ABSTRACT

There has been growing complexity in the study of environmental regulatory governance. In terms of regulatory approaches, the focus of national styles has gradually shifted to the local level, down to street-level regulators. As for compliance strategies, regulated entities, particularly enterprises, have moved their strategies from the evasion-compliance dichotomy to more progressive ones that are beyond compliance. As environmental watchdogs on behalf of civil society, ENGOs, particularly those in developing and non-democratic political settings, have increasingly found more space for strategizing their active efforts to monitor enforcement agencies and polluting enterprises in the regulatory process. The spilling of regulatory regimes into developing countries has led to an urgent need for regulatory studies in such nations, with a call for new theoretical formulations that are capable of explaining regulatory governance in those countries. Research methodologies adopted have become increasingly sophisticated, moving from using a single method to using mixed methods by integrating qualitative and quantitative ones, with longitudinal studies and panel data analysis as the recent trends. This study aspires to perform a critical review of the existing body of literature on environmental regulatory governance in these major aspects as the basis for a research agenda setting.

Introduction

Environmental regulation has quickly emerged as a major focus in environmental protection research in response to intensified and organized efforts among nations in the adoption of environmental law as the dominant regulatory instrument to cope with rapidly deteriorating environmental degradation. This degradation and a deepening ecological crisis are a result of the under-regulated but expanding and damaging environmental footprint of industrial activities since the 1960s. Since then, regulatory governance has been growing in complexity due to rapid diffusion of the environmental regulatory regime from industrialized economies to developing countries, and to the ever-expanding scope of regulation in multiple environmental sectors for pollution control and ecological conservation.

In terms of regulatory approaches, the focus on examining national styles of environmental regulation has gradually shifted to a focus on the local level, down to street-level regulators. Together with the emergence of progressive ideas about the co-creation of value in regulatory governance, more complexity has been added to existing dialogues between legalistic and cooperative/voluntary paradigms. In respect to strategies for regulatory compliance, regulated entities, particularly industrial enterprises, have moved from a preoccupation with the choice between compliance and evasion to considering compliance as part of a broader sustainability strategy for gaining competitive advantage and achieving business innovation. Serving as environmental watchdog for civil society, ENGOs (environmental non-governmental organizations), particularly those in developing and non-democratic political settings, have increasingly found more space in the environmental regulatory community for strategizing their active monitoring efforts on enforcement agencies and polluting enterprises in order to make the regulatory process more stringent. As more developing and emerging countries have adopted their own regulatory regimes under diverse national circumstances and the immediate threats of climate change and industrial pollution, new theoretical frameworks are needed to account for how cross-national variations affect compelling and emerging issues in environmental regulatory governance.

New sectors (e.g. dumping in outer space, renewable energies, environmental information disclosure, and green production technologies) have increased the complexity of environmental regulation by creating problems distinctly different from those in the traditional regulatory domains. Within the traditional domains (e.g. water, air, and solid waste), changes are occurring because, for example, of the rise of new green technologies and social media. As the pressures of environmental sustainability grow and lead to the establishment of global regulatory regimes, most notably the joint effort in the international community to fight global warming, regulatory norms in different parts of the world will need to be revised accordingly. Concurrent with the dynamic development in the enrichment of environmental regulatory governance research is the increasing sophistication in the research methodology adopted, moving from using single-method to mixed-method studies by integrating both qualitative and quantitative data, with longitudinal studies and panel data analysis as the recent trends. These scholarly efforts improve the integrity of the data collected, increase the credibility and validity of the analyses, and generate original and ground-breaking findings. All these developments are generating academic excitement and resulting in revisions to research agendas on environmental regulatory governance in order to accommodate a greater demand for both theoretical advancement and empirical-based problem-solving. In short, the growing complexity of environmental regulatory research owes much to the prevalence of ‘environmental regulation in the real-world environmental policy and practice’ that as underlined by van de Heijden in another article in this special issue. Our review makes a joint effort with his piece to expand regulatory scholarship in general and to engage greater JEPP scholarship in environmental regulation in particular.

This paper performs a thorough review of the existing body of literature in these major aspects as a basis for research agenda setting. It will start with the conceptualization of environmental regulatory governance research in its complexity, followed by a close examination of the five aspects of complexity. The review demonstrates that there is growing complexity in various aspects of environmental regulatory research, spanning from government regulation making to corporate responses, from international level to street front lines and EGNOs’ collaborative actions. The growing complexity also demands more sophisticated research methodologies. The review will conclude with a reflection and discussion on setting a possible future research agenda.

Conceptualization of the complexity in environmental regulatory governance research

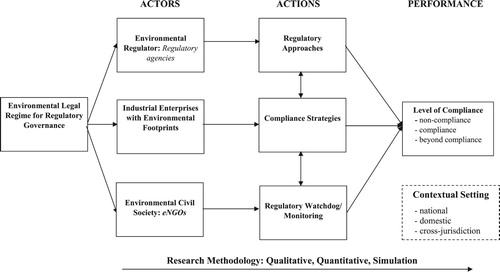

Environmental regulatory research, with legal regulatory control over industrial pollution as the core focus, began with the enforcement actions of regulatory agencies, was extended to include the compliance behaviour of regulated enterprises, and eventually incorporated the monitoring strategies of ENGOs to secure corporate compliance with pollution control and ecological conservation regulations. This research development path is consistent with the theoretical underpinning of collaborative governance literature, which has increasingly conceived that inter-sector collaborations are necessary conditions for effective enforcement and even more progressively to achieve a level beyond compliance (Gunningham, Citation2009). Specifically, the World Bank research group developed the ‘regulatory triangle’ model in 2000, which highlights interactions linking four agents in regulatory compliance: plant, state, community, and market. This model was based on years of research, policy experiments, and direct observations in pollution control in several developing countries in Asia. Regulators in this model serve more like mediators than dictators (Afsah et al., Citation1996). Informed by the ‘regulatory triangle’ model, with collaborative governance as the theoretical support, this review paper adopts a holistic view of the community, which includes regulatory agencies, regulated firms, and civil organizations, in their separate but interactive efforts towards the achievement of regulatory compliance, with added complexities coming from the globalization of the regulatory context and the sophistication of research methodology. The conceptualization of this study is shown in .

Regulatory approaches in environmental regulatory governance

The generic regulatory literature has engaged in intense discussion of the different regulatory approaches, and has developed a continuum to position their variations (Kagan, Citation1989). One tip of the pole posits the traditional legalistic, sanction-oriented, or deterrence approach. On the other end of the pole is a more lenient style, labelled as the conciliatory or accommodative approach, by which regulators try to seek cooperation rather than coercion. Both approaches are embedded in the concept of ‘enforcement style’. In environmental governance research, contemporary discussions have moved from the necessity of government intervention to how this intervention can be designed to achieve optimal effectiveness (Veugelers, Citation2012). The literature has extensively studied the motivations, effectiveness, and respective strengths and weaknesses of each regulatory approach. With governments assuming the leadership, environmental regulatory instruments and the logic behind them have evolved from mandatory regulations to voluntary programmes, from a centralized, top-down system to value co-creating cooperation with localized support. lists the major environmental regulatory approaches discussed in the literature.

Table 1. Regulatory approaches and policy instruments.

A considerable body of literature has engaged in exploring the appropriate approaches that regulatory authorities could leverage, starting from Vogel’s national and agency levels down to May’s and Winter’s local and inspector levels. Attention has been shifted from national-level inquiries to local and street-level ones, as national styles have proved to be too generic and reductionist to accommodate local variations (Bardach & Kagan, Citation1982; Lo & Fryxell, Citation2003). Conceptual complexity has grown as various formulations of taxonomy (Kagan & Scholz, Citation1984), continuum (May & Winter, Citation2000) and dimensions (Tang et al., Citation2003) have emerged. Enquiries have also emerged to investigate the institutional factors behind their conscious choice and the preconditions that facilitate more effective enforcement. This heterogeneity could be attributed to differences in fundamental constitutional structures, types of regimes, levels of economic development and cultures.

Governments worldwide have relied mainly on an agency-dominated command-and-control format, such as mandatory saving obligations and performance standards (Arimura et al., Citation2008). It takes the form of rigid enforcement based on deterrence and punishments to correct violation behaviours. Ample evidence has proven the effectiveness of the direct approach (e.g. Burby & Paterson, Citation1993). However, it has been criticized especially for its economic inefficiency (Goulder & Parry, Citation2008). Given the heterogeneity of firms’ operation and regulators’ information asymmetry, regulators are unlikely to impose the costs of abatement equally across firms (Newell & Stavins, Citation2003). Apart from cost-inefficiency, the command-and-control approach has also been challenged for its lack of flexibility (Arimura et al., Citation2008) and of proper incentives to motivate cleaner inputs (Goulder & Parry, Citation2008). In the midst of the doubtful effectiveness of routine enforcement has come the revival of interest in proposing campaign-style, which is the strongest variant of the state-centred enforcement approach and involves ‘extraordinary mobilization of administrative resources under strong political sponsorship’ (Liu et al., Citation2015; Van Rooij, Citation2006).

During the last three decades, traditional enforcement has been gradually supplemented by new approaches (Lehmann, Citation2012). The adoption of market-based instruments, such as environmental taxes, tradable allowances and permits, grants and subsidies for pollution abatement has increased significantly (Hahn & Stavins, Citation1991; Tietenberg, Citation1990). These instruments award firms with every unit of emission reduction that is achieved below the baseline level. However, these incentive-based instruments do not target firms’ behavioural changes to adopt greener solutions. Organizations may consider such rewarding policies as low-hanging fruit and engage in opportunistic behaviours to obtain short-term gains.

An increasing number of state entities has begun to consider combining different regulatory approaches to craft a mix for their own needs and objectives. The question arises as to whether the design of a mix can at best avoid contradictions and create synergies. Lehmann (Citation2012) argues that a regulatory mix does not necessarily bring better effectiveness or efficiency than a single policy, which depends on the types of market failures and the net costs of complying with the single policy. Lambin et al. (Citation2014) find that with favourable institutional contexts, the hybrid instrument can bring benefits in terms of sustainable land use. However, there are conflicts in the interaction processes among government, NGOs, and firms due to weak regulatory governance, which echoes the prior studies in suggesting that how to balance the potential contradictions and achieve synergies remain unclear.

Despite the fact that instruments consisting of a ‘carrot’ without a ‘stick’ attract criticism regarding free-riding and excess entry issues, they signal a paradigm shift in regulatory design that is evolving from formal enforcement to a co-operative style. First, the sense of decentralizing and cooperating with a wider range of social actors becomes prevalent. By conducting a survey study in China, Zhan et al. (Citation2014) found that central government support significantly enhanced enforcement effectiveness in 2000. However, by 2006, support from the local government and collaboration with other entities had become important. Second, the notions of social innovation and value co-creation have emerged in recent years (Voorberg et al., Citation2013). These require local communities and even local citizens to participate in setting up cooperation to jointly tackle social problems. For instance, Lo and Fryxell (Citation2005) found that local government support and social support can mutually enhance perceived enforcement effectiveness, highlighting the positive effect of government-endorsed social support. Third, value co-creation also echoes the voluntary environmental programmes (VEPs) whereby organizations can take initiatives towards self-regulated environmental governance (Darnall & Sides, Citation2008). This allows more flexibility and efficiency into the system (Termeer et al., Citation2013; Van der Heijden, Citation2012). The most prevalent examples include the ISO 14001, 33/50 programme, Green Lights, and Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) (Baek, Citation2017). In sum, it is unrealistic to determine a single best regulatory approach to apply to all situations to tackle environmental issues; the effectiveness regulating environmental performance requires joint efforts from various stakeholder groups, from policy makers, local and street-level agents, the courts, and enterprises to local communities (Lo et al., Citation2009).

Corporate environmental strategies under increasing regulatory pressures

A critical question in reviewing the literature is whether and how regulated enterprises comply with environmental laws and regulations under increasingly stringent regulatory settings. A substantial body of literature has drawn on the economic, political, social, and psychological perspectives to answer this question (Annandale et al., Citation2004; Burby & Paterson, Citation1993; Hoffman, Citation2005; Shimshack & Ward, Citation2005; Winter & May, Citation2001). In a similar vein, the business and environment literature has widely examined how companies behave in response to external pressures and expectations on reducing their negative environmental externality. In this section, we start the review by looking at how firms respond to institutional demands in general. This is then followed by a detailed review of firm-level heterogeneity in regulatory compliance behaviours and strategies.

The business strategy literature has conceptualized and empirically investigated various typologies to capture corporate responses in responding to institutional demands. In her classic work on corporate strategic responses to institutional processes, Oliver (Citation1991) developed a five-dimensional conceptualization, ranging from more responsive strategies such as acquiesce, compromise, and avoidance, to more proactive defiance and manipulation. Kraatz and Block (Citation2008) developed four organizational approaches to adapt to pluralistic legitimacy standards, namely resisting/eliminating, balancing, detaching, and compartmentalizing. These works provide a solid foundation for exploring how firms differ in their responses to regulatory demands relating to the natural environment. Two distinct research focuses are identifiable. One strand of literature conceptualizes corporate environmental strategies from a performance perspective by adopting a continuum categorization. Such a continuum could range from compliance with regulations and unified industry practices, to further actions to voluntarily reduce the negative environmental externality (Bailey, Citation2008; Sharma, Citation2000). The second line of research draws on business behavioural diversity in dealing with specific issues such as green certification (Boiral, Citation2007), carbon emission (Levy & Egan, Citation2003), and dealing with new regulations (King, Citation2000). In terms of firm responses to regulation, one of the pioneering works that conceptualized the nature of organizational responses to regulation is the theory building paper by Cook et al. (Citation1983), which integrates the adaptation and mutual selection perspectives. Rugman and Verbeke (Citation1998) went a step further and categorized managerial responses towards regulation as either ‘static’ or ‘dynamic’. In responding to new pollution regulations, King (Citation2000) detected various organizational responses such as creating technological and personnel buffers, initiating changes to enhance green production, and limited cases of shifting to entirely new strategies.

Broadly speaking, these prior works largely focused on the level of environmental proactivity in developing various typologies. Recent research in regulatory compliance has begun to explore behavioural diversity beyond the conventional performance continuum perspective. Understanding such heterogeneity is of crucial importance. Just as frontline enforcement officials select from an array of strategies to achieve enforcement efficiency and effectiveness (Bardach & Kagan, Citation1982; May & Wood, Citation2003; Tang et al., Citation2003), regulated firms also develop or adopt various strategies to cope with pressure from compliance. In response to regulatory pressure, firms will select strategies that are compatible with their environmental orientations, professional standards, and experiences (Etzion, Citation2007). Built on rich interview and survey data collected from regulated enterprises in the Pearl River Delta region in China, Liu et al. (Citation2016) show that Chinese enterprises’ strategies of coping with environmental issues can be classified into four dimensions, namely formalism, accommodation, referencing, and self-determination. A ‘formalism’ strategy follows the conventional ‘go-by-the-book’ means, which use formal rules and regulations as compliance benchmarks; an ‘accommodation’ dimension prioritizes timely responses to sporadic political or bureaucratic demands; a ‘referencing’ dimension consists of paying close attention to peer firms’ compliance practices or recommended practices by industrial associations; and a ‘self-determination’ dimension emphasizes a discretionary approach that focuses on organizational autonomy and flexibility. Taken together, the multi-dimensional characterization of corporate compliance coping strategies captures the fact that firms need to develop a complex set of strategies to face various and sometimes conflicting stakeholder demands.

The role of environmental NGOs in environmental regulatory governance

Emerging from diverse social networks, ENGOs perform the duties of environmental watchdogs, as extensions of civil society, which has had substantial impacts on the regulatory regime (Doh & Teegen, Citation2002). NGOs are independent forces capable of bargaining with government on a level playing field (Simmons, Citation1998). In economically developed countries, ENGOs increasingly strategize their monitoring efforts to scrutinize regulatory agents in both international and domestic arenas (Pallas & Urpelainen, Citation2012). The monitoring role of ENGOs has also become visibly stronger in developing countries. As environmental deterioration becomes prominent relative to the rapid economic growth, ENGOs are established by both government agencies and general civil society to tackle the urgent environmental issues. China is an example: with the enactment of the state council ordinance on environmental information disclosure, ENGOs from various provinces created a Pollution Information Transparency Index (PITI) to hold government officials accountable for environmental information disclosure (Johnson, Citation2011). So far, the PITI has gained considerable influence nationwide. Regulatory agencies can also leverage ENGOs’ expertise and experience to monitor corporate environmental compliance. ENGOs can pressurize polluting industries to adopt green production by various means, from lawsuits and organized political lobbying to mobilizing consumer boycotts and popular protests (Aldashev et al., Citation2015). Sometimes, when the government is unwilling or unable to impose sufficient regulatory safeguards or such safeguards are not stringent enough, ENGOs can adopt non-traditional means to push local firms and even large transnational corporations to rise to their social and environmental responsibilities (Newell, Citation2000).

However, in terms of effective monitoring, government-organized GONGOs have been criticized for their limited role (Tang & Zhan, Citation2008). The close ties with state government make them vulnerable to political influence. As a result, they are widely considered a part of the government’s regulatory apparatus in the bureaucratic structure (Shieh, Citation2009). By contrast, civic ENGOs, generally known as ‘grassroots’ ENGOs, may have more room to perform watchdog duties, but usually in informal ways, such as writing letters to government officials, attracting media attention to certain environmental issues, and being involved in public hearings (Tang & Zhan, Citation2008). However, in developing economies, civic ENGOs still need to tiptoe around the red lines, since government still maintain tight control over their activities. Tang and Zhan (Citation2008) document a case where the ENGO tries to raise awareness about state-owned polluting enterprises, and its relationship with government becomes tense as a result. In this case, the ENGO is very likely to lose government support in the future. As a result, civic ENGOs need to carefully find the niche in which they can best strategize their monitoring influence on government and polluting firms (Li et al., Citation2017).

In sum, ENGOs have been playing an increasingly critical role in environmental regulatory governance from the domestic to the global level. Their monitoring efforts have had substantial impacts on both government and corporation behavioural changes. Difficult as the progress may be, the influence of ENGOs in developing countries is still prominent. Facing the fact that political complexity tends to hold them back when they try to confront governmental authorities directly, the ENGOs are still finding their precise role in the political process. In addition, we find that more attention is needed to understand the triangular interactions among ENGOs, governments and business corporations, and how they can affect landed environmental practices.

Cross-jurisdiction analysis: taking voluntary environmental governance as an example

Comparative investigations and cross-region analyses are undoubtedly vital in order to understand environmental regulatory governance. A central question is, do explanations of regulatory compliance differ across contexts? In general, the spilling of the regulatory regime into developing and emerging economies has led to an urgent need for regulatory studies in third world nations, with the call for adapted or original theoretical formulations capable of explaining regulatory governance there. The literature is too widely dispersed for us to review all studies that have focused on distinct bases to explain the effectiveness of regulatory governance. Regarding the most widely used command-and-control approach, our earlier review suggests that there is ample evidence from both developed and developing regimes indicating that it has both strengths and weaknesses in enhancing compliance (Dasgupta et al., Citation2000; Gunningham et al., Citation2005; Liu et al., Citation2016; Scholz & Pinney, Citation1995). In this section, we limit our focus to reviewing a cross-contextual analysis of widespread voluntary environmental governance, a crucial regulatory alternative to coercive methods and sending quick reviews.

Research on voluntary regulatory instruments embraces studies that focus on various domestic programmes and international standards implemented in a wide range of countries. Typical examples of the former strand include investigations of the effectiveness of the Responsible Care Program and the 33/50 programme in the U.S., and the Accelerated Reduction/Elimination of Toxins (ARET) Program in Canada. The convergence and adaption of voluntary approaches is also observed in developing and emerging economies. Examples abound for research interests in the Clean Industry Program in Mexico (Henriques et al., Citation2013), the Sustainable Tourism Program in Costa Rica (Rivera, Citation2004), and the Green Ratings Project in India (Blackman, Citation2008). Although investigations on various domestic VEPs provide rich insights, it may be risk to generalize from the conclusions of these studies. Examining the effectiveness of international standards across contexts offers additional insights. For example, empirical investigations of the mostly examined ISO 14001certification were broadly evidenced in both developed and developing regimes (Boiral, Citation2007; Fryxell et al., Citation2004; Potoski & Prakash, Citation2004).

In spite of its growing popularity and diversity, the merit of VEPs has remained controversial. Large-scale work on the contextual variations is notably limited in the literature. Efforts to bridge context-level analysis have taken several forms and generated three major insights. Both cross-regime convergence and divergence have been identified. First, evidence from comparative investigations highlights divergence in regulatory goals, design, and implementation means. As Prakash and Potoski (Citation2012) concludes, the emergence of voluntary environmental regulation across countries could be attributed to variations in the existing configurations of policy instruments, political institutions, and political culture. VEPs differ not only in design and requirements but also in brand values as perceived by regulated firms.

Second, institutional distinctions contribute to the global diffusion of voluntary tools. In examining a government-sponsored VEP in China, Liu et al. (Citation2018a) found that policy uncertainty has a distinct influence on within-industry and within-jurisdiction diffusion of voluntary environmental practices. In terms of diffusion of international environmental standards, accumulated evidence also suggest that it varies across regulatory contexts since firms face various types of institutional environments in terms of compliance culture, stakeholder pressure, and degrees of exposure to regulatory oversight.

Third, the efficacy of VEPs varies across contexts. The weakness of voluntary programmes due to lack of effective monitoring and sanction mechanisms is prevalent in both developed and developing regimes. This is evidenced in comparative case studies across nations, quantitative investigations of a wide array of domestic programmes in a single country, and cross-country analysis of the aggregate benefits of VEPs. For instance, meta-analysis results indicate the limited effectiveness of the collective VEPs in the U.S. in that participants do not improve performance over nonparticipants (Darnall & Sides, Citation2008). Similar findings were yielded from the ISO 14001 certification in Mexico (Blackman & Guerrero, Citation2012) and cross-country case comparison (two programmes in Mexico and one in India) (Blackman, Citation2008).

In sum, our review above demonstrates that VEPs are perceived with quite divergent roots and effectiveness. Despite the weak process-control mechanism, there are still many institutionalized factors embedded that could potentially affect the landing of VEPs. A possible direction to understand VEPs with more commensurability is to go micro in terms of the analysis level. In addition to a manifold of institutional factors, there can be similarities in organizational judgements and behavioural traits when considering adopting VEPs as strategies to cope with regulatory pressures, which to some extent can lead to more or less effective VEP outcomes. A more fine-grained analysis could also provide fundamental understandings for designing effective VEP programmes by the institution. From a macro picture, the review highlights the need for more large-scale cross-jurisdiction investigations to reconcile the mixed findings not only in current VEP research but also in the broader environmental regulation and compliance domains. We discuss potential future directions in the concluding part.

Research methodologies in environmental regulatory governance

Research methodologies adopted in the environmental regulatory governance literature have become increasingly sophisticated in order to seize the dynamics of enforcement, compliance and monitoring during the regulatory process. Our earlier review of the literature falls in three broader methodological groups, namely qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods (see ).

Table 2. Research methodology.

Early works are most notably case studies (Delmas & Keller, Citation2005; Tilt, Citation2007), interviews (Johnson, Citation2011; Lo et al., Citation2016), and content analysis (Krippendorff, Citation1980). A more sophisticated practice was a combination of these, particularly in the context of developing and non-democratic settings, where regulatory information was scarce and fragmented, in order to provide a more solid inferential empirical basis for theorizing and generalization (e.g. Lo et al., Citation2000). Although these qualitative studies have the advantage of penetrating to the underlying mechanisms of regulatory governance, the lack of statistical data prevents the literature from establishing casual links (Iraldo et al., Citation2011).

With the emergence of theory-driven research questions, quantitative research methods have increasingly been employed for these deductive inquiries. Among them, the questionnaire survey was perhaps the most frequently used, with information collected from CEOs and managers (Arimura et al., Citation2008; Fryxell et al., Citation2004; Henriques & Sadorsky, Citation1999), regulatory officials (Tang et al., Citation2003), and ENGO leaders (Li et al., Citation2017) with respect to the changes in institutional contexts and regulation attributes at different time points (Lo et al., Citation2016). Researchers also used secondary archival data to model real-world phenomena using more sophisticated econometric methods (Lyon & Maxwell, Citation2007; McGuire et al., Citation2018). With advanced data analytic methods and computer-aided techniques, researchers are able to build large datasets with cross-sectional or longitudinal data points. In order to untangle the inconsistent findings, researchers also rely on meta-analysis techniques (Albertini, Citation2013; Darnall & Sides, Citation2008). Meta-analysis overcomes several shortfalls. First, it is concerned with the ‘size’ of the observed effect rather than whether the effect is significant. Second, it corrects for sampling biases. Third, it allows for comparisons among studies that evaluate related but not necessarily identical dependent variables.

In recent years, more and more researchers have turned to experimental methods. The regulatory field provides a rich setting to apply field and lab experimental design to explore the effectiveness of various regulatory approaches in modifying regulatees’ attitudes, preferences, and subsequent compliance behaviours (Croson & Treich, Citation2014). For example, Telle (Citation2013) adopted a natural field experiment design to examine the efficacy of a regulatory programme initiated by the Norwegian Environmental Protection Agency to enforce hazardous substances regulations, by randomly assigning monitoring and enforcement actions to manufacturing firms. A less-common method adopted is modelling and simulation studies, which are widely used in environmental economics to examine regulatory topics. For instance, Jaffe and Stavins (Citation1995) ran a simulation study to compare the diffusion of new technology. La Nauze and Mezzetti (Citation2019) model the regulation of diffuse emissions via regulatory incentives through the combination of tax rebates.

In sum, the methodology in environmental regulatory governance literature has become more sophisticated and diversified over time. The trend has moved from cross-sectional single-year observation to longitudinal analysis, and from using a single method to using mixed methods. The most frequent combination is perhaps to integrate survey and interview data (Kuperan & Sutinen, Citation1998; Lo & Fryxell, Citation2005; Wang & Jin, Citation2006). The strength of mixed methods also manifests in an array of research designs defined by the priority and sequence of the respective method (Molina-Azorín & López-Gamero, Citation2016).

Reflections and conclusions

Environmental regulatory governance research inherits shared traditions from the generic regulatory governance literature, but still displays a certain uniqueness due to its clean-cut regulatory standards. Our review highlights the growing complexity in the field, notably in the search for alternative methods as the traditional command-and-control approach has proved to be of limited effectiveness; the inquiries into the puzzling response of regulated firms in an increasingly stringent regulatory setting and an ever expanding environmental legal regime; the exploration into the aggressive monitoring strategies of ENGOs under the growing recognition that they can be an ally to regulatory agencies; the examination of cross-jurisdiction regulation to combat environmental crises on a world scale; and the adoption of sophisticated and innovative research methodologies to take advantage of the worldwide information bloom and data multiplicity in advancing the theoretical frontiers and solving practical environmental problems. How do these set the agenda for the future environmental regulatory research?

First, in the conceptualization of environmental regulatory enforcement style, the emerging thinking and practice of dividing the inspection role from the sanctioning role has gained increasing support. This division serves the significant need of improving the accountability of regulatory enforcement units and minimizing the likelihood of a shirking effect from the regulated entities. It also mitigates potential conflicts of interest and ensures the effectiveness of enforcement landing. Liu et al. (Citation2018b) advanced this emerging concept with empirical support in the China pollution control context by distinguishing the implementation of enforcement independently as inspection and sanction. To further study the effectiveness of frontline enforcement, a stream of research has emerged to explore the complementary tool of enforcement campaigns. For example, Liu et al. (Citation2015) developed a dual pathway model to unpack the recoupling mechanisms of campaign-style enforcement.

Second, our review highlights the significance of understanding more than the fact that industrial firms differ in both environmental compliance strategies and performance. The traditional literature has mainly subscribed to regulatory perspectives to examine these variations. Recent research integrates the regulatory and strategy literature to explore the strategic and behavioural pattern formed in the regulatory process. In our earlier work on corporate environmental coping strategies, for example, we shift the study of corporate environmental behaviour to a diversity perspective instead of the traditional performance view. This new lens bridges compliance performance and its antecedents by explaining when a certain strategy will be adopted and its performance outcome. Future research could build on the frameworks and results to study corporate compliance strategies in a wide range of regulatory domains, and more importantly, how they potentially evolve over time.

Third, to deepen ENGO research, increasing research attention should be directed to ENGOs’ organizations, strategies and effectiveness in achieving their watchdog functions in the regulatory process. For example, a multiple stakeholder perspective can be considered when we seek to understand how ENGOs’ monitoring strategies would change over time, from confrontation to seeking partnership, from a single strategy to a mixed strategy, in response to the divergent environmental interests of individual donors and funding bodies as well as taking advantage of the rise of Internet environmental activism and the growing influence of ESG investment. Finally, in-depth studies of ENGOs’ monitoring strategy in developing countries are badly needed where ENGOs’ limited organizational and resources capacity are pronounced and the regulatory contexts are more hostile to their watchdog role than in Western countries.

Fourth, a careful research design with a long-term research plan is strongly desirable to effectively capture the growing complexity of environmental regulatory governance. The mixed-method design has been accepted as of high rigour and explanatory power. Meanwhile, the use of objective (or archival) data could positively supplement the self-reported data by revealing actual regulatory actions and outcomes. An emerging trend is to employ data science methods by assembling a large dataset from available statistics for descriptive or predictive analyses, which has been made feasible and attractive with greater disclosure practices in environmental information and pollution statistics. However, large datasets are not always problem-free, particularly in the measurement of constructs, the treatment of correlation as causal relations in data analysis, and the lack of strong theoretical underpinning above the data-mining endeavour. In spite of the above, we acknowledge that recent methodological developments offer opportunities to advance and test the theory of environmental regulation and compliance. In particular, the Big Data movements make data utilization for full-cycle studies possible. One obvious extension is to integrate the considerable amount of data from social media, Internet searches, and NGO monitoring data with the increasingly available, government-disclosed data. Such data integration offers strengths in data and measurement sources to explore the breadth and depth of interactions within the ‘regulatory triangle’. This potential has been demonstrated in recent efforts to examine the underlying mechanisms of how non-governmental monitoring increase the compliance of local governments with central mandates in environmental information disclosure (Anderson et al., Citation2019). More rigorous and comprehensive work in this and other directions is needed.

Finally, as shown in our conceptualization in , there is a call for an interactive perspective in the proper integration of these three key actors of enforcement agencies, regulated firms and ENGOs in a single study in terms of theory, methodology and research design to capture the full picture of environmental regulation. Previous research has mainly taken only one of these actors as the core focus in research question formulation, research design, analytical framework development, and research methods adoption. Although theoretically there are already conceptual formulations available for possible reference, like collaborative regulatory governance, the ‘regulatory triangle’ model, and possibly ecological modernization, they are still too loose to provide a sound analytical framework to sort out the theoretical linkage and interactions among them in the regulatory process, not to mention the challenges in research design and data analyses. Added to the complication is the further integration of different levels of regulation, ranging from domestic level to the global level. In unpacking the complexity, the starting point may well be a study of the interactions of two actors at a given regulatory level. Particularly interesting are the enforcement-compliance linkage on the agencies-firms’ approaches-strategies responses, the enforcement-monitoring linkage on the patterns of environmental agencies-ENGO alliances; and the compliance-monitoring linkage on the effect of ENGO regulatory pressures on firms’ compliance behaviours. More can be explored. It is our hope that our comparative review of the three broad environmental regulatory topics and methodological issues will spark future ideas to advance the field.

Acknowledgement

The research reported in this article was partially funded by the project ‘Campaign-Style Enforcement and Environmental Compliance in China: A Comparative and Longitudinal Study’ supported by the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (RGC No.: 15609815). We thank for the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments which have helped to improve the intelligibility of our review paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Carlos Wing-Hung LO is professor and head of the Department of Government and Public Administration at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. His main research interests are in the areas of law and government, environmental management, public sector management, and corporate social and environmental responsibility, within the contexts of China and Hong Kong.

Ning Liu is an assistant professor in the Department of Public Policy at the City University of Hong Kong. Her research focuses on government-business relations and public policy implementation.

Xue Pang is post-doctoral fellow in Department of Management at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her research interests are mainly in the area of non-market strategy, especially stakeholder management, strategic corporate social responsibility (CSR), and CSR communication in the contexts of China and Hong Kong.

Pansy Hon Ying Li is Teaching Fellow in the Department of Management and Marketing at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Her research interests are entrepreneurship, business sustainability, social networks and corporate social responsibility.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Afsah, S., Laplante, B., & Wheeler, D. (1996). Controlling Industrial Pollution: a new paradigm (No. 1672). World Bank, Policy Research Department, Environment, Infrastructure, and Agriculture Division.

- Albertini, E. (2013). Does environmental management improve financial performance? A meta-analytical review. Organization & Environment, 26(4), 431–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026613510301

- Aldashev, G., Limardi, M., & Verdier, T. (2015). Watchdogs of the invisible hand: NGO monitoring and industry equilibrium. Journal of Development Economics, 116, 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.03.006

- Anderson, S. E., Buntaine, M. T., Liu, M., & Zhang, B. (2019). Non-governmental monitoring of local governments increases compliance with central mandates: A national-scale field experiment in China. American Journal of Political Science, 63(3), 626–643. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12428

- Annandale, D., Taplin, R., & Wallington, T. (2004). The determinants of company response to environmental regulation. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 6(2), 107–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908042000320704

- Arimura, T. H., Hibiki, A., & Katayama, H. (2008). Is a voluntary approach an effective environmental policy instrument?: A case for environmental management systems. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 55(3), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2007.09.002

- Baek, K. (2017). The diffusion of voluntary environmental programs: The case of ISO 14001 in Korea, 1996–2011. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(2), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2846-3

- Bailey, I. (2008). Industry environmental agreements and climate policy: Learning by comparison. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 10(2), 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080801928410

- Bardach, E., & Kagan, R. A. (1982). Going by the book: The problem of regulatory unreasonableness. Rev. Ed. Transaction Publishers.

- Blackman, A. (2008). Can voluntary environmental regulation work in developing countries? Lessons from case studies. Policy Studies Journal, 36(1), 119–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2007.00256.x

- Blackman, A., & Guerrero, S. (2012). What drives voluntary eco-certification in Mexico? Journal of Comparative Economics, 40(2), 256–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2011.08.001

- Boiral, O. (2007). Corporate greening through ISO 14001: A rational myth? Organization Science, 18(1), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0224

- Burby, R., & Paterson, R. G. (1993). Improving compliance with state environmental regulations. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 12(4), 753–772. https://doi.org/10.2307/3325349

- Cook, K., Shortell, S. M., Conrad, D. A., & Morrisey, M. A. (1983). A theory of organizational response to regulation: The case of hospitals. Academy of Management Review, 8(2), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1983.4284718

- Croson, R., & Treich, N. (2014). Behavioural environmental economics: Promises and challenges. Environmental and Resource Economics, 58(3), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9783-y

- Darnall, N., & Sides, S. (2008). Assessing the performance of voluntary environmental programs: Does certification matter? Policy Studies Journal, 36(1), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2007.00255.x

- Dasgupta, S., Hettige, H., & Wheeler, D. (2000). What improves environmental compliance? Evidence from Mexican industry. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 39(1), 39–66. https://doi.org/10.1006/jeem.1999.1090

- Delmas, M., & Keller, A. (2005). Free riding in voluntary environmental programs: The case of the US EPA WasteWise program. Policy Sciences, 38(2-3), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-005-6592-8

- Doh, J. P., & Teegen, H. (2002). Nongovernmental organizations as institutional actors in international business: Theory and implications. International Business Review, 11(6), 665–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-5931(02)00044-6

- Etzion, D. (2007). Research on organizations and the natural environment, 1992-present: A review. Journal of Management, 33(4), 637–664. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307302553

- Fryxell, G. E., Lo, C. W. H., & Chung, S. S. (2004). Influence of motivations for seeking ISO 14001 certification on perceptions of EMS effectiveness in China. Environmental Management, 33(2), 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-003-0106-2

- Goulder, L. H., & Parry, I. W. (2008). Instrument choice in environmental policy. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 2(2), 152–174. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/ren005

- Gunningham, N. (2009). The new collaborative environmental governance: The localization of regulation. Journal of Law and Society, 36(1), 145–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6478.2009.00461.x

- Gunningham, N. A., Thornton, D., & Kagan, R. A. (2005). Motivating management: Compliance in environmental protection. Law & Policy, 27(2), 289–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9930.2005.00201.x

- Hahn, R. W., & Stavins, R. N. (1991). Incentive-based environmental regulation: A new era from an old idea? Ecology LQ, 18, 1. https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38BC12

- Henriques, I., Husted, B. W., & Montiel, I. (2013). Spillover effects of voluntary environmental programs on greenhouse gas emissions: Lessons from Mexico. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 32(2), 296–322. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.21675

- Henriques, I., & Sadorsky, P. (1999). The relationship between environmental commitment and managerial perceptions of stakeholder importance. Academy of Management Journal, 42(1), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.5465/256876

- Hoffman, A. J. (2005). Business decisions and the environment: Significance, challenges, and momentum of an emerging research field. In G. Brewer & P. Stern (Eds.), Decision making for the environment: Social and Behavioral science research Priorities (pp. 200–229). National Research Council, National Academies Press.

- Iraldo, F., Testa, F., Melis, M., & Frey, M. (2011). A literature review on the links between environmental regulation and competitiveness. Environmental Policy and Governance, 21(3), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.568

- Jaffe, A. B., & Stavins, R. N. (1995). Dynamic incentives of environmental regulations: The effects of alternative policy instruments on technology diffusion. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 29(3), S43–S63. https://doi.org/10.1006/jeem.1995.1060

- Johnson, T. (2011). Environmental information disclosure in China: Policy developments and NGO responses. Policy & Politics, 39(3), 399–416. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557310X520298

- Kagan, R. A. (1989). Editor’s introduction: Understanding regulatory enforcement. Law & Policy, 11(2), 89–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9930.1989.tb00022.x

- Kagan, R. A., & Scholz, J. T. (1984). The “criminology of the corporation” and regulatory enforcement strategies. In K. Hawkins & J. Thomas (Eds.), In Enforcing Regulation (pp. 352–377). Boston: Kluwer-Nijho.

- King, A. A. (2000). Organizational response to environmental regulation: Punctuated change or Autogenesis? Business Strategy and the Environment, 9(4), 224–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0836(200007/08)9:4<224::AID-BSE249>3.0.CO;2-X

- Kraatz, M. S., & Block, E. S. (2008). Organizational implications of institutional pluralism. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 243–275). Sage.

- Krippendorff, K. (1980). Validity in content analysis.

- Kuperan, K., & Sutinen, J. G. (1998). Blue water crime: Deterrence, legitimacy, and compliance in fisheries. Law & Society Review, 32(2), 309–338. https://doi.org/10.2307/827765

- Lambin, E. F., Meyfroidt, P., Rueda, X., Blackman, A., Börner, J., Cerutti, P. O., Dietsch, T., Jungmann, L., Lamarque, P., Lister, J., & Walker, N. F. (2014). Effectiveness and synergies of policy instruments for land use governance in tropical regions. Global Environmental Change, 28, 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.06.007

- La Nauze, A., & Mezzetti, C. (2019). Dynamic incentive regulation of diffuse pollution. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 93, 101–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2018.11.009

- Lehmann, P. (2012). Justifying a policy mix for pollution control: A review of economic literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 26(1), 71–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2010.00628.x

- Levy, D. L., & Egan, D. (2003). A neo-gramscian approach to corporate political strategy: Conflict and accommodation in the climate change negotiations. Journal of Management Studies, 40(4), 803–829. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00361

- Li, H., Lo, C. W. H., & Tang, S. Y. (2017). Nonprofit policy advocacy under authoritarianism. Public Administration Review, 77(1), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12585

- Liu, N., Lo, C. W. H., Zhan, X., & Wang, W. (2015). Campaign-style enforcement and regulatory compliance. Public Administration Review, 75(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12285

- Liu, N., Tang, S. Y., Lo, C. W. H., & Zhan, X. (2016). Stakeholder demands and corporate environmental coping strategies in China. Journal of Environmental Management, 165, 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.09.027

- Liu, N., Tang, S. Y., Zhan, X., & Lo, C. W. H. (2018a). Policy uncertainty and corporate performance in government-sponsored voluntary environmental programs. Journal of Environmental Management, 219, 350–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.04.110

- Liu, N., van Rooij, B., & Lo, C. W. H. (2018b). Beyond deterrent enforcement styles: Behavioural intuitions of Chinese environmental Law enforcement agents in a context of challenging inspections. Public Administration, 96(3), 497–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12415

- Lo, C. W. H., & Fryxell, G. E. (2003). Enforcement styles among environmental protection officials in China. Journal of Public Policy, 23(1), 81–115. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X03003040

- Lo, C. W. H., & Fryxell, G. E. (2005). Governmental and societal support for environmental enforcement in China: An empirical study in Guangzhou. Journal of Development Studies, 41(4), 558–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380500092655

- Lo, C. W. H., Fryxell, G. E., & Van Rooij, B. (2009). Changes in enforcement styles among environmental enforcement officials in China. Environment and Planning A, 41(11), 2706–2723. https://doi.org/10.1068/a41357

- Lo, C. W. H., Liu, N., Li, P. H. Y., & Wang, W. (2016). Controlling industrial pollution in urban China: Towards a more effective institutional milieu in the guangzhou environmental protection bureau? China Information, 30(2), 232–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X16651059

- Lo, C. W. H., Yip, P. K. T., & Cheung, K. C. (2000). The regulatory style of environmental governance in China: The case of EIA regulation in Shanghai. Public Administration and Development: The International Journal of Management Research and Practice, 20(4), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-162X

- Lyon, T. P., & Maxwell, J. W. (2007). Environmental public voluntary programs reconsidered. Policy Studies Journal, 35(4), 723–750. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2007.00245.x

- May, P., & Winter, S. (2000). Reconsidering styles of regulatory enforcement: Patterns in Danish agro-environmental inspection. Law & Policy, 22(2), 143–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9930.00089

- May, P. J., & Wood, R. S. (2003). At the regulatory front lines: Inspectors’ enforcement style and regulatory compliance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 13(2), 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mug014

- McGuire, W., Hoang, P. C., & Prakash, A. (2018). How voluntary environmental programs reduce pollution. Public Administration Review, 78(4), 537–544. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12832

- Molina-Azorín, J. F., & López-Gamero, M. D. (2016). Mixed methods studies in environmental management research: Prevalence, purposes and designs. Business Strategy and the Environment, 25(2), 134–148. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1862

- Newell, P. (2000). Environmental NGOs, TNCs, and the question of governance. In V. D’Assetto & D. Stevis (Eds.), The international political economy of the environment (pp. 85–107). Lynne Rienner.

- Newell, R. G., & Stavins, R. N. (2003). Cost heterogeneity and the potential savings from market-based policies. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 23(1), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021879330491

- Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 145–179. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1991.4279002

- Pallas, C. L., & Urpelainen, J. (2012). NGO monitoring and the legitimacy of international cooperation: A strategic analysis. Review of International Organizations, 7(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-011-9125-6

- Potoski, M., & Prakash, A. (2004). The regulation dilemma: Cooperation and conflict in environmental governance. Public Administration Review, 64(2), 152–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00357.x

- Prakash, A., & Potoski, M. (2012). Voluntary environmental programs: A comparative perspective. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 31(1), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20617

- Rivera, J. (2004). Institutional pressures and voluntary environmental behavior in developing countries: Evidence from the Costa Rican hotel industry. Society and Natural Resources, 17(9), 779–797. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920490493783

- Rugman, A. M., & Verbeke, A. (1998). Corporate strategies and environmental regulations: An organizing framework. Strategy Management Journal, 19(4), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199804)19:4<363::AID-SMJ974>3.0.CO;2-H

- Scholz, J. T., & Pinney, N. (1995). Duty, fear, and tax compliance: The heuristic basis of citizenship behavior. American Journal of Political Science, 39(2), 490–512. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111622

- Sharma, S. (2000). Managerial interpretations and organizational context as predictors of corporate choice of environmental strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 681–697. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556361

- Shieh, S. (2009). Beyond corporatism and civil society: Three modes of state-NGO interaction in China. In J. Schwartz & S. Shieh (Eds.), State and society responses to social welfare needs in China: Serving the people (pp. 22–41). Routledge.

- Shimshack, J. P., & Ward, M. B. (2005). Regulator reputation, enforcement, and environmental compliance. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 50(3), 519–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2005.02.002

- Simmons, P. J. (1998). Learning to Live with NGOs. Foreign Policy, 112(112), 82–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1149037

- Tang, S. Y., Lo, C. W. H., & Fryxell, G. E. (2003). Enforcement styles, organizational commitment, and enforcement effectiveness: An empirical study of local environmental protection officials in urban China. Environment and Planning A, 35(1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1068/a359

- Tang, S. Y., & Zhan, X. (2008). Civic environmental NGOs, civil society, and democratisation in China. Journal of Development Studies, 44(3), 425–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380701848541

- Telle, K. (2013). Monitoring and enforcement of environmental regulations: Lessons from a natural field experiment in Norway. Journal of Public Economics, 99, 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.01.001

- Termeer, C. J., Stuiver, M., Gerritsen, A., & Huntjens, P. (2013). Integrating self-governance in heavily regulated policy fields: Insights from a Dutch Farmers’ cooperative. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 15(2), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2013.778670

- Tietenberg, T. H. (1990). Economic instruments for environmental regulation. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 6(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/6.1.17

- Tilt, B. (2007). The political ecology of pollution enforcement in China: A case from Sichuan's rural industrial sector. The China Quarterly, 192, 915–932. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741007002093

- Van der Heijden, J. (2012). Voluntary environmental governance arrangements. Environmental Politics, 21(3), 486–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2012.671576

- Van Rooij, B. (2006). Regulating land and pollution in China: Lawmaking, compliance, and enforcement: Theory and cases. Amsterdam University Press.

- Veugelers, R. (2012). Which policy instruments to induce clean innovating? Research Policy, 41(10), 1770–1778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.06.012

- Voorberg, W., Bekkers, V., & Tummers, L. (2013, 11 September–13 September). Co-creation and co-production in social innovation: A systematic review and future research agenda. Proceedings of the EGPA Conference, Edinburgh. [Paper presentation].

- Wang, H., & Jin, Y. (2006). Industrial ownership and environmental performance: Evidence from China. Environmental and Resource Economics, 36(3), 255–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-006-9027-x

- Winter, S. C., & May, P. J. (2001). Motivation for compliance with environmental regulations. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 20(4), 675–698. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.1023

- Zhan, X., Lo, C. W. H., & Tang, S. Y. (2014). Contextual changes and environmental policy implementation: A longitudinal study of street-level bureaucrats in Guangzhou, China. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 24(4), 1005–1035. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mut004