Abstract

Lifespan is reduced by approximately 15 years in individuals suffering from severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Contributing to this is an increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome, an assortment of factors that confer risk of diabetes type 2 and cardiovascular disease. Body Mass Index (BMI) is predictive of metabolic syndrome. Previous research indicates that the BMI of incarcerated individuals not suffering from a major mental disorder increase during incarceration, especially amongst females. However, information on the development of BMI during forensic psychiatric care is scarcer, and follow-up periods have been short. Thus, the authors extracted data from the Swedish National Forensic Psychiatric Register regarding the longitudinal development of BMI in 3389 individuals who received court mandated forensic psychiatric care in Sweden during 2009–2020. A significant increase in BMI by 1.1% per year was observed during the first four years of care. After this, changes were no longer significant. Factors associated with a larger increase in BMI were female gender, being prescribed antipsychotics, young age at admission, receiving outpatient care, and access to an external support person. There was an inverse association between BMI and symptom severity. Substantial heterogeneity was observed in longitudinal changes in individual BMI and in comparisons between individuals receiving care at different clinics.

Introduction

Mental disorder is associated with substantial medical comorbidity and excess mortality due to natural causes (Walker, McGee, & Druss, Citation2015). These issues are especially salient in the case of severe forms of mental illness; in schizophrenia spectrum disorder reductions of lifespan exceeding 20 years have been reported in some comparisons to the general population (Tiihonen et al., Citation2009). Meta-analytical research of geographically diverse data has estimated that 14.5 years of potential life are on average lost for individuals suffering from schizophrenia spectrum disorder (Hjorthøj, Stürup, McGrath, & Nordentoft, Citation2017). Even though increased risks of suicidality and accidental death partially explain this phenomenon, previous studies have suggested that these disparities are mainly conferred by somatic health issues (Laursen, Nordentoft, & Mortensen, Citation2014). There have been indications that the size of this so-called mortality gap has increased over time, implying that individuals afflicted by schizophrenia spectrum disorder have not reaped the benefits of efforts to improve public health (e.g., smoking cessation campaigns, improved medical screening) to the same extent as the general population (Hayes, Marston, Walters, King, & Osborn, Citation2017; Nielsen, Uggerby, Jensen, & McGrath, Citation2013). Several issues have been suggested to contribute to poor health in individuals suffering from psychotic disorders. These include lower utilization of healthcare (Swildens, Termorshuizen, de Ridder, Smeets, & Engelhard, Citation2016), under-recognition of somatic comorbidity by clinicians treating individuals suffering from major mental illness (Dornquast et al., Citation2017), life-style factors such as smoking or sedentary behavior (Fernández-Abascal, Suárez-Pinilla, Cobo-Corrales, Crespo-Facorro, & Suárez-Pinilla, Citation2021; Sagud, Mihaljevic Peles, & Pivac, Citation2019), and side-effects of antipsychotic medication (Whitaker, Citation2020). One focal point of previous research has been the prevalence and prevention of metabolic syndrome (Mitchell et al., Citation2013). Metabolic syndrome refers to a set of factors that increase risk for cardiovascular disease, atherosclerosis and diabetes type 2. These include hypertension, hyperglycemia, central obesity (belly fat) and dyslipidemia (Kassi, Pervanidou, Kaltsas, & Chrousos, Citation2011). Cardiovascular disease was the leading cause of death globally in 2019 (WHO, Citation2021) and considering the well-established association between metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, the improvement of metabolic health parameters has been emphasized as crucial for improvement of health outcomes in patients suffering from schizophrenia spectrum disorder (Mitchell et al., Citation2013).

Arguably, special consideration is warranted in the context of forensic psychiatry. Although most individuals with a psychotic disorder are not criminally convicted, a large proportion of patients within forensic services suffer from schizophrenia spectrum disorder (Vasic et al., Citation2018). Perhaps unsurprisingly, research with forensic populations have revealed that this group suffers from health issues that are similar to those afflicting non-forensic mental health populations with similar psychopathology (Andiné & Bergman, Citation2019; Moss, Meurk, Steele, & Heffernan, Citation2022). However, direct translatability of findings in general psychiatric populations to the forensic context can be problematic, as the concerned populations arguably could be expected to differ in some personal factors and clinical presentation (Epperson et al, Citation2014). In the Swedish context, forensic mental health patients with a psychotic disorder are afflicted by more complex comorbid psychopathology (e.g., substance abuse, personality disorder, cognitive deficits) and an overall higher level of illness severity, when comparisons are made with non-convicted patients suffering from similar psychopathology (SBU, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). In addition, environmental factors specific to compulsory forensic care (e.g., highly restrictive physical environment, daily access to healthcare personnel) could arguably be expected to influence health outcomes in forensic psychiatric patients. A review of cardiometabolic dysregulation in forensic inpatients with psychotic disorders by Ma, Mackinnon, and Dean (Citation2021) illustrates the importance of avoiding uncritical extension of findings from non-forensic psychiatry. The forensic group, as expected, compared unfavorably to the general public on indicators of cardiometabolic dysregulation. However, when compared to controls suffering from psychotic disorders, the forensic sample had similar or lower scores on indices of cardiometabolic disease, indicating more favorable health outcomes. Treatment regimens in forensic psychiatry and non-forensic psychiatry could also differ, as indicated by a comparison of pharmacological treatment regimens for forensic and non-forensic psychiatric populations in Germany, which revealed that the forensic group was prescribed less medication than non-forensic controls with psychotic disorders (Vasic, Citation2018). However, openly available data from the Swedish National Forensic Psychiatric Registry (Citation2021) demonstrate that antipsychotic polypharmacy and prescription of clozapine (an antipsychotic intended for hard-to-treat patients) is more common in forensic psychiatry, suggesting heterogeneity in national practices.

A key factor to consider in the case of somatic health concerns within the forensic population is whether the highly restrictive and controlled environment typical of forensic inpatient psychiatry mainly exerts a positive or negative influence on the overall health of the population. Arguably, a reasonable hypothesis is that inpatient hospitalization can have positive effects on a person’s physical health. Structured care could entail increased support and close assessment by medical personnel allowing management of activity levels and monitoring of somatic health concerns, in addition to mental health care. However, research into the experience of forensic psychiatric inpatients has revealed that feelings of hopelessness and disempowerment are common (Senneseth, Pollak, Urheim, Logan, & Palmstierna, Citation2021). Previous studies within the Swedish forensic psychiatric services have emphasized the indeterminate length of care, difficulties in understanding the care process and the power dynamics of the patient-caregiver relationships as perceived impediments to supportive care relationships (Nyman, Hofvander, Nilsson, & Wijk, Citation2022; Söderberg, Wallinius, Munthe, Rask, & Hörberg, Citation2022). Furthermore, results from time use studies, conducted both in Sweden and internationally, have indicated that patients spend a large proportion of their day in unstructured settings devoid of purposeful activities and therapeutic content (e.g., watching TV in a day room setting) (O’Connell, Farnworth, & Hanson, Citation2010; Sturidsson, Turtell, Tengström, Lekander, & Levander, Citation2007).

Reviews on the effects of incarceration in prison populations suggest that imprisonment is associated with an increase in weight (Bondolfi et al., Citation2020; Gebremariam, Nianogo, & Arah, Citation2018) and that incarcerated women are at increased risk of adverse health outcomes (Herbert, Plugge, Foster, & Doll, Citation2012). To the knowledge of the authors, no meta-analyses of the longitudinal effects of forensic care on weight or other metabolic variables exist. However, the few studies that are known to the authors have indicated substantial weight gain during the initial period of inpatient forensic psychiatric care (Hilton, Ham, Lang, & Harris, Citation2015, Hilton, Ham, Hill, Emmanuel, & Thege, Citation2022; Long, Rowell, Gayton, Hodgson, & Dolley, Citation2014) and that this pattern is more pronounced in female patients (Long et al., Citation2014). However, sample sizes in studies from the forensic context are quite small, with the largest longitudinal follow-up known to the authors encompassing a total of 351 individuals (Long et al., Citation2014). In two of the three studies, follow-up time was one year, whilst one study reports follow-up data after three years. Longer treatment durations are not uncommon within forensic psychiatry (e.g., Gaab, Brazil, de Vries, & Bulten, Citation2020; Hare Duke, Furtado, Guo, & Völlm, Citation2018). Reported data on the average length of stay within the Swedish forensic services differ somewhat. An average time-to-discharge of 2.61 years was reported in a local follow-up of 125 patients admitted to forensic psychiatric care between 1999 and 2005 in the Skåne Region (Andreasson et al., Citation2014). Later studies report on longer durations of stay, with a governmental review of pharmacological treatment within forensic services stating that the median length of a care episode exceeds five years (SBU, Citation2018a), whilst national registry data indicates that this number is 95 months (Swedish National Forensic Psychiatric Registry, 2021). Thus, studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods investigating the trajectory of changes in body weight seems warranted.

We set out to conduct a long-term cohort study of the development of Body Mass Index (BMI), a major risk factor for metabolic syndrome (Krishnamoorthy, Rajaa, Murali, Sahoo, & Kar, Citation2022), in a population undergoing court-mandated forensic care. We did this utilizing data from the Swedish National Forensic Psychiatry Registry, encompassing the time-period 2009–2020. The main objective of the study was to investigate changes in BMI among forensic patients with and without a psychotic disorder during their stay within forensic services. A secondary aim was to investigate the role of potential moderating factors such as age, gender, prescribed antipsychotic medication, history of substance abuse, symptom severity, possibilities of unsupervised leave and treatment site.

Method

Sample characteristics

Data covering the time period 2009–2020 was extracted from the Swedish National Forensic Psychiatric Registry, a national health care register intended to provide data on Swedish forensic mental health care to measure outcomes, facilitate improvement of care and support research in the area. Patients sentenced to compulsory forensic psychiatric care in Sweden are approached regarding consent for inclusion in the register during their time as forensic patients. In 2021, 24 out of 25 forensic psychiatric treatment sites participated in data collection for the registry and 82% of Swedish forensic psychiatric patients agreed to have their data registered (Swedish National Forensic Psychiatric Registry, 2021). Data is registered at least once a year in an annual follow-up. In addition to this, registrations also take place during special events, such as transfer from one care unit to another, conversion of inpatient to outpatient care and discharge from forensic mental health care. Approval for the study was received from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (DNR: 2020-05349).

For this study, data regarding all individuals with two or more registrations during 2009–2020 was extracted, encompassing a total of 3536 subjects (2956 males, 579 females, 1 subject with unknown gender). The data included 16,078 observations of BMI, resulting in a mean number of observations of 4.55 per patient (SD = 3.27, Mdn = 4, Range = 0–18). Patients with no observations of BMI (n = 147) were not included in the analyses, leaving a sample size of 3389 (mean number of observations of BMI = 4.74, SD = 3.20, Mdn = 4, Range = 1–18). Across all observations, the mean age of the patients was 41.88 years (SD = 12.66, Mdn = 40.63, Range = 16.44–92.78). At the first registration, mean age was equal to 38.60 years (SD = 12.81, Mdn = 36.69, Range 16.44–91.05). Due to data availability issues, not all 3389 patients selected for analysis were included in all sub-analyses conducted.

A patient was considered to have received a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder if they ever received a diagnosis of ICD-10 codes F20-F29, with the exception that the first registration was not considered, to avoid influence of diagnostic uncertainty early in the care process. With this method 2314 subjects were categorized as suffering from a psychotic disorder (1970 males, 343 females, 1 unknown gender) and 903 as not suffering from a psychotic disorder (712 males, 191 females) whilst data regarding diagnosis was missing for 319 subjects (274 males, 45 females).

Variables extracted

Data was extracted to investigate the association between demographic, clinical and environmental factors and changes in BMI during forensic psychiatric inpatient care. Variables associated to demographic and clinical factors including age, sex, symptom severity, whether a patient had received a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, and if the patient had a previous history of substance abuse were extracted.

Measures of symptom severity were based on the clinician rated Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale (CGI-S), with seven items assessing the overall severity of a patient’s symptomatology, ranging from one (not at all ill) to seven (extremely ill) (Guy, Citation1976). For the data in the registry, the CGI-S was usually completed by a nurse conducting the registration.

Variables pertaining to aspects of treatment and environmental factors included the specific forensic psychiatric clinic caring for the patient, antipsychotic medication prescribed, and whether forensic psychiatric care was provided in an inpatient or outpatient context. In addition, data was extracted regarding if the patient had an external support person (i.e., a person assigned by the patient advisory board to provide support for the patient, often in the form of accompanying on temporary leaves), and if an inpatient was allowed unsupervised leaves from the forensic mental health clinic.

Data on medication included the names of the pharmaceuticals prescribed to a patient at the time of a registration. However, information on dosages was not available. For the analysis regarding pharmacotherapy, we focused on the number of antipsychotics prescribed and prescription of clozapine and olanzapine, two antipsychotics that have previously been shown to be especially associated with weight gain (Hunt et al., Citation2021) and are commonly used in Swedish forensic psychiatric care (Swedish National Forensic Psychiatric Registry, 2021).

Statistical considerations

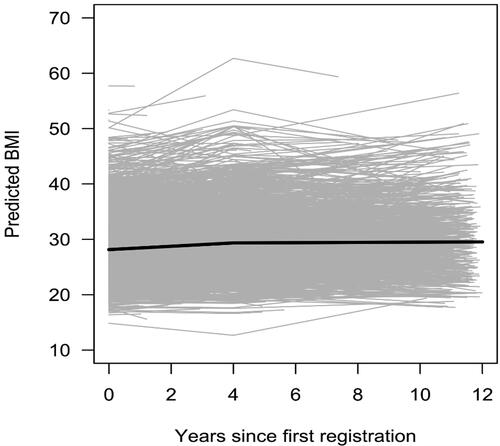

Statistical analyses were mainly conducted with linear and spline (i.e., piecewise/segmented) multilevel regression. In the latter case, a single knot at 4 years after first registration was used, as this gave best fit to data. Multilevel regression was judged to be an appropriate method of analysis due to the hierarchical nature of the data, where longitudinal measurements (level 1) where grouped within patients (level 2). In the analyses including time as a predictor, an individual regression line with an individual intercept (i.e., predicted BMI at first registration) and an individual slope (i.e., predicted change in BMI per year) was estimated for each patient, and the slope was allowed to change at 4 years after first registration. The degree of change in the slope was allowed to differ between patients, in order to maximize fit (see for an illustration). Furthermore, as a multiplicative, rather than additive, change in BMI was judged as more likely, the natural logarithm of BMI was used as the dependent variable. Lastly, the temporal distribution of individual data points was uneven, i.e., annual follow-ups took place at different time-points for individual patients. To exemplify, one patient may have had their first follow-up at 1.2 years after baseline, whilst another patient had their first follow-up at 0.9 years after baseline measurement, and so on. Due to this, it was deemed appropriate to present BMI values as predicted BMI values at year 1, 2 and so on, rather than actual values. Analyses were conducted with R 4.1.3 statistical software (R Core Team, Citation2022) using the lspline (Bojanowski, Citation2017), lmerTest (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, & Christensen, Citation2017), and stringr (Wickham, Citation2022) packages.

Results

General trajectory of weight change over the course of forensic treatment

Across all measurements, the mean BMI for women was 30.81 (SD = 7.84, Mdn = 30.10, Range = 10.0−68.8) while the mean for men was 29.24 (SD = 5.84, Mdn = 28.40, Range = 7.8–76.2). At first registration, mean BMI for women was 29.34 (SD = 7.56, Mdn = 28.35, Range = 14.2–61.7) and mean BMI for men was 28.42 (SD = 5.58, Mdn = 27.70, Range = 7.8−52.6). In the overall sample, BMI increased significantly to year four by approximately 1.1% per year (p < .001, R2 = .005, analysis based on 10,569 observations of 3357 patients). After the fourth year, increase in BMI during subsequent years was no longer significant. The differences in yearly change in BMI during the period before year four and the period from year four and forward was significant (p < .001). BMI increased significantly more in females compared to males across the full time-period [1.1% vs. 0.6% per year, p < .001, ΔR2 = .002 when adding the sex × time interaction effect to a model with only the main effects, analysis based on 16,076 observations of 3388 patients (2510 observations from 548 women and 13,566 observations from 2840 men)]. This effect remained significant when adjusting for the presence of a psychotic disorder (p < .001). See for a summary of BMI increase in the overall sample stratified according to gender and presence of psychotic disorder and for a graphical representation of changes in BMI in the overall sample and individual subjects.

Table 1. BMI over time in males and females, stratified according to the presence or non-presence of a psychotic disorder.

The difference between genders was only marginally significant when the first four years and the time period beyond the fourth year were analyzed separately (1.4% vs. 1% per year, p=.05 for the difference during year 0–4, and 0.5% vs. 0.02% per year, p = .06 for the difference, beyond year four, for women and men respectively). By year four, BMI was predicted to have increased by 1.85 among female and 1.16 among male patients. By year seven, the corresponding values were 2.34 for females and 1.22 for males, respectively.

Among women, BMI was predicted to increase by 0.11%, 1.5%, 2.8%, and 21.4% per year during the first four years of registration for the first, the second, the third, and the fourth quartile, respectively. After year four, changes in the aforementioned quartiles were −0.3%, 0.4%, 1.2%, and 9.0%. Among men, BMI was predicted to increase by 0.2%, 1.0%, 1.8%, and 11.5% per year during the first four years of registration for the first, the second, the third, and the fourth quartile, respectively. After year four, corresponding values were −0.3%, 0.0%, 0.4%, and 5.2%.

Associations to demographical and clinical factors

Age was associated with both BMI at baseline and subsequent increases in BMI. At first registration, an increase in age by one year was associated with an increase in BMI by 0.1% (p < .001, R2 = .006, analysis based on data from 3146 patients). However, the effect of age decreased significantly with time (p < .001, ΔR2 = .004 when adding the age × time interaction effect to a model with only the main effects, analysis based on 16,078 observations of 3389 patients). After five years, an increase in age by one year predicted a decrease in BMI by 0.1%. An increase in age at first registration was associated with a decrease in the BMI-slope during the first four years (p < .001, ΔR2 = .001 when adding the age at first registration × time interaction effect to a model with only the main effects, analysis based on 10,569 observations of 3357 patients). For example, for a patient who was 20 years old at first registration, BMI was predicted to increase by 1.9% per year the first four years, while the same increase for someone who was 50 years old at first registration was predicted to be only 0.5% per year. Age at first registration also had an association, but weaker, with the increase in BMI after the first four years (p < .001, ΔR2 = .004 when adding the age at first registration × time interaction effect to a model with only the main effects, analysis based on 5509 observations of 1501 patients). From year four and onward, BMI was predicted to increase by 0.6% per year for someone who was 20 years old at first registration and to decrease by 0.2% per year for someone who was 50 years old at the first registration.

Patients with a diagnosis of psychotic disorder had on average a BMI 2% higher than those who had never received such a diagnosis (p < .01, R2 = .002, analysis based on 15,806 observations of 3117 patients). The effect of this remained constant over time and did not change with time since the first registration.

When adjusting for dispensations of olanzapine and/or clozapine, the effects of ever being diagnosed with a psychotic disorder was marginally significant (p = .059). If the effect of psychotic disorder was adjusted for the number of antipsychotics prescribed to patients, the difference between the group with a psychotic disorder and those with other forms of pathology ceased to be significant.

Regarding symptom severity, an increase of symptom severity of one on the 7-item CGI-S was associated with a decrease in BMI by 0.4% (p < .001, R2 = .001, analysis based on 16,078 observations of 3,389 patients). However, there was a significant interaction effect with time on this association (p = .015, ΔR2 = .0002 when adding the symptom severity × time interaction effect to a model with only the main effects, analysis based on 16,078 observations of 3389 patients), with the negative association between symptom severity and BMI attenuated by time. Thus, after five-years an increase by one on the CGI predicted a decrease in BMI by 0.1%. The association between symptom severity and BMI remained unchanged when adjusting for the presence of a psychotic disorder.

A previous history of addiction prior to admission to forensic services had no impact on BMI during the course of forensic psychiatric care.

Association to treatment and environmental factors

Taking any antipsychotic medication was associated with 2.1% higher BMI (p < .001, R2 = .003, analysis based on 16,078 observations of 3389 patients). This association was reduced to 1.3% if adjusting for time since first registration but remained significant (p < .001). Time since first registration did not moderate the association between taking any antipsychotic medication and BMI. Pharmacological treatment with either olanzapine or clozapine, rather than some other antipsychotic medication, was not associated with an increase in BMI. Simultaneous treatment with more than one antipsychotic (i.e., antipsychotic polypharmacy), compared with monotherapy, was not associated with an increase in BMI.

Differences between treatment sites were substantial. The unit placement of patients had a significant effect on BMI (p < .001, R2 = .012, analysis based on 16,078 observations of 3389 patients), with a disparity of 20.9% between the clinic with the lowest and highest BMI. This effect remained significant when controlling for possible interregional differences in patient populations and clinical practice; if adjusting for time since first registration and number of antipsychotic medications taken, in addition to presence of psychotic disorders and sex, the disparity remained at a similar level (max difference 21.3%, p < .001).

Unsupervised leave in the context of inpatient forensic care was associated with a marginally significant (p = .06, R2 = .0002, analysis based on 8942 observations of 2706 patients) increase in BMI by 0.59%, but this effect was not significant when adjustments were made for time since first registration.

Having an external support person was associated with an increase in BMI by 1.26% (p < .001, R2 = .0009, analysis based on 16,078 observations of 3389 patients). If adjusting for sex as well and the presence of a psychotic disorder, the effect decreased to 1.24% (p < .001). If adjusting for sex and time since first registration, the effect dropped to 0.93% but remained significant (p < .001).

Being treated in an outpatient care setting was associated with an increase in BMI by 2.12% (p < .001, R2 = .002, analysis based on 15,224 observations of 3350 patients). This effect decreased to 2.09% if adjusting for the presence of a psychotic disorder but remained significant (p < .001). If adjusting for sex as well, the effect remained at 2.09% (p < .001). If adjusting for time since first registration, the effect was reduced to 0.8%, but remained significant (p < .001). For a summary of variables found to be predictive of differences in BMI, see .

Table 2. Summary of factors influencing increases in BMI in forensic psychiatric patients.

Discussion

Our results arguably add further emphasis to the emerging literature demonstrating the need to address somatic health concerns in forensic mental health populations. Both men and women were on average in the WHO overweight category (BMI: 25–30) at baseline, with subsequent weight gain during their time within forensic psychiatric care. Importantly, the degree to which BMI increased varied substantially, with large discrepancies between the third and fourth quartile observed in both men and women, suggesting substantial heterogeneity in trajectories of weight gain.

More pronounced weight gain in females

In agreement with previous studies in forensic psychiatric (Long et al., Citation2014) and prison populations (Herbert et al., Citation2012), our results indicate that females are especially at risk of pronounced weight gain during their time in compulsory forensic care, with women both with and without a psychotic disorder predicted to be obese (BMI > 30) at year seven. Previous interpretations of similar observations in prison populations have suggested that secure environments are especially ill adapted to the somatic health needs of females (e.g., portion sizes and exercise facilities ill-suited to women’s needs) (Herbert et al., Citation2012). However, it should also be noted that females had a higher BMI than males at the first time point in the time series. This deviates from the Swedish general population (Public Health Agency of Sweden, Citation2022) and could be tentatively interpreted as suggestive of differences in the characteristics of female and male forensic patients that could influence the trajectory of BMI in the context of forensic care.

Influence of specific demographical, clinical and environmental factors

Several of the associations observed between BMI and demographical, clinical, environmental and treatment related factors deserve mentioning. In line with what is known regarding weight gain across the lifespan in the general adult population (Chen, Ye, Zhang, Pan, & Pan, Citation2019), there was an inverse relationship between age at admission and subsequent increase in weight during care episodes. Thus, special consideration of the risk of large increases in weight could be warranted in regard to younger patients. Furthermore, antipsychotic medication regimens, rather than whether a person had a psychotic disorder per se, seemed a more determining factor in increases of BMI over time, as the presence of a psychotic disorder exerted no effect on increased BMI over time, when medication regimens were accounted for. In contrast, the effects of being prescribed antipsychotic medication remained significant when controlling for whether the patient had received a psychotic disorder or not.

Regarding the results pertaining to environmental factors, unsupervised leave, receiving care in an outpatient setting and access to an external support person, either seemed to have no effect on BMI when time elapsed was accounted for (unsupervised leave), or was associated to higher BMI-levels (having an external support person, provision of care in an outpatient context). Thus, the findings from this study would suggest that removal of the barriers to an active lifestyle that are inherent in highly restrictive secure inpatient settings do not necessarily entail improvements in metabolic health. The methodology used in the present study preclude any in-depth investigation into the causal mechanisms underpinning the association found between higher BMI and having an external support person or receiving outpatient care. However, one factor that could play a part is a lack of knowledge about healthy habits or lack of motivation to implement such habits. If for instance, fast food is frequently consumed in meetings with an external support person outside the clinic, this could contribute to weight gain. Similarly, patient’s food habits and physical activity habits could deteriorate in an outpatient context, in the absence of the necessary skills or motivation to keep a healthy diet (e.g. cooking skills, knowledge about nutritional components of food items) and adequate physical activity level.

Heterogeneity amongst treatment sites

Interestingly, a large discrepancy was demonstrated in the comparison of the forensic psychiatric clinics with the highest and lowest BMI, respectively. Although no causal inferences can be made, it is notable that this discrepancy was relatively robust when possible confounding from differences in the patient population (i.e., gender, presence of psychotic disorder, time since first registration) and possible differences in pharmacological treatment regimens (number of antipsychotics prescribed) were controlled for. Further research focusing on the factors underpinning such differences would be welcome, as it might generate information that could improve somatic health at treatment sites where current outcomes are unsatisfactory.

Limitations and future research possibilities

One obvious factor limiting the results of the present study is that the observational nature of the research project prevents any causal interpretation of the results. Furthermore, the use of retrospective register data entail data availability issues, limiting the scope of the project. One important aspect of this limitation is the reliance on BMI as an outcome measure in the current study. BMI has been previously critiqued as a poor proxy measure of adiposity, especially in physically active populations (Lessons, Bhakta, & McCarthy, Citation2022; Ode et al., 2007). Other measures such as waist circumference, body fat percentage, assessments of anaerobic capacity, hypertonia and fatty lipids in blood would have allowed more careful investigation of the longitudinal development of the metabolic health of participants in the sample. More detailed information on variables potentially predictive of changes in BMI and other variables related to somatic health would have been desirable. Lastly, it should be emphasized that the transnational generalizability of these results is uncertain. As previously discussed, there are indications that practices in regard to pharmacological treatment of forensic patients differ on the national level. It seems plausible that there are differences in the priority given to somatic health concerns, which could limit the generalizability of the findings in the current study. This point is further emphasized by the rather large differences in BMI observed when controlled comparisons were made between the forensic psychiatric clinics with the highest and lowest BMI-value in this dataset.

Future research in the subject area could focus on large-sample prospective studies with data collected specifically to give an insight into metabolic health (e.g. fatty lipids in blood, waist circumference, hyperglycemia) parameters and factors possibly influencing these, such as for instance medication dosage, cognitive ability, and patient knowledge regarding healthy habits. Qualitative studies could focus on investigating patient’s attitudes toward physical health and their experiences of impediments to a healthy lifestyle. The heterogeneous outcomes observed in comparisons between treatment units at the national level is also deserving of additional research. Studies could be targeted at confirming whether such differences can be observed in intra- and international comparisons and, if such differences are observed, what characterizes treatment settings conducive to good physical health outcomes in forensic mental health patients. Lastly, randomized controlled interventions of both pharmacological and life-style interventions (previously evaluated in non-forensic samples, e.g., Bonfioli, Berti, Goss, Muraro, & Burti, Citation2012; Zheng, Citation2015) seems highly warranted.

Clinical implications

Our data underline the importance of monitoring and addressing the physical health needs of forensic mental health patients. Body weight and cardiometabolic parameters should be carefully and regularly monitored in all patients, especially those receiving antipsychotic medication regardless of diagnosis, sex and age. The substantial heterogeneity observed within the sample, with rapid weight gain in those worst afflicted suggest a need to identify and treat high-risk individuals early in the care process. An increased emphasis on the importance of somatic health concerns in the training of care staff involved in forensic psychiatric care and in officially sanctioned guidelines could be important steps to raise awareness regarding the importance of these issues.

That antipsychotic agents were associated with weight gain regardless of whether an individual had a psychotic disorder or not hold significance, considering that, in the Swedish context, a majority of patients without a psychotic disorder still receive treatment with some sort of antipsychotic agent (Swedish National Forensic Psychiatric Registry, 2021). Taking this into account, it does seem reasonable to carefully monitor and address weight gain in all individuals treated with antipsychotics.

Lastly, simple reliance on the increased opportunity to a more active life-style provided by easing restrictions, such as provision of care in an outpatient context, access to an external support person or unsupervised leave from the ward does not seem to be enough to decrease BMI. Active interventions to promote a healthy life-style (e.g., consultation with a dietician, structured support for physical activity) in conjunction with pharmacotherapy (such as adjunctive treatment with for example metformin) against antipsychotic induced weight gain could be necessary in the clinical management of the physical health needs of forensic mental health patients.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, the present study constitutes a follow-up of BMI trajectories in forensic psychiatric patients with both a substantially larger sample size and a longer follow-up time than previously published work within the field. In conclusion, the current study further underlines concerns regarding weight gain in forensic mental health patients, especially in the case of females. Differences in BMI were large when comparisons adjusted for covariates were made between clinics at the extreme ends of the spectrum, indicating the existence of unknown environmental factors affecting the BMI of subjects studied. Well-designed interventional research evaluating the efficacy of non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment strategies targeting the physical health needs of forensic mental health patients are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the work of the Swedish National Forensic Psychiatric Register and express our gratitude for the assistance received in extracting data for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Data availability statement

The data utilized in the study is available upon request addressed to the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andreasson, H., Nyman, M., Krona, H., Meyer, L., Anckarsäter, H., Nilsson, T., & Hofvander, B. (2014). Predictors of length of stay in forensic psychiatry: The influence of perceived risk of violence. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 37(6), 635–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2014.02.038

- Andiné, P., & Bergman, H. (2019). Focus on brain health to improve care, treatment, and rehabilitation in forensic psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 840–840. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00840

- Bojanowski, M. (2017). lspline: Linear splines with convenient parametrisations. R package version 1.0-0.

- Bondolfi, C., Taffe, P., Augsburger, A., Jaques, C., Malebranche, M., Clair, C., & Bodenmann, P. (2020). Impact of incarceration on cardiovascular disease risk factors: A systematic review and meta-regression on weight and BMI change. BMJ Open, 10(10), e039278–e039278. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039278

- Bonfioli, E., Berti, L., Goss, C., Muraro, F., & Burti, L. (2012). Health promotion lifestyle interventions for weight management in psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 78–78. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-78

- Chen, C., Ye, Y., Zhang, Y., Pan, X.-F., & Pan, A. (2019). Weight change across adulthood in relation to all cause and cause specific mortality: Prospective cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 367, l5584. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l5584

- Dornquast, C., Tomzik, J., Reinhold, T., Walle, M., Mönter, N., & Berghöfer, A. (2017). To what extent are psychiatrists aware of the comorbid somatic illnesses of their patients with serious mental illnesses? A cross-sectional secondary data analysis. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 162–162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2106-6

- Epperson, M. W., Wolff, N., Morgan, R. D., Fisher, W. H., Frueh, B. C., & Huening, J. (2014). Envisioning the next generation of behavioral health and criminal justice interventions. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 37(5), 427–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2014.02.015

- Fernández-Abascal, B., Suárez-Pinilla, P., Cobo-Corrales, C., Crespo-Facorro, B., & Suárez-Pinilla, M. (2021). In- and outpatient lifestyle interventions on diet and exercise and their effect on physical and psychological health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and first episode of psychosis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 125, 535–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.005

- Gaab, S., Brazil, I. A., de Vries, M. G., & Bulten, B. H. (2020). The relationship between treatment alliance, social climate, and treatment readiness in long-term forensic psychiatric care: An explorative study. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 64(9), 1013–1026. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X19899609

- Gebremariam, M. K., Nianogo, R. A., & Arah, O. A. (2018). Weight gain during incarceration: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 19(1), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12622

- Guy, W. (1976). ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised (76–338). US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Publication (ADM). National Institute of Mental Health.

- Hare Duke, L., Furtado, V., Guo, B., & Völlm, B. A. (2018). Long-stay in forensic-psychiatric care in the UK. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(3), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1473-y

- Hayes, J. F., Marston, L., Walters, K., King, M. B., & Osborn, D. P. J. (2017). Mortality gap for people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: UK-based cohort study 2000–2014. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 211(3), 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.117.202606

- Herbert, K., Plugge, E., Foster, C., & Doll, H. (2012). Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in prison populations worldwide: A systematic review. Lancet (London, England), 379(9830), 1975–1982. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60319-5

- Hilton, N. Z., Ham, E., Lang, C., & Harris, G. T. (2015). Weight Gain and its Correlates among Forensic Inpatients. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 60(5), 232–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371506000505

- Hilton, N. Z., Ham, E., Hill, S., Emmanuel, T., & Thege, B. K. (2022). Predictors of weight gain and metabolic indexes among men admitted to forensic psychiatric hospital. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 21(2), 164–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2021.1952356

- Hjorthøj, C., Stürup, A. E., McGrath, J. J., & Nordentoft, M. (2017). Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 4(4), 295–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30078-0

- Hunt, H. J., Donaldson, K., Strem, M., Tudor, I. C., Sweet-Smith, S., & Sidhu, S. (2021). Effect of miricorilant, a selective glucocorticoid receptor modulator, on olanzapine-associated weight gain in healthy subjects: A proof-of-concept study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 41(6), 632–637. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000001470

- Kassi, E., Pervanidou, P., Kaltsas, G., & Chrousos, G. (2011). Metabolic syndrome: Definitions and controversies. BMC Medicine, 9(1), 48–48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-48

- Krishnamoorthy, Y., Rajaa, S., Murali, S., Sahoo, J., & Kar, S. S. (2022). Association between anthropometric risk factors and metabolic syndrome among adults in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Preventing Chronic Disease, 19, 210231. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd19.210231

- Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13

- Laursen, T. M., Nordentoft, M., & Mortensen, P. B. (2014). Excess early mortality in Schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10(1), 425–448. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153

- Lessons, G. R., Bhakta, D., & McCarthy, D. (2022). Development of muscle mass and body fat reference curves for white male UK firefighters. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 95(4), 779–790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01761-4

- Long, C., Rowell, A., Gayton, A., Hodgson, E., & Dolley, O. (2014). Tackling obesity and its complications in secure settings. Mental Health Review Journal, 19(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-04-2013-0012

- Ma, T., Mackinnon, T., & Dean, K. (2021). The prevalence of cardiometabolic disease in people with psychotic disorders in secure settings – A systematic review. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 32(2), 281–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2020.1859588657

- Mitchell, A. J., Vancampfort, D., Sweers, K., van Winkel, R., Yu, W., & De Hert, M. (2013). Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39(2), 306–318. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbr148

- Moss, K., Meurk, C., Steele, M. L., & Heffernan, E. (2022). The physical health and activity of patients under forensic psychiatric care: A scoping review. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 21(2), 194–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2021.1943570

- Nielsen, R. E., Uggerby, A. S., Jensen, S. O. W., & McGrath, J. J. (2013). Increasing mortality gap for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia over the last three decades—A Danish nationwide study from 1980 to 2010. Schizophrenia Research, 146(1-3), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.025

- Nyman, M., Hofvander, B., Nilsson, T., & Wijk, H. (2022). “You Should Just Keep Your Mouth Shut and Do As We Say”: Forensic psychiatric inpatients’ experiences of risk assessments. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 43(2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2021.1956658

- O’Connell, M., Farnworth, L., & Hanson, E. C. (2010). Time use in forensic psychiatry: A naturalistic inquiry into two forensic patients in Australia. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 9(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2010.499558

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. (2022). Övervikt och fetma hos vuxna. Retrieved May 17, 2023, from https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/livsvillkor-levnadsvanor/fysisk-aktivitet-och-matvanor/overvikt-och-fetma/overvikt-och-fetma-hos-vuxna/

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Sagud, M., Mihaljevic Peles, A., & Pivac, N. (2019). Smoking in schizophrenia: Recent findings about an old problem. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 32(5), 402–408. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000529

- SBU. (2018a). Läkemedelsbehandling inom rättspsykiatrisk vård: En systematisk översikt och utvärdering av medicinska, hälsoekonomiska, sociala och etiska aspekter (Drug treatment within forensic psychiatric care: A systematic review and evaluation of medical, health economical, social, and ethical aspects). (SBU-rapport nr 286). Retrieved from Stockholm, Sweden.

- SBU. (2018b). Psykologiska behandlingar och psykosociala insatser i rättspsykiatrisk vård: Systematiska översikter av effektstudier, patientupplevelser och ekonomiska aspekter, samt en etisk analys (Psychological treatment and social support in forensic psychiatric care: A systematic overview of effect studies, patient experiences, economical aspects, and an ethical analysis). (287). Retrieved from Stockholm.

- Senneseth, M., Pollak, C., Urheim, R., Logan, C., & Palmstierna, T. (2021). Personal recovery and its challenges in forensic mental health: Systematic review and thematic synthesis of the qualitative literature. BJPsych Open, 8(1), e17. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1068

- Sturidsson, K., Turtell, I., Tengström, A., Lekander, M., & Levander, M. (2007). Time use in forensic psychiatry: An exploratory study of patients’ time use at a Swedish Forensic Psychiatric Clinic. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 6(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2007.10471251

- Swedish National Forensic Psychiatric Register, RättspsyK. (2021). Annual Report 2021. Swedish National Forensic Psychiatric Register.

- Swildens, W., Termorshuizen, F., de Ridder, A., Smeets, H., & Engelhard, I. M. (2016). Somatic care with a psychotic disorder : Lower somatic health care utilization of patients with a psychotic disorder compared to other patient groups and to controls without a psychiatric diagnosis. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 43(5), 650–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0679-0

- Söderberg, A., Wallinius, M., Munthe, C., Rask, M., & Hörberg, U. (2022). Patients’ experiences of participation in high-security, forensic psychiatric care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 43(7), 683–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2022.2033894

- Tiihonen, J., Lönnqvist, J., Wahlbeck, K., Klaukka, T., Niskanen, L., Tanskanen, A., & Haukka, J. (2009). 11-Year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: A population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). The Lancet (London, England), 374(9690), 620–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60742-X

- Vasic, N., Segmiller, F., Rees, F., Jäger, M., Becker, T., Ormanns, N., Otte, S., Streb, J., & Dudeck, M. (2018). Psychopharmacologic treatment of in-patients with schizophrenia: Comparing forensic and general psychiatry. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 29(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2017.1332773

- Walker, E. R., McGee, R. E., & Druss, B. G. (2015). Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(4), 334–341. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502

- Whitaker, R. (2020). Viewpoint: Do antipsychotics protect against early death? A critical view. Psychological Medicine, 50(16), 2643–2652. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000358X

- WHO. (2021). Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) Factsheet. Published 11th of June 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

- Wickham, H. (2022). stringr: Simple, Consistent Wrappers for Common String Operations. http://stringr.tidyverse.org, https://github.com/tidyverse/stringr

- Zheng, W., Li, X.-B., Tang, Y.-L., Xiang, Y.-Q., Wang, C.-Y., & de Leon, J. (2015). Metformin for weight gain and metabolic abnormalities associated with antipsychotic treatment: Meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 35(5), 499–509. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000392