ABSTRACT

The article addresses the broader relationships between seaweed and algae as a marine resource, destination development, and sustainability. In many European countries, an industry around seaweed has emerged, ranging from high-end restaurants that provide their customers with local, seasonal and sustainable ingredients, to entrepreneurs offering “harvest your own seaweed”-tours. In this explorative study, we focus on different ways of experiencing this marine resource in a Swedish context, to better understand its economic and social potential. Taking a consumer perspective, we investigate through an online questionnaire and reviews from an online consumer-to-consumer travel-planning portal how seaweed and algae are validated. By exploring people's notions, the aim is to understand the potential and value of this marine resource better. Where is seaweed encountered and enjoyed? How is it used? What is experienced to be valuable about this resource? We identify possibilities for utilizing algae and seaweed in order to foster future business opportunities for local communities, as well as to integrate the resource more in our society. We show how algae and seaweed are experienced in diverse settings and dimensions, such as at home, while being a tourist, as part of everyday life, as a special treat, within nature, and as food.

Introduction

"Our seaweed has ended up on the plates at restaurant[s] vRÅ, TAK, Volt, Gastrologik, Agrikultur, Esperanto, Chef of the Year contest, Bocuse dÓr and others. We have made our own seaweed products, such as spices, salt, a book, posters, dried seaweed. We have had courses and experiences for dreamers and skeptics, children and researchers, people near and far in how to harvest sustainably and use seaweed in cooking." (Catxalot AB, Citation2020)

The marine environment has an important role to play in the changeover to a green economy due to new and expanded cultivation spaces (cf. Hasselstrom et al., Citation2018; WWF Baltic Ecoregion Programme, Citation2015). Since fish is becoming a scarce resource the way forward for traditional fishers in the Nordic countries might be to specialize into new products. It is suggested that the fisheries have to take a more business-driven initiative to be able to survive (Hultman et al., Citation2018). Harvesting or cultivating algae for consumption could signify a possibility for traditional fisheries to diversify.

Lately, there has been an increasing interest for algae as a sustainable, new resource for human food in Europe and the Western world (cf. Birch et al., Citation2019; Bouga & Combet, Citation2015; Chapman et al., Citation2015; Gundersen et al., Citation2017; Heldmark, Citation2018; Kraan, Citation2020; Romare, Citation2018). New markets and industries have emerged, from the cultivation, to entrepreneurs offering cooking workshops and “harvest your own seaweed”-tours (Näslund, Citation2020). How can we understand this transformation from a marine resource into a smart and wild crafted cuisine?

Seaweed is a contradictory phenomenon and is described as healthy and useful, but also as dirty and toxic (Bouga & Combet, Citation2015; Fleurence et al., Citation2012; Fredriksson & Säwe, Citation2020; Holdt & Kraan, Citation2011). Like other natural resources, it has the ability to organize culture and society (Douglas, Citation1975; Kaufmann, Citation2010).

In Europe, the interest in consuming seaweeds is increasing and nutritional and health benefits seem to have engaged early adopter consumer groups (Mouritsen et al., Citation2019). Researchers have also started to look into potential consumers of seaweed (Birch et al., Citation2019; Palmieri & Forleo, Citation2020; Wendin & Undeland, Citation2020). However, empirical studies on the consumption of algae in Europe are rare, and how Western consumers think about seaweed is still largely uninvestigated (Birch et al., Citation2019). In this explorative study, we focus on diverse ways of experiencing algae from a consumer perspective. Where is seaweed encountered and enjoyed? How is it used? What is experienced to be valuable about this resource? By exploring seaweed experiences in different settings, the aim is to understand the potential and value of algae. Investigating people's notions can support the identification of future business opportunities related to algae for local communities, as well as help to identify ways of integrating the resource more in our society. By increasing the consumption of ecologically and locally produced algae in Western societies, a societal transition towards sustainability could be aided, due to the inclusion of a (so far) under-used natural resource. We take our empirical starting point in a questionnaire, followed by seaweed experiences that are created, described and shared on an online travel-planning portal.

Coastal tourism and seaweed

Within the field of contemporary global tourism, marine and coastal tourism are among the fastest-growing areas (Chen, Citation2010; Gundersen et al., Citation2017; Hall, Citation2001; Honey & Krantz, Citation2007; Miller, Citation1993; Orams & Lück, Citation2014; Papageorgiou, Citation2016; Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2020). According to Hall, coastal tourism can be understood as “the full range of tourism, leisure, and recreationally oriented activities that take place in the coastal zone and the offshore coastal waters” (Hall, Citation2001, p. 602). In Scandinavia, the coastal ecosystems are used as a recreational area for diverse activities by tourists and locals (Gundersen et al., Citation2017). Many cities are located on the coast and offer diverse possibilities for marine-related recreation. During the last years, tourism and recreational activities taking place in a marine environment have been growing in Sweden (Hasler et al., Citation2016; SwAM, Citation2012), and visits to the sea are a common leisure time activity for many Swedes (SwAM, Citation2012).

Seaweed and kelp forests are important for local economies and ecotourism activities such as wildlife watching, fishing, kayaking, snorkeling, and scuba diving (cf. Gundersen et al., Citation2017). Kelp forests along the coasts and their biodiversity are important fish habitants, and for example divers enjoy the rich underwater scenery (Gundersen et al., Citation2017; Hasler et al., Citation2016). In Sweden, the water quality is perceived very positive (Hasler et al., Citation2016) and together with healthy underwater landscapes this presents a valuable context for promoting ecotourism activities, with a focus on the environment and sustainability (Chen, Citation2010; Fairweather et al., Citation2005; Johnson et al., Citation2019). Moreover, marine ecotourism is a relatively recent and growing phenomenon, whereby the environmental educational aspect as well as the low environmental impact of these recreational activities are central (Johnson et al., Citation2019). This can already be seen in Sweden, where environmentally sustainable, knowledge creating seaweed activities for tourists are offered.

Experiencing seaweed in a tourism context could provide valuable business options for local communities. Tourism represents a major economic activity at the seaside and generates local employment opportunities (Gundersen et al., Citation2017; Hasler et al., Citation2016; Papageorgiou, Citation2016). For the Nordic countries, this could offer a possibility to diversify traditional small-scale fisheries, as a means to generate employment and income through new products and services (cf. Chen, Citation2010; Hultman et al., Citation2018; Orams & Lück, Citation2014). However, innovative entrepreneurial initiatives and transitions of fisheries into the coastal tourism sector have proven challenging (Hultman et al., Citation2018; Johnson et al., Citation2019; Orams & Lück, Citation2014). Many traditional fishers seem to have difficulties in appreciating and comprehending the rationale behind this new transformational cross-sectoral agenda. Although various studies highlight the opportunities for small entrepreneurial endeavours resulting from a diverse algae industry (FAO, Citation2018; Kraan, Citation2020; Rebours et al., Citation2014), research in a European context seems scarce. The valuation of marine ecosystems and the value to local communities needs to be studied further (Gundersen et al., Citation2017).

Food tourism and seaweed

In the tourists' experience food consumption is significant, which also manifests itself in a growing body of research around food-, culinary, and gastronomic tourism (Björk et al., Citation2014; Everett, Citation2016; Hall & Mitchell, Citation2005; Hall & Sharples, Citation2004; Mkono, Citation2011; Richards, Citation2003; Vu et al., Citation2019). Food organizes many tourist experiences, since tourists typically spend a substantial part of their time considering what and where to eat and drink, as well as actually consuming it (Richards, Citation2003).

The interest about food in culinary or gastronomic tourism reflects a tangible expression of a curiosity about the cultural and natural surroundings producing them (Hall & Mitchell, Citation2005). The food itself may or may not be the major motivating factor for the travel, rather it can be considered as part of the tourism experience and the setting / location (Hall & Mitchell, Citation2005; Hall & Sharples, Citation2004).

Tourists can be more curious and open towards experiencing the new than in their everyday life (Long, Citation2004; Mkono, Citation2011) and they seek out “new foods and consumption experiences” (Cleave, Citation2013, p. 157). The perception of what is new and unfamiliar shifts with experience and what might have started as a curious food exploration while travelling can be incorporated into everyday taste habits (Long, Citation2004). Newly experienced foods on travels might become part of people's leisure time at home, and thereby support a certain lifestyle (Richards, Citation2003). The consumption of algae during a vacation could contribute to changing everyday customs.

Moreover, the border between tourism and the everyday becomes blurred when activities such as shopping for ingredients on a market are taking place at tourism settings (Long, Citation2004). This can be seen especially in food, since food is required all the time, while being on a trip or not, and food products are often brought home as a souvenir or other kind of remembrance (Everett, Citation2016; Hall & Mitchell, Citation2005; Stone et al., Citation2018). Being a culinary tourist can not only span food activities while travelling, the concept can even be extended to the home while enjoying “mental and emotional journeys to other food worlds” (Long, Citation2004, p. 23) through for example browsing cookbooks or reading restaurant reviews. It has also been shown that future purchasing habits can be influenced through new food experiences that have been enjoyed first time during a trip (Stone et al., Citation2018).

Furthermore, tourists want to engage in creating activities instead of just consuming, such as cooking classes, as well as to gain knowledge about how to grow, gather and use ingredients (Richards, Citation2003), which means that learning about food ingredients can occur in various settings and provide memorable encounters for consumers. The value of the educational aspect for tourists (Johnson et al., Citation2019) has also been touched upon in the previous section about tourism activities.

Seaweed and food tourism in Sweden

The potential of algae could be drawn upon more in a food tourism context in Sweden. In general, the long coastline as well as lakes and rivers have shaped the cuisine in Scandinavia (Nilsson, Citation2013) and many chefs in the Nordic countries are creating dishes with resources out of the waters, including seaweed (Mouritsen et al., Citation2019). An example is the New Nordic Cuisine, which has the ambition to be inspired by traditional foods and should be based on seasonality, regional and fresh ingredients, ethical food production, as well as simplicity and purity (Nordic Council of Ministers, Citation2008). This provides a background to integrate wild and unusual ingredients in a unique setting. Restaurants can then be seen as places where innovative gastronomy is created (Nilsson, Citation2013).

The Swedish coast could be promoted as a region using algae as a food ingredient. Research has pointed to the strong connection between certain locations and foods, and it is highlighted that the character of food products is naturally related to regions and climate conditions (Richards, Citation2003). Furthermore, food and locally produced food products are often attached to consuming the authentic and the true (Cleave, Citation2013). They attract tourists as well as non-tourists (Björk et al., Citation2014).

Although seaweed is a local resource and considered healthy, as well as highly nutritious, it is only slowly integrated in the Nordic cuisine (Chapman et al., Citation2015). However, a new seaweed gastronomy seems to be emerging, since Western chefs are showing increasing interest in using this marine resource (Mouritsen et al., Citation2019).

Materials and methods

In this explorative study, we take a consumer perspective in order to explore the seaweed experience and its value. Where is seaweed encountered and enjoyed? How is it used? What is experienced to be valuable about this resource? A qualitative, ethnographic approach was chosen to locate the algae in different contexts (cf. Czarniawska, Citation2007; Evans, Citation2018; Marcus, Citation1995).

As part of the research project “Marine food resources for new markets”, an explorative questionnaire was developed, in collaboration with the Folklife Archives in Lund, to elicit recipients’ thoughts and experiences about algae and seaweed, and to be used as a starting point for the following study. Individuals were invited to participate in an explorative online questionnaire about how algae and seaweed can create value. The questionnaire was available in English and Swedish, and was distributed via the website of the Folklife Archives at Lund University, and marketed through social media platforms such as Facebook and Linkedin, as well as via University Networks, for example the Food Faculty. As the questionnaire was openly published online, and might have been snowballed in the respondents’ networks, there was no limited target group. Thus, we cannot give a response rate. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. The questionnaire was published in May 2020 and includes 113 answers collected until October 2020. Eight open-ended questions analysed for this study are given in .

Table 1. Questions analysed for this study.

The majority of the respondents were Swedish (86), and more women (83) than men (21) answered the questionnaire. The biggest age group (41 respondents) were between 40 and 59 years old, the youngest respondents were two males, age 23, and the oldest respondent was female, age 77. Most respondents had a rather high monthly income, above 40,000 SEK (≈ 4000 EUR). See for a detailed overview.

Table 2. Respondents' demographics.

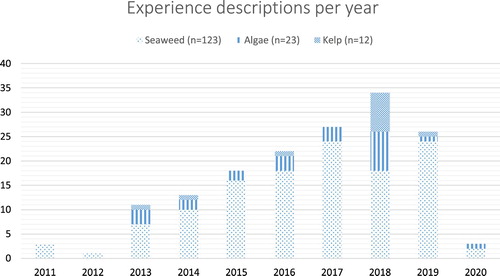

Online reviews from a consumer-to-consumer travel-planning portal form a second data set. This gives us the opportunity to indirectly explore “naturally occurring” seaweed experiences in a tourism context. The online review data was gathered in May and June 2020. Three manual searches using the travel-planning portal's own search function were conducted, to retrieve consumer reviews in English including the location “Sweden, Europe” and the keywords “algae”, or “seaweed”, or “kelp”. Tourists reviewed different settings such as hotels, restaurants, spas, eco tour providers, and national parks. Some reviews contained more than one of the keywords, which rendered duplicates that were eliminated in the final countFootnote1: In total 154 consumer reviews, two activity provider descriptions as well as two forum threads have been used as a base for the analyses. The gathered experiences on the travel-planning portal were published between 2011 and 2020 (see for an overview).Footnote2

Figure 1. Distribution of experience descriptions (n=158) on the online travel-planning platform per year.Footnote3

Through the increased use of technology (e.g. travel portals) consumers are able to share and even create (imagined) experiences for themselves and others (Buonincontri et al., Citation2017; Conti & Lexhagen, Citation2020; Helkkula et al., Citation2012; Mkono, Citation2011; Neuhofer et al., Citation2012; Vu et al., Citation2019). Imagined experiences can for example be created by reviewing others experiences about attractions or restaurants on travel information platforms (e.g. Tripadvisor) while planning a trip. The importance of this value producing activity is reflected in the growth of travel information platforms and social media use within tourism (Mkono, Citation2011; Phi & Dredge, Citation2019; Vu et al., Citation2019). By sharing a review about an experience on an online platform, the author actively contributes “something of value” (Phi & Dredge, Citation2019, p. 7). This can for example be a reflection and remembrance of an experience, and the review can be used by others in order to plan future trips.

Since this study explores the valuation of algae, consumer reviews are used as a mean to analyze not only the post-experience, but also “future or potential […] experiences” (Helkkula et al., Citation2012, p. 61). The focus is hereby on the reviews (and not a collective or a community). The travel-planning portal can be viewed as a public online space, in contrast to private discussion groups and communities. Therefore reviews might be considered as public documents (Ess & AoIR ethics working committee, Citation2002; Sugiura et al., Citation2016). Reviews include recommendations and advice from consumers-to-consumers and can be assumed to be intended for a public audience. They are available online on a commercial platform and visibility does neither include signing up, nor require ethnographic interaction. The platform offers interaction possibilities for members only, for example comment and messaging functions.

This study method has several limitations and especially the loss of context stands out. No ethnographic interaction took place and the reviews stand for themselves. However, it gives the opportunity to observe indirectly if and how algae are part of a tourist`s remembered experience. Reviews about restaurants for example can be seen as “provid[ing] rich information about dining experiences of tourists, including the cuisines and dishes they prefer as well as their background” (Vu et al., Citation2019, p. 150).

Both data sets were organized in separate tables. In order to get familiar with the data the answers from the questionnaire and the consumer reviews on the travel-information-platform were read in detail. This provided an initial overview of how people relate to the marine resource algae. In a second step, all questionnaire responses and reviews were categorized based on in what setting or context people have experienced algae. This rendered three broader categories: food, nature, and other (e.g. wellness). In the nature category, examples that were clearly positive or negative were labelled as such. In a third step, for all data, except nature experiences labelled as negative, utilizations and encounters were analysed more specifically with regard to the perceived value of this marine resource. All quotes from the questionnaire have been translated by the authors.

Results

Explorative questionnaire

The respondents expressed different connotations and words, and the findings from the questionnaire convey that seaweed and algae are related to different experience categories, such as food, nature, or wellness. Overall, algae and seaweed as food were the most reported types of experiences. Encounters in nature formed a second large category, and diverse other utilizations could also be identified.

Respondents’ experiences included diverse usages of algae, such as fertilizer, building material, biofuel, medical products, textiles, animal feed, in beauty products, as well as in spa treatments as this example shows: “The hot-bath-house in Torekov after a week of hard sailing. Sooo wonderful to crawl into a bathtub with scalded seaweed and scrub the body with it and become soft and smooth!” (71, femaleFootnote4). Everyday life utilizations mixed with special occasions, such as a wellness treatment at the end of a sailing trip.

Many respondents experienced the marine resource algae as part of the natural environment and examples for clearly negative or positive associations were identified. People shared memories related to beaches, summer, travelling and vacation. Positive connotations, about a healthy environment, as well as appreciating the looks and the smell, can be seen in this response: “[…] the first thoughts that come to mind are the sea, swaying seaweed forests, fragrant hills on the beach, older seaweed banks” (43, not stated). Moreover, people even engage with algae in a more active way, which includes for example diving, beach walks, and playing with it: “Fun! Dry bladder wrack snaps when one presses the blisters together. With the light green one we played soap and washed ourselves with it” (77, female), as a respondent remembered.

Negative associations related to things that are out of place, such as something growing in aquariums and on house facades, as well as environmental pollution and prohibitions to swim. The following quote, by yet another respondent, shows the complexity, examples for negative and more positive associations that can be found in the same answer:

"[…] Swimming in the sea and being freaked out because something touches my legs. Creepy and gross. Looks peaceful under water (as long as it doesn't touch me!!) but looks weird and slightly disgusting outside of the water. Also smells very bad when it's outside of the water. If it was “hidden” in any products […], I would eat it though because it's probably super healthy." (27, female)

Algae and seaweed are both connected to food, especially to Asian food as this respondent stresses:

“[…] Sushi was not hard to fall for with its beautiful little works of art. Now there is sushi in ICA as a lunch box. It has gone from luxury and exclusivity to “take-away” […] I added seaweed to my diet to reduce carbohydrate intake and thus changed spaghetti to “sea spaghetti”, motivated by a healthier lifestyle / healthier food intake. […] I'm totally into wakame, seaweed salad that I tried for the first time at an Asian restaurant”. (43, not stated)

Over half of the respondents associate seaweed with being healthy. Moreover, examples can be found where respondents differentiate and highlight that this depends on diverse aspects such as the type of algae, and the environment they are harvested in. Apart from being healthy and nutritious, algae and seaweed were also related to environmental sustainability and responses included words such as “green”, “climate-smart”, and “renewable”.

Besides eating seaweed in for example restaurants, people also engage in other consumption activities in coastal areas, as another respondent expresses: “[…] I have in recent years started to try harvesting freshly grown bladder wrack to have in salad for fish dishes” (54, male). Harvesting seaweed, participating in cooking classes, seaweed safaris and kayak trips, as well as travelling to Asian countries are other examples for different settings, where this marine resource is encountered and consumed as food. A respondent explains: “I have even, as a co-organizer of the [annual local village and harbour celebration], thought about a Seaweed safari with cooking as an ending, to increase knowledge about it” (71, female). A need to increase the knowledge on how to consume algae, which includes acquisition as well as preparing and cooking them, occurred throughout the questionnaire in various contexts. The interest shown in various coastal activities related to seaweed, and the wish to learn more about this resource, provides potential business opportunities for tourism actors.

Online travel-planning portal

Reviews in English that included the keywords “algae”, “seaweed”, “kelp”, as well as the location “Sweden, Europe” have been retrieved from an online consumer-to-consumer travel-planning portal. In an initial step, the total number of experience descriptions (n=158) were grouped into three main experience categories that also occurred within the questionnaire responses. Algae as food (70%), algae as part of nature (27%), and algae in connection to other experiences, for example wellness (3%). See Footnote5 for a detailed overview.

Table 3. Algae experience categories.Footnote6

Similar to the data in the questionnaire, the online reviews showed a few other usages of algae (n=4) than as food or occurring in nature. For example, in connection with an exhibition, one review highlights the exclusivity of the sea product, relating various ways of using the marine resource to environmental sustainability. The other examples are reviews where the authors recommend the seaweed sauna, the seaweed bath, and the seaweed massage in the wellness section of hotels.

In the experiences referring to seaweed as part of nature, examples for “negative” or “positive” experiences could be identified. Algae as part of a natural setting seem to be experienced in a sensory way, for example through smell or touch.

Examples for negative encounters (n=43) are the expression of a feeling of disturbance or disgust while visiting a beach, such as disappointment about the smell of rotting algae, or concerns about health aspects regarding children and pets. These negatively connotated experiences also include impressions about amounts of seaweed on beaches as well as in the sea, that are associated with “not clean”, “stinking” or “dirty”, as described by tourists. Smell, touch and visual experiences are reported in these descriptions.

Fewer people (n=10) documented a positively recalled encounter with the marine resource algae, where it contributes to the valuation of the nature experience due to a beautiful scenery. Enjoying the underwater forests, the lovely smell, the different colours of the seaweed in the water, or praising the shelter it offers to animals in a national park are examples of how tourists appreciate algae.

The majority of experience descriptions refer to edibility (n=110). Algae as a gastronomic product appear to often contribute to memorable experiences.

In less detailed reviews, the expectation to find edible algae included in a dish seems to be there. The tourists describe for example consumption experiences in sushi restaurants or restaurants that serve non-western cuisine. Seaweed is often simply listed as part of the meal but without any specially conveyed opinion. Shorter comments refer for example to the “korean” or “neo-Asian” cooking style, the quality and freshness of a product (e.g. seaweed salad), and authenticity of the dining experiences. However, some recalled experiences provide more details, elaborating and commenting on the creative use of nutritious ingredients or ideas about environmental sustainability.

In various reviews the emphasis on the localness of the used products, or the Nordic, as well as Swedish origin of the ingredients is notable. Some people also stress the seasonality of the consumed food. This could connect to broader themes about environmental sustainability. One description mentions specifically the importance of a decreased ecological footprint.

Furthermore, a small amount of reviews also connects algae to healthy and nutritious ingredients, for example people write about the “healthy”, “vital” and “nutritious” food they consumed.

Our data shows that new knowledge about consuming foods and ingredients is created in different dimensions. In their online reviews, people recall and appreciate the satisfaction about the knowledgeable restaurant staff explaining the food, as well as their own learning experience about new possible ingredients. The expression of an element of surprise about seaweed as an ingredient can also be highlighted. For example, some consumers state that they wouldn’t have thought about using algae in their cooking, or that they tried that ingredient for the first time ever. Initial hesitation towards unusual combinations had to be overcome by some tourists, and others mention that it took them some “courage”. Most descriptions commented on the tastiness and the excellence of the meal consumed. The food is also described as “creative” and as “art” in some reviews. Moreover, the knowledge of the chefs is praised and referred to as for example “craftsmanship”. The acknowledgement of the chefs' or the restaurants' creativity becomes visible also in comments such as the “interesting”, “new”, or “unusual” combinations of ingredients and tastes.

A number of travellers provide information about their own lifestyle in their reviews. For example, people who state to live mainly on a plant-based diet, utter surprise when they are offered the possibility to order a multi-course vegan meal instead of a less interesting side dish or a salad. Another example is people who express expert knowledge on food. Review writers refer to previous experiences for comparison such as the cuisine of a certain region, or former dining experiences in Michelin star restaurants.

Discussion

To better understand the potential of the marine resource algae, we have investigated seaweed experiences in different settings. Through our explorative study, we identified various ways of associating and conceptualizing algae. It can be seen that this marine resource is experienced in diverse spatial and geographical dimensions, such as at home, or while being a tourist, as part of everyday life or as a special treat, within nature, and as food. Our findings indicate that multidimensional values are created in the seaweed experience between different actors and settings.

In a tourism context, algae seem to be mainly consumed as food, as parts of nature, and as part of wellness treatments. The application of this marine resource in beauty products, saunas and massages seems to be a small niche for now and could be utilized more in coastal areas of the Nordic countries. For example, locally and sustainably harvested raw materials could be promoted in connection to physical wellbeing. Opportunities for local communities and how to expand this tourism setting could be investigated further.

The potential of seaweed for marketing nature destinations, such as coastal or marine national parks, diving spots, or fishing areas, has been explored. Tourists enjoy the looks of underwater forests as well as appreciate the biodiversity and habitat for animals. This is relevant, especially for areas such as leisure fishing and ecotourism, where activities in nature are in focus. Companies have already started to offer services, such as adventure trips that include snorkeling for the marine resource. However, it has also been shown that if seaweed is considered to be “out of place” it can contribute to an unpleasant nature experience, accompanied by feelings of disturbance, thoughts about pollution, as well as concerns regarding health aspects. Future possibilities for entrepreneurial tourism operators utilizing algae and the promotion of different nature settings could be studied further.

Food experiences seem to be valued the most so far. Findings suggest that vegans or vegetarians, as well as culinary interested tourists, for example high-end restaurant consumers, are part of an early adopter group and could be targeted more explicitly. Consumers eating in “Asian” restaurants seem to find it familiar to have algae in their meal, while others that expect a “Western” or “Scandinavian” cuisine show surprise about the “unusual” ingredient. Algae seem to have the potential to be “special” as well as “normal”, depending on the setting and context, and expectations brought by these. Furthermore, associations to seaweed being healthy and nutritious, as well as seasonal and local could also be identified. Destination marketers as well as restaurant owners could emphasize these sustainable values. This is already partially occurring, for example in the New Nordic Cuisine. Trendy restaurants have lately certainly become an arena for creativity. The culinary experience includes “unusual”, “wild”, and regional ingredients from the local forests and the waters. Those kinds of restaurants offer a safe environment and an expectation of exploring something new is already embedded in the price.

Another aspect that is valued in relation to seaweed as food is the learning experience about new ingredients. The data shows how different learning processes take place and how the knowledge sharing and creation are connected and valued in the “new” culinary experience. Tourists can be more courageous and curious than in their everyday habits and show a positive surprise by being introduced to new and creative ingredients. Activity providers that focus on algae and offer cooking workshops seem to still be rare and thus an unused potential.

A wide range of ideas and images exist surrounding seaweed and this range of notions and images enables space for different settings and actors to play upon. As research has already pointed out, diverse challenges arise while trying to diversify fisheries into the tourism sector. However, in connection to the largely unused resource algae we can see a great potential from a consumer perspective. Especially in already established cooperations between restaurants and traditional fisheries, algae could enlarge the product range. Today, various restaurants collaborate with local producers of seaweed. So far, the seaweed introduction in Sweden seems to go through exclusive restaurant menus and guided seaweed safaris.

Overall, this paper has explored ways of experiencing seaweed from a consumer perspective. To understand the potential of algae better, we have posed the following questions: Where is seaweed encountered and enjoyed? How is it used? What is experienced to be valuable about this resource? Our findings show that this marine resource can be experienced in diverse dimensions, such as while travelling or being at home, as part of everyday life, or a special treat. In a tourism context in Sweden, our data suggest that algae are encountered and enjoyed mainly as food, but also as a part of a natural environment, and in wellness. For now, the usage of this marine resource as a part in wellness treatments, such as massages or saunas, seems to be rare. Nevertheless, consumers enjoy those special offers and even recognize algae as an ingredient in their beauty products at home. Other ways of using algae are sustainable nature experiences connected to seaweed. Guided seaweed-tour-offers by ecotourism operators, such as snorkelling, kayaking, and harvesting trips, appear to be a current niche as well. Apart from simply being a part of nature, algae are hereby actively utilized to create a memorable (nature) experience for the tourist. The main usage of seaweed seems to be as food. In a food context, associations to health and nutrition, as well as aspects of environmental sustainability, such as seasonal and local, occur and are valued. A creative use of, for the consumer, unusual or previously unknown ingredients in restaurants, and an element of surprise, contribute to a valuable culinary experience. Furthermore, different learning processes that are closely connected to consuming a “new” food ingredient, such as algae, are valued in the experiences. These learning processes can be found across diverse dimensions and the three experience categories wellness, nature, and food.

Limitations and recommendations for future research

Due to the study design, a limitation is that for example the voices of restaurant owners, chefs, and entrepreneurs are not included. Future ethnographic research could provide valuable insights including these actors. Since many tourists exchange online, we would like to highlight the rich narratives of these written experiences as data material. In order to explore the potential of the marine resource seaweed for new products and services in the Nordic countries, tourism – an environment that fosters the curiosity towards adventurous experiences – can be a new and suitable study field. The consumer being a tourist, investing in and expecting new experiences, seems to be a good platform to develop and learn about products and services that can later on be implemented in an everyday habit.

The loss of context due to the study method might be approached by applying a greater variety of methods in future research, such as observations and surveys on site, focus group discussions, diaries, pictures, and in-depth narrative interviews. Interacting with the consumers of a seaweed experience would provide an opportunity to gain more detailed and reflected thoughts and notions.

The seaweed experience could be explored further within the three identified categories: In wellness tourism and the use of natural treatments for mental and physical wellbeing; In nature tourism experiences, for example in a national park, but also in tour offers provided by ecotourism operators and entrepreneurs; In memorable food tourism experiences and the perspectives of restaurant owners, chefs, and producers. To incorporate a production perspective could also open up to further study the business possibilities for small-scale enterprises, such as fisheries. Already established cooperations between seaweed producers, fisheries, and restaurants could form a starting point. Since we have explored a Swedish context, a cross-cultural comparison could also offer valuable insights into the potential and value of the marine resource algae on a broader scale. To connect to everyday life and potential societal transformations, studies investigating the impact of learning about algae during a trip (or an otherwise memorable experience) on future consumption habits, purchasing decisions, as well as attitudes and notions towards the natural environment, could be pursued.

We have shown examples of how and in what contexts algae are valued by tourists. Tourism operators and activity providers can build on these findings to develop new business models surrounding this marine resource. This could lead to new income possibilities for local communities as well as environmental awareness. If fisheries could be diversified into creating seaweed experiences remains an open question. However, from a consumer perspective we can see an interest in learning more about this marine resource and utilizing it. Destination marketers and restaurant owners could use the potential of algae to promote their objectives. This includes aspects of localness, creativity, and knowledge creation. Touristic seaweed experiences could potentially also lead to inspiration and change in everyday habits and thereby contribute to broader societal transformations such as incorporating sustainable new foods.

It requires courage to dwell into this new and unusual resource, both as a consumer and as a producer. The act of value creation between different actors can be even more important when the object is complex. This study has contributed new knowledge by expanding the understanding of the construction of algae and seaweed as a marine resource. In conjunction with the marketing of a specific coastal destination – and a natural resource with the potential of being innovative and sustainable – this knowledge expansion can contribute to the creation of a new market for Swedish seaweed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Most people used only one of the keywords, although four reviews contain the word “algae” plus either “seaweed” or “kelp”. These four reviews have been included in and under more than one keyword.

2 See endnote 1.

3 See endnote 6.

4 Respondent's age and gender in brackets.

5 See endnote 1.

6 Two reviews contain the word “algae” plus “seaweed” and two reviews contain the word “algae” plus “kelp”. These four reviews have been included in Table 3, and Figure1 under more than one keyword, but are not in the total count.

7 This includes the two activity provider descriptions and the two forum threads.

References

- Birch, D., Skallerud, K., & Paul, N. A. (2019). Who are the future seaweed consumers in a Western society? Insights from Australia. British Food Journal, 121(2), 603–615. https://doi.org/10.1108/bfj-03-2018-0189

- Björk, P., Claire Seaman, M. B. Q. D., & Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. (2014). Culinary-gastronomic tourism – a search for local food experiences. Nutrition & Food Science, 44(4), 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1108/nfs-12-2013-0142

- Bouga, M., & Combet, E. (2015). Emergence of seaweed and seaweed-containing foods in the UK: Focus on labeling, iodine content, toxicity and nutrition. Foods (basel, Switzerland), 4(2), 240–253. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods4020240

- Buonincontri, P., Morvillo, A., Okumus, F., & van Niekerk, M. (2017). Managing the experience co-creation process in tourism destinations: Empirical findings from Naples. Tourism Management, 62, 264–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.04.014

- Catxalot AB. (2020). Catxalot. https://catxalot.se/en/kontakt-43454636

- Chapman, A. S., Stévant, P., & Larssen, W. E. (2015). Food or fad? Challenges and opportunities for including seaweeds in a Nordic diet. Botanica Marina, 58(6), 6. https://doi.org/10.1515/bot-2015-0044

- Chen, C.-L. (2010). Diversifying fisheries into tourism in Taiwan: Experiences and prospects. Ocean & Coastal Management, 53(8), 487–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2010.06.003

- Cleave, P. E. (2013). The evolving relationship between food and tourism: A case study of Devon in the twentieth century. In M. C. Hall & S. Gössling (Eds.), Sustainable culinary systems (pp. 165–168). Routledge.

- Conti, E., & Lexhagen, M. (2020). Instagramming nature-based tourism experiences: A netnographic study of online photography and value creation. Tourism Management Perspectives, 34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100650

- Czarniawska, B. (2007). Shadowing and other techniques for doing fieldwork in modern societies (1. [uppl.] ed.). Liber.

- Douglas, M. (1975). Implicit meanings: Essays in anthropology. Routledge.

- Ess, C., & AoIR Ethics Working Committee (2002). Ethical Decision-Making and Internet Research: Recommendations from the AoIR Ethicsworking Committee. www.aoir.org/reports/ethics.pdf

- Evans, D. M. (2018). Rethinking material cultures of sustainability: Commodity consumption, cultural biographies and following the thing. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 43(1), 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12206

- Everett, S. (2016). Food and drink tourism: Principles and practice. SAGE Publications.

- Fairweather, J. R., Maslin, C., & Simmons, D. G. (2005). Environmental values and response to Ecolabels among international visitors to New Zealand. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 13(1), 82–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501220508668474

- FAO (2018). The global status of seaweed production, trade and utilization. http://www.fao.org/3/CA1121EN/ca1121en.pdf

- Fleurence, J., Morançais, M., Dumay, J., Decottignies, P., Turpin, V., Munier, M., Nuria, G.B., & Jaouen, P. (2012). What are the prospects for using seaweed in human nutrition and for marine animals raised through aquaculture? Trends in Food Science & Technology, 27(1), 57–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2012.03.004

- Fredriksson, C., & Säwe, F. (2020). Att ta en tugga av havet. Om blå åkrar, grön ekonomi och den smarta tångens svåra resa. Kulturella Perspektiv 4:2020. [in press].

- Gundersen, H., Bryan, T., Chen, W., & Moy, F. E. (2017). Ecosystem services: In the coastal zone of the Nordic countries. Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Hall, M. (2001). Trends in ocean and coastal tourism. Ocean & Coastal Management, 44(2001), 601–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0964-5691(01)00071-0

- Hall, M., & Mitchell, R. (2005). Chapter 6 - gastronomic tourism: Comparing food and wine tourism experiences. In M. Novelli (Ed.), Niche tourism (pp. 73–88). Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Hall, M., & Sharples, L. (2004). The consumption of experiences or the experience of consumption? An introduction to the tourism of taste. In M. C. Hall, L. Sharples, R. Mitchell, N. Macionis, & B. Cambourne (Eds.), Food tourism around the world (pp. 13–36). Routledge.

- Hasler, B., Ahtiainen, H., Hasselström, L., Heiskanen, A. S., Soutukorva, Å, & Martinsen, L. (2016). Marine ecosystem services: Marine ecosystem services in Nordic marine waters and the Baltic sea-possibilities for valuation. Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Hasselstrom, L., Visch, W., Grondahl, F., Nylund, G. M., & Pavia, H. (2018). The impact of seaweed cultivation on ecosystem services - a case study from the west coast of Sweden. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 133, 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.05.005

- Heldmark, T. (2018). Alger – den fullvärdiga kosten som renar haven. https://www.kth.se/aktuellt/nyheter/alger-den-fullvardiga-kosten-som-renar-haven-1.899073

- Helkkula, A., Kelleher, C., & Pihlström, M. (2012). Characterizing value as an experience. Journal of Service Research, 15(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511426897

- Holdt, S. L., & Kraan, S. (2011). Bioactive compounds in seaweed: Functional food applications and legislation. Journal of Applied Phycology, 23(3), 543–597. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-010-9632-5

- Honey, M., & Krantz, D. (2007). Global trends in coastal tourism.

- Hultman, J., Säwe, F., Salmi, P., Manniche, J., Bæk Holland, E., & Høst, J. (2018). Nordic fisheries at a crossroad: Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Johnson, A. F., Gonzales, C., Townsel, A., & Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M. (2019). Marine ecotourism in the Gulf of California and the Baja California Peninsula: Research trends and information gaps. Scientia Marina, 83(2), 177–185. https://doi.org/10.3989/scimar.04880.14A

- Kaufmann, J.-C. (2010). The meaning of cooking (English ed. Ed.). Polity Press.

- Kraan, S. (2020). Seaweed resources, collection, and cultivation with respect to sustainability. In M. D. Torres, S. Kraan, & H. Dominguez (Eds.), Sustainable seaweed technologies (pp. 89–102). Elsevier.

- Long, L. M.. (2004). Culinary tourism: A folkloristic perspective on eating and otherness. In L. M. Long (Ed.), Culinary tourism (Vol. 55, pp. 20–50). Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky.

- Marcus, G. E. (1995). Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24(1), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.000523

- Miller, M. L. (1993). The rise of coastal and marine tourism. Ocean & Coastal Management, 20(3), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/0964-5691(93)90066-8

- Mkono, M. (2011). The othering of food in touristic entertainment: A Netnography. Tourist Studies, 11(3), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797611431502

- Mouritsen, O. G., Rhatigan, P., & Pérez-Lloréns, J. L. (2019). The rise of seaweed gastronomy: Phycogastronomy. Botanica Marina, 62(3), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1515/bot-2018-0041

- Näslund, L. (2020, Måndag 24 Augusti). Odlad tång kan bli västkustens nya guld, Nyheter. Dagens Nyheter, pp. 10-11.

- Neuhofer, B., Buhalis, D., & Ladkin, A. (2012). Conceptualising technology enhanced destination experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(1-2), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.08.001

- Nilsson, J.-H. (2013). Nordic eco-gastronomy. The slow food concept in relation to Nordic gastronomy. In M. C. Hall & S. Gössling (Eds.), Sustainable culinary systems (pp. 189–204). Routledge.

- Nordic Council of Ministers. (2008). New Nordic Cuisine. http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:701317/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Orams, M. B., & Lück, M. (2014). Coastal and marine tourism. In A. A. Lew, M. C. Hall, & A. M. Williams (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell companion to tourism (pp. 479–489). Wiley.

- Palmieri, N., & Forleo, M. B. (2020). The potential of edible seaweed within the western diet. A segmentation of Italian consumers. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgfs.2020.100202

- Papageorgiou, M. (2016). Coastal and marine tourism: A challenging factor in marine spatial planning. Ocean & Coastal Management, 129, 44–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.05.006

- Phi, G. T., & Dredge, D. (2019). Collaborative tourism-making: An interdisciplinary review of co-creation and a future research agenda. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(3), 284–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2019.1640491

- Rebours, C., Marinho-Soriano, E., Zertuche-Gonzalez, J. A., Hayashi, L., Vasquez, J. A., Kradolfer, P., Soriano, G., Ugarte, R., Abreu, M. H., Bay-Larsen, I., Hovelsrud, G., Rødven, R., & Robledo, D. (2014). Seaweeds: An opportunity for wealth and sustainable livelihood for coastal communities. Journal of Applied Phycology, 26(5), 1939–1951. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-014-0304-8

- Richards, G. (2003). Gastronomy: An essential ingredient in tourism production and consumption?. In A.-M. Hjalager & G. Richards (Eds.), Tourism and gastronomy (pp. 3–20). Routledge.

- Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (2020). Coastal tourism in South Africa: A geographical perspective. In J. M. Rogerson & G. Visser (Eds.), New directions in South African tourism Geographies (pp. 227–247). Springer.

- Romare, P. (2018). Äta nytt – kanske rätt, men inte lätt! https://www.lu.se/article/ata-nytt-kanske-ratt-men-inte-latt-0

- Stone, M. J., Migacz, S., & Wolf, E. (2018). Beyond the journey: The lasting impact of culinary tourism activities. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(2), 147–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1427705

- Sugiura, L., Wiles, R., & Pope, C. (2016). Ethical challenges in online research: Public/private perceptions. Research Ethics, 13(3-4), 184–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747016116650720

- SwAM, S. A. f. M. a. W. M. (2012). Marine tourism and recreation in Sweden. A study for the economic and social analysis of the initial assessment of the marine strategy framework directive. https://www.havochvatten.se/download/18.b62dc9d13823fbe78c800016013/1348912842332/rapport-2012-02-marine-tourism-and-recreation-in-sweden.pdf

- Vu, H. Q., Li, G., Law, R., & Zhang, Y. (2019). Exploring tourist dining preferences based on restaurant reviews. Journal of Travel Research, 58(1), 149–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517744672

- Wendin, K., & Undeland, I. (2020). Seaweed as food – attitudes and preferences among Swedish consumers. A pilot study. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgfs.2020.100265

- WWF Baltic Ecoregion Programme. (2015). Principles for a sustainable blue economy. http://d2ouvy59p0dg6k.cloudfront.net/downloads/15_1471_blue_economy_6_pages_final.pdf