychopathy among women. Second, the association between the antisocial facet and sadistic interests was stronger among women, whereas the lifestyle facet of psychopathy was related to sadistic interests among men only. While largely exploratory in nature, these results appear to indicate that different mechanisms may explain sadistic interests across gender, calling for further investigation. Among women, sadistic interests might be related to the expression of antisocial tendencies, whereas among men sadistic interests might reflect a proneness to impulsive acts. Finally, voyeuristic interests were related to the antisocial facet of psychopathy among women only, but the relation between voyeuristic interests and the interpersonal facet of psychopathy was significant only among men. Again, this could point to different mechanisms related to deviant sexual interests across gender. Specifically, if voyeuristic interests, as all other deviant sexual interests, could reflect the antisocial tendencies that characterize psychopathy in women, voyeuristic interests may be more related to interpersonal dominance and manipulation among men.

As noted in a recent review (Bartels & Gannon, Citation2011), the body of literature on personality and deviant sexual interests is still too scarce to support speculations about the nature and direction of such relationships. That is, future studies are needed to examine whether engaging in deviant sexual interests contributes to the development of psychopathic traits, whether psychopathic traits facilitate and increase the frequency and variety of deviant sexual interests, or whether a reciprocal relationship occurs over time. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with Bartels and Gannon’s (Citation2011) claim that practitioners involved in treatment or risk assessment should take into account that psychopathic traits may be associated with a tendency to endorse deviant sexual interests that might remain unnoticed unless accurately scrutinized (see Harris, Boccaccini, & Rice, Citation2017 for alternative views).

In summary, our findings replicate and extend those of prior studies (Visser et al., Citation2015; Watts et al., Citation2017a; Williams et al., Citation2009) suggesting that psychopathic traits may be related to greater interests about deviant sexual behavior among women, compared to men. In the absence of a-priori hypotheses based on theory, and in light of previous studies that did not find support for the moderating role of gender (e.g., Watts et al., Citation2017b), we refrain from speculating about possible explanations for these gender differences in the links between psychopathic traits and deviant sexual interests. If replicated in different samples and with different assessment methods, these findings will require further scrutiny in order to pinpoint which processes may be responsible for the differential associations between psychopathic traits and deviant sexual interests across gender.

The results of this study should be interpreted considering a few limitations. First, we only relied on self-report measures, which may have inflated correlation coefficients due to common method variance. In addition, the internal consistency values of the affective and antisocial facets of psychopathy were relatively low, although consistent with previous studies in community samples (e.g., Mahmut et al., Citation2011; Gordts et al., Citation2017). However, because low reliability weakens correlation estimates, the low internal consistency values for these scales place our findings on the conservative side, rather than implying a risk of overestimation. Also, the present findings should be considered with caution in the absence of alternative measures of psychopathic traits, as well as of non-self-report measures of deviant sexual interests (e.g., implicit measures; Seifert, Boulas, Huss, & Scalora, Citation2017). In addition, some investigators have raised concerns about the applicability of PCL-based measures in women (e.g., Forouzan & Cooke, Citation2005; but see Neumann, Schmitt, Carter, Embley, & Hare, Citation2012 for evidence of good construct validity for the SRP across gender). Second, our measure of deviant sexual interests—albeit derived from a validated instrument—had to be adapted due to ethical consideration. Although internal consistency coefficients were generally good, and the items had good face validity, the convergent validity of this reduced form with more comprehensive measures of the same interests had not been empirically tested before. Third, although we strived to broaden the sociodemographic characteristic of our sample, the current study mainly involved relatively highly educated individuals, thus generalizations to other populations may not be warranted. Relatedly, young women were relatively more represented in our sample, calling for replication in samples with a more balanced male-to-female ratio and a wider age range.

In conclusion, the present study contributed novel findings supporting the often-neglected association between psychopathic traits and deviant sexual interests. Specifically, we reported novel findings about the manifestation of psychopathic traits among women, showing that women with high levels of psychopathic traits in the antisocial domain may be especially prone to experience a variety of deviant sexual interests. These findings can inform forensic research by indicating that individuals with psychopathic traits may be more likely to nurture interest about deviant sexual behavior, which can in turn increase the risk for deviant sexual behavior (Williams et al., Citation2009; but see also Seifert et al., Citation2017). Further, these findings can inform future studies on deviant sexual interests across gender, showing that different personality traits might be related to sexual interests in men and women.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (303.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Prior studies have alternatively used terms like deviant sexual fantasies, interests, or cognitions to refer to the tendency to indulge in the mental activity of thinking about deviant sexual behavior. Although certainly overlapping, these different terms may emphasize different aspects of such mental activities (e.g., cognitive, affective, physiological components). However, delineating terminological boundaries among these terms goes beyond the scope of the present study. In the interest of congruence with the content of the items used in the present study to measure this construct (see ), we elected to use the term deviant sexual interests when referring to the present study.

2 Other operationalizations describe the construct as a compound of maladaptive (e.g., callousness, disinhibition) and adaptive traits (e.g., boldness, stress immunity), placing less emphasis on the antisocial component (Lilienfeld et al., Citation2012; Patrick et al., Citation2009; Sellbom et al., Citation2015). However, for the sake of consistency with the measure used in the current study, we mostly refer to Hare’s (Citation2003) conceptualization of psychopathy.

3 The Dutch translation was made for the SRP-III, but the same measure is now published under the name SRP-4, although all items remained identical.

4 For two-item scales, internal consistency coefficients actually reflect inter-item correlation rather than alpha coefficients.

5 The two interaction effects where both slopes were nonsignificant are not reported.

6 Accordingly, follow-up analyses were conducted using the SRP total score, which yielded significant positive associations with sadistic (r = .38, p < .001), frotteuristic (r = .32, p < .01), and voyeuristic sexual interests (r = .38, p < .001), among men, as well as significant positive associations with all six deviant sexual interests among women (rrange = .21–.30, all ps < .001), and results remained virtually unchanged when the SRP total score was re-computed excluding the Antisocial scale items. Therefore, the Antisocial facet appears to explain important variance in deviant sexual interests, but not to account for all of the shared variance between psychopathy and deviant sexual interests.

7 Findings concerning the antisocial facet of psychopathy, as assessed with the SRP, may not be interpreted by some scholars as evidence for a link between psychopathic traits and deviant sexual interests, due to the argument that antisociality should not be regarded as a stand-alone component within the construct of psychopathy (e.g., Cooke, Michie, Hart, & Clark, Citation2004; Skeem & Cooke, Citation2010; but see Hare & Neumann, Citation2010; Neumann, Vitacco, Hare, & Wupperman, Citation2005, in support of the argument that antisociality is part and parcel of the psychopathy construct). The present study embraced a conceptualization of psychopathy that includes the presence of early, persistent, and versatile antisocial behavior (Hare, Citation2003), and the broader debate concerning the role of antisociality in the construct of psychopathy goes beyond the scope of the present study.

References

- Ahlers, C. J., Schaefer, G. A., Mundt, I. A., Roll, S., Englert, H., Willich, S. N., & Beier, K. M. (2011). How unusual are the contents of paraphilias? Paraphilia-associated sexual arousal patterns in a community-based sample of men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(5), 1362–1370.

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- Bartels, R. M., & Gannon, T. A. (2011). Understanding the sexual fantasies of sex offenders and their correlates. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16(6), 551–561.

- Baughman, H. M., Jonason, P. K., Veselka, L., & Vernon, P. A. (2014). Four shades of sexual fantasies linked to the Dark Triad. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 47–51.

- Blair, R. J. R. (1995). A cognitive developmental approach to morality: Investigating the psychopath. Cognition, 57(1), 1–29.

- Borroni, S., Somma, A., Andershed, H., Maffei, C., & Fossati, A. (2014). Psychopathy dimensions, Big Five traits, and dispositional aggression in adolescence: Issues of gender consistency. Personality and Individual Differences, 66, 199–203.

- Buschman, J., Bogaerts, S., Foulger, S., Wilcox, D., Sosnowski, D., & Cushman, B. (2010). Sexual history disclosure polygraph examinations with cybercrime offences: A first Dutch explorative study. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 54(3), 395–411.

- Cale, E. M., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2002). Sex differences in psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder. A review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 22(8), 1179–1207.

- Camilleri, J. A., & Quinsey, V. L. (2009). Individual differences in the propensity for partner sexual coercion. Sexual Abuse : a Journal of Research and Treatment, 21(1), 111–129.

- Chivers, M. L., Roy, C., Grimbos, T., Cantor, J. M., & Seto, M. C. (2014). Specificity of sexual arousal for sexual activities in men and women with conventional and masochistic sexual interests. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(5), 931–940.

- Cleckley, H. (1976). The mask of sanity (5th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

- Colins, O. F., Fanti, K. A., Salekin, R. T., & Andershed, H. (2017). Psychopathic Personality in the General Population: Differences and Similarities Across Gender. Journal of Personality Disorders, 31(1), 49–74.

- Cooke, D. J., Hart, S. D., Logan, C., & Michie, C. (2012). Explicating the construct of psychopathy: Development and validation of a conceptual model, the Comprehensive Assessment of Psychopathic Personality (CAPP). International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 11(4), 242–252.

- Cooke, D. J., Michie, C., Hart, S. D., & Clark, D. A. (2004). Reconstructing psychopathy: Clarifying the significance of antisocial and socially deviant behavior in the diagnosis of psychopathic personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18(4), 337–357.

- Crépault, C., & Couture, M. (1980). Men's erotic fantasies. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 9(6), 565–581.

- Curnoe, S., & Langevin, R. (2002). Personality and deviant sexual fantasies: An examination of the MMPIs of sex offenders. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(7), 803–815.

- de Vogel, V., & Lancel, M. (2016). Gender Differences in the Assessment and Manifestation of Psychopathy: Results From a Multicenter Study in Forensic Psychiatric Patients. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 15(1), 97–110.

- Denissen, J. J. A., Geenen, R., Van Aken, M. A. G., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2008). Development and validation of a Dutch translation of the Big Five Inventory (BFI). Journal of Personality Assessment, 90(2), 152–157.

- Edens, J. F., Marcus, D. K., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Poythress, N. G. (2006). Psychopathic, not psychopath: taxometric evidence for the dimensional structure of psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(1), 131–144.

- Feierman, J. R., & Feierman, L. A. (2000). Paraphilias. In L. T. Szuchman & F. Muscarella (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on human sexuality (pp. 480–518). New York, NY: John Wiley.

- Forouzan, E., & Cooke, D. J. (2005). Figuring out la femme fatale: Conceptual and assessment issues concerning psychopathy in females. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 23(6), 765–778.

- Garofalo, C., Bogaerts, S., & Denissen, J.J.A. (2018). Personality functioning and psychopathic traits in child molesters and violent offenders. Journal of Criminal Justice, 55, 80–87.

- Gee, D. G., Devilly, G. J., & Ward, T. (2004). The content of sexual fantasies for sexual offenders. Sexual Abuse : a Journal of Research and Treatment, 16(4), 315–331.

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 update (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Gordts, S., Uzieblo, K., Neumann, C., Van den Bussche, E., & Rossi, G. (2017). Validity of the Self-Report Psychopathy scales (SRP-III Full and Short Versions) in a community sample. Assessment, 24(3), 308–325.

- Guay, J.-P., Ruscio, J., Knight, R. A., & Hare, R. D. (2007). A taxometric analysis of the latent structure of psychopathy: evidence for dimensionality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(4), 701–716.

- Hanson, R. K., & Morton-Bourgon, K. E. (2005). The characteristics of persistent sexual offenders: A meta-analysis of recidivism studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(6), 1154–1163.

- Hare, R. D. (2003). Hare Psychopathy Checklist–Revised (PCL-R) (2nd ed.). Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems.

- Hare, R. D., & Neumann, C. S. (2006). The PCL-R assessment of psychopathy: Development, structural properties, and new directions. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy (pp. 58–90). New York, NY: Guildford Press.

- Hare, R. D., & Neumann, C. S. (2010). The role of antisociality in the psychopathy construct: Comment on Skeem and Cooke (2010). Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 446–454.

- Harris, P. B., Boccaccini, M. T., & Rice, A. K. (2017). Field measures of psychopathy and sexual deviance as predictors of recidivism among sexual offenders. Psychological Assessment, 29(6), 639–651.

- Hsu, B., Kling, A., Kessler, C., Knapke, K., Diefenbach, P., & Elias, J. E. (1994). Gender differences in sexual fantasy and behavior in a college population: A ten-year replication. Journal of Sex &Amp; Marital Therapy, 20(2), 103–118.

- Hunt, M. (1974). Sexual behavior in the 1970s. Oxford, England: Playboy Press.

- Jones, D. N., & Olderbak, S. G. (2014). The associations among dark personalities and sexual tactics across different scenarios. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(6), 1050–1070.

- Joyal, C. C., Cossette, A., & Lapierre, V. (2015). What Exactly Is an Unusual Sexual Fantasy?. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(2), 328–340.

- Klein Tuente, S., de Vogel, V., & Stam, J. (2014). Exploring the Criminal Behavior of Women with Psychopathy: Results from a Multicenter Study into Psychopathy and Violent Offending in Female Forensic Psychiatric Patients. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 13(4), 311–322.

- Klipfel, K.M., & Kosson, D.S. (2018). The relationship between grandiosity, psychopathy, and narcissism in an offender sample. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(9), 2687–2708.

- Knight, R. A. (2004). Comparisons between juvenile and adult sexual offenders on the Multidimensional Assessment of Sex and Aggression. In G. O’Reilly, W. L. Marshall, R. C. Beckett, & A. Carr (Eds.), Handbook of clinical interventions with young people who sexually abuse (pp. 203–233). London, England: Routledge.

- Knight, R. A., & Guay, J. P. (2006). The role of psychopathy in sexual coercion against women. In C.J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Knight, R. A., Prentky, R. A., & Cerce, D. D. (1994). The development, reliability, and validity of an inventory for the Multidimensional Assessment of Sex and Aggression. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 21(1), 72–94.

- Kosson, D. S., Kelly, J. C., & White, J. W. (1997). Psychopathy-related traits predict self-reported sexual aggression among college men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 12(2), 241–254.

- Kreis, M. K. F., & Cooke, D. J. (2012). The manifestation of psychopathic traits in women: An exploration using case examples. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 11(4), 267–279.

- Krstic, S., Neumann, C. S., Roy, S., Robertson, C. A., Knight, R. A., & Hare, R. D. (2018). Using latent variable- and person-centered approaches to examine the role of psychopathic traits in sex offenders. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 9(3), 207–216.

- Lang, R. A., Langevin, R., Checkley, K. L., & Pugh, G. (1987). Genital exhibitionism: Courtship disorder or narcissism?. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 19(2), 216–232.

- Laws, R., & O’Donohue, W. T. (2008). (Eds.) Sexual deviance: Theory, assessment, and treatment (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Leitenberg, H., & Henning, K. (1995). Sexual fantasy. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 469–496.

- Lilienfeld, S. O., Patrick, C. J., Benning, S. D., Berg, J., Sellbom, M., & Edens, J. F. (2012). The role of fearless dominance in psychopathy: Confusions, controversies, and clarifications. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 3(3), 327–340.

- Lynam, D. R., Hoyle, R. H., & Newman, J. P. (2006). The perils of partialling: Cautionary tales from aggression and psychopathy. Assessment, 13(3), 328–341.

- Mager, K. L., Bresin, K., & Verona, E. (2014). Gender, psychopathy factors, and intimate partner violence. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 5(3), 257–267.

- Mahmut, M. K., Menictas, C., Stevenson, R. J., & Homewood, J. (2011). Validating the factor structure of the Self-Report Psychopathy scale in a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 670–678.

- Marion, B. E., & Sellbom, M. (2011). An examination of gender-moderated test bias on the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(3), 235–243.

- Mealey, L. (1995). The sociobiology of sociopathy: An integrated evolutionary model. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 18(03), 523–541.

- Meloy, J. R. (1988). The psychopathic mind: Origins, dynamics, and treatment. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

- Meloy, J. R. (1992). The psychopathic mind: Origins, dynamics and treatment (2nd ed.). Northvale, NJ: Aronson.

- Miller, J. D., Watts, A., & Jones, S. E. (2011). Does psychopathy manifest divergent relations with components of its nomological network depending on gender?. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(5), 564–569.

- Mokros, A., Osterheider, M., Hucker, S. J., & Nitschke, J. (2011). Psychopathy and sexual sadism. Law and Human Behavior, 35(3), 188–199.

- Moyano, N., Byers, E. S., & Sierra, J. C. (2016). Content and Valence of Sexual Cognitions and Their Relationship With Sexual Functioning in Spanish Men and Women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(8), 2069–2080.

- Mullins-Nelson, J. L., Salekin, R. T., & Leistico, A.-M. R. (2006). Psychopathy, empathy, and perspective-taking ability in a community sample: Implications for the successful psychopathy concept. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 5(2), 133–149.

- Muñoz, L. C., Khan, R., & Cordwell, L. (2011). Sexually coercive tactics used by university students: A clear role for primary psychopathy. Journal of Personality Disorders, 25(1), 28–40.

- Neumann, C. S., & Hare, R. D. (2008). Psychopathic traits in a large community sample: Links to violence, alcohol use, and intelligence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 893–899.

- Neumann, C. S., Schmitt, D. S., Carter, R., Embley, I., & Hare, R. D. (2012). Psychopathic traits in females and males across the globe. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 30(5), 557–574.

- Neumann, C. S., Vitacco, M. J., Hare, R. D., & Wupperman, P. (2005). Reconstruing the “reconstruction of psychopathy: A comment on Cooke, Michie, Hart, and Clark”. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19(6), 624–640.

- Olver, M. E., & Wong, S. C. P. (2006). Psychopathy, sexual deviance, and recidivism among sex offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 18(1), 65–82.

- Patrick, C. J., Fowles, D. C., & Krueger, R. F. (2009). Triarchic conceptualization of psychopathy: Developmental origins of disinhibition, boldness, and meanness. Development and Psychopathology, 21(03), 913–938.

- Paulhus, D. L., Neumann, C. S., & Hare, R. D. (2016). Manual for the hare self-report psychopathy scale. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems.

- Phillips, T. R., Sellbom, M., Ben-Porath, Y. S., & Patrick, C. J. (2014). Further development and construct validation of MMPI-2-RF indices of global psychopathy, fearless-dominance, and impulsive-antisociality in a sample of incarcerated women. Law and Human Behavior, 38(1), 34–46.

- Porter, S., Fairweather, D., Drugge, J., Hervé, H., Birt, A., & Boer, D. P. (2000). Profiles of psychopathy in incarcerated sexual offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 27(2), 216–233.

- Purcell, C. E., & Arrigo, B. A. (2006). The psychology of lust murder: Paraphilia, sexual killing, and serial homicide. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Schimmenti, A., Passanisi, A., & Caretti, V. (2014a). Interpersonal and affective traits of psychopathy in child sexual abusers: Evidence from a pilot study sample of Italian offenders. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 23(7), 853–860.

- Schimmenti, A., Passanisi, A., Pace, U., Manzella, S., Di Carlo, G., & Caretti, V. (2014b). The relationship between attachment and psychopathy: A study with a sample of violent offenders. Current Psychology, 33(3), 256–270.

- Seifert, K., Boulas, J., Huss, M. T., & Scalora, M. J. (2017). Response bias on self-report measures of sexual fantasies among sexual offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 61(3), 269–281.

- Sellbom, M. (2011). Elaborating on the construct validity of the Levenson self-report psychopathy scale in incarcerated and non-incarcerated samples. Law and Human Behavior, 35(6), 440–451.

- Sellbom, M., Cooke, D. J., & Hart, S. D. (2015). Construct validity of the Comprehensive Assessment of Psychopathic Personality (CAPP) concept map: Getting closer to the core of psychopathy. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 14(3), 172–180.

- Sellbom, M., Donnelly, K. M., Rock, R. C., Phillips, T. R., & Ben-Porath, Y. S. (2017). Examining gender as moderating the association between psychopathy and substance abuse. Psychology, Crime & Law, 23(4), 376–390.

- Skeem, J. L., & Cooke, D. J. (2010). Is criminal behavior a central component of psychopathy? Conceptual directions for resolving the debate. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 433–445.

- Skovran, L. C., Huss, M. T., & Scalora, M. J. (2010). Sexual fantasies and sensation seeking among psychopathic sexual offenders. Psychology, Crime & Law, 16(7), 617–629.

- Stinson, J. D., Sales, B. D., & Becker, J. V. (2008). Sex offending: Causal theories to inform research, prevention, and treatment. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association.

- Stone, M. H. (1998). The personalities of murderers: The importance of psychopathy and sadism. In A. E. Skodol (Ed.), Psychopathology and violent crime: Review of psychiatry series (pp. 29–52). Washington, DC, USA: American Psychiatric Press.

- Strand, S., & Belfrage, H. (2005). Gender differences in psychopathy in a Swedish offender sample. Behavioral Sciences &Amp; the Law, 23(6), 837–850.

- Verona, E., Sprague, J., & Javdani, S. (2012). Gender and factor-level interactions in psychopathy: Implications for self-directed violence risk and borderline personality disorder symptoms. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 3(3), 247–262.

- Visser, B. A., DeBow, V., Pozzebon, J. A., Bogaert, A. F., & Book, A. (2015). Psychopathic sexuality: The thin line between fantasy and reality. Journal of Personality, 83(4), 376–388.

- Warren, J. I., & Burnette, M. (2013). The Multifaceted Construct of Psychopathy: Association with APD, Clinical, and Criminal Characteristics among Male and Female Inmates. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 12(4), 265–273.

- Watts, A. L., Bowes, S. M., Latzman, R. D., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2017a). Psychopathic traits predict harsh attitudes toward rape victims among undergraduates. Personality and Individual Differences, 106, 1–5.

- Watts, A. L., Nagel, M. G., Latzman, R. D., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2017b). Personality disorder features and paraphilic interests among undergraduates: Differential relations and potential antecedents. Journal of Personality Disorders. Advance Online Publication. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2017_31_327

- Williams, K. M., Cooper, B. S., Howell, T. M., Yuille, J. C., & Paulhus, D. L. (2009). Inferring sexually deviant behavior from corresponding fantasies the role of personality and pornography consumption. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(2), 198–222.

- Williams, K. M., Nathanson, C., & Paulhus, D. L. (2003). August). Structure and validity of the Self-Report Psychopathy scale-III in normal populations. Poster presented at the 111th annual convention of the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Canada.

- Woodworth, M., Freimuth, T., Hutton, E. L., Carpenter, T., Agar, A. D., & Logan, M. (2013). High-risk sexual offenders: An examination of sexual fantasy, sexual paraphilia, psychopathy, and offence characteristics. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 36(2), 144–156.

- Wurtele, S. K., Simons, D. A., & Moreno, T. (2014). Sexual interest in children among an online sample of men and women: Prevalence and correlates. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 26(6), 546–568.