ABSTRACT

Second-home tourism is a prominent feature of Nordic tourism. This article reviews Nordic research on second-home tourism since 2000 and relates it to international trends within this field. Furthermore, it provides a short outline of future research needs and opportunities. The review indicates that Nordic second-home tourism research has been highly productive and influential. After being dominated by national overviews, research has more recently addressed issues such as environmental impacts, community tensions and displacement, internationalization, and planning. Indeed, with this, Nordic researchers have gained core positions in the international ecosystem of second-home research, and particularly Umeå University has developed into the epicenter of second-home research. Although the situation for Nordic second-home research has been strong, generational shifts imply a risk of discontinuation. However, a more nuanced view on the second-home phenomenon detects the varieties of second-home tourism and the multiple interconnections to other fields of research. Against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, second-home research can become a forerunner in understanding households’ new spatial–temporal arrangements, combining various homes and places.

Introduction

Not surprisingly, the King of Sweden retreated to one of his rural mansions with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic. While this was accepted as a reasonable move, many other households in the Nordic countries did not receive a warm welcome when mimicking the royal decision. Indeed, second homes are an important part of many Nordic households’ everyday life, but they are so self-evident and mundane that they seldom trigger any greater interest. Now, however, the multiple roles of second homes became visible. They were debated as a rural refuge for their owners, as a threat to rural health and healthcare, and as an important contributor to local retail and service. However, the overwhelming impression was how little local jurisdictions were informed about the presence and volume of second-home owners, even though academic knowledge about second-home tourism is good and well developed.

Without doubt, research on second homes is a stronghold of Nordic tourism research and, indeed, Nordic second-home researchers dominate the global scientific discourse (Müller & Hall, Citation2018). This is because of the long tradition of second-home tourism and the high absolute and relative numbers of second homes in the Nordic countries, together triggering scientific interest as well (Marjavaara et al., Citation2019; Müller, Citation2007). Hence, this review does not aim to provide a complete picture of Nordic second-home research but rather to highlight some of the topics and trends in the 21st millennium, also in relation to the global development.

Current state of second-home tourism research in a Nordic context

In its first 20 years, the Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism published two special issues on the topic of second-home tourism, and with altogether 12 articles the journal has been the most prominent outlet for second-home research globally. This core role also mirrors the dominant position of Nordic second-home research in the world. Between 2001 and 2020, the bibliometric database Scopus registered 295 contributions on second homes, covering articles, book chapters, and books.Footnote1 Of these, 78 (26.4%) had authors affiliated with Nordic universities. A majority (38 entries) were from Sweden, while 23 were from Finland, 16 from Norway, six from Denmark, and two from Iceland. Nordic second-home research holds a protagonist role within the field, and many important publications are published from Nordic universities.

Even though most of the development can be localized to the period since 2000, there have been important antecedents prior to the new millennium (Marjavaara et al., Citation2019). For example, in Sweden, four PhD theses focused on second homes and rural development: Aldskogius (Citation1968) addressed the evolution of second homes in the Siljan area, while Bohlin (Citation1982) studied second homes’ economic impacts in relation to their locations; and during the 1990s, Nordin (Citation1997) assessed the role of second homes in relation to rural development while Müller (Citation1999) analyzed various aspects of the increasing German second-home ownership after Sweden’s entry into the European Union.

Nordic second-home tourism research has been reviewed several times during SJHT’s 20 years. Both special issues were introduced with reviews (Müller, Citation2007, Citation2013), and recently a comprehensive review on second-home tourism research in Sweden was also published (Marjavaara et al., Citation2019). In order to provide a systematic overview here, the Scopus dataset mentioned above was used in order to visualize the topics covered by the Nordic research community.

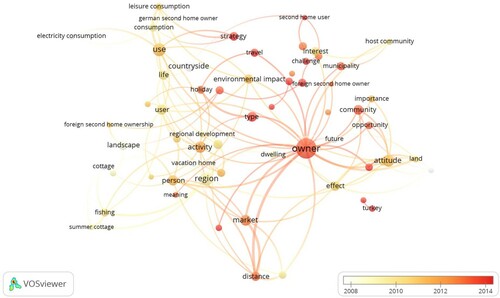

illustrates the frequency of certain terms in the titles and abstracts of the items covered in the database. Furthermore, co-occurrences are indicated by the links between the different keywords, while the average years of the keywords’ occurrence are shown by the shading of the circles, with darker shading representing more recent topics. Accordingly, the figure indicates that second-home research has started focusing on second homes as a phenomenon of consumption. A stress on rural areas, use patterns, activities, and the impact of second-home tourism can be detected as well. This greatly mirrors a need at the time to rediscover a research topic that for various reasons had disappeared from the research agenda for quite a while until the 1990s. Hence, several publications had provided national overviews more or less mapping geographical distributions and use patterns, sometimes however addressing specific aspects such as seasonal population distributions (Adamiak et al., Citation2017; Hiltunen, Citation2007; Hiltunen & Rehunen, Citation2014; Marjavaara & Müller, Citation2007; Müller, Citation2002b, Citation2004, Citation2006; Müller & Hall, Citation2003; Nouza et al., Citation2013; Overvåg, Citation2009; Vittersø, Citation2007). Many of these contributions detected the volume of the phenomenon and engaged in assessing various impacts. In this context, the importance of the second homes for national identity was also highlighted (Pitkänen, Citation2008, Citation2011; Vepsäläinen & Pitkänen, Citation2010).

Figure 1. Topics of Nordic second-home tourism research 2001–2019, overlaid with average time of their occurrences (Source: Scopus).

An important reason for the rejuvenation of second-home research in the Nordic countries is these countries’ membership and association with the European Union, which eroded the restrictions for foreign second-home purchases during the 1990s. While this entailed concerns over displacement (Pitkänen, Citation2008), Müller (Citation1999, Citation2002a) showed that German second-home owners in Sweden indeed demanded property in areas that were not popular among Swedish second-home owners. Hannonen (Citation2017) picked the topic up in relation to Russian second-home owners in Finland, who were looking for safe investment opportunities and a more relaxed lifestyle. In the context, borders were not seen as barriers but rather opened up recreational opportunities that were not available or affordable in the home country (Hannonen et al., Citation2015; Müller, Citation2011b). Recently, even outgoing second-home ownership has become a topic of interest for Nordic researchers (Abbasian, Citation2018; Abbasian & Müller, Citation2019; Jacobsen et al., Citation2009).

The perception of second-home ownership among second-home owners and rural residents and their mutual relation is another topic that has engaged Nordic researchers (Farstad & Rye, Citation2013; Rye, Citation2011; Rye & Gunnerud Berg, Citation2011; Tjørve et al., Citation2013; Tuulentie, Citation2007). Indeed, it has been shown that the social distance between local population and second-home owners was very short, and that the two groups shared values and ideas regarding rural development. Still, while the increasing interest in rural second homes was expected to also cause displacement, Marjavaara (Citation2007, Citation2009) revealed that second-home owners had not displaced any rural residents. Instead, they were used as scapegoats to explain rural decline. Nordic research has also demonstrated that second-home owners contributed, sometimes highly practically, to reviving and supporting rural communities (Larsson & Müller, Citation2019). This comprised engagement in local associations, businesses, community life, and neighborhood relations (Flognfeldt, Citation2006; Huijbens, Citation2012; Nordin & Marjavaara, Citation2012; Robertsson & Marjavaara, Citation2015).

Another interest has involved issues of community and planning. Overvåg (Citation2010) argued that second homes were a factor in re-resourcing rural areas, but it often seemed that these homes were rather ignored in spatial planning (Back, Citation2020; Rinne et al., Citation2014). Instead, Persson (Citation2015) demonstrated the difficulties in upholding a clear distinction between permanent and secondary houses. Research made it clear that second homes are an integrated part of mobile societies, challenging the taken-for-granted dichotomies of tourism/migration and home/away (Ellingsen, Citation2017; Hidle et al., Citation2010; Marjavaara & Lundholm, Citation2016; Overvåg, Citation2011). However, second-home owners do not have clear channels for participating in local communities (Rinne et al., Citation2015). Instead, they are often perceived as challenges for local planning (Slätmo et al., Citation2019).

Another topic involves the environmental impacts of second homes. It is sometimes argued that domestic second-home tourism is a substitute for long-haul travel, but Nordic research indicates that second-home owners are often highly mobile and thus their overall consumption patterns do not allow for simplified conclusions (Adamiak et al., Citation2016; Hiltunen, Citation2007).

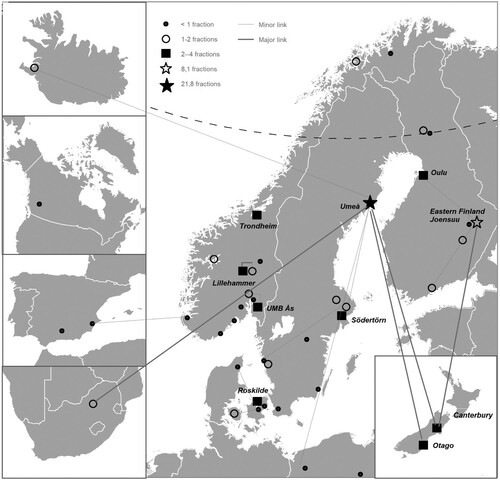

From an institutional point of view, it is no secret that Umeå University and its Department of Geography is the epicenter of Nordic (and indeed global) second-home research. The Department is involved in 32 of the Nordic publications on second-home tourism, and over the years its researchers have published numerous articles, book chapters, and books on the topic (e.g. Hall & Müller, Citation2004, Citation2018; Marjavaara, Citation2008; Müller, Citation1999). Another important node for second-home research during the covered time period was the Center of Tourism Research in Savonlinna, and then after its discontinuation, the University of Eastern Finland in Joensuu (e.g. Adamiak et al., Citation2015). Indeed, there has been post-doc mobility between the units in both directions and, furthermore, both the Umeå group and the Savonlinna group cooperated with C. M. Hall at the University of Otago and later the University of Canterbury, New Zealand. In Norway, the local university college in Lillehammer, the Eastern Norway Research Institute (ENRI), as well as the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA), have run projects on second homes, as has NTNU in Trondheim in cooperation with the Norwegian Center for Rural Research. In addition, many more researchers at Nordic universities and research centers have engaged in research related to second homes (). However, the research output has often been limited to limited case studies.

Nordic and international research on second-home tourism

Although second homes have long been a research topic, the first comprehensive review of second-home tourism was not published until the 1970s (Coppock, Citation1977). Based on a conference on second homes and recent land-use conflicts in the British countryside, the book gathered a number of case studies from all over the world. A common denominator was that the contributors defined second homes at best as “inessential” (Wolfe, Citation1977) but often, albeit not exclusively, as a threat to the rural idyll and the social fabric of the countryside (Müller & Hoogendoorn, Citation2013). This perspective has prevailed in rural research and in the UK, while more recent approaches have also highlighted the benefits of second-home tourism for rural economies and communities (Müller, Citation2011a).

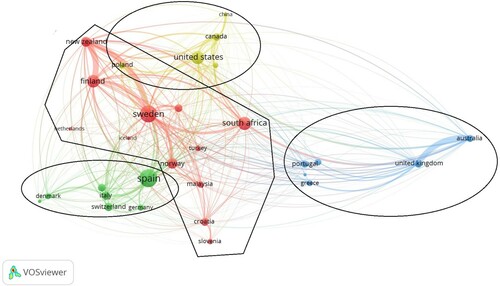

Tourism researchers have dominated the rejuvenation of second-home research since the late 1990s, and particularly Nordic researchers have taken a leading position in the field. As reveals, the Nordic countries (with the exception of Denmark) together – along with New Zealand and South Africa, among others – form the major cluster of second-home research, as they share many references. The second cluster is dominated by Spain, also containing France and Italy but also Denmark. The third cluster is dominated by North America, and the fourth by the UK and Australia. Overall, as the links indicate, publications share quite a number of references even between the clusters. But the particular and somewhat marginal situation of the fourth cluster containing the UK demonstrates the special situation there (e.g. Gallent et al., Citation2005), where uneven land ownership patterns imply that second homes remain a contested issue (Paris, Citation2010).

Figure 3. Bibliographic country clusters of second-home research, based on the extent shared references (Source: Scopus).

As indicated earlier, global second-home research addresses issues similar to those known from the Nordic countries. Thus, Nordic researchers dominate global compilations of second-home research as well (e.g. Hall & Müller, Citation2004, Citation2018; Roca, Citation2013). However, there are also differences. While research in the Nordic countries has seen second homes mainly in a rural context and also in relation to mobility issues, global research tends to see them more within a tourism industry context and in relation to urban areas or resort towns. This applies particularly to what is labeled “residential tourism”. Furthermore, economic aspects are far more prominent globally than in the Nordic context.

Global research interest in second homes is on the rise, and studies can be found from countries such as Iran, Malaysia, and Costa Rica (Müller & Hall, Citation2018).

The future of second-home tourism research

Although second-home research in the Nordic countries has a strong tradition, more recently, research efforts in the field have been more limited. This is because several of the PhD projects that have contributed to creating the impressive volume of Nordic tourism research have come to an end (e.g. Marjavaara, Pitkänen, Overvåg, Farstad, Hannonen), and not all of the researchers have continued along their earlier paths.

Still, the need and opportunities for second-home research in a Nordic context have not declined. Departing from the categorization by Müller et al. (Citation2004) of second-home landscapes, Back and Marjavaara (Citation2017) have opened up new avenues for second-home research, noting the varieties of mobilities and related impacts contained in the overall practice of second-home tourism. Hence, the geography of second homes at mountain or seaside resorts certainly differs from second-home geographies on the urban fringe, when it comes to use patterns, consequences for property markets, and community relations. In an international context, these differences have been acknowledged by applying a different label – “residential tourism” – referring not least to the second-home practices of Northern retirees in the South (Müller & Hall, Citation2018).

However, many of these geographies have not been addressed properly in their own right. There is certainly reason to engage in assessing second homes in their geographical contexts. This applies not least to urban second homes, which research has largely neglected, particularly in a Nordic context. Furthermore, economic aspects of second-home tourism have not been properly scrutinized for quite a while, and the impact of second-home tourism on property markets and national economies is poorly understood. Similar claims can be made regarding the nexus of demographical development and second homes. Big data covering second-home owners’ mobilities, expenses, and experiences further opens up for new, exciting research opportunities. Furthermore, commercial use of second homes and new forms of second-home tourism, such as home exchange, have not been sufficiently addressed (Casado-Díaz et al., Citation2020).

Moreover, the recent COVID-19 pandemic has entailed new and somewhat unexpected attention to second homes. Partly, travel restrictions have rejuvenated the interest in second homes as they provide an opportunity for close-to-home tourism, which also aligns with concerns regarding the impact of travel on climate change. Partly, the situation has triggered pertinent questions concerning what home and away are in modern society and who has the right to be in what place at what time and for what reasons. The pandemic has manifested that online work from home offices can serve as a substitute for, or at least supplement, traditional work patterns for an increasing number of people. This insight opens up new opportunities to utilize second homes, and may indeed entail a step toward a truly multilocal and mobile society. Second-home research can be a forerunner in understanding such new spatial–temporal arrangements, particularly as much of social science remains rooted in approaches favoring sedentarism over mobility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The search string used was as follows: TITLE-ABS-KEY(“second home” AND tourism) AND (EXCLUDE (SRCTYPE, “p”)) AND (EXCLUDE (DOCTYPE, “cp”) OR EXCLUDE (DOCTYPE, “no”) OR EXCLUDE (DOCTYPE, “le”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR,2019) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2018) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2017) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2016) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2015) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2014) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2013) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2012) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2011) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2010) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2009) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2008) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2007) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2006) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2005) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2004) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2003) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2002) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2001)). Limitations of the applied methodology relate to the dominance of English-speaking literature in the Scopus database and the possible use of alternative terminology that may dismiss certain entries. However, the sample is broad, and not all items covered a focus on second homes exclusively. Rather, second homes are an important aspect of the items included.

References

- Abbasian, S. (2018). Political crises and destination choice: An exploratory study of Swedish-Iranian second-home buyers. Tourism, Culture & Communication, 18(3), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.3727/109830418X15319363084481

- Abbasian, S., & Müller, D. (2019). Displaced diaspora second-home tourism: An explorative study of Swedish-Iranians and their second-home purchases in Turkey. Tourism, 67(3), 239–252.

- Adamiak, C., Hall, C. M., Hiltunen, M. J., & Pitkänen, K. (2016). Substitute or addition to hypermobile lifestyles? Second home mobility and Finnish CO2 emissions. Tourism Geographies, 18(2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2016.1145250

- Adamiak, C., Pitkänen, K., & Lehtonen, O. (2017). Seasonal residence and counterurbanization: The role of second homes in population redistribution in Finland. GeoJournal, 82(5), 1035–1050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-016-9727-x

- Adamiak, C., Vepsäläinen, M., Strandell, A., Hiltunen, M. J., Pitkänen, K., Hall, C. M., Rinne, J., Hannonen, O., Paloniemi, R., & Åkerlund, U. (2015). Second home tourism in Finland. SYKE & University of Eastern Finland.

- Aldskogius, H. (1968). Studier i siljanområdets fritidshusbebyggelse. Kulturgeografiska institutionen.

- Back, A. (2020). Temporary resident evil? Managing diverse impacts of second-home tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(11), 1328–1342. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1622656

- Back, A., & Marjavaara, R. (2017). Mapping an invisible population: The uneven geography of second-home tourism. Tourism Geographies, 19(4), 595–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1331260

- Bohlin, M. (1982). Spatial economics of second homes: A review of a Canadian and a Swedish case study. Kulturgeografiska institutionen.

- Casado-Díaz, M. A., Casado-Díaz, A. B., & Hoogendoorn, G. (2020). The home exchange phenomenon in the sharing economy: A research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(3), 268–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2019.1708455

- Coppock, J. T. (Ed.). (1977). Second homes: Curse or blessing? Pergamon.

- Ellingsen, W. (2017). Rural second homes: A narrative of de-centralisation. Sociologia Ruralis, 57(2), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12130

- Farstad, M., & Rye, J. F. (2013). Second home owners, locals and their perspectives on rural development. Journal of Rural Studies, 30(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.11.007

- Flognfeldt, T., Jr. (2006). Second homes, work commuting and amenity migrants in Norway’s mountain areas. In L. A. Moss (Ed.), The amenity migrants: Seeking and sustaining mountains and their cultures (pp. 232–244). Cabi.

- Gallent, N., Mace, A., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2005). Second homes: European perspectives and UK policies. Avebury: Ashgate.

- Hall, C. M., & Müller, D. K. (Eds.). (2004). Tourism, mobility, and second homes: Between elite landscape and common ground. Channel View Publications.

- Hall, C. M., & Müller, D. K. (Eds.). (2018). The Routledge handbook of second home tourism and mobilities. Routledge.

- Hannonen, O. (2017). Peace and quiet beyond the border: The trans-border mobility of Russian second home owners in Finland. Matkailututkimus, 13(1-2), 95–99.

- Hannonen, O., Tuulentie, S., & Pitkänen, K. (2015). Borders and second home tourism: Norwegian and Russian second home owners in Finnish border areas. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 30(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2015.1012736

- Hidle, K., Ellingsen, W., & Cruickshank, J. (2010). Political conceptions of second home mobility. Sociologia Ruralis, 50(2), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2010.00508.x

- Hiltunen, M. J. (2007). Environmental impacts of rural second home tourism – case Lake District in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(3), 243–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701312335

- Hiltunen, M. J., & Rehunen, A. (2014). Second home mobility in Finland: Patterns, practices and relations of leisure oriented mobile lifestyle. Fennia – International Journal of Geography, 192(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.11143/8384

- Huijbens, E. H. (2012). Sustaining a village’s social fabric? Sociologia Ruralis, 52(3), 332–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2012.00565.x

- Jacobsen, J. K. S., Selstad, L., & Nogués Pedregal, A. M. (2009). Introverts abroad? Long-term visitors’ adaptations to the multicultural tourism context of Costa Blanca, Spain. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 7(3), 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766820903259501

- Larsson, L., & Müller, D. K. (2019). Coping with second home tourism: Responses and strategies of private and public service providers in western Sweden. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(16), 1958–1974. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1411339

- Marjavaara, R. (2007). The displacement myth: Second home tourism in the Stockholm archipelago. Tourism Geographies, 9(3), 296–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680701422848

- Marjavaara, R. (2008). Second home tourism: The root to displacement in Sweden? Umeå University.

- Marjavaara, R. (2009). An inquiry into second-home-induced displacement. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 6(3), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790530903363373

- Marjavaara, R., & Lundholm, E. (2016). Does second-home ownership trigger migration in later life? Population, Space and Place, 22(3), 228–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1880

- Marjavaara, R., & Müller, D. K. (2007). The development of second homes’ assessed property values in Sweden 1991–2001. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(3), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250601160305

- Marjavaara, R., Müller, D. K., & Back, A. (2019). Från sommarnöje till Airbnb: En översikt av svensk fritidshusforskning. Ymer, 139, 53–77.

- Müller, D. K. (1999). German second home owners in the Swedish countryside. Umeå University.

- Müller, D. K. (2002a). Reinventing the countryside: German second-home owners in Southern Sweden. Current Issues in Tourism, 5(5), 426–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500208667933

- Müller, D. K. (2002b). Second home ownership and sustainable development in Northern Sweden. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3(4), 343–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/146735840200300406

- Müller, D. K. (2004). Second homes in Sweden: Patterns and issues. In C. M. Hall & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Tourism, mobility and second homes: Between elite landscape and common ground (pp. 244–258). Channel View.

- Müller, D. K. (2006). The attractiveness of second home areas in Sweden: A quantitative analysis. Current Issues in Tourism, 9(4-5), 335–350. https://doi.org/10.2167/cit269.0

- Müller, D. K. (2007). Second homes in the Nordic countries: Between common heritage and exclusive commodity. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(3), 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701300272

- Müller, D. K. (2011a). Second homes in rural areas: Reflections on a troubled history. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 65(3), 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2011.597872

- Müller, D. K. (2011b). The internationalization of rural municipalities: Norwegian second home owners in Northern Bohuslän, Sweden. Tourism Planning & Development, 8(4), 433–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2011.605384

- Müller, D. K. (2013). Progressing second home research: A Nordic perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 13(4), 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2013.866303

- Müller, D. K., & Hall, C. M. (2003). Second homes and regional population distribution: On administrative practices and failures in Sweden. Espace, Populations, Sociétés, 21(2), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.3406/espos.2003.2079

- Müller, D. K., & Hall, C. M. (2018). Second home tourism: An introduction. In C. M. Hall & D. K. Müller (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second home tourism and mobilities (pp. 3–14). Routledge.

- Müller, D. K., Hall, C. M., & Keen, D. (2004). Second home tourism impact, planning and management. In C. M. Hall & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Tourism, mobility and second homes: Between elite landscape and common ground (pp. 15–32). Channel View.

- Müller, D. K., & Hoogendoorn, G. (2013). Second homes: Curse or blessing? A review 36 years later. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 13(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2013.860306

- Nordin, U. (1997). Skärgården i storstadens skugga. Stockholms Universitet.

- Nordin, U., & Marjavaara, R. (2012). The local non-locals: Second home owners associational engagement in Sweden. Tourism, 60(3), 293–305.

- Nouza, M., Ólafsdóttir, R., & Müller, D. K. (2013). A new approach to spatial–temporal development of second homes: Case study from Iceland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 13(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2013.764512

- Overvåg, K. (2009). Second homes and urban growth in the Oslo area, Norway. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 63(3), 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291950903238974

- Overvåg, K. (2010). Second homes and maximum yield in marginal land: The re-resourcing of rural land in Norway. European Urban and Regional Studies, 17(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776409350690

- Overvåg, K. (2011). Second homes: Migration or circulation? Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift, 65(3), 154–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2011.598237

- Paris, C. (2010). Affluence, mobility and second home ownership. Routledge.

- Persson, I. (2015). Second homes, legal framework and planning practice according to environmental sustainability in coastal areas: The Swedish setting. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 7(1), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2014.933228

- Pitkänen, K. (2008). Second-home landscape: The meaning(s) of landscape for second-home tourism in Finnish Lakeland. Tourism Geographies, 10(2), 169–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680802000014

- Pitkänen, K. (2011). Contested cottage landscapes: Host perspective to the increase of foreign second home ownership in Finland 1990–2008. Fennia, 189(1), 43–59.

- Rinne, J., Kietäväinen, A., Tuulentie, S., & Paloniemi, R. (2014). Governing second homes: A study of policy coherence of four policy areas in Finland. Tourism Review International, 18(3), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427214X14101901317318

- Rinne, J., Paloniemi, R., Tuulentie, S., & Kietäväinen, A. (2015). Participation of second-home users in local planning and decision-making – A study of three cottage-rich locations in Finland. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 7(1), 98–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2014.909818

- Robertsson, L., & Marjavaara, R. (2015). The seasonal buzz: Knowledge transfer in a temporary setting. Tourism Planning & Development, 12(3), 251–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2014.947437

- Roca, Z. (Ed.). (2013). Second home tourism in Europe: Lifestyle issues and policy responses. Ashgate.

- Rye, J. F. (2011). Conflicts and contestations: Rural populations’ perspectives on the second homes phenomenon. Journal of Rural Studies, 27(3), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2011.03.005

- Rye, J. F., & Gunnerud Berg, N. (2011). The second home phenomenon and Norwegian rurality. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 65(3), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2011.597873

- Slätmo, E., Ormstrup Vestergård, L., Lidmo, J., & Turunen, E. (2019). Urban-rural flows from seasonal tourism and second homes: Planning challenges and strategies in the Nordics (NORDREGIO report 2019:13). Nordregio. https://doi.org/10.6027/R2019:13.1403-2503

- Tjørve, E., Flognfeldt, T., & Tjørve, K. M. C. (2013). The effects of distance and belonging on second-home markets. Tourism Geographies, 15(2), 268–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2012.726264

- Tuulentie, S. (2007). Settled tourists: Second homes as a part of tourist life stories. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(3), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701300249

- Vepsäläinen, M., & Pitkänen, K. (2010). Second home countryside: Representations of the rural in Finnish popular discourses. Journal of Rural Studies, 26(2), 194–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2009.07.002

- Vittersø, G. (2007). Norwegian cabin life in transition. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(3), 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701300223

- Wolfe, R. I. (1977). Summer cottages in Ontario: Purpose-built for an inessential purpose. In J. T. Coppock (Ed.), Second homes: Curse or blessing? (pp. 17–34). Pergamon.