ABSTRACT

Sustainable agriculture implies trade-offs with farm animal welfare. Proposals to increase agricultural productivity and ecological sustainability alike, are often linked to intensification, which may restrict animal welfare. Despite the growing importance of farm animal welfare for the alignment of agricultural and environmental policy, determinants of decision-making at the EU level remain unexplored. This article contributes to closing this research gap, broadening our understanding of why policymakers vote for the enactment of animal welfare policies. Applying the Social Identities in the Policy Process (SIPP) perspective we highlight the role of group membership for individual decision-making. By means of a quantitative analysis of voting behaviour in the European Parliament on two animal welfare policies, we show that different identities are salient. The strongest predictor is political group membership. In case of defections from the group line, the salience of national, sectoral and also demographic identities adds to the understanding of decision-making.

Introduction

Agricultural policies are in transition: new actors are entering the traditionally closed policy field, emphasizing environmental sustainability (Daugbjerg & Feindt, Citation2017; Daugbjerg & Swinbank, Citation2012; Schwindenhammer, Citation2017; Tosun, Citation2017). In this context farm animal welfare is receiving increasing societal and political attention (Cornish et al., Citation2016; Rooij et al., Citation2010; Vogeler, Citation2019). Proposals to increase agricultural productivity and ecological sustainability alike, are often linked to intensification (Strohbach et al., Citation2015). In livestock farming, intensification has reached its heights, the majority of animals is raised in indoor-housing systems with only minimum space available to increase economies of scale (Grethe, Citation2017). Whereas these systems may require less land use, and breeding progress and optimized feeding have led to a better feed utilization, they often severely restrict animal welfare (European Court of Auditors, Citation2018; Buller et al., Citation2018; Harvey & Hubbard, Citation2013). The European Union recognizes animals as sentient beings (EUR-Lex, Citation2007). Declaring animals as sentient beings and offering them state protection – in some member states animals are protected by the constitution – turns animal welfare into a public good (Vogeler, Citation2017). This implies that policymakers cannot neglect animal welfare in favour of ecological sustainability, instead, ecological sustainability and animal welfare are increasingly connected (FAWC, Citation2016; Lever & Evans, Citation2016).

Despite this importance, determinants of decision-making in farm animal welfare at the EU level remain unexplored. By applying hypotheses derived from the Social Identities in the Policy Process (SIPP) perspective (Hornung et al., Citation2019), we provide a quantitative analysis of voting on two farm animal welfare policies in the European Parliament (EP) during the 8th term. Research on voting behaviour in the EP has identified partisan politics, personal ideological beliefs, and national preferences as explanatory variables (Hix, Citation2002, Citation2008). Drawing on the SIPP perspective, we propose that social group membership enhances these explanatory arguments. SIPP assumes that policy actors act in accordance with their salient social identity (Hornung et al., Citation2019). We analyse two highly controversial votes in comparison: the vote on the protection of animals during transport (Parliament, Citation2019) and the vote on the protection of farm rabbits (Parliament, Citation2017b). Empirically, our results provide first insights into the determinants of farm animal welfare policymaking at the EU level. Theoretically, they contribute to the research on voting behaviour and the empirical testing of SIPP hypotheses.

Farm animal welfare and sustainable agriculture – trade-offs, opportunities, and risks

Intensification in livestock farming is partly achieved at the expense of the welfare and health of farmed animals (Grethe, Citation2017). While there is an apparent negative trade-off between animal welfare and ecological sustainability, animal welfare may likewise present an opportunity in view of its salience that is often closely interrelated with other sustainability concerns (Cornish et al., Citation2016; Rooij et al., Citation2010; Veissier et al., Citation2008). Environmental issues are increasingly connected to changes in consumer behaviour that influence agricultural production (Greer, Citation2017; Pollex, Citation2017; Whitley et al., Citation2018). In representative surveys, Europeans name animal welfare as a main priority of agricultural production (Commission, Citation2018). Following the Eurobarometer on animal welfare, the majority agrees to reduce subsidies for farmers in case of non-compliance with animal welfare standards. 82% of Europeans believe that farmed animals should be better protected, more than half of them would be prepared to pay more for products from animal welfare-friendly production. The public attention for animal welfare is generally higher in North-Western EU member states and lower in Southern and Eastern Europe (Commission, Citation2016). This salience provides important leverages for policymakers, e.g. by labelling animal products according to housing systems (Parker et al., Citation2017). Eco-labels have been introduced in other areas as an instrument to promote sustainability (Daugbjerg et al., Citation2014). The connection between animal welfare and environmental protection is likewise apparent in party politics. Green parties, with environmental policy as core issue, are the ones that emphasize animal welfare most (Vogeler, Citation2019). Animal welfare is thereby becoming an important dimension of environmental policymaking.

As a reaction, policymakers in many European countries have passed species-specific policies to protect farmed animals, though there is large variation between EU member states (Spoolder et al., Citation2011; Vogeler, Citation2019). Also, the issue has moved to the supranational level, in particular the EU, being an important body of multilevel governance (Thomann et al., Citation2019). The EU began to protect farmed animals in the 1970s by community law in slaughterhouses and during transport. (European Court of Auditors, Citation2018; Commission, Citation2014). In 2007, animals were recognized as sentient beings in the Treaty of Lisbon (EUR-Lex, Citation2007). In addition to improving animal welfare, the policies aim to harmonize production systems to enable free trade in the common marke. The intensification of animal production has resulted in confinement practices, such as battery cages for hens and single crates for calves, that cause suffering and health problems (Grethe, Citation2017; Lusk & Norwood, Citation2011; Yeates, Citation2018). As an answer, the EU passed specific directives for laying hens (1999), for chickens kept for meat production (2007), for calves kept for farming purposes (2009), and for pigs kept for rearing and fattening (2009) (European Court of Auditors, Citation2018; Commission, Citation2014).

First hypotheses have been presented for the design of farm animal welfare policies at the national level. These include partisan politics, public salience, and agro-structural conditions as explanatory variables (Bennett & Appleby, Citation2010; Lundmark et al., Citation2014; Schmid & Kilchsperger, Citation2010; Vogeler, Citation2019, Citation2020). However, there is neither a systematic analysis of voting patterns, nor are there large n studies that compare policymaking in EU member states. With this article, we intend to deepen the understanding of why EU policymakers decide to promote animal welfare legislation.

Selection of cases

We searched all parliamentary votes in the field of animal welfare and protection in the 8th term of the EP (2014-2019). Out of the five votes related to agriculture, two were almost consensual which is why they were excluded here. Three votes were less consensual. One of the votes concerned the cloning of animals for farming purposes. Given the strong ethical dimension of cloning, we consider this decision as inadequate for the understanding of voting on farm animal welfare. The first vote we selected, concerns the better protection of animals during transport (Parliament, Citation2019): one-third of Members of the European Parliamen (MEPs) voted against the policy or abstained and only 74% voted along party lines. The background of the proposal is the insufficient implementation of Council Regulation No 1/2005 on the protection of animals during transport within and outside the EU. The EP laments implementation failures and insufficient controls in the member states. These deficits were pointed out by the European Court of Auditors, additional pressure was generated by the Citizen Campaign #StopTheTrucks which collected over 1 million signatures for an end of long-distance transports (European Court of Auditors, Citation2018; Parliament, Citation2019).

The second vote is a proposal to introduce binding minimum standards for farmed rabbits. Over 40% of MEPs voted against it or abstained and only 82% voted along party lines. Rabbits are the second-most farmed species in the EU with more than 340 million rabbits slaughtered every year. Farming is highly concentrated in three member states: Spain, France and Italy together account for over 80% of production (Commission, Citation2017; EFSA, Citation2005). None of the three countries has passed legislation on how to breed or rear rabbits (Commission, Citation2017). In 2005, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) published a report, concluding that production practices are associated with poor animal welfare. The peculiarity of the vote on farm rabbits resides in it being an own-initiative procedure of the EP, meaning that the EP itself took the initiative to propose draft legislation to the European Commission (EC). In 2017, the EC replied to the EP’s resolution arguing that it would favour national instead of EU policies given the regional concentration of rabbit farming. The selected votes will be analysed in comparison to explore why individual MEPs vote for or against the enactment of farm animal welfare policies.

Social identities and voting behaviour in the European Parliament

Political scientists have engaged intensively with the voting behaviour of MEPs. Theoretically, the literature is dominated by approaches which explain individual voting behaviour as motivated by vote-seeking, policy-seeking, or office-seeking (Bowler & Farrell, Citation1995; Costello & Thomson, Citation2016; Engler & Zohlnhöfer, Citation2018; Hix & Høyland, Citation2014; Mühlbock, Citation2012). The chance of getting re-elected is influenced by national parties as well as by differences in electoral systems and particularly by the existence of open- or closed-list systems in the member states (Hix, Citation2004). To pursue specific policy goals at the EU level, MEPs form political groups along ideological lines. The literature identifies two important policy dimensions in the EP: the first concerns the left-right cleavage and the second relates to the party’s positioning on the degree of EU integration (Hix et al., Citation2006). The environmental dimension within the EP is less pronounced given the smaller share of seats of green parties in the 8th term of the EP (McElroy & Benoit, Citation2011). Political groups in the EP have the power to control offices, e.g. the appointment of rapporteurship or committee assignment. This creates incentives to follow the position of the political group (Bowler & Farrell, Citation1995; Roger & Winzen, Citation2015). The careers of MEPs are influenced by their national parties. From this, the hypotheses have been derived that voting is determined by political group membership on the one hand and by national party affiliation on the other hand. In contrast to these assumptions, Ringe argues that MEPs do not necessarily make informed decisions on each policy proposal, considering the large number of votes in the EP (Ringe, Citation2010). The high cohesion within political groups is explained by the fact that MEPs follow expert colleagues in their decisions in policy fields about which they know little or have no opinion on (Ringe, Citation2010).

To sum up, there is a broad body of empirical research that offers explanations for the cohesion within political groups. The more challenging question is why, in some cases, MEPs choose not to be loyal to their political group. Costello and Thomson highlight the importance of national positions in some policy decisions (Costello & Thomson, Citation2016). Mühlbock and Tosun show that national interests may be an important predictor of voting behaviour and that these may change over time depending on the governing coalition or changes in public opinion (Mühlbock & Tosun, Citation2018). We propose that the Social Identities in the Policy Process (SIPP) perspective poses a valuable extension by adding further explanatory variables and by simultaneously integrating the existing research findings. In addition to political group membership and nationality, SIPP allows for the integration of sectoral, demographic, and informal characteristics of MEPs. SIPP transfers the Social Identity Theory (SIT) (Tajfel, Citation1982) and the Self-Categorization Theory (SCT) (Turner et al., Citation1987) to the policy process and brings into focus the importance of social group membership for decision-making. The main assumption is that political actors possess several social identities that coexist in the policy subsystem. Hornung et al. propose that the salience of one of the potentially conflicting identities determines the behaviour of actors within a policy subsystem and regarding a specific policy decision (Hornung et al., Citation2019). Actors take decisions according to different identities that will be dominant at different points in time and under specific circumstances. Individual preferences and behaviour are guided by social identities shaped by the membership in social groups. SIPP thereby offers the opportunity to understand why individuals’ behaviour (e.g. voting in our case) is dependent upon different factors under different circumstances. Instead of simply combing different variables that statistically contribute to voting behaviour, the perspective provides an explanation for the different impact of similar group membership on the voting behaviour of different MEPs. While in some cases party membership explains the vote, other decisions (and decisions of other MEPs) are oriented towards other social identities. According to social psychological research, which social identity is salient in which context is determined by how well a given social identity ‘fits’ the context and issue at hand, also with respect to how other individuals are perceived as group members in this given situation (Oakes et al., Citation1991). Certain issues can trigger the salience of certain identities (Transue, Citation2007) – in the case under study here, this primarily concerns the possibility that decisions on animal welfare trigger the salience of party membership for MEPs belonging to the Greens, while for other party members, the issue might trigger another social identity, such as a national or sectoral identity. Finally, social identities are more likely to be salient if the social identification with a given group is strong, measured by the strength of the feeling of belonging as well as the evaluative and emotional assessment of an individual towards the group and fostered by long-term membership and frequent contact to other group members (Haslam et al., Citation2011).

With a view to the policy process, five social identities are relevant: organizational identities (Cole & Bruch, Citation2006), which include partisan identity or interest organization membership; sectoral identities (Hassenteufel et al., Citation2010) concerning policy sectors; local identities (Bonaiuto et al., Citation2002) concerning geography as well as levels of political decision; demographic identities (Béland, Citation2017), including demographic characteristic and eventually biographic elements; and lastly informal identities (Walsh, Citation2004) among which programmatic groups are a special case (Hornung & Bandelow, Citation2020).

At the EU level we argue that the local identity is best characterized by the nationality of the Member of the European Parliament. At the national level the local identity could be operationalized by federal, regional, or city level depending on the case. By claiming issue ownership for a certain policy field, political groups strengthen the emotional bond within their group, e.g. in the case of environmental protection for green parties. When parties do not claim issue ownership, other identities, particularly the national and sectoral identities, will come into play. The demographic identity will most likely only be salient in a small number of policy fields, e.g. relating to gender issues. Finally, informal identities can be salient in the policy process. However, these informal identities can hardly be captured by means of quantitative statistical analysis and should be integrated by means of qualitative methods in future studies.

For our case study, we firstly expect that the national (=local) identity of a MEP can be triggered if there are national peculiarities with regard to the respective policy. To operationalize national identities, we collected context variables for each case: In the case of the transportation policy, we assume that the national identity can be triggered if the country has a significant livestock sector and a high export share of agricultural products due to the higher costs associated with improving transportation standards (data taken from (Commission, Citation2020)). In this case, the MEP is more likely to vote against the transportation policy (H1a)

In the case of rabbit farming we assume that the national identity might be triggered if either his or her country is involved with major commercial rabbit farming or if his or her country already has legislation for rabbit farming in place. We assume that MEPs are more likely to vote against rabbit protection if they come from a country with major rabbit production (H1b). Secondly, we hypothesize that MEPs from countries that have already passed national legislation on rabbit farming will be more likely to vote for rabbit protection at the EU level to achieve a harmonization and reduce national disadvantages (H1c).

Secondly, the sectoral identity is regarded: we measure this by committee membership. Following the literature on the dominance of exceptional goals in the Common Agricultural Policy (Daugbjerg & Feindt, Citation2017; Daugbjerg & Swinbank, Citation2012; Tosun, Citation2017), we assume that MEPs who are a member of the Committee of Agriculture are more likely to vote against animal welfare policies (H2a). Secondly, we expect to see a connection between environmental and animal welfare goals (Vogeler, Citation2019) and expect members of the Committee of Environment to vote for animal welfare policies (H2b).

The organizational identity is included in the analysis, its criterion being membership to a political group within the EP. We searched the manifestos and webpages of the political groups regarding their positioning on animal welfare and agricultural policy. Departing from these findings we assume that MEPs belonging to the Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA) or to the Confederal Group of the European United Left – Nordic Green Left (GUE-NGL) are more likely to vote for animal welfare (H3a). Integrating ‘Green’ in the respective names of the parliamentary groups is both expression and trigger for environmental concerns of both parties and may be seen as a top-down setting of values for group members. Following the statements of the groups, the S&D as well as the ECR are also committed to animal welfare, however, it is not a core policy issue for these parties. The European People’s Party (EPP) instead is close to agrarian interests (Hix et al., Citation2003), on their webpages they do not even mention animal welfare but the protection of farmers’ interests as primary agricultural policy goal. Animal welfare regulations could have a negative impact on farmers due to higher costs, e.g. in new housing systems or transportation facilities. We therefore hypothesize that EPP MEPs are more likely to vote against (H3b). For the remaining parties the background search did not reveal any general positioning towards animal welfare related issues.

Regarding the demographic identity, we derive two hypotheses. The Eurobarometer survey shows that, firstly, women find it more important to protect the welfare of farmed animals than men. This derives also from psychological research stating that women are more prone to empathy towards animals and the issue therefore addresses them in their role as caring individuals as opposed to cruel men (Eldridge & Gluck, Citation1996). Secondly, the survey reveals that younger people are most willing to pay more for products sourced from animal welfare-friendly production systems (Commission, Citation2016). Psychological studies underpin this argument by an in-depth analysis of group-based profiles that connect younger generations more intensely with vegetarianism and veganism, which are group-based emotional factors promoting animal welfare (Thomas et al., Citation2019). Hypothesis 4a reads that female MEPs are more likely to vote for animal welfare than male MEPs. Hypothesis 4b proposes that younger MEPs are more likely to vote for animal welfare.

Methods and data collection

We operationalize the results of the two votes as our dependent variables. Regarding the independent variables, we combine several data sources: the data provided by votewatch contain information on nationality, political group and the vote for each MEP. To test sectoral and demographic identities, we collected additional data (committee membership, gender, and age). In order to explore national identities, we collected agro-structural data (for the transportation and the rabbit policy) and data on national legislation (rabbit policy). We first conducted bivariate analyses of the voting patterns along political groups, countries, committees, and gender and age. In addition to the binary evaluation of the data, we carried out a multinomial logistic regression. Our dependent variable is not dichotomous but has three possible values: against, for or abstain. We ran several models to assess which of our independent variables are significant. The first model only included political group membership. We chose the EPP as our baseline because it is the biggest group within the EP and has a comparatively strong organizational identity. At the same time, individual votes of members in the EPP varied, showing a lack of coherent salience for organizational identity. Given the opposition of the EPP to the policy, our base outcome is a vote against the policy. Finally, we performed a multilevel analysis by means of a generalized structural equation model in order to account for the macro effect of local identities. Local identity (country) is treated as a latent variable in this model, which is specified by the two nationally relevant characteristics related to the policy of interest. Our base outcome is a vote against the policy proposal.

Results

Bivariate analysis

In , a bivariate overview of the votes along political groups is drawn. The first finding is that The Greens/EFA in both decisions unanimously voted for the animal welfare policies, the same applies to the GUE-NGL with the exception of two abstentions in the transportation case. Given the uniformity of votes within the Greens/EFA and the GUE-NGL, we can confirm hypothesis H3a on the organizational identity: apparently, belonging to one of these two political groups is a very strong predictor for voting for animal welfare. Animal welfare falls into the core issues of green parties which makes the fractions likely to form a common group position. A similar uniformity regarding animal welfare can be confirmed for the S&D: Though in both decisions a small share of MEPs voted against the policies or abstained, the vast majority voted for animal welfare in both cases. The same findings apply for the ECR and for the ALDE/ADLE members, apparently both groups formed uniform group positions for animal welfare. For the remaining parties the voting patterns vary greatly between the cases: EPP MEPs almost uniformly voted against the rabbit protection policy. A possible explanation is that political parties within the EPP are historically closely tied to the farming sector and the introduction of binding housing standards would be associated with high financial burdens for farmers. This is the first evidence for H3b, which assumed that EPP MEPs would vote against stricter animal welfare standards. However, in the case of transportation, the EPP fraction was highly divided with almost half of the MEPs abstaining the vote, which is an interesting finding. A hypothesis that we can derive from the background information on that specific policy proposal is, that the EPP MEP’s were loyal to their fraction member Phil Hogan, then Commissioner for Agriculture. The policy proposal to enact stricter controls and implementation of existing EU animal transportation law, is an implicit criticism on the fulfilment of tasks of the Agricultural Commissioner. Among EFDD and ENF deputies’ policy preferences are much less clear, for both parties the voting patterns vary greatly in both cases. An explanation for this is that political parties within these groups unite because of other topics, e.g. EU-scepticism or right-wing ideology and do not have uniform policy preferences in policy areas such as animal welfare.

Table 1. Votes by political group (organizational identity).

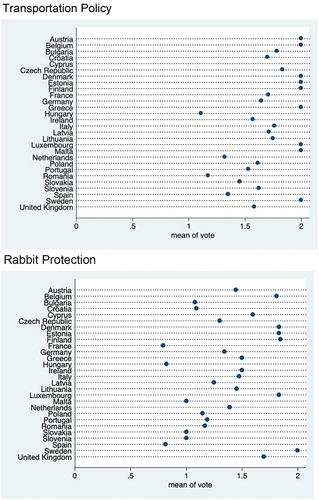

Secondly, we examined local identities (). We calculated the average voting outcome of MEPs for each country, 0 meaning a vote against the respective policy, 1 an abstention and 2 a vote for it. When looking at the votes in comparison, some parallels exist in transportation and the rabbit case. Both policies would directly affect farming practices and increase production costs. In the cases of transportation and rabbit protection, MEPs from the northern European countries (Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Luxembourg, Sweden) almost consensually voted for the policy. Secondly, in some countries (Greece, Malta) there is contradictory high approval of transportation versus a low approval of rabbit protection. An explanation could be the very small share of livestock exports of both countries. In Hungary, the Netherlands, Romania, and Spain there is a clear majority that rejects stricter transportation rules – in these countries livestock farming and trade is an important pillar of the agricultural sector. In the case of rabbit farming there is a clear rejection of the policy in France, Hungary, and Spain. All three countries count with major rabbit production. Interestingly, MEPs from Italy, which is the third largest producing country in the EU, voted for rabbit protection. Other big producers are Germany, Portugal, and Belgium. However, Germany and Belgium have national legislation for farm rabbits, which might explain their consent to an EU policy. In the remaining countries, there are slight majorities for both policies or votes are balanced regarding transportation and rabbit protection.

Figure 1. Votes by member states (local identity). a) Transportation Policy, b) Rabbit Protection Policy. Source: own compilation.

To operationalize sectoral identity, we examined whether MEPs were either part of the environmental or agricultural committees. In some cases, MEPs were members of both committees. For these MEPs, we build a separate category (agriculture AND environment). However, the number of MEPs being in a committee was low, which is why the findings on sectoral identity are preliminary. Only 7% of MEPs are in the agricultural, 12% in the environmental committee, and 4% in both. The data show that members of the environmental committee alone displayed a slightly higher average approval for the three policies which is the first evidence for H2b.

Then, we looked at the approximation for demographic identity. The bivariate analysis of gender and age shows a higher percentage of women voting for animal welfare in both, rabbit protection (82% compared to 68% in men) and transportation (67% compared to 57% in men) which confirms H4a. In contrast to gender, the bivariate analysis does not offer evidence for differences between age groups, which is why we have to reject H4b.

Multinomial logistic regression

The results of the multinomial logistic regression reveal that in the case of the rabbit policy the chance of voting for the proposal or abstaining rises significantly when MEPs are members of any other group than the EPP. For all groups, the effect sizes of voting for the policy (compared to against) are stronger than those of abstaining (compared to voting against the policy). For the transportation policy, party members of the ENF have a significantly lower chance of abstaining compared to members of the EPP, while members of ALDE/ADLE, ECR, and S&D have a significantly higher chance of voting in favour rather than against.

When adding nationality to the model, the explanatory fit of our model increases in both cases to over 56% (R2 of 0.5689) in the rabbit case and to 46% (R2 of 0.4578) in the transportation case. For the rabbit case the probability of abstaining is significantly higher in Italy and the United Kingdom, whilst the probability of voting for the policy is higher in Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Finland, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, and the United Kingdom. Only in Spain are the MEPs more likely to vote against. For the transportation case the probability of abstaining is significantly higher only for MEPs from Italy. Similarly, the probability to vote for the policy decreases significantly when MEPs are from Hungary, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. For all effect calculations, France is the reference group.

Thirdly, we added committee membership which slightly increased the explanatory power of both models to R2 0.5823 in the rabbit case and R2 0.4715 in the transportation case. Committee membership has no significant effect in the case of abstentions in both cases; however, a negative significant effect was found for membership of the agricultural committee as well as for non-membership of any of the analysed committees for the case of rabbit farming. For transportation policy, the co-membership in the environmental and agricultural committee results in a significantly lower chance (coef. −2.5) to vote for the regulation compared to an exclusive membership in the environmental committee. This indicates that the sectoral agricultural identity has been more salient than the environmental sectoral identity.

Finally, we added gender and age. The R2 here is 0.5988 for the rabbit case and 0.4779 for the transportation case. Neither gender nor age is significant for abstentions. The probability for voting for the policy is significantly higher for women in the rabbit case but not in the transportation case. By adding more variables to the original model, thus testing the multiple facets of the social identities that influence individual voting behaviour, the multinomial regression models keep their good fit. McFadden’s adjusted R2, which indicates the fit of a model by accounting for its increasing complexity, varies between 0.362 and 0.376 for rabbit farming and between 0.218 and 0.478 for transportation policy. In the former case, it is highest when examining the second of the four multinomial logistic regression models, testifying to the great importance of organizational and local identities. For transportation policy, it is highest in the last model including all four tested identities, which underlines the importance of checking for multiple social identities when explaining voting behaviour in the EP.

Multinomial multilevel logistic regression

The results of the multilevel regression are displayed in . The results reveal that the strongest predictor for both abstentions and voting for the policy is political group membership in both cases. For the transportation case, this is indeed the only significant predictor. In the rabbit case more variables are significant: Here, the probability of abstaining is significantly higher for MEPs who come from countries that have already passed national legislation to protect rabbits, which is an indicator for local identity. In addition to group membership, being a member of the agricultural committee has a significant negative effect. Not being a member of a committee similarly has a significant negative effect. However, both effects are rather low and may be explained by the small number of MEPs who are members of a committee at all.

Table 2. Results of the multilevel analysis.

In addition to group and committee, the model reveals that gender is significant as female MEPs are more likely to vote for rabbit protection. Finally, we observe the significant effect of local identities: MEPs who come from a country that does not have a large commercial rabbit farming sector are more likely to vote for the policy. Moreover, the probability of voting for rabbit protection increases when a country has already passed national legislation to protect rabbits. Compared to the null model of multinomial multilevel logistic regression, the AIC value of the final model is lowest with 657.2576 (AIC), in contrast to 1141.502 (AIC) in the null model for rabbit farming. The AIC criterion decreases almost continuously (with the exception of the difference between the model with political group membership and the model with political group and committee membership). For transportation policy, the AIC value is lowest (675.797) in the second model including only political group membership and the indicator for national identity salience. This again underlines the good fit of either a final multinomial multilevel regression model including all social identities or the model including organizational and local identity, with the importance of identities varying depending on the issue at hand. The models also justify future attempts to investigate identities as a latent construct, as it has been done with the national identity.

Discussion and conclusion

Our findings reveal the importance of considering the interplay of multiple social identities under different circumstances in order to understand individual decision-making. SIPP turns out to be a valuable approach that may complement existing perspectives on voting behaviour. Theoretically, SIPP assumes that the salience of one identity determines the behaviour of political actors and that shared social identities influence the likelihood of collective action. The additional value of SIPP is the integrative consideration of organizational, local, sectoral, demographic, and informal identities. In animal welfare policymaking, we expected either organizational (operationalized by political group) or sectoral (operationalized by committee membership) identities to exert a strong influence on MEPs’ voting behaviour. In addition, we assumed that local identity (operationalized by nationality) might prove salient depending on the importance of livestock farming in each country and on the existence of national animal welfare legislation. The strongest predictor for MEPs’ voting choices in both cases is political group membership, especially in cases when groups claim issue ownership. In the area of animal welfare policy and most likely also in other policy issues connected to environmental and sustainability policymaking, this is the case for the Greens/EFA and the GUE/NGL. In cases where MEPs defect from their political group line, we found that the salience of the local identity offers an explanation. In the case of rabbit farming the existence of national legislation increases the likelihood of voting for the policy, the existence of a large commercial rabbit farming sector leads to a higher probability of voting against animal welfare. Moreover, in the case of rabbit farming the effect of committee membership on MEPs’ decision-making is significant. Given the low number of MEPs represented in the relevant committees, we recommend testing other approximations for sectoral identity in future empirical studies. In national parliaments committee membership might have a stronger effect. Also, sectoral identities may be more salient in the executive compared to the legislative. Within topical ministries, such as the ministry of environment, political actors are likely to form common views on a topic and thereby build a shared sectoral identity. Though we expected demographic identities to be salient only in few policy processes, we observed a significant influence of gender in the case of rabbit farming. The finding that women care more for animal welfare than men is in line with representative surveys and with psychological research. Further investigation is needed to understand why gender is not salient in the transportation case, the same applies to committee membership.

With regard to agricultural and environmental policy more generally, the findings allow us to draw primary conclusions on the predictors of decision-making at the EU level. These findings should be tested with further cases and linked to other sustainability issues in agricultural policy to gain an in-depth understanding of the EU’s policymaking at the interface of environmental and agricultural policy. Future studies could complement our findings by conducting personalized surveys or expert interviews with randomly selected MEPs to generate future insights into the complex nature of individual identity structures and their influence on preferences and behaviour.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Colette S. Vogeler is research associate at the Institute of Comparative Politics and Public Policy at the University of Braunschweig. Previously, she worked at the Universities of Heidelberg and Kaiserslautern and gathered international experience during her work and educational stays in China and South America. Her research interests and expertise lie in the field of comparative policy analysis, with a focus on environmental, agrarian, and animal welfare policies.

Johanna Hornung is research fellow at the Institute of Comparative Politics and Public Policy at the University of Braunschweig, Germany. Due to her international profile including education in Barcelona and a research stay in Paris, she is particularly interested in comparative policy studies on a variety of policy fields, including health policy, environmental policy, and infrastructure policy. She applies both quantitative and qualitative methods and has a special interest in approaches of political psychology as well as policy process theories with a psychological basis, particularly the Social Identity Approach and the Programmatic Action Framework (PAF).

Nils C. Bandelow is full professor for political science and heads the Institute of Comparative Politics and Public Policy at the University of Braunschweig, Germany. Previously, he worked at the Universities of Bochum and Düsseldorf and gathered international experience for instance during his fellowship at the University of Birmingham. His research interests and expertise lie in the field of policy process research, with a special focus on health policies, sustainability, and environmental policies, as well as infrastructure and mobility policy. He applies established and emerging theories and frameworks of policy process research and those containing psychological foundations, such as the Social Identity Approach and the Programmatic Action Framework (PAF).

References

- Béland, D. (2017). Identity, politics and public policy. Critical Policy Studies, 11(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2016.1159140

- Bennett, R., & Appleby, M. (2010). Animal welfare policy in the European Union. In A. Oskam, G. Meester, & H. Jan Silvis (Eds.), EU policy for agriculture, food and rural areas (pp. 243–252). Wageningen Academic Publ.

- Bonaiuto, M., Carrus, G., Martorella, H., & Bonnes, M. (2002). Local identity processes and environmental attitudes in land use changes: The case of natural protected areas. Journal of Economic Psychology, 23(5), 631–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(02)00121-6

- Bowler, S., & Farrell, D. M. (1995). The Organizing of the European Parliament: Committees, specialization and co-ordination. British Journal of Political Science, 2(2), 219–243. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400007158

- Buller, H., Blokhuis, H., Jensen, P., & Keeling, L. (2018). Towards farm animal welfare and sustainability. animals, 8(6), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8060081

- Cole, M. S., & Bruch, H. (2006). Organizational identity strength, identification, and commitment and their relationships to turnover intention: Does organizational hierarchy matter? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(5), 585–605. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.378

- Commission, European. (2014). 40 Years of animal welfare. https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/animals/docs/aw_infograph_40-years-of-aw.pdf

- Commission, European. (2016). Special Eurobarometer 442: Attitudes of Europeans towards Animal Welfare. https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/S2096_84_4_442_ENG

- Commission, European. (2017). Commercial rabbit farming in the European Union. Publications Office of the European Union.https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/5029d977-387c-11e8-b5fe-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

- Commission, European. (2018). Special Eurobarometer 473 – Europeans, Agriculture and the CAP. https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/S2161_88_4_473_ENG

- Commission, European. (2020). Statisitical Factsheets Agriculture. Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/farming/facts-and-figures/markets/production/production-country/statistical-factsheets_en

- Cornish, A., Raubenheimer, D., & McGreevy, P. (2016). What we know about the public’s level of concern for farm animal welfare in food production in developed countries. animals, 6, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani6110074

- Costello, R., & Thomson, R. (2016). Bicameralism, nationality and party cohesion in the European Parliament. Party Politics, 22(6), 773–783. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068814563972

- Daugbjerg, C., & Feindt, P. H. (2017). Post-exceptionalism in public policy: Transforming food and agricultural policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(11), 1565–1584. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1334081

- Daugbjerg, C., Smed, S., Andersen, L. M., & Schvartzman, Y. (2014). Improving eco-labelling as an environmental policy instrument: Knowledge, trust and organic consumption. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 16(4), 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2013.879038

- Daugbjerg, C., & Swinbank, A. (2012). An introduction to the ‘new’ politics of agriculture and food. Policy and Society, 31(4), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2012.10.002

- EFSA. (2005). Scientific opinion of the scientific panel on animal health and welfare on ‘The impact of the current housing and husbandry systems on the health and welfare of farmed domestic rabbits’. Publications Office of the EU, 267, 1–31.

- Eldridge, J. J., & Gluck, J. P. (1996). Gender differences in attitudes toward animal research. Ethics & Behavior, 6(3), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb0603_5

- Engler, F., & Zohlnhöfer, R. (2018). Left parties, voter preferences, and economic policy-making in Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(11), 1620–1638. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1545796

- Eur-Lex. (2007). Treaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community, signed at Lisbon, 13 December 2007. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:12007L/TXT

- European Court of Auditors. (2018). Animal welfare in the EU: Closing the gap between ambitious goals and practical implementation. https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/DocItem.aspx?did=47557

- FAWC. (2016). Sustainable agriculture and farm animal welfare. London. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/593479/Advice_about_sustainable_agriculture_and_farm_animal_welfare_-_final_2016.pdf

- Greer, A. (2017). Post-exceptional politics in agriculture: An examination of the 2013 CAP reform. Journal of European Public Policy, 2(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1334080

- Grethe, H. (2017). The economics of farm animal welfare. Annual Review of Ressource Economics, 9(75), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100516-053419

- Harvey, D., & Hubbard, C. (2013). Reconsidering the political economy of farm animal welfare: An anatomy of market failure. Food Policy, 38, 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.11.006

- Haslam, C., Jetten, J., Haslam, S. A., Pugliese, C., & Tonks, J. (2011). I remember therefore I am, and I am therefore I remember: Exploring the contributions of episodic and semantic self-knowledge to strength of identity. British Journal of Psychology, 102(2), 184–203. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712610X508091

- Hassenteufel, P., Smyrl, M., Genieys, W., & Moreno-Fuentes, F. J. (2010). Programmatic actors and the transformation of European health care states. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 35(4), 517–538. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-2010-015

- Hix, S. (2002). Parliamentary behavior with two principals: Preferences, parties, and voting in the European Parliament. American Journal of Political Science, 46(3), 688–698. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088408

- Hix, S. (2004). Electoral institutions and legislative behavior – explaining voting defection in the European Parliament. World Politics, 56(2), 194–223. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2004.0012

- Hix, S. (2008). Towards a partisan theory of EU politics. Journal of European Public Policy, 15(8), 1254–1265. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760802407821

- Hix, S., & Høyland, B. (2014). Political behaviour in the European Parliament. In M. Shane, T. Saalfeld, & K. W. Strøm (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of legislative studies (pp. 591–608). Oxford University Press.

- Hix, S., Kreppel, A., & Noury, A. (2003). The party system in the European Parliament: Collusive or competitive. Journal of Common Market Studies, 41(2), 309–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00424

- Hix, S., Noury, A., & Roland, G. (2006). Dimensions of politics in the European Parliament. American Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 494–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00198.x

- Hornung, J., & Bandelow, N. C. (2020). The programmatic elite in German health policy. Collective action and sectoral history. Public Policy and Administration, 35(3), 247–265. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0952076718798887

- Hornung, J., Bandelow, N. C., & Vogeler, C. S. (2019). Social identities in the policy process. Policy Sciences, 52(2), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-018-9340-6

- Lever, J., & Evans, A. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and farm animal welfare: Towards sustainable development in the food industry? In S. O. Idowu & S. Vertigans (Eds.), Stages of corporate social responsibility. CSR, sustainability, ethics & governance (pp. 205–222). Springer.

- Lundmark, F., Berg, C., Schmid, O., Behdadi, D., & Röcklinsberg, H. (2014). Intentions and values in animal welfare legislation and standards. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 27(6), 991–1017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-014-9512-0

- Lusk, J. L., & Norwood, F. B. (2011). Animal Welfare Economics. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 33(4), 463–483. https://doi.org/10.1093/aepp/ppr036

- McElroy, G., & Benoit, K. (2011). Policy positioning in the European Parliament. European Union Politics, 13(1), 150–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116511416680

- Mühlbock, M. (2012). National versus European: Party control over members of the European Parliament. West European Politics, 35(3), 607–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.665743

- Mühlbock, M., & Tosun, J. (2018). Responsiveness to different national interests: Voting behaviour on genetically modified organisms in the council of the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(2), 385–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12609

- Oakes, P. J., Turner, J. C., & Haslam, S. A. (1991). Perceiving people as group members: The role of fit in the salience of social categorizations. British Journal of Social Psychology, 30(2), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1991.tb00930.x

- Parker, C., Carey, R., De Costa, J., & Scrinis, G. (2017). Can the hidden hand of the market be an effective and legitimate regulator? The Case of Animal Welfare Under a Labeling for Consumer Choice Policy Approach. Regulation & Governance, 11(4), 368–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12147

- Parliament, E. (2017b). Report on minimum standards for the protection of farm rabbits. Brussels https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-8-2017-0011_EN.html

- Parliament, E. (2019). Report on the implementation of Council Regulation No 1/2005 on the protection of animals during transport within and outside the EU. Brussels. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-8-2019-0057_EN.html

- Pollex, J. (2017). Regulating consumption for sustainability? Why the European Union chooses information instruments to foster sustainable consumption. European Policy Analysis, 3(1), 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1005

- Ringe, N. (2010). Who decides, and how? Preferences, uncertainty, and policy choice in the European Parliament. Oxford University Press.

- Roger, L., & Winzen, T. (2015). Party groups and committee negotiations in the European Parliament: Outside attention and the anticipation of plenary conflict. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(3), doi: 0.1080/13501763.2014.941379

- Rooij, S. J. G., de Lauwere, C. C., & van der Ploeg, J. D. (2010). Entrapped in group Solidarity? Animal welfare, the ethical positions of farmers and the difficult search for alternatives. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 12(4), 341–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2010.528882

- Schmid, O., & Kilchsperger, R. (2010). Overview of animal welfare standards and initiatives in selected EU and third countries. http://www.econwelfare.eu/publications/econwelfared1.2report_update_nov2010.pdf

- Schwindenhammer, S. (2017). Global organic agriculture policy-making through standards as an organizational field: When institutional dynamics meet entrepreneurs. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(11), 1678–1697. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1334086

- Spoolder, H., Bokma, M., Harvey, D., Keeling, L., Majewsky, E., Roest, K. d., & Schmid, O. (2011). EconWelfare findings, conclusions and recommendations concerning effective policy instruments in the route towards higher animal welfare in the EU. http://www.econwelfare.eu/publications/EconWelfareD0.5_Findings_conclusions_and_recommendations.pdf

- Strohbach, M. W., Kohler, M. L., Dauber, J., & Klimek, S. (2015). High nature value farming: From indication to conservation. Ecological Indicators, 57, 557–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.05.021

- Tajfel, H. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology, 33, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.33.020182.000245

- Thomann, E., Trein, P., & Maggetti, M. (2019). What’s the problem? Multilevel governance and problem-solving. European Policy Analysis, 5(1), 37–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1062

- Thomas, E. F., Bury, S. M., Louis, W. R., Amiot, C. E., Molenberghs, P., Crane, M. F., & Decety, J. (2019). Vegetarian, vegan, activist, radical: Using latent profile analysis to examine different forms of support for animal welfare. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 22(6), https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430218824407

- Tosun, J. (2017). Party support for post-exceptionalism in agri-food politics and policy: Germany and the United Kingdom compared. Journal of European Public Policy, 1623–1640. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1334083

- Transue, J. E. (2007). Identity salience, identity Acceptance, and racial policy attitudes: American national identity as a uniting force. American Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00238.x

- Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Blackwell.

- Veissier, I., Butterworth, A., Bock, B., & Roe, E. (2008). European approaches to ensure good animal welfare. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 113(4), 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2008.01.008

- Vogeler, C. S. (2017). Farm animal welfare policy in comparative perspective: Determinants of cross-national differences in Austria. Germany, and Switzerland. European Policy Analysis, 3(1), 20–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1015

- Vogeler, C. S. (2019). Why do farm animal welfare regulations vary between EU member states? A comparative analysis of societal and party political determinants in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(2), 317–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12794

- Vogeler, C. S. (2020). Politicizing farm animal welfare: A comparative study of policy change in the United States of America. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, Online First, https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2020.1742069

- Walsh, K. C. (2004). Talking about politics: Informal groups and social identity in American life (studies in communication, media, and public opinion). Chicago University Press.

- Whitley, C. T., Gunderson, R., & Charters, M. (2018). Public receptiveness to policies promoting plant-based diets: Framing effects and social psychological and structural influences. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 20(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2017.1304817

- Yeates, J. W. (2018). Naturalness and animal welfare. Animals, 8(53), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8040053