ABSTRACT

There is a clear need for improving justice and sustainability in the implementation of renewable energy projects. Assessing energy justice in contexts with high cultural and ecological diversity as well as high levels of marginalisation, and a post-colonial history (of domination and resistance to it), requires taking into account the local contextual understandings of justice. Current literature, however, has been mostly developed under the evidence and concepts of Global North contexts, which tend to build in universal ideas of justice, often inappropriate for policy application in the Global South. To contribute to closing this gap, the paper qualitatively analyses the implementation of a large-scale photovoltaic project in Yucatan, Mexico, examining how neighbouring indigenous communities and other key actors perceive, experience and react to procedural and socio-environmental justice issues in the project's implementation. Results show that commonly-used concepts such as consent, participation and inclusion -as currently applied in the siting of renewable infrastructure- are now mostly perceived as legitimation of projects that align with the developer and governmental priorities. Emphasising self-determination over and above the aforementioned concepts is seen as a priority among affected communities for achieving a more socially just energy transition.

1. Introduction

Today, there is a broad consensus around the importance of transitioning to low carbon sustainable energy systems (United Nations, Citation2015). However, there is little agreement on how to do this equitably. Within this scenario, the Mexican government in 2016 set an ambitious commitment to increase clean energy generation from 21% to 35% by 2024 (EIA, Citation2016). To meet these objectives, the government introduced a Long-Term Auction (SLP) mechanism that offers stability and long-term contracts to investors interested in generating large-scale energy capacity (SENER, Citation2016). Within this auction model, the Yucatán peninsula was selected to host more than 20 large-scale wind and photovoltaic generation parks. If approved, these projects would occupy almost 14,000 hectares of land, of which 30% are ejido (communal) land (Sanchez et al., Citation2019). This deployment of megaprojects has favoured financial speculation and land privatisation, increasing land-use changes and damaging the local environment and livelihoods, causing community opposition to renewable energy infrastructure.

Literature critiquing the ethics and sustainability of projects like these has expanded (Avila-Calero, Citation2017; Bickerstaff et al., Citation2013; Dunlap, Citation2017), with the energy justice framework, in particular, questioning the fairness in decision-making process and distribution of benefits and risks (K. Jenkins et al., Citation2016). However, the bulk of this literature has developed from the experience and concepts of Global North countries, utilising universal ideas of justice – i.e. concepts and precepts pre-assume a common or unique conception of justice shared by everyone – which is often inappropriate for policy application in Global South (Broto et al., Citation2018). This paper, therefore, aims to contribute to closing this gap by analysing procedural injustice perceptions and experiences of indigenous communities in the context of the Yucatan Solar photovoltaic project.

The paper begins by reviewing key theoretical concepts within the energy justice framework, highlighting shortcomings in achieving procedural justice on the ground and discussing sovereignty-based ideas raised in grassroots indigenous movements. The Yucatan Solar photovoltaic study background is then presented before turning to discuss particularly contentious issues, such as who, when and how indigenous communities are included in the decision-making process. The discussion examines communities' perceptions, experiences and reactions to procedural and socio-environmental injustices before considering how these projects' implementation and the energy transition overall could be more just from a bottom-up perspective. It concludes by arguing that pluralistic approaches to energy justice are needed, emphasising a major inclusion of self-determination and energy sovereignty concepts in current energy justice frameworks if they are to have an impact beyond the North.

2. Literature review

2.1. Energy justice framework

In the past decade, the field of energy justice has grown rapidly (Pellegrini-Masini et al., Citation2020), expanding from a theoretical concept to a decision-making framework for policy evaluation and delivery (K. E. Jenkins, Stephens, et al., Citation2020). The energy justice framework seeks to apply principles of justice to energy policy, production and distribution. It highlights that energy policy requires a constant understanding of social justice applied to energy systems (McCauley et al., Citation2013).

Energy justice borrows ideas from the environmental justice movement, advocating for the inclusion of social justice and environmental sustainability in the implementation of development infrastructure (Schlosberg, Citation2009). It adopts three main justice concepts from the environmental movement literature – procedural, recognition and distributional justice. The distributional dimension is concerned with the inequity in the allocation of environmental risks and benefits throughout the energy system. The procedural dimension calls ‘for equitable procedures that engage all stakeholders in a non-discriminatory way’ (McCauley et al., Citation2013, p. 2). Finally, recognition justice draws attention to the various forms of political and cultural domination that result in discrimination of minority groups. It is defined as ‘the process of disrespect, insult and degradation that devalue some people and some places identities in comparison to others’ (Walker, Citation2009, p. 615).

Although the energy justice approach replicates the three groundings of environmental justice – distributional, recognition and procedural – they are rather different in their interpretation and understandings of justice. The most prominent energy justice frameworks (often associated with McCauley et al., Citation2013 and Sovacool & Dworkin, Citation2015) advocates for top-down policy-making, which is almost contrary to Schlosberg (Citation2009) account of environmental justice, which is especially sensitive to the grievances of indigenous communities. While the environmental justice agenda has been criticised for ‘its failure to have a pervasive impact beyond the grassroots level’ (K. Jenkins, Citation2018, p. 118), the energy justice framework has been accused of co-opting the word and meaning of ‘justice’ from the grassroots environmental movements to be used as an ‘abstract imperative’ by academic scholars (Galvin, Citation2020).

The idea that energy justice requires a more normative approach to make an impact beyond the grassroots level comes from the assumption that people have similar conceptions of justice and, therefore, a perfectly designed procedure would fit everyone. This way of thinking has led to the development of energy justice checklists and minimum standards for policymakers to consider when developing energy projects. However, as shown in the findings section, conceptions of justice are more pluralistic on the ground and vary widely according to the different socio-spatial and contextual conditions.

Although few political theorists support pluralistic notions of justice, Walzer (Citation1983) initiated a shift away from a single universal theory of justice in favour of comprehending the idea in its historical and cultural context; this shift has special significance in dealing with environmental justice (Schlosberg, Citation2009). While remaining tied to the concept of distribution, Walzer (Citation1983, p. 6) strives to develop a discourse of difference. He argues

that the principles of justice are themselves pluralistic in form; that different social goods ought to be distributed for different reasons, in accordance with different procedures, by different agents; and that all these differences derive from different understandings of the social goods themselves – the inevitable product of historical and cultural particularism.

In support of this pluralist view, Schlosberg (Citation2009) calls to recognise the real-world diversity of opinions reflected in the different social and environmental justice claims and embrace them. He believes that a critical pluralism

offers us a possible framework for thinking about the validity of plurality in social justice generally, and environmental and ecological justice specifically; with it, we can generally theorise while remaining open to the genuine and practical differences that exist in practice. (ch. 7, p. 4)

Some recent works on energy justice have also started to draw attention to the importance of considering a wider range of justice perpectives and moral theories to assess energy dilemmas (Wood & Roelich, Citation2020). However further empirical data is needed to support this arguments. Following this line of thought and based on grounded empirical evidence, I argue that a pluralist approach to justice conceptions should be embraced and promoted within the energy justice literature.

Energy justice approaches tend to show a strong focus on distributional justice theories, using Rawls's basic principles of justice, the principle of equal liberty and the difference principle as a starting point. Many papers emphasise the distribution of risks and supposed ‘benefits’, focusing on the asymmetries related to compensations for the use of land and resources and making suggestions on how redistribution of benefit would make an energy infrastructure implementation more just (Cowell et al., Citation2011; Hopkins, Citation2008; Sovacool et al., Citation2016; Warren et al., Citation2012). However, focusing on claims such as ‘distribution of benefits’ reinforces the assumption that people should, in the first place, accept a ‘development’, i.e. it accepts and normalises the idea that there should be an appropriation of natural resources. Thus, centring the debates on how the benefits of this appropriation should be distributed rather than challenging the idea of whether it is just (in a socio-environmental context) to accept the development in the first place, who should take that decision, and under what conditions. Putting these fundamental questions at the forefront is key if we seek more impactful energy justice understandings.

Although energy justice also considers procedural and recognition as part of its key ‘three-legged’ framework, there is much less literature on these two dimensions compared to the distributional component (K. E. Jenkins, Sovacool, et al., Citation2021). There has also been some engagement with these aspects of energy justice external to the scholars who focus on the three-pronged approach. For example, Simcock et al. (Citation2021) who focuses specifically on recognition justice. However, this has been mostly in relation to fuel poverty. In an attempt to contribute to closing this gap, this paper exposes some of the procedural injustices found in decision-making processes of renewable energy infrastructure implementation on the ground.

2.2. Procedural justice and sovereignty-based concepts

Literature on procedural justice within the energy justice framework states that a just energy infrastructure implementation entails the inclusion of stakeholders in decision-making in a non-discriminatory way and that participation, impartiality and full information disclosure by government and industry is required (Sovacool & Dworkin, Citation2015). More specifically, procedural justice normative approaches suggest that communities must be involved in deciding about projects that will affect them; they must be given fair and informed consent; and the environmental and social impact assessments must involve genuine community consultation (Sovacool & Dworkin, Citation2015). While several scholars agree with this definition (K. Jenkins et al., Citation2016; Sovacool et al., Citation2016), disputes remain regarding what a ‘just’ procedure entails and what its ‘ultimate purpose’ is, i.e. whether their purpose is to guarantee a more just outcome or it extends far beyond the recognition of individuals' equities (Simcock, Citation2016; Watson & Bulkeley, Citation2005). Pointing out the different perceptions of what a ‘just’ procedure entails becomes even more important with the mechanisms recently put into effect to diminish the socio-environmental impacts of development projects and improve participation at a local level, such as the Free, Prior and Informed Consultation (FPIC) and the Social and Environmental Impact Assessment (SEIA). According to some energy justice theories, applying these legal instruments improves justice on the procedural side, bringing forward a more ‘fair’ implementation of energy projects. However, in contexts with high levels of inequality and marginalisation, these instruments have often proved unsuccessful and are often viewed by community members and grassroots organisations as performative mechanisms intended to legitimise the implementation of development projects (Múuch' Xíinbal, Citation2018).

Recognising and understanding the pluralistic conceptions of justice according to different contexts is key. Previous case studies in Sierra Leone, India and Mozambique have demonstrated that applying universal western ideas of justice and making assumptions concerning ‘progress’ in energy developments might be risky for poorer developing countries (Broto et al., Citation2018; Munro et al., Citation2017; Yenneti & Day, Citation2015). Some Latin American scholars have also been wary of this western vision of modernisation through major developments – essentially associated with economic growth, appropriation of natural resources, and aimed at stimulating the western lifestyle – and have pointed them out as unsustainable and socially unfair (see Bustelo, Citation1998; Cardoso & Faletto, Citation1996; Gudynas, Citation2009).

Similarly, they have criticised the energy system for being oriented for the profit of a few major companies and have suggested a response that emerges from the bottom-up, including energy sovereignty and self-determination ideas: ‘when we think of energy sovereignty, we believe that the production, extraction, distribution and consumption of energy is controlled by the peoples’ (Gutierrez, Citation2018, p. 13). Other scholars have also advocated for energy sovereignty as the right of individuals, communities and peoples to make their own decisions regarding the generation, distribution and consumption of energy so that these are appropriate to their ecological, social, economic and cultural circumstances, as long as they do not negatively affect third parties (Cotarelo et al., Citation2014). The concept of self-determination varies among indigenous peoples, scholars and nations. The most prevalent interpretation of self-determination holds that peoples that share a similar political and cultural organisation have the right to govern themselves and their territory. Mexico's current Constitution recognises the right of indigenous peoples and communities to self-determination to decide their internal forms of coexistence and social, economic, political and cultural organisation.

In a similar vein, scholars have suggested concepts of energy sovereignty and decentralising energy governance for a more democratic and just energy infrastructure decision-making (see Broto et al., Citation2018; Cowell, Citation2017). Broto et al. (Citation2018) argue for a focus on delivering energy as an emancipatory project and recommend self-determination to become a core concept in energy justice theories (Broto et al., Citation2018). Similarly, Cowell analyses how shifting territorialisation of government and control over energy infrastructure can disrupt energy systems and help us to extend our understandings of energy transitions (Citation2017).

In this sense, it is critical to analyse, from a local perspective, the conditions in which renewable energy infrastructure implementations are taking place in contexts where current transition models may be clashing with ideas of sovereignty and therefore face strong opposition. Examining energy justice challenges in Yucatan Mexico – a region with a huge potential for renewable energy implementations but also strong opposition to currently proposed wind and photovoltaic parks – provides insights into the challenges of achieving procedural justice on the ground but also will shed some light on alternative routes for a more sustainable energy transition and future.

3. Methodology

3.1. The case study

The research reported in this paper was undertaken as part of a larger PhD project that analysed the implementation of two photovoltaic and two large-scale wind energy projects in Yucatan, Mexico. For this paper, I will only focus on the analysis of The Yucatan Solar photovoltaic park to explore the possible outcomes when local opinions and environment are not seriously considered and private mercantilist logics dominate the implementation of renewable energy infrastructures. It is important to mention that findings from this case were consistent across my other sites in the research.

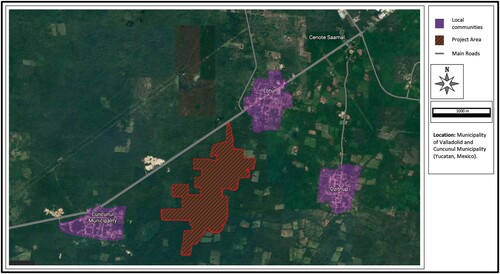

The ‘Yucatán Solar’ photovoltaic project is a large-scale development proposed in the municipality of Valladolid, Yucatan, Mexico. The project was promoted by Lightening PV Park, a subsidiary of the Chinese Jinko Solar, to place approximately 313,140 photovoltaic modules in an area with forest cover. For the execution of the project, it was required to clear 206.51 hectares, which represents 80.85% of the total surface of the project area, the impact was deemed adverse due to the area being considered a jungle that has been maintained for the last 50 years (EIA, Citation2016). At present, the land clearing has already been carried out. In , it can be seen a satellite view of the before and after of the intervention of the company.

Figure 1. Satellite view of the before and after of the intervention of the Jinko Solar company for the implementation of the ‘Yucatán Solar’ photovoltaic project. Source. Images taken from Google Earth and edited by the author.

Despite being a project with a strong environmental negative impact, the project obtained authorisation from the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT), an organisation in charge of evaluating the project's feasibility. This approval raised indignation among several community members and organisations who join together to file a legal demand to stop the project. At the moment of writing this paper, the project hold a final suspension order.

3.2. Methods and analysis

To explore key actors' perceptions, experiences and responses to the implementation process, a qualitative and ethnographically inspired research design was developed. The first phase of fieldwork was undertaken from January to March 2019, followed by a 4-month second phase from September to December 2019. Three main methods were utilised. First, analysis was conducted on relevant documents such as the SEIA of the project, news, webpages of local organisations, government secretariats and developers.

Second, in-depth participant observation was undertaken, including a visit to the proposed project location, and multiples visits to the communities nearby which provided an understanding of the local environment, culture, forms of life and overall context. I also attended four public meetings with different key actors such as government representatives, local academics, activists and grassroots organisations; two press conferences organised by community members; a meeting with representatives of the Jinko Solar company and critical voices of the project; among several other small community gatherings.

Third, in-depth semi-structured interviews in the study site and other multi-actor meeting spaces were carried out. Twenty-five people were interviewed, including 15 members of the communities mentioned above, 5 government representatives, 2 Mayan activists and 3 local academics. A combination of purposive sampling (particularly with government representatives and local academics) and snowballing was used to select and recruit the interviewees.

It is important to mention that the views presented in this study are not representative of the whole community. Many of the people who were introduced to the researcher through snowballing were critical of the project, which gave me access to networks of opponents, with limited access to supporters. However, the data collected evidenced the procedural injustices perceived and experienced in the project implementation process. After translating and transcribing data from interviews and research diary, the data were thematically analysed using NViVo software and a deductive approach by one coder. The energy justice framework's three main concepts – procedural, distributional and recognition – served as a basis for guiding initial data structuring, leaving the door open for inductive coding to identify other types of injustices, themes and alternatives for more just energy transitions. In this paper, I focus on procedural-related themes and their socio-environmental impacts. Claims on participation, inclusion, decision-making power, agency and information disclosure and exchange were highlighted and sub-categorised under the procedural justice dimension. As the concepts above are closely related and found significant parallels, the coding was done through an iterative process where emerging themes and consulting literature to refine the relationship among them was followed. Analysing people's concerns about the project siting, plus their suggestions on more just procedures and alternatives, helped me better understand what drives the opposition to the projects and what people identified as unjust. To protect respondents' anonymity, the names of the interviewees cited in this study have been changed. For accurate rendition, most of the interviews were audio-recorded with prior consent from participants. Before the commencement of fieldwork, the research obtained University of Sheffield's Ethics committee approval under the application form number 023852.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Procedural injustices on the ground

In this section, I show the three main procedural injustices found in the field. By procedural injustices can be understood the perceived and experienced injustices pointed out by grassroots and local community members regarding decision-making, participation and information exchange procedures in the implementation of the Yucatan Solar project. In the first subsection, I demonstrate that the inclusion of communities in key decision-making is left to governments and developers that arbitrarily decide who is affected and, therefore, who is included. In the second subsection, I argue that current participation in the project implementation is not meaningful since communities are included only in the last part of the process when everything is decided, and the complexities of the context are not taken into account. Finally, in the third subsection, it is evidenced that there is no impartial information disclosure from the government and developer side since informational and consultation meetings mostly focus on the benefits offered to the communities, but they omit or minimise the negative impacts of the projects. This section also highlights socio-environmental injustices derived from the above procedural injustices.

An important thing to recognise is that indigenous communities' views and perceptions are far from being homogeneous. Contrary to what some scholars suggest, communities are composed of people who do not necessarily share the same ideas, cosmovision, interests and values. Sometimes is ignored or evaded the fact that, over time, indigenous peoples have become increasingly socially and politically fragmented due to class, religion, partisan differences, etc. (Torres-Mazuera et al., Citation2018). For this reason, I argue that energy justice frameworks must move away from universal top-down conceptions of justice and advocate for pluralist bottom-up justice ideas if they are to have an impact beyond the North.

4.1.1. Exclusion of affected communities in key decision-making

The procedural justice dimension in the energy justice framework states that governments and developers must include communities in deciding about the projects that will affect them. What inclusion means, however, has been highly contested at a local level. One of the main perceived and experienced injustices raised during interviews was who decides what communities are included or excluded in the decision-making process and under what criteria. Currently, the determination of the ‘area of influence’ – that is to say, the area where the nearby communities will be potentially impacted – is decided through the Social Impact Assessment (SIA). While the Secretary of Energy provides certain general administrative provisions that suggest how to determine these areas of influence, there is a wide range of freedom for developers and consultancy firms to play with:

The law allows the promoter or entrepreneur of the energy project to define the areas of impact. Therefore, the company has all the freedom to define them [the areas of impact]… The regulations give you some elements or socio-demographic and economic variables related to closeness... but developers can choose whether they can go through all the variables or some. (Interview with an ex-representative of the Ministry of Energy in the area of Social Impact Assessments, 2019)

In the Yucatan Solar photovoltaic project, this ambiguity in the regulations meant the exclusion of Dzitnup, one of the three communities located close to the project. The developer excluded this community under the basis of not having a ‘direct’ connection to the project: ‘the area of direct influence, in fact, was determined by the connection, through the highway 180 Valladolid-Mérida, of two indigenous communities: Cuncunul, head of the municipality of the same name; and Ebtún, a town attached to the municipality of Valladolid’ (SIA, Citation2016, p. 226). This decision meant not only taking away Dzitnup community right to an FPIC but also to any compensation derived from the potential impacts of the project. In , the reader can see the distance between the three communities and the project, showing a similar closeness between all of them.

Figure 2. Distance between the three communities surrounding the project – Ebtún, Cuncunul and Dzitnup – and the project area. Approximately 1–2 km from the project to the three communities according to Google Maps. Source. Image taken from Google Earth and edited by the author.

For some Dzitnup community members, the fact that there was not a paved way connection to the project does not mean that they would not be affected.

We, like the other two communities, also depend a lot on beekeeping, we also suffer very high temperatures throughout the year, with the deforestation of so much vegetation, we will be as impacted as the other communities. (Martin, local resident of Dzitnup)

The discontent of some members of Dzitnup – together with people from other localities such as Valladolid – was reflected in an ‘amparo’ (claim for protection) lawsuit against the project to be halted under the basis of violations to their right to a safe environment and their right to an FPIC. In April 2019, the project was permanently suspended due to this lawsuit, and although there have been claims from the developers and the government to be resumed, at the time of writing this paper, the project is still stopped.

From the evidence above, it is apparent that a top-down approach to procedural energy justice can be ineffective for ensuring a more just implementation. The problem with this top-down approach is that it takes the goodwill of governments and developers for granted. It assumes that by offering the developer a code of ethics with best practices on how to carry out a fairer implementation of projects, they will have the political will to do it in this way (Galvin, Citation2020).

In a meeting held on March 2019 in Ebtún, while government representatives discussed with the residents the reasons why the project was halted, the government kept emphasising that the signatories of the lawsuit were members of other ‘non-affected communities’, such as Dzitnup and Valladolid. For the Mayan community members signatories of the lawsuit, however, as well as for many other grassroots and defenders of the Mayan territory, the fact that the project is not ‘in their backyard’ or within the official limit of their locality, does not mean that it will not affect them. For them, the defence of a ‘territory’ on a broader sense of the word is claimed: ‘The territory is that place where our ancestors come from, where we carry out our activities of daily life, not necessarily where the law limits it’ (Ian, local Mayan resident).

The point here is that deciding who will be affected (or not) should not be left to policymakers and developers to decide. The fact that local communities do not have the say whether they will be affected or not by a project already constitutes a violation of their collective indigenous right to self-determination. And, therefore, it constitutes an injustice. Grassroots and community members that oppose these projects do not do it based on an individual concern. They conceive themselves as a whole community, and as such, if some of them or their lands are affected, everyone is affected, regardless of the fact that the project is not literally right around their house. These collective injustices are hardly ever mentioned in the energy justice framework as their theoretical basis is strongly focused on Global North western individualist justices frames, most notably that of moral philosopher John Rawls (Galvin, Citation2020). In Schlosberg and Carruthers (Citation2010, p. 17) words, ‘unlike traditional liberal political thought, contemporary movements do not limit themselves to understanding injustice as faced only by individuals; justice for communities is often at the forefront of their interests and protests’.

If the energy justice framework aspires to have an impact beyond the North, it is key that it recognises the broader conceptions of justice. It must also pay more attention to the collective mobilisations' views, such as those who demand their right to self-determination to be respected so that the people decide who is affected, who should be consulted, and under what conceptions of justice a transition to renewable energy must be carried out.

4.1.2. (Un)Meaningful participation

Besides the contentious process of partial inclusion of communities in key decision-making, another significant procedural injustice perceived and experienced on the field is the type of participation of people in the project implementation. Within the current large-scale private model for energy transition, the participation of people to decide over the project is often limited to a yes or no decision in the so-called FPIC. For many community members, being consulted once all key decisions have been made in terms of location, size of the project, type of technology and areas of influence of the project does not amount to meaningful participation:

They [developers] arrive when the project and everything else is done, the staff who come already know what the deals are … the government is already included too, so what outcome do you expect from that? The company comes ready to start its business. (Marcelino, local resident Ebtún)

This way of community participation is mostly seen by grassroots movements as a facade, an attempt to legitimise a project's imposition while pretending that communities have been allowed to exercise their right to self-determination and informed consent.

The consultations are made when the projects are already defined, when the contracts have been made when everything is clear between them, then a simulation is made, people go and vote, and that is it. That is not a consultation; that is deception. (Mario, local resident Valladolid)

The procedural justice approach in the energy justice framework suggests that spaces for meaningful participation of people should be provided to ensure a more just transition, making an emphasis on the FPIC instrument to obtain consent from communities before the siting of energy projects (Sovacool & Dworkin, Citation2015). A focus on this institutionalised instrument, however, does not ensure justice by itself. Being implemented by the government (with the help and information from developers) it relies on the goodwill and interpretations of those who carry it out. Although FPIC has become a dominant symbol in discussions of human and indigenous rights, and even in neoliberal policies, this mechanism has been highly contested by grassroots movements. This is because it can be seen either as ‘a mere procedure, very typical of neoliberal governance or as a substantive element of the right to self-determination of indigenous peoples’ (Llanes Salazar, Citation2020, p. 172). Most indigenous organisations and their allies argue that, in the context of Mexico, it has been used as a mere consultation procedure, not satisfying the demands for justice as the self-determination of the peoples:

The problem is that even if the consultation were made free, prior and in good faith, it still wouldn't be an exercise of self-determination since it would not serve for the people to determine what they want or what they are going to be in the future, it only serves for the community to decide over the initiative of an external third party. (Gabriel, member of a regionally active non for profit organisation)

Overall, focusing on institutionalised, procedural precepts is not enough to bring forward just energy transitions. As Rodríguez-Garavito (Citation2011, p. 273) argues, ‘an emphasis on procedure postpones or mitigates, but does not eliminate substantive disagreements, nor contrasting visions of participation and empowerment defended by the governance crowd and the indigenous rights movement’. On the contrary, in many cases, procedural instruments such as the FPIC have proved to increase conflicts over land and resources (Dunlap, Citation2018; Rodríguez-Garavito, Citation2011) due to the ‘abysmal difference between the contexts in which FPIC is regulated and the contexts in which consultations actually occur’ (Rodríguez-Garavito, Citation2011, p. 291). Similarly, contexts where scholars theorise about the meaning of justice are quite different from the context where people struggle for justice, leading to limited perceptions and ungrounded policies. More attention should be paid to grassroots opinions of what justice actually means, and what just inclusion, participation and transition could look like.

Similarly, a meaningful participation should engage local complexities so that power dynamics do not incline towards one side only – provoking an unjust procedure. However, under top-down participatory spaces, such as the FPIC and similar ‘public informational meetings’ organised by the government or developers themselves, the local complexities are hardly or not at all taken into account. In the implementation of the Yucatan Solar project, for example, historical marginalisation and discrimination due to colonial and post-colonial heritage have led to many people not having the confidence to express what they think in public events. In a public meeting in Ebtún, for instance, after a few calls from the government representatives for people to collect signatures to support the project, a Mayan woman decided to stand up and said:

The truth here is that there are very few people who know how to read or write, and although it might seem that they [people] are understanding what they are being told, sometimes they do not understand it. Then, there are other people who, although they want to speak out because they know that this project can affect them, do not dare to say it because sometimes they are ashamed or do not know how to express themselves. (Flor, Mayan woman at an informative public meeting)

Claims such as people not participating from being ashamed or scared of being singled out as ‘opponents of progress’ or even threatened for opposing the project were very common in the field. These fears were not far from the reality since a couple of the signatories of the lawsuit against the project declared publicly to be threatened or harassed. A Mayan activist and teacher in the Dzitnup community expressed in a press conference being intimidated by representatives of the company visiting her in her workplace in an attempt to convince her to withdraw from the lawsuit. Likewise, another signatory of the legal demand was visited at his place by a stranger and was left a note asking him to withdraw from the legal demand. These forms of intimidation discourage the population from having greater participation and involvement, especially when it comes to speaking out against projects that are perceived with great political support.

Being threatened for opposing to development of megaprojects in Mexico is not rare. However, in the context of Yucatan, the arrival of this new model of large-scale ‘clean energy’ energy infrastructure represents an even more serious threat due to its nature of being settled across large areas of territory. Pablo, a Mayan activist in opposition to these developments, expressed his worry by making an analogy with historic colonial impositions

I have always say that these [companies] from the renewable energies and its projects are like when the Bible came to us, it had a message of hope, but if you do not accept it they will kill you, so today these clean energies do not understand if they are clean because it will clean us all or they are clean because it will do justice to all. (Pablo, Mayan activist threatened for opposing the project)

Although procedural normative suggestions for fairer implementation of projects such as consultation exercises have served as a space for convergence between different actors, systematic and dominant power dynamics have not allowed them to serve as a space for meaningful participation, where communities can exert agency over what occurs in their territories. In this line, procedural and energy justice frameworks would benefit from moving away from top-down procedural rationalities where power relations are ignored, and assumptions of parties participating in equal terms in the consultations process are made. Collective claims of cultural identity, self-determination, and control over territories often invoked by indigenous peoples present themselves as an opportunity to focus on more impactful understandings of energy justice.

4.1.3. Socio-environmental injustices and partial information disclosure

The overall context of climate change, together with the significant wind and solar potential in the Yucatan peninsula, has been the official rationale to support solar and wind projects in the region. It is estimated that during the 2018–2032 period, a total of 32 projects, 21 wind farms and 11 photovoltaic parks will be installed in the Yucatan Peninsular Region (Sanchez et al., Citation2019). The cumulative effects on the environment and land-use changes risk not only the territory's sustainability but also the cultural survival of the peoples that depend on it (Sanchez et al., Citation2019). Additionally, the fact that the local population does not have a say in the location and other key characteristics of the project has caused decisions to be made based on purely technical and economic criteria, putting aside the environmental sustainability that renewable projects often presume. In the Yucatán Solar photovoltaic park, the location of the project meant the devastation of approximately 1260 arboreal specimens and 5786 shrubs per hectare (SEMARNAT, Citation2017), causing a severe impact on the native flora and fauna. Pablo, a Mayan activist who opposes this project, highlights the contradictions of this model from his particular perspective:

Right now, what they [developers and governments] are concerned about is generating electricity. But they are doing it by deforesting and throwing away the jungle. [So] Between now and 2030, 2050, it is very likely that there will be electrical energy. What we are not sure of is whether there will be oxygen left because they have already screwed all the trees. Do they have any idea how this is going to play out? Damn good, there is [electric] current, but what do we breathe? That is the question. (Pablo, Mayan activist)

This statement gives a vivid impression of the paradox of what is promoted as an environmental ‘externality’ or a ‘trade-off’ in the race to move away from fossil fuels. However, it goes beyond that. Grassroots and Mayan activists make a call to go to the roots of the problem. Is tearing down the jungle worth it in the name of mitigating climate change? And if so, at the expense of what and whom? Tearing down trees and filling the planet earth with turbines and solar panels might not get us anywhere near a sustainable society if we do not question the use of the energy generated and its infinite demand. Not being critical of infinite growth ideals promoted by capitalist-liberalist logics at the expense of the environment might not save human beings from the climate change crisis. When approaching renewable energies, it is many times ignored the part of them that is not renewable at all (Dunlap, Citation2019). The high amount of minerals extracted for the creation of solar and wind infrastructure is hardly recognised. There is also no clear say of what will happen with the amount of non-recyclable waste generated at the end of their life span. Should the renewable energy transition follows the same extractivist private-led model seen in fossil fuels, it will not only reproduce the socio-environmental injustices of the high carbon industry but also will create new and worsen existing ones (Dunlap, Citation2019; Shapiro & McNeish, Citation2021; Temper et al., Citation2020). A recent study demonstrates that low-carbon projects are almost as conflictive as fossil fuels, disproportionately impacting vulnerable groups such as indigenous communities. While ‘Indigenous peoples constitute 3% of the global population, they are impacted in no less than 50% (n=322) of cases examined’ (Temper et al., Citation2020, p. 14). A similar percentage is representative of both fossil fuels and renewable projects. Socio-environmental injustices derived from renewable energy projects and those impacted should be put at the forefront of energy justice discussions.

While there are clear socio-environmental impacts and injustices derived from renewable projects, host communities are hardly informed of these. The incomplete disclosure of information for these projects was a recurrent issue highlighted by interviewees. Most respondents mentioned that the information provided during informational meetings and consultations with developers and the government was biased since they would predominantly focus on the benefits and reject or minimise local impacts:

If they come and tell you that they are going to put you in a project, where they will give you work, they will pay you well, it will not affect you at all, it will generate clean energy, and they will even lower your electricity payment. Well, who says no? However, they are taking advantage of the need and the lack of knowledge of the people because that information is not real, and with that, they manipulate people. (Omar, local resident Cuncunul)

When developers are confronted with uncomfortable questions about the social, health and environmental impacts, these are frequently avoided, blatantly disregarded or half answered (Dunlap, Citation2018). In a small impromptu meeting between members of the organisation in defence of the Mayan territory Múuch' Xíinbal, academic allies of the organisation, and representatives of Jinko Solar Company and SEIA consultants hired by the company, there was a heated debate on the impacts of the project in the local area. While the representative of the company claimed to ‘be open and available to dialogue and to provide information to the community’, an academic repeatedly asked about the impacts of the project on beekeeping. The representative responded that they provided information to the community on how ‘the panels’ would not affect the bees. To which the academic replied: ‘the problem is not if the panels affect bees, the problem is if deforestation affects beekeeping’. While the representatives interrupted each other trying to answer the question, one of them concluded that there was no ‘significant honey production in the polygon’, avoiding the main question again. Similarly, questions regarding the amount and type of forest in the polygon before the deforestation were asked. Several of them were answered with ‘I do not have the exact figure’ and ‘since we are not environmental specialists … we could ask a specialist, in this case, to talk with you to give you the precise details of the concern you have’. Affirming that they are not ‘environmental specialist’ but still being in charge of the SEIA development did not comfort the sceptical attendees. With disappointment for the mostly incomplete or unanswered questions, one of the attendees argued excitedly,

It would be important that you, who are somehow representing this company and come to dialogue, at least had the information. In other words, I find it incredible that in addition to the ‘200 hectares approximately ’ and others ‘approximate’, that you do not know how much it is. Now, you say that the process [of deforestation] does not affect beekeeping. That is something very ignorant to say; one thing is that there might not be so many beekeepers in the area, [but] wild bees are affected, even a primary school child knows that. Why do you always seek to deceive people? (Nayely, member of the grassroots organisation 'Múuch' Xíinbal')

The social and impact evaluations also presented significant methodological deficiencies and bias information, merely based on technocratic knowledge and mercantilist logics. Besides, since the developer itself hires consulting firms to carry out the socio-environmental impact studies without independent verification processes, this is often seen as a conflict of interest (Sanchez et al., Citation2019). In the Yucatan Solar project's Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), for example, many impacts are classified as adverse but ‘mitigable’. By mitigable, it is usually understood that they try to ‘affect as little as possible’ as long as it does not interfere with the interests of the project. In the so-called Prevention and Control Measures of the Flora and Fauna Conservation Subprogram of the EIA, it is declared as a measure of conservation that ‘In the areas of temporary affectation and where it is feasible to ensure the safe circulation of [project] vehicles, the larger trees will be kept … This activity will also take place on the edges of the access road’ (EIA, Citation2016, ch. 6, p. 12). For them, the deforestation of more than 200 hectares can be mitigated by promising to leave some trees untouched. Similarly, they place a high emphasis on restoration measures, which involves rescuing some species that ‘specialists’ consider important:

The rescue of complete specimens of plant species included in NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 will be carried out …it will discriminate those specimens that, due to their size, had a low probability of survival after transplantation. In general, specimens of more than one meter in height will not be rescued. (EIA, Citation2016, ch.6, p.13)

Developers also affirmed that they would comply with the mitigation measures by paying the government for the damage caused, ‘with the understanding that the [government] entity (CONAFOR) responsible for the application of the contributed resources will channel the [economic] resources to restore forest ecosystems in the same area of Project influence’ (EIA, Citation2016, ch. 6, p. 16). None of these assumptions acknowledges or refers to whether the community values the environment in any other way. At no point does the EIA mention that certain mitigation measures will be taken ‘according to what the community considers important’. This approach assumes that all people value the environment in the same way (mainly as economic good) and that, therefore, any economic compensation will do to make the project more just.

In addition to the power relations in the multi-actors' meetings, the discussions held in these are deliberately directed towards compensation measures, instead of having a more in-depth discussion about the project itself, whether or not it should be implemented. Although there are many people who accept projects out of economic need, the reality in the field is that there are many people who value the environment and nature in diverse ways. Several interviewees asserted that the loss of biodiversity due to these megaprojects not only threatens the environment, but also the survival of ancient traditions and their culture. For example, traditional Mayan medicine is still practised in the region. It is based on species that are mainly found in the jungle in a good state of conservation -such as that dismantled by the project – according to Yatziri, a Mayan woman from the Ebtún community. Furthermore, a signature of the Yucatan Solar project's lawsuit affirmed during interviews that the Xok K'iin (also known as Mayan cabañuelas) – a traditional method of observing the jungle ecosystem through which they predict the climate and meteorological phenomena that will occur during the year – is still a method of ‘utmost importance’ for some Mayan farmers since it determines the Mayan agricultural calendar and, therefore, it becomes a way to guarantee the obtaining of food. Similarly, for another activist and defender of the Mayan territory, ‘the Xox K'iin – cabañuelas in the Mayan language – is a permanent reading of the life and a reunion with our roots’ (Caamal 2018, an active member of the ‘Xok k'iin’ collective). For these people, the fact that the developer will pay a sum for the deforested area, either to the government or to the community, will not compensate for the threat to their traditional practices and cultural survival. As some members of the grassroots Mayan organisation 'Múuch' Xíinbal' in defence of the territory and other community members explain:

‘I am not defending our territory on a whim, I am defending a way of life, and I believe that all human beings and all cultures have the right to defend a way of life’ (Alfredo, member of a Mayan grassroots organisation). ‘If we don't defend this territory, they [energy companies] will end our culture’. (Maria, Dzitnup local resident)

This echoes the Schlosberg and Carruthers (Citation2010, p. 13) arguments in regard to ‘how indigenous environmental justice claims are embedded in broader struggles to preserve identity, community, and traditional ways of life’. As seen in the quotes above, for Mayan people, opposing the projects is not just a matter of not allowing energy infrastructure to be built near them. What these communities have at stake is something more important than just some parcels of land; they are fighting for the survival of their identity as a community. The environmental conceptions of justice for indigenous people are beyond individual and distributional concerns. In Schlosberg and Carruthers's words,

The environmental justice struggles of indigenous peoples reveal a broad, integrated, and pluralistic discourse of justice –one that can incorporate a range of demands for equity, recognition, participation, and other capabilities into a concern for the basic functioning of nature, culture, and communities. (p. 12)

As it can be seen above, applying universal top-down policies has tipped the balance of decision-making power towards government and developers, causing procedural and socio-environmental injustices, preventing communities from exercising their right to self-determination.

The above evidence also demonstrates that indigenous people see their territory as more than an economic asset. Although the perspectives and values within communities are certainly not homogenous, many local people value their surroundings and territory in different ways, and therefore diverse perspectives should be recognised and respected. In this vein, I argue that procedural – and energy justice frameworks overall – would benefit from moving away from a universal, distributional and individual-focused conception of justice. It is of utmost importance that struggling voices on the ground are heard and taken into account, as they can certainly provide more down-to-earth conceptions and opinions on what is valuable, and therefore, how a transition to renewable energy could be more just and environmentally sustainably focused.

4.2. Self-determination as a route for energy justice

Community members showed little or no confidence that the project implementation would become more just and sustainable under the current private large-scale renewable energy model, and suggested a bottom-up perspective to be taken into account:

I think it [renewable energy] is not worth it from the perspective that is being handled, perhaps if it were done from the perspective of the indigenous communities, it would change, and it would really be environmentally friendly. You may ask, How? Well, with small projects or on the roof of the houses that do not harm me, where it is already an urbanised area and it is already deforested. (Jose, Mayan local resident)

Respondents also pinpointed the limitations of this model in regards to control over their territories and decision-making power, with calls for greater self-determination and autonomy in the deployment of renewable technologies:

I believe that communities should make their own public policy and be recognised within the framework of their autonomy and self-determination. They [external agents and government] should not make policies for the communities. It is what we have suffered for 500 years, making the same public policy for all when we are not all the same. […] Here, the problem is that the law is made by some for everyone when we are not all the same. That needs to be understood, and if that diversity is recognised, I think we will live better. (Pablo, Mayan activist)

As seen in the quotes above, indigenous communities and grassroots have critical insights to bring into the energy justice and development conversation. Despite this, their ideas and knowledge have been highly disregarded. Communities should have the possibility to develop policies from their own background that encompass their complexity so that solutions are adaptable to the communities' context (McHugh, Citation2017; Tsosie, Citation2012). As Ramon states:

I think it [my vision] coincides a lot with the Zapatista approach that has to do with autonomy and self-determination. What does this mean? The possibility of laws that allow the [Mayan] people to make our own laws, respecting our historical, cultural and identity peculiarities. That is what we would have to build in the first place. The rest will follow by itself. (Ramon, member of Mayan grassroots organisation)

These echo the ideas of Broto et al. (Citation2018) and Cowell (Citation2017) on energy sovereignty and decentralising energy governance for a more democratic and just energy infrastructure decision-making. Broto et al., for example, concluded that ‘energy sovereignty thought complements energy justice thinking by emphasizing the need to recognize the autonomy and self-determination of people in framing energy decisions that affect them, including the frames applied to evaluate them’ (Citation2018, p. 648). As seen in the quotes above, communities can bring many insights in imagining a more just and sustainable transition. It is important to truly recognise these voices and knowledge. As Eloy eloquently argues:

For a just energy transition to take place, it is necessary for it to happen from the perspective of the community, from the perspective of us as people, since this transition is supposed to be for the benefit of the people. So, we are the ones who must decide, how we want it, where we want it, and what we want for our community. (Eloy, Mayan local resident)

Some people might think that the self-determination principle raises challenges for infrastructural systems like energy because claims of self-determination introduce new potential veto points within systems that some actors would like to see extending ‘smoothly’ across space. However, principles of autonomy and energy sovereignty are an opportunity for pushing forward alternative forms of energy projects (Stefanelli et al., Citation2019). In Mexico, conflict over large-scale solar and wind developments put pressure on the government to halt the auction system, leading to its current suspension. This has presented an opportunity to consider community-based renewable energy (at least in theory) since the ‘National Development Plan 2019–24’ stated that the new energy policy would promote sustainable development through the incorporation of populations and communities into the production of energy with renewable sources. This opens a scenario in which the Mayan peoples living in those territories could take an active role in the transition, gaining control of the energy production within their territories and pushing for a more sustainable and just transition.

5. Conclusion

The Yucatan Solar photovoltaic project clearly demonstrates the challenges of achieving a just implementation of renewable energy infrastructure due to the limitations of realising normative top-down approaches to procedural justice on the ground. The study shows that the imposition of profit-led models produces and reproduces injustices, inequalities, and power dynamics that risk the cultural and socio-environmental local context. Addressing the energy transitions requires the meaningful engagement of local communities, consultation and complete disclosure of key information for informed decision-making (Huesca-Perez et al., Citation2016; Sovacool & Dworkin, Citation2015). However, institutionalised procedural mechanisms such as the FPIC and the SEIA have proved ineffective to ensuring a just renewable implementation and transition overall.

Models of transition that grant greater decision-making power to communities and that respect and promote their rights to autonomy and self-determination are needed. Although current energy justice frameworks are useful at helping identify the injustices perceived and experienced on the ground, it lacks an emphasis on bottom-up and recognition approaches that leads to serious socio-environmental injustices in the ground. Existing energy justice frameworks need to be more sensitive to the grievances of indigenous communities, and shift from top-down normative approaches to more bottom-up policy-making to address systematic energy and socio-environmental injustices. Overall, the energy justice literature would benefit from recognising and embracing pluralist notions of justice as reflected in the claims and struggles from grassroots movements.

It is increasingly evident that indigenous energy sovereignty is a critical element for improving justice in the energy transition (Cotarelo et al., Citation2014; Schelly et al., Citation2020). Prioritising self-determination over consent, participation and inclusion in indigenous contexts can be a way for achieving a more socially just and sustainable energy transition (Gutierrez, Citation2018). Therefore, integrating energy sovereignty concepts into the energy justice framework will not only make the energy transition more just (by contemplating wider understandings of justice and framing energy decisions according to what communities believe is best for them), but also, in the process, transitions might get more effective through reducing the opposition and promoting alternative decentralised ways to renewable energy infrastructure.

Acknowledgments

The author is very grateful to the local communities and organisations who kindly agreed to participate in this study. A special thanks to the Assembly of Defenders of the Mayan Territory, Múuch 'Xíinbal, the Articulation Yucatán collective, and the Yansa organisation for their kind support during fieldwork. She is also thankful to the Special Issue organisers, two anonymous reviewers, and her supervisors Dr Matt Watson and Dr Daniel Hammett for their valuable and constructive feedback. Finally, she wishes to extend a special thanks to J. Francisco Daunas T. for his hearty support during the writing of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sandra Jazmin Barragan-Contreras

Sandra Jazmin Barragan-Contreras is a PhD candidate in Human Geography at the University of Sheffield, United Kingdom. Her ongoing thesis research investigates energy justice in Mexico, and the ways in which different actors, policies and practices can intersect to form a more socially just sustainable energy transition. She holds a MSc in Environmental Change and International Development from the University of Sheffield. Along her research, Sandra has participated in sustainability projects with rural and urban communities in Brazil, Nepal and Peru.

References

- Avila-Calero, S. (2017). Contesting energy transitions: Wind power and conflicts in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Journal of Political Ecology, 24(1), 992–1012. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2458/v24i1.20979

- Bickerstaff, K., Walker, G. P., & Bulkeley, H. (2013). Energy justice in a changing climate: Social equity and low-carbon energy. Zed Books.

- Broto, V. C., Baptista, I., Kirshner, J., Smith, S., & Alves, S. N. (2018). Energy justice and sustainability transitions in Mozambique. Applied Energy, 228, 645–655. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.06.057

- Bustelo, P. (1998). Teorias contemporaneas del desarrollo economico. Editorial Síntesis.

- Cardoso, F. H., & Faletto, E. (1996). Dependencia y desarrollo en america latina: ensayo de interpretacion sociologica. Siglo xxi.

- Cotarelo, P., Llistar, D., Pérez, A., & Berdié, L. (2014). Definiendo la soberanía energética. El Ecologista, 81, 51.

- Cowell, R. (2017). Decentralising energy governance? Wales, devolution and the politics of energy infrastructure decision-making. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(7), 1242–1263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X16629443

- Cowell, R., Bristow, G., & Munday, M. (2011). Acceptance, acceptability and environmental justice: The role of community benefits in wind energy development. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 54(4), 539–557. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2010.521047

- Dunlap, A. (2017). Wind energy: Toward a ‘sustainable violence’ in Oaxaca: in Mexico's wind farms, a tense relationship between extractivism, counterinsurgency, and the green economy takes root. NACLA Report on the Americas, 49(4), 483–488. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2017.1409378

- Dunlap, A. (2018). ‘A bureaucratic trap’: Free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) and wind energy development in Juchitan, Mexico. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 29(4), 88–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2017.1334219

- Dunlap, A. (2019). Renewing destruction: Wind energy development, conflict and resistance in a Latin American context. Rowman & Littlefield International.

- EIA, R. (2016). Evalución de impacto ambiental parque fotovoltaico yucatan solar (1st ed., Vol. 1; SEMARNAT, Ed.). SEMARNAT.

- Galvin, R. (2020). ‘Let justice roll down like waters’: Reconnecting energy justice to its roots in the civil rights movement. Energy Research & Social Science, 62, Article 101385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101385

- Gudynas, E. (2009). Diez tesis urgentes sobre el nuevo extractivismo. Extractivismo, politica y sociedad, 187.

- Gutierrez, R. F. (2018). Soberania energetica propuestas y debates desde el campo popular (1st ed.). Ediciones del Jinete Insomne.

- Hopkins, R. (2008). The transition handbook. Green Books Totnes.

- Huesca-Perez, M. E., Sheinbaum-Pardo, C., & Koppel, J. (2016). Social implications of siting wind energy in a disadvantaged region – The case of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Mexico. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 58, 952–965. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.310

- Jenkins, K. (2018). Setting energy justice apart from the crowd: Lessons from environmental and climate justice. Energy Research & Social Science, 39, 117–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.11.015

- Jenkins, K., McCauley, D., Heffron, R., Stephan, H., & Rehner, R. (2016). Energy justice: A conceptual review. Energy Research & Social Science, 11, 174–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.10.004

- Jenkins, K. E., Sovacool, B. K., Mouter, N., Hacking, N., Burns, M. K., & McCauley, D. (2021). The methodologies, geographies, and technologies of energy justice: A systematic and comprehensive review. Environmental Research Letters, 16(4), 043009. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abd78c

- Jenkins, K. E., Stephens, J. C., Reames, T. G., & Hernández, D. (2020). Towards impactful energy justice research: Transforming the power of academic engagement. Energy Research & Social Science, 67, Article 101510. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101510

- Llanes Salazar, R. (2020). La consulta previa como símbolo dominante: significados contradictorios en los derechos de los pueblos indígenas en México. Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies, 15(2), 170–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17442222.2020.1748934

- McCauley, D. A., Heffron, R. J., Stephan, H., & Jenkins, K. (2013). Advancing energy justice: The triumvirate of tenets. International Energy Law Review, 32(3), 107–110. http://hdl.handle.net/1893/18349

- McHugh, N. A. (2017). Epistemic communities and institutions. In ByIan James Kidd, José José, & Gaile Pohlhaus (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of epistemic injustice (pp. 270–278). Routledge.

- Munro, P., van der Horst, G., & Healy, S. (2017). Energy justice for all? Rethinking sustainable development goal 7 through struggles over traditional energy practices in Sierra Leone. Energy Policy, 105, 635–641. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.01.038

- Múuch' Xíinbal. (2018). Asamblea maya múuch' xíinbal. Retrieved January 15, 2019, from https://asambleamaya.wixsite.com/muuchxiinbal/blog/author/M.-Jazm%C3%ADn-Sanchez-Arceo%2C-y-M.-Ivet-Reyes-Maturano%2C-de-Articulacion-Yucatan?fbclid=IwAR0PXfnDNB77CKjcWKcv0VtakSXZxZAcX0L7Mn6eAcyoWcg9Uu29gReAM0

- Pellegrini-Masini, G., Pirni, A., & Maran, S. (2020). Energy justice revisited: A critical review on the philosophical and political origins of equality. Energy Research & Social Science, 59, Article 101310. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101310

- Rodríguez-Garavito, C. (2011). Ethnicity. gov: Global governance, indigenous peoples, and the right to prior consultation in social minefields. Indiana Journal of global Legal studies, 18(1), 263–305.

- Sanchez, J., Reyes, I., Patino, R., Munguia, A., & Deniau, Y. (2019). Expansion de proyectos de energia renovable de gran escala en la peninsula de Yucatan. Consejo Civil Mexicano para la Silvicultura Sostenible, 1(1), 1–29.

- Schelly, C., Bessette, D., Brosemer, K., Gagnon, V., Arola, K. L., Fiss, A., Pearce, J. M., & Halvorsen, K. E. (2020). Energy policy for energy sovereignty: Can policy tools enhance energy sovereignty? Solar Energy, 205, 109–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2020.05.056

- Schlosberg, D. (2009). Defining environmental justice: Theories, movements, and nature. Oxford University Press.

- Schlosberg, D., & Carruthers, D. (2010). Indigenous struggles, environmental justice, and community capabilities. Global Environmental Politics, 10(4), 12–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00029

- SEMARNAT. (2017). Resolutivo de la manifestación de impacto ambiental. Retrieved June 5, 2021, from https://apps1.semarnat.gob.mx:8443/dgiraDocs/documentos/yuc/resolutivos/2016/31YU2016E0036.pdf

- SENER. (2016). Prospectiva de energias renovables 2016 a 2030 secretaria de energia, Mexico. Retrieved February 3, 2019, from https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/177622/Prospectiva-de-Energ-as-Renovables-2016-2030.pdf

- Shapiro, J., & McNeish, J. A. (2021). Our extractive age: Expressions of violence and resistance. Taylor & Francis.

- SIA (2016). Evalución de impacto social parque fotovoltaico yucatan solar. Retrieved June 3, 2021, from https://articulacionyucatan.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/02-yucatc3a1n-solar.pdf

- Simcock, N. (2016). Procedural justice and the implementation of community wind energy projects: A case study from South Yorkshire, UK. Land Use Policy, 59, 467–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.08.034

- Simcock, N., Frankowski, J., & Bouzarovski, S. (2021). Rendered invisible: Institutional misrecognition and the reproduction of energy poverty. Geoforum, 124, 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.05.005

- Sovacool, B. K., & Dworkin, M. H. (2015). Energy justice: Conceptual insights and practical applications. Applied Energy, 142, 435–444. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.01.002

- Sovacool, B. K., Heffron, R. J., McCauley, D., & Goldthau, A. (2016). Energy decisions reframed as justice and ethical concerns. Nature Energy, 1(5), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2016.24

- Stefanelli, R. D., Walker, C., Kornelsen, D., Lewis, D., Martin, D. H., Masuda, J., Richmond, C. A. M., Root, E., Neufeld, H. T., & Castleden, H. (2019). Renewable energy and energy autonomy: How Indigenous peoples in Canada are shaping an energy future. Environmental Reviews, 27(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2018-0024

- Temper, L., Avila, S., Del Bene, D., Gobby, J., Kosoy, N., Le Billon, P., Martinez-Alier, J., Perkins, P., Roy, B., Scheidel, A., & Walter, M. (2020). Movements shaping climate futures: A systematic mapping of protests against fossil fuel and low-carbon energy projects. Environmental Research Letters, 15(12), Article 123004. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abc197

- Torres-Mazuera, G., Mendiburu, J. F., & Godoy, C. G. (2018). Informe sobre la jurisdicción agraria y los derechos humanos de los pueblos indígenas y campesinos en México. Fundación para el Debido Proceso.

- Tsosie, R. (2012). Indigenous peoples and epistemic injustice: Science, ethics, and human rights. Washington Law Review, 87, 1133. https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol87/iss4/5

- United Nations. (2015). Sustainable Development Goals: 17 Goals to transform our world. Retrieved November 15, 2021, from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/.

- Walker, G. (2009). Beyond distribution and proximity: Exploring the multiple spatialities of environmental justice. Antipode, 41(4), 614–636. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2009.00691.x

- Walzer, M. (1983). Spheres of justice. Basil Blackwell.

- Warren, C., Cowell, R., Ellis, G., Strachan, P. A., & Szarka, J.. (2012). Wind power: Towards a sustainable energy future?. In Joseph Szarka, Richard Cowell, Geraint Ellis, Peter A. Strachan, & Charles Warren (Eds.), Learning from wind power (pp. 1–14). Springer.

- Watson, M., & Bulkeley, H. (2005). Just waste? Municipal waste management and the politics of environmental justice. Local Environment, 10(4), 411–426. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830500160966

- Wood, N., & Roelich, K. (2020). Substantiating energy justice: Creating a space to understand energy dilemmas. Sustainability, 12(5), 1917. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051917

- Yenneti, K., & Day, R. (2015). Procedural (in) justice in the implementation of solar energy: The case of Charanaka solar park, Gujarat, India. Energy Policy, 86, 664–673. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2015.08.019