ABSTRACT

This paper presents a novel framework for analyzing the formation and effects of strategies in environmental governance. It combines elements of management studies, strategy as practice thinking, social systems theory and evolutionary governance theory. It starts from the notion that governance and its constitutive elements are constantly evolving and that the formation of strategies and the effect strategies produce should be understood as elements of these ongoing dynamics. Strategy is analyzed in its institutional and narrative dimensions. The concept of reality effects is introduced to grasp the various ways in which discursive and material changes can be linked to strategy and to show that the identification of strategies can result from prior intention as well as a posteriori ascription. The observation of reality effects can enhance reality effects, and so does the observation of strategy. Different modes and levels of observation bring in different strategic potentialities: observation of self, of the governance context, and of the external environment. The paper synthesizes these ideas into a framework that conceptualizes strategies as productive fictions that require constant adaptation. They never entirely work out as expected or hoped for, yet these productive fictions are necessary and effective parts of planning and steering efforts.

Introduction

Environmental policy and planning strive to make a difference in the world. No environmental governance, policy and planning without ambition. Strategy, as a vision for a desirable future, coupled to an idea of how to get there, is one of the crucial ways actors attempt to make a difference. Although strategy has never been absent from governance, policy and planning, it has lost some of its public and academic popularity. It has been critiqued as shallow managerial wisdom, for its military connotations and association with naïve modernist ideas of steering and control. Yet, what made modernist governance attractive in the first place still holds attraction to politics and administration: the promise of steering, of comprehensive planning, rational knowledge integration, and, ultimately, of grand strategy (Eriksson & Lehtimäki, Citation2001; Hillier, Citation2002; Scott, Citation1998). Actors in and beyond governance never stopped strategizing and with the discussions on climate change and more recently the global Covid19 pandemic, media report on a daily basis about governments, communities, and companies strategizing for the years to come.

In 20 years of JEPP, various contributors have insightfully dealt with strategies towards X or Y, in policy domain A or B (Grunwald, Citation2007; Hertin & Berkhout, Citation2003; Lindseth, Citation2005; Voss et al., Citation2007). What received much less attention was the concept of strategy itself. In this paper we aim to rethink the concept of strategy and explore its possibilities and limitations in environmental governance by focusing on the role of strategy in the context of governance and its reality effects. We believe it is worthwhile to rethink the concept of strategy in environmental policy and planning and more broadly within the context of governance for a number of reasons. First of all it is often taken for granted in planning and governance literatures without further interrogation or conceptual development. Second, in recent years the concept has received considerable attention in neighboring disciplines and literatures such as the strategy- as-practice literature (Golsorkhi et al., Citation2010; Jarzabkowski, Citation2004; Whittington, Citation1996), critical management studies (Alvesson et al., Citation2009; Tadajewski et al., Citation2011), interpretive policy analysis (Bevir & Rhodes, Citation2015; Yanow, Citation2014), systems theory (Luhmann, Citation1989, Citation1990, Citation1995; Seidl, Citation2016). The insights gained there can enrich the understanding of strategy in environmental governance and planning. Third, a foregrounding of strategy can clarify possibilities and limits to managing the environment through policy and planning. It can add a more dialectical dimension to the literature on adaptive and reflexive governance (Feindt & Weiland, Citation2018; Hendriks & Grin, Citation2007; Torgerson, Citation2018; Voss et al., Citation2007), by addressing not just how strategies are formulated and put to work, but also how the identification, observation and labeling of something as a strategy or as effect of a strategy feed back into governance, triggering new strategies and affecting existing ones. Understanding strategy does not directly solve environmental problems but offers insight into the available tools towards solutions of governance problems in general, which can thus unlock new solutions, by removing erroneous assumptions and possibly distorted expectations for existing strategies (cf. De Roo, Citation2010; Gunder & Hillier, Citation2009; Van Assche et al., Citation2014; Walker & Shove, Citation2007).

In environmental policy and planning, a variety of knowledges, institutions, issues, actors and feedback loops in and between the social and the ecological side of social-ecological systems comes into play (Bodin, Citation2017; Van Assche, Verschraegen, Valentinov, et al., Citation2019). Usually, a variety of governmental actors is involved, but governance perspectives acknowledge the importance of other actors, including NGOs, community organizations, interest groups, and private companies (Bryson et al., Citation2018). Environmental policy and planning are forms of governance, embedded in broader governance configurations, where actors make collectively binding decisions in the pursuit of public goods. Strategy in governance requires investigation, before addressing the domain of environmental governance more specifically. Governance changes continuously, partly as a result of strategies, but also under influence of other actions and events (Duit & Galaz, Citation2008; Pierson, Citation2000).

In our conceptualization of strategy in governance, both the formation of strategy and the effects matter. We first look at the strategy concept itself. We pay attention to what is understood and recognizable as strategy and outline two main dimensions of governance strategy: narrative and institution. After which we elaborate the concept of reality effects of strategy and argue for an emphasis on observation in the analysis and making of strategy. In the investigation of reality effects, we highlight strategy as productive fiction, in other words, as always-impossible yet entirely necessary, enabling governance to look forwards. We conclude with an acknowledgement of the limitations of both strategy and governance and thus of environmental policy and planning but offer the concepts of intermediate strategy and transitional governance as part of a strategic repertoire for situations where articulation of substantive and long-term strategy might not be possible (yet).

Strategy and governance

Lawrence Freedman, in his book Strategy: A history, mentions that there is no agreed-upon definition of strategy that describes the field and limits its boundaries. Common contemporary definitions describe it as being about maintaining a balance between ends, ways, and means; about identifying objectives; and about the resources and methods available for meeting such objectives. This balance requires not only finding out how to achieve desired ends but also adjusting ends so that realistic ways can be found to meet them by available means (Freedman, Citation2015).

For us, strategy is a vision for a desirable longer-term future, coupled to an idea of how to get there. It is thus distinct from dream, fantasy, or projection (Gunder & Hillier, Citation2009). In this definition it is also distinct from tactics, based on the time dimension: tactics focus on short-term and on direct action.

If we start with this elementary notion, we can see that strategy is everywhere in governance. People strategize, organizations and communities strategize, as philosophers going back to Plato and Aristotle already acknowledged (Aristotle, Citation2015; Bloom & Kirsch, Citation2016). In early modern times, the political philosophy of Niccolo Machiavelli testifies to the entwining of individual, group, and communal strategies Machiavelli (Citation2009 [Citation1517]). Individuals strive to get somewhere, in factions, which similarly strategize, as part of cities and states, with an emergent agency allowing them to strategize as collectives (Höglund & Svärdsten, Citation2018; Kornberger & Engberg-Pedersen, Citation2019). For the classics, it was already apparent that strategy is inherently implicated in power relations, as it often envisions a change of power relations, and entails the use of power, either through coercion, persuasion, or the reshaping of perceptions, either openly or in the shade (Flyvbjerg, Citation1998; Vasquez, Citation1998). It was clear that strategy is a necessity for coordination of larger collectives towards collective goods, or to fence off looming threats (Kagan, Citation2006; Van Assche et al., Citation2016).

In more recent times, the shifting roles of public and private actors in governance and the introduction of new policy instruments have fueled a still growing and renewed attention for so -called governance strategies (Biermann et al., Citation2017; Grotenbreg & Van Buuren, Citation2017; Imperial, Citation2005; Pierre, Citation2000). Governance strategies are regularly discussed as alternatives to what is labeled as more traditional forms of policy, such as regulation or financial incentives. Examples include collaborative strategies or networking strategies (Ansell & Gash, Citation2017; Scott & Thomas, Citation2017). These governance strategies are often presented as more effective or legitimate and they are seen as part of a broader normative agenda of governance reform in which the role of government is decreased in favor of markets and civil society (Barnes et al., Citation2007; Bell & Hindmoor, Citation2009; Bevir & Rhodes, Citation2016). We would argue however that this terminology is rather misleading and springs from the supposed discovery of governance (versus government), a discovery of something that then supposedly could be applied.

Yet ‘governance’ has always been there. A period of a central and completely independent steering ‘government’ never existed; we are rather dealing with continuously shifting governance configurations (Pierre & Peters, Citation2019; Van Assche et al., Citation2014). Strategy was always involved in the crafting of governance configurations, or institutional design (Cooke & Kothari, Citation2001; Machiavelli, Citation2009 [Citation1517]). In other words, speaking of ‘governance strategies’ creates no understanding of the forms and roles of strategy in governance. We still need a separate consideration of ‘strategy’ and strategy in governance.

We take the position that each governance context, with its own particular evolution and pattern of actors and institutions, is partly the product of strategy, and enables the practice of strategizing in a particular manner, while it shapes the possible effects of strategy (cf. Alvesson & Ashcraft, Citation2009; Seidl, Citation2016). When speaking of environmental governance, it is clear that systems are not necessarily adapted to their environment in the sense that their policies take optimal care of that environment. What environmental policy and planning can do, hinges on the overall configuration of governance and the particular entwining of social and ecological systems (De Roo, Citation2017; Van Assche et al., Citation2014). The evolution of a particular governance context makes the emergence of certain ideas, policies, actors and knowledges more likely, but the same evolution does not guarantee that what emerges will have positive environmental effects (Latour, Citation2004).

Thus, we can speak of the evolution of environmental governance within broader governance and can say that these nested and co-evolving environments create spaces for particular modes and effects of strategizing, while also creating environmental issues which require strategizing. Often, what emerges as a strategy has different environmental effects from what was initially envisioned and might not achieve adequate coordination given the conditions of the system. Systems do not naturally take care of their environment, nor do they have perfect knowledge of it (Van Assche et al., Citation2017a). Attempts to strategically manage the environment encounter those obstacles. Analyzing strategy in governance remains essential however in tracing the possibilities to relate the system and its physical environment. In the next sections we map out this terrain.

Before deepening the analysis of strategy and strategy in governance, it is useful to remind ourselves that strategizing never stops (Mintzberg, Citation1978). Which means that we can make a non-trivial distinction between strategy as the plan or policy itself (e.g. Albrechts, Citation2004), strategy preceding the formation of the policy and strategy afterwards, in the implementation process (e.g. Pressman & Wildavsky, Citation1984; Throgmorton, Citation1996). Furthermore, an environmental plan or policy can be part of a larger strategy, using other tools of governance, e.g. taxation (e.g. Brindley et al., Citation2005; Forester, Citation1988). This renders visible a first set of roles of strategy in governance. A closer look at strategy itself will allow us to expand this set.

Strategy: actions and intentions

Most work on strategy is found in the context of management and organization studies. Within these fields, strategy has been defined and understood in many different ways (Neugebauer et al., Citation2016). Mintzberg (Citation1978) reflected on these different definitions and their relation and argued that although some definitions compete, they can also complement each other. His main concern was with the relation between strategies as plan and strategies as patterns (Citation1978). Whereas the first perspective sees strategies as purposefully developed sets of actions, the latter focuses on the emerging consistency in behavior that at some point could be labeled as strategy. The difference between both perspectives lies in the relation between intentions and actions, whereby intentions are rarely fully known. Actions can differ from intentions, communicated intentions can deviate from actual intentions, and intentions can be identified after a certain pattern of actions emerges (Barbuto, Citation2016; Hax & Majluf, Citation1988).

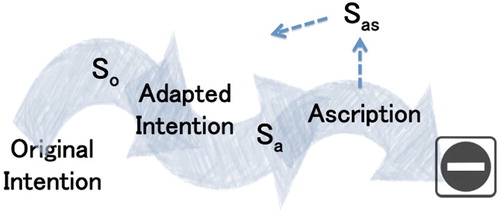

This insight is compatible with social systems theory and organization theory influenced by it (Luhmann, Citation1995; Seidl, Citation2007; Suddaby et al., Citation2013). From that perspective, strategy is always a combination of real intention (a priori) and ascription of intention (after the facts). The ascription of intention (‘this was our plan’) often coincides with an ascription of success (Rap, Citation2006; Schoeneborn, Citation2011; Seidl, Citation2016). Systems theory thus complicates the distinction made by Mintzberg between strategy as plan and emerging strategy, as both dimensions are inextricably part of every set of actions that is considered to be a strategy. De facto, what proponents present as the same thing (the strategy), is a continuous shifting between original intentions, adapted intentions, and ascription of intention. What is recognized in hindsight (ascription) then possibly leads to new strategic episodes and can be a strategy in itself (see ).

Figure 1. An example of a strategy path. An original intention produces a strategy (So), which eventually requires adaptation (Sa). This adaptation partly misses the mark, yet in the new, unexpected, situation, the past is reinterpreted and strategy is ascripted to it in hindsight (Sas). In this example, no new strategic episode occurs afterwards. In other cases, the ascription can engender a new strategic episode.

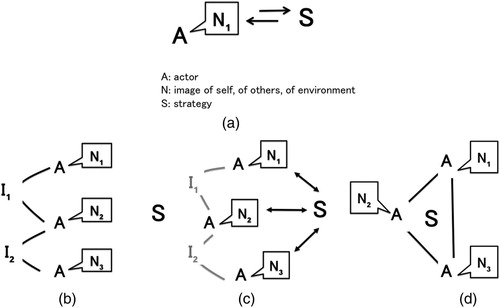

Moving forward from mentioned system theorists, we distinguish between a discursive and institutional dimension, both relevant for the analysis of strategy in governance (Van Assche, Gruezmacher, et al., Citation2020). First of all, a strategy needs to include a narrative of a desirable yet achievable future, which is acceptable for enough actors to coordinate and move forward (cf. Sandercock, Citation1998; Throgmorton, Citation1996; Yanow, Citation2014). Narratives about the future include ideas about the identity of involved actors and expectations about their goals, actions and responses, because a strategy never exists without actors to support and enact it (Forester, Citation1988; Meppem, Citation2000). The link between actors, their identities and their strategies is complex and not neutral (Gunder & Hillier, Citation2009; Mead, Citation1967; Pierre & Peters, Citation2005). An identity is a discursive image of self, others and environment that can inform strategies, be part of a strategy, or be influenced by the strategy (Bragd et al., Citation2008; Seidl, Citation2007; Seidl & Whittington, Citation2014).

Second, strategy in governance will depend and draw on existing institutions and it is likely to result in new institutions at some point (Armitage & Plummer, Citation2010; Beunen et al., Citation2017; Healey, Citation2006). Institutions, as the rules and norms that structure interactions, act as tools for coordination. Policies and plans can be considered complex and composite institutions (Van Assche, Gruezmacher, et al., Citation2020). Existing institutions create and restrict options for strategy development and they can be tools for its realization (Beunen & Patterson, Citation2019; Sehring, Citation2009; Van Assche et al., Citation2014). Most succinctly, one can state that a strategy needs to function as institution to function as strategy in governance, and that, in all but the most elementary cases, it will include and coordinate other institutions.

Once a strategy becomes institutionalized, it can become a coordinative tool with a distinct identity and functioning ascribed to the strategy itself, not only the institutions contained. Just as the strategy ideally integrates and coordinates narratives to the extent that it embodies a new narrative, recognizable as a unity, it coordinates institutions and will function better if it is perceived (and acted upon) as an institution itself (Seidl, Citation2007), See .

Figure 2. Strategy is shaped by narratives held by actors (based on images of self, others and of environment) while strategy can also reshape those narratives (2a). (b–d) illustrate a possible path of strategizing. Actors (A) coordinate actions through institutions (I), as in 2b. A strategy (S) can bring together the actors and their narratives, leading to a fading, a loss of function of the earlier institutions (2c). In 2d we see the strategy (S) replacing these institutions, playing the role of main coordinating institution. In other cases, S can include and coordinate existing institutions.

Reality effects of strategy in and through governance

Governance is by definition a place where diverging and competing interests and interpretations can lead to a multitude of co-existing (latent) strategies, but also to ideas not articulated yet into strategy (Peters & Pierre, Citation1998; cf. Duit & Galaz, Citation2008). Strategy formation in governance thus includes dealing with multiple actors, with non-strategic interpretations, and with already articulated strategies of others. Being surrounded by other actors means being surrounded not only by other intentions and strategies, but also by other observations and interpretations of self and environment, of past, present and future (Barnes et al., Citation2007; Fischer, Citation1993; Luhmann, Citation1990).

When this partly strategic interplay between actors does lead to a shared strategy, to a new plan or policy, the expected effects as expressed in these plans and policies are often overestimated, both by those that develop and present the strategy as well as by a wider audience to which the strategy is presented (McCann, Citation2001). Complexity theory (Chettiparamb, Citation2006; De Roo, Citation2010, Citation2017), the early theorists of implementation (Pressman & Wildavsky, Citation1984), and the Mertonian school in early sociology (Sieber, Citation2013), together with most post- modern and critical versions of public policy and administration (Fischer, Citation1993; Howarth, Citation2010; Miller & Fox, Citation2007), have highlighted the multiplicity of reasons why emerging effects always deviate from expected or anticipated effects. This literature points to the fact that strategies are enacted in a world that is by definition more complex than the model presumed in the strategy. Part of the complexity is that other players anticipate each other’s strategies, the direction of a collective strategy, and after enactment, do not stop strategizing (Etzkowitz et al., Citation2005; Latour, Citation2004; Machiavelli, Citation2009 [1517]). In addition, certain effects might be attributed to strategies only at a later moment in time. All this is a reason for rethinking the relation between strategy and effects.

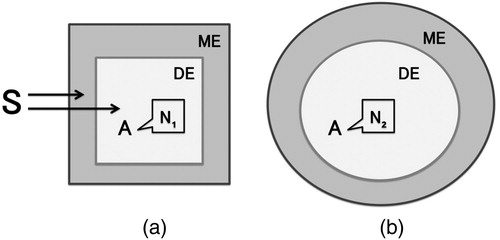

We introduce the concept of reality effects, to refer to the different effects that can be linked to governance strategies in as far as ‘reality’ is redefined (cf. Foucault, Citation2012). Some reality effects have a long lasting impact on communication and action. These can be named structural reality effects. Structural reality effects are not space and time (Weick, Citation2012). They constantly change in relation to other elements and they can vanish at some point in the future. The concept of ‘reality effects’ is not in opposition to fiction or fantasy, but denotes the condition in which some communications alter the world as we know it.

In conceptualizing reality effects, we make a basic distinction between material and discursive effects. Material effects concern changes in the physical environment. Discursive effects refer to changing ways of understanding stemming from the strategy – see (Dean, Citation2010; Luhmann, Citation1989). Concerning the material effects one can add that these matter in governance as reality effects only after they are observed and interpreted, and hence only if their meaning is constructed in social systems (see for a discussion on the relation between discourse and materiality Duineveld et al., Citation2017).

Figure 3. (3a) Reality effects of strategy (S) can alter the discursive environment of an actor (DE), as well as the material environment (ME). These 300 changes (3b) can cause the reality for the actor to be redefined (N1 to N2).

The effect of strategies can be that people start to see the various elements of the world, e.g. objects and subjects, in a different way (Throgmorton, Citation1996; Van Assche et al., Citation2017a). Behavioral change can be an indirect, a second-order effect, and organizational or institutional change can be either a direct effect of strategy (Merkus et al., Citation2019), or also a second-order effect, after ‘reality’ has been redefined by strategy (cf. Bragd et al., Citation2008; Seidl & Whittington, Citation2014). The different types of reality effects can reinforce each other. Such reinforcement can take place within one category of effect (e.g. one crumbling infrastructure enabling the erosion of other materialities and their utility), and between categories (changing narratives in the community undermine compliance with water policies, changing material effects). What is often described as performativity (Cabantous et al., Citation2018; Van Assche, Beunen, & Duineveld Citation2012) focuses on those reality effects that are unintended, that is, where the observer transforms itself accidentally to make the observed fit the intentions of the strategy.

Observation and productive fiction

Strategy is always rooted in observation. In the context of governance, observation is important for strategy in several ways (Seidl & Becker, Citation2005). Strategy rests on observation and the quality of observation correlates with more and more managed reality effects. Building on the insights articulated in the previous section, we can distinguish several forms of observation relevant for strategy:

Observation of self (the strategizing actor) and community, aiming to strategize (Clegg et al., Citation2011; Seidl, Citation2007; Voss et al., Citation2006)

Observation of governance in its current configuration and its path (Healey, Citation2006; Luhmann, Citation1989)

Observation of strategies and reality effects in previous steps in the governance path (Vaara & Lamberg, Citation2016; Van Assche, Gruezmacher, et al., Citation2020).

Observation of relations between governance and external environments, both material and social (Latour, Citation2004; Rasche & Seidl, Citation2017; Voss, Citation2005)

In other words, observation in environmental governance remains important throughout. In strategy formation, the quality of observation of the environment (monitoring of both social and ecological systems) is obviously relevant. Observation of self, environment, and of the effects of self on environment (e.g. how strategies affect the environment) can all combine to inspire better strategy.

Critical management studies (Alvesson et al., Citation2008; Czarniawska, Citation2014), systems theory (Luhmann, Citation1990; Seidl & Becker, Citation2005) and psychoanalysis (Gunder & Hillier, Citation2009) emphasize the link between reflexivity (self-understanding) and external efficiency and success. We add that careful observation of the previous effects of governance on the environment, and previous effects of strategy, have to be included in the repertoire of observations which can be cultivated towards better strategizing, for example to deal better with a particular environmental problem (Van Assche, Gruezmacher, Beunen, et al., Citation2019). Observation of reality effects of strategy links self-observation and external observation in governance.

Most environmental policy and governance literature is acutely aware of the need for environmental monitoring, and of the need to monitor effects of strategies on the environment (Grunwald, Citation2007; Meadowcroft & Steurer, Citation2018). Yet rarely the argument is made for self-observation and for observation of reality effects of strategy, which include discursive effects and the interplay between the discursive and the material. Evolutionary governance theory (EGT) can add a particular mode of self-observation in governance that can help to discern the formation of strategy and its evolving effects: governance path and context mapping (Van Assche et al., Citation2014; Van Assche, Gruezmacher, Beunen, et al., Citation2019). Reconstructing the interplay between strategizing actors and institutions, between power and knowledge, and mapping the rigidities in governance can focus self-observation in such a manner that the formation of particular strategies (and not others) and the creation of certain effects (and not others) become more understandable (Van Assche et al., Citation2014b).

EGT (Van Assche et al., Citation2014) understands rigidities in governance evolution as dependencies, and besides the more traditionally recognized path- and interdependencies (influences of the past and of others) highlights goal dependencies (the broad spectrum of effects of goals on governance itself) and material dependencies (the effects of the material environment, and its changes, on governance itself) (Van Assche, Hornidge, Schlüter, et al., Citation2020). EGT therefore broadens the scope of observation and adds the effects of strategy and the environment on governance itself (besides the more usual observation of governance effects on the environment). Self- observation becomes more complex and more important in this perspective. The EGT perspective can contribute to the further structuring and amplifying of observation, which can serve as input for more promising strategies.

Observation structured in this manner can give a close approximation of the current power of policy and planning to create reality effects, the power dynamics in governance and the effects of external environments on governance (leading to new governance tools and their reality effects). Sharpening of observation is a first strategic priority, to see how a new governance strategy might function as meta- strategy or coordination tool in an environment swarming with other strategies. Analysis then informs strategy, without ever directly producing it (cf. Golsorkhi et al., Citation2010; Seidl, Citation2016). The strategy will always have to result from choices, just as no decision can be reduced to the information or arguments supporting it (Luhmann, Citation1995).

As more critical observers in policy, planning and administration have repeatedly pointed out (as cited above), and also in line with the concept of goal dependencies in EGT, very few strategies (especially in the form of ambitious policies and comprehensive plans) work out exactly as planned. Yet strategies can produce effects in line with what is anticipated. The concept of productive fiction can enrich the understanding of those types of effects. The concept is inspired by Lacanian theory (Gunder & Hillier, Citation2009; Stavrakakis, Citation2019; Žižek, Citation1989). Strategy as narrative imports the features of narrative that is always tinged with fiction, that entails narrative choices and resonances with other narratives (Czarniawska, Citation2014). Stories explain reality, and they create reality, both in the creation of current understandings, which would otherwise have been absent, and in the persuasive character that makes people act towards a particular feature (Sandercock, Citation1998; Yanow, Citation2014). Strategy as narrative is partly fictional for an additional reason: it purports to create a future, based on an understanding of possible futures that are by definition unknowable (Barry & Elmes, Citation1997; Fenton & Langley, Citation2011). The persuasive ambition of strategy needs fiction and it is exactly its fictional character that makes it possible to coordinate action, to create beliefs, and so to bring reality closer to that fiction.

The ‘production’ part of productive fiction refers to all effects of the strategy. Some conditions make it easier for a particular narrative to inspire action and change reality. The narrative might end up in a discursive context or configuration from which it derives plausibility. It might link to other narratives, borrow trusted metaphors, rely on accepted assessments and problem definitions, lean on trusted expertise, embed itself in shared ideologies and link to identity narratives (Chettiparamb, Citation2006; Czarniawska, Citation1997; Van Assche et al., Citation2014). The strategy’s narrative on past, present, on desirable and possible futures can become more persuasive if it fits into such existing discursive configurations, or if it can harness existing opposition against certain narratives, i.e. if it can gain traction through existing counter-narratives. Persuasion does not explain all, of course, and the complex bureaucracies of modern times produce reality effects based on administrative routine just as much as on the base of original intention by leadership (or community) and counter- strategy or obstruction at lower levels (Luhmann, Citation1990; Seidl & Becker, Citation2005).

Dealing with uncertainty: adaptation, transition, intermediates

The careful observation argued for above, can harness resources for strategizing and it can help in optimizing reality effects. Even under the best circumstances, the best crafted strategy cannot create a reality exactly as promised. Even if the resulting reality looks like the original intention, the assessment can differ because of intervening changes in governance and in the values and perspectives of the community at large (Van Assche et al., Citation2012). Often, however, the situation in environmental governance is much tougher, as social-ecological systems are at stake, with systems boundaries rendering observation difficult (De Roo, Citation2017; Van Assche, Verschraegen, Valentinov, et al., Citation2019; Walker et al., Citation2006), with complex systems involved, with distant time horizons, and partial understandings and competing discourses at play (Höglund & Svärdsten, Citation2018). Thus, even if uncertainty is always part of the game, some situations are explicitly recognized and labeled as ‘uncertain’, while other are not (e.g. Grunwald, Citation2007). Often the label ‘uncertainty’ is used when the perceived degree of uncertainty throws sand in the machinery of governance (Renn et al., Citation2011; Stout, Citation2011). In those situations even routine treatment of environmental issues becomes difficult and existing strategies are perceived as not working anymore. Such situation can trigger a new effort at strategizing (perceived need to coordinate and think ahead), and it can raise obstacles for it (Armitage & Plummer, Citation2010; Loorbach, Citation2007).

One way out is to make governance more adaptive. This suggestion has been made in the literature on resilience and social-ecological systems and beyond (Folke et al., Citation2005). Governance can indeed be made more aware of the vulnerability of its routines. It can be made more aware of itself and its environment (see above). This does not mean there is a recipe for adaptive governance. The strategic implications can be diverse. Adaptive governance can be an argument for less strategy (more immediate adaptation), for more strategy (versus reproduction of routines), and for adaptive strategy (Weick, Citation2012). Uncertainty, often caused by poorly understood environmental change and impact, in our view necessitates sharper observation, rethinking coordination, continued efforts to grasp system dynamics and develop long term perspectives. Reflexivity and observation can enhance adaptive capacity, for reasons discussed in previous sections (cf. Voss et al., Citation2006). The structured reflection outlined in EGT, through for example path and context mapping, can reveal existing rigidities in governance evolution, and existing modes of self-transformation.

The medicine of adaptive governance comes with a warning, however. In a real sense, governance is always adapted and adaptive (Duit et al., Citation2010) and the need to perform continuity is much more common than the need to perform conscious adaptation (Barry & Elmes, Citation1997; Czarniawska, Citation2014). The appearance of continuity is functionally necessary to continue coordination in most contexts – it is an aspect of and condition for the productivity of the fiction (akin to what is called de-paradoxification with Luhmann, Citation1995). Working towards adaptive governance, therefore, can better be understood as finding new adaptation mechanisms, combined with insertion of new modes of observation.

In this interpretation, the search for a more or differently adaptive governance can be considered an intermediate strategy. Intermediate strategies are those strategies that are aware of the need for other strategies and of longer term approaches, but are addressing shorter time horizons and/or proximate issues (as opposed to main issues) after careful analysis led to the conclusion that the issues cannot be addressed directly in the given situation. They might involve experiment (Lawrence, Citation2017). Intermediate strategy might also be linked to a situation where analysis suggested that in the given governance configuration, no strategy is likely to come with any real chance of success. In such situations, the conclusion might be to adopt an intermediate strategy of capacity building, of adopting a temporary form of governance, we call transitional governance (Van Assche, Gruezmacher, et al., Citation2020), which understands itself as temporary, as building a new platform from which, later, more ambitious, long term strategies can be created and enacted. The argument for transitional governance can be that the coordinative capacity and expertise are missing in the current governance configuration, to move in a direction already envisioned. It can also be that from the given viewpoint, it is impossible to articulate the substance of a strategy, a more desirable future and a way leading there. Transitional governance can entail the stretching of autonomy, or the building of agency. The aim, then, is for governance to transform itself in such a way that more future options become visible and become possible to act upon.

Conclusion

This paper investigated the potential and limitations of strategy in environmental governance. For that purpose, we reconsidered the concept of strategy in the context of governance. We looked at both emergence and effects of policies and plans (as forms of strategy) and how these are shaped by the context of governance. This mapping of the trajectory of strategizing and the mapping of strategy in layered contexts, was enabled by new insight in strategy borrowed from and building on critical management studies, interpretive policy analysis (highlighting the role of narrative and discourse), systems theory, and evolutionary governance theory (EGT). This broad contextualization of strategy helped to analyze the structure and function of strategy. Structurally, we could understand strategy as both narrative and a set of institutions. Functionally, we could enhance our understanding through broadening the scope of effects of strategy, distinguishing reality effects from other effects, and within reality effects between material and discursive effects. The other effects (institutional, behavioral) could trigger reality effects as a second-order cause. From there, we exposed the utility of targeted observation of governance paths in community context, to underpin analysis and strategizing. Strategy is rooted in observation, of self and environment. Within the realm of self- observation, we argued for a targeted observation of strategy and self-transformation in governance. Mapping of governance paths is a useful frame for such observation to take place and to interpret what has been observed. Tracing reality effects of strategy is pushing observation to cross the boundary of inside and outside, of governance and its social-ecological environment.

To deepen the understanding of reality effects of strategy, we introduced and developed the notion of productive fiction in the context of governance, emphasizing the diverse productivities of strategy and the double need for fiction, stemming from the narrative nature of strategy and its dealings with always unknowable and only partly manageable futures. Realizing a strategy is never fully possible. It has to be fiction because of the internal complexity of governance and the complex relations with various environments (Miller, Citation1986). Yet the fictitious aspect of governance strategy allows it to function and insight in the different aspects of strategy as productive fiction helps to amplify and manage the reality effects of strategy. Strategy is always surrounded by other strategies, by unstable forces, it is reinterpreted, reused and abused.

Understanding strategy in governance is disentangling how seeing, understanding and organizing shape each other. Understanding strategy in environmental governance adds complexity. Besides the host of urgent and complex environmental issues adding urgency and complexity, there is the importance of the ecological, and in a broader sense, material environment for governance and strategy. Indeed, it becomes paramount to trace the understandings of material environments within governance, entrenched concepts, discourses, narratives on the environment, existing coordinative capacity to affect material environments, and the modes of self-transformation, revealing how the previous features might be changed. Such environmental governance strategy moreover has to take into account the mutual shaping of governance and environment: indeed, reality effects include material effects, observed and unobserved within governance, but there are also the material dependencies in governance evolution, the effects of human-made and natural materialities on governance. Grasping this entanglement in a particular governance path can unveil limits and possibilities of steering, as well as possible substance, or content, of a strategy.

We presented finally the concepts of adaptation, intermediate strategy and transitional governance for situations when formulation or implementation of strategy is difficult, when it might be impossible to see a desirable future or when it is difficult to find a way to move in a desired direction. Uncertainty and adaptation might always be there, but that does not detract from the reality of thresholds of complexity and rigidity which can bring governance to a grinding halt or amplify its negative effects on the environment.

For future research in environmental governance, the perspective on strategy in governance presented here can have several implications. First of all, it might be worthwhile to reinterpret existing studies on a particular policy, or plan, through this lens. This can help to test and further develop the perspective. It could also inspire research trying to discern how insights can be carried over between policy domains (water, land, forestry etc.) and between environmental issues (strategies for pollution, for climate change). Second, the proposed location of strategy in a perspective linking seeing, understanding and organizing might be able to give new impetus to a re-linking of existing approaches, including interpretive policy analysis and institutionalism. In addition, the approach might embody a warning against formulaic solutions for environmental problems, solutions championing one method of analysis, one discourse, one form of governance, one expert hierarchy, or one mode of strategizing. If there are two things recent strategy research can tell us, it is precisely that strategy is context- sensitive and that even if adapted to context, the results of strategizing are never entirely predictable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Kristof Van Assche, Currently Full Professor (since 2016) in planning, governance and development at the University of Alberta and also affiliated with Bonn University, Center for Development Research (ZEF) as Senior Fellow and with Memorial University, Newfoundland, Harris Centre for Regional Policy, as Research Fellow. Before coming to Alberta (in 2014) he worked at Bonn University (ZEF) as Senior Researcher, Minnesota State University (St Cloud), as Associate Professor, and Wageningen University, as Assistant Professor. He is interested in evolution and innovation in governance, with focus areas in spatial planning and design, development and environmental policy. He has worked in various countries, often combining fieldwork with theoretical reflection: systems theories, interpretive policy analysis, institutional economics, post- structuralism and others. Together with some colleagues he has developed Evolutionary Governance Theory (EGT), which aims to discern realistic modes of transition and reform, between social engineering and laissez faire.

Raoul Beunen is Associate Professor of Environmental Governance at the Open University, the Netherlands. His research explores the potentials and limitations of environmental policy and planning in the perspective of adaptive governance and sustainability. It focuses on innovation and evolution in governance, paying attention to the dynamics of policy implementation and integration, multi-level governance, stakeholder involvement, and the performance of institutional structures.

Monica Gruezmacher has a PhD from the Center for Development Studies at the University of Bonn and is currently an Assistant Lecturer at the University of Alberta. She has been particularly interested in human-nature interactions; studying ways in which social changes bring about changes in the use and management of natural resources. For the past years she has been exploring the challenges of planning for long-term sustainability in rural communities of Western Canada and Newfoundland but has had also substantial experience in the Amazon region (particularly in Colombia where she is originally from).

Martijn Duineveld is Associate Professor at the Cultural Geography Group Wageningen University. His research programme is named Urban Governance and the Politics of Planning and Design. He is co-founder and active contributor to the emerging body of literature on Evolutionary Governance Theory. Martijn has been involved in many international research and consultancy projects situated in Argentina, Uganda, Georgia and Russia. He also studies urban fringes and cities in the Netherlands (The Bulb region (2005-2010), Groningen (2010-2012) and Arnhem (2013-2018). In these cases, he explores the power interplays between local politicians, planners, designers, project developers and citizens. On a more conceptual level his research is focused on three themes: 1. Democratic innovation in Urban Governance. 2. Conflicts and Power in Urban Governance. 3. Materiality and object formation in Urban Governance. In addition to the extensive list of academic publications, his studies have been published in innovative ways, speaking to academia and the broader public, including film-making, newspaper articles, and local news blogs.

References

- Albrechts, L. (2004). Strategic (spatial) planning reexamined. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 31(5), 743–758. https://doi.org/10.1068/b3065

- Alvesson, M., & Ashcraft, K. L. (2009). Critical methodology in management and organization research. In A. Bryman & D. Buchanan (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational research methods (pp. 61–77). SAGE Publications.

- Alvesson, M., Bridgman, T., & Willmott, H. (eds.). (2009). The Oxford handbook of critical management studies. Oxford Handbooks.

- Alvesson, M., Hardy, C., & Harley, B. (2008). Reflecting on reflexivity: Reflexive textual practices in organization and management theory. Journal of Management Studies, 45(3), 480–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00765.x

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2017). Collaborative platforms as a governance strategy. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 28(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mux030

- Aristotle, D. A. (2015). [4th C BC] politics. Aeterna Press.

- Armitage, D., & Plummer, R. (2010). Adapting and transforming: Governance for navigating change. In Adaptive capacity and environmental governance (pp. 287–302). Springer.

- Barbuto, J. E., Jr. (2016). How is strategy formed in organizations? A multi-disciplinary taxonomy of strategy-making approaches. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 3(1), 822.

- Barnes, M., Newman, J., & Sullivan, H. C. (2007). Power, participation and political renewal: Case studies in public participation. Policy Press.

- Barry, D., & Elmes, M. (1997). Strategy retold: Toward a narrative view of strategic discourse. Academy of Management Review, 22(2), 429–452. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9707154065

- Bell, S., & Hindmoor, A. (2009). Rethinking governance: The centrality of the state in modern society. Cambridge University Press.

- Beunen, R., & Patterson, J. J. (2019). Analysing institutional change in environmental governance: Exploring the concept of ‘insti- tutional work’. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(1), 12–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2016.1257423

- Beunen, R., Patterson, J., & Van Assche, K. (2017). Governing for resilience: The role of institutional work. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 28, 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.04.010

- Bevir, M., & Rhodes, R. A. (eds.). (2015). Routledge handbook of interpretive political science. Routledge.

- Bevir, M., & Rhodes, R. A. (eds.). (2016). Rethinking governance: Ruling, rationalities and resistance. Routledge.

- Biermann, F., Kanie, N., & Kim, R. E. (2017). Global governance by goal-setting: The novel approach of the UN Sustainable development goals. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 26–27, 26–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.010

- Bloom, A., & Kirsch, A. (2016). The republic of Plato. Basic Books.

- Bodin, Ö. (2017). Collaborative environmental governance: Achieving collective action in social-ecological systems. Science, 357(6352), eaan1114. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan1114

- Bragd, A., Christensen, D., Czarniawska, B., & Tullberg, M. (2008). Discourse as the means of community creation. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 24(3), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2008.02.006

- Brindley, T., Rydin, Y., & Stoker, G. (2005). Remaking planning: The politics of urban change. Routledge.

- Bryson, J. M., Edwards, L. E., & Van Slyke, D. M. (2018). Getting strategic about strategic planning research. Public Management Review, 20(3), 317–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1285111

- Cabantous, L., Gond, J. P., & Wright, A. (2018). The performativity of strategy: Taking stock and moving ahead. Long Range Planning, 51(3), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.03.002

- Chettiparamb, A. (2006). Metaphors in complexity theory and planning. Planning Theory, 5(1), 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095206061022

- Clegg, S. R., Carter, C., Kornberger, M., & Schweitzer, J. (2011). Strategy: Theory and practice. Sage Publications.

- Cooke, B., & Kothari, U. (eds.). (2001). Participation: The new tyranny? Zed books.

- Czarniawska, B. (1997). Narrating the organization: Dramas of institutional identity. University of Chicago Press.

- Czarniawska, B. (2014). A theory of organizing. Edward Elgar.

- Dean, M. (2010). Governmentality: Power and rule in modern society. Sage publications.

- De Roo, G. (2010). Being or becoming? That is the question! Confronting complexity with contemporary planning theory. A planner’s encounter with complexity. In G. De Roo, & E. Silva (Eds.), A planners encounter with complexity (pp. 19–40). Ashgate.

- De Roo, G. (2017). Integrating city planning and environmental improvement: Practicable strategies for sustainable urban development. Routledge.

- Duineveld, M., Van Assche, K., & Beunen, R. (2017). Re-conceptualising political landscapes after the material turn: A typology of material events. Landscape Research, 42(4), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2017.1290791

- Duit, A., & Galaz, V. (2008). Governance and complexity—emerging issues for governance theory. Governance, 21(3), 311–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2008.00402.x

- Duit, A., Galaz, V., Eckerberg, K., & Ebbesson, J. (2010). Governance, complexity, and resilience. Global Environmental Change.

- Eriksson, P., & Lehtimäki, H. (2001). Strategy rhetoric in city management: How the presumptions of classic strategic management live on? Scandinavian Journal of Management, 17(2), 201–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0956-5221(99)00029-9

- Etzkowitz, H., de Mello, J. M. C., & Almeida, M. (2005). Towards ‘meta-innovation’ in Brazil: The evolution of the incubator and the emergence of a triple helix. Research Policy, 34(4), 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.01.011

- Feindt, P. H., & Weiland, S. (2018). Reflexive governance: Exploring the concept and assessing its critical potential for sustainable development. Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 20(6), 661–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2018.1532562

- Fenton, C., & Langley, A. (2011). Strategy as practice and the narrative turn. Organization Studies, 32(9), 1171–1196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840611410838

- Fischer, F. (1993). Citizen participation and the democratization of policy expertise: From theoretical inquiry to practical cases. Policy Sciences, 26(3), 165–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00999715

- Flyvbjerg, B. (1998). Rationality and power: Democracy in practice. University of Chicago press.

- Folke, C., Hahn, T., Olsson, P., & Norberg, J. (2005). Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 30(1), 441–473. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511

- Forester, J. (1988). Planning in the Face of power. Univ of California Press.

- Foucault, M. (2012). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Vintage.

- Freedman, L. (2015). Strategy: A history. Oxford University Press.

- Golsorkhi, D., Rouleau, L., Seidl, D., & Vaara, E. (2010). Cambridge handbook of strategy as practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Grotenbreg, S., & Van Buuren, A. (2017). Facilitation as a governance strategy: Unravelling governments’ facilitation frames. Sustainability, 9(1), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9010160

- Grunwald, A. (2007). Working towards sustainable development in the face of uncertainty and incomplete knowledge. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 9(3–4), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080701622774

- Gunder, M., & Hillier, J. (2009). Planning in ten words or less: A Lacanian entanglement with spatial planning. Ashgate.

- Hax, A. C., & Majluf, N. S. (1988). The concept of strategy and the strategy formation process. Interfaces, 18(3), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1287/inte.18.3.99

- Healey, P. (2006). Transforming governance: Challenges of institutional adaptation and a new politics of space. European Planning Studies, 14(3), 299–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310500420792

- Hendriks, C. M., & Grin, J. (2007). Contextualizing reflexive governance: The politics of Dutch transitions to sustainability. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 9(3–4), 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080701622790

- Hertin, J., & Berkhout, F. (2003). Analysing institutional strategies for environmental policy integration: The case of EU enterprise policy. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 5(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080305603

- Hillier, J. (2002). Shadows of power: An allegory of prudence in land-use planning. Routledge.

- Höglund, L., & Svärdsten, F. (2018). Strategy work in the public sector—A balancing act of competing discourses. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 34(3), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2018.06.003

- Howarth, D. (2010). Power, discourse, and policy: Articulating a hegemony approach to critical policy studies. Critical Policy Studies, 3(3–4), 309–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171003619725

- Imperial, M. T. (2005). Using collaboration as a governance strategy: Lessons from six watershed management programs. Administration & Society, 37(3), 281–320.

- Jarzabkowski, P. (2004). Strategy as practice: Recursiveness, adaptation, and practices-in-use. Organization Studies, 25(4), 529–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840604040675

- Kagan, K. (2006). Redefining Roman grand strategy. The Journal of Military History, 70(2), 333–362. https://doi.org/10.1353/jmh.2006.0104

- Kornberger, M., & Engberg-Pedersen, A. (2019). Reading Clausewitz, reimagining the practice of strategy. Strategic Organization. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127019854963

- Latour, B. (2004). Politics of nature. Harvard University Press.

- Lawrence, A. (2017). Adapting through practice: Silviculture, innovation and forest governance for the age of extreme uncertainty. Forest Policy and Economics, 79, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2016.07.011

- Lindseth, G. (2005). Local level adaptation to climate change: Discursive strategies in the Norwegian context. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 7(1), 61–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080500251908

- Loorbach, D. (2007). Transition management. New mode of governance for sustainable development. International Books.

- Luhmann, N. (1989). Ecological communication. University of Chicago Press.

- Luhmann, N. (1990). Political theory in the welfare state. Walter de Gruyter.

- Luhmann, N. (1995). Social systems. Stanford University Press.

- Machiavelli, N. (2009 [1517]). Discourses on Livy. University of Chicago Press.

- McCann, E. J. (2001). Collaborative visioning or urban planning as therapy? The politics of public-private policy making. The Professional Geographer, 53(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-0124.00280

- Mead, G. H. (1967). Mind, self and society. University of Chicago Press.

- Meadowcroft, J., & Steurer, R. (2018). Assessment practices in the policy and politics cycles: A contribution to reflexive governance for sustainable development? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 20(6), 734–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2013.829750

- Meppem, T. (2000). The discursive community: Evolving institutional structures for planning. Ecological Economics, 34(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00151-8

- Merkus, S., Willems, T., & Veenswijk, M. (2019). Strategy implementation as performative practice: Reshaping organization into Alignment with strategy. Organization Management Journal, 16(3), 140–155.

- Miller, D. (1986). Configurations of strategy and structure: Towards a synthesis. Strategic Management Journal, 7(3), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250070305

- Miller, H. T., & Fox, C. J. (2007). Postmodern public administration. M.E. Sharpe.

- Mintzberg, H. (1978). Patterns in strategy formation. Management Science, 24(9), 934–948. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.24.9.934

- Neugebauer, F., Figge, F., & Hahn, T. (2016). Planned or emergent strategy making? Exploring the formation of corporate sustainability strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 25(5), 323–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1875

- Peters, B. G., & Pierre, J. (1998). Governance without government? Rethinking public administration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 8(2), 223–243. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024379

- Pierre, J. (ed.). (2000). Debating governance: Authority, steering, and democracy. OUP.

- Pierre, J., & Peters, B. (2005). Governing complex societies: Trajectories and scenarios. Palgrave.

- Pierre, J., & Peters, B. G. (2019). Governance, politics and the state. Red Globe Press.

- Pierson, P. (2000). The limits of design: Explaining institutional origins and change. Governance, 13(4), 475–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00142

- Pressman, J. L., & Wildavsky, A. (1984). Implementation: How great expectations in Washington are dashed in Oakland. University of California Press.

- Rap, E. (2006). The success of a policy model: Irrigation management transfer in Mexico. The Journal of Development Studies, 42(8), 1301–1324. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380600930606

- Rasche, A., & Seidl, D. (2017). A Luhmannian perspective on strategy: Strategy as paradox and meta-communication. Critical Perspectives on Accounting.

- Renn, O., Klinke, A., & Van Asselt, M. (2011). Coping with complexity, uncertainty and ambiguity in risk governance: A synthesis. Ambio, 40(2), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-010-0134-0

- Sandercock, L. (ed.). (1998). Making the invisible visible: A multicultural planning history (Vol. 2). University of California Univ of California Press.

- Schoeneborn, D. (2011). Organization as communication: A Luhmannian perspective. Management Communication Quarterly, 25(4), 663–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318911405622

- Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press.

- Scott, T. A., & Thomas, C. W. (2017). Unpacking the collaborative toolbox: Why and when do public managers choose collaborative governance strategies? Policy Studies Journal, 45(1), 191–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12162

- Sehring, J. (2009). Path dependencies and institutional bricolage in post-Soviet water governance. Water Alternatives, 2, 1.

- Seidl, D. (2007). General strategy concepts and the ecology of strategy discourses: A systemic-discursive perspective. Organization Studies, 28(2), 197–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840606067994

- Seidl, D. (2016). Organisational identity and self-transformation: An autopoietic perspective. Routledge.

- Seidl, D., & Becker, K. H. (eds.). (2005). Niklas Luhmann and organization studies. Liber.

- Seidl, D., & Whittington, R. (2014). Enlarging the strategy-as-practice research agenda: Towards taller and flatter ontologies. Organization Studies, 35(10), 1407–1421. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840614541886

- Sieber, S. (2013). Fatal remedies: The ironies of social intervention. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Stavrakakis, Y. (ed.). (2019). Routledge Handbook of Psychoanalytic political theory. Routledge.

- Stout, L. A. (2011). Uncertainty, dangerous optimism, and speculation: An inquiry into some limits of democratic governance. Cornell Law Review, 97, 1177. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/clqv97&i=1199

- Suddaby, R., Seidl, D., & Lê, J. K. (2013). Strategy-as-practice meets neo-institutional theory. Strategic Organization, 11(3), 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127013497618

- Tadajewski, M., Maclaran, P., & Parsons, E. (eds.). (2011). Key concepts in critical management studies. Sage.

- Throgmorton, J. A. (1996). Planning as persuasive storytelling: The rhetorical construction of Chicago’s electric future. University of Chicago Press.

- Torgerson, D. (2018). Reflexivity and developmental constructs: The case of sustainable futures. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 20(6), 781–791. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2013.817949

- Vaara, E., & Lamberg, J. A. (2016). Taking historical embeddedness seriously: Three historical approaches to advance strategy process and practice research. Academy of Management Review, 41(4), 633–657. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0172

- Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., & Duineveld, M. (2012). Performing success and failure in governance: Dutch planning experiences. Public Administration, 90(3), 567–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01972.x

- Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., & Duineveld, M. (2014). Evolutionary governance theory: An introduction. Springer.

- Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., & Duineveld, M. (2016). Citizens, leaders and the common good in a world of necessity and scarcity: Machiavelli’s lessons for community-based natural resource management. Ethics. Policy & Environment, 19(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/21550085.2016.1173791

- Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., Duineveld, M., & Gruezmacher, M. (2017a). Power/knowledge and natural resource management: Foucaultian foundations in the analysis of adaptive governance. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 19(3), 308–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2017.1338560

- Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., Gruezmacher, M., Duineveld, M., Deacon, L., Summers, R., Halstrom, L., & Jones, K. (2019). Research methods as bridging devices: Path and context mapping in governance. Journal of Organizational Change Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-06-2019-0185

- Van Assche, K., Duineveld, M., & Beunen, R. (2014b). Power and contingency in planning. Environment and Planning A, 46(10), 2385–2400. https://doi.org/10.1068/a130080p

- Van Assche, K., Gruezmacher, M., & Deacon, L. (2020). Land use tools for tempering boom and bust: Strategy and capacity building in governance. Land Use Policy, 93, 103994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.05.013

- Van Assche, K., Hornidge, A.-K., Schlüter, A., & Vaidianu, N. (2020). Governance and the coastal condition: Towards new modes of observation, adaptation and integration. Marine Policy, 112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.01.002

- Van Assche, K., Verschraegen, G., Valentinov, V., & Gruezmacher, M. (2019). The social, the ecological, and the adaptive. Von Bertalanffy’s general systems theory and the adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 36(3), 308–321. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2587

- Vasquez, J. A. (1998). The power of power politics: From classical realism to neotraditionalism (No. 63). Cambridge University Press.

- Voss, J. P. (2005). Strategic management from a systems-theoretical perspective. In D. Seidl & K. H. Becker (Eds.), Niklas Luhmann and organization studies (Vol. 14, pp. 363–383). Liber.

- Voss, J. P., Bauknecht, D., & Kemp, R. (eds.). (2006). Reflexive governance for sustainable development. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Voss, J. P., Newig, J., Kastens, B., Monstadt, J., & Nölting, B. (2007). Steering for sustainable development: A typology of problems and strategies with respect to ambivalence, uncertainty and distributed power. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 9(3– 4), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080701622881

- Walker, B., Gunderson, L., Kinzig, A., Folke, C., Carpenter, S., & Schultz, L. (2006). A handful of heuristics and some propositions for understanding resilience in social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 11(1), 13.

- Walker, G., & Shove, E. (2007). Ambivalence, sustainability and the governance of socio-technical transitions. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 9(3–4), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080701622840

- Weick, K. E. (2012). Making sense of the organization, Vol 2: The impermanent organization (Vol. 2). Wiley.

- Whittington, R. (1996). Strategy as practice. Long Range Planning, 29(5), 731–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(96)00068-4

- Yanow, D. (2014). Interpretive analysis and comparative research. In Comparative policy studies (pp. 131–159). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Žižek, S. (1989). The sublime object of ideology. Verso.