Professor Lawrence C. Bliss, the prominent authority on arctic and alpine ecosystems, died on 7 July 2019 in Redmond, Washington. He was a student of the doyen of alpine ecology, Prof. Dwight Billings at Duke University. The ecological sciences lost one of its most recognized cold-regions ecologists.

Fifty years ago, in early June 1970, when I was just completing my undergraduate program in biology at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada, I received a long-distance call. Prof. Lawrence C. Bliss, at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, to whom I had applied as his potential graduate student, asked me whether I would be interested in joining a research expedition to the Arctic that he had just organized. It was to be a study of a high arctic oasis in Truelove Lowland on Devon Island, registered as a “Tundra Biome Project.” It was also to become an integral part of the International Biology Program, with which I was already familiar.

Surprised by the friendly invitation, I answered that, indeed, I would be greatly interested. “In that case I will expect you here at least a week before our departure to the North on June 23.” This was short notice! In Edmonton, I met Larry, my future thesis advisor, and Gweneth, his wife, who offered to let me stay in their home until our departure for the field.

Born in 1929, Larry and I were the same age but had very different life histories. Prior to my coming to Canada, Larry, a U.S. citizen, was already an established alpine ecologist and professor at the University of Illinois. In 1968 he accepted a position at the University of Alberta in Edmonton and prepared to start research in the Canadian Arctic. That year, I arrived in Canada as a political ex-convict from the former communist Czechoslovakia with 4 years of university credits but without a degree. In Canada I was granted an exception, achieving a B.Sc. degree after a single year of residency at the University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario.

Thus, in the late spring of 1970 in Edmonton, with Larry’s blessing, three of us, his new students, boarded a cargo jet of Pacific Western Airlines for a long flight to Resolute Bay, Northwest Territories. The cavernous plane had a few seats installed for us, the freeloaders—an example of Larry’s ingenuity to save his grant money and get as many students to the Arctic free of charge!

Resolute Bay has been for decades the hub for research parties aiming for various localities within the subcontinent of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Here we boarded a Twin Otter plane and after another two-and-a-half-hour flight we landed in Truelove Lowland at Devon Island, 75° N, at an old base camp of the Arctic Institute of North America. At the time of our arrival, a cohort of around fifty graduate students of diverse disciplines and their field assistants populated the camp. Several of them were Larry Bliss people, my new colleagues. Thus, for me, a lifelong Arctic adventure and association with my new supervisor began. I spent four summers at the Truelove “oasis,” studying plant succession on a series of marine beach ridges, submerged during the Ice Age and then uplifted from the sea during the last 5,000 years.

In the spring of 1972 I was offered a position as a plant ecologist at the University of Toronto. Yet, with Larry, we continued our fieldwork on the polar landscapes of the Queen Elizabeth Islands. From Resolute, we were flown to our island of destination, dropped on the rugged terrain with our personal gear, a tent, food, radio, and a rifle. We moved around on foot. Once, we had to cross a fast-running glacial stream. Being taller, I carried Larry across on my back. On some expeditions, Larry’s teenage son Dwight accompanied us as a field assistant. Our collaboration continued on the international scene in the International Biology Program as well as the Man and the Biosphere gatherings of the 1990s.

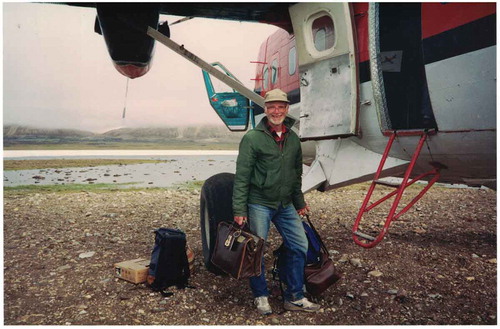

Figure 2. Professor L. C. Bliss boarding the Twin Otter plane at the Truelove Lowland, Devon Island, Canada (July 1993). Photo courtesy of Karen Demaree, daughter of Lawrence C. Bliss.

Larry was a man with eminent leadership skills and a big heart. When I defended my doctoral thesis, he invited me for a lunch in the faculty club. We sat down and he said: “Josef, from now on you will call me Larry!” “I can’t do it,” was my instant reply. “In that case, I will have to call you Dr. Svoboda.”

Prof. Bliss’s contribution to arctic and alpine science is solid, lasting, and exemplary. The ecological sciences lost one of its most recognized cold-regions professionals, whose global footprints continue to multiply through the international cohort of his seventy-three master’s and doctoral graduates.

He was deeply concerned about nature and fairness in society. Whoever approached him was welcomed by his gentle smile. I respected him highly.