ABSTRACT

This paper explores limitations and potentials of the public space for participation in Danish municipal wind energy planning. Although the Danish procedure for involving citizens in wind energy developments is often praised for its participatory merits, the approach is not without problems. Based on explorative case study research of three Danish wind energy projects at the planning stage, and qualitative interviews with both citizens and planners, the paper reveals shortcomings in terms of perceived procedural fairness and the powerful role ascribed to developers in a planning process. A general conclusion is that the implementation of limited participation requirements of the inherent invited space decouples citizens’ perspectives while providing a space for economic and strategic interests that is closed in its character. However, the study also localizes public input which is not limited to formal participation mechanisms. Self-initiated participation representing a ‘claimed’, ‘uninvited’ and ‘self-organized’ space exerts pressure from the outside and may carry important answers to future energy challenges. The paper suggests that a successful nurturing of such potentials could help to reconfigure a public space that encourages collective reflection between established and oppositional understandings of wind energy and society.

1. Introduction

Protests against the siting of large wind energy (WE) facilities have put pressure on planning authorities to put more emphasis on public participation. This shift includes a recognition of the complexity of public attitudes and a desire to avoid conflicts in decision-making processes (Cuppen, Citation2018). Since opposition is often perceived as a ‘bottleneck’ in the planning system (Ellis et al., Citation2009), the participatory approach has, as Kaza (Citation2006, p. 256) contended, ‘become institutionalized as a method of good planning practice’. The growing body of literature also points to the importance of local values, knowledge and contextual factors in shaping contestations. While previous research has often been aimed at a better understanding of local opposition to overcome or avoid it (Aitken, Citation2010; Batel, Citation2020), more nuanced insights have led to the acknowledgement that local people may be ‘local experts’ and engaging them and their contextualized knowledge of the local area would not only overcome a 'democratic deficit' (Bell et al., Citation2005) in renewable energy technology (RET) decisions, but would also lead to locally anchored societal and environmentally sustainable solutions (Chilvers et al., Citation2005; Leibenath et al., Citation2016; Natarajan et al., Citation2018).

Research on this topic is therefore not new, and some sort of consensus exists that new initiatives for citizen engagement in planning processes are required. An overall concern with justice, fairness, trust, inclusion and empowerment in planning procedures has led to increased creativity in the design of new participatory spaces for citizen engagement including ‘good practice’ guidelines for enhanced participation processes.

This paper focuses on wind farm developments in Denmark for which such guidelines can also be found and whose approach to community participation within wind farm planning has been highlighted as a positive example from which other countries could learn (e.g. Aitken et al., Citation2016; Szarka, Citation2006; Toke et al., Citation2008). Likewise, Danish authorities share this general praise and consider Danish standards of public involvement to be rather high. This is particularly described in a booklet from the Danish Energy Agency (Citation2009, p. 8), which describes guidelines for ‘the good process’ in Danish WE planning stating that ‘the development of wind power in Denmark has been characterized by strong public involvement’.

Despite this self-righteous image, we demonstrate that the Danish planning procedures do not possess an enduring learning potential. Similar to developments in other parts of the world (e.g. Walker & Baxter, Citation2017), the Danish approach has also motivated a social movement opposed to WE (Clausen & Rudolph, Citation2019; Larsen et al., Citation2018; Kirkegaard & Nyborg, Citation2020) and several municipalities have recently declared their unwillingness to host further WE projects on land (DE, Citation2019).

Such experiences point to the significance of procedural justice, but question that simply creating new participatory arrangements will result in greater inclusion (Clausen, Citation2017; Cornwall, Citation2008). The notion of procedural justice refers to fairness in the process of decision-making (e.g. access to information, recognition and inclusion of affected stakeholders) and is related to the ability of people who are affected by a decision to participate as equals in the decisions-making process (e.g. Gross, Citation2007; Ottinger et al., Citation2014; Simcock, Citation2016). However, in practice there is often a nuanced discrepancy between the legal procedures and the perceived fairness of the actual process associated with the implementation of the legal procedures (Wolsink, Citation2007).

As argued by Gaventa (Citation2006, p. 23), much seems to depend on power relations which surround and imbue the democratic spaces in question. New participatory arenas which may appear as innovations are often fashioned out of existing forms through a process of institutional bricolage, drawing on existing relationships, hierarchies and rules of the game (Cornwall, Citation2004a, p. 2). Hence, participation has also been argued to be at best deeply naïve (Cruikshank, Citation1999) and at worst a ‘tyranny’ (Cooke & Kothari, Citation2001; Hickey & Mohan, Citation2004) of a manipulative exercise of power. Critical questions need therefore be directed towards the participatory procedures, which at first glance represents good practice guidelines.

The aim of this paper is to scrutinize the participatory capabilities of the Danish WE planning process and elucidate what participation actually means and entails in light of the praised participation model and increasing local opposition. This touches also upon the fundamental question whether it is meaningful to talk about public participation in WE planning at all, if engagement practices are heavily woven into strategic power interests.

By addressing these issues, the paper offers two contributions: a) a nuanced understanding of power mechanisms in and the dynamic interaction of diverse forms of formal and informal participatory spaces at stake in participatory procedures and b) a multi-case study critique of the wider participatory discourse related to ‘the good process’ in Danish WE development. In order to scrutinize the participation process, we draw primarily on qualitative interviews with local residents and municipal planners in three case areas, supplemented by desk-based research, including the analysis of consultation responses. Theoretically, the paper is inspired by theories of participation (e.g. Arnstein, Citation1969; Cooke & Kothari, Citation2001; Hickey & Mohan, Citation2004) and public spaces for participation (e.g. Berry et al., Citation2019; Cornwall, Citation2004a; Gaventa, Citation2006).

In the remainder of the paper, we first present theoretical considerations about spaces for participation before describing key elements of the formal planning procedure for wind farms in Denmark. We then explain the research methodology and present the empirical findings. In the discussion, we elaborate on the manifestations of three spatial categories – invited, closed and claimed space – each of which describes a spatial dimension of public participation in the planning process, and contemplate over wider implications.

2. Spaces for participation

The notion of space (cf. Lefebvre, Citation1991) is widely used across the literatures on power, policy, democracy and citizen action (Cornwall, Citation2004a; Gaventa, Citation2006; Kersting, Citation2013). This is due to the growing recognition that no participation is independent of its social context (Berry et al., Citation2019), which influences the direction of participation – who participates (and who does not), what can and cannot be discussed, what competencies and forms of knowledge are prioritized among the participants, and what influence participants have on decision-making. Hence, as a metaphorical concept and a literal descriptor of arenas where people gather, space indicates a ‘room for manoeuvre’ (Clay & Schaffer, Citation1984) that can be emptied or filled, permeable or sealed. A space can be an opening, an invitation to speak or act, but it can also be shut, voided of meaning, or depopulated as people turn their attention elsewhere (Cornwall, Citation2004a). Thus, participation as freedom is not only the right to participate effectively in a given space, but also the right to shape that space (Gaventa, Citation2006).

In this paper ‘spaces’ for participation are considered as opportunities, moments and channels through which citizens can act to potentially effect policies, discourses, decisions and relationships that affect their lives and interests (Gaventa, Citation2006, p. 26). In particular, John Gaventa’s (Citation2006) terminology is used as an overall analytical framework to make sense of what participation actually means and entails in Danish municipal WE planning. In doing so, we also align with Chilvers et al.’s (Citation2018, p. 200) call for understanding ‘the dynamics of diverse interrelating collectives and spaces of participation and their interactions with wider systems and political cultures’. Gaventa’s (Citation2006) terminology suggests a continuum of spaces – closed, invited and claimed spaces:

Closed spaces refer to decisions made by a set of actors behind closed doors, without any pretense of broadening the boundaries for inclusion (Gaventa, Citation2006). These are ‘provided’ and technical-rational spaces (Lefebvre, Citation1991) in the sense that elites (bureaucrats, experts or elected representatives) make decisions and provide services to ‘the people’, without the need for broader consultation or involvement. While simply informing people of plans that have been made, this form of engagement involves a one-way flow of ‘information provisions’ (Chilvers et al., Citation2005), such as exhibitions, websites, factsheets, site visits, leaflets, mailings and letters. Objectives of this form of ‘engagement’ appear to be most focused on complying with legal minimum criteria – the ‘bottom-line’ approach to engagement and the ‘minimum-level allowed by law’ (Chilvers et al., Citation2005, p. 28; Haggett, Citation2011). Hence they are also ‘juridical spaces’ (Dahlberg, Citation2016) where the legal framework sets the boundaries of what is eligible to bring into the debate and how (Williams, Citation2012). Based on the rationale to complete planning quickly and efficiently (e.g. Walker & Baxter, Citation2017) and to avoid the ‘problems’ of opposition (Cowell, Citation2007), this form of engagement follows a ‘decide-announce-defend’ tradition in planning (Wolsink, Citation2000; Bell et al., Citation2005), where licit arguments nullify all other arguments beyond the legal framework (Dahlberg, Citation2016).

Alternatively, invited spaces are created to move from closed spaces to more ‘open’ ones (Gaventa, Citation2006). People are invited by various kinds of authorities, be they governmental, supranational agencies or non-governmental organizations to participate in spaces that are institutionalized through various forms of consultation. Methods range from written consultations, public hearings, public meetings, dialogue groups, round tables to consensus conferences, where a ‘two-way communication’ between ‘sponsors’ (e.g. governments, municipalities or companies) and ‘public representatives’ is pursued (Rowe & Frewer, Citation2005, pp. 281–282). Within energy decision-making, environmental impact assessments (EIA) and public inquiry mechanisms are commonly used as invited spaces (Berry et al., Citation2019, p. 3). Despite different approaches, invited participation often falls under two overall rationales – a normative and an instrumental one (Fiorino, Citation1990). Following a normative and Habermasian inspired position, the crucial qualities of a successful process are those of ‘dialogue’, ‘fairness’, ‘trust’, ‘consensus’ and the inclusion of relevant viewpoints in the production of outcomes (Cass, Citation2006) – e.g. procedural justice. Following a more instrumental position, public participation can also be conducted as means to a particular end, as decisions are considered more likely to be accepted if stakeholders are involved in the decision-making process (Cuppen, Citation2018).

Some scholars have pointed out how invited forms of participatory spaces can be gainful from a procedural and contextual perspective (Haggett, Citation2011; Walker & Baxter, Citation2017). Inviting neighbors to inform and have their feedback on planned WE-installations has been acknowledged to have the potential to create experiences of procedural fairness later on.

However, invited participation has also been critiqued for not being true (Cooke & Kothari, Citation2001; Cornwall, Citation2004a; Bora & Hausendorf, Citation2006) or even ‘false’ (Hjerpe et al., Citation2018) participation, as it may leave open whether dialogue leads to empowerment and legitimacy (Bidwell, Citation2016; Cuppen, Citation2018). Since the power to give preference to certain forms of ‘knowledge’ and particular perspectives of the ‘planning problem’ (Ellis et al. Citation2009) belong to the inviting party, invited spaces tend to exclude emergent values that do not ‘fit’ into existing objectives (Aitken et al., Citation2016; Cuppen, Citation2018; Haggett, Citation2011). This critique complies with Arnstein’s (Citation1969) argument that tokenistic forms of participation, such as information and consultation can be valuable first steps towards participation, but with no further contribution, they may serve as empty rituals with little impact. For instance, written consultations have been accused of being nothing but a well-honed tool for engineering consent to projects and programs whose frameworks have already been determined in advance (Hildyard et al., Citation2001). Also, processes focused on instrumental goals may be more concerned with including groups that have power to assist or obstruct the project; e.g. a process convener seeking out groups with political capital or legal rights to an affected resource (Bidwell, Citation2016). This can lead to a ‘legitimation crisis’ (Habermas, Citation1979) – a decline in the general confidence of administrative functions, institutions or leadership, and to the intimidation of public space (Sennett, Citation1976) as private affairs (e.g. represented by landowners) are assigned a particularly exalted role in the planning process.

Thirdly, there are spaces which are claimed by less powerful actors from or against the power holders (Gaventa, Citation2006). Such claimed spaces emerge through popular mobilization and range from spaces created by social movements and neighborhood coalitions to those simply involving physical places where people gather to debate and exert pressure from outside the political process. This involves various tactics, or counter-actions (DeCerteau, Citation1984), such as petitions, complaints, letters and media outreach to influence the decision-making process (Berry et al., Citation2019), as well as the organization of physical meetings or the start-up of own energy projects (Seyfang & Haxeltine, Citation2012). In contrast to invited participation, the public engagement is ‘uninvited’ (Wynne, Citation2007), ‘organic’ (Cornwall, Citation2004a) and ‘self-organized’ (Cuppen, Citation2018) and usually arises when people lack confidence in the political public space (Kersting, Citation2013). It entails a demand for a more substantive participation (Fiorino, Citation1990) – e.g. addressing citizens as ‘local experts’ (Cass, Citation2006; Haggett, Citation2011) in possession of everyday knowledge important to the planning process. In matters of local RET governance agonistic theory (Mouffe, Citation1999) has been highlighted to cover this approach (Barry & Ellis, Citation2011; Cuppen, Citation2018). What makes democracy work are the ‘differences’ in positions, in cultures and understandings which resist consensus and therefore surface the disagreements existing among the members of a community. As they target fixed procedures of institutionalized participation to either radically reject or suggest new modes of framing RET projects, they take the form of ‘counter-spaces’ (Lefebvre, Citation1991, p. 383), which can be platform for creating new political spaces through which traditional modes of operating energy systems are reshaped (Cuppen, Citation2018, p. 30).

Of particular importance for the use of a spatial terminology for participation in WE planning is the dynamic character of ‘space’ (Lefebvre, Citation1991, p. 24). Diverse forms of participation are interacting within a shared political context and with no strict boundaries in between (Berry et al., Citation2019). Since spaces are constantly opening and closing through struggles for legitimacy and resistance, co-option and transformation, all forms and meanings of participation may in practice be found in a single project or process at different stages (Cornwall, Citation2008, p. 274; Aitken et al., Citation2016).

3. The ‘good’ Danish planning process

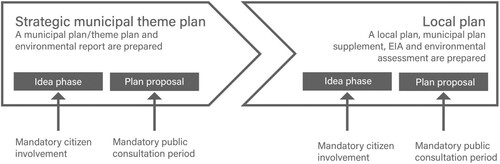

The integration of public participation in the planning process for wind farms in Denmark is a legal requirement currently mandated by the updated Planning ActFootnote1 of 2018. The planning authority for onshore wind turbines for up to 150 meters rests with the municipalities (DEA, Citation2009, p. 12). The Planning Act is divided into a two-tier planning process at the municipal level: ‘the strategic municipal theme plan’ and ‘the local plans’ (). Both stages include public participation procedures arranged by the local authorities in terms of consultation periods of 4–8 weeks in which written comments to the draft plans can be submitted (Armeni & Tegner Anker, Citation2019).

Figure 1. The phased citizen involvement in the planning process. Replicated from the Danish Environmental Ministry, DEM (Citation2013). Graphics: Saara Maria Ojanen.

The theme plan is part of the overall strategic municipality plan, with which different land uses in the municipality are handled, including locations of wind turbines. It identifies and designates potential wind turbine areas including framework conditions (i.e. capacities, number and height of turbines).Footnote2 Once the municipality has identified a number of potentially suitable wind farm areas, it is mandatory to involve citizens, whereas the degree of involvement is up to the municipality and usually includes a citizen meeting (i.e. public hearing) (DEM, Citation2013). The aim of this so-called ‘idea’ or ‘debate phase’ at the strategic level is to inform citizen and allow them to debate the plans with professionals and politicians. After the idea phase the municipality has to decide whether to include the areas in the municipal plan or not, and the draft plan then undergoes a public consultation period which may result in a revision of the plan (DEM, Citation2013).

In a second step, a specific wind farm project usually requires the adoption of a local plan that specifies the design and layout of the proposed wind farm (Tegner Anker & Jørgensen, Citation2015, p. 11). The municipality is responsible for the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process, but usually assigns this task to the developer. The local plan and the required EIA permit also have to undergo a mandatory second idea phase consultation process of 2–4 weeks to gather ideas and suggestions for the specific project. This is followed by optional meetings with local residents and a period for written consultations. Based on the feedback from the written responses, the municipality draws up the scope of the EIA, adjusts the project accordingly and decides on the necessary mitigation measures to gain the EIA approval (DEA, Citation2015, p. 18). The EIA report and the local plan proposal are then submitted for mandatory public consultation for at least eight weeks. A public hearing (citizen meeting) about the specific project is not mandatory but is often combined with a mandatory citizen meeting in which the developer is obliged to inform about the property value loss and co-ownership schemes. In summary, the involvement of the public consists of consultation periods at both the strategic and specific project level, whereas additional public meetings are not mandatory but common practice.

According to a code of conduct developed by some of the central players in Danish WE development (LGD et al., Citation2009), the standard procedure for involving citizens is deemed to have the potential for constituting ‘a good process’. It is stipulated how the dialogue between the involved parties should start early, preferably from the initial identification of the different wind regions and in the early design of the specific wind turbine projects, so that ‘all actors will have a chance to be heard through the decision-making processes’ (LGD et al., Citation2009, p. 8). The first phase (idea phase) is described as a phase where ‘there is in particular room for good ideas’, where ‘the field is open’, and where ‘active participation of citizens and developers is considered very important’, because ‘it means that the municipality can work on a solid and locally anchored wind turbine planning’ (LGD et al., Citation2009, p. 8) in the second phase. Thus, the ambition is to ‘create a space for a constructive and active participation with room for all types of opinions and ideas for the projects’ (LGD et al., Citation2009, p. 5), whereas municipalities and developers should be striving for good information and active citizen involvement (DBA, Citation2015; DEM, Citation2013; DNA, Citation2014a, Citation2014b).

Likewise, academic considerations have hinted at the alleged merits of the Danish planning process. For example, compared with the UK, it has been noticed in a review, how ‘in Denmark, at least formally, community engagement takes place at a much earlier phase and is often focused on spatial planning and zoning rather than particular proposed developments’ and that with ‘greater public engagement in early planning and/or spatial planning processes there may be more opportunities for substantive changes’ (Aitken et al., Citation2016, p. 572). However, these judgements are merely based on the formal participation procedures without considering their practical implementation and looking into outcomes regarding perceived fairness.

4. Methodology

Three Danish onshore WE projects at the planning stage were selected as case studies for an in-depth examination and analysis. The main selection criteria for the three cases, Nørhede-Hjortmose (22 wind turbines with a total capacity of 73MW), Ulvemosen (10 turbines, 33MW) and Nørrekær Enge (36 turbines, 130MW), all located in rural areas in Jutland (), were the richness of the data, variety in size and ownership configuration, and the representativity of the formal planning process for developing WE projects in Denmark.

All three cases were part of a larger fieldwork undertaken between 2015 and 2017 as part of the research project Wind2050Footnote3 and draw primarily on qualitative interviews with local residents. Hence, the emphasis is placed on the residents’ perspectives, which are supplemented by interviews with planners in the same three case areas. Additionally, interviews with planners were also taken from the SEP projectFootnote4 that focused on eight municipalities with WE development located in the same rural parts of Denmark as the three cases and including one of the three case studies. Besides interviews, observations at public meetings and (pre-)consultation responses serve as secondary data to cross-check information from interviews and to verify reflections presented in the interviews. Overall, the article draws on individual semi-structured interviews (23 local residents and 7 planners); 6 focus group interviews (24 local residents and 1 with 2 planners), observations (2 public hearing meetings); and desk-based research (document analyses of 68 pre-consultation responses and 169 consultation responses to EIAs and additional interviews with 12 planners in 8 municipalities - the SEP project). (see ).

Table 1. Case study characteristics.

The semi-structured open-ended interviews intended to identify how local residents and planners experienced the participatory process, including concrete practical experiences with the planning process, i.e. location, duration and procedural aspects and existing shortcomings of and potentials for public involvement. The recruitment of interviewees was driven by a curiosity to uncover the complexity of attitudes to the participatory procedure. The approach was open and exploratory, and the selection of local residents was undertaken to include a maximum of representation related to profession, gender and age. It was a priority to talk to both landowners and non-landowners and talk to residents who were both positive and negative about the projects. Some residents were contacted because they had made themselves particularly noticeable in the debate. Others were contacted following snowball sampling, where the contact of one person leads on to the next. The recruitment of planners was based on the criteria of being most intensely involved in the respective processes. Interviews lasted 1–2 h and were conducted in the private homes of the interviewees or, in the case of planners, at the municipal offices or over the phone. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim in most cases. Quotes presented in the empirical section were translated from Danish to English and cross-checked by all authors.

Interviews and secondary data were analyzed using descriptive analysis and methods informed by grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967) to let observations speak for themselves and let theories emerge from an inductive analysis that exposed themes from the data. Accordingly, the analysis was divided into three main steps (a) highlighting the issues raised by the interviewees (b) comparing this material with the content of relevant documents (written consultation responses, EIA’s) and observations from public meetings to carve out arguments suggesting a common or conflicting understanding (c) revisiting the empirical themes from a theoretical perspective to assign meaning to the empirical findings. Hence, the level of knowledge was increased through cross-checking data from various perspectives to get a broader view and to address the issue of internal validity.

5. Findings

Three major themes were identified in the two first steps of the analysis of citizens’ and planners’ experience with participation processes: ‘perceived fairness of procedure’’, ‘the role of developers’ and ‘self-initiated participation’.

5.1. Perceived fairness of procedure

Despite a general sympathy for wind energy, the interviews with citizens and planners show the perception of an inadequate planning process in terms of engaging residents. This overall experience is not only about the extent to which municipalities meet the formal requirements of the planning stages, but also about the perception of more fundamental lack of fairness in these requirements.

One dimension concerns the lack of transparency in the planning processes which creates insecurity and a feeling of not being heard. Since municipal plans are only required to be published digitally, the actual announcement of the municipal or local plan is for instance regarded as insufficient. Residents do not discover that there is a plan in the making, and are often surprised when a specific WE project is in the pipeline to which they should respond, and both residents and planners point to the risk of plans rendered ‘secret’ or being ‘camouflaged’, i.e. that people may never become aware of them because they need to proactively search all information online. A woman in Ulvemosen explains:

It was my neighbor who called me first and asked if I had seen it. Afterwards there was a piece in the newspaper with very little conspicuousness saying that they started something out there. The municipality did not send anything, and the municipality also says that, well, you have to look up information yourself.

Residents also referred to themselves as being naïve in terms of believing in promises of having real influence in the process. Several describe how they researched the local plan thoroughly, and in the idea phase, they shared their information with the municipality. However, the information was not used as a starting point for a dialogue, but to refine the plan further by the municipality and developer.

Another experience is a lack of documentation and restrictions on residents’ requests for getting access to information, e.g. meetings where minutes were not taken or where minutes and other documentation (e.g. noise measurements) have been ‘lost’ or could not be delivered. As described by a woman in Nørhede-Hjortmose, residents had difficulties in getting information about the deadlines for comments in both public consultation phases, which were also considered too short and deliberately placed in very inconvenient periods:

There has been very short time to object. There were 14 days to object, and it overlapped with the Christmas holidays […] Additionally, there was only one contact person in the municipality, and he was on holiday in one out of the two weeks.

Basically, one can discuss whether we could do something extra for citizens to get actually involved in the planning process … it rapidly becomes such a token-like thing … like, then we need to have a 14-day consultation, and so we put it up on a website … then we have 2–3 diligent writers who are checking those things and come up with responses … but the majority, they never discover it.

The visualizations are made as they [turbines] will appear from the house. But we are not sitting in the kitchen all the time. Outdoor life in the garden is just as important as staying indoors. We are moving around the countryside. We go horse riding […]. The fact that people are mobile is not taken into consideration.

From the very beginning I felt like a fool. The developer had voluntarily called a meeting in the village hall. Here, the project was presented by the developer, politicians and there was also a consultant present to describe the EIA. They were top-arrogant - they laughed at us and answered in a patronizing way when we asked about things.

Those citizen meetings, it's unbelievable, you might have to meet at 7 pm and finish at 9.30 pm, and then they simply fill it up with all sorts of pro forma, so there is only half an hour for questions at the end, and then they close the meeting.

Then you got a piece of colored cardboard which gave you time to speak […] they quickly found out who knew anything and who would come up with silly questions, and they made sure that those who came up with the silly questions got more pieces of cardboard, and so they didn't get the critical questions.

But it's true, they comply with the legislation and the requirements there, that's what the municipality says all the time when you ask critical questions to them, well, we comply with current legislation, and then there is like nothing more to say. But now we have started to play by the same rules, because now we have hired this lawyer […]

It is basically strange with such a meeting, because it was all decided in advance. We could hear that, right. There was no doubt that it had to be debated a bit, but it was not much. So, I can see how opponents may feel a little … . I don’t know … not heard

5.2. The role of developers

The role of developers in the planning process reinforces the experience of a deficiency in legitimacy and accountability in the formal planning process. In all three cases, residents mention closed meetings between the municipality, landowners and developers very early in the planning process. Some residents see this as a positive expression of political support, as described by a landowner in Nørhede-Hjortmose, who himself had sold land for the project, and alluded to the conservative-neoliberal (and WE positive) political consensus in the municipality:

They were lucky, the developers at the time, because Ringkøbing-Skjern Municipality was a pure Liberal municipality. If they had come to the next municipal election, I don’t think they would have got it through.

We got around 9–10 hearings responses […] out of the 27 hearing responses […] where they said, ‘this is a super good idea’ and this was because they [developers] had promised them some money […] so you could sense […] all those consultation responses, they were quite similarly written over some template, and it’s because they [the developers] have encouraged them to do so, you know.

Then they started buying up properties. In total 12 properties have been bought. Not everyone was happy to sell, but people felt pressured because they used gangster methods. People were told that they could either choose to sell, or they could choose not to, but the turbines would come anyway. And you were told not to say anything to your neighbor, because then the contract would be canceled.

Additionally, the alleged bias of developers being granted responsibility for the EIA report makes residents question their impartiality in the EIA assessment. Since developers invest a large amount of money in the EIA assessment, residents insinuate an obligation of the municipalities to approve a project. Similarly, when developers do not live up to their formal responsibilities this leads to sharp accusations. In Nørhede-Hjortmose the lack of public information from developers was for instance made directly accountable for the fact that some residents were late in submitting their applications for value loss compensations. They complained to the municipality, but the situation became more precarious when the developer showed up in their private homes to ask them to withdraw their complaint.

In all three cases, residents reported being contacted in their private homes by developers who tried to persuade them to certain actions (e.g. selling land or avoid filing complaints) through the use of both threats and financial agreements. This leads to a widespread experience of being intimidated as boundaries between public and private space are violated. In Nørrekær Enge, this situation was also associated with developers attempting to replace public obligations with these forms of more private participation, as explained by a woman:

Then they write and invite themselves to a visit and say that they want to bring cake. But I do not want to sit in my own house and eat cake with them. We would like written answers to our questions, and they want to ‘meet with us and bring cake’.

Many people have relationships with the local developers, and they simply do not dare to say their opinion out loud. There are also cash-strapped farmers who depend on a succeeding project. We ourselves have chosen to stay out of the debate, so we do not speak in public. X (husband) works as an electrician and several of his good customers are developers. He has nothing against them personally, and it would hurt his business, if he told his opinion in public.

5.3. Self-initiated participation

The awareness that one’s argument has no real value in a technical-regulative framing leads to different forms of responses. One is apathy, as some residents choose to put up with a situation they cannot change. Others choose to get the best out of the situation by, for example, selling the land or house to developers. Some residents start, however, to pursue other channels, arguments or ways of organizing in order to get a stronger voice beyond the limited participation process.

In all three cases is witnessed the self-organization of information groups who undertake the task of informing and helping neighbors with writing consultation responses, thus potentially influencing the content of objection letters. A man in Ulvemosen explained:

You know, I have been one of those driving around and talking to pretty much everyone except the landowners, who have offered land to the turbines because they are not on my side. And pretty much everyone has expressed that they did not want this, but then there are people […] who do not get to type an email to the municipality, so I have helped with that.

In a way it's funny how the whole discussion came to focus on cranes. To be honest I also have other concerns than the turbines’ impact on bats and birds, but it was difficult to make oneself heard for such concerns, because now these animals were a theme in the EIA report.

We can only hope that the church can come more into play. There is no doubt that a signature from the Ministry of Church Affairs has more weight than us.

There was a phase where we did not talk much with the municipality but saved things up for complaints to the Nature and Environmental Appeals Board […]. We asked questions to the municipality regarding the EIA report, and asked them to explain these statements. This is again about keeping the gunpowder dry, right. Find as much as you can yourself, without delivering it to the municipality, since everything was delivered directly to [the developer].

The group applies for access to documents and looks for all possible irregularities, signs of conspiracies, signs that the municipality is in the pocket of the industry, procedural errors so that complaints can be made to the state administration and the Nature and Environmental Appeals Board […] We are dealing with an extremely active group or man, because he activates the former Minister of the Environment […] who asks consultation questions, etc. in the parliament.

And this one politician, when sitting in our living room, he also honestly admitted that it might not be entirely reasonable. But we just really gotta go punch for punch, right […]. And it's like, nothing is moving until you've done something extraordinary […]. We really have to get up and make ourselves heard, and it's just so sad.

We tried to open the dialogue and bring in issues important to us, but that changed nothing. Every time it's about how we feel and how noise affects us, the answer is that ‘we follow the rules, we follow the law’ and so there is no progress.

Once, when a meeting was held in the [village] hall, we really fooled them […]. The meeting ended at half past nine, so we rented it from there until midnight. And when they said ‘now we are going to finish the meeting, because someone else has rented the hall’, X got up and said – ‘you shouldn’t worry, because it’s us who have rented it’.

6. Discussion

Although there has been a greater focus on participation in response to public resistance to wind farms, there is a tendency to overlook how participation can itself be imbued with existing power structures – and become the cause of contention. The empirical insights reveal shortcomings in terms of procedural justice within the public participation process for Danish WE planning. In light of its glorifying image, this raises questions as to whether this process really opens up spaces through which citizen voices can have an influence on the ‘outcome’ or whether engagement practices simply corroborate the status quo. These questions will now be elaborated using Gaventa’s spatial categories- invited, closed and claimed spaces, each of them describing a specific degree and pervasion of participation within and outside the public space.

6.1. Participation in the invited space of bureaucratic planning

Public participation in Danish WE planning falls mainly under the category of ‘invited space’ (Gaventa, Citation2006). When citizens are engaged in a consultation process, they are invited by the municipality, which has the possibility to set the agenda and to shape the scope of public engagement. Thus, the space for participation in WE planning can, in theory, be seen as a procedural, dialogue-seeking and legally just space, following standard procedures of the ‘good process’, claiming strong public involvement (LGD et al., Citation2009). As such, principal engagement methods involve written responses and possible public hearings that comply with normative qualities of participation.

In this study, however, responses from both citizens and planners indicate a limited scope for participation within the existing procedure. Although everyone has the formal opportunity of being heard, the framing of the debate does not provide a space for developing arguments and ideas about what is at stake. Not only does the wider public enter the formal planning process at a relatively late stage - in practice when a specific plan has already been proposed. The public debate is neither really about defining issues nor alternatives, even if the draft plan is in a preliminary form. While the timing of public engagement has previously been criticized due to a lack of sufficient information and preliminary project particularities that can be provided at early planning stages (Barnett et al., Citation2012), our findings indicate that this relative openness does not lead to a meaningful dialogue. Instead, the conversation appears to follow a common decide-announce-defend-approach (Wolsink, Citation2000; Bell et al., Citation2005; Walker & Baxter, Citation2017) of how pre-defined issues should be mitigated or resolved.

Of related importance is the expenditure of time and pro-activity required from the citizens. The prerequisite that it is the individual’s responsibility to become aware of upcoming projects entails the danger of being left behind from the start. Although the guidelines of ‘the good process’ describe how the pre-consultation or idea phase is meant to establish a debate, the limitation to 14 days makes it difficult for citizens to react on time – ironically making the debate phase much shorter compared to the consultation phase of at least 8 weeks. In addition, and in line with other studies (e.g. Walker & Baxter, Citation2017), spending a lot of time attending meetings and familiarizing with content leads to frustration over the process when input is not taken seriously.

Whilst fundamental debates are either made obsolete or fall short within the idea phase, they are inevitably shifted to the consultation phase of specific projects (Clausen & Nyborg, Citation2016) and play out anywhere else than in the formal consultation space, e.g. in the media or Facebook (Borch et al., Citation2020). At this stage, projects have usually reached an almost complete state and the content should primarily be concerned with the EIA - hence closing the space for issues that exceed mere technical-instrumental topics.

Thus, the invited space for participation does not take the shape of an open space, where different rationales are put in dialogue about future visions and alternative ways of organizing a sustainable society, but rather constitutes a technical-rational space (Lefebvre, Citation1991) constrained by the agendas of implementing agencies (Cornwall, Citation2004b). A challenge of the invited space relates to the fact that it is created as part of the system with an overall tendency of maintaining the status quo (Cornwall, Citation2004b). The adoption of an inviting strategy not only provides an opportunity of filtering information before, during and after the process, but also the chance of legitimizing the planning process and outcome. Lacking the means (and incentives) to genuinely address shared concerns, the promise of creating a space with room for new ideas and understandings therefore remains largely unrealized. The question that follows is whether a closed space may even disguise as an invited space for participation, and if so, what kind of systemic mechanisms emerge?

6.2. The tyranny of (invited) participation?

As Gaventa reminds us, closed spaces may seek to restore legitimacy by creating invited spaces (Gaventa, Citation2006). This is because spaces of participation are performed in dynamic relationship to one another and are ‘constantly opening and closing through struggles for legitimacy and resistance, co-option and transformation’ (Gaventa, Citation2006, p. 27). While local voices are encouraged, they may have little influence over the planning outcome. Such empty rituals (Arnstein, Citation1969) can, as argued by critics of tokenist or even ‘tyrannical’ displays of public participation, be seen in light of the need to mask a continued centralization in the name of decentralization (Cooke & Kothari, Citation2001, 7). While participation is conventionally represented as a more democratic alternative to top-down developments, the public space created may emerge out of technocratic concerns. Hence, ‘the will to empower’ (Cruikshank, Citation1999) can be seen to cover up the fact that spaces for participation embody the potential for a systemic exercise of power.

Our findings also show how the institutionalized public space is creatively utilizing participatory elements to align citizen’s input with the overall planning ambitions:

The level of complexity in the legal framework represents such a technique. Although legislative requirements and procedural rules may to a certain extent ensure a citizen right to information, complaints and hearings, they do not allow for an inclusive participation. Instead, they carry a language that is hierarchal, top down, one-sided and ultimately divisive. As argued by Williams (Citation2012), law can be seen as a highly privileged discourse that administers power and codified knowledge, which in turn shapes how we talk, think and relate to one another. The legal framework sets the boundaries of a ‘juridical space’ that has the ability to disempower silently all those perspectives going beyond the legal rules (Dahlberg, Citation2016). The legal discourse in the present analysis seems to reproduce the power of the bureaucratic system. It sets the frame for what is eligible to be brought into conversation: what is legal, what is a ‘legitimate’ hearing response, and what is ‘just a viewpoint’, which not only contributes to the legitimization of the project, but also manifests structural patterns. Democratic legitimacy is achieved as long as municipalities and developers comply with the legal framework. The recognition by residents that only those arguments are able to influence the process that are consistent with legal criteria of the EIA are reflective of the power of this discourse. Concerns over cranes and visual impacts upon churches may of course be genuine concerns, but they are also, due to their legally protected status, instrumentalized as powerful argumentative tools. Hence, as argued by Gaventa (Citation2006), power gained in one space, through new skills, capacity and experiences can be utilized to enter and influence other spaces. In addition, the strategy to involve own lawyers and other experts (e.g. on noise or biology) reproduces the technological regulative framework of the EIA.

The excluding character of the technical-scientific language is closely associated with this. The ‘testimonial’ format of expert panels does not enable citizens to develop and exchange ideas and solutions but causes them to take on the role of activists advocating their cause (Karpowitz & Mansbridge, Citation2006) , as exemplified in the EIA procedure. Based on pre-defined categories, the EIA determines what and how issues come to be debated and how ‘non-fitting’ issues are marginalized. Hence it does not capture the broader structures of everyday life such as family, work, social relations, place identity and mobility (Larsen et al., Citation2018; Smart et al., Citation2014).

Additionally, time emerges as a powerful strategy to close the public space for residents’ input. By using time as an excuse (short deadlines, cutting meetings, limited information etc.), it is possible to narrow down the space for public debate, thereby reducing disruptions of the overall plan. Following Lefebvre (Citation1991, p. 95), this does not only exemplify how space is a social and dynamic product, but also how the primacy of the economic and the political implies the supremacy over space and time.

Finally, a consequence of the developer practices to engage with private landowners is the intimidation of the public sphere. Sennett (Citation1976) uses the concept of ‘tyranny of intimacy’ to describe how public life loses its value of being public due to the degrading and crumbling boundary between the private and public. This is reflected in the ‘closure’ of the public space already in the idea phase, where the early and close dialogue between developers, the municipality and selected landowners gives them control over the communication during the planning process. As noticed by Jacquet (Citation2015, p. 241), this form of ‘private participation’ exacerbates the inequality between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’ present in communities. Later in the process, the responsibility of the EIA is devolved to developers, which contributes to the experience of the public space being sabotaged. This results in an amalgamation of environmental, economic and planning interests, which makes early participation a matter of economic management rather than empowerment and blurs the boundaries between material and procedural participation. Furthermore, the practice of developers to seek out, negotiate and even threaten citizens within the framework of their private sphere shows how social practices from institutionalized space can undermine formal engagement processes (Berry et al., Citation2019).

The fundamental question that follows is whether it is sensible to refer to participation at all, if it is obscured anyway? The recognition that public participation must be mediated within the framework of existing power networks questions the scope of individual agency. Referring to Barry and Ellis (Citation2011, p. 33), an actual reduction in substantive participative opportunities in RET is taking place to ‘streamline planning with the aim of enhancing investor confidence by speeding up the regulatory process and reducing the impact of dissent’. This tendency may, as noted by Cowell and Owens (Citation2006, p. 405), be particularly evident in the planning of large infrastructure projects, such as wind farms, where a closure of ‘crucial institutional spaces for challenges to the status quo’ is taking place. While participatory spaces could serve as arenas for rethinking and reshaping traditional modes of operating energy systems, the erosion of the democratic space may instead undermine longer-term social innovation and adaption to a common energy future (Barry & Ellis, Citation2011, p. 33). This lost potential becomes even more paradoxical when looking at the engagement performed outside the formal public space.

6.3. Potentials of self-organized participation

Various studies have noted the need to look more closely at the potentials of social conflicts in WE planning (Barry & Ellis, Citation2011; Cuppen, Citation2018). Instead of viewing conflicts as bumps on the road that should be de-politicized through legitimization techniques, they are regarded as new political spaces in which traditional modes of operating energy systems are challenged and reshaped (Cuppen, Citation2018, p. 30). This perspective aligns with an agonistic perspective (Mouffe, Citation1999), which considers democratic struggle as something inevitable and intrinsically good for the health of democracy (Barry & Ellis, Citation2011, 35).

In this study, such approaches address the relation between the formal public debate and the (in)formal popular mobilization outside the institutionalized policy arenas – i.e. claimed spaces (Gaventa, Citation2006). In the findings, this space emerges in different configurations. Overall, uncertainty arising from the experience of being marginalized and the pro-activeness required for participation creates a ‘space of uncertainty’ (Cupers & Miessen, Citation2002), which motivates residents to claim and create their own spaces for debate. Here, various tactics (external experts, letters, complaints, use of (social) media, and self-organized meetings) are mobilized in order to get a voice in the debate and to become the inviting party (i.e. inviting politicians and developers to their own agenda).

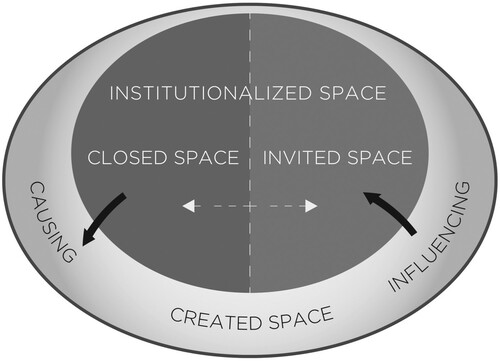

Such alternative publics are initiated in the private sphere where residents give vent to issues that are not debated within the formal public consultation space, and hint at the permeability between claimed, closed and invited space in WE planning (). As certain issues do not find a space to unfold in ‘the good process’ of WE participation techniques, they play out in informal self-organized arenas, which constitute a ‘counter-space’ (Lefebvre, Citation1991, p. 383) that rejects the agendas of planners, developers and the state and makes creative use of invited space. The initiatives of local residents to take over the physical premises of the formal space, initiate civic meetings or simply co-opt the system by using its own rules and options against itself demonstrates in this regard how invited spaces are ‘constantly in transformation as well as potential arenas for transformation’ (Cornwall, Citation2004b, p. 76).

Figure 3. The model shows the dynamic nature of space for participation in WE planning. The formal institutionalized space is in constant interaction between opening up (through invitation) and closing itself off from the influence of the citizens. The very pressure of the self-organized participation in the informal space contributes to this dynamic, while at the same time being constantly nurtured by the lack of real influence in the institutionalized space. Graphics: Oliver Abbey.

The paradox here is how such informal spaces take shape as a direct response to the entrenched relations of dependence, uncertainty and disfranchisement produced by the institutionalized public space. As an alternative to participation in the formal political space, it forms an ‘art of surveillance’ (DeCerteau, Citation1984), taking effect as a response to a ‘crisis of legitimation’ (Habermas, Citation1979) born out of the technocratic neglect of rationalities from the lifeworld and a lack of trust in the system. Simultaneously, they reflect local agency and provide opportunities for (local) democracy (Cuppen, Citation2018; Verloo, Citation2017). By mobilizing collective action and advocacy, the claimed and self-organized space seems to constitute a space for collective reflection in which participants can strive to reach shared visions and decisions about how to proceed (Berry et al., Citation2019; Cornwall, Citation2008). Such meanings may carry important answers and solutions to future energy challenges, but they require open spaces to unfold.

Therefore, we argue that we need to move away from focusinging almost purely on the juridical rationality, procedural correctness, and the legitimacy of decisions inside the invited institutionalized space and give more attention to the inspiration and learnings from the agency, political engagement and creativeness of the informal participation outside. From a theoretical perspective, this also represents an alternative to a controversial complete rejection of public participation (Cooke & Kothari, Citation2001). Since the problematization of inherent risks (tyranny and legitimization) is generally confirmed in this paper, it also presents an element of paralysis. Thus, it can also be argued that a further decoupling of citizens from energy governance is exactly the reason why it is necessary to upscale and reconfigure public spaces in WE planning.

7. Concluding remarks

Due to fixed procedures, early engagement and possibilities of involvement at both strategic and project levels, Danish WE planning has been considered as a good example from which other countries can learn. However, the insights from our research show that the public space provided for public participation reflects an invited space that is closed in its character. While the planning system cannot be blamed for not complying with legal requirements, the perceived shortcomings are grounded in how the participation requirements are implemented in practice. Even though there is certainly leeway for tweaking the practicalities to make it somewhat better, it fails to facilitate an active and influential public participation, which cannot really be achieved within the constrained frame of invited spaces. Trapped in systemic power structures that do not allow for empowerment, open dialogue and citizen influence, this space cannot achieve more than seeking to fulfill its instrumental purpose: legitimizing the development of infrastructure projects. Venturing beyond the legitimizing purposes of participation would therefore require a profound reconfiguration of a public space that encourages joint experiments, exploration and collaboration between established, oppositional and dialectical understandings of wind energy as part of a sustainable future.

Author contributions

The authors contributed, respectively, according to the order in which their names are listed: Laura Tolnov Clausen: Original Draft, Writing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Data collection and Analysis, Figures, Editing and Final Revisions. David Rudolph: Analysis, Legal procedures, Editing and Final Revisions. Sophie Nyborg: Data collection and Analysis, Methodology, Editing and Final revisions

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Laura Tolnov Clausen

Laura Tolnov Clausen is Associate Professor in the Department of Global Development and Planning at the University of Agder, Norway. She is an ethnologist and holds a PhD in environmental planning. Her research interests include social, political, economic and spatial dimensions of renewable energy transition with a specific focus on energy democracy, community participation, social movements, social learning, place-identity and governmentality.

David Rudolph

David Rudolph is a researcher in the Department of Wind Energy at the Technical University of Denmark. He is a geographer and his research seeks a critical geographical understanding of energy transitions. In particular, his current research activities focus on contestations over onshore and offshore renewables, people-place relations, community participation, governmentality and radical planning with a specific focus on social justice and rural areas.

Sophie Nyborg

Sophie Nyborg is a researcher in the Department of Wind Energy at the Technical University of Denmark and holds a PhD in sustainability transitions and science & technology studies. Her research is focused on responsible innovation, public engagement and controversies around techno-science, with particular interest in energy citizenship and -communities, social movements, user innovation as well as co-creation processes related to the green energy transition.

Notes

1 Consolidated Act no. 287/2018 on planning.

2 Statutory order on wind turbine planning (no. 1590/2014).

3 Wind2050.dk looked at drivers and barriers for social acceptance of WE in Denmark.

4 The SEP project was a collaboration between researchers and 8 municipalities in the southern region of Denmark to explore controversies in WE planning conducted in the Wind2050 project. Findings are reported in Nyborg et al. (Citation2015), Clausen and Nyborg (Citation2016) and Borch et al. (Citation2017).

5 The Danish church has the right of veto in matters of local building cases.

References

- Aitken, M. (2010). Why we still don’t understand the social aspects of wind power: A critique of key assumptions within the literature. Energy Policy, 38(4), 1834–1841. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.11.060

- Aitken, M., Haggett, C., & Rudolph, D. (2016). Practices and rationalities of community engagement with wind farms: Awareness raising, consultation, empowerment. Planning Theory & Practice, 17(4), 557–576. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2016.1218919

- Armeni, C., & Tegner Anker, H. (2019). Public participation and appeal rights in the decision-making on wind energy infrastructure: A comparative analysis of the Danish and English legal framework. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 63(5), 842–861. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1614436

- Arnstein, S. (1969). Ladder of participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Barnett, J., Burningham, K., Walker, G., & Cass, N. (2012). Imagined publics and engagement around renewable energy technologies in the UK. Public Understanding of Science, 21(1), 36–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662510365663

- Barry, J., & Ellis, G. (2011). Beyond consensus? Agonism, republicanism and a low carbon future. In P. Devine-Wright (Ed.), Renewable energy and the public. From NIMBY to participation (pp. 29–42). Earthscan.

- Batel, S. (2020). Research on the social acceptance of renewable energy technologies: Past, present and future. Energy Research & Social Science, 68, Article 101544, 1-5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101544

- Bell, D., Gray, T., & Haggett, C. (2005). The ‘social gap’ in wind farm siting decisions: Explanations and policy responses. Environmental Politics, 14(4), 460–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010500175833

- Berry, L. H., Koski, J., Verkuijl, C., Strambo, C., & Piggot, G. (2019). Making space: How public participation shapes environmental decision-making. SEI discussion brief. Stockholm Environment Institute. (pp. 1–8).

- Bidwell, D. (2016). Thinking through participation in renewable energy decisions. Nature Energy, 1(5), 1–4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2016.51

- Bora, A., & Hausendorf, H. (2006). Participatory science governance revisited: Normative expectations versus empirical evidence. Science and Public Policy, 33(7), 478–488. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3152/147154306781778740

- Borch, K., Munk, A., & Dahlgaard, V. (2020). Mapping wind-power controversies on social media: Facebook as a powerful mobilizer of local resistance. Energy Policy, 138, 111223–111223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111223

- Borch, K., Nyborg, S., Clausen, L. T., & Jørgensen, M. S. (2017). Wind2050 – a transdisciplinary research partnership about wind energy. In L. Holstenkamp, & J. Radtke (Eds.), Handbook on energy transition and participation (pp. 873–892). Springer.

- Cass, N. (2006). Participatory-deliberative engagement: A literature review. The School of Environment and Development, Manchester University.

- Chilvers, J., Damery, S., Evans, J., van den Horst, D., & Petts, J. (2005). Public engagement in energy mapping exercise. A desk-based report for the research councils UK energy research public dialogue project. Birmingham University.

- Chilvers, J., Pallett, H., & Hargreaves, T. (2018). Ecologies of participation in socio-technical change: The case of energy system transitions. Energy Research & Social Science, 42, 199–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.03.020

- Clausen, L. T. (2017). No personal motivation? Democracy, sustainability and the art of non-participation. Landscape Research, 42(4), 412–423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2016.1206870

- Clausen, L. T., & Nyborg, S. (2016). Borgeres og kommuners erfaringer med borgerdeltagelse i dansk vindmølleplanlægning. IFRO Udredning 2016/29. https://static-curis.ku.dk/portal/files/178695608/IFRO_Udredning_2016_29.pdf

- Clausen, L. T., & Rudolph, D. (2019). (Dis)embedding the wind – on people-climate reconciliation in Danish wind power planning. Journal of Transdisciplinary Environmental Studies, 17(1), 5–21. ISSN 1602-2297

- Clay, E., & Schaffer, B. (eds.). (1984). Room for manoeuvre: An exploration of public policy planning in agricultural and rural development. Heinemann.

- Cooke, B., & Kothari, U. (eds.). (2001). Participation: The new Tyranny? London: Zed Books.

- Cornwall, A. (2004a). Introduction: New democratic spaces? The politics and dynamics of institutionalized participation. IDS Bulletin, 35(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2004.tb00115.x

- Cornwall, A. (2004b). Spaces for transformation? Reflections on issues of power and difference in participation in development. In S. Hickey, & G. Mohan (Eds.), Participation. From tyranny to transformation? Exploring new approaches to participation in development (pp. 75–107). Zed Books.

- Cowell, R. (2007). Wind power and ‘the planning problem': the experience of Wales. Environmental Policy and Governance, 17(5), 291–306. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.464

- Cornwall, A. (2008). Unpacking ‘participation’: Models, meanings and practices. Community Development Journal, 43(3), 269–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsn010

- Cowell, R., & Owens, S. (2006). Governing space: Planning reform and the politics of sustainability. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 24(3), 403–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/c0416j

- Cruikshank, B. (1999). The will to empower. Democratic citizens and other subjects. Cornell University Press.

- Cupers, K., & Miessen, M. (2002). Spaces of uncertainty. Berlin revisited. Birkhaüser.

- Cuppen, E. (2018). The value of social conflicts. Critiquing invited participation in energy projects. Energy Research & Social Science, 38, 28–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.01.016

- Dahlberg, L. (2016). Spacing Law and politics: The constitution and representation of the juridical (space, materiality and the normative). Routledge.

- Danish Nature Agency. (2014b). Vindmøller – åbenhed, dialog og inddragelse. https://naturstyrelsen.dk/media/nst/8761577/nst_vindmoellefolder_maj2014_digital_ny.pdf

- DBA (Danish Business Authority]. (2015). Netværksbaseret planlægning med deltagelse af borgere og andre aktører. https://planinfo.erhvervsstyrelsen.dk/sites/default/files/media/publikation/netvaerksbaseret_planlaegning.pdf

- DEA [Danish Energy Agency]. (2009). Wind turbines in Denmark. Danish Ministry of Climate and Energy. http://www.ens.dk/sites/ens.dk/files/dokumenter/publikationer/downloads/wind_turbines_in_denmark.pdf

- DEA [Danish Energy Agency]. (2015). Energy policy toolkit on physical planning of wind power. Experiences from Denmark. Danish Ministry of Climate, Energy and Building. http://www.ens.dk/en/toolkits

- DeCerteau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. University of California Press.

- DE [Danish Energy]. (2019). VE Outlook 2019 Perspectives for renewable energy towards 2035. https://www.danskenergi.dk/sites/danskenergi.dk/files/media/dokumenter/2019-02/VE_Outlook_2019_0.pdf

- DEM [Danish Environmental Ministry]. (2013). Borgerinddragelse i vindmølleplanlægning. Statslig information om vindmøller. http://naturstyrelsen.dk/publikationer/2013/sep/videnblad-borgerinddragelse-i-vindmoelleplanlaegning/

- DNA [Danish Nature Agency]. (2014a). Lovgivningsmæssige begrænsninger for opstilling af vindmøller, en oversigt.. http://naturstyrelsen.dk/planlaegning/planlaegning-i-det-aabne-land/vindmoeller/vindmoellerejseholdet/faq/placeringshensyn/lovgivningsmaessige-begraensninger-for-opstilling-af vindmoeller-en-oversigt

- Ellis, G., Cowell, R., Warren, C., Strachan, P., Szarka, J., Hadwin, R., Miner, P., Wolsink, M., & Nadai, A. (2009). Wind power: Is there a “planning problem”? Expanding wind power: A problem of planning, or of perception? Planning Theory & Practice, 10(4), 521–547. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350903441555

- Fiorino, D. J. (1990). Citizen participation and environmental risk: A survey of institutional mechanisms. Science Technology & Human Values, 15(2), 226–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/016224399001500204

- Gaventa, J. (2006). Finding the spaces for change: A power analysis. IDS Bulletin, 37(6), 23–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2006.tb00320.x

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Sociology Press.

- Gross, C. (2007). Community perspectives of wind energy in Australia: The application of a justice and community fairness framework to increase social acceptance. Energy Policy, 35(5), 2727–2736. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2006.12.013

- Habermas, J. (1979). Communication and the evolution of society. Beacon Press.

- Haggett, C. (2011). Planning and persuasion: Public engagement in renewable energy decision-making. In P. Devine-Wright (Ed.), Renewable energy and the public. From NIMBY to participation (pp. 15–27). Earthscan.

- Hickey, S., & Mohan, G. (Eds.). (2004). Participation. From tyranny to transformation? Exploring new approaches to participation in development. Zed Books.

- Hildyard, N., Hedge, P., Wolvecamp, P., & Reddy, S. (2001). Pluralism, participation and power: Joint forest management in India. In B. Cook, & U. Kothari (Eds.), Participation: The new tyranny? (pp. 56–71). Zed Books.

- Hjerpe, M., Glaas, E., & Storbjörk, S. (2018). Scrutinizing virtual citizen involvement in planning: Ten applications of an online participatory tool. Politics and Governance, 6(3), 159–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v6i3.1481

- Jacquet, J. B. (2015). The rise of “private participation” in the planning of energy projects in the rural United States. Society & Natural Resources, 28(3), 231–245. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2014.945056

- Karpowitz, C., & Mansbridge, J. (2006). Disagreement and consensus: The need for dynamic updating in public deliberation. Journal of Public Deliberation, 1(1), 348–364. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.25

- Kirkegaard, J., & Nyborg, S. (2020, July 2-4). The Frankenstein story of Denmark's wind power market: The socio-material (re)birth of a social movement for and against wind power. The 36th EGOS Colloquium, Organizing for a Sustainable Future: Responsibility, Renewal & Resistance. University of Hamburg.

- Kaza, N. (2006). Tyranny of the median and costly consent: A reflection on the justification for participatory urban planning processes. Planning Theory, 5(3), 255–270. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095206068630

- Kersting. (2013). Online participation: From ‘invited’ to ‘invented’ spaces. International Journal of Electronic Governance, 6(4), 270–280. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEG.2013.060650

- Larsen, S. V., Hansen, A. M., & Nielsen, H. N. (2018). The role of EIA and weak assessments of social impacts in conflicts over implementation of renewable energy policies. Energy Policy, 115, 43–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.01.002

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Blackwell Publishing.

- Leibenath, M., Wirth, P., & Lintz, G. (2016). Just a talking shop? Informal participatory spatial planning for implementing state wind energy targets in Germany. Utilities Policy, 41(C), 206–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2016.02.008

- Local Government Denmark, Danish Wind Turbine Association, Danish Wind Industry Association & The Danish Society for Nature Conservation. (2009). Den gode proces. Hvordan fremmes lokal forankring og borgerinddragelse i forbindelse med vindmølleplanlægning? http://naturstyrelsen.dk/media/nst/Attachments/VindDengodeproces110609.pdf

- Mouffe, C. (1999). Deliberative democracy or agonistic pluralism? Social Research, 66(4), 745–758.

- Natarajan, L., Rydin, Y., & Lock, S. J. (2018). Navigating the participatory processes of renewable energy infrastructure regulation. Energy Policy, 114, 201–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.12.006

- Nyborg, S., Cronin, T., Kirkegaard, J. K., & Jørgensen, M. (2015). Åbenhed, dialog og inddragelse. Afrapportering af deltema 3 i SEP/WIND2050-miniprojekt DTU, Internal report.

- Ottinger, G., Hargrave, T. J., & Hopson, E. (2014). Procedural justice in wind facility siting: Recommendations for state-led siting processes. Energy Policy, 65, 662–669. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.09.066

- Rowe, G., & Frewer, L. (2005). A typology of public engagement mechanisms. Science, Technology and Human Values, 30(2), 251–290. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243904271724

- Sennett, R. (1976). The fall of public man. W.W. Norton.

- Seyfang, G., & Haxeltine, A. (2012). Growing grassroot innovations: Exploring the role of community-based initiatives in governing sustainable energy transitions. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 30(3), 381–400. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/c10222

- Simcock, N. (2016). Procedural justice and the implementation of community wind energy projects. A case study from South Yorkshire, UK. Land Use Policy, 59, 467–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.08.034

- Smart, D. E., Stojanovic, T. A., & Warren, C. R. (2014). Is EIA part of the wind power planning problem? Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 49, 13–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2014.05.004

- Szarka, J. (2006). Wind power, policy learning and paradigm change. Energy Policy, 34(17), 3041–3048. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2005.05.011

- Tegner Anker, H., & Jørgensen, M. L. (2015). Mapping of the legal framework for siting of wind turbines – Denmark (IFRO Report 239). Department of Food and Resource Economics. Copenhagen University.

- Toke, D., Breukers, S., & Wolsink, M. (2008). Wind power deployment outcomes: How can we account for the differences? Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 12(4), 1129–1147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2006.10.021

- Verloo, N. (2017). Learning from informality? Rethinking the mismatch between formal policy strategies and informal tactics of citizenship. Current Sociology, 65(2), 167–181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116657287

- Walker, C., & Baxter, J. (2017). Procedural justice in Canadian wind energy development: A comparison of community-based and technocratic siting processes. Energy Research & Social Science, 29, 160–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.016

- Williams, B. C. (2012). Communication and the public hearing process: A critiques of the land-use public hearing communication process. Admin 598 – management report. University of Victoria.

- Wolsink, M. (2000). Wind power and the NIMBY-myth: institutional capacity and the limited significance of public support. Renewable Energy, 21(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-1481(99)00130-5

- Wolsink, M. (2007). Planning of renewables schemes: Deliberative and fair decision-making on landscape issues instead of reproachful accusations of non-cooperation. Energy Policy, 35(5), 2692–2704. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2006.12.002

- Wynne, B. (2007). Public participation in science and technology: Performing and obscuring a political-conceptual category mistake. East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal, 1(1), 99–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1215/s12280-007-9004-7