1. Introduction

In this special issue, we aim to reflect on the first 21 years of research published in the Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning (JEPP), consisting of over 600 research articles and nineteen special issues. We briefly discuss the origins and evolution of the Journal and introduce a series of 12 papers that we have invited to mark the Journal reaching this stage of maturity. We also take this opportunity to consider the strengths of the Journal, highlight what we think we could do better and plot some future direction for the Journal.

JEPP was founded with the aim of contributing to the knowledge we need for sustainable environmental governance. This remains our priority, although the deepening of the climate emergency and ecological crisis over the life of the Journal has heightened the urgency in which we make this claim. We continue to be focused on the fact that alongside the physical outcomes of these crises, there is a parallel challenge of how to democratically transform the social and political institutions that reproduce our state of unsustainability into those that can support just, circular, biobased societies (Steffen et al., Citation2018). We maintain that only democratic institutions are able to address the socio-ecological challenges of the twenty-first century, knowing that there is a tendency of autocratic regimes to deteriorate into kleptocratic arrangements with little regard for the broader public good. While we acknowledge that academic journals may not be the most powerful drivers of transformative change, we remain convinced that robust, probing, peer-reviewed research plays an important role in informing the effective, just, democratic, and well-reasoned strategies for sustainable development. In an age of increasingly polarized debates, populist discourse, rising concern over the trustworthiness of knowledge and declining faith in political leaders, we think that Journals such as JEPP are needed more than ever.

Such challenges are not easy to navigate, and the complexity of the questions faced by environmental governance are reflected in the articles published in JEPP. The diversity of content, contributors and intellectual traditions displayed in the Journal effectively reflects its early ambition to promote critical and interdisciplinary analyses of environmental policy and planning in all stages of the policy and planning processes; from agenda-setting to implementation and evaluation, and the interactions between governments, society and markets that frame environmental narratives and behaviours. In pursuing this agenda, we feel that JEPP has developed a recognized forum for publishing high-quality, rigorous and critical scholarly work that continually questions emerging and traditional conventions in environmental policy. Until we see the emergence of truly sustainable development, we think this is a valuable role for the Journal to maintain.

2. JEPP: a brief retrospective

A motivation for the founding of JEPP was the recognition that, parallel to the growing evidence of the anthropological impact on the world’s atmospheric and ecological system, ‘sustainable development’, as proposed by the Brundtland Commission in 1987, was emerging as a powerful frame for stimulating and shaping environmental policy and governance responses, such as widespread initiatives under Local Agenda 21. The explicit interdependence of environmental, economic and social issues in the Bruntland sustainability concept (Citation1987) posed a challenge for the way in which knowledge had been previously generated (seen, for example in the emergence of ideas around post-normal science: Funtowicz & Ravetz, Citation1995) and gave rise to the need for new channels for inter-disciplinary sustainability research, particularly for social science perspectives, rather than the more traditional forums dedicated to environmental science and later environmental and resource economics. This had further impetus, as least in European context, as the European Union’s Single European Act in 1986 widened the environmental objectives of the EU leading to new regulatory instruments being adopted by Member States (such as those stimulated by the Environmental Impact Assessment Directive in 1985 and the Habitats Directive in 1992). This proved to be an effective catalyst for thinking of new approaches to environmental policy that highlighted the role of European spatial planning systems as key implementing mechanisms. The significance of this changing context for environmental policy research was recognized by a small group of researchers at the School of City and Regional Planning at Cardiff University (UK), who instigated the formation of JEPP in 1999, initially published by Wiley and shifting to the current publisher (Taylor and Francis) in 2003. The first editors comprised of Kevin Bishop, Terry Marsden, Andrew Flynn, and Richard Cowell (first as the book reviews editor, later as co-editor), supported by a very strong international Editorial Board, the credibility of whom provided a strong impetus to the Journal attracting its early crop of high-quality submissions.

The first Editorial (Flynn et al., Citation1999) set out the context and aspirations for the Journal, which still leave a strong imprint on the scope of JEPP today. This highlighted a call for critical analysis; integration of different policy sectors (transport, agriculture, fisheries, urban and rural areas); an inclusion of citizen/consumer perspectives; a need to highlight the processes of uneven development; and the promotion of international comparative research and policy learning. These expectations were revisited in an Editorial on the seventh anniversary of JEPP (Cowell & Flynn, Citation2006), which noted that the Journal had already made some key contributions in areas prioritized in the first issue (particularly ecological modernization, rescaling of environmental governance, and wider epistemological and methodological debates, such as a much-cited Special Issue on discourse analysis). It also noted a number of weaknesses in the first years of JEPP, such as an over-representation of Northern European research in the midst of an ever-globalized environmental emergency. The seven-year Editorial articulated a set of revised objectives for JEPP, which included a shift in emphasis to more theoretical studies and conceptually-guided empirical work, which have subsequently become distinctive features of papers accepted in the Journal.

In response to the increasing number of manuscripts, the editorial team was reorganized in 2011 with the addition of Geraint Ellis, a planner at Queen’s University Belfast, and Peter H. Feindt, then a member of the Cardiff School of City and Regional Planning. Soon, Alex Franklin, then also at Cardiff, replaced Richard Cowell. The years 2014 and 2015 marked a major shift in how JEPP operated as its Editorial Office followed Peter H. Feindt in his move to Wageningen University. After Andrew Flynn and Alex Franklin resigned due to other work commitments, Carsten Daugbjerg (then at Australia National University) and Andrea Gerlak (University of Arizona) strengthened the links of the Journal to the political science, geography and development communities. They also broadened the geographical outlook and global profile of JEPP, further enhanced by the addition of Tamara Metze (Wageningen University) and Xun Wu (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology), the latter as a response to the increasing importance of scholarship from Asia in the Journal’s field. In 2019 the Editorial Office relocated to Queen’s University Belfast where the current Editorial Manager, Nick Johnston assumed the role. After many years of energetic dedication, 2020 sees the retirement of Peter H. Feindt from the Editorial Team, and to whom we offer substantial gratitude.

This Editorial marks a good opportunity to reflect on the changes in the context and content of JEPP over its first two decades. It is clear that the foresight and initiative of the early Editors provided a strong springboard for the Journal, for which the current Editors are indebted. JEPP has evolved considerably over the years, primarily guided by advancements in our theoretical and empirical understanding of environmental challenges and the governance responses it has stimulated. It has also evolved through changes in those that have had editorial responsibility, with Editors now based in three European countries, Asia and North America, the advice we receive from our Editorial Board, as well as the shifting technologies of publishing. It is notable that these trends have accelerated the success of the Journal: we now publish six issues a year and have a bi-annual call for Special Issues, which has gathered a larger readership than ever before, with an increasingly international reach. While we acknowledge the limitations of expressing the value of academic research in quantified indices, we are proud of the fact that JEPP has seen a steady growth in its JCR Impact Factor since it was accepted for inclusion in 2010 (the 2019 JCR is 3.04), and achieved (in 2018) being the second ranked journal in both the fields of Regional & Urban Planning and Development Studies. We take this as reassurance that JEPP and its authors are highly visible, publishing relevant research and making a valuable contribution to the wider research community.

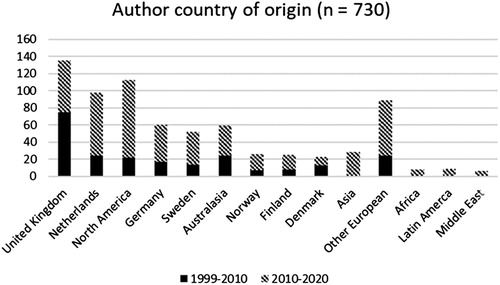

We have maintained this focus as environmental scholarship has expanded, competing journals emerged and the number of submissions we receive increased. The Journal invites original papers applying approaches from the political and social sciences, political economy, human geography, planning and cultural studies. shows the distribution of disciplines represented by articles published in the Journal, and how it has changed over the first and second decades of publication. The focus on these disciplines reflects the multi-dimensional challenges of environmental policy, the nature of the most fertile research being undertaken in the field and the profile of our readership. In addition to environmental science, planning, geography, disciplines with strong presence in the journal from the beginning, more contributions from political sciences, international relations, governance studies, public administration, development studies, and science and technology studies have been featured in the journal in recent years. Although we do consider papers from economic perspectives, we rarely publish those based on traditional economic perspectives as environmental economics has emerged as a large research discipline by itself and is already well-covered by a number of journals.

Figure 1. Distribution of Designated Disciplines of JEPP authors over time. These were designated by the department or research institute that the authors belonged to, and not a precise indication of each authors disciplinary training and outlook.

Amidst an increasing supply of environmental research papers, we feel the need to further strengthen our focus on critical and conceptually driven perspectives on environmental governance, policy and planning, as this offers the most valuable and unique space for the Journal (see Newig & Rose, Citation2020 in this issue for further discussion of this research focus). The aims and scope of the Journal now more clearly emphasize that there is a strong preference for theoretically guided analysis and engagement with broader environmental policy and planning agendas. We hope that this means that the Journal stimulates knowledge beyond the limits of particular case studies and contributes to broader conceptual debates within the policy science and planning literatures.

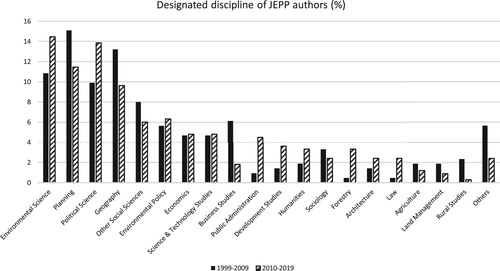

The research communities served by JEPP can also be gleaned from the origins and scope of the papers we publish. At the time of writing (August 2020), we have published a total of 630 papers (up to Vol 22.3 plus a further 22 online advance published papers). shows the countries of origin of authors, noting how the Journal has become far more international in recent years. The original dominance of authors from the UK has given way to a much larger presence of authors from other European countries, and increasingly North America, Australia and Asia. Although the Global South is widely underrepresented in terms of the distribution of authorship, the readership among countries in the Global South has been steadily expanding as they are the forefront of challenges of resource conflicts and climate crisis.

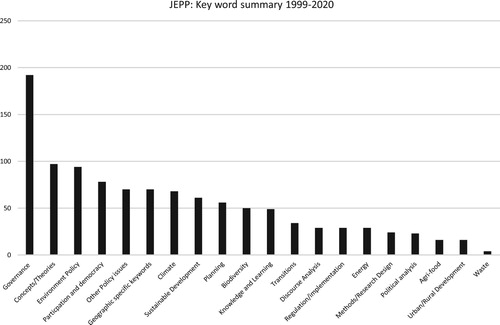

An insight to the changing issues being addressed by the research reported in JEPP can be gained by looking at the changing profile of key words. shows a clustering of the most frequent keywords used by authors in our published papers. This highlights some rather predicable patterns that reinforce the space of JEPP highlighted above, with those issues most central to our aims being most common. In some ways the surprising insights from this analysis is that the more tangible symptoms of our environmental crises (biodiversity, waste, energy, agri-food) are not more commonly used to indicate the content of JEPP papers. Inevitably, there has been a changing emphasis of key words over the life of the journal: in the first three years of the journal ‘ecological modernisation’ was the most common key word, from 2005 onwards it was replaced by ‘governance’. Only from 2011 onwards did ‘climate change’ become a predominant theme, while almost all the mentions of ‘learning’ have occurred in the last 3 years and more than half the mentions of ‘urban planning’ have occurred since 2017, which is puzzling given the title of the Journal. Although we should not read too much into these patterns, given the relatively small sample, this finding reinforces our understanding of the particular focus of the Journal, and the evolution of its content as new environmental challenges become apparent.

Figure 3. JEPP Keywords, 1999–2020. We sampled any key word that appeared in published papers more than 10 times in the journal. We then grouped each key word with similar terms (e.g. ‘discourse’ and ‘discourse analysis’ or ‘sustainability’ and ‘sustainable development’).

Another way of understanding the strengths of JEPP is to look at those papers that have been most downloaded and cited over the life of the journal. Downloads are heavily influenced by whether papers are open access (regrettably only 12% of our manuscripts are fully open, but we do have temporary free access for many more). Both our most cited and downloaded paper is the introduction to our Politics of Sustainability Transitions Special Issue by Avelino et al. (Citation2016). Indeed, in terms of downloads, half of the ten most downloaded papers deal with the energy transition (Avelino & Wittmayer, Citation2016; Longhurst & Chilvers, Citation2016; Osunmuyiwa et al., Citation2018; Cowell et al., Citation2017). The other key issue in terms of downloads is discourse analysis, and three of our ten most downloaded papers focus on this topic (Feindt & Oels, Citation2005; Leipold et al., Citation2019; Hajer & Versteeg, Citation2005). In terms of citations, we again find that papers dealing with sustainability and energy transitions make half of the ten most cited papers (Avelino et al., Citation2016; Cass et al., Citation2010; Chilvers & Longhurst, Citation2016; Haggett, Citation2008; Hindmarsh & Matthews, Citation2008), with the other five focusing on sustainability governance (Lange et al., Citation2013), climate adaptation (Bauer et al., Citation2012; Storbjörk, Citation2010), local environmental politics in China (Ran, Citation2013) and marine spatial planning (Kidd & Ellis, Citation2012).

In addition to these most popular papers, there are a number of discernible themes around which JEPP has made some particularly important contributions, often centred on Special Issues, which we are now promoting as a key vehicle for some of our most valuable contributions. For example, discursive analysis of environmental policy and planning has been an important part of JEPP’s profile, with a Special Issue (Feindt & Oels, Citation2005) reflecting ten years of Maarten Hajer’s seminal book (Hajer, Citation1995) and a follow-up Special Issue on discourse analysis in 2019 (Leipold et al., Citation2019). As noted above, these include some of the Journal’s most cited papers, and other Special Issues on power/knowledge (Van Assche et al., Citation2017) and on reflexive governance (Feindt & Weiland, Citation2018) have further added important insights to this field. Another important strand has been critical inquiry into new modes of governance, including multi-level and collaborative governance. Examples include the special issues on scale in environmental policy making (Newig & Moss, Citation2017), on policy learning (Gerlak & Heikkila, Citation2019), a special section on transparency in environmental governance (Gupta et al., Citation2020) and an upcoming Special Issue (2020) on harder soft governance. JEPP has also provided a forum for fundamental questions of environmental governance, including Special Issues on the governance of sustainable development (Newig et al., Citation2007) and on ecological democracy (Pickering et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, JEPP has been a forum for the critical inquiry into specific topics in environmental policy and planning, including sustainable mobility (Berger et al., Citation2014), fracking (Dodge & Metze ., Citation2017), energy transitions (Avelino et al., Citation2016) and marine spatial planning (Kidd & Ellis, Citation2012).

3. JEPP at 21 special issue

The goal of the 21st anniversary special issue is to reflect on the state of the field of analysis of environmental policy planning, highlighting its achievements, characteristics and challenges. In line with the ethos of JEPP, we take a more specific brief to ask ‘How can we peacefully and fairly achieve more sustainable environmental governance?’ To cast light on this, we invited papers, predominantly from members of our Editorial Board, to engage with a diverse set of debates ranging from environmental regulation, policy instruments and policy design to learning, transition strategies and innovation in environmental governance. They were asked to review the state of the art within their respective fields of research and set out future research agendas. In this section, we provide a themed overview of some of these new research agendas to guide the Journal’s future publication strategy and profile.

JEPP has tended to host a wide range of environmental policy and planning research, with a great diversity in how our authors have framed their issues. Despite this broad coverage, some of the authors in this Special Issue have been able to identify important threads of ongoing or emerging debates in the pages of JEPP. For example, in his contribution, van der Heijden (Citation2020) surveys JEPP’s contributions to the scholarship on environmental regulation. Given that statutory regulation is still dominant in environmental policy and planning, his finding that JEPP has published relatively few studies on regulation is somewhat unexpected. Pacheco-Vega (Citation2020) as well as Pedersen et al. (Citation2020) address the issue of policy instrument mixes. While both contributions acknowledge that papers published in JEPP do engage with this field of research, they argue that as a key aspect of effective governance, there could be enhanced engagement with research into this dimension of environmental policy. For instance, Pacheco-Vega (Citation2020) finds little coverage of environmental regulation and policy instruments in the Global South and therefore suggests that JEPP should attempt to widen its geographical coverage. Finally, Metze (Citation2020) conduct a systematic review of visualization studies and find that JEPP has not yet made a significant contribution to in this emerging field of scholarship. They show that over the last two decades, more and more studies have demonstrated that visualization plays a role in data-communication, influences decision making, public perception, public participation, and knowledge co-creation, and recommend that JEPP seek more manuscripts in this area.

Some of the contributions to this anniversary issue suggest specific areas in which JEPP should strengthen its publication profile. Newig and Rose (Citation2020) argue that to produce reliable knowledge and to become credible in the realm of policy and planning praxis, environmental governance, policy and planning research needs to be refocussed. They argue that this should emphasize the need to build foundations for cumulating evidence, which can lead to more effective scientific and political progress. They propose an agenda for reform covering the development of consensus around a canon of definitions, while being open to reinterpretations and novel concepts. Van der Heijden (Citation2020) suggests more engagement with the research on conventional forms of environmental regulation, questions why some traditional forms of regulation are still dominant and encourages deeper engagement with the foundational texts of regulation literature. Pacheco-Vega (Citation2020) also highlights further theoretical development as a task, suggesting a need to better understand cross-scalar dynamics of regulatory governance, including those dynamics that emerge when a regulatory governance arrangement crosses from one scale to another. Flynn et al. (Citation2020) explore inherent and ever-shifting tensions between economic and environmental imperatives in relation to the emerging governance of people and economic development in present-day China. They depict an environmental state that is interacting with a host of complex environmental problems, which can call upon a wide range of state interventions and engage with a variety of other state and non-state actors. As such, they uncover the emergence of a scale-specific, multi-faceted form of environmental governance and in doing so, call for a vibrant research agenda that makes the local environmental state an important object of analysis.

A number of papers published here advance other new approaches for environmental policy and planning research. van Assche et al. (Citation2020) present a novel framework for analyzing the formation and effects of strategies in environmental governance, drawing on elements of management studies, strategy-as-practice thinking, social systems theory and evolutionary governance theory. The paper synthesizes these ideas into a framework that conceptualizes strategies as productive fictions that require constant adaptation. Grin (Citation2020) offers guidance for practices of, and research into, the now rapidly spreading transition experiments (2nd generation) undertaken by established actors at the heart of dominant regimes, and emphasizes the need for more research on the meta-theoretical quest for a more dialectic understanding of change and stability. Feindt et al. (Citation2020) suggest a framework of Resilience Policy Design for formulating policies for promoting a resilient bio-economy by combining insights from theories of resilience of socio-ecological systems, bio-based production systems and the ‘new’ policy design perspective.

From a methodological and research design perspective, some of the papers advocate more emphasis on comparative analysis and meta-analysis. While many contributors call for more comparative research, not all contributions explicitly specify what comparative research can add to their research fields. van der Heijden (Citation2020) suggests that deeper theoretical engagement should be supported by comparative empirical studies to identify what works and what does not, and to consider what lessons learned can travel across jurisdictions. Gerlak et al. (Citation2020) identify a need for learning scholars to engage in more comparative work to look at lessons in different contexts. Grin (Citation2020) recommends comparative analysis across sectors and socio-political contexts to establish which strategies for transition experiments are successful. Newig and Rose (Citation2020) advocate stronger use of meta-analytical methods such as the case survey methodology, or systematic reviews, to cumulate published case-based evidence; and a systematic recognition of the institutional, political and social context of governance interventions, to contribute meta-analyses for revealing general patterns and trends which nonetheless vary with context.

Collectively, the papers reflect the growing complexity of environmental policy and planning characterized by multiple scales, venues and actors. They communicate a heightened urgency of today’s environmental crises from the local to global scale. The papers in this Special Issue draw attention to the capabilities and capacities needed to effectively design policy, institutionalize learning processes, and understand the impact of different policy instruments and approaches. The contributors have a strong focus on identifying where we lack sufficient knowledge about what works in environmental governance, and how to better design environmental policy.

One group of papers focus on policy instruments, highlighting the need for better knowledge about how they work, and how instrument design can be improved. van der Heijden (Citation2020) suggests that environmental regulatory research should explore the interplay between statutory and government-led regulation and other environmental policy and planning instruments, for instance the complementarity between mandatory and voluntary regulation and how transnational regulatory challenges can be addressed in collaborative arrangements between national governments and non-governmental actors. Lo et al. (Citation2020) call for more research on the outcomes of regulatory enforcement by expanding research on firm-level compliance with regulatory measures, including exploring why organizations develop different compliance strategies and how these affect regulatory performance. They also identify a need for a better understanding of how different enforcement tools can complement each other, as well as a need for better analytical frameworks to generate knowledge on how environmental non-governmental organizations perform as watchdogs in environmental regulation and interact with regulatory enforcement agencies and regulated firms. Pedersen et al. (Citation2020) consider how target group heterogeneity should be reflected in policy instrument designs. Though policy instrument mixes are already widely applied, they are rarely the outcome of a deliberate strategy that considers heterogeneity of target groups. Reviewing the limited policy mix literature, they find that complementarity between the deployed instruments has been the main research focus, not the stakeholders involved. Pacheco-Vega (Citation2020) also identifies needs to further develop the policy instrument literature by drawing on policy capacity research. He calls for more research on regulatory enforcement and instrument implementation in countries and regions where institutional capacity is relatively weak. Addressing the challenges of designing policies for a resilient bio-economy, Feindt et al. (Citation2020) set out a wider research agenda which includes analysis of institutions enabling anticipation, transparency, reflexivity and responsibility in policy design and a call for an inter- and transdisciplinary approach to policy design. Finally, they highlight the need to design policy mixes to address complex policy challenges, such as promoting a bio-economy, and that policy design should reflect sensitivity to the conditions of the policy design space.

Another group of contributions highlight the importance of how changes in the policy process can improve policy outcomes. Gerlak et al. (Citation2020) review the scholarship on learning in environmental governance to examine how this research can inform practice. Three key factors are drawn from the scholarship that may foster learning: face-to-face dialog that is open and ongoing; cross-scale linkages; and investments in institutional rules, norms, and shared strategies for intentional learning. They call for more collaborative work between learning scholars and practitioners that can inform learning research design and ultimately, shape environmental policy design. For Metze et al. (2020) visual methods in environmental policy and planning are considered important tools for knowledge co-creation, collaborative planning and participatory decision making. They direct academics to take into account the visualizations that different types of stakeholders use and (re)produce to better understand what societal actors deem important in environmental policy and planning. This can then help identify information used to spread fake-news and ‘alternative facts’ which can help develop strategies for reinforcing evidence-based sustainable environmental policies.

A third group of contributions focus on the more fundamental strategies that underpin policy and planning measures. Grin (Citation2020) suggests that testing his proposed framework around urban transitions could help understand how relations are being achieved, maintained and transformed between practices and discursive, material and institutional structures. van Assche et al. (Citation2020) call for research to better discern how insights on strategies for environmental governance can better inform and integrate different policy domains (water, land, forestry, climate etc.). Jacob and Ekins (Citation2020) suggest there is a need to create knowledge bases of social and institutional innovation, analyze how social innovation can feed into policy innovation and provide the evidence needed for designing regulatory experiments. In uncovering the emergence of a multi-faceted local environmental state, Flynn et al. (Citation2020) show that the local state can have a markedly different environmental agenda and practices from national environmental policies, highlighting the need to know more about the opportunities and constraints of local agency in environmental governance.

We thank all the contributors for their stimulating insights and taken together, these papers remind us of how far we must still travel on the road to sustainable environmental governance. In pursuing research in support of that goal, we need to be thinking more about how our individual research can cumulatively contribute to building a common body of knowledge and evidence, knowing that there is a great need for policy-relevant research (Newig & Rose, Citation2020). Although many of us expect our research to be policy-relevant, we often neglect to consider how to most effectively communicate this to those actors that can best apply it. We also need to recognize the role of context more acutely in the design and implementation of environmental policies and approaches. There are no panaceas or formulaic responses for environmental problems, or solutions championing one method of analysis, discourse, or form of governance (van Assche et al., Citation2020). Rather, the task ahead is to better question why we continue to reproduce states of unsustainability and how we can more effectively promote diversity and experimentation to address our most complex environmental challenges.

4. JEPP: into the future

Since the inception of JEPP, the field of environmental policy and planning has become both broader and more specialized at the same time. Issues of climate change, resource scarcity and biodiversity loss have become so pervasive that they now affect literally all areas of public policy and planning. Meanwhile, differences in the scale and characteristics of environmental problems and social-ecological contexts have led to a broad array of different agendas, policy approaches and governance arrangements with enormous variation across problem areas, geographies and polities. What the early articulations of ecological modernization formulated as a programmatic statement – the integration of environmental concerns into all areas of policy and planning – is now an inescapable condition, whether acknowledged or not. At the same time, broader developments such as globalization and digitalization, the rise of populism and political polarization, or the crisis of epistemic authority and representative liberal democracy affect environmental policy and planning, too. With economic development, the forefront of environmental problems has now moved to the Global South, and scholarship in our field needs to move along. The emerging temporal and spatial scales that characterize the drivers and mechanisms of environmental issues – from transnational value chains to telecoupling and global commons – require and generate novel spaces of environmental policies and planning. In response, well-established concepts and paradigms such as sustainable development are reinterpreted in novel contexts. Old themes of ecological modernization give way to novel concerns about system transformation and transitions, resilience, adaptive governance and policy learning. In complex, multi-institutional or insufficiently institutionalized contexts, reflexive and critical approaches to environmental governance approaches are becoming more urgent than ever.

Ever since its start, JEPP has aimed to publish papers that critically engage with theories and analytical approaches which can be applied in environmental policy or planning studies and thus contribute to broader debates. Descriptive narratives, case studies and analyses not engaging with such theories and debates are usually not considered for publication. This is important, as contemporary societies are facing many environmental challenges, for example climate change, loss of biodiversity, a nitrogen crisis (Rockström et al., Citation2009), often combined with lasting poverty and decreasing social and political equity (Raworth, Citation2017). A linear knowledge model in which academics ‘speak truth to power’ is no longer sufficient and straightforward solutions are not the answer; rather academics can offer reflective and critical ways of understanding current systems and policy design alternatives. By combining normative theories with sound empirical studies, established analytical approaches and understandings can be challenged, silos be crossed, and knowledge co-created. Reflections and critiques based on normative theories offer the possibility to contribute to formulating more democratic policy and planning alternatives, which are usually more inclusive, transparent, accountable, and just. Critical perspectives are urgent, as these may reveal biases, assumptions, and blind spots that are being reproduced in dominant environmental research and governance practices. Critical approaches complement the current more technocratic, institutional and actor-oriented approaches of environmental policy and planning. In addition, they create room to study and contribute to the democratic quality of the environmental governance (see Special Issue, Pickering et al., Citation2020), for example through reflexive governance (see Special Issue, Feindt & Weiland, Citation2018) and further development of theoretical thinking about environmental and energy justice (Special Issue in preparation).

The contributions to this anniversary Special Issue address some of the major challenges in transitioning democratically to sustainable societies and low carbon economies. They highlight some key challenges and provide insights into how these challenges may be addressed. While there is relatively rich body of knowledge on what needs to be done to transform societies and economies in terms of technological solutions and behavioural changes, there is still a considerable knowledge gap in terms of which societal conditions must be brought about to coordinate mutually reinforcing change in order to enable a desirable transition. Engaging with debates on environmental governance, regulation, learning, policy design, instruments and transition strategies, the contributions situate themselves in key debates in environmental policy and planning and the challenges that policy makers and planners face. The contributions to this Special Issue allow us to take stock of the state of the art within the themes addressed in each paper, outline the major policy and planning challenges and set future research agendas. These agendas are likely to feed into the Journal publication strategy in the future, for instance in the form of Special Issue projects, whilst maintaining an agenda of openness and diversity which is the hallmark of the Journal. In the coming years, we aim to maintain our critical perspective and diversity and continue to nurture interdisciplinarity and the diversity of the theoretical approaches and issues covered. We aim to further strengthen the global nature of the Journal, particularly with contributions from the Global South and Asia. Furthermore, the complex questions of sustainable transitions require systemic approaches and transdisciplinary collaborations that better take into account societal responses, experiential knowledge and different interpretations.

Acknowledgments

The Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning exists as a community, and the Editors would like to acknowledge the large number of individuals that contribute to its ongoing vibrancy. We thank all the former Editors, our Editorial Board, authors and the thousands of peer reviewers that play such an important role in maintaining the rigour of the research we publish. We thank our publisher, Taylor and Francis and their many employees in production, management and promotion for their contribution to the Journal. We also thank the Editorial Managers that have juggled the administration of JEPP with other university tasks: Denise Philips (Cardiff), Mirjam Cervat (Wageningen) and the current Manager, Nick Johnston (Belfast). Finally, we are grateful to the authors of this anniversary Special Issue who joined us for a special workshop in Berlin in September 2019, hosted by the Integrative Research Institute on Transformations of Human-Environment Systems (IRI THESys), Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Geraint Ellis is Professor of Environmental Planning in the School of the Natural and Built Environment at Queen's University Belfast.

Andrea K. Gerlak is Professor in the School of Geography, Development and the Environment at The University of Arizona.

Carsten Daugbjerg is Professor in the Department of Food and Resource Economics at University of Copenhagen.

Peter H. Feindt is Professor of Agricultural and Food Policy at the Thaer-Institute for Agricultural and Horticultural Sciences, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany.

Tamara Metze is Associate Professor in Public Administration and Policy at the Department of Social Sciences at Wageningen University.

Xun Wu is a Professor at the Division of Public Policy at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

References

- Avelino, F., Grin, J., Pel, B., & Jhagroe, S. (2016). The politics of sustainability transitions. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), 557–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2016.1216782

- Avelino, F., & Wittmayer, J. M. (2016). Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: A multi-actor perspective. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), 628–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1112259

- Bauer, A., Feichtinger, J., & Steurer, R. (2012). The governance of climate change adaptation in 10 OECD countries: Challenges and approaches. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 14(3), 279–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2012.707406

- Berger, G., Feindt, P. H., Holden, E., & Rubik, F. (2014). Sustainable mobility—challenges for a complex transition. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 16(3), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2014.954077

- Bruntland, G. H. (1987). Report of the World Commission on environment and development; our common future, Bruntland report. New York: UN Documents.

- Cass, N., Walker, G., & Devine-Wright, P. (2010). Good neighbours, public relations and bribes: The politics and perceptions of community benefit provision in renewable energy development in the UK. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 12(3), 255–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2010.509558

- Chilvers, J., & Longhurst, N. (2016). Participation in transition (s): Reconceiving public engagements in energy transitions as co-produced, emergent and diverse. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), 585–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1110483

- Chilvers, J., & Longhurst, N. (2016). Participation in transition (s): Reconceiving public engagements in energy transitions as coproduced, emergent and diverse. Journal of Environmental Policy, 18(5), 585–607.

- Cowell, R., Ellis, G., Sherry-Brennan, F., Strachan, P. A., & Toke, D. (2017). Rescaling the governance of renewable energy: Lessons from the UK devolution experience. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 19(5), 480–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1008437

- Cowell, R., & Flynn, F. (2006). Editorial – seven years of JEPP. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 8(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080600664430

- Dodge, J., & Metze, T. (2017). Hydraulic fracturing as an interpretive policy problem: Lessons on energy controversies in Europe and the U.S.A. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 19(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2016.1277947

- Feindt, P. H., & Oels, A. (2005). Does discourse matter? Discourse analysis in environmental policy making. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 7(3), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080500339638

- Feindt, P. H., Proestou, M., & Daedlow, K. (2020). Resilience and policy design in the emerging bioeconomy-the RPD framework and the changing role of energy crop systems in Germany. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning.

- Feindt, P. H., & Weiland, S. (2018). Reflexive governance: Exploring the concept and assessing its critical potential for sustainable development. Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 20(6), 661–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2018.1532562

- Flynn, A., Cowell, R., Marsden, T., & Bishop, K. (1999). Editorial introduction: Questions for environmental policy and planning. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/714038520

- Flynn, A., Xie, L., & Hacking, N. (2020). Governing people, governing places: Advancing the Protean environmental state in China. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1806048

- Funtowicz, S. O., & Ravetz, J. R. (1995). Planning and decision-making in an uncertain world: the challenge of post-normal science. In Natural risk and civil protection (pp. 531–554).

- Gerlak, A. K., & Heikkila, T. (2019). Tackling key challenges around learning in environmental governance. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(3), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1633031

- Gerlak, A. K., Heikkila, T., & Newig, J. (2020). Learning in environmental governance: Opportunities for translating theory to practice. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1776100

- Grin, J. (2020). ‘Doing’ system innovations from within the heart of the regime. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1776099

- Gupta, A., In Boas, I., & Oosterveer, P. (2020). Transparency in global sustainability governance: To what effect? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(1), 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1709281

- Haggett, C. (2008). Over the sea and far away? A consideration of the planning, politics and public perception of offshore wind farms. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 10(3), 289–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080802242787

- Hajer, M. (1995). The politics of environmental discourse: Ecological modernization and the policy process. Oxford University Press.

- Hajer, M., & Versteeg, W. (2005). A decade of discourse analysis of environmental politics: Achievements, challenges, perspectives. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 7(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080500339646

- Hindmarsh, R., & Matthews, C. (2008). Deliberative speak at the turbine face: Community engagement, wind farms, and renewable energy transitions, in Australia. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 10(3), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080802242662

- Jacob, K., & Ekins, P. (2020). Environmental policy, innovation and transformation: Affirmative or disruptive? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1793745

- Kidd, S., & Ellis, G. (2012). From the land to sea and back again? Using terrestrial planning to understand the process of marine spatial planning. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 14(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2012.662382

- Lange, P., Driessen, P. P., Sauer, A., Bornemann, B., & Burger, P. (2013). Governing towards sustainability—conceptualizing modes of governance. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 15(3), 403–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2013.769414

- Leipold, S., Feindt, P. H., Winkel, G., & Keller, R. (2019). Discourse analysis of environmental policy revisited: Traditions, trends, perspectives. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(5), 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1660462

- Lo, C. W. H., Liu, N., Pang, X., & Li, P. H. Y. (2020). Unpacking the complexity of environmental regulatory governance in a globalizing world: A critical review for research agenda setting. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1767550

- Metze, T. (2020). Visualization in environmental policy and planning: A systematic review and research agenda. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1798751

- Newig, J., Jan-Peter Voß, J., & Monstadt, J. (2007). Editorial: Governance for sustainable development in the face of ambivalence. Uncertainty and Distributed Power: An Introduction. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 9(3–4), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080701622832

- Newig, J., & Moss, T. (2017). Scale in environmental governance: Moving from concepts and cases to consolidation. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 19(5), 473–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2017.1390926

- Newig, J., & Rose, M. (2020). Cumulating evidence in environmental governance, policy and planning research: Towards a research reform agenda. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1767551

- Osunmuyiwa, O., Biermann, F., & Kalfagianni, A. (2018). Applying the multi-level perspective on socio-technical transitions to rentier states: The case of renewable energy transitions in Nigeria. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 20(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2017.1343134

- Pacheco-Vega, R. (2020). Environmental regulation, governance, and policy instruments, 20 years after the stick, carrot, and sermon typology. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1792862

- Pedersen, A. B., Nielsen, H. Ø., & Daugbjerg, C. (2020). Environmental policy mixes and target group heterogeneity: Analysing Danish farmers’ responses to the pesticide taxes. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1806047

- Pickering, P., Bäckstrand, K., & Schlosberg, D. (2020). Between environmental and ecological democracy: Theory and practice at the democracy-environment nexus. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1703276

- Ran, R. (2013). Perverse incentive structure and policy implementation gap in China’s local environmental politics. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 15(1), 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2012.752186

- Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å, Chapin, F. S., Lambin, E. F., Lenton, T. M., Scheffer, M., Folke, C., Schellnhuber, H. J., & Nykvist, B. (2009). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461(7263), 472–475. https://doi.org/10.1038/461472a

- Steffen, W., Rockström, J., Richardson, K., Lenton, T. M., Folke, C., Liverman, D., Summerhayes, C. P., Barnosky, A. D., Cornell, S. E., Crucifix, M., & Donges, J. F. (2018). Trajectories of the earth system in the anthropocene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(33), 8252–8259. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1810141115

- Storbjörk, S. (2010). ‘It takes more to get a ship to change course’: Barriers for organizational learning and local climate adaptation in Sweden. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 12(3), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2010.505414

- Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., & Duineveld, M. (2017). The will to knowledge: Natural resource management and power/knowledge dynamics. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 19(3), 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2017.1336927

- Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., Gruezmacher, M., & Duineveld, M. (2020). Rethinking strategy in environmental governance. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1768834

- van der Heijden, J.. 2020. Environmental regulation in the twenty-first century: A systematic review of (and critical research agenda for) JEPP scholarship. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1767549