ABSTRACT

In contrast to its successful decarbonisation of the electricity system, Sweden has failed to achieve momentum in its attempts to decarbonise transport. This paper examines the reasons for this failure by investigating the discourse around investment in Swedish transport infrastructure. Our analysis focusses specifically on discussions about establishing high-speed rail (HSR) spanning 25 years. We identify three central discursive themes: the issue of financing, the role of the state in socio-technical change, and fatalism. We then trace these themes to storylines within the HSR discourse that each tell a story about good transport governance, informed by a specific interpretation of Swedish modernisation. Four storylines converge in a ‘‘deflationary’’ discourse coalition, characterised by ideas of sound finance and depoliticised governance, that reinforces material dependencies on existing transport infrastructure. A competing, ‘‘Weberian’’ discourse coalition is united through a contrasting storyline that instead highlights state capacity as evidenced by Swedish modernisation.

Introduction

In sharp contrast to its successful decarbonisation of the systems for electricity and heating, Sweden has struggled for decades to achieve progress in decarbonising the transport system. Emissions reductions from energy efficiency improvements and biofuel use have largely been cancelled out by transport increases (SEPA, Citation2020). Thus, transport bills since the 1990s reveal a remarkably consistent pattern of calls to reduce persistently flat or even rising CO2 emissions (Swedish Government, Citation1996, Citation2005, Citation2012, Citation2016a). Meanwhile, climate targets have been cautiously shifted into the future. The original vision of a fossil fuel free transport system by 2020, established in 2005 (Swedish Government, Citation2005), has become a vision for 2050 (Swedish Government, Citation2012, Citation2016a). Even so, the current target of a 70 per cent emissions reduction by 2030 remains highly ambitious in light of the slow progress made and is not deemed to be on track to be achieved (SEPA, Citation2019).

Following a sustained period of growth in the 1980s, the Swedish railway system is seen as a key component of a transport sector transition towards sustainability. However, there is unanimous agreement that the current railway infrastructure, the core of which remains essentially unchanged since its establishment 150 years ago, is approaching its physical capacity limit. Proponents of the merits of rail transport have therefore promoted the vision of a new high-speed railway (HSR). Yet, despite sustained pressure since the early 1990s, five state inquiries between 1995 and 2009, and significant support in Parliament for most of the period, it has remained purely a vision. Successive governments have stated their intent to develop HSR but then struggled to fund such a costly undertaking in the face of internal and parliamentary opposition.

Building HSR is unquestionably a significant infrastructural challenge that requires commitment of resources over time. It is hardly, however, unprecedented, as HSR developments in, for example, Spain, Italy and France reveal. Indeed, as proponents of HSR in Sweden are eager to point out, the original railway establishment in the 1860s is testament to the state’s capacity for transformative infrastructure projects. Instead, we will argue that the main struggle for proponents of HSR is not against material challenges per se, but how these material challenges are understood through a specific, hegemonic discourse.

Our aim here, therefore, is twofold. First, our descriptive purpose is to show how transport planning in Sweden, and HSR planning specifically, is constituted through a discourse that sets out specific roles for the state in transport planning. Second, our more analytical purpose is to explain how different positions in the HSR discourse coalesce through storylines about Swedish modernisation, and how such storylines constrain actors’ room for manoeuvre in the political arena.

Following a brief theoretical-methodological framing, we will proceed to draw up the main lines of the Swedish HSR discourse from the 1990s to the present day. We highlight three key themes: the issue of financing, the role of the state in socio-technical change, and fatalism. We then relate these themes to storylines about Swedish modernisation and good governance and discuss how they form competing discourse coalitions with radically different outlooks on material dependencies in transport governance.

Theory/method

Dependencies through discourse

We define discourse as an ontological struggle concerning the framing of a specific phenomenon within a certain sphere of society, in this case the struggle within the sphere of Swedish infrastructure investment planning between different ways of understanding the societal value of HSR. We adopt a Foucauldian view of discourse, under which discourse is understood as the way social and material phenomena reflect particular perspectives or views of the world (Cousins & Hussain, Citation1984; Van Assche et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Dobbin’s (Citation1994) study of national systems of industrial policy is a good example of how ideas and interpretations of history can be shown to become institutionalised, forming path-dependencies within modern systems of governance.

We further find Hajer’s account of ‘storylines’ (Citation1995) useful to understand how complex realities and historical developments are made sense of through discourse. To Hajer, a storyline offers a necessarily simplifying narrative of complex cause-and-effect relationships and historical processes, thereby serving to structure past events and create models for future action. Such storylines may be patchworks that include elements from several distinct discourses. They can thus facilitate alignment between actors with highly differing viewpoints and priorities. Such alignment may create ‘discourse coalitions’, i.e. groupings of different actors that share a common political goal (Hajer, Citation1995, p. 63).

This paper is part of a special issue on material dependencies and their role in sustainability transitions. ‘Material dependency’ is understood here as the relationship between the existing transport infrastructure and the transport planning system as filtered through discourse. In line with the framing of the special issue, we posit that this relationship tends to be rendered invisible within the planning systems themselves, since, as Van Assche et al. (Citation2017a) argue, a certain form of knowledge is given priority over others: ‘Certain types of knowledge, certain ways of constituting and understanding [the world] lead to specific ways of managing or governing it’ (p.245). As Dobbin argues, an ability to observe planning systems from a distance is hard to acquire, since ‘from within, it is difficult to see any cultural frames as such’ (ibid., p.13). It requires separating the knowledge claims from the reality of which they speak, and to re-embed formally objective, material-technical statements about what is possible and impossible into the social context in which they originate (e.g. Buschmann & Oels, Citation2019). We find the concept of storyline conducive for the purpose of analysing how certain forms of knowledge are given priority within a discourse.

Our methodological approach necessarily puts the spotlight on the discourse itself and allows us neither to conclude anything about actors’ interests nor to draw causal links between the actors’ societal position and their influence upon the discourse. Nevertheless, actor groups are important to highlight, as the method still allows us to identify coalitions of actors and their position within the discourse. In this sense, it is still possible for us to analyse the power that resides in establishing hegemonic knowledge within a discourse, albeit only indirectly and without explicit attributions of agency to particular actor groups.

Our main argument is that the way transport discourse interprets certain historic events and processes as being key to Swedish modernisation creates storylines. These storylines also unite actors in discourse coalitions and define their perception of their room for political manoeuvre. As such, the paper is anchored primarily in political science literature that describes the dramatic changes to the Swedish welfare state after World War II, combined with key studies of the establishment of the modern Swedish transport planning system. To this literature, it adds an understanding of how visions of transport decarbonisation are defined and constrained by discourse, and more specifically a hegemonic discourse about the role of the state in transport planning.

Empirical material and analysis

We approached the Swedish HSR discourse through Swedish print media and official government and agency literature, gathering the following items dating from 1995 onwards, 1995 being the year the first state inquiry into HSR was published:

around 2000 opinion and news pieces

12 national plans for transport infrastructure and associated reports published by the Swedish Transport Administration (STA) or its predecessorsFootnote1

15 transport-oriented governmental bills and communications relevant to HSR.

After a quick reading of the 2000 media texts, we identified the main patterns of meaning in the discourse, along with around 300 print media texts that most substantively represented these patterns. The three hundred texts were then analysed through a close reading, in which we inductively identified three themes that pervade the discourse: the issue of financing, the role of the state in socio-technical change, and fatalism in technocratic governance. The official documents were then analysed in relation to the themes identified in the reading of the print media.

The discursive themes could be described as orientation points around which most statements in the HSR discourse gather. That is to say, most discussion about HSR concerns in some way the possibility or impossibility of funding HSR, the issue of what role the state could and should have in transforming the transport system, or the reliance on socio-economic models for understanding the future development of transport and the degree to which the government and state agencies can alter those paths. The themes are not mutually exclusive, rather they are our own analytical constructs, and there are significant overlaps between them. The same discursive statement might well be referred to all three of the themes. We have separated them analytically in order to structure the text and clarify our main observations. From the three hundred texts, we have cited examples that represent the three themes, and we have chosen to use exact quotes sparsely, where lines of reasoning cannot be summarised without losing some of the meaning.

Thirty years of Swedish HSR discourse

From the early 1990s, following a decade of sustained growth in passenger and goods transport by rail, municipalities, regional authorities and industry groups in Sweden have lobbied hard in favour of establishing HSR. The idea has been to connect Stockholm with Gothenburg and with the Öresund region, using HSR lines to improve both passenger transit and exports, the latter by reducing pressure on existing lines (Eriksson, Citation2002; Johansson, Citation1993). With political attention turned increasingly to global warming in the 2000s, as well as to regional disparities within Sweden, HSR has taken on great symbolic significance for its proponents as a measure of the government’s ability and resolve to act on its promises, reducing both inequity and emissions. While emphases have shifted somewhat over time and between different groups, it has been easy to align the disparate arguments for HSR under the banner of sustainable growth.

Between 1994 and 2006, Sweden was ruled by Social Democrat minority governments. In 2006 there was a historic shift to a conservative-liberal government that won re-election in 2010, to then be replaced by a Social Democrat and Green minority government in 2014. The latter was re-elected, with support from two right-of-centre parties, in 2018. The issue of HSR has gone through several shifts in this time, often being regarded with scepticism by the largest party in government but pushed by smaller governmental parties. It gained traction after being left out of the Social Democrat transport bill of 2005 and has since been lobbied for intensely both inside and outside of Parliament. For many years the Conservative Party, the largest in that government, was the only parliamentary party opposed to it (Andreasson, Citation2005; Asp, Citation2008a; Boman Karlsson, Citation2008; Centerpartiet, Citation2007, Citation2008; Ekelund, Citation2007; Elmsäter-Svärd & Lagerlöf, Citation2018a; Eriksson & Svensson-Smith, Citation2007, Citation2010; Eriksson & Wetterstrand, Citation2009; Fritzon et al., Citation2016; Fritzon, Citation2017; Hulthén et al., Citation2013; Micko & Knape, Citation2018; Sunesson, Citation1998; Svensson-Smith, Citation2008a; Trouvé, Citation2017; Westerberg et al., Citation2018; “Centern spårar … ”, Citation2007; “Miljarder till … ”, Citation2008; “Ökat tryck … ”, Citation2008”; “S och Mp vill … ”, Citation2008).

From the 2010 election, HSR has been promoted as part of parties’ election platforms, first with the Social Democrats and Greens (Sahlin et al., Citation2010) and then with the Conservative Party, making a strategic conversion in 2014, including HSR as a key component in their vision of ‘Building Sweden’ (Lönnaeus, Citation2016). Losing power in 2014, however, most right-of-centre parties also lost interest in HSR, and the Social Democrat-Green government has since tried unsuccessfully to achieve broad parliamentary support for HSR (Lönnaeus, Citation2016; Magnusson, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Tribo & Glad, Citation2016). Committed to an agreement with two other parliamentary parties, the government in 2020 commissioned the STA to plan for HSR under the very restrictive budgetary cap of SEK 205 billion.

Through all the shifts in parliamentary support, the main patterns of the HSR discourse have remained remarkably stable. In the following, we will highlight three discursive themes: The issue of financing, the role of the state in socio-technical change, and fatalism in technocratic governance.

The issue of financing

The first theme can be traced to the principle, agreed upon across the political spectrum since the end of the 1980s, that each sector of the transport system should be able to finance itself (Hultén, Citation2012; Swedish Government, Citation2001, Citation2008a). When HSR was first being promoted in the early 1990s, it was thus opposed by the state Railway Administration and the Social Democrat government on the grounds that it would be ‘uneconomic’ (Lönnroth, Citation1995). The HSR discourse therefore came to centre on the economic sustainability of channelling huge funds into a railway project and, more specifically, where the state is supposed to find the source of funding. In the Social Democrat minority government’s infrastructure bill of 1996, the government notes the important benefits associated with HSR but determines that such a project cannot be financed at present (Swedish Government, Citation1996). This is repeated in subsequent bills (Swedish Government, Citation2001, Citation2008a) until the conservative-liberal government, in 2012, takes a step towards making the HSR project concrete by announcing – as an election promise – that HSR planning should move ahead in stages, at a speed dictated by what the economy allows (Swedish Government, Citation2012). The same respect for economic speed limits has been shown by Social Democrat-Green governments since 2014 (Swedish Government, Citation2016a).

Thus, there is little discernible difference between representatives of parliamentary parties in their adherence to strict budgetary limits, especially when it comes to those occupying the Ministry of Finance (Andreasson, Citation2005; Björklund, Citation2008; Ferm, Citation2010; Forssmed & Halef, Citation2018; Hinderson, Citation2010; Karlberg, Citation2010; Lönnaeus, Citation2016; Torstensson, Citation2010; Tribo & Glad, Citation2016; “Bestämmer Borg … ”, Citation2008; “Blir Ostlänken … ”, Citation2008; “En budget … ”, Citation2010; “Försena inte … ”, Citation2010; “Ökat tryck … ”, Citation2008). The finance minister of the Social Democrats deployed the same rhetoric of fiscal prudence in 2016, when she backed away from a commitment to HSR due to a lack of funds (Lönnaeus, Citation2016; Tribo & Glad, Citation2016), as did the Conservative Party’s finance minister in 2010, when he cautioned against ‘living beyond our means’ (Borg, Citation2010). It is logical, therefore, that all visions of HSR, such as those delivered by the Social Democrats in government (Augustsson, Citation2018; Fransson & Klarberg, Citation2018; “Fortfarande oklart … ”, Citation2018), and the Christian Democrat Party in 2018 (Forssmed & Halef, Citation2018), are explicitly made reliant on stable majorities in Parliament. Such majorities have heretofore proved elusive – unsurprisingly, perhaps, since any resistance can be justified in terms of economic trade-offs. It is easy for opposition politicians to adopt the voice of reason by identifying better ways to spend the money, as when the leader of the Conservative Party argues, against the Social Democrat plan for HSR in 2018, that we should prioritise maintenance work on the existing railway rather than ‘entertaining the idea of high-speed rail that will be finished in 2040’ (Magnusson, Citation2018; see also Augustsson, Citation2018; Fransson & Klarberg, Citation2018; Magnusson, Citation2019b; “Fortfarande oklart … ”, Citation2018).

The understanding of strict budgetary limits can only be understood on the assumption – rarely made explicit within the discourse – that money supply is inelastic, since only on that premise does it follow that money being channelled into building HSR will necessarily have to be offset by reduced investment elsewhere in the economy. The implicit acknowledgement of this assumption explains why the issue of loan financing for HSR – while acknowledged as a possibility in transport bills – is typically treated by the government as highly temporary measures of last resort (Swedish Government, Citation2001, Citation2008a, Citation2012, Citation2016a). However, some individual MPs and, occasionally, whole parties, such as the Christian Democrats in 2018, have argued more explicitly for financing through loans (Forssmed & Halef, Citation2018; Westerberg et al., Citation2018), while actors outside of Parliament, such as unions (Karlsson & Thorwaldsson, Citation2017), left-wing press (Björklund, Citation2018), industry groups and the STA have unequivocally argued for the incompatibility between normal planning budget procedures – with a fixed budget within which the STA must prioritise between projects – and HSR planning (Elmsäter-Svärd & Lagerlöf, Citation2018b; STA, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Trouvé, Citation2017; Wessberg & Håkansson Boman, Citation2017).

The same assumption also leads to a persistent search, regardless of political colour, for new sources of financing, such as co-financing from municipalities, regional authorities and the private sector (Andersson, Citation2010; Swedish Government, Citation2008a, Citation2012, Citation2016b), for processes of optimisation and cost-reduction (Swedish Government, Citation2008b, Citation2011, Citation2012, Citation2016a), and for arguments that HSR can be funded through future income streams (e.g. Swedish Government, Citation2016a). Under the conservative-liberal government, in power between 2006 and 2014, there is increased emphasis on achieving cost-efficiency (Swedish Government, Citation2008b, Citation2011, Citation2012), which is then carried on in the work of the subsequent Social Democrat-Green government (Swedish Government, Citation2016a). Furthermore, this assumption also enters the discourse through the cost–benefit analyses used by the STA. Here, it is operationalised through the employment of a ‘tax factor’, a multiplier assumed to reflect the extra tax outtake the state will need to finance a project (TA, Citation2012).

Thus, the dominance of the issue of financing and the broad consensus around the merit of budgetary limits mean that material aspects of the Swedish transport infrastructure system tend to become abstracted into issues of purely monetary concern when HSR is discussed. In the functioning of the STA, the operations discussed above, for example, coupling individual projects to sources of financing and determining the socio-economic profitability of projects, are distinct from each other, associated with specific routines and methods for knowledge production. However, they are united through the same understanding of money as the fundamentally constraining aspect in transport planning, rather than physical resources. Arguments about HSR thus come to revolve around the idea of burdening future generations with debt and thereby lead to discussion about when the state might be allowed to run that risk. We turn to this in the following section.

The role of the state in socio-technical change

The second theme concerns the role actors in the discourse ascribe to the state in enforcing socio-technical change, especially as it relates to the issue of financing large infrastructure projects. The high financial stakes associated with HSR in Sweden mean proponents must justify the investment with stakes of equal magnitude. Having originally been promoted, in the 1990s, as a necessary measure to keep Swedish trade links up to date, as well as a way for the state to stimulate a sluggish economy (Sunesson, Citation1998), HSR becomes increasingly framed as an environmental measure that could allow Sweden to reach its transport decarbonisation targets. With the added weight of official climate commitments, HSR proponents can then argue that HSR is a precondition for sustained and sustainable growth and that Sweden is lagging behind comparable European nations when it comes to railway development (Ekelund, Citation2007; Eriksson & Svensson-Smith, Citation2007, Citation2008, Citation2010; Eriksson & Wetterstrand, Citation2009; Johansson et al., Citation2007; Johansson & Leijonborg, Citation2009; Kinhult & Persson, Citation2012; Nordin, Citation2008; Nordin & Hamilton, Citation2009; Reepalu & Micko, Citation2009; Serder & Daub, Citation2012; Svensson-Smith, Citation2008b, Citation2008c; Svensson-Smith & Andersson, Citation2010; Weibull Kornias et al., Citation2010). Since 2007, HSR has been intensely promoted within a framing of sustainable and geographically inclusive growth. Often, smaller governmental parties, as well as parties in opposition, are most vocal in arguing for the state to commit to HSR (Bergström & Romson, Citation2012; Björklund, Citation2008; Boman Karlsson, Citation2008; Centerpartiet, Citation2007; Dahl, Citation2009; Eriksson & Svensson-Smith, Citation2007, Citation2008, Citation2010; Eriksson & Wetterstrand, Citation2009; Färm, Citation2010; Forssmed & Halef, Citation2018; Fridolin, Citation2012; Hallengren, Citation2010; Karlsson, Citation2009a, Citation2009b; Sahlin et al., Citation2010; Svensson-Smith, Citation2008a, Citation2008b, Citation2008c, Citation2010; Svensson-Smith & Englesson, Citation2010; Svensson-Smith & Rudén, Citation2010; Ygeman, Citation2010; “Bestämmer Borg … ”, Citation2008; “Blir Ostlänken … ”, Citation2008; “Centern spårar … ”, Citation2007; “Miljarder till … ”, Citation2008; “Ökat tryck … ”, Citation2008; “S och Mp vill … ”, Citation2008; “S-gruppledarna listar … ”, Citation2010; “Sluta peka … ”, Citation2010), while larger parties in government – the Social Democrats and the Conservative Party – have been reluctant to sidestep the fiscal framework (Asp, Citation2008b; Björklund, Citation2008; Borg, Citation2010; Sax, Citation2008; Svensson-Smith, Citation2008a; “Bestämmer Borg … ”, Citation2008; “Blir Ostlänken … ”, Citation2008; “Ökat tryck … ”, Citation2008).

Members of Parliament arguing for HSR frequently identify it as a matter of modernising a transport system with ‘obsolete technology’ (Andersson & Ygeman, Citation2013), ‘taking the next step in the evolution of the train’ making travel ‘climate smart’ (Centerpartiet, Citation2008), developing a railway system of ‘European standard’ (Boman Karlsson, Citation2008; “Miljarder till … ”, Citation2008; “S och Mp vill … ”, Citation2008), ‘orienting [transport policy] to the future’ (Eriksson & Svensson-Smith, Citation2010; Svensson-Smith & Andersson, Citation2010), and gaining competitive advantage by building railways for the future (Bergström & Romson, Citation2012; Fridolin, Citation2012). Yet, such commitments notwithstanding, once in government, parties have heretofore failed to deliver little more than statements of ambition to build HSR when funding is made available. The conservative-liberal government took a cautious approach in 2010 (Ferm, Citation2010; Hinderson, Citation2010; Nyström, Citation2010; Torstensson, Citation2010; “En budget … ”, Citation2010), and the Social Democrat-Green government decided in 2014 that further investigations were needed, whereas it has since reiterated its ambition to build HSR on the premise that financing can be agreed in Parliament (Lönnaeus, Citation2016; Tribo & Glad, Citation2016).

The forceful rhetoric about the state taking the lead in a great transport modernisation project stands in contrast to the guiding principles for socio-technical change laid down in governmental transport bills. Each bill since 2005 is heavily oriented towards solutions pertaining to individual choice, free competition and the pricing mechanism (Swedish Government, Citation2005, Citation2008a, Citation2008b, Citation2012). In short, they profess a belief that the main objective of the state is to ensure a proper functioning of the existing transport system, and – using the existing CO2 tax as the main regulatory mechanism – ‘customer’ choice will generate a sustainable transition. This view is internalised by the STA, who consistently argue that decarbonisation is dependent on changes to the material infrastructure only to a limited extent, and that proper regulatory instruments such as carbon pricing are more important (STA, Citation2011, Citation2017a, Citation2020c).

This distinctly market-oriented perspective can first be seen in the Social Democrat government transport bill of 2005, but it is drastically accelerated by subsequent conservative-liberal governments. When the Social Democrat leader of the Parliamentary Transport Committee accuses the conservative-liberal government, in 2010, of implementing ‘a political strategy [in railway transport] so extreme it most closely resembles that of Margaret Thatcher’, there is therefore a sense of tragedy, as the critique is levelled at institutional changes set in motion by his own party (Ygeman, Citation2010). The Social Democrats in government, and especially when co-governing with the Greens since 2014, have consistently shifted the investment budget in favour of the railway and explicitly argued for a need to reduce road traffic (Swedish Government, Citation1996, Citation2001, Citation2005, Citation2016a), while the conservative-liberal government assigned larger proportions of the budget to road investments, and put more emphasis on greening, rather than reducing, car transport (Swedish Government, Citation2008a, Citation2012). Yet, the Social Democrat party in government has significantly contributed to the orientation towards market solutions and the bracketing of governmental agency in infrastructural change, not least by consistently stressing the primacy of cost-efficiency and fiscal prudence.

Thus, in the parliamentary arena, the HSR vision appears more as a faint wish than a project of conviction. It seems telling that the Social Democrat Minister of Infrastructure was left expressing his ‘hope’ that Parliament might agree on creating extraordinary budget provision for HSR when launching the transport bill of 2018 (Augustsson, Citation2018; Fransson & Klarberg, Citation2018; “Fortfarande oklart … ”, Citation2018). Instead, voices calling for ‘courage and belief in the future’ (Johansson & Leijonborg, Citation2009) to break a ‘cowardly’ path-dependent reliance on cars (Dahl, Citation2009; “Snabbtåg är … ”, Citation2008; “Ta tåget!”, Citation2009), and allow for ‘a touch of monumentality’ (“Med hög … ”, Citation2009) came from the editorial pages of liberal newspapers (Asp, Citation2008a; Dahl, Citation2009; Sax, Citation2008; Torstensson, Citation2010; “Sluta peka … ”, Citation2010; “Snabbtåg är … ”, Citation2008; “Ta tåget!”, Citation2009; “Visa handlingskraft!”, Citation2008), environmental organisations and representatives of municipalities and regions (Ekelund, Citation2007; Elmsäter-Svärd & Lagerlöf, Citation2018a; Fritzon et al., Citation2016; Fritzon, Citation2017; Hulthén et al., Citation2013; Johansson & Leijonborg, Citation2009; Kinhult & Persson, Citation2012; Micko & Knape, Citation2018; Nordin, Citation2008; Nordin & Hamilton, Citation2009; Reepalu & Micko, Citation2009; Trouvé, Citation2017; Weibull Kornias et al., Citation2010; Wessberg & Håkansson Boman, Citation2017; Westerberg et al., Citation2018), unions (Karlsson, Citation2018), railway organisations and organisations representing export-oriented industries (Andreasson, Citation2005; Elmsäter-Svärd & Lagerlöf, Citation2018a; Fritzon et al., Citation2016; Johansson, Citation1993; Johansson & Leijonborg, Citation2009; Rosengren, Citation2010; Sunesson, Citation1998; Svensson-Smith, Citation2010; Wallner, Citation1992; Westerberg et al., Citation2018; “Tågen skall … ”, Citation2010), and academic planning experts (Cars & Engström, Citation2018). While these groups differ in their emphasis on why HSR is needed, a uniting theme is the view that Swedish governments lack the visionary courage shown by the progenitors of the country’s first railway in the nineteenth century. Thus, what they seek is a state that enforces rather than acts as hostage to change.

Fatalism in technocratic governance

The third and final theme concerns a particular feature of Swedish transport planning, namely the reliance on technocratic experts for prognoses and socio-economic modelling, and how this determines the relationship between the STA and the government.

Since the early 1990s, academic economists in Sweden have been united in resisting HSR on the grounds that it constitutes a bad investment (“Miljardrullning på … ”, Citation1996). There are more cost-efficient measures for reducing greenhouse gases, they have argued, and demographic factors make Sweden ill-suited for HSR (Andersson et al., Citation2017a; Åman, Citation2009a, Citation2009b, Citation2010; Börjesson et al., Citation2018; Corshammar et al., Citation2016; Hultkrantz, Citation2009; Karlberg, Citation2010; Karyd, Citation2009; Kågesson, Citation2010; Larsson, Citation2010; Nilsson & Pyddoke, Citation2009; Wikström, Citation2010; “Experter dömer … ”, Citation2018; “Snabbtågsplaner möter … ”, Citation2018). Instead, governments have been encouraged to ‘hold the wallet tight’ (Ekelund, Citation2007; Fröidh, Citation2007; “Håll i … ”, Citation2008) so as not to crowd out more worthwhile investments (Arwidson, Citation2009; Åman, Citation2009a, Citation2009b; Karlsson, Citation2009a; Karyd, Citation2009; “Dyrt som … ”, Citation2009; “Trots det … ”, Citation2009) for a project whose climate benefits are uncertain (Johansson & Kriström, Citation2018).

Engineers and transport planners in academia have retorted that such arguments rest on an economic calculus that assumes, exogenously, the growth of road transport. In favour of HSR, these actors have instead posited models they regard as less deterministic and more realistic, in that they are open to the possibility of actually breaking the strong car paradigm in transport planning (Andersson et al., Citation2017a; Cars & Engström, Citation2018; Cedermark et al., Citation2012; Corshammar et al., Citation2016; Ekelund, Citation2007; Fröidh, Citation2007; Karlberg, Citation2010; Stichel et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Tribo & Glad, Citation2016; “Expert förespråkar … ”, Citation2008; “Håll i … ”, Citation2008; “Snabbtåg är … ”, Citation2008). The state-owned Swedish Railway company and, for most of the period until it was dissolved into the Transport Administration, the Railway Administration, have echoed these arguments. The planning director of the latter, for example, argued in 2008 that ‘no socio-economic calculation in the world could foresee’ the effects of fundamental sustainability transitions (Asp, Citation2008a). Smaller parliamentary parties – the Greens especially – have raised the same kinds of arguments against what has been perceived as far too narrow a framework for estimating the effects of HSR (Dahl, Citation2009; Eriksson & Svensson-Smith, Citation2010; Eriksson & Wetterstrand, Citation2009; Forssmed & Halef, Citation2018; Karlsson, Citation2009a, Citation2009b; Svensson-Smith, Citation2008a, Citation2008c, Citation2010; “Sluta peka … ”, Citation2010).

To a significant extent, this has amounted to arguments about whose models are the most realistic and useful for capturing the dynamics of large-scale state investments in infrastructure. Some HSR proponents, however, have ventured to criticise the very notion that models should be relied upon for investment decisions that could change transport patterns over decades or even centuries (Andersson et al., Citation2017a; Cars & Engström, Citation2018; Petersson, Citation2020; Stichel et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b). H.G. Wessberg, former Conservative government official and leader of the negotiations for the establishment of HSR under the conservative-liberal government, explicitly argues, for example, that massive infrastructure projects like HSR are only superficially about economics and are really a matter of ‘societal philosophy’. Thus, he argues, money is never a fundamentally limiting factor but may be construed as such due to a flawed understanding of politics and the role of the state (Anderberg, Citation2017).

Against this critical backdrop, however, transport bills continuously stress the importance of planning being based on socio-economic calculations for informed planning decisions, and over time there is added emphasis on ‘optimisation’ of planning processes and the transport system as a whole through improved modelling tools (Swedish Government, Citation2012, Citation2016a). The fact that these models, as used by the STA, consistently foresee growth in road transport and total transport emissions (Road Administration et al., Citation2008; STA, Citation2011, Citation2020c) occasions a certain fatalism in government bills, where ambitious climate targets are juxtaposed with prognoses of increasing road transport. While the transport bills of the 2000s, both Social Democrat and conservative-liberal (Swedish Government, Citation2005, Citation2008a, Citation2008b), are more optimistic in tone than that of the Social Democrat-Green government in 2016 (Swedish Government, Citation2016a), they are all united in a conspicuous lack of reflection on the difference between targets and reality.

Yet, while there is no real analysis on why the largely market-based approach to decarbonisation of transport has failed to yield significant results, there is over time an increased tendency for governments to highlight the imperative of decarbonisation for the STA, and the importance of planning for HSR within that context. Towards the end of the conservative-liberal government period, HSR is moved from vague idea to concrete planning objective (Swedish Government, Citation2012, Citation2014a, Citation2014b). Under the Social Democrat-Green governments from 2014, HSR becomes further identified with sustainable and geographically inclusive growth, and the climate target in the mission of the STA is increasingly stressed by the government (Swedish Government, Citation2016a, Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

The STA, meanwhile, relies on models that show HSR to be either only moderately beneficial for society (STA, Citation2014) or even amounting to a socio-economic net cost (Road Administration et al., Citation2009; STA, Citation2017c, Citation2020c). The assumption of monetary inelasticity noted above is institutionalised at the STA through cost–benefit analyses that assume that state investments in HSR necessarily occasion an ‘opportunity cost’ equivalent to another actor not being able to use the resources needed for HSR (STA, Citation2017d). Because road transport is also assumed to be socio-economically more efficient than railway, it follows from the models that an HSR investment must risk crowding out investments with greater benefits for society (STA, Citation2017c, Citation2020c). When the Social Democrat-Green government assigns the STA to plan for HSR after 2014, the agency therefore continuously argues – sometimes against the explicit directive – that HSR should either be awarded funding outside the standard planning budget, or be postponed (STA, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2020c). It repeatedly concludes that a restricted budget will limit the benefits associated with HSR, resulting in lower speeds and placement of stations outside city centres, resulting in planning visions far removed from those put forward by politicians (Elmsäter-Svärd & Lagerlöf, Citation2018a; STA, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Trouvé, Citation2017; Wessberg & Håkansson Boman, Citation2017).

Thus, the political directives to plan for HSR and a decarbonised transport sector yield a tension in relations between the government and the STA that becomes increasingly apparent over time. Having initially merely noted, without further analysis, that transport emissions are moving in the wrong direction in relation to climate targets (STA, Citation2011), the STA eventually begins to explicitly acknowledge the existence of a conflict between its accessibility target and its sustainability target. As it does so, it sets out limits for its own planning mandate, arguing that physical infrastructure is of subordinate importance for decarbonisation compared to regulatory measures aimed at changing behaviour, i.e. measures that must be taken by government and Parliament (STA, Citation2011, Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2017a, Citation2017c, Citation2020c). The Social Democrat-Green government, in return, emphasises that the STA has been tasked with contributing to transport decarbonisation and must show in its transport plans how such a fundamental systems change may occur (Swedish Government, Citation2016a, Citation2018a, Citation2018b).

In effect, this growing tension amounts to a conflict between the government and the STA about who is capable and responsible for breaking material dependencies that are increasingly conceived of as problematic. In the following discussion, we will trace the source of this tension and the other themes identified above to storylines about Swedish modernisation.

Discussion

Above, we marked out three distinct themes in the HSR discourse: the issue of financing, the role of the state in socio-technical change, and fatalism in technocratic governance. In the following, we will set out our explanation as to the centrality of these themes using Hajer’s analytical framework of storylines.

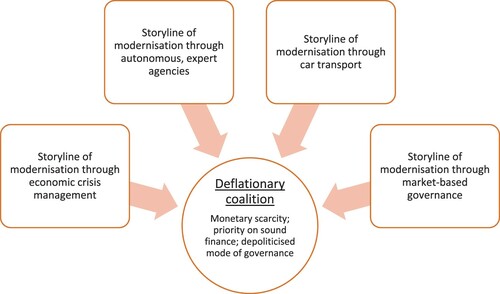

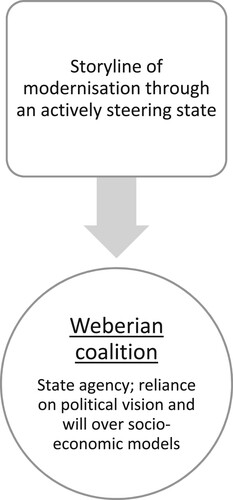

What we will argue here is that separate storylines about state agency converge in the HSR discourse, creating an overarching storyline about Swedish modernisation. This storyline gives priority to a certain kind of knowledge about the transport system, in which cost control, budgetary balance and responsiveness to external demand are of primary importance. The storyline unites disparate actors in a deflationary coalition, where diverging political ambitions in relation to HSR are subordinated to the overarching political goal of maintaining sound finances and the current, depoliticised institutional structure of the planning system. As Van Assche et al. (Citation2017a, Citation2017b) argue, the discursive power residing within modern planning systems – determining what and what not to problematise as an object of governance – has the effect of rendering certain aspects of the material world more visible than others. In this case, the dominant forms of knowledge within the deflationary coalition necessarily put the focus on cost-efficient, marginal modifications to the existing transport system, thus reinforcing existing material dependencies while precluding the possibility for transformative changes. However, a competing but weaker discourse coalition, which we call the Weberian coalition, adopts a different storyline about Swedish modernisation that allows for a different kind of knowledge about state capacity.

The deflationary coalition

Scarcity and sound finance

To understand the specific form the discursive themes of financing and a restrained state take in the Swedish HSR discourse, it is necessary to highlight the importance of the economic problems the country experienced in the 1980s and especially during the financial crisis of the early 1990s. The privilege of interpretating the cause of these processes fell to a group of neoclassically schooled economic experts within academia and the political establishment, notably within the Social Democrat party that had been central to establishing the Swedish welfare state (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990; Mudge, Citation2018; Westerberg, Citation2014). A central tenet of neoclassical economic thinking, which carries great practical implications, is the principle of money ‘neutrality’, meaning that money is seen only as a medium for the exchange of resources on a market assumed to be always tending towards equilibrium. It follows that money, as a matter of theoretical principle, is assumed to map perfectly to the needs that constitute a certain market (Parguez, Citation1996). Through this assumption, market ‘disequilibrium’, or rather inflationary tendencies, are almost always assumed in neoclassical analysis to be caused by too much money being put into circulation by an overreaching state. Indeed, the very concept of state intervention, often taking the form of a dead metaphor because of its adoption into the standard vocabulary of economic commentators, is derived from this ideological setting (Fligstein, Citation2001).

Such, then, was the frame of analysis that interpreted the Swedish economic malaise as being the result of an overblown public sector, runaway public deficits, and low productivity (Sverenius, Citation1999). The remedy prescribed by the economic expert consensus, and adopted across the political spectrum, was strict focus on fiscal discipline and austerity measures that were uniquely harsh in an OECD context (Erixon, Citation2010). These were followed and sometimes accompanied by equally severe and uniquely wide-ranging (de)regulations aimed both at limiting public spending and at privatisation (Erixon, Citation2011). The subsequent reversal of economic fortunes for Sweden forms a key thread of the storyline that thus casts Sweden in a role as a miracle of productivity, but one that exists as such on pain of severe punishment from global markets that are ready to strike at the first sign of fiscal laxity.

It is a storyline, therefore, that stresses the importance of sound finances over efforts to stimulate the demand side of the economy. As such, it is perhaps not surprising that it has tended to marginalise Swedish business, which has seen its influence over the political establishment become curtailed, though not to the same degree as that of the trade unions (Erixon, Citation2011). More surprising, perhaps, is the extent to which this storyline has come to dominate industrial policy in a country famous for its active state. It is possible to speak of the formation of a ‘deflationary coalition’ within Swedish governance, that put financial restraint as a top priority in policy making (Feygin, Citation2021). This is obvious in the HSR discourse, where political parties as diverse as the Social Democrats and the Conservative Party use interchangeable metaphors of fiscal rectitude to emphasise their governmental credentials.

Notably, it is the largest parties on either side of the political spectrum that most explicitly adhere to the storyline, but all political parties are careful to profess its validity. They are united with experts in economics, who continuously highlight the moral risk of saddling future generations with debt for investments that have uncertain pay-offs, both economically and environmentally. Sound state finances are thereby invoked as an argument precluding HSR through a double and somewhat paradoxical logic: investments today cannot be allowed to indebt future generations, but at the same time the various (uncertain) benefits of HSR will only accrue in the future.

The perspective of future indebtedness signifies the way the storyline determines the HSR discourse by treating all resources – monetary as well as material – as scarce. First, material resources – raw materials as well as labour – are imagined to be deployed to the full capacity of the economy, which means that any large-scale state investment will risk leading to overheating and inflation. This vision is tacitly present throughout the discourse, and even though some actors venture to propose HSR precisely as a measure to expand the productive base of the economy, such ideas are marginalised by the storyline of scarcity and sound finance. Secondly, through the translation work in cost–benefit analyses used both by the STA and mainstream economists, the material infrastructure base of HSR is abstracted into a notional monetary cost assumed to represent investments withheld from other sectors of the economy. Thus, not only are all productive resources treated as scarce – and equally scarce – but because they are symmetrically abstracted into the same monetary value, money itself is defined as a scarce resource to be handled with utmost prudence in a zero-sum game of costs and benefits.

For the deflationary coalition, the risk of overheating the economy always looms larger than the uncertain benefits of adventurous industrial policy. The result is that material dependency upon the existing transport infrastructure is reinforced, as participants of the deflationary coalition are always forced to justify an investment against the horizon of scarce material and monetary resources – which are abstracted by the dominant storyline into one and the same thing. At the same time, the storyline highlights the successful ‘sanitisation’ of Swedish economy in the 1990s as being dependent on minimising state influence over the economy (Erixon, Citation2011; Jerneck, Citation2020; see also Power et al., Citation2019).

Depoliticised modernisation

The storyline about sound economic management is further reinforced by an institutional legacy and associated storylines that serve to depoliticise the issue of HSR. As Premfors et al. (Citation2009) argue, the Swedish government has a long history of awarding wide-ranging authority to relatively independent state agencies. In its reliance on rational, ‘predict-and-provide’ planning with a heavy focus on road transport, the STA is the institutional legacy of Swedish transport planning as it evolved in parallel with an increasingly entrenched car paradigm in the first post-war decades (Hultén, Citation2012; also Falkemark, Citation2006). Road transport, personal car ownership and the domestic car industry expanded massively during the years of breath-taking economic growth in Sweden in the 1950s and 1960s, and thus the car became a cornerstone of Swedish modernisation history (Anshelm, Citation2005; Lundin, Citation2014).

Since its inception in 2010, the STA has also been a prime example of the turn to market-based mechanisms of governance in later decades, evident in the HSR discourse in the form of increasing emphasis on cost-efficiency and ‘customer’ orientation. The agency has internalised a market-oriented perspective that stresses the importance of customer responsiveness, whereas active steering of transport patterns is defined as belonging to the realm of politics (Andersson et al., Citation2017b; Jacobsson & Sundström, Citation2017; Witzell, Citation2020; see also Meijling, Citation2020). Thus, the agency tasked with overseeing and enforcing the transformation of the transport system is one whose models and very modus operandi make it react to external demand rather than proactively shaping the infrastructural transport base. The government, meanwhile, operates on the stated assumption that the STA is in charge of transforming the transport system, strengthening an already depoliticised configuration of political responsibility.

The STA can therefore be seen to fuse three separate storylines in its operational logic, that together depoliticise the issue of planning for HSR: a storyline of highly autonomous state agencies, a storyline of Swedish modernisation based on ever-increasing road transport, and a storyline of market-based transport governance. These storylines work in mutually reinforcing ways together with the storyline of scarcity and sound finance. For example, the continuous optimisation imperative emanating both from the storyline of scarcity and sound finance and from the associated storyline of market-based transport governance limits the ability of the agency both to expand its internal organisation and to launch expensive new projects. Material dependency on the existing infrastructure thereby becomes further strengthened through multiple reinforcing feedback loops.

These four storylines converge within the HSR discourse in one main storyline that tells a specific version of Swedish modernisation and good governance (see ). It is a storyline that stresses the risk of fiscal overreach by the state, the need to control public expenditure and to focus on ‘cost-efficiency’, and the merit in founding transport planning on objective models and external demand rather than top-down, mission-oriented policies (Kattel & Mazzucato, Citation2018). Thus, similar to the character taken on by modern systems of natural resource management, analysed by Van Assche et al. (Citation2017b), transport planning becomes depoliticised by the deflationary coalition. Even though ambitious climate goals are present in the discourse, they are marginalised in favour of knowledge aimed at getting more ‘bang for the buck’, rather than achieving a fundamental transport decarbonisation.

Figure 1. The distinctive features of the deflationary discourse coalition and its associated storylines.

As these storylines converge to reinforce each other and the material dependency on existing infrastructure, they constrain the room for political manoeuvre within the discourse and create certain unexpected actor groupings within the deflationary coalition that they hold together.

For some actors in the deflationary coalition, the current state of affairs fits well with their ideological and political disposition. So, for example, there is no cognitive dissonance when the Conservative Minister of Finance stresses the importance of the state living within its means. For others, notably the Social Democrats, the coalition in which they find themselves appears more constraining. Seen over a thirty-year period, their continuous insistence on reducing emissions in the transport sector and shifting transport from road to railway has been effectively restrained within a discourse that severely curtails the possibility for state-led, transformative change of the transport system.

There is, however, a competing storyline in the HSR discourse, that seeks to reclaim a central role for the state in transport planning. No less than does the deflationary coalition, it gathers some strange bedfellows. We turn to this discursive grouping, which we term the ‘Weberian coalition’, next.

The Weberian coalition

It might be surprising to find trade unions and business organisations united in a discourse coalition, as they are in the Swedish HSR context. However, even when considering the history of deep antagonism between these interest groups, this same history highlights a number of points on which their interests align. Most notably, it seems obvious that they are both reliant – to a significant extent – on an active state. As Eriksson (Citation2016) has shown, austerity measures in the 1990s – weakening trade unions’ bargaining power – coincided with a marginalisation of business and industry interests within Swedish infrastructure investment planning.

Trade unions and business groups find themselves in the same discourse coalition as other actors, whose arguments for HSR might differ. Transport planners are, nominally at least, more concerned with the perceived flaws of the socio-economic transport models used by the STA than anything else. For representatives of municipalities and regional authorities, the local and regional transport dynamics are of primary importance, while environmentally motivated actors stress the need to shift transport from road and air to rail.

These groups are united through a storyline that posits a different version of Swedish modernisation (see ). Often invoking the daring and vision that guided those who established the first railway in Sweden in the mid-nineteenth century, the storyline construes of a past where the state did much more to actively shape the transport system and the material dependencies configured by the infrastructure. The centrality of massive road developments to Swedish post-war modernisation, for example, is taken as evidence of how political will can create and reconfigure material dependencies. In this storyline, Swedish history therefore offers ample proof of the difference between a state that is guided by vision, and a state that is overly committed to formalised rules.

Figure 2. The distinctive features of the Weberian discourse coalition and its associated storyline.

In this, the storyline echoes the famous critique of formal rationality developed by Max Weber (Kalberg, Citation1980). For Weber, politics could never be left to the hollow logic of economic models. Rather than relying on socio-economic calculus derived from formal logic, politics must ultimately reside in a vision about the good society. Weber’s contemporary, John Maynard Keynes, expressed similar sentiments when he stated that ‘anything we can actually do, we can afford’ (Keynes, Citation1978). The Weberian coalition echoes such ideas and thus attempts to shift the focus of the Swedish HSR discourse from the depoliticised level of fiscal balances to the level of politics. These ideas are worded most explicitly by the former Conservative government official H.G. Wessberg – another actor one does not expect to find in the same discourse coalition as trade unions and progressive Greens – when he calls for less economism and a more visionary state. For this Weberian discourse coalition, then, a fundamental transformation of material dependencies within the transport infrastructure would require nothing less than a fundamental recasting of the state’s role in society.

Conclusion – climate urgency and the knowledge disconnect

We have seen how separate storylines about how Swedish modernisation evolved in the post-war era have coalesced into two competing discourse coalitions. The hegemony of one of these – the deflationary coalition – restricts the opportunity to fundamentally alter the transport system. The two discourse coalitions are separated by differing knowledge claims: knowledge about what constitutes good governance, and knowledge determining societal value that inform investment decisions that will shape the future transport system. As Van Assche et al. (Citation2017b) argue, the knowledge regimes that constitute modern systems of governance risk becoming detached from the material realities which they are set to govern. In these concluding words, we will reflect on the indications of such a disconnect within the deflationary coalition and how it adds a further explanatory dimension to the competing claims of the Weberian coalition. This is in line with previous research that has identified a gap between institutionalised knowledge within Swedish infrastructure investment planning and policies aimed at full decarbonisation (Finnveden & Åkerman, Citation2014; Witzell, Citation2020).

While the knowledge underpinning the worldview of the deflationary coalition forms a hegemonic discourse, there is also an increasingly apparent divergence between the tools available within the present transport planning system and the demands made upon it from knowledge about the climate threat. There is an almost Kafkaesque feeling to reading near-identical statements in all governmental transport propositions since the mid-1990s, stressing the need for transport system transformation without any critical reflection upon the lack of progress. The increasing tension between the STA and the government about responsibility for implementing climate objectives in infrastructure investment planning is indicative of how the divergence imposes itself on a depoliticised structure of governance. Thus, mobilising a different kind of knowledge, as is done by following the storyline adopted by the Weberian coalition, can be seen as a way of unlocking an intractable discursive contradiction between irreconcilable knowledge claims.

Acknowledgment

The research in this paper has been funded by the Swedish Energy Agency and the Swedish Research Council, project number 48746-1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Simon Haikola

Simon Haikola is associate professor at Linköping University, Department of Tema – Technology and Social Change. He studies environmental politics from a sociological perspective and takes particular interest in how the state relates to the environment through industrial policy and environmental regulation.

Jonas Anshelm

Jonas Anshelm is professor at Linköping University, Department of Tema – Technology and Social Change. He has studied Swedish environmental history for 25 years and takes a particular interest in how conflicts of value emerge from environmental policies.

Notes

1 In 2010, a number of transport-related state agencies were replaced by the new Transport Administration. Up to then, railways had been mainly governed by the Railway Administration.

References

- Andersson, C., et al. (2017b). Marknadsstaten - Om vad den svenska staten gör med marknaderna - och marknaderna med staten. Liber.

- Anshelm, J. (2005). Rekordårens tbc: Debatten om trafiksäkerhet i Sverige 1945-1965. Linköpings Universitet.

- Buschmann, P., & Oels, A. (2019). The overlooked role of discourse in breaking carbon lock-in: The case of the German energy transition. WIRES Climate Change, 10(3). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.574

- Cousins, M., & Hussain, A. (1984). Michel foucault. Macmillan.

- Dobbin, F. (1994). Forging industrial policy - The United States, britain and France in the railway Age. Cambridge University Press.

- Eriksson, M. (2016). Between two regimes: Continuity and change in the Swedish transport utilities, 1939-2010. Umeå Papers in Economic History, 45.

- Erixon, L. (2010). The rehn-meidner model in Sweden: Its rise, challenges and survival. Journal of Economic Issues, 44(3), 677–715. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/JEI0021-3624440306

- Erixon, L. (2011). Under the influence of traumatic events, new ideas, economic experts and the ICT revolution: The economic policy and macroeconomic performance of Sweden in the 1990s 2000s. Comparative Social Research, 28(1), 265–330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/S0195-6310(2011)0000028009

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Polity Press.

- Falkemark, G. (2006). Politik, mobilitet och miljö - om den historiska framväxten av ett ohållbart transportsystem. Gidlunds.

- Feygin, Y. (2021). The deflationary bloc. Phenomenalworld.org, 21-01-09.

- Finnveden, G., & Åkerman, J. (2014). Not planning a sustainable transport system. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, pp 53-57, 46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2014.02.002

- Fligstein, N. (2001). The architecture of markets. Princeton University Press.

- Hajer, M. (1995). The politics of environmental discourse: Ecological modernisation and the policy process. Clarendon Press.

- Hultén, J. (2012). Ny väg till nya vägar och järnvägar - finansieringspragmatism och planeringsrationalism vid beslut om infrastrukturinvesteringar. Lund University.

- Jacobsson, B., & Sundström, G.2017). En modern myndighet - Trafikverket som ett förvaltningspolitiskt mikrokosmos. Studentlitteratur.

- Jerneck, M. (2020). Sluta snacka strunt om svensk ekonomi. Aftonbladet, 20-06-23.

- Kalberg, S. 1980. ‘Max Weber’s types of rationality: Cornerstones for the analysis of rationalization processes in history.’ American Journal of Sociology 85(5), 1145–1179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/227128

- Kattel, R., & Mazzucato, M. (2018). Mission-oriented innovation policy and dynamic capabilities in the public sector. Industrial and Corporate Change, 27(5), 787–801. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dty032

- Keynes, J. (1978). Employment policy. In E. Johnson & D. Moggridge (Eds.), The collected writings of John Maynard Keynes (pp. 264–420). Royal Economic Society.

- Lundin, P. (2014). Bilsamhället: Ideologi, expertis och regelskapande i efterkrigstidens sverige. Stockholmia.

- Meijling, J. (2020). Marknadisering - en idé och dess former inom sjukvård och järnväg 1970-2000. Royal Institute of Technology/KTH.

- Mudge, S. (2018). Leftism reinvented: Western parties from socialism to neoliberalism. Harvard University Press.

- Parguez, A. (1996). Beyond scarcity - A reappraisal of the theory of the monetary circuit. In G. Deleplace & E. J. Nell (Eds.), Money in motion. The jerome levy economics Institute series (pp. 155–199). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Power, K., Ali, T., & Lebdušková, E.2019). Discourse analysis and austerity: Critical studies from economics and linguistics. Routledge.

- Premfors, R., et al. (2009). Demokrati och byråkrati. Studentlitteratur.

- SEPA. (2019). Miljömålen – Årlig uppföljning av Sveriges nationella miljömål. Swedish Environmental Protection Agency/Naturvårdsverket.

- SEPA. (2020). Fördjupad analys av den svenska klimatomställningen 2020. Swedish Environmental Protection Agency/Naturvårdsverket.

- Sverenius, T. (1999). Vad hände med Sveriges ekonomi efter 1970? Demokratiutredningens skrift nummer 3, SOU 1999:150.

- TA. (2012). Skattefaktorer i transportsektorns samhällsekonomiska analyser. Transport Analysis/Trafikanalys, Stockholm, 2012:2.

- Van Assche, K., et al. (2017a). The will to knowledge: Natural resource management and power/knowledge dynamics. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 19(3), 245–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2017.1336927

- Van Assche, K., et al. (2017b). Power/knowledge and natural resource management: Foucaultian foundations in the analysis of adaptive governance. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 19(3), 308–322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2017.1338560

- Westerberg, A. (2014). New Public management och den offentliga sektorn. In A. Westerberg, Y. Waldemarson, & K. Östberg (Eds.), Det långa 1900-talet - när Sverige förändrades (pp. 85–119). Boréa.

- Witzell, J. (2020). Assessment tensions: How climate mitigation futures are marginalized in long-term transport planning. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2020.102503

Empirical material

- Swedish Transport Agency (STA) and predecessors.

- Road Administration, et al. (2008). Lägesrapport - samhällsekonomi stora objekt. Vägverket, Banverket, Luftfartsstyrelsen, Sjöfartsverket.

- Road Administration, et al. (2009). Förslag till nationell plan för transportsystemet 2010-2021. Vägverket, Banverket, Transportstyrelsen, Sjöfartsverket.

- STA. (2011). Samlad beskrivning - Effekter av nationell plan och länsplaner 2010-2021. Publication 2010:124. Trafikverket, 2011.

- STA. (2013). Förslag till nationell plan 2014-2025. Remissversion 2013-06-14. Trafikverket, 2013.

- STA. (2014). Planer för transportsystemet 2014-2025. Samlad beskrivning av effekter för förslagen till Nationell plan och länsplaner. Publication 2014:039. Trafikverket, 2014.

- STA. (2017a). Förslag till nationell plan för transportsystemet 2018-2029. Remissversion 2017-08-31. Trafikverket, 2017.

- STA. (2017b). Nya stambanor i plan. Utbyggnadsstrategi för höghastighetsjärnvägar. Publication 2017:168. Trafikverket, 2017.

- STA. (2017c). Åtgärder för minskade utsläpp av växthusgaser. PM till Nationell plan för transportsystemet 2018-2029. Publication 2017:157. Trafikverket, 2017.

- STA. (2017d). Ordlista med samhällsekonomiska begrepp. PM 2017-06-14. Trafikverket, 2017.

- STA. (2020a). Regeringsuppdrag angående nya stambanor för höghastighetståg - delredovisning 31 augusti 2020. PM, TRV: 2020/73247. Trafikverket, 2020.

- STA. (2020b). Regeringsuppdrag angående nya stambanor för höghastighetståg - underlag inför hearingar november 2020, reviderad 2020-12-01. PM, TRV: 2020/85985. Trafikverket, 2020.

- STA. (2020c). Inriktningsunderlag inför transportinfrastrukturplaneringen för perioden 2022-2033 och 2022-2037. Publication 2020:186. Trafikverket, 2020.

Governmental bills and other communications

- Swedish Government. (1996). Infrastrukturinriktning för framtida transporter. Governmental bill. Regeringens proposition 1996:97:53.

- Swedish Government. (2001). Infrastruktur för ett långsiktigt hållbart transportsystem. Governmental bill. Regeringens proposition 2001/02:20.

- Swedish Government. (2005). Moderna transporter. Governmental bill. Regeringens proposition 2005/06:160.

- Swedish Government. (2008a). Framtidens resor och transporter - infrastruktur för hållbar tillväxt. Governmental bill. Regeringens proposition 2008/09:35.

- Swedish Government. (2008b). Mål för framtidens resor och transporter. Governmental bill. Regeringens proposition 2008/09:93.

- Swedish Government. (2011). Planeringssystem för transportinfrastruktur. Governmental bill. Regeringens proposition 2011/12:118.

- Swedish Government. (2012). Investeringar för ett starkt och hållbart transportsystem. Governmental bill. Regeringens proposition 2012/13:25.

- Swedish Government. (2014a). Åtgärdsplanering för transportsystemet 2014-2025. Governmental missive. Regeringens skrivelse 2013/14:233.

- Swedish Government. (2014b). Investeringar för ett starkt och hållbart transport system - Bilaga 2 till beslut III vid regeringssammanträde den 3 april 2014. Governmental decision. Regeringsbeslut N2014/1779/TE m.fl.

- Swedish Government. (2016a). Infrastruktur för framtiden - innovativa lösningar för stärkt konkurrenskraft och hållbar utveckling. Governmental bill. Regeringens proposition 2016/17:21.

- Swedish Government. (2016b). Värdeåterföring vid satsningar på transportinfrastruktur. Governmental bill. Regeringens proposition 2016/17:45.

- Swedish Government. (2018a). Infrastruktur för framtiden - Bilaga 2 till beslut II 9 vid regeringssammanträde 31 maj 2018. Governmental decision. Regeringsbeslut N2018/03462/TIF.

- Swedish Government. (2018b). Infrastruktur för framtiden - Bilaga 4 till beslut II 9 vid regeringssammanträde 31 maj 2018. Governmental decision. Regeringsbeslut N2018/03462/TIF.

- Swedish Government. (2020a). Uppdrag att ta fram inriktningsunderlag inför transportinfrastrukturplanering för en ny planperiod. Governmental decision. Regeringsbeslut I 1 2020/01827/TP.

- Swedish Government. (2020b). Uppdrag angående nya stambanor för höghastighetståg. Governmental decision. Regeringsbeslut I 2 2020/01828/TP.

Print media

- Åman, J. (2009a). Höghastighetståg inte klimatsmart. Dagens Nyheter, 09-08-22.

- Åman, J. (2009b). Snabbtåg: Räddare kan bli gökunge. Dagens Nyheter, 09-08-30.

- Åman, J. (2010). Tåg: Dyrköpt hastighet. Dagens Nyheter, 10-01-08.

- Anderberg, J. (2017). Den gamle och tåget. Fokus.

- Andersson, E., Berg, M., & Nelldal, B.-L. (2017a). Så får vi råd med en ny järnväg för höghastighetståg. Göteborgsposten, 17-12-29.

- Andersson, M., & Ygeman, A. (2013). Bäst att satsa på snabbaste tågen. Svenska Dagbladet, 13-08-09.

- Andersson, Y. (2010). Europakorridoren måste byggas. Norrköpings Tidningar, 10-11-17.

- Andreasson, L. (2005). Höghastighetstågen har tappat fart. Helsingborgs Dagblad, 05-01-05.

- Arwidson, M. (2009). Bygg första dagens järnväg. Dagens Industri, 09-09-15.

- Asp, J. O. (2008a). Verligheten har kört om Oss. Helsingborgs Dagblad, 08-04-21.

- Asp, J. O. (2008b). Regeringen äntligen på spåret. Helsingborgs Dagblad, 08-03-14.

- Augustsson, T. (2018). Regeringen bromsar höghastighetstågen. Svenska Dagbladet, 18-06-11.

- Bergström, S., & Romson, Å. (2012). Ge järnvägarna ett lyft. Aftonbladet, 12-08-31.

- ‘Bestämmer Borg över Centerpartiet?’ . (2008). Folkbladet, 08-02-16.

- Björklund, P. (2018). Gärna snabbtåg - men först en rejäl pension. Flamman, 18-04-24.

- Björklund, T. (2008). Regeringen oense om järnvägar. Göteborgsposten, 08-03-30.

- ‘Blir Ostlänken Borgs nästa självmål?’ . (2008). Norrköpings Tidningar, 08-02-16.

- Boman Karlsson, L. (2008). Sex partier säger ja till höghastighetståg. Dagens Nyheter, 08-08-07.

- Borg, A. (2010). Vi kan inte leva över våra tillgångar. Göteborgsposten, 10-12-03.

- Börjesson, M., Flam, H., Hassler, J., Hultkrantz, L., Kågeson, P., Nilsson, J.-E., & Nyström, J. (2018). Höghastighetståg dålig affär för samhället och klimatet. Dagens Nyheter, 18-04-20.

- Cars, G., & Engström, C.-J. (2018). Snabbspåren ruvar på stora värden för regionerna. Dagens Samhälle, 18-06-15.

- Cedermark, H., Wannheden, C., & Åkesson, B. (2012). Ta höghastighetsbanorna ur malpåsen. Göteborgsposten, 12-04-30.

- ‘Centern spårar ur.’ . (2007). Sydsvenskan, 07-08-06.

- Centerpartiet . (2007). Förslag i centerpartiers nya miljöprogram. Centerpartiet, 07-08-25.

- Centerpartiet . (2008). Höghastighetståg på regeringens agenda. Centerpartiet, 08-03-14.

- Corshammar, P., Larsson, B., & Naumovski, V. (2016). Vi minns motståndet mot Öresundsbron … . Helsingborgs Dagblad, 16-10-24.

- Dahl, S. (2009). Är vi för fega för snabbtåg? Expressen, 09-07-10.

- ‘Dyrt som tåget.’ . (2009). Sydsvenskan, 09-09-15.

- Ekelund, Å. (2007). Sverige frånåkt i Europa. Veckans Affärer, 2007, 44.

- Elmsäter-Svärd, C., & Lagerlöf, P. (2018a). Sverige har inte råd att säga nej … . Helsingborgs Dagblad, 18-04-12.

- Elmsäter-Svärd, C., & Lagerlöf, P. (2018b). Varför säga nej till 285 400 nya bostäder? Dagens Nyheter, 18-04-20.

- ‘En budget utan infrastrukturprojekt.’ . (2010). SkD, 10-10-12.

- Eriksson, P., & Svensson-Smith, K. (2007). Kortare restider kräver snabbtåg och djärva visioner. Göteborgsposten, 07-08-08.

- Eriksson, P., & Svensson-Smith, K. (2008). Järnvägar är svaret på klimatförändringarna. Norrländska Socialdemokraten, 08-03-04.

- Eriksson, P., & Svensson-Smith, K. (2010). Snabbspår ett kliv mot framtiden. Svenska Dagbladet, 10-05-14.

- Eriksson, P., & Wetterstrand, M. (2009). Ett grönt kontrakt för Europa och framtiden. Göteborgsposten, 09-03-27.

- Eriksson, R. (2002). 350 km i timmen hela vägen till hamburg. Dagens Nyheter, 02-05-26.

- ‘Experter dömer ut snabbtågssatsning.’ . (2018). Svenska Dagbladet, 18-04-23.

- ‘Expert förespråkar höghastighetståg.’ . (2008). Sydsvenskan, 08-01-11.

- Ferm, P. (2010). Inga nya satsningar på järnvägen. Landskrona-posten, 10-10-13.

- Forssmed, J., & Halef, R. (2018). Därför tror vi att höghastighetståg behövs. Göteborgsposten, 18-04-12.

- ‘Fortfarande oklart om höghastighetstågen.’ . (2018). TT, 18-06-05.

- Fransson, J., & Klarberg, P. (2018). Kostnad för höghastighetstågen går inte att motivera. TTELA, 18-05-14.

- Fridolin, G. (2012). Gröna tåget är rätt biljett till framtiden. Expressen, 12-05-16.

- Fritzon, H., Hilding, M., & RIngdahl, O. (2016). Stora investeringar kräver stort mod. Helsingborgs Dagblad, 16-06-07.

- Fritzon, C. (2017). Elda inte för kråkorna - höghastighetståg måste byggas snabbt. Göteborgsposten, 17-09-26.

- Fröidh, O. (2007). Snabbtågen glöms bort. Sydsvenskan, 07-08-10.

- Färm, G. (2010). Tågfiaskot är alliansens fel. Folkbladet, 10-12-28.

- ‘Försena inte snabbtågen.’ . (2010). Göteborgsposten, 10-12-10.

- Hallengren, L. (2010). Bättre infrastruktur en bra julklapp till länet. Barometern, 10-12-13.

- Hinderson, P. (2010). Politik. Byggindustrin nr, 32), 10-10-22.

- Hulthén, A., Kinhult, P., & Reepalu, I. (2013). Ett projekt som kan lyfta sverige. Göteborgsposten, 13-05-13.

- Hultkrantz, L. (2009). Glädjekalkyl om höghastighetståg. Dagens Nyheter, 09-09-15.

- ‘Håll i plånboken.’ . (2008). Dagens Nyheter, 08-06-03.

- Johansson, A. (1993). Nya tåg på toppfart mot Europa. Dagens Nyheter, 93-01-08.

- Johansson, G., Wallin, J.-E., Andersson, G.-I., Andersson, K., Andersson, R., Bergsten, B., Hallström, P., Hedvall, K., Théen Johansson, E., Karlsson, G., Lövgren, M., Magnusson, J., Matsson, E., Nordström, L., Riste, T., Svensson, R., Ternstedt, A., Wernersson, M.-L., & Petersson, K. (2007). Skaffa fram EU-pengarna som kan ge oss snabbtåg. Dagens Nyheter, 08-05-17.

- Johansson, G., & Leijonborg, L. (2009). Höghastighetståg ett tillväxtspår för sverige. Göteborgsposten, 09-11-29.

- Johansson, P.-O., & Kriström, B. (2018). Snabba tåg är Ingen Klimatinvestering, 18-04-29.

- Karlberg, L. A. (2010). Professorernas stora duell om snabbtågen. Ny Teknik, 2010, 15.

- Karlsson, L.-I. (2009a). Snabbtåg ska minska restider. Dagens Nyheter, 09-09-15.

- Karlsson, L.-I. (2009b). Omtvistad miljövinst med höghastighetståg. Dagens Nyheter, 09-08-22.

- Karlsson, V. (2018). Slopa överskottsmålet - Sverige behöver höghastighetståg. Arbetet, 18-05-25.

- Karlsson, V., & Thorwaldsson, K.-P. (2017). Dags att låna till snabbtåg. Arbetet, 17-12-07.

- Karyd, A. (2009). Höghastighetståg ett olönsamt stickspår. Göteborgsposten, 09-12-01.

- Kinhult, P., & Persson, M. (2012). Snabba tåg bra för regionen. Helsingborgs Dagblad, 09-10-10.

- Kågesson, P. (2010). Dumdristigt av politikerna verka för höghastighetståg. Dagens Nyheter, 10-10-07.

- Larsson, M. (2010). Forskare: Snabbtåg ger ingen stor miljövinst. Dagens Nyheter, 10-04-27.

- Lönnaeus, O. (2016). Snabbtåg på väg att spåra ur. Helsingborgs Dagblad, 16-10-07.

- Lönnroth, A. (1995). Tågfejd blev tvekamp bidde en tummetott. Svenska Dagbladet, 95-12-12.

- Magnusson, E. (2018). Kristersson hoppas på flera uppgörelser. Helsingborgs Dagblad, 18-05-24.

- Magnusson, E. (2019a). C och Mp vill skynda på snabbtåg i skåne. Helsingborgs Dagblad, 19-01-25.

- Magnusson, E. (2019b). Eneroth vill skynda på snabbtåg. Helsingborgs Dagblad, 19-03-09.

- ‘Med höghastighetståg rakt in i det okända.’. (2009). Dagens Industri, 09-09-15.

- Micko, L., & Knape, A. (2018). Fullt möjligt att satsa mer på höghastighetsbana. Göteborgsposten, 18-03-13.

- ‘Miljardrullning på lös grund.’ . (1996). Svenska Dagbladet, 96-01-07.

- ‘Miljarder till forskning - Jan Björklund vill satsa på höghastighetståg.’ . (2008). Dagens Nyheter, 08-08-04.

- Nilsson, J.-E., & Pyddoke, R. (2009). Höghastighetsjärnvägar ett klimatpolitiskt stickspår. Dagens Nyheter, 09-02-21.

- Nordin, H. (2008). Krav på miljarder till infrastruktur. Göteborgsposten, 08-06-25.

- Nordin, S., & Hamilton, U. (2009). Bygg höghastighetsjärnväg längs E4an. Svenska Dagbladet, 09-07-21.

- Nyström, U. (2010). Det blir inga mer pengar. Göteborgsposten, 10-12-05.

- ‘Ökat tryck på regeringen att bygga höghastighetsspår.’ . (2008). Dagens Miljö, 08-02-11.

- Petersson, T. (2020). Trafikverket får skarp kritik för beräkning av tågtrafiken. Dagens Nyheter, 20-01-17.

- Reepalu, I., & Micko, L. (2009). Satsa på höghastighetståg. Sydsvenskan, 09-06-15.

- Rosengren, B. (2010). Snabba cash till snabba tåg. Dagens Industri, 10-10-16.

- Sahlin, M., Eriksson, P., Wetterstrand, M., & Ohly, L. (2010). Vi bygger höghastighetståg om vi vinner valet. Dagens Nyheter, 10-04-26.

- Sax, K. H. (2008). Lönsamt tåg. GT, 08-05-30.

- Serder, L., &Daub, F. (2012). Höghastighetståg ett skandinaviskt projekt. Göteborgsposten, 12-05-10.

- ‘S-gruppledarna listar de viktigaste frågorna.’ . (2010). Aktuellt i Politiken, 10-10-18.

- ‘Sluta peka finger och fixa tågtrafiken.’ . (2010). EK, 10-12-14.

- ‘Snabbtågsplaner möter kritik.’ . (2018). Folkbladet, 18-04-21.

- ‘Snabbtåg är framtiden.’ . (2008). Expressen, 08-01-12.

- ‘S och Mp vill satsa på snabbtåg.’ . (2008). Svenska Dagbladet, 08-11-28.

- Stichel, S., Berg, M., Andersson, E., & Nelldal B.-L. (2018a). Snabba tåg ger högre vinst. Dagens Industri, 18-04-26.

- Stichel, S., Berg, M., Nelldal, B.-L., & Andersson, E. (2018b). Har vi råd att inte bygga ut stambanorna snabbt? Göteborgsposten, 18-06-10.

- Sunesson, B. (1998). Projektet europabanan har en enorm potential. Svenska Dagbladet, 98-06-03.

- Svensson-Smith, K. (2008a). Lönsam investering oavsett klimatnytta. Sydsvenskan, 08-08-23.

- Svensson-Smith, K. (2008b). Regeringen är på helt fel spår i klimatpolitiken. Göteborgsposten, 08-09-13.

- Svensson-Smith, K. (2008c). Alliansen rustar ned tågtrafiken. Borås Tidning, 08-10-02.

- Svensson-Smith, K. (2010). Höghastighetståg är vägen till framtiden. Dagens Nyheter, 10-01-14.

- Svensson-Smith, K., & Andersson, M. (2010). Hög tid planera för höghastighetståg. Ny Teknik, 2010, 15.

- Svensson-Smith, K., & Englesson, A. (2010). Så slipper vi tågkaoset. Blekinge Läns Tidning, 10-12-23.

- Svensson-Smith, K., & Rudén, J. (2010). Ge tågtrafiken mer resurser - nu. Göteborgsposten, 10-12-05.

- ‘Ta tåget!’ . (2009). Expressen, 09-09-15.