ABSTRACT

The literature on emotional expression on Social Network Sites (SNSs) is still in its infancy. It is assumed that SNSs are subject to a positivity bias: individuals share positive aspects of their lives on SNSs rather than negative ones. However, sentiment analysis studies have shown that this bias might not be appropriate for all SNSs, particularly Twitter. This research aimed to understand how the emotions of a message impact the choice of the SNS used to publish it. Four pre-registered experimental studies were conducted (N = 449). Participants were presented with a message – text and image – and asked if it were most likely to be published on Twitter or Instagram. The emotional valence of this message was manipulated in experiments 1a and 1b, as well as emotional arousal in experiments 2a and 2b. The results indicated that Instagram was preferred for positive messages. But the platform was also chosen for messages displaying low negative emotions, such as boredom or lassitude. Twitter was associated with messages displaying highly negative emotions, such as anger or distress. This research emphasizes the social norms that govern both platforms and demonstrates the interdependence between SNSs architecture, user motivations, and social context.

Social Network Sites (SNSs) have become increasingly important in our daily lives; more than half of the world’s population is regular users (Bouissiere, Citation2021). Scientists did not miss the opportunity to examine how they are involved in human interactions (Sundar, Citation2015). In a few years, SNSs have become objects of study, which do not radically change human behaviors but offer new environments (Amichai-Hamburger, Citation2013). One major field in psychology did not escape this trend, that of emotional expression.

According to the component process model, emotion should not be considered as a state but as a process that goes through several components (Scherer, Citation1982). One of these components – subjective feeling – is particularly relevant in the context of SNSs because it deals with “the conscious aspect of the emotional process” (Dan-Glauser, Citation2019, p. 226). Subjective feeling is therefore measurable through verbal rapport, but its conceptualization is still a debated topic in the literature (Sander & Scherer, Citation2019). A discrete perspective considers the existence of basic emotions, such as joy, anger, or sadness (Ekman, Citation1992). A dimensional perspective considers that there are an infinite number of emotions and that they are not independent of each other (Russell, Citation1980). From this view, there are at least two dimensions to emotions: valence and arousal (Barrett & Russell, Citation1998). Valence relates to “the positive or negative character of emotions” (Brosch & Moors, Citation2009, p. 401), whereas arousal deals with “the level of excitement that an observer experiences” (Kurdi et al., Citation2017, p. 458).

It is now recognized that computer-mediated communication is not a barrier to emotional expression (Derks et al., Citation2008). Online interactions can match or even surpass the emotional level of offline exchanges (Walther, Citation1996). SNSs are a type of computer-mediated communication, and the same conclusions apply to them (Rimé et al., Citation2020). They can be defined as platforms where users have a personal profile, are publicly connected to other users, and can produce, consume, or interact with content published by others (Ellison & Boyd, Citation2013). But emotional expression on SNSs seems to require due consideration. Indeed, the literature suggests the existence of a positivity bias: “the SNS environment […] favors positive forms of authenticity over the presentation of negative aspects of the true self” (Reinecke & Trepte, Citation2014, p. 95). In other words, individuals prefer to share on SNSs events that evoke positive emotions such as joy or surprise, rather than negative ones such as anger or sadness (Thelwall et al., Citation2010).

The positivity bias has been proposed with respect to Facebook and its process (Reinecke & Trepte, Citation2014). Although it is the world leader in SNSs, there is a multitude of other platforms (Blank & Lutz, Citation2017). Each of these platforms has its own particularities, and users are therefore motivated to use them for different reasons. Facebook allows to satisfy the need to belong and the need for self-presentation (Nadkarni & Hofman, Citation2012), whereas Instagram aims at creativity, coolness, self-documentation and knowledge about others (Sheldon & Bryant, Citation2016). Twitter, for its part, is mostly used for informational purposes (Johnson & Yang, Citation2009). Studies in the field of sentiment analysis – which consists in identifying the emotions of a textual source – showed that the positivity bias might not be appropriate for Twitter. Indeed, Twitter posts on popular events are related to an increase in the strength of negative emotions, regardless of the initial valence of these events (Thelwall et al., Citation2011). In addition, posts containing negative emotions are more likely to be shared on the platform (Jiménez-Zafra et al., Citation2021; Naveed et al., Citation2011). Manikonda et al. (Citation2021) compared specifically Twitter and Instagram posts. They found that the former mostly expressed negative emotions and swear words, whereas the latter was about positive emotions such as happy personal moments. Although the sentiment analysis methodology is informative, it does not provide insight into the reasons for this phenomenon; the results are mainly descriptive. In addition, Twitter allows free access to data with a clear application programming interface, but this is not the case for most other SNSs, which limits comparison (Tufekci, Citation2014).

Several factors may explain why the emotions expressed differ according to the SNS. First, it is possible to consider the SNS architecture, “the structural design” (Bossetta, Citation2018, p. 471). For example, Instagram is an image-based SNS, whereas Twitter is a text-based SNS (Pittman & Reich, Citation2016). One interpretation could be that images lead to the search for a visual ideal and therefore tend toward positive elements, whereas on Twitter, the fact of having to write short texts leads to focus on negative elements. However, recent work suggests that it is not only formal constraints that may explain why individuals use one SNS in a certain way but also the social context (Boczkowski et al., Citation2018). Indeed, users constantly alternate between different platforms because there are social barriers specific to each of them (Tandoc et al., Citation2019). Therefore, some studies have specifically focused on social norms on SNSs (Marwick & Boyd, Citation2011; McLaughlin & Vitak, Citation2012; van Dijck, Citation2013).

Social norms have been the subject of much theorizing in psychology (for a review, see Girandola & Fointiat, Citation2016). The focus theory of normative conduct posits that there are two types of norms: injunctive and descriptive (Cialdini et al., Citation1990, Cialdini et al., Citation1991). Injunctive norms characterize “the perception of what most people approve or disapprove” (Cialdini et al., Citation1991, p. 203). Descriptive norms do not focus on what people think is right or wrong, but rather on “what other people do in any given situation” (Cialdini & Trost, Citation1998, p. 155). Social norms could therefore influence what individuals share on SNSs, either because they anticipate social sanctions to deviate from them or because it is what seems most suitable and effective, as performed by others. To our knowledge, only one study has looked at the social norms of emotional expression on SNSs. Waterloo et al. (Citation2018) highlighted that the positive emotions were perceived as more appropriate for Instagram and Facebook followed by Twitter, whereas the negative emotions were more for Twitter and Facebook followed by Instagram.

This line of research has not been greatly developed; yet, the expression of emotions on SNSs can shed light on many other phenomena. Emotions are at the heart of many human behaviors. For example, anger is a predictor of protest movements (van Zomeren, Citation2013; van Zomeren et al., Citation2012). Can viewing negative content on SNSs possibly change the dynamics of these movements? In the same way, can negative contents have deleterious effects on individuals, given that we know that digital well-being depends in part on the content viewed on SNSs (Meier & Reinecke, Citation2021; Vanden Abeele, Citation2021)? Albeit an important advance in the field, the study of Waterloo et al. (Citation2018) is cross-sectional. This type of study design does not allow for examining causal links that are sorely lacking in social media research (Griffioen et al., Citation2020).

In other words, the literature on emotional expression on SNSs is still in its infancy. Although it seems that SNSs are subject to a positivity bias, sentiment analysis studies have shown that Twitter users are more likely to publish negative emotions than positive ones. Waterloo et al. (Citation2018) provided interesting explanations related to social barriers to emotional expression on SNSs. However, the literature cannot determine whether emotional expression on SNSs depends on social context and not on other factors, such as architecture. An experimental study could directly test whether a type of emotional content is consistently associated with a type of SNS.

The Present Investigation

The aim of this research is to understand how the emotions of a message impact the choice of the SNS used to publish it. When individuals want to share an event on SNSs, do they choose a platform according to the emotions associated with this event? A related objective is to explore the role played by social norms in this phenomenon.

We decided to compare two SNSs: Instagram and Twitter. We chose these platforms because they are the ones most often opposed in the literature (Manikonda et al., Citation2021; Waterloo et al., Citation2018). As mentioned before, they differ in terms of architecture: although it is possible to publish images on Twitter, it is often considered that Instagram focuses on image and Twitter on text (Pittman & Reich, Citation2016).

Four experimental studies were conducted to answer these research questions. Experiments 1a and 1b aimed to test whether the emotional valence of a post affected the choice of Instagram or Twitter to publish it. Experiments 2a and 2b further investigated the results of these initial studies by focusing, in addition, on emotional arousal.

Transparency and Openness

To ensure transparency and openness, all experiments were pre-registered on Open Science Framework (OSF). Pre-registrations can be viewed at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4B8SD for experiment 1a, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/Z2B4T for experiment 1b, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8P5MS for experiment 2a, and https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BPK83 for experiment 2b. In addition, data and research materials have been made publicly available on OSF and can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/VMKXC.

Experiments 1a and 1b: Valence’s Impact on Instagram and Twitter

In experiments 1a and 1b, participants were presented with a message – text and image – and asked on which SNS it were most likely to be published (Twitter vs. Instagram). As explained, the emotional valence of this message was manipulated (Positive vs. Negative). In addition, we manipulated the position of the image (Below the text vs. Above the text). Instagram is an image-based SNS, the publications are presented with a photo and a text underneath. Manipulating the position of the image allows us to check if the photo salience affects the choice of the SNS. Because the architecture of Instagram leads to photos being above the text, proposing another presentation for the photos allows us to verify the impact of this architecture’s features on the choice of SNSs.

The literature highlights that Instagram publications are more positive than Twitter publications (Jiménez-Zafra et al., Citation2021; Manikonda et al., Citation2021; Naveed et al., Citation2011; Thelwall et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, Waterloo et al. (Citation2018) emphasized that the norms of emotional expression on Instagram and Twitter differ in the same way. Based on this literature and on the results of Experiment 1a for Experiment 1b, several hypotheses have been proposed. summarizes the hypotheses that have been pre-registered for each experiment.

Table 1. Pre-registered hypotheses for experiments 1a and 1b.

Experiment 1a

Method

Participants and procedure

The sample size was determined a priori by power analysis using G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., Citation2007). For an alpha level of .05, with 80% power and a medium effect size (.3), the required sample size for examining with a chi-square test our main hypotheses was 88 participants. We first created four questionnaires using LimeSurvey software, one for each experimental condition. To ensure randomization, a random URL was then created using the Google Script application.Footnote1 A convenience sample was finally collected by posting the survey link on researchers’ SNSs and asking participants to share in turn the study. Using this method, 209 individuals have voluntarily consented to participate, from which were removed those who did not fully complete the study, who failed the manipulation checkFootnote2 or did not have an Instagram and Twitter accounts. As pre-registered, the final sample is composed of 88 participants.Footnote3 Data collection took place from June 13 to June 26, 2020.

Regarding demographic characteristics, the sample consisted of 66 women, 19 men, and 3 individuals with another gender identity (Mage = 24.80, SDage = 5.84). All participants had an Instagram account and a Twitter account. Finally, 28 were employed, one was on long-term leave, 42 were students, 12 were unemployed, three were homemakers, and two were in another situation.

Materials

The experimental materials consisted of a message containing a text of up to 280 characters and a copyright-free image from Pixabay.com. Two pairs of images and texts were chosen on the theme of the city of Paris: one positive and one negative. The images were of the same size and did not show a person to avoid attractiveness or gender bias. A pretest was conducted on 44 psychology students (40 women and 4 men; Mage = 22.91, SDage = 5.56). Pretest participants had to rate the valence of the images, the texts, and the two pairs on a 7-point semantic differentiator (−3 = Very negative; 3 = Very positive). Three paired-samples t-tests showed that the two texts, the two images and the two pairs were significantly opposed in terms of valence (p < .05). The stimuli are available on the OSF (see “Transparency and Openness” section).

Measures

Participants first specified whether they had an Instagram and Twitter account. Adapted from Nick et al. (Citation2018), Twitter and Instagram frequencies of use were also measured by a single item on a 5-point scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = a few times, 4 = often, 5 = regularly).

After reading the message (image and text), the following instruction was displayed: “In your opinion, this text and/or this image are more likely to be published on…..” Participants could then choose between Instagram or Twitter (the main dependent variable).

For the measures of social norms, descriptive norms were derived from Lapinski et al. (Citation2017). For each SNS, participants responded to three items on a 7-point scale (1 = very negative; 7 = very positive). An example item is: “The people who influence my behavior post content on [Twitter][Instagram] mainly … .” The internal consistency is satisfactory, with a McDonald’s ω of .81 for Twitter and of .67 for Instagram. Adapted from Waterloo et al. (Citation2018), injunctive norms were also measured with three items (e.g., “The people who influence my behavior expect me to post content on Twitter mainly … ”). Participants could again respond on a 7-point scale (1 = very negative; 7 = very positive). The internal consistency is satisfactory (ω = .90 for Twitter, ω = .90 for Instagram).

After answering some sociodemographic questions (gender, age, and living situation), a control check question was presented to ensure that emotional valence was successfully manipulated. Participants answered the question, “In your opinion, the text and the image you saw were … ” on a 7-point scale (1 = very negative; 7 = very positive).

Results and discussion

All the analyses for all studies were carried out on the JASP software (JASP Team, Citation2020) and with the PROCESS macro on the SPSS software (Hayes, Citation2017).

Valence’s impact on Instagram or twitter choice

To test the impact of message valence and image position on Instagram or Twitter choice, we performed a binomial logistic regression.Footnote4 Neither image position nor the interaction between image position and message valence significantly predicted the choice of Instagram or Twitter (p > .05). The only significant effect was for the message valence, B = 3.18, Wald χ2(1) = 14.40, p < .001, OR = 24.00, 95% CI OR [1.54, 4.82].

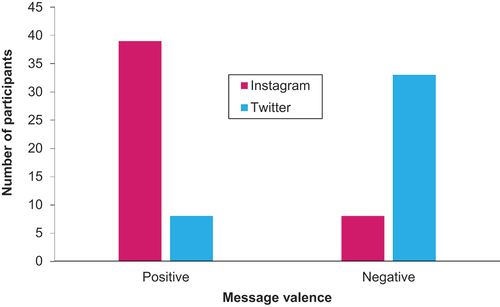

Since we didn’t find a significant effect of image position, following our pre-registration, the data have been collapsed across emotional valence variable. A continuity correction χ2 test showed a significant association between message valence and Instagram or Twitter choice, χ2(88, 1) = 32.94, p < .000, Phi = .64 (p < .000). As we can see in , when the publication was positive (n = 47), Instagram was chosen 39 times and Twitter 8 times. Whereas, when the publication was negative (n = 41), Instagram was chosen 8 times and Twitter 33 times.

These results are consistent with the literature: Instagram appears to be more often associated with positive messages and Twitter with negative ones (Jiménez-Zafra et al., Citation2021; Manikonda et al., Citation2021; Naveed et al., Citation2011; Thelwall et al., Citation2011). Notably, the effect size was strong (Phi = .64), demonstrating that emotional valence had a considerable impact on SNS choice. Hypotheses 1 and 2 are confirmed. Although Twitter is a text-based SNS (Pittman & Reich, Citation2016), the presence of an image in each experimental condition did not prevent participants from choosing it. Similarly, salience of the image was not significantly associated with SNS choice. This result is directly related to studies highlighting the impact of social context on SNSs utilization; SNSs architecture is not the only indicator of how and when people use them (Boczkowski et al., Citation2018; Tandoc et al., Citation2019). It should be noted, however, that a non-significant result cannot be interpreted as the absence of an association: we can neither confirm nor reject our hypothesis 3. In order to test a null hypothesis, we should have performed equivalence tests or used a Bayesian approach (Quertemont, Citation2011).

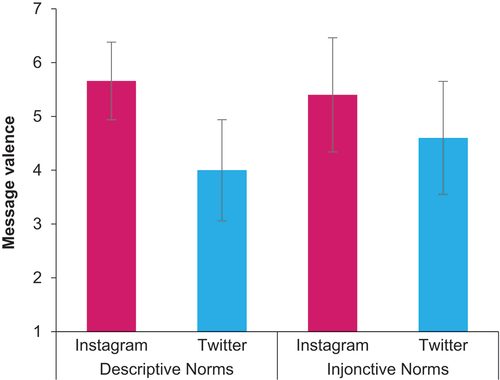

Social norms of emotional expression

We then looked at the norms of emotional expression on Instagram and Twitter (). The descriptive norms were more positive for Instagram (M = 5.66, SD = .72) than for Twitter (M = 4.00, SD = .94), t(87) = 14.55, p < .000, Cohen’s d = 1.55. The injunctive norms were also more positive for Instagram (M = 5.40, SD = 1.06) than for Twitter (M = 4.60, SD = 1.05), t(87) = 7.39, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .79.

In order to verify whether the injunctive norms are responsible for the effect of message valence on SNS choice, we carried out mediation analyses with 5000 bootstrap samples (Hayes, Citation2017). Results showed that injunctive norms on Twitter and on Instagram did not mediate the association between message valence and SNS choice: direct effect was significant (95% CI [1.90, 4.12]), while indirect effects (95% CI [−.09, .64] for Instagram, 95% CI [−.23, .17] for Twitter) and total effect (95% CI [−13, .60]) were non-significant. The same results were found for descriptive norms: direct effect was significant (95% CI [1.84, 4.04]), while indirect effects (95% CI [−.17, .33] for Instagram, 95% CI [−.13, .49] for Twitter) and total effect (95% CI [−14, .56]) were non-significant.

As expected, the injunctive norms were more negative for Twitter than for Instagram (Waterloo et al., Citation2018). Our results showed that the same is true for descriptive norms. However, these norms did not mediate the association between message valence and SNS choice (hypothesis 4 rejected). This phenomenon can be explained by the following limitations. One might question whether norms were measured correctly, it is possible that participants were subject to a social desirability bias and were unable to concede the presence of negative emotions on SNSs (Tournois et al., Citation2000). Another explanation could be that the distinction between descriptive and injunctive norms is too tenuous for participants and that it would be better to measure a more general norm. Finally, it is also possible that norms are not the only factor explaining participants’ choices.

Exploratory analyses

Finally, we examined if the frequency of use of Instagram and Twitter could explain the SNS choice. Indeed, it is possible that individuals who often use a platform choose it by habit rather than by the content of the message. We conducted a binomial logistic regression to test the effects of valence message, frequency of Instagram use, and frequency of Twitter use on SNS choice. Results revealed that only message valence had a significant effect on the choice of Instagram or Twitter, B = 3.11, Wald χ2(1) = 28.31, p < .001, OR = 22.52, 95% CI OR [1.97, 4.26].

This finding further highlights the importance of social context in emotional expression on SNSs (Boczkowski et al., Citation2018; Tandoc et al., Citation2019). Since the frequencies of use of Instagram and Twitter did not have a significant effect on the choice of SNS, it would also be interesting to investigate whether even people who do not have these platforms are aware – even implicitly – of these norms of emotional expression. In other words, do people who do not use Instagram and Twitter know that one is associated with positive content and the other with negative content? Is the social context of SNSs pervasive?

Experiment 1b

The objective of experiment 1b was to replicate experiment 1a using a different sample by addressing some of these limitations. In order to continue to explore the impact of emotional expression norms, a new, more general measure was proposed. In addition, individuals with both Instagram and Twitter accounts were compared to those with only one or neither of these SNSs to test the generalization of the results of experiment 1a.

Method

Participants and procedure

As in experiment 1a, four anonymous questionnaires were created and redirect to a random URL (Fergusson, Citation2016). The experiment was conducted during a psychology online lecture course. The sample size was determined based on available resources; at the time of pre-registration, the number of students taking part in the lecture course was around 100. To be sure that this number of participants would be sufficient, we performed a sensitivity analysis for a goodness-of-fit test; with an alpha of .05, a power of .08, and a sample size of 100, we had enough power to detect a medium Phi effect size (.28). Data collection took place on October 16, 2020; 104 people have voluntarily consented to participate, from which were removed those who did not fully complete the study. The final sample comprises 102 participants.

The sample consisted of 90 women, 10 men, and two people with another gender identity (Mage = 20.38, SDage = 2.66). All participants were students, 65 had both an Instagram and a Twitter accounts, and 37 had only one of them or none.

Materials

The experimental material was the same as in experiment 1a.

Measures

Having an Instagram and Twitter accounts, frequency of use of these SNSs, SNS choice (the dependent variable), manipulation check as well as sociodemographic questions were measured in the same way as in experiment 1a.

In addition, a new measure of emotional expression norms has been proposed based on the “Self-Assessment Manikin” (SAM; Bradley & Lang, Citation1994). The advantage of this scale is that it measures emotions through pictograms. Participants could answer the question, “In your opinion, which of these pictures is the most representative of a user about to post a message on [Twitter][Instagram]?” by choosing one of the five SAM valence pictures or between two of them, resulting in a 9-point scale.

Finally, we added a question regarding the number of SNSs used per week (1 = none, 2 = one, 3 = between two and four, 4 = between five and ten, 5 = more than ten).

Results and discussion

Valence’s impact on Instagram or twitter choice

We carried a binomial logistic regression on SNS choice for image position, message valence, having an Instagram and Twitter accounts, and all possible interactions.Footnote5 The only significant effect was for message valence, B = −2.59, Wald χ2(1) = 6.34, p < .05, OR = .08, 95% CI OR [.010, .563].

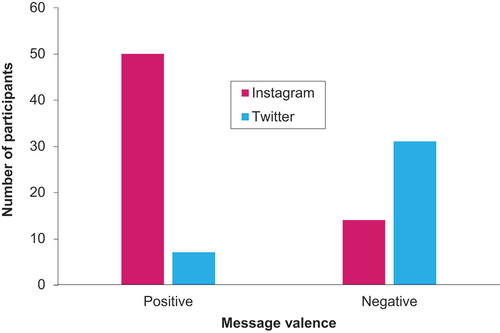

As pre-registered, data have been collapsed across the emotional valence variable. A continuity correction χ2 test showed a significant association between message valence and Instagram or Twitter choice, χ2 (1) = 32.09, p < .000, Phi = .58. When the publication was positive (n = 57), Instagram was chosen 50 times and Twitter 7 times. When the publication was negative (n = 45), Instagram was chosen 14 times and Twitter 31 times ().

These results confirmed those of experiment 1a in a different sample. Again, the hypotheses 1 and 2 were validated: Instagram was associated with positive content and Twitter with negative content (Jiménez-Zafra et al., Citation2021; Manikonda et al., Citation2021; Naveed et al., Citation2011; Thelwall et al., Citation2011). Similarly, the position of the image did not have a significant effect on SNS choice: having the image above the text did not cause participants to choose Instagram more often. This research also complements experiment 1a by demonstrating that owning an Instagram account and a Twitter account did not have a significant effect on our dependent variable.Footnote6 Therefore, we may assume that the perception of Instagram as a positive SNS and Twitter as a negative SNS is consensual and diffuse in our society.

Social norms of emotional expression

The norms of valence expression were more positive for Instagram (M = 3.05, SD = 1.67) than for Twitter (M = 4.74, SD = 2.04), t(101) = −7.55, p < .000, Cohen’s d = −.75.

To test hypothesis 4, we conducted a mediation analysis with 5000 bootstrap samples (Hayes, Citation2017). Results showed that norms on Twitter and Instagram did not mediate the association between the message valence and the SNS choice: direct effect was significant (95% CI [1.76, 3.79]), while indirect effects (95% CI [−.13, .16] for Instagram, 95% CI [−.15, .13] for Twitter) and total effect (95% CI [−18, .19]) were non-significant.

Despite the use of pictograms to measure emotional expression norms on SNSs (Bradley & Lang, Citation1994), we did not demonstrate that these norms explain the effects of message valence on SNS choice. Thus, our hypothesis 4 was again rejected. Our results still highlighted that the norms of valence expression were more positive for Instagram than for Twitter (Waterloo et al., Citation2018). Further investigation is needed to understand this phenomenon.

SNSs usage

We first performed a binomial logistic regression showing that the frequencies of Instagram and Twitter use did not have a significant impact on SNS choice (p > .05); only the message valence had one, B = −2.76, Wald χ2(1) = 28.323, p < .001, OR = .06, 95% IC OR [.023, .174].

As pre-registered, we then performed a mediation analysis with 5000 bootstrap samples to examine if the frequencies of Instagram and Twitter use can mediate the effect of the message valence on the SNS choice. As expected, they did not mediate the relationship: direct effect was significant (95% CI [1.75, 3.78]), while indirect effects (95% CI [−.11, .21] for Instagram, 95% CI [−.17, .13] for Twitter) and total effect (95% CI [−19, .24]) were non-significant.

Finally, we found a significant association between the number of SNSs used in one week and the perception of Instagram’s and Twitter’s norms of emotional expression (r = −.31, p < .001 for Instagram; r = −.206, p < .038 for Twitter): the more SNSs people use, the more they perceived positively emotional expression of Twitter and Instagram.

Although hypothesis 6 cannot be confirmed or refuted with the tests performed, the results highlighted that using a SNS regularly did not lead participants to choose it. Furthermore, it appears that using many SNSs was associated with a more positive perception of Instagram and Twitter’s norms of emotional expression. In other words, individuals who are heavy users may get used to how people express themselves on SNSs and therefore find the content more positive.

This experiment, as well as experiment 1a, had some limitations. The first concerns the samples, which were mostly women. This is an important aspect because although the gender distribution on Instagram is almost balanced, Twitter users are over 70% men (Bouissiere, Citation2021). Another limitation deals with the experimental material. Although the images and the texts were pre-tested, the colors of the positive image appeared altered. Given that Instagram is often portrayed as allowing its users to edit their photos, it is impossible to know the extent to which this feature influenced respondents. Finally, emotion cannot be reduced to a simple dichotomy (Colombetti, Citation2005). As explained in the introduction, emotion is often considered through the dimensions of valence and arousal (Russell, Citation1980). The investigation of emotional valence is consistent with the literature, but little is known about the impact of emotional arousal on SNSs’ emotional expression (Choi & Toma, Citation2014).

Experiments 2a and 2b: Valence’s and Arousal’s Impacts on Instagram and Twitter

Experiments 2a and 2b aimed at replicating 1a and 1b’s experiments by considering emotional arousal. Participants were presented with a message – text and image – and asked on which SNS they were most likely to be published (Twitter vs. Instagram). We manipulated the emotional valence (Positive vs. Negative) as well as the emotional arousal (High vs. Low) of this message. Since experiments 1a and 1b did not show a significant effect of image position on SNS choice, the order of appearance of the text and the image was counterbalanced, but not manipulated.

As shown in , several hypotheses were pre-registered for each of the experiments.

Table 2. Pre-registered hypotheses for experiments 2a and 2b.

Experiment 2a

Method

Participants and procedure

The experiment was conducted during a University Technology Degree online lecture course. Based on resources, we expected a sample size of 120. However, the G*Power software did not allow to perform a sensitivity analysis for a log-linear analysis (pre-registered principal analysis). To our knowledge, no other software, application, or code allowed us to perform it at the time we conducted our study. Following the same procedure as experiment 1b, 137 students voluntarily consented to participate, from which were removed those who did not fully complete the study and who failed the manipulation check.Footnote7 Data collection took place from November 17 to 19, 2020. The final sample comprises 102 participants.

Concerning the socio-demographic characteristics, the sample is composed of 61 women and 41 men (Mage = 18.15, SDage = .64). All participants were students, 80 had both an Instagram and a Twitter accounts, and 22 had only one of them or none.

Materials

As in experiments 1a and 1b, participants were presented with a text and an image. To improve stimuli quality, the images were taken from the Open Affective Standardized Image Set (OASIS; Kurdi et al., Citation2017). All stimuli in this database have already been rated in terms of valence and arousal. We therefore chose four landscape images in accordance with our experimental conditions, to which we associated a text about nature. We then pre-tested the valence and the arousal of the four pairs (image and text) on 28 psychology master’s students (20 women and 8 men; Mage = 25.89, SDage = 8.34). Pretest participants had to rate the valence on a 7-point scale (0 = Very negative; 7 = Very positive) and the arousal on the 7-point scale (0 = Very low; 7 = Very high). Paired sample t-tests were finally conducted (p < .05). The stimuli are available on the OSF (see “Transparency and Openness” section).

Measures

The measures relating to the number of SNSs used per week, Instagram and Twitter accounts, frequencies of Instagram and Twitter use, SNS choice (the dependent variable), and sociodemographic questions were identical to those in experiment 1b.

To measure norms of emotional expression on Twitter and Instagram, we used the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM; Bradley & Lang, Citation1994). More precisely, we relied on the valence scale and the arousal scales. For each scale, participants were asked, “In your opinion, which of these pictures is the most representative of a person about to post a message on [Twitter][Instagram]?.”

Finally, to check if the valence and arousal variables were successfully manipulated, participants responded to two control questions about the message they saw: one for the valence (1 = Very negative; 7 = Very positive), and the other for the arousal (1 = Very low; 7 = Very high).

Results and discussion

Valence’s and arousal’s impact on Instagram and twitter choice

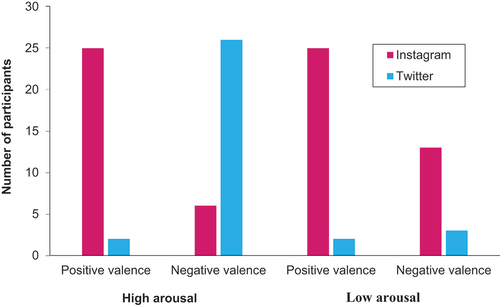

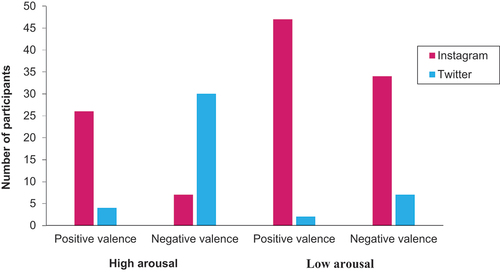

We ran a binomial logistic regressionFootnote8 on SNS choice for emotional valence and arousal. The choice of Instagram or Twitter was explained by the message valence (B = −3.99, Wald χ2(1) = 21.39, p < .001, OR = .018, 95% CI OR [.003, .100]), the message arousal (B = −2.93, Wald χ2(1) = 13.98, p < .001, OR = .053, 95% CI OR [.011, .248]), and the interaction between them (B = 2.93, Wald χ2(1) = 5.07, p < .05, OR = 18.78, 95% CI OR [1.46, 240.97]). As illustrated by , when the valence was positive, the odds of a participant choosing Instagram increased by a factor of (1/.018) 55.56, and when the arousal was low, the odds of a participant choosing Instagram increased by a factor of (1/.053) 18.87. Finally, when the valence was negative and the arousal was high, the odds of a participant choosing Twitter increased by a factor of 18.78.

As pre-registered, we break down this effect by conducting two separate χ2 tests. For the emotional valence, the continuity corrected χ2 test was significant, χ2(1) = 30.25, p < .000, Phi = .57. For the emotional arousal, it was also significant, χ2(1) = 13.00, p < .000, Phi = −.38.

To our knowledge, this experiment is one of the few to study the expression of emotional arousal on SNSs. This allowed us to refine the results of experiments 1a and 1b with new experimental stimuli and within a gender-balanced sample. Positively valenced messages were most often associated with Instagram (hypothesis 2 confirmed), but negative messages were not systematically associated with Twitter (hypothesis 1 partially confirmed). When arousal was low, regardless of valence, Instagram was chosen most often. However, when arousal was high and valence negative, Twitter was preferred. In other words, negative emotions such as boredom or lassitude seem to be better suited to Instagram, whereas negative emotions such as anger or distress seem to be better suited to Twitter. These results help understand why Twitter is often considered an ideal SNS for collective action (Masciantonio, Schumann, et al., Citation2021). Collective action requires confronting a situation of injustice, that is, expressing negative emotions with high arousal. These results also showed that negative emotions are not absent from Instagram, but that their arousal is preferably low.

Social norms of emotional expression

The valence norm was more positive for Instagram (M = 2.35, SD = 1.49) than for Twitter (M = 4.25, SD = 2.21), t (101) = −6.98, p < .000, Cohen’s d = −.69. However, there was no significant difference between the arousal norm on Instagram (M = 4.46, SD = 2.22) and on Twitter (M = 4.46, SD = 2.89), t(101) = 0.00, p = 1.0.

Following our pre-registration, we conducted a mediation analysis with 5000 bootstrap samples to test the association between message valence and SNS choice through the valence norm (Hayes, Citation2017). Direct effect was significant (95% CI [1.75, 4.10]), while indirect effects (95% CI [−.15, .20] for Instagram, 95% CI [−.09, .28] for Twitter) and total effect (95% CI [−16, .34]) were non-significant. Mediation analyses for arousal norms showed similar results: direct effect (95% CI [−2.96, −.83]), indirect effects (95% CI [−.27, .10] for Instagram, 95% CI [−.19, .17] for Twitter) and total effect (95% CI [−.35, .19]).

As in previous experiments, valence norms of expression were more positive for Instagram than Twitter (hypothesis 3 confirmed). However, we did not find any significant differences between the arousal norms of expression on the two platforms. If we consider that arousal norms underlie the effects of message arousal on the choice of Instagram and Twitter, this result is surprising. However, we again did not find mediating effects; this result could therefore suggest that norms are one factor among others to explain the choice of SNSs. We need to explore qualitatively the participants’ choices to deepen the reflections.

SNSs usage

We carried a binomial logistic regression on SNS choice for message valence, message arousal, having SNSs accounts, and all possible interactions. The only significant effects were for the message valence (B = 4.75, Wald χ2(1) = 16.79, p < .001, OR = 115.5, 95% CI OR [11.92, 1119.56]), and the interaction between the valence and the arousal (B = −3.81, Wald χ2(1) = 6.23, p < .05, OR = .022, 95% CI OR [.001, .441]).

We also ran a binomial logistic regression showing that the frequencies of Instagram and Twitter use did not have a significant impact on SNS choice (p > .05); only message valence (B = −2.76, Wald χ2(1) = 28.323, p < .001, OR = .06, 95% IC OR [.023, .174]) and message arousal (B = −2.108, Wald χ2(1) = 10.931, p < .001, OR = .121, 95% IC OR [.035, .426]) had one. Following our pre-registration, we did mediation analyses with 5000 bootstrap samples. The association between message valence and SNS choice through Twitter’s and Instagram’s frequencies of use was not significant: direct effect (95% CI [1.81, 4.19]), indirect effects (95% CI [−.12, .12] for Instagram, 95% CI [−.19, .21] for Twitter) and total effect (95% CI [−.22, .23]). The same was for message arousal: direct effect (95% CI [−2.98, −.85]), indirect effects (95% CI [−.15, .09] for Instagram, 95% CI [−.23, .10] for Twitter) and total effect (95% CI [−.27, .13]).

Finally, there was no significant relationship between the number of SNSs used in one week and the perception of Instagram’s and Twitter’s emotional norms of expression (p > .05).

These results confirmed the previous ones: SNS choice could not be significantly explained either by the frequencies of Instagram and Twitter use or by having an Instagram and a Twitter account. But in contrast to experiment 1b, the number of SNSs used per week was not associated with the perception of emotional expression norms. Although the sample in experiment 2a consists of students like 1b, the sample size was relatively small.

Experiment 2b

The purpose of experiment 2b was to replicate experiment 2a using a larger sample. Furthermore, it also aims to qualitatively investigate what leads participants to choose Instagram or Twitter: What is the role of social context in relation to other factors?

Method

Participants and procedure

Data collection took place on January 25, 2021 on the Prolific platform: participants received a small amount of money for their participation. We conducted a power analysis on G*Power 3.1 for a binomial logistic regression. We calculated the parameters using the results of Study 2a; because sample estimates may be overestimated, we used a small alpha level (.01) and a high desired threshold of power (.99). The required sample size was 161 participants (Faul et al., Citation2007). Following the same procedure as the experiment 2a, 210 persons voluntarily consented to participate, from which were removed those who did not fully complete the study and who failed the manipulation check.Footnote9 The final sample comprises 157 participants.

The sample consisted of 69 women, 84 men and 4 persons with another gender identity (Mage = 28.59, SDage = 8.85). Concerning their life situation, 82 were employed, 52 were students, 15 were unemployed, one was homemaker and 7 were in another situation. Finally, 108 had both an Instagram and a Twitter accounts, and 49 had only one of them or none.

Materials

Again, two variables were manipulated: message valence (Positive vs. Negative) and message arousal (High vs. Low). The experimental material was the same as in experiment 2a.

Measures

Having an Instagram and Twitter accounts, the frequency of use of these SNSs, SNS choice (the dependent variable), number of SNSs used in one week, manipulation check, and sociodemographic questions were measured in the same way as in experiment 2a.

Rather than measuring social norms, after choosing Instagram or Twitter, participants could respond to an open question, “In your words, can you explain what motivated your choice in the previous question?.”

Results and discussion

Valence’s and arousal’s impact on Instagram and twitter choice

We ran a binomial logistic regression to investigate how the choice of Instagram or Twitter could be predicted by the message valence, the message arousal, and the interaction between them. The SNS choice was explained by the message valence (B = −3.33, Wald χ2(1) = 23.82, p < .001, OR = 0.036, 95% CI OR [.009, .137]), and the message arousal (B = −3.04, Wald χ2(1) = 26.45, p < .001, OR = .05, 95% CI OR [.015, .153]). As shown in the , when the valence was positive the odds of a participant choosing Instagram increased by a factor of (1/.036) 27.78, and when the arousal was low the odds of a participant choosing Instagram increased by a factor of (1/.05) 20.

As pre-registered, the continuity corrected χ2 test was significant for SNS choice and message valence, χ2(1) = 29.36, p < .000, Phi = .45. It was also significant for SNS choice and message arousal, χ2(1) = 30.05, p < .000, Phi = −.45.

Even with a larger sample, the results were consistent with those of experiment 2a. When the message was positive, Instagram was chosen more often than Twitter (hypothesis 1 confirmed). Instagram was also more often chosen when the message was negative with low arousal. Similar to experiment 2a, when valence was negative and arousal was high, Twitter was chosen more often than Instagram. Although our analyses demonstrated the main effects of emotional valence and arousal, we did not find an interaction effect between these two variables. Our hypotheses 4 and 5 were partially confirmed. These results further emphasize that the emotional content of a message – valence and arousal – affects the choice of SNSs.

SNSs usage

We examined the impact of having an Instagram and a Twitter accounts, the binomial logistic regression demonstrated that only the message valence (B = −3.73, Wald χ2(1) = 17.46, p < .001, OR = 0.024, 95% CI OR [.004, .138]), and the message arousal (B = −3.23, Wald χ2(1) = 19.37, p < .001, OR = .04, 95% CI OR [.009, .167]) had a significant effect on the SNS choice.

Similarly, frequencies of Instagram and Twitter use had no effect on SNS choice, only message valence (B = 2.793, Wald χ2(1) = 25.190, p < .001, OR = 16.336, 95% IC OR [5.488, 48.628]) and message arousal (B = −2.656, Wald χ2(1) = 26.692, p < .000, OR = .070, 95% IC OR [.026, .192]) did. Mediation analyses showed that frequencies of Instagram and Twitter did not mediate the relationship between message valence and SNS choice: direct effect (95% CI [1.45, 3.34]), indirect effects (95% CI [−.10, .08] for Instagram, 95% CI [−.08, .11] for Twitter) and total effect (95% CI [−.12, .13]). The same was for message arousal: direct effect (95% CI [−3.11, −1.41]), indirect effects (95% CI [−.08, .07] for Instagram, 95% CI [−.06, .15] for Twitter) and total effect (95% CI [−.10, .16]).

As in the previous experiments, having Instagram and Twitter accounts, as well as their frequencies of use, did not have a significant effect on SNS choice.

Qualitative investigation

Finally, we qualitatively explored the participants’ choices. The responses to the open-ended question, “In your words, can you explain what motivated your choice in the previous question?” were analyzed through a thematic analysis on NVivo10 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Citation2020). Two supra-ordinate themes emerged (Bardin, Citation2013), one dealing with Instagram, the other with Twitter.

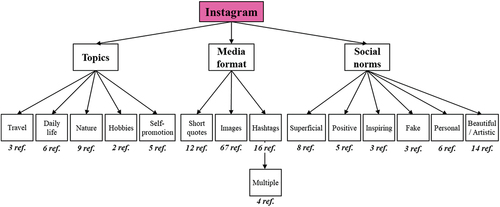

As shown in , participants justified their choice by mentioning three Instagram features. First, they explained that certain topics were more suitable for Instagram, including travel, daily life, nature, self-promotion, and hobbies. These elements coincide with the literature on Instagram users’ motivations (Sheldon & Bryant, Citation2016). Second, the media format focused on the architecture and affordances of Instagram (Bossetta, Citation2018; O’Riordan et al., Citation2016). Participants explained that the platform was more conducive to images, use of multiple hashtags, and short quotes. Finally, they reported norms of expression on the platform. Posts were perceived as inspiring, positive, personal, beautiful, and artistic, but also as superficial and fake. For example, one participant explained that “Instagram is more a social network of perfection, where everything pictured has to look pretty” and another one that “I feel that Instagram is more into positive sharing”.

Figure 6. Diagram of the thematic analysis for Instagram (experiment 2b).

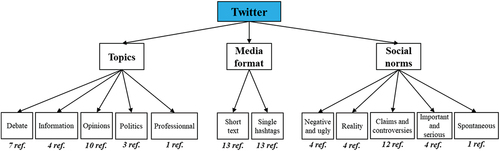

Regarding Twitter (), participants mentioned the same features. The topics seemed to be related to debate, information, opinions, political facts, and professional interactions. Again, they are consistent with the literature on motivations for using Twitter (Johnson & Yang, Citation2009; Park, Citation2013). The format of the media emphasized, as expected, the use of short text and single hashtags (Bossetta, Citation2018). Finally, participants indicated norms of expression on Twitter. The most appropriate posts were perceived as negative, ugly, spontaneous, and related to claims or controversies. Examples of verbatims include, “The mood aspect, people tend to share what’s negative on Twitter,” “especially the fact that it’s ugly,” and “I have this impression that we talk about what’s controversial more often on Twitter than on Instagram.” As a result, Twitter seems to depict important and serious topics, reflecting the reality: “Twitter seems more serious about denouncing problems in society” and “Real and natural images, so Twitter.”

This qualitative approach highlighted that the participants contrasted Instagram and Twitter across three features: architecture, user motivations, and social norms of expression. As we hypothesized (Manikonda et al., Citation2021; Waterloo et al., Citation2018), the most appropriate messages on Instagram were perceived as positive. However, we did not anticipate that they would then be perceived as false and superficial. Conversely, the most appropriate posts on Twitter were perceived as negative, spontaneous, and controversial. Therefore, these results demonstrate that expression on SNSs is not only dependent on the popular topics or the architecture of the platforms, but also on social norms (Tandoc et al., Citation2019). In other words, a mix of these three features leads individuals to choose a SNS to express themselves. In our experiments, we voluntarily used cleaving emotions: positive or negative with high or low arousal; that is why the emotional content had a strong impact on the SNS choice, regardless of the topics or the SNS architecture. The absence of any mediating effects of norms may be explained by methodological factors, such as small sample sizes, but also because norms are interdependent on the architecture and user motivations.

General Discussion

The literature on emotional expression on SNSs is still in its infancy. The aim of this research was to understand how the emotions of a message impact the choice of the SNS used to publish it. Specifically, it focused on two platforms that are often opposed: Instagram and Twitter. This research is one of the first to examine both emotional valence and emotional arousal using four pre-registered experimental studies.

Our investigation goes beyond the vision of Instagram as a positive SNS and Twitter as a negative one. Although Instagram was perceived as more appropriate for positive messages, the platform was also associated with low negative emotions. This result is consistent with the fact that Instagram is sometimes used for sensitive self-disclosure, such as depression (Andalibi et al., Citation2017). Regarding Twitter, the platform was found to be more appropriate for highly negative messages. As previously mentioned, Twitter is often in the spotlight for collective movements, and the platform is very popular in the journalistic world (Lotan et al., Citation2011). In doing so, this research complements and exceeds the existing literature (Jiménez-Zafra et al., Citation2021; Naveed et al., Citation2011; Thelwall et al., Citation2011; Waterloo et al., Citation2018).

In particular, these conclusions provide a new perspective on the social context of SNSs (Boczkowski et al., Citation2018; Tandoc et al., Citation2019). Not all SNSs are conducive to positive self-presentation (Reinecke & Trepte, Citation2014). Some SNSs, such as Twitter, might encourage individuals to express upsetting, frustrating, or annoying events that happen to them. However, we do not mean that individuals use SNSs solely based on the social context. The qualitative analysis emphasized that at least three elements contribute to this phenomenon: SNSs architecture, user motivations, and social norms. Therefore, future studies should continue to investigate how individuals use SNSs, including how they express themselves on these platforms.

The reason why emotional expression on SNSs is so important is because it is crucial for many other research issues. For example, the field of SNSs health effects relies on the positivity bias: while navigating SNSs, individuals are constantly exposed to positive self-presentations, which leads them to an upward social comparison, damaging their well-being (Appel et al., Citation2016; Verduyn et al., Citation2017). This theoretical proposition has been demonstrated many times for SNSs like Facebook (Hanna et al., Citation2017), but it turns out that recent studies point out that Twitter might lead to a decrease in upward social comparison rather than an increase (Masciantonio, Bourguignon, et al., Citation2021). This result could thus be partially explained by the fact that the positivity bias is not adapted to Twitter: individuals are not confronted with an ideal vision of others’ lives, but with a more realistic and negative one. In doing so, they would not engage in upward social comparisons, which could conversely improve their well-being. Future research should not only explore these findings to gain a better understanding of emotional expression on SNSs, but also consider them in broader research on SNSs.

However, there are limitations to this investigation that must be considered. By manipulating SNSs contents, this research offers better internal validity than the existing literature; however these contents cannot reflect the actual experience of SNS users, and this research cannot grant external validity (Appel et al., Citation2016). In addition, emotional valence and arousal are complex to manipulate. Although some scholars have shown an independence between them (Barrett & Russell, Citation1998; Russell, Citation1980), Kuppens et al. (Citation2013) demonstrated that they have a V-shaped relationship. Thus, positive and negative emotions would be accompanied by more arousal. We also manipulated the architecture based on the position of the photos. In doing so, we focused on only one aspect of the architecture, the graphical user interface (GUI); however, there are many other possible features, such as broadcast feed (Bossetta, Citation2018). Finally, participants were asked to choose between two platforms: Instagram and Twitter. As a result, we cannot determine which SNSs they would have chosen if we had given them more options. There are a multitude of other SNSs – Facebook, TikTok, LinkedIn, Pinterest, etc. - each of them has a specific social context. Similarly, individuals continuously alternate between platforms. Our methodology did not capture the phenomenon of platform-swinging (Tandoc et al., Citation2019).

We chose experimental simplicity because we wanted to investigate a new research topic. This experimental simplicity offers many advantages – in terms of controlling the SNS environment, causality of effects, and the possibility of gradually adding variables such as arousal. But in the same way, this experimental simplicity limits the scope of our results. To conduct a more comprehensive examination of emotional expression on SNSs, we recommend that researchers utilize mixed methodologies and broaden their focus to include a greater number of SNSs.

Conclusions

This research explored how the emotions of a message influence individuals’ decisions regarding which social network site use to publish it. Through four experimental studies, the valence and arousal of a message were manipulated to understand their effects on Instagram and Twitter choice. The findings revealed that Instagram was the preferred choice for positive messages and messages with low negative emotions such as boredom or lassitude. In contrast, Twitter was the preferred platform for messages with highly negative emotions such as anger or distress. However, this research does not suggest that social norms alone explain these differences, but rather that there is an interdependence between social network site architecture, user motivations, and social context.

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data, Open Materials and Preregistered. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/VMKXC and https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4B8SD for experiment 1a, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/Z2B4T for experiment 1b, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8P5MS for experiment 2a, and https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BPK83 for experiment 2b.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/VMKXC and https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4B8SD for experiment 1a, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/Z2B4T for experiment 1b, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8P5MS for experiment 2a, and https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BPK83 for experiment 2b.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. For more details, please see: https://gist.github.com/annafergusson/f3c53a7e48b4c6d2ca6fb29320af2533

2. Following our pre-registration, we performed the analyses on the participants who passed the manipulation check. However, we also performed the analyses on all participants to verify that the results are identical, which was the case.

3. For this study, as well as for the next three, the number of participants in each experimental condition is available on OSF: https://osf.io/vmkxc/files/osfstorage/644bd6f840b2c17023e8fa7e

4. We pre-registered a hierarchical log-linear analysis. However, it turned out that binary logistic regression was most appropriate for our analyses (Berger, Citation2017). The results showed the same patterns regardless of the test used.

5. As experiment 1a, we pre-registered a hierarchical log-linear analysis but binary logistic regression was most appropriate. The results showed the same patterns regardless of the test used.

6. Although the results were in line with our hypotheses 3 and 5, being null hypotheses, we can neither confirm nor refute them. To test a null hypothesis, we should have used a Bayesian approach or performed equivalence tests.

7. The analyses carried out on all participants showed the same results.

8. As previously, the results of the pre-registered log-linear analysis and the not pre-registered binary logistic regression were identical.

9. The analyses on all the participants gave similar results as those on the participants who passed the manipulation check. However, as the sample size is larger, for the binomial logistic regression on SNS choice for emotional valence and arousal, the interaction between the message valence and the message arousal was significant (p = .047).

References

- Amichai-Hamburger, Y., (Ed.). (2013). The social net: Understanding our online behavior (2nd). OUP Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199639540.001.0001

- Andalibi, N., Ozturk, P., & Forte, A. (2017). Sensitive self-disclosures, responses, and social support on Instagram: The case of #Depression. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, 1485–1500. https://doi.org/10.1145/2998181.2998243

- Appel, H., Gerlach, A. L., & Crusius, J. (2016). The interplay between Facebook use, social comparison, envy, and depression. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.10.006

- Bardin, L. (2013). L’analyse de contenu [Content Analysis]. Presses Universitaires de France. https://doi.org/10.3917/puf.bard.2013.01

- Barrett, L. F., & Russell, J. A. (1998). Independence and bipolarity in the structure of current affect. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 74(4), 967–984. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.4.967

- Berger, D. (2017). Log-Linear Analysis of Categorical Data. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320505747_Log-linear_Analysis_of_Categorical_Data

- Blank, G., & Lutz, C. (2017). Representativeness of social media in Great Britain: investigating Facebook, LinkedIn, twitter, Pinterest, google+, and instagram. The American Behavioral Scientist, 61(7), 741–756. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764217717559

- Boczkowski, P. J., Matassi, M., & Mitchelstein, E. (2018). How young users deal with multiple platforms: The role of meaning-making in social media repertoires. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(5), 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmy012

- Bossetta, M. (2018). The digital architectures of social media: Comparing political campaigning on Facebook, twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat in the 2016 US election. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 95(2), 471–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699018763307

- Bouissiere, Y. (2021, January 27). Chiffres réseaux sociaux 2021 (2020): Tous les chiffres qui comptent [Social media numbers 2021 (2020): All the numbers that matter] [Proinfluent] https://www.proinfluent.com/chiffres-reseaux-sociaux/

- Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1994). Measuring emotion: The self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 25(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-79169490063-9

- Brosch, T., & Moors, A. (2009). Valence. In D. Sander, & K. R. Scherer (Eds.), The Oxford companion to emotion and the affective sciences (pp. 401–402). Oxford University Press.

- Choi, M., & Toma, C. L. (2014). Social sharing through interpersonal media: Patterns and effects on emotional well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 530–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.026

- Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A., & Reno, R. R. (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct: a Theoretical Refinement and Reevaluation of the Role of Norms in Human Behavior. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 24, pp. 201–234). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-26010860330-5

- Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015–1026. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015

- Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., Vols. 1-2, pp. 151–192). McGraw-Hill.

- Colombetti, G. (2005). Appraising valence. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 12(8–10), 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-005-2138-3

- Dan-Glauser, E. (2019). Le sentiment subjectif. Intégration et représentation centrale consciente des composantes émotionnelles [The subjective feeling. Integration and conscious central representation of emotional components. In D. Sander, & K. R. Scherer (Eds.), Traité de psychologie des émotions (pp. 223–257). Dunod.

- Derks, D., Fischer, A. H., & Bos, A. E. (2008). The role of emotion in computer-mediated communication: A review. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(3), 766–785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2007.04.004

- Ekman, P. (1992). Are there basic emotions?. Psychological Review, 99(3), 550–553. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.99.3.550

- Ellison, N. B., & Boyd, D. (2013). Sociality through social network sites. In W. H. Dutton (Ed.), The oxford handbook of internet studies (pp. 151–172). Oxford University Press.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

- Fergusson, A. (2016). Designing Online Experiments Using Google Forms+ Random Redirect Tool. https://teaching.statistics-is-awesome.org/designing-online-experiments-using-google-forms-random-redirect-tool

- Girandola, F., & Fointiat, V. (2016). Attitudes et comportements: Comprendre et changer [Attitudes and behaviors: Understanding and changing]. Presses universitaires de Grenoble. https://doi.org/10.3917/pug.giran.2016.01

- Griffioen, N., van Rooij, M., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., & Granic, I. (2020). Toward Improved Methods in Social Media Research. Technology, Mind, and Behavior, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1037/tmb0000005

- Hanna, E., Ward, L. M., Seabrook, R. C., Jerald, M., Reed, L., Giaccardi, S., & Lippman, J. R. (2017). Contributions of social comparison and self-objectification in mediating associations between Facebook use and emergent adults’ psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 20(3), 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0247

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

- JASP Team. (2020). JASP (Version 0.12.2) [Computer software].

- Jiménez-Zafra, S. M., Sáez-Castillo, A. J., Conde Sánchez, A., & Martín-Valdivia, M. T. (2021). How do sentiments affect virality on Twitter? Royal Society Open Science, 8(4), 201756. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.201756

- Johnson, P. R., & Yang, S. (2009). Uses and gratifications of Twitter: An examination of user motives and satisfaction of Twitter use. Presented at the Communication Technology Division of the Annual Convention of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication in Boston, Massachusetts, 2009 August.

- Kuppens, P., Tuerlinckx, F., Russell, J. A., & Barrett, L. F. (2013). The relation between valence and arousal in subjective experience. Psychological Bulletin, 139(4), 917–940. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030811

- Kurdi, B., Lozano, S., & Banaji, M. R. (2017). Introducing the open affective standardized image set (OASIS). Behavior Research Methods, 49(2), 457–470. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0715-3

- Lapinski, M. K., Zhuang, J., Koh, H., & Shi, J. (2017). Descriptive norms and involvement in health and environmental behaviors. Communication Research, 44(3), 367–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215605153

- Lotan, G., Graeff, E., Ananny, M., Gaffney, D., Pearce, I., & Boyd, D. (2011). The Arab spring| the revolutions were tweeted: Information flows during the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. International Journal of Communication, 5, 31.

- Manikonda, L., Meduri, V. V., & Kambhampati, S. (2021). Tweeting the mind and instagramming the heart: Exploring differentiated content sharing on social media. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 10(1), 639–642. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v10i1.14819

- Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810365313

- Masciantonio, A., Bourguignon, D., Bouchat, P., Balty, M., Rimé, B., & Guidi, B. (2021). Don’t put all social network sites in one basket: Facebook, Instagram, twitter, TikTok, and their relations with well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE, 16(3), e0248384. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248384

- Masciantonio, A., Schumann, S., & Bourguignon, D. (2021). Sexual and gender-based violence: To tweet or not to tweet? Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 15(3). Article 4. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2021-3-4.

- McLaughlin, C., & Vitak, J. (2012). Norm evolution and violation on Facebook. New Media & Society, 14(2), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811412712

- Meier, A., & Reinecke, L. (2021). Computer-Mediated Communication, Social Media, and Mental Health: A Conceptual and Empirical Meta-Review. Communication Research, 48(8), 1182–1209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220958224

- Nadkarni, A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2012). Why do people use Facebook?. Personality & Individual Differences, 52(3), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.007

- Naveed, N., Gottron, T., Kunegis, J., & Alhadi, A. C. (2011). Bad news travel fast: A content-based analysis of interestingness on twitter. Proceedings of the 3rd International Web Science Conference, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1145/2527031.2527052

- Nick, E. A., Cole, D. A., Cho, S.-J., Smith, D. K., Carter, T. G., & Zelkowitz, R. L. (2018). The online social support scale: Measure development and validation. Psychological Assessment, 30(9), 1127–1143. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000558

- O’Riordan, S., Feller, J., & Nagle, T. (2016). A categorisation framework for a feature-level analysis of social network sites. Journal of Decision Systems, 25(3), 244–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/12460125.2016.1187548

- Park, C. S. (2013). Does twitter motivate involvement in politics? Tweeting, opinion leadership, and political engagement. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1641–1648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.01.044

- Pittman, M., & Reich, B. (2016). Social media and loneliness: Why an Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand Twitter words. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.084

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020). NVivo (released in March. 2020). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Quertemont, E. How to statistically show the absence of an effect. (2011). Psychologica Belgica, 51(2), 109. Article 2. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb-51-2-109

- Reinecke, L., & Trepte, S. (2014). Authenticity and well-being on social network sites: A two-wave longitudinal study on the effects of online authenticity and the positivity bias in SNS communication. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.030

- Rimé, B., Bouchat, P., Paquot, L., & Giglio, L. (2020). Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and social outcomes of the social sharing of emotion. Current Opinion in Psychology, 31, 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.08.024

- Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 39(6), 1161–1178. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077714

- Sander, D., & Scherer, K. R. (2019). La psychologie des émotions: Survol des théories et débats essentiels [The psychology of emotions: An overview of key theories and debates. In D. Sander, & K. R. Scherer (Eds.), Traité de psychologie des émotions (pp. 11–50). Dunod.

- Scherer, K. R. (1982). Emotion as a process: Function, origin and regulation. Social Science Information, 21(4–5), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901882021004004

- Sheldon, P., & Bryant, K. (2016). Instagram: Motives for its use and relationship to narcissism and contextual age. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.059

- Sundar, S. S. (2015). The handbook of the psychology of communication technology. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118426456

- Tandoc, E. C., Jr., Lou, C., & Min, V. L. H. (2019). Platform-swinging in a poly-social-media context: How and why users navigate multiple social media platforms. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 24(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmy022

- Thelwall, M., Buckley, K., & Paltoglou, G. (2011). Sentiment in twitter events. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(2), 406–418. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21462

- Thelwall, M., Wilkinson, D., & Uppal, S. (2010). Data mining emotion in social network communication: Gender differences in MySpace. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(1), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21180

- Tournois, J., Mesnil, F., & Kop, J.-L. (2000). Autoduperie et héteroduperie: Un instrument de mesure de la désirabilité sociale [Self-deception and other-deception: A social desirability questionnaire]. European Review of Applied Psychology / Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée, 50(1), 219–233.

- Tufekci, Z. (2014). Big questions for social media big data: Representativeness, validity and other methodological pitfalls. Eighth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, 14, 105–514.

- Vanden Abeele, M. M. P. (2021). Digital Wellbeing as a Dynamic Construct. Communication Theory, 31(4), 932–955. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtaa024

- van Dijck, J. (2013). ‘You have one identity’: Performing the self on Facebook and LinkedIn. Media Culture & Society, 35(2), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443712468605

- Van Zomeren, M. (2013). Four Core Social-Psychological Motivations to Undertake Collective Action. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(6), 378–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12031

- Van Zomeren, M., Leach, C. W., & Spears, R. (2012). Protesters as “passionate economists” a dynamic dual pathway model of approach coping with collective disadvantage. Personality & Social Psychology Review, 16(2), 180–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311430835

- Verduyn, P., Ybarra, O., Résibois, M., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2017). Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11(1), 274–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12033

- Walther, J. B. (1996). Computer-mediated communication: Impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research, 23(1), 3–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365096023001001

- Waterloo, S. F., Baumgartner, S. E., Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2018). Norms of online expressions of emotion: comparing Facebook, twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp. New Media & Society, 20(5), 1813–1831. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817707349