Abstract

The 2015 refugee crisis has sparked heated polarized debates throughout the globe. Yet, to date, we know too little about the discursive framing of the refugee crisis by various actors on online media, and the effect of right-wing populist messages on stereotypical images of refugees. The extensive qualitative content analysis reported in this paper (Study 1, N = 1,784) shows that the framing of populist politicians and citizens overlap in the problem definitions. However, citizens attribute more responsibility to refugees themselves and perceive that the native people are relatively deprived. Traditional news media are more divided. Overall, tabloid media define refugees as a problem, and broadsheet media frame them as victim. The second experimental study (N = 277) demonstrates that messages that blame immigrants for increasing crime rates activate negative stereotypical images of migrants among people with stronger perceptions of relative deprivation. These messages have the opposite effect among citizens with weaker perceptions of relative deprivation. These findings provide important insights into the political consequences of anti-immigration framing. Online media discourse is generally one-sided, and exposure to anti-immigration messages may polarize the electorate in opposing camps.

The 2015 European refugee crisis has been surrounded by fierce debates in media, politics and society. Issues of national safety, identity and economic insecurity have been raised by politicians, journalists and citizens throughout the globe. Right-wing populist politicians used the refugee debate to cultivate a pervasive societal divide between the ordinary people and the corrupt elites accused of allowing migrants to profit. In the US, for example, Trump repeatedly referred to the European refugee crisis to argue that native American citizens should be afraid of the influx of foreign elements that pose a threat on their security. But how are the media providing a platform for right-wing populist discourse, and what are the political consequences of media frames that blame refugees for national issues?

The spread of right-wing populist discourse in the media may activate and prime polarized divides in society (e.g., Müller et al., Citation2017). Social media in particular offer an important platform for the dissemination of populist discourse (e.g., Engesser, Ernst, Esser, & Büchel, Citation2017; Van Kessel & Castelein, Citation2006; Waisbord & Amado, Citation2017). Importantly, the affordances of social network sites allow both ordinary citizens and politicians to speak directly to the electorate. Such direct communication circumvents traditional journalistic routines, such as fact-checking or the search for balance and diversity. These developments may give rise to a hostile, one-sided online discourse, in which migrants are seen as a severe threat to the well-being of the ordinary people.

To better understand how the European refugee crisis was framed in online media, and to provide insights into the effects of right-wing populist discourse, this paper employs a mixed-methods design. First of all, a qualitative content analysis of Dutch online news media, populist politicians’ Twitter accounts and citizens’ Facebook communities (N = 1,784) is employed to provide insights into the discourse used to portray refugees entering Europe. In the next step, the effects of messages that blame refugees are investigated with an online experiment (N = 277).

This paper aims to make at least two important contributions. First of all, moving beyond mere numbers, the qualitative content analysis provides insights into the ways in which refugees are portrayed as a threat to the native people. The content analysis further highlights the overlap and differences in the discursive construction of refugees as an out-group by politicians, ordinary citizens and the media. Second, the central content features of the discourse surrounding the refugee crisis are experimentally manipulated to investigate how citizens are influenced by messages that shift blame to refugees – to what extent do people support the out-group constructions communicated on social media? Taken together, this research contributes to our understanding of the impact of framing refugees as a threat to “the people” in right-wing populist discourse.

Anti-immigration Discourse: Populism and the Radical-right

The anti-immigration discourse that gained prominence in the recent European refugee crisis can conceptually be linked to populism and radical right-wing discourse. Populism essentially revolves around the emphasis on a pervasive divide in society: the good, ordinary people are juxtaposed to the evil, corrupt elites (e.g., Mudde, Citation2004; Taggart, Citation2000). The central divide between ordinary citizens and culpable elites is typically regarded as the thin-ideological core of populism (e.g., Mudde, Citation2004). This conceptualization presupposes that populism is not an ideology by itself, and that it can be supplemented by fuller-fledged ideologies (e.g., Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Citation2017). At its essence, populism’s thin ideology cultivates a binary view on politics and society. This divide has two components: (1) the ordinary people have a monolithic will that is not represented in politics and (2) the elites, most notably the national political elites, are responsible for not representing “their” people. The elites are seen as corrupt and self-interested, and look after their own interests instead of their electorate (e.g., Canovan, Citation1999; Mudde, Citation2004). But what host ideologies may supplement this core opposition?

One of the most central frames used to depict the European refugee crisis is nativism – emphasizing that the ordinary people as an in-group are threatened by immigrants that pose a threat on the welfare, culture and economic security of the native people (e.g., Duckitt & Sibley, Citation2010). Nativism is oftentimes conflated with (right-wing) populism (e.g., De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Citation2017). The crucial difference between the two concepts is the portrayal of the in-group (De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Citation2017). Populism refers to an in-group of ordinary citizens, who are perceived as being homogenous regarding their will (e.g., Taggart, Citation2000). This in-group should be empowered, and populism consequentially refers to the sovereignty of the people’s will. Nativism, however, refers to an in-group of people that identify with the nation state (e.g., Sutherland, Citation2005). Nativist citizens feel attached to their nation, and perceive immigrants as a threat to the well-being of their nation state, be it for cultural or economic reasons. Populism and nativism can thus both be exclusionist, and may both describe the discourse surrounding the European refugee crisis.

The media discourse surrounding the European refugee crisis is multifaceted, and may contain references to both populist (i.e. the elites allow too many foreigners to enter) and nativist sentiments (i.e. refugees threaten our national identity). For this reason, this research takes both concepts into account to better understand the media’s framing of the refugee crisis, as well as its effects on public opinion. In that sense, we focus on right-wing populist discourse – in which the central divide between the ordinary people and the corrupt elites is supplemented by nativist and anti-immigration sentiments. But what is the particular role of the media in the public’s perception of the refugee crisis?

THE ROLE OF ONLINE MEDIA IN SHAPING ANTI-IMMIGRATION DISCOURSE

The media play an important role in the framing of immigration (e.g., Dixon & Williams, Citation2015; Kim, Carvalho, Davis, & Mullins, Citation2011) and populism (e.g., Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck, & de Vreese, Citation2017; Schmuck & Matthes, Citation2017). Experimental research demonstrates that exposure to messages that negatively portray immigrants or refugees can activate negative stereotypes towards these groups (e.g., Dixon & Williams, Citation2015; Schmuck & Matthes, Citation2017). Because people learn about issues and societal groups via the media channels they are exposed to, public opinion surrounding the refugee crisis is for an important part informed by images and frames distributed via the media.

As the concept of framing has been surrounded with disagreement and scholarly debates, it is important to provide a specific conceptualization of framing (e.g., Cacciatore, Scheufele, & Iyengar, Citation2016). In this paper, we look at emphasis framing (e.g., Entman, Citation1993) – which is in line with Gamson and Modigliani’s (Citation1989) understanding of a frame as a “central organizing idea or story line that provides meaning to an unfolding strip of events” (p. 143). This understanding of framing entails that alternative frames do not present logically equivalent information, but rather different organizing ideas to emphasize different aspects of socio-political reality. Emphasis frames may consist of different frame-elements that can cluster together in different ways (Matthes & Kohring, Citation2008). More specifically, different combinations of problem definitions, causal interpretations, moral evaluations and/or treatment recommendations can co-occur in systematic patterns. These clusters can be defined as frames (Entman, Citation1993; Matthes & Kohring, Citation2008).

Using this conceptualization of emphasis framing (e.g., Cacciatore et al., Citation2016), a growing number of empirical studies investigated how illegal immigration is portrayed in the media (e.g., Kim et al., Citation2011). Relying on an emphasis framing approach, Kim et al. investigate the problem definitions, causes, and solutions offered in mainstream media coverage. Frequently mentioned causes are economic hardships in immigrants’ own country, failing border controls and failing immigration policies. News on immigration is frequently linked to crime, which may prime negative stereotypes of immigrants as criminals. Earlier studies on news framing surrounding immigration found that newspapers depicted immigrants in a negative, stereotypical way – referring to them as a greedy and lazy out-group that is threatening the nation’s social stability (Coutin & Chock, Citation1997).

In this paper, we shift our focus to online media – a research field that has recently received ample attention in studies on populist communication (e.g., Engesser et al., Citation2017; Waisbord & Amado, Citation2017). Although these studies mainly focused on the communication strategies of politicians, they demonstrate that social media empower communicators to spread a hostile, negative and conflict-centered discourse via their own ungated media channels. This study identifies three actors that are central in the online media coverage of immigration: (1) news media, (2) ordinary citizens and (3) populist politicians.

Using a qualitative approach, we specifically aim to identify the discursive frames used to refer to the problem, causes, moral evaluation and treatment of immigration in a Western European setting associated with the 2015 refugee crisis: the Netherlands. Here, we understand emphasis frames as patterns or clusters of frame-elements that can co-occur in different ways to emphasize different aspects of reality (Entman, Citation1993). Taking this approach, frames used to interpret the refugee crisis can be identified in a more valid and reliable way (Matthes & Kohring, Citation2008). We raise the following research question: How are the discursive frame-elements of the problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation and treatment recommendation constructed in online media surrounding the 2015 refugee crisis in the Netherlands? (RQ1). These frame-elements can be reconstructed into meaningful clusters that provide alternative constructions of the reality surrounding the refugee crisis.

In the Netherlands, right-wing populism is salient in politics and public opinion (Aalberg et al., Citation2017). The right-wing populist politician Geert Wilders and ordinary citizens may both use social media to disseminate anti-immigration frames. Wilders’ discourse may contain references to the “corrupt” elites that allow too many foreigners to enter (Van Kessel & Castelein, Citation2006). Ordinary citizens may be more likely to associate immigration with threats to their safety and identity. News media are expected to engage in more neutral coverage – promoting a more nuanced and relativized image of the problem, causes and treatments of immigration. Hence, news media that report on the refugee crisis via online channels are linked to journalistic routines expected to seek for the truth, relying on a balanced coverage of the issue at hand. The second research question aims to provide insights in the frame-alignment of these different actors: To what extent do the discursive frames of populist politicians, ordinary citizens and news media overlap in covering the 2015 refugee crisis? (RQ2).

The Effects of Right-wing Populist Discourse on Anti-immigration Sentiments

A growing body of research has investigated the media effects of right-wing populist or anti-immigration framing on political perceptions (e.g., Dixon, Citation2008; Hameleers, Bos, & de Vreese, Citation2017; Matthes & Schmuck, Citation2017). Matthes and Schmuck (Citation2017) demonstrate that negative portrayals of immigrants in populist political communication can activate negative implicit and explicit stereotypical images of this group. Other (mostly U.S. based) experimental research shows that media coverage that negatively portrays immigrants can activate negative stereotypes towards this constructed out-group (e.g., Dixon, Citation2008).

The mechanism by which anti-immigration messages may affect political attitudes can be understood as negative stereotyping (e.g., Dixon, Citation2008). More specifically, messages that depict immigrants as a threat to the native people may prime congruent schemata among receivers. This means that, when people are exposed to messages that emphasize that refugees are culpable for the people’s problems, similar mental representations of refugees may be activated. After repeated exposure to messages that assign blame to the culpable refugees, negative mental images or schema of this group may become highly accessible among receivers (Dixon, Citation2008). Negative stereotyping ties in with the psychological processes of priming and trait activation (e.g., Müller et al., Citation2017). Exposure to negatively biased immigration news may not change people’s attitudes towards immigrants, but rather activates stereotypes that already exist.

Social identity theory, and social identity framing more specifically, provides a conceptual framework for understanding the effects of anti-refugees news on congruent anti-immigration attitudes. Specifically, messages that cultivate a salient threat to the in-groups whilst introducing causally responsible others are found to be persuasive (e.g., Gamson, Citation1992; Polletta & Jasper, Citation2001). When a salient threat to the in-group is cultivated through right-wing populist anti-immigration messages, people should become motivated to avert the threat. Moreover, the emphasis on culpable others can activate feelings of injustice – and people’s desire to restore the severe power discrepancy between “us” and “them” (e.g., Gamson, Citation1992).

Anti-immigration frames tie in with the premises of persuasive social identity frames as they a) cultivate a severe threat to the in-group and b) emphasize that elites and/or refugees are responsible for this threat. Anti-refugee messages should therefore mobilize the in-group to engage, priming their negative associations towards immigrants as an out-group. We therefore hypothesize that messages that cultivate the native people’s identity and blame refugees for national issues activate negative stereotypes towards immigrants (H1).

THE PERCEPTUAL SCREEN OF PERCEIVED THREATS

Ceteris paribus, we expect that right-wing populist messages prime negative associations towards immigrants. However, the extent to which these mental schemata are primed may depend on the availability and salience of congruent prior attitudes. In other words, we should not expect that exposure to a single anti-immigration message should cultivate negative stereotypes among all citizens. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that people with incongruent prior attitudes may reject or counter-argue right-wing populist communication (e.g., Hameleers & Schmuck, Citation2017). This indicates that, depending on the fit with people’s attitudinal biases, right-wing anti-immigration messages may be accepted or counter-argued by receivers. But what attitudinal lenses may drive persuasion and resistance?

Kriesi et al. (Citation2006) refer to populist voters as the “losers of modernization” – being part of a societal group that is left behind as a consequence of modernization processes they cannot keep up with. Our understanding of the populist electorate is more perceptual, and builds further on Elchardus & Spruyt’s (Citation2016) understanding of perceived relative deprivation as predictor of populist vote choice. Relative deprivation taps into the experience of a discrepancy between the in-group and other groups that are relatively better off (e.g., Elchardus & Spruyt, Citation2016).

Relative deprivation can be connected to the framework of social identity theory to explain the persuasiveness of identity-framed anti-immigration messages. People with stronger perceptions of relative deprivation experience that the distribution of the nation’s resources is unjust: the in-group of the native people is left behind, and the others (i.e. refugees) are allowed to profit from the people’s resources. People that experience to have been neglected, and believe that refugees are allowed to profit, may be appealed to anti-refugee messages that highlight a discrepancy between the ordinary people and the profiting refugees. The perceived power and status discrepancy between the in-group and the others may thus augment the persuasiveness of anti-immigration messages. This ties in with the mechanism of motivated reasoning (Festinger, Citation1957; Taber & Lodge, Citation2006). People at higher levels of perceived deprivation should perceive the anti-immigrant cues in right-wing populist communication as congruent with their pre-existing beliefs. People who do not feel deprived, in contrast, should perceive the message as counter-attitudinal. Against this backdrop, we hypothesize that right-wing populist communication is most persuasive for people with stronger perceptions of relative deprivation (H2a) and is resisted or counter-argued by people with weaker perceptions of perceived relative deprivation (H2b).

Research on polarization and motivated reasoning in the U.S. demonstrates that partisanship forms an important basis of social identity, which consequentially drives the selection and processioning of media content (Iyengar & Hahn, Citation2009). Likewise, studies on the effects of responsibility attributions reveal that partisan identification forms an important perceptual screen by which people selectively accept or reject blame attributions (Hobolt & Tilley, Citation2014). Extrapolated to the effects of right-wing populist messages, it can be expected that people’s attachment to national identity and distance to immigrants has an impact on the message’s acceptance. Specifically, if people feel close to the threatened in-group of the native ordinary people, messages that cultivate an in-group threat should be perceived as more personally relevant. We therefore hypothesize that right-wing populist communication has the strongest effects on people that identify strongly with the nation (H3).

METHOD STUDY 1: A QUALITATIVE CONTENT ANALYSIS OF THE REFUGEE CRISIS

Before investigating the effects of right-wing populist discourse on negative stereotypical portrayals of refugees (Study 2), the first study aims to understand the discursive frames used to frame the 2015 refugee crisis in online Dutch media.

Sampling and Data Collection

Data were collected on three levels: (1) Tweets distributed via the official account of Geert Wilders (N = 1,489); (2) online news distributed via the official Facebook accounts of one Dutch mainstream (de Volkskrant) and one tabloid media outlet (de Telegraaf) (N = 31) and (3) posts of three online publically accessible Facebook communities of ordinary citizens that covered the refugee debate (N = 264). The data collection and analysis plans were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB).

The selection of news outlets was based on the principle of maximum variation (e.g., Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). Specifically, tabloid outlets are more likely to engage in a negative and populist coverage of the refugee debate compared to broadsheet outlets (e.g., Krämer, Citation2014). Three Facebook communities were sampled. One community’s aim was to mobilize native citizens to protest against the influx of refugees. Another community revolved around the celebration of the native people’s in-group. The final community was occupied by followers of the right-wing populist politician Wilders. All communities thus connected to the refugee crisis in different ways, displaying a varied discourse on the issue at hand. Interestingly, one of the three communities was targeted at an international audience of Wilders supporters, who shared (news) articles and interpretations in English. The posts dealt with the issue of immigration on a trans-national, European level. A Python script was used to download social media data – which were all stored as raw textual data to be analyzed manually in the next step.

The three samples all covered the same period: the final three months of 2015 and the first six months of 2016. This period was chosen as the refugee crisis was picked up in the media in 2015, and continued to be salient in public opinion and political discourse in 2016. The principles of theoretical saturation were used as inclusion criteria (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). Specifically, in the cyclic-iterative process of data collection and analysis, the nine-months period was compared to the coverage in earlier months of 2015 and later months of 2016. As these different months did not yield novel insights into the coverage of refugees, the variety captured in the sampled period should reflect the discursive framing of the refugee crisis.

The same search string was used to select items in all three samples: Refugee* OR immigration OR immigrant* OR asylum seekers OR migrant* OR migration. All results were judged if they covered the refugee crisis. Items were for example excluded if they referred to immigration (policies) more generally, or different settings and crises. After a close reading of the full samples, 31.8% of all posts was excluded because the content was not directly related to the scope of this research.

Data Analysis

The discourse analysis was structured by the coding steps detailed in the grounded theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). First of all, all posts and articles were read thoroughly. Complete line-by-line coding was only conducted on relevant posts (containing references to the refugee crisis). The full sample was thus coded selectively: 43.6% of all sampled Tweets, all news articles, and 63.6% of the Facebook posts was fully coded according to the steps of the Grounded Theory approach.

First, the data were analyzed using open coding. Guided by the frame-elements (problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation and treatment recommendation) as sensitizing concepts, the samples were coded on the foregrounded problems, causes, solutions and moral issues surrounding the refugee crisis. In a next step of focused coding, unique open codes were merged and raised to a higher level of abstraction. In other words, categories of discursive frame-elements were constructed. Finally, during axial coding, theoretically meaningful relationships between categories were established (clusters of frame-elements were identified).

Quality Checks

Although the aims and scope of qualitative data may not be suited for quality checks used in quantitative research that aims for internal and external validity, qualitative research may still be subject to quality checks that suit the nature of the data. Specifically, peer debriefing and member checks can be used to judge the emerging themes of the qualitative content analysis. In line with this, the researcher has invited two members of two of the sampled Facebook communities to respond to the emerging themes. They agreed on the main construction of threats. However, they did not perceive their language as hostile, but accurate (which may be a finding by itself).

As part of peer debriefing, an equivalent procedure to assess inter-coder reliability for qualitative text analysis (e.g., Braun & Clarke, Citation2013), an independent researcher unfamiliar with the data independently coded four items of every sample using the same sensitizing concepts (the four-frame elements). This round was completed before coding the full sample. Differences between coders were minimal, and extensively discussed. The main differences revolved around the moral evaluations and treatment recommendation. After coding the full sample, two researchers independently completed open, selective and axial coding on ten Tweets, Facebook posts and articles. The resulting frame elements were compared, which means that all emerging codes resulting from the three steps of data reduction were discussed. The main interpretations differed in two cases. More specifically, in both cases, one researcher assigned the treatment of the refugee crisis to the government, whereas the other researcher assigned it to the populist political party.

Results Study 1: Ways of Cultivating Threats and Excluding Others

Wilders’ Construction of the Refugee Crisis: Cultivating Threats and Blaming the Elites

The politician Geert Wilders defined the refugee crisis as a severe threat to the ordinary native people. The influx of migrants was connected to a growing threat of terrorist attacks: “Islamic countries have declared a war on us. And this will get worse in the nearby future”. Refugees were, however, also connected to violent crime rates, allegedly posing a threat to vulnerable native people. According to Wilders, women are at risk of being raped by savage refugees. In addition, the erosion of the native people’s norms and values was cultivated by Wilders, emphasizing that refugees pose a severe threat on the identity of the native people: “The Dutch population will be colonized. It is already being replaced by foreigners with norms and values that do not belong here”.

This problem definition was connected to blame attribution to the elites. Specifically, Wilders accused both the European Union and the national government of allowing criminals to enter the country: “Islamic terrorists allowed to enter via our airport. Facilitated by the open borders of the government”. Safety threats were also attributed to EU leaders: “Unresponsive EU politicians are to blame for terror attacks as they keep on neglecting the fact that Islam is the cause of terror”. Likewise, identitarian threats were attributed to the elites. The central theme that can be identified here is “put your own people first”: the elites should be responsive to the needs of the deprived ordinary people, and should not protect others that are threatening the purity of the people.

Nativist sentiments highlighted in Wilders’ discourse emphasized the threat of Islamization, and the perception that the native population is being replaced by foreigners that are not morally entitled to the resources of the native people. The moral evaluation emphasized by Wilders revolved around the perception of an unjust distribution of economic and cultural capital – which ties in with injustice framing in social identity theory (Gamson, Citation1992). Wilders connected this sense of injustice to a treatment recommendation: the country should “wake up” and acknowledge the threats before it is too late. The only solution is to close the borders and exclude refugees from the native people’s country. To do so, the “corrupt” elites need to be replaced by a government of the people.

Focusing on the co-occurrence of frame-elements in Wilders’ discourse, two patterns can be distinguished: (1) The emphasis on a severe threat of the Islam, which is the greatest enemy of the ordinary Dutch people (the Islamization frame) and (2) the emphasis on the elite’s failure to acknowledge/treat this problem and to represent their “own” people that should be represented.

The Crisis through the Eyes of the People: Citizens’ Interpretations on Social Media

Although the frames of Wilders and ordinary citizens overlap on the problem definition and the moral evaluation, citizens interpret the causes and solutions of the refugee crisis in somewhat different ways. Although ordinary citizens also shifted blame to the elites on the national level, they also blamed the refugees themselves for posing a threat on the people. Specifically, refugees were negatively stereotyped as so-called “fortune seekers”: people who only enter the Netherlands to profit without giving anything in return. Dehumanization was a central theme used to construct refugees as rats, snakes, dogs or pigs: “We will need to purify the houses of these rats. But as long as we get our country back, we will do whatever it takes”. Messages on the international Wilders supporters platform frequently blamed boat refugees of fleeing their country for economic gains, rather than a security threat: “Never done a day’s work in their lives all got decent clothes and mobiles in pockets.” Morally, the refugees were seen as profiting relatively more than the native people, which resonates with relative deprivation: “The asylum seekers can get a home without waiting, while ordinary Dutch citizens have to live on the streets for 12 years”.

Responding to the mediatized event surrounding the death of Alan Kurdi, refugees were blamed for their own fate: “He was the one who caused his son’s death, and then him and the family went back to live in Syria, obviously not so dangerous after all”. The media were accused of distorting reality, manipulating this image to influence public opinion on the refugee crisis: “That child was used in several photos in different locations. It was a media set-up to pull at the heart strings”. In that sense, the anti-immigrant and populist sentiments expressed by ordinary citizens can be connected to post-factual discourse and accusations of mis- and disinformation.

Although the solutions offered by citizens in the Facebook communities by and large resonate with Wilders’ solutions (RQ2), citizens frequently articulated more trust in their own agency and collective initiatives. They frequently saw it as the ordinary people’s responsibility to revolt and switch off the government. The Facebook communities frequently hosted “events” that mobilized people to come together and protest against the current government and their policies. Moreover, people had to wake up, and vote for the “right” party that did represent their will. In that sense, the native population could also be held accountable for solving the current crisis – they had to rely on their democratic rights to vote for their own government.

Based on the patterns of frame-elements in people’s communication through Facebook, we can identify three interpretation frames that differ from politicians’ discourse: (1) the “fortune seekers” interpretation that emphasizes that refugees are morally inferior to native people, and that refugees are responsible for their own fate; (2) the relative deprivation frame, that views the ordinary people as an in-group that is not receiving what it is morally entitled to, whereas refugees profit from the people’s resources and (3) the collective action frame, that emphasizes the responsibility of the people to collectively engage in protests to switch off the elitist government.

The Media’s Framing of the Refugee Crisis

As expected, the media’s discourse surrounding the refugee crisis reflected a more nuanced debate, largely devoid of explicit blame attributions and negative stereotyping (RQ2). Additionally, treatment recommendations were largely absent, as the crisis was seen as having many facets and involved actors at different levels of governance. However, the problem definition and moral evaluations differed between the broadsheet outlet de Volkskrant and the tabloid outlet de Telegraaf. De Volkskrant defined the refugee crisis mostly as a problem for the boat refugees, appealing to the moral obligation of native citizens to care for them. De Telegraaf, in contrast, defined the problem as a threat to native people, for example referring to metaphors as “tsunami” or “invasion” to problematize the flow of refugees as more than the country’s capacity. Morally, Dutch citizens were not seen as being responsible for solving the issue. The refugee population did not consist of “real” and “honest” people – and the “good” refugees that really needed shelter should be protected whereas the “evil” profiting immigrants should not be allowed to enter the country. In that sense, the ideological biases of the newspapers were reflected in the divergent framing of the refugee crisis: the left-wing broadsheet emphasized the obligation of Dutch people to look after refugees, whereas the right-wing popular outlet focused on the refugee crisis as a threat to the native people – further emphasizing the deprivation of the Dutch people on a cultural and material level.

DISCUSSION STUDY 1

The key findings of the first study demonstrate that Geert Wilders’ interpretation of the refugee crisis was overtly negative and hostile. Specifically, he blamed the corrupt elites for prioritizing the needs of refugees over their own people, and for not stopping the influx of refugees. Refugees were seen as the largest threat to the safety of the ordinary people – as many refugees were seen as terrorists, rapists and/or a threat on the welfare of the people. This framing resonated with citizens’ self-communication in online Facebook communities. These communities provided a safe space for a one-sided hostile discourse that scapegoated migrants and absolved native citizens of responsibility. In that case, these communities may foster polarized divides in society - contributing to the persistence of filter bubbles and echo chambers (Sunstein, Citation2009). Exposure to online right-wing populist discourse may thus have far-reaching political consequences. As an important next step, we need to understand the effects of anti-immigration messages on receivers’ perceptions of refugees.

STUDY 2: THE EFFECTS ON ANTI-REFUGEE FRAMING ON OUT-GROUP STEREOTYPES

The qualitative findings of Study 1 were used to inform the experimental study. Specifically, the central frame-elements of the problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation and treatment recommendation in politicians’ citizens’ and media coverage were manipulated to investigate the effects of right-wing populist messages on the activation of negative stereotypes towards immigrants.

Method Study 2

Design

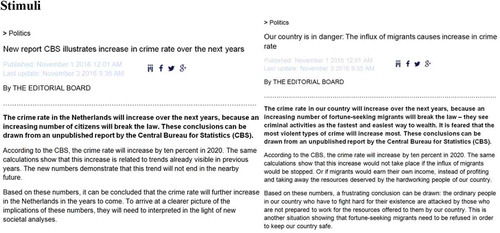

Based on the central content features identified in Study 1, we relied on a between-subject experimental design with three conditions. Participants were randomly exposed to (1) an anti-immigration message that blamed refugees for increases in the crime rate of the host country or (2) a counter-anti-immigration message that blamed the native people rather than the refugees for the increases in crime rate or (3) a control condition that did not use frame-elements problematizing the refugee crisis or blaming out-groups. The design, procedures and sampling procedures were approved by the ethics committee.

Sample

The survey-embedded experiment was completed by 277 participants (completion rate 71.3%). An international panel company (Survey Sampling International/Dynata) used different procedures to collect the data from a large panel of participants in the Netherlands. The composition of the final sample approached national representativeness on age, gender, education, region and previous voting behavior. The mean age of participants was 48.52 years (SD = 15.13). 52.7% was female. 19.5% of all participants had a lower level of education, 34.7% was higher educated, and 45.8% had a moderate level of education.

Procedure

The experiment was embedded in an online survey. Participants were invited to participate via e-mail. Upon clicking the invitation link, participants entered a screen were they opted-in for the survey. After this informed consent procedure, they were forwarded to the pre-treatment survey. They completed a number of items on demographics, political predispositions and attitudes towards refugees, politicians and the media. After this, they entered the treatment block. A cover story told them that they would read an online news item on a topic that recently gained prominence in politics and society. They were asked to read the news item as they would normally read online news. After the cover story, the news item was shown in a block that resembled a real online news environment. After reading the item (average reading time = 21.21 seconds (SD = 29.12)), participants were forwarded to the post-treatment survey that contained items on the dependent variables and manipulation checks.

Independent Variables

Based on the insights from Study 1, the problem of the refugee crisis was defined as rising levels of violent crimes in the Netherlands (safety threats). The causal interpretation emphasized that elites and refugees should be held accountable for increasing crime rates. The moral evaluation defined the ordinary people as innocent victims and the immigrants as evil outsiders. Finally, the treatment recommendation suggested to stop the influx of refugees – suggesting that the elites were not dealing with the issue adequately.

This right-wing populist frame was contrasted with a counter-frame that did not connect increases in the crime rate to the influx of migrants or elites. In contrast, ordinary native citizens were scapegoated for increases in crime rates targeted at migrants. The moral evaluation was also reversed: migrants were innocent victims of crimes committed by native citizens that attacked refugees. The proposed treatment was in line with this causal interpretation: ordinary Dutch citizens should become more welcoming to migrants that deserve help.

A final control condition reported on the same development of increasing crime rates, but did not connect this development to refugees or ordinary citizens. Rather, a neutral discussion of statistics and developments was offered to contextualize the development. Stimuli are included in Appendix (see ).

Dependent Variable

We measured stereotypical images of migrants using bi-polar scales that asked participants to rate migrants on a series of traits. Specifically, participants had to rate their position towards migrants on the pairs lazy-hardworking, dishonest-honest, not reliable- reliable and hostile-friendly. The items were all measured on 7-point scales that formed a unidimensional construct tapping into stereotypical anti-migrant attitudes (Cronbach’s α = .92, M = 4.11, SD = 1.30).

Perceived Relative Deprivation

Perceived relative deprivation was measured with a five-item scale. The item wordings were as follows: (1) “If we need anything from the government, ordinary people like us always have to wait longer than others” (2) I never received what I deserved” (3) “It’s always other people that profit from benefits offered in our country” (4) “The government does not care about the needs of ordinary people like me” and (5) “The government does not take care of people like me, others are always advantaged”. These items form a reliable unidimensional scale (Cronbach’s α = .92, M = 4.40, SD = 1.44). The items are based on existing scales (see e.g., Elchardus & Spruyt, Citation2016).

National Identification

Attachment to national identity was tapped with four items: (1) “I care about most other people in the Netherlands” (2) “I feel a strong attachment to the Netherlands” (3) “I am proud to be a Dutch citizen” (4) “Being Dutch is really important to me” (Cronbach’s α = .85, M = 4.92, SD = 1.27) (also see e.g., Lubbers (Citation2008).

Manipulation Checks

The manipulation of the right-wing anti-immigrant frame was successful. First of all, participants exposed to the anti-refugees frame were more likely to perceive the article as holding refugees accountable (M = 5.81, SD = 1.27) compared to the counter-message (M = 3.71, SD = 1.90) or the control (M = 3.65, SD = 1.89) ((F(2, 274) = 48.73, p < .001)). The counter anti-immigration message and control condition did not differ significantly, but they were both perceived as significantly less likely to shift blame to refugees compared to the anti-refugees frame (p < .001). This was expected, and can be explained as anti-immigration cues are absent in both conditions. Likewise, participants in this condition were more likely to recognize that the article emphasized how ordinary, native citizens are victimized (M = 5.24, SD = 1.56) compared to the control (M = 3.54, SD = 1.90) or counter-message (M = 3.75, SD = 1.91; (F(2, 274) = 24.81 p < .001). Again, differences were only significant between the anti-immigration message and the other two conditions. Finally, participants in the counter-anti-immigration message perceived the reversed causal interpretation of the article. Specifically, they were more likely to agree that the article held native people accountable (M = 4.76, SD = 1.81) compared to the anti-refugees (M = 2.52, SD = 1.66) or control condition (M = 4.04, SD = 1.71) (F(2, 274) = 41.45, p < .001). In this case, all pairwise differences were significant (p < .001).

Results Study 2

The Direct Effect of Anti-refugees Messages on Negative Stereotypes

Ceteris paribus, we expected that exposure to messages that blame refugees for the problems experienced by the native people would prime negative stereotypical portrayals towards migrants (H1). A one-way ANOVA demonstrates that the main effect of the conditions on negative stereotypes towards migrants approaches significance (F(1, 277) = 2.68, p = .071, partial η2 = 0.027). Zooming in on the pairwise comparisons, we see that participants in the anti-refugees conditions have stronger negative stereotypes towards migrants (M = 4.35, SD = 1.38) compared to participants in the neutral control conditions (M = 3.97, SD = 1.31; ΔM = .38, ΔSE = .21, t = 1.84, p = .007, 95% CI [.02, .76]). H1 can thus partially be supported, although the difference falls short of statistical significance.

The Moderating Role of Perceived Relative Deprivation

To investigate the role of relative deprivation, and to factor in the hypothesized mechanisms of motivated reasoning, we computed new conditions that take the congruence of the message with people’s prior perceptions of relative deprivation into account.

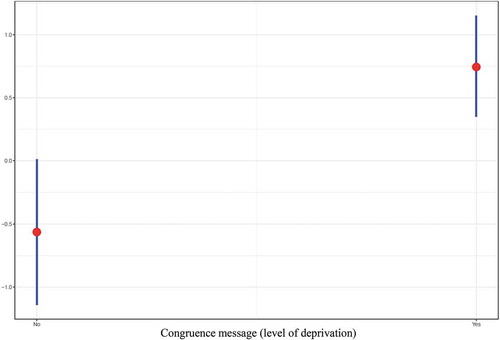

As can be seen in , the effect of the message’s congruence is highly significant. Specifically, we see that the anti-refugee message has a significantly stronger effect on the priming of negative stereotypes when this message is congruent with perceived relative deprivation than when the message is incongruent (ΔM = .84, ΔSE = .26, p = .017, 95% CI [.09, 1.57]. In support of H2a, we can conclude that right-wing populist communication is most persuasive for people with stronger levels of perceived relative deprivation. Moreover, the mean difference of stereotypical perceptions between the incongruent, anti-refugees condition and the control is not significant and even negative – indicating that participants at lower levels of perceived deprivation resisted persuasion by messages that attribute blame to refugees. This supports H2b.

TABLE 1 The Effects of Anti-refugees Messages and Counter Anti-immigration Messages on Negative Stereotypes toward Migrants at Different Levels of Attitudinal Congruence

This finding is confirmed by the mean score comparisons of participants exposed to counter-messages that blame the native people rather than refugees. When the counter-message is congruent, less negative stereotypes towards migrants are primed than when this counter message is incongruent (see ). This means that a counter-message activates existing positive stereotypes towards migrants among people lower in perceived deprivation, whereas the counter-message is resisted by people at higher levels of relative deprivation. displays this effect graphically. Specifically, shows that incongruent anti-immigration content has a negative effect, and congruent anti-immigration has a positive effect on the activation of negative stereotypes. Taken together, these findings support the processing mechanism of motivated reasoning conditioning the effects of anti-refugees media content.

The Perceptual Screen of National Identification

We finally hypothesized that the persuasiveness of right-wing populist communication would be contingent upon participants’ attachment to national identity (H3). As can be seen in , national identification does not condition the effect of exposure to anti-refugees or counter-messages on stereotypical images of migrants. In addition, people at higher levels of national identity are not significantly more likely to have negative stereotypes towards migrants (, Model I). Based on these results, H3 needs to be rejected: right-wing populist communication that relies on anti-refugees framing does not have the strongest effects for people that identify with the nation-state.

TABLE 2 The Effects of Anti-refugees Messages and Counter Messages on Negative Stereotypes toward Migrants Conditioned by National Identification

Discussion Study 2

Study 2 relied on an online experiment to investigate the effects of blaming refugees for increasing crime rates. The key findings indicate that the main effect of such messages is minimal, and that attitudinal congruence plays a key role in the persuasiveness of anti-immigration discourse. Specifically, messages that blame refugees for national issues activate negative stereotypes towards migrants among people higher in perceived relative deprivation and are counter-argued by people lower in perceived deprivation. This is in line with recent research that has identified polarization as a consequence of exposure to right-wing populist content (Hameleers, Bos, & de Vreese, Citation2018; Müller et al., Citation2017).

The mechanism underlying these effects can be understood as motivated reasoning (Taber & Lodge, Citation2006) and cognitive dissonance (Festinger, Citation1957). Specifically, anti-refugees messages may activate negative mental images towards migrants (Dixon, Citation2008), but may only do so when these mental images are available in the minds of receivers. This study demonstrated that perceptions of relative deprivation are a proxy for the availability of congruent prior attitudes. This is in line with recent research by Elchardus and Spruyt (Citation2016) who identified that the perception of losing out relatively more than other groups in society plays a central role in predicting populist support.

This finding can also be explained in light of the cultivation of social identities. Literature on the mobilizing potential of social identity framing postulates that three elements are important to consider when predicting the effects of identity-framed content (Gamson, Citation1992; Polletta & Jasper, Citation2001). First, a threat to the in-group needs to be emphasized. Second, a credible scapegoat need to be connected to this threat. Finally, efficacy beliefs need to be presented, meaning that receivers of identity-framed content need to be offered tools to avert the cultivated threat. Our manipulation of right-wing populist messages incorporated all these elements. First of all, refugees were framed as a severe threat to the in-group of ordinary native citizens – as the violent crimes committed by refugees pose a danger on the safety of the people. Second, the profiting and dangerous migrants were causally connected to the increasing crime rates. Finally, efficacy was cultivated by recommending a treatment: the influx of refugees should stop, and culpable migrants should be send back to their country of origin. In line with the social identity framing approach, we found that right-wing populist communication can prime negative portrayals of the out-group when such communication resonates with feelings of relative deprivation. For these citizens, the cultivated threat is personally relevant, and the migrants form a credible scapegoat.

Contrary to our expectations, we did not find stronger effects of anti-refugees framing for people that identify strongly with the nation-state. This unexpected finding can be interpreted by the results of the qualitative study. Even in the nationalist communities, people constructed a sense of detachment from the current state of their nation. They voiced the concern that this country is no longer their country. Because of the processes of European unification, the perceived overwhelming influx of refugees and the “islamatization” of the heartland, people stressed that they no longer felt at home. In light of these qualitative findings, people that perceived the experimental message as congruent with their prior attitudes may actually experience a weaker attachment to national identity. This also explains the strong role of perceived relative deprivation. In other words, people “lost” their connection to the nation-state to other groups that have entered the nation.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

In the setting of a heated debate on the refugee crisis in Europe, this paper first of all relied on a qualitative content analysis to provide inductive insights into the discursive framing of the refugee crisis (Study 1). Second, based on Study 1, we investigated how anti-immigration framing can activate message-congruent, negative stereotypes towards migrants (Study 2).

The findings of this study have important implications for democratic communication. First of all, right-wing populist discourse may only appeal to a specific group of citizens, and this group is empowered to communicate their hostile discourse via social network sites. On these platforms, there is no room for democratic deliberation (also see Waisbord, Citation2018). Rather, people base their arguments on an emotional, conflict-centered discourse rather than a deliberation of facts. These fact-free sentiments are not challenged by other citizens, but rather reinforced by like-minded citizens and politicians. People may thus shut themselves off in spaces that only reflect their own opinions and sentiments (Sunstein, Citation2009). The experimental study showed that communication in spaces that are devoid of cross-cutting exposure can have polarizing consequences: people that already agree with the attitudinal stance of anti-immigrant message may become even more negative toward immigrants. People exposed to incongruent content may become stronger in their opposition to anti-immigration sentiments.

Our studies have some limitations. First of all, the content analysis zoomed in on communities that are prone to populist sentiments. We did not include comment pages of mainstream news websites, or other platforms that may allow for more democratic communication. In addition, the analyses focused on one country with a successful right-wing populist party. Messages that resonate less well with country-level opportunity structures may have weaker effects (Aalberg et al., Citation2017). Second, the experiment only manipulated one salient right-wing topic (crime) and did not explicitly blame the elites for the refugee crisis. The message may have appealed to different citizens if different issues and scapegoats were foregrounded. Future research may expand the (qualitative) content analysis to commentary sections and alternative media platforms that allow non-professional communicators to express their sentiments. In addition, experimental research may vary out-group constructions. Does it matter when “refugees” or “migrants” are held responsible, and how credible is it to frame blame to religious out-groups, such as the Islam?

Despite these limitations, we believe that this study has offered important insights into the discursive framing of the European refugee crisis, and the political consequences of communicating right-wing populist sentiments targeted at refugees via online media. Especially when people’s perceptual screens align with anti-immigration messages, negative stereotyping in (online) media content can activate negative out-group perceptions.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael Hameleers

Michael Hameleers (Ph.D., University of Amsterdam, 2017) is an Assistant Professor in Political Communication in the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR) at the University of Amsterdam. His research interests include populism, disinformation, framing, (affective) polarization, and the role of social identity in media effects.

References

- Aalberg, T., Esser, F., Reinemann, C., Strömbäck, J., & de Vreese, C. H. (2017). Populist political communication in Europe. London, UK: Routledge.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London, UK: Sage.

- Cacciatore, M. A., Scheufele, D. A., & Iyengar, S. (2016). The end of framing as we know it … and the future of media effects. Mass Communication & Society, 19(1), 7–13. doi:10.1080/15205436.2015.1068811

- Canovan, M. (1999). Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies, 47, 2–16. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00184

- Coutin, S. B., & Chock, P. P. (1997). “Your friend, the illegal”: Definition and paradox newspaper accounts of U.S. immigration reform. Identity, 2, 123–148. doi:10.1080/1070289X.1997.9962529

- De Cleen, B., & Stavrakakis, Y. (2017). Distinctions and articulations: A discourse theoretical framework for the study of populism and nationalism. Javnost – the Public, 44(4), 301–319. doi:10.1080/13183222.2017.1330083

- Dixon, T. L. (2008). Crime news and racialized beliefs: Understanding the relationship between local news viewing and perceptions of African Americans and crime. Journal of Communication, 58, 106–125. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00376.x

- Dixon, T. L., & Williams, C. L. (2015). The changing misrepresentation of race and crime on network and cable news. Journal of Communication, 65(1), 24–39. doi:10.1111/jcom.1233

- Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2010). Personality, ideology, prejudice, and politics: A dual-process motivational model. Journal of Personality, 78(6), 1861–1894. doi:10.1111/jopy.2010.78.issue-6

- Elchardus, M., & Spruyt, B. (2016). Populism, persistent republicanism and declinism: An empirical analysis of populism as a thin ideology. Government and Opposition, 51(1), 111–133. doi:10.1017/gov.2014.27

- Engesser, S., Ernst, N., Esser, F., & Büchel, F. (2017). Populism and social media: How politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Information, Communication & Society, 20(8), 1109–1126. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1207697

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–59. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson & Company.

- Gamson, W. A. (1992). Talking politics. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Gamson, W. A., & Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology, 95(1), 1–37. doi:10.1086/229213

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Hameleers, M., Bos, L., & de Vreese, C. H. (2017). “They did it”: The effects of emotionalized blame attribution in populist communication. Communication Research, 44(6), 870–900. doi:10.1177/0093650216644026

- Hameleers, M., Bos, L., & de Vreese, C. H. (2018). Selective exposure to populist communication: How attitudinal congruence drives the effects of populist attributions of blame. Journal of Communication, 68(1), 51–74. doi:10.1093/joc/jqx001

- Hameleers, M., & Schmuck, D. (2017). It’s us against them: A comparative experiment on the effects of populist messages communicated via social media. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1425–1444. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328523

- Hobolt, S. B., & Tilley, J. (2014). Blaming Europe? Responsibility without accountability in the European Union. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Iyengar, S., & Hahn, K. S. (2009). Red media, blue media: Evidence of ideological selectivity in media use. Journal of Communication, 59, 19–39. doi:10.1111/jcom.2009.59.issue-1

- Kim, S. H., Carvalho, J. P., Davis, A. G., & Mullins, A. M. (2011). The view of the border: News framing of the definition, causes, and solutions to illegal immigration. Mass Communication and Society, 14(3), 292–314. doi:10.1080/15205431003743679

- Krämer, B. (2014). Media populism: A conceptual clarification and some theses on its effects. Communication Theory, 24(1), 42–60. doi:10.1111/comt.12029

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2006). Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: Six European countries compared. European Journal of Political Research, 45(6), 921–956. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00644.x

- Lubbers, M. (2008). Regarding the Dutch “nee” to the European constitution: A test of the identity, utilitarian and political approaches to voting “no.”. European Union Politics, 9, 59–86. doi:10.1177/1465116507085957

- Matthes, J., & Kohring, M. (2008). The content analysis of media frames: Toward improving reliability and validity. Journal of Communication, 58, 258–279. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00384.x

- Matthes, J., & Schmuck, D. (2017). The effects of anti-immigrant right-wing populist ads on implicit and explicit attitudes: A moderated mediation model. Communication Research, 44(4), 556–581. doi:10.1177/0093650215577859

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 542–564. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Müller, P., Schemer, C., Wettstein, M., Schulz, A., Wirz, D. S., Engesser, S., & Wirth, W. (2017). The polarizing impact of news coverage on populist attitudes in the public: Evidence from a panel study in four European democracies. Journal of Communication, 67(6), 968–992. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edw037

- Polletta, F., & Jasper, J. M. (2001). Collective identity and social movements. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 283–305. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.283

- Schmuck, D., & Matthes, J. (2017). Effects of economic and symbolic threat appeals in right‐wing populist advertising on anti‐immigrant attitudes: The impact of textual and visual appeals. Political Communication, 34, 607–626. doi:10.1080/10584609.2017.1316807

- Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Going to extremes: How like minds unite and divide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Sutherland, C. (2005). Nation-building through discourse theory. Nations and Nationalism, 11(2), 185–202. doi:10.1111/j.1354-5078.2005.00199.x

- Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50, 755–769. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x

- Taggart, P. (2000). Populism. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Van Kessel, S., & Castelein, R. (2006). Shifting the blame. Populist politicians’ use of Twitter as a tool of opposition. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 12(2), 559–614.

- Waisbord, S. (2018). Why populism is troubling for democratic communication. Communication, Culture and Critique, 11(1), 21–34. doi:10.1093/ccc/tcx005

- Waisbord, S., & Amado, A. (2017). Populist communication by digital means: Presidential Twitter in Latin America. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1330–1346. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328521