ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to explore the sustainability values that tourism companies communicate to stakeholders. The following two research questions are addressed: What sustainability value (economic, social, or environmental) do tourism companies focus on and communicate in their sustainability information? Do different types of tourism companies provide different sustainability communications to stakeholders to gain legitimacy? A case study was conducted of 30 Swedish-based tourism companies. Written documents that were available online concerning sustainability information from these companies were analysed using the GRI model. The results show that tourism companies work to create value with the help of sustainability. The results also indicate that the context and prerequisites for each type of tourism company govern what they work with in order to meet the demands of stakeholders. The study's theoretical contribution is that sustainability communication to stakeholders can be of value to tourism companies. Its practical contribution is that, in addition to pursuing sustainability, tourism companies should communicate their sustainability work to their stakeholders in order to create value.

Introduction

Not only have sustainability issues become increasingly important for many sectors in society, including tourism companies, but so have how they act and communicate their sustainability efforts. The 1987 Brundtland Commission Report, also known as Our Common Future, addresses how we are all responsible for sustainable development, which the commission defines as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (The Brundtland Commission Report, Citation1987, p. 4). Economic growth, environmental protection, and social equality are the three areas of sustainable development that are emphasized. These three areas were further developed through the development of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) when the United Nations Member States adopted Agenda 2030 in 2015 (UN, Citation2021). The Global Reporting Initiatives (GRI) from 1997, which set the global standards for sustainability reporting regarding economic, social, and environmental sustainability, specifically targeted large companies within the European Union (EU). Since 2017, it has been mandatory for large companies within the EU to publish sustainability reports annually. With these documents in place, there are now clear guidelines for individuals and businesses on how to act in a sustainable way to protect our common future. The handling and prioritizing of sustainability issues vary between different industries, and this article focuses on the tourism industry.

Research into the tourism industry regarding sustainability issues has changed over the years. In the 1990s, environmental issues and economic factors were often given more attention than social issues, such as engagement in the community (Deegan & Rankin, Citation1997). Hotels were initially focusing mainly on environmental issues, such as energy and water use, and less on social issues (Font et al., Citation2012). Even today, the social dimension of sustainability receives insufficient attention. Ioannides et al. (Citation2021) argue that the social equality dimension of tourism sustainability should receive more attention and be given the same status as environmental and economic growth concerns. Interest in the concepts of sustainability has increased in society and among stakeholders (Freeman et al., Citation2010; Harrison et al., Citation2015; Schaltegger et al., Citation2017). From the tourism companies’ perspective, this is a good opportunity to gain legitimacy among their stakeholders. It is crucial to their success that companies gain and sustain legitimacy from stakeholders within society (Dowling & Pfeffer, Citation1975; Richards et al., Citation2017). Stakeholders in the tourism industry desire and expect information about tourism companies’ sustainability work (Sörensson et al., Citation2021).

Sustainability is highlighted as one of the tourism industry's main challenges, in terms of climate change, health and wellbeing, and technology (Lundberg & Furunes, Citation2021). Climate change is an issue that affects most industries, not just the tourism industry, and companies must therefore relate to this issue and act in a more sustainable way. Nordic researchers, for example, have addressed tourism's contribution to climate change and solutions for the future (Gössling, Citation2013; Gössling et al., Citation2013; Gössling & Hall, Citation2008; Hall & Saarinen, Citation2021). Postma et al. (Citation2017) argue that tourism companies need to be more sustainable both now and in the future by integrating social, environmental, and economic values into business strategies and operations. For companies who want to show that they are taking a greater responsibility for sustainability, sustainability-oriented business models (Breuer et al., Citation2018) and business models for sustainability innovation (Lüdeke-Freund, Citation2020) can be helpful in leading their businesses and creating value that can contribute to a company's success (Freudenreich et al., Citation2020).

Research about value is extensive, and value has been addressed from different perspectives, such as positivist, interpretive, and social constructionist (Zeithaml et al., Citation2020), as well as in different contexts. Because of these differing perspectives, there exists considerable variation in both conceptualization and measurement. Anderson and Narus (Citation1998, p. 54) define value as “the worth in monetary terms of the technical, economic, service, and social benefits a customer company receives in exchange for the price it pays for a market offering”. Value is also subjective and therefore varies between customers and cultures and in different historical periods. The value may also vary depending on the time: before purchase, during purchase, at time of use or after use (Sanchez et al., Citation2006). In this paper, Anderson and Narus’s (Citation1998) definition of value is used as a starting point, where value is about how sustainability information within the tourism industry can be used by different stakeholders.

Companies today provide sustainability information through different channels, including annual or sustainability reports and websites, and they see this communication as a value. Romero et al. (Citation2019) argue that companies publishing sustainability reports or integrated reports provide higher quality information than companies that only include sustainability information within their annual reports. Unerman (Citation2000) highlights that providing sustainability information only in annual reports can give an incomplete picture, since companies are often involved in a greater number of sustainability activities than is visible in annual reports. De Grosbois (Citation2012) agrees and highlights the need for third-party verification. Bani-Khalid (Citation2020) found that organizations have realized the importance of using their websites to show themselves as accountable parties to their stakeholders. The information they provide can vary depending on which stakeholder it is aimed at, as different stakeholders ask for different types of sustainability information (Cormier et al., Citation2004; Rowbottom & Lymer, Citation2009). Currently, research shows a wider view that includes all types of stakeholders, not just shareholders (Salvioni & Gennari, Citation2017). Previous research has shown that different types of companies focus on different areas – for example, hotels might focus on social sustainability, and restaurants might focus on environmental sustainability (Sörensson & Jansson, Citation2016) – and that companies seem to prioritize and focus on one of the three sustainability dimensions at a time (Rowbottom & Lymer, Citation2009; Sörensson, Citation2014). Today, many companies see sustainability as a value that benefits their stakeholders, and Aquilani et al. (Citation2018) argue that sustainability should be integrated into the value co-creation wherein companies and stakeholders interact (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2004).

The aim of this paper is to explore the sustainability values that tourism companies communicate to stakeholders.

The following two research questions are addressed:

RQ1: What sustainability values (economic, social, or environmental) do tourism companies focus on and communicate in their sustainability information?

RQ2: Do different types of tourism companies provide different sustainability communications to stakeholders to gain legitimacy?

The paper is structured as follows. Firstly, the literature is reviewed under three subheadings: Sustainability communication, Communicating sustainability to increase value and gain legitimacy, and Value co-creation of sustainability with stakeholders. Secondly, the methodology is explained and discussed. Thirdly, the findings are presented and discussed under the subheadings of The economic, social, and environmental sustainability communication as value, and Sustainability communication – differences among the tourism companies, before this section ends with a suggestion under the subheading The fourth layer of sustainability – communicating sustainability and legitimacy. Finally, the study's conclusions are drawn, and the research questions are answered.

Literature review

This literature review addresses three areas relevant for the study. Firstly, sustainability communication is discussed, as well as the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainability research. Secondly, there is a discussion of how tourism companies communicate sustainability to increase value and gain legitimacy. Thirdly, value co-creation of sustainability towards stakeholders is discussed.

Sustainability communication

Today, sustainability is a frequently discussed topic in society, as is working with sustainability in organizations. The concept of sustainable development has been discussed since the 1980s, with the Brundtland Commission Report, published in 1987, as a central document. Today, sustainability has taken on a long-term perspective, as the commission's report intended, and tourism companies are expected to address all three dimensions of sustainability: economic, social, and environmental (Aras & Crowther, Citation2008; Carroll, Citation1999; Dahlsrud, Citation2008; Salvioni & Gennari, Citation2017; Van Marrewijk & Werre, Citation2003).

Over the years, there have been different approaches and responses to sustainability. Since the 1980s, the role of sustainable development has mainly been based on the issue of “responsibility” to society, where responsibility is defined as a need to eliminate the negative effects of business (Baumgartner, Citation2014). Sustainable development can be further divided into three perspectives: an innovation-based perspective built on the concept of eco-efficiency; a normative perspective whose core focuses are justness, equity, and ethics in order for companies to protect future generations; and a rational perspective that focuses on the use of resources (Baumgartner, Citation2014; Müller-Christ & Hülsmann, Citation2003). The difference between these perspectives relates to the motivation behind sustainability. Other approaches, though effective, may only be successful for a limited time. One example is companies – often hotels – managing to reduce energy use or waste. They often make great savings initially, but it typically becomes harder to find these improvements in subsequent years (Baumgartner, Citation2014). When considered in a broader sense, sustainable development can be a key benefit for value creation for both the company itself and its stakeholders in society (Baumgartner, Citation2014; McWilliams & Siegel, Citation2011). Thus, tourism companies that take sustainability issues seriously and cooperate with other actors (e.g. customers and business partners) can gain value on a long-term basis and contribute to a more sustainable world.

CSR is a concept that has been in use for many years; it had its starting point in the social dimension and was often defined as sacrificing profits in the social interest (Elhauge, Citation2005). The definition was later widened to include economic and environmental issues. Today, a generally accepted definition originated by the European Commission (Citation2002) describes CSR as a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations, and in their interaction with their stakeholders, on a voluntary basis. One of the research orientations within CSR research specifically emphasizes the integrating of stakeholders (Buysse & Verbeke, Citation2003; O’Riordan & Fairbrass, Citation2008). Being socially responsible means not only fulfilling legal expectations but also going beyond compliance. Based on the above-mentioned the European Commission definition, CSR today comprises the three sustainability dimensions (economic, social, and environmental). For many years, CSR was the most commonly used term, but about a decade ago companies started to use the term sustainability instead. Sustainability has since become an integrated concept that includes CSR (Gatti & Seele, Citation2014; Karen, Citation2008). In this paper, the concept of CSR is used in the theoretical framework, but for the analysis and discussion, the broader concept of sustainability including the concept of CSR is used.

Companies have a responsibility to society, and Carroll (Citation1979, p. 499) states that businesses that practice social responsibility attend to “economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectations that society has of organizations at a given point in time”. Carroll (Citation1999) later replaced the discretionary dimension with a philanthropic dimension. However, companies’ social reporting might not automatically lead to improved CSR performance, since social reporting can be used as a method to avoid the additional introduction of regulation (Hess, Citation2008). Since 1997, the GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards (GRI Standards) have been widely used for sustainability reporting around the world (www.globalreporting.org). Initially, the GRI indicators focused on environmental performance, but they were later extended to include social performance and economic performance (Nikolaeva & Bicho, Citation2011).

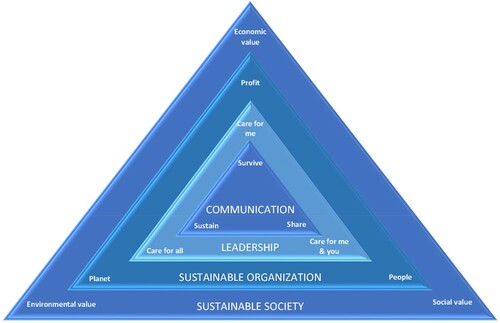

Cavagnaro and Curiel (Citation2012) argue for three levels of sustainability (e.g. society, organization, and leadership). The model is visualized as a triangle that has three layers. The outer triangle illustrates the first layer, which is sustainable development from the perspective of society. It is the economic value, social value, and environmental value for society. The second layer illustrates the organization's perspective and addresses Elkington (Citation1997) ideas of profit, people, and planet. A sustainable society cannot be achieved without sustainable organizations. The third, inner layer addresses the issue of leadership and the inner self. The first dimension is therefore “care for me”, which relates to economic value and profit in the other two layers. The dimension “care for me and you” relates to social value and people in the other two layers. The dimension “care for all” relates to environmental value and the planet in the other layers. The model as a whole argues that sustainability starts and ends with human beings (Cavagnaro & Curiel, Citation2012), and for the study presented in this paper, it contributes to how value can be visualized on different levels and from different perspectives.

Among tourism companies, hotels were early to focus on sustainability issues. However, results from previous studies investigating hotels show varying results. Henderson (Citation2007) studied two hotels in Phuket in Thailand, with findings indicating that their CSR activities were related to issues that also promoted the destination's image. Bohdanowicz and Zientara (Citation2009) studied hotels’ CSR reporting using publicly available data from websites. They found that some hotels performed well and had, for example, CSR officers and policy documents, while others hardly did anything in this area at all. Font et al. (Citation2012) investigated the extent to which the CSR claims of ten global hotel chains (based in Asia, America/Caribbean, and the Mediterranean) were supported by evidence. They could see that larger hotel groups had more comprehensive policies but also greater gaps in their implementation, while smaller hotel groups focused only on environmental management and delivering what they had promised. The results from Font et al. (Citation2012) also showed that most hotel groups have a CSR nominee in each of their hotels, who could be either the chief engineer or the general manager, with CSR work as an additional task. CSR policies were found to be mostly inward looking, with little acceptance of the wider impacts caused in the destination, in contrast to Henderson’s (Citation2007) results. Other interesting results were that HR issues were not integrated into CSR strategies. Since Font et al. (Citation2012) made on-site visits, they also gathered evidence of CSR practices that exceeded policy requirements. Overall, they could see that there was a strong emphasis on environmental issues, most notably on energy and water management, which are areas where immediate cost savings can be gained. The hotel chains studied largely avoided anything that did not immediately benefit the business. The legal and economic concerns of stakeholders were more in focus than the ethical aspects.

Font et al. (Citation2016) studied 900 tourism companies in 57 European protected areas. The results showed that small companies are more involved in taking responsibility for their sustainability than previously expected, including eco-savings related operational practices as well as reporting a wide range of social and economic responsibility actions. The main reasons for acting sustainably among the respondents were To protect the environment (87%), A personal lifestyle choice (49%), and To improve our society (47%). Respondents overwhelmingly preferred to work with tasks they believe they can succeed in before they start (64%). The results also showed that older respondents more commonly reported the introduction of actions that lead to greater income or savings (in particular, environmental savings), while younger respondents were more likely to claim socioeconomic actions, such as staff salaries above the industry average and promoting gender equality. Based on their findings, Font et al. (Citation2016) divided the studied companies into three groups: Business-driven companies that implement primarily eco-savings activities and that are commercially oriented; Legitimization-driven companies that respond to perceived stakeholder pressure and report a broad spectrum of activities; and Lifestyle- and value-driven companies that report the greatest number of environmental, social, and economic activities. The legitimization-driven companies use sustainability actions to influence stakeholder perceptions as a way of gaining social capital, and the Lifestyle-driven companies report taking the most sustainability activities and performing these activities implicitly as part of their routine. As seen in other studies, Font et al. (Citation2016) concluded that the main motivations of companies were related to economic and financial goals, the owners’ lifestyles, and gaining legitimization in society.

Communicating sustainability to increase value and gain legitimacy

Legitimacy is society's acceptance of the behaviours of a company; there exists a “social contract” between a company and the society of which it is part (Deegan, Citation2000, Citation2002; Patten, Citation1991, Citation1992). Suchman (Citation1995, p. 574) defines legitimacy as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions”. For companies reporting their sustainability efforts, it is therefore important that they act according to what they say they will do.

Research claims that companies carry out sustainability reporting symbolically in order to gain legitimacy (Hooghiemstra, Citation2000; Richards et al., Citation2017). However, an ethical approach to business seems to have become increasingly important to business practice (Hitt et al., Citation2010), and changes in companies’ behaviours can be seen as a response to perceived legitimacy gaps (Archel et al., Citation2009). Research shows that it is not only economic drivers that make companies focus on sustainability; for example, owners with early life experiences of nature conservation and self-confident business owners were much more engaged in environmental improvement (Sampaio et al., Citation2012). Other aspects that can be important drivers for tourism SMEs in their decision making when going green are lifestyle, personal values and ethics, worldviews, self-efficacy beliefs, and goal orientation, as well as understanding the importance of context (Sampaio et al., Citation2012; Tzschentke et al., Citation2008). Companies in society also have a social role in terms of being a sustainable company over time (Matten & Crane, Citation2005) and performing an educational role. Research has shown the growing importance of tourism companies educating both current and future employees in sustainability (Pereira & Mykletun, Citation2017; Phi & Waldesten, Citation2021). Acting in accordance with business owners’ sustainability values will thereby create legitimacy for them and their tourism companies.

Font et al. (Citation2017) studied 31 accommodation businesses in the Peak District National Park in the UK and found that companies legitimized the fact that customers consume the landscape through the sustainability actions the businesses take on their behalf. The researchers found that only 30% of sustainability practices found in the audits were communicated on company websites and that companies used a different tone in their communications in audits compared to websites, since they did not want to discourage potential visitors. Previous studies have shown that national culture, company size, and in which industry they operate affect companies’ sustainability work (Sörensson et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b). Font et al. (Citation2017) found their evidence to be in line with corporate social disclosure literature that suggests that moral intensity and business salience increase the pressure to legitimize (Al-Tuwaijri et al., Citation2004; Deegan, Citation2002; Jones, Citation1991). The results revealed differences between the accommodation category and their level of sustainability communication: five-star businesses communicated 40% of their actions, four-star businesses 27%, and three-star businesses only 12%.

Value co-creation of sustainability with stakeholders

Value co-creation sees the stakeholders as co-creators of value through interaction (Galvagno & Dalli, Citation2014; Vargo & Lusch, Citation2004). With this perspective, a company no longer sees its customers, nor other stakeholders, as simply customers. Rather, customers are partners of interaction that, in a process, co-creates the value. Suppliers and customers are no longer on opposite sides, but rather they interact with each other to develop new business opportunities. With this perspective, sustainability might be seen as a potential value rather than a “problem” to deal with. Sustainability values can offer a competitive advantage. Previous research argues the difference between co-creation and co-production (Cova & Paranque, Citation2013; Galvagno & Dalli, Citation2014; Grönroos & Voima, Citation2013). For tourism companies, there are several stakeholders that interact in creating a good service for visiting tourists. In this co-creation process, rather than seeing sustainability as “rules” that cost the company money, tourism companies should see sustainability as a value. This value needs to be co-created between the company and its stakeholders.

One way to start the value co-creation process can be to present good sustainability information to the company's various stakeholders. The survival and growth of tourism companies depend on satisfied tourists who are offered unique and memorable experiences. Tourists’ expectations are constantly changing, and tourism companies must find ways to anticipate and respond to these expectations (Chathoth et al., Citation2013), which might include a more sustainable tourism experience. For instance, hotels are regarded as critical to customers’ experiences, and valuable insights can be made by applying the conceptual framework Service-Dominant Logic (S-D Logic) to the tourism industry (FitzPatrick et al., Citation2013). In S-D Logic, the co-creation of tourist experiences consists in experiences that are customized by tourists, which includes the sharing of experiences with each other (Wang et al., Citation2013). Payne et al. (Citation2008, p. 88) argue that:

Co-creation opportunities are strategic options for creating value. The types of opportunity available to a supplier are largely contingent on the nature of their industry, their customer offerings and their customer base. While customer research and innovation within the supplying organization should drive opportunity analysis, we suggest that suppliers consider at least three significant types of value co-creation opportunity:

opportunities provided by technological breakthroughs, opportunities provided by changes in industry logics, and opportunities provided by changes in customer preferences. Sustainability as a value might represent both a change in industry logic and a change in customer preferences (the issue of sustainability is important for today's customers and stakeholders of tourism companies). Sustainability information from the tourism companies and sustainability expectations from the tourists are therefore two angles in the co-creation process regarding sustainability value.

Summary and implications for this research paper

To sum up the conducted literature review, sustainability affects and influences all businesses today, but in different ways and to different extents. All three sustainability dimensions – economic, social, and environmental – should be taken into account when discussing sustainability. In our study, Cavagnaro and Curiel’s (Citation2012) proposed model is central and forms the starting point with its three levels focusing respectively on society, organizations, and leadership. Furthermore, Font et al.’s (Citation2016) results regarding what motivates companies (Business-driven, Legitimization-driven, or Lifestyle- and value-driven) are used in the analysis.

What motivates and drives companies to focus on sustainability varies, and therefore both the different aspects behind investing in sustainability actions and how and what they communicate internally and externally are of importance. To increase value for the company and in co-creation with stakeholders, companies can create legitimacy for their business. However, the communication to increase value for the company can be different depending on which stakeholder is targeted and involved in the interactive co-creation process.

Methodology

The study was designed as a qualitative multi-case study of tourism companies in Sweden, using an explorative approach to investigate the companies’ communication of sustainability. Sweden was recently ranked as the most sustainable destination in the world (Visit Sweden, Citation2021), which provides one reason for selecting companies based in Sweden. A strategic selection of companies was made, in order to capture different types of companies within the tourism industry, since earlier studies about sustainability have focused to a large extent on hotels. One important selection criterion was that these companies should be large enough to provide information about sustainability (via their webpages and/or in their annual reports). Other selection criteria were that each of the companies should have at least eight employees and a turnover exceeding 10 million SEK. These criteria ensured that the companies are large enough to focus on sustainability issues, even though not all of them must report sustainability by law. Additionally, it was aimed to include both smaller and larger companies in the sample, and to have a geographical spread of companies over the country (from south to north, including locations in both large cities and small villages). Sweden is divided into three regions based on geographical location from south to north, namely Götaland, Svealand, and Norrland (labelled south, middle, and north in this article). The companies were found through the website www.allabolag.se, where all limited companies in Sweden are listed. Data was then collected from 30 selected tourism service providers in Sweden (5 Destination Marketing Organizations or so-called DMOs, 6 ski resorts, 8 hotels, 5 entertainment organizations, and 6 travel agencies and tour operators). gives a short description of the companies included.

Table 1. Short description of the included cases.

The turnover of the studied companies ranged from 10 million SEK to 2.694 billion SEK. The smallest tourism company had eight permanent employees, and the largest had 1322 employees. They are located from the province of Skåne in the south to the province of Norrbotten in the north of Sweden.

Content analysis was used to analyse the content and the message communicated (Neuman & Kreuger, Citation2003). The analysis was performed in two steps. Firstly, annual reports, sustainability reports, websites, and other written documents available online were analysed through the three dimensions in the GRI model (see ). The content from the studied documents was categorized into economic, social, or environmental dimensions. The themes presented under each dimension were also used at this stage in order to sort the content further. These themes, presented in , are the fields that the GRI included in the mandatory sustainability reports within the EU.

Table 2. The three dimensions of sustainability reporting according to the GRI and its themes used for analysis (GRI, Citation2021).

The second step of the analysis identified patterns and similarities regarding what was communicated about sustainability and how. Second-order themes then appeared under each of the three dimensions of sustainability, and between the included types of tourism companies. Specific communication patterns based on the type of tourism company were identified to reveal which stakeholders are seen as value co-creators.

Findings and discussion

The results are presented in the following order: First, an overview is provided of what the tourism companies value as important issues in relation to the three dimensions of sustainability. Subsequently, an overview is given of which sustainability dimensions the different categories of tourism companies focus their information on. Finally, the issue of communication is discussed as a fourth layer of sustainability value. There is a discussion, from the stakeholders’ perspective, of sustainability communication and of how a tourism company can gain legitimacy through sustainability values.

The economic, social, and environmental sustainability communication as value

The studied tourism companies provided sustainability information in all three dimensions of sustainability.

For the economic dimension, the studied companies highlighted the importance of economic stability. The focus was on the theme economic results. They presented less information concerning the themes market presence or indirect economic impact from the GRI model. The tourism company “will be a driving player for sustainable tourism at the company's destinations with growth in the number of visitors” and “whose offering and efficient organization have provided continuous growth with stable profitability” (SR6).

Regarding the social dimension, the companies pointed out internal investments in staff to improve their wellbeing and external investments by supporting local projects or projects in developing countries. One company, for example, supported a project in Africa to reduce hunger and poverty. The companies stressed the importance of employment issues, and many of them they hired more people during the peak season. The five themes in the social dimension were addressed by the studied cases to varying degrees. “The staff develops competence continuously through internal training, study trips and initiatives from our partners around the world” (H6). This result is in line with Matten and Crane (Citation2005), who focused on the importance of being sustainable over time.

Regarding the environmental dimension, many of the studied cases had environmental certifications, such as ISO 14001. The studied cases presented the most information concerning environmental issues, which is in line with previous research (Font et al., Citation2012; GRI, Citation2021; Nikolaeva & Bicho, Citation2011). Environmental sustainability tends to be the dimension that is most often addressed. It is also the dimension that seems to be the easiest to measure; for example, one company stated, “We have reduced our energy consumption by 30%” (H4). Several of the tourism companies had clear environmental policies that they communicated to both employees and guests. One of the ski resorts (SR1) described their policy as follows: “Global warming and the footprint we make is an important part of our work in developing our facilities.” They highlighted that their environmental work is important for them from three aspects:

To contribute to and take responsibility for society and make our imprint as small as possible, to reduce costs and strain in the long run through efficient work, and that our guests should know that they have arrived at a destination that consciously works with sustainability issues.

The study should not be generalized to other settings, since the selection of cases is too limited, but it can nevertheless contribute to research into tourism companies’ ways of communicating sustainability values. The study indicates that tourism companies are well aware of the dimensions of sustainability values and that sustainability is a co-creation process between a tourism company and its stakeholders. The results show that integrating stakeholders (Buysse & Verbeke, Citation2003; O’Riordan & Fairbrass, Citation2008) in what they see as a sustainability value has been addressed by the studied companies. A concrete example of value co-creation is a ski resort that conducts an analysis together with its stakeholders. Stakeholder participation enables a company to work with long-term and sustainable solutions. These stakeholder dialogues have taken place through employee and guest surveys as well as through meetings and dialogue with suppliers, thus providing input into what stakeholders in society find important to address from the company's point of view (Baumgartner, Citation2014; McWilliams & Siegel, Citation2011). This example also shows that value creation is a co-creation process with the stakeholders (Galvagno & Dalli, Citation2014; Vargo & Lusch, Citation2004).

Sustainability communication – differences among the tourism companies

The results of this study indicate that the category of tourism companies influences what is seen as a sustainability value, which is in line with previous studies (Font et al., Citation2016; Font et al., Citation2017; Sörensson & Jansson, Citation2016). For example, it can be seen that DMOs are focused on providing information regarding the economic dimension, and hotels are focused to a large extent on the social dimension. Both hotels and restaurants are focused on the environmental dimension. The identified differences in the kind of sustainability issue that is focused on and communicated are visualized in .

Table 3. Type of tourism company and its sustainability work (own work).

The destination marketing organizations pay attention to the local market concerning economic sustainability. The focus concerning social sustainability is the organization's employees, which is thus an internal focus. They address environmental sustainability through concrete efforts.

The ski resorts address the issue of economic growth as it leads to possible expansion. The social dimension is often focused on in terms of the staff as value creators. Thus, this dimension has both an internal and external focus. The companies’ focus on their employees as members in the organization but also in order for them to create value for the customers. The environmental issues address areas that influence their business, such as access to water for snow making, as well as the environmental effects that such activity can have in the area.

The hotels focus on how to strengthen the value of their brand in order to achieve economic sustainability. Social sustainability emphasizes that employees should feel good at work and training. The communicated issue here has an internal focus, such as good working conditions, but externally and implicitly it lays bare the importance of doing a good job for the guests. The environmental aspect addresses issues mainly focused on four specific areas for the hotel industry: food, products, energy, and transport.

The entertainment organizations are interested in how to contribute to economic effects in nearby areas, for example by having employees live in nearby municipalities and thereby contributing to local tax incomes. Concerning the social dimension, these organizations pay attention to social projects taking place abroad. This is interesting, since such activity mainly has an external focus outside of the organization. From a legitimate point of view, caring for people in developing countries might look good. On the other hand, it is strange that their employees, who are an important part of providing good entertainment, are not mentioned or valued explicitly. They also pay attention to emissions, waste, and material selection concerning environmental issues.

Travel agencies and tour operators communicate that they want to create value that extends beyond purely economic value. The social dimension addresses issues concerning human rights elsewhere and gender issues. The interpretation here is that human rights focus mainly externally, and gender issues focus mainly internally. Regarding the environmental aspect, travel agencies and tour operators have a significant interest in climate issues.

Font et al. (Citation2016) argue that there are three different company groups, depending on what kind of sustainability action is taken: Business-driven companies, Legitimization-driven companies, and Lifestyle- and value-driven companies. To some extent, there are similarities to be seen among the studied tourism companies. For example, business-driven hotels and ski resorts focus on sustainable activities that are commercially oriented, and legitimization-driven travel agencies and tour operators meet stakeholders’ expectations in order to be environmentally friendly. However, the result from this study rather indicates that the context and the prerequisites of a tourism company may play a role in what tourist companies communicate to their stakeholders in order to gain legitimacy. One example is travel agencies who must address the issue of travelling, often by aeroplane, and the effects this has on the environment due to pollution. By addressing climate as an important factor, they respond to society's expectation (Chathoth et al., Citation2013). By communicating that they are aware of climate issues, they co-create value, since this issue is important for the tourists (Payne et al., Citation2008).

The fourth layer of sustainability – communicating sustainability and legitimacy

Previous research by Cavagnaro and Curiel (Citation2012) has shown that sustainability could be discussed from three perspectives (society, organization, and leadership). This study aims to address the importance of communicating sustainability values, and the results indicate that the figure could be used with an added fourth layer, namely sustainability communication (see ). The fourth layer is highly dependent on the other three layers, since the society's stakeholders as well as the organization itself need to address the issues of sustainability. The organization is influenced by its leaders as to how to work with sustainability issues in the organization. The fourth proposed communication layer is placed in the centre of the triangle surrounded by the other three layers. The communication is both internal (within the organization) and external (between the organization and different stakeholders in the society).

Figure 1. The four layers of sustainability.

Authors’ own work inspired by Cavagnaro and Curiel (Citation2012).

The results of this study show that tourism companies must have income (economic sustainability) so that they can “survive”. The companies must also focus on the social dimension and “share” with society: because “sharing is caring”. The environmental dimension is how to “sustain”. The theoretical contribution from this study is the proposed fourth layer, where communication is based on these three factors: survive, share, and sustain.

The results also indicate that the three sustainability dimensions (economic, social, and environmental) are connected. For instance, staff who are feeling well will work well, which positively affects the financial profit of the company. Environmental efforts give economic stability, and economic stability creates accountability towards the companies’ stakeholders. The value of environmental issues can provide a competitive advantage, since today's customers ask for a “greener” option, and therefore the behaviour of the company changes. Sustainability is not simply a marketing trick; it is a value that changes the behaviour of both tourism companies and their stakeholders. Tourism companies that pay attention to and take responsibility for sustainability in their annual reports can gain legitimacy in doing so (Deegan, Citation2000, Citation2002).

When viewing the results with a focus on stakeholders, it is evident that there is a focus on social sustainability for internal stakeholders, such as the staff and the local community. For the external stakeholders, the focus is on environmental sustainability, such as having suppliers and partners who operate in an environmentally friendly manner and are certified. Certifications with the right standards can be one way to strengthen the legitimacy of a company. Additionally, this also focuses on the customers, highlighting the company's environmental sustainability. Regarding economic sustainability, this can be seen as a prerequisite to delivering good annual reports. If good annual reports are not delivered, a company will lose shareholders and investors.

Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to explore the sustainability values that tourism companies communicate to their stakeholders. The overall conclusion from this small case study is that sustainability as a value is communicated by Swedish tourism companies to their stakeholders.

What sustainability values (economic, social, and environmental) do tourism companies focus on and communicate in their sustainability information? The conclusion is that the information is often about the social and environmental dimensions in the GRI model. Regarding economic sustainability, companies seem to simply show their numbers, but they do not really think of these themes as sustainability values. However, this dimension is important and crucial to a company's survival. Concerning social sustainability, the studied companies address the five themes in the GRI model. Not all companies address all five themes, but there is a common knowledge that social sustainability includes more than just giving money away. Social issues are important both for a company's employees and for the society in which the company is based.

Are there differences between different types of tourism companies in terms of what they communicate concerning sustainability towards stakeholders to gain legitimacy? The conclusion is that the context and prerequisites for each type of tourism company govern what they work with in order to meet demands from stakeholders.

Previous studies have shown different layers of sustainability, and the theoretical contribution from this study is that a fourth layer might be added, focused on sustainability communication regarding how to survive, share, and sustain. A company must have earnings or other types of revenues in order to exist, and therefore the communication about economic values is focused on survival. The second part of the fourth layer is social value. This part addresses issues that are often internal, such as how tourism companies work with their staff (internal issues). It might also concern external issues that are connected to the surrounding society. This part is therefore labelled share. The third part is environmental issues for us all to sustain. A key aspect here is that many tourism companies use certifications, such as ISO 14001, to obtain legitimacy. Many different environmental certifications seem to be in existence, which can be national or international and can also be specific to subindustries.

A practical implication of this study is that it could inspire tourism companies who would like to broaden their sustainability efforts into more dimensions. Another implication is that tourism companies should see sustainability as a value that is co-created with their stakeholders. It is also of importance to communicate the kind of sustainability efforts tourism companies make towards their stakeholders.

This is a small study, which could be extended in the future. Currently, it can be used as inspiration for extended future studies investigating the differences between different types of companies within the tourism industry, both nationally and internationally.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alla bolag. https://www.allabolag.se/

- Al-Tuwaijri, S. A., Christensen, T. E., & Hughes Ii, K. E. (2004). The relations among environmental disclosure, environmental performance, and economic performance: A simultaneous equations approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(5-6), 447–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(03)00032-1

- Anderson, J. C., & Narus, J. A. (1998). Business marketing: Understand what customers value. Harvard Business Review, 76, 53–67.

- Aquilani, B., Silvestri, C., Ioppolo, G., & Ruggieri, A. (2018). The challenging transition to bio-economies: Towards a new framework integrating corporate sustainability and value co-creation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 4001–4009. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.153

- Aras, G., & Crowther, D. (2008). Evaluating sustainability: A need for standards. Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting, 2(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22164/isea.v2i1.23

- Archel, P., Husillos, J., Larrinaga, C., & Spence, C. (2009). Social disclosure, legitimacy theory and the role of the state. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 22(8), 1284–1307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570910999319

- Bani-Khalid, T. (2020). Examining the quantity and quality of online sustainability disclosure within the Jordanian industrial sector: A test of GRI guidelines. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 17(4), 141–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21511/ppm.17(4).2019.12

- Baumgartner, R. J. (2014). Managing corporate sustainability and CSR: A conceptual framework combining values, strategies and instruments contributing to sustainable development. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 21(5), 258–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1336

- Bohdanowicz, P., & Zientara, P. (2009). Hotel companies’ contribution to improving the quality of life of local communities and the well-being of their employees. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 9(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/thr.2008.46

- Breuer, H., Fichter, K., Lüdeke-Freund, F., & Tiemann, I. (2018). Sustainability-oriented business model development: Principles, criteria and tools. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 10(2), 256–286. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEV.2018.092715

- The Brundtland Commission Report. Brundtland, G. H., Khalid, M., Agnelli, S., Al-Athel, S., & Chidzero, B. J. N. Y. (1987). Our common future. New York, 8.

- Buysse, K., & Verbeke, A. (2003). Proactive environmental strategies: A stakeholder management perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 24(5), 453–470. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.299

- Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1979.4498296

- Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society, 38(3), 268–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/000765039903800303

- Cavagnaro, E., & Curiel, G. H. (2012). The three levels of sustainability. Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351277969

- Chathoth, P., Altinay, L., Harrington, R. J., Okumus, F., & Chan, E. S. (2013). Co-production versus co-creation: A process based continuum in the hotel service context. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 32, 11–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.03.009

- Cormier, D., Gordon, I. M., & Magnan, M. (2004). Corporate environmental disclosure: Contrasting management’s perceptions with reality. Journal of Business Ethics, 49(2), 143–165. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000015844.86206.b9

- Cova, B., & Paranque, B. (2013). Value Capture and Brand Community Management. Available at SSRN 2233829. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2233829

- Dahlsrud, A. (2008). How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.132

- Deegan, C. (2000). The triple bottom line [What the good guys are putting in the annual report. Edited extract of a paper presented at the Securities Institute of Australia. Seminar (2000: Sydney).]. JASSA: The Journal of the Securities Institute of Australia (3), 12–14. https://search.informit.org/doi/https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.200101763

- Deegan, C. (2002). Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures–a theoretical foundation. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15(3), 282–311. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570210435852

- Deegan, C., & Rankin, M. (1997). The materiality of environmental information to users of annual reports. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 10(4), 562–583. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09513579710367485

- De Grosbois, D. (2012). Corporate social responsibility reporting by the global hotel industry: Commitment, initiatives and performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 896–905. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.10.008

- Dowling, J., & Pfeffer, J. (1975). Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizational behavior. Pacific Sociological Review, 18(1), 122–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1388226

- Elhauge, E. (2005). Sacrificing corporate profits in the public interest. NyUL Rev, 80, 733.

- Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks. The triple bottom line of 21st century, 73.

- European Commission. (2002). COM 2002/347. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2002:0347:FIN:EN:PDF

- FitzPatrick, M., Davey, J., Muller, L., & Davey, H. (2013). Value-creating assets in tourism management: Applying marketing’s service-dominant logic in the hotel industry. Tourism Management, (36), 86–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.11.009.

- Font, X., Elgammal, I., & Lamond, I. (2017). Greenhushing: The deliberate under communicating of sustainability practices by tourism businesses. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(7), 1007–1023. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1158829

- Font, X., Garay, L., & Jones, S. (2016). Sustainability motivations and practices in small tourism enterprises in European protected areas. Journal of Cleaner Production, 137, 1439–1448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.01.071

- Font, X., Walmsley, A., Cogotti, S., McCombes, L., & Häusler, N. (2012). Corporate social responsibility: The disclosure–performance gap. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1544–1553. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.02.012

- Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B. L., & De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Cambridge University Press.

- Freudenreich, B., Lüdeke-Freund, F., & Schaltegger, S. (2020). A stakeholder theory perspective on business models: Value creation for sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 166(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04112-z

- Galvagno, M., & Dalli, D. (2014). Theory of value co-creation: A systematic literature review. Managing Service Quality, 24(6), 643–683. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/MSQ-09-2013-0187

- Gatti, L., & Seele, P. (2014). Evidence for the prevalence of the sustainability concept in European corporate responsibility reporting. Sustainability Science, 9(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-013-0233-5

- Gössling, S. (2013). National emissions from tourism: An overlooked policy challenge? Energy Policy, 59, 433–442. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.03.058

- Gössling, S., & Hall, C. M. (2008). Swedish tourism and climate change mitigation: An emerging conflict? Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 8(2), 141–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250802079882

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2013). Challenges of tourism in a low-carbon economy. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 4(6), 525–538. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.243

- GRI. (2021). https://www.globalreporting.org/, accessed 2021-04-04

- Grönroos, C., & Voima, P. (2013). Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-012-0308-3

- Hall, C. M., & Saarinen, J. (2021). 20 years of Nordic climate change crisis and tourism research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1823248

- Harrison, J. S., Freeman, R. E., & Abreu, M. C. S. D. (2015). Stakeholder theory as an ethical approach to effective management: Applying the theory to multiple contexts. Revista Brasileira de Gestão de Negócios, 17(55), 858–869. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7819/rbgn.v17i55.2647

- Henderson, J. C. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and tourism: Hotel companies in Phuket, Thailand, after the Indian ocean tsunami. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 26(1), 228–239. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2006.02.001

- Hess, D. (2008). The three pillars of corporate social reporting as new governance regulation: Disclosure, dialogue, and development. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18(4), 447–482. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5840/beq200818434

- Hitt, M. A., Haynes, K. T., & Serpa, R. (2010). Strategic leadership for the 21st century. Business Horizons, 53(5), 437–444. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2010.05.004

- Hooghiemstra, R. (2000). Corporate communication and impression management–new perspectives why companies engage in corporate social reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 27(1-2), 55–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006400707757

- Ioannides, D., Gyimóthy, S., & James, L. (2021). From liminal labor to decent work: A human-centered perspective on sustainable tourism employment. Sustainability, 13(2), 851. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020851

- Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1991.4278958

- Karen, P. (2008). Corporate sustainability, citizenship and social responsibility reporting: A website study of 100 model corporations. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 32, 63–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/jcorpciti.32.63

- Lüdeke-Freund, F. (2020). Sustainable entrepreneurship, innovation, and business models: Integrative framework and propositions for future research. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(2), 665–681. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2396

- Lundberg, C., & Furunes, T. (2021). 20 years of the Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism: Looking to the past and forward. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1883235

- Matten, D., & Crane, A. (2005). Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 166–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2005.15281448

- McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. S. (2011). Creating and capturing value: Strategic corporate social responsibility, resource-based theory, and sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 37(5), 1480–1495. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310385696

- Müller-Christ, G., & Hülsmann, M. (2003). Erfolgsbegriff eines nachhaltigen Managements. In Handbuch nachhaltige Entwicklung (pp. 245–256). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-10272-4_23

- Neuman, W. L., & Kreuger, L. (2003). Social work research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Allyn and Bacon.

- Nikolaeva, R., & Bicho, M. (2011). The role of institutional and reputational factors in the voluntary adoption of corporate social responsibility reporting standards. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 136–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0214-5

- O’Riordan, L., & Fairbrass, J. (2008). Corporate social responsibility (CSR): Models and theories in stakeholder dialogue. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(4), 745–758. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9662-y

- Patten, D. M. (1991). Exposure, legitimacy, and social disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 10(4), 297–308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4254(91)90003-3

- Patten, D. M. (1992). Intra-industry environmental disclosures in response to the Alaskan oil spill: A note on legitimacy theory. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(5), 471–475. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(92)90042-Q

- Payne, A. F., Storbacka, K., & Frow, P. (2008). Managing the co-creation of value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0070-0

- Pereira, E. M., & Mykletun, R. J. (2017). To what extent do European tourist guide-training curricula include sustainability principles? Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 17(4), 358–373. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2017.1330846

- Phi, G. T., & Waldesten, T. (2021). Educating sustainability through hackathons in the hospitality industry: A case study of Scandic hotels. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(2), 212–228. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1879669

- Postma, A., Cavagnaro, E., & Spruyt, E. (2017). Sustainable tourism 2040. Journal of Tourism Futures, 3(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-10-2015-0046

- Richards, M., Zellweger, T., & Gond, J. P. (2017). Maintaining moral legitimacy through worlds and words: An explanation of firms’ investment in sustainability certification. Journal of Management Studies, 54(5), 676–710. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12249

- Romero, S., Ruiz, S., & Fernandez-Feijoo, B. (2019). Sustainability reporting and stakeholder engagement in Spain: Different instruments, different quality. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(1), 221–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2251

- Rowbottom, N., & Lymer, A. (2009, June). Exploring the use of online corporate sustainability information. Accounting Forum 33(2), 176–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2009.01.003

- Salvioni, D., & Gennari, F. (2017). CSR, sustainable value creation and shareholder relations. Symphonya. Emerging Issues in Management (symphonya. unimib. it), 1(1), 36–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4468/2017.1.04salvioni.gennari

- Sampaio, A. R., Thomas, R., & Font, X. (2012). Why are some engaged and not others? Explaining environmental engagement among small firms in tourism. International Journal of Tourism Research, 14(3), 235–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.849

- Sanchez, J., Callarisa, L., Rodriguez, R. M., & Moliner, M. A. (2006). Perceived value of the purchase of a tourism product. Tourism Management, 27(3), 394–409. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.11.007

- Schaltegger, S., Burritt, R., & Petersen, H. (2017). An introduction to corporate environmental management: Striving for sustainability. Routledge.

- Sörensson, A. (2014). Can tourism be sustainable. Service experiences from tourism destinations in Europe. School of Business and Economics. Åbo Akademi University.

- Sörensson, A., Bogren, M., & Cawthorn, A. (2019a). Sustainability information in large-sized companies in Europe: Does national culture matter? The International Journal of Sustainability in Economic, Social and Cultural Context, 15(1), 45–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18848/2325-1115/CGP/v15i01/45-62

- Sörensson, A., Bogren, M., & Schmudde, U. (2019b). How do cities of different sizes in Europe work with sustainable development? International Journal of Design & Nature and Ecodynamics, 14(4), 287–298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2495/DNE-V14-N4-287-298

- Sörensson, A., Bogren, M., & Schmudde, U. (2021). Effects of the coronavirus pandemic on Swedish tourism firms and their sustainability values. In A. Sörensson, B. Tesfaye, A. Lundström, G. Grigore, & A. Stancu (Eds.), Corporate responsibility and sustainability during the Coronavirus crisis (pp. 77–101). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73847-1_5

- Sörensson, A., & Jansson, A. M. (2016). Sustainability reporting among Swedish tourism service providers: Information differences between them. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, 1, 103–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2495/ST160091

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9508080331

- Tzschentke, N. A., Kirk, D., & Lynch, P. A. (2008). Going Green: Decisional factors in small hospitality operations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27(1), 126–133. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2007.07.010

- UN. (2021). Retrieved April 5, 2021, from https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Unerman, J. (2000). Reflections on quantification in corporate social reporting content analysis. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 13(5), 667–681. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570010353756

- Van Marrewijk, M., & Werre, M. (2003). Multiple levels of corporate sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(2-3), 107–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023383229086

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.1.1.24036

- Visit Sweden. (2021). Press release, March 13, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021, from https://www.mynewsdesk.com/se/visitsweden/pressreleases/sverige-aer-vaerldens-haallbaraste-turistdestination-3081344

- Wang, D., Li, X. R., & Li, Y. (2013). China’s “smart tourism destination” initiative: A taste of the service-dominant logic. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2(2), 59–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.05.004

- Zeithaml, V. A., Verleye, K., Hatak, I., Koller, M., & Zauner, A. (2020). Three decades of customer value research: Paradigmatic roots and future research avenues. Journal of Service Research, 23(4), 409–432. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520948134