ABSTRACT

This paper analyses behavioural patterns related to sustainable consumption and ecotourism, using the theoretical framework of Pierre Bourdieu referring to social differentiation expressed through consumption. Our goal is to evaluate how the theoretical approach of Bourdieu can be used to analyse sustainable consumption in the tourism sector. We address this question by determining how different types of capital influence consumer choices. Firstly, we analyse the theoretical assumptions of Pierre Bourdieu’s framework relating to sustainable consumer choices using content analysis. Secondly, we conduct semi-structured expert interviews. Thirdly, we examine a case study of ecotourism. The results show that sustainable consumption in tourism is present in all social classes through diversified behaviour, although motivations for it differ considerably, and a minimum amount of a cultural capital is necessary. Based on Bourdieu’s framework, we derive four assumptions related to sustainable consumption subsequently confirmed in the interviews and the case study of ecotourism. The findings of this study provide a better understanding of factors influencing sustainable consumption, and will be useful for researchers, policymakers and business practitioners.

Introduction

Sustainability and interconnections between humans and nature have become one of the most pressing topics in tourism research (Fredman & Margaryan, Citation2021). Progressing climate change and the current crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic stresses the importance of a transition to more sustainable behaviour (Hall & Saarinen, Citation2021; Ianioglo & Rissanen, Citation2020). There is a growing body of literature that focuses on various factors influencing sustainable choices, which can be broadly classified as economic (Lissner & Mayer, Citation2020), cultural, nature-related (Breiby et al., Citation2020), and psychological (Doran et al., Citation2017). Despite various studies analysing attitudes towards sustainability issues and motivations for environmental responsibility, few authors focus on applicable social theories (Sandve & Øgaard, Citation2013). Consequently, it is important to deepen our understanding of factors influencing sustainable consumer decisions, especially in relation to tourism.

The main research question of this paper is how the theory of Pierre Bourdieu can improve our understanding of sustainable consumer behaviour. While other researchers have used his framework to analyse the influence of reduced consumption on wellbeing (Jackson, Citation2005) and extraordinary experiences (Goolaup & Mossberg, Citation2017), we investigate a novel application of Bourdieu’s framework to explore how different types of capital influence consumer choices related to sustainable consumption based on the case of ecotourism.

We argue that the social theory of Bourdieu provides a valuable perspective on factors influencing sustainable consumption and that a framework developed based on his theory can be utilised to explain motivations for choosing various types of sustainable consumption, for example, ecotourism.

We begin with introducing the concept of sustainable consumption to understand its importance for current societal challenges. Further in the study, we use the example of ecotourism, a subtype of sustainable tourism, to exemplify our theoretical assumptions. Then, we introduce key concepts of Bourdieu’s social theory, including relations, field, habitus, capitals and doxa. We focus on particular on different types of capital and how they support reproduction of sustainable or unsustainable practices.

Theoretical framework

Sustainable consumption and ecotourism

When the United Nations announced 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, responsible production and consumption were chosen to be one of them (SDG 12). While the number of sustainable consumers around the world is increasing rapidly, this process does not entail a reduction in consumption per se. However, sustainable consumer behaviour, such as water and energy saving, recycling, choosing organic products, or boycotting certain products due to environmental concerns, has a substantial impact on the economy, including the tourism industry. Therefore, factors influencing consumers’ choices have become crucial points for investigation.

Sustainable consumption, defined as

the use of goods and services that respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life, while minimizing the use of natural resources, toxic materials and emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle, so as not to jeopardise the needs of future generations. (IISD, Citation1994, p. 4)

Unpacking Bourdieu’s framework

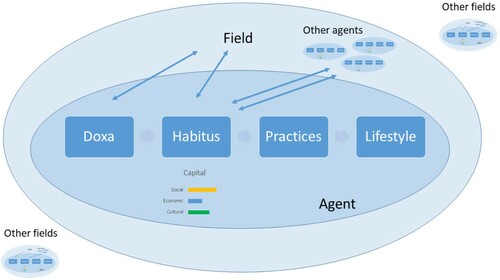

Pierre Bourdieu is a French sociologist who created a consistent framework describing social classes, their preferences, and life choices. Bourdieu uses his own system of concepts to describe relations between people (called agents) and their specific characteristics. These concepts, including relations, field, habitus, capitals, and doxa, are explained in several publications by Pierre Bourdieu (Bourdieu, Citation1984, Citation1998; Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992). Using these constructs, he creates a universe that allows the analysis of agents’ choices and underlying motives (see ).

In his works, Pierre Bourdieu emphasizes the relational philosophy of science. The relation is understood as a link and dependence between objective field structures and inner structures of habitus. For example, a distinction is a variation of certain distinctive features which may be grasped only in relation to other features, serving as a point of reference (Bourdieu, Citation1998, p. 6). In the context of ecotourism, people choose it because they are able to distinguish it from other types of tourism. In this way, Bourdieu gives us a fulcrum and benchmark, which allows defining connections in his system. Relations play an important role in defining mutual interactions between the field and habitus, which will be described later.

A second fundamental construct for Pierre Bourdieu is a field. It is a global social space where agents with goals depending on social position confront each other and, as a result, strain or change the field’s structure (Bourdieu, Citation1998, p. 32). It can be compared to a magnetic field influencing the objects within its reach, which also interact with each other. It can be also compared to a game, which has a certain theme and rules, which the players obey. These players accept the game by the mere fact of taking part in it. The strategies of the agents in the field depend on their position, that is, the distribution system of specific capital, and their field perception (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992, pp. 82–86). In this paper, sustainable consumption and ecotourism are considered fields.

Bourdieu states that “the habitus is this generative and unifying principle which retranslates the intrinsic and relational characteristics of a position into a unitary lifestyle, that is, a unitary set of choices of persons, goods, practices” (Bourdieu, Citation1998, p. 8). The relationship between the habitus and the field is a relationship of conditioning: the field shapes the habitus, which in return participates in building the field. Habitus only reveals itself in a situation with a specific relationship. Depending on the space and the field, the same habitus can give rise to different and even opposing practices (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992, pp. 111–123). For example, a person may decide to choose an ecotourism option during the holidays but not purchase ecologically friendly products in everyday life. Explaining the style, understood as a system of distinctive choices and practices (Bourdieu, Citation1984, p. 217), is one of the habitus’ main functions (Bourdieu, Citation1998, p. 8). This concept applies well to sustainable consumption, which may be perceived differently by agents depending on their habitus. For example, one type of good or service may seem distinctive to one, pretentious to others and common to yet another. The conditions vary among the agents influencing habitus and, consequently, practices, followed by lifestyle. The habitus is thus an underlying and inner source of external behaviour and practices expressed by agents. Habitus seems natural for the agents. As Bourdieu puts it

(…) a practical sense, that is, an acquired system of preferences, of principles of vision and division (what is usually called taste), and also a system of durable cognitive structures (which are essentially the product of the internalization of objective structures) and of schemes of action which orient the perception of the situation and the appropriate response. The habitus is this kind of practical sense for what is to be done in a given situation – what is called in sport a “feel” for the game, that is, the anticipating the future of the gamer which is inscribed in the present state of play (Bourdieu, Citation1998, p. 25).

Cultural capital is the resource deriving from the education, family background and history, and socialization into the cultural institutions of a given society. Social capital is the sum of current and potential resources that belong to an individual or group due to having a permanent, more or less institutionalized network of relationships, knowledge and mutual recognition. It is the sum of capital and power that the network can mobilize (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992, pp. 104–105). Economic capital is not defined per se by Bourdieu but is relatively easy to measure objectively by the number of assets and liabilities, which are countable and expressed in monetary terms. Its indicators can be income, savings, and other financial assets like real estate. Finally, any type of capital can become symbolic capital, when it is perceived by categories of perception and classification schemes that at least partly result from the internalization of objective structures of a given field. Symbolic capital allows agents to recognize differences and assign an appropriate value (Bourdieu, Citation1998, p. 122), and grants an agent a specific logic. The distribution of the symbolic capital tends to either maintain or transform the structure of this distribution and thus keep the rules of the game in play or change them (Bourdieu, Citation1998, p. 34).

The Bourdieuan analysis does not address environmental capital directly. Environmental capital could be defined as a knowledge about the environment, interdependencies between humans and nature, as well as awareness of positive and negative environmental consequences of human behaviour (Karol & Gale, Citation2004, p. 5). This knowledge and awareness however, has to be followed by a set of certain skills to be translated into a practice (Fien, Citation1993, p. 71). Environmental capital can be classified as a part of cultural capital acquired through socialization and education. The amount of cultural, including environmental, capital one possesses will further determine social and economic capital (Bourdieu & Richardson, Citation1986, p. 247). According to Karol and Gale (Citation2004), an agent must have a habitus of sustainability to be able to use its environmental capital. As mentioned before, habitus is not static and changes in relation to a field producing different practices depending on the situation. For example, if an agent is informed that watching animals without keeping a distance is dangerous for them or himself/herself, he/she will most probably change his/her behaviour. The currently dominant unsustainable habitus is a result of human history “from which the environment has been viewed as a place to visit, or a resource, or something to buy, or something beautiful to be admired, and not a living organism whose balance must be maintained for our survival” (Karol & Gale, Citation2004, p. 5). According to Bourdieu’s framework, these unsustainable actions could be reproduced due to the culturally reproductive tendencies of the habitus and high values associated with unsustainable forms of capital accumulation. The environmental capital has not had enough time to influence the habitus of most of the agents since the corresponding environmental knowledge has only been widely available for the last few decades and is not fully implemented in various stages of education and culture (Karol & Gale, Citation2004, p. 5).

Last but not least, Bourdieu uses doxa, which is a special (universal) point of view. Doxa can be compared to consciousness. A common doxa can be shaped through a same or similar socialization and internationalization of the structures of the symbolic goods (Bourdieu, Citation1998, p. 160). If the doxa with regard to the ecotourism is shaped as a dominating view, it will seem natural to the agents to prioritize environmental protection in their choices. Some agents may have an epistemic doxa, which allows them to have their own view point, commonly expressed as “thinking out of the box” (Bourdieu, Citation1998, p. 163). An example would be choosing a small ecotourism stay when the majority prefers conventional package holidays.

A way forward to change doxa and influence habituses of actors are the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals with measurable targets referring to various types of capital. According to the United Nations’ World Tourism Organization, tourism can contribute to a more sustainable future by SDGs 8, 12 and 14 (UNWTO, Citation2021). In this paper, we zoom in on factors influencing sustainable consumer choices (SDG 12) which can be explained by Bourdieu’s framework.

The social theory of Bourdieu includes many different aspects. In this study, we focus on how various types of capital influence consumer choices. To reach this aim, we employ the research methods described in the following section.

Research methods

Research question and motivation

The main research question of this article is how different types of capital identified by Bourdieu influence consumer choices related to sustainable consumption using the example of ecotourism. The dependent variable in this study is sustainable consumption and its particular example of ecotourism. The independent variables are cultural, social and economic capital derived from the Bourdieu’s framework.

The interpretation of Bourdieu’s social theory enabled us to analyse what factors in advanced capitalist societies contribute to sustainable consumer choices and how this knowledge can be applied to the field of ecotourism. Application of grounded theory allowed us to formulate assumptions to be compared with the interviews. Expert interviews were chosen as a method because they offer an opportunity to grasp overarching patters which are related to the general topic of sustainable consumption. The case study of ecotourism was selected to exemplify this overarching scheme and therefore was not included in the interviews.

Research process: data collection and analysis

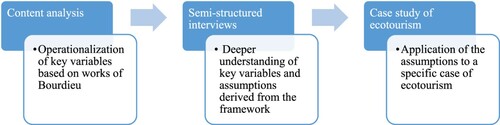

To answer the main research question, the following research process was applied (see ).

Firstly, we analysed the theoretical assumptions of Pierre Bourdieu’s framework relating to sustainable consumer choices. To understand what factors influence sustainable consumption choices, we applied an inductive approach based on the grounded theory. Grounded theory was used to discover new theoretical insights and deepen understanding of the phenomenon (Charmaz, Citation2006). The behavioural patterns for analysis were selected based on a content analysis of Bourdieu’s publications: “Practical reason” (Citation1998), “Distinction” (Citation1984) and “An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology” (Citation1992). The theory presented in these works was used for operationalization of the key terms, including types of capitals and deriving assumptions for further analysis.

Secondly, we conducted interviews with experts to better understand the role of the chosen types of capital and chosen assumptions. The interviews were conducted between February and March 2018 and lasted between 50 and 90 min. The interviews were conducted in person (one), via Skype (two) and email (two), depending on the respondents’ availability. Our respondents are five experts selected among academics who have experience in the field of sustainable consumption. Their selection was based on their appearance in recent publications and conferences in the field. We also applied the Peer Esteem Snowballing (PEST) method, which is often used for collecting data from experts and interconnected groups (Christopoulos Citation2009). The interviewees were assigned codes from E1 to E5. The questionnaire was developed and tested during a pilot interview. Some examples of questions derived from the assumptions and asked in the interviews included:

Studies on green consumption mention a wide variety of influencing factors. Which do you consider most important and meaningful currently?

Pierre Bourdieu mentions cultural capital as one of the key factors. To what extent does it apply to green consumption habits in your opinion?

People with higher incomes have a greater possibility to purchase green products and services. To what extent does this pattern hold for different classes? Is it possible to belong to a lower class and still be a green consumer? Why (not)?

What is an effect of social relations on green consumer behaviour?

In your opinion, in which way can green consumer behaviour be inherited or impeded because of family and surroundings?

“Green” and “sustainable” consumption were treated as synonyms in this study.

The interview process complied with ethical considerations, including voluntary participation, informed consent, confidentiality and anonymity. The quotations, which were essential for the analysis, were confirmed with the respondents.

The interviews were transcribed and coded using the Altas.ti software. Since this study is part of a broader project, we selected only the information which directly applies to the topic of this paper. The coding was conducted by the author. The first cycle coding involved three stages: open coding and line-by-line coding (defining actions and events represented by the codes) as well as structural coding to label concepts that appeared in the interviews. Second-cycle coding methods included axial coding (connecting sub-categories), focused coding (for categorization), and selective coding (integrating various categories) (Saldaña, Citation2021; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). As a result of this process, some codes and code groups were merged and reduced. The findings are presented according to the main emerging themes corresponding with the assumptions.

Third, we examined the case study of ecotourism and assess its fit within the framework. The case of ecotourism was selected as Bourdieu refers to it in its works, which enabled direct comparisons. The theoretical analysis of this case in Bourdieu’s publications was compared with other studies on ecotourism. It was supplemented with analysis based on four assumptions derived from the theory and interviews and current examples of ecotourism activities.

Results

The findings are presented according to the methods used. Firstly, we present emerging themes related to sustainable consumption in Bourdieu’s theory. Secondly, we show how they were reflected in the interviews. Thirdly, we use a case study of ecotourism to link Bourdieu’s theory to current examples.

Distinction by sustainable consumption

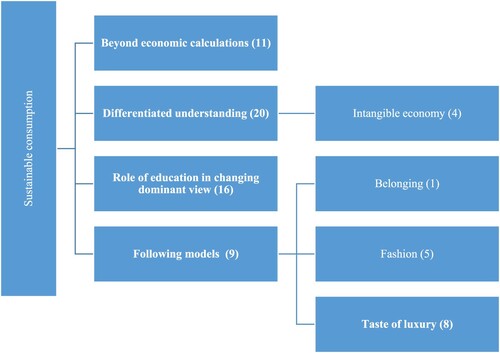

Besides the level of three types of capital, agents in the Bourdieu’s theory differentiate themselves through different consumption patterns that can be further used for explaining behavioural factors in sustainable consumption. Based on the content analysis of Bourdieu’s works, we identified four themes that can be relevant to sustainable consumption:

Beyond economic calculations: Agents are not always rational in a purely economic sense with regard to sustainable consumption. (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992).

Differentiated understanding: Agents define sustainable products and services differently. The same goods may have various meanings for different people depending on their background (cultural capital). Bourdieu shows that the symbolic component of the good has everything to do with its relation to the social being of the consumers (Bourdieu, Citation1984, p. 19; Elliott, Citation2013, p. 301).

Role of education: Bourdieu proves that the education system reproduces the distribution of cultural capital and, as a consequence, the structure of social space. The reproduction of capital is made stronger by the synergistic effect of educational entities and families which act as corporate bodies (Bourdieu, Citation1998, pp. 19–20). Therefore, education for sustainable consumption can sustain the status quo or rather stimulate changes in this direction. In this way, it has a power to change doxa (a dominant view). If the doxa about sustainable consumption is shaped as a dominating view, it will seem natural to the agents, as environmental protection is in, for example, the Netherlands or Nordic countries.

Following models: According to Bourdieu, the production field and the consumption field can become the subject of orchestration (Bourdieu, Citation1984, p. 288) understood as deliberate steering, through a trickle-down effect. (Bourdieu, Citation1984, p. 290). In the field of sustainable consumption, slow food and slow life movement became first popular among the upper class and are subsequently followed by the other parts of the society. It could be not only an intentional search for the difference but also choosing slow food in line with their habitus. For example, deconsumption may be perceived as a form of consumer aristocratism that is most likely at the root of the numerous condemnations of the “consumer society”, which are oblivious to the fact that condemnation of consumption is a consumer idea (Bourdieu, Citation1984, p. 318). Additionally, sustainable products and services are starting to be perceived as luxurious, thus having a higher value than past unsustainable practices.

We argue, therefore, that the key factor for the sustainable consumption is a high level of the cultural capital (including environmental capital) which comes across in all four themes. The levels of economic and social capital are secondary. The four themes derived from the works of Bourdieu can be connected to overarching themes appearing in the interviews.

Interviews

The analysis of the interviews revealed a number of behavioural patterns related to sustainable consumption, which are in line with agents’ behaviour in Bourdieu’s theory. summarizes code groups related to the patterns, which appeared throughout the analysis.

Beyond economic calculations

The interviews suggest that sustainable consumers are likely to think in terms of rationality beyond financial terms. Interviewee E2 mentioned that sustainable consumers are rational on three levels: economic (good value for the price), social (supporting social cause) and environmental (low environmental footprint). According to her, sustainable consumers also need to be divided into two groups: the conscious/educated (smaller group) and those following current fashion (larger group). It can be interpreted as the first group following the indication of their cultural capital and the second group following their social capital. As E2 says: “The cultural capital is visible in things we have in our environment.” By buying the latest versions of products, consumers distinguish themselves and send a signal to their network.

Consumer boycotts also appear in the context of actions beyond economic calculations taking into account high awareness (environmental capital). “Some consumers who do not agree with the actions of a certain enterprise deliberately decide to boycott certain products. However, this requires awareness, education and action” (E2). These elements mentioned by E2 lead to the possession of cultural capital.

Differentiated understanding

Differentiated understanding of sustainable consumption is the next concept that emerges from the interviews. The experts relate it to various types of capital. For example, according to E1, depending on their amount of economic capital, agents will choose products in a fashionable shop in a beautiful packaging (again as a sign of distinction) or on the local market directly from the producer. Both will be considered sustainable.

E2 suggests that the choices will also depend on the amount of cultural capital (E2). Many new types of institutions have recently appeared, for example, freeganism, food sharing initiatives, clothes swapping, minimalism or new cooperatives. These examples of a sharing economy are sometimes understood as more sustainable than buying brand new certified clothes. A transition to intangible goods come up often in the interviews. Some physical goods are disappearing, being replaced by services (E3). In this context, the interviewees mention tourism activities instead of purchasing goods.

Another aspect is a post-purchase behaviour matter as well: a sustainable consumer has to maintain these products in good condition (E2). Also, E4 highlights that sustainable consumption is not about the type of products bought but the way they are being used. Often sustainable consumers do not fit the profile of affluent middle class (E4). According to E5, it is always possible for people with a low amount of economic capital to consume in a greener way.

Role of education in changing the dominant view

Another overarching concept emerging from the interviews is reference to the role of education in changing the unsustainable consumption patterns. According to E1, education is a key instrument in shaping our attitude and choices. It has to be thought-through (having a strategic goal) and integrated (not only in the education system but also in media campaigns). E3 highlights that it has to come along with societal and economic development.

If a consumer who tries to be sustainable is uneducated, he can be convinced by any product or service named as “eco”, no matter what stands behind it (E2). Education also provides a benchmark and gives a point of distinction.

The interviews confirm that family can be also a source of education. Much of the agents’ habits are created at home. However, it often takes the reverse direction when parents are taught by their children bringing environmental education from schools (E2).

Cultural capital and social capital are closely related to the dominant view (doxa). “We perform automatic actions which are embedded in our culture. A human is part of the culture, but the culture is also part of the human” (E1). In some societies, culture can be supporting, in others – limiting. Changes require time, which is also indicated in Bourdiean analysis. According to E4, currently, sustainable consumption is widely acknowledged. It is no longer a novel idea that brings cultural capital for its practitioners. If overall, a society supports sustainable consumption, it can become the norm (E5). However, in some cases, very pro-ecological societies still have unsustainable customs. For example, Japanese and some Nordic nations still support whale hunting despite being environmentally conscious societies (E1).

An interesting dissonance appears as well when companies come from much more sustainable countries than the ones where they operate. The consumers can underestimate it, follow the price only or be suspicious towards the company’s actions (the respondent mentions homo sovieticus) (E2). This statement also refers to the ability to distinguish products and the cultural capital.

In some cases, business educates consumers. Various corporate social responsibility actions show good examples and pinpoint negative behaviours, which are further recognized and boycotted by consumers (E2). Businesses also actively participate in the promotion of green consumption (E4).

Following models

As noted above, sustainable consumption is often portrayed as a matter of fashion. The consumer has several types of role models. In media campaigns, politicians and celebrities are used to promote the consumption of sustainable products (E1 and E2). Sometimes, social media users or bloggers become role models, for example, people practising minimalism (E2). Family members can serve as examples (E1 and E2). The consumer often sees what their friends and peers are doing and decides to follow (E2 and E5). An example can be adopting animals from shelters rather than purchasing certified breeds (E2). Finally, a state can be a role model and a leader with special state capital and instruments. Companies can also lead by example, especially as their activities stretch beyond country borders (E4).

In relation to fashion, sustainability becomes a type of distinctive lifestyle. In some countries, it is still an elite and niche subculture. Through cultural inclusion, consumers gain a sense of belonging and being fashionable at the same time (E1).

Sustainable consumption can be treated as a cover relating to the social capital. Some agents want to distinguish themselves by buying products from a certain brand and only later add ideology to their behaviour (E1). According to E3, what matters is the experience. Even if products have a similar impact on the planet when they are served in a special way and cost more, consumers value them higher. Pleasure and beauty are more likely to be bought. Consumers are thus motivated by simple intrinsic pleasure and becoming more sophisticated rather than environmental concerns (E3). Finally, due to the global shift and trickle-down effect, sustainable products or services are currently positioned as luxurious, that is, they have a higher perceived value than unsustainable practices.

As described above, sustainable consumption consists of multiple dimensions, and they are all interlinked. The theme, which appears most often in the interviews, was differentiated understanding of sustainable products and services (24 codes). In the case study of ecotourism, it is visible in various types of activities practised by analysed groups. The second is following models (15 codes) with a strong theme of following fashions. Taking potentially irrational decisions beyond economic calculations is the third most common concept (11 codes), strongly pointing to other values such as society and environment protection being taken into consideration.

These four themes can be observed in the case of ecotourism described in the next section.

Case study of ecotourism

In this section, we apply the proposed framework to the case of ecotourism, a subset of sustainable tourism (Weaver, Citation2001). Ecotourism becomes a field (an environment) towards which agents relate. The agents, in this case, are clients choosing tourism services. Their cultural capital relates to their educational background and family. The social capital can be understood as their friends and networks. The economic capital relates to financial resources. The agents are also in possession of environmental capital, awareness about interconnections between humans and nature (Diamantis, Citation1998). The doxa of the agents in this field is their shared view of protecting nature while engaging in tourism activities.

Ecotourists are characterised as active with high interest in nature (Gil Álvarez, Citation2012; Gao et al., Citation2016), interested in personal development and culture of the place (Carvache-Franco et al., Citation2019), and with a high willingness to pay for a nature experience (Lu et al., Citation2016; Nickerson et al., Citation2016). In the following sections, we analyse how four assumptions could be exemplified in relation to ecotourism.

Firstly, engaging in ecotourism requires motivations going beyond economic calculation. Ecotourism requires cultural capital shaping the sustainable habitus. Additionally, taking part in ecotourism activities often requires certain financial investments, specifically in more organized forms such as ecotours provided by tour operators or at least purchasing special equipment. Some forms of ecotourism, such as mountain hiking, remain more affordable than leisure activities characteristic for the upper class. However, ecotourism always requires investment from the cultural capital because agents must at least find a natural place they want to explore and either does so with the help of tour operators or on their own. At the same time, affordable types of ecotourism are increasingly popular among people with lower incomes. Bourdieu himself mentions three social groups that engage in ecotourism being the new bourgeoisie, the nouvelle petite bourgeoisie, and the professors. Despite differences in motivation, all three groups possess a relatively high amount of cultural capital that allows them to use ecotourism as distinction.

Second, ecotourism gives space for differentiated understanding. Ecotourism may be perceived as a symbolic good. Going on nature-related trips, or rather, being able to report it, helps in building certain symbolic capital that can be further supported by other artefacts of a sustainable lifestyle. For the middle class, ecotourism is the way to show their cultural capital and demonstrate that the environment is worth more to them than money. The value of nature-based tourism lies, therefore, not in learning and understanding the environmental issue they face, but rather collecting experiences to later talk about (Jamal et al., Citation2003, p. 151). It is also expressed in the culture of naturalness, purity and authenticity through the purchase of accessories such as trekking jackets, authentic Shetland sweaters and others. Other groups of customers demonstrate an interest in ecotourism activities, such as hiking and trekking, which require some cultural capital but less economic measures.

Third, the education and environmental capital lie at the core of ecotourism. One of the first definitions of ecotourism by Ceballos-Lascurain: “Traveling to relatively undisturbed or uncontaminated natural areas with a specific objective of studying, admiring, and enjoying the scenery and its wild plants and animals, as well as any existing cultural manifestations (both past and present) found in these areas” includes a clear reference to education and awareness (Ceballos-Lascurain, Citation1987, p. 14). Also ecotourism, understood as “responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people and involves interpretation and education” (TIES, Citation2015), assumes non-extractive use of resources, creation of environmental conscience and ethics related to nature. The introduction of ecotourism patterns would depend then on inheriting sustainable travelling patterns. As we learn from Bourdieu’s framework, much of this happens during the process of education. He suggests that business schools put more emphasis on sports, whereas art and humanities focus more on the cultural experience. Both can accommodate elements of ecotourism such as canoeing, horse-riding, trekking, or cultural experiences with indigenous communities or local artists using materials from the region.

Fourth, one of the motivations for ecotourism includes following trends. Education enables influencing higher classes, and consumption patterns are often followed by middle and lower classes (trickle-down effect). However, the latter also develop other forms of ecotourism, for example, walks in the local forest or camping, which enable connection to nature and the following of latest trends but are also affordable and do not require major investments. From the perspective of social capital, the distinction through ecotourism requires an audience that can recognize the difference, see it and grasp it. The same experience may be distinctive and common at the same time when perceived in a relative way as it belongs to a certain social reality. The same exotic journey may be perceived as commonplace by fellow backpackers.

Discussion

In this section, we first discuss our results. Further, we compare them with the findings from other studies. Third, we address the limitations of this study. We finish with recommendations for further research.

Our findings show that sustainable consumption is connected to various types of capital. The four patterns derived from the interviews and consistent with the theoretical assumptions of Bourdieu indicate a leading role of cultural capital followed by economic and social capital to a lesser extent (see ).

Table 1. Relation between four behaviour patterns and various types of capital.

The interview analysis suggests that a high level of economic capital is not essential. Even agents with a low amount of economic capital can make sustainable purchases and enjoy ecotourism. Finally, social capital appears supporting but less necessary. Peer pressure encourages the actual sustainable consumption, not only declarations, but agents can also consume sustainably to differentiate themselves from the surroundings and become more sophisticated.

These theoretical discussions remain relatively abstract; therefore, we applied them to the case of ecotourism. Motives associated with cultural capital are mentioned by other researchers, e.g. (Kerstetter et al., Citation2004; Lee et al., Citation2014). The cultural capital also includes environmental capital-related motives, such as in the study of (Cordente-Rodríguez et al., Citation2014). Other studies such as Carvache-Franco et al. (Citation2019) confirm the role of cultural capital understood as self-development but also social capital understood as developing relationships with the new family and meeting new people (Carvache-Franco et al., Citation2019; McGehee & Kim, Citation2004). On the other hand, other studies also suggest motives such as breaking from daily routine (Broad & Jenkins, Citation2008).

In the broader context, sustainable consumption is widely accepted and chosen by agents with various amounts of economic capital. The bare minimum of cultural capital (distinction) is often supplied by the educational system and confirmed by role models. Therefore, at present, the Bourdieu’s framework can serve as a tool of analysis of sustainable consumption beyond the middle and upper classes. However, Bourdieu’s work is multi-dimensional and can be variously interpreted. For example, Jesper Ole Jensen characterized consumption in terms of habitus with a strong cultural component, but not in terms of habit, routine, convention, as did Wilhite (Jensen, Citation2008, p. 355; Wilhite et al., Citation1996). Bourdieu understands consumption as related to issues of status, symbolism and social distinction, while Wilhite sees it as a matter of reproduction of habits, routine or convention (Jensen, Citation2008, p. 355). Some other authors put more emphasis on social capital. Looking further at a community’s motivation and impact, Derrick Purdue et al.’s research in the UK shows that environmental events, programmes, and networks encourage ecological and cultural innovation of everyday life, combining global and local perspective (Citation1997). Local social relations and identities are altered in reflexive ways that utilize, criticize and contribute to globalization, which can be self-contradicting, but at the same time develop new senses of locality and community (Purdue et al., Citation1997). Dave Horton (Citation2003) focuses on symbolic and social capital, as well as the habitus of the leaders. He stresses the role of the daily routines of environmental activists (often extreme cases of green consumers) as individuals who have an effect not only on the environment but also on their social networks.

Finally, the methods used in this study involve certain limitations. As our main aim was the development of a theoretical framework, we employed a limited number of expert interviews. Also, the interviews conducted via Skype/phone or in person were much more elaborate than those conducted by e-mail due to the expert availability. Further interviews with a larger sample of ecotourists could shed more light on the analysed case study and application of this framework.

The case of ecotourism could be further specified by relating to a concrete site and its visitors. Additionally, a natural progression of this work would be a quantitative analysis testing the influence of different types of capital on sustainable consumer choices.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to examine behaviour patterns related to sustainable consumption based on concepts derived Pierre’s Bourdieu framework. Specifically, we looked at how different types of capital influence consumer choices related to sustainable consumption and its specific example, ecotourism. We examined it through content analysis, semi-structured expert interviews, and application to a case study of ecotourism.

Our key finding is that although all types of capital influence the sustainable habitus and behaviour of ecotourists, the cultural capital represented by education, knowledge and awareness play the most important role. Most of the interviewees agree that it influences sustainable consumption to a large extent, although it is not the only factor. This is confirmed by the four overarching themes appearing both in the interviews and in the social theory of Pierre Bourdieu. These were taking into account other values such as thinking beyond egoistic economic calculation, diverse understanding of sustainable products and services, the role of education, and following role models and fashion. Accordingly, we found out that sustainable consumption is present in all social classes, although reasons for it differ considerably from conscious nature protection to distinction among peers.

Ecotourism is an example of sustainable consumption closely related to economic and cultural capital constituting the so-called habitus. Firstly, taking part in ecotourism activities often requires certain financial investments, specifically in more organized forms provided by tour operators or at least purchasing special equipment. At the same time, it remains more affordable than other leisure activities characteristic for the upper classes. Secondly, ecotourism often requires investment from the cultural capital because actors must at least find a natural place they want to explore. Simultaneously, affordable types of ecotourism are increasingly popular among people with lower incomes and lower cultural capital that may be linked to fashion created by higher classes.

The findings of this study provide a better understanding of factors influencing sustainable consumption, in particular in the form of ecotourism. They can be further used by researchers wanting to explore this phenomenon, by policymakers to support their decisions related to incentives, and by companies wishing to better respond to sustainable consumers’ needs and to become role models.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Warsaw School of Economics. The author want to extend his/her thanks to Bas Bruning and Sandhiya Goolaup for reviewing the manuscript in an early phase.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste (Reprint1984 ed.). Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1998). Practical reason. On the theory of action. Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P., & Richardson, J. G. (1986). Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. The Forms of Capital, 241, 258.

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. University of Chicago Press.

- Breiby, M. A., Duedahl, E., Øian, H., & Ericsson, B. (2020). Exploring sustainable experiences in tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(4), 335–351. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1748706

- Broad, S., & Jenkins, J. (2008). Gibbons in their midst? Conservation volunteers’ motivations at the Gibbon rehabilitation project, phuket, Thailand. Journeys of Discovery in Volunteer Tourism: International Case Study Perspectives, 72–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845933807.0072

- Carvache-Franco, M., Segarra-Oña, M., & Carrascosa López, C. (2019). Motivations analysis in ecotourism through an empirical application: Segmentation, characteristics and motivations of the consumer. Geo Journal of Tourism and Geosites, 24(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.24106-343

- Ceballos-Lascurain, H. (1987). The future of ecotourism. Mexico Journal, 13–14.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications.

- Christopoulos, D. (2009, February). Peer Esteem Snowballing: A methodology for expert surveys. In Eurostat conference for new techniques and technologies for statistics (pp. 171–179).

- Cordente-Rodríguez, M., Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.-A., & Villanueva-Álvaro, J.-J. (2014). Sustainability of nature: The power of the type of visitors. Environmental Engineering & Management Journal (EEMJ), 13(10), 2437–2447.

- Diamantis, D. (1998). Ecotourism: Characteristics and involvement patterns of its consumers in the United Kingdom. [PhD, Bournemouth University]. http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/395/

- Doran, R., Hanss, D., & Larsen, S. (2017). Intentions to make sustainable tourism choices: Do value orientations, time perspective, and efficacy beliefs explain individual differences? Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 17(3), 223–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2016.1179129

- Elliott, R. (2013). The taste for Green: The possibilities and dynamics of status differentiation through “Green” consumption. Poetics, 41(3), 294–322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2013.03.003

- Fien, J. (1993). Education for the environment: Critical curriculum theorising and environmental education. Deakin University.

- Fredman, P., & Margaryan, L. (2021). 20 years of Nordic nature-based tourism research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1823247

- Gao, Y. L., Mattila, A. S., & Lee, S. (2016). A meta-analysis of behavioral intentions for environment-friendly initiatives in hospitality research. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 54, 107–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.01.010

- Gil Álvarez, E. (2012). Vacaciones en la naturaleza: Reflexiones sobre el origen, teoría y práctica del ecoturismo. Polígonos. Revista de Geografía, 14(14), 17–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18002/pol.v0i14.488

- Goolaup, S., & Mossberg, L. (2017). Exploring the concept of extraordinary related to food tourists’ nature-based experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 17(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2016.1218150

- Hall, C. M., & Saarinen, J. (2021). 20 years of Nordic climate change crisis and tourism research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1823248

- Horton, D. (2003). Green distinctions: The performance of identity among environmental activists. The Sociological Review, 51(2_suppl), 63–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2004.00451.x

- Ianioglo, A., & Rissanen, M. (2020). Global trends and tourism development in peripheral areas. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(5), 520–539. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1848620

- IISD. (1994). Oslo Roundtable on Sustainable Production and Consumption. http://enb.iisd.org/consume/oslo000.html

- Jackson, T. (2005). Live better by consuming less? Is there a “double dividend” in sustainable consumption? Journal of Industrial Ecology, 9(1–2), 19–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/1088198054084734

- Jamal, T., Everett, J., & Dann, G. M. (2003). Ecological rationalization and performative resistance in natural area destinations. Tourist Studies, 3(2), 143–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797603041630

- Jensen, J. O. (2008). Measuring consumption in households: Interpretations and strategies. Ecological Economics, 68(1–2), 353–361. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.03.016

- Karol, J., & Gale, T. (2004). What is ‘environmental capital’? Bourdieu’s social theory and sustainability.

- Kerstetter, D. L., Hou, J.-S., & Lin, C.-H. (2004). Profiling Taiwanese ecotourists using a behavioral approach. Tourism Management, 25(4), 491–498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00119-5

- Lee, S., Lee, S., & Lee, G. (2014). Ecotourists’ motivation and revisit intention: A case study of restored ecological parks in South Korea. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 19(11), 1327–1344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2013.852117

- Lissner, I., & Mayer, M. (2020). Tourists’ willingness to pay forBlue flag'snew ecolabel for sustainable boating: The case of whale-watching in iceland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(4), 352–375. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1779806

- Lu, A. C. C., Gursoy, D., & Del Chiappa, G. (2016). The influence of materialism on ecotourism attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Travel Research, 55(2), 176–189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514541005

- McGehee, N. G., & Kim, K. (2004). Motivation for agri-tourism entrepreneurship. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 161–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504268245

- Nickerson, N. P., Jorgenson, J., & Boley, B. B. (2016). Are sustainable tourists a higher spending market? Tourism Management, 54, 170–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.11.009

- Purdue, D., Dürrschmidt, J., Jowers, P., & O'Doherty, R. (1997). DIY culture and extended milieux: LETS, veggie boxes and festivals. The Sociological Review, 45(4), 645–667. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.00081

- Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE Publications Limited.

- Sandve, A., & Øgaard, T. (2013). Understanding corporate social responsibility decisions: Testing a modified version of the theory of trying. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 13(3), 242–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2013.818188

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques (p. 270). Sage Publications, Inc.

- TIES. (2015, January 1). TIES Announces Ecotourism Principles Revision | The International Ecotourism Society. https://www.ecotourism.org/news/ties-announces-ecotourism-principles-revision

- UNWTO. (2021). Tourism in the 2030 Agenda | UNWTO. https://www.unwto.org/tourism-in-2030-agenda

- Weaver, D. B. (2001). The encyclopedia of ecotourism. Cabi.

- Wilhite, H., Nakagami, H., & Murakoshi, C. (1996). The dynamics of changing Japanese energy consumption patterns and their implications for sustainable consumption. Proceedings of the 1996 American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy Summer Study in Buildings, 8, 231–238. https://www.aceee.org/files/proceedings/1996/data/papers/SS96_Panel8_Paper26.pdf