THE ISSUE

Most scientists expect that hurricanes will become more dangerous as greenhouse gases build up in the atmosphere, but what does the faraway Arctic have to do with tropical storms? A lot, it turns out.

WHY IT MATTERS

Major hurricanes can be deadly and ruin the livelihoods of millions, while causing billions of dollars in damages and threatening lives. Evidence is mounting that the rapidly changing Arctic is affecting tropical storms, but more research is needed to determine how and how much. The devastating hurricane seasons of recent years highlight the urgency of such research.

STATE OF KNOWLEDGE

Scientists have long expected that hurricanes would strengthen in a warming world – it’s basic physics – and those expectations have become realityCitation1. Warmer air contains more energy, and tropical storms can turn that energy into stronger winds. More important is that most of the heat trapped by greenhouse gases ends up in the ocean. Additional heat in the water and air also leads to more evaporation, and that extra water vapor fuels storms as it condenses into clouds and releases heat into the air. More available moisture also means heavier rainfall. And because warmer ocean water expands, it contributes nearly half of the observed rise in global sea level. A hurricane’s storm surge and destructive waves ride on an increasingly higher sea, exacerbating the destruction and moving it farther inland. Changes in wind patterns are also expected as the globe continues to warm, including changes that may be causing tropical storms to move more slowly, perhaps even stall more frequentlyCitation2. Predicting these irregular storm motions is more challenging, leading to lower confidence in public hazard warnings.

The Arctic’s role in this story is as an amplifier. Arctic sea ice – frozen seawater that floats on the Arctic Ocean – has been disappearing at an alarming and unprecedented rate during recent decades: half of its areal coverage during summer and three-quarters of its volume have been lost in only 40 years. There is no plausible explanation for this change other than human-caused global warming. Because ice and snow are white, they reflect back to space most of the incoming solar energy so it never enters the Earth’s climate system. Losing those bright surfaces means the planet gains more energy. Increasing the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere by itself warms the Earth – just like putting an extra blanket on your bed. The ongoing losses of sea ice and spring snowcover on high-latitude land areas mean that the globe absorbs a larger fraction of the sun’s heat, amplifying the warming caused by that extra blanket by 25–40%Citation3. Bottom line: Arctic ice loss is responsible for additional ocean warming, which provides more fuel for storms and faster sea-level rise.

WHERE THE RESEARCH IS HEADED

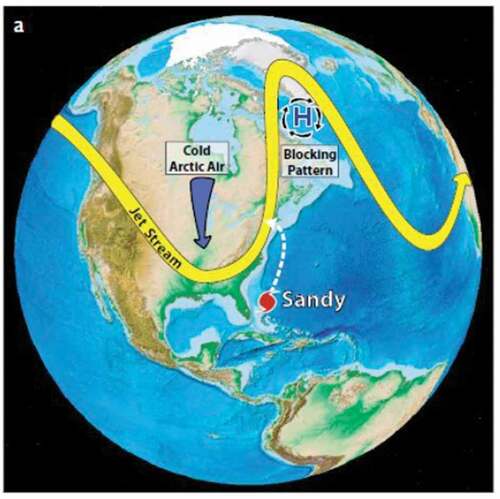

Hurricane Sandy’s unusual left turn into New Jersey in late October 2012 and Hurricane Harvey’s stagnation over Houston in 2017 causing a catastrophic deluge of rainfall are just two recent examples of unruly tropical storms. Rapid Arctic warming may favor so-called “blocking highs” in the North Atlantic – large northward swings in the jet stream that can form clockwise eddies in the flow that prevent weather systems from progressing eastward. A persistent block was in place near Newfoundland just as Sandy tracked up the U.S. east coast in late October 2012 (). The strong easterly (from the east) winds south of the block sent the storm on its unusual left hook into the mid-Atlantic states. Some evidence suggests these types of blocks have become more frequent in recent decades, especially in autumn, but the Arctic’s role in this observed change is far from settledCitation4. Recent model-based studies, such as highlighted in the news article by P. Voosen in Science (14 May 2021, see supplemental material), have cast doubt on the strength of the Arctic’s effects on midlatitude weather. Their approach of averaging over large areas and time periods, however, obscures possible impacts on weather regimes and extreme events.

Figure 1. Atmospheric conditions during Hurricane Sandy’s transit along the eastern seaboard of the United States, including the invasion of cold Arctic air into the middle latitudes of North America and the high-pressure blocking pattern in the northwest AtlanticCitation6.

Another possible influence of Arctic warming on tropical storms has emerged in recent studies: slowing of the winds that determine their pathsCitation2. These steering winds are typically located between 3 and 5 kilometers (1.8 to 3 miles) high. The rapid loss of spring snowcover on northern areas of Eurasia and North America may increase the likelihood of slower summertime steering winds and stationary jet-stream waves (like the one shown in )Citation5, which may cause unusual storm paths. Understanding changes in the frequency, location, and strength of blocking highs and jet-stream waves, as well as the roles played by the rapidly warming Arctic, are “hot topics” in climate change research.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (178.9 KB)Supplementary material

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Additional information

Funding

Key references

- Duan, L., L. Cao, and K. Caldeira. 2019. Estimating contributions of sea ice and land snow to climate feedback. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 124:199–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JD029093.

- Greene, C. H., J. A. Francis, and B. C. Monger. 2013. Superstorm Sandy: A series of unfortunate events? Oceanography 26 (1):8–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2013.11.

- Knutson, T. R., M. V. Chung, G. Vecchi, J. Sun, T.-L. Hsieh, and A. J. P. Smith. 2021. ScienceBrief review: Climate change is probably increasing the intensity of tropical cyclones. In Critical issues in climate change science, eds. C. Le Quéré, P. Liss, and P. Forster. doi:https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4570334.

- Kossin, J. P. 2018. A global slowdown of tropical-cyclone translation speed. Nature 558:104–07. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0158-3.

- Mann, M. E., S. Rahmstorf, K. Kornhuber, B. A. Steinman, S. K. Miller, and D. Coumou. 2017. Influence of anthropogenic climate change on planetary wave resonance and extreme weather events. Nature Scientific Reports 7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45242

- Woolings, T., D. Barriopedro, J. Methven, S.-W. Son, O. Martius, B. Harvey, J. Sillmann, A. R. Lupo, and S. Seneviratne. 2018. Blocking and its response to climate change. Current Climate Change Reports 4 (3):287–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-018-0108-z.